Orientation

Biofeedback training (BFT) and neurofeedback training (NFT) involve the same learning processes we use to develop motor skills or master a videogame. An individual acts (breathes effortlessly), observes the results (heart rate variability increases), and repeats this action during meetings with clients. Clients actively learn to regulate their psychophysiology (Thompson & Thompson, 2016).

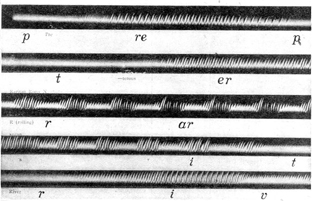

Biofeedback is also a "psychophysiological mirror" that teaches individuals to monitor, understand, and change their physiology (Peper, Shumay, & Moss, 2012). Graphic © 1979 Erik Peper.

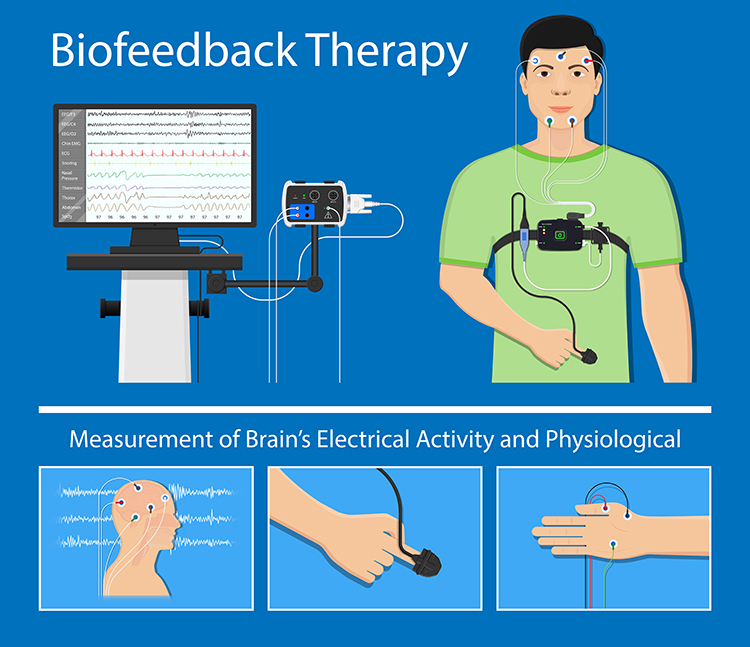

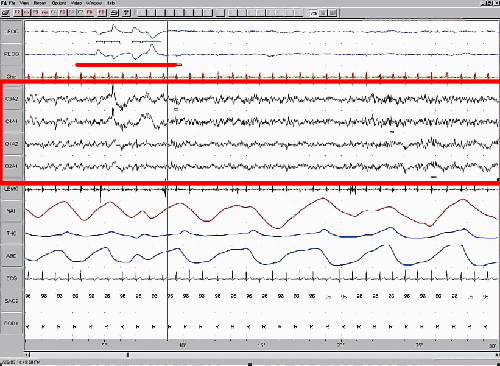

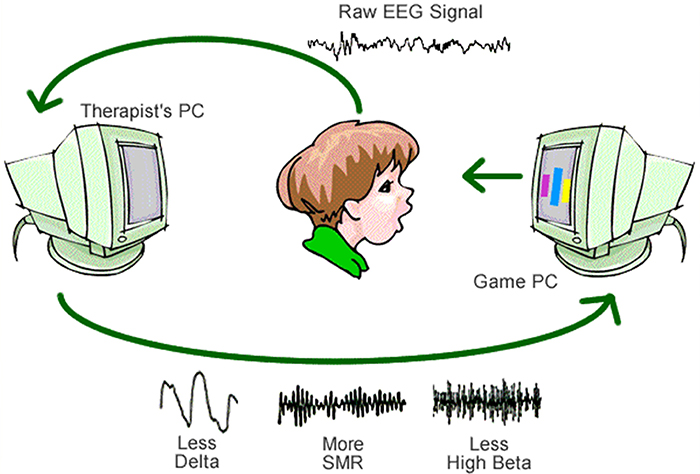

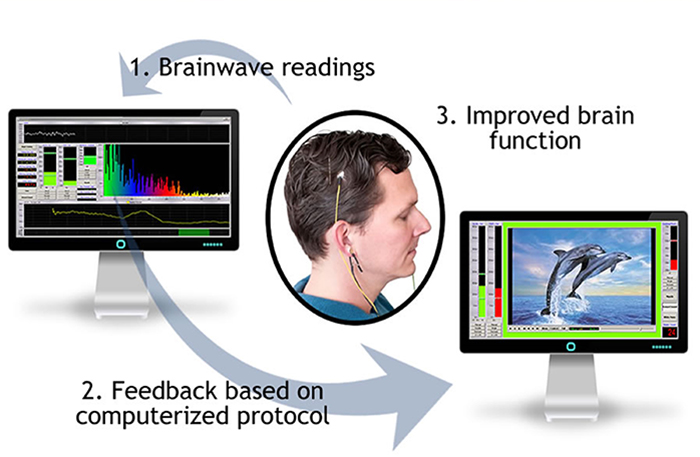

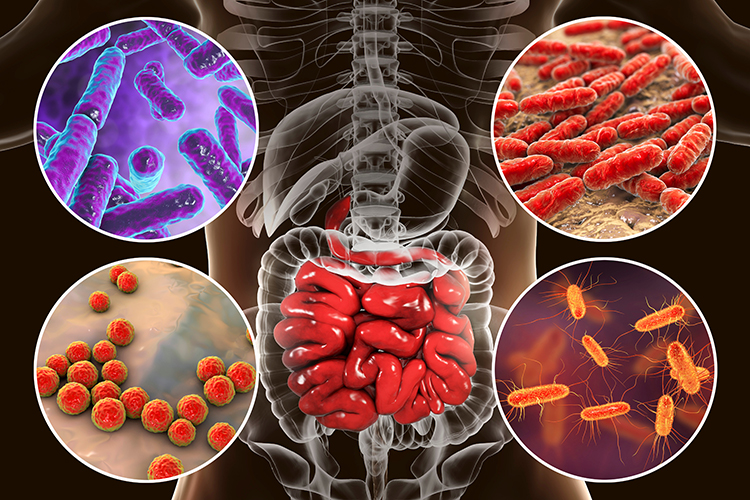

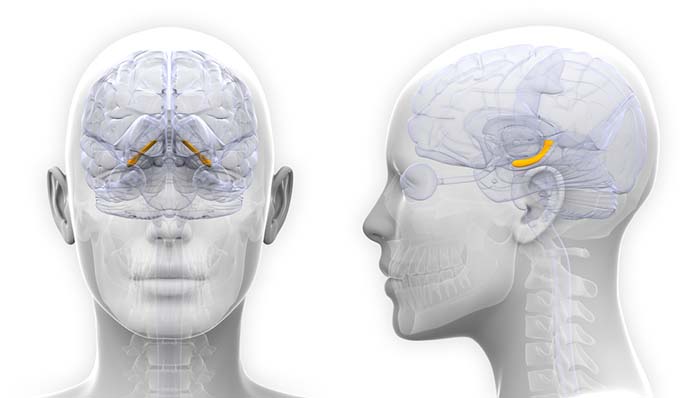

NFT is a branch of BFT that provides real-time displays using an electroencephalograph (EEG), as opposed to an electromyograph (EMG), heart rate variability (HRV), skin temperature, or other psychophysiological measures. An electroencephalograph monitors brain electrical activity (e.g., brainwaves), while an electromyograph detects muscle action potentials from skeletal muscles. These modalities differ in the signals they detect, process, and display (Collura, 2014).

The Process of Neurofeedback

Neurofeedback is the process of interacting with an electronic device that measures and feeds back information about brain electrical activity.

The goals of this process are to:

(1) ensure correct regulatory function in the brain's neuromodulating systems

(2) encourage global neuropsychophysiological change

(3) correct specific, distinct, identifiable disorders or barriers to optimal performance that result from underlying dysregulation

(4) enhance performance by optimizing nervous system functioning

What Neurofeedback Does

(1) Neurofeedback provides accurate, timely, and helpful information to the client in the form of visual, auditory, or tactile feedback that responds to meaningful changes in monitored neuronal systems

(2) Neurofeedback training promotes flexibility, resilience, and choice

Click on the link to view Neurofeedback Overview, produced by the International Society for Neuroregulation and Research (ISNR). Graphic © ibreakstock/Shutterstock.com.

BFT may be more effective when training promotes mindfulness. A mindfulness approach teaches clients to focus on their immediate feelings, cognitions, and sensations in an accepting and non-judgmental way, to distinguish between what can and cannot be changed, and to change the things they can (Khazan, 2013).

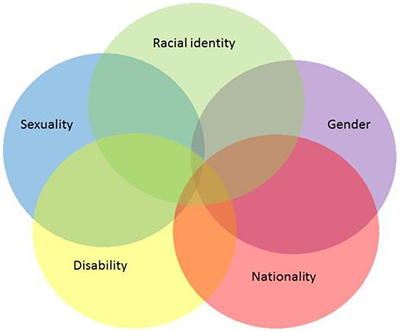

Clients can become stuck when they focus on outcomes they cannot immediately control. For example, James, an undergraduate Psychology major, was diagnosed with ADHD. For example, James, an undergraduate Psychology major, was diagnosed with ADHD. When he ruminated about his mistakes on daily quizzes, this undermined his motivation to study and resulted in lower scores. He could not study while he worried about his quiz performance. When James learned to accept occasional mistakes without fear, his studying and course grade improved. James succeeded by changing what he could: his reaction to unavoidable errors. Graphic © Ivelin Radkov/Shutterstock.com

MCP Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses I. Orientation to Neurofeedback (1 hour). This unit covers Definitions of Neurofeedback, History and Development of Neurofeedback, Overview of Principles of Human Learning as They Apply to Neurofeedback, and Assumptions Underlying Neurofeedback.

A. DEFINITIONS OF BIOFEEDBACK AND NEUROFEEDBACK

This section covers covers Definitions of Biofeedback and Neurofeedback, Physiological Monitoring and Modulation Are Not Biofeedback, and Quantum Biofeedback and LenyosisTM.

Since neurofeedback is a specialized application of biofeedback, we will start with the Biofeedback Alliance and Nomenclature Task Force definition (Schwartz, 2010).

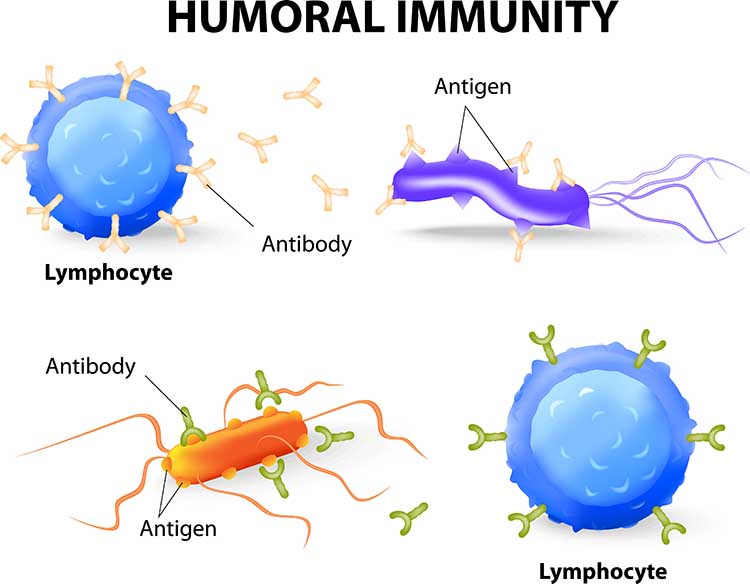

Biofeedback Alliance and Nomenclature Task Force (2008)

Biofeedback is a process that enables an individual to learn how to change physiological activity for the purposes of improving health and performance. Precise instruments measure physiological activity such as brainwaves, heart function, breathing, muscle activity, and skin temperature. These instruments rapidly and accurately 'feed back' information to the user. The presentation of this information — often in conjunction with changes in thinking, emotions, and behavior — supports desired physiological changes. Over time, these changes can endure without continued use of an instrument.The main elements of this definition are that (1) biofeedback is a learning process that teaches an individual to control her physiological activity, (2) biofeedback training aims to improve health and performance, (3) instruments rapidly monitor an individual's performance and display it back to them, (4) the individual uses this feedback to produce physiological changes, (5) changes in thinking, emotions, and behavior often accompany and reinforce physiological changes, and (6) these changes become independent of external feedback from instruments. Graphic © rumruay/Shutterstock.com.

The Biofeedback Certification International Alliance (BCIA) emphasized that neurofeedback is a form of biofeedback in its Blueprint of Knowledge.

Biofeedback Certification International Alliance (2016) definition of neurofeedback

Neurofeedback is employed to modify the electrical activity of the CNS, including EEG, event-related potentials, slow cortical potentials and other electrical activity either of subcortical or cortical origin. Neurofeedback is a specialized application of biofeedback of brainwave data in an operant conditioning paradigm. The method is used to treat clinical conditions as well as to enhance performance.

The International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (ISNR) provided a comprehensive definition of neurofeedback that described the similarities and differences between neurofeedback and biofeedback.

International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (2010) definition of neurofeedback

Like other forms of biofeedback, NFT uses monitoring devices to provide moment-to-moment information to an individual on the state of their physiological functioning. The characteristic that distinguishes NFT from other biofeedback is a focus on the central nervous system and the brain. Neurofeedback training (NFT) has its foundations in basic and applied neuroscience as well as data-based clinical practice. It takes into account behavioral, cognitive, and subjective aspects as well as brain activity.This definition was ratified by the ISNR Board of Directors on January 10, 2009, and edited on June 11, 2010. It emphasizes that neurofeedback is a "self-regulation method" that teaches clients to voluntarily change central nervous system activity. It draws a sharp distinction between neurofeedback and neuromodulatory approaches like audio-visual entrainment (AVE) and rTMS that alter the brain by exposing it to a stimulus. While these are potentially valuable adjunctive procedures, they do not provide feedback of brain activity nor teach self-regulation.

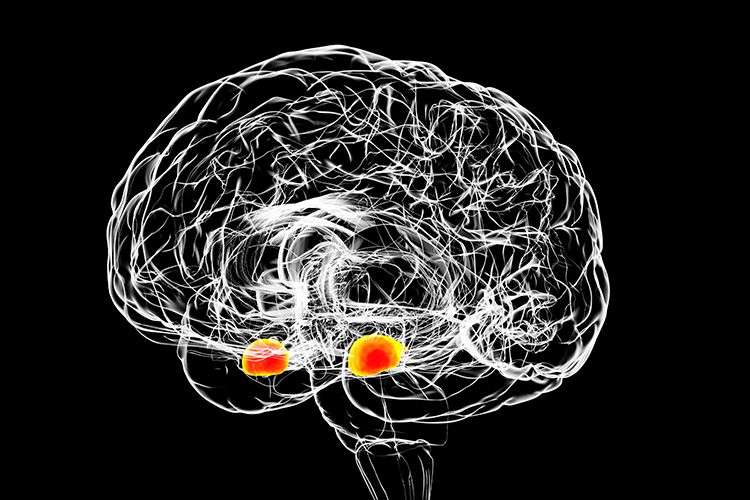

NFT is preceded by an objective assessment of brain activity and psychological status. During training, sensors are placed on the scalp and then connected to sensitive electronics and computer software that detect, amplify, and record specific brain activity. Resulting information is fed back to the trainee virtually instantaneously with the conceptual understanding that changes in the feedback signal indicate whether or not the trainee's brain activity is within the designated range. Based on this feedback, various principles of learning and practitioner guidance, changes in brain patterns occur and are associated with positive changes in physical, emotional, and cognitive states. Often the trainee is not consciously aware of the mechanisms by which such changes are accomplished although people routinely acquire a 'felt sense' of these positive changes and often are able to access these states outside the feedback session.

NFT does not involve either surgery or medication and is neither painful nor embarrassing. When provided by a licensed professional with appropriate training, generally trainees do not experience negative side-effects. Typically trainees find NFT to be an interesting experience. Neurofeedback operates at a brain functional level and transcends the need to classify using existing diagnostic categories. It modulates the brain activity at the level of the neuronal dynamics of excitation and inhibition which underlie the characteristic effects that are reported.

Research demonstrates that neurofeedback is an effective intervention for ADHD and Epilepsy. Ongoing research is investigating the effectiveness of neurofeedback for other disorders such as Autism, headaches, insomnia, anxiety, substance abuse, TBI and other pain disorders, and is promising.

Being a self-regulation method, NFT differs from other accepted research-consistent neuro-modulatory approaches such as audio-visual entrainment (AVE) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) that provoke an automatic brain response by presenting a specific signal. Nor is NFT based on deliberate changes in breathing patterns such as respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) that can result in changes in brain waves. At a neuronal level, NFT teaches the brain to modulate excitatory and inhibitory patterns of specific neuronal assemblies and pathways based upon the details of the sensor placement and the feedback algorithms used, thereby increasing flexibility and self-regulation of relaxation and activation patterns.

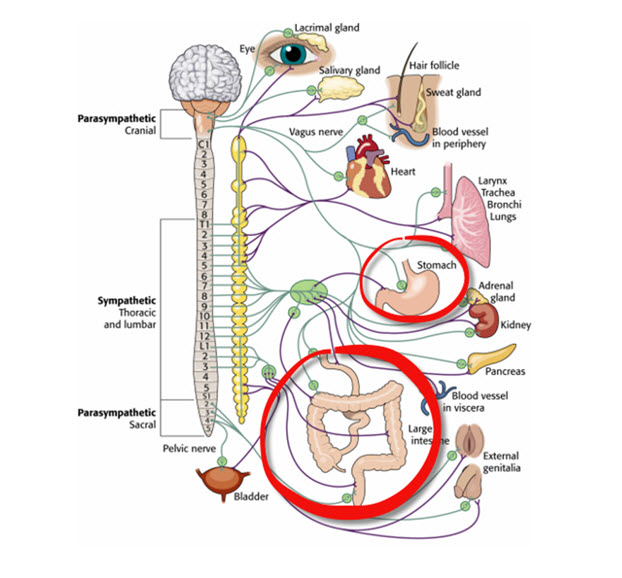

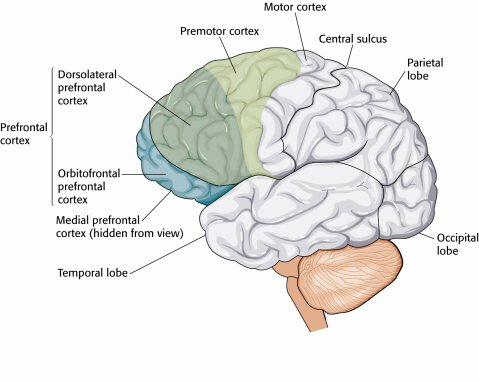

Perspective

Two issues that require clarification are the focus of biofeedback and NFT and the possibility or likelihood of negative side effects.First, the ISNR definition states: "The characteristic that distinguishes NFT from other biofeedback is a focus on the central nervous system and the brain." This description supports the view that while NFT is top-down, biofeedback training (BFT) is bottom-up. A more nuanced explanation is that both NFT and BFT involve top-down and bottom-up interventions. The arbitrary differentiation between body-centered and central nervous system (CNS) interventions results from an incomplete understanding of the interconnections between these systems. For example, the CNS is instrumental in modifying behaviors like respiration, and changes in respiration modulate CNS activity. Hyperventilation leading to hypocapnia causes a general slowing of the EEG (Takahashi, 2005).

Therefore, NFT and BFT share components like breathing, education about the training process, mindfulness, and problem-solving, involving the "central nervous system and the brain." Likewise, since the central and peripheral nervous systems cooperate through complex feedback and feedforward loops, we can conceptualize them as one complex integrated system.

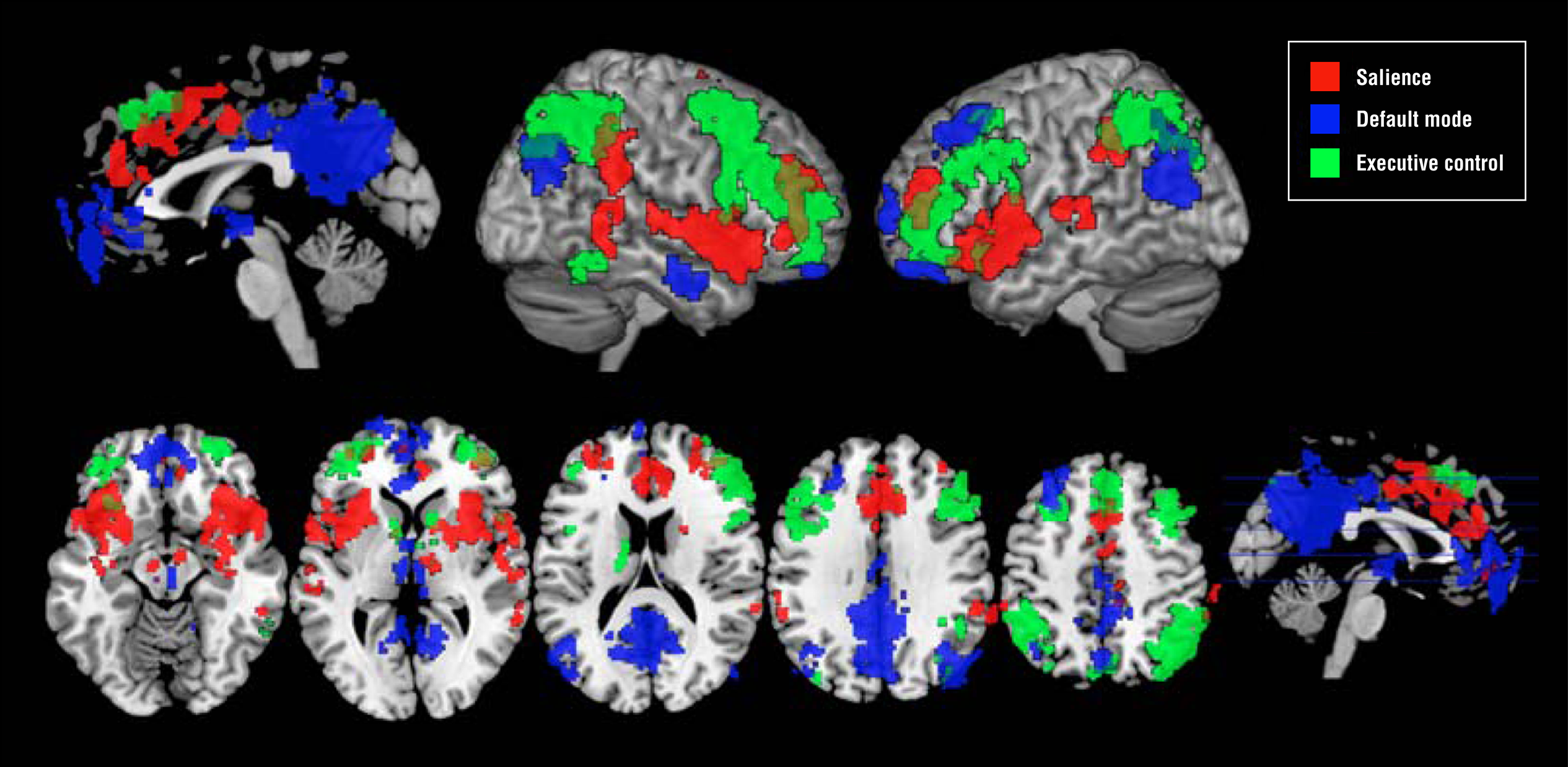

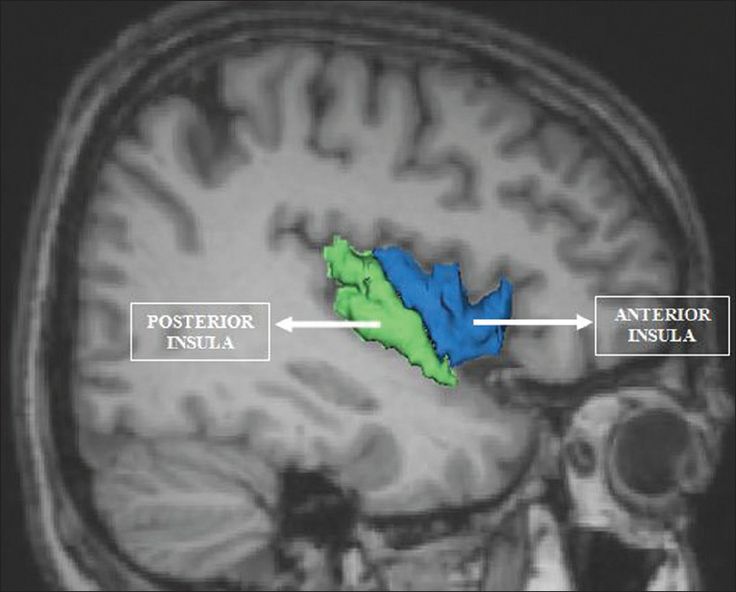

For example, providers who work with inattention may begin with heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB), which trains clients to increase the difference in the time intervals between successive heartbeats. Whereas attention involves brainstem, subcortical, and cortical networks, successful HRVB training (which is often characterized as bottom-up) may significantly increase continuous attention and make NFT unnecessary or may facilitate improved outcomes when followed by NFT for this condition.

Second, the ISNR definition claims: "When provided by a licensed professional with appropriate training, generally trainees do not experience negative side-effects." Hammond and Kirk (2008) marshaled evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and anecdotal reports that when applied incorrectly, neurofeedback can be associated with adverse reactions like anxiety, depression, emotional lability, explosiveness, incontinence, OCD, and sedation.

Hammond and Kirk did not rigorously evaluate the anecdotal reports supplied by trainers for length or severity of disruption resulting from NFT. In most cases, such effects are temporary unless reinforced by continuing incorrect training approaches (J. S. Anderson, personal communication, June 6, 2016).

Rogel et al. (2015) reported that a randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind study found no statistically significant differences in the number of side effects reported between sham and upper alpha and SMR treatment groups. The SMR group had a higher number of reported headaches.

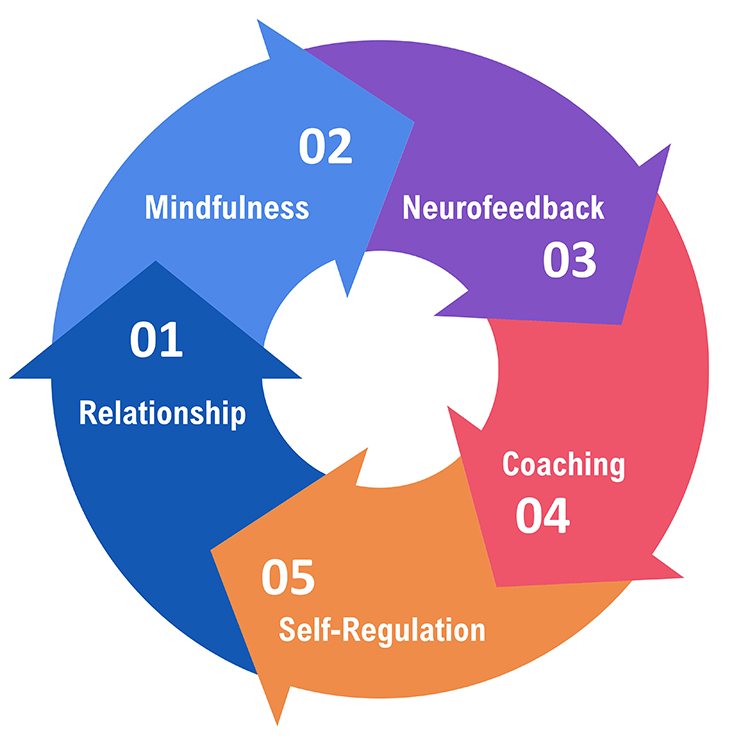

Core Elements of Neurofeedback

The client-trainer relationship is the foundation of BFT and NFT. Neurofeedback is most effective when clients and providers are mindful because this promotes self-awareness and a sense of agency. Neurofeedback promotes self-regulation when a trainer provides effective coaching (Khazan, 2019).

Physiological Monitoring and Modulation Are Not Biofeedback

Physiological monitoring, detecting biological activity like blood pressure, is only one biofeedback component. When nurses measure your blood pressure, this is physiological monitoring. Nurses provide biofeedback when they report these values to you because this gives you information about your biological performance. When your nurse announces that your blood pressure was 120/70, this closes the loop and allows you to refine your self-awareness and control of your physiology. Graphic © Sean Locke Photography/Shutterstock.com.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Physiological Monitoring and Modulation © BioSource Software LLC.

Likewise, modulation, stimulating the nervous system to produce psychophysiological change, is not biofeedback because it acts on your body instead of providing you with information about its performance. For example, a physical therapist might treat back pain through a modality called muscle stimulation. A current delivered to postural muscles fatigues them so that they cannot produce painful spasms. After muscle stimulation brings spasms under control, a physical therapist can initiate surface electromyographic (SEMG) biofeedback to teach the patient to increase awareness and control of postural muscle contraction. Graphic © DreamBig/Shutterstock.com.

Similarly, various devices that input signals into the central nervous system are not biofeedback devices but are generally known as entrainment devices. These include Audio-Visual Entrainment (AVE), Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation (CES), repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS), repetitive Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (rTDCS), pulsed ElectroMagnetic Frequency Stimulation (pEMF), and others. These interventions may be useful and may provide an effective adjunct to biofeedback. However, since they do not provide information directly to the individual in a learning paradigm, they are not biofeedback. They represent treatment, not training. For this reason, providers should confirm that the use of these modalities falls within their scope of practice. An AVE device, is shown below.

Quantum Biofeedback and LenyosisTM

Slawecki (2009) cautioned consumers in "How to Distinguish Legitimate Biofeedback/Neurofeedback Devices."

The Sept. 3, 2009 Seattle Times published an exposé on pseudo-biofeedback devices: "Miracle Machines: The 21st-Century Snake Oil."

Appending biofeedback to a product's name does not make it biofeedback. Exposing clients to electromagnetic fields is modulation. Since biofeedback provides clients with real-time performance information to guide self-regulation, Quantum Biofeedback and LenyosysTM devices fall outside this definition.

Quantum Biofeedback

Quantum Biofeedback (EPFX / SCIO / XRROID / QXCI) devices do not provide individuals with immediate information regarding their performance. Marketers advertise that these instruments monitor, diagnose, and correct cellular abnormalities at a quantum level without providing peer-reviewed data. Critics claim that treatment with these devices may result in false diagnoses and delay effective treatment for medical disorders.

The following information was retrieved from the Empowering Change in You site on December 27, 2009. Note the disclaimer about "curing" medical conditions and explanation that it produces changes through stress management:

The function of the Quantum Biofeedback/EPFX is similar to a virus-scan on a computer. It focuses on your energetic body, which offers a more complete view of each facet of your health. Based on Quantum Physics, it runs a comprehensive test that measures the body’s frequencies. The system then contributes frequencies designed to resonate within the body, thus creating balance.

The human body is composed of a biochemical structure and an electromagnetic field. It performs best when these functions are balanced with one another and in complete harmony. Unfortunately, the daily stresses of life that confront each and every one of us takes its toll on the human body. Stress reduction is essential for wellness. This energy work is non-invasive.

It is important to remember that energetic medicine does not "cure" health problems. It addresses them specifically by making energetic corrections and rebalancing the system through stress management.

LenyosysTM

LenyosysTM describes its pulsed electromagnetic technology as a "body-biofeedback modality":Ideal as a complement to neurofeedback and biofeedback therapy, BRT is a body-biofeedback modality that helps to address the physical and somatic symptoms of both simple and complex health issues including digestive problems, systemic inflammation, muscle and joint aches, drug and alcohol addiction, allergies and hypersensitivities, stress, trauma and chronic illness. Whether used before, right after or in between sessions, BRT works in tandem with neurofeedback and biofeedback to create synergies that relax the client, enhance the therapy session and improve end results.

Pulsed electromagnetic treatment is modulation--not biofeedback. Instead of providing double-blind studies of their product's effectiveness, the marketers provide references for the application of Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy (PEMF) and magnetism for specific applications.

Glossary

adverse reactions: iatrogenic effects like anxiety and sedation associated with BFT and NFT.

biofeedback: (1) learning process that teaches an individual to control her physiological activity, (2) the aim of biofeedback training is to improve health and performance, (3) instruments rapidly monitor an individual's performance and display it back to her, (4) the individual uses this feedback to produce physiological changes, (5) changes in thinking, emotions, and behavior often accompany and reinforce physiological changes, and (6) these changes become independent of external feedback from instruments. Information about psychophysiological performance is obtained by noninvasive monitoring and used to help individuals achieve self-regulation through a learning process that resembles motor skill learning.

bottom-up interventions: training that directly targets peripheral nervous system networks.

central nervous system: the division of the nervous system that includes the brain, spinal cord, and retina.

classical conditioning: unconscious associative learning process that modifies reflexive behavior and prepares us to respond to future situations rapidly.

electroencephalograph: an instrument that measures brain electrical activity.

electromyograph: an instrument that measures skeletal muscle action potentials.

entrainment devices: instruments that input signals such as light, sound, or electricity into the central nervous system.

feedback: in cybernetic theory, orders to act to correct small errors to prevent larger future errors in a closed system.

feedforward: in cybernetic theory, orders to perform an action based on anticipated conditions in an open system.

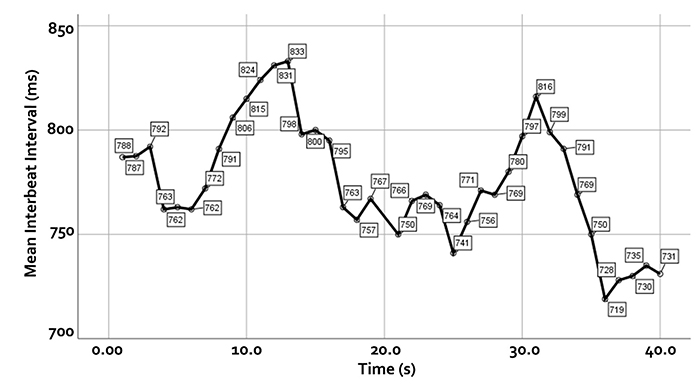

heart rate variability biofeedback: the display of beat-to-beat changes in heart rate that include changes in the RR intervals between consecutive heartbeats.

homeostasis: a state of dynamic constancy achieved by stabilizing conditions about a setpoint, whose value may change over time, proposed by Bernard and Cannon.

mindfulness: accepting and non-judgmental focus of attention on the present on a moment-to-moment basis.

modulation: stimulating the nervous system to produce psychophysiological change.

neurofeedback: information about EEG activity obtained by noninvasive monitoring and used to help individuals achieve self-regulation through a learning process that resembles motor skill learning.

operant conditioning: an unconscious associative learning process that modifies the form and occurrence of voluntary behavior by manipulating its consequences.

peripheral nervous system: nervous system subdivision that includes autonomic and somatic branches.

physiological monitoring: measurement of biological activity like EEG activity.

self-regulation: control of your behavior (e.g., voluntary increase in low-beta amplitude).

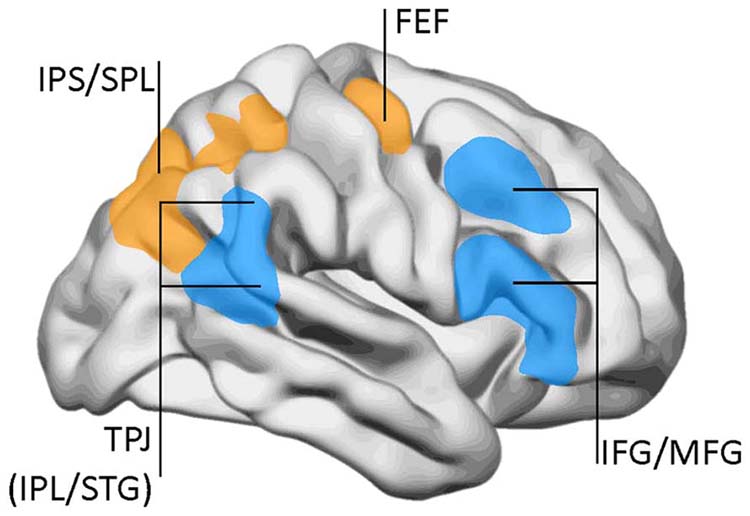

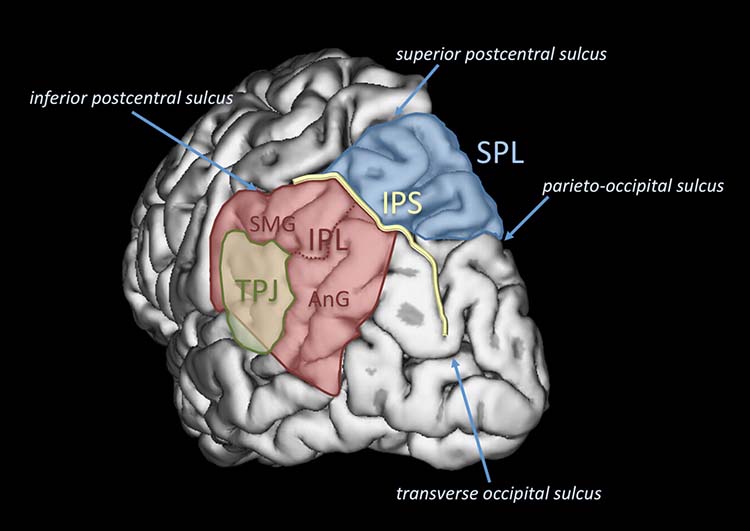

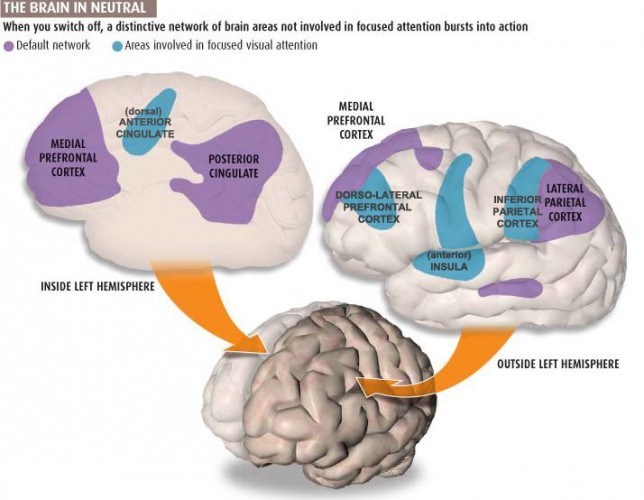

top-down interventions: training that directly targets central nervous system frontal, parietal, and limbic networks.

REVIEW FLASHCARDS ON QUIZLET

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, how would you explain neurofeedback to a client? How would you explain the relationship between biofeedback and neurofeedback training?

References

Biofeedback Certification International Alliance (2016). Blueprint of knowledge statements for board certification in neurofeedback. Retrieved from http://www.bcia.org/files/public/EEGBlueprint.pdf

Collura, T. F. (2014). Technical foundations of neurofeedback. Routledge.

Hammond, D. C., & Kirk, L. (2008). First, do not harm: Adverse effects and the need for practice standards in neurofeedback. Journal of Neurotherapy, 12(1), 79-88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874200802219947

International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (2016). Definition of neurofeedback. Retrieved from http://www.isnr.org/#!neurofeedback-introduction/c18d9

Khazan, I. (2013). The clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Khazan, I. (2019). Biofeedback and mindfulness in everyday life: Practical solutions for improving your health and performance. W. W. Norton & Company.

Rogel, A., Guez, J., Getter, N., Keha, E., Cohen, T., Amor, T., & Todder, D. (2015). Transient adverse side effects during neurofeedback training: A randomized, sham-controlled, double blind study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 40(3), 209-218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-015-9289-6

Schwartz, M. S. (2010). A new improved universally accepted official definition of biofeedback: Where did it come from? Why? Who did it? Who is it for? What's next? Biofeedback, 24, 88-90. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-38.3.88

Takahashi, T. (2005). Activation methods. In E. Niedermeyer & F. Lopes da Silva (Eds.). Electroencephalography: Basic principles, clinical applications, and related fields (5th ed.). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Thompson, M., & Thompson, L. (2016). The neurofeedback book: An introduction to basic concepts in applied psychophysiology (2nd ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

B. HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF NEUROFEEDBACK

This section covers Early Antecedents, Cybernetic Theory, Operant Conditioning, The Evolution of EEG Rearch and Practice, Contributors To EEG Research, and Neurofeedback Research.

"History depends on who writes it and who survives it. It is shaped by those who promote it and those who contribute to it. The official history of American biofeedback started in 1969 at the Surf Rider Inn in Santa Monica, California. Barbara Brown, a Veterans Administration (VA) electroencephalography (EEG) researcher, organized this meeting and placed her feisty stamp on the field. Here, the separate threads of scientific research into the possibility of autoregulation and the autoregulation practices of millennia-old meditative techniques coalesced." (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 142)

Graphic from Biofeedback: Yoga of the West, narrated by Elmer Green and created by Hartley Productions.

The concept of self-regulation (voluntary control of biological processes) is ancient, despite our recent rediscovery of them. Hindus practiced systems of yoga more than 3,000 years ago in India. Before the term biofeedback was popularized in 1969, contributors repeatedly demonstrated this learning process without understanding its implications and broader application.

Claude Bernard (1865) proposed that the body strives to maintain a steady state (milieu interieur).

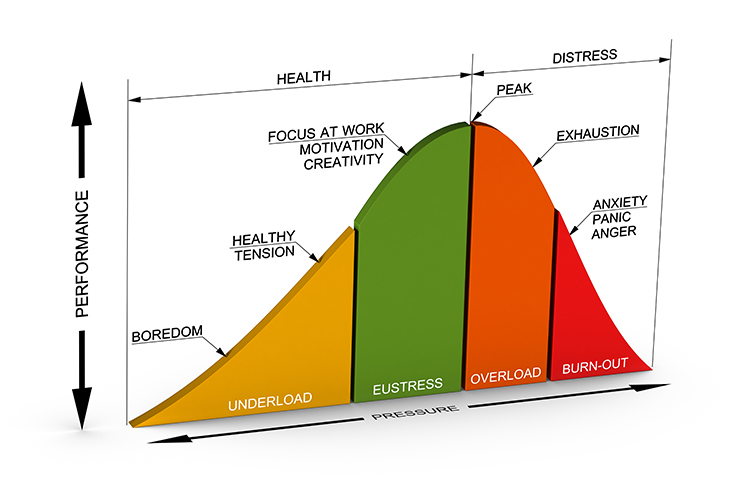

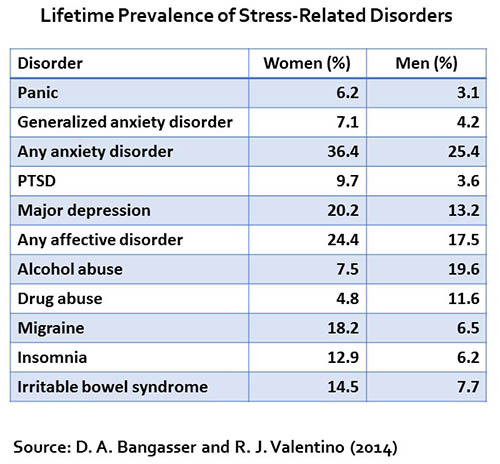

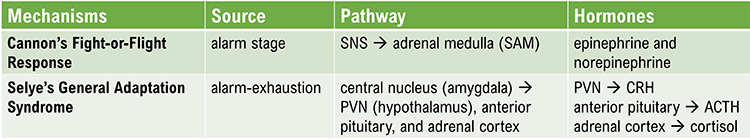

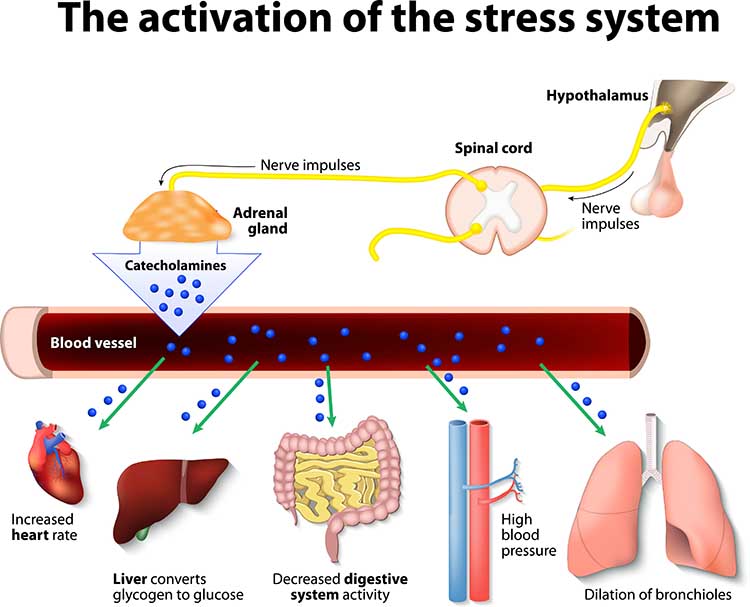

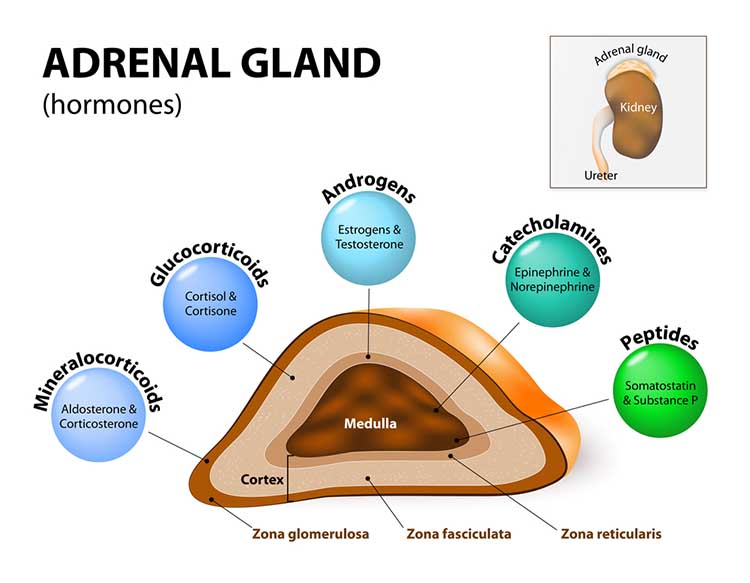

Walter Cannon (1914) expanded on this concept when discussing stress (a force that acts to disturb internal homeostasis) and homeostasis (a steady state).

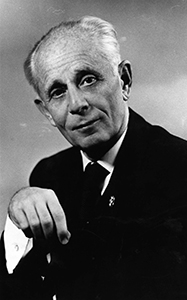

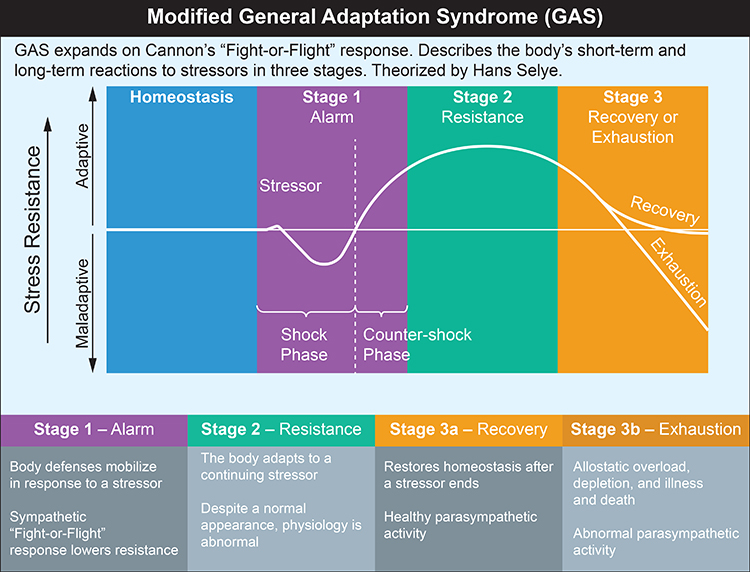

Hans Selye (1963) studied the endocrine effects of chronic stress, proposed the three-stage General Adaptation Syndrome, and popularized the term stress in The Stress of Life (1956).

Bell, Tarchanoff, and Bair pioneered the contemporary study of self-regulation.

Alexander Graham Bell (1872) studied teaching the deaf to speak using biofeedback.

He investigated Leon Scott's phonautograph, which translated sound vibrations into tracings on smoked glass to show their acoustic waveforms.

Bell also examined Koenig's manometric flame, which displayed sounds as patterns of light. The photographs below are from R. Victor Jones (Bruce, 1973).

Ivan Tarchanoff (1885) showed that voluntary control of heart rate could be reasonably direct (cortical-autonomic) and did not depend on "cheating" by altering breathing rate.

J. H. Bair (1901) studied voluntary control of the retrahens muscle that wiggles the ear. He found that subjects learned this skill by inhibiting interfering muscles. This was a solid demonstration of skeletal muscle self-regulation.

Cybernetic Theory

Norbert Wiener (1948) developed cybernetic theory that proposed that systems are controlled by monitoring their results. Your home heating system is an excellent example of a cybernetic system. Cybernetic theory contributed concepts like system variable (what is controlled), setpoint (goal), feedback (corrective instructions), and feedforward (instructions based on anticipated conditions).

At the landmark 1969 conference at the Surfrider Inn in Santa Monica, the participants coined the term biofeedback from Weiner's feedback (Moss, 1998).

"This group needed a name, and the two candidates were biofeedback and autoregulation. Just before the final vote, someone in the audience yelled out that autoregulation sounded like government control of cars. This spontaneous comment created a tipping point, the consensus shifted to biofeedback, and the Biofeedback Research Society (BRS) was born." (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 142)

Operant Conditioning

Edward Thorndike (1911) advanced the term instrumental learning to describe voluntary responses that obtain a desired outcome. His law of effect proposed that successful responses are mechanically stamped in by their successful consequences.

B. F. Skinner's (1938) operant conditioning research expanded on Thorndike's law of effect. He argued that animals repeat responses followed by favorable consequences based on extensive laboratory findings.

Skinner introduced several concepts that have influenced biofeedback theory. Reinforcement is a process where the consequence of a voluntary response increases the likelihood it will be repeated. Consequences that strengthen responses are called reinforcers. Punishment is a process that actively suppresses responses. A negative consequence such as a punishment following a voluntary response decreases the likelihood that the response will be repeated. Consequences that weaken responses are called punishers.

Based on Skinner's work, researchers used operant theory to divide physiological responses into those that could be voluntarily controlled and those that could not. "From its inception, biofeedback had to overcome the entrenched paradigm that individuals could not voluntarily control autonomic functions. Researchers who applied B. F. Skinner's work to biofeedback used operant theory to determine which responses could be voluntarily controlled and which could not. For example, Kimble (1961) argued that although subjects could learn to consciously control skeletal muscle responses, autonomic processes (such as heart rate) were involuntary, could be only classically conditioned, and were forever outside of conscious control. This perspective ignored the almost 3,000-year-old yogic practice of autonomic control and research by Lisina (1958); Lapides, Sweet, and Lewis (1957); and Kimmel (1967) that demonstrated voluntary control of autonomic responses." (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 143)

The Evolution of EEG Research and Practice

1800s to 1940s

Early EEG equipment was imprecise and only minimally helpful in studying neuroanatomy and neurophysiology.

1960 to 1985

Environmental artifacts readily contaminated clinical EEG biofeedback devices. Excessive expectations and media hype over alpha training contributed to the perception that EEG biofeedback was not a viable modality. Biofeedback shifted to autonomic and skeletal muscle biofeedback. The minority of professionals who continued investigating and clinically using EEG biofeedback operated within an often unsupportive and hostile scientific environment.

2005-Present

The development of affordable, powerful digital computer technology, micro-electronics, more accurate sensors, and normative databases has enabled the average trainer to provide neurofeedback training. The increased portability and turn-key operation of EEG systems have enabled their use in both clinic and home environments.

Contributors To EEG Research

Luigi Galvani (1791) reported electrical currents in animals (Swartz & Goldensohn, 1998).

This finding was confirmed by Giovanni Aldini (1794) and Freiherr (baron) von Humboldt (1797).

Ernst Fleischl von Marxow (1833) recorded visual cortical potentials (cortical potentials evoked by visual stimuli) but did not describe rhythmic oscillation (Niedermeyer, 1993).

Emil du Bois-Reymond (1849) reported electrical conduction in muscles and peripheral nerves (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011).

Theodore Fritsch and Julius Eduard Hitzig (1858) discovered that cortical stimulation elicits a localized motor response (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011).

_AB.1.0435_Hitzig_CROPPED.tif.jpg)

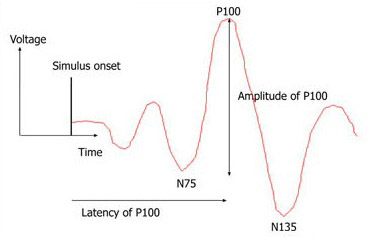

Richard Caton (1875) was an English physician who discovered electrical potentials in vivisected animals. He recorded spontaneous electrical potentials from the exposed cortical surface of monkeys and rabbits. He was the first to measure evoked potentials (EPs), which are EEG responses to stimuli (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011).

A visual evoked potential (VEP) is shown below.

He also reported the first observations of the shift of the cortical gradient to electro-negative during activation.

Vasili Yakovlevic Danilewsky (1877) published Investigations in the Physiology of the Brain, which explored the relationship between the EEG and states of consciousness (Brazier, 1959).

Adolf Beck (1891) published studies of spontaneous electrical potentials detected from the brains of dogs and rabbits. He was the first to document alpha blocking, where sensory stimulation blocks rhythmic oscillations (Coenen et al., 1998).

Sir Charles Sherrington (1906) introduced the terms neuron and synapse and published the Integrative Action of the Nervous System. He made significant contributions to understanding muscle action, movement, proprioception, reflexes, and spinal nerves (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011).

Sherrington proposed the "enchanted loom" metaphor for the human brain in a passage in the 1942 Man on His Nature, in which he poetically described the change in cortical activity as we awaken:

"The great topmost sheet of the mass, that where hardly a light had twinkled or moved, becomes now a sparkling field of rhythmic flashing points with trains of traveling sparks hurrying hither and thither. The brain is waking and with it the mind is returning. It is as if the Milky Way entered upon some cosmic dance. Swiftly the head mass becomes an enchanted loom where millions of flashing shuttles weave a dissolving pattern, always a meaningful pattern though never an abiding one; a shifting harmony of subpatterns." (p. 178)"

Current sleep research shows that the cortical networks are considerably more active during sleep than Sherrington imagined.

Vladimir Pravdich-Neminsky (1912) photographed dogs' EEG and event-related potentials, demonstrated a 12-14 Hz rhythm that slowed during asphyxiation, and introduced the term electrocerebrogram (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011).

Napolean Cybulsky and Jelenska-Maciesyna (1914) recorded experimental seizures (Swartz & Goldensohn, 1998).

Alexander Forbes (shown below) and David W. Mann (1920) reported replacing the string galvanometer with a vacuum tube to amplify the EEG. The vacuum tube became the de facto standard by 1936 (Swartz & Goldensohn, 1998).

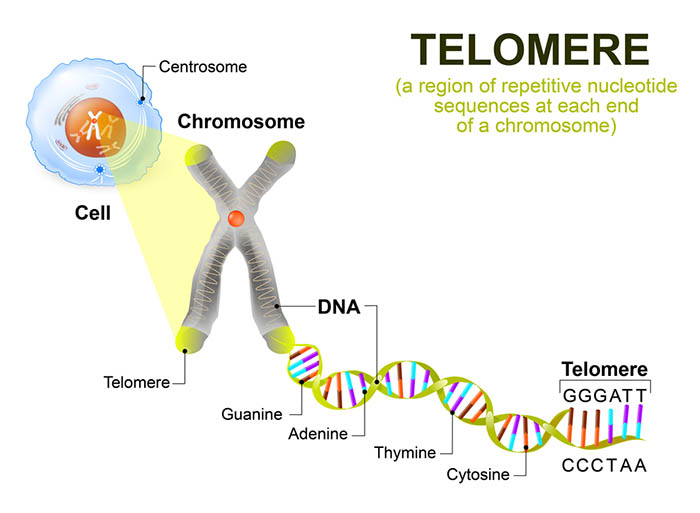

Hans Berger (1929) was an Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist who published the first human EEG recording. He published fourteen scientific papers from 1929 to 1938 (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011).

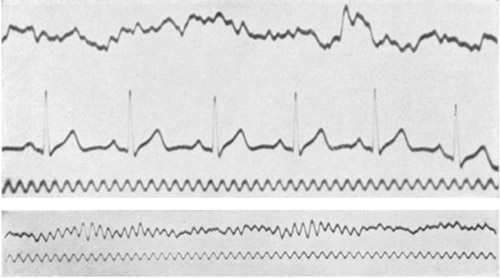

He described a pattern of oscillating electrical activity recorded from his son Klaus' scalp (see published samples below).

Berger showed that these potentials were not due to scalp muscle contractions. Berger discovered the alpha rhythm, the first EEG rhythm, and called it the Berger rhythm. He identified sleep spindles, which are short bursts of 12-15 Hz activity during stage 2 sleep. Berger viewed the EEG as analogous to the ECG because it generates an electrical signal that can be amplified and displayed. He introduced the term elektenkephalogram. He believed that the EEG had diagnostic and therapeutic promise in measuring the impact of clinical interventions.

He demonstrated that alterations in state (sleep/wake, eyes open/closed, drug/no drug, and illness/health) are associated with changes in the EEG. He associated the beta rhythm with alertness. He described interictal activity (EEG potentials between seizures) and recorded a partial complex seizure (impaired awareness and repetitive behaviors called automatisms) in 1933. Finally, he performed the first qEEG, which measures the signal strength of component EEG frequencies (Hassett, 1978; Robbins, 2000; Swartz & Goldensohn, 1998).

Edgar Douglas Adrian (shown below) and Bryan Matthews (1934) confirmed Berger's findings by recording their EEGs using a cathode-ray oscilloscope. Their demonstration of EEG recording at the 1935 Physiological Society meetings in England led to its widespread acceptance (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011)

Adrian provided evidence supporting the all-or-none law: action potentials initiated at the axon hillock either occur or not. When they occur, they have the same amplitude and speed. He used himself as a subject and demonstrated the phenomenon of alpha blocking, where opening his eyes suppressed alpha rhythms.

Matthews (shown below) developed the oscillograph and differential amplifier, which is used in modern biofeedback and neurofeedback amplifiers

M. H. Fisher and H. Lowenback (1935) provided the first demonstration of epileptiform spikes (sharp EEG transients with a duration of less than 70 ms) (Swartz & Goldensohn, 1998).

Erna Gibbs, Fredric A. Gibbs, H. Davis, and William G. Lennox inaugurated clinical electroencephalography in 1935 by identifying abnormal EEG rhythms associated with epilepsy, including interictal spike waves and 3-Hz activity in absence seizures, which involve periods of less than 15 s during which a client blanks out (Brazier, 1959). Erna and Frederick Gibbs were married and closely collaborated on their research, including developing a scale for rating beta spindles.

Erna and Frederic Gibbs (top) and William Lennox (bottom) are pictured below.

Frederic Bremer (1935) used the EEG to show how sensory signals affect vigilance and studied the sleep-wake cycle. He divided the EEG into standard-bandwidth Bremer bands: delta (0-4 Hz), theta (4-8 Hz), alpha (8-12 Hz), and beta (12-32 Hz) (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011).

Fredric A. Gibbs and Herbert H. Jasper (1936) showed that the interictal spike was the defining indicator of epilepsy (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011).

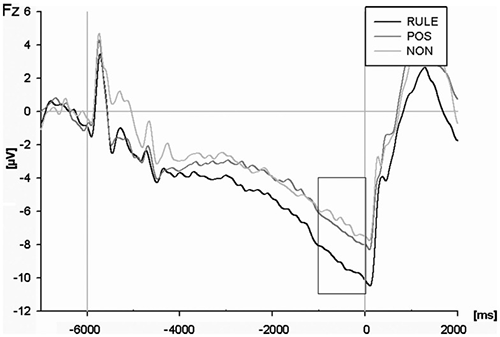

W. G. Walter (1940s) named the delta and theta waves and the contingent negative variation (CNV). This slow cortical potential may reflect expectancy, motivation, intention to act, or attention (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011).

Walter (shown below) located an occipital lobe source for alpha waves and demonstrated that delta waves could help find brain lesions like tumors. In 1946, he described electrical responses to photic stimulation (visual stimulation at a specific flash frequency).

He improved Berger's electroencephalograph and pioneered EEG topography (Bladin, 2006). EEG topography maps electrical activity across the brain surface, as shown below.

The British EEG society was established in 1942, and the American EEG society began in 1947.

Nathaniel Kleitman (1953) has been recognized as the "Father of American sleep research" for his seminal work in sleep-wake cycle regulation, circadian rhythms, the sleep patterns of different age groups, and the effects of sleep deprivation. Kleitman described the basic patterns of sleep cycles and connecting transitional states (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011).

He discovered the phenomenon of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep with his graduate student Eugene Aserinsky. Below is a sample of brainwave activity during REM sleep.

William C. Dement (1950s), another of Kleitman's students, described the EEG architecture and phenomenology of sleep stages and the transitions between them in 1955, associated REM sleep with dreaming in 1957, and documented sleep cycles in another species, cats, in 1958, which stimulated basic sleep research. He established the Stanford University Sleep Research Center, the first international sleep laboratory, in 1970. He has contributed to research on sleep deprivation and the diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders like apnea and narcolepsy (Niedermeyer & Schomer, 2011).

Kleitman and Dement advanced polysomnography by incorporating eye movement and the EEG during an entire night's sleep. These measurements enabled the study of sleep stages and behaviors like dreaming.

Per Andersen and S. A. Andersson (1968) proposed that thalamic pacemakers project synchronous 7-Hz alpha rhythms to the cortex via thalamocortical circuits and discovered the phenomenon of long-term potentiation (LTP). Per Anderson is shown below.

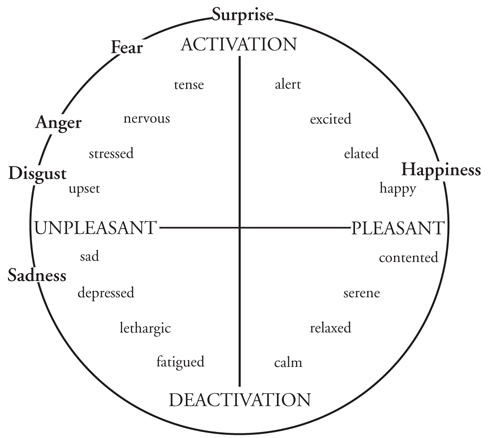

Neurofeedback Research

Joseph Kamiya (1960s) is considered the "Father of Neurofeedback." He demonstrated that the alpha rhythm in humans could be operantly conditioned. He published an influential article in Psychology Today that summarized research that showed that subjects could learn to discriminate when alpha was present or absent and that they could use feedback to shift the dominant alpha frequency by about 1 Hz. Almost half of his subjects reported experiencing a pleasant "alpha state" characterized as an "alert calmness." These reports may have contributed to the perception of alpha biofeedback as a shortcut to a meditative state. He also studied EEG activity during meditative states. Kamiya's research demonstrated a clinical application alpha-theta neurofeedback.

"Both the public and academic worlds recognize Joe Kamiya as the father of biofeedback. In 1966, while monitoring subjects' EEGs in his sleep lab at the University of Chicago, he performed a novel experiment by ringing a bell whenever an alpha burst occurred. He discovered that some subjects could discriminate when they produced alpha activity. His 1968 publication of 'Conscious Control of Brain Waves' in Psychology Today summarized research that showed that subjects could learn to discriminate when alpha was present or absent and that they could use feedback to shift the dominant alpha frequency about 1 Hz. Almost half of his subjects experienced a pleasant alpha state, which they characterized as an 'alert calmness.' Kamiya's article made biofeedback accessible to the public and made it exciting because it suggested that individuals can learn to control their own consciousness."

"Alpha biofeedback fit an emerging zeitgeist of self-exploration. American culture in the 1960s and 1970s was shaped by a confluence of forces: exploration of consciousness through drugs such as LSD (Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert) and Eastern meditative practices such as transcendental meditation (TM). Harvard physician Herbert Benson repackaged TM as the relaxation response without an overt spiritual dimension. Kamiya's work implied that a language of consciousness was possible and resulted in neurofeedback, one of the most promising areas of biofeedback." (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 143)

Barbara Brown (1970s) demonstrated the clinical use of alpha-theta biofeedback. In research designed to identify the subjective states associated with EEG rhythms, she trained subjects to increase the abundance of alpha, beta, and theta activity using visual feedback. Brown recorded their subjective experiences when the amplitude of these frequency bands increased. She also helped popularize biofeedback by publishing a series of books, including New Mind, New body (1974), Stress and the Art of Biofeedback (1977), and Supermind (1980). Brown was a co-founder and first President of the Biofeedback Research Society, which became the Biofeedback Society of America and then the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Thomas Mulholland and Erik Peper (1971) showed that occipital alpha increases with eyes open and not focused and is disrupted by visual focusing, a rediscovery of alpha blocking.

Elmer Green and Alyce Green (1969, 1970, 1977) investigated the voluntary control of internal states by individuals like Swami Rama and American Indian medicine man Rolling Thunder in India and at the Menninger Foundation. They brought portable biofeedback equipment to India and monitored practitioners as they demonstrated self-regulation. A film containing footage from their investigations was released as Biofeedback: The Yoga of the West (1974).

The Greens showed that, like the yogis they studied, ordinary individuals could learn self-regulation of "involuntary" physiological functions like blood pressure, the EEG, heart rate, skeletal muscle activity, and skin temperature.

They developed alpha-theta training at the Menninger Foundation from the 1960s to the 1990s. They hypothesized that theta states allow access to unconscious memories and increase the impact of prepared images or suggestions. Their alpha-theta research fostered Peniston's development of an alpha-theta addiction protocol.

They pioneered temperature biofeedback training for Raynaud's, migraine, and hypertension and wrote the classic Beyond Biofeedback (1977). They developed clinical biofeedback by applying these modalities to various disorders like hypertension and migraine.

Thomas Budzynski (1969, 1973) developed a twilight learning device that monitored left hemisphere EEG while a patient sleeps and played recorded educational content like language lessons and affirmations (positive statements) when theta was present. The premise of twilight learning is that affirmations have a greater impact when presented in a transitional state in which theta waves replace the alpha rhythm.

He studied the lateralization of brain function across the two cerebral hemispheres and the use of neurofeedback and audio-visual stimulation (brain brightening) to correct age-related cognitive decline.

M. Barry Sterman (1973) showed that cats and human subjects could be operantly trained to increase the amplitude of the sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) between 12-15 Hz recorded from the sensorimotor cortex.

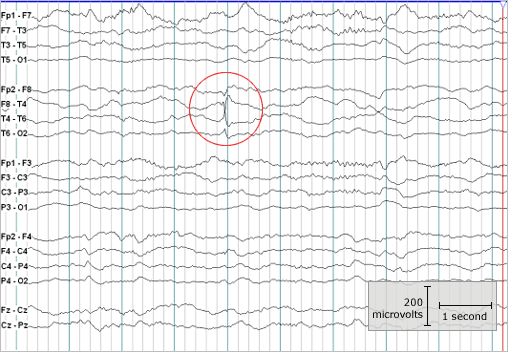

He demonstrated that SMR production protects cats against drug-induced generalized seizures (tonic-clonic seizures involving loss of consciousness) and reduces the frequency of seizures in humans diagnosed with epilepsy. He found that his SMR protocol, which uses visual and auditory EEG biofeedback, normalizes their EEGs (SMR increases while theta and beta decrease toward normal values) even during sleep. Generalized seizure activity is shown below.

Sterman conducted excellent research published in mainstream journals, which should have propelled SMR training into the forefront of seizure disorder treatment. Sterman also co-developed the Sterman-Kaiser (SKIL) qEEG database.

Joel Lubar (1970s) studied SMR biofeedback to treat attention disorders and epilepsy in collaboration with Sterman. He demonstrated that SMR training could improve attention and academic performance in children diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity (ADHD) at the University of Tennessee.

Lubar documented the importance of theta-to-beta ratios (the ratio of power in the theta and beta bands) in ADHD and developed theta suppression-beta enhancement protocols to decrease these ratios and improve student performance.

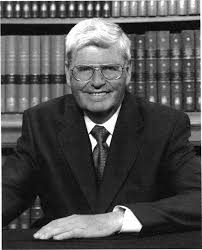

Erwin Roy John and Frank H. Duffy (1970s) collaborated in developing quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG) and its use in the assessment of disorders. John created neurometrics in which clients are compared to a normative database. Finally, John contributed to the study of memory and proposed that memory is distributed across the brain. John (left) and Duffy (right) are pictured below.

|

|

Jay Gunkelman's (Moss & Gunkelman, 2002) involvement in applied psychophysiology and biofeedback dates back to 1972 with the grant funding of the first state hospital-based biofeedback laboratory. Since the mid-1970s, he has specialized in the classical clinical EEG and is one of the world's most experienced EEG/qEEG specialists. He was instrumental in developing biofeedback and neurofeedback efficacy standards that have served as the foundation for the AAPB reference Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback. Jay has been one of the field's most influential educators and prolific authors.

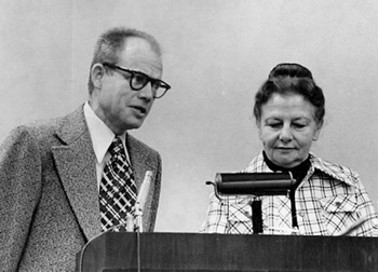

Michael and Lynda Thompson (2015) have been "master teachers as well as superb clinicians and clinical researchers. Over the years, their clinic has acquired a much deserved international reputation with clients from other countries seeking their expertise. Somehow they also manage to teach workshops on biofeedback and neurofeedback to other professionals in the field." Thomas Budzynski, PhD.

|

|

They wrote The Neurofeedback Book: An Introduction to Basic Concepts in Applied Psychophysiology which has been the "bible" of neurofeedback didactic education. In 2016, AAPB awarded Michael and Lynda its Distinguished Scientist award.

Margaret Ayers (1975) was an early neurofeedback pioneer, established the first private clinical practice that exclusively provided neurofeedback, and published the first papers on neurofeedback for treating traumatic brain injury. She developed digital real-time EEG monitoring technology and investigated seizure control and treatment of coma patients with open head wounds. Her neurofeedback protocol down-trained slow-wave activity and uptrained 15-18 Hz activity.

Niels Birbaumer and colleagues (1970s) have studied operant conditioning of slow cortical potentials (SCPs; gradual changes in the membrane potentials of cortical dendrites that last from 300 ms to several seconds) since the late 1970s. They have demonstrated that subjects can learn to control these DC potentials and have studied the efficacy of SCP biofeedback in treating ADHD, epilepsy, and schizophrenia. They have shown that negative SCPs improve cognitive performance while positive SCPs increase the seizure threshold. Finally, they explored applications for brain-computer interfaces.

William N. Kuhlman and B. J. Kaplan (1979) identified the stabilizing 9-11-Hz mu rhythm in human subjects, which they considered separate from the SMR. They replicated Sterman's SMR research to inhibit generalized seizures.

Sue and Siegfried Othmer (1985) worked with Margaret Ayers to resolve their son's epilepsy. They proposed that protocols be chosen based on symptom patterns and pioneered computer games designed to modify the EEG. They investigated infra-low feedback (ILF) training of SCPs.

|

|

Eugene Peniston (1989) studied with the Greens at the Menninger Foundation. He developed the Peniston-Kulkosky Protocol, which uses alpha-theta training to treat alcoholism and post-traumatic stress disorder.

This multimodal protocol incorporated alpha-theta neurofeedback that uptrained alpha (8-13 Hz) and theta (4-8 Hz), autogenic training, constructed visualizations, diaphragmatic breathing, guided imagery, systematic desensitization, and temperature biofeedback. The diverse suggestion techniques utilized to potentiate alpha-theta training have influenced the use of guided imagery and behavior change scenarios in current alpha-theta neurofeedback.

Peniston and Kulkovsky reported that 8 of 10 experimental patients who received their alpha-theta protocol for alcoholism maintained abstinence from alcohol after 12-18 months compared with none of 10 controls. The two experimental patients who relapsed showed significantly reduced tolerance for alcohol. Peniston published seminal articles concerning alpha-theta training.

Vincent Monastra published early qEEG studies concerning the theta/beta ratio in ADHD and neurofeedback treatment of ADHD. Along with Lubar and Linden, he developed the statistical basis for using theta/beta power ratio measurement as a marker for ADHD.

Robert Thatcher (2010) developed a quantitative EEG database known as the lifespan database (NeuroGuide). He published the Handbook of QEEG and EEG Biofeedback. He developed 2- and 4-channel z-score training, 19-channel surface and LORETA z-score NF training, and BrainSurfer.

Juri Kropotov, who holds doctoral degrees in theoretical physics, philosophy, and neurophysiology, studied event-related potentials, developed EEG amplifiers (Mitsar 201 and 202), and is a prolific author, including his 2009 book Quantitative EEG: Event-Related Potentials and Neurotherapy. He is affiliated with the Human Brain Institute (HBI) and developed WinEEG software, using the HBI normative database for EEG and ERP analysis. He received the USSR State Prize in 1985 and the Copernicus Prize by the Polish Neuropsychological Society in 2009.

Roberto Pasqual Marqui has contributed to functional brain mapping using EEG and magnetoencephalography, and the study of functional connectivity in brain networks. He developed the three-dimensional Low Resolution Electromagnetic Tomography (LORETA).

Glossary

absence seizure: a seizure usually lasting less than 15 s in which a client blanks out; also called petit mal seizures.

affirmations: positive statements like "Every day I am getting better in every way."

all-or-none law: action potentials either occur or not. When they occur, they have the same amplitude and speed.

alpha blocking: replacement of the alpha rhythm by low-amplitude desynchronized beta activity during movement, attention, mental effort like complex problem-solving, and visual processing.

alpha rhythm: the first EEG rhythm discovered by Berger that ranges from 8 to 12 Hz which appears in three-quarters of adults when they are calm, awake, and not actively processing information.

alpha-theta training: training to progressively slow the EEG, increasing alpha and then theta abundance, developed by Brown and the Menninger Foundation and then adopted by Peniston and Kulkovsky in treating alcoholics.

beta rhythm: the second EEG rhythm discovered by Berger, 12-16 Hz.

biofeedback: information about psychophysiological performance obtained by noninvasive monitoring and used to help individuals achieve self-regulation through a learning process that resembles motor skill learning.

complex partial seizure: a seizure in which awareness is impaired and repetitive behaviors called automatisms (e.g., lip smacking) may occur.

contingent negative variation (CNV): a steady, negative shift in potential (15 microvolts in young adults) detected at the vertex discovered by Walter. This slow cortical potential may reflect expectancy, motivation, intention to act, or attention. The CNV appears 200-400 ms after a warning signal (S1), peaks within 400-900 ms, and sharply declines after a second stimulus that requires the performance of a response (S2).

cortical gradient: the difference in electrical charge between cortical neurons and scalp electrodes. When cortical networks are activated, their neurons are positively charged, and scalp electrodes are negatively charged.

curare: a paralytic drug used by Miller and DiCara to prevent rats from "cheating" by using skeletal muscles during operant conditioning of heart rate, blood pressure, kidney blood flow, skin blood flow, and intestinal contraction.

cybernetic theory: Weiner proposed that living systems are controlled by monitoring their results.

delta rhythm: EEG rhythm named by Walter that ranges from 0.5 to 3.5 Hz and is increased in adult Stage 3 sleep, brain injury, brain tumor, and developmental disability.

dysponesis: Whatmore and Kohli's concept of misplaced effort. For example, bracing your shoulders when you hear a loud sound.

EEG topography: the display that maps EEG activity across the brain surface in color.

evoked potentials: brain electrical potentials that are elicited by sensory stimulation.

feedback: in cybernetic theory, orders to correct small errors to prevent larger future errors in a closed system.

feedforward: in cybernetic theory, orders to perform an action based on anticipated conditions in an open system.

generalized seizures: seizures characterized by a peculiar cry, loss of consciousness, falling, tonic-clonic convulsions of all extremities, incontinence, and amnesia for the episode. These were previously called grand mal seizures.

homeostasis: a steady internal state proposed by Bernard and Cannon.

instrumental learning: operant conditioning, an unconscious associative learning process that modifies the form and occurrence of voluntary behavior by manipulating its consequences.

interictal activity: EEG potentials between seizures.

manometric flame: a device developed by Koenig and studied by Alexander Graham Bell for teaching the deaf to speak that displayed sounds as patterns of light.

motor unit: alpha motor neuron and the skeletal muscle fibers it controls.

neuron: an excitable nervous system cell that processes and distributes information, chemically and electrically, and usually contains a soma (cell body), dendrites, and axon.

normative database: means and standard deviations for EEG variables such as amplitude, power, coherence, and phase that are calculated for single hertz bins, frequency bands, or band ratios based on the EEG data collected from healthy normal subjects who are grouped by age, eyes open or eyes closed conditions, and sometimes gender and task, which also allows for the specification of z-scores with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 for the various combinations of EEG variables, frequency ranges, subject ages, eyes-open or eyes-closed conditions and other variables.

operant conditioning: an unconscious associative learning process that modifies the form and occurrence of an operant behavior (emitted behavior) by manipulating its consequences.

Peniston-Kulkovsky addiction protocol: a multimodal approach that incorporates visualization training, temperature biofeedback, rhythmic breathing techniques, autogenic training exercises, construction of personalized imagery, guided imagery, and 30 alpha-theta sessions.

phonautograph: a device developed by Leon Scott and studied by Alexander Graham Bell to teach the deaf to speak, translating sound vibrations into tracings on smoked glass to show their acoustic waveforms.

photic stimulation: visual stimulation at a specific flash frequency.

punisher: a consequence that weakens an operant behavior. For example, shoulder pain (punisher) following excessive exercise (operant behavior) may reduce exercise intensity.

punishment: in operant conditioning, the consequence of an operant behavior reduces its probability.

quantitative EEG (qEEG): digitized statistical brain mapping using at least a 19-channel montage to measure EEG amplitude within specific frequency bins.

reinforcement: in operant conditioning, the consequence of an operant behavior increases its probability.

reinforcer: a consequence that strengthens an operant behavior. For example, weight loss (reinforcer) following daily walks (operant) may increase the probability of walking.

self-regulation: the control of your behavior (voluntary hand-warming).

sensorimotor rhythm (SMR): EEG rhythm that ranges from 12-15 Hz and appears when you inhibit movement and relax your muscles.

setpoint: the system goal, for example, a thermostat setting of 75 degrees F (23.9 degrees C).

sleep spindles: short bursts of 12-15 Hz activity during stage 2 sleep.

slow cortical potentials (SCPs): gradual changes in the membrane potentials of cortical dendrites that last from 300 ms to several seconds. These potentials include the contingent negative variation (CNV), readiness potential, movement-related potentials (MRPs), and P300 and N400 potentials. SCPs modulate the firing rate of cortical pyramidal neurons by exciting or inhibiting their apical dendrites. They group the classical EEG rhythms using these synchronizing mechanisms.

spike: a sharp EEG transient with a duration of less than 70 ms.

stress: Selye's concept of a nonspecific response to stimuli called stressors.

synapse: specialized chemical and electrical junctions across which neurons communicate with each other and non-neural cells.

system variable: the variable that is controlled. For example, room temperature is the system variable for a thermostat.

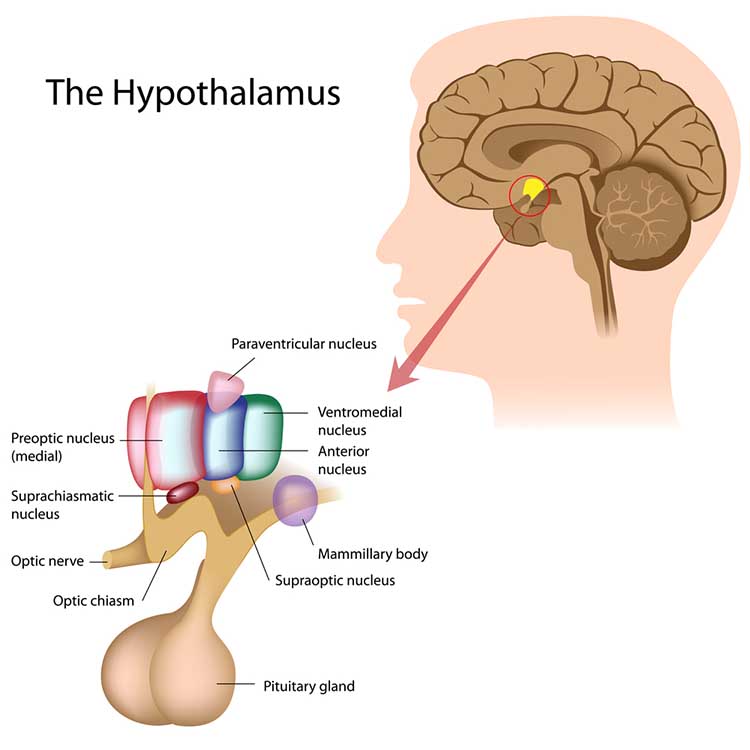

thalamus: a forebrain structure above the hypothalamus that receives, filters, and distributes most sensory information. The thalamus contains neurons that can block or relay ascending sensory information. When these thalamic neurons rhythmically fire, this blocks the transmission of information to the cortex. When they depolarize in response to sensory information, this integrates and transmits this information to the cortex. Inputs to the thalamus determine whether these neurons block or relay sensory information.

theta rhythm: the EEG rhythm discovered by Walter that ranges from 4 to 7 Hz and is associated with drowsiness, the transition from wakefulness to sleep, rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and the processing of information.

theta/beta training: a protocol that decreases theta amplitude and increases beta amplitude.

theta-to-beta ratio: the ratio of power in the theta and beta bands.

twilight learning: Budzynski's training paradigm in which recorded material is played when theta activity replaces alpha activity.

visual cortical potentials: brain electrical potentials evoked by visual stimuli like flashing lights.

z-score training: a strategy that attempts to normalize brain function with respect to mean values in a clinical database. EEG amplitudes that are 2 or more standard deviations above or below the database means are down-trained or uptrained to treat symptoms and improve performance.

REVIEW FLASHCARDS ON QUIZLET

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

From your perspective, which EEG researcher contributed most to the development of neurofeedback? Why?

References

Adrian, E. D., & Mathews, B. H. C. (1934). The Berger rhythm. Brain, 57, 355-385. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/57.4.35

Andersen, P., Andersson, S. A. (1968). Physiological basis of alpha rhythm. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Andreassi, J. L. (2007). Psychophysiology: Human behavior and physiological

response (5th ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, Inc.

Ayers, M. E. (1995). EEG neurofeedback to bring individuals out of level 2 coma [Abstract]. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 20(3), 304-305.

Ayers, M. E. (1995). Long-term follow-up of EEG neurofeedback with absence seizures. Biofeedback & Self-Regulation, 20(3), 309-310.

Berger, H. (1920). Ueber das elektroenkephalogramm des menschen. Archiv für Psychiatrie und

Nervenkrankheiten, 87, 527-570.

Bernard, C. (1957). An introduction to the study of experimental medicine. Dover. (Originally

published, 1865.)

Birbaumer, N., Elbert, T., Lutzenberger, W., Rockstroh, B., & Schwarz, J. (1981). EEG and slow cortical potentials in anticipation of mental tasks with different hemispheric involvement. Biol Psychol, 13, 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-0511(81)90040-5

Bladin, P. F. (2006). W. Grey Walter, pioneer in the electroencephalogram, robotics, cybernetics, artificial intelligence. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 13(2), 170-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2005.04.010

Bokser, I. O. (1999). History of creation of the doctrine, equipment and methods of formation of biological feedback. Med Tekh, 4,

44-46.

PMID: 10464764

Brazier, M. A. B. (1959). The EEG in epilepsy: A historical note. Epilepsia, 1(1-5), 328-336. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1157.1959.tb04270.x

Brazier, M.A.B. (1961). A history of the electrical activity of the brain. The first half-century. Pitman.

Bremer, F. (1935). Cerveau isole et physiologie du sommeil. Com Ren Soc Bio (Paris), 118, 1235-1241.

Brown, B. (1974). New mind, new body. Harper & Row.

Brown, B. (1977). Stress and the art of biofeedback. Harper &

Row.

Brown, B. (1980). Supermind: The ultimate energy. Harper &

Row.

Bruce, R. V. (1973). Bell: Alexander Graham Bell and the conquest of solitude. Gollancz.

Caton, R. (1875). The electric currents of the brain. British Medical Journal, 2, 278.

Coenen, A. M. L., Zajachkivsky, O., & Bilski, R. (1998). Scientific priority of A. Beck in the neurophysiology.

Experimental and Clinical Physiology and Biochemistry, 1, 105-109.

Cybusky, N., & Jelenska-Macieszyna, X (1914). Action currents of the cerebral cortex [in Polish]. Bull Acad Sci Cracov, B, 776–781.

Dement, W. (2000). The promise of Sleep: A pioneer in sleep medicine explores the vital connection between

health, happiness, and a good night’s sleep. Random House.

Evans, J. R., & Abarbanel, A. (1999). Introduction to quantitative EEG

and neurofeedback. Academic Press.

Fahrion, S., Norris, P., Green, A., Green, E., & Snarr, C. (1986). Biobehavioral treatment of essential hypertension: A group outcome study. Biofeedback-and-Self-Regulation, 11(4), 257-277.

Flor, H. (2002). Phantom-limb pain: characteristics, causes, and treatment. The Lancet, Neurology, 1(3),

182-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(02)00074-1

Goldensohn, E. S., Porter, R. J., & Schwartzkroin, P.A. (1997). The American Epilepsy Society: An historic perspective on 50 years of advances in research. Epilepsia, 38(1), 124–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01088.x

Green, E. E., Walters, E. D., Green, A. M., & Murphy, G. (1969). Feedback technique for deep relaxation.

Psychophysiology, 6 (3), 371-377.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1969.tb02915.x

Green, E., & Green, A. (1977). Beyond biofeedback. Delacorte Press.

Green, E., Green, A. M., & Walters, E. D. (1970). Self-regulation of

internal states. In J. Rose (Ed.), Progress of cybernetics:

Proceedings of the First International Congress of Cybernetics,

London, September 1969 (pp. 1299-1318). Gordon and Breach

Science Publishers.

Green, E., Green, A. M., & Walters, E. D. (1970). Voluntary control of

internal states: Psychological and physiological. Journal of

Transpersonal Psychology, 2, 1-26.

Kamiya, J. (1969). Operant control of

the EEG alpha rhythm. In C. Tart (Ed.), Altered states of

consciousness. Wiley.

Kleitman, N. (1960). Patterns of dreaming. Scientific American, 203(5), 82-88. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1160-82

Lubar, J. F. (1989). Electroencephalographic biofeedback and

neurological applications. In J. V. Basmajian (Ed.), Biofeedback:

Principles and practice for clinicians (3rd ed.), pp. 67-90.

Williams and Wilkins.

Lubar, J. F. (1991). Discourse on the development of EEG diagnostics and

biofeedback treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders.

Biofeedback and Self-regulation, 16, 201-225. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01000016

Lubar, J. F., & Shouse, M. N. (1977). Use of biofeedback in the

treatment of seizure disorders and hyperactivity. In B. B. Lahey & A. E.

Kazdin (Eds.), Advances in clinical child psychology (pp.

203-265). NY: Plenum Press.

McKnight, J. T., & Fehmi, L. G. (2001). Attention and neurofeedback

synchrony training: Clinical results and their significance. Journal

of Neurotherapy, 5. https://doi.org/10.1300/J184v05n01_05

Miller, N. E. (1969). Learning of visceral and glandular responses.

Science, 163, 434-445. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.163.3866.434

Miller, N. E. (1978). Biofeedback and visceral learning. Annual

review of psychology, 29, 373-404. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.29.020178.002105

Miller, N. E., & DiCara, L. (1967). Instrumental learning of heart rate changes in curarized rats: Shaping and specificity to discriminative stimulus. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology,

63, 12-19. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/h0024160

Miller, N. E., & Dworkin, B. (1974). Visceral learning: Recent

difficulties with curarized rats and significant problems for human

research. In P. A. Obrist; A. H. Black, J. Brener, & L. V. DiCara (Eds.),

Cardiovascular psychophysiology (pp. 312-331). Aldine.

Moss, D., & Gunkelman, J. (2002). Task force report on methodology and empirically supported treatments: Introduction and summary. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 27 (4), 261-262. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021009301517

Mulholland, T., & Peper, E. (1971). Occipital alpha and accommodative vergence, pursuit tracking, and fast eye movements. Psychophysiology, 8, 556-575. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1971.tb00491.x

Niedermeyer, R., & Schomer, D. L. (2011). Historical aspects of EEG. In D. L. Schomer & F. Lopes da Silva (Eds.). Niedermeyer's Electroencephalography: Basic principles, clinical applications, and related fields (6th ed.). Lipincott Williams & Wilkins.

O’Leary, J. L., & Goldring, S. (1976). Science and epilepsy. Raven Press.

Peper, E., & Shaffer, F. (2010). Biofeedback history: An alternative view. Biofeedback, 38(4),

142-147.

https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-38.4.03

Pravdich-Neminsky, V. V. (1913). Ein versuch der registrierung der elektrischen gehirnerscheinungen. Zbl Physiol

27, 951–960.

Robbins, J. (2000). A symphony in the brain. Atlantic Monthly Press.

Sherrington, C. S. (1906). The integrative action of the nervous system. Yale University

Press.

Sherrington, C.S. (1942). Man on his nature. Cambridge University Press.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. Appleton-Century.

Sterman, M. B. (1973). Neurophysiologic and clinical studies of sensorimotor EEG biofeedback training: Some effects on epilepsy. Seminars in Psychiatry, 5, 507-524.

Swartz, B. E., & Goldensohn, E. S. (1998). Appendix: Time of the history of EEG and associated fields. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 106, 173-176. PMID: 9741779

Thompson, M., & Thompson, L. (2016). The neurofeedback book: An introduction to basic concepts in applied

psychophysiology (2nd ed.). The Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Thorndike, E. (1911). Animal intelligence: Experimental studies. The Macmillan Company.

Walter, W. G. (1937). Electroencephalogram in cases of cerebral tumour. Proceedings of the Royal Society of

Medicine, 30, 579-578. PMID: 19991061

Walter, W. G. (1953). The living brain. Norton.

Walter, W. G., Cooper, R., Aldridge, V. J., McCallum, W. C., & Winter, A. L. (1964). Contingent negative variation: An electric sign of sensorimotor association and expectancy in the human brain. Nature, 203,

380-384. https://doi.org/10.1038/203380a0

Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics: Or control and communication in the animal and the machine.

MIT Press.

C. OVERVIEW OF PRINCIPLES OF HUMAN LEARNING AS THEY APPLY TO NEUROFEEDBACK

This unit covers Three Main Types of Learning, Classical Conditioning, Operant Conditioning, Nonassociative Learning, Observational Learning, and Critical Elements in Neurofeedback Training.

Learning

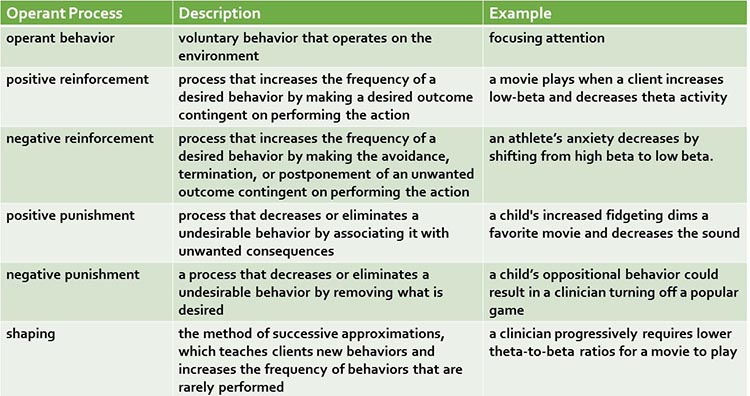

A movie plays when a child increases low beta and decreases theta activity (positive reinforcement). A score counter stops reversing when a child focuses on a reading selection after several minutes of distraction (negative reinforcement). The training goal becomes progressively more demanding as the child succeeds (shaping).

Sherlin et al. (2011) emphasized the importance of learning theory in neurofeedback: "It is our contention that future applications in clinical work, research, and development should not stray from the already-demonstrated basic principles of learning theory until empirical evidence demonstrates otherwise." (p. 292)

We can divide learning into three main categories: associative, nonassociative, and observational. Associative learning and observational learning are most relevant to neurofeedback. In associative learning, we create connections between stimuli, behaviors, or stimuli and behaviors. Associative learning aids our survival since it allows us to predict future events based on our experience. Learning that B follows A provides us with time to prepare for B. Two forms of associative learning are classical conditioning and operant conditioning (Cacioppo & Freberg, 2016).

Classical Conditioning

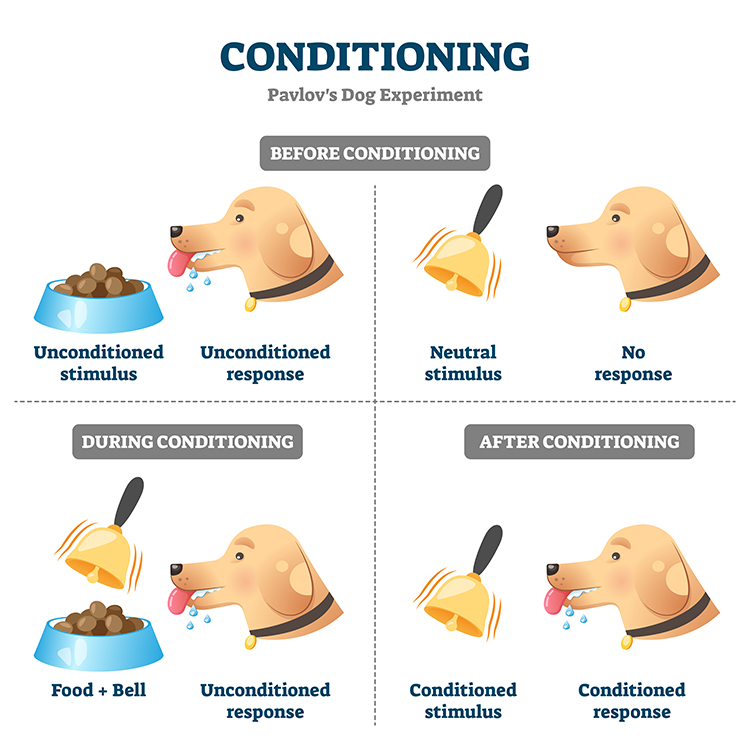

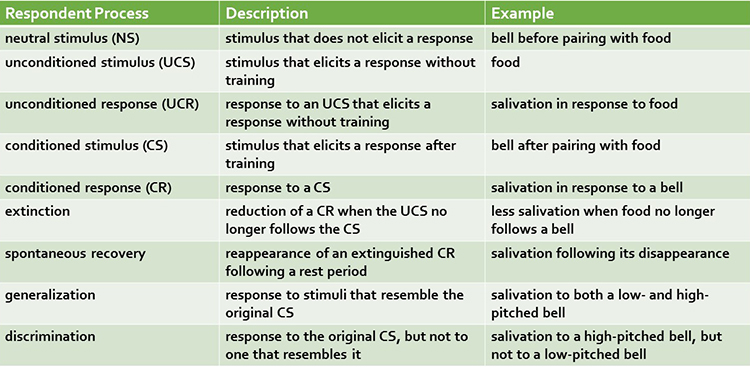

Pavlov demonstrated classical conditioning in 1927 based on his famous research with dogs. Due to faulty English translations, we now use the adjectives conditioned and unconditioned instead of conditional and unconditional. We will use the current terminology to minimize confusion.

Classical conditioning is an unconscious associative learning process that builds connections between paired stimuli that follow each other in time. Through this learning process, a dog in Pavlov's laboratory learned that if A (a ringing bell) occurs, B (food) will follow. The ability to predict the future from experience is crucial to our survival since it gives us time to prepare.

Before learning to anticipate food in Pavlov's laboratory, dogs salivated (unconditioned response) when they saw food (unconditioned stimulus). An unconditioned response (UCR) follows an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) before conditioning. However, until the dogs learned to associate the sound of a bell with food delivery, the bell was a neutral stimulus (NS) that did not elicit salivation.

Through the repeated pairing of the bell with the arrival of food, Pavlov's dogs learned that the bell reliably signaled the arrival of food. The bell became a conditioned stimulus (CS) that elicited the conditioned response (CR) of salivation. Graphic © VectorMine/iStockphoto.com.

When the association between the CS and CR is disrupted because B no longer consistently follows A, the frequency of the CR may decline or the CR may disappear. This phenomenon is called extinction. In Pavlov's situation, repeated trials where food did not follow bell ringing reduced or eliminated salivation. The extinction of CRs allows us to adapt to changes in our experience. You learn to use passwords less predictable than "password" after becoming a victim of identity theft. You can to play with dogs, again, after you were bitten as a child.

Pavlov argued that extinction is not forgetting but evidence of new learning that overrides previous learning. The phenomenon of spontaneous recovery, where the CR (salivation) reappears after some time without exposure to the CS (bell), supports his position. Dogs who stopped salivating by the end of an extinction trial in which no food followed the bell resumed salivating during a break or the next session.

Generalization and discrimination are mirror images of each other. In generalization, the conditioned response is elicited by stimuli (low-pitched bell) that resemble the original conditioned stimulus (high-pitched bell). Generalization promotes our survival because it allows us to apply learning about one stimulus (lions) to similar predators (tigers) without experiencing them.

In contrast, in discrimination, the conditioned response (salivation) is elicited by one stimulus (high-pitched bell) but not another (low-pitched bell). When soldiers return to civilian life, they must distinguish between a CS that signals danger (gunfire) and one that is benign (fireworks). Discrimination is often impaired in soldiers diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Operant Conditioning

Edward Thorndike's (1913) law of effect proposed that the consequences of behavior determine its addition to your behavioral repertoire. From his perspective, cats learned to escape his "puzzle boxes" by repeating successful actions and eliminating unsuccessful ones.

Operant conditioning is an

unconscious associative learning process that modifies an operant behavior, voluntary behavior that operates on the environment to produce an outcome, by manipulating its

consequences (Miltenberger, 2016).

Operant conditioning differs from

classical conditioning in several respects. Where operant conditioning teaches the association of a voluntary behavior with its consequences, classical conditioning teaches the predictive relationship between two stimuli to modify involuntary behavior.

Neurofeedback teaches self-regulation of neural activity and related "state changes" using operant conditioning via the selective presentation of reinforcing stimuli, including visual, auditory, and tactile displays.

Operant conditioning occurs with a situational context. The identifying characteristics of a situation are called

its

discriminative stimuli and can include

the physical environment and physical, cognitive, and emotional cues. Discriminative stimuli teach us when to

perform operant behaviors.

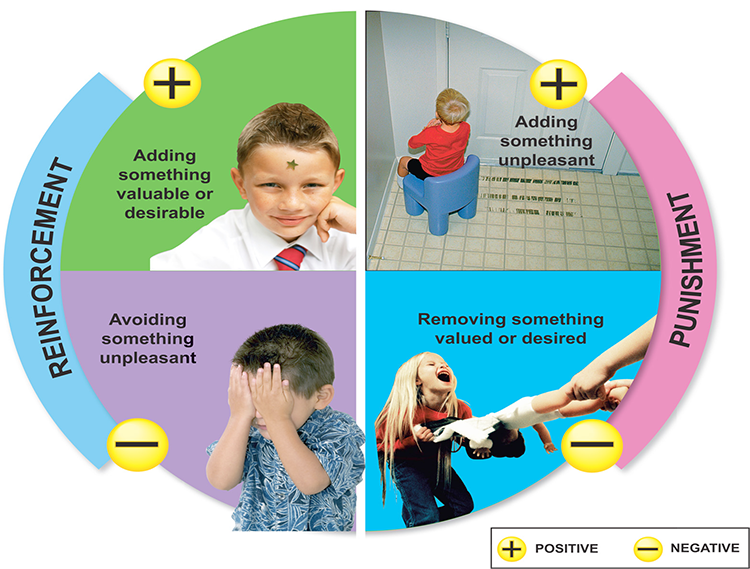

The consequences of operant behaviors can increase or decrease their frequency. Skinner proposed four types of consequences: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment. Where positive and negative reinforcement increase behavior, positive and negative punishment decrease it.

Due to individual differences, we cannot know in advance whether a consequence will be reinforcing or punishing since these are not intrinsic properties of a consequence. We can only determine whether a consequence is reinforcing or punishing by measuring how it affects the behavior that preceded it. In neurofeedback, a movie that motivates the best performance might be the most reinforcing for the client, regardless of the therapist's personal preference.

Positive reinforcement increases

the frequency of a desired behavior by making a desired outcome contingent on performing the action. For example, a movie plays when a client diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) increases low-beta and decreases theta activity.

Negative reinforcement increases the frequency of a desired behavior by making the avoidance, termination, or postponement of an unwanted outcome contingent on performing the action. For example, an athlete's anxiety decreases by shifting from high beta to low beta.

Positive punishment decreases or eliminates an undesirable behavior by associating it with unwanted consequences. For example, a child's increased fidgeting dims a favorite movie and lowers the sound.

Negative punishment

decreases or eliminates an undesirable behavior by removing what is desired. For example, oppositional behavior could result in a clinician turning off a popular game.

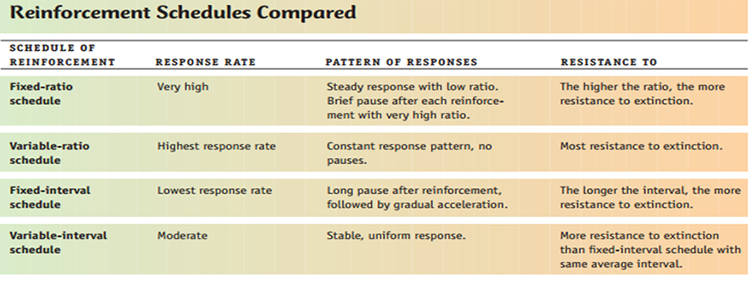

Reinforcement Criteria

Current research is exploring the optimal reinforcement criteria for neurofeedback training. Client skill acquisition is markedly affected by changing parameters like reinforcement schedule, frequency of reward, reinforcement delay, conflicting reinforcements, conflicting expectations, and alteration of the environment.While continuous reinforcement, reinforcement of every desired behavior, is helpful during the early stage of skill acquisition, it is impractical as clients attempt to transfer the skill to real-world settings. Since reinforcement outside of the clinic is intermittent, partial reinforcement schedules, where the desired behavior is only reinforced some of the time, are important as training progresses. This reduces the risk of extinction, where failure to reinforce the desired behavior reduces the frequency of that behavior.

For neurofeedback, variable reinforcement schedules, where reinforcement occurs after a variable number of responses (variable ratio) or following a variable duration of time (variable interval) produce superior response rates than their fixed counterparts.

Sherlin et al. (2011) emphasized the importance of professionals understanding targeted brain rhythms and the underlying EEG neurophysiology. For example, the sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) consists of spindles with at least a 0.25-second duration. Use of criteria like "time above threshold" or "duration of sustained reward" tailors feedback to the SMR rhythm and results in superior outcomes compared to reinforcing any shift above an SMR amplitude threshold.

Sherlin et al. (2011) advised that: "For operant conditioning, it is very important to be aware of specifically 'what behavior' is being conditioned in order to achieve learning and to improve the specificity" (p. 300).