Artifact Detection

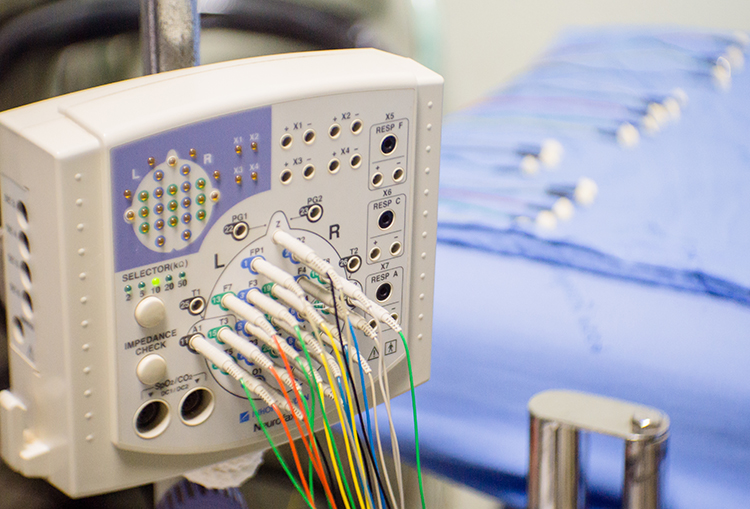

Contamination of the qEEG by physiological and exogeneous artifacts requires that clinicians take extensive precautions, examine the raw EEG record, and remove contaminated epochs through artifacting. Impedance tests and behavioral tests help ensure the fidelity of EEG recording.

Client assessment and training are only as good as your data. © Scott Adams.

We recommend the “close the barn door before the horse escapes” strategy to ensure data integrity. Prevent artifact before you record data so that you don’t have to remove it later.

|

|

International QEEG Certification Board Blueprint Coverage

This unit covers I. Recording and Editing Raw EEG and Artifact Detection (2 hours).

This unit reviews Elimination of Artifact from qEEG Recording and Recognizing and Correcting Signals of Noncerebral Origin.

Elimination of Artifact from qEEG Recording

Once you understand the mechanics and appearance of common artifacts, Peper et al. (2008) recommend that you intentionally reproduce them to recognize and prevent them.

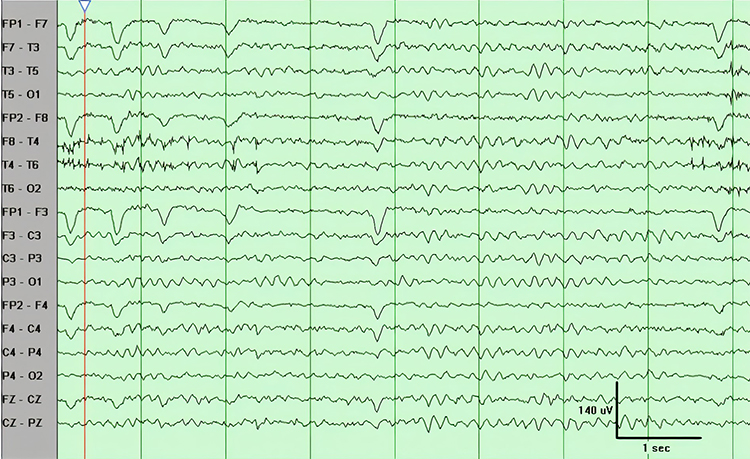

Brain map validity depends on the integrity of the raw EEG. You will need 45 seconds of reasonably clean data to construct a valid brain map from raw EEG recordings 3-10 minutes in length. However, the ideal amount of clean data is approximately 2 minutes for adequate database comparison. Realize that longer recordings risk increased drowsiness artifacts and sleep. Therefore, it is helpful to speak to the client to help them maintain alertness occasionally. Simply saying how much time is left every 1-2 minutes is usually enough to accomplish this.

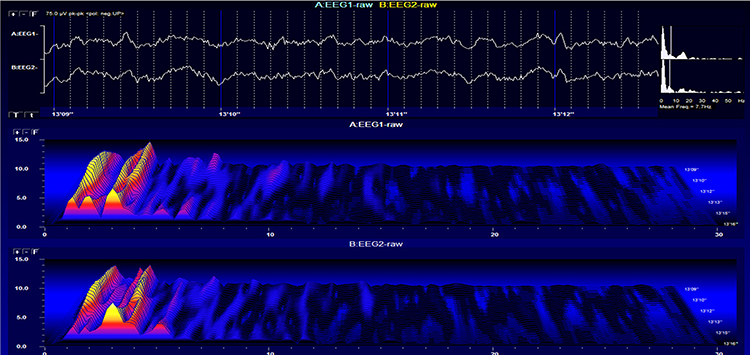

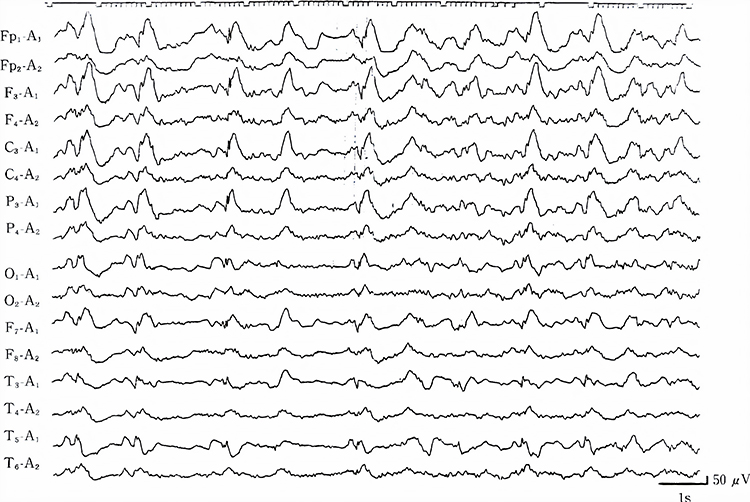

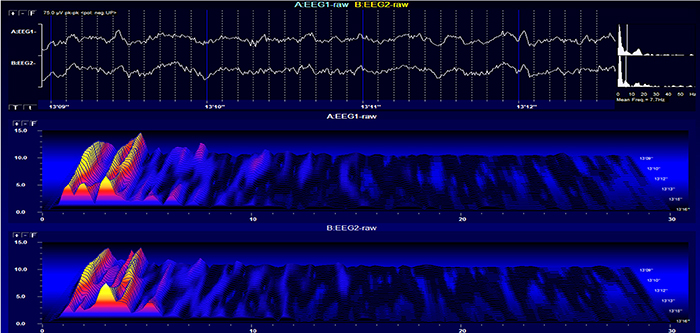

Stage 1 sleep is a subtle drowsy state that clients often do not recognize. This state change is seen as a decrease in alpha and an increase in theta amplitudes. There will be slow eye-rolling movements and decreased EMG and beta. Stage 1 sleep graphic © John S. Anderson. Note the increased theta amplitudes in the spectral displays for channels 1 and 2.

The less frequent the artifact, the shorter the required recording period. Disable low-pass and high-pass filters before editing to better visualize electro-ocular and SEMG artifacts.

Worst case, as with a hyperactive child, none of the EEG channels may contain usable data, and you will need to repeat the assessment. Where artifact only contaminates a few channels, you may base assessment on the clean channels (Demos, 2019).

Strategies to Reduce Artifact

Demos (2019) recommends several precautions to reduce artifact in raw EEG recordings:- Demonstrate how to create artifacts for your clients using screen displays while they clench their teeth, move their eyes, blink, swallow, and fidget

- Confirm the cap fits properly

- Use reclining chairs with negligible neck cushioning that can force the head downward to minimize SEMG artifact

- Limit eyelid movement with cotton balls gently touching the closed eyelids, secured by a loose sleep mask, flexible band, or tape in the eyes-closed recording. There should be no pressure against the eyes

- Ensure that impedance values or DC offset values are appropriate for your amplifier (values under 5 Kohms are expected for publishable research, but values of less than 20 Kohms are acceptable for general clinical sessions and do not require excessive skin abrasion)

- Only record qEEG data when the raw waveforms appear clean

The movie is a 19-channel BioTrace+ /NeXus-32 display of EEG processing in NeuroGuide™ © John S. Anderson.

Recognition of Spike/Wave Activity in the Raw EEG

Abnormal EEG patterns include abnormal slow activity, paroxysmal epileptogenic abnormalities, and abnormal periodic paroxysmal patterns.

Abnormal Slow Activity

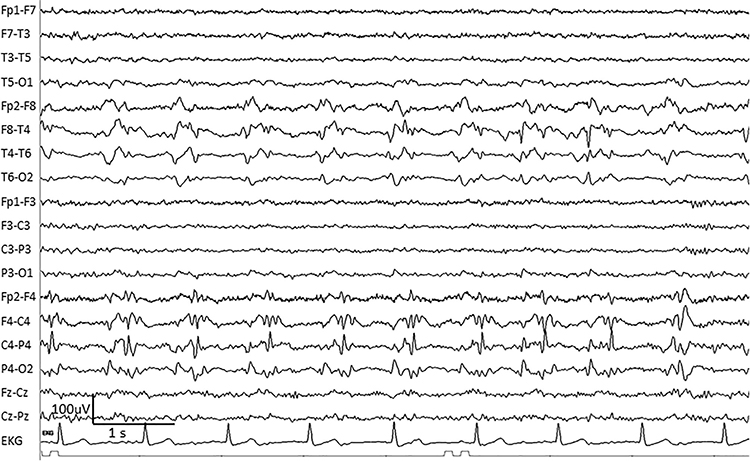

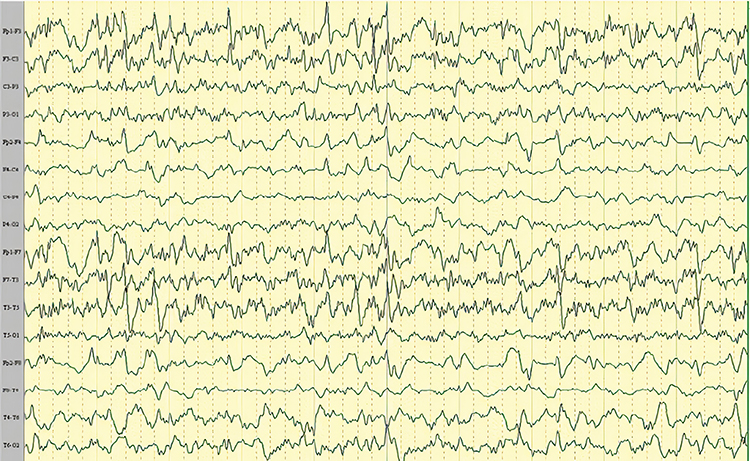

Abnormal slow activity includes generalized intermittent slow activity, focal and lateralized intermittent slow activity, and persistent slow activity.Generalized intermittent slow activity is asynchronous, under 8 Hz, and involves the majority or all of both hemispheres. These bursts typically consist of polymorphic delta (Benbadis & Rielo, 2018). Alerting and opening the eyes reduce, whereas hyperventilation challenge and relaxation increase these slow waves (Fisch, 1999). Graphic © Medscape.

Focal and lateralized intermittent slow activity is under 8 Hz and is usually confined to a single or a couple of adjacent electrodes. These bursts have an irregular appearance, are composed of several frequencies, and rarely involve an entire hemisphere (Fisch, 1999). Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

Persistent slow activity consists of theta and delta waveforms. Distribution may be anterior or widespread in encephalopathies (Richardson & Benbadis, 2019). Graphic © Medscape.

Paroxysmal Epileptogenic Abnormalities

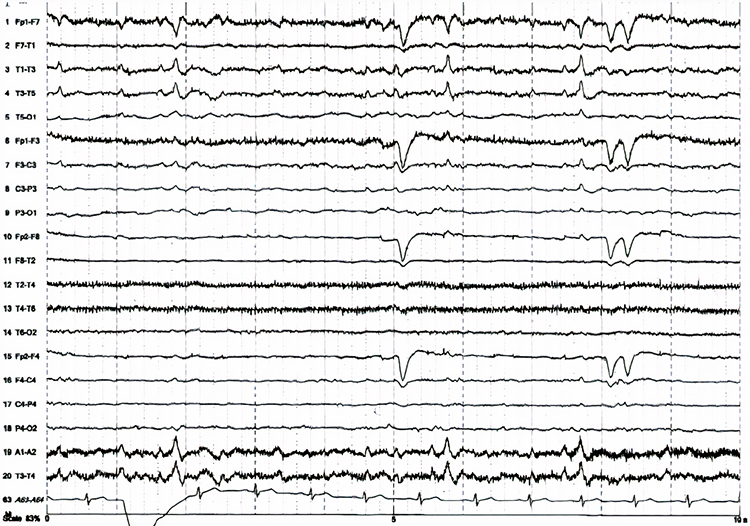

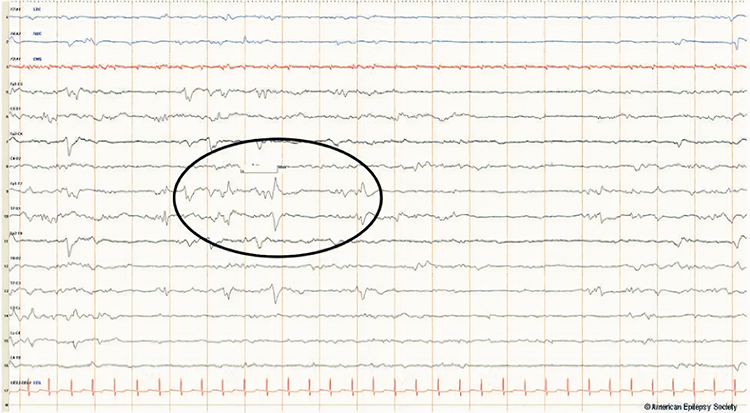

Paroxysmal epileptogenic abnormalities include interictal epileptiform discharges (focal, generalized), ictal, secondary bilateral synchrony, and epileptiform patterns of doubtful significance.Interictal epileptiform discharges typically consist of individual spikes and sharp waves and complexes that contain both waveforms that last less than 2 seconds (Fisch, 1999). Graphic courtesy of Teppei Matsubara.

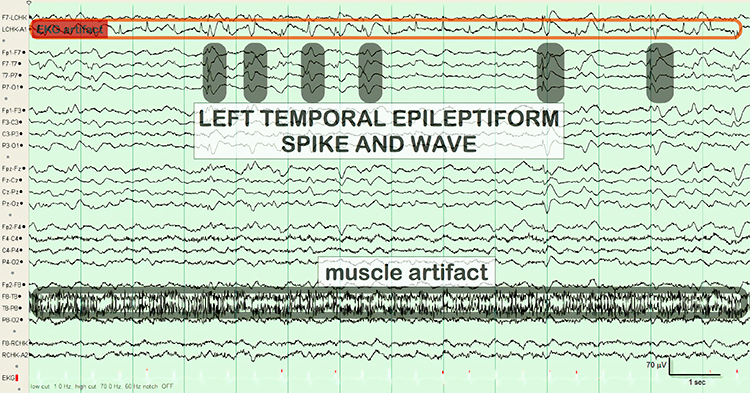

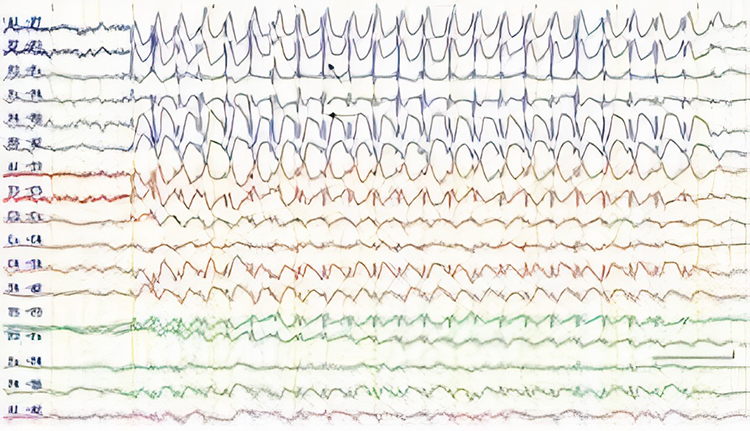

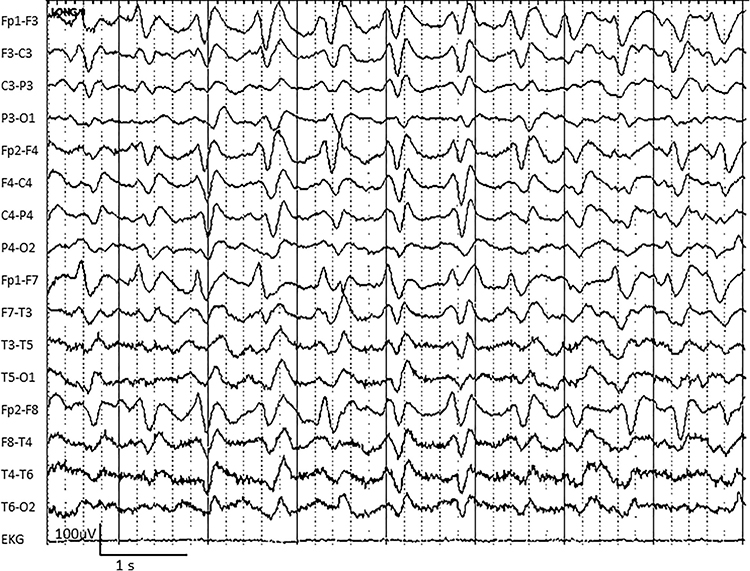

Ictal epileptiform discharges may consist of prolonged interictal activity. These may include 3-Hz spike-and-wave discharges, slow spike-and-wave discharges, sharp-and-slow-wave discharges, amplitude and frequency fluctuations in rhythms of 10 Hz or higher, and irregular multiple spike-and-wave or spike-and-wave discharges (Fisch, 1999). Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

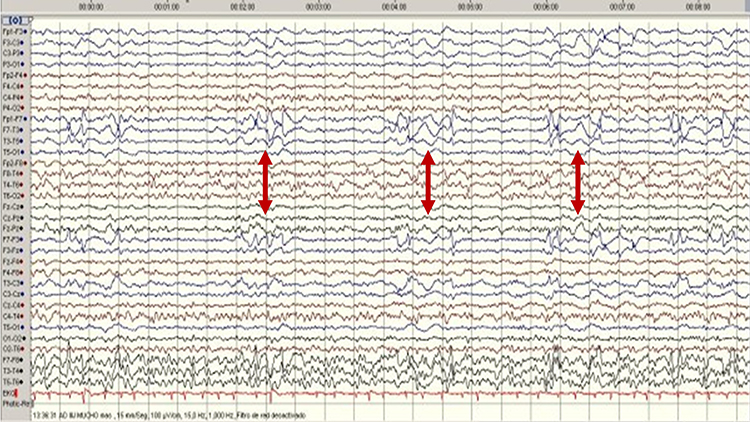

Secondary bilateral synchrony (SBS) involves spikes with a single phase reversal around the midline (Jin, 2007). Graphic © Neurology Asia.

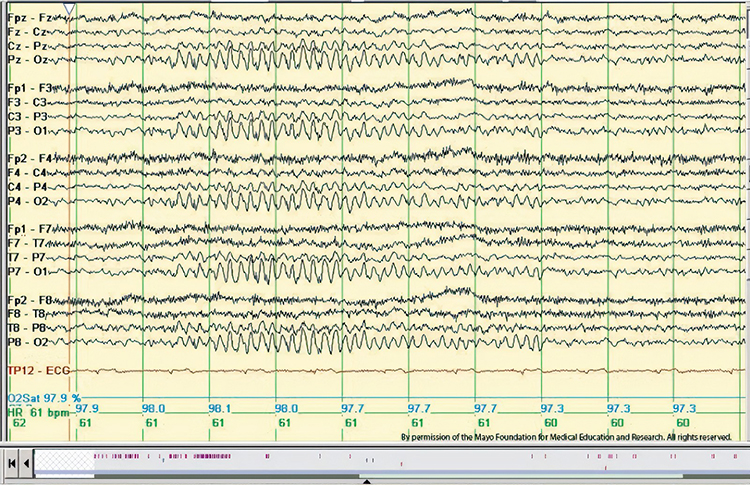

Epileptogenic patterns of doubtful significance are brief and not associated with seizures or neurological disorders. Examples are 6-Hz spike-and-slow-wave, 14- and 16-Hz positive bursts, benign epileptiform transients of sleep (BETS), rhythmical mid-temporal discharge (RMTD), small sharp spikes (SSS), and wicket spikes (Fisch, 1999). Six-Hz graphic © Mayo Foundation for Medical Education.

Abnormal Periodic Paroxysmal Patterns

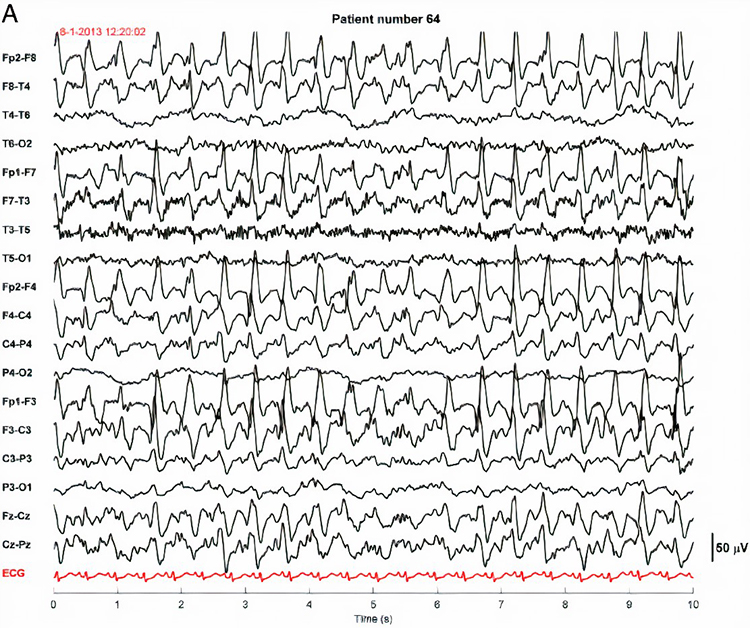

Abnormal periodic paroxysmal patterns include generalized periodic paroxysmal patterns and lateralized periodic paroxysmal patterns. Generalized periodic paroxysmal patterns involve the same areas of both hemispheres. The waveforms exhibit similar composition, amplitude, and phase in each hemisphere but may slightly vary within a hemisphere (Fisch, 1999). Graphic © Epilepsy & Behavior.

Lateralized periodic paroxysmal patterns differ from generalized periodic paroxysmal patterns in their unilateral distribution. Both patterns share the same waveform morphology (Fisch, 1999). Graphic © Internal Medicine.

Descriptive Terms

Amplitude is classified as low (less than 20 µV), typical (20-50 µV, depending on age), and high (60-200+ µV). Duration is described as very brief (less than 10 s), brief (10-60 s), intermediate duration (1-1.5 min), prolonged (5-60 min), and protracted (greater than 60 min).

Common EEG Acronyms for Rhythmic and Periodic Patterns

The common EEG acronyms reviewed in this section include LPDs, BIPDs, GPDs, GRDA, IRDA, LRDA, PLEDs, BIPLEDs, FIRDA, GPEDs, Mf, SIRPIDs, and SW.LPDs are lateralized periodic discharges. These unilateral discharges appear as sharp waves or spikes, 100-300 µV, and recur at rates up to 3 Hz (Johnson & Kaplan, 2017). Graphic © ScienceDirect.

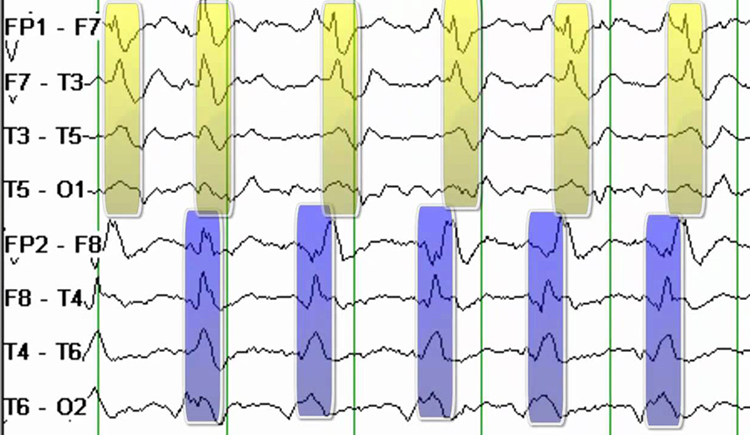

BIPDs are bilateral independent periodic discharges. These asynchronous discharges occur independently in the left and right hemispheres, appear as sharp waves or spikes, 100-300 µV, and recur at rates up to 3 Hz (Johnson & Kaplan, 2017). Graphic © ScienceDirect.

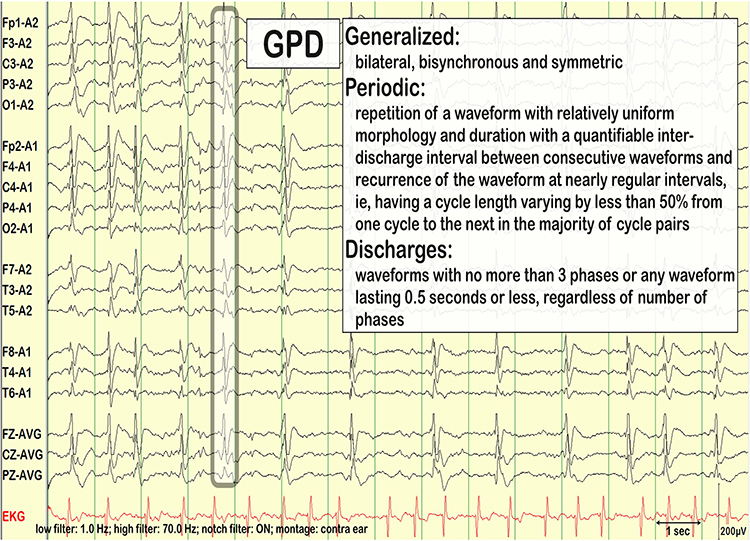

GPDs are generalized periodic discharges. These discharges synchronously occur in both hemispheres, appear as sharp waves or spikes, amplitudes exceed 100 µV, and recur at rates up to 3 Hz (Johnson & Kaplan, 2017). Graphic © ScienceDirect.

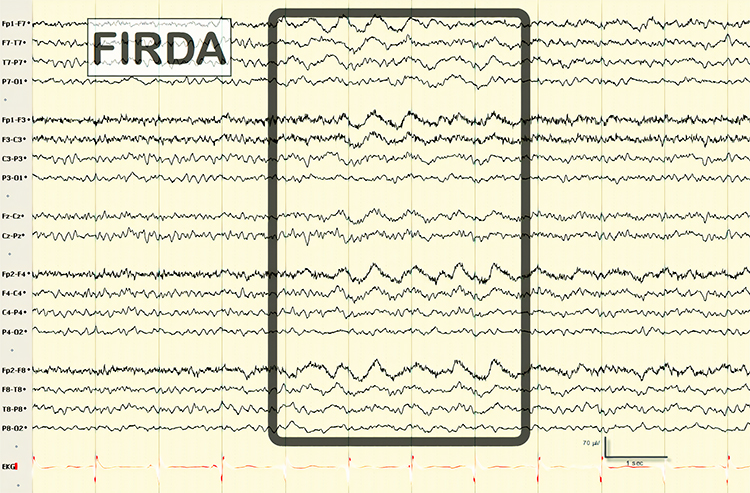

GRDA is generalized rhythmic delta activity. The term frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (FIRDA) was used before ACNS standardization in 2012. These bilateral and synchronous discharges exceed 100 µV and recur at rates up to 3 Hz (Johnson & Kaplan, 2017). Graphic © ScienceDirect.

For focal patterns, describe the location with R (right). L (left), A (anterior), and P (posterior).

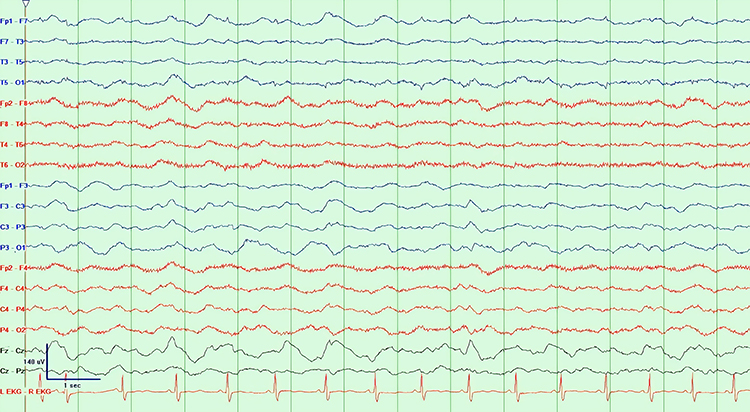

IRDA is intermittent rhythmic delta activity. These bilateral synchronous discharges recur between 2-2.5 Hz and appear in brief bursts. Graphic © Richardson and Benabis (2019).

LRDA is lateralized rhythmic delta activity. These unilateral discharges recur at rates up to 3 Hz. LRDA runs typically last less than 1 minute and is shorter than LPDs (Johnson & Kaplan, 2017). Graphic © ScienceDirect.

PLEDS are periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges. They are lateralized or focal and exhibit regular periodic, negative spike-and-sharp wave patterns with a 20-1000 ms duration and 50-300 µV amplitude.

BIPLEDS are bilateral independent periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges. They are asynchronous discharges that occur independently in both hemispheres, appear as sharp waves or spikes, 40-100 µV in bipolar montages, and recur at rates from 0.5-1.5 Hz.

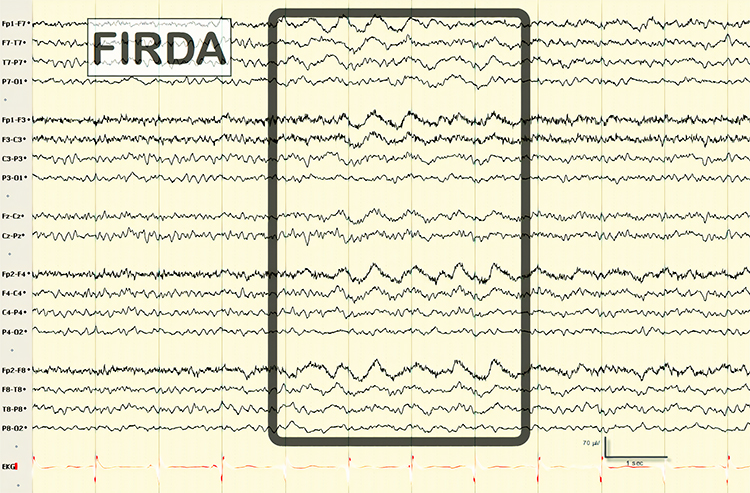

FIRDA is frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity. Structural brain lesions and encephalopathy are independently associated with the occurrence of FIRDA. Asymmetric FIRDA may be associated with an underlying brain lesion.

FIRDA appears more common than previously reported and is associated with various lesions and encephalopathic conditions. However, FIRDA may also occur in otherwise healthy subjects during hyperventilation. FIRDA occurrence should prompt investigations for toxic-metabolic disturbances and structural lesions (particularly if asymmetric) but does not suggest an epileptic risk. Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

GPEDs (or GPDs) are generalized periodic epileptiform discharges. Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

Mf is multifocal. Graphic © Tai-Tong Wong.

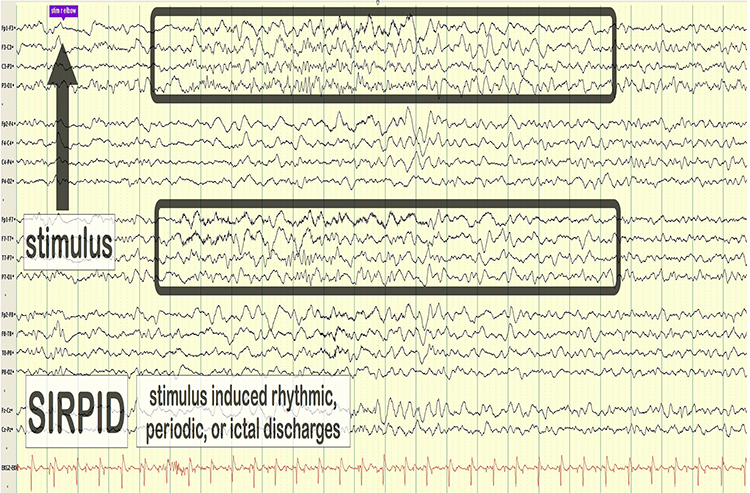

SIRPIDs are stimulus-induced rhythmic, periodic, or ictal discharges. Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

SW is spike-wave or sharp-wave.

Recognizing and Correcting Signals of Noncerebral Origin

EEG artifacts, consisting of noncerebral electrical activity, can be divided into physiological and exogenous artifacts. Physiological artifacts include electromyographic, electro-ocular (eye blink and eye movement), cardiac (pulse), sweat (skin impedance), drowsiness, and evoked potential. Exogenous artifacts include movement, 60 Hz and field effect, and electrode (impedance, bridging, and electrode pop) artifacts.

Electromyographic (EMG) Artifact

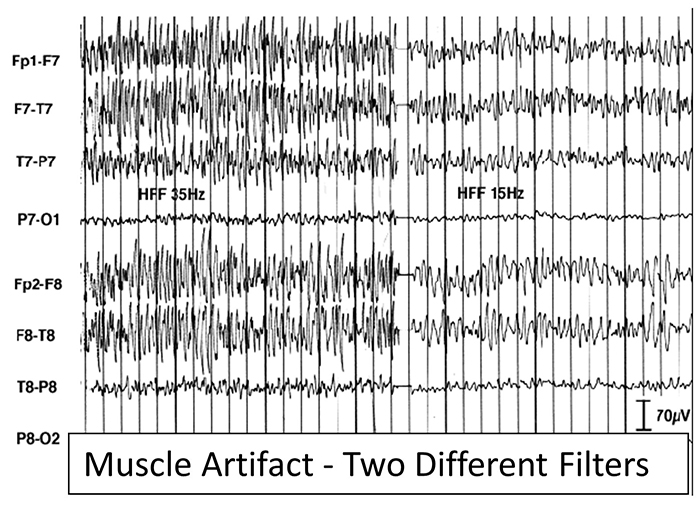

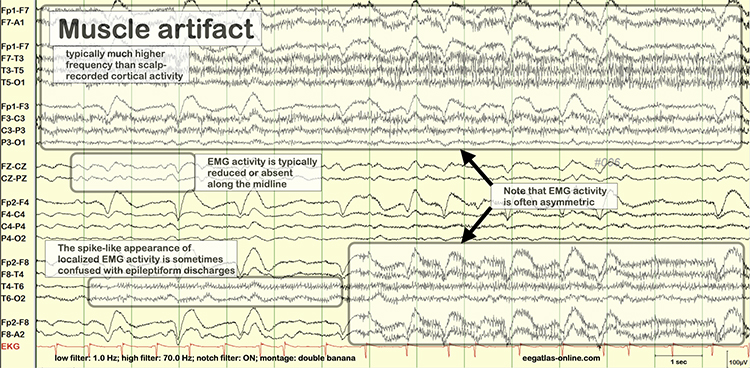

EMG artifact is interference in EEG recording by volume-conducted signals from skeletal muscles. This artifact contains high-frequency activity that resembles a "buzz" of fast activity during a contraction. EMG is seen as fast beta activity in the qEEG. While some frequencies are between 10-70 Hz, most are 70 Hz or higher.The graphic shows how high-frequency filter (HFF) selection can affect contamination by this artifact. A high-frequency filter (low-pass filter) attenuates frequencies above a cutoff frequency. In the examples below, the cutoffs are 35 Hz and 15 Hz.

All the channels on the left side of the tracing show SEMG artifact admitted by a 35-Hz high-frequency filter. The right tracing is free from SEMG artifact since its 15-Hz high-frequency filter attenuates the higher frequencies that contain this artifact.

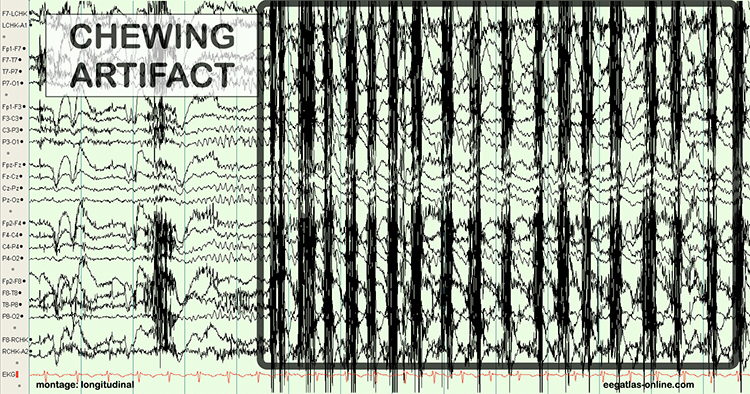

The next graphic shows how gum chewing can generate SEMG artifact by contracting the muscles of mastication. Graphics © eegatlas-online.com.

The frequency spectrum for SEMG artifact ranges from 2-1,000 Hz. While strong muscular contraction can contaminate all frequency bands, including 10 Hz, the beta rhythm (at 70 Hz or higher) is most affected by this artifact. EMG artifact may create the appearance of greater beta activity than is present. Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

Below is a BioGraph ® Infiniti EMG artifact display. Note how the amplitude of the EEG spectrum increases with each contraction.

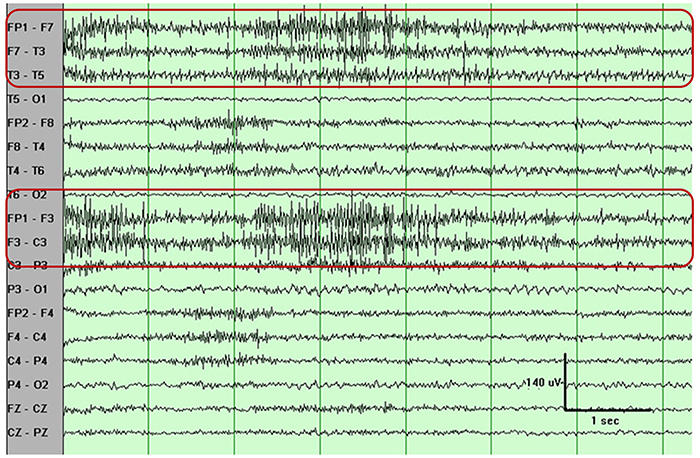

Thompson and Thompson (2016) observed that EMG artifact is readily detected because it affects one or two channels, particularly at T3 and T4 at the periphery, and less often at O1, O2, Fp1, and Fp2.

You can identify EMG artifact by visually inspecting the raw signal. The next graphic shows SEMG artifact using a 70-Hz high-frequency filter.

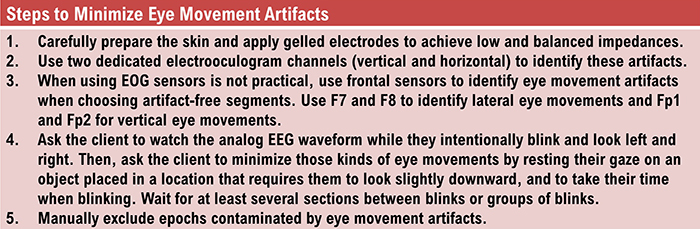

Electro-Ocular Artifact

Electro-ocular artifact contaminates EEG recordings with potentials generated by eye blinks, eye flutter, and other eye movements. For example, anxious patient eyelid flutter may cause deflections at Fp1 and Fp2 (Klass, 2008).This artifact is due to the movement of the eye’s electrical field when the eye rotates and the contraction of the extraocular muscles. The eye creates a dipole that is electropositive at the front and electronegative at the back. Bell’s Phenomenon refers to the upward rotation of the eye when it closes and causes an artifact seen as an apparent increase in EEG.

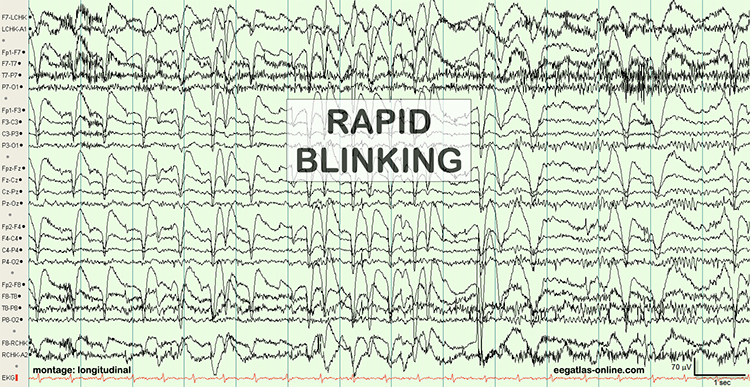

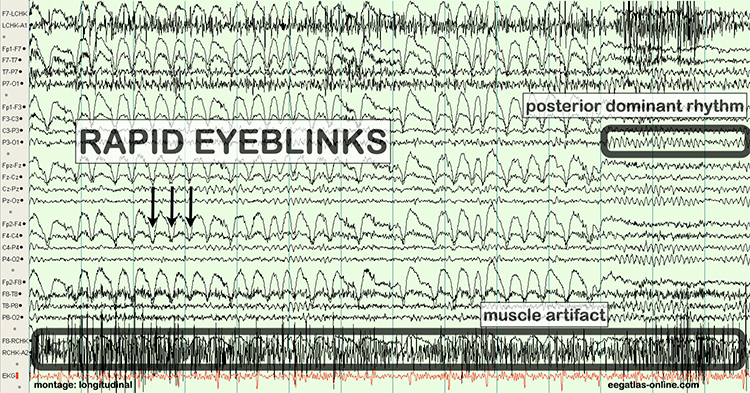

The next two graphics show eye movement artifacts due to rapid blinking. Graphics © eegatlas-online.com.

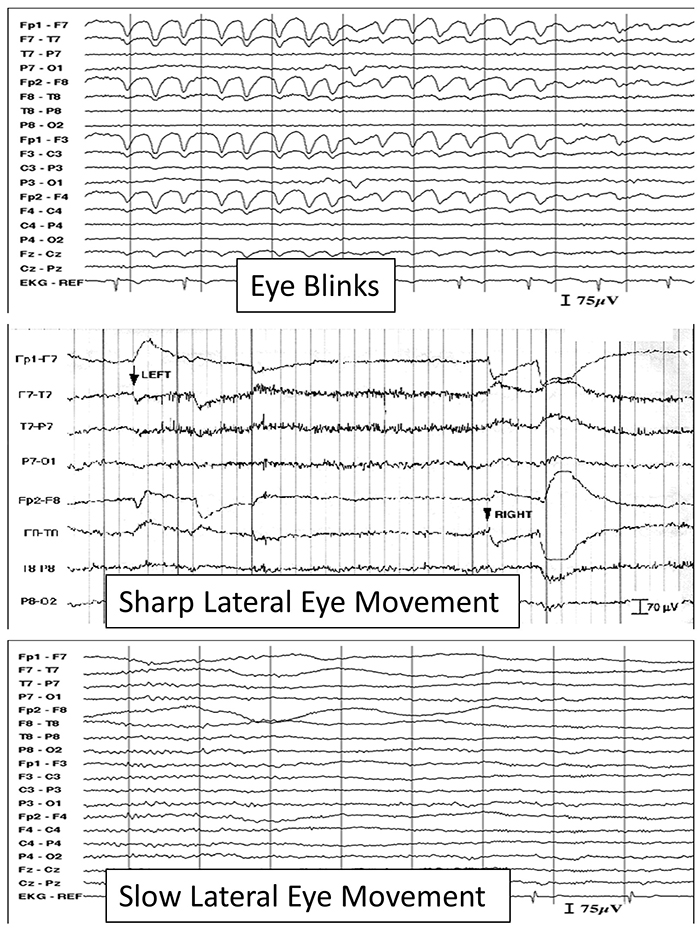

The next graphic shows eye blinks, sharp lateral eye movement, and slow lateral eye movement.

Below is a BioGraph ® Infiniti EEG display of eye movement artifact.

Below is a NeXus display of eye blink and EMG © John S. Anderson.

An upward eye movement will create a positive deflection at Fp1, while a downward eye movement may create a negative deflection. In a longitudinal sequential montage, the artifact is typically seen at frontal sites (Fp1- F3 and Fp2-F4). A left movement may produce a positive deflection at F7 and a negative deflection at F8 (Thompson & Thompson, 2015).

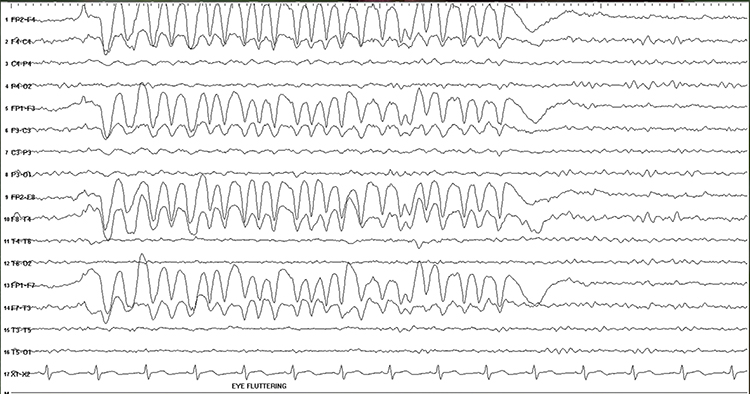

Rapid eye flutter may resemble seizure activity. Graphic © John S. Anderson.

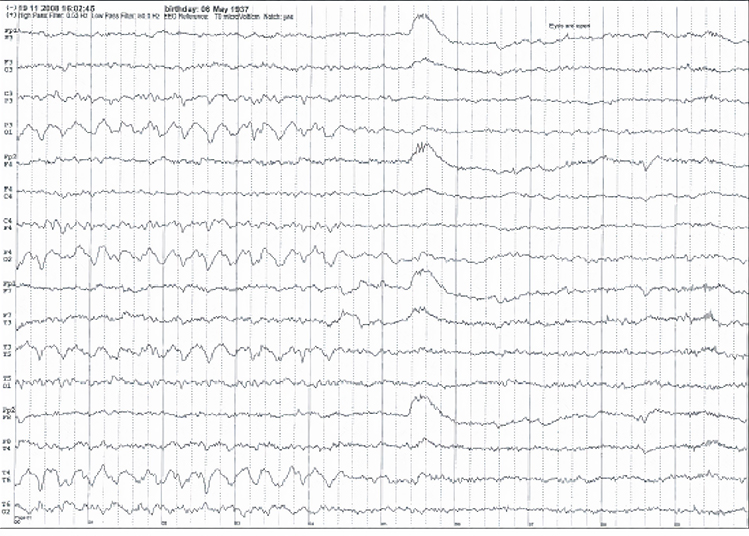

Cardiac and Pulse Artifacts

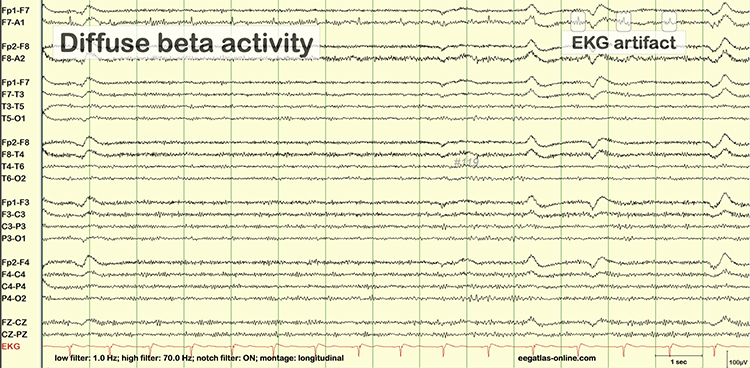

Cardiac artifact occurs when the ECG signal appears in the EEG. This artifact may be produced when electrode impedance is imbalanced or too high or when an ear electrode contacts the neck. The frequency range for ECG artifact is 0.05-80 Hz, and it contaminates the delta through beta bands. Since multiple electrodes detect this artifact, it can create the appearance of greater coherence than is present. Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

You can detect cardiac artifacts by inspecting chart recorder, data acquisition, or oscilloscope displays of the raw EEG waveform. Cardiac artifact appears as a wave that repeats about once per second (Thompson & Thompson, 2016). Below is a BioGraph ® Infiniti ECG artifact display.

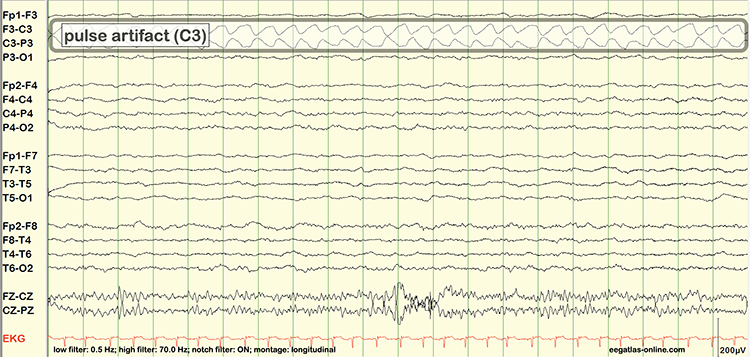

Pulse artifacts are due to the mechanical movement of an electrode in relation to the skin surface due to the pressure wave of each heartbeat. Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

Sweat (Impedance) Artifact

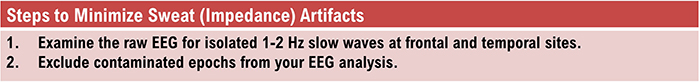

Sweat artifact results from sweat on the skin changing the conductive properties under and near the electrode sites (i.e., bridging artifact). Sweating reduces electrode contact with the scalp and generates large-scale up and down EEG line movements in several frontal channels. This artifact is often elicited by abrupt, unexpected stimuli and usually appears as isolated 1-2 Hz slow waves of 1-2-s duration at frontal and temporal sites (Thompson & Thompson, 2015). Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

Bridging Artifact

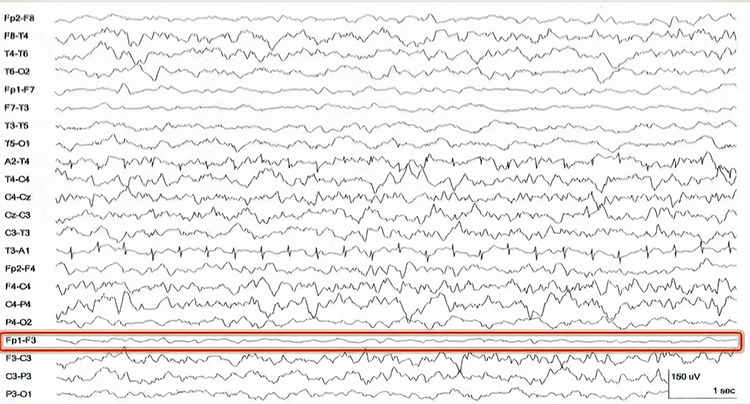

A short circuit produces bridging artifact between adjacent electrodes due to excessive application of electrode paste or a client who is sweating excessively or who arrives with a wet scalp. Bridging artifacts can cause adjacent electrodes to create a short circuit that produces identical referential EEG recordings or a flat line with a bipolar montage. The Fp1-F3 channel's reduced amplitude and frequency illustrate a bridging artifact.

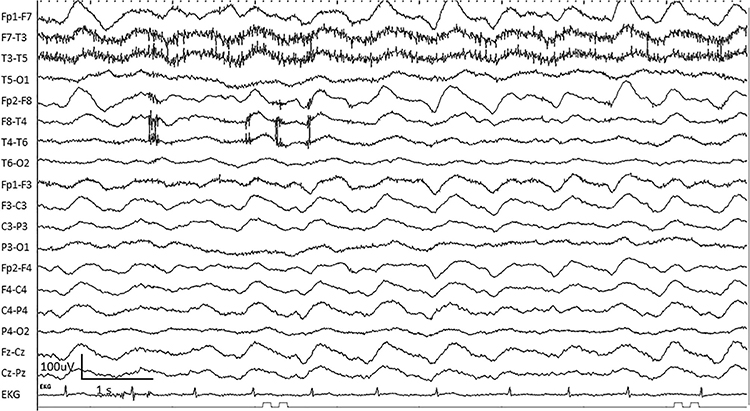

Drowsiness Artifact

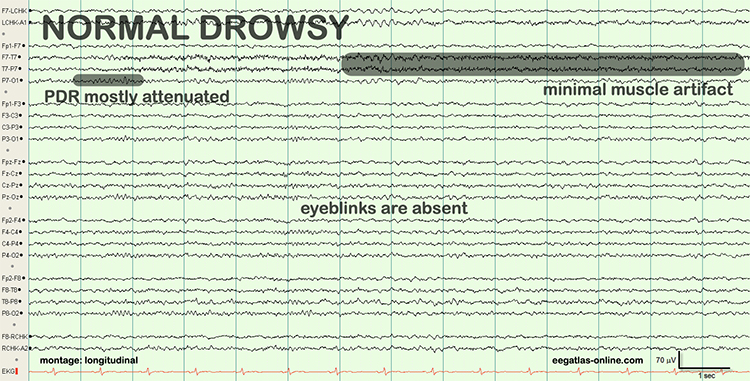

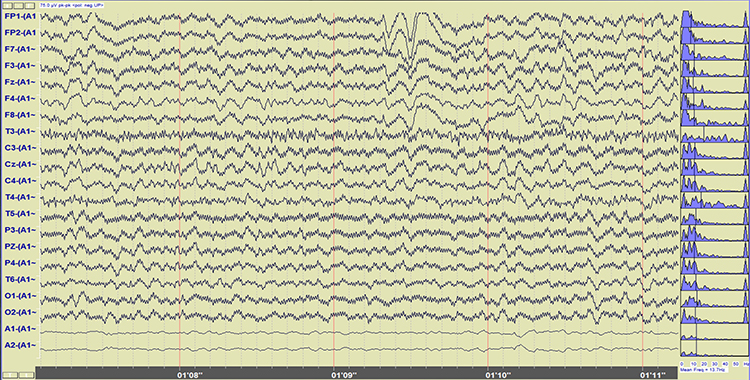

Drowsiness artifact is the appearance of stage 1 or stage 2 sleep in the EEG. Stage 1 and stage 2 of sleep are most likely during eyes-closed recording. Sleep may occur during eye-closed awake recording. Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

Stage 1 sleep is a subtle drowsy state which clients often do not recognize. Alpha amplitude (especially occipital) may decrease, and theta (especially frontal) may increase. Reductions in EMG and beta amplitude will accompany slow eye-rolling movements. Sleepiness may be accompanied by spike-like transients (vertex or V-waves). The graphic below © John S. Anderson shows increased theta during stage 1 sleep.

When you detect drowsiness artifact during a training session, suspend recording and instruct your clients to move their hands and legs to increase wakefulness. To avoid this artifact, ask them to retire early and sleep for 9 hours if possible (Thompson & Thompson, 2003).

Evoked Potential

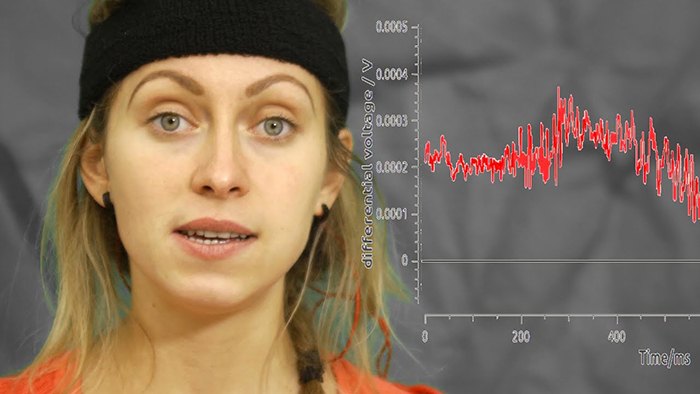

Evoked potential artifact (also called event-related potential artifact) consists of somatosensory, auditory, and visual signal processing-related transients that may contaminate multiple channels of an EEG record. While evoked potentials increase recording variability and reduce its reliability, they minimally affect averaged data (Thompson & Thompson, 2015).The graphic below is courtesy of BPM biosignals' YouTube video EEG: Visually evoked potentials (VEP).

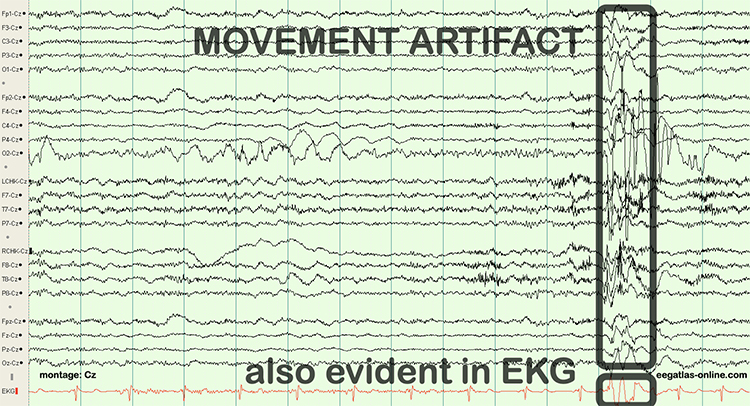

Movement Artifact

Movement artifact is caused by client movement or the movement of electrode wires by other individuals. Most of these artifacts are produced by brief changes in electrode-skin surface connection. Cable movement is called cable sway. The graphic below that illustrates cable sway is courtesy of iMotions.com.

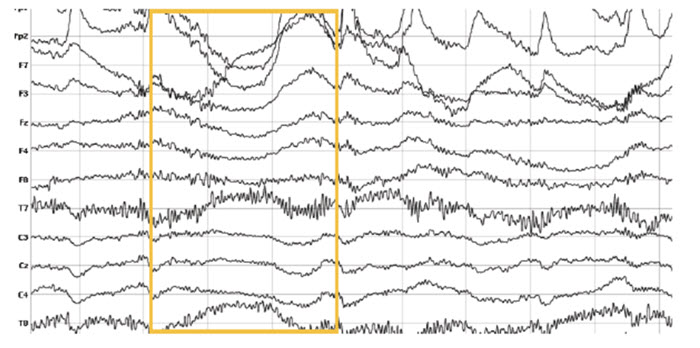

Movement artifacts can produce high-frequency and high-amplitude voltages identical to EEG and EMG signals. While the delta rhythm is most affected by this artifact, it may also contaminate the theta band (Thompson & Thompson, 2016). Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

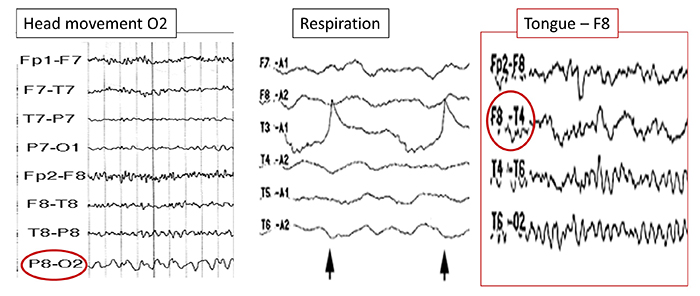

The graphic below shows movement artifacts due to head movement (left), respiration (center), and tongue movement (right).

Below is a BioGraph ® Infiniti cable movement artifact display. Note the two voltage spikes at the beginning of the recording.

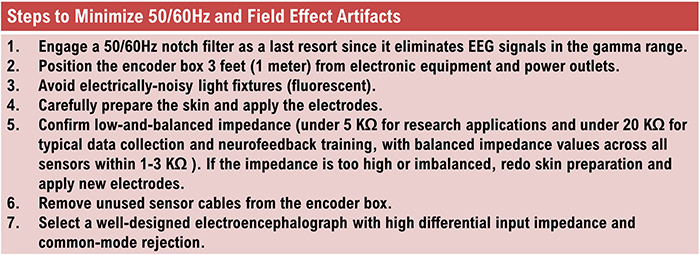

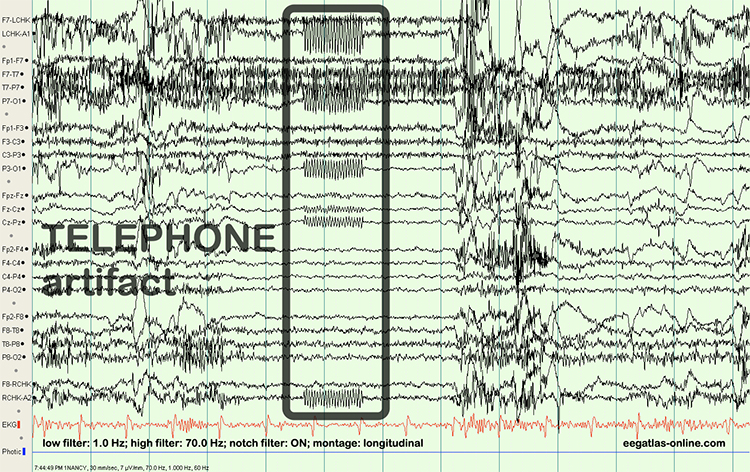

50/60 Hz and Field Artifacts

Both 50/60 Hz and field artifacts are external artifacts transmitted by nearby electrical sources. While 60-Hz artifact is a risk in North America where AC voltage is transmitted at 60 Hz, 50-Hz artifact is a problem in other locations that generate power at 50 Hz. Their fundamental frequency is 50 or 60 Hz with harmonics at 100/120 Hz, 150/180 Hz, and 200/240 Hz. Imbalanced electrode impedances increase an EEG amplifier's vulnerability to these artifacts. The 60-Hz artifact graphic below © John S. Anderson.

A BioGraph ® Infiniti display of 60-Hz artifact is shown below in red. Note the cyclical voltage fluctuations and 60-Hz peak in the power spectral display.

Radiofrequency Artifact

Radiofrequency (RF) artifact radiates outward like a cone from the front of televisions and computer monitors. Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

Artifacts.jpg)

Electrode Artifacts

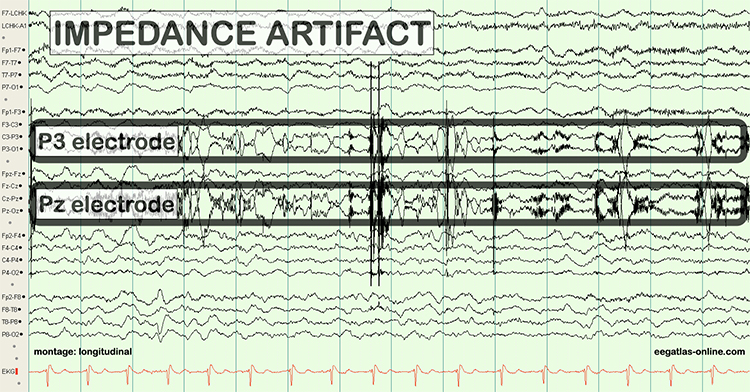

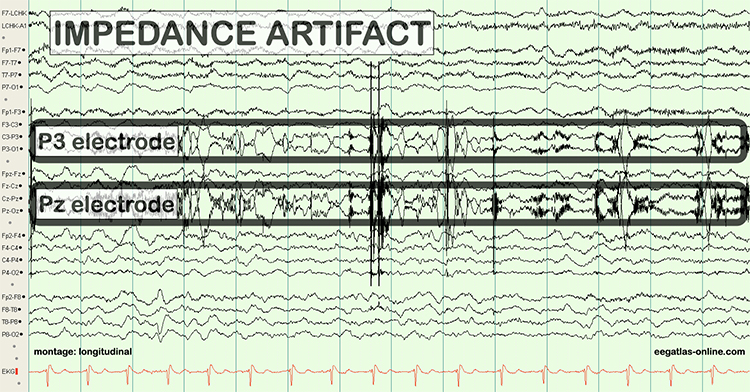

There are several sources of electrode artifacts. Even with proper care, electrode surfaces can become corroded and the leads and connectors damaged. Using sensors with mismatched electrode metals can cause polarization of amplifier input stages.Impedance Artifact

Unless skin-electrode impedance is low (under 5 KΩ for research and 20 KΩ for training) and balanced (under 1-3 KΩ ), diverse artifacts like 50/60 Hz and movement can contaminate the EEG signal, as seen in the P3 and Pz electrodes. Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

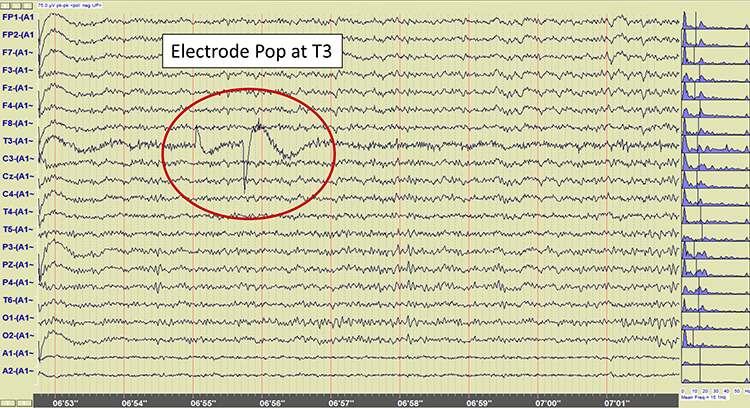

Electrode Pop Artifact

Even when the impedance is low and balanced, mechanical disturbance can produce a unique artifact. Electrode pop artifact has a sudden large deflection in at least one channel when an electrode abruptly detaches from the scalp. This may also happen when there is a bubble or other defect in the gel or paste, and a charge builds up and subsequently "jumps" across the gap, resulting in a large electrical discharge. Graphic © John S. Anderson.

Glossary

50/60 Hz: external artifacts transmitted by nearby electrical sources.

abnormal periodic paroxysmal patterns: generalized periodic paroxysmal patterns and lateralized periodic paroxysmal patterns.

abnormal slow activity: generalized intermittent slow activity, focal and lateralized intermittent slow activity, and persistent slow activity.

active electrode: an electrode placed over a site that is a known EEG generator like Cz.

artifact: false signals like 50/60Hz noise produced by line current.

benign epileptiform transients of sleep (BETS): sharp waves are seen alone or as a low-amplitude spike and a smaller after-going slow wave. BETS can be monophasic or diphasic and occur during light sleep. There is no disturbance of background activity, and it does not progress.

benign small sharp spikes (BSSS): sharp waves are seen alone or as a low-amplitude spike and a smaller after-going slow wave. BETS can be monophasic or diphasic and occur during light sleep. There is no disturbance of background activity, and it does not progress.

bilateral independent periodic discharges (BIPDs): asynchronous discharges that occur independently in the left and right hemispheres, appear as sharp waves or spikes, 100-300 µV, and recur at rates up to 3 Hz.

bilateral independent periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges (BIPLEDs): asynchronous discharges that occur independently in both hemispheres, appear as sharp waves or spikes, 40-100 µV in bipolar montages, and recur at rates from 0.5-1.5 Hz.

bridging artifact: a short circuit between adjacent electrodes due to excessive application of electrode paste or a client who is sweating excessively or who arrives with a wet scalp.

brief duration: 10-60 s.

cardiac artifact: the contamination of the EEG by the ECG signal.

drowsiness artifact: in adults, 1-Hz (or slower) waveforms can be detected with greatest amplitude and reverse polarity at F7 and F8 may progress to 1-2 Hz slowing of the alpha rhythm.

EEG artifacts: noncerebral electrical activity in an EEG recording can be divided into physiological and exogenous artifacts.

electro-ocular artifact: contamination of EEG recordings by potentials generated by eye blinks, eye flutter, and eye movements.

electrode: a specialized conductor that converts biological signals like the EEG into currents of electrons.

electrode pop artifact: sudden large deflections in at least one channel when an electrode abruptly detaches from the scalp.

EMG artifact: interference in EEG recording by volume-conducted signals from skeletal muscles.

epileptogenic patterns of doubtful significance: brief EEG patterns not associated with seizures or neurological disorders. Examples are 6-Hz spike-and-slow-wave, 14- and 16-Hz positive bursts, benign epileptiform transients of sleep (BETS), rhythmical mid-temporal discharge (RMTD), small sharp spikes (SSS), and wicket spikes.

evoked potential artifact (event-related potential artifact): somatosensory, auditory, and visual signal processing-related transients that may contaminate multiple channels of an EEG record.

exogenous artifacts: noncerebral electrical activity generated by movement, 50/60 Hz and field effect, bridging, and electrode (electrode “pop" and impedance) artifacts.

field artifacts: external artifacts transmitted by nearby electrical sources.

focal and lateralized intermittent slow activity: EEG activity under 8 Hz and usually confined to a single or a couple of adjacent electrodes. These bursts have an irregular appearance, are composed of several frequencies, and rarely involve an entire hemisphere.

Fp (frontopolar or prefrontal): sites in the International 10-20 system that detect prefrontal cortical EEG activity.

frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (FIRDA): bilateral and synchronous discharges that exceed 100 µV and recur at rates up to 3 Hz.

frequency (Hz): the number of complete cycles that an AC signal completes in a second, usually expressed in hertz.

generalized intermittent slow activity: asynchronous EEG activity under 8 Hz that involves the majority or all of both hemispheres. These bursts typically consist of polymorphic delta.

generalized periodic discharges (GPDs): asynchronous EEG activity under 8 Hz that involves the majority or all of both hemispheres. These bursts typically consist of polymorphic delta.

generalized periodic epileptiform discharges (GPEDs or GPDs): bilateral and synchronous discharges that exceed 100 µV and recur at rates up to 3 Hz.

generalized periodic paroxysmal patterns: epileptiform discharges in the same areas of both hemispheres. The waveforms exhibit similar composition, amplitude, and phase in each hemisphere but may slightly vary within a hemisphere.

generalized rhythmic delta activity (GRDA): generalized rhythmic delta activity. The term frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (FIRDA) was used before ACNS standardization in 2012. These bilateral and synchronous discharges exceed 100 µV and recur at rates up to 3 Hz.

high amplitude: 60-200+ µV.

ictal epileptiform discharges: individual spikes and sharp waves, and complexes that contain both waveforms that last less than 2 s.

interictal epileptiform discharges: high-amplitude spike-and-wave or polyspike-and-wave complexes that repeat at a frequency of 3 Hz.

intermediate duration: 1-1.5 minutes.

intermittent rhythmic delta activity (IRDA): bilateral synchronous discharges recur between 2-2.5 Hz and appear in brief bursts.

lateralized periodic discharges (LPDs): lateralized periodic discharges. These unilateral discharges appear as sharp waves or spikes, 100-300 µV, and recur at rates up to 3 Hz.

lateralized periodic paroxysmal patterns: epileptiform discharges that differ from generalized periodic paroxysmal patterns in their unilateral distribution. Both patterns share the same waveform morphology.

lateralized rhythmic delta activity (LRDA): unilateral discharges recur at rates up to 3 Hz. LRDA runs typically last less than 1 minute and is shorter than LPDs.

low amplitude: less than 20 µV.

mastoid bone: the bony prominence behind the ear.

movement artifact: voltages caused by client movement or the movement of electrode wires by other individuals.

multifocal (Mf): an EEG abnormality detected at several scalp locations.

nasion: the depression at the bridge of the nose.

notch filter: a filter that suppresses a narrow band of frequencies, such as those produce by line current at 50/60Hz.

paroxysmal epileptogenic abnormalities: interictal epileptiform discharges (focal, generalized), ictal, secondary bilateral synchrony, and epileptiform patterns of doubtful significance.

periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges (PLEDs): lateralized or focal and exhibit regular periodic, negative spike-and-sharp wave patterns with a 20-1000 ms duration and 50-300 µV amplitude.

physiological artifacts: noncerebral electrical activity that includes electromyographic, electro-ocular (eye blink and eye movement), cardiac (pulse), sweat (skin impedance), drowsiness, and evoked potential.

polarization: chemical reactions produce separate regions of positive and negative charge where an electrode and electrolyte make contact, reducing ion exchange.

prolonged duration: 5-60 minutes.

protracted duration: greater than 60 minutes.

pulse artifacts: noncerebral voltages due to mechanical movement of an electrode in relation to the skin surface due to the pressure wave of each heartbeat.

rhythmic temporal theta of drowsiness (RMTD): bitemporal left is greater than right in this longitudinal bipolar montage. Noted are notched rhythmic waveforms localized to the temporal regions, some of which are sharply contoured.

secondary bilateral synchrony (SBS): spikes with a single phase reversal around the midline.

sharp-wave (SW): transient with pointed peak and 70 to 200 ms duration.

spike-wave (SW): transient with pointed peak and 20 to under 70 ms duration.

SREDA (or SCREDA): sub-clinical rhythmic electrographic discharges in adults.

stimulus induced rhythmic, periodic, or ictal discharges (SIRPIDs): EEG discharges reliably produced by alerting stimuli.

sweat artifact: changes in the EEG signal when sweat on the skin changes the conductive properties under and near the electrode sites (i.e., bridging artifact).

transient: isolated waveforms or complexes that can be distinguished from background activity.

typical amplitude: 20-50 µV, depending on age.

very brief duration: less than 10 s.

wicket waves: EEG activity with arciform appearance, no after-going slow-wave, and no background disruption or disturbance.

TEST YOURSELF ON CLASSMARKER

Click on the ClassMarker logo below to take a 10-question exam over this entire unit.

Visit the BioSource Software Website

BioSource Software offers Physiological Psychology, which teaches the neuroscience underlying neurofeedback, and qEEG100, which provides extensive multiple-choice testing over the International QEEG Board's Blueprint and Reading List.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this module, explain why low-and-balanced skin-electrode impedances are important in neurofeedback training. Describe the precautions you take to achieve acceptable impedance values. How do you measure impedance with your neurofeedback system?

References

Andreassi, J. L. (2000). Psychophysiology: Human behavior and physiological response. Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, Inc.

Benbadis, S. R., & Rielo, D. A. (2018). Encephalopathic EEG patterns. Medscape. Retrieved from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1140530-overview.

Breedlove, S. M., & Watson, N. V. (2020). Behavioral neuroscience (9th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Tassinary, L. G. (Eds.). (1990). Principles of psychophysiology. Cambridge University Press.

Collura, T. F. (2014). Technical foundations of neurofeedback. Taylor & Francis.

Demos, J. N. (2019). Getting started with neurofeedback (2nd ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Ferree, T. C., Luu, P., Russell, G. S., & Tucker, D. M. (2001). Scalp electrode impedance, infection risk, and EEG data quality. Clinical Neurophysiology, 112(3), 536–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00533-2

Fisch, B. J. (1999). Fisch and Spehlmann's EEG primer (3rd ed.). Elsevier.

Floyd, T. L. (1987). Electronics fundamentals: Circuits, devices, and applications. Columbus: Merrill Publishing Company.

Halford, J. J., Sabau, D., Drislane, F. W., Tsuchida, T. N., & Sinha, S. R. (2016). American Clinical Society Guideline 4: Recording clinical EEG on digital media. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, 33(4), 317-319. https://doi.org/10.1080/21646821.2016.1245563

Hugdahl, K. (1995). Psychophysiology: The mind-body perspective. Harvard University Press.

Hughes, J. R. (1994). EEG in clinical practice (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann.

Jin, L. (2007). A reappraisal of secondary bilateral synchrony. Neurology Asia, 12, 29-35.

Johnson, E. L., & Kaplan, P. W. (2017). Population of the ictal-interictal zone: The significance of periodic and rhythmic activity. Clin Neurophysiol Pract, 2, 107-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnp.2017.05.001

Kappenman, E. S., & Luck, S. J. (2010). The effects of electrode impedance on data quality and statistical significance in ERP recordings. Psychophysiology, 47(5), 888-904. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01009.x.

Klass, D. W. (2008). The continuing challenge of artifacts in the EEG. EEG artifacts. American Society of Electroneurodiagnostic Technologists, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1080/00029238.1995.11080524

Lau, T. M., Gwin, J. T., & Ferris, D. P. (2012). How many electrodes are really needed for EEG-based mobile brain imaging? Journal of Behavioral and Brain Science, 2(3), 387-393. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbbs.2012.23044

Libenson, M. H. (2010). Practical approach to electroencephalography. Saunders Elsevier.

Lin, F., Witzel, T., Hamalainen, M. S., Dale, A. M., Belliveau, J. W., & Stufflebeam, S. M. (2004). Spectral spatiotemporal imaging of cortical oscillations and interactions in the human brain. NeuroImage, 2(3), 582-595. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.neuroimage.2004.04.027

Montgomery, D. (2004). Introduction to biofeedback. Module 3: Psychophysiological recording. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Peek, C. J. (2016). A primer of traditional biofeedback instrumentation. In M. S. Schwartz, & F. Andrasik (Eds.). (2016). Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Peper, E., Gibney, K. H., Tylova, H., Harvey, R., & Combatalade, D. (2008). Biofeedback mastery: An experiential teaching and self-training manual. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Richardson, C. A., & Benbadis, S. R. (2019). Generalized EEG waveform abnormalities. Medscape. Retrieved from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1140075-overview.

Picton, T. W., & Hillyard, S. A. (1972). Cephalic skin potentials in electroencephalography. Encephalogr Clin Neurophysiol, 33, 419-424. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4694(72)90122-8

Stern, R. M., Ray, W. J., & Quigley, K. S. (2001). Psychophysiological recording (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Thompson, M., & Thompson, L. (2015). The biofeedback book: An introduction to basic concepts in applied psychophysiology (2nd ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.