Alpha-Theta Training

The EEG biofeedback (neurofeedback) approach known as alpha-theta (A-T) training is historically one of the first to be developed and is also one of the most widely used. This section will describe the evolution from early alpha training efforts to the current refinements and give an overview of the research and application of this approach. A demonstration of an A-T training session and various graphics will help readers grasp the concepts and outcomes of this type of training.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit covers VIII. Treatment Implementation - D. Introduction to Alpha-Theta Training.

This unit covers Underlying Theory, Cross-Frequency Synchronization, Local Field Potential, Global and Local Synchronization, History and Development, Benefits of A-T Training, Comparison of Interventions, A-T Training Protocols, Expected Results, Applications, Cautions, Self-Medication, Substance/Behavioral Use Disorders, and Final Thoughts.

Please click on the podcast icon below to hear a full-length lecture.

Underlying Theory -- Timing is Everything!

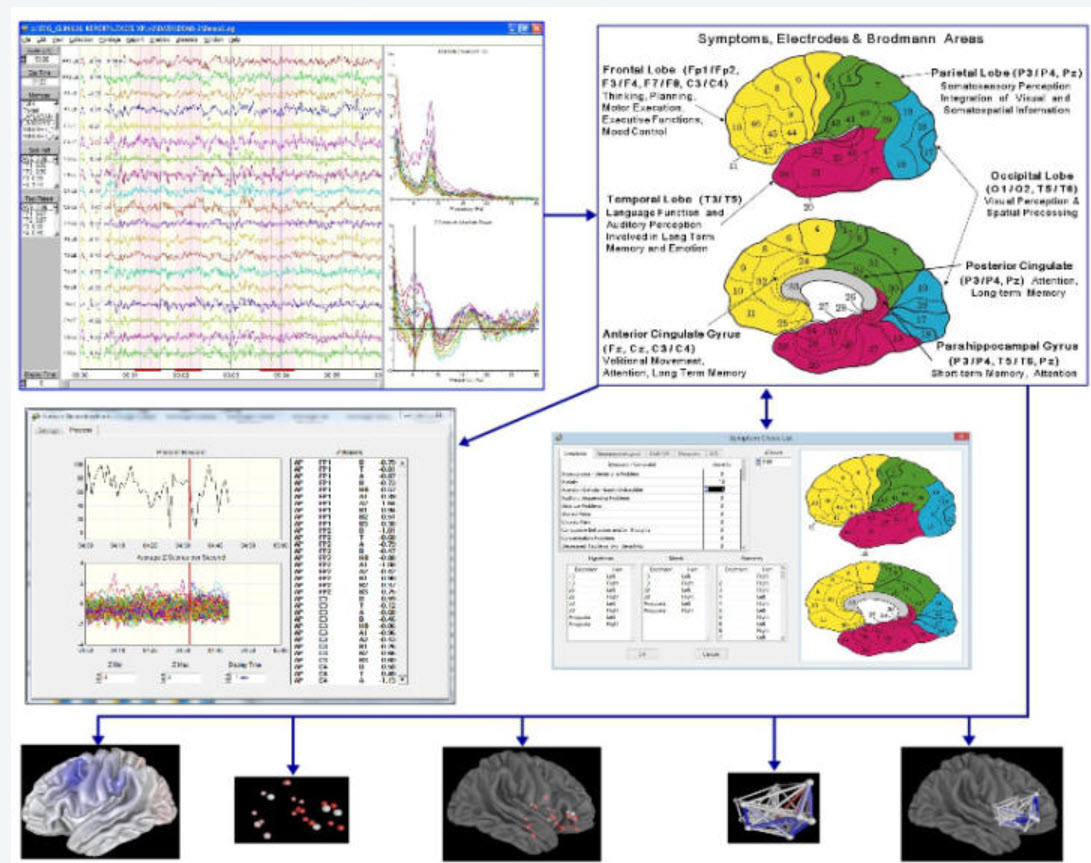

Oscillatory timing is the brain's fundamental organizer of neuronal information. According to Buzsaki (2006), brain activity is associated with multiple nested rhythms that emerge from integrated and coordinated activity mediated by small-world networks that interact with each other through hubs and nodes. NeuroGuide™ graphic courtesy of Applied Neuroscience.

Cross-Frequency Synchronization

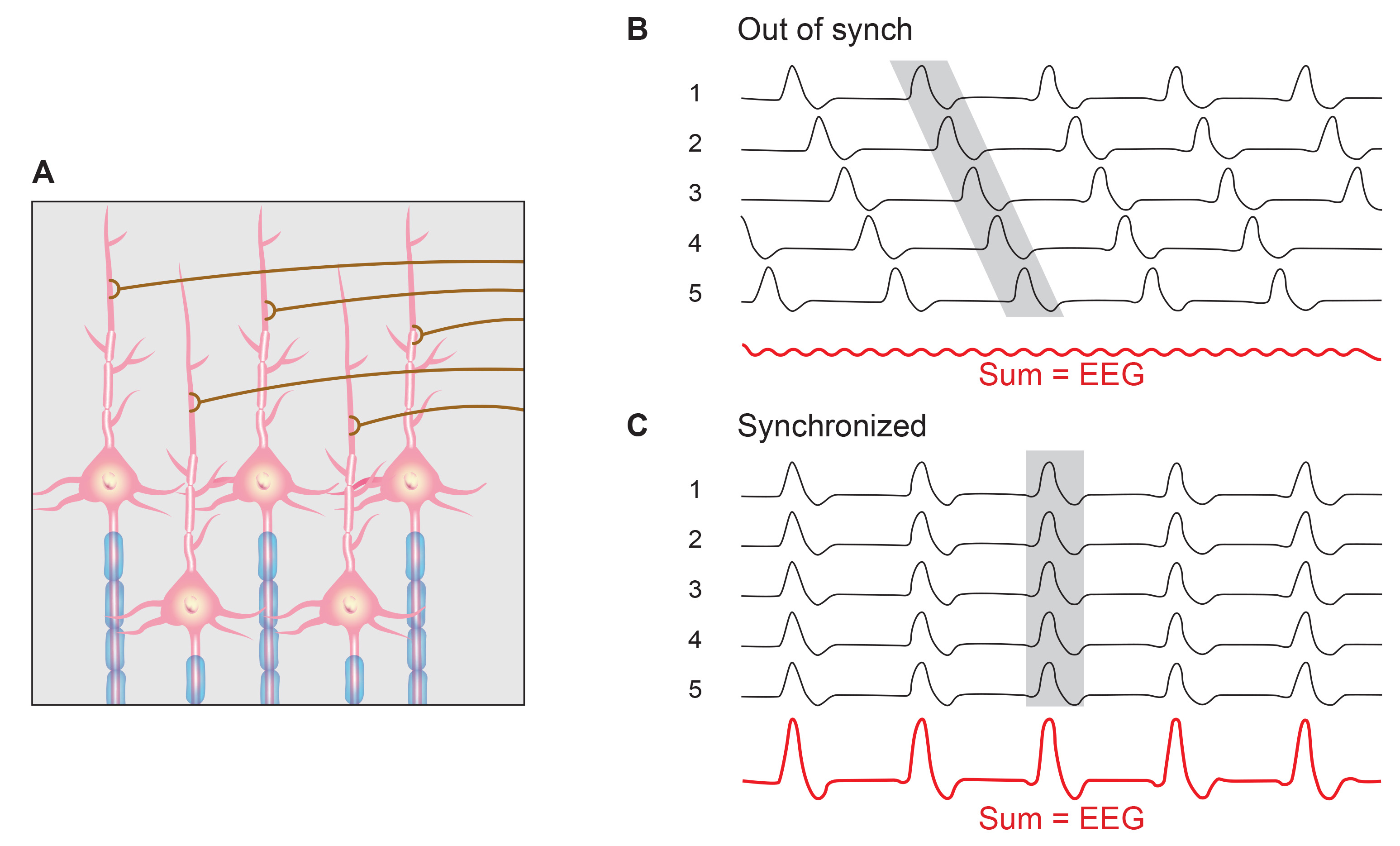

Slower frequencies organize and provide a matrix within which faster frequencies can function in a coordinated manner. Faster frequencies emerge from “bound networks” (Gunkelman, 2005), meaning that as networks responsible for slower, rhythmic frequencies become synchronized or bound together, faster frequencies emerge due to neuronal activity arising from these bound networks. Scalp EEG frequencies represent the synchronized firing of multiple neurons. The more neurons firing synchronously at a given frequency, the higher the voltage (amplitude) of that frequency.

For example, when the eyes are open, visual processing systems made up of millions of neurons are busy responding to incoming sensory input from the thalamocortical relay (TCR) system that involves ascending pathways from the thalamus mediated by the reticular nucleus of the thalamus (nRt). When the eyes are closed and visual input is no longer present, the visual processing neurons respond to a rhythmic signal, coming from the TCR system that results from interactions between the thalamus and the nRt, which also respond to ascending neurochemical inputs from the brainstem and reticular activating system (Cox et al., 1997).

This rhythm is commonly called the alpha rhythm (Berger, 1929) or the posterior dominant rhythm (PDR). When visual neurons collectively fire in response to this rhythmic input from the thalamus, the amplitude of the alpha signal increase.

This is called the alpha response.

Visual neurons begin to process the incoming information relayed by the TCR system when the eyes are opened. So fewer neurons are responding to the rhythmic PDR input, and the amplitude of alpha measured from the scalp decreases.

This is known as alpha blocking.

The same number of neurons may still be active, but since they are now functioning more independently and each grouping of neurons has a separate task, the overall voltage of the EEG as a whole decreases. Reduced synchrony of neuronal firing results in decreased amplitude.

Local Field Potential (LFP)

LFP and subsequent EEG activities are generated by the sum of postsynaptic potentials from the synchronized excitation of neurons, reflecting input into the neurons. Greater firing synchrony produces larger potentials on the scalp surface. Graphic redrawn by minaanandag on fiverr.com.

Global and Local Synchronization

Every day, waking activity results from relatively weak interactions in local groupings of cortical neurons, organized by slower, rhythmic patterns. Global synchronization generally occurs during resting states and in various stages of sleep, which results in the integration and consolidation of experiences, memories, and skills.

A-T training may facilitate improved global synchronization within a semi-waking state resulting in the benefits and experiences detailed in this section.

History and Development

The historical basis of A-T EEG training in neurofeedback begins with Joe Kamiya, who demonstrated that individuals could be trained to control alpha activity when given adequate information (feedback) about the state of their alpha activity (Ancoli & Kamiya, 1978; Kamiya 1961, 1962, 1969).

This was followed sometime later with a study conducted by Joe Kamiya and Jim Hardt on using alpha training for anxiety. This study provided training to increase alpha amplitude (Hardt & Kamiya, 1976).

Caption: Joe Kamiya and James Hardt

Menninger Foundation

In 1966, Elmer and Alyce Green of the Menninger Foundation began a series of Voluntary Controls projects that continued for several decades. Meditators, healers, average individuals, and others were studied to identify physiological measures of voluntary control of internal states.Along with Dale Walters and other staff, the Greens trained many individuals, including clinicians, to control peripheral skin temperature, electrodermal response, and EEG, focusing on theta, alpha, and beta frequency bands.

One of the clinicians who attended these training was Eugene Peniston, a psychologist from Colorado who published a seminal work on using A-T training with clients in substance use disorder programs.

Subsequently, Eugene Peniston (Peniston & Kulkosky, 1989, 1990) used a protocol called A-T training, based upon the Greens' work, with individuals in the alcohol treatment program at the Fort Lyons Veterans Administration Medical Center program where he worked. During each training session, he provided information feedback in the form of two different audio tones, one representing the voltage of theta activity and the other representing the voltage of alpha activity.

Caption: Eugene Peniston

The goal of the training protocol was to initially increase alpha activity and then subsequently to allow for the decrease of alpha activity and the increase of theta activity, as the participant transitioned into what has been called the crossover state but is also commonly thought of as a slightly disconnected reverie state, in which input from the external world is minimized, and an internal relaxing state is promoted. Peniston also combined his protocol with hypnotic inductions and suggestions and post-session processing after each training to facilitate a change in attitude and belief regarding the consumption of alcohol.

Peniston’s results were impressive, though the number of participants was quite small; only 10 individuals were in the treatment group and 10 in the control group. However, after a year of follow-up, all of the individuals in the control group had returned to using alcohol and subsequently to treatment. In contrast, 8/10 of the treatment group had maintained abstinence.

Other researchers and clinicians were also instrumental in developing this training approach, including Barbara Brown (Brown, 1974) and Elmer and Alyce Green (Green & Green, 1977). Their contributions facilitated Peniston’s development of this intervention.

Caption: Barbara Brown, and Elmer and Alyce Green

Subsequently, Tom Budzynski, Lester Fehmi, and Martin Wutkke pursued independent studies into training in this state of relaxed and introspective consciousness (Budzynski, 1976).

Caption: Thomas Budzynski, Lester Fehmi, and Martin Wuttke

William Scott and David Kaiser (2005) published a study in the American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse on the effects of an EEG biofeedback protocol on a mixed substance abusing population in an inpatient treatment setting.

Caption: William Scott and David Kaiser

Scott and Kaiser randomly assigned individuals in an inpatient treatment program for polysubstance abuse to an active training group or a control group. The active training group initially received beta and SMR training to assess attentional variables and then received A-T training. Individuals in the treatment group remained in treatment for a longer period. Subsequently, they had improved abstinence records with 77% abstinence in the experimental training group compared with 44% of the subjects in the control group. The study also examined MMPI data and showed improvement on various subscales and improvements in attention and focus, and ability to function in day-to-day life.

Burkett and colleagues (Burkett et al., 2005) published a study in the Journal of Neurotherapy reporting on a study using neurofeedback training to treat crack cocaine dependence, partially sponsored by the University of Texas and the Southwest health technology foundation. This study also showed improved treatment retention and a significant improvement in abstinence and in gainful employment of individuals who participated in the training. This group also studied improvements in depression and anxiety and found significant positive changes.

Subsequently, various individuals and clinical practice groups have conducted single case studies and small-N intervention studies and published papers showing similar results. A-T training continues to be an area of study for various issues, including PTSD (Nicholson, 2018, 2019, 2020) and applications for optimum performance (Gruzelier, 2014, 2014) that will be discussed in the applications section.

Benefits of A-T Training

Research participants reported "transformative" experiences including:

Spiritual and religious imagery

Memory recall experiences

Insight into personal behaviors and patterns

Changes in interpersonal relationships

Understanding of purpose

Resolution of long-standing anxiety and depression

Release of trauma responses and reactivity

Improved self-esteem /self-image

Abstinence from substance and behavioral addictions

Comparison of Interventions

Patricia Norris, Steven Fahrion, and others split off from the Menninger Foundation in 1993 to form the Life Sciences Institute of Mind-Body Health. They conducted a 5-year study of A-T training in a prison population (described in Norris, 2017).

Two groups of participants all received the following self-regulation, educational and supportive components of the study: Temperature training, breath training, didactic presentations on philosophy, psychodynamic aspects of self, and psychosynthesis exercises. Participants were treated with “deference, respect, and compassion.” One group also received 45 daily sessions of A-T neurofeedback training.

The results of a 2-year follow-up of participants (N = 35) showed encouraging results compared to standard substance use disorder (SUD) treatment in prison environments, typically with 10-20% "survival" rates defined by abstinence, no violations, and no criminal activity.

At a 1-year follow-up, 78% of the A-T group survived compared with 75% of controls. At a 2-year follow-up, 69% of the A-T group survived compared with 64% of the control group.

Younger participants had somewhat different results, suggesting that the A-T training was a more critical component for this group. At a 1-year follow-up, the A-T group had a 74% survival rate compared to 54% for controls. At a 2-year follow-up, the A-T group had a 60% survival rate compared with 45% for controls.

African-American and Hispanic participants also had results suggesting improved results with A-T training. At a 1-year follow-up, the A-T group had a 70% survival rate compared to 48% for controls. At a 2-year follow-up, the A-T group had a 48% survival rate compared with 40% for controls.

What Was the Mechanism of Change?

This study shows that the overall treatment program was quite effective compared to standard interventions. The difference between A-T and control group results was not statistically significant when the groups were viewed as a whole. However, age and ethnicity functioned as moderator variables.It appears that the overall design and implementation of the program was likely the most crucial aspect, and the A-T training was one effective component of that broader effort.

As noted in the Therapeutic Relationships section of Neurofeedback Tutor, the relationship between the clinician and the client is one of the most important components in any intervention.

This is particularly critical when providing A-T training because the desirable state identified as the crossover state requires complete trust on the part of the client so that they can let go of emotional, psychological, and physical defenses that would prevent them from allowing the type of disconnection from outside sensory input necessary for the state to occur.

Clinicians must work to engender this trusting relationship before implementing A-T training. This is one reason why many clinicians use a variety of additional interventions before and/or concurrently with A-T training.

Some of those interventions include:

Breathing, including heart rate variability (HRV) training

Guided relaxation

Peripheral temperature training

EMG biofeedback

Electrodermal biofeedback

SMR, beta, and other amplitude-based neurofeedback protocols

Z-score based neurofeedback approaches

Hypnotic inductions

Behavior change scripts and suggestions

Post-session psychotherapy, processing, and interpretation

What Role Does A-T Training Play in the Changes Experienced By Clients?

The client’s ability to enter the desired state may depend upon many factors: set and setting, expectations, clinician self-training, and interpersonal skills.The ability to enter the reverie state appears to result in significant opportunities for change, which can also occur from multiple interventions such as:

Mindfulness meditation

Biofeedback, including HRV training

A-T training

Other types of EEG biofeedback

Other self-help and behavior change interventions such as hypnosis and psychotherapy

Interventions that lead to desirable states appear to have one thing in common – it is difficult for the client or student to know when they are in the state, getting close to the state, or very far away from the state.

A-T neurofeedback, when done correctly, provides constant information about where one is on the continuum. This allows the client to move toward and experience the desired state more quickly and facilitates faster and more accurate skill acquisition.

A-T Training Protocols

A variety of approaches to A-T training have been developed. The initial protocol developed by Eugene Peniston (Peniston, 1989, 1990) involved two separate audio tones: alpha amplitude and the other representing theta amplitude. When alpha amplitude increased, the alpha tone occurred more frequently, and when theta amplitude increased, the theta tone occurred more often. In this way, the trainee could perceive the relative amount (amplitude or voltage) of each frequency band and could practice various strategies to accomplish this task to increase theta and decrease alpha. The feedback guided the trainee and reinforced the desired state change behavior, resulting in the so-called crossover state.

Some clinicians have found this protocol somewhat complicated to administer. Peniston prescribed threshold changes to elicit a shift to the crossover state, beginning with a setting that rewarded alpha 50 to 70% of the time and rewarded theta approximately 20 to 40% of the time. As training progressed, the percentage of the alpha reward tone was allowed to decrease as the signal amplitude decreased. In contrast, the theta reward tone was allowed to increase if the theta amplitude increased. However, the instruction was to maintain the theta reward tone at approximately 40%, even if voltage decreased to provide at least that minimal level of positive reinforcement.

As noted, some practitioners attempting to train clients with this approach found this difficult to administer correctly, and some clients became confused as to the desired signal. Subsequently, a simplified and widely-used approach was developed that utilizes the theta-alpha ratio to simplify the training protocol and provide a single-tone feedback signal representing the crossover state. Often the trainee is provided with a tone or some other audio indicator that they have exceeded a certain threshold indicating that theta has increased in amplitude over alpha amplitude, suggesting that the crossover state has occurred.

This is a simple protocol that has been incorporated into a variety of commercial neurofeedback platforms such as the Thought Technology BioGraph system and the Nexus/BioTrace+ system from Mind Media. Concerns about this simplified approach include the lack of specificity in the training protocol and the lack of feedback to inhibit undesirable changes in the EEG, leading to negative reactions and the lack of a well-defined goal.

The theta/alpha ratio is not precise since the band frequencies are quite broad. An increase in the slower theta component can increase the feedback reward signal but may not represent the desirable crossover state. Additionally, the client may not even produce typical alpha increases initially. Therefore, the simple ratio feedback approach lacks the precision to identify desirable states and differentiate between causal factors resulting in increases or decreases in positive feedback.

Finally, there is no indicator of whether the client is close to the goal, far away from the goal or somewhere in between. A single tone representing the crossover leaves the client wondering where they are on the continuum of alertness and awareness.

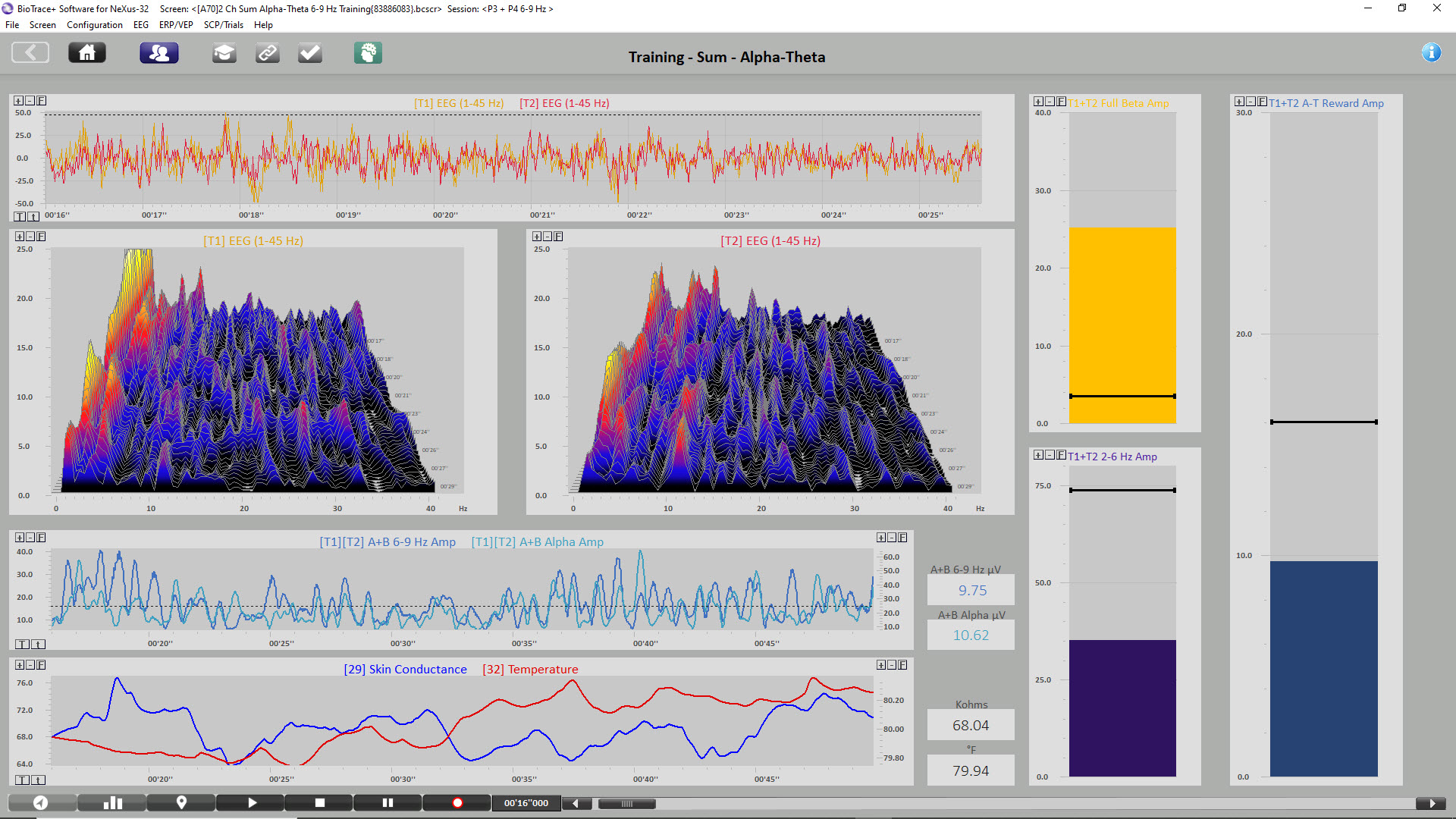

Targeted Training - 6-9 Hz

Following significant experimentation and clinical experience, John Anderson and others developed a protocol that involves training the frequency band from 6-9 Hz, which is the actual frequency band of the so-called crossover state. This frequency band straddles the standard 4-8 Hz theta and 8-12 Hz alpha frequency bands. This protocol is combined with an inhibit channel that prevents an increase in 2-6 Hz activity. When allowed to increase during A-T training, it results in what is often known as an abreaction or negative reaction, sometimes involving traumatic recall or depersonalization experiences.Through experience, using the 2-6 Hz frequency band to inhibit this transition to a more sleep-like state appears to prevent these negative reactions. Additionally, a frequency band from approximately 13-36 Hz is used to prevent an increase in faster frequency EEG patterns associated with cognitive activity, thereby ensuring that the client remains in the relaxed reverie state without engaging in thinking and problem-solving activities. This does represent a somewhat more complex approach to the A-T training protocol but is more likely to produce a desirable outcome without the dangers of negative reactions or excessive cognitive activity.

Reward Feedback

Reward feedback is a proportional audio signal, usually music, that increases and decreases in volume in direct proportion to the changes in 6-9 Hz amplitude. Clients can select their audio from calming, relaxing musical choices.The volume changes in the audio selection allow the client to know, continuously, where they are on the continuum from a typical eyes-closed alert state to the deep reverie state associated with the optimum experience. This is similar to the hot/cold game played by children.

Inhibit Feedback

The low-frequency inhibit (2-6 Hz) feedback is a recording of birds chirping that only sounds above a set threshold and becomes louder as the amplitude of this signal increases. This allows the client to be gently alerted when shifting into this lower frequency state without being startled out of the desirable reverie state. Most clients associate birds chirping with waking up in the morning, so it seems to represent an intuitive indicator that is easy to remember.The high-frequency inhibit (10-36 Hz) is a recording of ocean wave sounds with an inverse proportional relationship to the amplitude of this signal. It becomes louder as the "busy brain" decreases, thus rewarding a decrease in cognitive activity. The ocean wave sound and the rewarding music blend to create a calming and reinforcing auditory environment that encourages the correct state while providing constant, meaningful feedback to guide the client.

Sample Training Session

The image below shows the beginning of a 2-channel A-T training session. Note that the eyes closed EEG shows no clear posterior rhythm (alpha) and that peripheral skin temperature is 79.94o F measured from the small finger of the non-dominant hand, indicating increased SNS activity. GSR/SC is shown as resistance in Kohms, where higher values indicate decreased sweat gland activity measured from the palm of the non-dominant hand. Current GSR readings are 68.04 Kohms, which indicates increased arousal/anxiety. The sum of the P3 + P4 6-9 Hz activity is 9.75 μV, while 8-12 Hz alpha is 10.62 μV. Graphic © John S. Anderson.

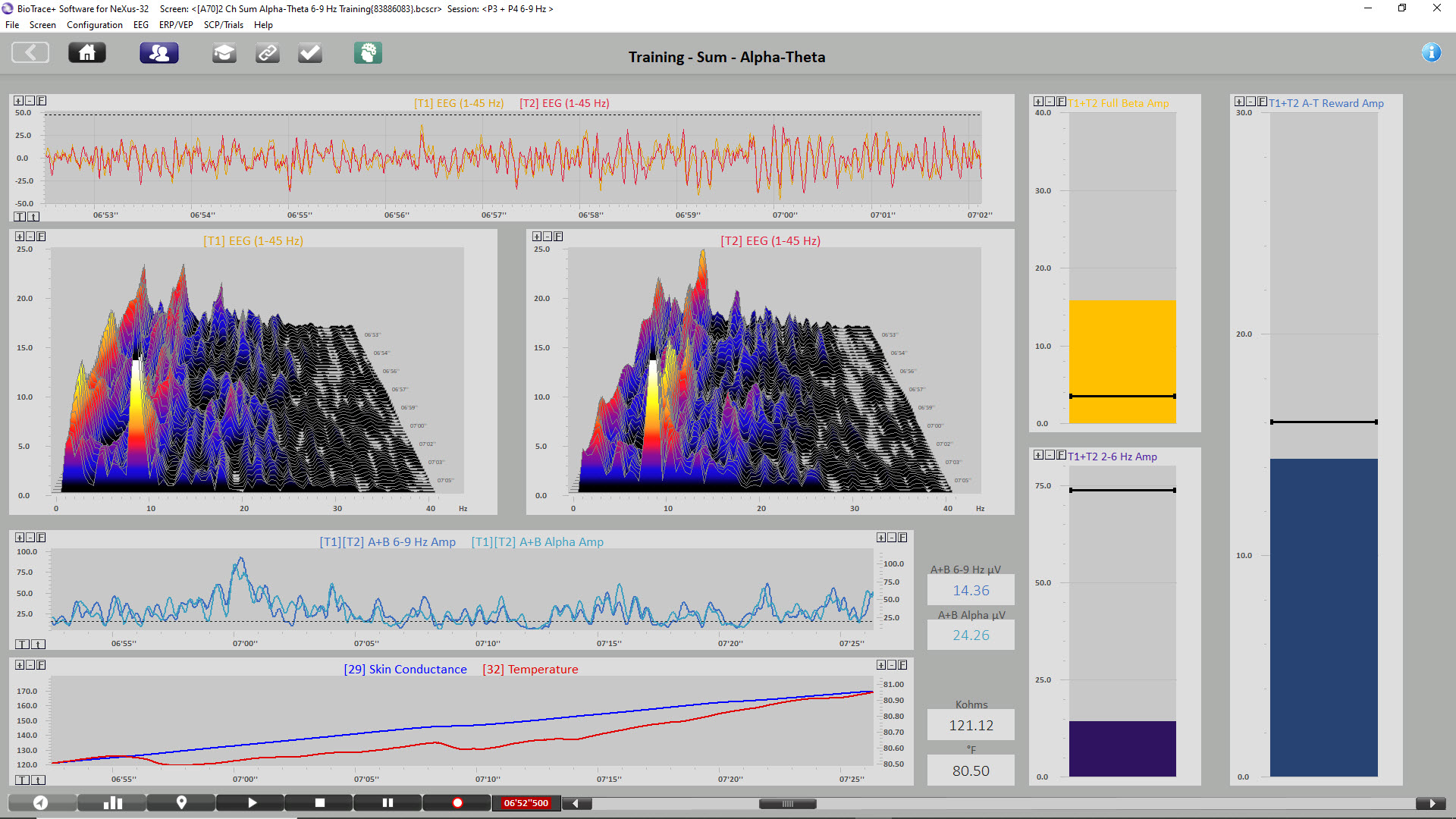

The image below shows the same session when the initial increase in alpha amplitude occurs. Peripheral skin temp has increased to 80.50o F, and GSR has increased to 121.12 Kohms, both indicating decreased arousal. P3 + P4 6-9 Hz activity has increased to 14.34 μV, while 8-12 Hz alpha has increased to 24.26 μV. Graphic © John S. Anderson.

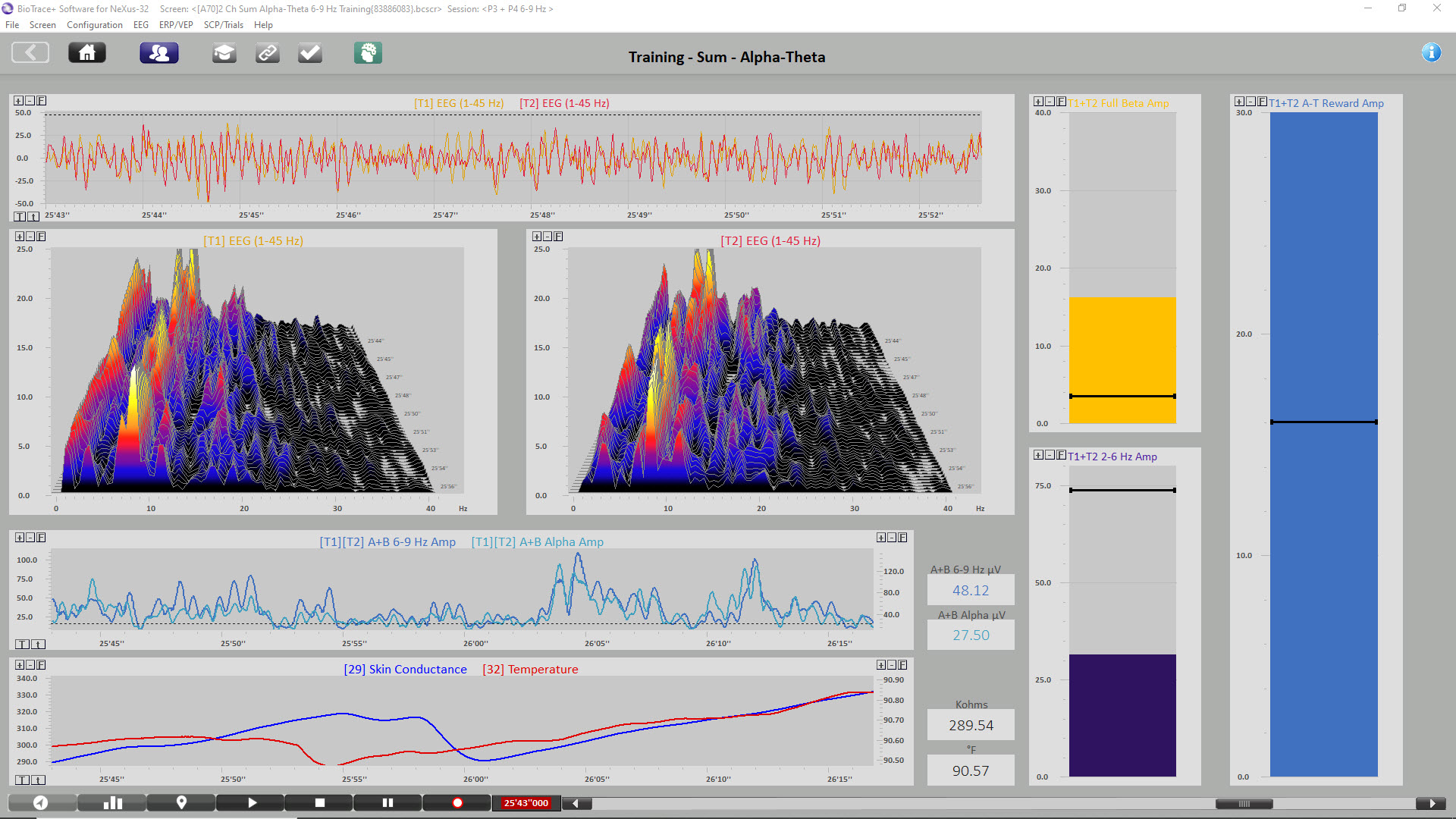

The image below shows the same session near the end. Peripheral skin temp has increased to 90.57

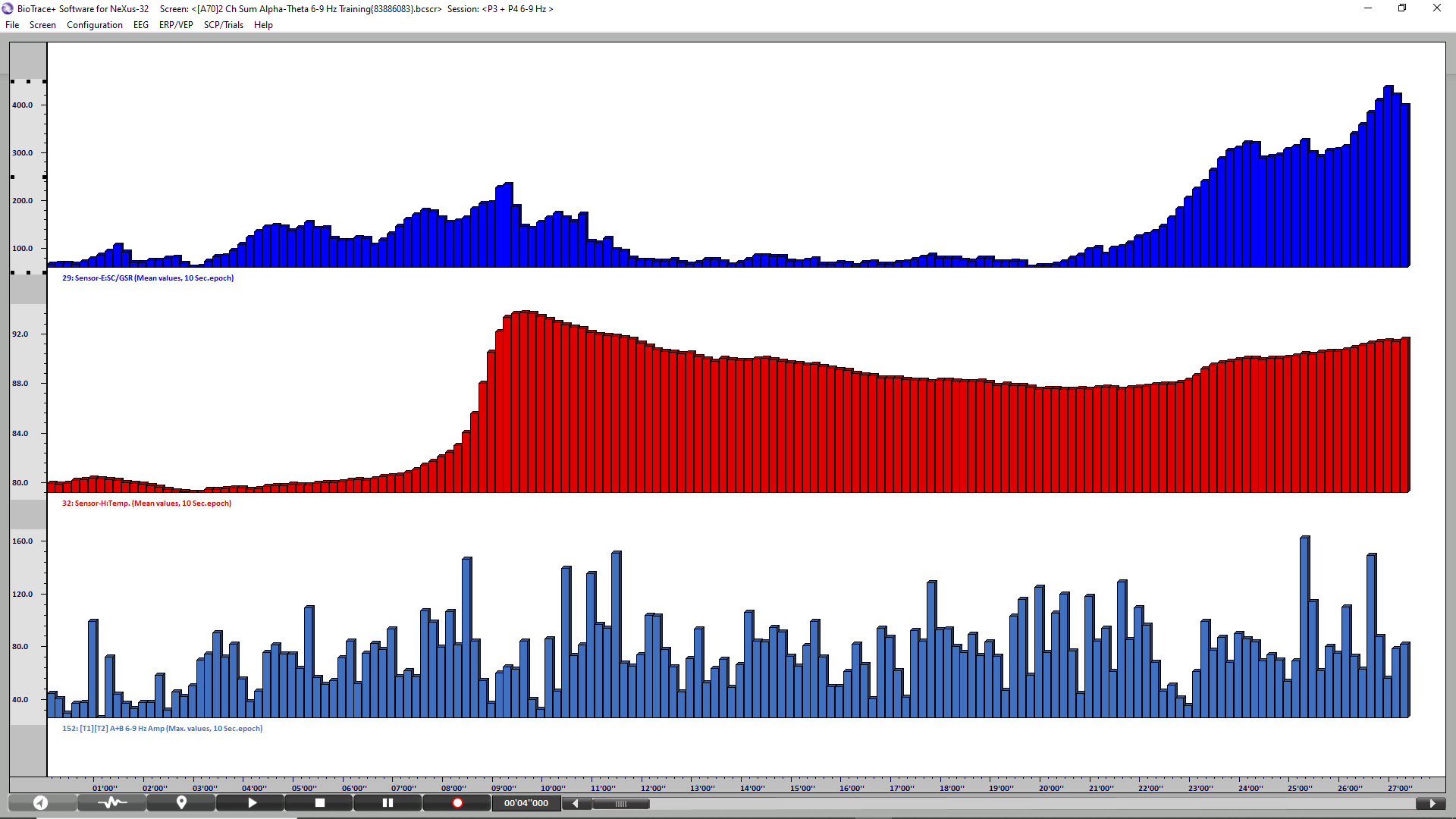

The final image is a summary screen that shows an increase in GSR (top), temperature (middle), and P3 + P4 6-9 Hz activity (bottom) across the session. Graphic © John S. Anderson.

Expected Results

This state encouraged by this training appears to be similar to that experienced during mindfulness meditation practice, where the participant or trainee experiences what is sometimes called a witness state, or the observation of the flow of consciousness, memory, and internal thoughts, without actively pursuing these thoughts. This training approach operationalizes this training so that the client experiences indicators in the form of audio rewards that encourage remaining in the state and discourage movement in either direction towards a deeper, more sleep-like state or an activated cognitive state.

Individuals participating in this training report increased receptiveness to suggestion, the experience of a therapeutic reverie state, free association and/or consciousness streaming experiences, experiences of representational and/or symbolic/spiritual/religious imagery, and experiences of emotional resolution, insight, and understanding.

The theories associated with this approach suggest that this state of brain activity is similar to that experienced in hypnotic induction states and in deeply relaxed and light sleep states associated with memory consolidation.

Applications

Whatever the approach, A-T training has been utilized for a variety of different interventions, mostly falling into the loose categories of PTSD (Nicholson et al., 2020; Peniston, 1989, 1990), addictive behavior (Burkett, 2005; Kaiser, 2005; Peniston, 1989, 1990) and optimal performance (Gruzelier, 2014).

An example of optimum performance training using A-T training can be seen in Gruzelier’s (2014) work with musicians in a study published in Biological Psychology. He demonstrated improvements in three music domains: creativity/musicality, technique, and communication/presentation. His study showed improvements in all blinded, independently rated scales for the alpha-theta training group compared to an additional EEG training group using an SMR (12-15 Hz) reward and a non-training control group.

Caption: John Gruzelier

These results demonstrated that the effect is specific to the type of training (i.e., the frequency band or reward) as the SMR training group while improving technical scores associated with attention and motor control, did not show the same improvement in the other scales. The study also showed improved ratings overall for A-T training compared to a control condition.

Following Peniston’s initial studies with addictions and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), others have utilized this approach with PTSD clients in various of clinical environments. Nicholson and colleagues (2018, 2019, 2020) have published papers regarding the use of A-T training and identified changes utilizing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). They have also utilized fMRI feedback in addition to EEG-based feedback.

Cautions

Some practitioners in the field of neurofeedback (Thompson & Thompson, 2003) suggest that there is a significant probability of negative reactions to A-T training. Therefore, practitioners utilizing this intervention should have advanced training in psychotherapeutic skills and additional training beyond introductory-level course work for neurofeedback practitioners.

Caption: Michael and Lynda Thompson

As we have noted, much of this concern results from a lack of understanding of the process associated with this protocol and an incorrect application of the training, including a lack of appropriate indicators to the client regarding undesirable frequency activity.

However, this protocol is also known to encourage a decrease in emotional and psychological defenses and should be used with caution with individuals with a history of trauma. Client preparation is essential, as is true with any intervention. Clients should be instructed to immediately inform the practitioner of any negative reactions so that corrective training and/or a calming intervention such as breath training via heart rate variability feedback can be implemented.

One of the characteristics of this training is a decrease in limbic system arousal. This is seen in decreased anxiety, easier transitions to sleep and deeper, more restful sleep, a long-term overall reduction of limbic system activation, often a characteristic of persistent anxiety and PTSD, insulation from the stress of daily life events, and improved state management and stability.

There is evidence that this state may also be similar to that identified in fMRI studies as the default mode network, sometimes known as the resting state network. This network of connections in the brain is associated with what is sometimes known as the self-referential state that accompanies a state of self-awareness associated with memory recall and non-directed cognition that appears strikingly similar to that described by individuals participating in A-T training.

The technical aspects of this type of training are specific to the training platform, and practitioners will need to familiarize themselves with their systems' specific software and hardware characteristics.

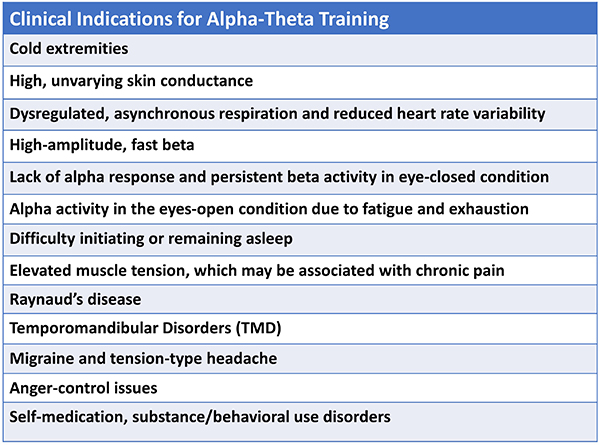

Typical clinical indications for A-T training include clients with the following presenting symptoms.

Practitioners have used various pre-training options to facilitate their client’s ability to access the desirable state during A-T training. Peniston (1989, 1990) initially used 10 sessions of hand temperature training to criteria, which was 96°F. Scott and Kaiser (2005) used beta and SMR training to stabilize the nervous system before continuing A-T training. Other practitioners use heart rate variability training and/or a combination of training approaches depending on the client’s needs. Some optimal performance practitioners begin directly with A-T training, which may be their sole neurofeedback intervention.

Training protocols vary depending on the environment, the clientele, and the ability of the practitioner to provide sessions. Initially, Peniston used training sessions once per day for 30 sessions. Scott and Kaiser also used daily training sessions for a total of 30 A-T training sessions. Other practitioners have used various approaches, including once or twice weekly sessions, and some have utilized twice daily intensive training programs.

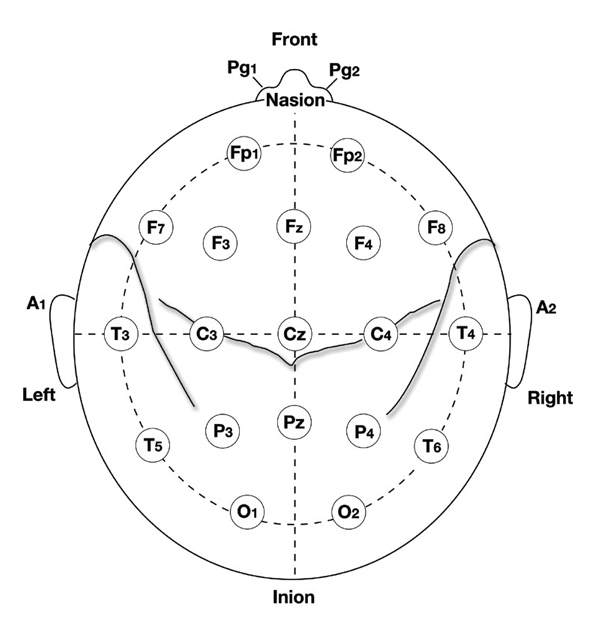

Peniston's (1989, 1990) initial approach used the O1 electrode location based on the 10-20 international electrode placement system. Subsequent practitioners have also utilized the Pz electrode location or the P3 and P4 electrode locations to facilitate two-channel A-T training. John Balven adapted the diagram below from Fisch (1999).

Peniston’s approach to training included behavior change scripts that would be read to the participant before the training session. He also conducted post-session debriefing conversations with his participants (personal communication, 1995). Other practitioners have also used behavior change scripts or scenarios, affirmations, behavior change, ideal behavior/life scenario instructions, and tape-recorded relaxation practices before each A-T session. The following are slides generated by the Nexus neurofeedback system that show initial A-T training sessions and subsequent training sessions indicating the crossover event occurring in single-channel and two-channel training approaches.

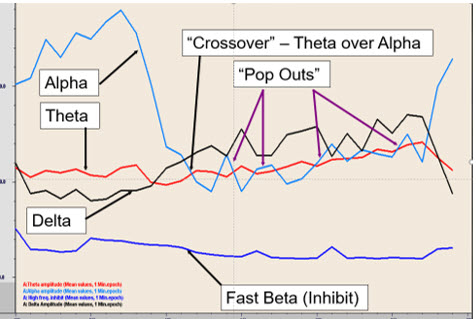

Initial A-T neurofeedback training session showing the initial increase in alpha amplitude followed by a decrease in alpha amplitude to the point where the theta amplitude is greater than the alpha amplitude resulting in brief crossover events.

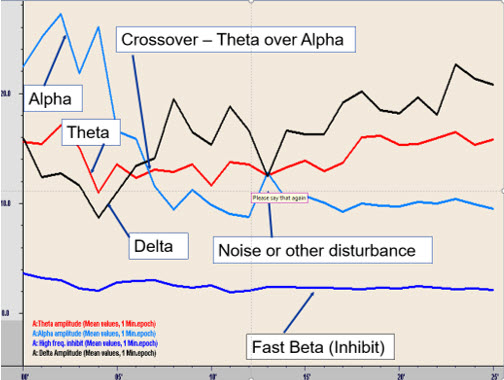

A later session of A-T training initially indicated the increase in alpha as the eyes are closed, followed by a transition to a decreased alpha, increased theta amplitude resulting in a prolonged crossover experience.

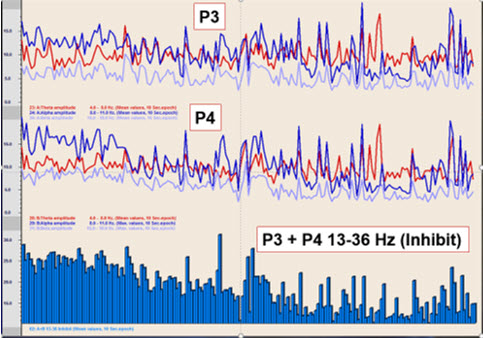

In an early training session with the client using two channels at parietal locations P3 and P4, showing some crossover events but primarily showing a significant decrease in the 13-36 Hz activity that indicates a marked decrease in the initial overactivity of the central nervous system.

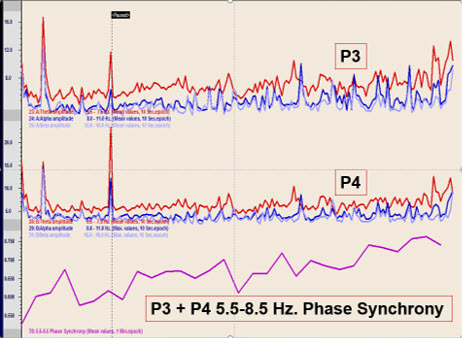

This graphic represents a later session with the same client showing prolonged crossover and an increase in phase synchrony between the two parietal locations in the 5.5-8.5 Hz frequency band used in this case.

This video takes the viewer through an A-T training demonstration using the Nexus/Biotrace system (Mind Media, Roermond, The Netherlands) using the training approach developed by John Anderson. The demonstration uses saved session data to illustrate the functions and discuss the threshold settings and training concepts. The video begins with a black screen, and the visual portion doesn't begin until the 1-minute mark.

Final Thoughts

Clients often have presenting conditions that require other training approaches specifically for ADHD and other attention issues, cognitive processing/slow processing issues, memory issues, sensory processing issues, and more. A-T training is often introduced following successful resolution of these issues. A-T training may help clients integrate and consolidate the changes that have occurred and may provide "perspective" on these changes and how they will affect their lives.

All biofeedback aims to help the client learn skills that they can then apply for the rest of their life. As clinicians, we want our clients to become independent, self-regulating individuals with new choices and opportunities. We want our clients to function optimally, no matter where they started. We want to help reduce limitations and restrictions so clients are free to pursue whatever goals they wish.

Glossary

alpha blocking: arousal and specific forms of cognitive activity may reduce alpha amplitude or eliminate it entirely while increasing EEG power in the beta range.

alpha response: an increased alpha amplitude.

alpha rhythm: 8-12-Hz activity that depends on the interaction between rhythmic burst firing by a subset of thalamocortical (TC) neurons linked by gap junctions and rhythmic inhibition by widely distributed reticular nucleus neurons. Researchers have correlated the alpha rhythm with relaxed wakefulness. Alpha is the dominant rhythm in adults and is located posteriorly. The alpha rhythm may be divided into alpha 1 (8-10 Hz) and alpha 2 (10-12 Hz).

alpha spindles: trains of alpha waves that are visible in the raw EEG and are observed during drowsiness, fatigue, and meditative practice.

alpha-theta training: a protocol to slow the EEG to the 6-9 Hz crossover region while maintaining alertness.

amplitude: the strength of the EMG signal measured in microvolts or picowatts.

beta rhythm: 12-38-Hz activity associated with arousal and attention generated by brainstem mesencephalic reticular stimulation that depolarizes neurons in the thalamus and cortex. The beta rhythm can be divided into multiple ranges: beta 1 (12-15 Hz), beta 2 (15-18 Hz), beta 3 (18-25 Hz), and beta 4 (25-38 Hz).

beta spindles: trains of spindle-like waveforms with frequencies that can be lower than 20 Hz but more often fall between 22 and 25 Hz. They may signal ADHD, especially with tantrums, anxiety, autistic spectrum disorders (ASD), epilepsy, and insomnia.

bipolar (sequential) montage: a recording method that uses two active electrodes and a common reference.

common-mode rejection (CMR): the degree by which a differential amplifier boosts signal (differential gain) and artifact (common-mode gain).

crossover state: the 6-9 Hz band targeted by A-T training.

default mode network (DMN): frontal, temporal, and parietal lobe circuits that are active during introspection and daydreaming and relatively inactive when pursuing external goals.

delta rhythm: 0.05-3 Hz oscillations generated by thalamocortical neurons during stage 3 sleep.

EEG activity: a single wave or series of waves.

epileptiform activity: spikes and sharp waves associated with seizure disorders.

Fast Fourier Transform (FFT): mathematical transformation that converts a complex signal into component sine waves whose amplitude can be calculated.

frequency: the number of complete cycles that an AC signal completes in a second, usually expressed in hertz.

functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI): an imaging technique that indirectly detects brain regions' oxygen use during specific tasks.

hertz (Hz): the unit of frequency measured in cycles per second

posterior dominant rhythm (PDR): the highest-amplitude frequency detected at the posterior scalp when eyes are closed.

power: amplitude squared and may be expressed as microvolts squared or picowatts/resistance.

Quantitative EEG (qEEG): digitized statistical brain mapping using at least a 19-channel montage to measure EEG amplitude within specific frequency bins.

sensorimotor rhythm (SMR): 13-15-Hz spindle-shaped sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) detected from the sensorimotor strip when individuals reduce attention to sensory input and reduce motor activity.

theta/beta ratio (T/B ratio): the ratio between 4-7 Hz theta and 13-21 Hz beta, measured most typically along the midline and generally in the anterior midline near the 10-20 system location Fz.

theta rhythm: 4-8-Hz rhythms generated a cholinergic septohippocampal system that receives input from the ascending reticular formation and a noncholinergic system that originates in the entorhinal cortex, which corresponds to Brodmann areas 28 and 34 at the caudal region of the temporal lobe.

z-score training: a neurofeedback protocol that reinforces in real-time closer approximations of client EEG values to those in a normative database.

Test Yourself on ClassMarker

Click on the ClassMarker logo below to take a 10-question exam over this entire unit.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, describe how clinicians have refined A-T training.

References

Ancoli, S., & Kamiya, J. (1978). Methodological issues in alpha biofeedback training. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 3(2). 159-183. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00998900

Berger, H. (1929). Über das Elektrenkephalogramm des Menschen. Archiv f. Psychiatrie, 87, 527–570.

Boyce, R., Glasgow, S. D., Williams, S., & Adamantidis, A. (2016). Causal evidence for the role of REM sleep theta rhythm in contextual memory consolidation. Science, 352(6287), 812-816. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad5252

Brown, B. (1974). New mind, New body: Biofeedback: New directions for the mind. Harper & Row.

Budzynski, T. H. (1976). Biofeedback and the twilight states of consciousness. In G. E. Schwartz & D. Shapiro (Eds.). Consciousness and self-regulation. Springer.

Burkett, V. S., Cummins, J. M., Dickson, R. M., & Skolnick, M. (2005). An open clinical trial utilizing real-time EEG operant conditioning as an adjunctive therapy in the treament of crack cocaine dependence. Journal of Neurotherapy, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1300/J184v09n02_03

Buzsáki, G. (2006). Rhythms of the brain. Oxford University Press.

Cox, C. L., Huguenard, J. R., & Prince, D. A. (1997). Nucleus reticularis neurons mediate diverse inhibitory effects in thalamus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 94(16), 8854-8859. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.16.8854

Davey, C. G., & Harrison, B. J. (2018). The brain's center of gravity: how the default mode network helps us to understand the self. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 17(3), 278-279. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20553

Green, E., & Green, A. (1977). Beyond biofeedback. Knoll Publishing Company.

Gruzelier, J. H., Holmes, P., Hirst, L., Bulpin, K., Rahman, S., van Run, C., & Leach, J. (2014). Replication of elite music performance enhancement following alpha/theta neurofeedback and application to novice performance and improvisation with SMR benefits. Biological Psychology, 95, 86-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.11.001

Hardt, J., & Kamiya, J. (1976). Some comments on Plotkin’s self-regulation of the electroencephalographic alpha. J. Exp. Psychol., 105(1), 100-108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.105.1.100

Kamiya, J. (1961). Behavioral, subjective, and physiological aspects of drowsiness and sleep. In D. W. Fiske, & S. R. Maddi (Eds.). Functions of varied experience. Dorsey Press.

Kamiya, J. (1962). Conditioned discrimination of the EEG alpha rhythm in Humans. Abstract presented at the Western Psychological Association meeting.

Kamiya, J. (1968). Conscious control of brain waves. Psychology Today, 1, 56-63.

Kamiya, J. (1969). Operant control of the EEG alpha rhythm and some of its reported effects on consciousness. In C. Tart (Ed.), Altered states of consciousness. John Wiley and Sons.

Nicholson, A. A., Densmore, M., MicKinnon, M. C., Neufeld, R. W. J., Frewen, P. A. Théberge, J., Jetly, R., Richardson, J. D., & Lanius, R. A. (2019). Machine learning multivariate pattern analysis predicts classification of posttraumatic stress disorder and its dissociative subtype: A multimodal neuroimaging approach. Psychol Med, 49(12), 2049-2059. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171800286

Nicholson, A. A., Ros, T., Densmore, M., Frewen, P. A., Neufeld, R. W. J., Théberge, J., Jetly, R., & Lanius, R. A. (2020). A randomized, controlled trial of alpha-rhythm EEG neurofeedback in posttraumatic stress disorder: A preliminary investigation showing evidence of decreased PTSD symptoms and restored default mode and salience network connectivity using fMRI. Neuroimage Clin. 28, 102490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102490

Nicholson, A. A., Ros, T., Jetly, R., & Lanius, R. (2020). Regulating posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms with neurofeedback: Regaining control of the mind. Journal of Military Veteran and Family Health 6(S1), 3-15. https://doi.org/10.3138/jmvfh.2019-0032

Peniston, E. G., & Kulkosky, P. J. (1989). Alpha-theta brain wave training and beta-endorphin levels in alcoholics. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 13, 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00325.x

Peniston, E. G., & Kulkosky, P. J. (1990). Alcoholic personality and alpha-theta brain wave training. Medical Psychotherapy, 3, 37–55.

Scott, W. C., Kaiser, D., Othmer, S., Sideroff, S. I. (2005). Effects of an EEG biofeedback protocol on a mixed substance abusing population. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 31, 455-469. https://doi.org/10.1081/ada-200056807.

Weise, R., von Mengden, I., Glos, M., Garcia, C., & Penzel, T. (2013). P 153. Influence of transcranial slow oscillation current stimulation (tSOS) on EEG, sleepiness and alertness. Clinical Neurophysiology, 124(10), e137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2013.04.230