Ongoing Assessment

Overview

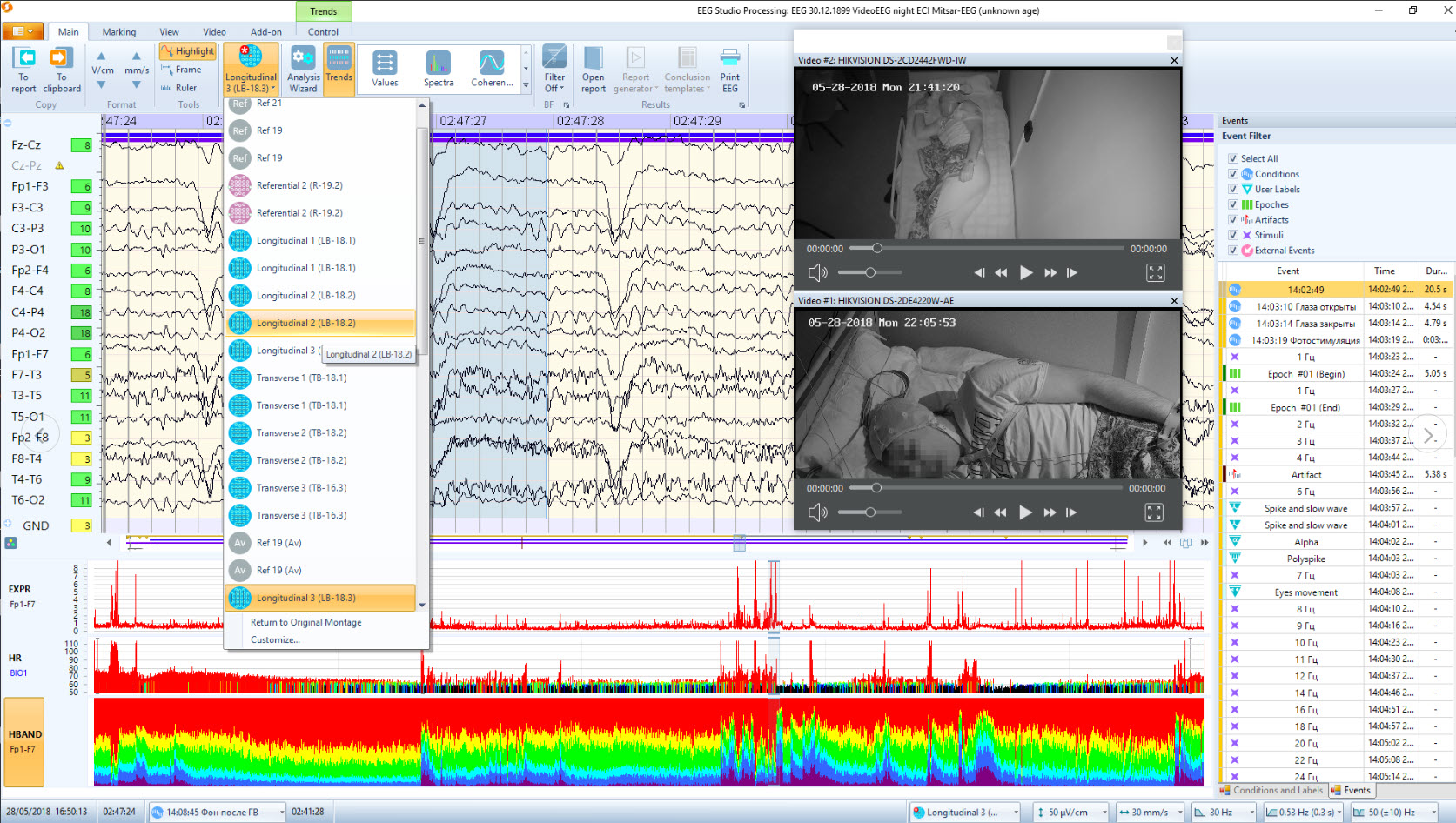

Intake and initial EEG assessment provide a baseline against which subsequent progress, or lack of progress, can be gauged. This is important because, despite the robust research evidence for the efficacy and effectiveness of neurofeedback as shown in groups that receive training (Schwartz & Andrasik, 2016; Tan, Shaffer, Lyle, & Teo, 2016), benefits are not guaranteed for individual clients. One purpose of ongoing assessment is to verify that expected outcomes occur and, if a good result does not happen, use continuous assessment data to adjust training protocols. Graphic courtesy of Mitsar.

Ethical principles involved in the ongoing assessment are related to questions of benevolence (i.e., is training helping?) and nonmalevolence (i.e., is training causing any harm?) (Beauchamp, 2003). Ongoing assessment is necessary to assure the former and avoid the latter, even if the harm is the continuing cost of time and finances for a treatment that does not help a particular individual. The ethical principle of autonomy involves whether the client wants to continue training. Ongoing assessment helps the client remain well-informed about the training outcome and can continue to provide consent to continue training. The ethical principle of justice may apply to neurofeedback training as training should be efficient (e.g., am I providing training efficiently enough to the current client that I do not unreasonably deny access to training to others?).

Additionally, ongoing assessment supports maintaining a positive working relationship by allowing the client and practitioner to examine outcomes and make evidence-based decisions collaboratively. Seeing progress through continuous assessment also motivates the client to persevere with training and apply skills that build on neurofeedback effects outside of the training session.

The process of reviewing data from ongoing assessment also may help the client to see relationships between their subjective states and behavior, or even environmental events. For example, the client may develop a self-awareness that when the subjective state they experience during neurofeedback occurs in a given situation outside the training environment, they can behave more effectively. Such self-awareness can motivate the client to reproduce the subjective state they have intentionally learned with neurofeedback in advance of or during relevant situations.

Neurofeedback trains EEG activity of the brain, and ongoing assessment of EEG activity provides an index of whether neurofeedback has the intended effect on brain activity. However, the client and practitioner are most likely interested in whether changes in EEG activity generalize to other domains such as emotional experience, cognition, physiological condition, and real-life behavior in situations that matter to the client. Therefore, in addition to ongoing assessment of EEG activity, it is usually the case that the client and practitioner will at least periodically use non-EEG measures during the ongoing evaluation. Therefore, continuous assessment typically includes using the same EEG variables as those used during intake and repeating non-EEG measures used during the intake to assess the generalization of possible EEG changes to changes in those problems that originally motivated the client to request neurofeedback.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit covers VI. Patient/Client Assessment - C. Ongoing Assessment.

This unit covers Measures and Methods and Decision-Making.

Please click on the podcast icon below to hear a full-length lecture.

Measures and Methods

EEG Variables

A natural measure to use for ongoing assessment is the EEG variable (e.g., SMR power) that has been chosen for training, based on the hypothesis that neurofeedback should produce a change in that variable (e.g., rewarding SMR should lead to SMR increase). Recent research has shown that neurofeedback at a single site may also have effects that generalize to other sites and brain networks (e.g., Nicholson, Ros, Densmore, Frewen, et al., 2020). Therefore, practitioners who have access to 19-channel qEEG hardware and software may additionally be interested in assessing how single-channel changes may have generalized to changes in network function (Thatcher, 2020).The movie below is a 19-channel BioTrace+ /NeXus-32 display of SMR activity © John S. Anderson. Brighter colors represent higher SMR amplitudes. Frequency histograms are displayed for each channel. Notice the runs of high-amplitude SMR activity.

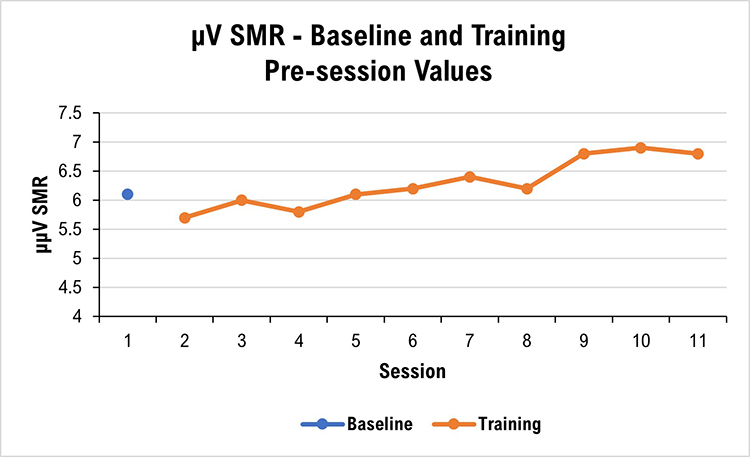

The EEG variable targeted for training is usually measured during a pre-training baseline for each session. The saved data can be artifacted. The value of the EEG variable can then be graphed from session to session, with the value from the intake assessment being used as a baseline for these within-training session baselines (see Figure 1).

Many neurofeedback platforms make it easy to collect and graph EEG variables of interest, whether derived from single or multiple channels. Some platforms include a graphing capability, while the results of other platforms need to be copied and then pasted into a spreadsheet for graphing.

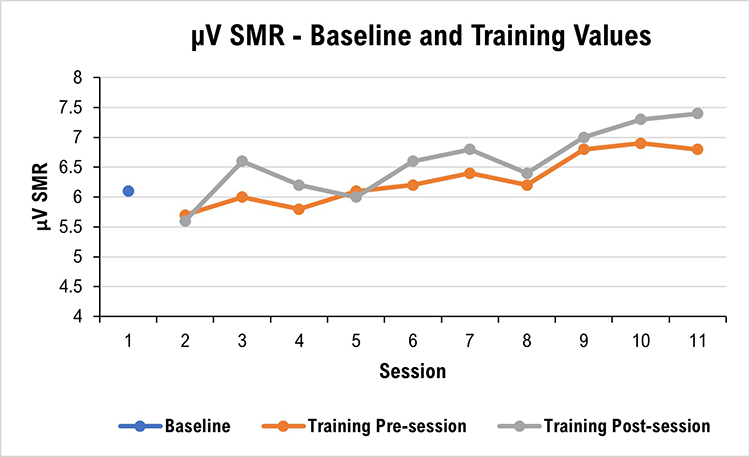

The EEG variable can also be measured again during a training session’s post-training baseline. This allows comparison with that session’s pre-training baseline and may show that the session’s training has produced a change in the intended direction. The pre-training and post-training baseline data from a series of sessions can be graphed separately or together, or a series of within-session change scores can be graphed (see Figure 2).

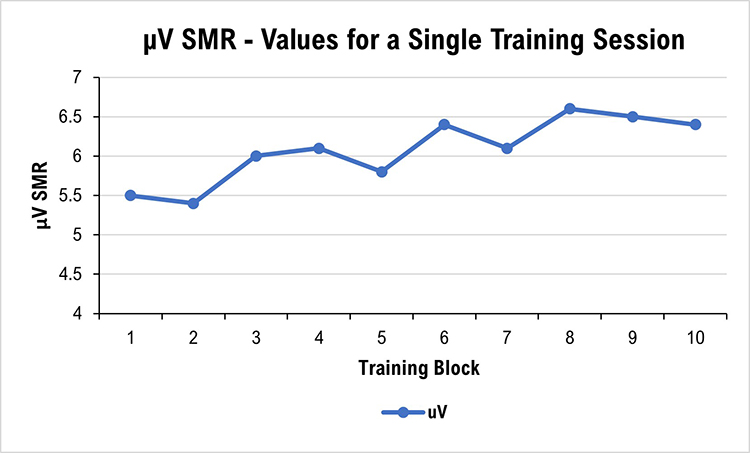

It can sometimes be interesting to graph EEG data from training blocks during a session. For example, if the client receives 10, 3-minute trials of neurofeedback in a session, the clinician can graph the series to show whether changes occur (see Figure 3).

Qualitative Anecdotal Report

One of the products of intake assessment is the choice of a goal that has practical consequences for the client (e.g., feel less depressed, feel more relaxed, experience fewer headaches, concentrate better, study longer, avoid people less). Goals may be specified in positive or negative terms (e.g., more of A, or less of B) and refer to either internal states (e.g., thinking, emotion, somatic experience) or to behavior (e.g., number of pages written) (Hurn, Kneebone, & Cropley, 2006).Ongoing assessment of a qualitative nature can provide a detailed and informative description of how the client’s presenting problem changes during training. Anecdotal reporting invites the client to describe a personal situation or anecdote, together with the various dimensions of internal experience and behavioral performance, to represent the current state of their presenting problem or goal achievement.

At the beginning of each session, the neurofeedback provider can ask the client or a collateral informant to describe changes they are observing in the problem or goal for which they initially sought neurofeedback training. For example, both the child receiving neurofeedback and their parent can be asked how distractible the child has been during the past few days and their responses compared. Or, they could be asked to describe the situation in which they were most distractible to provide an anecdotal report linked to a specific problem at a particular time and place. Practitioner notes can be compared from session to session to give an impressionistic view of change.

Ongoing qualitative assessment, at least for the first few training sessions, is also helpful concerning monitoring for the possibility of unwanted side-effects of training (e.g., fatigue, excessive arousal, headache). Graphic courtesy of Migraine Buddy.

Quantitative Self-Report

Although such problems and goals may be expressed somewhat imprecisely and colloquially by clients, it can be helpful to define them more formally or quantitatively. Quantification makes it possible to graph progress over time and more easily see change (Greenhalgh & Meadows, 1999).Internal subjective states can be quantified with visual analog or Likert rating scales that label points on the scale. It is helpful to structure items with either Likert or visual analog scales (VAS). The rating can then be quantified and graphed for later review by the client and practitioner (Joshi et al., 2015; Wewers & Lowe, 1990). Definition of the scale item and labeling points on the scale help make the scale more reliable and valid as a measurement tool. At the beginning of a session, the client can mark their typical state during the previous few days or their state at the time of the session. VAS pain scale graphic © Overearth/Shutterstock.com.

Behavioral problems or goals can be operationally defined (i.e., in terms of the operations used to construct the definition; Martin & Pear, 2019). For example, suppose increased concentration (an internal state) is the goal. In that case, duration of study time may be a useful behavioral goal to define in terms of minutes elapsed the previous day. At the beginning of a session, the neurofeedback provider can then ask the client to retrospectively estimate their study time during the day before the session.

One way of defining action-oriented or behavioral goals more formally is to use the SMART goals framework. SMART stands for specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (Bovend’Eerdt et al., 2009). Behavior analytic tactics (Cooper et al., 2007) can be used to address the specific, measurable, and time-bound components of SMART goals, for example, by defining goals in terms of frequency, intensity, and duration, and in terms of the context in which they should be met (e.g., during a typical week with ordinary stressors, a headache will occur not more than twice with an average duration of not more than 1 hour, and average severity of not more than 2 on a scale of 0 to 5). SMART goals graphic © Appleing/Shutterstock.com.

After intake assessment and definition of a SMART goal, the practitioner can quickly ask the client at the beginning of training sessions about the measurable feature of the SMART goal (e.g., for a socially anxious client, how many times did they speak at all to anyone besides the cashier during their most recent three trips for coffee?). Because the SMART goals are concrete and specific, the measurable rating that the client gives will tend to be reliable and, therefore, more valid than a response to a more open-ended question related to a general goal. Because a SMART goal can be easily quantified, their baseline and session-by-session values can be graphed for visual inspection and interpretation by the client and practitioner.

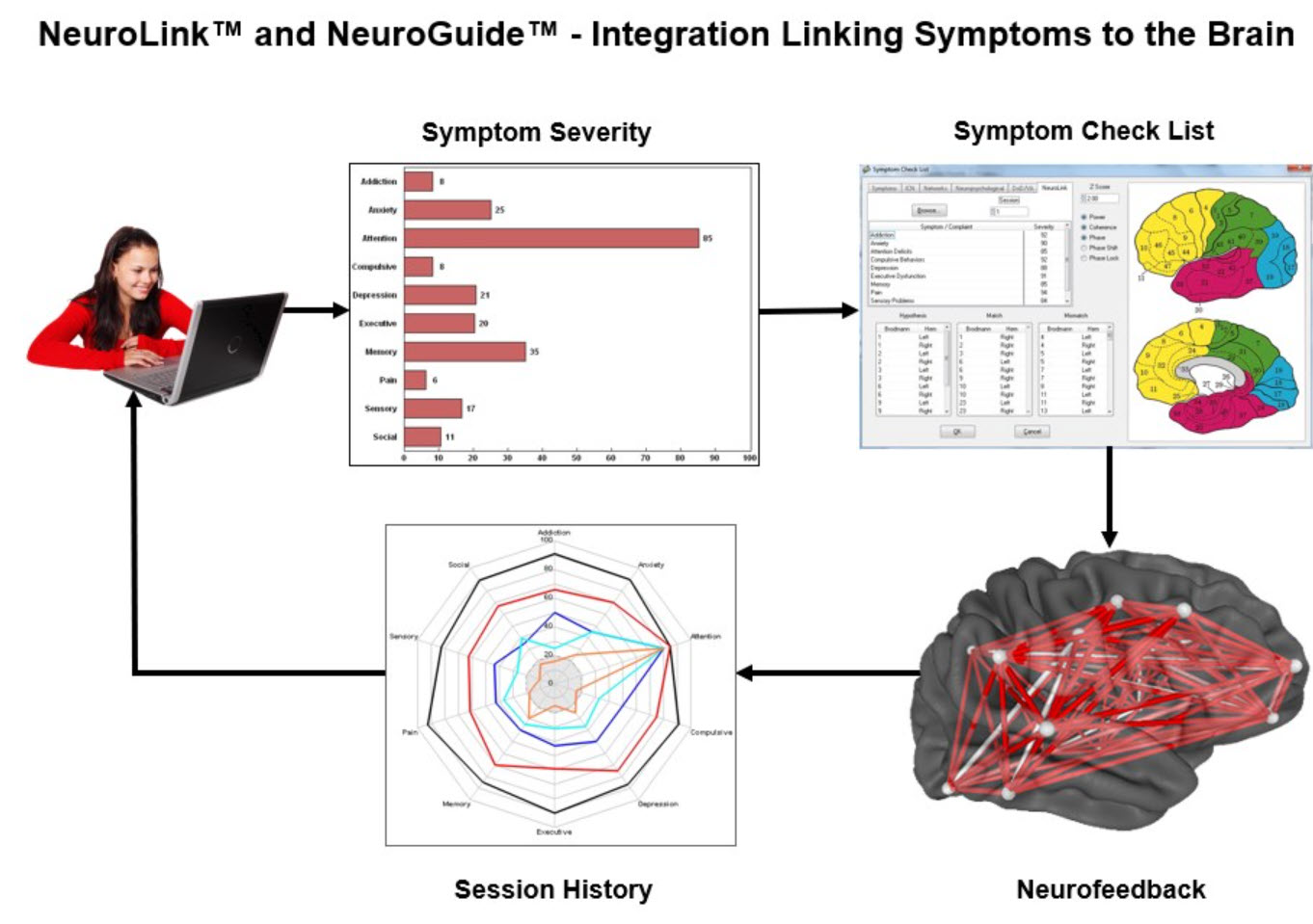

Applied Neuroscience's NeuroLink™ application integrates patient self-assessment with NeuroGuide™ to allow clinicians to target dysfunctional networks.

Self-Monitoring

Like the within-session reports described in the previous two sections, clients can be asked to make ratings at assigned times in assigned situations outside the neurofeedback session (e.g., at home after dinner, rate your level of calmness for the day taken as a whole). This type of self-monitoring of symptoms (e.g., stress, distractibility) or abilities (e.g., sustained attention, duration of time at a task, accuracy of task completion) relevant to the client’s presenting concerns can be started after intake assessment.Self-monitoring benefits the client by increasing their self-awareness in day-to-day situations and potentially strengthening their ability to self-regulate “internal” subjective experiences such as emotion, cognition, and tonic or reactive physiological states in service of effective behavior. Graphic courtesy of the Optimism family of mental health applications.

It can be useful to structure self-monitoring by identifying specific situations or times to use self-monitoring scales between training sessions. For example, the client can be asked to rate their concentration level during one or more particular classroom activities (e.g., completing algebra problems). Selecting a specific situation for rating helps to make the rating more reliable and valid by reducing variability due to differences among many situations.

It may be more relevant for other clients to use a time-based method for self-monitoring. The client can be asked, for example, to rate their level of calmness at the beginning of the day after their first hour of work or the end of the day based on their overall impression of the day as a whole. When self-monitoring between training sessions is used, it is essential to plan with the client to remember when to implement the measure. Specifically defined situational or temporal cues are effective in this regard. If self-monitoring in a particular situation is required, then verbal or visual reminders are helpful. For example, a post-it note in a notebook used for algebra can cue clients to rate their concentration level after class. Electronic alarms can also serve to prompt completion of the rating, and smartphone apps can be used in place of paper-and-pencil forms (Bakker & Rickard, 2018; Melbye et al., 2020).

Behavioral Observation

Direct observation of behavior (Cooper et al., 2007; Kamphaus & Dever, 2016) is often used in research and clinical settings to assess the baseline level with which an observable behavior of interest occurs. For example, a parent may count the number of interruptions a child makes during a period to calculate a rate per hour. A teacher may time record whether or not a student is studying at defined times during a class. These observations are readily quantifiable and can be graphed to track progress during an ongoing assessment. Graphic © Photographee.eu/Shutterstock.com.

Rating Scales

In contrast to self-report scales, rating scales have been evaluated for their psychometric properties (Baer & Blais, 2010; Tate, 2010). They provide a quick and valid method to assess progress during neurofeedback training, especially if they have already been employed during intake assessment. The domains that rating scales sample are numerous, including emotional, cognitive, and physiological experience and functional abilities. Completion of rating scales relevant to the client’s presenting concerns can be done periodically before training sessions or at home between training sessions. Examples of rating scales are the Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck, 1996) and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Graphic © PsychCorp.

Practitioners are increasingly teaching clients mindfulness meditation in conjunction with neurofeedback and biofeedback (Khazan, 2013). Mindfulness meditation produces physiological, cognitive, and emotional benefits. There is reason to think that adding mindfulness to neurofeedback training may improve training effects. The client taught to apply mindfulness during neurofeedback sessions is likely to be more conscious of the mind-body state that occurs when feedback is either present or absent. The resulting self-awareness can then be the basis for voluntary self-control, that is, the intentional recreation, either during a training session or during a relevant non-session situation, of the mind-body state reinforced during neurofeedback. If the practitioner does teach mindfulness meditation to their client, several psychometrically sound instruments can be used to measure the client’s increasing skill and application (Lau et al., 2006; MacKillop & Anderson, 2007).

Cognitive Tests

Tests of thinking and cognition can also be readministered during neurofeedback training to assess progress. However, challenges to doing so are the practitioner's time to administer the tests and the potential for spuriously inflated results due to practice effects. The former can be addressed in some cases with computerized tests that the client can complete after the practitioner provides instructions (e.g., CNS Vital Signs; Gaultieri & Johnson, 2006), while the latter can be addressed using alternate forms of tests that are vulnerable to practice effects (e.g., Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; Randolph et al., 1998). Graphic © Pearson.

Psychophysiological Assessment

Several platforms provide the ability to conduct concurrent neurofeedback and peripheral biofeedback. With such systems, psychophysiological measures can be easily recorded simultaneously with EEG measures. As described above, this may be done during each session before starting neurofeedback training or just following training. If peripheral biofeedback training is not provided, these measures assess the generalization of neurofeedback training effects to other relevant domains (e.g., skin conductance, skin temperature, respiration, heart rate variability, EMG).Decision-Making

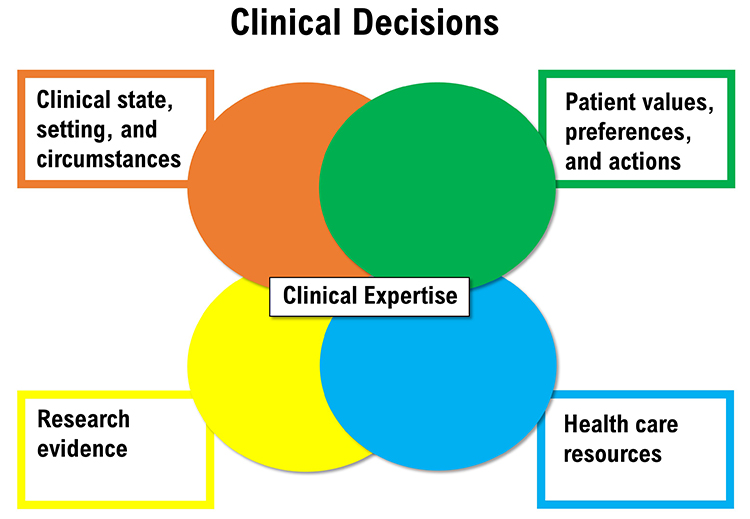

Ongoing assessment during neurofeedback occurs within the framework of evidence-based practice. The main components of evidence-based practice are scientific evidence, client condition, values and preferences, and available resources integrated by practitioner expertise (McMaster University Health Sciences Library, 2021, May 5; Melnyk, Fineout-Overholt, Stillwell, & Williamson, 2010) (Figure 4). In particular, ongoing assessment collects data that informs decision-making by the client and practitioner about whether to continue the neurofeedback protocol with which they began training, change the protocol, or discontinue training. Graphic created by authors.

Assessment results that show improvement encourage the continuation of neurofeedback until goals or a point of diminishing returns are reached. At that point, neurofeedback may be discontinued or new goals addressed.

When results show insufficient change, then the client and practitioner can consider different evidence-based protocols to apply (Tan et al., 2016).

Alternatively, reassessment may be helpful. If 19-channel qEEG methods have not already been used during the initial assessment, a 19-channel assessment may identify sites and networks that neurofeedback up to that point has not addressed.

For many clients, it may be the case that, however helpful neurofeedback is, it may be insufficient to resolve a presenting problem or reach a goal by itself. Integrating neurofeedback with other interventions, whether by one or more practitioners, is becoming more common. For example, Thompson and Thompson (2015) describe complementary methods such as heart rate variability training and transcranial electrical stimulation. Weiner (2017) reviews how neurofeedback and psychotherapy can be conducted together.

Some clients experience significant overriding developments during neurofeedback training that preclude successful treatment. For example, a client may develop a new medical condition or experience considerable family disruption. In these cases, training may be postponed until the resolution of these new concerns.

Summary

This section has reviewed approaches to ongoing assessment and placed them within ethical and evidence-based health care frameworks. In addition, decision-making options have been suggested based on observed results of training.

Glossary

classical conditioning: unconscious associative learning process that builds connections between paired stimuli that follow each other in time.

collateral informant: an individual who can provide detailed background information or more accurate information regarding deviant behavior.

ongoing assessment: the continuous evaluation of client progress.

qualitative anecdotal report: a narrative description of changes in the problem or goal by the client or collateral informant.

quantitative self-report: a client's numerical ratings of symptoms, subjective states, and behaviors.

self-monitoring: a client's ratings at assigned times in specified situations outside the neurofeedback session to increaseself-awareness.

SMART: a framework that prescribes goals that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

Test Yourself on ClassMarker

Click on the ClassMarker logo below to take a 10-question exam over this entire unit.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, which sounds do you prefer when you have succeeded during neurofeedback training? Which visual displays are more motivating for you?

References

Baer, L., & Blais, M. A. (2010). (Eds.). Handbook of clinical rating scales and assessment in psychiatry and mental health. Humana Press.

Bakker, D., & Rickard, N. (2018). Engagement in mobile phone app for self-monitoring of emotional wellbeing predicts changes in mental health: MoodPrism. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 432-442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.016

Beauchamp, T. L. (2003). Methods and principles in biomedical ethics. Journal of Medical Ethics, 29, 269-274. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.29.5.269

Beck, A. T. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory – II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Bovend’Eerdt, T., J. H., Botell, R. E., & Wade, D. T. (2009). Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: A practical guide. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23, 352-361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508101741

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.). Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall.

Gaultieri, T., & Johnson, L. G. (2006). Reliability and validity of a computerized neurocognitive test battery, CNS Vital Signs. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 21, 623-643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2006.05.007

Greenhalgh, J., & Meadows, K. (1999). Effectiveness of the use of patient-based measures of health in routine practice in improving the process and outcomes of patient care: A literature review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 5, 401-416. https://doi.org/0.1046/j.1365-2753.1999.00209.x

Hurn, J., Kneebone, I., & Cropley, M. (2006). Goal-setting as an outcome measure: A systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation, 20, 756-72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215506070793

Joshi, A., Kale, S., Chandel, S., & Pal, D. K. (2015). Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology, 7, 396-403.

Kamphaus, R., & Dever, B. V. (2016). Behavioral observations and assessment. In J. C. Norcross, G. R. VandenBos, D. K. Freedheim, & R. Krishnamurthy (Eds.), APA handbook of clinical psychology: Applications and methods (Vol. 3) (pp. 17-29). American Psychological Association.

Khazan, I. Z. (2013). Clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. Wiley-Blackwell.

Lau, M. A., Bishop, S. R., Segal, Z. V., Buis, T., Anderson, N. D., Carlson, L., Shapiro, S., & Carmody, J. (2006). Toronto Mindfulness Scale: Development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 1445-1467. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20326

Lovibond, S. H. & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety & Stress Scales (2nd Ed.). Psychology Foundation.

MacKillop, J., & Anderson, E. J. (2007). Further psychometric validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29, 289-293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-007-9045-1

Martin, G., & Pear, J. J. (2019). Behavior modification: What it is and how to do it (11th ed.). Routledge.

McMaster University Health Sciences Library. (2021, May 5). https://hslmcmaster.libguides.com/c.php?g=306765&p=2044668

Melbye, S., Kessing, L. V., Bardram, J. E., & Fourholt-Jepsen, M. (2020). Smartphone-base self-monitoring, treatment, and automatically generated data in children, adolescents, and young adults with psychiatric disorders: Systematic review. JMIR Mental Health, 7, e17453.

Melnyk, B. M., Fineout-Overholt, E., Stillwell, S. B., & Williamson, K. M. (2010). Evidence-based practice step by step. American Journal of Nursing, 110, 51-53. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000366056.06605.d2

Nicholson, A. A., Ros, T., Densmore, M., Frewen, P. A., Neufeld, R. W. J., Theberge, J., Jetly, R., & Lanius, R. A. (2020). Randomized, controlled trial of alpha-rhythm EEG neurofeedback in posttraumatic stress disorder: A preliminary investigation showing evidence of decreased PTSD symptoms and restored default mode and salience network connectivity using fMRI. NeuroImage: Clinical, 28, e102490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102490

Randolph, C., Tierney, M. C., Mohr, E., & Chase, T. N. (1998). The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): Preliminary clinical validity. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 20, 310–319. https://doi.org/10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823

Schwartz, M. S., & Andrasik, F. (Eds.). (2016). Biofeedback: A practitioner’s guide (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

Tan, G., Shaffer, F., Lyle, R., & Teo, I. (2016). Evidence-based practice in biofeedback & neurofeedback (3rd Ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Tate, R. (2010). Compendium of tests, scales and questionnaires: Practitioner's guide to measuring outcomes after acquired brain impairment. Psychology Press.

Thatcher, R. W. (2020). Handbook of quantitative EEG and EEG biofeedback (2nd Ed.). ANI Publishing.

Thompson, M., & Thompson, L. (2015). Neurofeedback book: An introduction to basic concepts in applied psychophysiology (2nd ed.). Association for Advancement of Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Weiner, G. (2017). Evolving as a neurotherapist: Integrating psychotherapy and neurofeedback. In T. Collura and J. A. Frederick (Eds.), Handbook clinical QEEG and neurotherapy (pp. 45-54). Routledge.

Wewers, M. E., & Lowe, N. K. (1990). Critical review of visual analogue scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Research in Nursing and Health, 13, 227-236. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770130405