Remote Neurofeedback Training

Advances in communications and computer technologies have made it possible for neurofeedback training to be more accessible so that clients and practitioners no longer must be in the same room for any length of time. The ability to provide neurofeedback at a distance can significantly increase accessibility to training. However, many issues must be addressed to ensure that such training-at-a-distance, or remote neurofeedback training, is effective and safe. Graphic © Versus.

This section provides an overview of remote neurofeedback training, considerations for its use, and ethical/legal issues.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit covers VIII. Treatment Implementation - E. Guidelines and Cautions for Remote Training

This unit covers What is Remote Training?, Research Review, Considerations with Remote Training, Typical Course of Training, and Summary and Conclusions.

Please click on the podcast icon below to hear a full-length lecture.

What is Remote Neurofeedback Training?

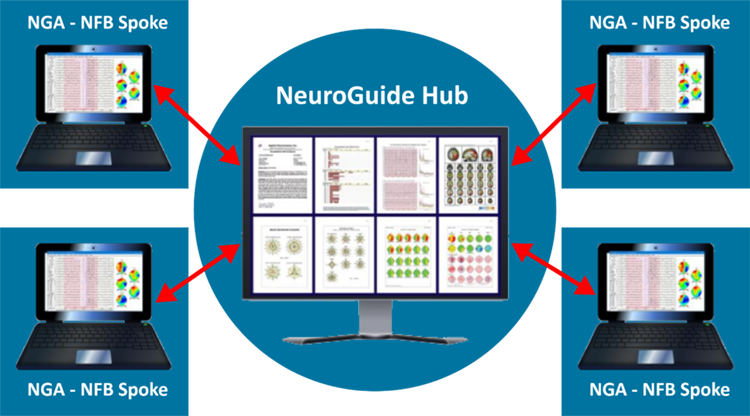

Remote neurofeedback training is an example of telehealth. It uses electronic and communication technologies to deliver neurofeedback to clients in a different location than the neurofeedback practitioner, with the geographic distance between practitioner and client being small (e.g., on the other side of town) or large (e.g., on a different continent). The practitioner may be virtually present in real-time, as when the practitioner uses screen sharing software to control neurofeedback software on the client’s computer and can see and interact verbally with the client in an immediate manner. Graphic NeuroGuide Hub and Spoke © Applied Neuroscience, Inc.

Alternatively, the practitioner may be present in real-time only by phone, with the client operating software that the practitioner has configured. In some cases of remote training, the practitioner may not be present at all during a training session but only follows up at intervals with the client to monitor progress and adjust software settings.

Signal acquisition and processing, feedback delivery, and data collection are typically performed on the client’s remote computer. Data storage may initially occur on the remote computer and then be uploaded or otherwise sent for inspection by the practitioner. The practitioner then may artifact the data, analyze various metrics, and graph results for subsequent review with the client. In addition to those normally used for in-clinic neurofeedback, hardware requirements may include high-speed internet, webcam, computer microphone, or phone line. Screen-sharing software is necessary for remote training in which the practitioner adjusts feedback settings and controls the duration of the session or its segments in real time.

Remote neurofeedback is typically preceded by all the usual preliminary steps of in-clinic neurofeedback, such as obtaining consent and assessment. After a positive response to in-clinic training, the client and practitioner discuss the advantages and disadvantages of remote training and how remote training could be made safe and successful. If it seems advantageous to proceed, an plan for training is agreed on that specifies who will be responsible for which training components, the purchase or rental of hardware and software, and costs. Training in electrode placement is then introduced. FocusCalm graphic © BrainMaster Technologies.

Watch a BrainMaster Technologies Inc. YouTube video on remote/home training.

Depending on the circumstances, it may also be possible to train the client in software use so that the practitioner is not required for this in real-time for remote sessions. Someone else may also be trained with the client's consent, particularly if the client is a child. Regardless of the level of practitioner involvement, the practitioner reviews session data for progress or problems, reviews results with the client, and makes necessary adjustments to the training protocol.

Research Review

A growing number of providers are offering remote neurofeedback training, with more than one training platform currently available (e.g., BrainMaster, Myndlift, Versus). Unfortunately, there are few published studies at this time. However, several peripheral biofeedback studies show the feasibility and efficacy of remote training and provide insights into relevant issues for remote neurofeedback.

Remote Biofeedback

Early reports of biofeedback provided with telehealth (Earles et al., 2001; Folen et al., 2001) used “off-the-shelf,” low-cost, low-bandwidth equipment, including telephone landlines. Commercially-available software to control the client’s computer was used, along with two standard telephone lines and a videophone. At the client’s location, an assistant attached electrodes and sensors then left once the practitioner established contact by videophone and between computers. Using low-bandwidth equipment, remote training was feasible and effective, as shown in a series of case studies. These authors also note that patient-provider rapport was satisfactory, although the audio quality was a concern.Because of the factors that might compromise remote training, it is important to compare it to in-clinic training to determine if measures are comparably reliable and valid and if the results are similar. Arena (2010), in his review of EMG biofeedback, reports on studies that found equivalence of in-clinic and remote training, with comparable durability of results. Stetz, Folen, Van Horn, Ruseborn, and Samuel (2013) comment that a younger generation of clients feels a significant interest in technology. This applies to military personnel for whom telehealth is becoming more common. The report by these authors describes the use of remote biofeedback and virtual reality applications for military clients. Although internet applications (apps) and teleconferencing can be used to support telehealth-based biofeedback, Stetz et al. (2013) also note that landlines (e.g., POTS or “Plain Old Telephone Service”) can be used for clinician-instructed biofeedback.

Additional successful examples of remote training include a study of remote EMG biofeedback by Golebowicz, Levanon, Palti, and Ratzon (2015). These authors also noted its value for decreasing cost and improving access to treatment. Their EMG study with computer operators also demonstrated how biofeedback can be used in a natural environment (Golebowicz et al., 2015). In this case, the researcher was virtually present during the biofeedback session that followed independent baseline data recording for each session.

Economides and colleagues (2020) showed remote heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback provided a significant increment in effectiveness to an app-based treatment for depression (Meru Health, 2021). These authors also note that it was possible to track client use of HRV objectively and that clients showed good levels of adherence to the training protocol.

Schaefer, Iskander, Tams, and Butz (2021) describe the use of biofeedback-assisted relaxation training (BART) for children. An existing BART protocol was modified for telehealth delivery, with the specific type of biofeedback depending on presenting concerns and relaxation strategy being taught. Rather than controlling the client’s biofeedback software remotely, clients used free-to-download apps for biofeedback with the clinician and client using a screen sharing program to coach the client in their home. Noting that the biofeedback apps have not been rigorously studied, the authors comment that clients could track physiologic changes during and between sessions.

Comparing their usual in-clinic BART to virtual BART, the authors report that the latter involved more time educating the clients and their parents on the informational component of treatment. However, it was important to find a level of information that was not excessive. Other issues described by the authors are client comfort with remote training, affordability of apps for home use, and limited research validation of available apps. Concerning the latter issue, poorly investigated apps present the risk of providing inaccurate feedback that may be ineffective, frustrating, or, at worst, present the risk of worsening the client’s condition.

Remote HRV biofeedback for adults has also been described recently by Davila et al. (2021). In this study, HRV was self-administered after an initial meeting with research staff. The biofeedback app integrated reminders, incentives, psychological scales, paced-breathing, HRV data collection and processing, and secure data sharing. In addition to online auto-editing of artifacts, laboratory-based offline artifact editing was conducted. Heart rate (HR) data were processed offline and found to validate online measures. The two HR data sets showed excellent agreement, indicating that the app collected and used reliable data for HRV biofeedback.

Remote Neurofeedback

Cotoos, De Valck, Arns, Breteler, and Cluydts (2010) report what appears to be the only published experimental study of remote neurofeedback. Randomizing a group of predominately sleep maintenance insomnia sufferers to remote training with either EMG biofeedback or neurofeedback, the authors found that only those subjects who received neurofeedback showed significant increase in total sleep time. Neurofeedback in this study focused on increasing SMR and inhibiting theta and high beta at Cz. Subjects were initially assessed in the author’s lab and then received hands-on training with electrode placement and the use of hardware and software. Training sessions were conducted at home, with the authors controlling the subjects’ computers via the internet. Participants in the neurofeedback group showed significantly better changes in objective and subjective sleep measures.An encouraging development is a proposed research protocol to study children with ADHD, comparing at-home neurofeedback training (i.e., SMR and Theta/Beta training) to long-acting methylphenidate (Bioulacet al., 2019). This study proposes to use pre-installed software on a tablet computer connected to a medical-grade EEG amplifier, with a clinician present during an initial session to train and supervise the subject and their parent. The software guides the child and parent through setup, calibration, and training, using an algorithm to remove eyeblink artifacts in real-time, and defining EEG frequency bands based on individualized alpha peak frequency. Training sessions start with a baseline assessment period followed by periods of feedback, with data automatically synchronized with a cloud server on a secure web portal. Three further sessions with the clinician are interspersed during at-home training.

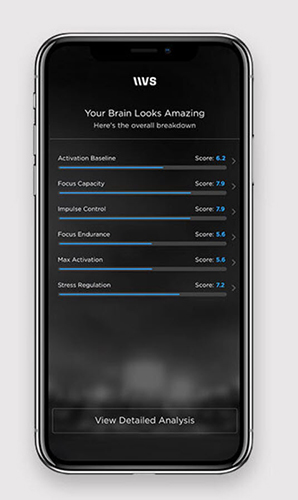

Despite the dearth of publications related to neurofeedback and remote training, manufacturers such as BrainMaster, Myndlift, and Versus have begun to offer hardware and software marketed for remote training, and several well-regarded practitioners have started to provide workshops on the topic. Versus NeuroPerformance Assessment graphic © Versus.

As seen in research with remote peripheral biofeedback, research needs to address several prominent issues with remote neurofeedback. Among these are its comparability to in-clinic training with respect to efficacy, reliability of data that have been collected remotely, and factors that may compromise or ensure a good outcome in remote training.

Considerations with Remote Training

Client-Related

Remote neurofeedback can increase the accessibility of training to a large number of clients in diverse locales. It may result in practitioners being able to serve more clients. Travel time and associated costs are reduced, and events that might lead to canceling an in-office session may be more easily accommodated by remote training. Remote training can also reduce exposure to infection and communicable diseases. Additionally, the outcome may be improved by delivering training in situations where change is most needed. Client preference may also be a deciding factor for training remotely. Graphic © Myndlift.

Watch a Myndlyft remote training instruction video on YouTube.

By contrast, many clients may prefer to train in a professional office. Limited skills and resources may preclude remote training at times. For example, a client’s physical or cognitive ability challenges can impede their at-home implementation of steps needed for remote training. Psychiatric disability of a significant degree can also make remote training risky. If the client is mentally vulnerable, it is important to arrange how and when to access supports ahead of time that can be accessed if needed. With the client’s consent, enlisting the assistance of a family member or friend or a health professional can overcome issues related to client ability. Social and material resources may pose real constraints in some situations when the client does not have others available to assist or afford what might be additional expenses of remote training.

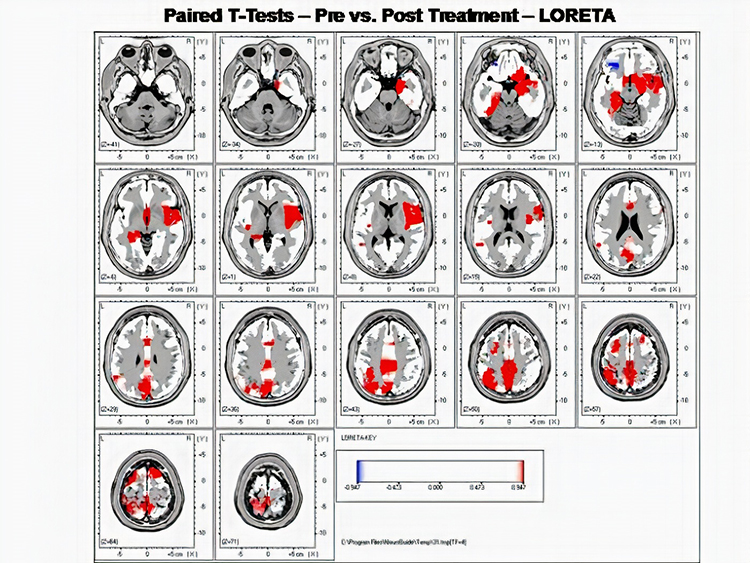

Additional considerations include having a place to train that is distraction-free and private.Secure and safe equipment storage under the client’s oversight is also important. Lack of stable internet service will prevent training remotely in cases where the practitioner must be present virtually. In cases where multiple electrode sites or LORETA neurofeedback is needed, remote training may not be possible. However, new developments are making even LORETA-based neurofeedback possible for those with sufficient resources and abilities (Brainworks, 2021).

Whether these issues apply or not will often be determined by the characteristics of the individual client. As much as possible, the practitioner should consider the factors comprising evidence-based health care. What are the details of the client’s condition and goals? What is the scientific evidence for or against remote training for the individual client’s needs? What access does the client have to the materials and internet services that are needed for remote training? What is the client’s preference for remote training?

Financial

In cases where hardware and software are rented to clients, written agreements are recommended to provide details related to cost, duration of use, liability for damage or theft, agreement to use the device with only the intended client, and requirement for immediate return if used inappropriately (Hammond et al., 2011).For clients who want to use insurance benefits to pay for remote neurofeedback, the client or practitioner will be wise to proactively investigate whether the insurance provider will reimburse for remote neurofeedback.

Ethical and Legal

Providers should also be familiar with and follow ethical codes and standards for neurofeedback (Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 2016; Biofeedback Certification International Alliance, 2016; International Society for Neurofeedback and Research, 2020). Furthermore, when providing remote training, those practitioners who are licensed health professionals must practice according to all statutes, regulations, standards, and codes of ethics that apply both in their location and in the location where the client is receiving remote training.

As articulated in diverse ethical and practice standards, providers should be competent in the methods they use (e.g., Hammond et al., 2011; Joint Task Force for the Development of Telepsychology Guidelines for Psychologists, 2013). This applies not only to the use of neurofeedback generally but also to the remote delivery of neurofeedback specifically. That is, remote neurofeedback involves knowledge and skill additional to conventional neurofeedback.

In his discussion of telehealth-delivered EMG biofeedback, Arena (2010) identifies several potential pitfalls that a practitioner should be aware of and address. These include privacy and confidentiality, use of support staff, licensing requirements for delivery of service where the client is located, malpractice insurance, insurance reimbursement requirements, and comfort level of the practitioner. Before providing remote training outside the jurisdiction for which they are licensed, health professionals should investigate regulations applying to the jurisdiction where their client resides.

Some clinicians may have inter-jurisdictional practice certificates that authorize cross-border neurofeedback, while temporary waivers may be available under special circumstances like the COVID-19 pandemic. Independent legal advice is recommended when there is ambiguity about providing cross-border services for conditions with a formal diagnosis. Providers should actively investigate whether their professional liability insurance covers their delivery of remote neurofeedback.

Security and privacy of phone and internet communications and data also need to be addressed before providing remote training. For example, confidentiality is less certain when sessions are conducted outside an office setting. Therefore, the provider and client should plan how to ensure privacy and avoid interruptions during training at home. Furthermore, apps may share client data. Various regulatory bodies provide guidelines for the management of privacy when providing telehealth which apply to remote neurofeedback (e.g., College of Psychologists of Ontario, 2021).

Providers are well-advised to become knowledgeable about how data is used by apps they recommend and discuss privacy issues in advance with their clients. Privacy issues may require steps to verify the client’s identity and anonymize data on the client’s computer.

Clients also need to be informed about the limited research regarding remote neurofeedback training for valid consent. As Schaefer et al. (2021) discussed above, some feedback software may have minimal research support and, therefore, pose the client's risks. Such risks should be reviewed with the client, and their consent obtained before training with such apps (cf. Cotoos et al., 2010).

To better ensure success and prevent harm, practitioners who provide remote training need to follow up regularly with their clients to review progress and resolve problems. A specific plan should be made for what the client can do if a difficulty does arise. Risks for adverse consequences have led some to state that remote training “should never be done when a licensed provider is not supervising it (p. 56, Hammond et al., 2011). Software that requires the clinician to change settings should be considered to reduce the risk of harm from misuse of neurofeedback.

Typical Course of Training

If the considerations above suggest that remote training is desirable, the practitioner will usually conduct an in-office assessment. Ideally, this is followed by a series of sessions in the practitioner’s office to ensure that the client responds well to training. The client and possibly a support person receive training to carry out the steps needed for remote training, and the necessary equipment and materials are acquired. Once remote training is begun, the practitioner regularly reviews data with the client to track progress and make decisions about the next steps. The client may be asked to return to the office for re-assessment and adjustment of training parameters.

Summary and Conclusions

This section has reviewed the expanding practice of remote neurofeedback training. Such training presents several advantages but may not be possible in some situations due to client characteristics and resources. Before providing remote training, ethical, legal, and financial issues must be carefully considered. Because remote training has received such limited research attention, caution is necessary when offering it as an option to clients. Nevertheless, in many circumstances, the salient issues can be addressed, and the value of remote training can be significant.

Glossary

alpha rhythm: 8-12-Hz activity that depends on the interaction between rhythmic burst firing by a subset of thalamocortical (TC) neurons linked by gap junctions and rhythmic inhibition by widely distributed reticular nucleus neurons. Researchers have correlated the alpha rhythm with relaxed wakefulness. Alpha is the dominant rhythm in adults and is located posteriorly. The alpha rhythm may be divided into alpha 1 (8-10 Hz) and alpha 2 (10-12 Hz).

alpha-theta training: a protocol to slow the EEG to the 6-9 Hz crossover region while maintaining alertness.

amplitude: the strength of the EMG signal measured in microvolts or picowatts.

application (app): a specialized program downloaded onto a mobile device.

beta rhythm: 12-38-Hz activity associated with arousal and attention generated by brainstem mesencephalic reticular stimulation that depolarizes neurons in both the thalamus and cortex. The beta rhythm can be divided into multiple ranges: beta 1 (12-15 Hz), beta 2 (15-18 Hz), beta 3 (18-25 Hz), and beta 4 (25-38 Hz).

biofeedback-assisted relaxation (BART): the integration of biofeedback with relaxation procedures like autogenic training and progressive relaxation.

confidentiality: a client's right to keep personal information private.

delta rhythm: 0.05-3-Hz oscillations generated by thalamocortical neurons during stage 3 sleep.

EEG activity: a single wave or series of waves.

EMG biofeedback: the display of muscle action potentials detected by an electromyograph to a client.

frequency: the number of complete cycles that an AC signal completes in a second, usually expressed in hertz.

gamma rhythm: EEG activity frequencies above 30 or 35 Hz. Frequencies from 25-70 Hz are called low gamma, while those above 70 Hz represent high gamma.

heart rate (HR): the number of beats per minute.

heart rate variability (HRV): the organized fluctuation of time intervals between successive heartbeats defined as interbeat intervals.

hertz (Hz): the unit of frequency measured in cycles per second.

in-clinic BART: BART administered in a provider's office.

LORETA neurofeedback: low resolution electromagnetic tomography (LORETA). Pascual-Marqui's (1994) mathematical inverse solution to identify the cortical sources of 19-electrode quantitative data acquired from the scalp.

power: amplitude squared and may be expressed as microvolts squared or picowatts/resistance.

real time: as events occur.

remote HRV biofeedback: the delivery of heart rate variability biofeedback to a client who is in another physical location than the provider.

sensorimotor rhythm (SMR): 13-15-Hz spindle-shaped sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) detected from the sensorimotor strip when individuals reduce attention to sensory input and reduce motor activity.

theta/beta ratio: the ratio between 4-7 Hz theta and 13-21 Hz beta, measured most typically along the midline and generally in the anterior midline near the 10-20 system location Fz.

theta rhythm: 4-8-Hz rhythms generated a cholinergic septohippocampal system that receives input from the ascending reticular formation and a noncholinergic system that originates in the entorhinal cortex, which corresponds to Brodmann areas 28 and 34 at the caudal region of the temporal lobe.

virtual BART: remotely self-administered BART.

Test Yourself on ClassMarker

Click on the ClassMarker logo below to take a 10-question exam over this entire unit.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, summarize the most critical precautions required by remote neurofeedback training.

References

Arena, J. G. (2010). Future directions in surface electromyography. Biofeedback, 38, 78-82. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-38.2.78

Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. (2016). Code of ethics. Retrieved October 31, 2021 from https://www.aapb.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3884

Biofeedback Certification International Alliance. (2016). Professional standards and ethical principles of biofeedback. https://bcia.memberclicks.net/assets/docs/ProfessionalStandardsAndEthicalPrinciplesof Biofeedback.pdf

Bioulac, S., Purper-Ouakil, D., Ros, T., Blasco-Fontecilla, H., Prats, M., Mayaud, L., & Brandeis, D. (2019). Personalized at-home neurofeedback compared with long-acting methylphenidate in an European non-inferiority randomized trial in children with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry, 19, 237-250. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2218-0

BrainMaster Technologies Inc. (2020). Telehealth (Remote/Home Training). Retrieved on November 7, 2021 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GFct171tAb0

BrainMaster Technologies Inc. Tele-health and remote training. Retrieved October 30, 2021 from https://brainmaster.com/tele-health/

College of Psychologists of Ontario. (2021). Virtual health care – enhanced privacy practices for services provided electronically. Retrieved October 30, 2021 from https://cpo.on.ca/virtual-health-care-enhanced-privacy-practices-for-services-provided-electronically-april-2021/

Brainworks. (2021). NeuroGuide hub and spoke training. Retrieved on November 7, 2021 from https://homeneurofeedback.com/fortherapists/

Cortoos, A., De Valck, E., Arns, M., Breteler, M. H. M., & Cluydts, R. (2010). An exploratory study on the effects of tele-neurofeedback and tele-biofeedback on objective and subjective sleep in patients with primary insomnia. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 35, 125-134. doi:10.1007/s10484-009-9117-z

Davila, M. I., Kizakevich, P. N., Eckhoff, R., Morgan, J., Meleth, S., Ramirez, D., Nirgan, T., Strange, L. B., Lane, M., Weimer, B., Lewis, A., Lewis, G. F., & Hourani, L. I. (2021). Use of mobile technology paired with heart rate monitor to remotely quantify behavioral health markers among military reservists and first responders. Military Medicine, 186, 17-24. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usaa395

Earles, J. E., Folen, R. A., & James, L. C. (2001). Biofeedback using telemedicine: Clinical applications and case illustrations. Behavioral Medicine, 27, 77-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964280109595774

Economides, M., Lehrer, P., Ranta, K., Nazander, A., Hilgert, O., Raevouri, A., Gevirtz, R., Khazan, I., & Forman-Hoffman, V. L. (2020). Feasibility and efficacy of the addition of heart rate variability biofeedback to a remote digital health intervention for depression. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 45, 75-86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-020-09458-z

Folen, R. A., James, L. C., Earles, J. E., & Andrasik, F. (2001). Biofeedback via telehealth: A new frontier for applied psychophysiology. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 26, 195-204. doi:10.1023/A:1011346103638

Golebowicz, M., Levanon, Y., Palti, R., & Ratzon, N. Z. (2015). Efficacty of a telerehabilitation intervention programme using biofeedback among computer operators. Ergonomics, 58, 791-802. https://doi.org/10.1080/01140139.2014.982210

Hammond, D. C., Bodenhamer-Davis, G., Gluck, G., Stokes, D., Harper, S. H., Trudeau, D., MacDonald, M., Lunt, J., & Kirk, L. (2011). Standards of practice for neurofeedback and neurotherapy: A position paper of the International Society for Neurofeedback and Research. Journal of Neurotherapy, 15, 54-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874208.2010.545760

International Society for Neurofeedback and Research. (2020). Code of ethics. Retrieved October 31, 2021 from https://isnr.org/interested-professionals/isnr-code-of-ethics

Joint Task Force for the Development of Telepsychology Guidelines for Psychologists. (2013). Guidelines for the practice of telepsychology. American Psychologist, 68, 791-800. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035001

Meru Health. (2021). Participant journey. Retrieved on November 7, 2021 from https://www.meruhealth.com/provider

Myndlift. Combining human care with home neurofeedback for better results. Retrieved October 30, 2021 from https://www.myndlift.com/

Schaefer, M., Iskander, J., Tams, S., & Butz, C. (2021). Offering biofeedback assisted relaxation training in a virtual world: Considerations and future directions. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 9, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpp0000391

Stetz, M. C., Folen, R. A., Van Horn, S., Ruseborn, D., & Samuel, K. M. (2013). Technology complementing military psychology programs and services in the Pacific Regional Medical Command. Psychological Services, 10, 283-285. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027896

Versus. Mobile brain sensing. Retrieved October 30, 2021 from https://getversus.com/