Patient/Client Assessment

Intake assessment is the foundation for diagnosing and selecting evidence-based interventions to treat symptoms or improve performance. Assessment should be multimethod, evidence-based, and culturally competent.

Multimethod assessment means using several assessment tools since no single tool can evaluate all relevant personality and behavioral domains. Depending on provider scope of practice and client presenting concerns, an intake may include a questionnaire, interview, objective personality tests, inventories, and behavioral assessment (Pomeranz, 2020).

Evidence-based assessment reflects the movement toward evidence-based treatments. Professionals should select measures that work and are psychometrically validated (e.g., reliability, validity, and clinical value). For example, the Beck Depression Inventory-II is widely used to help diagnose adult depression (Pomeranz, 2020).

Culturally competent assessment is sensitive to a culture's definition of normality and abnormality. Providers understand the relevant cultural norms of the populations they serve (Pomeranz, 2020). They avoid overpathologizing and labeling culturally normal behavior as abnormal, by viewing behaviors, cognitions, and feelings using the lens of the client's culture [rather than the provider's culture]. Dana (2005) has described ignorance or insensitivity to cultural norms as cultural malpractice.

Intake assessment has several purposes and methods. The use of these methods produces various quantitative and qualitative types of information. After collecting intake information, the practitioner integrates it with EEG findings and their clinical experience and knowledge of the science on which neurofeedback is based. The practitioner then shares a holistic summary with the client to arrive at a mutually agreed-upon common understanding of the presenting problem, a goal, and treatment options to decide whether to embark on a particular course of NFB training. Graphic © Motortion Films/Shutterstock.com.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit covers VI. Patient/Client Assessment - A. Intake Assessment and B. EEG Assessment.

This unit covers Intake Assessment, EEG Assessment for Neurofeedback, and their Integration.

Please click on the podcast icon below to hear a full-length lecture.

Intake Assessment

Purposes of Intake Assessment

The general purposes of intake assessment include gathering information, sharing information, and decision-making. In parallel to these, an essential purpose is to build a trusting working relationship that inspires confidence that neurofeedback will help. The results of the intake assessment describe the problem qualitatively and quantitatively and provide the baseline against which progress is measured. The information from intake contributes to constructing a formulation of the problem, that is, understanding why the problem occurs and what will alleviate it. This formulation sets the stage for planning neurofeedback training and helps the client give informed consent. In some clinical practice situations, another purpose may be to diagnose.Optimum Performance Assessment

Some practitioners focus their neurofeedback practice and biofeedback on what is variously known as peak performance, optimum performance, or simply performance training. Individuals who present for such training do not generally perceive themselves as having a "presenting problem" but primarily want to improve their performance in a sport, a musical career, academic achievement, or other endeavors. For such clients, assessment goals are quite similar to that of the clinical client. Identifying levels of function and differences from typical and other measures can be beneficial in guiding optimum performance training. The ultimate goal is performance enhancement. The desired outcomes are often measured by indicators specific to the client’s interests, such as improved scores, better ratings, improved musical opportunities, improved academic results, and the like.When working with optimum performance clients, the assessment may reveal a clinical issue, and sharing this information with the client can be a delicate task. Also, practitioners who are not licensed or registered health professionals may not even recognize such issues and may train the client in ways that may exacerbate such findings. Thus, it is vital for practitioners working with optimum performance clients to use comprehensive assessment techniques described in this section to ensure a thorough understanding of the client is obtained to avoid adverse outcomes.

Intake Assessment Methods

A neurofeedback practitioner's methods during their intake assessment are guided by the nature of the presenting problem, goal, practitioner skill set, and client's wishes. Some of the methods outlined below (e.g., questionnaires and rating scales) may be carried out before first meeting the client, whereas others (e.g., tests) may occur during or after an initial appointment.Preliminary Steps

After the client or referral source contacts the practitioner to request neurofeedback, the practitioner may use that initial contact to collect basic background information, either by phone or by sending a questionnaire. Suppose a background questionnaire is sent to the client. In that case, it may be accompanied by standardized or non-standardized rating scales or other questionnaires that the client is instructed to complete and bring with them to their first face-to-face meeting. Alternatively, background forms, questionnaires, and rating scales may be administered at the practitioner’s office before the intake interview. Some questionnaires and tests may even be completed online prior to the first face-to-face meeting. If the client is a child, then questionnaires and rating scales may be sent to the parent or some other significant person in the client’s life, such as a teacher. Consent forms can also be sent in advance.Introduction and Consent

For the first face-to-face meeting, the provider needs to introduce themself and outline the methods involved in the intake assessment. This enables the client to participate to the best of their ability. An essential part of intake assessment occurs at the outset with a review of confidentiality and the limits of confidentiality before verifying that the client then wants to proceed. Consent should be documented.Throughout the intake assessment, the provider should use active listening skills and other supportive communication skills to build a working relationship with the client (Silverman et al., 2013). The use of these skills fosters trust and credibility and puts the client at ease to provide the best possible information to the practitioner.

If identifying information details are not fully collected before the intake interview, the practitioner can ask the client directly for particulars such as name, birthdate, address, phone number, and information related to billing and whom to contact in the case of an emergency.

Problem Description

Following this opening introduction, information needs to be gathered about the client’s presenting problem and goal (Schwartz, 2016). This may begin with a simple open-ended question, allowing the client time to respond. A great deal can be learned in these first few minutes of an interview by listening to clients present their concerns and goals unimpeded and in their own words. The practitioner can then better follow up with specific questions to understand the problem more thoroughly.Inquiry about the details of the presenting problem helps to construct a description or definition of the client’s primary concern. The problem may be an excess or a deficit and may relate mainly to the client’s emotional, thinking, or somatic functioning. The problem definition may include information related to frequency, intensity, and duration of occasions when the problem occurs.

Context matters so that motivational conditions, antecedents, and consequences of the behavior may be helpful to describe. When the problem first had its onset and surrounding circumstances may be relevant to the assessment. How the symptom has waxed and waned over time and factors that worsen or relieve it can be valuable pieces of information. What the client and others have attempted insofar as changing the problem is also essential, and whether the client is receiving any ongoing treatment. How the issue affects or limits the client helps to illustrate the severity of the concern.

The provider and client use this information to define a goal for training, for example, to decrease a problem that represents an excess of some sort or to increase function that is deficient in some respect. Of course, the results of EEG assessment are part of goal-setting.

Personal and Family History

Information about the larger context of the problem is essential (Stucky & Bush, 2017). Categories of such information are referred to as personal and family history. The client’s personal history includes medication, drug and alcohol use, diet and exercise, sleep, medical issues, psychiatric problems, family and social relationships, education, work experiences, legal matters, and military service. In several of these categories, it is helpful to inquire about treatment, training, and unique accommodations that the client may have had. The client’s typical level of function is beneficial to elicit. This may be done for personal care, completion of domestic chores, socialization, community access, education or work, and leisure and recreation.Family history contains relevant information about parents, siblings, and possibly other family members. Although topics noted for personal history can serve as areas of inquiry about family members, it is usually the case that collection of family history information is more focused and limited to items that are particularly relevant to the client’s presenting problem and goals (e.g., medical and psychiatric concerns).

Diagnostic Interviewing

For some registered/licensed health professionals, the intake information may contribute to making a diagnosis. Several semi-structured interview formats have been developed to elicit information for making a psychiatric differential diagnosis. Medical practitioners may also make a diagnosis based on an interview, physical examination, and test findings.Barriers, Strengths, and Client Perspective

In addition to describing the problem and its course and outlining likely contributing factors, the intake interview also examines possible personal, social, and material resources available to aid in problem resolution. These may include, for example, motivation, encouraging family members, and access to transportation or the internet. Barriers may similarly be personal, social, or material. Additionally, the client’s view of the causes of the problem and what it will take to remedy it are valuable points of inquiry.Behavioral Observation and Mental Status Examination

The client’s way of moving and speaking during the intake interview can be very informative in arriving at a description of the problem and goal and understanding the client.In some clinical situations, the practitioners may administer more formal questions to understand the client’s emotional and cognitive condition. A mental status exam (Sadock et al., 2017) provides a format for observation and briefly assessing mental functioning. Topics include speech, emotion and affect, thought content and form, perceptual disturbances, cognition, reasoning, insight, and judgment.

Collateral Interview

Especially with clients who may be unable to provide reliable information, an interview with a close relative or someone with significant direct experience with the client is beneficial. This information may fill in gaps left from the client interview and add new information. Inconsistencies between the client and collateral information may also suggest potential client deficits.Reports

Several types of reports may be relevant to intake assessment. These include medical and psychiatric reports and academic and vocational information. If the client has been referred by another professional, a report from that professional can be illuminating. Although such a report may be written, a phone conversation with a referral source can be very informative. Such a conversation can help to clarify the reason for referral, attainable goals, and likely predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating causes for the problem. The client should be asked for their consent to request reports that are likely to be helpful.Questionnaires and Rating Scales

Questionnaires often consist of checklists and places for clients to respond in their own words. This allows the client to provide basic background information, problem description, and personal history. Items may be open-ended and qualitative (e.g., describe your concern), closed-ended (e.g., have you ever had a seizure), or multiple-choice (e.g., check each type of caffeinated beverage you drink).Rating scales help to quantify a problem (Baer & Blais, 2010). They may be standardized and have norms that compare the client’s results with those of groups matched to the client, for example, based on age or education. Alternatively, they may be constructed with items the provider has developed for use in their specific setting and may or may not have norms developed in the practitioner’s office.

Both questionnaires and rating scales can collect information about cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physical symptoms or problems (Psychology Tools, n.d.). They can also gather information about the functional consequences of symptoms: the effect that they have on practical, real-world ability and social adjustment (Űstűn et al., 2010).

Information from questionnaires helps describe the presenting problem in qualitative terms and gives the provider insight into how the client sees the problem. Rating scales, together with EEG results, provide quantification of the problem and serve as a baseline for recognizing progress or the lack of progress once training has begun.

As noted above, questionnaires and rating scales can be sent to the client in advance of the intake interview or completed immediately before or after the interview. Collecting information by questionnaire can make the intake interview much more efficient and help focus the interview on the most salient aspects of the client’s concerns.

Whereas some questionnaires and rating scales are proprietary, others are available in the public domain. Informant versions of some questionnaires are also available.

Cognitive Tests

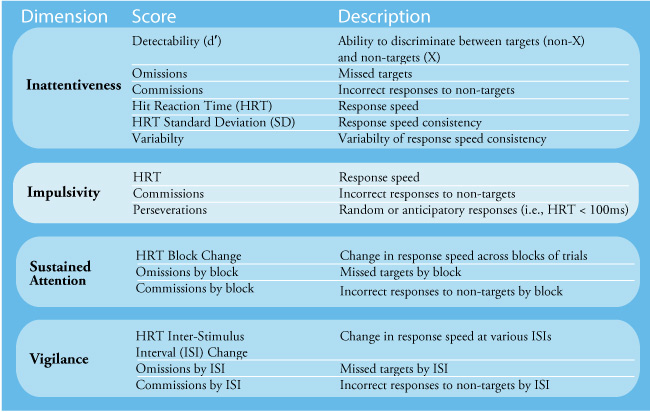

Not only in research settings but frequently in clinics, practitioners will often administer tests of thinking and cognition (Lezak et al., 2012). Depending on the goals of neurofeedback for a particular client, domains assessed may include one or more of the following: attention, memory, language, visual-spatial perception and construction, and executive functioning. Intellectual functioning, academic performance, sensorimotor ability, and effort/performance validity may also be assessed. For example, deficient attention may be why the client requested neurofeedback. A continuous performance test such as the Conners Continuous Performance Test (2014) may be used to assess sustained attention and distractibility. Graphic © Pearson.

Or, improved academic performance may be the client’s goal, with the practitioner using an educational screening instrument such as the Wide Range Achievement Test (Wilkinson & Robertson, 2017). Graphic © Pearson.

Alternatively, a measure of intelligence (e.g., Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-IV; Wechsler, 2008) or collection of executive function or cognitive self-regulation measures may be of interest (e.g., Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System; Delis et al., 2001). Cognitive test batteries have several tests that assess representative domains of cognition and may include, for example, measures of aspects of attention, memory, and executive function (e.g., CNS Vital Signs; Gaultieri & Johnson, 2006). Graphic © Pearson.

Tests should be selected critically, considering standardization methods, normative groups, reliability, and validity. Many tests are available only to professionally qualified health practitioners, while many other tests can be purchased with fewer requirements. While many tests use paper and pencil or objects to manipulate, additional tests are administered by computer.

Those tests that use paper and pencil, or manipulable objects, usually require administration by a well-trained individual. However, those tests administered by computer reduce the cost of clinician time, both for administration and scoring. Nevertheless, a practitioner should interpret results with appropriate professional background for the results to have validity and value for the client.

Psychophysiological Assessment

Some practitioners integrate neurofeedback with other treatment modalities they are trained to offer. These may include counseling or psychotherapy, medication management, audiovisual entrainment, brain stimulation, or peripheral biofeedback. For the latter, psychophysiological assessment can help identify which physical system to treat and provides a baseline for judging progress (Khazan, 2013; Peper et al., 2008).o The quantitative data collected during intake assessment, whether from rating scales, questionnaires, cognitive tests, IQ and academic measures, or psychophysiological analysis can serve as an important baseline reference point for evaluation the effects of training and for decision-making during the course of neurofeedback.

EEG Assessment for Neurofeedback

Depending on the presenting problem and goal, and practitioner training, initial EEG assessment may be more or less elaborate. The complexity of the initial evaluation also relates to the number of electrode sites used, which, in typical neurofeedback practices, ranges from 1 to 19.

In addition to examining the analog waveform of the EEG signal, several variables can be evaluated quantitatively. Data from single sites may be represented by absolute or standardized (i.e., z-scores) values of amplitude or power in single-hertz bins or frequency bands that span a range of hertz values. Power values may also be given in ratios that compare bands.

Dr. Ronald Swatzyna has generously permitted the authors to share the Houston Neuroscience Brain Center's client orientation video.

If the practitioner uses more than one electrode for assessment, different ratios can be calculated by comparing left and right prefrontal sites or anterior and posterior sites. Sites can also be compared with variables such as coherence and phase. In cases when 19-channel records are obtained, various LORETA analyses can be performed, revealing EEG activity at Brodmann areas that are not limited to the cortical convexity. LORETA analyses enable the practitioner to examine the details of functioning in networks such as the default mode, salience, and attention networks. Normative databases are used with such analyses to compare the client’s EEG function to a healthy age-matched reference group.

Both qualitative and quantitative EEG findings are interpreted to generate hypotheses that are integrated with the information from the other components of the intake assessment.

Quantitative approaches to EEG assessment include those described by Collura (2014), Demos (2019), Kaiser (2008), Soutar and Longo (2011), Swingle (2015), Thatcher (2020), Thompson and Thompson (2015), and Van Deusen (Ribas, Ribas, & Martins, 2016).

Integration of Intake and EEG Assessments

The intake assessment concludes with several necessary steps. The practitioner summarizes the critical information that has been gathered from the various assessment methods and validates this by asking the client if there is anything to correct or add. The practitioner then integrates the information with EEG findings and also with their scientific and clinical knowledge. This provides a formulation or an understanding of the problem for the client to consider. The client is then invited to share their thoughts and to ask questions.

Together with this understanding of the problem, the provider shares her or his perspective on how neurofeedback training protocols may be of use, together with the degree of scientific evidence that supports them. Details about recommended neurofeedback training are also helpful to provide. These can include a description of neurofeedback equipment, what the provider will do, what the client will do, and what the client should expect during training. Possible side-effects and how they will be addressed can be reviewed. The likely duration and costs of training should be reviewed, along with how and when progress will be monitored. Possible outcomes and durability of success can also be described.

Alternatives to neurofeedback can be reviewed, including no intervention or behavioral and lifestyle interventions. In some cases, the information collected during intake may suggest that neurofeedback is unlikely to be helpful at present. The provider considers their expertise and shares it with the client. In light of the characterization of the presenting problem, the scientific evidence, and the provider's expertise, the provider and client then consider what resources are available for treatment and review the client’s preferences. This comprehensive discussion enables the client to give well-informed consent for neurofeedback.

The provider then may conclude the assessment by determining if it is advisable to send a report and, if so, to obtain consent to do so. A time for a subsequent appointment is made. If relevant, the practitioner summarizes what the client and provider will do in the interim (e.g., self-monitoring of symptoms by the client).

Summary

The practitioner uses various methods during the intake assessment and organizes the resulting information into a summary that has utility for describing and understanding the client’s problems and goals and planning subsequent steps, including neurofeedback training. Data collected with various methods help the client make a confident and well-informed decision about whether to proceed with neurofeedback training.

Glossary

Brodmann areas: 47 numbered cytoarchitectural zones of the cerebral cortex based on Nissl staining.

collateral information: reports from family members, friends, and healthcare professionals.

cortical convexity: the curve of the cerebrum immediately beneath the skull.

cultural malpractice: assessment and treatment decisions biased by cultural insensitivity and ethnocentrism.

culturally-competent assessment: assessment that is informed by and sensitive to the meaning of actions, beliefs, and feelings within a client's culture.

evidence-based assessment: client evaluation using instruments that are reliable, valid, and possess clinical utility.

low resolution electromagnetic tomography (LORETA): Pascual-Marqui's (1994) mathematical inverse solution to identify the cortical sources of 19-electrode quantitative data acquired from the scalp.

multimethod assessment: evaluation using multiple assessment tools.

overpathologizing: labeling culturally normal behavior as abnormal.

z-score training: neurofeedback protocol that reinforces in real-time closer approximations of client EEG values to those in a normative database.

Test Yourself on ClassMarker

Click on the ClassMarker logo below to take a 10-question exam over this entire unit.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, summarize the potential benefits of collateral interviews. What can psychophysiological assessment contribute to client evaluation?

References

Bear, L., & Blais, M. A. (Eds.) (2010). Handbook of clinical rating scales and assessment in psychiatry and mental health. Springer Nature.

Collura, T. F. (2014). Technical foundations of neurofeedback. Routledge.

Conners, C. K. (2014). Conners Continuous Performance Test (3rd ed.). Multi-Health Systems.

Dana, R. H. (2005). Multicultural assessment: Principles, applications, and examples. Erlbaum.

Delis, D. C., Kaplan, E. F., & Kramer, J. H. (2001). Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System. The Psychological Corporation.

Demos, J. N. (2019). Getting started with EEG neurofeedback (2nd ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Gaultieri, T., & Johnson, L. G. (2006). Reliability and validity of a computerized neurocognitive test battery, CNS Vital Signs. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 21, 623-643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2006.05.007

Kaiser, D. A. (2008). Functional connectivity and aging: Comodulation and coherence differences. Journal of Neurotherapy, 12, 123-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874200802398790

Khazan, I. Z. (2013). Clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. Wiley-Blackwell.

Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B., Bigler, E. D., & Tranel, D. (2012). Neuropsychological assessment (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Peper, E., Tylova, H., Gibney, K., H., Harvey, R., & Combatalade, D. (2008). Biofeedback mastery: An experiential teaching and self-training manual. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Pomeranz, A. M. (2020). Clinical psychology: Science, practice, and diversity (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Psychology Tools. (n.d.). Psychological assessment tools for mental health. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www.psychologytools.com/download-scales-and-measures/

Ribas, V. R., Ribas, R. de M. G., & Martins, H. A. de L. (2016). The Learning curve in neurofeedback of Peter Van Deusen: A review article. Dementia and Neuropsychologia, 10, 98-103. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-5764-2016DN1002005

Sadock, B. J., Sadock, V. A., & Ruiz, P. (2017). Kaplan and Sadock's concise textbook of clinical psychiatry (4th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Schwartz, M. S. (2016). Intake and preparation for intervention. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.), Biofeedback: A practitioner’s guide (4th ed.) (pp. 217-232). Guilford Press.

Silverman, J., Kurtz, S., & Draper, J. (2013). Skills for communicating with patients (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

Soutar, R., & Longo, R. (2022). Doing neurofeedback: An introduction (2nd ed.). ISNR Research Foundation.

Stucky, J., & Bush, S. S. (2017). Neuropsychology fact-finding casebook: A training resource. Oxford University Press.

Swingle, P. G. (2015). Adding neurofeedback to your practice: Clinician’s guide to ClinicalQ, neurofeedback, and braindriving. Springer.

Thatcher, R. W. (2020). Handbook of quantitative EEG and EEG biofeedback (2nd ed.). ANI Publishing.

Thompson, M., & Thompson, L. (2015). Neurofeedback book: An introduction to basic concepts in applied psychophysiology (2nd ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.