Steps in Protocol Development

Overview

This section presents a framework for deciding where to place electrodes for training and which EEG variable or variables to train. However, this framework is only intended to serve as a starting point for making clinical decisions. Practitioners should be prepared to account for their reasoning when selecting protocols.

We start by inviting professionals to consider whether challenging cases have functional causes requiring extensive blood and urine testing. Blood sample tube graphic © angellodeco/Shutterstock.com.

Dr. Ron Swatzyna and colleagues (2024) encourage clinicians to think outside DSM-V diagnoses and collaborate with neurologists and functional and integrative medicine professionals to identify and address the underlying causes of client complaints for clients referred for biofeedback or neurofeedback.

What are "red flags" that should trigger a functional or integrative medicine consult? First, the symptoms (e.g., hyperactivity, tics) are new or have worsened exponentially (Swatzyna, 2024).

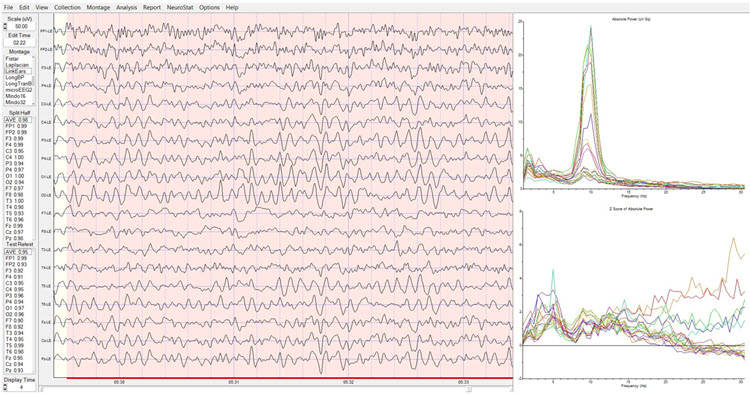

Second, their EEG reveals abnormal amplitude and peak frequency values. For example, is a 10-year-old child's amplitude and peak frequency age-appropriate? A low-amplitude 6.5-Hz peak frequency in a 10-year-old should be investigated. A series of EEGs can provide a more complete picture of your client's clinical trajectory (Swatzyna, 2024).

Third, a neurologist confirms the presence of biomarkers in the raw EEG like focal slowing (FS), spindling excessive beta (SEB), encephalopathy (EN), and isolated epileptiform discharges (IEDs), which may suggest physiological processes like neuroinflammation. Collaboration with a board-certified neurologist can increase the accuracy of your raw EEG interpretation and enhance your credibility with your client's physician.

The use of EEG biomarker identification represents a positive step toward personalized medicine. By directly testing the organ being treated, practitioners can gain a deeper understanding of the underlying brain activity and create treatment plans tailored to the specific needs of each patient. (Swatzyna et al., 2024, p. 9)When red flags signal possible environmental (e.g., lead or mold exposure) or gut-brain causes, you can recommend that your client consult with a functional or integrative medicine professional in your area. They will decide which tests are needed based on your patient's symptoms, medical history, and EEG findings.

You should not begin biofeedback and neurofeedback until the suspected causes are ruled out or addressed. This could mean waiting several months for treatment to repair the gut wall when dysbiosis occurs or for a mold detox protocol to reduce mycotoxin levels.

This paradigm shift might feel overwhelming to biofeedback and neurofeedback providers. But it doesn't have to be if you "stay in your lane" and collaborate with functional and integrative physicians. They will decide which tests are needed to investigate possible environmental and gut-brain causes. They will explain their findings, and recommend evidence-based treatments (Swatzyna, 2024). All this paradigm shift requires is that you continue to do what you do best, identify these red flags, and make functional and integrative medicine referrals when needed.

Clinical Examples

A diverse group of medical professionals contributed the following examples. In each case, treating the DSM-V diagnosis with medication and neurofeedback would have failed to correct the underlying functional cause.Case Example 1: Mold Exposure and Cognitive Decline

A 40-year-old woman presented with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline. Traditional treatment with antidepressants provided only partial relief. A functional medicine assessment revealed a history of significant mold exposure in her home. Testing confirmed the presence of mycotoxins in her body, indicating mold toxicity. Treatment involved mold remediation in her home, detoxification protocols to eliminate mycotoxins, and support for her immune system and gut health. As her body cleared the toxins, her psychological symptoms improved dramatically, and her cognitive function returned to normal. This case demonstrates that addressing the underlying cause—mold toxicity—was essential for effective treatment.

Case Example 2: Glyphosate Exposure and ADHD

A 10-year-old boy was diagnosed with ADHD and prescribed stimulant medication. While the medication helped manage his symptoms, it caused side effects such as insomnia and decreased appetite. A functional medicine practitioner explored environmental factors and discovered that the family lived near agricultural fields regularly sprayed with glyphosate. Testing revealed high levels of glyphosate in the boy's system. The treatment plan included dietary changes to support detoxification, supplementation with nutrients to support brain health, and measures to reduce glyphosate exposure. As his glyphosate levels decreased, his ADHD symptoms improved, and he was able to reduce his reliance on stimulant medication.

Case Example 3: Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (CIRS)

A 35-year-old man experienced severe fatigue, brain fog, and mood swings. Despite seeing multiple specialists and trying various medications, his symptoms persisted. A functional medicine assessment identified chronic inflammatory response syndrome (CIRS) caused by exposure to biotoxins, likely from water-damaged buildings. Advanced testing confirmed elevated inflammatory markers and biotoxin levels. The treatment plan involved detoxification protocols, binders to remove biotoxins, and support for his immune and nervous systems. Addressing the biotoxin exposure and inflammation led to significant improvements in his energy levels, cognitive function, and mood, highlighting the importance of identifying and treating the root cause.

Case Example 4: Lyme Disease and Psychiatric Symptoms

A 28-year-old woman presented with severe anxiety, depression, and panic attacks. Traditional psychiatric treatments, including antidepressants and anxiolytics, provided minimal relief. A functional medicine practitioner considered the possibility of underlying infections and ordered comprehensive testing, which revealed Lyme disease and co-infections. The treatment plan included antimicrobial therapies to address the infections, immune support, and interventions to reduce inflammation. As the infections were brought under control, her psychiatric symptoms began to resolve, demonstrating the critical need to address underlying medical conditions rather than just treating the symptoms.

Case Example 5: Addison's Disease and Depression

A 45-year-old man was experiencing severe fatigue, weight loss, and depression. Standard treatments for depression, including antidepressants and therapy, had little effect. A functional medicine practitioner conducted a thorough assessment and discovered that the patient had Addison's disease, a condition where the adrenal glands do not produce enough cortisol. This condition can lead to significant psychological symptoms. Treatment involved hormone replacement therapy to address the cortisol deficiency and supportive measures to strengthen the patient's overall health. Once Addison's disease was managed, the patient's depression and fatigue improved markedly, underscoring the importance of diagnosing and treating the underlying medical condition.

Case Example 6: Environmental Toxins and New OCD Symptoms

A 22-year-old woman developed new-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms, including severe anxiety and compulsive behaviors. Traditional psychiatric medications provided minimal relief. A functional medicine approach was taken, and a detailed environmental assessment revealed that she had been exposed to high levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in her workplace. Testing confirmed elevated levels of these toxins in her body. The treatment plan included reducing her exposure to VOCs, detoxification protocols, and nutritional support to enhance her body's ability to eliminate toxins. As her toxin levels decreased, her OCD symptoms and anxiety significantly improved.

Case Example 7: Tics and Heavy Metal Toxicity

A 15-year-old boy developed motor tics and was diagnosed with a tic disorder. Traditional treatments, including behavioral therapy and medications, were only partially effective. A functional medicine practitioner conducted comprehensive testing and discovered high levels of heavy metals, particularly lead, in the boy's system. These heavy metals were likely contributing to his neurological symptoms. The treatment plan included chelation therapy to remove the heavy metals, dietary modifications to support detoxification, and supplements to restore nutritional balance. As the heavy metal levels decreased, the boy's tics reduced in frequency and severity, illustrating the importance of addressing environmental toxins.

Case Example 8: PANS/PANDAS and Psychiatric Symptoms

A 12-year-old girl suddenly developed severe anxiety, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and mood swings. Traditional psychiatric treatments were ineffective. A functional medicine practitioner suspected Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) or Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS). Dr. Melissa Jones expects these terms to be subsumed by autoimmune encephalitis. Comprehensive testing confirmed a recent streptococcal infection and elevated markers of autoimmune activity. The treatment plan included antibiotics to address the infection, anti-inflammatory therapies, and immune-modulating treatments. As the underlying infection and inflammation were treated, the girl's psychiatric symptoms began to resolve, highlighting the need for a comprehensive approach to diagnosing and treating psychiatric symptoms with a possible autoimmune or infectious basis.

Case Example 9: Autism and Gut Health

A 6-year-old boy was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and exhibited severe gastrointestinal issues, including chronic diarrhea and abdominal pain. Traditional therapies for autism focused on behavioral interventions, but they did not address his physical discomfort. A functional medicine practitioner thoroughly evaluated and found significant dysbiosis in the boy's gut microbiome. Treatment included a specialized diet to eliminate food sensitivities, probiotics to restore healthy gut flora and anti-inflammatory supplements. As his gut health improved, there were notable enhancements in his mood, behavior, and communication skills, demonstrating the profound impact of addressing underlying physical conditions in managing ASD symptoms.

Case Example 10: Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Nutrient Deficiencies

An 8-year-old girl was diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and was struggling with severe temper tantrums, defiance, and aggression. Traditional behavioral therapy provided limited success. A functional medicine assessment revealed multiple nutrient deficiencies, including low levels of zinc, magnesium, and vitamin D. The treatment plan included dietary changes to ensure a nutrient-rich diet and targeted supplementation. Over time, as her nutrient levels normalized, her behavior improved significantly, highlighting the importance of addressing nutritional imbalances in managing psychological and behavioral disorders.

Case Example 11: Strep Infection Leading to Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy

A 7-year-old girl developed severe neuropsychiatric symptoms, including sudden onset of obsessive-compulsive behaviors and tics. After several weeks of ineffective treatment with standard psychiatric medications, a functional medicine practitioner was consulted. The comprehensive assessment included a detailed medical history, which revealed a recent bout of strep throat. Blood tests showed elevated anti-streptolysin O (ASO) titers, indicating a recent streptococcal infection. Despite initial antibiotic treatment, her symptoms persisted, and recurrent strep infections were suspected. To address the root cause, the functional medicine practitioner recommended a tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy to remove the chronic infection source. Post-surgery, the patient showed significant improvement in her neuropsychiatric symptoms, highlighting the importance of addressing underlying infections in cases of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections.

Case Example 12: UTI-Related Dementia Symptoms in an Elderly Patient

An 82-year-old man was experiencing rapid cognitive decline and behavioral changes, initially diagnosed as dementia by his primary care physician. His symptoms included confusion, agitation, and memory loss, which severely affected his quality of life. A functional medicine practitioner was consulted for a second opinion. Upon a thorough evaluation, including laboratory tests, a urinary tract infection (UTI) was identified as the underlying cause of his symptoms. UTIs can lead to delirium and dementia-like symptoms in elderly patients due to inflammation and systemic infection. The patient was treated with appropriate antibiotics to eradicate the infection, and his cognitive function improved markedly. This case underscores the necessity of considering infections and other reversible conditions in the differential diagnosis of dementia in elderly patients.

A Neurofeedback Decision-Making Framework

After functional causes have been identified and treated or ruled out, neurofeedback should be started. The framework described in this unit can provide the backdrop against which formulation and decision-making for neurofeedback take place.John S. Anderson discusses the process of developing evidence-based treatment protocols. Video © J. S. Anderson.

The model used in this section is evidence-based, in the sense that the evidence from research studies and clinical experience is used to select training protocols, along with the evidence of neuroscience and brain-behavior relationships. We are indebted to the work of Michael and Lynda Thompson, who have advocated that clinical outcome research and neuroscience should inform neurofeedback protocol development (e.g., Thompson & Thompson, 2015).

This section is also consistent with John Anderson’s NewQ assessment method. Abbreviated Q assessments can provide useful information about the client, help validate and explain client symptoms and assist with training protocol selection. Video © J. S. Anderson.

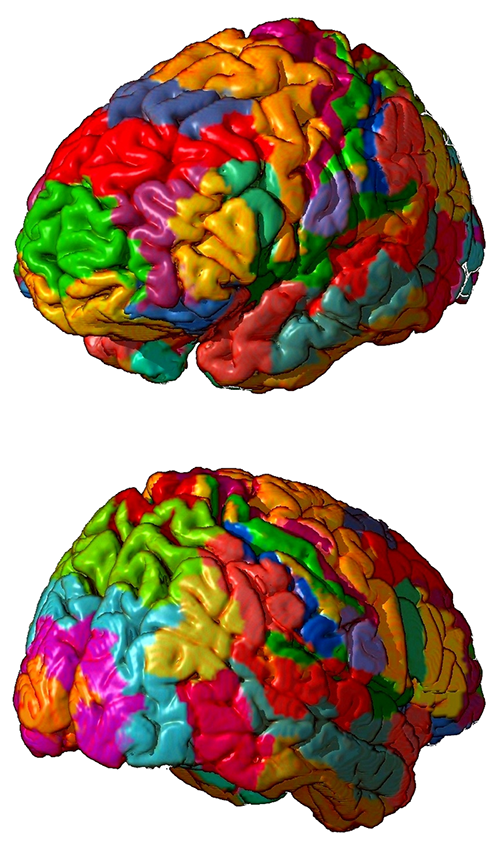

Basic features of neurofeedback training protocols are electrode location, EEG frequency to be trained, EEG parameters (e.g., amplitude, amplitude ratios, connectivity measures, symmetry, peak frequency), and whether the EEG parameter for a frequency is trained up or down. When using 19-channel LORETA training, additional features to be considered for neurofeedback training protocols are cortical structures, Brodmann Areas, and brain networks. Graphic © Zayabich/Shutterstock.com.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit covers VII. Developing Treatment Protocols - B. Steps in protocol development and treatment planning using one or more of the treatment models.

This unit covers Factors to Consider, Decision-Making and Ongoing Problem-Solving and Flowchart.

Please click on the podcast icon below to hear a full-length lecture.

Factors To Consider

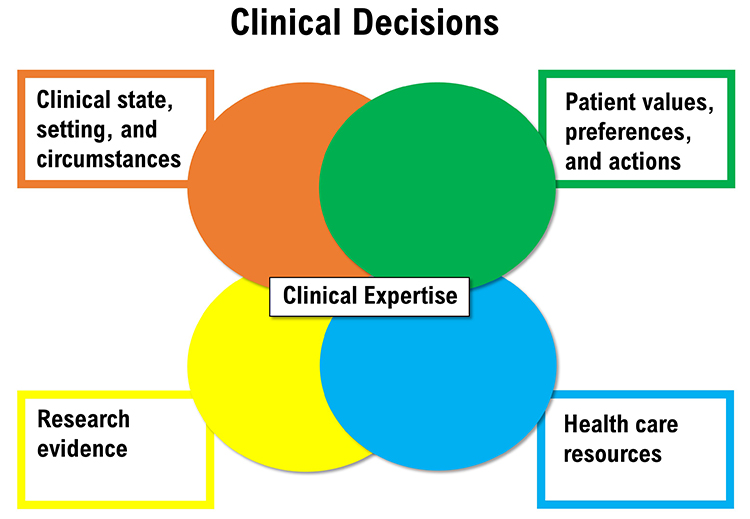

Several factors are relevant to protocol selection, where to place electrodes, and which EEG variables to increase or decrease. These factors include the client’s condition, research findings, practitioner expertise, available resources, environmental context, and client values and preferences.

Client Condition and Goals

Based on the initial assessment, the practitioner will know what the client’s goals are, that is, whether there are symptoms to decrease or abilities to increase. Also contributing to knowledge about the client’s condition are their personal and health histories and test findings. As described in the Assessment section of Neurofeedback Tutor: Assessment and Training, information relevant to this factor comes from various sources, including self-report, direct behavioral observation, professional reports, cognitive tests, questionnaires, and reports from significant others (e.g., parent, teacher, spouse). Results from EEG assessment are central to the client’s condition, and peripheral psychophysiological assessment findings are also considered in many cases.Training goals may be at one or more levels of analysis. The first of these levels is biological and helps identify the site(s) at which to train and the EEG variable or variables to train. For example, the assessment finding of excess posterior beta activity in the context of a client's goal of anxiety reduction may suggest electrode placement at P4.

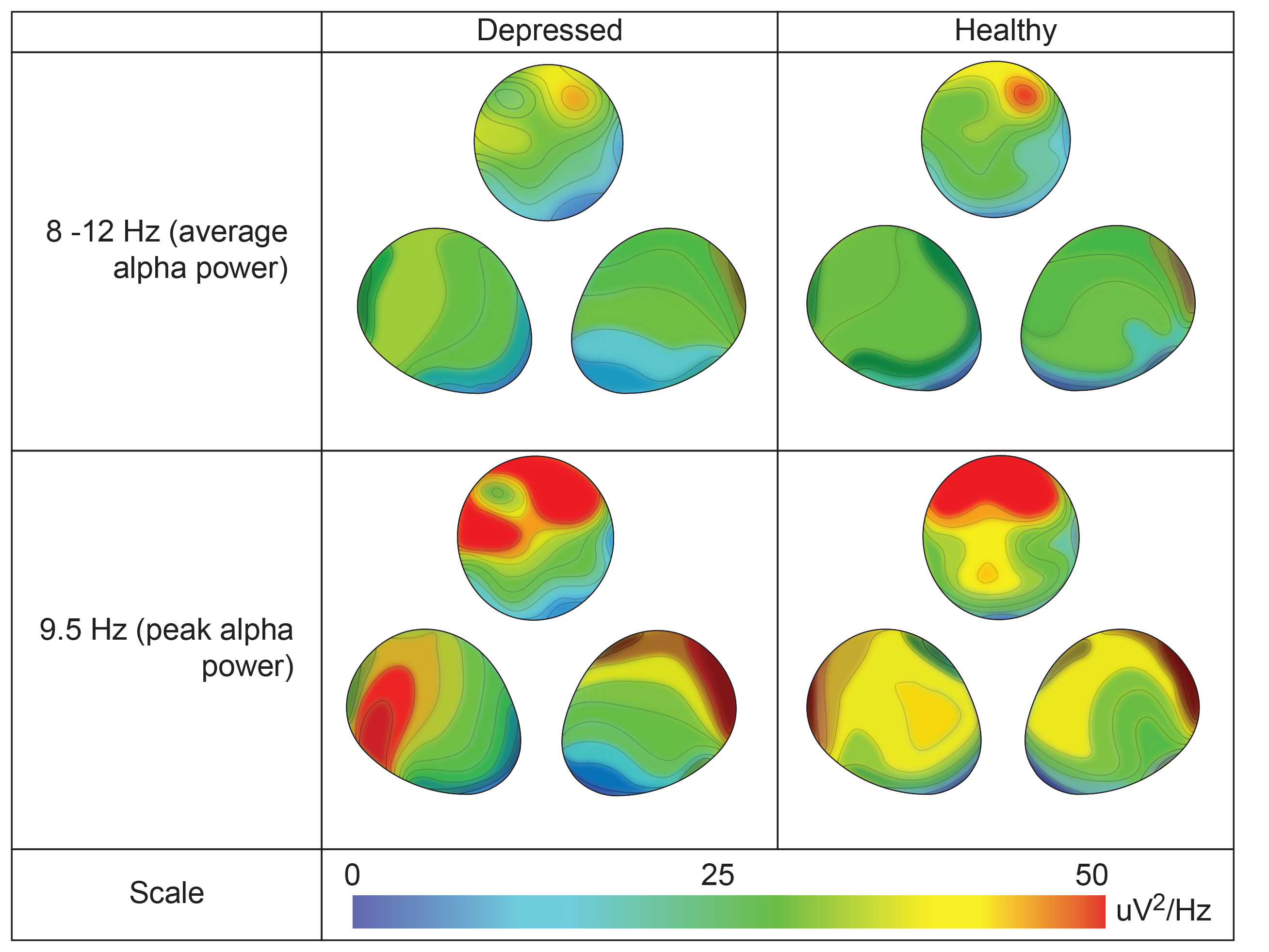

The second level is psychological, concerning the client’s cognitive and emotional condition. For example, suppose a client complaining of depression has prefrontal alpha asymmetry reversal (i.e., greater alpha amplitude at F3 than at F4). In that case, this suggests the possibility of electrode placement at F3 and F4 and the use of an alpha asymmetry protocol. Graphic redrawn by minaanandag on fiverr.com.

Authors' caption: Topographical distributions of 8–12 Hz band average alpha power (top) and 9.5 Hz peak alpha power (bottom) for depressed (left) and healthy (right) participants, showing a top view stretched across all recording sites, along with two 3D-rotated views to display frontal laterality. Depressed participants assessed at pretreatment show a more diffuse anterior-to-posterior pattern of alpha activation (note contour lines), unlike healthy participants who retain focused right frontal activity. Both groups have a peak frequency at 9.5 Hz, at which the noted contrast is particularly evident. Contour lines are spaced at intervals of 5 μV2/Hz.

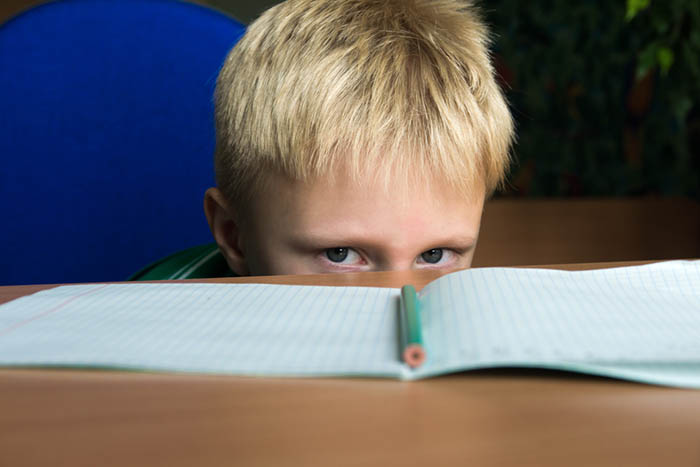

The third level of analysis has to do with socially significant behavior change in a specific context. For example, an assessment of a child with ADHD may show distractible behavior and poor grades in classroom settings, deficient sustained attention, anxiety, and significantly excessive central theta EEG. A central bipolar electrode placement could be considered with a protocol that rewards SMR to improve attention and academic performance.

Consideration of these levels of analysis in real-world contexts such as school, work, play, or social situations yields what can be called a holistic biopsychosocial description of the client’s condition, that together with knowledge from neuroscience research, leads to an account or formulation of why the client may have the symptoms they present. Such information can also suggest where to place electrodes and what EEG variables to train.

Research Findings

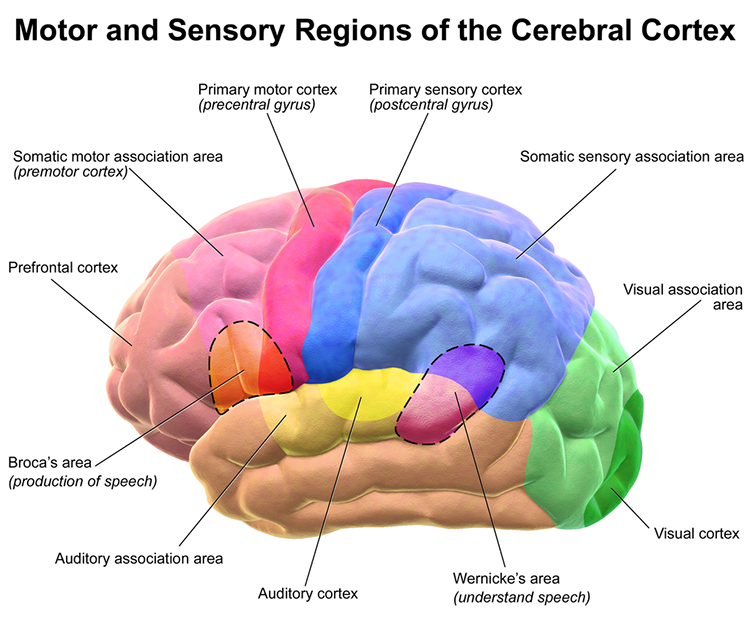

Research findings to consider are of several types. One type is related to brain-behavior relationships and functional neuroanatomy. For example, language functions are a strength of the left hemisphere, and damage to the left temporal region may compromise language use. Graphic courtesy of Blausen.com staff "Blausen gallery 2014," Wikiversity Journal of Medicine.

A second type of research finding has to do with the functional significance of EEG findings and the correlation of various conditions with particular EEG signatures. For example, excess right frontal high beta and beta spindling have been associated with anxiety, and excess posterior beta has been related to anxiety. The movie below is a 19-channel BioTrace+/NeXus-32 display of low beta (13-21 Hz) and high beta (22-34 Hz) activity © John S. Anderson. Brighter colors represent higher beta amplitudes. Frequency histograms are displayed for each channel.

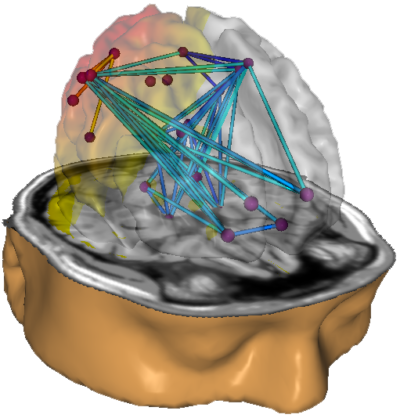

Third, anomalies in different brain networks are associated with various conditions and abilities (e.g., abnormality in default mode network functioning and depression). Neurofeedback training can increase or decrease connectivity using a normative database. For example, BrainMaster's BrainAvatar software allows clinicians to train specific networks, like the Default Mode Network (DMN).

Last, neurofeedback efficacy research is essential to consider. For example, midline theta/beta training protocols have shown reliable efficacy in changing EEG, attention, and classroom behavior for children with ADHD. Graphic © Oksana Mizina/Shutterstock.com.

With the description of the client’s condition and agreement on goals to address with training, a good next step is to consider the degree to which research evidence shows benefit from any neurofeedback for goals that are similar to the individual with whom the practitioner is working.

The Efficacy unit of the companion Neurofeedback Tutor: An Introduction explained the scientific evidence levels and the differing levels of evidence available for various neurofeedback protocols for various client problems and goals. For some conditions, such as ADHD, there is a relatively large body of scientific evidence to support the efficacy or even effectiveness of neurofeedback.

Additionally, there may be more than one neurofeedback method that has been shown to have some degree of efficacy. With ADHD, for example, theta/beta and SCP training along the midline have both been helpful. Therefore, one of these methods should be considered helpful to the client in this illustration.

As presented in the video for developing training protocols, a helpful strategy for the protocol section can be based on an arousal model that classifies client presentations into overaroused and underaroused. Research supports various protocols to address each of these two categories.

Selection of electrode site and EEG training parameters can also be based on an understanding of functional neuroanatomy, that is, the function of the cortical tissue beneath an electrode site or in a cortical region of interest or Brodmann Area, or the role of a particular location in brain networks that participate in particular functions or disorders. Researchers have revised the Brodmann maps and correlated areas with their functions. The Brodmann maps below were contributed by Mark Dow, Research Assistant at the Brain Development Lab, the University of Oregon to Wikimedia Commons.

Selection is also based on normative values of frequency bands in particular locations and the understanding of whether excess values for EEG parameters may represent overarousal or underarousal in that area that could compromise a psychological or behavioral function.

Robert Thatcher and his team continued to work with the Neuroguide database and have continued to develop the features of 19-channel z-score training, most recently with the development of swLORETA, a more precise and accurate iteration of the LORETA source localization method.

Caption: NeuroNavigator swLORETA

This has resulted in a large base of clinicians using this approach. More than 50 publications have presented evidence of the efficacy of z-score neurofeedback training, suggesting widespread acceptance within the scientific literature (https://www.appliedneuroscience.com/PDFs/Z_Score_NFB_Publications.pdf).

John S. Anderson provides an example of z-score training. Video © J. S. Anderson.

Research may show EEG patterns of significance in particular locations at specific frequencies associated with a given disorder, symptom excess, or symptom deficit. Particular disorders and patterns of symptom excess or deficit may be shown by research to be associated with an EEG pattern of significance at specific locations and in specific frequency bands. Such considerations can be especially relevant if a research-based protocol proves ineffective, in which case the practitioner can consider developing a client-specific protocol based on symptoms/goals, client EEG findings, and how research has identified EEG patterns to be associated with particular symptoms or conditions.

The practitioner asks, “For my client’s presenting complaints, is there a research-based protocol or a set of research-based findings that is relevant and corresponds to the client’s EEG findings from the initial assessment?” The correspondence between symptom complaints, research findings, and EEG assessment findings directs the practitioner to the location(s) for electrode placement, to the frequency or other parameter(s) to train, and the direction in which to train the selected EEG parameter(s).

If other factors suggest that training should not follow research findings, the practitioner should account for their clinical reasoning for selecting a different training regimen. For instance, a client with ADHD may have shown poor benefit from theta/beta training but demonstrates abnormalities in a brain network such as the attention network that may account for the client’s symptoms, which leads to the decision to conduct neurofeedback for the attention network. An alternative method such as swLORETA z-score training to normalize the relevant network then becomes a reasonable regimen to pursue.

Additionally, suppose a client does not respond to a research-based protocol. In that case, the practitioner can consider findings from neuroscience and EEG research in the context of the client’s condition to select a protocol that may be effective.

Environmental Context

The external world in which the client lives provides a context that may facilitate or impede neurofeedback training. This external social and material context, while being of less importance for selecting protocols per se, may greatly influence how and when the selected protocol is delivered. Family stability can be a strength in the environmental context, whereas family instability may suggest the postponement of neurofeedback. Graphic © fizkes/Shutterstock.com.

Whereas having a job may normally be considered a strength, periods of excessive job demand may also be times to wait before doing neurofeedback.

In other situations, the availability of academic or social demands may provide an advantage as they offer situations in which to practice skills learned during neurofeedback, or at least to develop self-awareness about changes in the experience of those situations produced by neurofeedback. The support of family and friends who are part of the environmental context may be of assistance either in the training office or in the home, where remote training may depend on a family member's aid.

Resources

The selection of training protocols depends on the software and hardware that the practitioner has available. Such resources range from single-channel to 19-channel systems, with software capability ranging from amplitude and coherence training to the training of individual Brodmann Areas or brain networks using z-score methods. Material resources for remote training may be an additional consideration in some cases. Staff resources may be an additional factor if training sessions need to be scheduled multiple times per week. Family resources may be a significant consideration for children who require transportation and support to engage in neurofeedback.Client psychological resources are another area to take into account. Internal client resources may be psychological, such as motivation to change at this time, degree of self-awareness, communication, and cognitive abilities. Physical health should also be considered. For example, neurofeedback may be optimal when the client is ready and interested in training, can demonstrate some degree of self-awareness, can communicate at an age-appropriate level, and has stable physical and mental health along with good sensory abilities.

Suppose the client has less than average psychological and physical resources. In that case, neurofeedback can be accommodated by several preliminary steps. These might include motivational interviewing to build readiness for change, peripheral biofeedback and self-monitoring to enhance self-awareness, matching verbal information to the client's ability level, and providing training at times when the client’s health is stable. In general, however, these factors may be of more importance to how a protocol is delivered than the protocol selection per se.

Practitioner Expertise

Given the client’s condition and goal and the scientific evidence available to support neurofeedback training protocols for that condition and goal, the practitioner consider whether their training, skills, experience, and equipment allow them to provide effective treatment. Among practitioner factors is the neurofeedback model to which they subscribe. However, different models have different applications, so a practitioner trained in multiple models has the most effective armamentarium from which to draw when addressing their client’s goals. Graphic © Eti Ammos/Shutterstock.com.

Most practitioners, however, will have expertise in what can be called an evidence-based model, which has its foundation in scientific investigations of neurofeedback efficacy and effectiveness. Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

Additional to this foundation may be models of neurofeedback that are based on clinical studies and experience and the neuroscience of brain-behavior relationships. When research is unavailable to provide strong support for a specific neurofeedback protocol to address the client’s condition, the practitioner must employ their knowledge of clinically-based models and neuroscience to aid in selecting a training plan for the client.

Ethical principles are important. Practitioners should provide neurofeedback only for conditions for which they have reasonable training or seek supervision. Ideally, the practitioner will have sound understanding and experience with the clinical condition that the client presents, skill with neurofeedback methods for that condition, and knowledge of how that condition is related to the brain and psychophysiological findings. Graphic © WIN12_ET/Shutterstock.com.

Client Values and Preferences

The practitioner provides the client with a formulation that describes the problem, integrates the factors above into a provisional model that suggests the cause of the problem, and suggests training options. The options, with their likely costs and benefits, are reviewed with the client so that they can make an informed decision about which neurofeedback method to use or whether to pursue neurofeedback at all. This process recognizes the ethical principle of autonomy, the importance of informed consent, and acknowledges the client’s values and preferences. Graphic © ANDREI ASKIRKA/Shutterstock.com.

Decision-Making and Ongoing Problem-Solving

Using the factors just reviewed is an evidenced-based biopsychosocial approach to neurofeedback training that collaborates with the client to support their autonomy for making informed decisions about protocols that are most likely to provide benefit and least likely to do harm. Together with the choice of a training protocol, the practitioner and client should agree on explicit and measurable goals at one or more levels of analysis.

At a biological level, changes in EEG variables are one type of goal. At a psychological level, neurofeedback may aim to change emotional and cognitive function. At the level of observable behavior, goals may be to change the client’s actions in a specific context (e.g., performance at school or in a competitive sport). Goals are usually measured and quantified using the same methods employed during the client’s initial assessment.

Once a training protocol and goals are selected, and the protocol’s implementation in progress, the neurofeedback provider should conduct ongoing assessment of EEG, psychological, and behavioral variables so that changes relative to pre-training findings can be reviewed with the client to determine the degree to which the protocol is having its desired effect. If progress toward the client’s goal is not seen within a reasonable time, the provider should conduct a re-assessment to generate new training options. Furthermore, adjustments to the protocol or selection of an alternative protocol should be made if unwanted side-effects occur. Neurofeedback concludes when no progress is seen or when goals have been achieved.

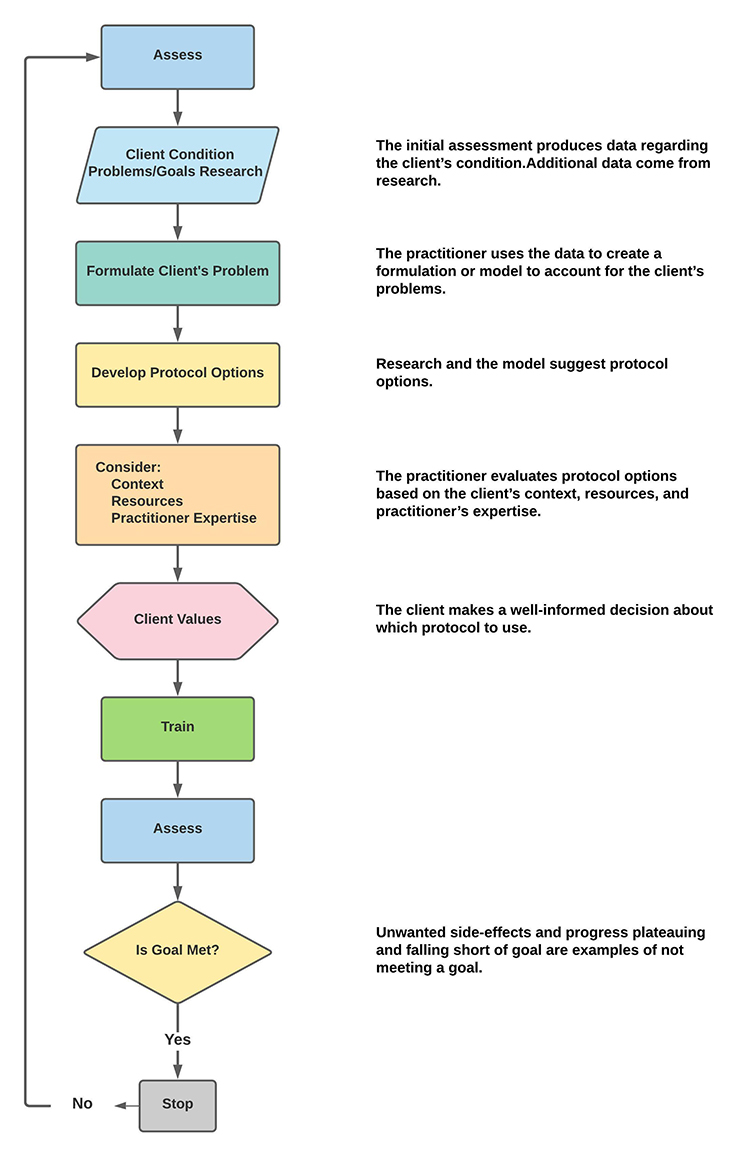

Flowchart

This section of Neurofeedback Tutor presents factors that should be considered when making decisions about electrode placement sites and EEG variables used when providing neurofeedback to an individual. These factors can be organized into an artificial flowchart, with the provision that practitioners should abandon the flowchart when there are valid reasons and when they can account for their decision to do so.

For any individual case, the relative weights of each factor in the decision-making flowchart will vary, making one or another component more prominent in choosing a training regimen. The implication is that practitioners should always be prepared to account for their clinical reasoning. These factors also give the practitioner recourse for problem-solving when an initially-chosen training plan fails to provide sufficient benefit.

Below is a simplified flowchart that depicts the preceding discussion.

Components of this flowchart ask the following questions:

1. What is the client’s psychological or behavioral problem?

2. What is the problem with their EEG concerning location and EEG parameters?

3. What problems do other tests show?

4. What research evidence is available that shows the efficacy of a neurofeedback protocol for issues identified by questions 1, 2, and 3?

The practitioner essentially is looking for the best match between problems and protocols to address them. Usually, the best protocol to start with is one for which there is supportive research evidence. That protocol is then introduced in an “experimental” or trial-and-error manner of testing the hypothesis that the protocol will be effective. If the hypothesis of protocol effectiveness is not borne out, then the practitioner resorts to selecting an alternative research-based protocol, if one is available, or considering how information about the client’s condition (e.g., problem, EEG findings, other test findings) match with an understanding of neuroscience, brain-behavior relationships, and EEG research to make decisions about protocol features that have to do with electrode location, training frequency, frequency parameter, and training an increase or decrease of the selected parameter.

FROM ASSESSMENT TO TRAINING

The process of progressing through the assessment stage of working with a new client to the choice of protocol and training and then reassessment will be discussed through a series of client case examples.

Assessment has been covered in other sections within Neurofeedback Tutor. We begin with the client intake interview, which may have been facilitated by the client completing one or more history and symptom forms to guide the interview process. Once the client’s presenting concerns have been identified and discussed, the history of those concerns and whatever interventions have been tried can then be included to determine the previous level of treatment resistance and/or resolution experienced.

The client’s reasons for seeking neurofeedback training as a possible way to address these concerns can also be discussed. This is often an appropriate place to explain the underlying concepts of biofeedback training in general and neurofeedback training specifically. Particular emphasis on neurofeedback as training, not treatment, can be important at this stage of the developing clinical relationship.

Establishing the roles of both the client and the clinician is important to understand the training process. Many clients expect that neurofeedback and other types of biofeedback are treatment interventions in the sense of something being done to the client, similar to taking a medication or receiving physical therapy or a stimulation treatment such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

Because all biofeedback involves training and education, this can be difficult for some clients to understand and accept. Biofeedback providers sometimes hear comments from clients such as “it didn’t work” or “that didn’t do anything.” This disconnect between the client’s expectations and the reality of the biofeedback training process may need to be addressed throughout the clinical intervention.

Once the client understands the nature of the biofeedback training process, the clinician can proceed with whatever testing seems warranted, given the information obtained both in the clinical interview and from previous providers.

Foremost among those tests will be an objective physiological evaluation of measures such as autonomic nervous system reactivity, EEG behavioral characteristics and responses to tasks, and possibly a continuous performance or other computerized neurocognitive and task response test.

The EEG assessment has been discussed in great detail elsewhere in Neurofeedback Tutor, and actual client examples showing the results of these assessments will be provided.

Finally, all intake and testing information will be evaluated, and a training approach will be designed for the client to maximize the effectiveness of the training process.

Training will be described to the client, and an agreement to participate in the training will be obtained from the client. This agreement will be an ongoing component of the process. Before each subsequent training session, the client’s responses to previous training will be briefly evaluated, and the client will be asked if they wish to continue with the training. Any changes in protocol will be discussed with the client, and their agreement to continue will be noted in the client’s chart.

One of the most important aspects of the clinical relationship in biofeedback is the collaborative nature of the process. The clinician needs the client's active participation, and one of the clinical goals is for the client to become a partner in the training process. The more informed and knowledgeable the client, the more likely they will give useful feedback about what they are experiencing and how the training affects them and their lives.

Re-evaluation is also an important part of the training process. A regular schedule of revisiting the initial assessment tools can become an integral part of the clinical relationship. Ideally, the reassessment will guide protocol changes and help identify when the client has reached a plateau where no further change is likely.

These steps listed above will be illustrated in the examples below.

PATIENT EXAMPLE A

Client A is a 38-year-old woman referred for quantitative EEG evaluation and neurofeedback training.

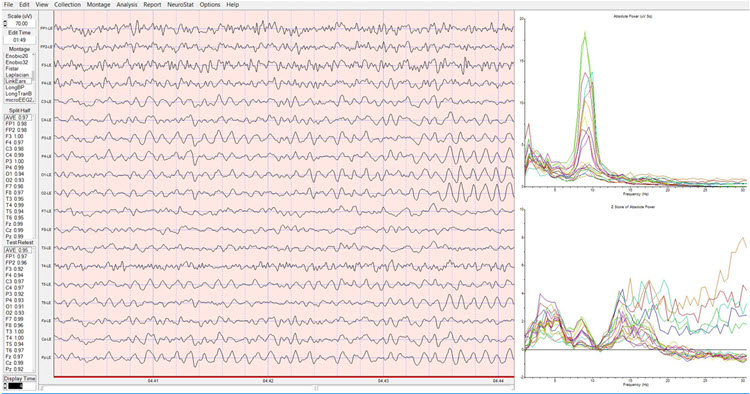

An EEG recording session followed an initial intake and history session. A sample of eyes- closed and eyes-open EEG plus a sample recorded during an eyes-open task condition was obtained.

The information from the client's history indicated Client A had received a diagnosis of persistent depressive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). She reports symptoms including attention problems, repetitive thoughts, feelings of inferiority, memory problems, difficulty making decisions, and some problems with communication, including word-finding and some difficulty with interpersonal skills.

She reports an unremarkable prenatal and birth history and states that development was typical, with good grades in all school stages. She attended college, received a BA degree in education, and began an elementary school teaching career. She continued to teach for various school systems in her area for the next 12 years.

She reported a motor vehicle accident when she was 25 years old, though she states that she was taken to the ER and was told, following a head CT scan and skull x-ray, that she had no damage and was allowed to go home. She reports lingering headaches for several weeks and neck pain and fatigue. She consulted with her physician, who sent her to physical therapy once a week for approximately 3 months. She reports this was moderately helpful with the neck pain but did not resolve her headaches or fatigue. She does report some brief loss of consciousness at the time of the accident and believes that she struck the left lateral frontal side of her head on the driver-side window.

She could not find resolution through her medical providers and therefore pursued alternative approaches such as massage, chiropractic, herbal medicine, and acupuncture. She reports the chiropractic adjustments were quite helpful but that she needed regular visits, usually 2-3 times per month, to sustain the improvement in her headache pain. She also reports that the acupuncture was helpful for her neck pain and her general malaise, though again, she needed regular visits to sustain the improvements.

She reports some continued neck pain, headaches, general difficulty with focus and attention, and some difficulty with interpersonal relationships, which she states was not the case before the MVA.

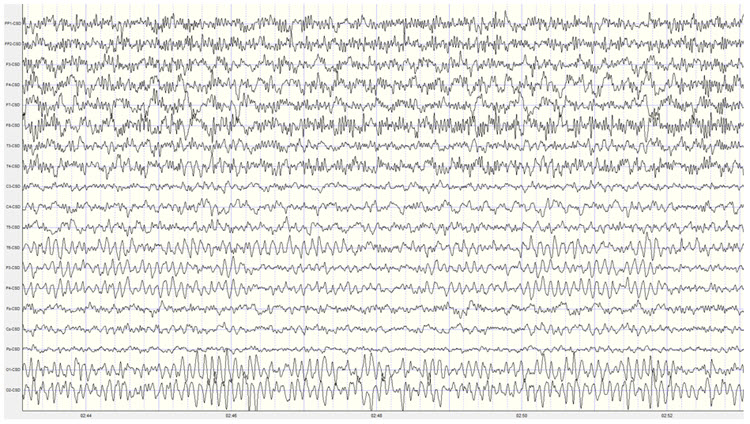

Electroencephalograph (EEG) data were collected using the international 10-20 electrode placement system using 19 active electrodes referenced to linked ear electrodes. A Nexus-32 acquisition unit with BioTrace-32 software was used for neurometric EEG collection. All electrode locations maintained a DC offset below 25 mV. There is substantial eye movement in both eyes-closed and eyes-open recordings. There is also persistent, localized EMG artifact noted throughout the eyes-open recording in the F7, F8, T3, and T4 electrode locations.

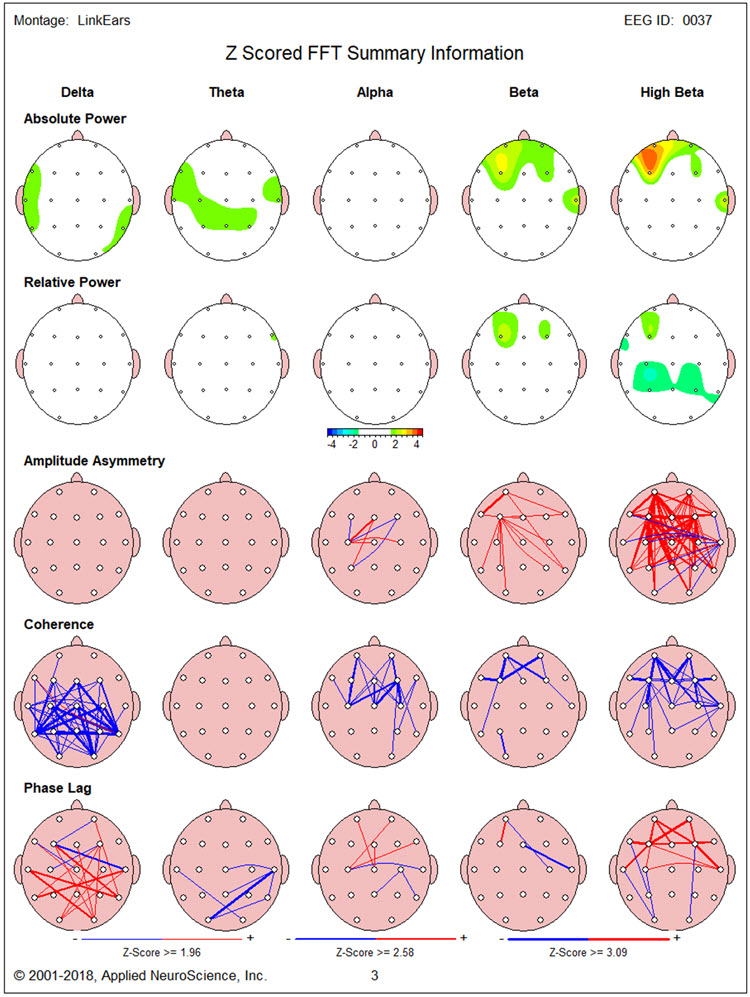

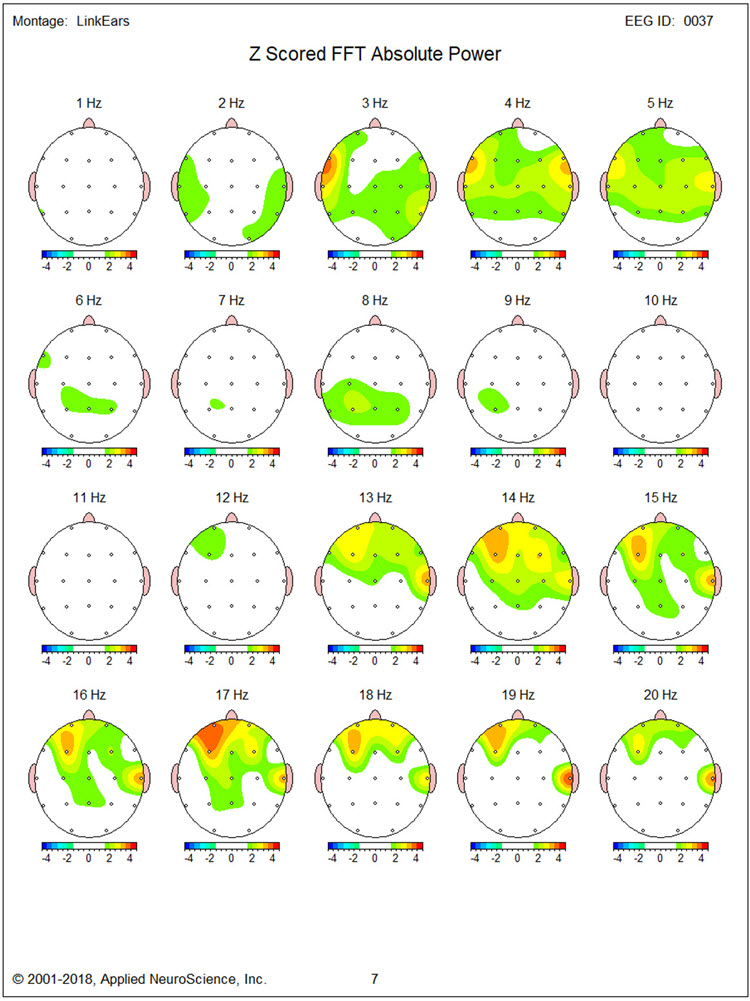

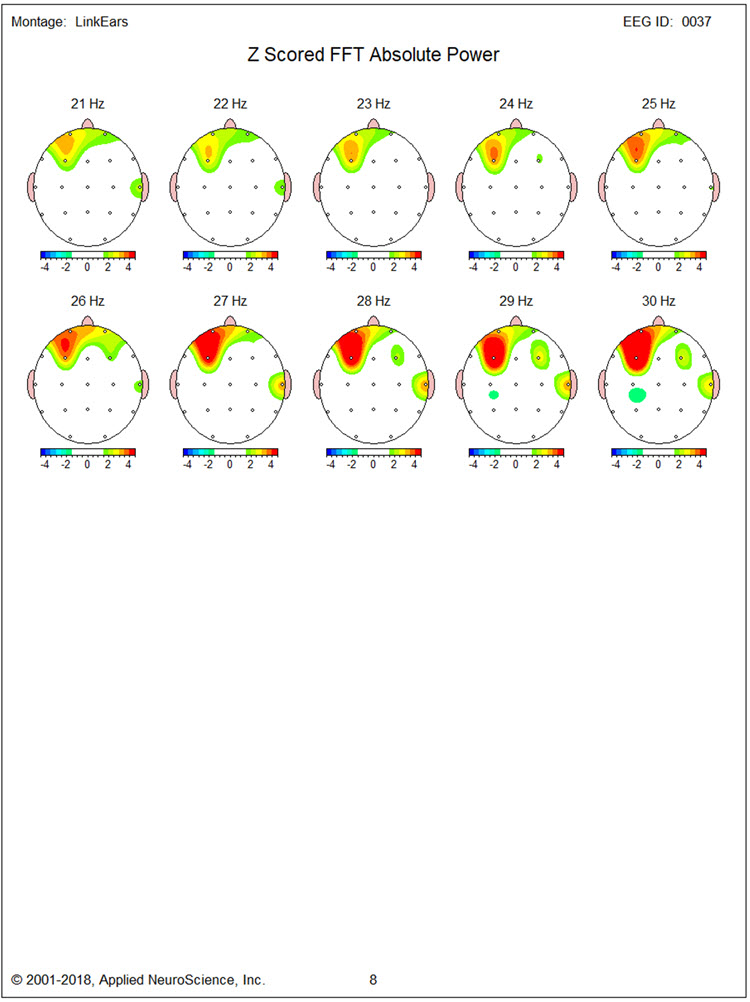

The record was visually inspected following recording, and artifact-free epochs were selected from the eyes-closed recording. However, it was impossible to find artifact-free segments due to the persistent muscle artifact in the eyes-open recording. Therefore, the effect of the artifact is noted in the report below. This analysis was performed using the NeuroGuide database software comparing Client A's record to age-matched normal research participants and a discriminant function database for traumatic brain injury due to her history of an automobile accident. Further analysis was performed using the Key Institute LORETA database version 2003 combined with Lifespan database z-scores. This appears to be a valid and interpretable administration.

The EEG was reformatted in various referential and bipolar montages for visual inspection.

VISUAL INSPECTION OF 19-CHANNEL EEG:

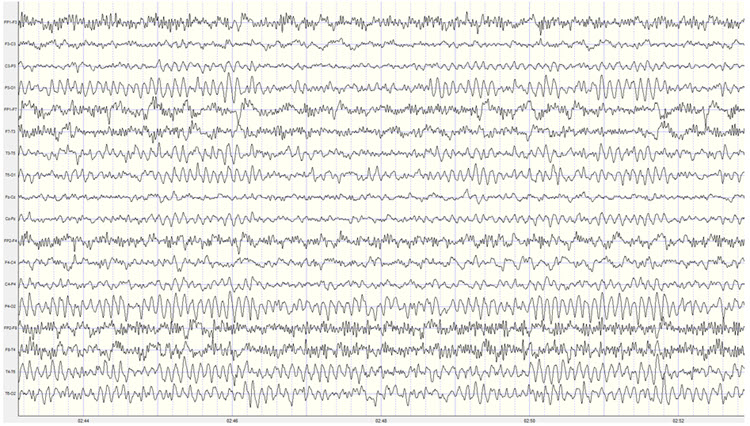

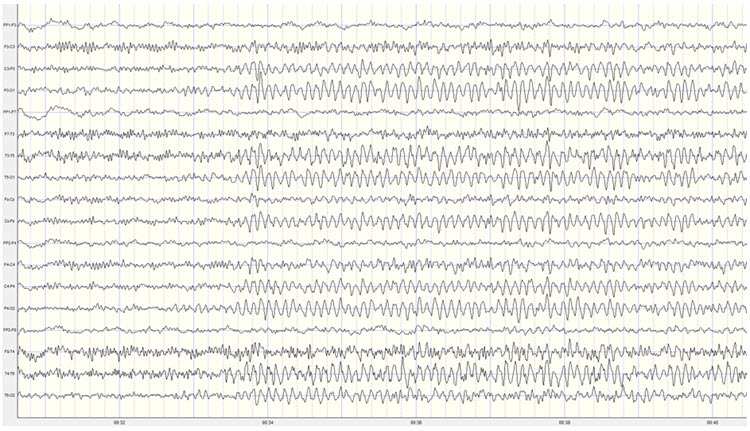

EYES-CLOSED CONDITION

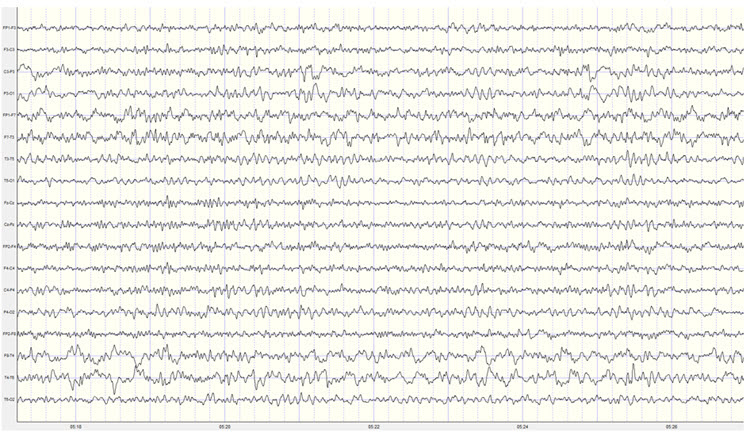

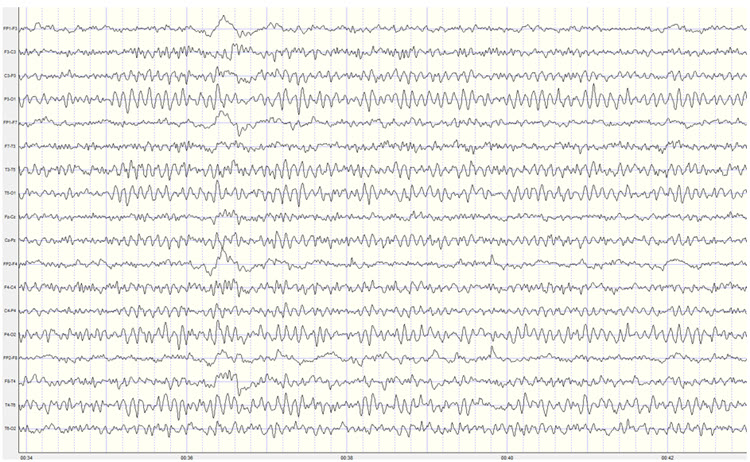

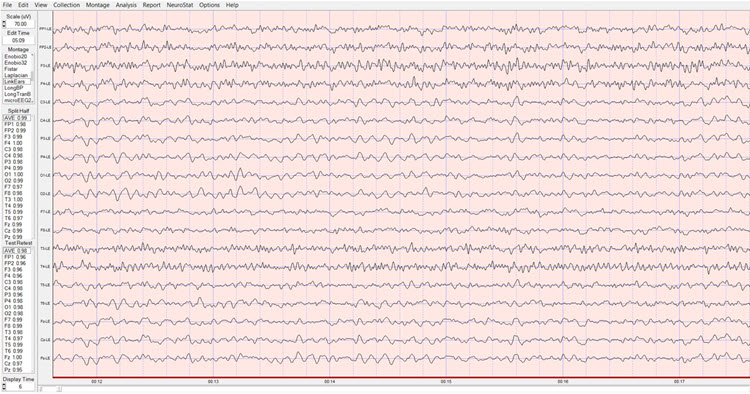

This is a fair quality recording with a persistent EMG artifact, primarily in left frontal and temporal derivations, though it is also present in right frontal derivations. There is typical lateral eye movement artifact that appears frequently, and those segments containing artifacts were not used for statistical analysis.

In the longitudinal bipolar montage, there is a generalized posterior dominant rhythm in the occipital and parietal derivations, extending to some degree to the central derivations. The frequency is approximately 9 Hz, with voltage generally in the 25-35 µV range, with some bursts exceeding 50 µV at the P4-O2 electrode derivation and exceeding 40 µV at the P3-O1 derivation. The posterior rhythm is asymmetrical, with higher voltage in right side derivations, emphasizing the T4-T6 and T6-O2 derivations.

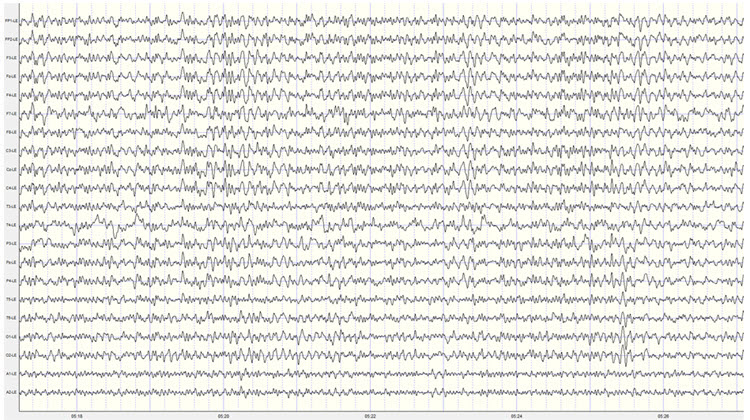

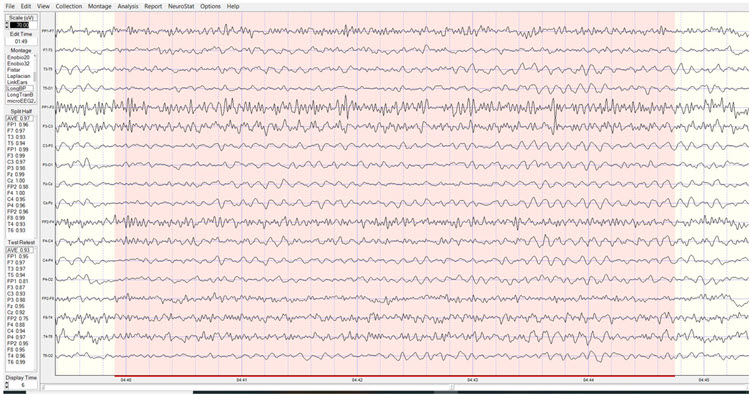

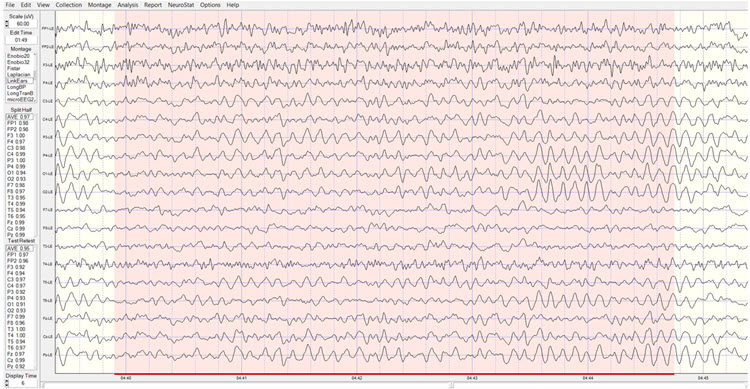

Caption: Longitudinal Bipolar Montage – Scale 50 µV 1st Recording

The record was re-montaged in various bipolar derivations, which revealed additional alpha activity in the temporal leads, which likely also appears in the ear references. This likely contributes to reference contamination in the rest of the electrode locations in the linked ears montage. There is also bilateral frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital slow activity in the 3-5 Hz range.

The average reference montage clearly identifies the 9 Hz activity in the T6 electrode at up to 40 µV, as well as the more right side, O2 distribution of the posterior rhythm.

Caption: Average Reference Montage – Scale 50 µV 1st Recording

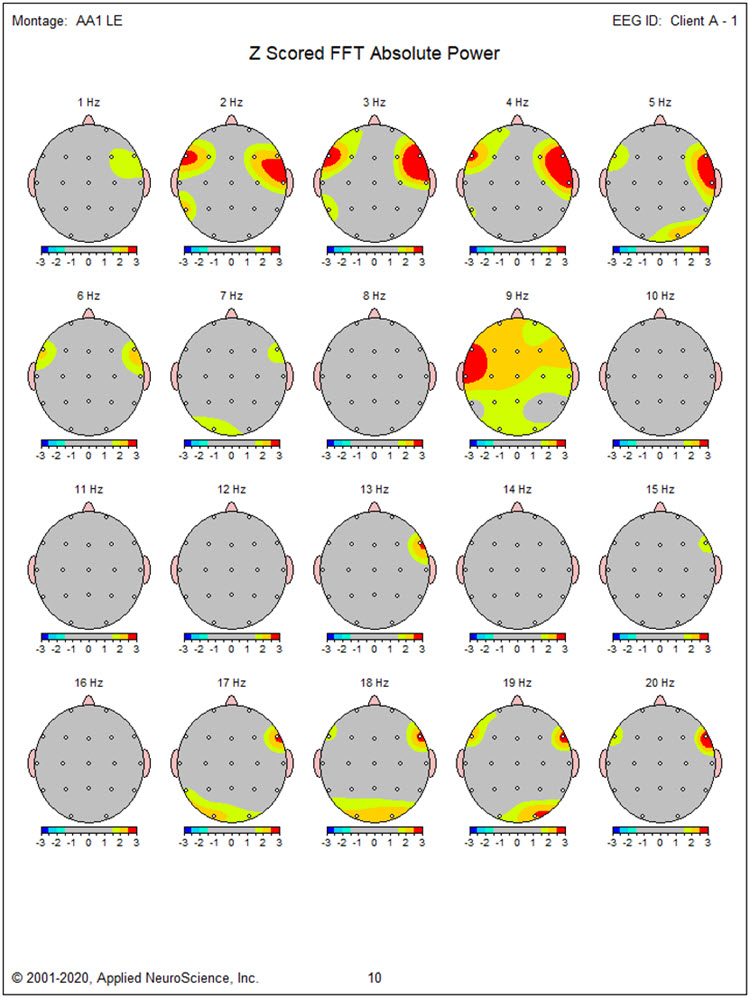

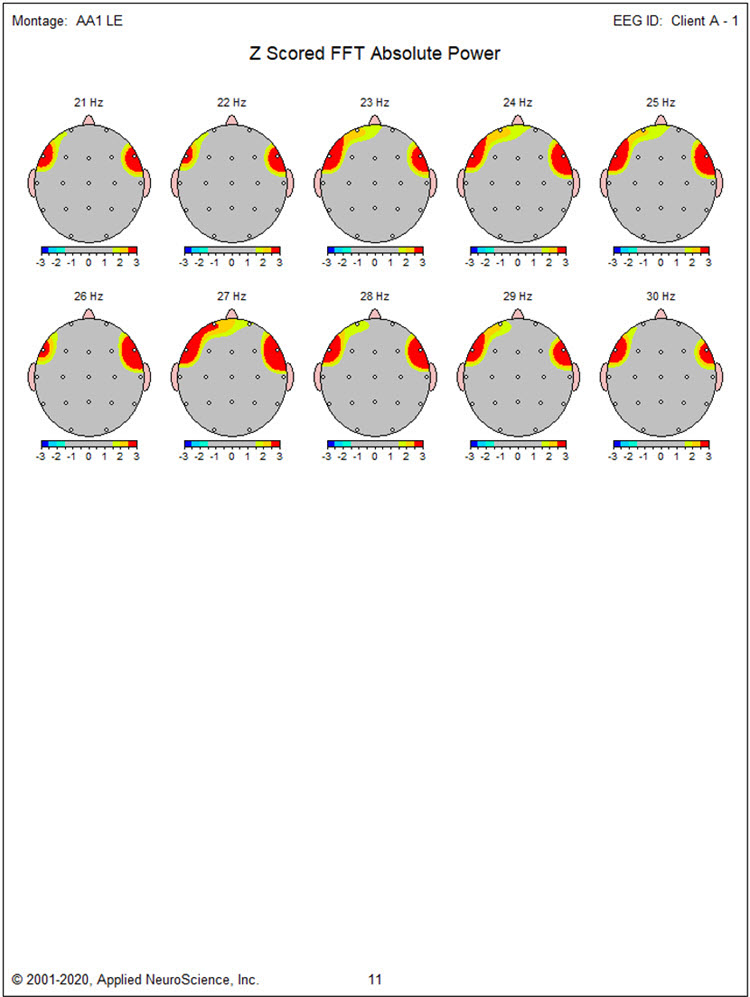

The linked ears montage shows a broad distribution of alpha activity, which is likely the result of reference contamination from the ear references, as noted earlier. Therefore, the elevated z-score values for frontal alpha in the linked ears statistical topographic maps should be disregarded. Also, in this montage, the posterior rhythm appears to be more symmetrical bilaterally at O1 and O2, and this is likely incorrect due to the findings from all other montage views.

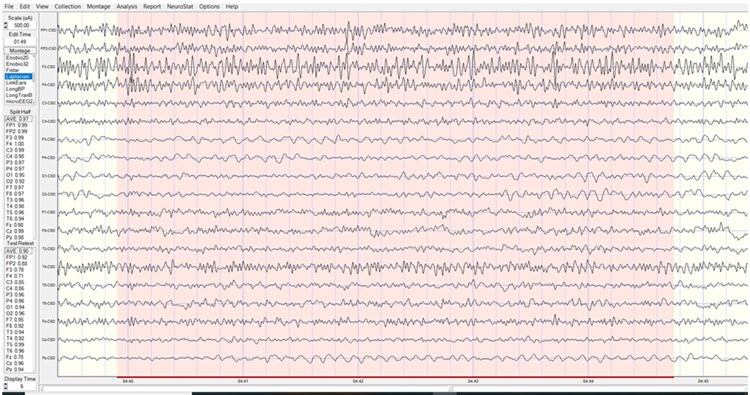

Caption: Linked Ears Montage – Scale 50 µV

The Laplacian montage shows a broad frontal and temporal EMG artifact that is likely an aberration due to the reference method using adjacent electrodes for calculating the montage. Other montages localized the EMG artifact primarily to bi-lateral frontal and temporal derivations that did not include F3, Fz, or F4 sensors.

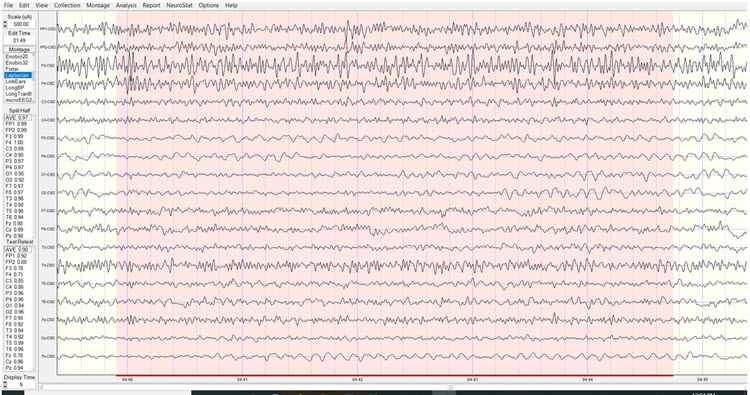

Caption: Laplacian Montage – Scale 400 µA

EYES-OPEN CONDITION

The linked ears montage shows appropriate attenuation of the posterior dominant rhythm to approximately 10-15 µV. There is significant muscle artifact in frontal and temporal leads, as noted above. Removal of the low pass filter reveals that this is indeed a muscle artifact rather than 60 Hz or another exogenous source artifact. There was also excessive, repetitive eye blink artifact, and therefore this eyes-open recording was not useful for statistical analysis.

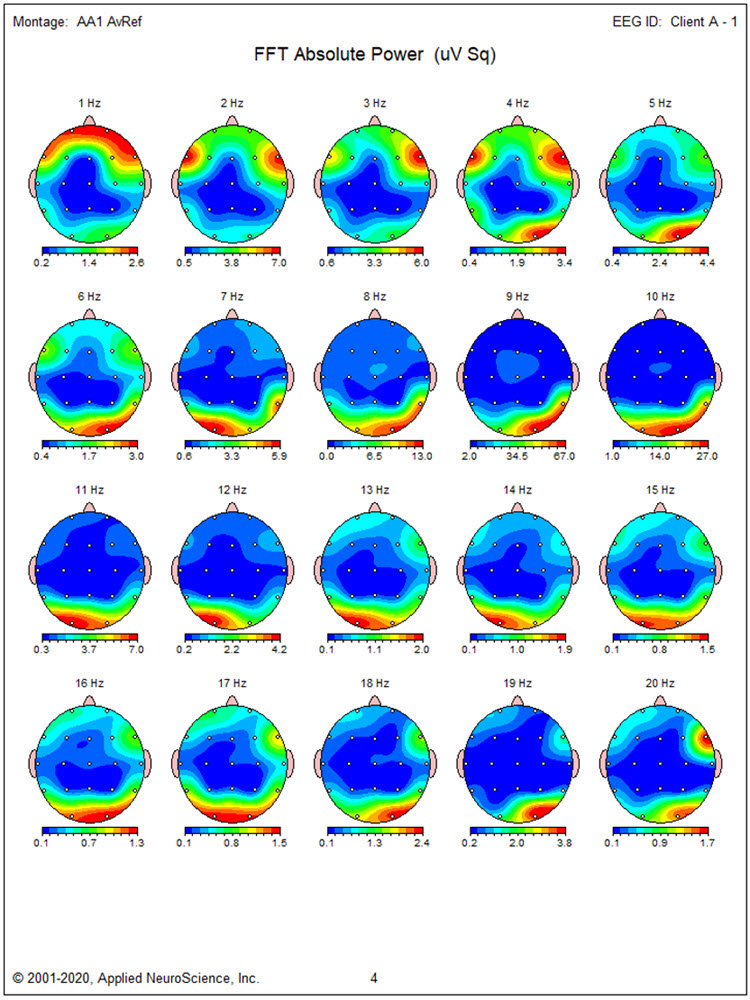

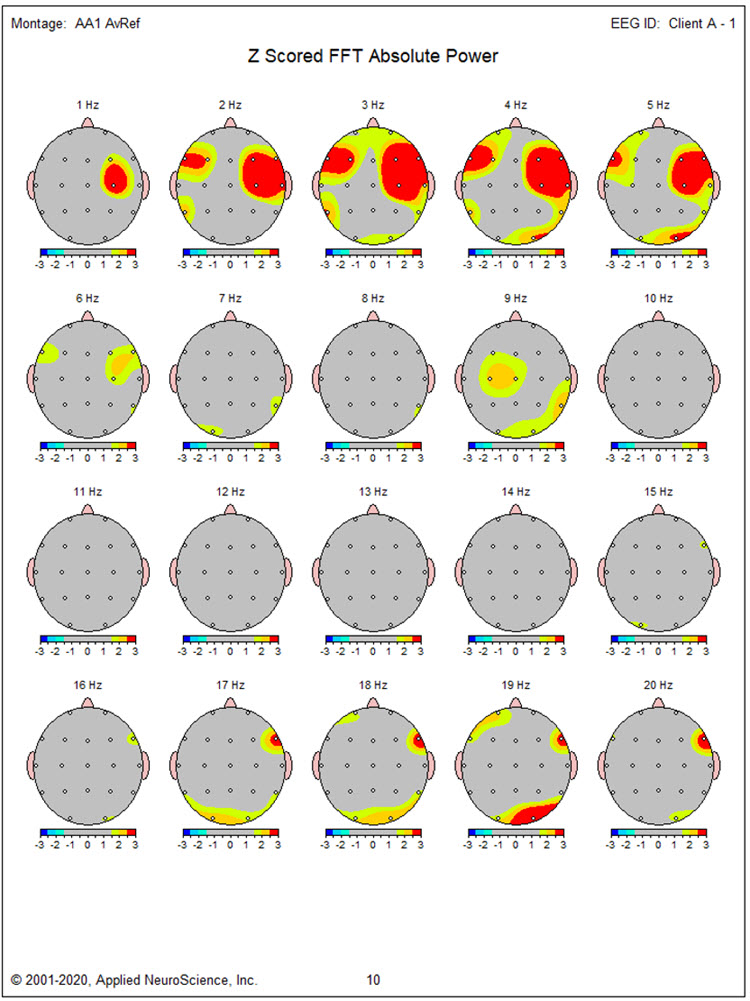

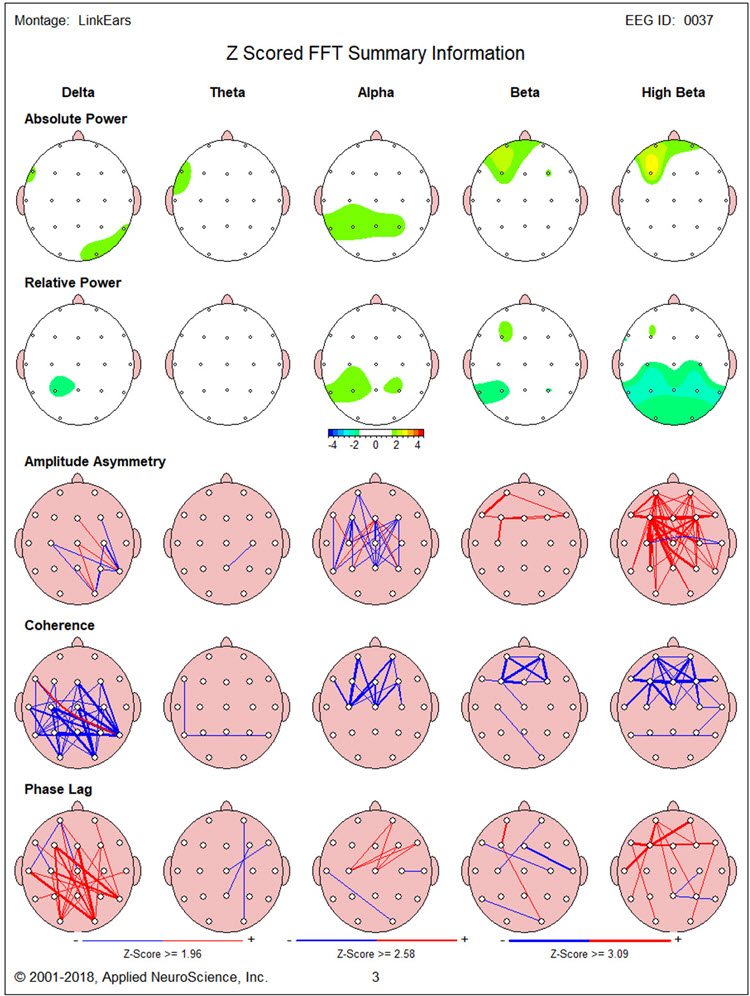

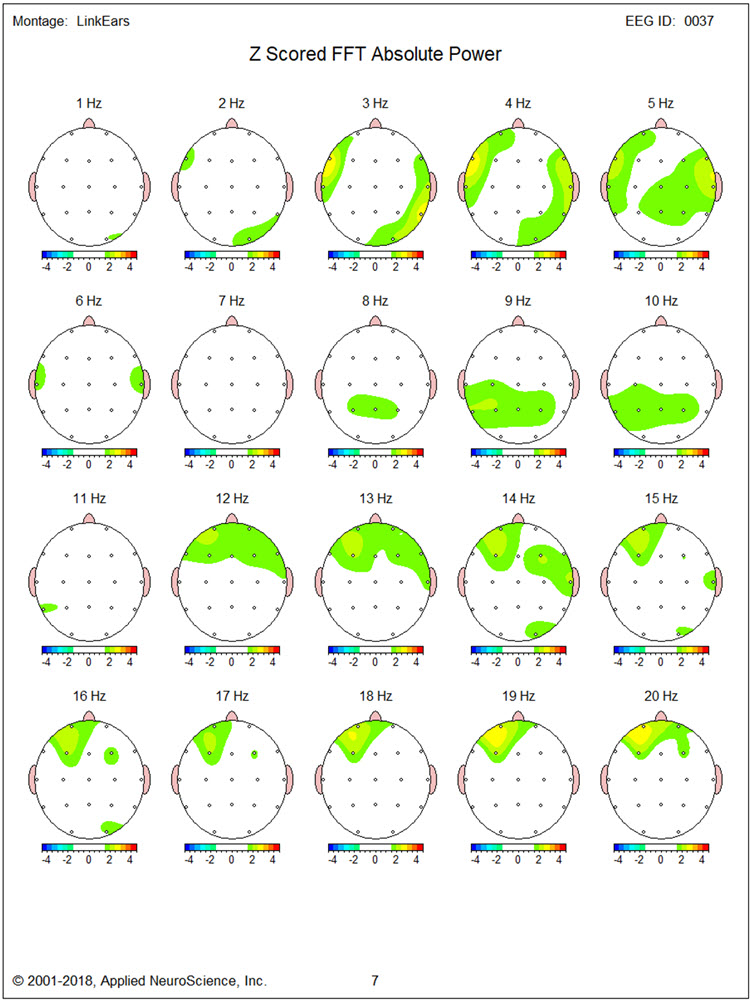

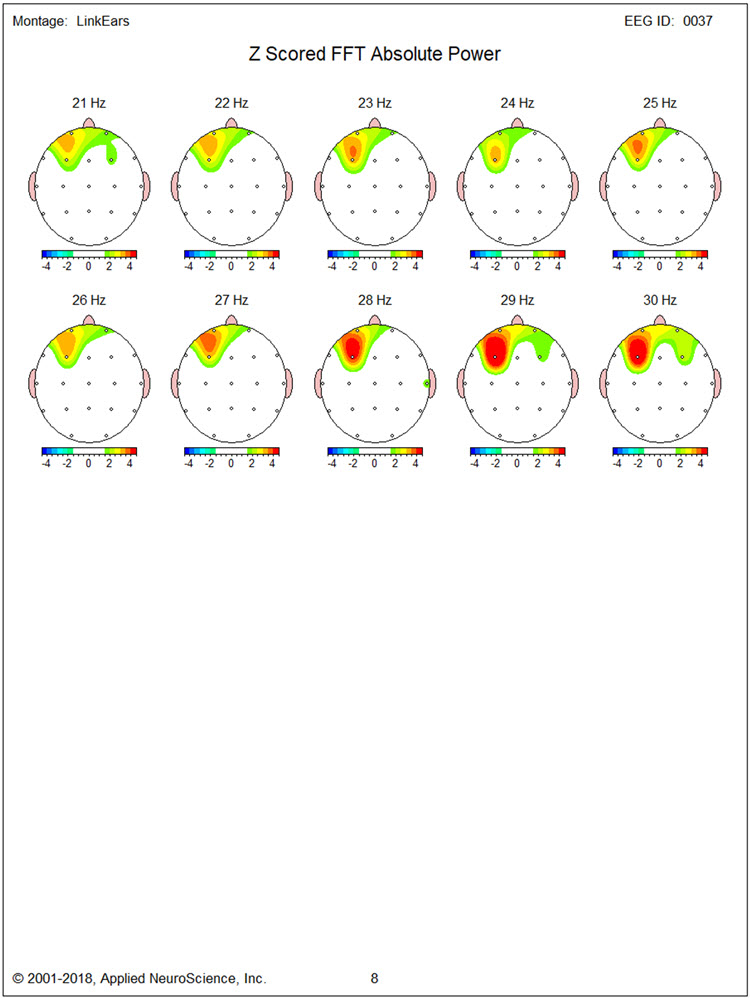

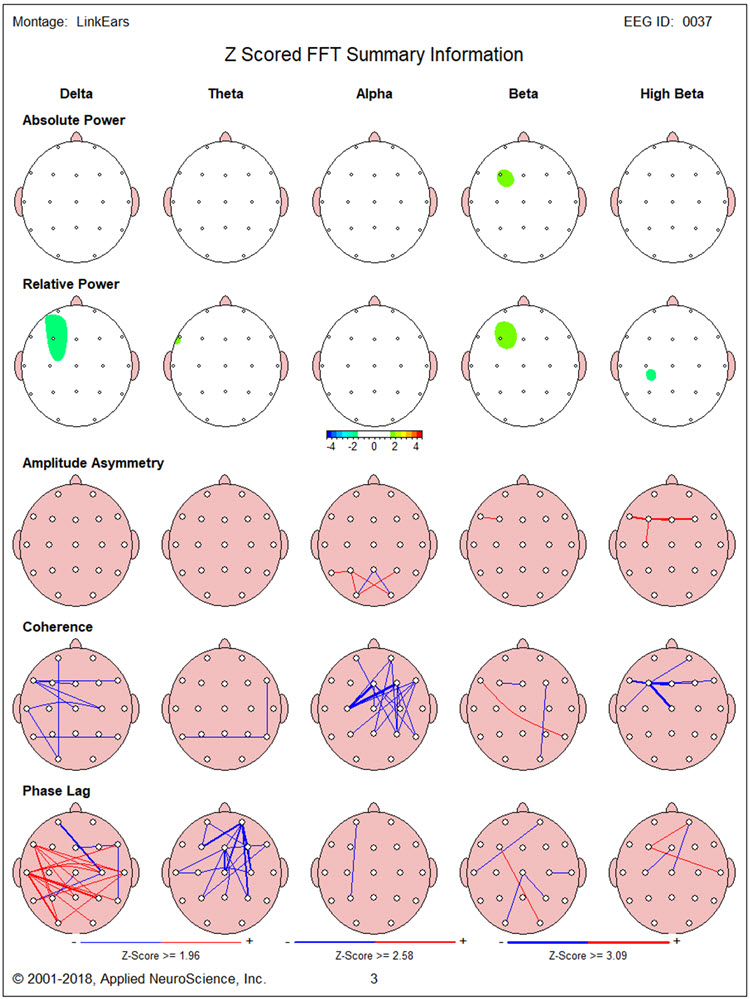

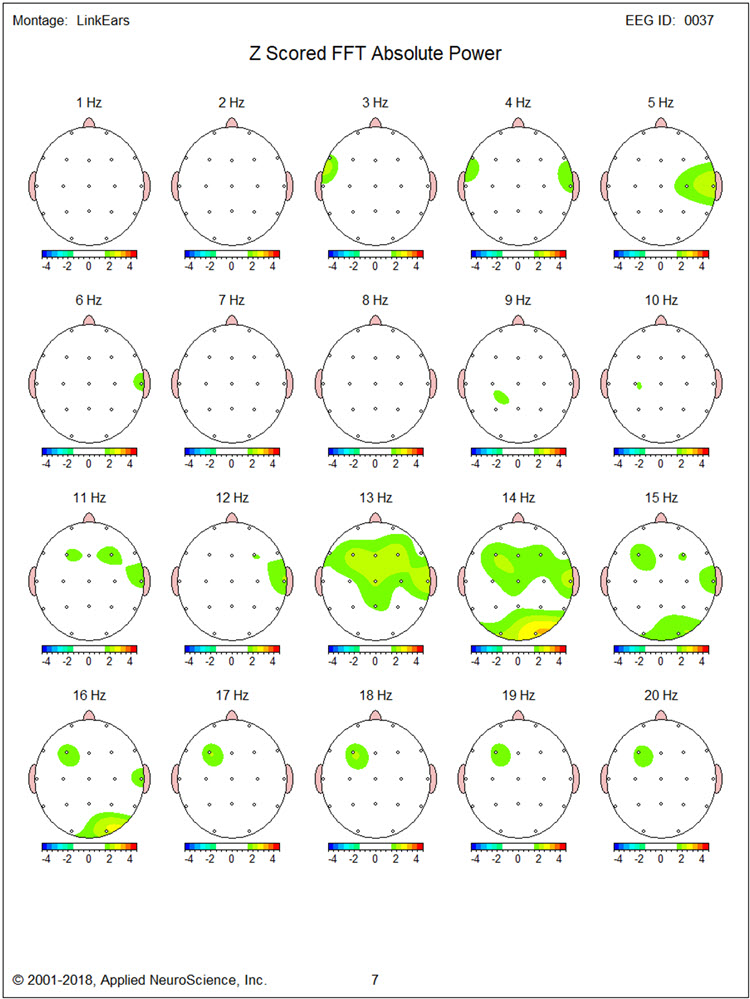

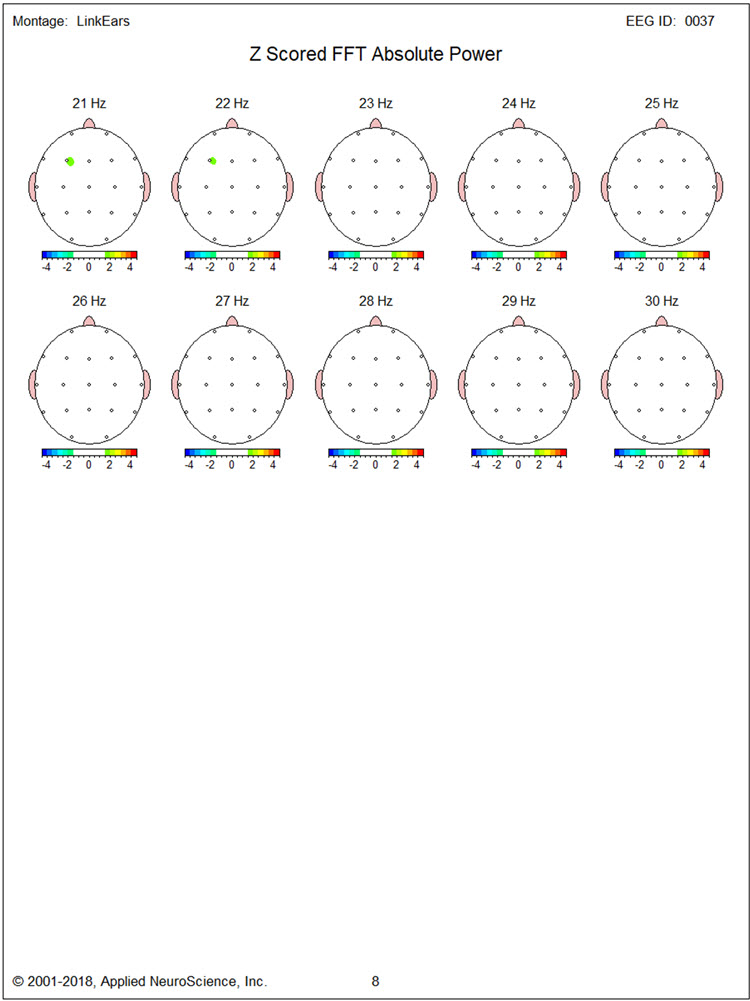

The quantitative analysis of Client A's eyes-closed EEG record indicates the following:

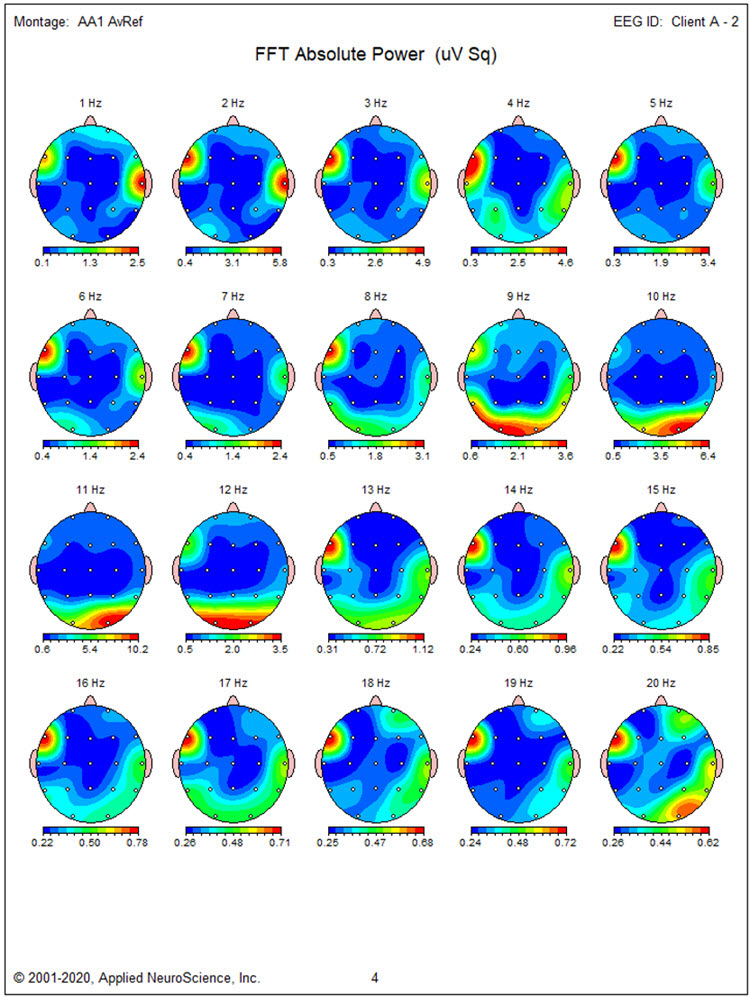

Absolute power topographic maps of the eyes-closed average reference montage show the maximum voltage in the 8-12 Hz frequency range at 9 Hz at O2 and T6 electrode locations.

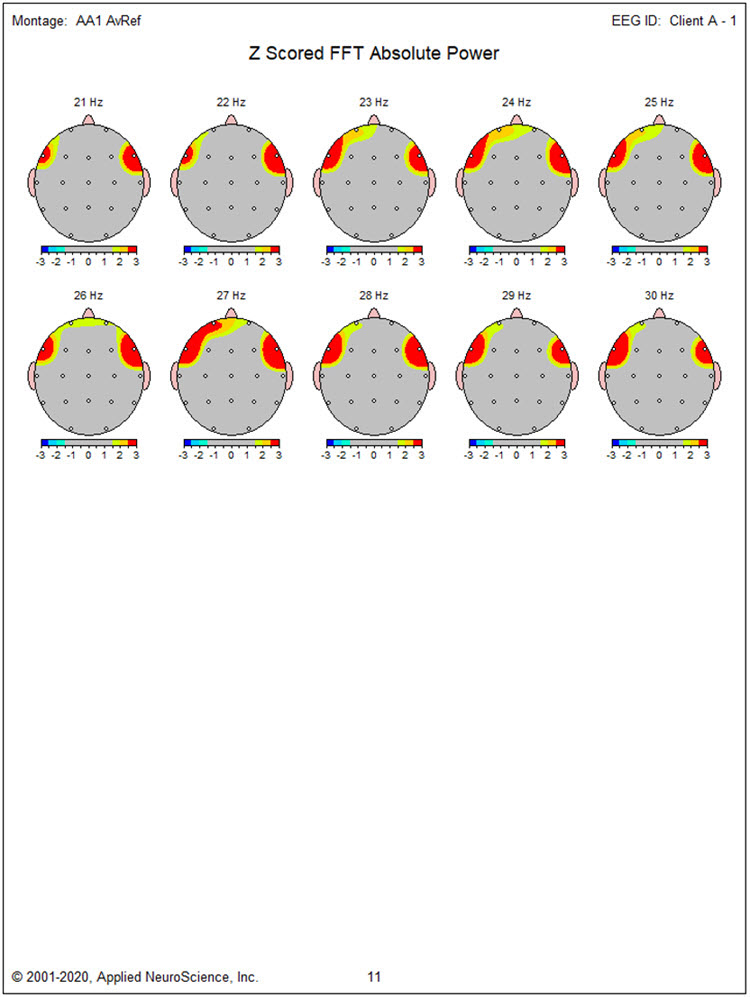

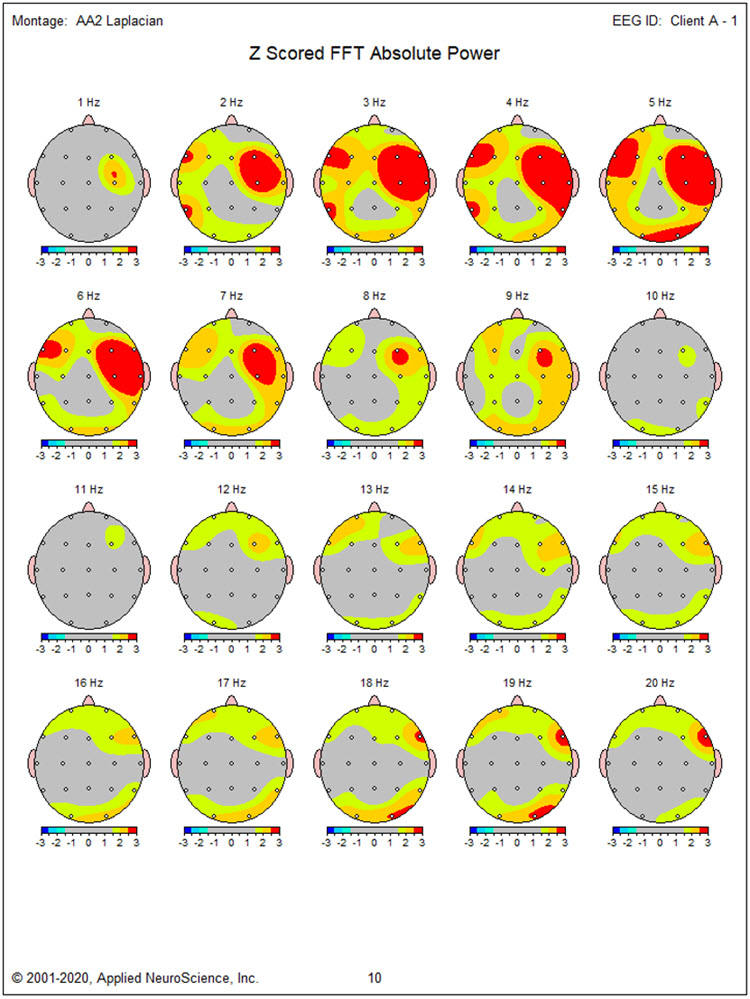

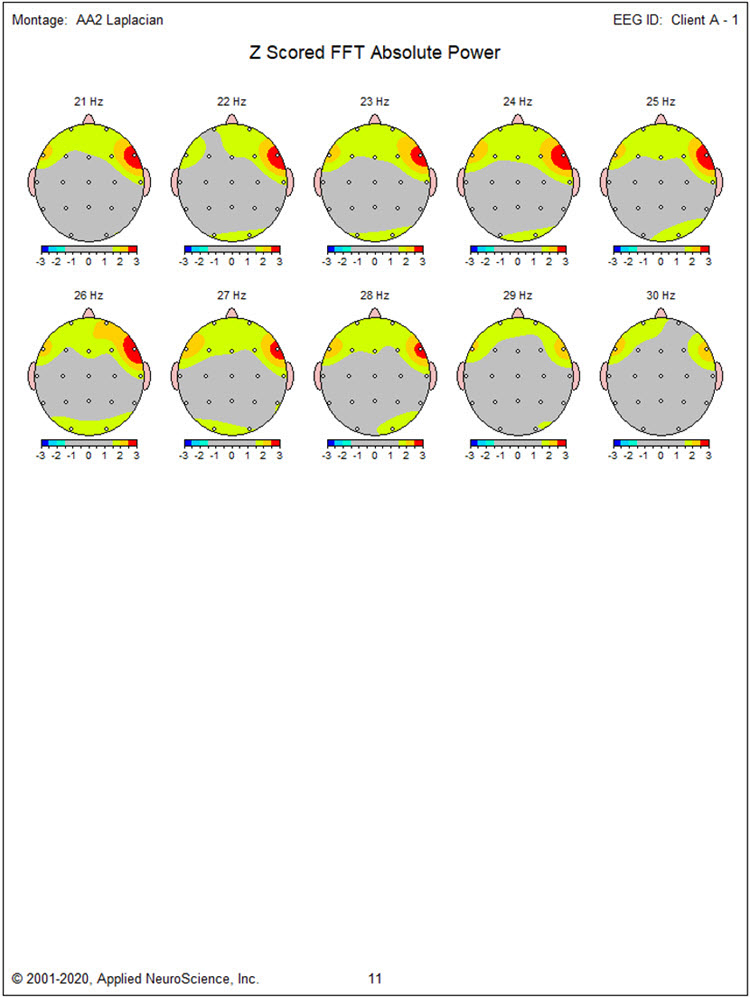

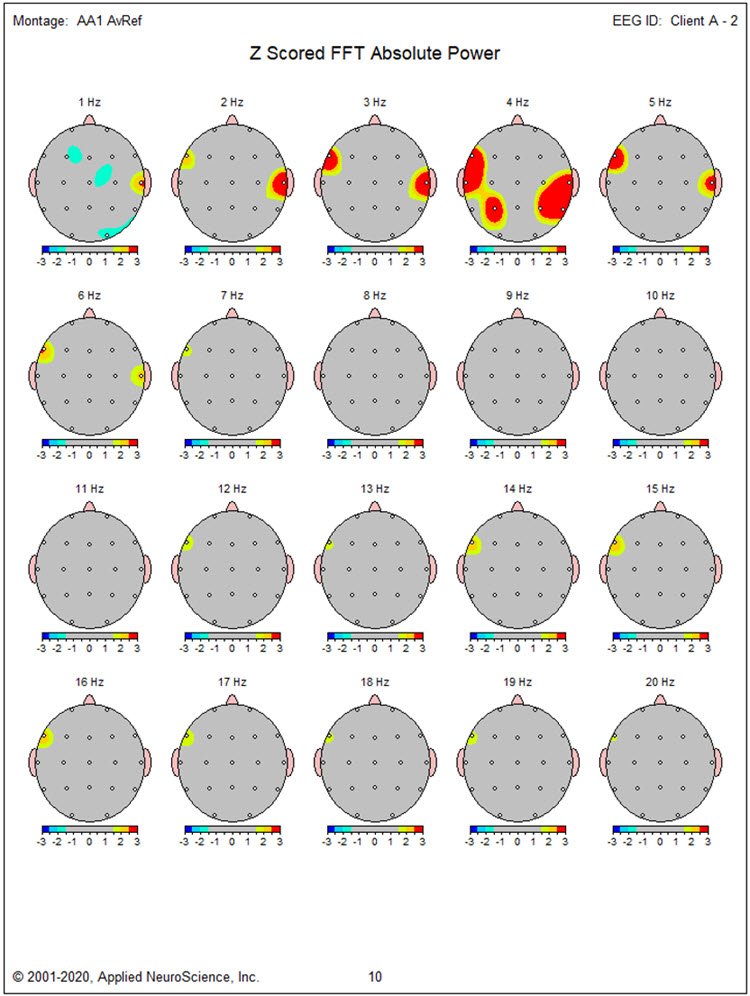

The statistical topographic maps of the eyes-closed average reference montage show the bilateral distribution of excess activity from 2-6 Hz with the greatest deviation from 2-5 Hz in bilateral frontal, temporal, right lateral parietal, and occipital electrodes. Excess activity at 9 Hz is localized to the F3, Fz, C3, and Cz electrodes and O2, T6, T4, and O1, with the greatest deviations in left central and right T6/P8 locations. Excess posterior 17-19 Hz activity and excess 17-30 Hz activity in bilateral frontal sensors are almost certainly associated with the EMG artifact noted earlier.

The Laplacian montage shows findings that are quite similar to those seen in the average reference montage with excess activity present from 2-9 Hz in this case. As discussed earlier, the excess fast activity is more pronounced and more broadly distributed, reflecting the EMG artifact, and should be disregarded.

The linked ears montage shows the bilateral slow activity from 2-6 Hz that extends to the right temporal and parietal/occipital areas. The excess 9 Hz activity is more localized to the left lateral frontal and temporal areas, although this may be related to the effect of reference contamination noted earlier. The excess activity from 17-19 Hz is seen in occipital sensors, and the excess lateral frontal 17-30 Hz EMG-related activity is seen here.

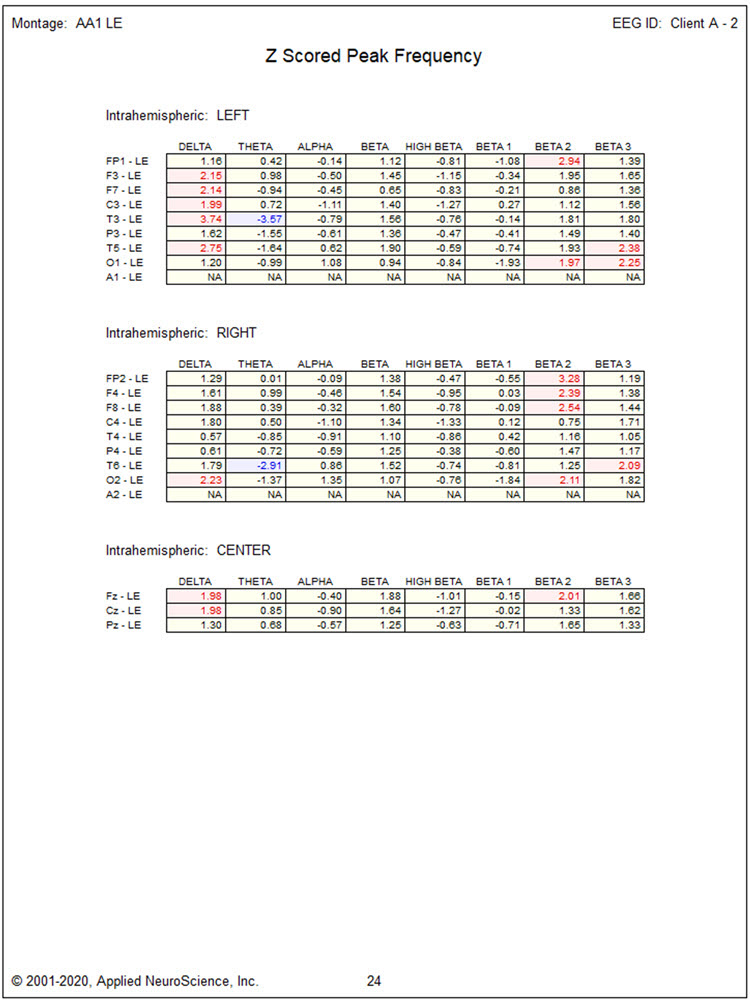

The z-scored peak frequency analysis in the linked ears montage shows some slowing of the peak alpha frequency. Exceeding -1 standard deviations at C3, T3, P3, C4, T4, P4, T6, O2, and Pz, with the greatest slowing at the P4 electrode site at -1.31 SD.

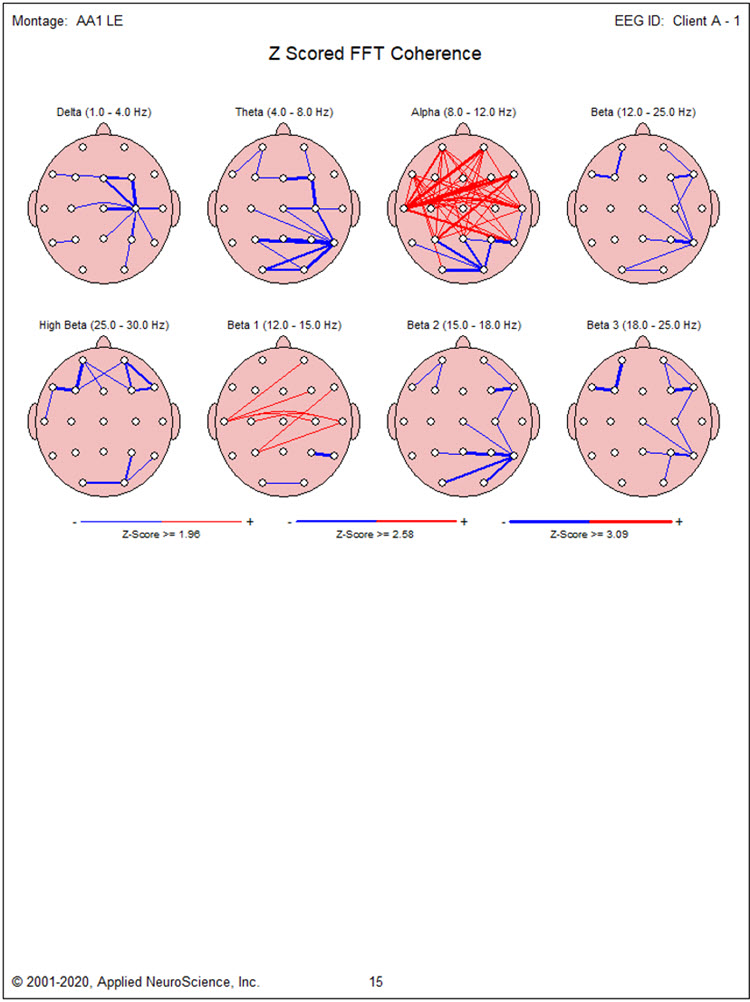

Coherence abnormalities show excess frontal, central, temporal and parietal hypercoherence in the alpha frequency band with some right lateral posterior and occipital hypocoherence in the theta and alpha frequency bands. There appear to be 2 somewhat focal areas of hypocoherence in multiple frequencies at the F7 and T6 locations.

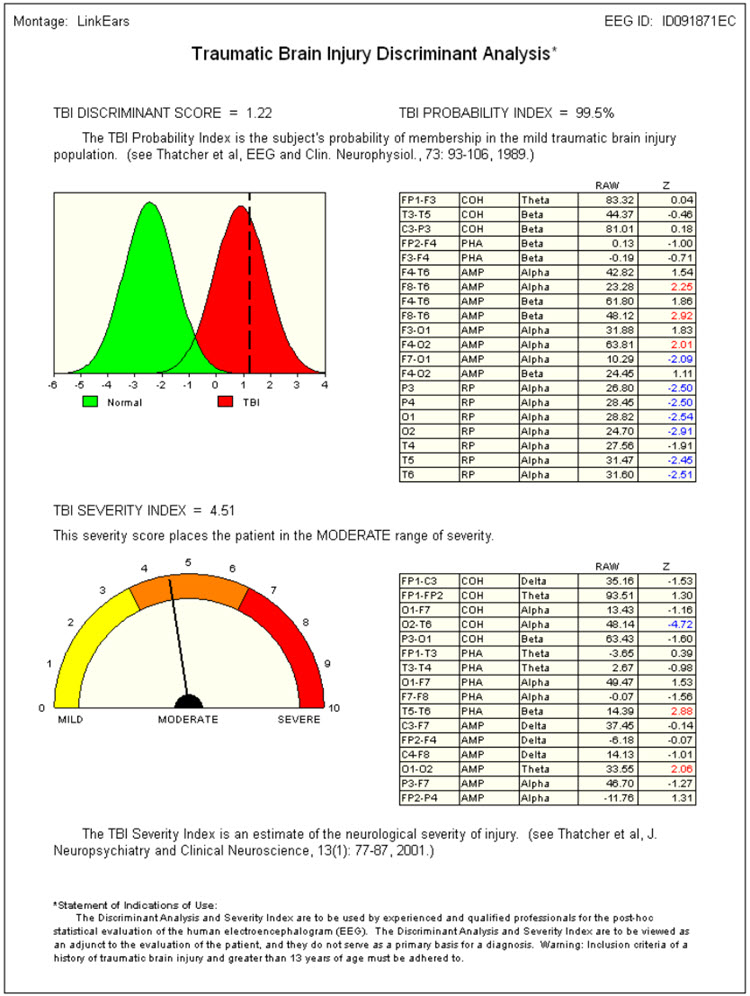

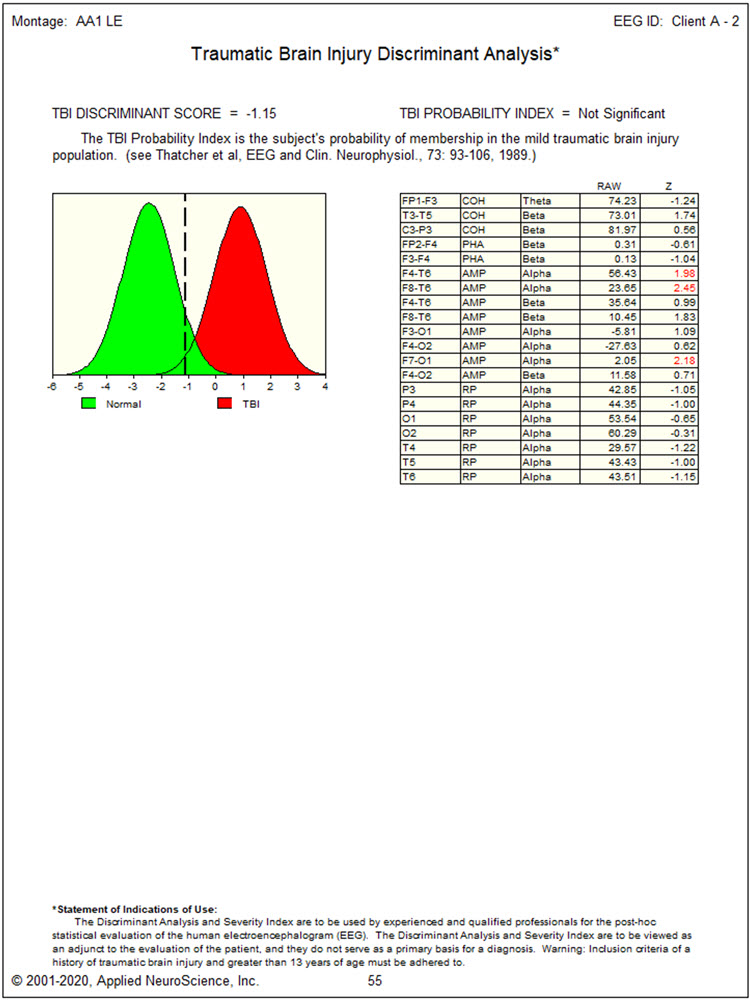

Due to the history of an automobile accident, the traumatic brain injury discriminant analysis was performed. It yielded a TBI discriminant score of 0.66, a TBI probability index of 99.5%, and a TBI severity index of 4.86, which is in the middle of the moderate range on a 0-10 scale where zero represents mild effects and 10 represents severe effects.

CONCLUSIONS:

This client presents with findings that suggest a possible lingering effect of the motor vehicle accident with a possible coup-contra coup injury from the left lateral frontal area at approximately F7 to the right posterior temporal/parietal/occipital area at T4, T6, and O2.

The left lateral frontal slowing may be associated with her experiences of depression, the bilateral frontal slowing may be associated with her perception of attentional difficulties, and the right temporal and parietal areas may be involved with the difficulty she is experiencing with social interactions.

A course of neurofeedback training is recommended beginning with 4 channel z-score training to address the difficulties that she is experiencing and try to correct the excess activity in the slower frequencies, normalize the coherence, and possibly resolve the slow peak alpha frequency. Sensor placement will initially be on F7, F8, T6, and O2 to normalize delta and theta frequencies. Subsequent sensor placement will be O1, O2, Fz, and Pz to normalize the frequency and distribution of the posterior rhythm.

Finally, alpha-theta training, rewarding an increase in 6-9 Hz and stabilizing 2-6 Hz and 13-36 Hz, will be used to integrate changes and help resolve social anxiety.

Additional home training is recommended, including heart rate variability training with a home training device and peripheral temperature training, also with a home training device. Sufficient practice in the clinic with these modalities should be included to familiarize herself with these techniques.

DISCLAIMER:

This evaluation is not intended to diagnose any medical or psychological condition. It is also not intended to substitute for appropriate medical or psychological diagnosis and intervention. Diagnosis and treatment should rely on a physician or mental health provider. Areas that show differences from expected values and the description of common symptoms associated with dysregulation in these areas are speculative, based on current neuropsychological understandings. Descriptions may not apply to this client, and any suggested findings may need to be confirmed through other testing.

NEUROFEEDBACK TRAINING:

This client participated in 32 sessions of neurofeedback training scheduled 1 to 3 times weekly and practiced at home with a RESPeRATE respiration training device daily. The initial sensor placement of F7, F8, T6, and O2 using 4 channel z-score training encouraged an average of all 168 z-score variables to decrease values toward zero. This proved quite successful, and the report from her referring psychologist indicated that her depression was significantly improved, as was her ability to function in day-to-day situations, particularly in terms of focus and attention. A review of her symptoms and training protocols was conducted at session 15, and the change to the O1, O2, Fz, and Pz locations was made as it appeared that the peak alpha frequency remained somewhat depressed.

This proceeded for 5 sessions, and then alpha-theta training was implemented using a 2 channel sum training approach with sensors at P3 and P4, with ear references. As noted previously, the reward was set to encourage an increase in 6-9 Hz and to inhibit 2-6 Hz and 13-36 Hz. This procedure was done eyes-closed using auditory feedback and was well tolerated by the client. She reported that this was particularly calming and helpful. After 12 sessions, she decided that she had achieved her goals and wanted to have a repeat 19-channel recording done to determine whether her EEG reflected the changes she was experiencing in her life. The repeat EEG was performed, and the results are included below.

This is a reassessment of this Client A’s EEG to determine any changes and to facilitate further training if warranted. The data was collected using the same equipment and software previously and processed in the same manner. The results are included below.

Client A reports significant reductions in depression, improved focus and attention, and more energy to engage with others and participate in activities. She does report feeling slightly over-activated at times, and this reminded her of how she was before the motor vehicle accident when she was a “go getter” to use her words. She can manage this occasion feeling of overactivation using the breathing and heart rate training she has practiced at home.

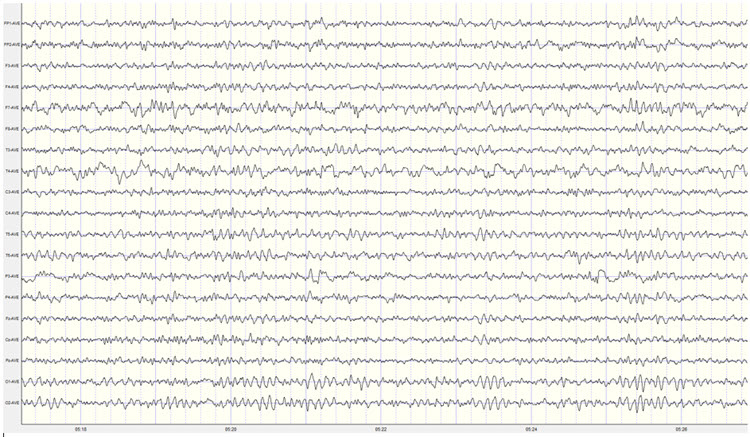

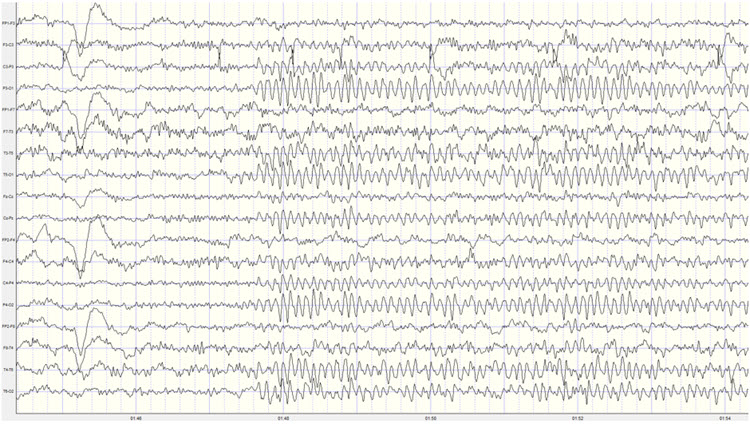

This is a good quality eyes-closed recording with minimal EMG artifacts seen in the T3 and T4 electrodes. There is minimal eye movement artifact, and overall the voltage is somewhat reduced from the previous recording.

When viewed in the longitudinal bipolar montage, a posterior rhythm is seen primarily in the O1 and O2 derivations with a frequency of approximately 10 Hz and amplitudes in the 15-25 µV range, with some bursts exceeding 30 µV. The voltage is more symmetrical than was seen in the previous recording, and the voltage at the P3-O1 and P4-O2 electrode derivations is quite similar. As the recording progresses, the frequency does speed up a bit to the 10-11 Hz range.

Caption: Longitudinal Bi-Polar Montage – Scale 50 µV

A pattern of slow activity with a frequency of approximately 3-5 Hz is seen in derivations associated with the F7, T3, P3, T4, and T6 electrodes. However, the voltage is significantly lower than in the previous recording.

The average reference montage shows the more symmetrical posterior rhythm with a 10-11 Hz frequency and amplitudes of 20-25 µV range. There is beta activity in the 15-20 Hz range in frontal and central sensors, and the slow pattern appears to be most pronounced in the F7 electrode location.

Caption: Average Reference Montage – Scale 50 µV

The linked ears montage continues to show reference contamination. Still, it is in the 20-25 Hz range in this case. This frequency pattern is seen in nearly every sensor at similar frequency and amplitude and with the type of phase synchrony often seen in cases of reference contamination. This contamination may be related to the EMG artifact seen in the T3 and T4 electrodes.

Caption: Linked Ears Montage - Scale 50 μV

The Laplacian montage shows more EMG artifacts in the T3 and T4 electrodes than in the other montages. This montage also seems to isolate the slow activity to the F7 electrode.

Laplacian Montage – Scale 400 µA

The absolute power topographic maps of the average reference montage show the more bilateral distribution of the posterior rhythm. The maximum voltage in the 8-12 Hz frequency band is at 11 Hz, closely followed by 10 Hz, though it remains somewhat lateralized to the right occipital at those frequencies.

The statistical topographic maps show excess 2-6 Hz activity at F7, T4, T3, P3, P4, T4, and T6. The distribution of excess activity is less than seen in the previous recording but remains a potential for further training to resolve the slow activity in these areas.

The z-scored peak alpha frequency in the linked ears montage is now more typical and shows a negative standard deviation only at C3 and C4.

The TBI discriminant analysis surprisingly shows a non-significant value, which may be due to the reference contamination in the beta frequencies since that measure is calculated from linked ears data. It is unusual for this measure to change so drastically in so short a time, particularly when there is still significant slow activity in lateral frontal and bilateral temporal locations. It is also possible that the initial TBI finding was higher than typical given the reference contamination from slow alpha activity in the previous recording.

CONCLUSIONS:

This client appears to have benefited from neurofeedback training and home training with respiration biofeedback. However, there remain areas of slow activity that may be important to resolve. The increase in the peak alpha frequency and the self-report of some experience of over-arousal may indicate a case of overtraining. They may require some additional training to resolve. As the client wishes to be finished with training, she will be encouraged to return for an additional follow-up session in 3 months to determine whether she has achieved a more balanced state. She will also be encouraged to return for further training if she experiences negative effects. Continued home training with the RESPeRATE breathing pacing device will also be encouraged.

DISCLAIMER:

This evaluation is not intended to diagnose any medical or psychological condition. It is also not intended to substitute for appropriate medical or psychological diagnosis and intervention. Please see your physician or mental health provider for appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Areas that show differences from expected values and the description of common symptoms associated with dysregulation in these areas are speculative based on current neuropsychological understandings. Descriptions may not apply to this client, and any suggested findings may need to be confirmed through other testing.

PATIENT EXAMPLE B

PATIENT INFORMATION

| Name: Client B | Date: 02/20/2014 |

| Exam#: Client B 10001 | Ref. By: Self |

| Age: 57.51 | Test Site: MNI |

| Gender: Male | Handedness: Left |

RECORDING

| Analysis Length: 01:42 | Ave. LE Split-Half Reliability: 0.98 |

| Ave. LE Test-Retest Reliability: 0.94 | Eyes: Closed |

MEDICATION: None noted

HISTORY: Client B presents with a diagnosis of traumatic brain injury (TBI). His history is significant for multiple head injury events associated with high school and college football. During his college football career, he reports one significant injury from helmet-on-helmet impact to the left lateral frontal area with a period of loss of consciousness for approximately 10 minutes, some confusion, and dizziness immediately following. He reports returning to the game in the second half after sitting out for the rest of the first half. He describes lingering symptoms through the following summer, following graduation, and states he hasn’t played football since. The symptoms faded with time, and though he never felt that he was back to his “normal self,” he became a successful businessperson.

He reports persistent depression with a lack of motivation. He finds it a great struggle to function in his day-to-day activities. He also mentioned that he has a “temper” and that this has cost him several relationships. He is currently divorced from his 3rd wife and feels his mood regulation problems are mostly responsible for these problems.

Symptoms endorsed include depression, headaches, feelings of loneliness, memory problems, occasional dizziness, mild to moderate general anxiety, some fear or panic experiences, difficulties with sequential processing, emotional sensitivity, some social discomfort, problems falling asleep and restless sleep, slow processing and slow response, poor reading comprehension, difficulty understanding concepts, and a lack of feelings of well-being.

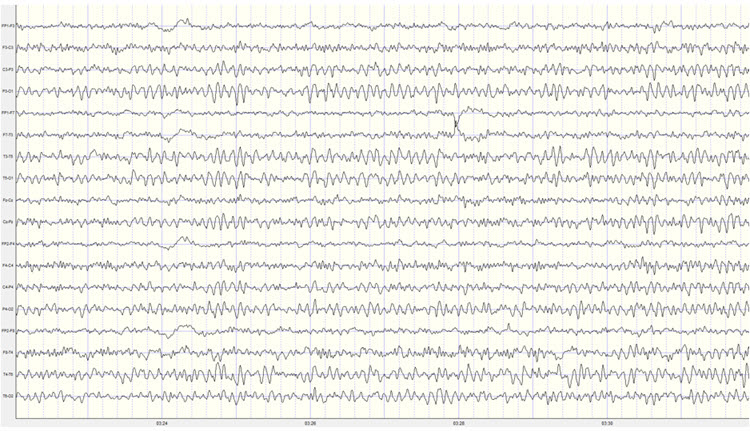

VISUAL INSPECTION OF 19-CHANNEL EEG:

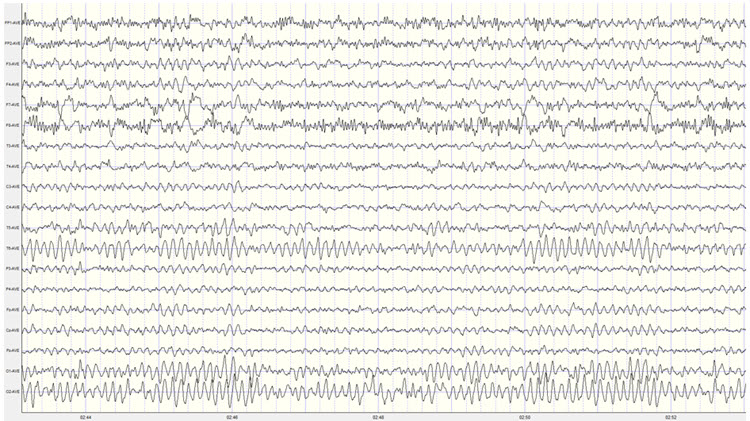

EYES-CLOSED CONDITION

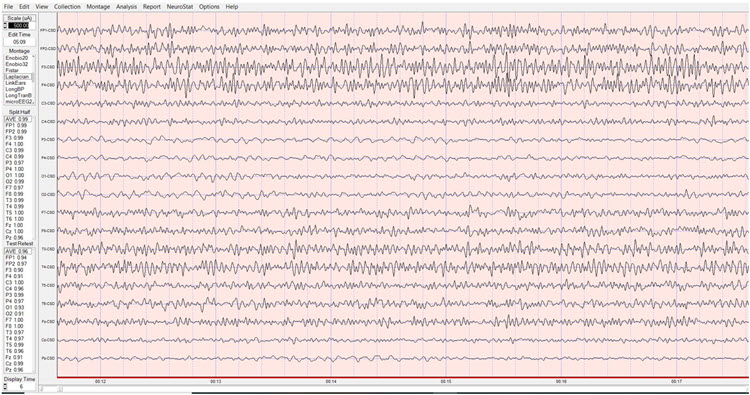

Longitudinal Bipolar Montage – this is a good quality recording with moderate eye movement artifact and only intermittent movement and EMG artifact. There are no discernable mains or equipment artifacts.

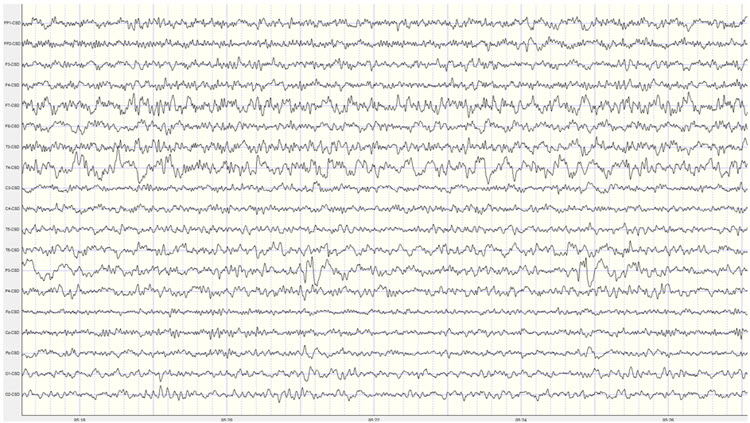

Caption: Example of Eyes-Closed EEG in Longitudinal Bipolar Montage – Scale 50 µV 1st Recording

The longitudinal bipolar montage shows a clearly defined posterior rhythm in derivations including temporal, parietal, and occipital electrodes. The frequency of the posterior rhythm appears to be somewhat inconsistent and ranges from 8-10 Hz. Amplitudes are generally in the 10-15 µV range with bursts up to 40 µV, occasionally exceeding 55 µV.

There is a clear pattern of slow activity in left lateral frontal derivations that include the Fp1-F3, Fp1-F7, F7-T3, and T3-T5 electrodes. There is also what appears to be a corresponding area of slow activity in the right temporal and temporal-parietal derivations. There is beta activity frontally in the 15-20 Hz range.

There is a period of apparent light or stage one sleep in the middle of the recording, interspersed with brief awakenings. The sleep EEG shows occasional vertex sharp waves but no other sleep characteristics. This pattern resolves, and Client B returns to an awake eyes-closed state for the rest of the recording.

The average reference montage also shows a well-developed posterior rhythm with the maximum voltage in the O1 and O2 electrodes, with additional posterior rhythm activity at T5, T6, P3, and P4. The voltage at T6 is nearly as high as in occipital sensors. The frequency continues to fluctuate between 8-10 Hz, and voltage is in the 10-20 µV range with bursts regularly exceeding 40 µV and occasionally 50 µV.

A pattern of slow activity is seen in this montage as well, with the clearest and most consistent activity in the left and central frontal, left central, right frontal, and right parietal and occipital areas, with frequencies varying between 2 and 4 Hz. There is also some alpha activity in frontal sensors, particularly at F3 and Fz.

The Laplacian montage also shows the posterior rhythm in occipital and parietal areas and shows a mixed pattern of activity at the T4 and T6 electrodes, with slower activity in the delta and theta frequencies mixed with alpha and beta frequencies. Left-sided slow activity is also seen.

The linked ears montage shows broadly distributed alpha activity suggesting reference contamination. The highest voltage of the posterior rhythm is in the occipital electrodes. There is alpha activity in the reference electrodes and a pronounced ECG artifact that will likely produce excess 1 Hz statistical values in the z-score analysis. This should be disregarded.

The sequential eyes-open, eyes-closed recording shows a typical alpha response upon eyes closing and appropriate alpha blocking upon eyes opening in this repetitive series of 15-30 second eyes-open and eyes-closed segments (see image below).

Caption: Example of Eyes-Open to Eyes-Closed EEG in Longitudinal Bipolar Montage – Scale 50 µV 1st Recording

EYES-OPEN CONDITION

Visual inspection of the eyes-open longitudinal bipolar montage recording shows appropriate attenuation of the posterior rhythm upon eyes opening.

Background activity shows mixed frequencies, including delta, theta, and beta frequencies. Beta frequencies are in the 20-30 Hz range. Alpha intrusions are also seen quite often in central-parietal, temporal-parietal, and parietal-occipital derivations. The slow patterns noted earlier are seen in frontal-central, central-parietal, and right-sided temporal-parietal and parietal-occipital derivations.

The average reference montage shows more widely distributed alpha activity throughout the recording, possibly due to the generalizing effect of averaging all electrodes for the reference. Otherwise, the findings are consistent with the long bipolar montage.

The Laplacian montage shows the alpha activity mostly in occipital areas and the mixed slow and fast activity in the T6 electrode noted in the eyes-closed recording.

The linked ears montage shows a generalized pattern of 9-10 Hz activity mixed with beta and theta frequencies.

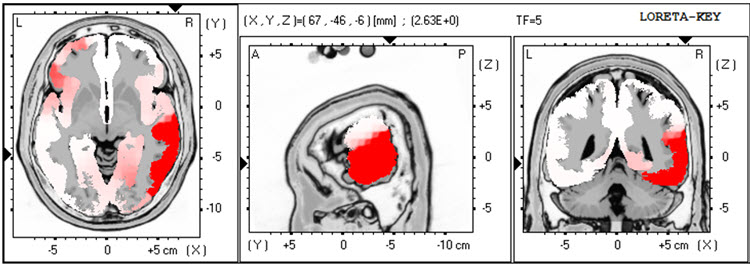

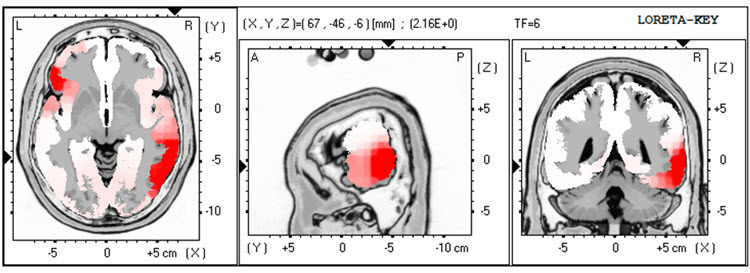

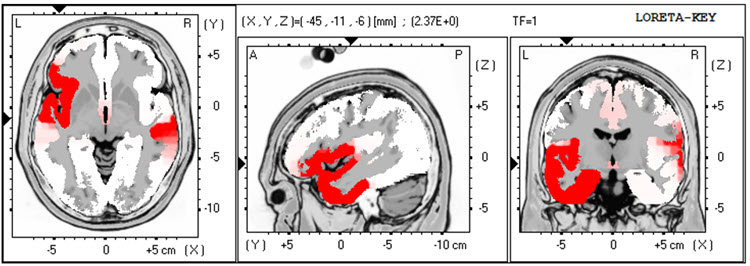

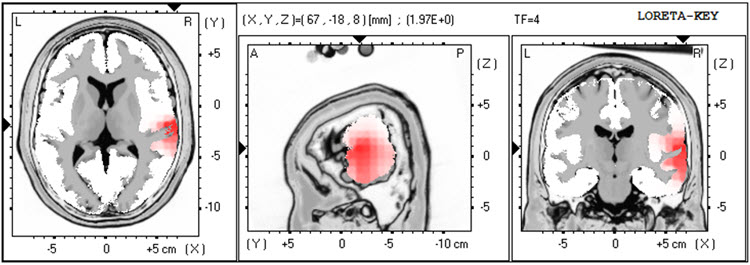

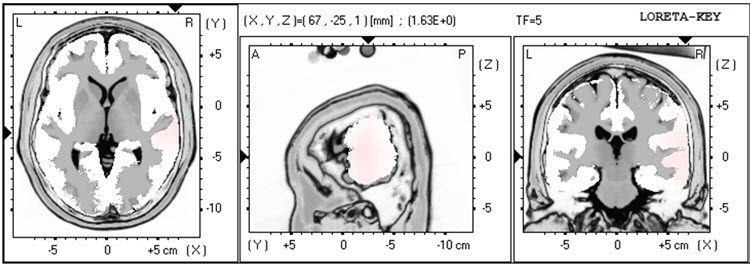

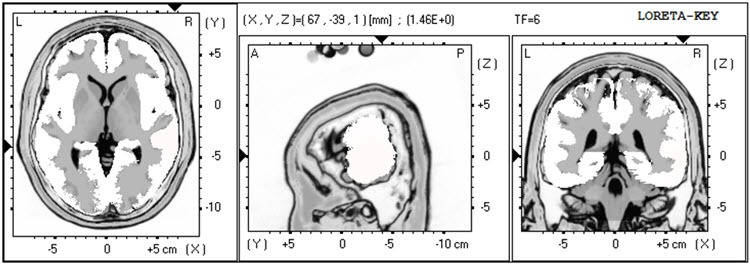

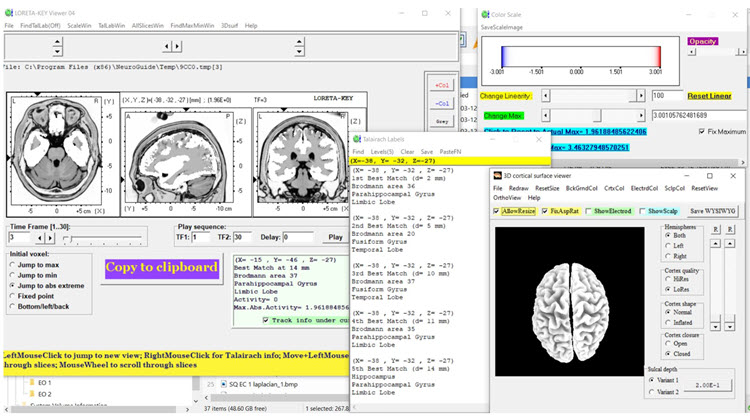

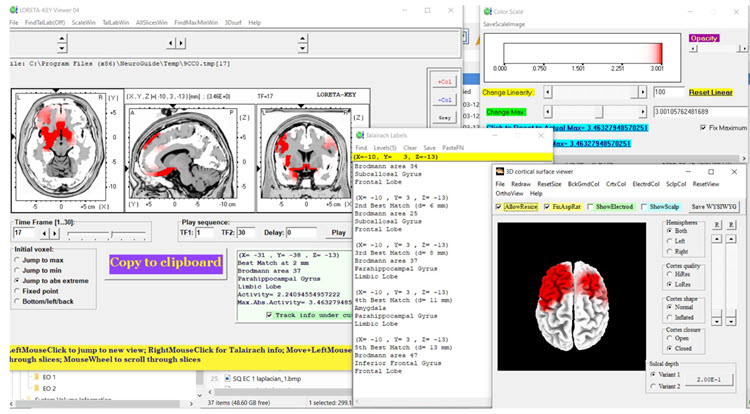

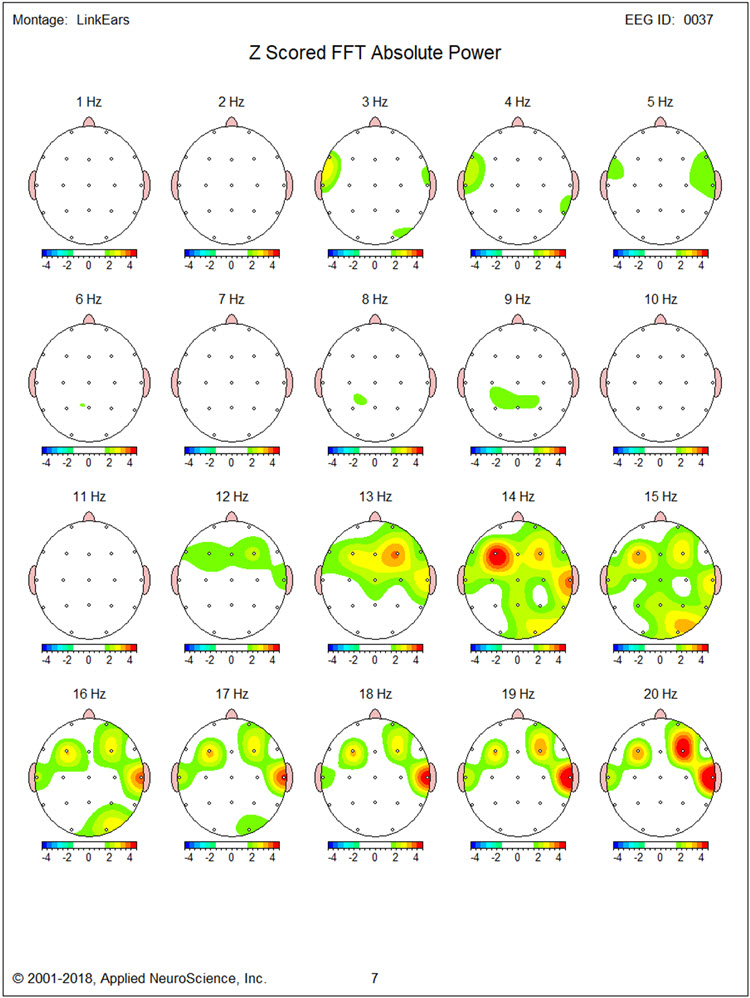

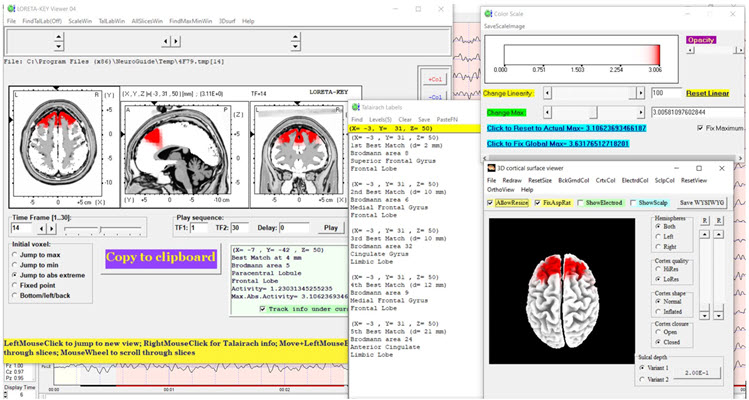

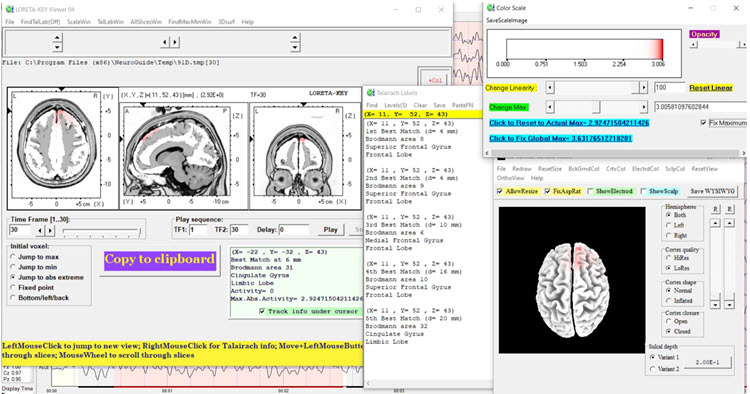

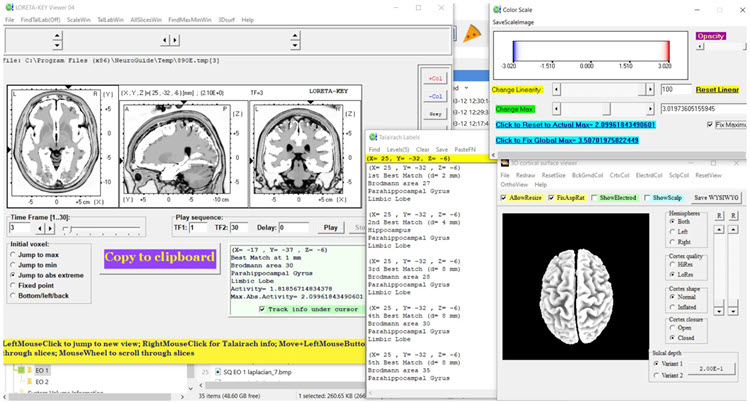

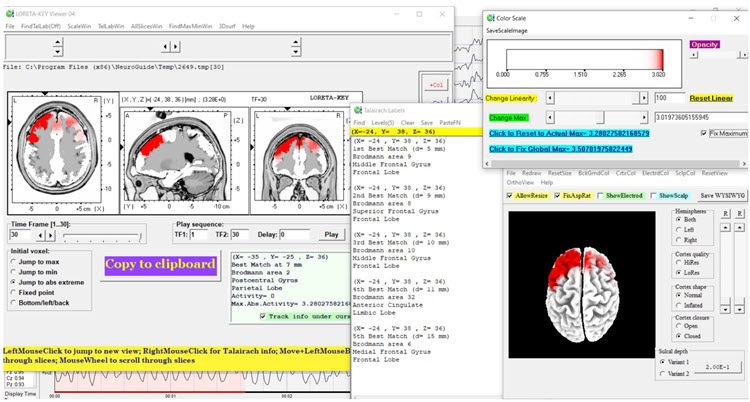

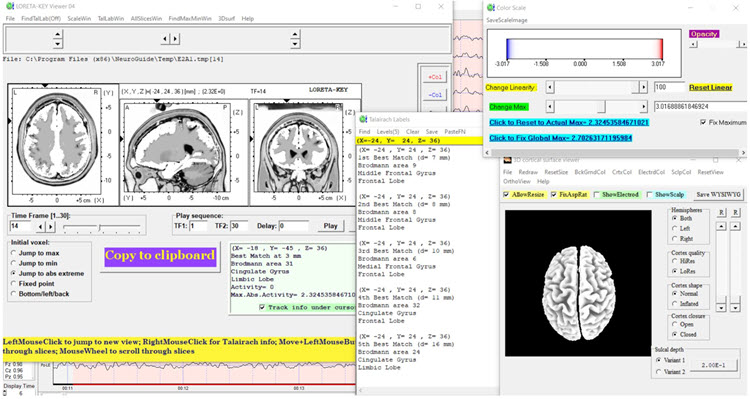

The LORETA analysis shows broadly distributed 1-Hz activity which is expected due to the ECG artifact, and also shows the lateralized left frontal and right posterior temporal/parietal areas as exceeding 2 standard deviations at 2-6 Hz, as well as right lateral frontal 9 Hz activity exceeding 2 standard deviations (see LORETA images below).

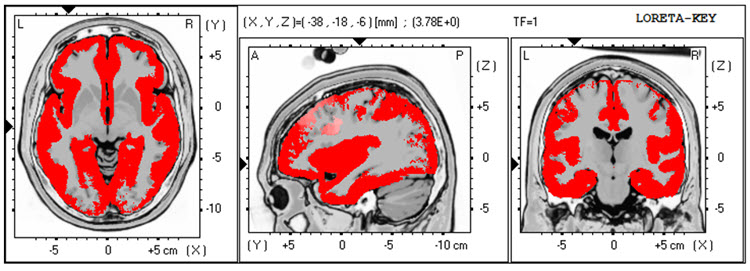

EC Recording 1 – LORETA 1 Hz – red = >2 SD

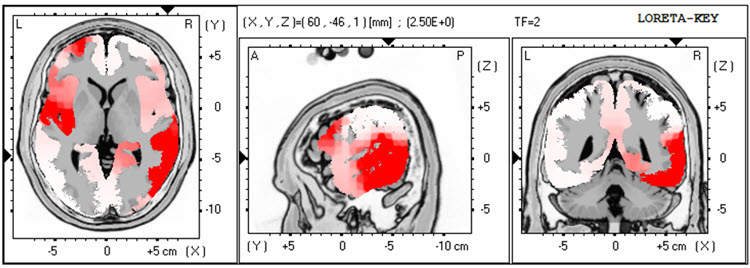

Caption: EC Recording 1 – LORETA 2 Hz – red = >2 SD

Caption: EC Recording 1 – LORETA 3 Hz – red = >2 SD

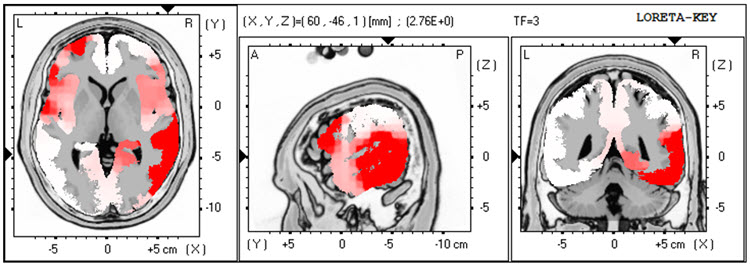

Caption: EC Recording 1 – LORETA 4 Hz – red = >2 SD

Caption: EC Recording 1 – LORETA 5 Hz – red = >2 SD

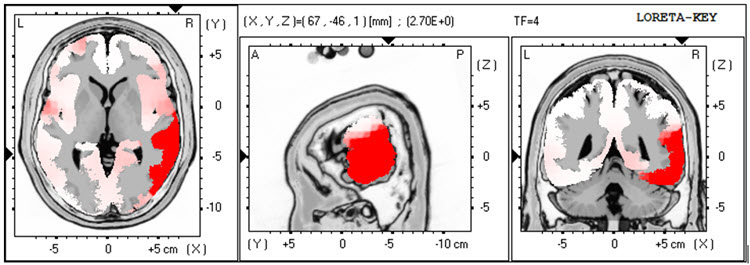

Caption: EC Recording 1 – LORETA 6 Hz – red = >2 SD

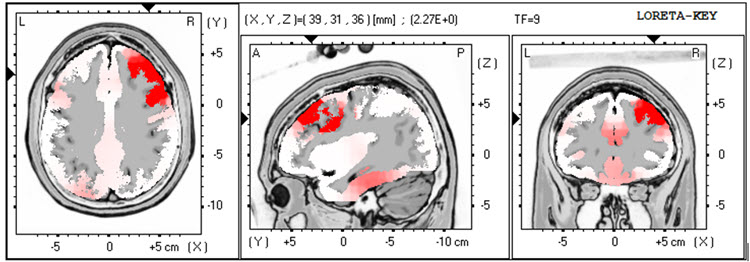

EC Recording 1 – LORETA 9 Hz – red = >2 SD

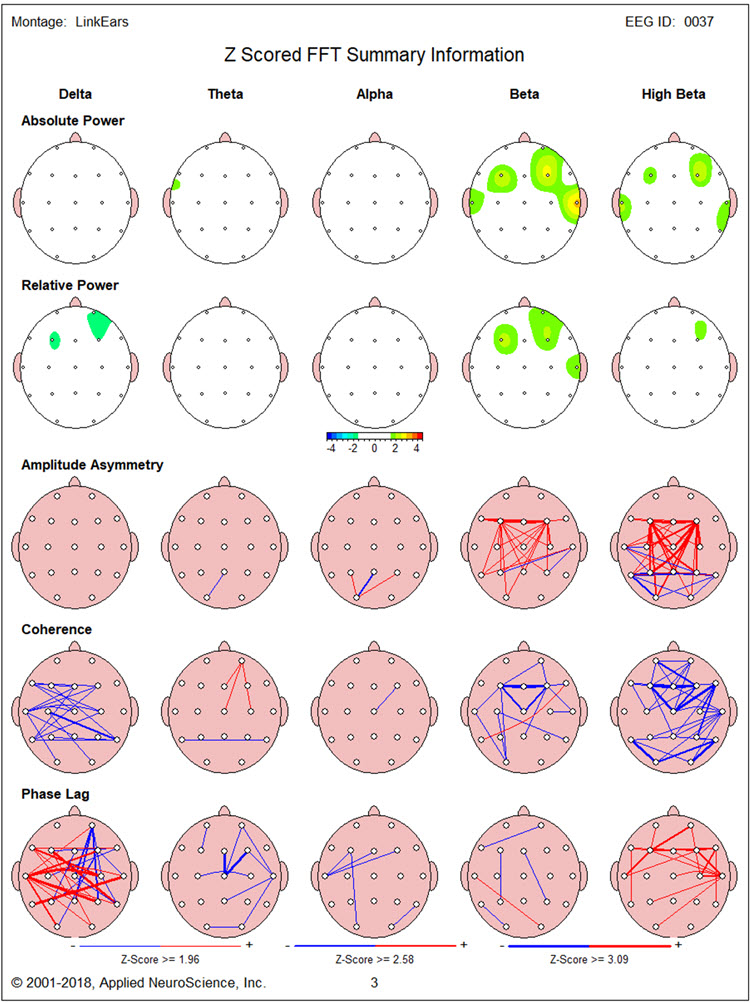

QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS:

The analysis of the absolute power topographic maps of the average reference montage of the eyes closed recording shows the maximum voltage of the 8-12 Hz frequency band to be at 9 Hz in bilateral occipital electrodes, followed by 10 Hz at approximately half the power. There is a clear right posterior temporal/parietal activity distribution from 2-15 Hz, reflecting the visual inspection findings.

The statistical topographic maps of the eyes closed average reference montage show broad distribution of 2.5-3 SD activity at 1 Hz, associated with the ECG artifact noted earlier, and this should be disregarded. There is excess activity in Fp1, F7, C3, Fz, F4, T4, T6, Pz, O1, and O2 electrodes from 2-3 Hz, with lesser, mostly right temporal and posterior excess from 4-5 Hz. The greatest deviation is at the F4, T6, and O2 electrodes exceeding 2.5-3 SD.

There is also excess bilateral frontal and left frontal/central and right parietal/occipital 9 Hz activity with the greatest deviation between F3, Fz, C3, and Cz. There are moderate excess occipital and right parietal 12-14 Hz activity and some 19-22 Hz excesses.

The peak alpha frequency is slightly slow but does not exceed -1 SD at any location.

The Laplacian montage shows the 1 Hz activity related to the ECG artifact. This montage shows the maximum deviation from 2-5 Hz at T6 with lesser deviations in the left lateral frontal, frontal, central, parietal and occipital areas. The excess 9 Hz is seen here, with some minimal 13-14 Hz activity in the right occipital and parietal areas.

The linked ears montage shows more distribution and greater deviation in most frequencies noted previously. Interestingly, the excess slow activity shows a much more lateralized presentation than was seen in the other montages. This may be due to reference contamination, and it could be coming from the area of the T4 and T6 electrodes, which are near the right-sided reference.

Coherence abnormalities are pronounced, but this is likely not reliable due to reference contamination in the linked ears montage.

Due to the reports of multiple impact injuries to the head, the Traumatic Brain Injury Discriminant Analysis was performed. It yielded a TBI discriminant score of -0.43, a TBI probability index of 80.0%, and a TBI severity index of 5.44, which is in the moderate range on a 0-10 scale, where z0 represents mild severity and 10 is severe.

CONCLUSIONS:

This client presents with multiple issues that may be related to the findings observed in this EEG recording. This may be particularly true of the slow activity seen in the left frontal areas and the presence of both slow activity in the right posterior temporal/parietal areas and higher than the typical amplitude of alpha activity in the same area. Also, the slowing of the peak alpha frequency, even though it is not statistically significant, suggests that working to normalize this frequency may improve his cognitive function.

RECOMMENDATIONS:

A course of neurofeedback training is recommended, and initial training will begin with 4 channel z-score training, rotating between a variety of electrode combinations, beginning with Fz, Pz, T3, and T4; followed by F3, F4 T5, and T6; followed by C3, C4, P3, and P4. Other protocols may be explored as training progresses.

SUMMARY OF CLIENT RESPONSES TO TRAINING:

Client B progressed through 25 sessions of neurofeedback training over the course of 15 months, generally averaging one session per week, with a decrease in frequency in the last half a year. He also utilized a home training device for heart rate variability training and an AVE device. Session training locations included 6 sessions of Fz, Pz, T3, and T4; 2 sessions of Fz, Pz, P3, and P4; 11 sessions of T5, T6, O1, and O2; 1 session of F3, F4, P3, and P4 – all 4 channel z-score training. He also received 2 sessions of 4 channel slow cortical gradient training and 3 sessions of C3 and C4 2 channel difference and sum training with variable reward frequency. Alpha-theta training was attempted on a few occasions, but he did not like it, so training was changed within the session to one of the protocols noted above.

He reports feeling significant improvement in his ability to focus and in his mood regulation. He is in a new relationship and states that his temper is much more manageable and that he has learned improved communication skills through couples counseling with his current significant other. He notes that he has more energy, his sleep has improved, and his cognitive function is also better. He occasionally has headaches though the intensity and duration have decreased markedly. He feels he has resolved his presenting concerns and wishes to have a follow-up EEG recording to see if the assessment will show the changes that he is experiencing.

SECOND RECORDING

| Analysis Length: 01:32 | Ave. LE Split-Half Reliability: 0.97 |

| Ave. LE Test-Retest Reliability: 0.94 | Eyes: Closed |

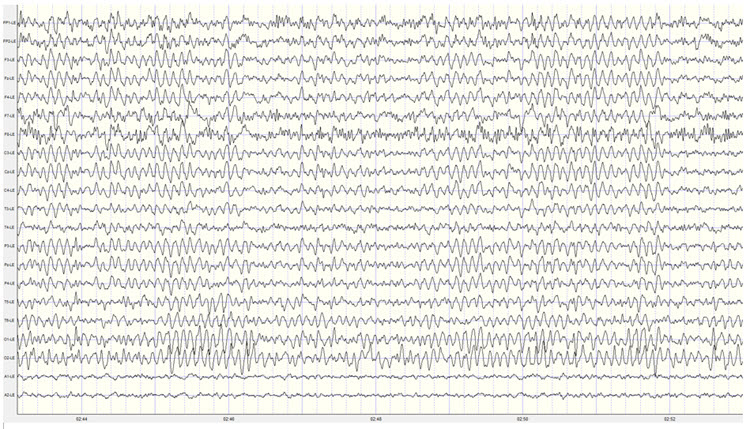

VISUAL INSPECTION OF FOLLOW-UP 19-CHANNEL EEG:

EYES-CLOSED CONDITION:

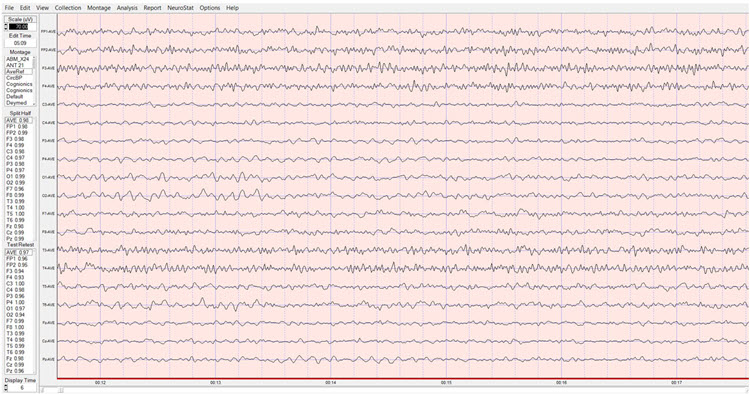

Visual inspection of the 19-channel EEG in the eyes closed condition using the longitudinal bipolar montage shows a good quality recording with typical eye movement artifact and some brief episodes of what appears to be drowsy or light sleep activity. There is no evidence of EMG artifact, mains, or other exogenous artifacts in this recording. This recording appears to be significantly lower in amplitude than the previous recording.

Caption: Example of Eyes-Closed EEG in Longitudinal Bipolar Montage – Scale 50 µV 2nd Recording

A well-developed posterior rhythm is seen primarily in parietal and occipital derivations with some temporal-parietal and central-parietal derivations. There is some spindling beta activity seen with the frequency of 20-25 Hz. This occasionally occurs in frontal-central derivations. There is some slow activity in the left lateral frontal areas and the right posterior temporal/parietal areas. The posterior rhythm shows a consistent frequency of 9 Hz with a well-developed sinusoidal rhythm and amplitudes generally in the 20-30 µV range, with occasional bursts exceeding 30 µV. The posterior rhythm appears quite symmetrical between left and right locations, with the maximum voltage in parietal-occipital derivations.

The average reference montage shows more generalized alpha activity, possibly suggesting some distribution associated with the averaging method of the montage. The posterior rhythm is seen with the highest voltage at O2 and O2, closely followed by T6. The frequency remains at 9 Hz and is quite consistent, with amplitudes in the 20-30 µV range occasionally exceeding 30 µV. Again, the periods of possible drowsiness or light sleep are seen that occur quite infrequently and do not persist for any length of time.

The Laplacian montage also shows the posterior rhythm and occipital sensors and right parietal T6 and lateral parietal P3 and P4 locations. There is beta activity in the 15-25 Hz range in frontal and central sensors, and there is some slow activity in left-sided frontal and right-sided parietal areas.

The linked ears montage shows widespread alpha activity in all sensors, including the bilateral reference channels, and therefore reference contamination is present.

When viewed in the longitudinal bipolar montage, the repetitive eyes-open and eyes-closed segments show a clear alpha response upon eyes closing and immediate alpha blocking upon eyes opening (see example below).

Caption: Example of Eyes-Open to Eyes-Closed EEG in Longitudinal Bipolar Montage – Scale 50 µV 2nd Recording

EYES-OPEN CONDITION:

Visual inspection of the eyes-open longitudinal bipolar montage recording shows appropriate attenuation of the posterior rhythm with typical eyeblink and eye movement artifact. There is beta activity in the 15-25 Hz range in all electrode derivations. There are occasional alpha intrusions into the eyes-open recording, although these are infrequent and do not persist.

The average reference montage shows essentially the same findings though there is some persistent mixed frequency activity in the T4 and T6 electrodes, with alpha and beta frequencies occurring simultaneously.

The Laplacian montage shows higher amplitude mixed frequency activity at the F7 electrode and T4 and T6 electrodes. This activity includes a pattern of activity at approximately 8-9 Hz, 13 Hz, and also at 23 Hz.

The linked ears montage again shows broadly distributed activity that is quite synchronous and likely represents reference contamination.

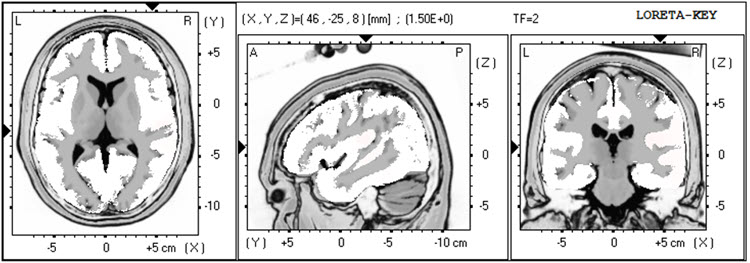

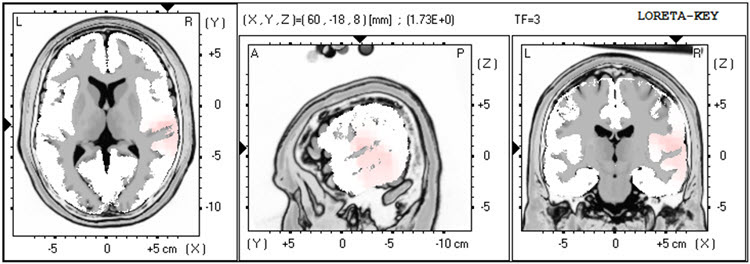

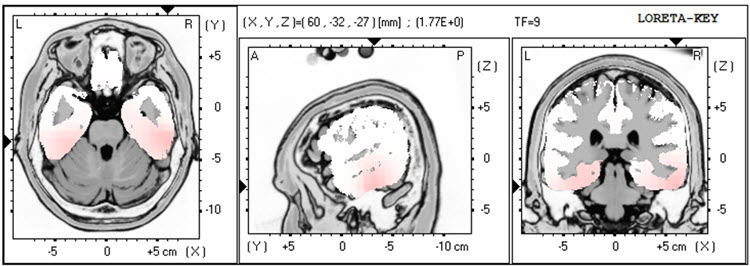

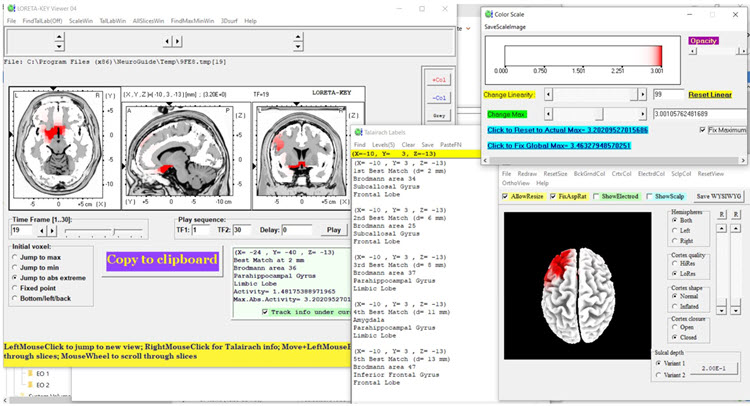

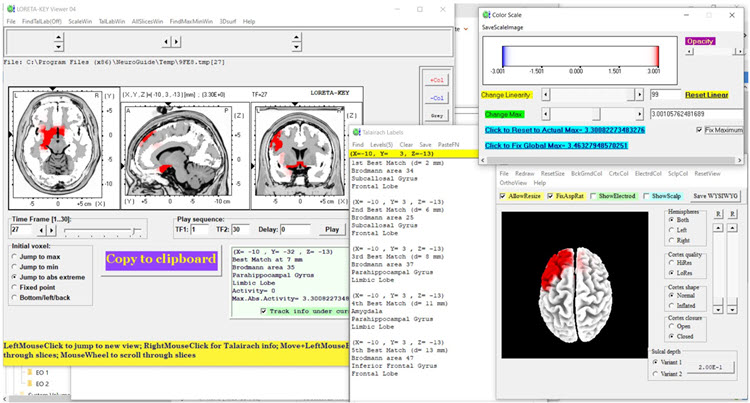

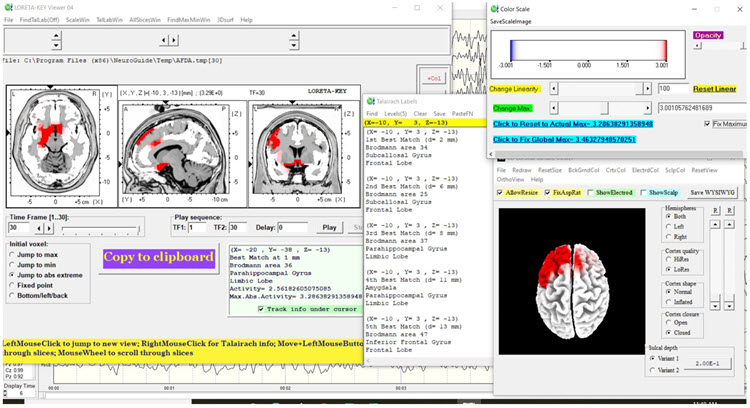

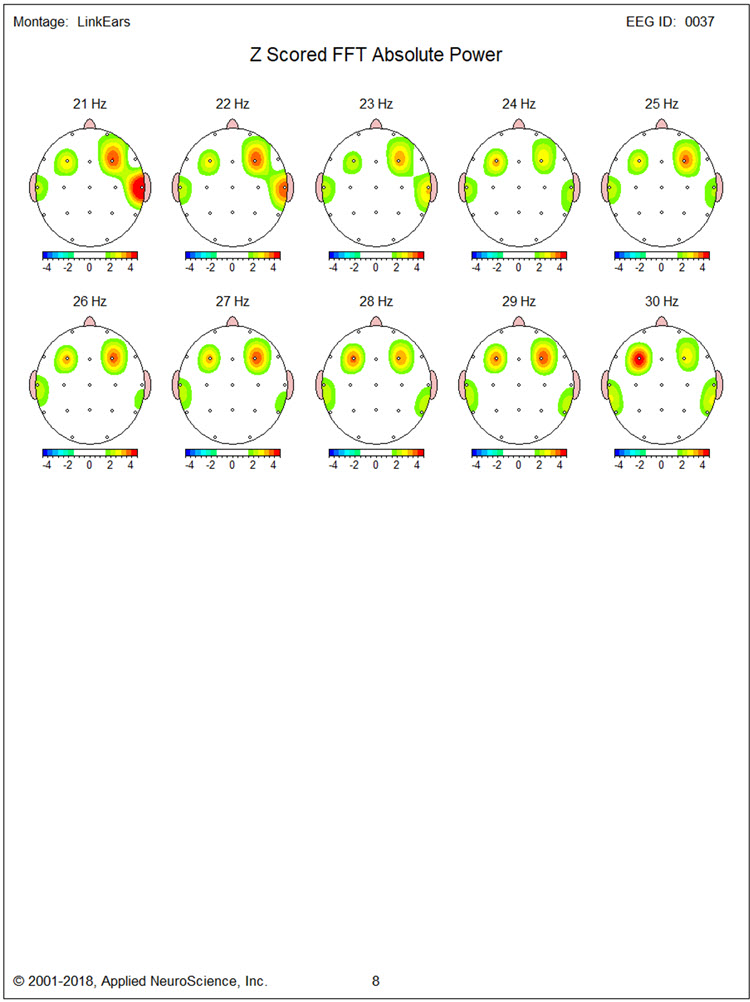

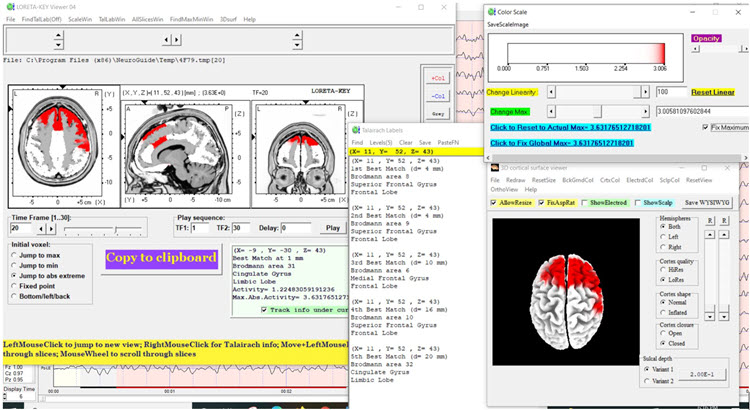

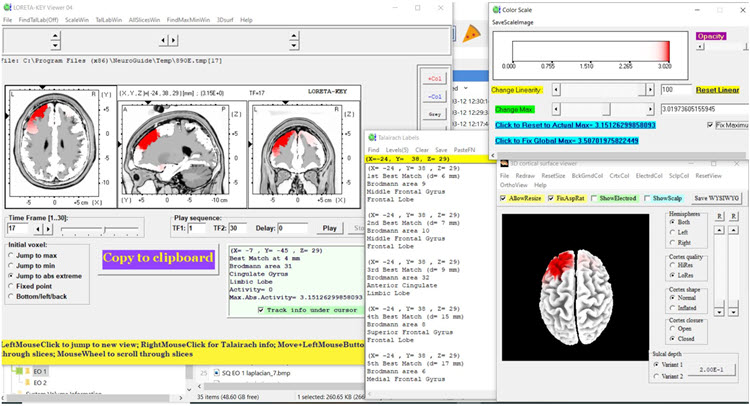

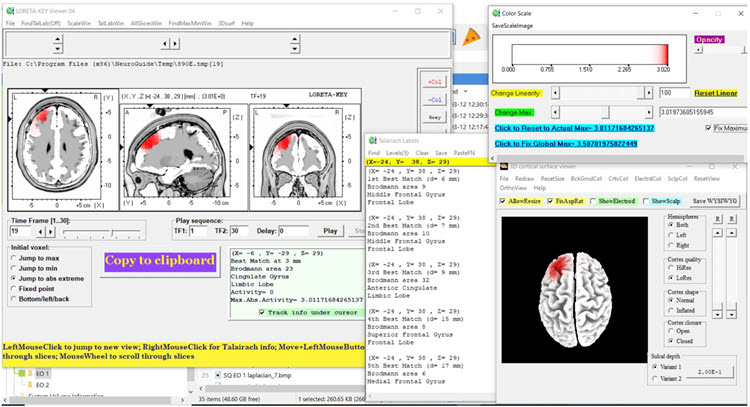

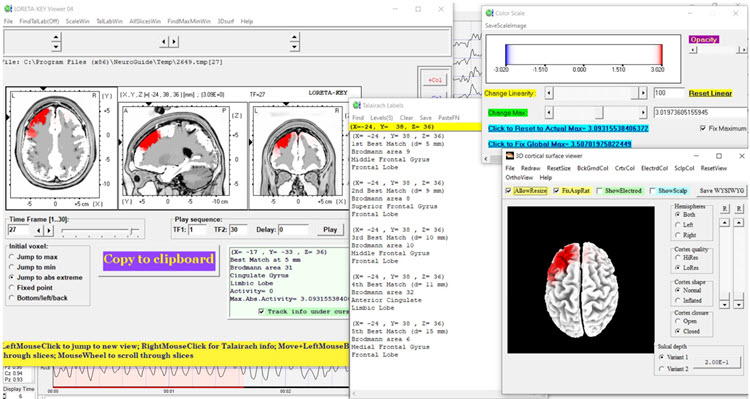

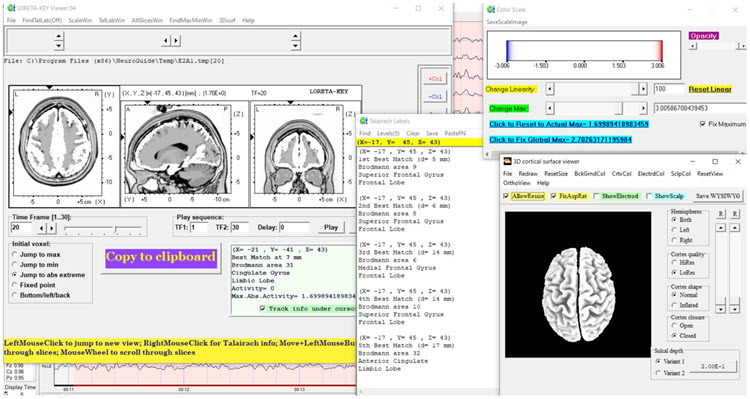

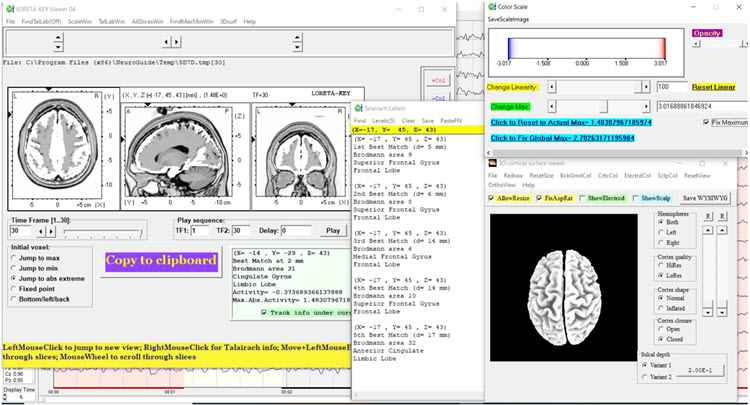

LORETA analysis of the follow-up 19-channel EEG recording shows the same lateralization exceeding 2 standard deviations seen in the previous recording, but in this case, only seen at 1 Hz in the left lateral frontal and right temporal areas. This activity is not seen at 2-3 Hz, and there is an area of excess activity in the right temporal area at 4 Hz, again exceeding 2 standard deviations. There is minimal excess activity at 9 Hz in the bilateral inferior temporal, fusiform, and parahippocampal gyri. (See LORETA images below).

Caption: EC Recording 2 – LORETA 1 Hz – red = >2 SD

Caption: EC Recording 2 – LORETA 2 Hz – red = >2 SD

Caption: EC Recording 2 – LORETA 3 Hz – red = >2 SD

Caption: EC Recording 2 – LORETA 4 Hz – red = >2 SD

Caption: EC Recording 2 – LORETA 5 Hz – red = >2 SD

Caption: EC Recording 2 – LORETA 6 Hz – red = >2 SD

Caption: EC Recording 2 – LORETA 9 Hz – red = >2 SD

Analysis of the eyes-closed average reference montage absolute power topographic maps from the 2nd recording shows the maximum voltage in the 8-12 Hz frequency band at 9 Hz, with a power value of approximately two-thirds seen in the previous recording.

The statistical analysis of the absolute power topographic maps in the average reference montage of the eyes-closed recording shows excess activity exceeding 2 standard deviations at F7 and T4, with lower levels of deviation at Fp1, F8, Cz, C4, and T6. Additional activity areas exceed 2 standard deviations at 2 and 3 Hz at T4 and T6. There is excess activity in the 1-1.5 standard deviation range in the left frontal and central areas and the bilateral posterior, including T6, and finally, a small area of excess activity at 13 Hz at T6 and O2. These findings are significantly diminished from the previous recording and likely reflect behavioral experience changes. Some areas of excess activity from 21-23 Hz appear associated with the Fz electrode, which will be evaluated further in other montages.

The peak alpha frequency remains within the normal range in all locations and only exceeds a -1 standard deviation at the T4 electrode location.

The Laplacian montage essentially shows the same findings except for the right temporal/parietal area activity extending up to 5 Hz and the excess 9 Hz activity in more circumscribed locations. Also, the excess 21-23 Hz activity is associated with the Cz electrode, and therefore that seen in the average reference more broadly distributed is almost certainly due to reference contamination from the averaging mechanism in that montage.

As expected, the linked ears montage shows a broadly distributed excess activity pattern from 6-15 Hz across frontal areas reflecting the reference contamination noted earlier. Otherwise, it also shows the in priest lateral reality seen in the previous recording from the left lateral frontal to the right temporal, possibly related to reference contamination.

The comparison to the previous traumatic brain injury discriminant analysis shows very similar findings, with the TBI discriminant score at -0.03, the TBI probability index at 90%, and the TBI severity index at 5.42, which is similar to that seen previously.

CONCLUSIONS:

It appears that the results are substantially improved and support his self-report of improvement in multiple areas of functioning. Client B was encouraged to return for further sessions if he noticed an increase in problematic symptoms. He was also encouraged to continue heart rate variability training at home and continue using the audiovisual entrainment device (AVE) at home.

PATIENT EXAMPLE C

HISTORY

TR is a 41-year-old man injured in a car collision two years earlier. At the time, he sustained a mild concussion and soft tissue injuries associated with the inability to perform his work as an independent construction contractor. He gradually returned to part-time work.

He was referred because of anger and aggressive behavior problems that were directed primarily to his insurance provider. TR considered that his insurer had not provided sufficient benefits immediately after his injury and that the insurer continued to withhold the benefits he deserved. In addition to ruminating about conflict with the insurer, TR was much more likely to feel and express anger to day-to-day conflicts (e.g., traffic). TR described his experience of anger as his “brain being on fire.”

In addition to feelings of anger and aggressive behavior, TR also reported that his head felt “heavy and full” most of the time, and he had difficulty falling asleep. He denied any thinking deficits, however. These emotional, behavioral, and somatic symptoms developed slowly following the traffic collision but appeared to worsen his pre-injury condition concerning anger and aggression. TR reluctantly admitted that his anger, though justified regarding his insurer, was interfering with his ability to work with his construction teammates.

TR’s only medication was low-dose amitriptyline for sleep. He did not drink alcohol. Previous medical history was significant only for a construction-related dislocated shoulder. TR had no history of treatment for psychiatric, alcohol, or drug problems. He had graduated from high school before working full-time in home and agricultural construction. TR had no history of legal difficulties. A paralegal assisted with the traffic collision insurance claim. However, he did have a significant history of conflict with his father, from whom he was estranged. TR visited his mother regularly. TR and his wife had no children.

TR is the younger of two siblings, having an older sister who lives some distance from TR. His family health history included his father’s alcoholism and his mother’s congestive heart failure. His father had not completed high school and worked as a builder of barns and other types of agricultural buildings.

ASSESSMENT