Treatment Demonstration

Client education is the foundation of neurofeedback training (NFT). Professionals can explain core concepts, provide a road map of the NFT process, clarify their respective roles in the training process, and summarize clinic policies. The initial session provides an opportunity to address misconceptions about how NFT works and what the equipment does. Written informed consent is a contract that codifies the terms of your relationship with your client.

Applicants must develop competence in EEG equipment set-up and operation. Demonstrations and hands-on training in didactic training programs provide many attendees' first introduction to instrumentation and software. The mentorship relationship builds on this foundation as applicants practice their growing skills on themselves and family members/friends. BCIA's Neurofeedback Essential Skills List provides a detailed checklist of the competencies that applicants need to master. This document serves as the blueprint for all our Demonstration units.

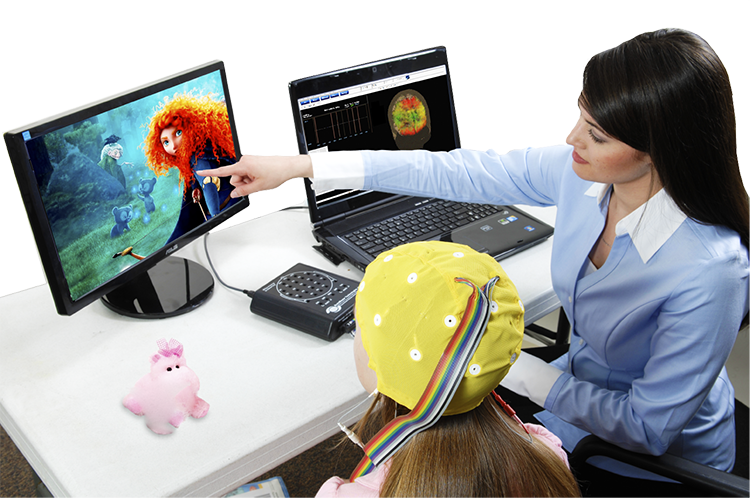

EEG equipment literacy requires that applicants understand how to measure the scalp, identify International 10-20 System sites, and attach electrodes. They must understand what a normal raw EEG looks like and gain experience in creating and controlling artifacts so that EEG measurements and brain maps based on them are valid. Finally, applicants must learn to recognize abnormal EEG waveforms and to distinguish them from benign activity. Graphic © BrainMaster Technologies.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit covers VIII. Treatment Implementation- F. Full Neurofeedback Session Demonstrations.

This unit covers the International 10-20 System, 19-channel EEG recording, NewQ Assessment with Live Demonstrations, and a Demonstration of a Full Neurofeedback Session.

Please click on the podcast icon below to hear a full-length lecture.

International 10-20 System Demonstration

This demonstration covers the international 10-20 electrode placement system for EEG. It begins with an overview of graphic representations of the 19 scalp locations, the coordinate designations, and how the skull is measured to identify the correct locations. This is followed by live demonstrations of the basic measuring techniques and a standard sensor application for two separate EEG recording channels.

Video © J. S. Anderson.

19-Channel EEG Recording

Please click on the podcast icon below to hear a full-length lecture.

The next movie demonstrates a 19-channel BioTrace+/NeXus-32 display of EEG recording © John S. Anderson.

NewQ Assessment with Live Demonstrations

This is a demonstration of the clinical assessment known as the NewQ. Like other clinical assessments such as the ClinicalQ from Paul Swingle, PhD and New Mind Maps from Richard Soutar, PhD, the NewQ utilizes an understanding of the EEG behaviors associated with certain tasks and makes interpretations based upon EEG information from standard literature sources and the clinical experience of the developer of the assessment.

This video begins with a discussion of the NewQ as it is administered, how to identify and minimize artifact and the types of tasks to be performed by the client. This is followed by an abbreviated administration of the assessment, using a non-client volunteer and then a view of the screens and the process of collecting the data using a saved session. This is followed by a demonstration of the data analysis and finishes with a discussion of the sample results.

This is just one example of these types of assessment tools. Neurofeedback Tutor also contains videos of 19-channel recordings and the use of a normative database.

Finally, Neurofeedback Tutor also contains discussions of some of the standard training protocols that can be used once the clinical assessment has been performed.

Video © J. S. Anderson.

FULL NEUROFEEDBACK TRAINING SESSION DEMONSTRATION

Session Description

The following video shows a demonstration of a basic neurofeedback session. This is a fictional example of session 11 in a sequence of training sessions with a fictional client, played by Cortney Amundson of Mindful Restoration, using a single EEG channel, training one location (Cz) in the center midline in a referential (monopolar) montage with an ear reference (Cz-A2). The training protocol involves rewarding increases in 12-15 Hz EEG activity – often called the sensorimotor rhythm or SMR – over the sensory/motor cortex while concurrently inhibiting 4-8 Hz theta and 22-36 Hz high or fast beta.The client (Sharon) relates her responses to the previous session, in this case, a negative reaction to a right-side training protocol (P4-T4 uptraining 8-12 Hz) that has shown positive responses in other clients. Also, the previous session included a short (5 minutes) training segment at Fp1, rewarding an increase in 15-18 Hz beta to address self-reported depression. She reports a headache following the session and difficulty sleeping with gradual improvement until getting a good night’s sleep the night before this training session.

This is an example of the type of negative effects clients will sometimes experience from the training. This is not a typical occurrence, but practitioners need to be prepared often enough. The first thing to do is to accept that the client is relating an accurate experience. Validating the client and recognizing the potential for negative effects is important both for the client and the clinician. Too often, clinicians will discount or reject the possibility of negative effects. This attitude is harmful to the therapeutic relationship as the client will be less likely to trust the clinician if their experience is rejected or denied. This rejection of accurate reporting will also interfere with the clinician’s ability to evaluate the training effect, particularly if the client becomes sensitized to only providing positive reports.

In the video, the clinician acknowledges the client’s report and suggests that the effect of one or both training protocols may have contributed to the negative effects and offers additional information about the possible effects, particularly the possibility of over-activation from the left frontal beta training. This elicits further information from the client that she “had more energy” following the training.

Finally, a return to the previous, successful Cz, SMR training approach is discussed. The possibility of shifting to direct z-score and database training is introduced as a possible future intervention. These brief comments and the discussion as a whole demonstrate the collaborative nature of the client–clinician relationship. Bidirectional communication and discussion are essential. Clinicians must always remember that all biofeedback, including EEG biofeedback or neurofeedback, is training, not treatment.

The clinician fosters collaboration with the client to reach the client’s goals, which requires an egalitarian relationship rather than a top-down, practitioner-to-recipient approach. At its best, neurofeedback training involves client education regarding their nervous system while at the same time educating the nervous system directly. Ideally, the clinician also approaches the process from an educational perspective, learning from the client and observations of the process, being alert for mistakes (hopefully few), acknowledging those mistakes, and learning from them.

Relying on evidence-based training approaches helps minimize negative effects. This means that a thorough understanding of the research and clinical literature is essential for the clinician to understand the expected effects of each type of training and what to do when unique, individual client responses occur. In the example in the video, the possible negative effects of left frontal beta training can include over activation of the central nervous system, possibly resulting in physiological symptoms of pain, headache, and sleep problems, as the client hasn’t learned to self-correct the overarousal condition. Further training in more rhythmic patterns such as SMR or alpha has been shown to produce a calming effect in most clients, as we see in this example in the video. This is just one example of the possible results of a training approach and a possible correction of that effect.

Note that the client felt like taking more deep breaths, leading to a tingling feeling in her body. This may reflect some overbreathing behavior and suggests further biofeedback training, specifically respiration and heart rate variability training (HRV), which would also provide the client with further resources for self-regulation if they experience states of CNS over-arousal in the future.

The suggestion to shift to z-score training may provide a better approach due to its self-corrective nature. When training in real time to a normative database, a shift in any trained measures away from zero standard deviations (SD) indicates movement in an undesired direction. The feedback will immediately respond to this change by reducing the reward, encouraging a shift back towards typical functioning.

Feedback Approach

The feedback provided to the client was primarily proportional feedback with a single, event related tone. This means that all the other feedback changed constantly in response to the client’s EEG activity. The flower opens and closes in direct response to the SMR amplitude. The flower opens more when SMR amplitude increases and closes when amplitude decreases. The music also follows a similar pattern, increasing in volume for increases in SMR amplitude and decreasing when amplitude decreases. The high beta inhibit is reflected in the sound of ocean waves in the background, that become louder when high beta amplitude decreases (inverse setting). This rewards a decrease in high beta amplitude without interrupting the training.When start/stop inhibit approaches are used, they can interrupt the training experience to a certain degree, particularly when doing more relaxation oriented training. Research has shown better outcomes for biofeedback learning with proportional feedback compared to binary feedback (on/off) (Colgan, 1977; Strehl, 2014).

In this case, the single event related or binary reward feedback signal is a "bong" sound that occurs each time the SMR amplitude exceeds threshold for at least 250 ms and continues sounding as long as amplitude remains above threshold. This rewards not only an increase in amplitude but reinforces the client’s ability to maintain longer bursts of 12-15 Hz activity above threshold.

An additional feedback sound occurs when the 4-8 Hz theta amplitude exceeds the threshold. That activates the sound of birds chirping, which alerts the client to such increases, often associated with drifting attention. However, this feedback signal doesn’t stop or inhibit the other feedback signals and allows training to continue.

If this were a client with issues of under-arousal and inattention, other feedback approaches would be employed that would provide more structured, event-related feedback, with start and stop settings and other tools to encourage alertness and maintenance of attention. Also, more clearly defined goals, possibly with a “points” counter may be employed to further encourage participation with the possibility of points accumulation leading to additional rewards. However, this fictional individual is overly attentive, anxious, driven, and achievement-oriented, so a more fluid and less goal-directed feedback approach is often more effective.

Because this is simply a demonstration video, it is truncated just to show examples of the type of conversation between clinician and client that occurs at regular intervals during training. The clinician checks in with the client to determine whether the training has the desired effect. Other measures are often monitored concurrently, and examples of such monitoring include peripheral skin temperature and galvanic skin response (GSR). These measures can alert the clinician to signs of distress in the client such as a decrease in finger temperature or an increase in sweat on the palm, prompting a check-in to determine the cause of such distress. The clinician also monitors the high beta and theta signals to determine if there is an increase in arousal, possibly reflecting anxiety, or a decrease in arousal, possibly reflecting fatigue or a lapse in attention, again prompting a check-in with the client.

Working with an experienced client, who understands the feedback and has learned to report symptom changes during the session, it is often not necessary to interrupt the training with conversation or check in with the client. This also promotes independence and individual responsibility on the client's part and reinforces the self-training nature of the process.

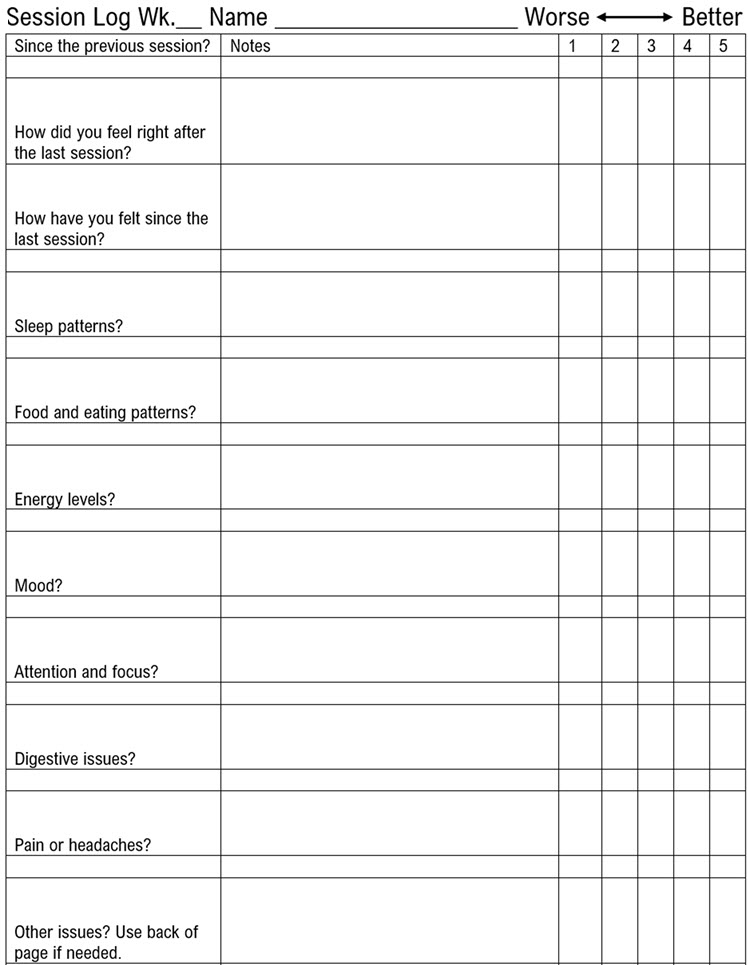

There would likely be more discussion of emotional/psychological material during an actual clinical session. There would also likely be more questions from the client about why the negative effects occurred. The client’s life experiences would be discussed, such as any changes in relationships, feedback from family members, friends and/or coworkers, and their general energy, mood, and other perceptions. For brevity, these types of discussions were not included in the video, although the between-session tracking questionnaire the client completed between each session is included below.

There are many between-session symptom tracking methods. Some clinics set up online tracking forms, and although this can introduce security and privacy issues, it is often more convenient for the client and the practitioner. Some tracking forms are highly structured and detailed. The one below is intentionally limited to encourage clients to use their own words to describe their responses. The clinician will then probe for more detailed information during the session. This type of form is also more likely to be completed by most clients, whereas some more involved forms will not be completed because they take more time than many clients are willing to devote to the process. Some clinicians will have a range of forms to fit the client.

Video © J. S. Anderson.

CONCLUSION

This client example demonstrates a basic training session utilizing a simple intervention that has a long history of use in the field of neurofeedback and which has been the subject of several published studies (Arns et al., 2009; Campos da Paz et al., 2018; Gevensleben et al., 2013; Mohammadi et al., 2015; Rajabi et al., 2019). These studies have demonstrated improved results on various measures in different populations, from children to older adults. Research models have included comparisons with known efficacious interventions such as medication management of ADHD, sham feedback, and general outcome measures studies.

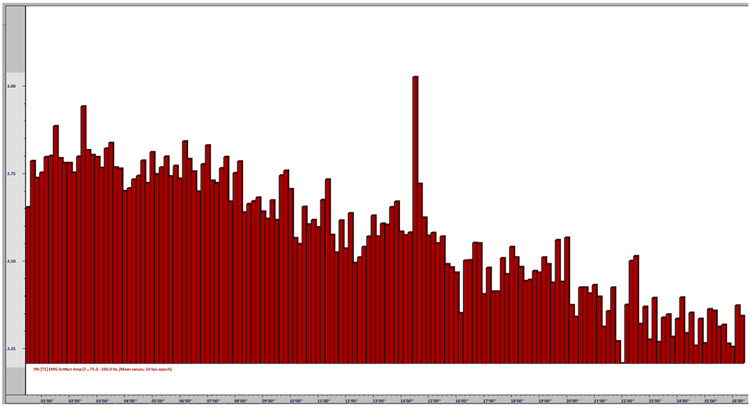

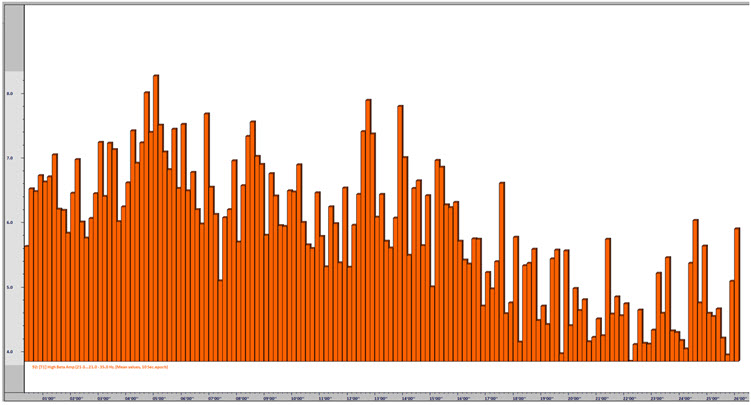

In the demonstration, the client reports “feeling more relaxed.” This subjective self-report corresponds with the results shown below that indicate an increase in SMR voltage across the session, a decrease in EMG artifact and fast beta activity, and a stable or slightly decreasing value for the theta inhibit.

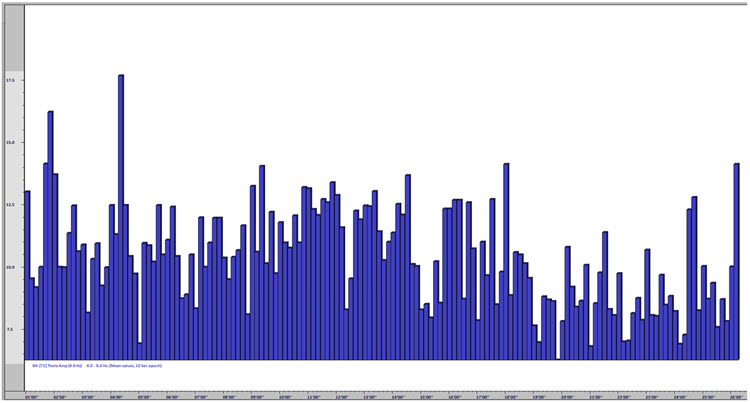

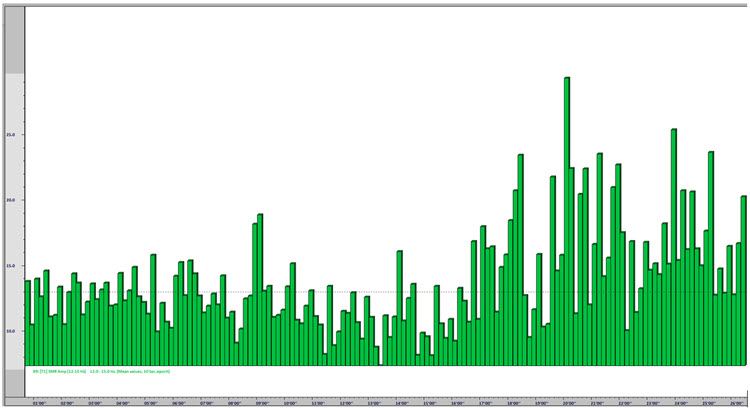

The images below show the results of the training session in graph form with explanations below each image.

Caption: This image shows the EMG artifact (75-100 Hz) amplitude decreasing across the session. The y-axis represents voltage, and the x-axis represents time (approximately 26 minutes). The EMG voltage (muscle activity) decreases. Though the change is moderate, at .5 μV, it represents an approximately 20% decrease in EMG artifact across the session, associated with steadily increasing relaxation.

Caption: This image shows high beta (22-36 Hz) amplitude decreasing across the session. The y-axis represents voltage, and the x-axis represents time (approximately 26 minutes). High beta voltage decreases. Though the change is partially due to the decrease in EMG artifact (because of the impact of EMG activity on the beta frequencies), this change is more significant, showing initial values in the 6-8 μV range decreasing into the 4-5 μV range (discounting movement artifact). This change represents a significant decrease in fast beta activity and shows decreased cognitive arousal often related to worry and rumination.

Caption: This image shows that theta (4-8 Hz) amplitude remained fairly steady across the session, with a moderate decrease toward the latter third of the session. The y-axis represents voltage, and the x-axis represents time (approximately 26 minutes). Although there is clear evidence of movement artifact and the likely influence of eye blink and eye movement artifact (this is an eyes-open training session, and hence there is more eye-related artifact influencing the slower frequencies), the session graph shows consistent values, with some change toward the end that may also be associated with the EMG reduction noted earlier.

Caption: This image shows the SMR (12-15 Hz) amplitude increasing toward the end of the session. The y-axis represents voltage, and the x-axis represents time (approximately 26 minutes). This graph shows an interesting change in SMR that corresponds to the timing of the decrease in EMG artifact and high beta. The SMR amplitude increases at about the same time as these decreases, and this tells us two things: first, the increase in SMR amplitude is not likely to be the result of EMG artifact affecting the voltage of SMR, and second, the change in the state represented by all signals is consistently toward greater physiological relaxation and a decrease in CNS arousal.

Note the horizontal dotted line that represents the training threshold during the session (related to the “bong” reward sound for SMR above the threshold for 250 ms or longer) and note that the SMR amplitude is sustained above the threshold more consistently toward the end of the session, rewarding the client for this change in behavior and providing her with information validating her successful response to the training challenge.

Refer to the discussion on auto-threshold settings. If this session had been conducted with auto-threshold settings, the client would have received a constant positive reward at a steady percentage, resulting in no increase in reward percentage corresponding to her improved values toward the end of the session. Because the threshold for the SMR discrete, event-related reward remained the same throughout, the client could perceive her success by the increased frequency of the ‘bong’ sound as the session progressed.

As mentioned above, clients with inattentive ADHD would need a different approach. The session might be divided into 3-5 minute segments with pauses between segments to evaluate the client’s progress, discuss training strategies, adjust thresholds, or simply give the client a break rather than expecting sustained attention for the entire session. With other presenting concerns such as migraine, other clients would require a completely different approach, possibly with frequent adjustments of the training reward and inhibit frequencies, regular check-ins with the client to determine pain levels, and possible shifts in sensor locations.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to neurofeedback training because each client is unique and requires interventions tailored to their presenting concerns and possible protocol adjustments based on their reactions to the training. This has been an example of one type of training approach with an adult client. Children and adolescents will present additional challenges for the practitioner and require patience, creativity, and attention.

Glossary

A (auricular): International 10-20 system earlobe reference placement.

alpha rhythm: 8-12-Hz activity that depends on the interaction between rhythmic burst firing by a subset of thalamocortical (TC) neurons linked by gap junctions and rhythmic inhibition by widely distributed reticular nucleus neurons. Researchers have correlated the alpha rhythm with relaxed wakefulness. Alpha is the dominant rhythm in adults and is located posteriorly. The alpha rhythm may be divided into alpha 1 (8-10 Hz) and alpha 2 (10-12 Hz).

amplitude: the strength of the EEG signal measured in microvolt or picowatts.

artifact: false signals like 50/60Hz noise produced by line current.

beta rhythm: 12-38-Hz activity associated with arousal and attention generated by brainstem mesencephalic reticular stimulation that depolarizes neurons in the thalamus and cortex. The beta rhythm can be divided into multiple ranges: beta 1 (12-15 Hz), beta 2 (15-18 Hz), beta 3 (18-25 Hz), and beta 4 (25-38 Hz).

bipolar (sequential) montage: a recording method that uses two active electrodes and a common reference.

C (central): sites in the International 10-20 system that detect frontal, parietal-occipital, and temporal EEG activity.

channel: EEG amplifier input from three leads (active, reference, and ground electrodes) placed on the head.

delta rhythm: 0.05-3 Hz oscillations generated by thalamocortical neurons during stage 3 sleep.

F (frontal): sites in the International 10-20 system that detect frontal lobe EEG activity.

Fp (frontopolar or prefrontal): sites in the International 10-20 system that detect prefrontal cortical EEG activity.

hertz (Hz): a unit of frequency measured in cycles per second.

impedance (Z): the complex opposition to an AC signal measured in Kohms.

impedance meter: a device that uses an AC signal to measure impedance in an electric circuit, such as between active and reference electrodes.

impedance test: automated or manual measurement of skin-electrode impedance.

inhibit training: setting a threshold to decrease unwanted EEG activity (e.g., 4-8 Hz and 22-36 Hz).

inion: a bony prominence on the back of the skull.

International 10-20 system: a standardized procedure for 21 recording and one ground electrode on adults.

mastoid bone: bony prominence behind the ear.

microvolt (μV): a unit of amplitude (signal strength) that is one-millionth of a volt.

referential (monoplar) montage: the placement of one active electrode (A) on the scalp and a neutral reference (R) and ground (G) on the ear or mastoid.

montage: a grouping of electrodes (combining derivations) to record EEG activity.

nasion: the depression at the bridge of the nose.

normative database: qEEG metrics obtained from a representative sample of participants during resting and active-task conditions.

notch filter: a filter that suppresses a narrow band of frequencies, such as those produced by line current at 50/60Hz.

O (occipital): sites in the International 10-20 system that detect occipital lobe EEG activity.

ohm (Ω): a unit of impedance or resistance.

P (parietal): sites in the International 10-20 system that detect parietal lobe EEG activity.

posterior dominant rhythm (PDR): the highest-amplitude frequency detected at the posterior scalp when eyes are closed.

power: the amplitude squared and may be expressed as microvolts squared or picowatts/resistance.

preauricular point: the slight depression located in front of the ear and above the earlobe.

protocol: a rigorously organized plan for training.

reference electrode: an electrode placed on the scalp, earlobe, or mastoid.

rhythmic temporal theta of drowsiness (RMTD): bitemporal left is greater than right in this longitudinal bipolar montage. Noted are notched rhythmic waveforms localized to the temporal regions, some of which are sharply contoured.

sensorimotor rhythm (SMR): the 13-15 Hz spindle-shaped sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) detected from the sensorimotor strip when individuals reduce attention to sensory input and reduce motor activity.

theta/beta ratio (T/B ratio): the ratio between 4-7 Hz theta and 13-21 Hz beta, measured most typically along the midline and generally in the anterior midline near the 10-20 system location Fz.

theta rhythm: 4-8-Hz rhythms generated a cholinergic septohippocampal system that receives input from the ascending reticular formation and a noncholinergic system that originates in the entorhinal cortex, which corresponds to Brodmann areas 28 and 34 at the caudal region of the temporal lobe.

z-score training: a neurofeedback protocol that reinforces in real-time closer approximations of client EEG values to those in a normative database.

tragus: the flap at the opening of the ear.

transient: isolated waveforms or complexes that can be distinguished from background activity.

vertex (Cz): the intersection of imaginary lines drawn from the nasion to inion and between the two preauricular points in the International 10-10 and 10-20 systems.

Test Yourself

Customers enrolled on the ClassMarker platform should click on its logo to take 10-question tests over this unit (no exam password).

REVIEW FLASHCARDS ON QUIZLET

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Visit the BioSource Software Website

BioSource Software offers Physiological Psychology, which satisfies BCIA's Physiological Psychology requirement, and Neurofeedback100, which provides extensive multiple-choice testing over the Biofeedback Blueprint.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, explain the purpose of inhibits in neurofeedback training.

References

Arns, M., de Ridder, S., Strehl, U., Breteler, M., & Coenen, A. (2009). Efficacy of neurofeedback treatment in ADHD: The effects on inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity: A meta-analysis. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, 40(3), 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/155005940904000311

Campos da Paz, V. K., Garcia, A., Campos da Paz Neto, A., & Tomaz, C. (2018). SMR neurofeedback training facilitates working memory performance in healthy older adults: A behavioral and EEG study. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 12, 321. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00321

Colgan M. (1977). Effects of binary and proportional feedback on bidirectional control of heart rate. Psychophysiology, 14(2), 187–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1977.tb03374.x

Gevensleben, H., Kleemeyer, M., Rothenberger, L. G., Studer, P., Flaig-Röhr, A., Moll, G. H., Rothenberger, A., & Heinrich, H. (2014). Neurofeedback in ADHD: Further pieces of the puzzle. Brain topography, 27(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-013-0285-y

Mohammadi, M. R., Malmir, N., Khaleghi, A., & Aminiorani, M. (2015). Comparison of sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) and beta training on selective attention and symptoms in children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A trend report. Iran J Psychiatry, 10(3), 165-174. PMCID: PMC4749686

Rajabi, S., Pakize, A., & Moradi, N. (2020). Effect of combined neurofeedback and game-based cognitive training on the treatment of ADHD: A randomized controlled study. Applied Neuropsychology Child, 9(3), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622965.2018.1556101

Soutar, R., & Longo, R. (2022). Doing neurofeedback: An introduction (2nd ed.). ISNR Research Foundation.

Strehl U. (2014). What learning theories can teach us in designing neurofeedback treatments. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 894. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00894

Swingle, P. (2014). Clinical versus normative databases: Case studies of clinical Q assessments. NeuroConnections.

Thatcher, R. W. (1998). Normative EEG databases and EEG biofeedback. Journal of Neurotherapy, 2(4), 8-39. https://doi.org/10.1300/J184v02n04_02

Thatcher, R. W., Lubar, J. F., & Koberda, J. L. (2019). Z-Score EEG biofeedback: Past, present, and future. Biofeedback, 47(4), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-47.4.04

Thomas, C. (2007). What is a montage? EEG instrumentation. American Society of Electroneurodiagnostic Technologists, Inc.

Thompson, M., & Thompson, L. (2015). Neurofeedback Book: An introduction to basic concepts in applied psychophysiology (2nd ed.). Association for the Advancement of Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.