Therapeutic Relationship, Coaching, and Reinforcement Strategies

Although some of “what works” in therapy is attributable to specific techniques that therapists employ, a greater proportion of therapy’s success is due to the quality of the therapeutic relationship (or “alliance”) between the therapist and the client (Norcross & Wampold, 2011a; Rosenfeld, 2009; Wampold & Imel, 2015). Therapy manuals typically don’t emphasize this relationship; instead, they tend to emphasize technique. In other words, they generally overlook “how” therapists relate to their clients in favor of “what” therapists do with (or to) their clients. A therapist who operates as a technician carrying out mechanical, predetermined methods can do a disservice to clients who seek a meaningful human connection (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2009).

In fact, some psychologists argue that it’s the relationship, not the technique, that should be evidence-based (Kazantzis, Cronin, Norton, Lai, & Hofmann, 2015). Along those lines, soon after proponents of the manualized treatment movement published their landmark book A Guide to Treatments That Work (Nathan & Gorman, 1998), another group of psychologists responded with contrasting viewpoints in a book fittingly titled Psychotherapy Relationships That Work (Norcross, 2002), insisting that the therapist–client relationship should not be neglected but should be recognized and studied as a focal point of what makes therapy work (Pomeranz, 2020, p. 57).

Graphic © Monster Ztudio/Shutterstock.com.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses VIII. Treatment Implementation - B. Therapeutic Relationship, Coaching, and Reinforcement Strategies.

We will cover the Therapeutic Relationship, Coaching, and Reinforcement Strategies in this unit.

Please click on the podcast icon below to hear a full-length lecture.

The Therapeutic Relationship

Culture-Specific Perspectives

North American and Western European psychotherapy models encourage clients to discuss their difficulties and feelings to develop insight and control. This therapeutic process violates the norms of non-Western cultures that value avoidance or concealment of difficult feelings or thoughts (Fontes, 2008; Toukmanian & Brouwers, 1998). Neurofeedback providers may be asked to provide services to clients who do not look or think like them. Graphic ©Andrey_Popov/Shutterstock.com.

Neurofeedback providers should be culturally competent to understand their clients' expectations about neurofeedback and the cultural norms that affect the client's comfort with the delivery of services. Providers should understand their own cultural biases and recognize and accept their clients' cultural values (Pomeranz, 2020). Providers should create an environment where clients feel safe, and their cultural values are respected. Cultural sensitivity should inform client orientation, the performance of routine tasks like skin preparation and sensor application, training instructions, feedback, and practice assignments.

Therapeutic Alliance

The therapeutic alliance is a trusting partnership between the therapist and client to achieve the client's goals. A therapist builds an alliance by listening to the client throughout their relationship, starting with the initial contact and assessment. Listening is only one-half of the process. The therapist must also demonstrate that they have heard the client and share their objectives. Client education should emphasize how assessment, training, practice assignments, and progress reports should address the client's concerns.The therapeutic relationship is the strongest predictor of clinical outcome and accounts for more variability than specialized therapeutic techniques (Beitman & Manring, 2009; Wampold, 2010). The client's view of the relationship is vital since this influences client engagement. Clients prefer warm, relatable therapists (Swan & Heesacker, 2013). Graphic © Truman State University Center for Applied Psychophysiology.

Taub and School (1978) reported a person effect when teaching hand-warming. An "informal and friendly" trainer successfully taught 19 of 21 participants (90.5%) to raise their finger temperature. In contrast, a more formal and "impersonal" trainer only succeeded with 2 of 22 participants (9.1%) (p. 617). The interpersonal dynamics that make psychotherapy successful are crucial in biofeedback training.

Kamiya (retrieved from Neumann, 2001, p. 32) observed:

My experience with years of biofeedback training with various physiological modalities leaves me with the conviction that a very large portion of the total influences on learning is bio-social in nature, testifying to the evolution of the species as a social species. Though seldom discussed in the scientific literature, the nature of interpersonal relations between trainer and trainee are often decisive for learning progress.Since correlation can only suggest possible causal paths, researchers cannot definitively explain how the therapeutic relationship impacts treatment success. The relationship might be reciprocal. Good relationships may increase client commitment, effort, and success.

The reverse may also be true. As the client succeeds, they may like and trust their therapist more (Zilchia-Mano, Dinger, McCarthy, & Barber, 2014). Also, the therapist may value the client more, invest more effort in training, and provide greater encouragement as the client becomes more engaged, successful, and committed to their relationship.

Coaching

Therapists Should Be Credible Models

Unlike stereotypical "out-of-shape coaches with beer guts," neurofeedback providers should develop and practice the skills they teach. Peper (1994) strongly argued that therapists must be "self-experienced." If you sought treatment for anxiety, how confident would you be if your therapist looked "stressed out" and offered you an ice-cold handshake? Our colleague, Don Moss, has learned to warm his hands during freezing Michigan winters because children expect him to prove that he can do what he's teaching.Therapists are intentional and unintentional models. Their self-regulation training can increase their awareness of their psychophysiological responses like cold hands, breath-holding, and incomplete muscle relaxation. Covert modeling is powerful because it can operate outside of clinician or client consciousness. Unless therapists become aware of their dysfunctional behaviors, they might inadvertently teach them to their clients.

Personal training enables therapists to develop the skills they intend to teach, increases their confidence in the effectiveness of their training methods, and helps them better understand their clients' inevitable frustrations.

Therapists Should Be Good Personal Trainers

Successful personal training requires assessment, clear explanation of training goals, modeling of the desired skill, effective instructions delivered using systematic training techniques, immediate and useful performance feedback, graduated challenge with appropriate reinforcement, and sufficient time to acquire the skill. Practice outside of a clinic setting is critical to skill acquisition. Graphic © wavebreakmedia/ Shutterstock.

Four personal training principles should inform neurofeedback training: specificity, individualization, overload, and progression. The authors are indebted to Crossley's (2012) Personal Training: Theory and Practice for their coverage of personal training concepts.

The principle of specificity states that improvement is specific to the training we provide. The SAID principle proposes that we achieve Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands. In other words, "we get good at what we do." Carryover means that training on one task can influence the performance of others. . For example, practitioners may provide heart rate variability biofeedback before neurofeedback to increase client attention and normalize breathing.

The principle of individualization reminds us to adjust training to the individual because learning curves and responses to interventions differ. High responders learn self-regulation quickly, whereas low responders need to work harder. Likewise, although most clients may benefit from an intervention, a minority may deteriorate. For example, a client presenting with anxiety worsened when their clinician down-trained fast beta. Clinicians can individualize training based on EEG or qEEG assessment and a detailed health or performance history that includes medication and prior self-regulation practice and training.

The principle of overload proposes that we challenge clients to promote positive adaptation where performance improves. There is a "Goldilocks zone," called optimal overload, in which stress and recovery produce an optimal training effect. Excessive stress or insufficient recovery time can cause negative adaptation, preventing or slowing learning. Clinicians avoid this outcome by not exceeding the point of failure where performance falters. In neurofeedback, clinicians can adjust the level of challenge by changing reinforcement requirements (e.g., reward and inhibit thresholds and duration), task difficulty, and training length.

Finally, the principle of progression asserts that we need to increase challenge systematically to achieve optimal overload and avoid plateau where a client ceases to improve. If we don't increase the difficulty level as a client's self-regulation skills increase, adaptation and training effects will diminish. This is analogous to walking the same number of steps a day for years. Although aerobic capacity increased initially, it ceased to improve after weeks at the same workload.

Reinforcement Strategies

A Review of Operant Conditioning

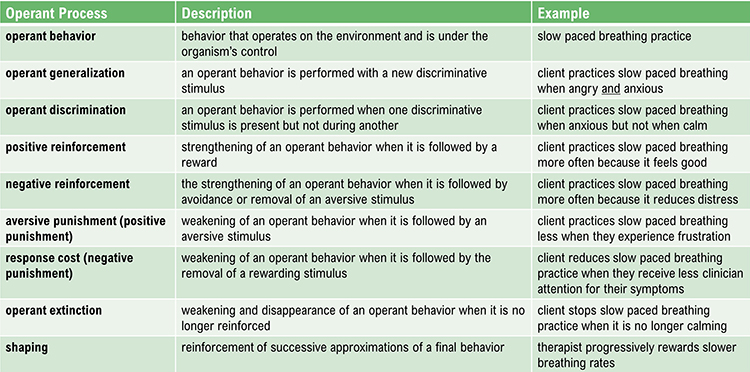

Edward Thorndike's (1913) law of effect proposed that the consequences of behavior determine its addition to your behavioral repertoire. Cats learned to escape "puzzle boxes" by repeating successful actions and eliminating unsuccessful ones from his perspective.Operant conditioning is an unconscious associative learning process that modifies operants by manipulating their consequences (Miltenberger, 2016). Operant behaviors are voluntary actions that operate on the environment to produce an outcome.

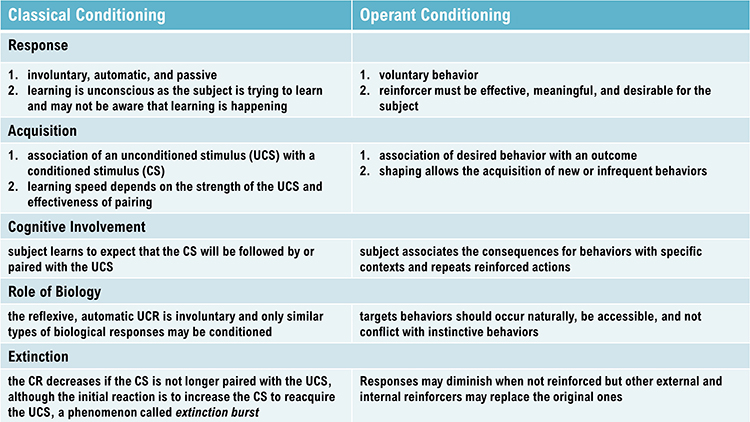

Operant conditioning differs from classical conditioning in several respects. Where operant conditioning teaches the association of a voluntary behavior with its consequences, classical conditioning teaches the predictive relationship between two stimuli to modify involuntary behavior.

Neurofeedback teaches self-regulation of neural activity and related "state changes" using operant conditioning via the selective presentation of reinforcing stimuli, including visual, auditory, and tactile displays. Sherlin et al. (2011) emphasize that clinicians should understand specific waveforms (e.g., SMR), their duration (e.g., 0.25 s), and source to provide effective training.

Operant conditioning occurs with a situational context. The identifying characteristics of a situation are called its discriminative stimuli and can include the physical environment and physical, cognitive, and emotional cues. Discriminative stimuli teach us when to perform operant behaviors.

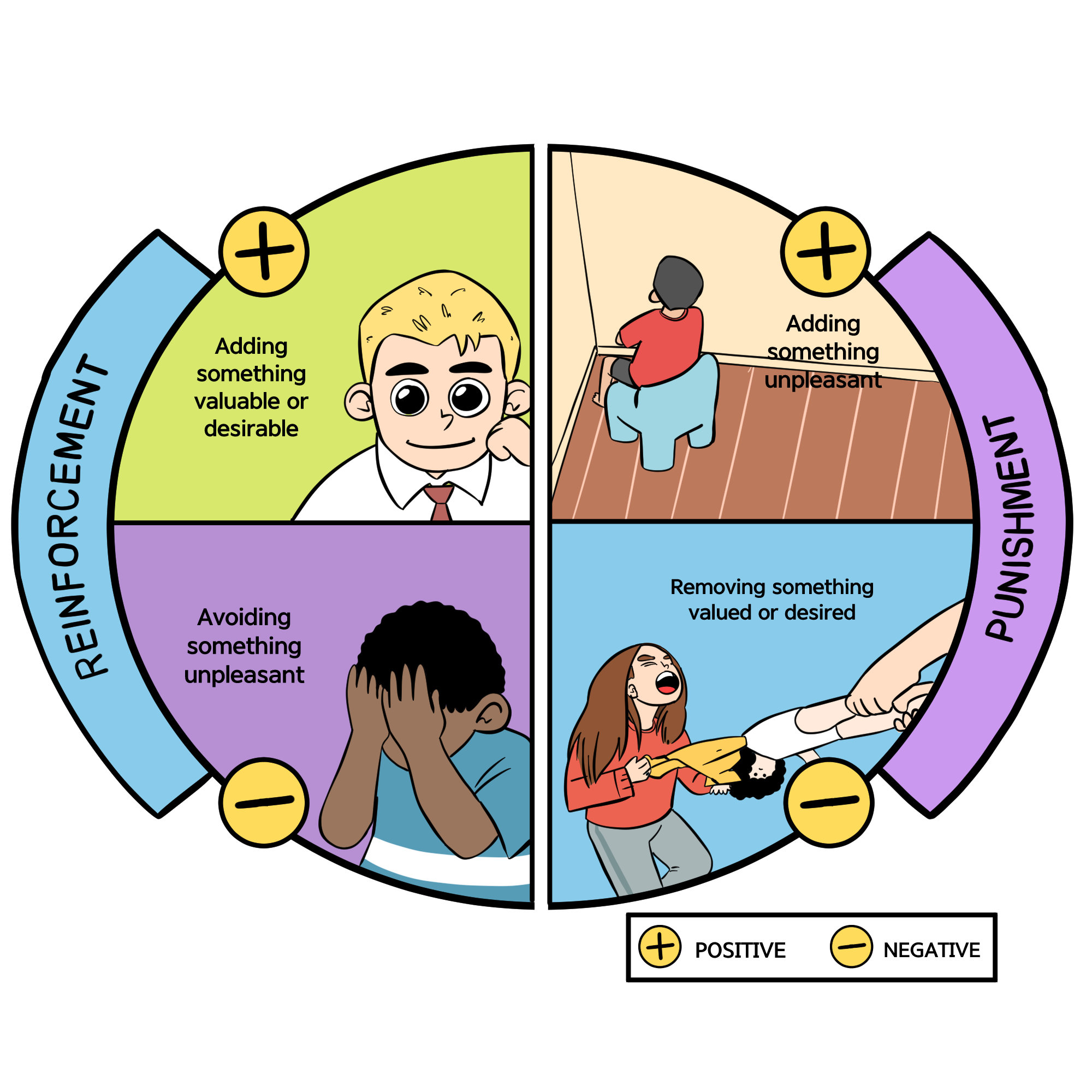

The consequences of operant behaviors can increase or decrease their frequency. Skinner proposed four types of consequences: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment. Where positive and negative reinforcement increase behavior, positive and negative punishment decrease it.

Due to individual differences, we cannot know in advance whether a consequence will be reinforcing or punishing since these are not intrinsic properties of a consequence. We can only determine whether a consequence is reinforcing or punishing by measuring how it affects the preceding behavior. In neurofeedback, a movie that motivates the best performance might reinforce the client, regardless of the therapist's personal preference.

Positive reinforcement increases the frequency of a desired behavior by making a desired outcome contingent on performing the action. For example, a movie plays when a client diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) increases low-beta and decreases theta activity.

Negative reinforcement increases the frequency of a desired behavior by making the avoidance, termination, or postponement of an unwanted outcome contingent on performing the action. For example, an athlete's anxiety decreases by shifting from high beta to low beta.

Positive punishment decreases or eliminates an undesirable behavior by associating it with unwanted consequences. For example, a child's increased fidgeting dims a favorite movie and decreases the sound.

Negative punishment decreases or eliminates an undesirable behavior by removing what is desired. For example, oppositional behavior could result in a clinician turning off a popular game.

Operant conditioning graphic by Dani S@unclebelang on fiverr.com.

Reinforcement Criteria

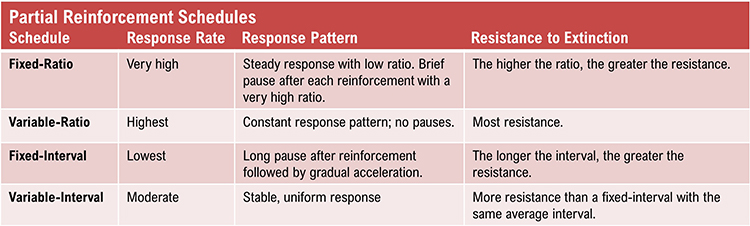

Current research is exploring the optimal reinforcement criteria for neurofeedback training. Client skill acquisition is markedly affected by changing parameters like reinforcement schedule, frequency of reward, reinforcement delay, conflicting reinforcements, conflicting expectations, and environment alteration.Reinforcement can be continuous or partial. In continuous reinforcement, every correct response is rewarded quickly. Many neurofeedback protocols deliver continuous reinforcement during training sessions. Neurofeedback training can incorporate transfer trials in which clients do not receive feedback (e.g., correct or incorrect) until a trial's conclusion to aid generalization (Sherlin et al., 2011).

Although a continuous reinforcement schedule is helpful during the early stage of skill acquisition, it is impractical as clients attempt to transfer the skill to real-world settings. Since reinforcement outside of the clinic is intermittent, partial reinforcement schedules, where the desired behavior is only rewarded some of the time, are essential as training progresses. This reduces the risk of extinction, where failure to reinforce a desired behavior decreases the frequency of that behavior.

For neurofeedback, variable reinforcement schedules, where reinforcement occurs after a variable number of responses (variable ratio) or following a variable duration of time (variable interval) produce superior response rates than their fixed counterparts.

Shaping, the method of successive approximations, teaches clients new behaviors and increases the frequency of rarely performed behaviors. A clinician starts by reinforcing spontaneous voluntary behaviors that resemble the desired behavior and progressively raises the reinforcement criteria to achieve the training goal. For example, the clinician can gradually require lower theta-to-beta ratios for a movie to play.

Discrimination and Generalization

Discrimination and generalization are the ultimate goals of neurofeedback training. Discrimination teaches when a desired behavior will be reinforced. The initial discriminative stimuli include the cues provided by the training environment, like animations and tones. A clinician may introduce a stressor following successful skill acquisition to "raise the bar." Now, the stressor serves as another discriminative stimulus for performing the desired behavior.Generalization teaches the transfer of a desired behavior to multiple environments and in response to diverse stressors. While the ability to perform the learned response in many situations contributes to flexibility, it is not always advantageous. Discrimination, based on an understanding of set and setting, helps determine when a response is required and which response is appropriate.

Research Findings

Several discoveries relevant to neurofeedback concern post-reinforcement synchronization, speed of reinforcement, and training strategies.Post-Reinforcement Synchronization

Clemente, Sterman, and Wyrwicka (1964) first described post-reinforcement synchrony (PRS) in an operant conditioning paradigm. PRS, parieto-occipital cortical alpha-like synchrony following reinforcement of an operant behavior, depends on the performance of an operant behavior (e.g., pressing a lever) and not simple receipt of reinforcement. This phenomenon has been confirmed in monkeys and humans and is correlated in cats with memory consolidation and learning speed (Marcynski et al., 1981).Speed of Reinforcement

The timing of reinforcement is critical to associate the desired behavior with its consequences. Several early studies have shown that the optimal latency between a voluntary behavior and reinforcement is less than 250 to 350 ms (Felsinger & Gladstone, 1947; Grice, 1948). The faster the delivery of reinforcement following the desired behavior, the less time required for skill acquisition.Training Strategies

Strehl (2014) concluded that there are no validated interindividual strategies for slow cortical potential (SCP) feedback. Participants develop individualized strategies that may shift during an experiment (Roberts et al., 1989). Healthy participants who received SCP feedback without instructions performed better than their counterparts who received them (Hardman et al., 1997). Likewise, healthy participants who received SMR feedback and reported using no strategy performed best (Kober et al., 2013). Strehl concluded that clinicians should not suggest strategies.Reinforcement Promotes Awareness and Performance

Auditory and visual reinforcement informs clients that they have met performance goals. Knowledge of results allows clients to perceive connections between their actions, internal sensations, and external feedback. Reinforcement reveals when strategies work and how generating the desired EEG activity feels.In addition, positive reinforcement enhances client motivation to enhance brain performance. Training goals should reward effort while challenging clients to "up their game." Olton and Noonberg (1980) proposed a goal-setting algorithm based on their biofeedback training experience: goals should be raised when clients succeed more than 70% of the time and lowered when a client succeeds less than 30% of the time. While a 70-30 algorithm is a plausible approach, there is no compelling evidence that it is superior to a 50-50 strategy.

Since client learning curves and motivation may differ profoundly, clinicians should fine-tune goal-setting to individual clients. Training goals should fall within a "Goldilock's zone," neither discouraging nor unchallenging. This strategy helps to maintain client motivation and increase their perception of self-efficacy.

A clinician's role in providing encouragement and feedback is an essential component of reinforcement in general. Initially, when a client meets a goal, the clinician providing a “good job!” comment can be highly reinforcing, particularly for clients with low self-esteem. Additionally, a clinician offering ‘I messages’ can be quite powerful. A comment such as “I’m impressed by how well you focused just then; you kept the game going for a long time. That must have taken some real concentration” is easier for many clients to accept since it is expressed as the clinician’s opinion.

Finally, it is important for the clinician to regularly and frequently remind the client that progress results from the client’s efforts and is not due to any input from the clinician or equipment. Clients may have heard the message that this is training, not treatment. Still, regular reminders will allow them to internalize this self-actualizing message and learn to accept the credit for progress.

Glossary

alpha variability threshold: a criterion for receiving feedback when alpha amplitude or its variability decrease.

alpha synchrony threshold: a criterion for receiving feedback that increases alpha amplitude over the scalp.

carryover: training on one task can influence performance on others.

collateral information: reports from family members, friends, and healthcare professionals.

continuous reinforcement: rewarding every correct response quickly.

covert modeling: unconscious modeling by a clinician; also called implicit modeling.

cultural malpractice: assessment and treatment decisions biased by cultural insensitivity and ethnocentrism.

culturally-competent assessment: assessment that is informed by and sensitive to the meaning of actions, beliefs, and feelings within a client's culture.

discrimination: a learning process that teaches when a desired behavior will be reinforced.

discriminative stimuli: the physical environment and physical, cognitive, and emotional cues that signal when to perform operant behaviors.

dynamic z-score thresholds: dynamic thresholds that deliver feedback almost 50% of the time calculated from brief periods (e.g., 10 seconds).

evidence-based assessment: client evaluation using instruments that are reliable, valid, and possess clinical utility.

extinction: failure to reinforce a desired behavior reduces the frequency of that behavior.

generalization: a learning process that teaches the transfer of a desired behavior to multiple environments and in response to diverse stressors.

high responders: individuals who learn self-regulation quickly.

inhibit threshold: criterion for suspending feedback, analogous to a limbo bar, designed to decrease bandpass amplitude.

law of effect: the consequences of behavior determine its addition to your behavioral repertoire.

low resolution electromagnetic tomography (LORETA): Pascual-Marqui's (1994) mathematical inverse solution to identify the cortical sources of 19-electrode quantitative data acquired from the scalp.

low responders: individuals who learn self-regulation slowly.

multimethod assessment: evaluation using multiple assessment tools.

negative adaptation: the slowing or deterioration of learning due to stress or insufficient recovery time when challenged.

negative punishment: a learning process that decreases or eliminates an undesirable behavior by associating it with unwanted consequences.

negative reinforcement: a learning process that increases the frequency of a desired behavior by making the avoidance, termination, or postponement of an unwanted outcome contingent on performing the action.

operant behaviors: voluntary actions that operate on the environment to produce an outcome.

operant conditioning: an unconscious associative learning process that modifies operants by manipulating their consequences.

optimal overload: stress and sufficient recovery time product an optimal training effect.

overpathologizing: labeling culturally normal behavior as abnormal.

partial reinforcement: rewarding desired behaviors only some of the time.

percentage of success: a z-score training protocol where a client receives feedback when a predetermined percentage of EEG components fall within ±1, 2, or 3 z-scores.

person effect: Taub and School's (1978) observation that biofeedback training is a social situation and that a client's relationship with the therapist is a critical aspect of training.

plateau: performance ceases to improve.

point of failure: performance deterioration due to excessive stress or insufficient recovery time.

positive adaptation: performance improvement when clients are challenged.

positive punishment: a learning process that decreases or eliminates an undesirable behavior by associating it with unwanted consequences.

positive reinforcement: learning process that increases the frequency of a desired behavior by making a desired outcome contingent on performing the action.

post-reinforcement synchrony (PRS): parieto-occipital cortical alpha-like synchrony following reinforcement of an operant behavior, depends on the performance of an operant behavior (e.g., pressing a lever) and not simple receipt of reinforcement.

principle of individualization: adjustment of training to the individual because learning curves and responses to interventions differ.

principle of overload: challenge clients to promote positive adaptation where performance improves.

principle of progression: increase challenge systematically to achieve optimal overload.

principle of specificity: improvement is specific to the training we provide.

ratio-threshold: a criterion for receiving feedback that reinforces changes in the ratio of two EEG bandpasses.

reward threshold: a criterion for receiving feedback analogous to a hurdle in track designed to increase bandpass amplitude.

SAID principle: we achieve Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands.

shaping: the method of successive approximations teaches clients new behaviors and increases the frequency of rarely performed behaviors.

slow cortical potentials (SCPs): gradual changes in the membrane potentials of cortical dendrites that last from 300 ms to several seconds. These potentials include the contingent negative variation (CNV), readiness potential, movement-related potentials (MRPs), and P300 and N400 potentials. SCPs modulate the firing rate of cortical pyramidal neurons by exciting or inhibiting their apical dendrites. They group the classical EEG rhythms using these synchronizing mechanisms.

therapeutic alliance: a trusting partnership between the therapist and client to achieve the client's goals.

transfer trials: conditions in which clients do not receive feedback (e.g., correct or incorrect) until a trial's conclusion to aid generalization.

variable reinforcement: reinforcement occurs after a variable number of responses (variable ratio) or following a variable duration of time (variable interval). These schedules produce superior response rates compared with their fixed counterparts.

z-score training: neurofeedback protocol that reinforces in real-time closer approximations of client EEG values to those in a normative database.

Test Yourself on ClassMarker

Click on the ClassMarker logo below to take a 10-question exam over this entire unit.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, which sounds do your clients prefer when they succeed during neurofeedback training? Which visual displays motivate them?

References

Bear, L., & Blais, M. A. (Eds.) (2010). Handbook of clinical rating scales and assessment in psychiatry and mental health. Springer Nature.

Beitman, B. D., & Manring, J. (2009). Theory and practice of psychotherapy integration. In G. O. Gabbard (Ed.), Textbook of psychotherapeutic treatments (pp. 705–726). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Clemente, C. D., Sterman, M. B., & Wyrwicka, W. (1964). Post-reinforcement EEG synchronization during alimentary behavior. Electroencephalography Clinical Neurophysiology,16, 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4694(64)90069-0

Collura, T. F. (2014). Technical foundations of neurofeedback. Routledge.

Conners, C. K. (2014). Conners Continuous Performance Test (3rd ed.). Multi-Health Systems.

Dana, R. H. (2005). Multicultural assessment: Principles, applications, and examples. Erlbaum.

Delis, D. C., Kaplan, E. F., & Kramer, J. H. (2001). Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System. The Psychological Corporation.

Demos, J. N. (2019). Getting started with EEG neurofeedback (2nd ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Felsinger, J. M., & Gladstone, A. I. (1947). Reaction latency (StR) as a function of the number of reinforcements (N). Journal of Experimental Psychology, 37(3), 214-228. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0055587

Fontes, L. A. (2008). Interviewing clients across cultures: A practitioner’s guide. Guilford Press.

Gaultieri, T., & Johnson, L. G. (2006). Reliability and validity of a computerized neurocognitive test battery, CNS Vital Signs. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 21, 623-643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2006.05.007

Grice, G. R. (1948). The acquisition of a visual discrimination habit following response to a single stimulus. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38(6), 633-642. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0056158

Hardman, E., Gruzelier, J., Cheesman, K., Jones, C., Liddiard, D., Schleichert, H., & Birbaumer, N. (1997). Frontal interhemispheric asymmetry: Self regulation and individual differences in humans. Neurosci. Lett. 221, 117–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13303-6

Hardt, J. V., & Kamiya, J. (1976). Conflicting results in EEG alpha feedback studies: Why amplitude integration should replace percent time. Biofeedback Self Regul, 1(1), 63-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00998691

Kaiser, D. A. (2008). Functional connectivity and aging: Comodulation and coherence differences. Journal of Neurotherapy, 12, 123-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874200802398790

Khazan, I. Z. (2013). Clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. Wiley-Blackwell.

Kober, S. E., Witte, M., Ninaus, M., Neuper, C., & Wood G. (2013). Learning to modulate one’s own brain activity: the effect of spontaneous mental strategies. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7, 695. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00695

Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B., Bigler, E. D., & Tranel, D. (2012). Neuropsychological assessment (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Marczynski, T. J., Harris, C. M., & Livezey, G. T. (1981). The magnitude of post-reinforcement EEG synchronization (PRS) in cats reflects learning ability. Brain Research, 204, 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(81)90667-3

Miltenberger, R. G. (2016). Behavior modification: Principles and procedures. Cengage Learning.

Neumann N. (2001). Gehirn-Computer-Schnittstelle: Einflussfaktoren der Selbstregulation Langsamer Kortikaler Hirnpotentiale. Dissertation Tübingen: Schwäbische Verlagsgesellschaft.

Olton, D. S., & Noonberg, A. R. (1980). Biofeedback: Clinical applications in behavioral medicine. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Peper, E., Tylova, H., Gibney, K., H., Harvey, R., & Combatalade, D. (2008). Biofeedback mastery: An experiential teaching and self-training manual. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Pomeranz, A. M. (2020). Clinical psychology: Science, practice, and diversity (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Psychology Tools. (n.d.). Psychological assessment tools for mental health. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www.psychologytools.com/download-scales-and-measures/

Ribas, V. R., Ribas, R. de M. G., & Martins, H. A. de L. (2016). The learning curve in neurofeedback of Peter Van Deusen: A review article. Dementia and Neuropsychologia, 10, 98-103. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1980-5764-2016dn1002005

Roberts, L. E., Birbaumer, N., Rockstroh, B., Lutzenberger, W., & Elbert, T. (1989). Self-report during feedback regulation of slow cortical potentials. Psychophysiology 26, 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1989.tb01941.x

Sadock, B. J., Sadock, V. A., & Ruiz, P. (2017). Kaplan and Sadock's concise textbook of clinical psychiatry (4th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Schwartz, M. S. (2016). Intake and preparation for intervention. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.), Biofeedback: A practitioner’s guide (4th ed.) (pp. 217-232). Guilford Press.

Sherlin, L. H., Arns, M., Lubar, J., Heinrich, H., Kerson, C., Strehl, U., & Sterman, M. B. (2011). Neurofeedback and basic learning theory: Implications for research and practice. Journal of Neurotherapy, 15, 292-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874208.2011.623089.

Silverman, J., Kurtz, S., & Draper, J. (2013). Skills for communicating with patients (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

Soutar, R., & Longo, R. (2022). Doing neurofeedback: An introduction (2nd ed.). ISNR Research Foundation.

Strehl, U. (2014). What learning theories can teach us in designing neurofeedback treatments. Front. Hum. Neursci., 8, 894. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00894

Stucky, J., & Bush, S. S. (2017). Neuropsychology fact-finding casebook: A training resource. Oxford University Press.

Swan, L. K., & Heesacker, M. (2013). Evidence of a pronounced preference for therapy guided by common factors. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(9), 869–879. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21967

Swingle, P. G. (2015). Adding neurofeedback to your practice: Clinician’s guide to ClinicalQ, neurofeedback, and braindriving. Springer.

Thatcher, R. W. (2020). Handbook of quantitative EEG and EEG biofeedback (2nd ed.). ANI Publishing.

Thompson, M., & Thompson, L. (2015). Neurofeedback book: An introduction to basic concepts in applied psychophysiology (2nd ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Thorndike, E. L. (1913). Educational psychology: Briefer course. Teachers College.

Toukmanian, S. G., & Brouwers, M. C. (1998). Cultural aspects of self-disclosure and psychotherapy. In S. S. Kazarian & D. R. Evans (Eds.), Cultural clinical psychology (pp. 106–124). Oxford University Press.

Wampold, B. E. (2010). The research evidence for the common factors model: A historically situated perspective. In B. L. Duncan, S. D. Miller, B. E. Wampold, & M. A. Hubble (Eds.), The heart and soul of change: Delivering what works in therapy (2nd ed., pp. 49–81). American Psychological Association.

Zilcha-Mano, S., Dinger, U., McCarthy, K. S., & Barber, J. P. (2014). Does alliance predict symptoms throughout treatment, or is it the other way around? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 931–935. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2Fa0035141