Definition

What You Will Learn

Whether you work in a VA hospital treating combat veterans with PTSD, a rehabilitation clinic helping stroke patients recover motor function, or a performance center training Olympic athletes, you likely share a common question: how can I help my clients gain better control over their own physiology? This unit introduces the foundational concepts that answer that question through biofeedback and neurofeedback training.

You will explore how these learning-based approaches help individuals regulate their psychophysiology, understand the key definitions from major professional organizations, and learn to distinguish legitimate biofeedback from physiological monitoring, modulation, and pseudo-biofeedback devices. By the end of this unit, you will be able to explain neurofeedback clearly to clients and describe its relationship to biofeedback training.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage: This unit addresses I. Orientation to Neurofeedback - A. Definition of Neurofeedback (EEG Biofeedback).

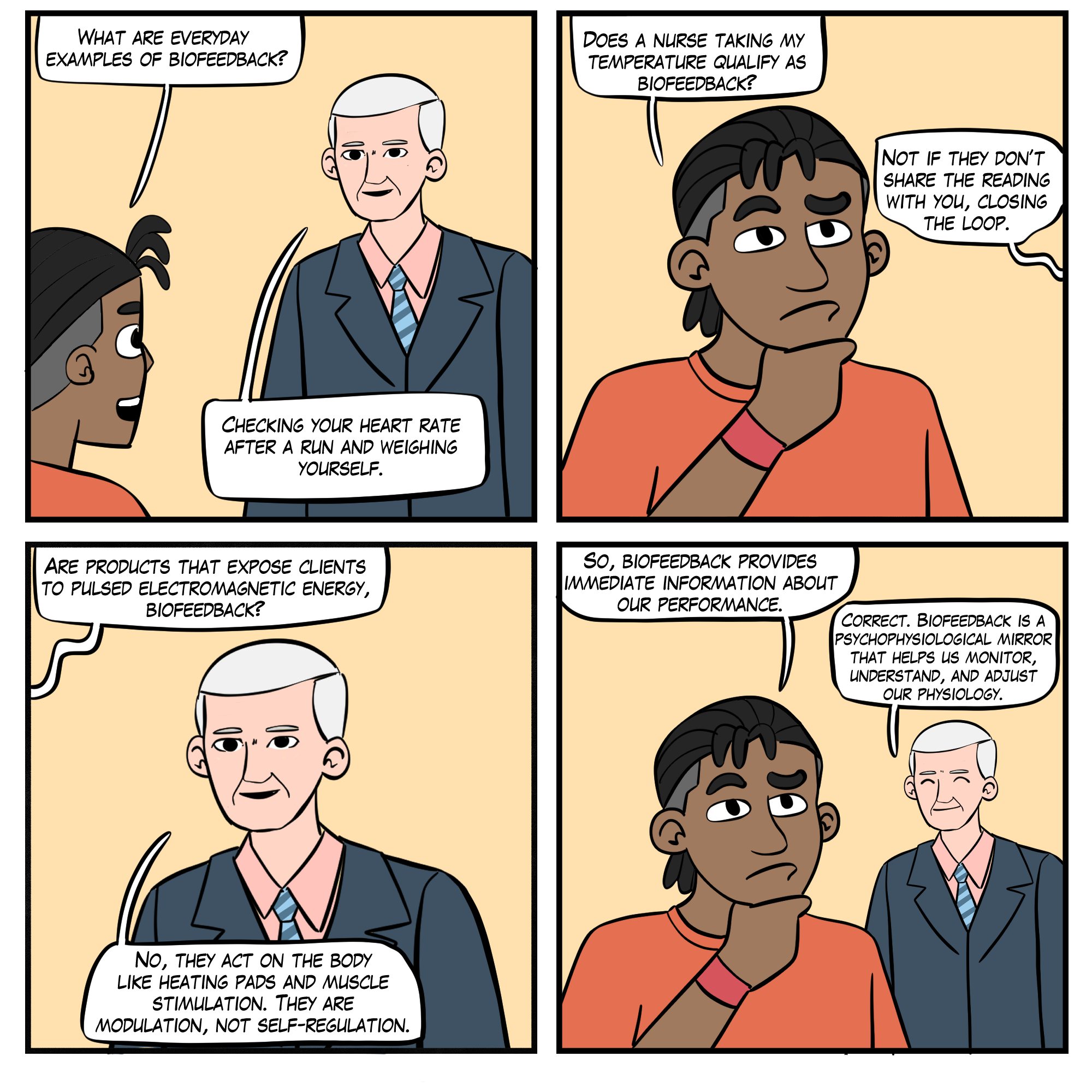

Biofeedback training (BFT) and neurofeedback training (NFT) harness the same learning processes you use to master any skilled activity, from playing tennis to driving a car. The sequence is intuitive: you act (perhaps taking a slow, effortless breath), observe the result (watching your heart rate variability increase on screen), and refine your approach based on that feedback. Through repeated practice across sessions, clients actively learn to regulate their psychophysiology (Thompson & Thompson, 2016).

Think of biofeedback as a "psychophysiological mirror" that reveals what is happening inside the body in real time (Peper, Shumay, & Moss, 2012). Just as a mirror helps you adjust your posture, biofeedback helps clients recognize and modify physiological states they cannot otherwise perceive directly. Over time, clients learn to detect these internal signals without equipment, replacing external feedback with accurate internal awareness.

NFT is the branch of BFT that uses an electroencephalograph (an instrument that monitors brain electrical activity such as brainwaves) rather than peripheral measures like muscle tension, heart rate variability, or skin temperature. This contrasts with an electromyograph, which detects action potentials from skeletal muscles. Each modality captures different physiological signals, processes them distinctly, and provides unique windows into bodily function (Collura, 2014).

The Process of Neurofeedback

At its core, neurofeedback is an interactive process: an electronic device measures your client's brain electrical activity and displays that information back to them in real time. This creates a feedback loop that enables learning and self-regulation.

The goals of neurofeedback training span from basic regulation to peak performance. Clinicians use it to ensure correct function in the brain's neuromodulating systems, encourage broad neuropsychophysiological change, address specific disorders or performance barriers rooted in dysregulation, and optimize nervous system functioning. Whether you are treating anxiety in a hospital outpatient clinic or enhancing reaction time for a military special operations team, these same principles apply.

What Neurofeedback Does

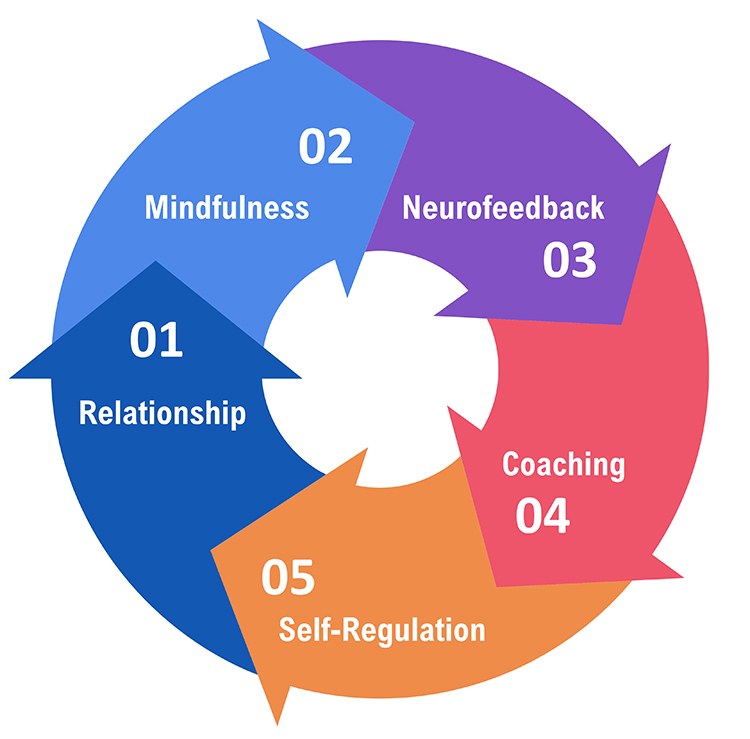

Effective neurofeedback delivers accurate, timely, and meaningful information to clients through visual, auditory, or tactile feedback that responds to significant changes in their neuronal activity. When the brain moves toward the training target, the feedback reinforces that shift. This process cultivates three qualities that benefit virtually every client population: flexibility in neural responding, resilience under stress, and expanded choice in how they regulate their own states.

The International Society for Neuroregulation and Research (ISNR) provides a comprehensive Neurofeedback Overview for those seeking additional background.

Research consistently shows that BFT becomes more effective when training incorporates mindfulness, an accepting and non-judgmental focus on present-moment experience (Khazan, 2013). A mindfulness approach teaches clients to observe their immediate feelings, thoughts, and sensations without harsh self-criticism. Crucially, it helps them distinguish between what they can and cannot control, then directs their energy toward changing what is actually within their power.

Consider James, an undergraduate psychology major diagnosed with ADHD. When he ruminated about mistakes on daily quizzes, his anxiety undermined his motivation to study, creating a vicious cycle that lowered his grades further. He could not focus on coursework while simultaneously worrying about past performance. The breakthrough came when James learned to accept occasional errors without catastrophizing. By changing what he could control (his emotional reaction to mistakes) rather than what he could not (the fact that mistakes happen), both his study habits and his course grade improved substantially.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses I. Orientation to Neurofeedback - A. Definition of Neurofeedback (EEG Biofeedback) from the BCIA certification blueprint.

The unit covers three main topic areas: Definitions of Biofeedback and Neurofeedback, why Physiological Monitoring and Modulation are not Biofeedback, and how to recognize Quantum Biofeedback and LenyosysTM as pseudo-biofeedback devices.

Definitions of Biofeedback and Neurofeedback

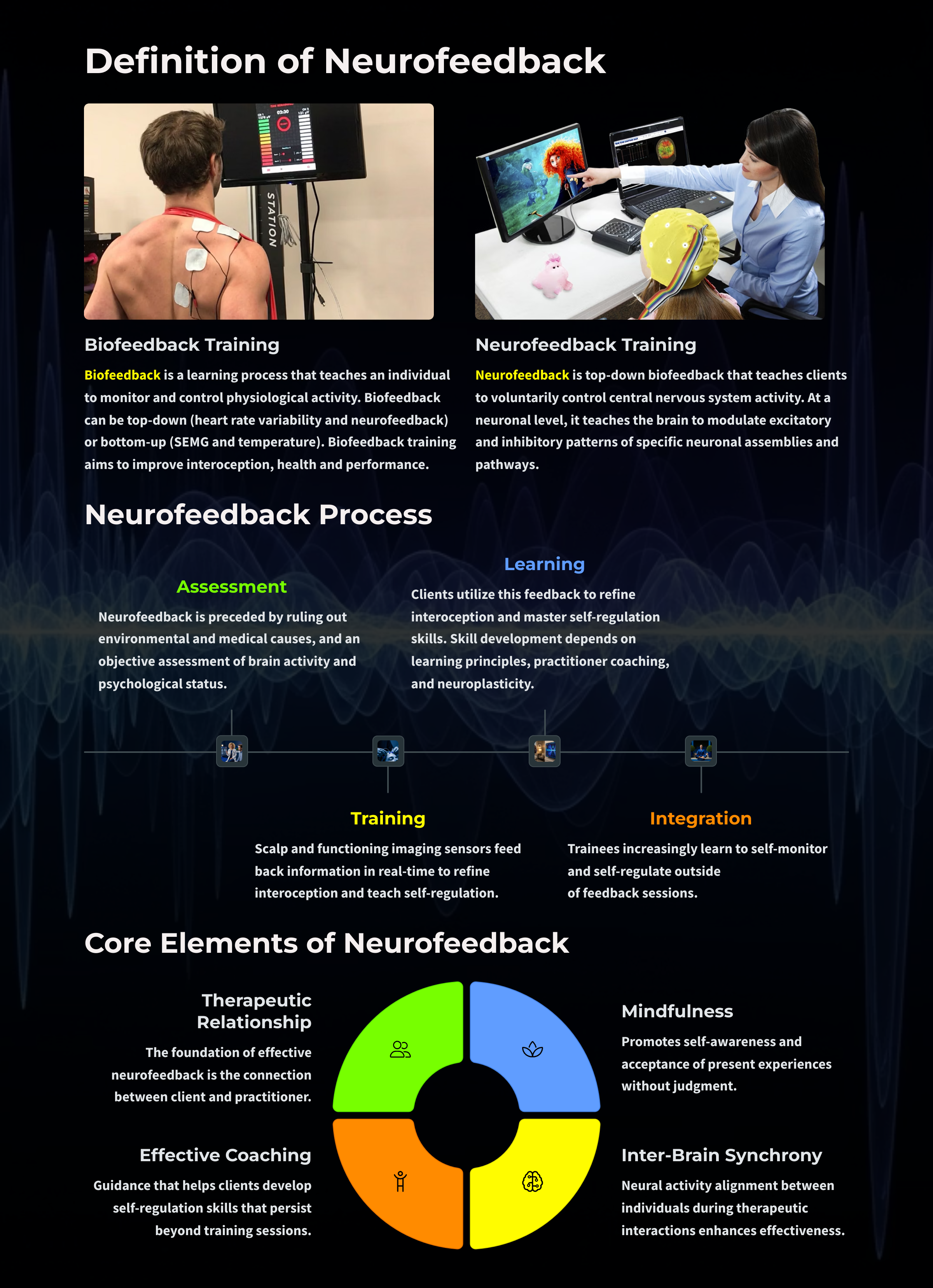

Since neurofeedback is a specialized application of biofeedback, understanding the broader concept first provides essential context. The Biofeedback Alliance and Nomenclature Task Force established the field's definitive definition in 2008 (Schwartz, 2010).

Biofeedback Alliance and Nomenclature Task Force (2008)

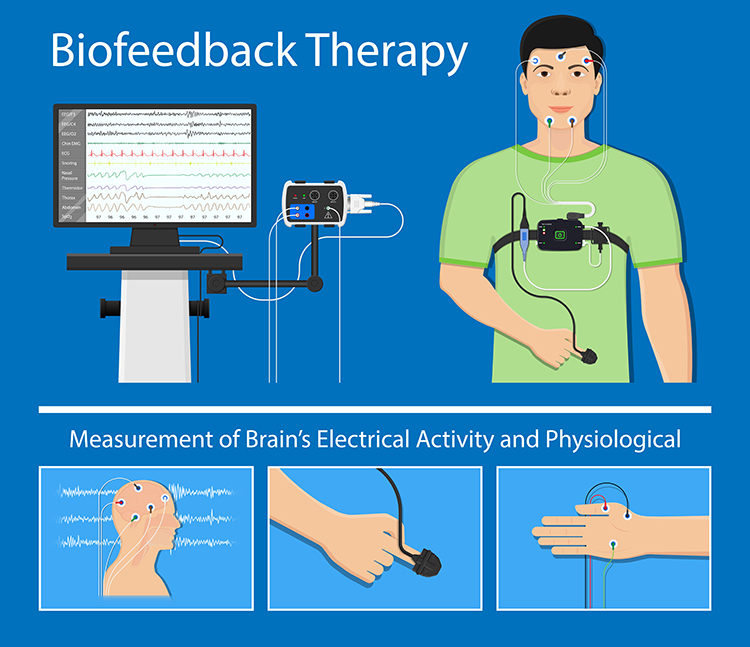

Biofeedback is a process that enables an individual to learn how to change physiological activity for the purposes of improving health and performance. Precise instruments measure physiological activity such as brainwaves, heart function, breathing, muscle activity, and skin temperature. These instruments rapidly and accurately "feed back" information to the user. The presentation of this information, often in conjunction with changes in thinking, emotions, and behavior, supports desired physiological changes. Over time, these changes can endure without continued use of an instrument.

This definition contains six essential elements worth examining individually. First, biofeedback is fundamentally a learning process that teaches individuals to control their physiological activity. Second, the training aims to improve health and performance (not merely to measure physiology). Third, instruments must rapidly monitor performance and display it back to the individual.

Fourth, the individual uses this feedback to produce physiological changes. Fifth, changes in thinking, emotions, and behavior typically accompany and reinforce physiological shifts. Sixth, and critically for clinical practice, these changes eventually become independent of external feedback from instruments. The ultimate goal is self-regulation without equipment.

The Biofeedback Certification International Alliance (BCIA) built on this foundation when addressing neurofeedback specifically in its Blueprint of Knowledge.

Biofeedback Certification International Alliance (2016) Definition of Neurofeedback

Neurofeedback is employed to modify the electrical activity of the CNS, including EEG, event-related potentials, slow cortical potentials and other electrical activity either of subcortical or cortical origin. Neurofeedback is a specialized application of biofeedback of brainwave data in an operant conditioning paradigm. The method is used to treat clinical conditions as well as to enhance performance.

Note the explicit reference to operant conditioning, the learning process through which behavior is modified by its consequences. When a client's brain produces the desired pattern and receives rewarding feedback, that pattern becomes more likely to occur again. This is the same mechanism underlying all skill acquisition, from a child learning to tie shoelaces to a surgeon perfecting a delicate technique.

The International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (ISNR) provided the most comprehensive definition, carefully delineating what makes neurofeedback both similar to and distinct from other forms of biofeedback.

International Society for Neurofeedback and Research (2010) Definition of Neurofeedback

Like other forms of biofeedback, NFT uses monitoring devices to provide moment-to-moment information to an individual on the state of their physiological functioning. The characteristic that distinguishes NFT from other biofeedback is a focus on the central nervous system and the brain. Neurofeedback training (NFT) has its foundations in basic and applied neuroscience as well as data-based clinical practice. It takes into account behavioral, cognitive, and subjective aspects as well as brain activity.

NFT is preceded by an objective assessment of brain activity and psychological status. During training, sensors are placed on the scalp and then connected to sensitive electronics and computer software that detect, amplify, and record specific brain activity. Resulting information is fed back to the trainee virtually instantaneously with the conceptual understanding that changes in the feedback signal indicate whether or not the trainee's brain activity is within the designated range. Based on this feedback, various principles of learning and practitioner guidance, changes in brain patterns occur and are associated with positive changes in physical, emotional, and cognitive states. Often the trainee is not consciously aware of the mechanisms by which such changes are accomplished although people routinely acquire a "felt sense" of these positive changes and often are able to access these states outside the feedback session.

NFT does not involve either surgery or medication and is neither painful nor embarrassing. When provided by a licensed professional with appropriate training, generally trainees do not experience negative side-effects. Typically trainees find NFT to be an interesting experience. Neurofeedback operates at a brain functional level and transcends the need to classify using existing diagnostic categories. It modulates the brain activity at the level of the neuronal dynamics of excitation and inhibition which underlie the characteristic effects that are reported.

Research demonstrates that neurofeedback is an effective intervention for ADHD and Epilepsy. Ongoing research is investigating the effectiveness of neurofeedback for other disorders such as Autism, headaches, insomnia, anxiety, substance abuse, TBI and other pain disorders, and is promising.

Being a self-regulation method, NFT differs from other accepted research-consistent neuro-modulatory approaches such as audio-visual entrainment (AVE) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) that provoke an automatic brain response by presenting a specific signal. Nor is NFT based on deliberate changes in breathing patterns such as respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) that can result in changes in brain waves. At a neuronal level, NFT teaches the brain to modulate excitatory and inhibitory patterns of specific neuronal assemblies and pathways based upon the details of the sensor placement and the feedback algorithms used, thereby increasing flexibility and self-regulation of relaxation and activation patterns.

This definition, ratified by the ISNR Board of Directors on January 10, 2009 and edited on June 11, 2010, makes a crucial distinction. Neurofeedback is a "self-regulation method" in which clients voluntarily learn to modify their central nervous system activity. This separates it sharply from neuromodulatory approaches like audio-visual entrainment (AVE) and rTMS, which alter brain function by exposing it to external stimuli. While these technologies may be valuable adjunctive procedures, they do not provide feedback of brain activity and do not teach self-regulation. The difference is between something being done to the brain versus the brain learning to regulate itself.

Perspective

Two aspects of the ISNR definition warrant closer examination for clinical practice: the question of what biofeedback and NFT actually target, and the realistic possibility of adverse effects.

The ISNR definition states that "the characteristic that distinguishes NFT from other biofeedback is a focus on the central nervous system and the brain." This framing might suggest that NFT is purely top-down interventions (targeting central nervous system frontal, parietal, and limbic networks) while other biofeedback is purely bottom-up interventions (targeting peripheral nervous system networks). The reality is more nuanced. Both NFT and traditional biofeedback involve top-down and bottom-up components because the central and peripheral nervous systems are not truly separate entities but parts of one integrated system.

Consider respiration: the central nervous system orchestrates breathing patterns, yet changes in breathing directly modulate CNS activity. Hyperventilation leading to hypocapnia (low carbon dioxide) causes a general slowing of the EEG (Takahashi, 2005). NFT and BFT both commonly incorporate breathing instruction, education about the training process, mindfulness techniques, and problem-solving strategies, all of which engage the "central nervous system and the brain."

The central nervous system (brain, spinal cord, and retina) and the peripheral nervous system (autonomic and somatic branches) cooperate through complex feedback and feedforward loops. Feedback, in cybernetic terms, refers to signals that correct small errors to prevent larger future errors in a closed system. Feedforward describes actions taken based on anticipated conditions in an open system. Together, these mechanisms create one complex integrated regulatory system.

Many clinicians treating ADHD begin with heart rate variability biofeedback, which trains clients to increase beat-to-beat variation in the time intervals between successive heartbeats. Although attention involves brainstem, subcortical, and cortical networks, successful HRVB training (often characterized as "bottom-up") may substantially improve sustained attention. In some cases, this makes NFT unnecessary. In others, the preliminary HRVB training facilitates better outcomes when NFT follows. This illustrates how approaches that might seem to target different systems actually influence the same integrated regulatory networks.

The second issue concerns the ISNR claim that "when provided by a licensed professional with appropriate training, generally trainees do not experience negative side-effects." Hammond and Kirk (2008) reviewed evidence from randomized controlled trials and clinical reports documenting that when applied incorrectly, neurofeedback can produce adverse reactions including anxiety, depression, emotional lability, explosiveness, incontinence, OCD symptoms, and sedation. This finding has important implications for training and supervision.

However, context matters. Hammond and Kirk did not systematically evaluate the severity or duration of disruptions in the anecdotal reports they collected. Most such effects appear to be temporary unless reinforced by continuing incorrect training protocols (J. S. Anderson, personal communication, June 6, 2016).

A randomized, sham-controlled, double-blind study by Rogel et al. (2015) found no statistically significant differences in reported side effects between sham and active treatment groups receiving upper alpha and SMR training, though the SMR group did report more headaches. The clinical takeaway: adverse effects are possible and warrant attention, but they are typically transient and avoidable with proper training and protocol selection.

Core Elements of Neurofeedback

Strip away the technology and what remains at the heart of effective BFT and NFT is the client-practitioner relationship. The equipment is merely a tool; the therapeutic alliance determines whether that tool produces meaningful change. Neurofeedback achieves its potential when both client and practitioner maintain mindful awareness throughout training, fostering self-observation and a sense of agency. Effective coaching, grounded in this relational foundation, is what transforms physiological feedback into lasting self-regulation, the ability to voluntarily control behavior such as increasing low-beta amplitude (Khazan, 2019).

Inter-Brain Synchrony

Emerging research reveals that the therapeutic relationship may operate through mechanisms more profound than previously recognized. Therapy creates a structured environment where patients repeatedly experience inter-brain synchrony, a phenomenon in which the neural activity of two individuals becomes aligned during social interaction (Meehan, 2025; Sened et al., 2022). This synchrony emerges in therapeutic settings when therapist and client engage in shared emotional and cognitive processes: maintaining eye contact, mirroring facial expressions, and synchronizing speech rhythms.

This mutual alignment of brain activity, termed neural coupling, facilitates deeper interpersonal connection and more effective communication. Over time, repeated neural coupling may produce lasting neurobiological adaptations, reinforcing healthier emotional and cognitive patterns. For clinicians, this suggests that the "soft skills" of therapy, including presence, attunement, and responsiveness, have hard neurobiological effects.

The implications extend further. Synchrony appears to strengthen emotional bonds and enhance cognitive flexibility. When neural coupling occurs, it facilitates better communication between brain regions involved in decision-making, problem-solving, and emotional processing. This may explain why clients experiencing high levels of synchrony with their therapists often report deeper insights, improved emotional resilience, and greater capacity for behavioral change. For practitioners across all settings, understanding and intentionally fostering this synchrony can amplify intervention effectiveness.

These findings highlight the importance of cultivating therapeutic synchrony, the alignment of emotional and cognitive processes between therapist and client, as an active component of treatment. Beyond verbal content, nonverbal elements matter enormously: body language, vocal tone, and paced responsiveness all contribute to inter-brain synchrony. Therapists who cultivate mindfulness, attunement (accurately perceiving and responding to client emotional states), and embodied presence may enhance their capacity to achieve neural synchrony with clients.

This perspective reframes relational healing as both psychological and neurobiological. Clients struggling with attachment difficulties, social challenges, or trauma may particularly benefit from interventions emphasizing relational presence (the therapist's capacity to be fully engaged and attuned in ways that foster connection and trust) and co-regulation (the process through which one person helps another regulate their emotional state through interaction). These concepts are not merely theoretical; they describe measurable neurophysiological phenomena that predict therapeutic outcomes.

Research on inter-brain plasticity suggests that repeated neural synchrony between therapist and client may produce lasting neurobiological adaptations. This emerging field reveals how the therapeutic relationship itself can reshape neural pathways, potentially explaining the mechanisms underlying successful psychotherapy outcomes (Sened et al., 2022). For practitioners, this validates what clinical intuition has long suggested: the relationship is not merely the context for intervention but may itself be a primary mechanism of change.

Biofeedback and neurofeedback are learning processes that teach self-regulation through real-time physiological feedback. The definitions from BCIA and ISNR establish that NFT is a specialized form of biofeedback focused on the central nervous system, though both approaches influence an integrated nervous system through top-down and bottom-up pathways. The therapeutic relationship forms a crucial foundation for positive outcomes, with emerging research on inter-brain synchrony revealing the neurobiological mechanisms through which relational processes drive change.

Physiological Monitoring and Modulation Are Not Biofeedback

Physiological monitoring, the detection and recording of biological activity like blood pressure or brain waves, represents only one component of the biofeedback process. Understanding this distinction prevents conceptual confusion that can affect clinical practice and scope of practice considerations.

Consider a familiar scenario: when a nurse measures your blood pressure, that is physiological monitoring. The measurement captures biological data but does nothing to help you change it. Biofeedback occurs only when the nurse reports those values back to you: "Your blood pressure was 120/70." That simple act of sharing the information closes the feedback loop, enabling you to refine your self-awareness and potentially influence your physiology. Without the feedback component, no learning can occur.

Mini-Lecture: Physiological Monitoring and Modulation

Similarly, modulation, stimulating the nervous system to produce psychophysiological change, is not biofeedback because it acts on the body rather than providing information about its performance. The direction of action is fundamentally different: biofeedback informs the individual so they can change themselves; modulation changes the individual directly.

Physical therapy offers a clear illustration. A therapist might treat back pain using electrical muscle stimulation, a modality that delivers current to postural muscles, fatiguing them so they cannot produce painful spasms. This intervention does something to the muscles. Once stimulation brings spasms under control, the therapist can initiate surface electromyographic (SEMG) biofeedback, which teaches the patient to increase awareness and voluntary control of postural muscle contraction. The SEMG training provides information about the muscles so the patient can learn to regulate them independently.

The same logic applies to devices that input signals into the central nervous system. These technologies, collectively termed entrainment devices, include Audio-Visual Entrainment (AVE), Cranial Electrotherapy Stimulation (CES), repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS), repetitive Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (rTDCS), and pulsed ElectroMagnetic Frequency Stimulation (pEMF), among others. Each delivers some form of energy to the nervous system to provoke a response.

These interventions may provide real clinical benefit and can complement biofeedback effectively. However, since they do not provide information directly to the individual within a learning paradigm, they are not biofeedback. The distinction matters: they represent treatment, not training. Patients receiving rTMS are not learning a skill they can replicate independently; they are receiving a stimulus that produces an effect.

For this reason, practitioners should confirm that using these modalities falls within their scope of practice. The regulatory and credentialing requirements may differ substantially from those governing biofeedback. The David Delight Pro, an AVE device, is shown below.

Physiological monitoring becomes biofeedback only when information flows back to the individual, enabling learning. Modulation and entrainment devices stimulate the nervous system directly but do not teach self-regulation because they provide no performance feedback. These distinctions carry practical implications for understanding scope of practice and selecting appropriate interventions for specific clinical goals.

Quantum Biofeedback and LenyosysTM

The previous section established that modulation is not biofeedback. This distinction becomes critically important when evaluating devices that use "biofeedback" in their marketing despite lacking the essential feedback component. Slawecki (2009) provided guidance for consumers and practitioners in "How to Distinguish Legitimate Biofeedback/Neurofeedback Devices."

The September 3, 2009 Seattle Times published an investigative report on these devices: "Miracle Machines: The 21st-Century Snake Oil." The article documented how marketing terminology can mislead both consumers and well-intentioned practitioners.

The core principle is straightforward: appending "biofeedback" to a product name does not make it biofeedback. Exposing clients to electromagnetic fields, regardless of how the device is labeled, constitutes modulation. Since genuine biofeedback provides clients with real-time performance information that guides self-regulation learning, devices that lack this feedback mechanism fall outside the definition. Two examples illustrate this problem.

Quantum Biofeedback

Quantum Biofeedback devices (marketed under names including EPFX, SCIO, XRROID, and QXCI) do not provide individuals with immediate information about their performance. Marketers claim these instruments monitor, diagnose, and correct cellular abnormalities at a "quantum level" without providing peer-reviewed evidence supporting these claims. Critics raise serious concerns that treatment with these devices may generate false diagnoses and delay appropriate medical care for genuine disorders.

The following promotional text, retrieved from the Empowering Change in You website on December 27, 2009, illustrates how these devices are marketed. Note the disclaimer acknowledging the device does not "cure" medical conditions and the framing of effects as resulting from stress management:

The function of the Quantum Biofeedback/EPFX is similar to a virus-scan on a computer. It focuses on your energetic body, which offers a more complete view of each facet of your health. Based on Quantum Physics, it runs a comprehensive test that measures the body's frequencies. The system then contributes frequencies designed to resonate within the body, thus creating balance. The human body is composed of a biochemical structure and an electromagnetic field. It performs best when these functions are balanced with one another and in complete harmony. Unfortunately, the daily stresses of life that confront each and every one of us takes its toll on the human body. Stress reduction is essential for wellness. This energy work is non-invasive. It is important to remember that energetic medicine does not "cure" health problems. It addresses them specifically by making energetic corrections and rebalancing the system through stress management.

LenyosysTM

LenyosysTM markets its pulsed electromagnetic technology as a "body-biofeedback modality":

Ideal as a complement to neurofeedback and biofeedback therapy, BRT is a body-biofeedback modality that helps to address the physical and somatic symptoms of both simple and complex health issues including digestive problems, systemic inflammation, muscle and joint aches, drug and alcohol addiction, allergies and hypersensitivities, stress, trauma and chronic illness. Whether used before, right after or in between sessions, BRT works in tandem with neurofeedback and biofeedback to create synergies that relax the client, enhance the therapy session and improve end results.

Despite the terminology, pulsed electromagnetic treatment is modulation, not biofeedback. The device delivers electromagnetic energy to the body; it does not provide information about physiological performance that would enable learning and self-regulation. Rather than presenting double-blind studies demonstrating their specific product's effectiveness, the company provides references for Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy (PEMF) and magnetism applied to various conditions. This approach, citing research on a general technology class rather than the specific marketed device, does not establish the claimed benefits.

Legitimate biofeedback provides real-time performance information that guides self-regulation learning. Devices that expose clients to electromagnetic fields without providing feedback are modulation technologies, not biofeedback, regardless of marketing terminology. Consumers and practitioners should evaluate device claims against peer-reviewed research specific to the product being marketed, not general technology categories. When in doubt, ask a simple question: does this device show the client information about their physiological performance that enables them to learn? If not, it is not biofeedback.

Check Your Understanding

- What are the six main elements of the Biofeedback Alliance and Nomenclature Task Force definition of biofeedback?

- How does neurofeedback differ from neuromodulatory approaches like AVE and rTMS?

- Why is physiological monitoring alone not considered biofeedback?

- What distinguishes legitimate biofeedback devices from pseudo-biofeedback devices like Quantum Biofeedback?

- How do inter-brain synchrony and therapeutic attunement contribute to effective neurofeedback outcomes?

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, consider how you would explain neurofeedback to a new client who arrives at your clinic knowing nothing about the field. How would you describe what happens during a session? How would you explain the relationship between biofeedback and neurofeedback training, and why that relationship matters for their treatment?

Glossary

adverse reactions: iatrogenic effects such as anxiety and sedation that may be associated with BFT and NFT when protocols are applied incorrectly.

attunement: the process by which a therapist accurately perceives and responds to a client's emotional state, fostering a therapeutic interaction that validates the client's internal experience.

biofeedback: a learning process characterized by six elements: (1) teaching an individual to control physiological activity, (2) aiming to improve health and performance, (3) using instruments that rapidly monitor and display performance, (4) enabling the individual to use feedback to produce physiological changes, (5) accompanying changes in thinking, emotions, and behavior that reinforce physiological shifts, and (6) achieving changes that become independent of external feedback. Information about psychophysiological performance is obtained by noninvasive monitoring and used to help individuals achieve self-regulation through learning resembling motor skill acquisition.

bottom-up interventions: training approaches that directly target peripheral nervous system networks, though these also influence central nervous system function through integrated feedback loops.

central nervous system: the division of the nervous system comprising the brain, spinal cord, and retina.

classical conditioning: an unconscious associative learning process that modifies reflexive behavior and prepares us to respond rapidly to future situations.

co-regulation: the process through which one person helps another regulate their emotional state through interaction and connection, ultimately aiding development of self-regulation skills.

electroencephalograph: an instrument that measures brain electrical activity, including brainwaves.

electromyograph: an instrument that measures skeletal muscle action potentials.

entrainment devices: instruments that input signals such as light, sound, or electricity into the central nervous system, including AVE, CES, rTMS, rTDCS, and pEMF devices.

feedback: in cybernetic theory, signals that correct small errors to prevent larger future errors in a closed system.

feedforward: in cybernetic theory, actions performed based on anticipated conditions in an open system.

heart rate variability biofeedback: training that displays and rewards increases in beat-to-beat changes in heart rate, including changes in the RR intervals between consecutive heartbeats.

homeostasis: a state of dynamic constancy achieved by stabilizing conditions around a setpoint (whose value may change over time), as proposed by Bernard and Cannon.

inter-brain plasticity: the capacity of the brain to adapt and change based on repeated neural synchrony with another person, potentially explaining mechanisms underlying psychotherapy outcomes.

inter-brain synchrony: the synchronization of brain activity between two individuals during social or therapeutic interactions, associated with improved therapeutic outcomes.

mindfulness: accepting and non-judgmental focus of attention on the present moment, helping clients distinguish between what can and cannot be changed.

modulation: stimulating the nervous system to produce psychophysiological change, distinct from biofeedback because it acts on the body rather than providing performance information.

neural coupling: the synchronization of brain activity between two individuals during social or therapeutic interactions, facilitating deeper interpersonal connection.

neurofeedback: information about EEG activity obtained through noninvasive monitoring and used to help individuals achieve self-regulation through a learning process resembling motor skill acquisition; a specialized application of biofeedback focused on central nervous system activity.

operant conditioning: an unconscious associative learning process that modifies the form and occurrence of voluntary behavior by manipulating its consequences.

peripheral nervous system: the nervous system subdivision including autonomic and somatic branches, cooperating with the central nervous system through feedback and feedforward loops.

physiological monitoring: measurement of biological activity such as EEG or blood pressure, which becomes biofeedback only when information is fed back to the individual.

relational presence: a therapist's capacity to be fully engaged and attuned to a client in ways that foster connection and trust, creating a secure framework for therapeutic change.

self-regulation: voluntary control of behavior, such as intentionally increasing low-beta amplitude or achieving a relaxed physiological state.

therapeutic synchrony: the alignment of emotional and cognitive processes between therapist and client that enhances the therapeutic process and may be reflected in measurable inter-brain synchrony.

top-down interventions: training approaches that directly target central nervous system frontal, parietal, and limbic networks, though these also influence peripheral function through integrated regulatory systems.

References

Biofeedback Certification International Alliance. (2016). Blueprint of knowledge statements for board certification in neurofeedback. http://www.bcia.org/files/public/EEGBlueprint.pdf

Collura, T. F. (2014). Technical foundations of neurofeedback. Routledge.

Hammond, D. C., & Kirk, L. (2008). First, do not harm: Adverse effects and the need for practice standards in neurofeedback. Journal of Neurotherapy, 12(1), 79-88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874200802219947

International Society for Neurofeedback and Research. (2016). Definition of neurofeedback. http://www.isnr.org/#!neurofeedback-introduction/c18d9

Khazan, I. (2013). The clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Khazan, I. (2019). Biofeedback and mindfulness in everyday life: Practical solutions for improving your health and performance. W. W. Norton & Company.

Meehan, Z. M. (2025). 5-min science: Inter-brain plasticity can enhance psychotherapy. https://www.biosourcesoftware.com/post/5-min-science-inter-brain-plasticity-can-enhance-psychotherapy

Peper, E., Shumay, D. M., & Moss, D. (2012). Change illness beliefs with biofeedback and somatic feedback. Biofeedback, 40(4), 154–159. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-40.4.02

Rogel, A., Guez, J., Getter, N., Keha, E., Cohen, T., Amor, T., & Todder, D. (2015). Transient adverse side effects during neurofeedback training: A randomized, sham-controlled, double blind study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 40(3), 209-218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-015-9289-6

Schwartz, M. S. (2010). A new improved universally accepted official definition of biofeedback: Where did it come from? Why? Who did it? Who is it for? What's next? Biofeedback, 38(3), 88–90. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-38.3.88

Sened, H., Zilcha-Mano, S., & Shamay-Tsoory, S. (2022). Inter-brain plasticity as a biological mechanism of change in psychotherapy: A review and integrative model. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 16, 955238. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.955238

Slawecki, T. (2009). How to distinguish legitimate biofeedback/neurofeedback devices. Biofeedback, 37(3), 118–120.

Takahashi, T. (2005). Activation methods. In E. Niedermeyer & F. Lopes da Silva (Eds.), Electroencephalography: Basic principles, clinical applications, and related fields (5th ed.). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Thompson, M., & Thompson, L. (2016). The neurofeedback book: An introduction to basic concepts in applied psychophysiology (2nd ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Return to Top