Autonomic Nervous System Anatomy and Physiology

What You Will Learn

Every second, your autonomic nervous system orchestrates a symphony of physiological adjustments, regulating heart rate, digestion, and stress responses without conscious effort. This chapter explores how three autonomic branches (sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric) work together in ways that challenge popular misconceptions. You will discover why the notion of a "bad" sympathetic system and "good" parasympathetic system fundamentally misunderstands autonomic physiology. Stephen Porges' polyvagal theory reveals how the vagus nerve contains specialized subsystems governing everything from social engagement to freeze responses. By the end of this chapter, you will understand how the autonomic nervous system maintains homeostasis and why this knowledge is essential for effective HRV biofeedback training with your clients.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) influences heart rate through multiple mechanisms operating on different timescales. The parasympathetic branch generates the rapid, beat-to-beat variability that clinicians measure as HRV. The sympathetic branch regulates slower heart rate changes unfolding across several beats. Hormones including angiotensin, epinephrine, and vasopressin modulate heart rate over periods ranging from seconds to hours (Karemaker, 2020). Understanding these different timescales helps explain why HRV biofeedback training targets specific physiological mechanisms.

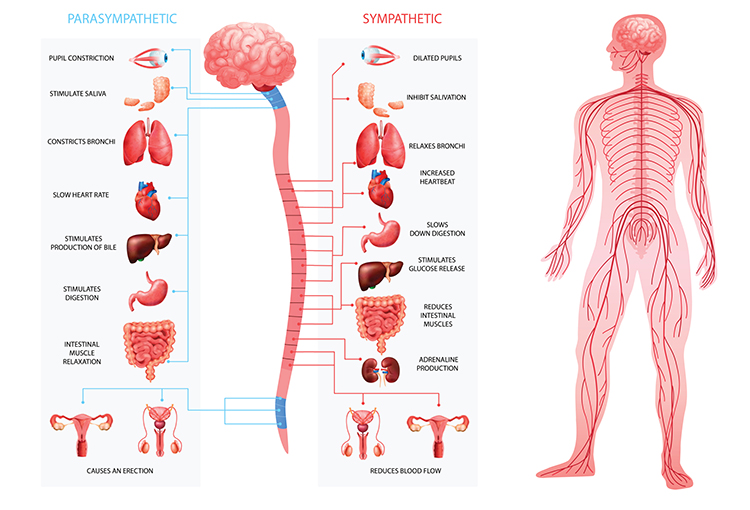

The three autonomic branches work both cooperatively and competitively to maintain homeostasis, the dynamic equilibrium that keeps physiological variables within healthy ranges. Contrary to popular stress management books, the sympathetic branch is not our enemy, just as the parasympathetic branch is not always our ally. Consider this simple fact: you cannot rise from a couch without fainting or sprint across a field without increased sympathetic activation. Both branches serve essential adaptive functions.

Research confirms this balanced perspective. Brindle and colleagues (2014) conducted meta-analyses examining how the cardiovascular system responds to acute psychological stress. Their findings revealed that both beta-adrenergic activation (a sympathetic effect mediated by receptors that accelerate heart rate and increase cardiac contractility) and vagal withdrawal (reduced parasympathetic influence on the heart) contribute to cardiovascular reactivity in roughly equal measure. This finding has important implications: when your clients experience stress, their bodies are not simply "going sympathetic" but rather orchestrating a coordinated response involving both autonomic branches.

When clients use excessive effort during slow-paced breathing exercises, you may observe their fingers cooling and sweating (sympathetic responses) while their HRV simultaneously decreases (vagal withdrawal). This dual response challenges the common assumption that stress responses involve either sympathetic activation or vagal withdrawal, but not both. Effective training helps clients find the relaxed effort that maximizes HRV without triggering competing sympathetic activation.

This unit challenges the simplistic belief that acute stressors trigger only sympathetic fight-or-flight or parasympathetic vagal withdrawal responses. The autonomic branches do not operate as independent systems with separate on-off switches. Instead, the ANS integrates sympathetic and parasympathetic activity for nuanced control that adapts to constantly changing demands.

The accentuated antagonism model captures this complexity. According to this framework, the background activity of one branch moderates brief changes in the other (Uijtdehaage & Thayer, 2000). Think of it as a dynamic conversation between branches rather than a simple toggle between two states. This concept has direct relevance for biofeedback: training can enhance this regulatory dialogue, improving your clients' capacity for flexible autonomic adjustment.

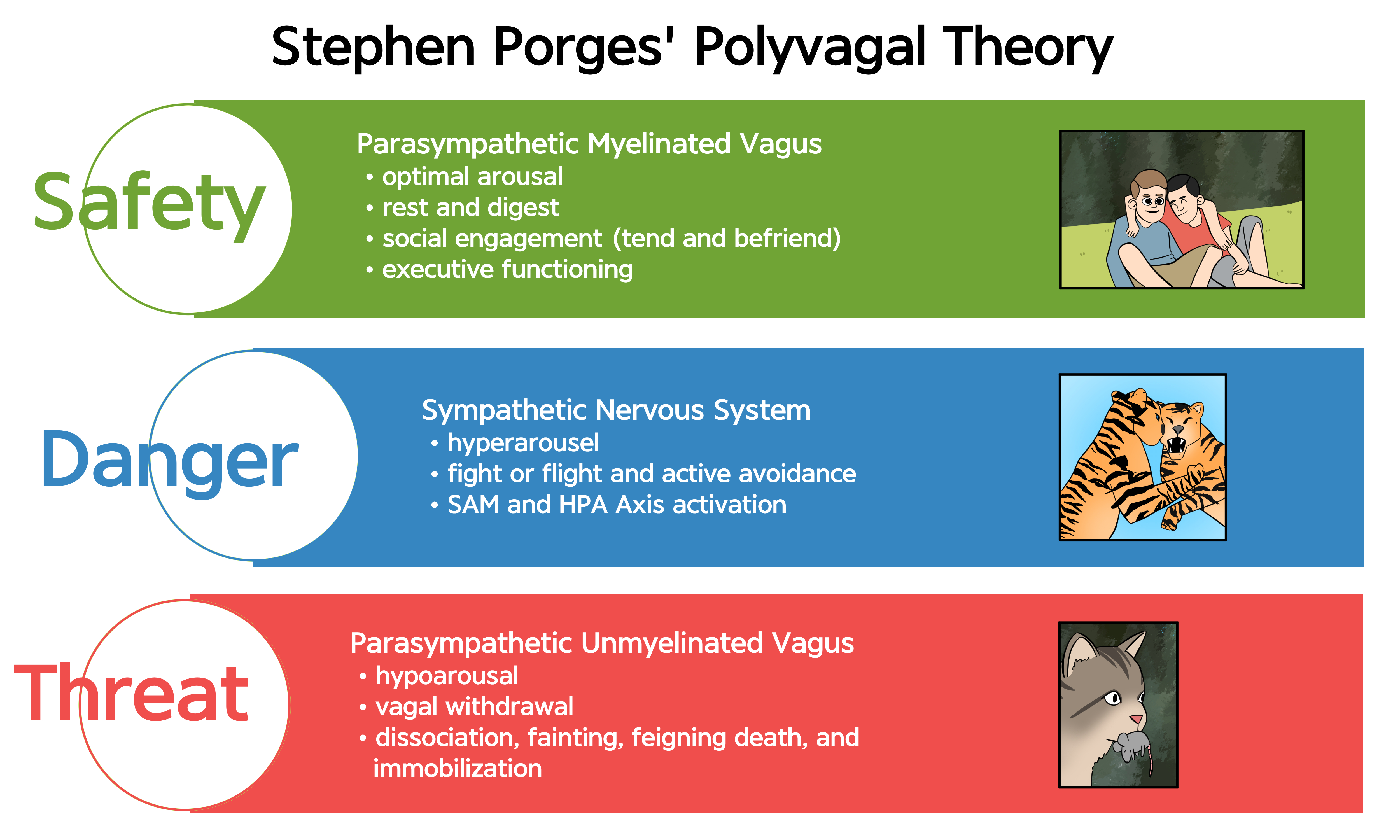

Stephen Porges (2011) further expanded our appreciation of parasympathetic versatility through polyvagal theory. This framework proposes that we respond to everyday stressors with vagal withdrawal, reducing the calming influence of the parasympathetic system. In extreme cases of perceived life threat, we may activate a phylogenetically older response involving immobilization, feigning death, passive avoidance, or shutdown. When we perceive safety, we may socially engage (supported by the hormone oxytocin) and practice self-regulation skills. These different response patterns have particular relevance for treating trauma-related conditions like PTSD.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses I. HRV Anatomy and Physiology: C. ANS Anatomy and Physiology.

Professionals completing this module will be able to discuss the anatomy and physiology of the three autonomic branches, and the distribution and functions of the vagus nerve.

This unit covers the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS), Sympathetic Division, Parasympathetic Division, The Relationship Between the Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Branches, Porges' Polyvagal Theory, and the Enteric Division.

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter Lecture

The Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems Form the Foundation

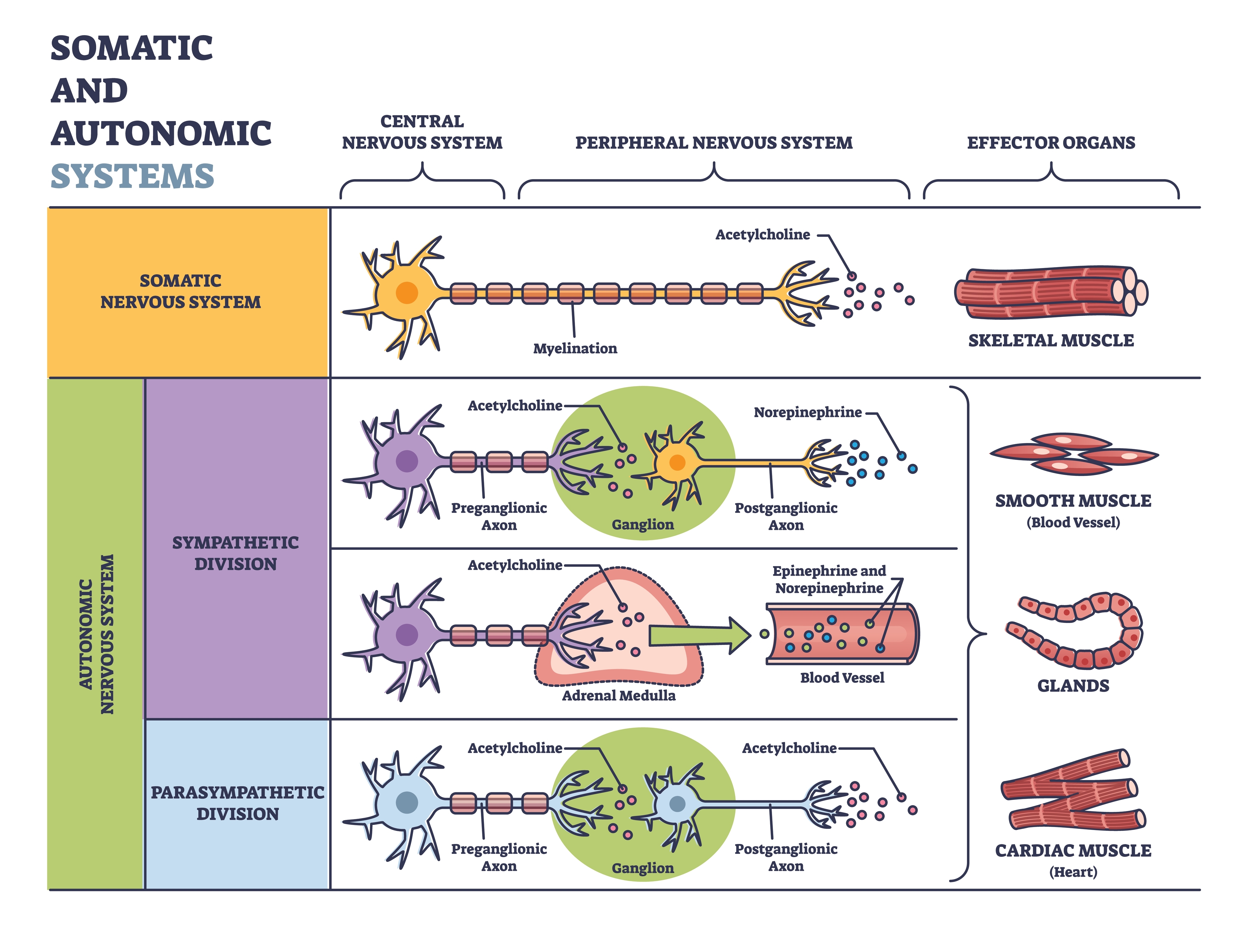

Before examining autonomic function, we need to understand its place within the broader nervous system organization. The central nervous system (CNS) comprises the brain, spinal cord, and retina. The peripheral nervous system (PNS) encompasses everything outside these structures, including the somatic nervous system and all three branches of the autonomic nervous system (Breedlove & Watson, 2023). This organizational framework helps clinicians understand how signals flow between central command centers and peripheral target organs.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems

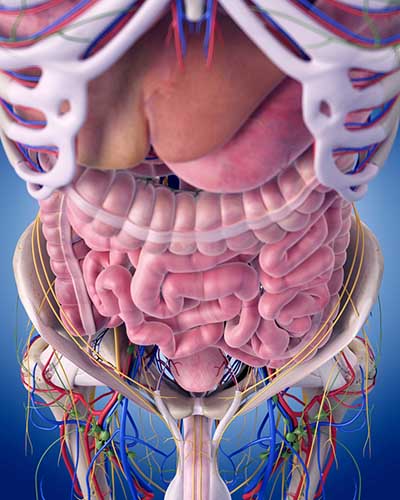

The somatic nervous system controls the contraction of skeletal muscles (the muscles you consciously move) and transmits somatosensory information (touch, pressure, pain, temperature, and body position) to the CNS. The autonomic nervous system regulates cardiac muscle, smooth muscle (found in blood vessels and digestive organs), and glands. It also transmits sensory information from internal organs to the CNS and innervates muscle spindles, the stretch receptors that help maintain posture and coordinate movement.

The autonomic nervous system divides into three main branches: sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric. Check out the YouTube video The Autonomic Nervous System.

Preganglionic and Postganglionic Neurons Relay Commands

Autonomic signals travel through a two-neuron chain that relays commands from the CNS to target organs. Understanding this relay system helps explain why autonomic responses differ in speed and duration. Preganglionic axons originate in the CNS (specifically the brainstem or spinal cord) and travel to clusters of nerve cell bodies called ganglia located in the PNS. These preganglionic neurons release the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) to communicate with the second neuron in the chain.

Postganglionic axons originate in these autonomic ganglia and project directly to target organs including the heart, lungs, and digestive system. The neurotransmitter they release depends on the branch: parasympathetic postganglionic neurons release ACh, while most sympathetic postganglionic neurons release norepinephrine. This neurochemical difference underlies the distinct effects of each branch.

The central nervous system includes the brain, spinal cord, and retina, while the peripheral nervous system contains the somatic and autonomic divisions. The autonomic nervous system has three branches (sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric) that use preganglionic and postganglionic neurons to relay commands to target organs. Understanding this two-neuron relay system helps explain the timing and duration of autonomic responses.

The Sympathetic Division Prepares You for Action

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) readies the body for action and regulates activities that expend stored energy. When patients describe feeling "wired" or "amped up," they are often describing sympathetic activation. This branch orchestrates the coordinated physiological changes needed to respond effectively to challenges, whether running from danger or simply standing up from a chair.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Sympathetic Nervous System Function

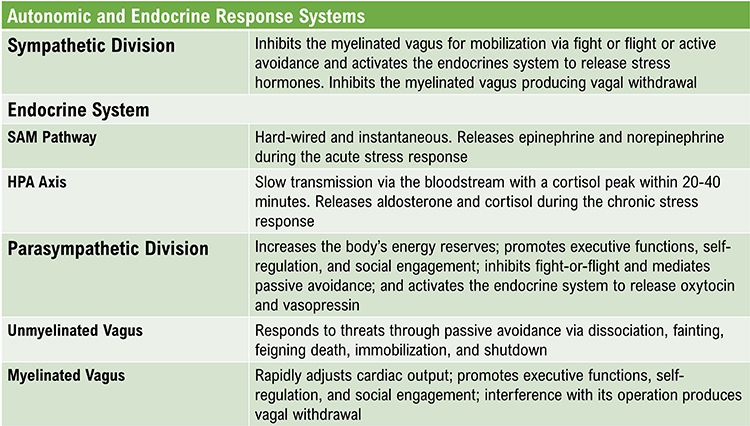

Working in concert with the endocrine system, the SNS responds to perceived threats through mobilization, fight-or-flight, and active avoidance behaviors. An important temporal distinction separates sympathetic from parasympathetic effects: the SNS responds more slowly (requiring more than 5 seconds to produce measurable changes) but sustains its effects for longer periods. In contrast, the parasympathetic vagus system acts more rapidly (within 1 second) but with more transient effects (Nunan et al., 2010). This timing difference has practical implications for biofeedback training, where the goal is often to shift the balance toward faster-acting parasympathetic regulation.

Porges (2011) theorized that the SNS inhibits the unmyelinated vagus (the dorsal vagal complex, discussed in detail later) to mobilize us for action. This inhibition releases the "vagal brake" that normally slows the heart, allowing heart rate to increase rapidly.

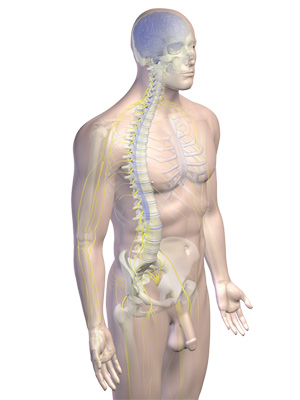

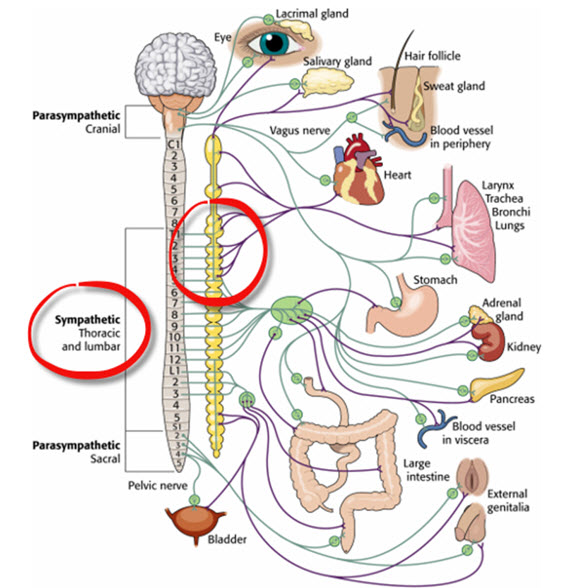

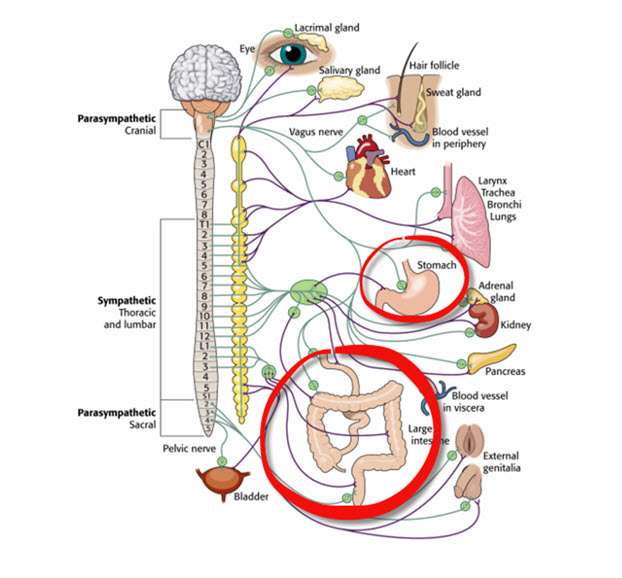

Sympathetic Neurons Are Organized in the Thoracolumbar Region

SNS cell bodies reside in the gray matter of specific spinal cord segments: from the first thoracic segment (T1) to the second lumbar segment (L2). Because of this anatomical distribution, the sympathetic division is described as thoracolumbar. This regional organization contrasts with the parasympathetic division's craniosacral distribution, discussed later.

Sympathetic preganglionic neurons originate in the CNS and exit the spinal cord via the ventral root. Most of these axons synapse with ganglia in the sympathetic chain, a paired structure running parallel to the spinal cord on each side. This chain arrangement enables the coordinated, widespread responses characteristic of sympathetic activation.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Sympathetic Nervous System Organization

The sympathetic chain's architecture supports complex signaling patterns. Preganglionic neurons branch extensively and communicate with sympathetic ganglia through two mechanisms. Divergence occurs when one preganglionic neuron synapses with multiple ganglia, spreading its influence widely. Convergence occurs when many preganglionic neurons from different spinal levels synapse with a single ganglion cell, integrating inputs from multiple sources.

Both divergence and convergence produce mass activation, enabling integrated sympathetic action such as simultaneous increases in blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration rate during emergencies. Importantly, this degree of integration occurs primarily during emergency responses, not at rest (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2021). This distinction matters clinically: even when sympathetic tone is elevated, the system maintains some selectivity in its targeting.

SNS preganglionic axons also directly innervate the adrenal medulla, the central portion of the adrenal gland located atop each kidney. When stimulated, the adrenal medulla releases the hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine into the bloodstream, reinforcing and prolonging sympathetic activation of visceral organs. This hormonal reinforcement helps explain why stress responses can persist even after the initial trigger has passed.

A patient with essential hypertension may show chronically elevated sympathetic tone that persists even during rest. The adrenal medulla's hormonal contribution helps explain why stress-induced blood pressure elevations can outlast the stressor itself. HRV biofeedback training helps these patients restore parasympathetic influence, providing a counterbalance to sustained sympathetic activation.

The release of epinephrine and norepinephrine produces several metabolic effects: increased blood flow to muscles, conversion of stored nutrients into glucose, and enhanced skeletal muscle contraction capacity. Meanwhile, postganglionic neurons exit the sympathetic chain and project axons to target organs including the heart, lungs, and sweat glands.

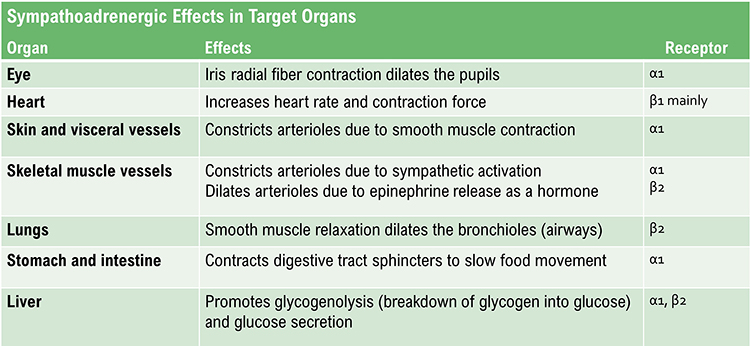

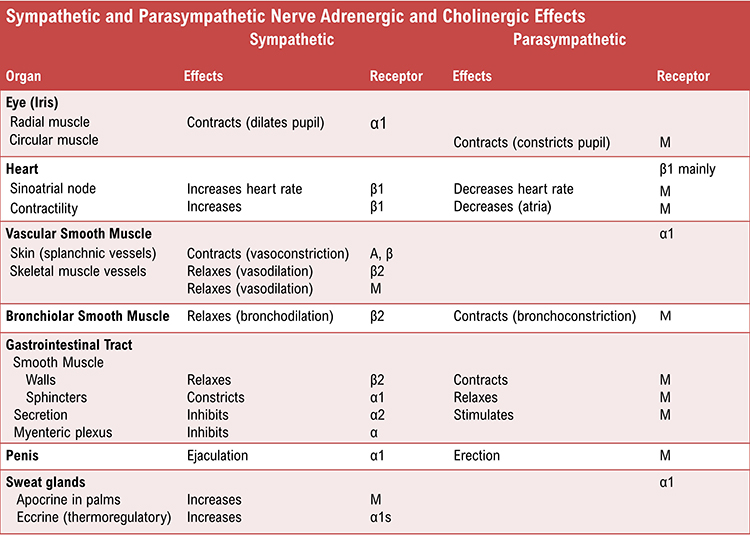

Adrenergic receptors (receptors that respond to epinephrine and norepinephrine) produce their effects through G-proteins, intracellular signaling molecules that amplify and diversify the hormonal signal. The following table, adapted from Fox and Rompolski (2022), summarizes key adrenergic effects.

Some Organs Receive Sympathetic Innervation Only

Several target structures receive exclusively sympathetic innervation, with no parasympathetic counterpart. These include the adrenal medulla, arrector pili muscles (the tiny muscles that produce "goosebumps"), cutaneous sweat glands, and most blood vessels (Fox & Rompolski, 2022). For these structures, autonomic regulation depends entirely on adjusting the rate of sympathetic firing, not on balancing opposing inputs.

Preganglionic and Postganglionic Neurotransmitters Differ

SNS preganglionic and postganglionic axons release different neurotransmitters. All SNS preganglionic axons secrete acetylcholine, the same transmitter used throughout the parasympathetic system. However, most SNS postganglionic axons secrete norepinephrine. This switch from cholinergic (acetylcholine-releasing) to adrenergic (norepinephrine-releasing) transmission at the ganglia distinguishes sympathetic from parasympathetic signaling.

Two important exceptions exist: the postganglionic axons innervating sweat glands and skeletal muscle blood vessels release acetylcholine rather than norepinephrine (Fox & Rompolski, 2022). These exceptions help explain why emotional sweating and muscle vasodilation can accompany stress responses.

The Sympathetic Branch and Heart Rate Variability

Heart rate variability (HRV) consists of the beat-to-beat changes in heart rate, including changes in the time intervals between consecutive heartbeats. The relationship between sympathetic activity and HRV is more nuanced than often assumed. Contrary to earlier beliefs, the SNS does not appear to contribute significantly to the low-frequency (LF; 0.04-0.15 Hz) component of HRV under resting conditions. This finding has important implications for interpreting HRV data in clinical practice.

Stephen Porges has emphasized that most stressors do not require the sympathetic branch's intensive energy expenditure during fight-or-flight. Instead, he argues that when we perceive daily stressors as threatening, this perception primarily causes vagal withdrawal rather than full sympathetic activation. In other words, the body often responds to stress by releasing the "vagal brake" rather than pressing the "sympathetic accelerator."

In vagal withdrawal, we disengage parasympathetic control of our viscera (large internal organs) and reduce HRV. We shift from a calm, socially engaged state toward readiness for mobilization. From there, we may progress to either fight or flight (mediated by the sympathetic nervous system) or, in extreme cases, immobilization.

Consider a veteran with PTSD who experiences hypervigilance in crowded spaces. According to polyvagal theory, the initial response may involve vagal withdrawal (reduced HRV, increased heart rate) as the nervous system prepares for potential action. If the perceived threat intensifies, sympathetic activation increases further. HRV biofeedback training helps such clients restore vagal tone, essentially strengthening the "brake" that can modulate these stress responses.

Vagal withdrawal produces characteristic HRV frequency changes: increased power in the very-low-frequency (VLF) band (0.04 Hz and below) and decreased power in the high-frequency (HF) band (0.15 to 0.40 Hz). Understanding these frequency signatures helps clinicians interpret assessment data and track training progress.

The sympathetic nervous system prepares you for action through mass activation of multiple organ systems. SNS preganglionic neurons originate in the thoracolumbar spinal cord and release acetylcholine, while most postganglionic neurons release norepinephrine. The SNS responds more slowly than the parasympathetic system and contributes to stress responses alongside vagal withdrawal. Understanding these mechanisms helps explain why stress responses often involve both autonomic branches rather than simple sympathetic activation.

Comprehension Questions: Sympathetic Division

- What spinal cord segments contain sympathetic nervous system cell bodies, and why is this distribution clinically relevant?

- How do divergence and convergence in the sympathetic chain produce mass activation, and when does this occur?

- Why does the SNS not contribute significantly to the low-frequency component of HRV under resting conditions?

- What is the difference between neurotransmitters released by SNS preganglionic versus postganglionic axons, and what exceptions exist?

The Parasympathetic Division Conserves and Restores Energy

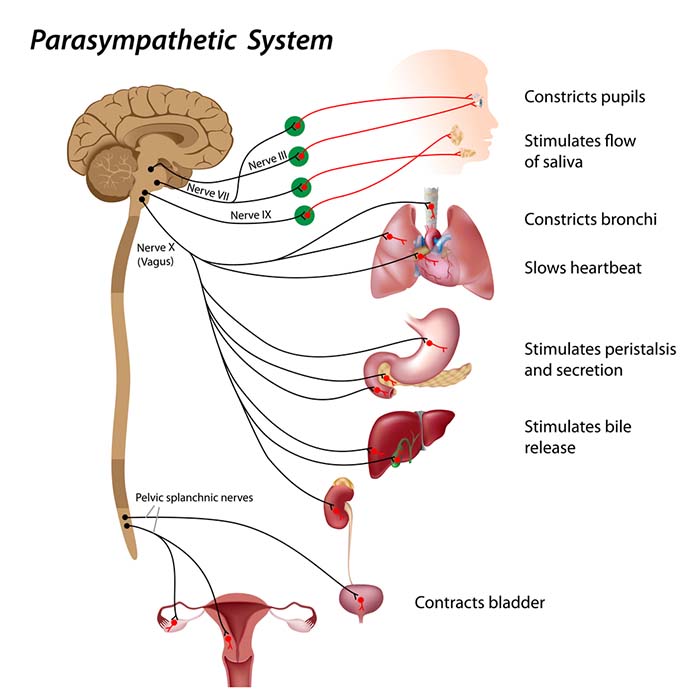

The parasympathetic division regulates activities that conserve and restore the body's energy reserves. Its effects include increased salivation, enhanced gastric (stomach) and intestinal motility, gastric juice secretion, and increased blood flow to the gastrointestinal system. Clinicians often summarize these functions as "rest and digest," contrasting with the sympathetic "fight or flight" response.

However, as we will see when examining Porges' polyvagal theory, the parasympathetic system serves functions well beyond energy conservation. This system is also intimately involved in self-regulation, social engagement, and certain passive responses to extreme threats. Understanding this broader range of parasympathetic functions enriches clinical practice.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Parasympathetic Nervous System Function

Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Restores Healthy Parasympathetic Activity

Heart rate variability biofeedback uses slow-paced breathing and rhythmic skeletal muscle contraction to restore healthy parasympathetic activity. This restoration matters because chronic stress, anxiety, depression, and many medical conditions are associated with reduced parasympathetic tone and diminished HRV.

Patients with coronary artery disease often show reduced HRV, reflecting diminished parasympathetic protection of the heart. Research demonstrates that low HRV predicts adverse cardiac events. HRV biofeedback training can help restore vagal tone, potentially improving both the physiological measure and clinical outcomes. Similar benefits have been observed in patients recovering from myocardial infarction.

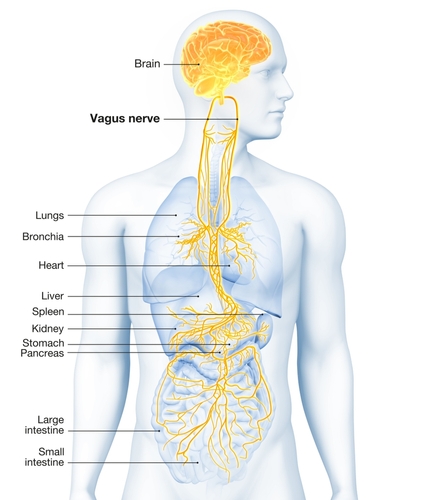

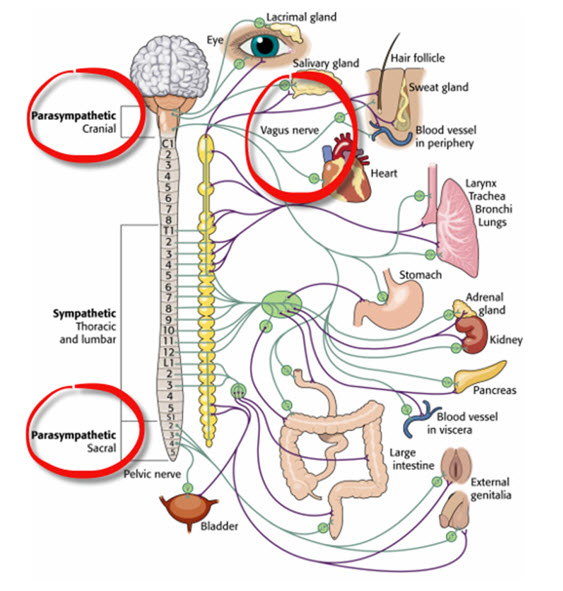

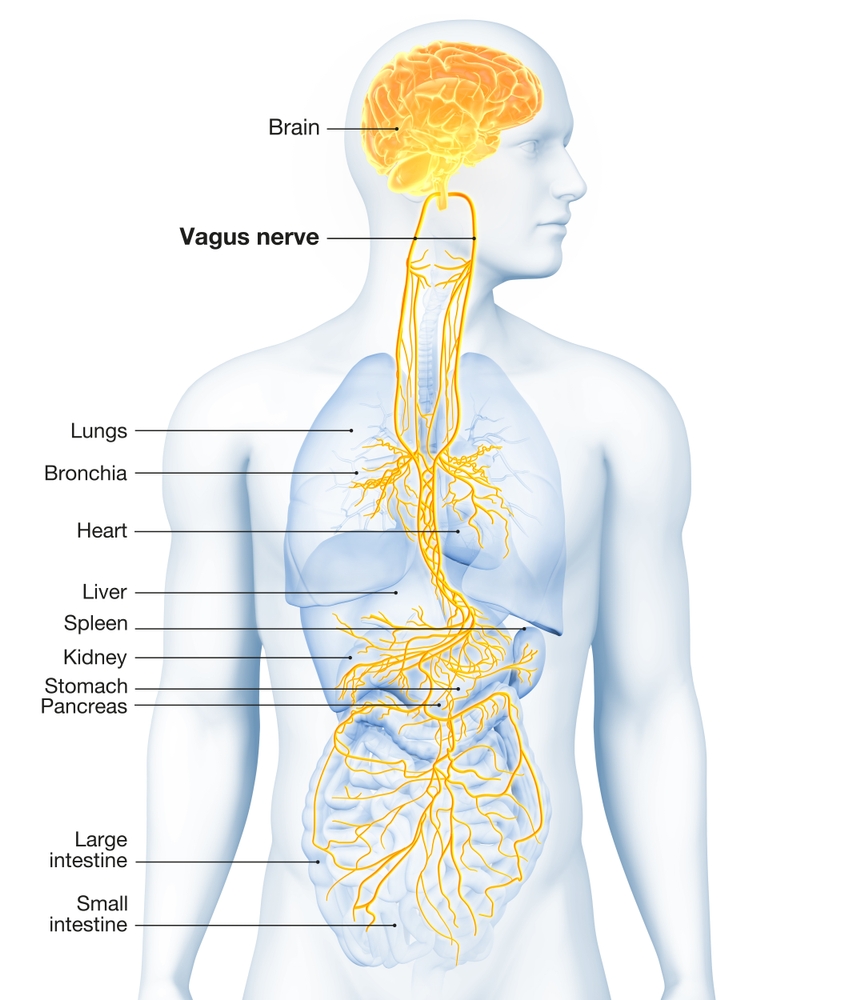

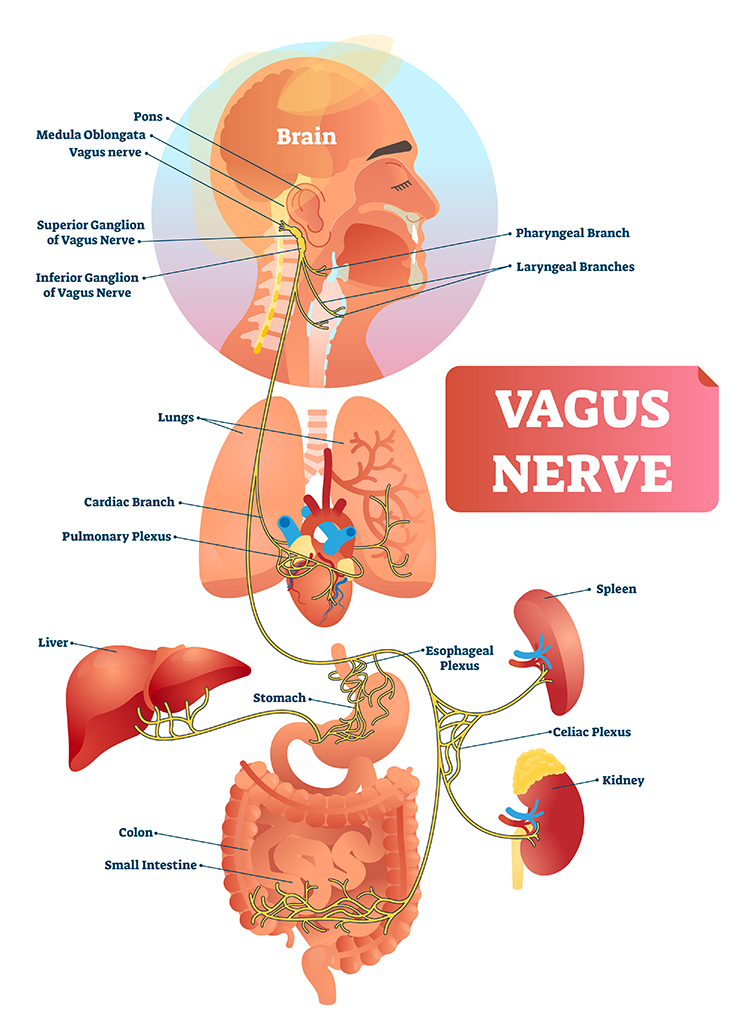

The vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) carries approximately 75% of all parasympathetic fibers in the human body, making it the primary conduit for parasympathetic influence on internal organs. The remaining parasympathetic fibers travel through cranial nerves III (oculomotor), VII (facial), and IX (glossopharyngeal), as well as the pelvic splanchnic nerves, which originate from the sacral segments (S2-S4) of the spinal cord.

Because parasympathetic neurons originate in the brainstem and sacral spinal cord (with a gap in the thoracolumbar region where sympathetic neurons are located), the parasympathetic division is described as craniosacral.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Parasympathetic Nervous System Organization

Parasympathetic Ganglia Are Located Near Target Organs

A key anatomical difference distinguishes parasympathetic from sympathetic organization. Unlike the sympathetic division's centralized ganglia running alongside the spinal cord, parasympathetic ganglia are located near or within their target organs. This arrangement produces a characteristic pattern: preganglionic axons are relatively long (traveling from the brainstem to the target region), while postganglionic axons are relatively short (spanning only the final distance to the target cells).

This anatomical arrangement enables more selective parasympathetic control. While sympathetic mass activation can simultaneously affect many organs, parasympathetic effects can be more precisely targeted. For example, parasympathetic signals can adjust cardiac function without necessarily affecting digestion, or vice versa.

Preganglionic parasympathetic neurons travel with the oculomotor, facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus cranial nerves. Preganglionic neurons exiting the vagus nerve at the medulla synapse with terminal ganglia within the heart, lungs, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, liver, and intestines.

Both parasympathetic preganglionic and postganglionic axons release acetylcholine, unlike the sympathetic system's switch from acetylcholine to norepinephrine (Fox & Rompolski, 2022). This consistent cholinergic transmission helps explain why anticholinergic medications can produce widespread parasympathetic blockade.

The Vagus Nerve Dampens Inflammation

Beyond its traditional autonomic functions, the vagus nerve plays a crucial role in regulating inflammation, a finding with significant implications for treating chronic inflammatory conditions. The vagus nerve's sensory branch detects inflammation and infection via pro-inflammatory signaling molecules including tissue necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 (IL-1). This sensory function allows the nervous system to monitor immune activity throughout the body.

The vagus nerve, through its sympathetic components, participates in anti-inflammatory pathways. It can stimulate the splenic sympathetic nerve, which helps inhibit the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha, thereby contributing to the body's anti-inflammatory responses (Bonaz, Sinniger, & Pellissier, 2016, 2017).

The mechanism involves a sophisticated relay: the motor branch of the vagus signals descending neurons to release norepinephrine, which prompts spleen immune cells to release acetylcholine to macrophages, ultimately dampening inflammation (Schwartz, 2015). Resonance frequency breathing may influence this vagal cholinergic cytokine control system (Gevirtz, 2013; Tracey, 2007), suggesting a potential mechanism through which HRV biofeedback could benefit inflammatory conditions.

Chronic inflammation is implicated in numerous disorders that biofeedback practitioners encounter, including fibromyalgia, depression, and cardiovascular disease. A fibromyalgia patient presenting with widespread pain, fatigue, and cognitive difficulties may have elevated inflammatory markers. The vagus nerve's anti-inflammatory function suggests that HRV biofeedback might benefit such patients through multiple mechanisms: direct effects on pain modulation, improved sleep, and reduced systemic inflammation.

The Vagus Nerve Contains Sympathetic Fibers

A surprising anatomical finding challenges the simple dichotomy between vagal (parasympathetic) and sympathetic pathways: the vagus nerve itself contains sympathetic fibers involved in modulating autonomic functions and anti-inflammatory responses.

Research has consistently identified sympathetic fibers within the human vagus nerve, demonstrated by the presence of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-positive fibers. Tyrosine hydroxylase is the enzyme that catalyzes the first step in norepinephrine synthesis, making it a reliable marker for sympathetic neurons. These fibers are distributed throughout the cervical and thoracic regions of the vagus nerve.

Human vagus nerves contain 3.97% to 5.47% sympathetic nerve fibers (Kawagishi et al., 2008; Ruigrok et al., 2023; Seki et al., 2014). The distribution and quantity of these sympathetic fibers varies significantly between individuals and even between the left and right vagus nerves of the same individual (Ruigrok et al., 2023; Wallace et al., 2022).

The presence of sympathetic fibers within the vagus nerve may contribute to the physiological effects observed with vagal nerve stimulation (VNS), including modulation of autonomic balance and potential therapeutic benefits in conditions like depression and chronic heart failure (Ruigrok et al., 2023; Seki et al., 2014). This finding suggests that the vagus nerve may be better understood as an autonomic highway carrying both parasympathetic and sympathetic traffic, rather than a purely parasympathetic pathway.

The parasympathetic division is craniosacral and conserves energy through rest-and-digest functions. Unlike the sympathetic division, parasympathetic ganglia are located near target organs, allowing more selective control. The vagus nerve carries about 75% of parasympathetic fibers and plays a role in dampening inflammation through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. The finding that the vagus nerve also contains 4% to 5% sympathetic fibers challenges simple dichotomies and has implications for understanding vagal nerve stimulation effects.

Comprehension Questions: Parasympathetic Division

- Why is the parasympathetic division described as craniosacral, and how does this differ from sympathetic organization?

- How does the location of parasympathetic ganglia differ from sympathetic ganglia, and what functional advantage does this arrangement provide?

- What role does the vagus nerve play in the anti-inflammatory response, and why might this matter for biofeedback practice?

- What percentage of sympathetic nerve fibers are found in human vagus nerves, and what are the implications of this finding?

The Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Branches Work Together

Berntson, Cacioppo, and Quigley (1993) challenged the conventional view of autonomic function as a simple continuum ranging from SNS to PNS dominance. Their influential "autonomic space" model demonstrated that the two branches do not only act antagonistically (in opposition). They also exert complementary, cooperative, and independent actions. This more nuanced understanding has important implications for clinical assessment and intervention.

Antagonistic Actions: The Branches Compete for Control

The SNS and PNS branches can compete for control of target organs such as the heart. The parasympathetic vagus can slow the heart by 20 to 30 beats per minute or, in extreme cases, briefly stop it entirely (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). This powerful braking capacity gives the vagus substantial influence over cardiac function.

Since these divisions generally produce contradictory effects (like speeding and slowing the heart), their net effect on an organ depends on their current balance of activity. This competitive relationship, called accentuated antagonism, means that each branch's influence depends partly on the other branch's activity level (Olshansky et al., 2008). High sympathetic activity makes the heart more responsive to vagal slowing, while high vagal tone makes the heart more responsive to sympathetic acceleration.

The following table, adapted from Fox and Rompolski (2022), summarizes adrenergic and cholinergic effects on various organs. Adrenergic receptors are classified as alpha or beta subtypes, while cholinergic receptors in target organs are muscarinic (M) type.

Complementary Actions: Both Branches Produce Similar Changes

SNS and PNS actions are complementary when they produce similar (though not identical) changes in the target organ. Saliva production illustrates this pattern: PNS activation produces copious watery saliva optimized for digestion, while SNS activation constricts salivary gland blood vessels, producing thick, viscous saliva. Both actions increase saliva production, though the resulting secretions differ in composition and function.

Cooperative Actions: Different Effects Result in a Single Action

SNS and PNS actions are cooperative when their different effects combine to produce a single complex behavior. Sexual function provides a clear example: PNS activation produces erection and vaginal secretions (the arousal phase), while SNS activation produces ejaculation and orgasm (the climax phase). Neither branch alone could accomplish the complete sexual response; they must work sequentially in coordination.

Some Organs Receive Exclusive Sympathetic Control

As noted earlier, several organs receive exclusively sympathetic innervation with no parasympathetic counterpart. These include the adrenal medulla, arrector pili muscles, sweat glands, and most blood vessels. Regulation of these structures depends entirely on modulating the firing rate of SNS postganglionic fibers, either increasing or decreasing their activity from baseline levels.

The Relationship Between the SNS and PNS is Dynamic

In a healthy heart, the relationship between sympathetic and parasympathetic influences is dynamic, constantly adjusting to meet changing demands. The synergistic relationship between these branches is complex, sometimes reciprocal (one up, one down), additive (both increasing together), or subtractive (one branch's increase offset by the other's decrease) (Gevirtz, Lehrer, & Schwartz, 2016).

At rest, PNS control predominates. This vagal dominance produces an average resting heart rate of about 75 beats per minute (bpm), significantly slower than the sinoatrial (SA) node's intrinsic firing rate, which decreases with age from an average of 107 bpm at 20 years to 90 bpm at 50 years (Opthof, 2000). The difference between intrinsic rate and actual resting rate reflects the degree of vagal braking.

Parasympathetic nerves exert their effects much more rapidly (within 1 second) than sympathetic nerves (more than 5 seconds) (Eckberg & Eckberg, 1982; Nunan et al., 2010; Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). This speed difference means that rapid heart rate fluctuations (like those seen in respiratory sinus arrhythmia) primarily reflect parasympathetic modulation.

The relationship between branches can also produce unexpected effects. While the SNS can suppress PNS activity, it can paradoxically increase PNS reactivity under certain conditions (Gellhorn, 1957). Parasympathetic rebound may occur following periods of high stress, potentially resulting in increased nighttime gastric activity (Nada et al., 2001) and worsening asthma symptoms during sleep (Ballard, 1999). These rebound phenomena help explain why some patients experience symptom flares during recovery periods rather than during the stressor itself.

A COPD patient may experience nocturnal symptom exacerbation due to parasympathetic rebound following daytime stress. Understanding this mechanism helps clinicians appreciate why stress management and HRV biofeedback training might benefit respiratory conditions. Similarly, asthma patients often report worse symptoms at night, partly due to circadian increases in parasympathetic tone that cause bronchoconstriction.

The relationship between the PNS and SNS branches is complex, involving both linear and nonlinear dynamics, and should not be described as a "zero sum" system (Ginsberg, 2017). Increased PNS activity may be associated with decreased, increased, or unchanged SNS activity depending on the circumstances.

Immediately following aerobic exercise, heart rate recovery involves PNS reactivation while SNS activity remains elevated (Billman, 2017). This simultaneous activation of both branches explains why heart rate can drop rapidly after exercise even while blood pressure remains elevated. Similarly, teaching clients to breathe slowly during periods of high SNS activity can engage both branches simultaneously and increase respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) (Ginsberg, 2017). This is analogous to a Formula 1 driver speeding through a turn while gently applying the left foot to the brake, a maneuver called "left-foot braking" (Ginsberg, 2017). The skilled driver can simultaneously accelerate and brake; similarly, skilled autonomic regulation involves managing both branches together.

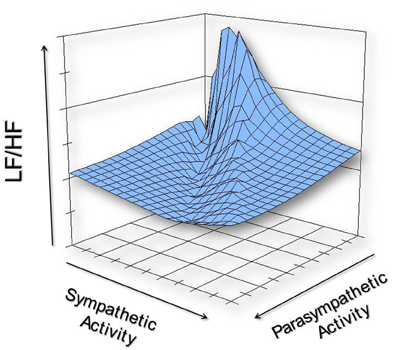

The complex relationship between SNS and PNS nerve activity has important implications for HRV interpretation. Specifically, the ratio between LF and HF power (the LF/HF ratio) may not accurately index autonomic balance as once believed (Billman, 2013). The following graphic illustrates how varying levels of SNS and PNS nerve activity can co-determine the LF/HF ratio, producing similar ratios from very different underlying autonomic states.

We must reject the simplistic view that increased sympathetic activity is inherently unhealthy. This view is clearly false when you swim laps in a pool or are startled by an unexpected sound. Adaptive SNS activation in response to increased physical workload or sudden threats is desirable and necessary for normal function.

Paradoxically, a depressed SNS response could signal physical depletion and compromised coping capacity. In fact, 24-hour HRV recordings of patients diagnosed with various medical and psychological disorders sometimes show low SNS activity alongside normal PNS activity, not the expected sympathetic dominance.

Reduced very-low-frequency (VLF) power (the HRV frequency band below 0.04 Hz) is strongly associated with future health crises including sudden cardiac death (Arai et al., 2009; McCraty, 2013). The clinically relevant question is not whether sympathetic activity is present, but whether the degree and duration of SNS activation are appropriate to the current challenge and whether recovery is rapid once the challenge passes.

The sympathetic and parasympathetic branches interact through antagonistic, complementary, cooperative, and independent actions, not simple opposition. PNS control predominates at rest and exerts effects more rapidly than the SNS. The relationship between branches is dynamic and complex, not a simple zero-sum system. The LF/HF ratio may not accurately index autonomic balance because both branches can be active simultaneously. Healthy function depends on appropriate activation of both branches, not suppression of sympathetic activity.

Comprehension Questions: SNS-PNS Relationship

- What is accentuated antagonism, and how does it affect heart rate regulation?

- Give an example of complementary SNS and PNS actions, and explain why the resulting effects differ despite both producing similar changes.

- Why might the LF/HF ratio not accurately index autonomic balance?

- What does the "left-foot braking" analogy illustrate about autonomic function during slow-paced breathing?

Porges' Polyvagal Theory Reveals Vagal Complexity

The vagus nerve (the 10th cranial nerve) inhibits the heart and increases bronchial tone in the lungs. However, as we have seen, reducing the vagus to simple parasympathetic effects misses its remarkable complexity. Stephen Porges' polyvagal theory provides a framework for understanding this complexity and its clinical implications.

The vagus contains specialized subsystems that control competing adaptive responses, not a single unified parasympathetic signal.

According to Porges' (2011) Polyvagal Theory, the autonomic nervous system must be understood as an integrated "system" in which the vagal nerve contains specialized subsystems regulating competing adaptive responses. The theory derives from an evolutionary perspective: different vagal components emerged at different points in vertebrate evolution to serve different adaptive functions.

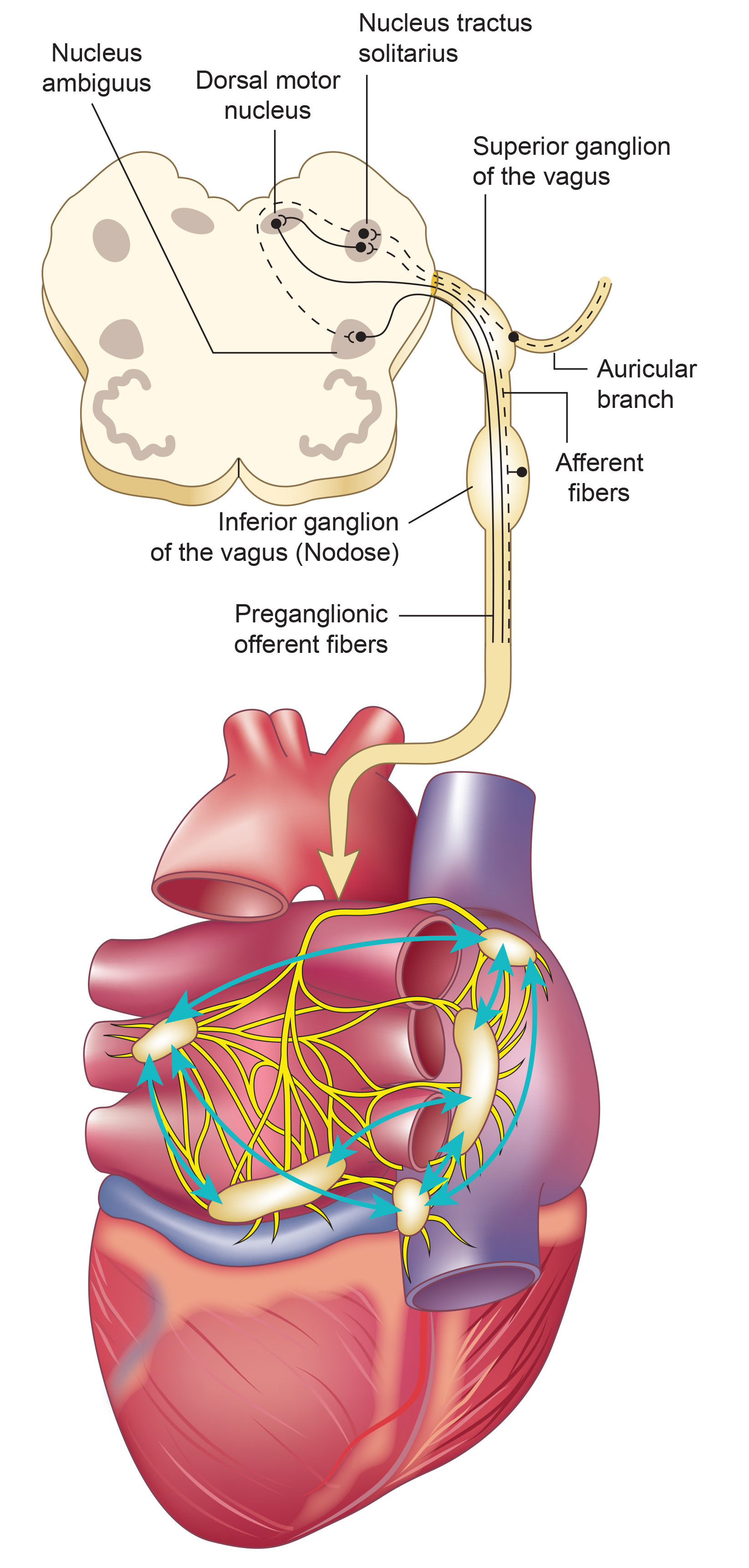

The name "polyvagal" refers to two distinct vagal systems: the unmyelinated vagus (originating in the dorsal motor nucleus, an evolutionarily older structure) and the myelinated vagus (originating in the nucleus ambiguus, a newer structure unique to mammals). Myelinated fibers conduct signals faster than unmyelinated fibers, enabling the rapid, fine-tuned cardiac control that supports mammalian social behavior.

Porges' theory proposes competing roles for the unmyelinated fibers (originating in the dorsal motor complex) and the newer myelinated fibers (originating in the nucleus ambiguus). Although aspects of polyvagal theory remain controversial among physiologists (Grossman & Taylor, 2007), the framework highlights diverse parasympathetic adaptive functions that have proven clinically useful, particularly in understanding trauma responses.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Polyvagal Perspective

The Myelinated Vagus Supports Social Engagement

The myelinated vagus (the newer ventral vagal complex) rapidly adjusts cardiac output to match changing metabolic demands. When we perceive our environment as safe, the myelinated vagus increases vagal tone and supports social engagement and self-regulation. This connection between cardiac regulation and social behavior is one of polyvagal theory's most clinically relevant insights.

Porges hypothesizes that face-to-face social interaction with trusted people can restore autonomic balance. This hypothesis has implications for treatment settings: creating conditions of felt safety may be necessary before biofeedback training can effectively engage the social engagement system.

The cranial nerves controlling middle ear muscles, facial expression, and vocalization contribute to social engagement alongside the myelinated vagus. You may have noticed that when you feel safe, you are more likely to smile, speak with vocal inflection, and listen attentively. When you feel threatened, your face may become expressionless, your voice flat, and your hearing less attuned to social cues. These observable changes reflect shifts in vagal state.

A clinician working with anxiety or phobia patients may notice that as clients become more comfortable, their voices develop more prosody (melodic variation), their faces become more expressive, and they make more eye contact. These changes reflect increasing ventral vagal engagement. Conversely, a client who "freezes up" during discussion of fear-inducing material may show flattened facial affect and monotone speech, signaling a shift away from social engagement. Recognizing these signs helps clinicians pace exposure interventions appropriately.

The Sympathetic Branch Mobilizes for Action

The SNS mobilizes for fight, flight, or active avoidance in response to perceived threats. When our nervous system perceives danger (through a process Porges calls "neuroception," the unconscious detection of safety or threat), we activate the sympathetic branch along with the endocrine system's SAM (sympathetic-adrenal-medullary) pathway and HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis. This activation inhibits the unmyelinated vagus, preparing us for action.

The Unmyelinated Vagus Triggers Freeze Responses

Porges hypothesizes that when perceived life threat is so extreme that fight, flight, or active avoidance seems impossible, the unmyelinated vagus activates what he calls the freeze response. This evolutionarily ancient response involves immobilization, feigning death (like an opossum "playing dead"), passive avoidance, and physiological shutdown. Check out the YouTube video The Polyvagal Theory and PTSD with Stephen Porges, PhD.

The freeze response has particular relevance for understanding trauma. A rape survivor who "froze" during an assault may feel confused or ashamed about not fighting back. Understanding the freeze response as an automatic, protective physiological response (not a choice) can be profoundly therapeutic. Similarly, veterans who experienced immobilization during combat may struggle with the perception that they should have acted differently. Polyvagal theory reframes these responses as adaptive survival mechanisms, not character failures. VA clinicians working with PTSD patients find this framework particularly valuable for psychoeducation.

Polyvagal Theory Summary

When our nervous system perceives safety, we activate the myelinated vagus to conserve and rebuild energy stores (rest and digest), socially bond with others (tend and befriend), and engage in executive functions like self-regulation and planning.

When our nervous system perceives danger, we activate the sympathetic branch and the endocrine system's SAM pathway and HPA axis, inhibiting the unmyelinated vagus to prepare for fight, flight, or active avoidance.

When our nervous system perceives that our life is threatened and that fight, flight, or active avoidance will not succeed (like a mouse in the jaws of a cat), we activate the unmyelinated vagus. This results in passive avoidance through dissociation, fainting, feigning death, immobilization, and shutdown.

Polyvagal theory proposes that the vagus nerve contains two specialized systems: the myelinated vagus (ventral vagal complex) that supports social engagement and self-regulation, and the unmyelinated vagus (dorsal vagal complex) that can trigger freeze responses under extreme threat. Our physiological response depends on whether we perceive safety, danger, or life threat. While aspects of the theory remain debated, its framework has proven clinically useful, particularly for understanding and treating trauma-related conditions.

Comprehension Questions: Polyvagal Theory

- What are the two vagal systems described in polyvagal theory, and where do they originate?

- What behaviors does the myelinated vagus support when we feel safe, and what observable signs might indicate its engagement?

- Under what circumstances does the unmyelinated vagus activate the freeze response?

- Why is polyvagal theory considered controversial, and why has it nonetheless gained clinical acceptance?

The Enteric Division: Your Second Brain

The enteric division constitutes the largest part of the autonomic nervous system (Rao & Gershon, 2016). The enteric nervous system (ENS) comprises a vast network of 200 to 600 million neurons along with four times as many glial cells (support cells) distributed throughout the gastrointestinal tract (Boesmans et al., 2013; Popowycz et al., 2022). This neuron count rivals the spinal cord and explains why the ENS is often called the "second brain."

The ENS contains nearly all of the same neurotransmitters found in the CNS. This neurochemical similarity underscores the ENS's complexity and its capacity to function as an independent integrative center capable of coordinating digestive function without continuous input from the brain.

The ENS controls peristalsis (the wave-like muscle contractions that move food through the digestive tract) and enzyme secretion in the GI tract, maintaining fluid and nutrient balance (Breedlove & Watson, 2023). While the ENS locally regulates intestinal functions, sympathetic and parasympathetic efferents can override its activity during intense emotions like anger and fear (Fox & Rompolski, 2022). This override capacity explains why emotional distress can produce GI symptoms ranging from "butterflies" to diarrhea.

During physical activity and stress, SNS firing inhibits intestinal motility, diverting blood flow away from digestion and toward skeletal muscles. During rest, PNS firing promotes intestinal motility by exciting enteric preganglionic neurons (Khazan, 2013). This reciprocal relationship helps explain why stress management can improve functional GI disorders.

Patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) often report that symptoms worsen during periods of stress. The autonomic override of enteric function explains this connection: stress-induced sympathetic activation and vagal withdrawal alter gut motility and sensitivity. HRV biofeedback training can help these patients restore parasympathetic tone, potentially improving both autonomic balance and GI symptoms. Similar mechanisms apply to functional abdominal pain, where the gut-brain connection plays a central role.

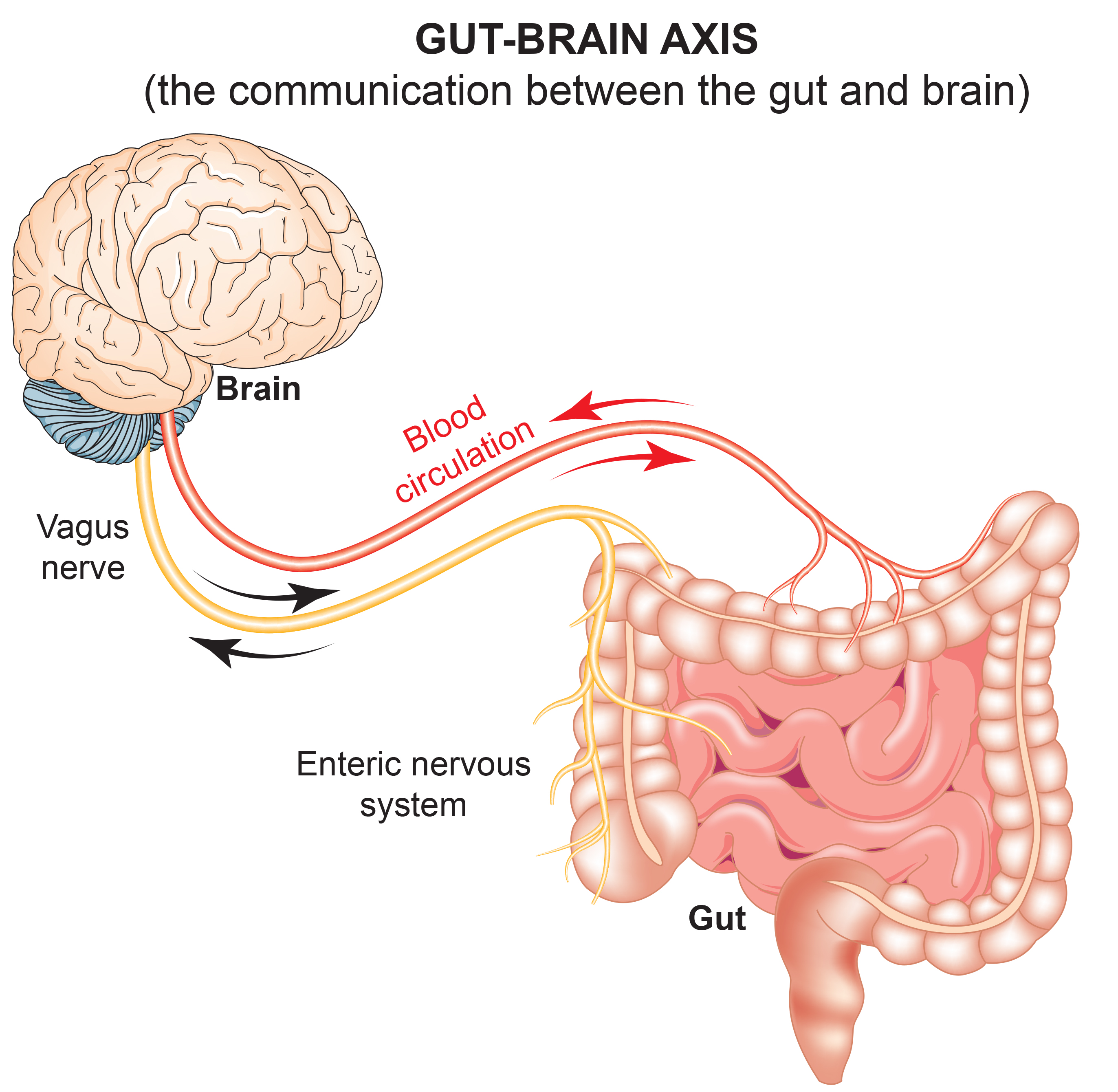

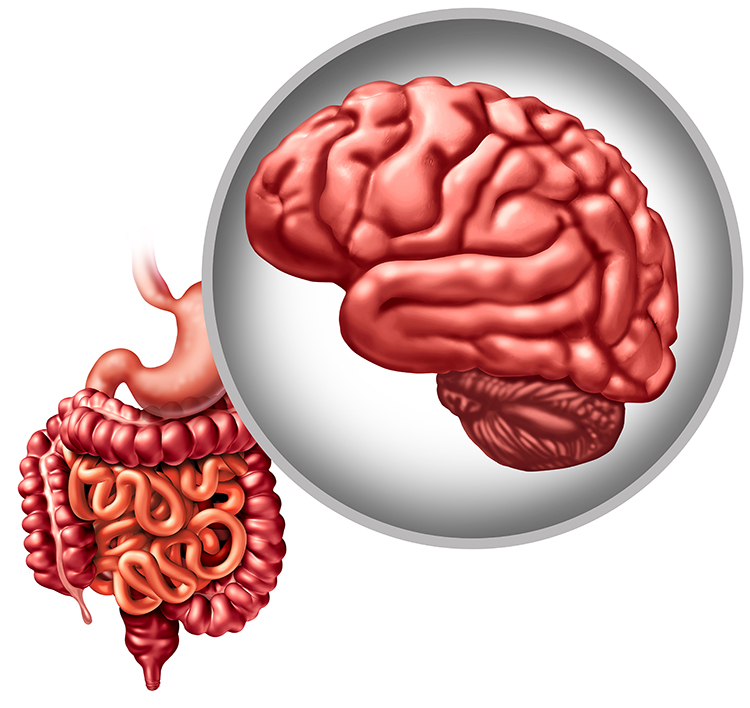

The ENS and central nervous system communicate bidirectionally via the vagus nerve (Carabotti et al., 2015). The gut-brain axis integrates neuronal, endocrine, and immune mechanisms. Enteric glial cells modulate neuronal activity, inflammation, and gut barrier function (Gulbransen & Sharkey, 2012). This bidirectional communication means that brain states can influence gut function and gut states can influence brain function, including mood and cognition.

Emerging research suggests that the gut microbiome (the trillions of bacteria residing in the digestive tract) may contribute to the onset and progression of serious mental illnesses (SMIs). Gut microbiota imbalances may contribute to systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation affecting brain function (Nguyen et al., 2021). The ENS may play integral roles in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and autism spectrum disorder (Fung et al., 2017).

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Enteric Nervous System

The enteric division contains approximately 100 million neurons (comparable to the spinal cord; Boron & Boulpaep, 2017), which release a comparable range of neurotransmitters as the CNS (Gershon, 1999). The ENS contains interneurons, sensory neurons, autonomic motor neurons, and neuroglial cells, mirroring the organizational complexity of the CNS in miniature.

A subset of intestinal sensory neurons travels in the vagus nerve to influence ANS activity (Fox & Rompolski, 2022). This ascending pathway allows gut sensations to influence autonomic state and emotional experience, potentially explaining the visceral quality of certain emotions.

A striking finding underscores the ENS's importance for brain chemistry: the gut contains more than 90% of the body's serotonin (Khazan, 2013) and about 50% of its dopamine. These neurotransmitters, typically associated with mood regulation and reward, are predominantly produced and utilized in the gut. Check out the Khan Academy YouTube video Control of the GI Tract.

The gut-brain connection has implications for understanding depression. With more than 90% of the body's serotonin located in the gut, intestinal health may influence mood through multiple pathways. Clinicians working with depressed patients might consider how gut health, inflammation, and autonomic balance interact. HRV biofeedback may benefit depression through its effects on vagal tone, inflammation, and the gut-brain axis.

Enteric neurons are concentrated in two networks of ganglia: the myenteric (Auerbach's) plexus between the muscle layers and the submucosal (Meissner's) plexus. While the ENS locally regulates intestinal functions, sympathetic and parasympathetic efferents can override its activity during intense emotions like anger and fear (Fox & Rompolski, 2022).

During physical activity and stress, sympathetic firing inhibits intestinal motility. During rest, parasympathetic firing promotes it by exciting enteric preganglionic neurons (Khazan, 2013).

The enteric nervous system contains 200 to 600 million neurons and operates as an independent integrative center, earning it the nickname "second brain." The ENS controls digestion and communicates bidirectionally with the CNS via the gut-brain axis. The gut contains more than 90% of the body's serotonin and about 50% of its dopamine. Gut microbiome imbalances may contribute to serious mental illnesses through inflammatory mechanisms. These findings have implications for treating functional GI disorders and potentially for understanding mood disorders.

Comprehension Questions: Enteric Division

- How many neurons does the enteric nervous system contain, and why is it called the "second brain"?

- What is the gut-brain axis, and how do the ENS and CNS communicate?

- What percentage of the body's serotonin is found in the gut, and what are the implications of this finding?

- How do the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions influence intestinal motility, and what clinical relevance does this have?

Common Misconceptions About the Autonomic Nervous System

A popular author wrote that since excessive sympathetic nervous system activity causes many diseases, people should practice exercises that strengthen the protective parasympathetic nervous system. What mistake did this author make?

The idea of a "bad" sympathetic nervous system and "good" parasympathetic nervous system represents one of the most common misconceptions about autonomic function. As we have seen throughout this chapter, the body depends on both systems to function normally. Both systems maintain continuous baseline activity, with their relative activation depending on immediate demands and our response to challenges.

Health and optimal performance depend on autonomic flexibility: the capacity of each branch to activate to the appropriate degree and for the required duration to meet current demands, then recover quickly when the demand passes. There are no inherently "good" and "bad" systems. The goal of HRV biofeedback is not to maximize parasympathetic activity or minimize sympathetic activity, but to restore the dynamic balance that allows flexible, adaptive responding.

The popular author should remember that parasympathetic overactivity contributes to several disorders. Asthma involves excessive bronchoconstriction (a parasympathetic effect). Hypotension can result from excessive vagal influence on cardiac output. Irritable bowel syndrome often involves dysregulated parasympathetic effects on gut motility. In preeclampsia, autonomic imbalance includes altered parasympathetic function. In these conditions, the "restorative" parasympathetic system causes problems, just as the "activating" sympathetic system can cause problems when chronically elevated. Balance, not one-sided dominance, is the therapeutic goal.

Cutting Edge Topics

Vagus Nerve Stimulation Therapy

The vagus nerve's role in dampening inflammation has sparked substantial interest in vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) as a therapeutic approach. Researchers are actively exploring VNS for conditions ranging from treatment-resistant depression and epilepsy to rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.

The vagus nerve's anti-inflammatory pathway, called the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, offers a potential drug-free approach to managing chronic inflammatory conditions. This mechanism may also partially explain the benefits of HRV biofeedback for conditions with inflammatory components. Read the Science News article Viva vagus: Wandering nerve could lead to range of therapies.

Sympathetic Fibers in the Vagus: Implications for VNS

The recent discovery that the human vagus nerve contains 4% to 5% sympathetic nerve fibers has significant implications for vagus nerve stimulation therapy. This finding challenges the assumption that VNS produces purely parasympathetic effects.

The presence of sympathetic fibers may explain some of the unexpected effects observed during VNS treatment and could help researchers optimize stimulation protocols for different therapeutic applications. Understanding the vagus as a mixed autonomic pathway rather than a purely parasympathetic one may lead to more refined treatment approaches.

The Gut-Brain Connection and Mental Health

Emerging research on the gut-brain axis suggests that the enteric nervous system plays a more significant role in mental health than previously understood. Gut microbiome imbalances have been linked to anxiety, depression, and even neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

This research has generated interest in "psychobiotics," probiotics that may influence brain function through the gut-brain axis. While this field remains in early stages, it suggests that interventions targeting gut health (including stress reduction through HRV biofeedback) may have unexpected mental health benefits through vagally-mediated gut-brain communication.

Optimal Performance Applications

Beyond clinical applications, HRV biofeedback has gained traction in optimal performance training. Athletes, musicians, executives, and military personnel use HRV training to enhance performance under pressure. The autonomic flexibility developed through training helps individuals maintain composure and cognitive function during high-stakes situations.

Understanding the autonomic nervous system's role in performance helps practitioners design training protocols that enhance both recovery capacity and stress resilience. The goal is not simply relaxation but rather the ability to rapidly shift autonomic states to match situational demands.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this module, consider how you might better explain the relationship between the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system to your clients. Many clients arrive with the misconception that their sympathetic system is the enemy and their parasympathetic system needs to be "strengthened." How would you correct this misconception while still motivating them to engage in training?

Consider also how negative emotion interferes with HRV biofeedback training. Excessive effort, anxiety about performance, and frustration can all trigger sympathetic activation and vagal withdrawal, producing the opposite of the intended training effect. Why might emotional self-regulation be an important training component for some individuals, and how might you integrate this understanding into your clinical practice?

Glossary

accentuated antagonism: the parasympathetic nervous system's ability to directly oppose sympathetic action, such as slowing the heart by 20 or 30 beats, with each branch's influence depending partly on the other branch's activity level.

acetylcholine (ACh): the neurotransmitter released by all preganglionic neurons and parasympathetic postganglionic neurons.

adrenal medulla: the inner region of the adrenal gland that produces the hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine.

autonomic nervous system: the subdivision of the peripheral nervous system that includes enteric, parasympathetic, and sympathetic divisions.

beta-adrenergic: relating to receptors stimulated by epinephrine and norepinephrine that mediate heart rate acceleration, vasodilation, and metabolic effects.

central nervous system: the division of the nervous system that includes the brain, spinal cord, and retina.

enteric division: the largest autonomic nervous system branch containing 200 to 600 million neurons that regulate gastrointestinal function.

freeze response: the unmyelinated vagus response to life-threatening situations involving immobilization, feigning death, passive avoidance, and shutdown.

ganglia: a collection of neuronal cell bodies outside of the CNS.

gut-brain axis: the bidirectional communication system between the enteric nervous system and central nervous system integrating neuronal, endocrine, and immune mechanisms.

heart rate variability (HRV): the beat-to-beat changes in heart rate, including changes in the time intervals between consecutive heartbeats.

homeostat: a device that maintains homeostasis. For example, the hypothalamus.

hypothalamus: the forebrain structure located below the thalamus that dynamically maintains homeostasis through its control of the autonomic nervous system, endocrine system, survival behaviors, and interconnections with the immune system.

mass activation: the simultaneous stimulation of adjacent ganglia (cell bodies) in the sympathetic chain allows the sympathetic nervous system to produce many coordinated changes simultaneously. For example, increased heart rate, respiration rate, and sweat gland activity.

medulla: the brainstem structure that regulates blood pressure, defecation, heart rate, respiration, and vomiting. The medulla influences the autonomic nervous system and distributes signals between the brain and spinal cord.

myelinated vagus: the phylogenetically newer ventral vagal complex that rapidly adjusts cardiac output and promotes social engagement.

norepinephrine: the neurotransmitter released by most sympathetic postganglionic neurons.

parasympathetic division: the autonomic nervous system subdivision that regulates activities that increase the body's energy reserves, including salivation, gastric (stomach) and intestinal motility, gastric juice secretion, and increased blood flow to the gastrointestinal system.

parasympathetic withdrawal: daily stressors can inhibit the myelinated vagus suppressing parasympathetic activity.

peripheral nervous system: nervous system subdivision that includes autonomic and somatic branches.

Polyvagal Theory: theory that the unmyelinated vagus (dorsal vagus complex) and newer myelinated vagus (ventral vagal complex) mediate competing adaptive responses.

postganglionic axons: axons that originate in the autonomic ganglia and project to target organs like the heart, lungs, and digestive system.

preganglionic axons: axons that originate in the CNS, the brainstem, or the spinal cord and travel to nerve cell body clusters in the PNS.

somatic nervous system: peripheral nervous system subdivision that receives external sensory and somatosensory information and controls skeletal muscle contraction.

serious mental illnesses (SMIs): mental health conditions that may be influenced by gut microbiome imbalances through systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation.

sympathetic division: autonomic nervous system branch that regulates activities that expend stored energy, such as when we are excited.

sympathetic preganglionic neurons: the neurons that originate in the CNS, leave the spinal cord via the ventral root, and mainly synapse with sympathetic chain ganglia.

unmyelinated vagus: the phylogenetically older dorsal vagus complex that responds to threats through immobilization, feigning death, passive avoidance, and shutdown.

vagal withdrawal: the inhibition of the myelinated vagus, often by daily stressors.

vagus nerve: the tenth cranial nerve, which supplies parasympathetic nervous system innervation for the heart.

very low frequency (VLF): the ECG frequency range of 0.003 to 0.04 Hz that may represent temperature regulation, plasma renin fluctuations, endothelial, and physical activity influences, and possible intrinsic cardiac nervous system, PNS, and SNS contributions.

References

Arai, Y. C., et al. (2009). Increased heart rate variability correlation between mother and child immediately pre-operation. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 53(5), 607-610. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.01912.x

Ballard, R. D. (1999). Sleep, respiratory physiology, and nocturnal asthma. Chronobiology International, 16(5), 565-580. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420529908998729

Berntson, G. G., Cacioppo, J. T., & Quigley, K. S. (1993). Cardiac psychophysiology and autonomic space in humans: Empirical perspectives and conceptual implications. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 296-322. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.296

Billman, G. E. (2013). The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Frontiers in Physiology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2013.00026

Billman, G. E. (2017). Personal communication to J. P. Ginsberg regarding the LF/HF ratio.

Boesmans, W., Martens, M. A., Weltens, N., Hao, M. M., Tack, J., Cirillo, C., & Vanden Berghe, P. (2013). Imaging neuron-glia interactions in the enteric nervous system. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 7, 183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2013.00183

Bonaz, B., Sinniger, V., & Pellissier, S. (2016). Anti-inflammatory properties of the vagus nerve: Potential therapeutic implications of vagus nerve stimulation. The Journal of Physiology, 594. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP271539

Bonaz, B., Sinniger, V., & Pellissier, S. (2017). The vagus nerve in the neuro-immune axis: Implications in the pathology of the gastrointestinal tract. Frontiers in Immunology, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01452

Boron, W. F., & Boulpaep, E. L. (2017). Medical physiology (3rd ed.). Saunders.

Breedlove, S. M., & Watson, N. V. (2023). Behavioral neuroscience (10th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc.

Brindle, R. C., Ginty, A. T., Phillips, A. C., & Carroll, D. (2014). A tale of two mechanisms: A meta-analytic approach toward understanding the autonomic basis of cardiovascular reactivity to acute psychological stress. Psychophysiology, 51(10), 964-976. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12248

Carabotti, M., Scirocco, A., Maselli, M. A., & Severi, C. (2015). The gut-brain axis: Interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Annals of Gastroenterology, 28(2), 203-209.

Eckberg, D. L., & Eckberg, M. J. (1982). Human sinus node responses to repetitive, ramped carotid baroreceptor stimuli. American Journal of Physiology, 242(Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 11), H638-H644. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.4.h638

Fox, S. I., & Rompolski, K. (2022). Human physiology (16th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Fung, C., Vanden Berghe, P., Bhatt, A. P., & Bhatt, A. S. (2017). Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nature Neuroscience, 20(2), 145-155. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4476

Gellhorn, E. (1957). Autonomic imbalance and the hypothalamus: Implications for physiology, medicine, psychology, and neuropsychiatry. University of Minnesota Press.

Gershon, M. D. (1999). The enteric nervous system: A second brain. Hospital Practice, 34(7), 31-32, 35-38, 41-42 passim. https://doi.org/10.3810/hp.1999.07.153

Gevirtz, R. (2013). The nerve of that disease: The vagus nerve and cardiac rehabilitation. Biofeedback, 41(1), 32-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.1.01

Gevirtz, R. N., Lehrer, P. M., & Schwartz, M. S. (2016). Cardiorespiratory biofeedback. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.). Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Ginsberg, J. P. (2017). Personal communication regarding autonomic balance.

Grossman, P., & Taylor, E. W. (2007). Toward understanding respiratory sinus arrhythmia: Relations to cardiac vagal tone, evolution and biobehavioral functions. Biological Psychology, 74, 263-285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.11.014

Gulbransen, B. D., & Sharkey, K. A. (2012). Novel functional roles for enteric glia in the gastrointestinal tract. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 9(11), 625-632. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2012.138

Karemaker, J. M. (2020). Interpretation of heart rate variability: The art of looking through a keyhole. Frontiers in Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.609570

Kawagishi, K., Fukushima, N., Yokouchi, K., Sumitomo, N., Kakegawa, A., & Moriizumi, T. (2008). Tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive fibers in the human vagus nerve. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 15, 1023-1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2007.08.032

Khazan, I. Z. (2013). The clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Lehrer, P. M., & Gevirtz, R. (2021). BCIA HRV Biofeedback didactic workshop. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

McCraty, R. (2013). Personal communication concerning autonomic balance.

Nada, T., Nomura, M., Iga, A., Kawaguchi, R., Ochi, Y., Saito, K., Nakaya, Y., & Ito, S. (2001). Autonomic nervous function in patients with peptic ulcer studied by spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Journal of Medicine, 32(5-6), 333-347. PMID: 11958279

Nguyen, T. T., Kosciolek, T., Maldonado, Y., Daly, R. E., Martin, A. S., McDonald, D., Knight, R., & Jeste, D. V. (2021). Gut microbiome in serious mental illnesses: A systematic review and critical evaluation. Schizophrenia Research, 234, 59-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2019.08.026

Nunan, D., Sandercock, G. R. H., & Brodie, D. A. (2010). A quantitative systematic review of normal values for short-term heart rate variability in healthy adults. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 33(11), 1407-1417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2010.02841.x

Opthof, T. (2000). The normal range and determinants of the intrinsic heart rate in man. Cardiovascular Research, 45(1), 177-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00322-3

Olshansky, B., Sabbah, H. N., Hauptman, P. J., & Colucci, W. S. (2008). Parasympathetic nervous system and heart failure: Pathophysiology and potential implications for therapy. Circulation, 118, 863-871. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.107.760405

Popowycz, A. G., Gibbons, S. J., Xu, H., Sha, L., Bhave, S., Bhave, A. S., Miller, S. M., Farrugia, G., & Bhave, A. S. (2022). Cell-type specific transcriptomic diversity of the enteric nervous system. Cell Reports, 41(5), 111595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111595

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Rao, M., & Gershon, M. D. (2016). The bowel and beyond: The enteric nervous system in neurological disorders. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 13(9), 517-528. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2016.107

Ruigrok, T., Mantel, S., Orlandini, L., De Knegt, C., Vincent, A., & Spoor, J. (2023). Sympathetic components in left and right human cervical vagus nerve: Implications for vagus nerve stimulation. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, 17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2023.1205660

Schwartz, S. (2015). Viva vagus: Wandering nerve could lead to range of therapies. Science News, 188(11), 18.

Seki, A., Green, H., Lee, T., Hong, L., Tan, J., Vinters, H., Chen, P., & Fishbein, M. (2014). Sympathetic nerve fibers in human cervical and thoracic vagus nerves. Heart Rhythm, 11(8), 1411-1417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.04.032

Tortora, G. J., & Derrickson, B. H. (2021). Principles of anatomy and physiology (16th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Tracey, K. J. (2007). Physiology and immunology of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 117(2), 289-296. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci30555

Uijtdehaage, S. H., & Thayer, J. F. (2000). Accentuated antagonism in the control of human heart rate. Clinical Autonomic Research: Official Journal of the Clinical Autonomic Research Society, 10(3), 107-110. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02278013

Wallace, C., Glueck, E., Kuhnert, S., Brauer, P., Lemmons, C., Kilmer, M., & Barry, A. (2022). The origin of sympathetic postganglionic fibers in the cervical region of the vagus nerve. The FASEB Journal, 36. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.2022.36.s1

Return to Top