Breathing Training Protocols

What You Will Learn

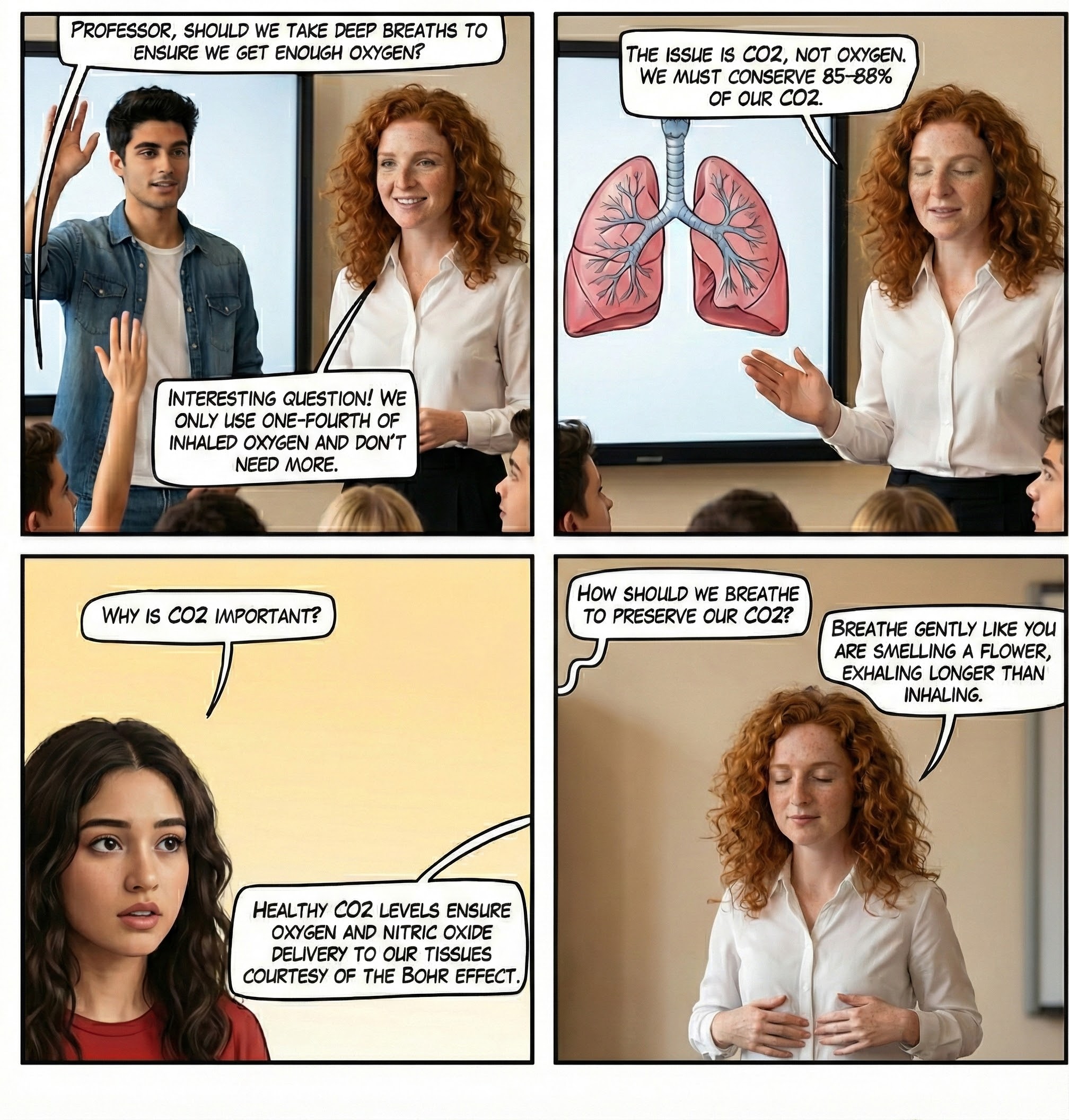

Your client's breathing patterns profoundly influence their autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular health. In this unit, you will discover how to evaluate breathing during a psychophysiological assessment, correct dysfunctional patterns like overbreathing, and teach resonance frequency breathing that exercises the baroreflex. You will learn the physiological mechanisms through which healthy breathing conserves carbon dioxide, increases oxygen delivery to tissues, and enhances heart rate variability.

Whether you are working with clients who hyperventilate during panic, athletes seeking peak performance, or patients managing chronic pain, mastering these breathing protocols will become one of your most versatile clinical tools. By the end of this unit, you will understand the medical cautions that guide safe practice, the biofeedback modalities that make breathing visible, and the coaching techniques that transform effortful gasping into effortless respiration.

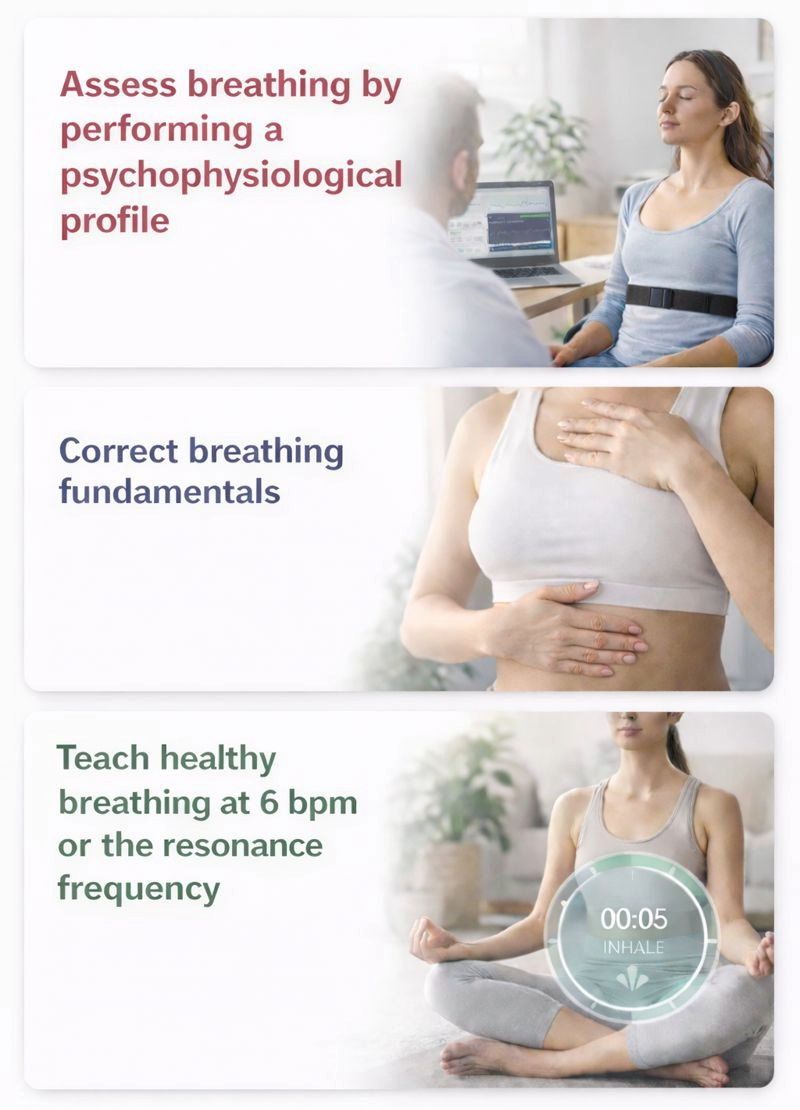

Breathing assessment provides a roadmap for training clients to replace dysfunctional breathing with healthy breathing. Correcting breathing fundamentals is critical for heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB), a form of biofeedback that trains individuals to increase heart rate variability through slow-paced breathing at the resonance frequency (RF), typically around 6 breaths per minute. Most clients need to learn three core skills: relying more on their diaphragm to ventilate the lungs, slowing their respiration rate, and breathing consistently to produce robust resonance effects.

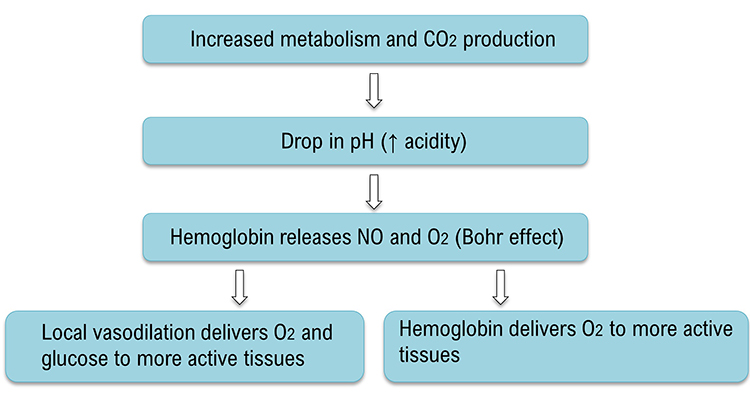

Shifting to a healthy breathing pattern corrects overbreathing by conserving 85-88% of CO2 (Khazan, 2021). Preserving CO2 lowers blood pH, which weakens the bond between hemoglobin and oxygen, increasing oxygen delivery to body tissues courtesy of the Bohr effect. Healthy breathing also dilates blood vessels, slows heart rate, and increases both respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), the natural variation in heart rate that occurs during the breathing cycle, and overall heart rate variability (HRV). These changes collectively lower blood pressure and enhance autonomic flexibility.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses V. HRV Biofeedback Strategies: D. How to teach resonance frequency breathing.

Professionals completing this unit will be able to discuss the characteristics of effortless breathing, core elements of teaching effortless breathing, physiological effects of effortless breathing, medical cautions before teaching effortless breathing, biofeedback modalities used to teach effortless breathing, and exercises to complement effortless breathing training.

Topics covered include Common Breathing Misconceptions, Healthy Breathing Roadmap, Medical Cautions, Breathing Basics, Physiological Effects of Healthy Breathing, Modalities for Teaching Healthy Breathing, Healthy Breathing Training, and Breathing Practice.

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter Lecture

Appreciation

This unit draws heavily on Dr. Inna Khazan's clinical experience and extensive writing and presentations on healthy breathing.

Common Breathing Misconceptions

One of the most persistent myths in wellness culture is that we need more oxygen. At rest, this simply is not true. Near sea level, the air we inhale contains 21% oxygen, whereas the air we exhale still contains 15% oxygen. We use only about one-quarter of the oxygen in each breath. What we actually need to do is conserve CO2 by retaining 85-88% of its volume (Khazan, 2021).

This counterintuitive fact has profound implications for biofeedback practice. When clients arrive believing they need to "breathe more deeply" to get more oxygen, they often end up overbreathing and actually reducing oxygen delivery to their tissues. Understanding this misconception allows you to reframe breathing training as a conservation practice rather than an acquisition exercise.

Healthy Breathing Roadmap

The path to healthy breathing follows a clear sequence: evaluate breathing during a psychophysiological assessment, correct breathing fundamentals, and then teach resonance frequency breathing to exercise the baroreflex. Each step builds on the previous one, and skipping ahead typically undermines clinical outcomes.

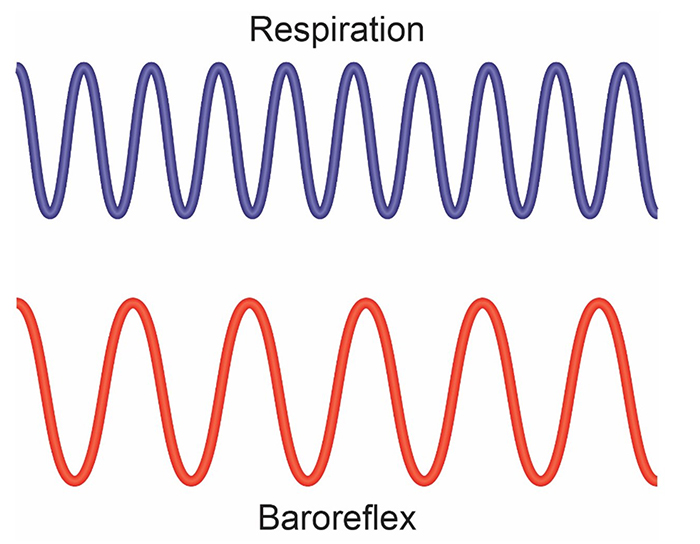

Why is this sequence so important? If we do not correct dysfunctional breathing patterns like overbreathing, they will compromise the effectiveness of HRVB training. Overbreathing is associated with respiration rates far above the resonance frequency range of 4.5-7.5 breaths per minute. The breathing pattern during overbreathing is also irregular rather than sinusoidal. Together, these characteristics preclude strong resonance effects and explain why some clients fail to respond to HRVB.

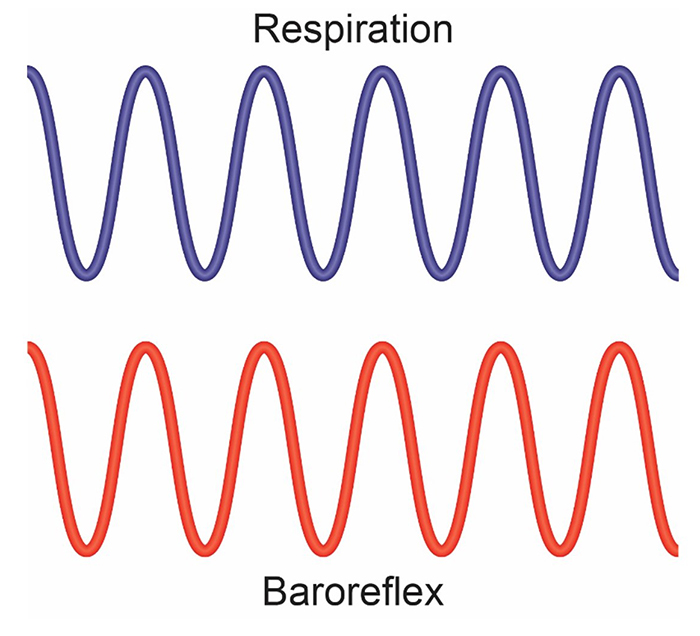

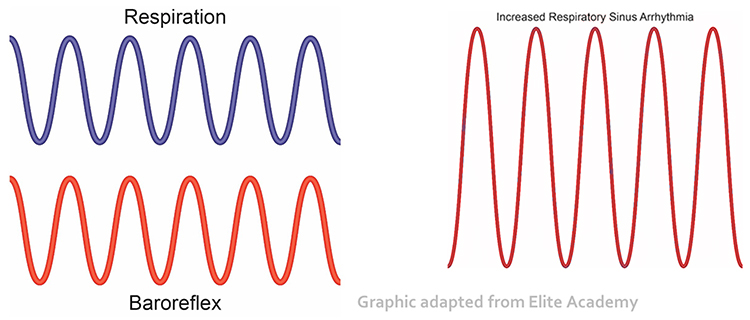

Before HRVB training, respiration and the baroreflex, the reflex system that regulates blood pressure through heart rate adjustments, are usually out of phase. This mismatch results in weak resonance effects. Think of it like two people trying to push a child on a swing: if they push at different times, the swing barely moves. HRVB brings breathing and the baroreflex into phase, like both people pushing at exactly the right moment.

HRVB training slows breathing to match the baroreflex's natural rhythm, aligning these two processes. When they work together rather than against each other, resonance effects increase dramatically.

Slowing breathing to rates between 4.5-6.5 breaths per minute for adults and 6.5-9.5 breaths per minute for children increases RSA (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014). The slower rate in adults reflects their larger lung capacity and different baroreflex timing compared to children.

Increased RSA immediately "exercises" the baroreflex without changing vagal tone or tightening blood pressure regulation. Those deeper physiological adaptations require weeks of consistent practice. HRVB can increase RSA 4-10 times compared to resting (Lehrer et al., 2021; Vaschillo et al., 2002). This means that during a single training session, a client might generate heart rate oscillations several times larger than their baseline, providing an intensive cardiovascular workout for the autonomic nervous system.

Successful clients learn to breathe near their resonance frequency and achieve ocean-like breathing cycles without pacing or feedback. The goal is autonomous skill, not dependence on technology.

We teach clients to use sound breathing mechanics throughout the day. However, it is important to recognize that slow-paced breathing is appropriate during rest and practice but not during the increased workloads of aerobic exercise. During physical activity, breathing rate naturally and appropriately increases to meet metabolic demands.

Healthy breathing follows a systematic roadmap: assess current patterns, correct dysfunctional habits, then train resonance frequency breathing. Overbreathing with rapid, irregular respiration prevents the strong resonance effects that make HRVB effective. When breathing aligns with the baroreflex rhythm, typically 4.5-6.5 breaths per minute for adults, RSA can increase 4-10 times compared to rest. This immediate "exercise" of the baroreflex creates the foundation for longer-term improvements in vagal tone and blood pressure regulation that develop over weeks of practice.

Medical Cautions

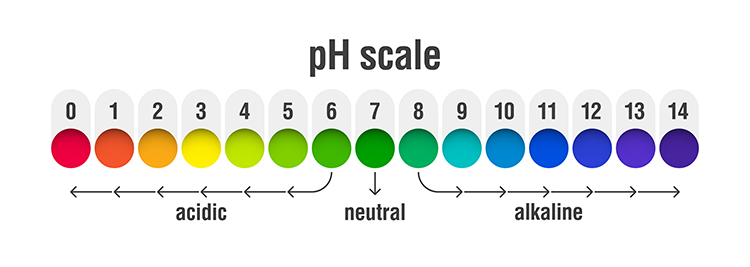

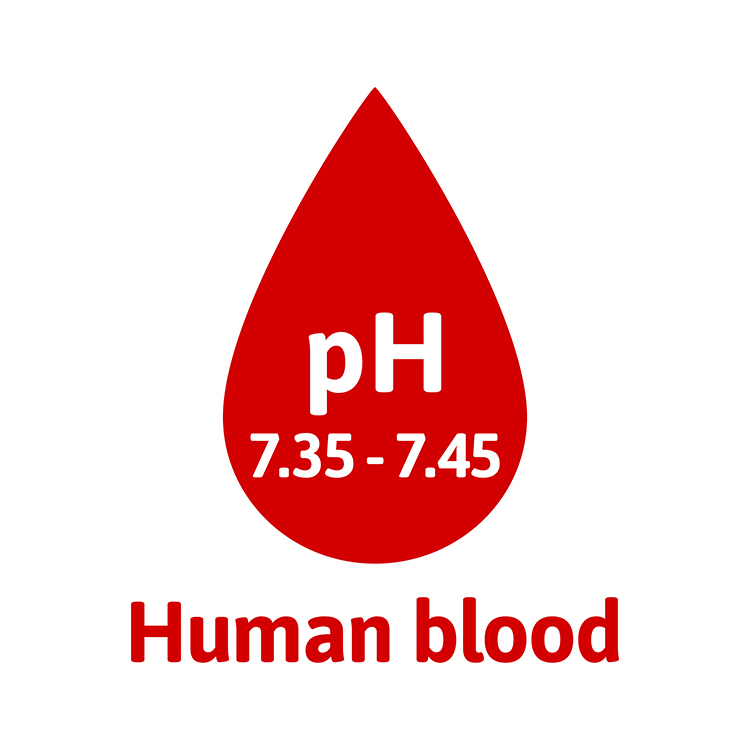

Before teaching slow-paced breathing, you must screen for conditions that could make this intervention dangerous. Clients who chronically overbreathe may experience chronic hypocapnia, abnormally low CO2 levels in the blood. Since the body cannot function with sustained high pH, the kidneys compensate by excreting bicarbonates, the salts of carbonic acid that help buffer blood pH.

This acid buffering can only restore homeostasis in the short run. As metabolism increases acidity, needed bicarbonates become depleted. Clients then experience fatigue, muscle pain, reduced physical endurance, and sodium deficit. In a vicious cycle, acidosis may increase overbreathing in a failed attempt to reduce acidity (Khazan, 2021).

Slow-paced breathing could be hazardous for clients with metabolic acidosis, a pH imbalance in which the body has accumulated excessive acid and has insufficient bicarbonate to neutralize its effects. In conditions like diabetes and kidney disease, overbreathing represents the body's attempt to compensate for abnormal acid-base balance. Slowing the breathing rate in these clients could endanger their health by removing this compensatory mechanism.

Clients diagnosed with low blood pressure should also exercise caution since slow-paced breathing might further lower blood pressure. Finally, slow-paced breathing might produce a functional overdose if your client takes anti-hypertensive medication, insulin, or a thyroid supplement. If medication adjustment appears necessary, your client should consult the supervising physician before reducing dosage (Fried & Grimaldi, 1993).

Breathing Basics

Healthy breathing matches metabolic needs, balancing the production of CO2 with breath depth and rate. We should maintain optimal breathing chemistry for each activity level. Although rapid breathing does not always signal overbreathing and slow breathing does not always indicate health, there are strong correlations (Khazan, 2021).

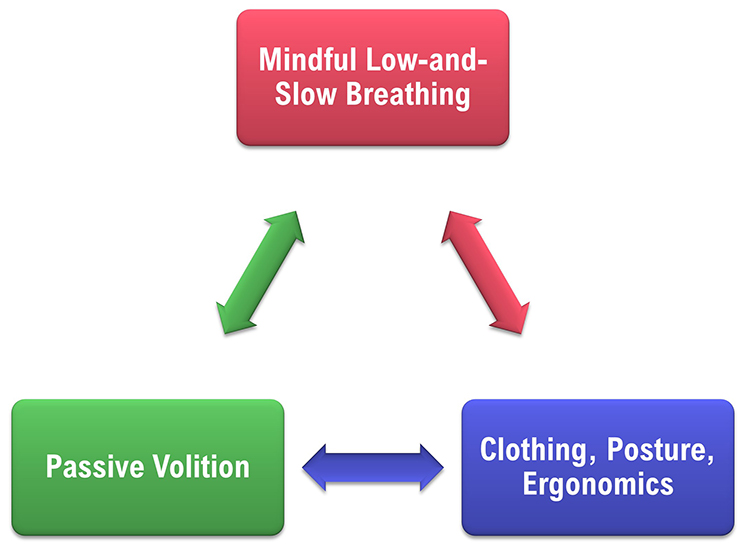

Optimal breathing shares several characteristics: it is mindful with focus on the abdomen, effortless in quality, between 5-7 breaths per minute at rest, and supported by loose clothing, good posture, and ergonomics that promote healthy respiratory mechanics.

Breathe Effortlessly

Encourage your clients to breathe effortlessly (Peper & Tibbets, 1994). The subjective experience should be that the body is "breathing itself" without conscious control. Erik Peper developed the concept of effortless breathing, a relaxed breathing method in which the client uses about 70% of maximum effort, attention settles below the waist, and the volume of air moving through the lungs increases naturally.

The technical parameters of effortless breathing include a rate of 5-7 breaths per minute for adults, with pauses following expiration that are longer than those following inspiration. Tidal volume ranges between 1,000 and 3,000 ml. Airflow is smooth and continuous, with the stomach expanding and the lower ribs and back widening during inhalation.

Discourage Deep Breaths

Clients should breathe at a comfortable depth, like smelling a flower, exhaling longer than inhaling. Breathing will calm your client when its depth and rate satisfy the resting body's metabolic needs (Khazan, 2021). Do not encourage deeper or larger breaths.

Discourage typical deep breathing, where a client inhales a massive breath and inevitably exhales too quickly because they have taken in more air than needed. This pattern promotes overbreathing, subtle breathing behaviors like sighs and yawns that reduce end-tidal CO2 (the percentage of CO2 in exhaled air at the end of exhalation) below 5%, exceeding the body's need to eliminate CO2. My colleague Don Moss no longer uses the word "deep" when coaching breathing (Moss, 2022).

Encourage Your Clients to Dress for Success

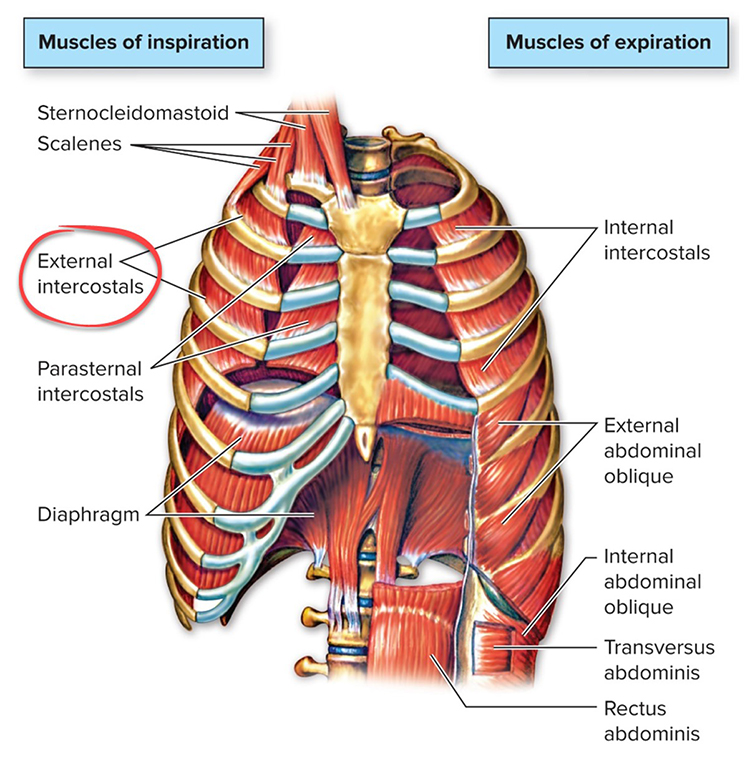

Caution clients to avoid what Peper and Tibbets (1994) called the "designer jean syndrome," in which tight clothing prevents abdominal expansion and promotes thoracic breathing. This breathing pattern primarily relies on the external intercostals to inflate the lungs, resulting in a more rapid respiration rate, excessive energy consumption, and insufficient ventilation of the lungs.

Inhale Through the Nostrils

Encourage your clients to inhale through the nostrils to filter, moisten, and warm the air before it reaches the delicate lung tissue. Exhalation can occur through the mouth or nose depending on training goals and health considerations.

Great Posture Promotes Healthy Breathing

As Lagos (2020, p. 58) recommends: "Make sure you choose a comfortable chair that allows you to sit with a straight back, the vertebrae of your spine stacked neatly on top of one another. Your feet should be flat on the floor, legs uncrossed, knees at a 90-degree angle." This alignment allows the diaphragm, the dome-shaped muscle that accounts for about 75% of air movement during relaxed breathing, to descend freely and fully.

Enhance Your Clients' Respiratory Feedback

Teach your clients to exhale using pursed lips as if blowing out a candle (Khazan, 2021). This technique slows airflow and provides tactile feedback that helps clients monitor their breathing without instruments.

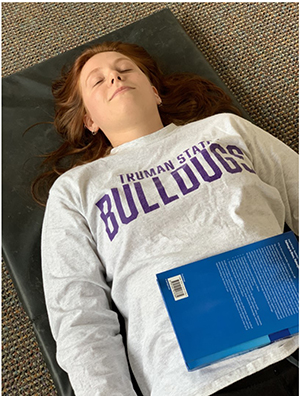

Invite clients to breathe with a weight on the abdomen while lying on the floor with knees bent. The weight, typically a book, rises during inhalation and falls during exhalation, providing clear visual and proprioceptive feedback about breathing location.

Alternatively, they can place their hands on their abdomens to feel the expansion and contraction of each breath.

Healthy breathing basics include several key principles. Breathing should be effortless, feeling as if "the body breathes itself." Discourage deep breathing, which promotes overbreathing. Optimal respiration rate is 5-7 breaths per minute with smooth, continuous airflow. Loose clothing prevents the "designer jean syndrome" that restricts abdominal expansion. Nasal inhalation filters and warms air. Good posture supports proper diaphragm movement. Pursed-lip exhalation, abdominal weights, or hand placement provide feedback that helps clients shift from thoracic to diaphragmatic patterns.

Physiological Effects of Healthy Breathing

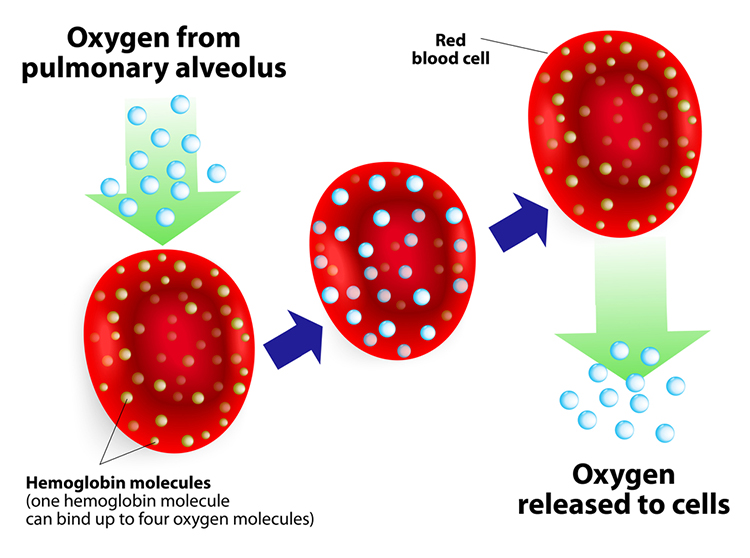

Hemoglobin, the iron-containing protein in red blood cells, transports oxygen and nitric oxide through the bloodstream. Understanding how hemoglobin works is essential for explaining the benefits of healthy breathing to your clients.

One hemoglobin molecule can carry up to four oxygen molecules. However, the critical question is not how much oxygen hemoglobin can carry, but when and where it releases that oxygen. This is where breathing patterns make a profound difference.

.jpg)

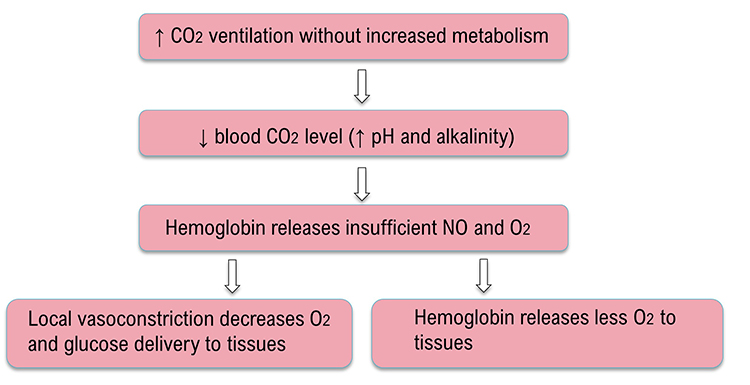

Relaxed Breathing

Relaxed diaphragmatic breathing increases metabolism and the carbon dioxide concentration of arterial blood compared to thoracic breathing. At rest, we only excrete 12-15% of blood CO2. This conservation of CO2 lowers blood pH, which triggers a crucial physiological response.

Lower pH weakens the bond between hemoglobin and oxygen, increasing oxygen delivery to body tissues. This phenomenon is called the Bohr effect, named after the Danish physiologist Christian Bohr. To explore this concept further, check out MEDCRAMvideos YouTube lecture Oxygen Hemoglobin Dissociation Curve Explained Clearly! The breathing chemistry graphics in this section were adapted from Inna Khazan.

Overbreathing

Conversely, low CO2 levels due to overbreathing or hyperventilation raise blood pH and reduce oxygen delivery to body tissues. Paradoxically, despite breathing more, oxygen remains tightly bound to the hemoglobin molecules and less is available for the brain, muscles, and organs that need it (Fox & Rompolski, 2022).

Healthy Breathing

The mantra "low and slow" captures the essence of healthy breathing. Breathing that originates low in the abdomen and proceeds at a slow pace optimizes blood chemistry for efficient oxygen delivery.

Healthy breathing can increase peripheral blood flow when the respiration rate slows to the resonance frequency range of 4.6 to 7.5 breaths per minute and end-tidal CO2 normalizes to 5% or 36 mmHg. Peripheral vasodilation increases perfusion and delivery of oxygen and glucose to the brain, reduces peripheral resistance, and promotes hand-warming.

These changes are crucial for executive functioning and treating hypertension, vascular headache, and Raynaud's disease. Breathing in the resonance frequency range can also slow heart rate and increase vagal tone and HRV. The interconnections between breathing, blood chemistry, and cardiovascular function explain why breathing training has such wide-ranging clinical applications.

Breathing chemistry directly affects oxygen delivery throughout the body. The Bohr effect explains how conserving CO2 through relaxed, slow breathing weakens the hemoglobin-oxygen bond and increases oxygen release to tissues. Overbreathing depletes CO2, raises blood pH, and keeps oxygen bound to hemoglobin, paradoxically starving tissues of oxygen. When respiration rate slows to the resonance frequency range of 4.6-7.5 breaths per minute and end-tidal CO2 normalizes around 36 mmHg, peripheral vasodilation increases blood flow to the brain and extremities while reducing blood pressure.

Biofeedback Modalities for Teaching Healthy Breathing

Four biofeedback modalities form the toolkit for teaching healthy breathing: respirometer biofeedback, accessory muscle SEMG biofeedback, capnographic (end-tidal CO2) biofeedback, and oximetric (oxygen saturation) biofeedback. Each provides different information about breathing mechanics and chemistry, and together they give you comprehensive feedback for guiding clients toward optimal patterns.

Respirometer Biofeedback

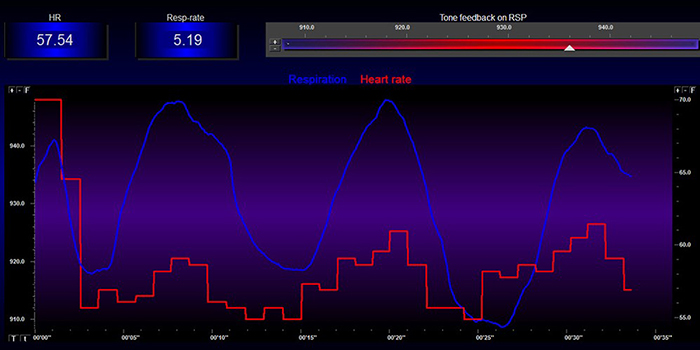

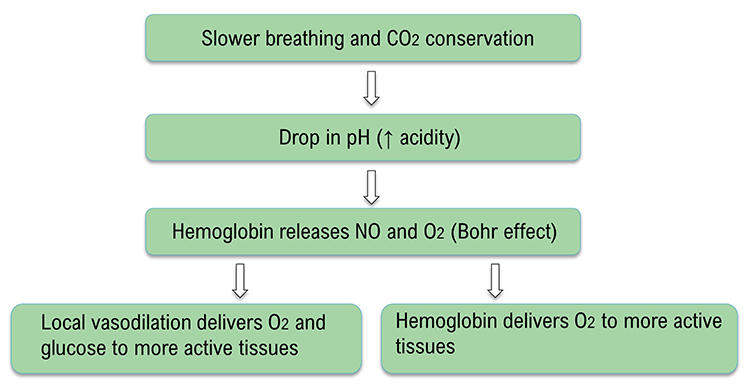

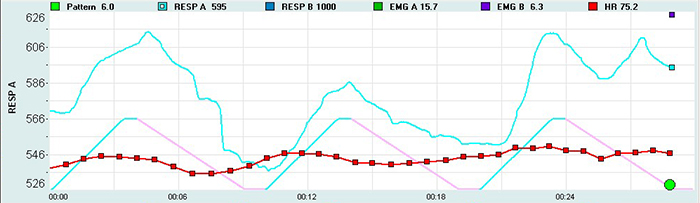

Use a respirometer display to gradually shape your client's respiration rate toward their training goal, whether that is 6 breaths per minute or their individually determined resonance frequency. The respirometer is typically a strain gauge worn around the abdomen or chest that measures expansion and contraction with each breath.

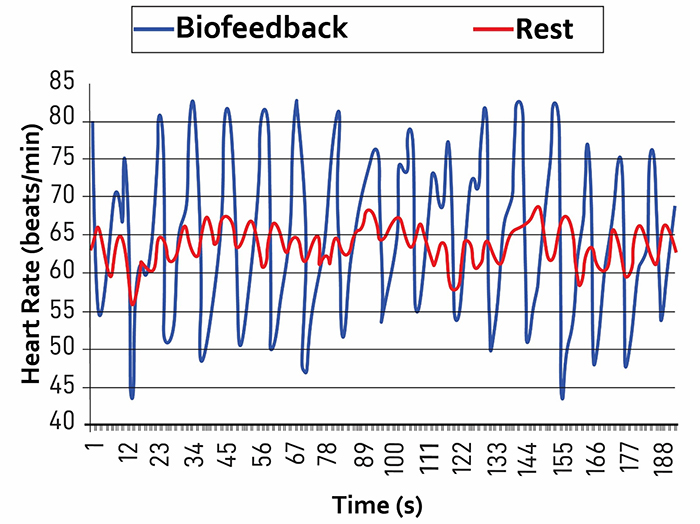

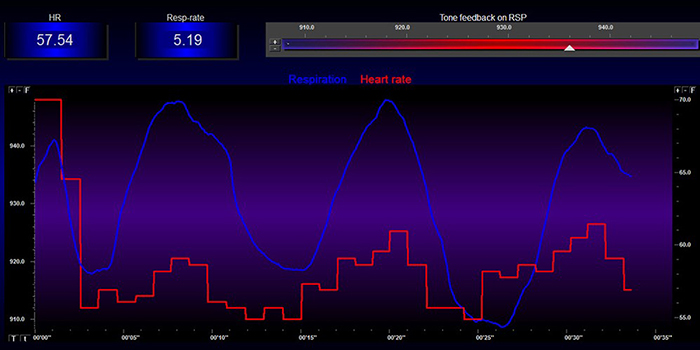

During effective HRV biofeedback, the heart rate and breathing waveforms should be synchronous. The phase difference should approach 0 degrees. You can estimate the degree of synchrony by observing heart rate change with respect to the breathing cycle: 0 degrees means the peaks and valleys are perfectly aligned, 180 degrees means heart rate increases during exhalation and decreases during inhalation, and 90 degrees means heart rate increases mid-inhalation and decreases mid-exhalation (Lehrer et al., 2013).

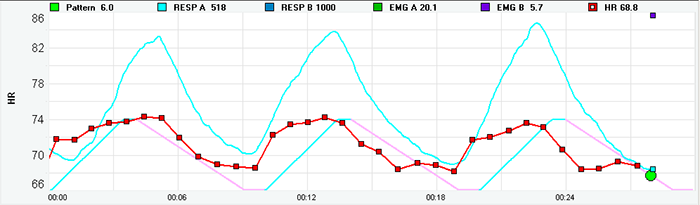

The screen below shows a mean respiration rate of 4.46 breaths per minute. Both waveforms are sinusoidal with high amplitude and nearly in-phase, meaning their peaks and valleys almost coincide. This is what success looks like in HRV biofeedback training.

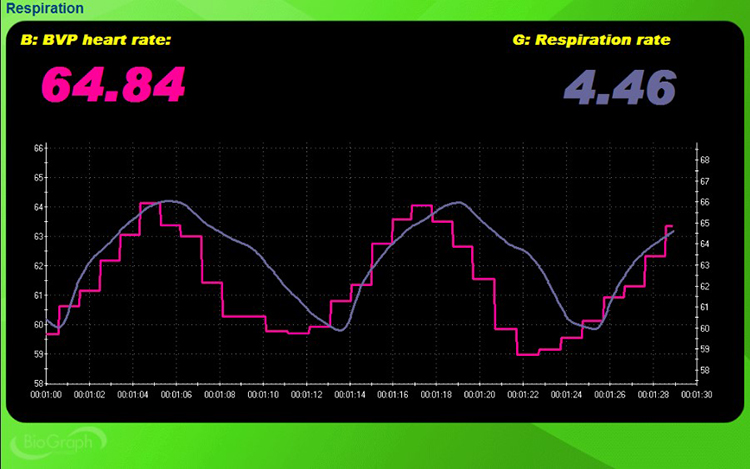

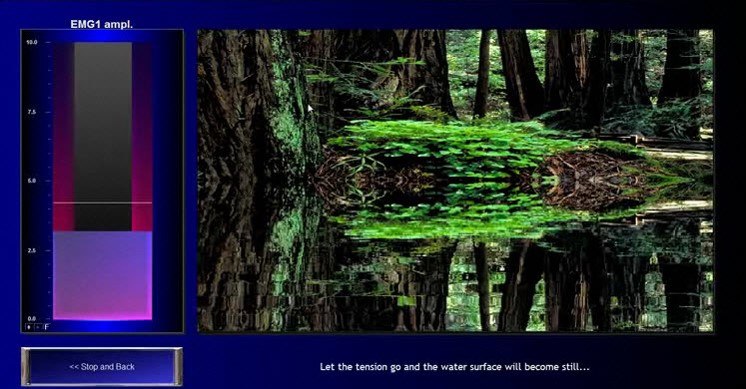

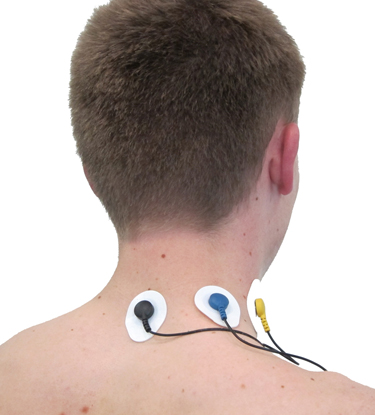

Accessory Muscle SEMG Biofeedback

The accessory muscles, including the sternocleidomastoid, pectoralis minor, scalene, and trapezius muscles, are recruited during forceful breathing and during clavicular breathing. This dysfunctional pattern relies primarily on the external intercostals and accessory muscles to inflate the lungs, resulting in a more rapid respiration rate, excessive energy consumption, and incomplete ventilation of the lungs.

Down-train accessory SEMG to values below 2 microvolts. This benchmark will vary with equipment, settings, electrode placement, posture, and amount of adipose tissue between the electrodes and muscles.

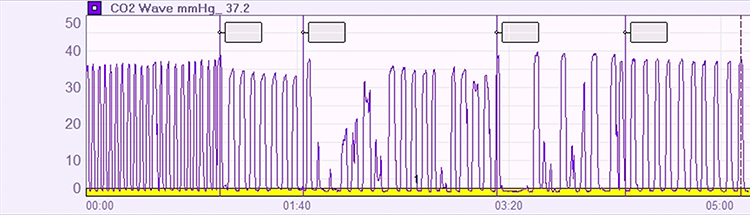

Capnometric Biofeedback

Train end-tidal CO2 to values between 35 and 45 torr, the unit of atmospheric pressure named after Torricelli that equals 1 millimeter of mercury (mmHg). Values between 35-45 torr correspond to 5%-6% CO2. Values below 33 torr may indicate overbreathing, and those above 45 torr can be caused by hypoventilation.

A capnometer monitors end-tidal CO2 by drawing exhaled air into its gas composition analysis unit and calculating the percentage of CO2 in each sample by measuring the absorption of infrared light.

Oximetric Biofeedback

A pulse oximeter utilizes a photoplethysmograph (PPG) sensor to measure blood oxygen saturation from a finger or earlobe. The device compares the red and blue wavelengths in the blood to measure hemoglobin oxygen transport.

During overbreathing, oxygen saturation (PaO2) may approach 100%. Counterintuitively, this is not a good sign. PaO2 values over 98% signal that less O2 and nitric oxide are available for body tissues because oxygen remains tightly bound to hemoglobin (Gilbert, 2019). Train clients to achieve oxygen saturation values between 95% and 98%.

Four biofeedback modalities support healthy breathing training. Respirometer biofeedback shapes respiration rate toward the training goal while monitoring heart rate synchrony. Accessory muscle SEMG biofeedback targets values below 2 microvolts to reduce unnecessary breathing effort. Capnometric biofeedback trains end-tidal CO2 to the optimal range of 35-45 torr, with values below 33 torr suggesting overbreathing. Oximetric biofeedback monitors blood oxygen saturation, with values over 98% indicating that less oxygen is available for tissues. The combination of these modalities provides comprehensive feedback for teaching healthy breathing patterns.

Comprehension Questions

- What phase relationship between heart rate and breathing waveforms indicates optimal resonance during respirometer biofeedback?

- Why would an oxygen saturation reading of 99% during training be concerning rather than reassuring?

- What end-tidal CO2 range indicates healthy breathing chemistry, and what do values below this range suggest?

- Why is accessory muscle SEMG biofeedback useful for clients who primarily breathe using their upper chest?

Healthy Breathing Training

You can teach healthy breathing as a component of weekly HRVB training sessions. Provide three or more 3-minute segments, some without feedback and pacing, each followed by coaching. Do not progress to HRVB until your client has corrected dysfunctional breathing. Attempting resonance frequency training before establishing good breathing mechanics is like trying to build a house on an unstable foundation.

The red heart rate and blue respirometer tracings are synchronous with an almost 0-degree phase relationship in the screen below. This synchrony between heart rate and breathing is the visual signature of effective training.

Mindful Breathing Awareness

Begin by helping clients develop awareness of their breathing without trying to change it. Use earplugs or fingers in the ears to increase breath awareness by reducing external distractions. The client should experience each breath without struggle, tuning in to the sensations that accompany inhalation and exhalation.

Encourage clients to allow their body to shift from exhalation to inhalation without rushing this process. They should also experience difficult emotions, images, sensations, and thoughts that may arise without judgment (Khazan, 2021). This mindful approach prevents the effortful striving that can activate the sympathetic nervous system and undermine training.

Low-and-Slow Breathing

Robert Fried (1987) recommends shifting breathing to the abdomen and slowing its rate. Clients should take normal-sized inhalations and not emphasize breath depth or volume. They should exhale slowly through the nostrils or pursed lips.

Encourage clients to wear nonrestrictive clothing, loosen their clothing to allow the diaphragm to move freely, and assume a comfortable position like reclining. Invite them to place one hand on the abdomen and the other on the chest for feedback (Khazan, 2021). The hand on the abdomen should rise more than the hand on the chest.

Some clients may find the image of a balloon helpful in shifting from thoracic to abdominal breathing and remembering when the stomach should expand and contract. During inhalation, the stomach expands, inflating the balloon. During exhalation, the stomach contracts, deflating the balloon.

Encourage mindful effortless breathing to prevent larger tidal volumes and faster exhalation that result in overbreathing. Engage passive volition by using words like "allow," "let," and "permit," and avoiding "correct," "effort," "try," and "work." Demonstrate low-and-slow breathing and allow clients several minutes of practice in your clinic.

Sample Low-and-Slow Instructions from Dr. Inna Khazan

"Let's practice low-and-slow breathing. Allow your breath to shift lower towards your abdomen and to slow down gently. To help guide your breath lower, imagine that there is a balloon in your belly. What color is it? Now, with every inhalation, imagine that you are gently inflating the balloon and with every exhalation, you are allowing the balloon to deflate."

"Do not push your stomach out, do not pull it back in. In fact, do not apply any effort at all. Provide your body with some guidance, and then let your body breathe for you. This is all about letting your breathing happen as opposed to making it happen."

"Keep in mind that your body knows exactly how to breathe low and slow. When you were a baby and a young child, you were breathing this way all the time. You have a few years of practice. This is kind of like riding a bike; you don't forget how to do it. You just need to let your body do what it knows how to do. Watch me doing this first, and then join in whenever you are ready."

"Let's shift the breath down from the chest to the belly, take a normal-sized comfortable breath in, and exhale slowly, perhaps blowing air out through pursed lips, as if you are blowing out a candle. Allow yourself to exhale fully, do not rush the next inhalation. Again, take a normal-sized comfortable breath in, exhale slowly and fully." Repeat for 5 or 6 breaths (Khazan, 2021).

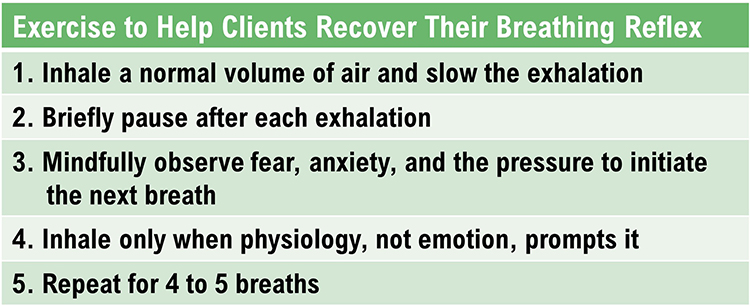

Help Clients Recover Their Breathing Reflex

The Breathing Reflex

The breathing reflex is a physiological drive to inhale in response to rising CO2 levels. Clients may override this reflex during overbreathing by inhaling too early, before CO2 levels rise to the level that would naturally trigger the next breath. This premature inhalation lowers blood CO2 levels and perpetuates the overbreathing pattern.

This "hijacking" of the breathing reflex may represent an attempt to catch one's breath due to fear of insufficient oxygen or to reduce anxiety (Khazan, 2021). Helping clients wait for the natural urge to breathe can feel counterintuitive to them, but it is essential for restoring healthy breathing chemistry.

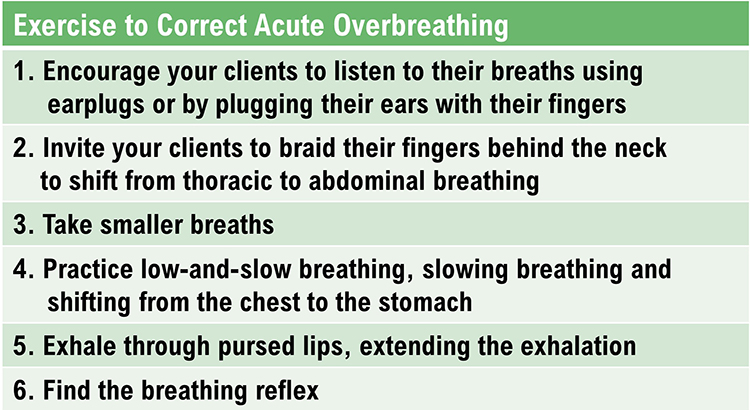

Help Clients Correct Acute Overbreathing

Clients who overbreathe are often unaware of their breathing patterns. We need to teach them to "tune in" to their breathing and recognize the signs of overbreathing. They may breathe thoracically, overusing their external intercostal muscles during inhalation instead of relying on the diaphragm.

When clients overbreathe, help them shift to abdominal breathing so that the dome-shaped diaphragm may descend more completely (Khazan, 2021). This shift not only improves ventilation but also reduces the energy cost of breathing and promotes relaxation.

.jpg)

Panic: When Overbreathing is Severe

When a client has difficulty catching their breath, this may trigger panic. The sensations of overbreathing, including lightheadedness, tingling, and chest tightness, can feel terrifying, prompting even faster breathing in a self-reinforcing cycle.

Reassure your client and invite them to hold their breath for 5-20 seconds until the sensations of overbreathing lessen. Monitor their breathing to ensure their practice of low-and-slow breathing with extended exhalations so they do not overbreathe and start another panic cycle (Khazan, 2021).

Troubleshooting

Dizziness or Shortness of Breath

These symptoms are often signs of overbreathing rather than underbreathing. Invite the client to slow their breathing, especially at the start of the exhalation, and to lengthen the exhalation. The instinct to breathe more when dizzy can be counterproductive.

Anxiety or Other Discomfort

Effortful breathing may activate the sympathetic nervous system, producing anxiety rather than the expected calm. Invite the client to switch from "trying to breathe" to "allowing the breath to happen." This subtle shift in approach can make all the difference.

Breathing is Not Relaxing

Reassure the client that this is normal and does not indicate failure. Explain that the primary purpose of breathing training is restoring healthy breathing chemistry and not immediate relaxation (Khazan, 2021). Relaxation often emerges as a secondary benefit once healthy breathing patterns become established, but it is not the goal of each practice session.

Monitor and Reduce Excessive Breathing Effort

Several "red flags" can signal effortful breathing that undermines training. First, accessory muscle (such as trapezius and scalene) SEMG increases when clients try too hard. A trapezius-scalene placement, with active SEMG electrodes located on the upper trapezius and scalene muscles, is particularly sensitive to breathing effort.

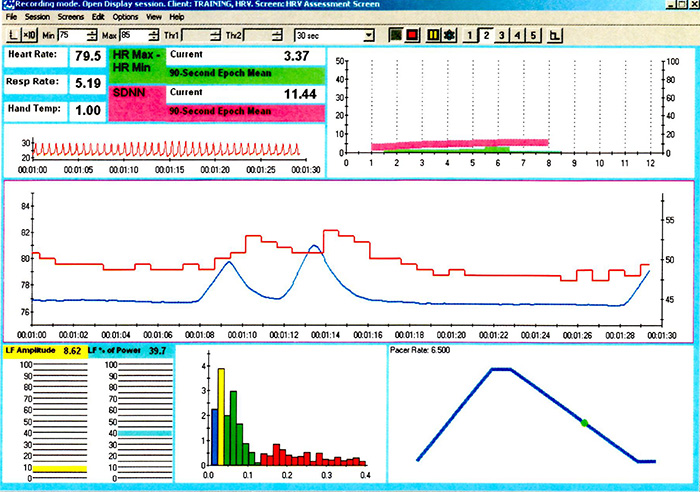

A BioGraph Infiniti accessory muscle training screen used to correct clavicular breathing is shown below.

Second, end-tidal CO2 often declines with effort because trying harder leads to overbreathing. A capnometer can show whether values fall below 36 mmHg. See the segment from 01:40 to 03:20 in the tracing below.

Third, the respirometer waveform may lose its smoothness when clients try harder. The sinusoidal pattern becomes irregular, with jagged edges and inconsistent timing.

Breathing Practice

Breathing practice between sessions helps generalize breathing skills to everyday life. Clients may benefit from breathing apps and pacers to guide their practice. Encourage them to practice an exercise for 20 minutes daily, log the activity, and discuss it at the start of the next training session. This accountability structure dramatically improves compliance and outcomes.

Also encourage mindful low-and-slow breathing throughout the day, not just during formal practice. Invite your client to observe their breathing several times a day in different settings. When they find themselves overbreathing, they can remind themselves to breathe with less effort.

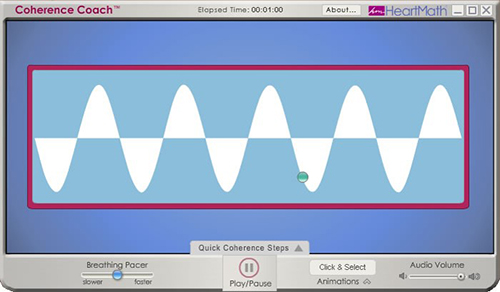

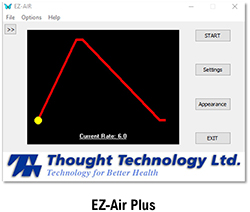

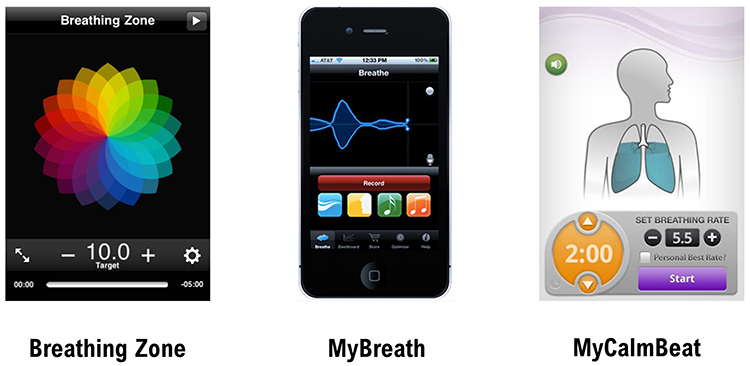

Encourage Practice with Breathing Apps and Breathing Pacers

You may use computer, tablet, and smartphone apps that provide auditory or visual pacing. Try them out yourself to find the apps that offer the adjustability and ease of use best suited for your clients.

Consider Coherence Coach and EZ-Air Plus for computers. Both programs allow you to customize breathing rates and provide visual feedback that clients can follow during practice.

|

|

Popular apps are available for both Android and Apple platforms. The proliferation of breathing apps means you can find options that match your clients' preferences and needs.

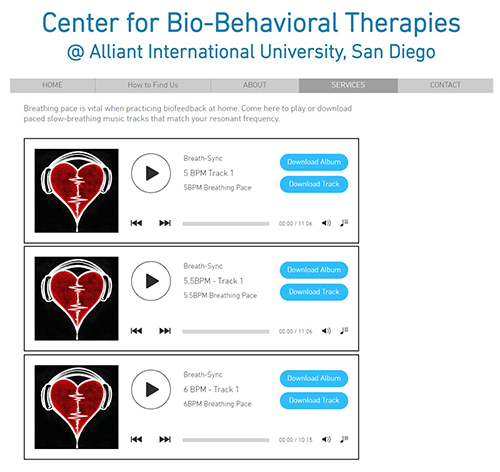

Assign practice with breathing pacers and then gradually fade them as clients develop internal timing. The goal is autonomous skill that does not depend on technology. Click on the Alliant link to download these free tracks.

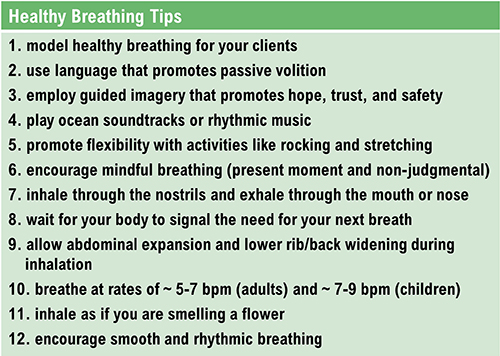

Healthy Breathing Tips

Erik Peper (1994) and Inna Khazan (2021) have proposed several invaluable breathing suggestions that summarize the key principles of healthy breathing practice.

|

|

The BioGraph Infiniti display below shows healthy inhalation and exhalation in which the abdomen gradually expands and contracts. Notice the smooth, rhythmic quality of the waveform.

The BioTrace+/NeXus-10 training screen below was designed to teach effortless breathing. The balloon's inflation and deflation mirror the respiration sensor's rhythmic expansion and contraction, providing an intuitive visual metaphor for clients.

Three "red flags" signal excessive breathing effort: increased accessory muscle SEMG, declining end-tidal CO2, and loss of smooth respirometer waveforms. Regular home practice with breathing apps and pacers, 20 minutes daily, helps generalize skills to everyday life. Clients should observe their breathing throughout the day and self-correct when they notice overbreathing. Multiple computer programs and mobile apps are available, and free paced breathing tracks can be downloaded from Alliant International University. The key coaching principle remains consistent: breathing should feel effortless, as if "the body breathes itself."

Comprehension Questions

- What three physiological indicators suggest that a client is using excessive effort during breathing training?

- How long should clients practice breathing exercises daily, and what should they bring to the next session?

- Why would deep breathing produce a smaller peak-to-trough heart rate difference than healthy breathing during HRV biofeedback?

- What is the recommended approach when a client experiences panic during an overbreathing episode?

- How does "passive volition" differ from typical coaching language, and why is it important for breathing training?

Cutting Edge Topics

Slow Breathing and the Autonomic Nervous System

Recent research continues to illuminate the mechanisms through which slow-paced breathing affects autonomic function. Studies using advanced neuroimaging techniques have shown that resonance frequency breathing activates specific brain regions involved in interoceptive awareness and emotional regulation. The insular cortex and anterior cingulate cortex show increased activity during slow breathing, suggesting that the practice enhances the brain's capacity to monitor and regulate internal physiological states. These findings help explain why breathing training has effects that extend far beyond simple relaxation.

Breathing and the Inflammatory Response

Emerging evidence suggests that slow breathing may modulate inflammatory processes through vagal pathways. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, mediated by the vagus nerve, can reduce the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Since resonance frequency breathing increases vagal tone, researchers are investigating whether regular practice might have anti-inflammatory effects relevant to conditions ranging from autoimmune disorders to cardiovascular disease. This line of research could significantly expand the clinical applications of breathing training.

Personalized Breathing Protocols

The field is moving toward more individualized approaches to breathing training. While 6 breaths per minute serves as a useful starting point for most adults, researchers are developing more precise methods for determining each person's optimal resonance frequency. Advanced algorithms that analyze real-time HRV data may soon allow biofeedback systems to automatically adjust pacing to maximize resonance effects for each individual session. This personalization could improve outcomes for clients who do not respond well to standard protocols.

Wearable Technology and Continuous Monitoring

Consumer wearable devices now incorporate breathing guidance features, though their accuracy varies considerably. Research groups are validating these devices against laboratory-grade equipment to determine which products can reliably support home practice. The potential for continuous, passive monitoring of breathing patterns throughout the day could transform our understanding of how habitual breathing affects health outcomes. Clinicians may eventually be able to identify problematic breathing patterns that occur outside of training sessions.

Assignment

The screens below show breathing with a hand on the abdomen and then a book. Which produced the best results? Why?

Inspect the blue respirometer tracings. The bottom tracing is more sinusoidal, showing smoother, more wave-like breathing. Examine the red heart rate tracings. The bottom tracing is also more sinusoidal, indicating better resonance effects.

Finally, check for synchrony between the two signals. The bottom tracing shows a closer alignment of the peaks and valleys for both signals, meaning heart rate and breathing are more in phase. For this client, the book on the abdomen method was more effective because it provided stronger proprioceptive feedback that helped establish better diaphragmatic breathing.

Which breathing problem is illustrated by the screen below? How did this problem affect the distribution of HRV power?

The 12-second pause after the second breath is consistent with apnea, or breath suspension. Note the low LF amplitude and dominant frequency in the VLF range due to disordered breathing. Finally, observe the absence of a sinusoidal waveform in the red heart rate tracing and the absence of synchrony between both the heart rate and respirometer signals. This demonstrates how irregular breathing disrupts the resonance effects that HRVB training aims to produce.

These recordings are from chronic pain patients who received treatment in an interdisciplinary chronic pain program.

Glossary

accessory muscles: the sternocleidomastoid, pectoralis minor, scalene, and trapezius muscles, which are used during forceful breathing, as well as during clavicular and thoracic breathing.

apnea: breath suspension.

bicarbonates: the salts of carbonic acid that contain HCO3.

Bohr effect: the phenomenon in which lower blood pH (higher CO2) weakens the bond between hemoglobin and oxygen, increasing oxygen delivery to body tissues.

capnometer: an instrument that monitors the carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration in an air sample (end-tidal CO2) by measuring the absorption of infrared light.

clavicular breathing: a breathing pattern that primarily relies on the external intercostals and the accessory muscles to inflate the lungs, resulting in a more rapid respiration rate, excessive energy consumption, and incomplete ventilation of the lungs.

diaphragm: the dome-shaped muscle whose contraction enlarges the vertical diameter of the chest cavity and accounts for about 75% of air movement into the lungs during relaxed breathing.

effortless breathing: Erik Peper's relaxed breathing method in which the client uses about 70% of maximum effort, attention settles below the waist, and the volume of air moving through the lungs increases. The subjective experience is that "my body breathes itself."

end-tidal CO2: the percentage of CO2 in exhaled air at the end of exhalation.

heart rate variability (HRV): the variation in time intervals between consecutive heartbeats.

heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB): a form of biofeedback that trains individuals to increase heart rate variability, typically through slow-paced breathing at the resonance frequency.

hemoglobin: the iron-containing protein in red blood cells that transports oxygen and carbon dioxide through the bloodstream.

hyperventilation syndrome (HVS): a respiratory disorder that has been increasingly reconceptualized as a behavioral breathlessness syndrome in which hyperventilation is the consequence and not the cause of the disorder. The traditional model that hyperventilation results in reduced arterial CO2 levels has been challenged by the finding that many HVS patients have normal arterial CO2 levels during attacks.

metabolic acidosis: a pH imbalance in which the body has accumulated excessive acid and has insufficient bicarbonate to neutralize its effects. In diabetes and kidney disease, hyperventilation attempts to compensate for abnormal acid-base balance. Slower breathing could endanger health.

overbreathing: subtle breathing behaviors like sighs and yawns reduce end-tidal CO2 below 5%, exceeding the body's need to eliminate CO2.

pulse oximeter: a device that measures dissolved oxygen in the bloodstream using a photoplethysmograph sensor placed against a finger or earlobe.

resonance frequency (RF): the frequency at which a system, like the cardiovascular system, can be activated or stimulated.

respiratory amplitude: the excursion of an abdominal strain gauge.

respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA): the natural variation in heart rate that occurs during the breathing cycle, with heart rate increasing during inhalation and decreasing during exhalation.

reverse breathing: the abdomen expands during exhalation and contracts during inhalation, often resulting in incomplete ventilation of the lungs.

thoracic breathing: a breathing pattern that primarily relies on the external intercostals to inflate the lungs, resulting in a more rapid respiration rate, excessive energy consumption, and insufficient ventilation of the lungs.

torr: the unit of atmospheric pressure, named after Torricelli, which equals 1 millimeter of mercury (mmHg) and is used to measure end-tidal CO2.

trapezius-scalene placement: active SEMG electrodes are located on the upper trapezius and scalene muscles to measure respiratory effort.

References

Bax, A., Robinson, T., Goedde, J., & Shaffer, F. (2007). The Cousins relaxation exercise increases heart rate variability [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 32, 52–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-007-9032-z

Fox, S. I., & Rompolski, K. (2021). Human physiology (16th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Fried, R. (1987). The hyperventilation syndrome: Research and clinical treatment. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fried, R., & Grimaldi, J. (1993). The psychology and physiology of breathing. Springer.

Gevirtz, R. N. (2005). Heart rate variability biofeedback in clinical practice. AAPB Fall workshop.

Gevirtz, R. N., Lehrer, P. M., & Schwartz, M. S. (2016). Cardiorespiratory biofeedback. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.), Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (4th ed., pp. 196-213). Guilford Press.

Gilbert, C. (2012). Pulse oximetry and breathing training. Biofeedback, 40(4), 137-141. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-40.4.04

Gilbert, C. (2019). A guide to monitoring respiration. Biofeedback, 47(1), 6-11. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-47.1.02

Kabins, A., Goedde, J., Layne, B., & Grant, J. (2008). Brief coaching increases inhalation volume [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 33(3), 174.

Khazan, I. Z. (2013). The clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Khazan, I. (2019). Biofeedback and mindfulness in everyday life: Practical solutions for improving your health and performance. W. W. Norton & Company.

Khazan, I. (2021). Respiratory anatomy and physiology. BCIA HRV Biofeedback Certificate of Completion Didactic workshop.

Lagos, L. (2020). Heart breath mind: Train your heart to conquer stress and achieve success. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Lehrer, P., & Gevirtz, R. (2014). Heart rate variability biofeedback: How and why does it work? Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756

Lehrer, P., Vaschillo, B., Zucker, T., Graves, J., Katsamanis, M., Aviles, M., & Wamboldt, F. (2013). Protocol for heart rate variability biofeedback training. Biofeedback, 41(3), 98-109. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.3.08

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E., Vaschillo, B., Lu, S. E., Eckberg, D. L., Edelberg, R., . . . Hamer, R. M. (2003). Heart rate variability biofeedback increases baroreflex gain and peak expiratory flow. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(5), 796-805.

Lehrer, P. M., Woolfolk, R. L., & Sime, W. E. (Eds.). (2021). Principles and practice of stress management (4th ed.). Guilford Press.

Moss, D. (2022). HRV biofeedback bootcamp. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Peper, E., Gibney, K. H., & Holt, C. F. (2002). Make health happen: Training yourself to create wellness (2nd ed.). Kendall Hunt Publishing Company.

Peper, E., Gibney, K. H., Tylova, H., Harvey, R., & Combatalade, D. (2008). Biofeedback mastery: An experiential teaching and self-training manual. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Peper, E., & Tibbets, V. (1994). Effortless diaphragmatic breathing. Physical Therapy Products, 6(2), 67-71.

Shaffer, F., Bergman, S., & Dougherty, J. (1998). End-tidal CO2 is the best indicator of breathing effort [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 23(2).

Shaffer, F., Bergman, S., & White, K. (1997). Indicators of diaphragmatic breathing effort [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 22(2), 145.

Shaffer, F., Greve, E., & Reinagel, K. (1996). Predictors of inhalation volume [Abstract]. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 21(4), 352.

Shaffer, F., Mayhew, J., Bergman, S., Dougherty, J., & Irwin, D. (1999). Designer jeans increase breathing effort [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 24(2), 124-125.

Shaffer, F., & Moss, D. (2006). Biofeedback. In Y. Chun-Su, E. J. Bieber, & B. Bauer (Eds.), Textbook of complementary and alternative medicine (2nd ed.). Informa Healthcare.

Vaschillo, E., Lehrer, P., Rishe, N., & Konstantinov, M. (2002). Heart rate variability biofeedback as a method for assessing baroreflex function: A preliminary study of resonance in the cardiovascular system. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 27, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014587304314

Zerr, C., Kane, A., Vodopest, T., Allen, J., Hannan, J., Fabbri, M., . . . Shaffer, F. (2015). Does inhalation-to-exhalation ratio matter in heart rate variability biofeedback? [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 40(2), 135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-015-9282-0

Return to Top