HRV Training Protocols

What You Will Learn

Heart rate variability biofeedback represents one of the most promising self-regulation interventions available to clinicians today. This chapter guides you through the complete process of delivering HRV biofeedback, from essential medical screening to the practice assignments that bridge clinic learning to everyday life. You will discover why the client-practitioner relationship forms the foundation of successful training, learn to recognize subtle signs of excessive effort that can sabotage progress, and master the art of selecting displays and pacing strategies that match each client's unique learning style.

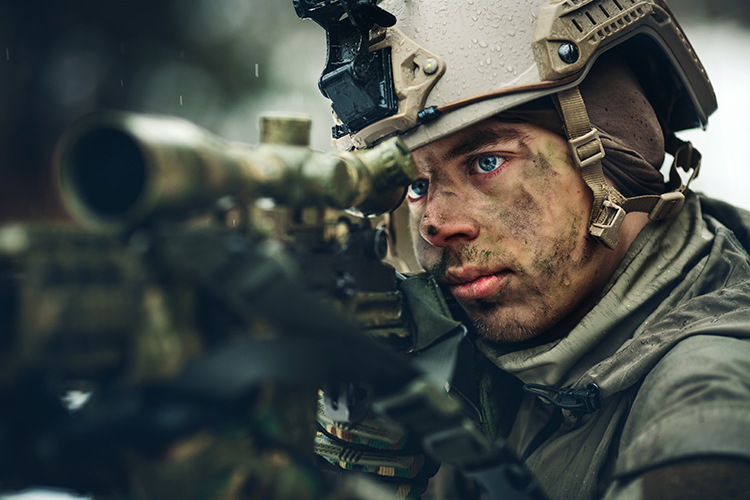

Whether you work in the VA system, a hospital rehabilitation unit, a private clinic, or with elite athletes, this chapter provides practical knowledge you can apply immediately. By the end, you will understand not only what to do but why each element of the training protocol matters for your clients' long-term success.

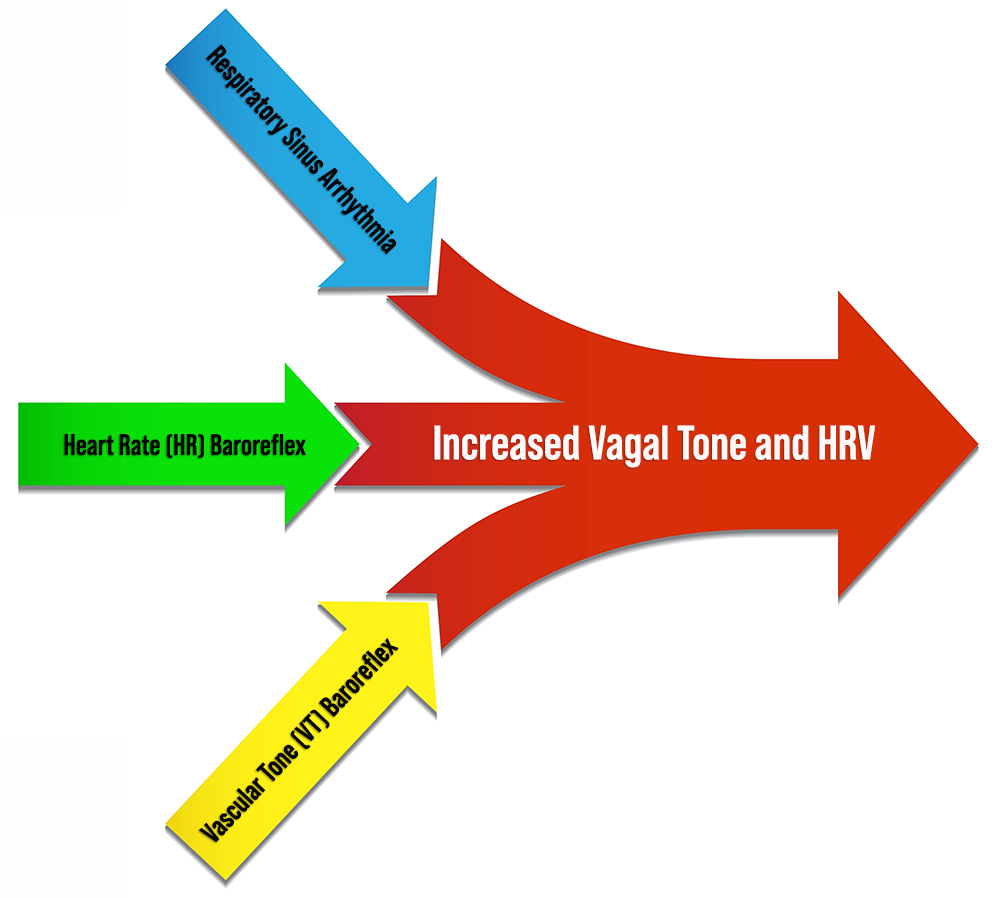

Heart rate variability biofeedback aims to exercise the baroreceptor reflex, a mechanism that provides negative feedback control of blood pressure, and the vascular tone rhythm, the rhythmic oscillation in blood vessel diameter that contributes to blood pressure regulation and HRV. By stimulating these systems, HRVB enhances homeostatic regulation, builds regulatory reserve, and strengthens executive functions (Gevirtz, 2021). Think of it as taking the cardiovascular system to the gym: just as resistance training builds muscle strength and endurance, HRVB builds the cardiovascular system's capacity to respond adaptively to stress.

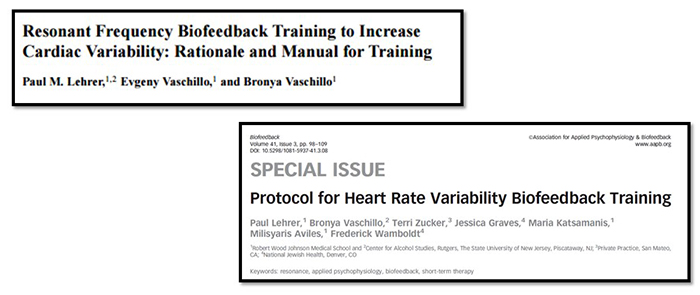

The field owes much of its clinical foundation to Lehrer and colleagues (2000, 2013), who published detailed descriptions of their HRVB resonance frequency protocol. These protocols have become the standard reference for clinicians worldwide, providing step-by-step guidance for assessment and training that has been validated across dozens of clinical trials.

Don Moss poses a deceptively simple question: "Why do we train?" The answer cuts to the heart of our work. Clinicians providing HRVB training seek to improve their clients' ability to self-regulate, promote health, and enhance quality of life and performance. These goals remain constant whether you are working with a combat veteran managing PTSD, a cardiac patient in rehabilitation, or an Olympic athlete pursuing peak performance.

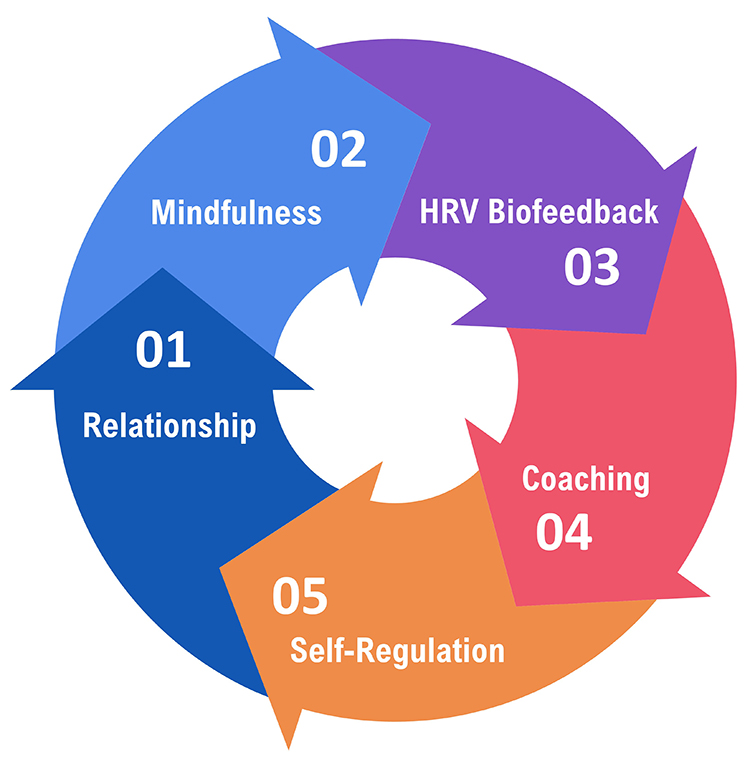

Core Elements of HRV Biofeedback

The client-practitioner relationship stands as the foundation of all biofeedback and neurofeedback training. HRV biofeedback reaches its full potential when both clinician and client practice mindfulness, fostering the self-awareness and sense of agency that drive lasting change. Effective coaching transforms technical feedback into meaningful learning experiences (Khazan, 2019).

Mindfulness involves "paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally" (Kabat-Zinn, 1994). In the context of HRV training, mindfulness serves as the bridge between physiological feedback and behavioral change. When clients observe their heart rate patterns without judgment, they become curious scientists of their own physiology rather than frustrated students chasing numbers.

Mindfulness guides the trial-and-error process underlying self-regulation by helping clients draw connections between their actions, internal feedback, and results. A veteran might notice that memories of deployment increase heart rate irregularity, while focusing on the breath creates smoother, more wavelike patterns. These insights, accumulated through mindful observation, form the foundation of lasting self-regulation skills.

Through this process, clients discover their unique psychophysiological response patterns. One person may find that visualizing ocean waves produces the smoothest heart rate oscillations, while another achieves the same result through counting or prayer. This individual variability is a feature, not a bug. The feedback helps each client identify which strategies best increase their respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), the rhythmic increase in heart rate during inhalation and decrease during exhalation, and their overall heart rate variability (HRV).

Mindfulness also supports emotional self-regulation by teaching resilience, defined as adapting effectively to new challenges, stressors, threats, and trauma. For a first responder or military service member, resilience means returning to baseline functioning after acute stress. For a chronic pain patient, it means maintaining equilibrium despite ongoing discomfort. The skills are fundamentally the same, even as the contexts differ.

.jpg)

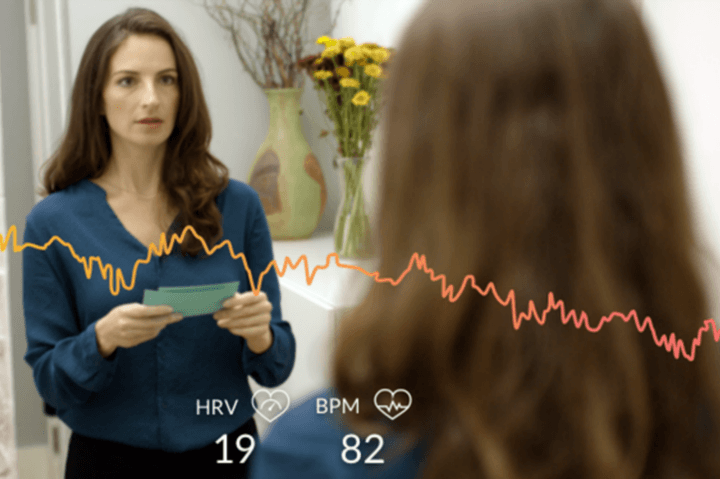

Modern wearable technology extends mindfulness training beyond the clinic. Devices like Lief Therapeutic's wearable signal clients with vibrations when stress responses are detected, enhancing awareness of triggers in everyday situations. This ecological momentary intervention transforms the smartphone notification into a cue for brief self-regulation practice.

Emotional self-regulation encompasses the self-monitoring, initiation, maintenance, and modulation of rewarding and challenging emotions, along with the avoidance and reduction of high levels of negative affect (Bridges, Denham, & Ganiban, 2004). This capacity matters for nearly every clinical population you will encounter, from anxiety disorders to cardiac rehabilitation to performance optimization.

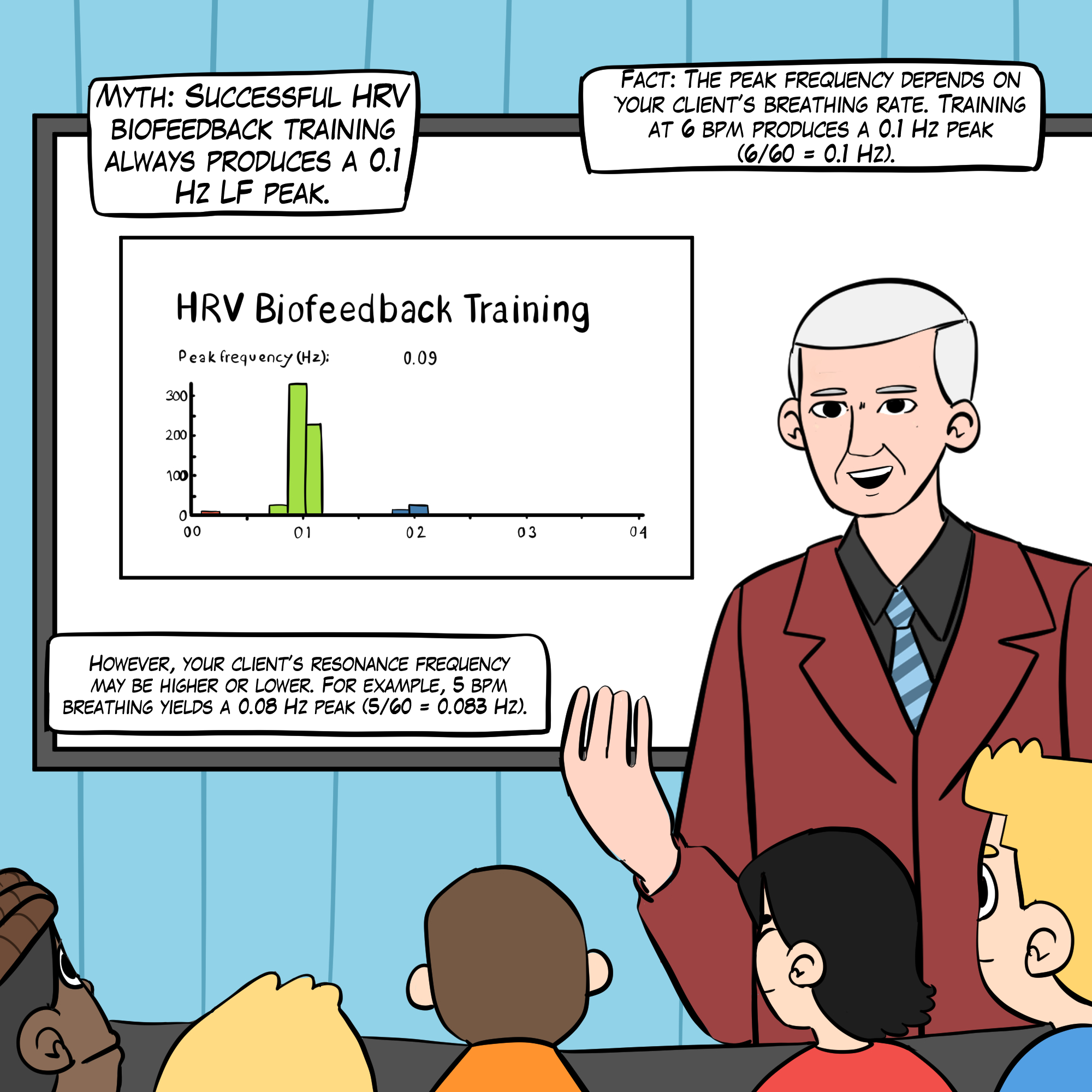

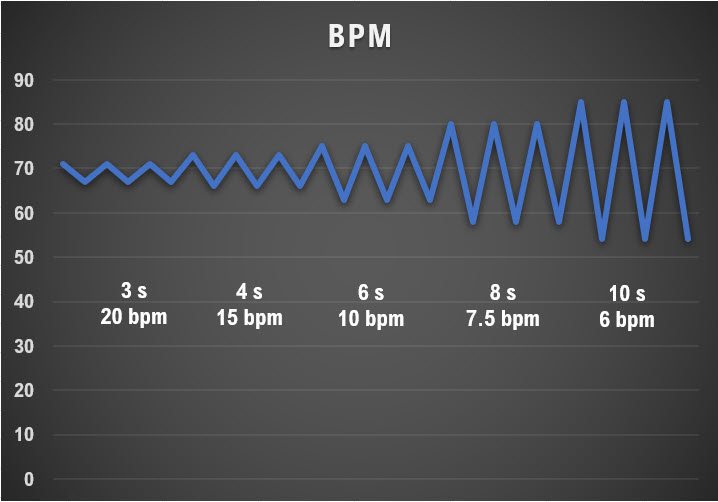

Slow-paced breathing involves healthy breathing near an individual's unique resonance frequency (RF), the frequency at which the cardiovascular system can be most effectively stimulated. While many practitioners default to 6 breaths per minute (bpm), individual resonance frequencies typically range from 4.5 to 6.5 bpm. HRV biofeedback does not train clients to chase a magic number; rather, it helps each person find their optimal breathing rate. A client whose RF is 5.0 bpm will not benefit from forcing themselves to breathe at 6.0 bpm.

The physiological mechanism is elegant: HRV biofeedback stimulates the baroreceptor reflex and vascular tone rhythm simultaneously. When breathing occurs at resonance frequency, these two oscillating systems align in phase, producing maximum heart rate oscillation and maximum stimulation of vagal pathways. Over time, this repeated stimulation increases vagal tone and overall HRV, much like repeated weight training increases muscle strength.

Mindful low-and-slow breathing amplifies RSA in a predictable way. The graphic below, adapted from Grossman and Kollai (1993), demonstrates that RSA (shown as the change in heart rate from inhalation to exhalation) increases as respiration rate approaches 6 bpm. This relationship explains why resonance frequency training is so powerful: it positions breathing at the rate that produces maximum heart rate oscillation.

Dr. Paul Lehrer provides an excellent introduction to these concepts in his resonance frequency breathing and heart rate variability biofeedback presentation from Breathe 2022.

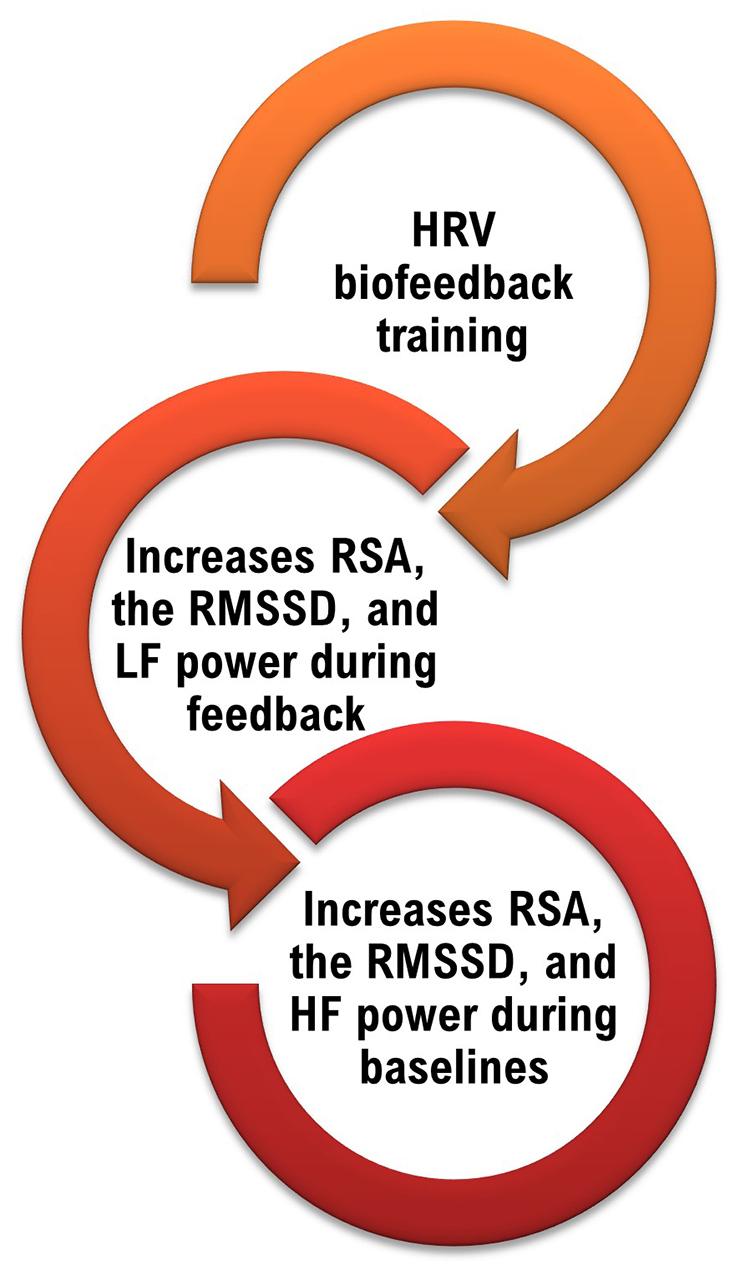

A HRV Biofeedback Koan

Here is a paradox that often confuses new clinicians: during slow-paced breathing at resonance frequency, your client will show increased peak-to-trough heart rate differences, higher RMSSD, and elevated low-frequency (LF) power. However, the ultimate goal is not to increase LF power during training sessions. Instead, after weeks of practice, clients should demonstrate expanded peak-to-trough HR fluctuations, increased RMSSD, and elevated high-frequency (HF) power when breathing at typical rates without feedback or pacing (Gevirtz, 2021).

Think of it this way: the training itself looks different from the outcome. Athletes lift heavy weights in the gym, but the goal is to perform better on the field without any weights at all. Similarly, HRVB clients breathe slowly with feedback to build cardiovascular fitness that transfers to everyday life without feedback or deliberate slow breathing.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses V. HRV Biofeedback Strategies: A. How to explain HRV Biofeedback to a client, E. How to structure an HRV biofeedback training session, F. How to augment training with emotional regulation strategies, G. HRV biofeedback side effects and contraindications, and H. Practice assignments to promote generalization.

For deeper background, we encourage you to read Lehrer and Gevirtz's (2014) excellent Frontiers in Psychology overview, Heart rate variability: How and why does it work?

This unit covers Medical Cautions, Clinical Tips When You Start HRV Biofeedback Training, HRV Biofeedback Training, and Practice Assignments.

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter Lecture

Medical Cautions

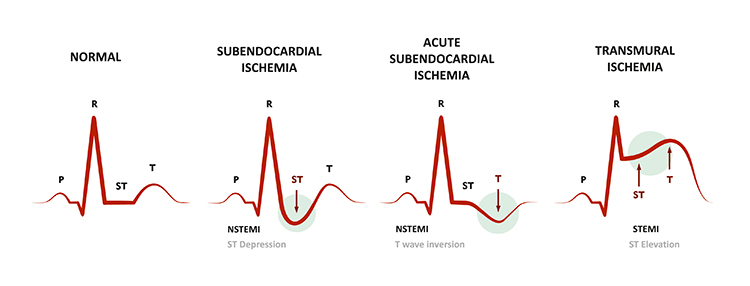

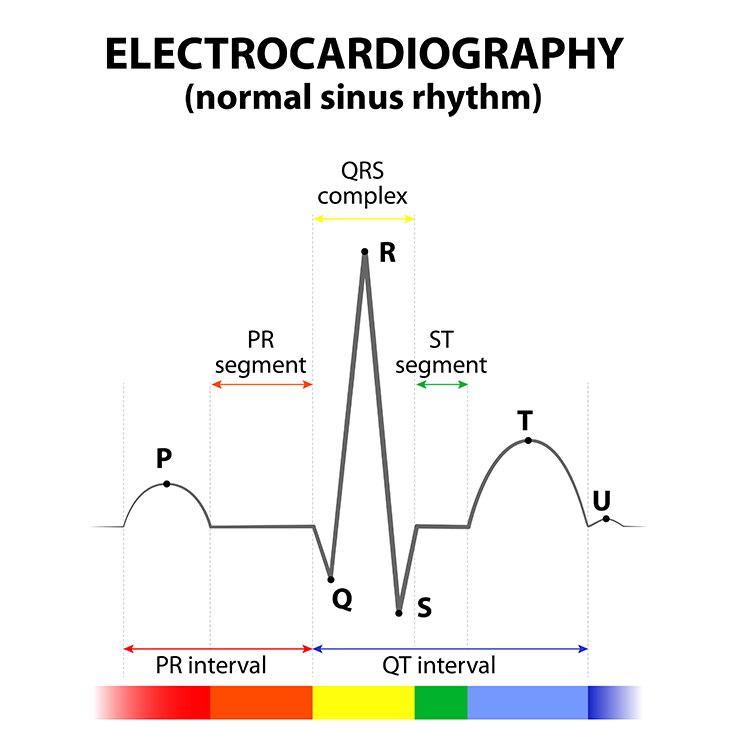

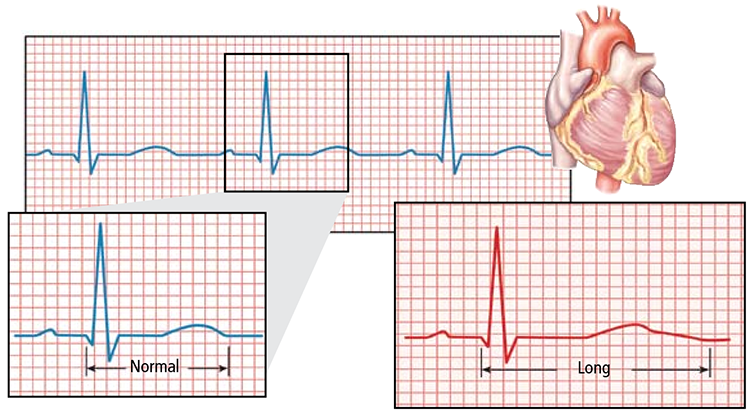

Before beginning HRVB training, clinicians must screen for cardiac abnormalities that could compromise patient safety. This screening is not optional; it is a fundamental component of responsible practice. Examine ECG morphology for evidence of arrhythmias, ischemia, and prolonged QT intervals (Drew et al., 2004). When abnormalities appear, encourage clients to consult with their physicians before proceeding. Training should only continue if the physician considers it appropriate.

Atrial fibrillation, the most common cardiac arrhythmia, involves rapid and irregular contraction of the two upper atrial chambers. On the ECG, you will see an absence of distinct P waves and an irregularly irregular ventricular response. Clients with atrial fibrillation present unique challenges for HRV measurement because the arrhythmia itself produces extreme variability unrelated to autonomic function.

Ischemia, insufficient blood supply to cardiac tissue, produces characteristic depression of the ST segment on the ECG. The ST segment represents the period between ventricular depolarization and repolarization. Compare the normal ST segment in the left panel with the depressed segment indicating subendocardial ischemia in the right panel. If you observe ST depression during a training session, stop immediately and refer the client for medical evaluation.

The QT interval signals the depolarization and repolarization of the ventricles. This interval, measured from the beginning of the Q wave to the end of the T wave, reflects the total time required for the ventricles to complete one electrical cycle.

A prolonged QT interval carries significant clinical risk. This finding is associated with increased vulnerability to ventricular tachyarrhythmias, which can result in cardiac arrest and sudden death. Certain medications, electrolyte imbalances, and genetic conditions can cause QT prolongation. If you identify a prolonged QT interval, the client must be evaluated by a cardiologist before any biofeedback training that affects autonomic tone.

Clinical Tips When You Start HRV Biofeedback Training

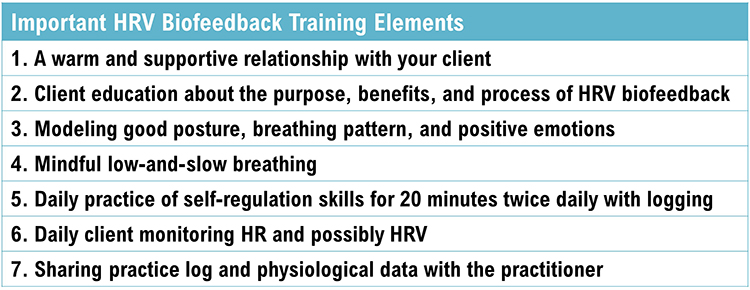

Successful HRVB training depends on numerous clinical elements working in concert. These include modeling appropriate breathing and emotional states, building a strong therapeutic relationship, cultivating passive volition, selecting appropriate monitoring equipment and displays, teaching alternatives like slow-paced contraction, detecting and addressing excessive effort, using engaging games and apps, implementing effective pacing strategies, optimizing resting heart rate, and integrating emotional self-regulation techniques.

Modeling

Clinicians are always on stage. Your breathing pattern, posture, and emotional state communicate more than your words. Model low-and-slow breathing and positive emotion throughout each session. If you are anxious, rushed, or breathing rapidly, your client will unconsciously match your state. This phenomenon, known as physiological entrainment, works both for and against you. Use it intentionally by embodying the calm, rhythmic presence you want your client to develop.

Relationship

A warm and supportive relationship with your client is the foundation for successful biofeedback training (Taub & School, 1978). From a polyvagal theory perspective, the therapeutic relationship creates a neuroception of safety that enables the ventral vagal complex to come online. In plain language: clients cannot learn to activate their parasympathetic nervous system while feeling unsafe. Your relationship provides the secure base from which they can explore alternatives to fight-or-flight, freezing, or parasympathetic withdrawal.

Passive Volition

Encourage an attitude of passive volition, characterized by allowing rather than forcing, effortlessness rather than striving. Clients often describe this state as "my body breathing itself." This passive attitude is crucial because active effort triggers sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation, which reduces vagal tone and promotes overbreathing. The harder clients try, the worse their results become. Help them understand that HRV biofeedback rewards letting go, not pushing harder.

Monitoring HRV

Your choice of sensor affects both accuracy and client comfort. For clinical work, consider an ECG sensor with wrist placement or a photoplethysmograph (PPG) sensor on an earlobe or finger. PPG sensors, which measure blood volume changes optically, trade some accuracy for ease of application. This tradeoff is acceptable for most clinical training.

However, certain conditions require ECG monitoring. When significant vasoconstriction occurs due to cold ambient temperature, stress, or physical activity, PPG signals degrade substantially. Movement artifacts also affect PPG more than ECG. If your client will be standing, moving, or training in challenging conditions, ECG provides more reliable data (Constant et al., 1999; Hemon & Phillips, 2016; Jan et al., 2019; Medeiros et al., 2011).

Selecting an Effective Display

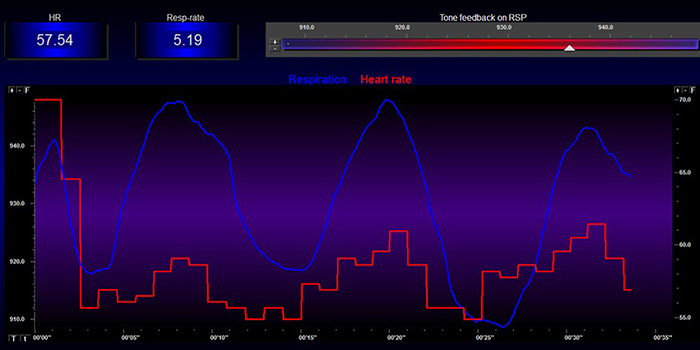

The feedback display shapes what clients learn. Provide an HRV training screen showing both respirometer and instantaneous HR waveforms. Analog displays convey incredibly detailed and intuitive information that digital numbers cannot match. Encourage your client to focus on increasing peak-to-trough swings in heart rate during each breathing cycle (Lehrer et al., 2013; Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014). When they see their heart rate rise with inhalation and fall with exhalation, the abstract concept of RSA becomes viscerally real.

While client preference and success should guide your selection, consider starting with feedback of LF power and peak-to-trough differences. These metrics respond quickly to breathing changes and provide clear, motivating feedback.

Low-Frequency Training By Dr. Khazan

Dr. Inna Khazan demonstrates how slow-paced and normal breathing change low- and high-frequency power in this video. Notice how the spectral distribution shifts dramatically when breathing slows to resonance frequency.

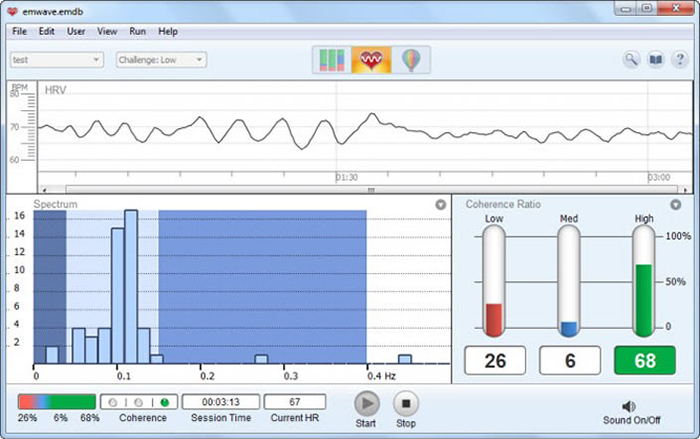

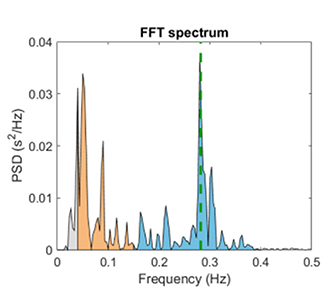

The concentration of signal power around 0.1 Hz in the LF band corresponds to the Institute of HeartMath's concept of coherence. This state produces a "narrow, high-amplitude, easily visualized peak" between 0.09 and 0.14 Hz (Ginsberg, Berry, & Powell, 2010, p. 54; McCraty et al., 2009). The term "coherence" captures both the mathematical property of the signal and the subjective experience of alignment between heart, mind, and emotion.

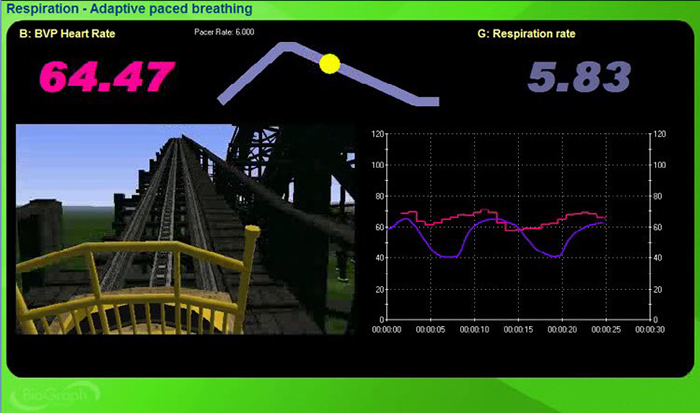

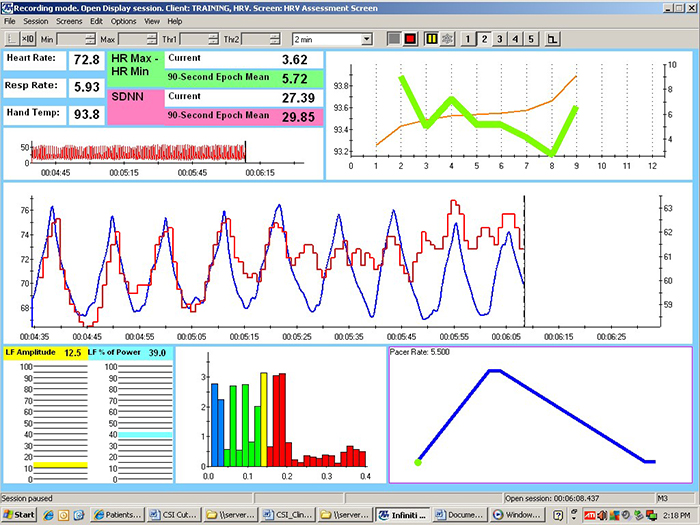

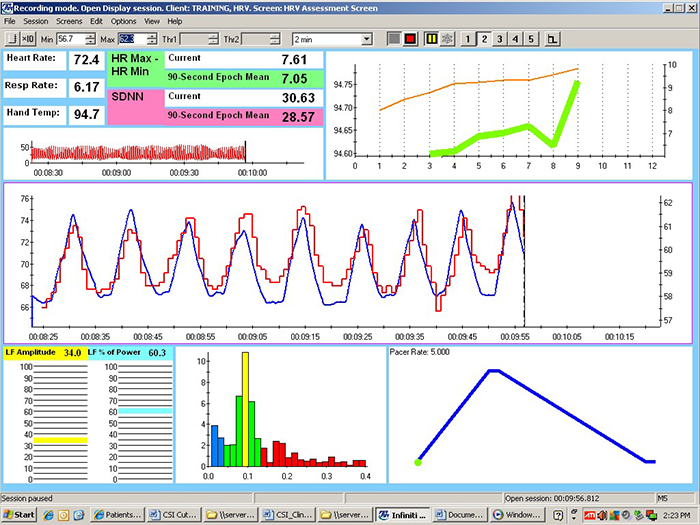

The BioGraph Infiniti screen shown below is designed to increase the percentage of power in the LF band. This three-dimensional display shows the dynamic change in HRV amplitude distribution as a client breathes effortlessly and cultivates positive emotion. Watching power concentrate at 0.1 Hz provides compelling feedback that motivates continued practice.

Some clients prefer displays showing synchrony, the alignment of peaks and troughs between respirometer and instantaneous HR signals. Synchrony matters because it amplifies the resonance effects of slow-paced breathing (Vaschillo et al., 2002). When respiration and heart rate oscillate together in phase, the baroreceptor reflex receives maximum stimulation. The NeXus-10 BioTrace+ screen below displays synchrony between respiration and heart rate. The flower opens as alignment increases, providing intuitive visual feedback.

Teach Slow-Paced Contraction Along With Slow-Paced Breathing

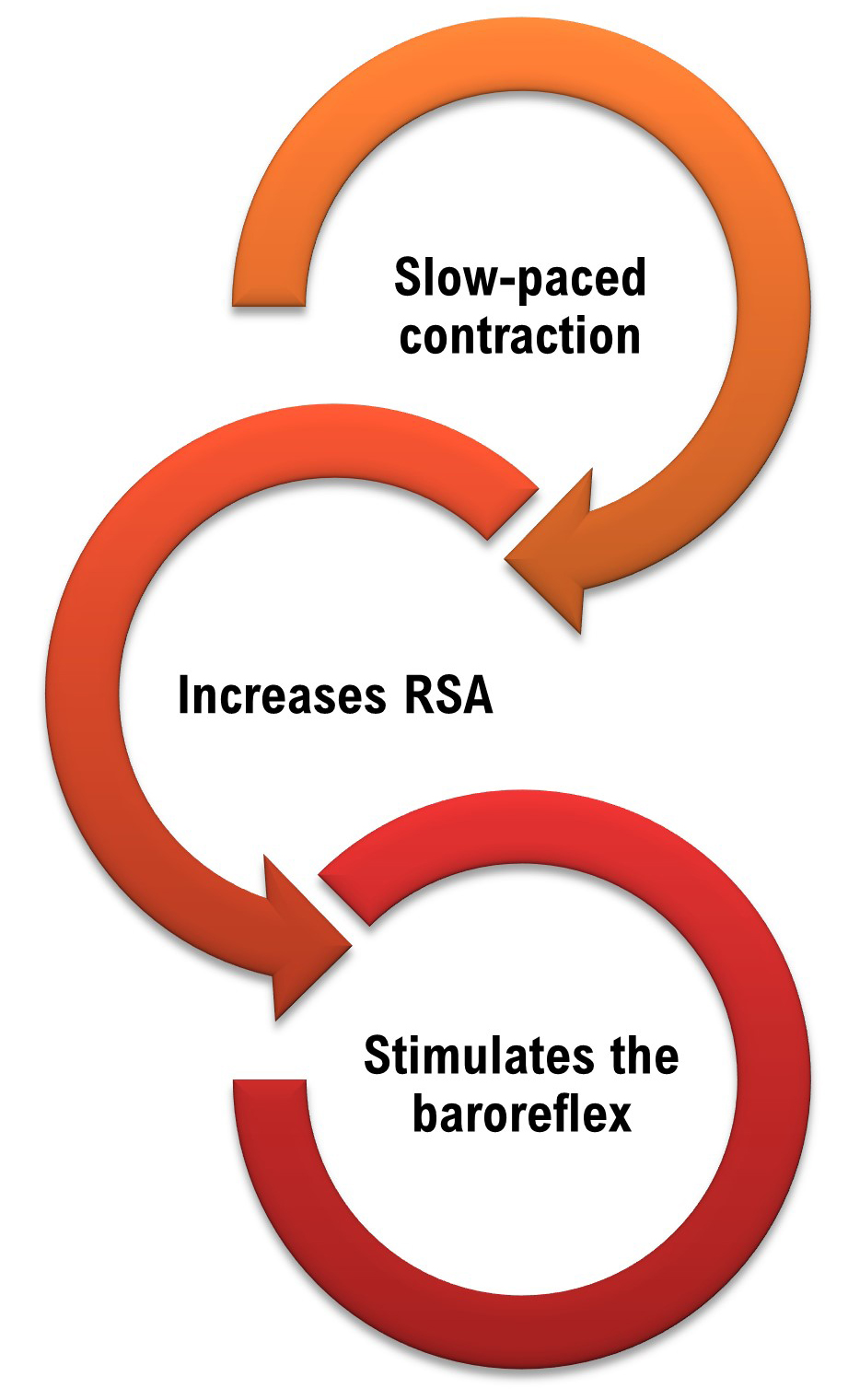

Slow-paced contraction (SPC) offers an alternative pathway to resonance frequency stimulation. Some clients find slow-paced breathing challenging, whether due to chronic pain, respiratory conditions, or simply psychological resistance to breathing exercises. Others have medical contraindications for deliberate breathing modification, such as kidney disease with metabolic acidosis, where slowing respiration could dangerously alter acid-base balance.

SPC may also benefit clients who breathe dysfunctionally and cannot slow their breathing to the adult resonance frequency range of 4.5 to 6.5 bpm without significant distress. By focusing on muscle contraction rather than breathing, these clients can access resonance frequency benefits while their breathing naturally entrains to the rhythm.

In SPC exercises, clients briefly contract and relax skeletal muscles at the same 4.5 to 6.5 cycles per minute (cpm) rates used in breathing exercises while allowing their respiration to occur naturally. The muscles involved are the wrists and ankles, or wrists, core, and ankles together. For a 6-cpm protocol, a display prompts contraction for 4 seconds followed by relaxation for 6 seconds. Contraction force should be moderate rather than maximal to ensure smooth rhythm and minimize fatigue.

The video below demonstrates 6-cpm SPC. Observe the recruitment of core muscles, including the rectus abdominis, during the contraction phase.

This second video shows 6-cpm SPC with an interesting finding: the model was not given breathing instructions, yet the SPC naturally entrained breathing rhythm. This entrainment effect makes SPC particularly valuable for clients who struggle with deliberate breath control.

Like slow-paced breathing, continuous rhythmic muscle contraction generates large heart rate oscillations and stimulates the baroreceptor reflex to increase heart rate variability. The mechanism differs, but the outcome is equivalent.

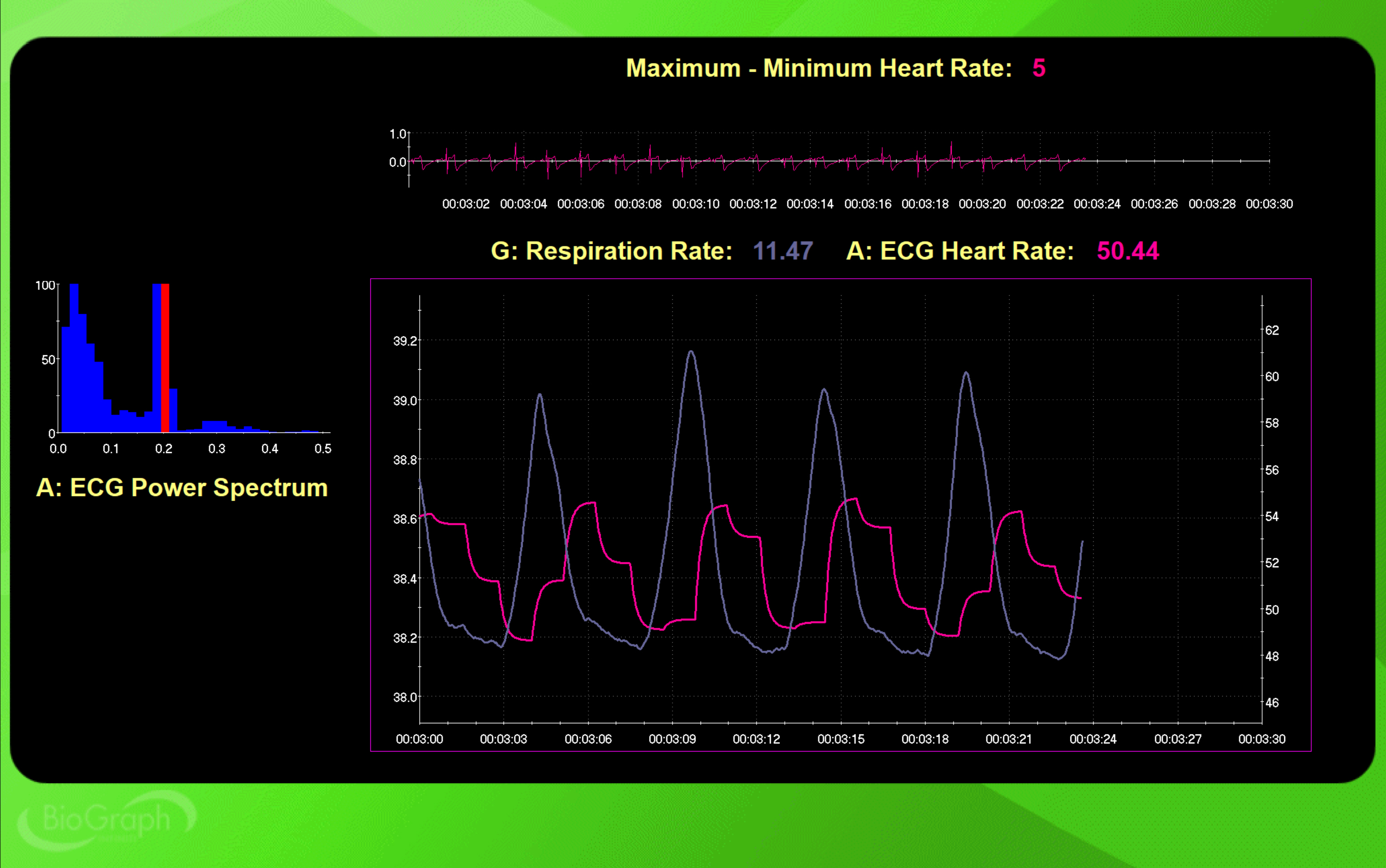

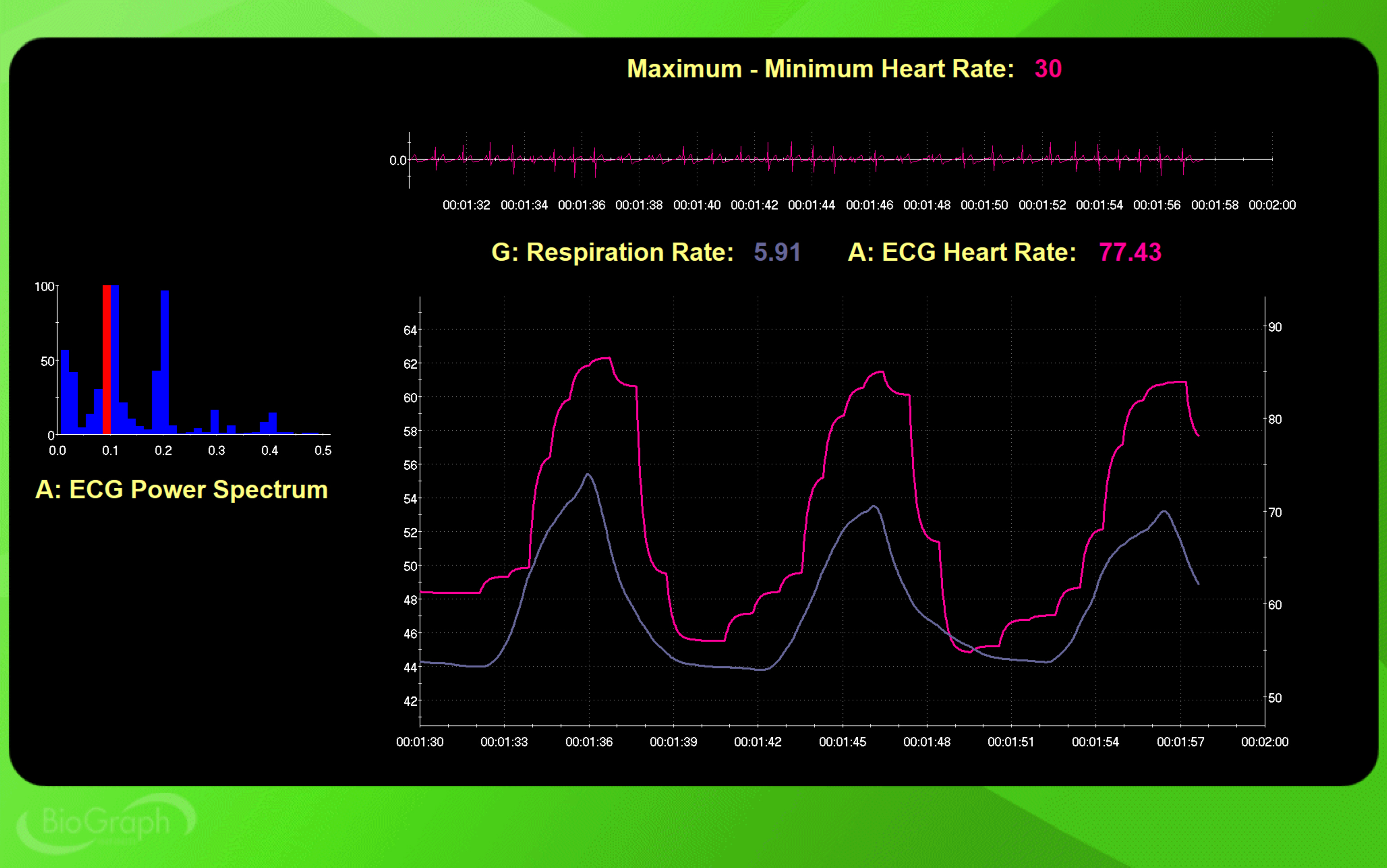

Maximum-minus-Minimum heart rate for each cycle provides an index of RSA. The peak frequency indicates the HRV frequency with greatest power. In the screen captures below, SPC stimulated the baroreceptor reflex at the intended frequency: 0.2 Hz for 12 cpm and 0.1 Hz for 6 cpm.

This BioGraph Infiniti display shows 12-cpm SPC. At the top right, the Maximum minus Minimum heart rate for each cycle is 5 bpm. At the left, the peak frequency is 0.2 Hz, exactly as expected from the 12-cpm rate.

Compare this to 6-cpm SPC. The Maximum minus Minimum heart rate for each cycle is now 30 bpm, six times greater than at 12 cpm. The peak frequency has shifted to 0.1 Hz. This dramatic increase in RSA demonstrates why resonance frequency training is so powerful.

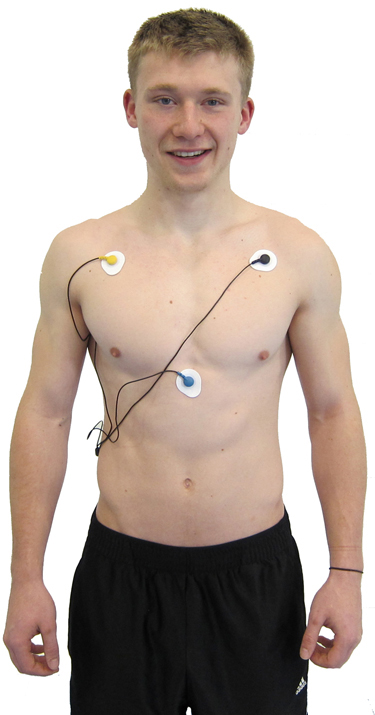

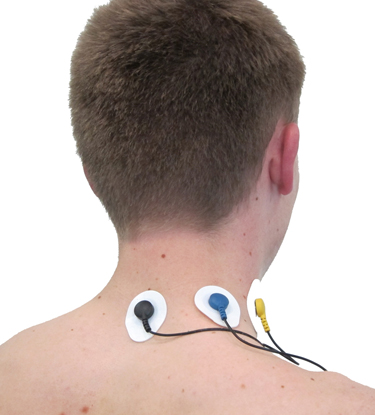

For SPC training, choose an ECG sensor using a chest or upper torso placement as shown below.

.jpg)

Alternatively, select a PPG sensor attached to an earlobe, which provides convenience without the muscle artifact that can affect wrist placement during SPC.

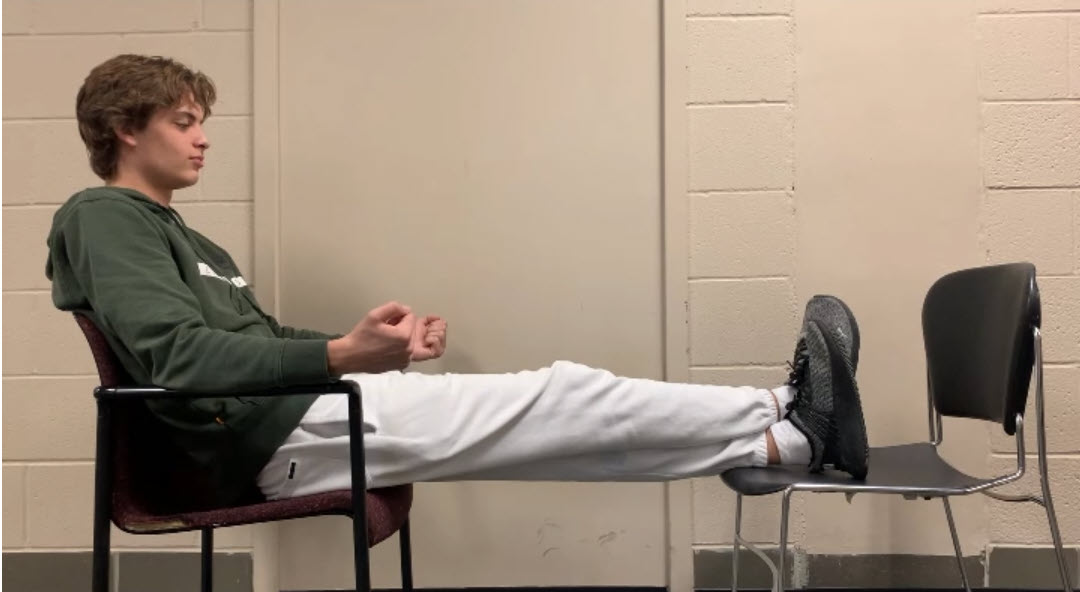

For the training position, have your client recline with feet supported by a chair. They rhythmically contract their hands, core, and feet for approximately 3 seconds at their resonance frequency (Vaschillo et al., 2011). Although the original Vaschillo protocol contracted only wrists and ankles with legs uncrossed, clinical experience has shown greater RSA using wrist, core, and crossed-ankle contraction as demonstrated below.

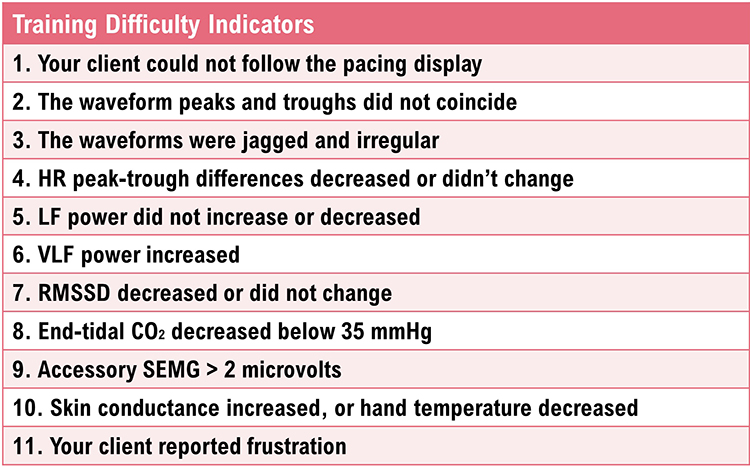

Monitoring Excessive Effort

Excessive effort, or active volition, during HRVB training undermines the very goals clients are trying to achieve. When clients try too hard, they increase SNS activation, reduce vagal tone, and promote overbreathing. The paradox of biofeedback is that striving sabotages success. Your role as clinician is to detect effort early and redirect clients toward the passive, allowing attitude that produces optimal results.

Fortunately, effort leaves clear physiological signatures that you can monitor in real time. The four primary indicators are respirometer waveform irregularities, changes in HR and HRV, accessory muscle SEMG activity, and capnometer readings.

Respirometer

Breathing effort disrupts the smooth, wavelike pattern that characterizes effortless respiration. Look for inflection points, sudden changes in the slope of the breathing waveform that indicate muscular forcing. A smooth sine wave suggests flow; a jagged waveform with sharp corners suggests struggle.

HR and HRV

When training effort produces vagal withdrawal, the reduction of parasympathetic activity, heart rate typically increases and HRV decreases. Simultaneously, very-low-frequency (VLF) band power may rise, reflecting sympathetic activation and metabolic processes associated with stress. In the FFT spectral plot, VLF power appears in gray. If you see rising VLF during training, consider whether your client is working too hard.

Accessory Muscle SEMG

Surface electromyography can detect overuse of breathing accessory muscles, including the sternocleidomastoid, scalenes, pectoralis major and minor, serratus anterior, and latissimus dorsi. These muscles assist respiration during exercise or respiratory distress but should remain relatively quiet during relaxed diaphragmatic breathing. A trapezius-scalene placement, with active SEMG electrodes on the upper trapezius and scalene muscles, provides a window into respiratory effort. Activity above 2 microvolts during slow breathing suggests excessive effort.

This BioGraph Infiniti screen provides respiratory and SEMG biofeedback simultaneously, teaching rhythmic breathing while maintaining relaxed accessory muscles. Note the elevated SEMG activity during clavicular breathing, which relies heavily on accessory muscles rather than the diaphragm.

Capnometer

Excessive breathing effort that expels too much carbon dioxide decreases end-tidal CO2 readings. A capnometer monitors CO2 concentration in exhaled air by measuring infrared light absorption. When clients overbreathe, their end-tidal CO2 drops below the normal range of 35-45 mmHg (or torr, named after Torricelli, representing the unit of atmospheric pressure equal to 1 millimeter of mercury). In the tracing below, note the disrupted capnometer waveform between 3:20 and 5:00, indicating a period of overbreathing.

Engaging Games and Apps

Once your client has mastered slow-paced breathing, games can transform practice from duty into pleasure. The gamification of HRV biofeedback serves two purposes: it motivates sustained practice and it tests the robustness of self-regulation skills under challenge. Biofeedback software allows clients to increase game difficulty progressively, developing the capacity to maintain regulation even when challenged. This graduated exposure is crucial for transferring skills to the unpredictable demands of everyday life.

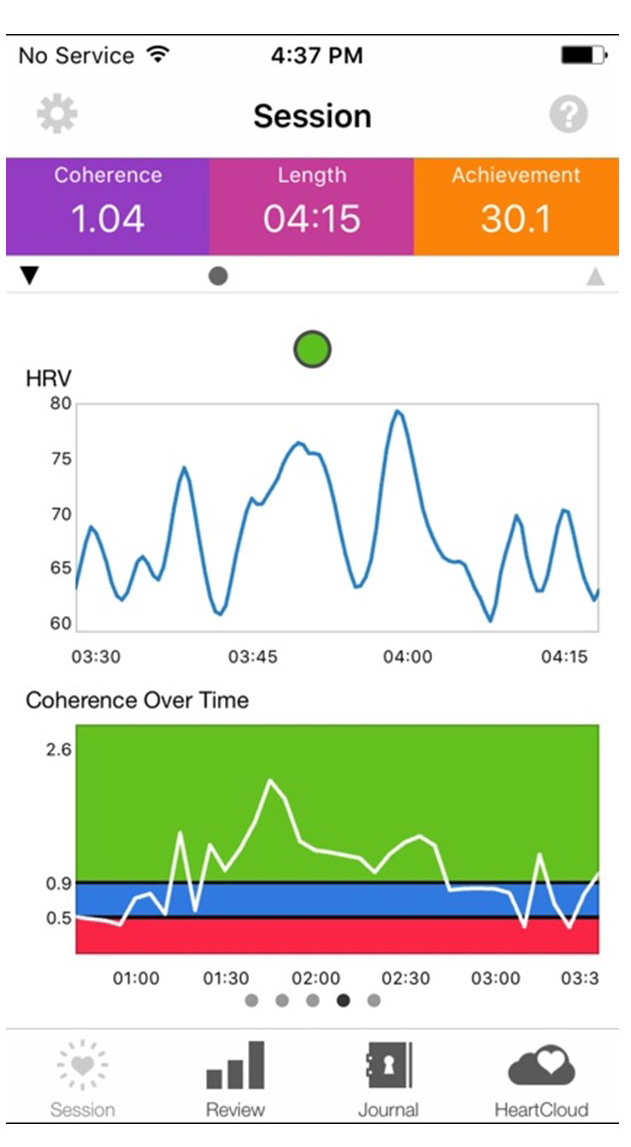

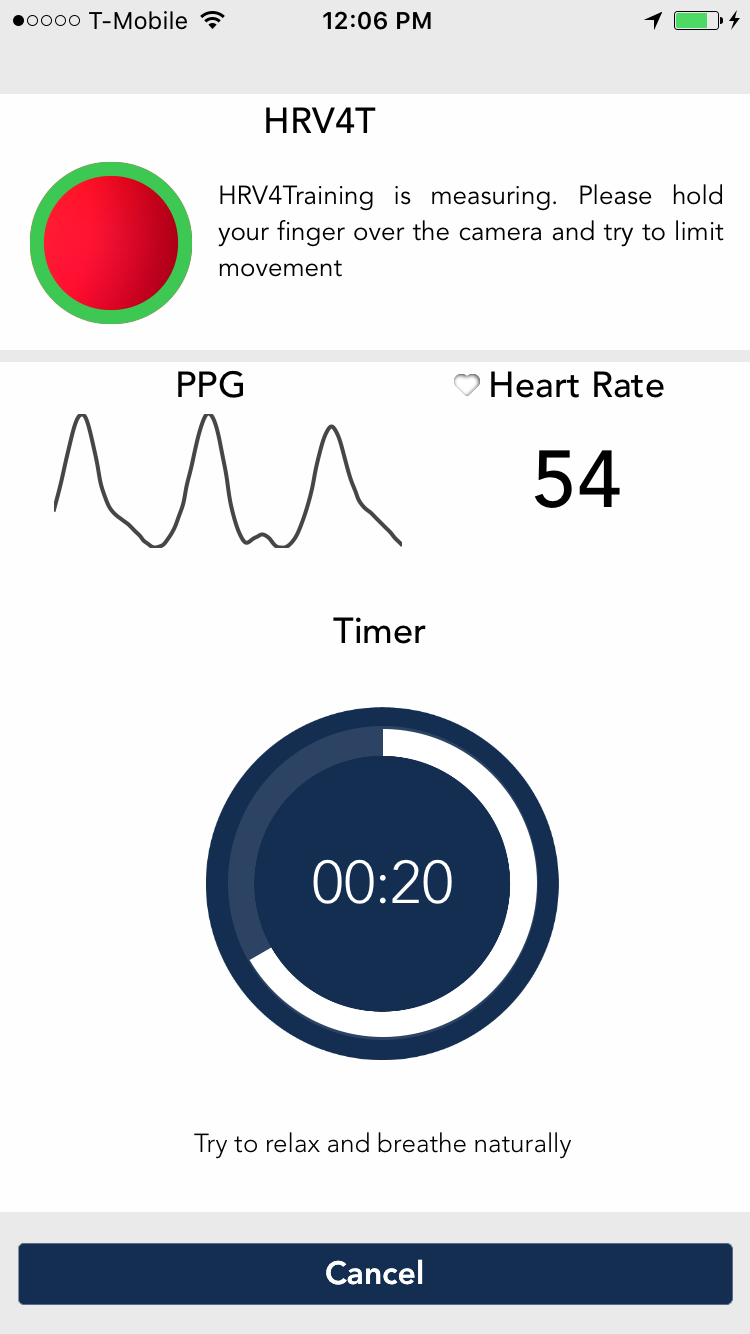

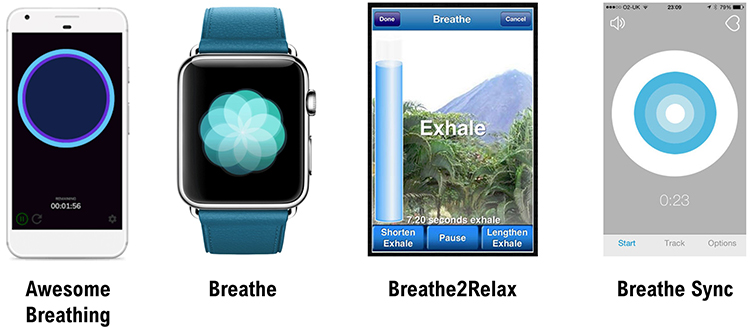

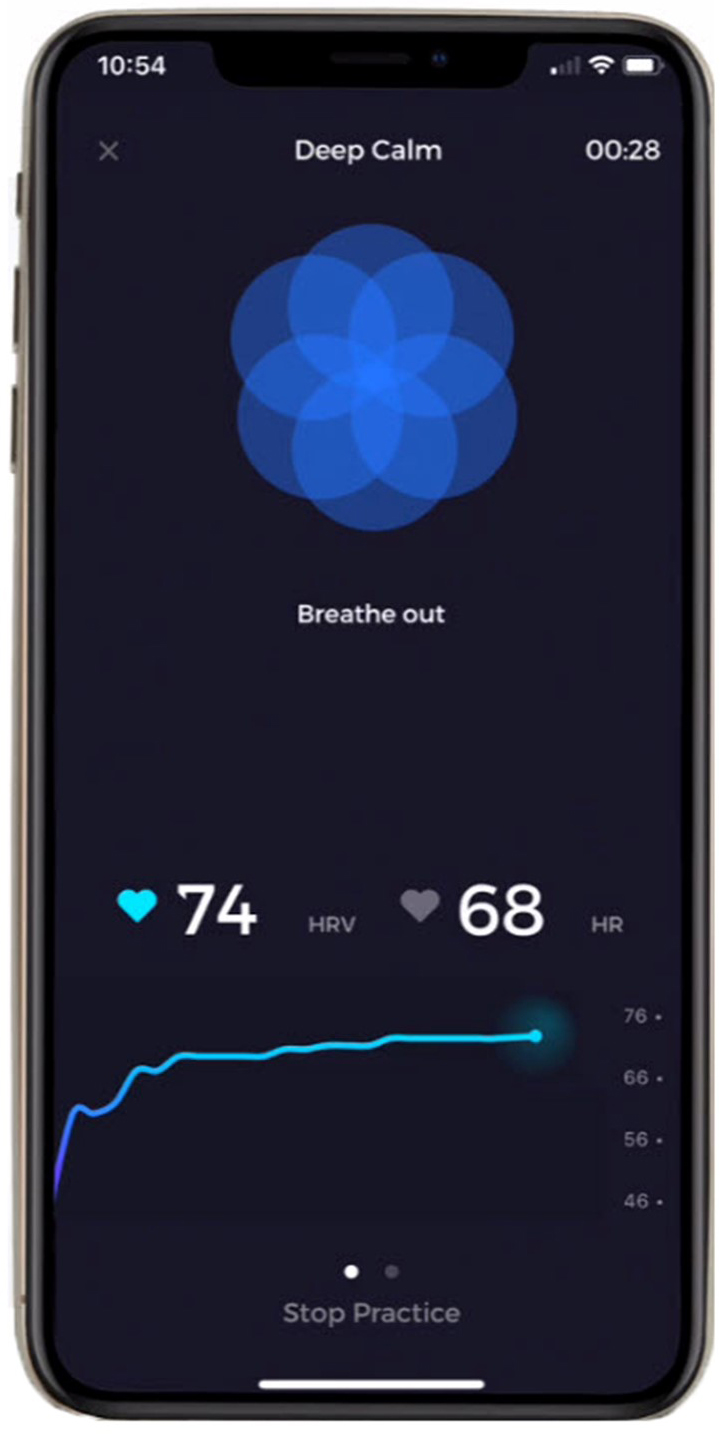

The market offers diverse options for HRV biofeedback games and apps. Professional software packages like Zukor's Drive and Zukor's Sport provide engaging visual feedback for clinic use. The HeartMath Garden Game and BioGraph Infiniti offer additional clinic-based options. For home practice, mobile apps including Inner Balance, Elite HRV, HRV4 Training, and Camera HRV enable convenient daily training.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pacing Displays

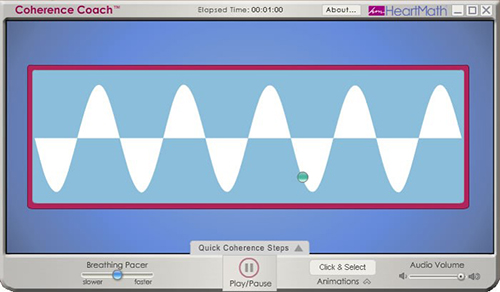

Pacers guide breathing and slow-paced muscle tension using animation and sound. Software may integrate a pacer directly into an HRVB display or provide it as a standalone tool. The clinical strategy is straightforward: assign practice with breathing pacers initially, then gradually fade them as clients internalize the rhythm. The goal is autonomous self-regulation, not dependence on external pacing.

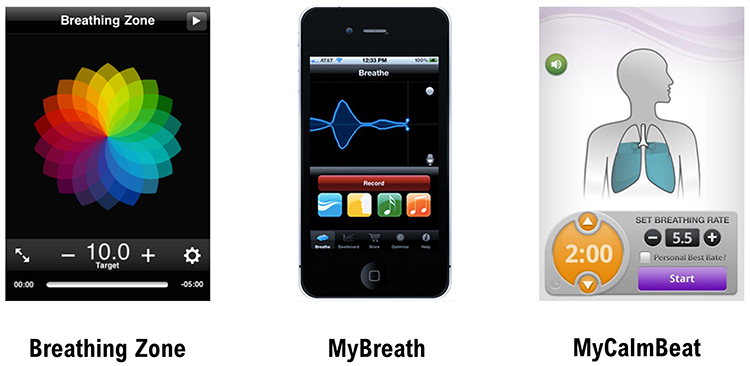

Computer, tablet, and smartphone apps offer various pacing options with different features. Try several to find apps that offer the adjustability and ease of use that best match your clients' needs. For computer-based pacing, Coherence Coach and EZ-Air Plus provide reliable options.

|

|

These mobile apps are available for both Android and Apple platforms, making practice accessible wherever clients go.

Auditory Pacing

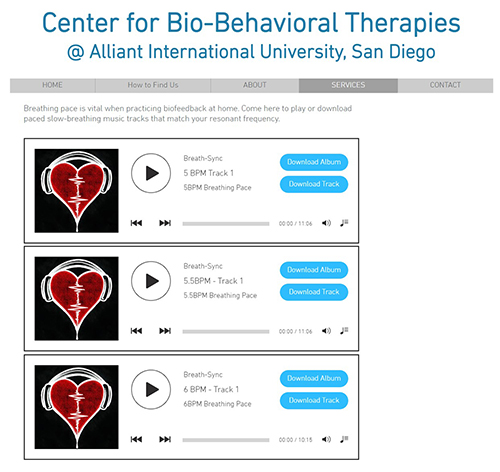

Some clients prefer auditory rather than visual pacing, finding it easier to close their eyes and follow sound cues. The Alliant International University link provides downloadable auditory pacing resources at various breathing rates.

Stopwatch Pacer

For slow-paced contraction training, a simple stopwatch app that continuously loops can serve as an effective pacer. For 6 contractions per minute, select 10 seconds with no pause. Instruct your client to simultaneously contract their hands and feet for the first 3 seconds of each cycle, then relax for the remaining 7 seconds. This low-tech solution works surprisingly well.

Resting HR

Elevated resting heart rate can limit HRVB training success by reducing the dynamic range available for heart rate oscillation. One modifiable factor is hydration status. Encourage your clients to drink sufficient water, as hypohydration increases heart rate and reduces HRV (Carter et al., 2005; Watso & Farquhar, 2019). This simple intervention can meaningfully improve training outcomes.

Caffeine presents a more nuanced picture. Although it is a central nervous system stimulant, research suggests that neither acute nor chronic caffeine intake significantly affects heart rate or HRV in healthy individuals (de Oliveira et al., 2017; Vansickle et al., 2020). You need not require clients to abstain from their morning coffee before training sessions, though monitoring individual responses remains sensible.

Emotional Self-Regulation

Breathing techniques alone tell only part of the story. Emotional self-regulation strategies can teach your clients to cultivate appreciation, heartfelt positive emotion, and resilience. These psychological skills complement the physiological training, creating a more complete intervention. The Institute of HeartMath's Lock-In Technique represents one well-validated approach, which we will describe in detail in the Practice Assignments section.

Comprehension Questions: Clinical Tips

- Why is passive volition important during HRV biofeedback training, and what happens when clients use too much effort?

- What are the four physiological indicators that clinicians can monitor to detect excessive effort during training?

- For which types of clients might slow-paced contraction be preferable to slow-paced breathing?

- How might hydration status affect HRV biofeedback training outcomes?

- What role does the therapeutic relationship play in HRV biofeedback, according to polyvagal theory?

HRV Biofeedback Training

Overview

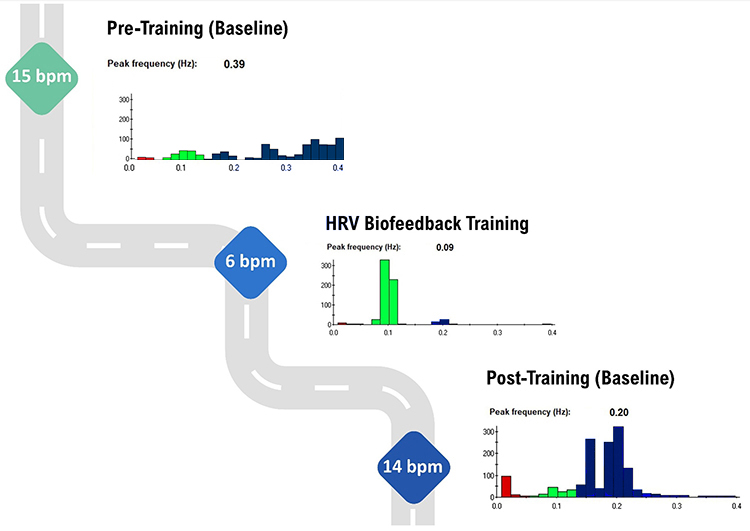

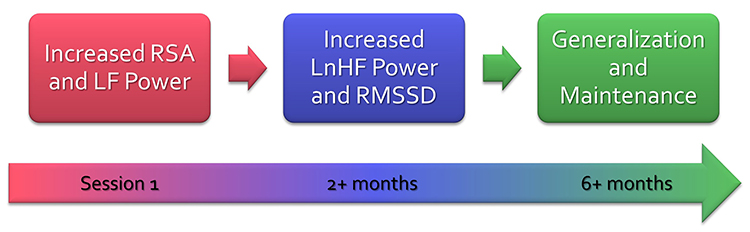

Clients often experience measurable improvements during their very first training session, demonstrating increased RSA and improved HRV time- and frequency-domain measurements. After approximately four 30-minute sessions, many clients have corrected dysfunctional breathing patterns and show increased vagal tone and HRV. However, achieving maximum health and performance gains typically requires extended training of ten or more sessions combined with consistent home practice (Lagos et al., 2011).

This section covers the essential elements of training: session structure, resting baseline measurements, selecting initial respiration rates, introducing training to clients, recognizing success and difficulty indicators, reviewing training segments, promoting mindful breathing, conducting session reviews, comparing pre- and post-session values, key training elements, and determining how many sessions are needed.

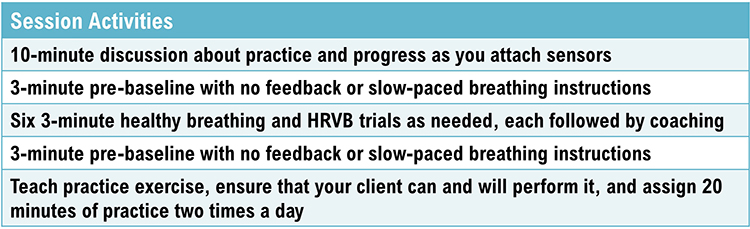

Session Structure

A well-organized session flows through three phases: pre-baseline measurement, active training, and post-baseline measurement. This structure serves both clinical and motivational purposes. By bracketing training with baseline measurements, you create clear before-and-after comparisons that document learning and motivate continued practice.

Resting Pre- and Post-Baseline Measurements

Resting baselines capture your clients' psychophysiological activity without feedback or paced breathing. Instructions should be minimal and neutral: "Please sit quietly and breathe normally for the next few minutes." Depending on your clinical goals, you might monitor HRV, breathing parameters including depth, pattern, and rate, autonomic indicators such as skin conductance and temperature, blood pressure, and end-tidal CO2.

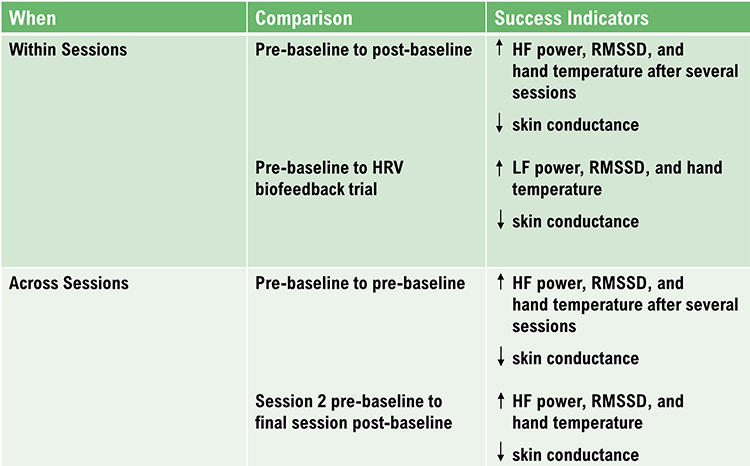

The comparison between pre-baseline and post-baseline values within a single session demonstrates within-session learning. Even more valuable is tracking pre-baseline changes across sessions, which reveals the combined effect of clinic training and home practice. A client whose pre-baseline HRV improves from session to session is integrating the skills into daily life.

During baselines, clients breathe at typical rates of approximately 12-16 bpm, so do not expect increases in LF power. Instead, look for increased HF power, improved HRV time-domain metrics such as RMSSD, elevated hand temperature, and reduced skin conductance level. These changes indicate genuine improvements in vagal tone and autonomic regulation.

We train clients to increase LF power during slow-paced breathing to increase HF power during baselines when they breathe at typical rates.

How to Select a Starting Respiration Rate

Select an initial respiration rate for the animated pacing display based on your client's determined resonance frequency. However, shaping is crucial to client motivation and success. Rather than jumping immediately to the RF, choose a starting respiration rate within 1 or 2 breaths per minute of the client's baseline mean. This ensures early success, building confidence before gradually shifting toward the target rate.

Training Introduction

How you introduce training shapes your client's understanding and approach. Sample instructions that have proven effective include the following:

A healthy heart is not a metronome. As you inhale, your heart rate speeds, and as you exhale, your heart rate slows. This rhythmic speeding and slowing of your heart produces heart rate variability, which is vital to your health, performance, and resilience against stressors. The purpose of heart rate variability biofeedback training is to teach you to increase the healthy speeding and slowing of your heart by breathing effortlessly at the rate that is best for you and by increasing your ability to experience positive emotions like feelings of appreciation and gratitude.

Adopt a passive attitude in which you trust your body to breathe itself. Allow your attention to settle on your waist. Let your exhalation continue until your body initiates your next breath. Your inhalations should be no deeper than if you were smelling a flower. Allow your breathing to follow the yellow ball effortlessly.

Allow your stomach to gradually plop out as you inhale and then slowly draw inward as you exhale. As you practice, we will adjust the speed of the pacing display. Let it guide your inhalation and exhalation. Allow your stomach to gradually plop out as you inhale and then slowly draw inward as you exhale.

The computer can help you learn slow, effortless breathing. The pink tracing shows your heart rate, while the violet tracing shows the movement of the sensor around your stomach. As you gradually learn low-and-slow breathing, the two tracings should resemble smooth, repeating ocean waves.

After providing instructions, start recording data for a 3-minute training segment. At the end of each segment, engage the client in reflection: "How was the speed of the pacing display? Should we change it? Should we adjust the inhalation and exhalation lengths? What did you experience as you practiced breathing effortlessly?" These questions promote mindfulness and collaborative adjustment.

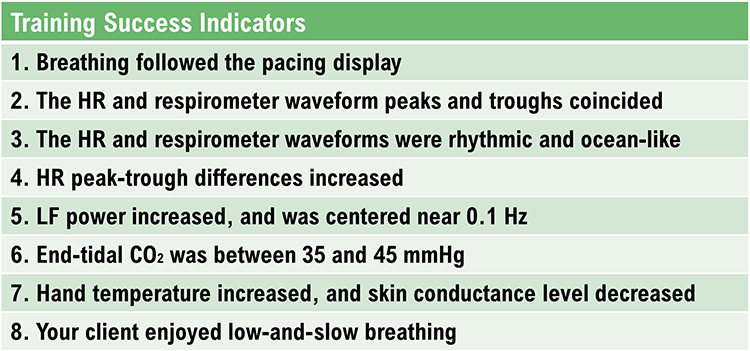

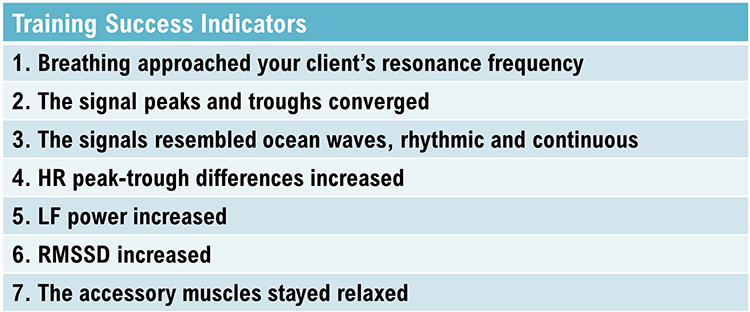

Training Success Indicators

Several signs indicate that training is proceeding well. Look for smooth, wavelike tracings in both respiration and heart rate signals. The peaks and troughs of these waveforms should align, indicating synchrony. Peak-to-trough heart rate differences should increase as the session progresses. The client should appear relaxed and report a sense of calm or ease.

Training Difficulty Indicators

Equally important is recognizing when clients struggle. Warning signs include jagged, irregular waveforms with frequent inflection points. Misalignment between respiration and heart rate tracings suggests poor synchrony. Decreasing or stagnant peak-to-trough differences indicate the client may be working too hard or breathing at the wrong rate. Physical signs of tension or client reports of frustration or discomfort warrant immediate attention.

Training Segment Review

After each 3-minute segment, fit the entire recording on one screen and review it collaboratively with your client. If they succeeded, point out specific moments of success: "See how smooth your breathing became here? And notice how your heart rate started matching your breath in this section." Concrete positive feedback builds confidence and clarifies what success looks and feels like.

Promote Mindful Breathing

Before starting the next segment, engage the client's curiosity about their own physiology. Ask questions like: "What were you doing when the display became wavelike and regular? What happened when the display became more jagged and irregular?" If accessory SEMG exceeded 2 microvolts, show this on the display, ask whether they noticed heightened breathing effort, and encourage them to "let your shoulders relax and allow yourself to breathe."

Reassure clients that choppy tracings are normal at the start of training. The waveforms will gradually become more wavelike as breathing becomes more rhythmic and regular. Rather than overwhelming clients with corrections, ask them to experiment with one or two changes at a time. For example: "Effortless breathing is rhythmic like ocean waves. Allow your stomach to gently expand and contract as you follow the pacing display."

Session Review

After your client has completed six 3-minute training segments, conduct a 3-minute post-baseline recording without feedback. Following this final baseline, ask your client how they felt and what they learned during the session. Display the entire session on one screen, highlighting moments of success and areas that need continued work. This comprehensive review helps clients understand their trajectory and sets expectations for future sessions.

Comparing Pre- and Post-Session Values

Without pacing or feedback, your client will breathe at typical rates during both baselines. The meaningful comparisons between pre- and post-baseline involve metrics that reflect vagal tone at normal breathing rates: HF power, RMSSD, and hand temperature should increase, while skin conductance level should decrease.

The graphic below shows HF power (in blue) during a pre-training baseline, HRVB training, and a post-training baseline. On the y-axis, power in each band is displayed in absolute units. HF power increases from approximately 100 μV during the pre-training baseline to approximately 300 μV during the post-training baseline. This threefold increase indicates meaningfully enhanced vagal tone.

Also note the greater LF power concentration in the post-training baseline compared with pre-training, even though the client breathed at typical rates in both baselines. This carryover effect demonstrates that resonance frequency training benefits persist beyond the training itself. These spectral plots were generously provided by Inna Khazan.

HRV Biofeedback Training Elements

Effective training integrates multiple elements working together. These include appropriate sensor selection, engaging feedback displays, individualized breathing rates based on resonance frequency assessment, a supportive therapeutic relationship, passive volition and effortlessness, mindful attention to body sensations, integration of positive emotion, and consistent home practice.

How Many HRVB Sessions Are Required?

Many clients begin to breathe more effortlessly and show increased HRV during their very first training session. However, there is typically a several-week lag between increased HRV during training and improved health or performance in daily life. Clients require this time to consolidate their learning and transfer enhanced skills to the diverse settings of their lives.

Practice is the bridge between the clinic and everyday life. Without consistent home practice, even excellent in-clinic performance may not translate to real-world benefits.

The physiological changes follow a predictable timeline. Increased RSA immediately exercises the baroreflex without necessarily changing baseline vagal tone or improving blood pressure regulation. Those deeper adaptations require months of consistent practice (Gevirtz, Lehrer, & Schwartz, 2016; Lagos et al., 2011). Think of it like exercise: a single workout feels good, but cardiovascular fitness develops over months of training.

Comprehension Questions: Training Sessions

- Why should clinicians measure both pre- and post-baseline values during HRV biofeedback sessions?

- What HRV changes would you expect to see during pre- and post-baselines (when clients breathe at typical rates) versus during paced breathing training?

- How should you select a starting respiration rate for a new client?

- What questions can you ask between training segments to promote mindful breathing?

- Why is there often a lag between initial HRV improvements and measurable health or performance gains?

Practice Assignments

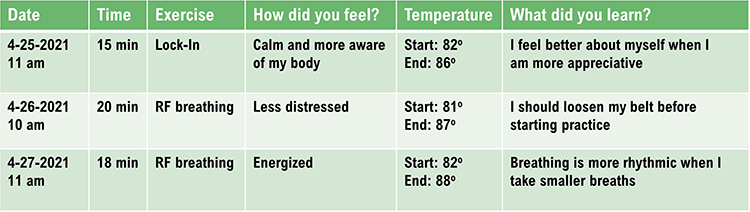

Home practice transforms clinic learning into lasting change. Encourage clients to measure their HRV while breathing at typical rates immediately after waking, when circadian influences are relatively stable. They can send weekly reports showing trends in their HRV, and products like Elite HRV and Inner Balance automate data sharing between clients and clinicians.

The standard recommendation is 20 minutes of practice twice daily with HRV monitoring. After each practice session, clients can complete an online diary and share their interbeat interval data with you. Khazan (2013) provides excellent practice logs in The Clinical Handbook of Biofeedback that you can adapt for your clinical needs.

Reality often differs from recommendations. Some clients will practice diligently; others will not. You may have to settle for 10 minutes once a day or practice "as needed." Interestingly, Lehrer et al. (2020a) concluded that the frequency and length of home practice did not significantly impact effect size. The practice of resonance frequency breathing as needed may have produced most of the observed gains (p. 125). This finding suggests that even brief, strategically-timed practice can be valuable.

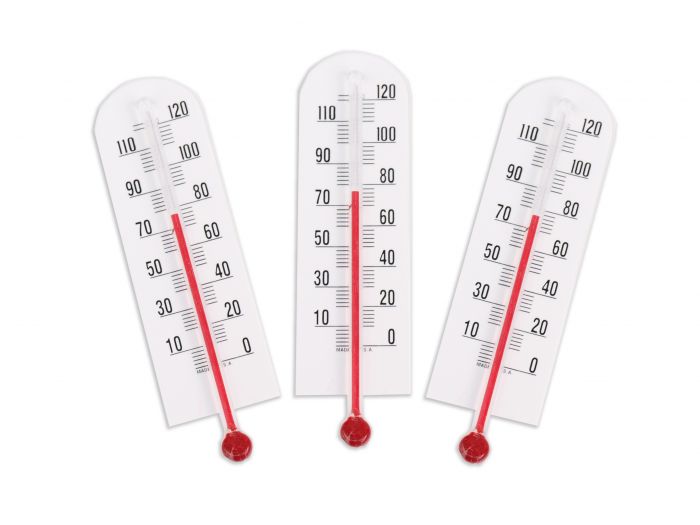

Following Gevirtz's recommendation, include starting and ending hand temperatures in practice logs, since successful HRVB practice often produces peripheral warming as sympathetic tone decreases and blood vessels dilate.

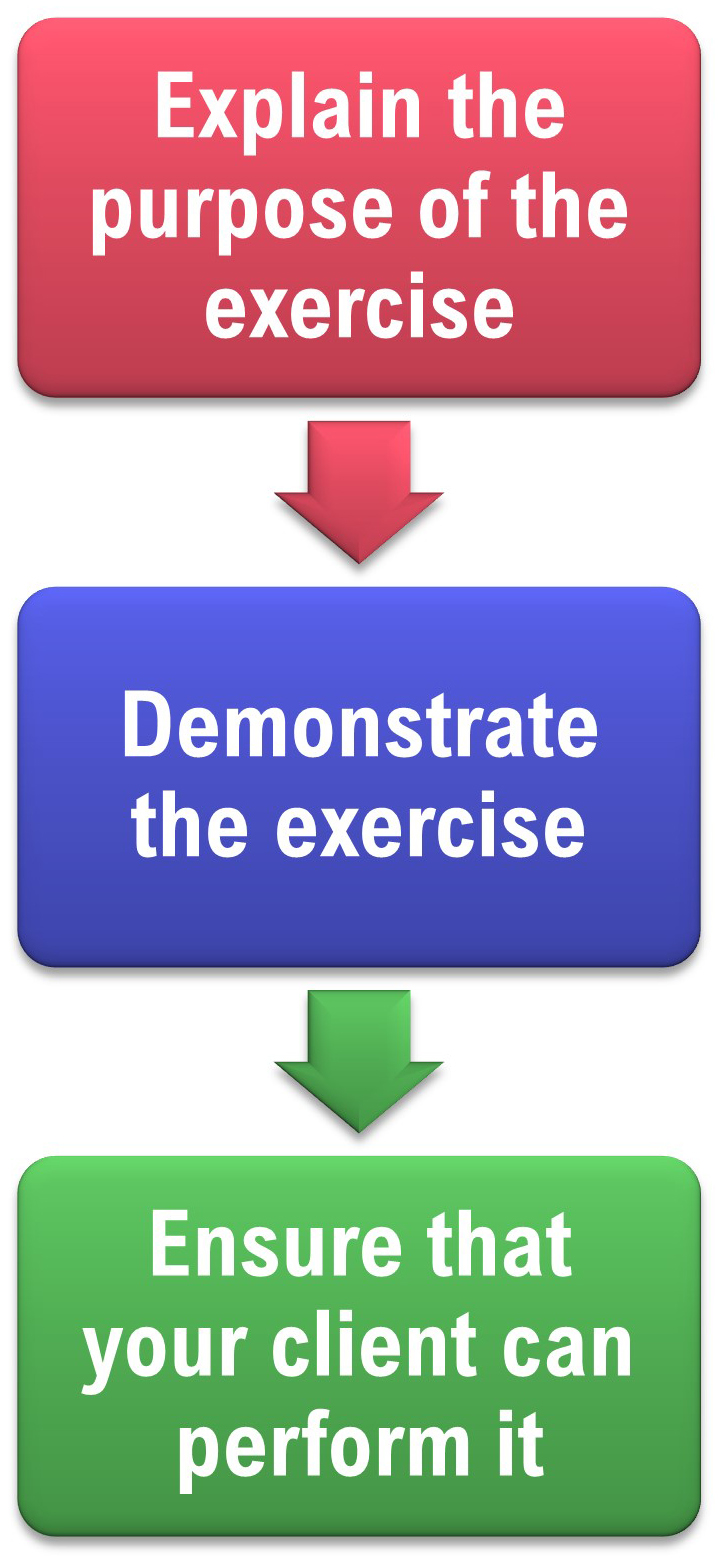

Effective practice assignment requires four steps. First, explain the purpose of the exercise so clients understand why it matters. Second, demonstrate the skill in the clinic so they can see correct technique. Third, confirm that they can correctly perform it before leaving. Fourth, secure their agreement to practice. To build a collaborative relationship and empower your clients, encourage them to find ways to improve exercises or develop alternatives that work better for their lives.

Overview

This section addresses practice in diverse settings, aerobic activity, heart rate monitoring, HRV monitoring, emotional self-regulation techniques, home HRV practice equipment, advanced HRV assessment, and finger temperature monitoring.

Practice in Diverse Settings

Encourage clients to practice resonance frequency breathing during everyday activities in diverse settings including commuting, work, and home. This varied practice promotes generalization, the ability to apply skills across different contexts. A veteran who practices only in a quiet clinic may struggle to access those skills during a stressful meeting at work. Practice in multiple environments builds robust, flexible self-regulation.

Aerobic Activity

Assign 20 minutes daily of aerobic activity, particularly for sedentary clients. Aerobic exercise produces cardiovascular adaptations that complement HRV biofeedback: it lowers resting heart rate and raises baseline HRV. These effects are additive with HRVB training, creating synergies that neither intervention achieves alone.

Monitor HR

Invite clients to monitor their heart rate during daily activities and emotional states using wearable devices. This practice increases mindfulness of stressors and physiological responses to challenges. When a client notices that checking email raises their heart rate by 15 bpm, they gain insight that motivates behavior change. Self-monitoring transforms abstract concepts into personal discoveries.

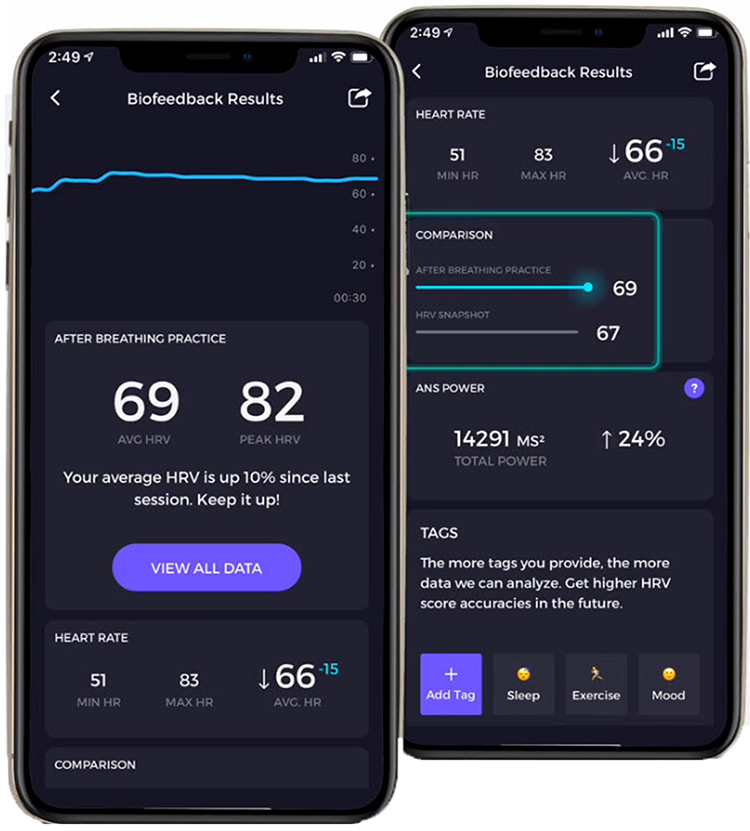

Monitor HRV

Apps like Elite HRV enable clients to take HRV snapshots with built-in artifact correction. These brief measurements, taken consistently over time, reveal patterns and progress that motivate continued practice. The data also provides valuable clinical information about how clients respond to life stressors.

Emotional Self-Regulation

Emotional self-regulation practice complements breathing training by addressing the psychological dimension of stress response. These techniques may reduce parasympathetic withdrawal, cultivate the tend-and-befriend response, and increase resilience. For many clients, emotional regulation proves as important as breathing technique.

The Institute of HeartMath's Lock-In Technique provides a structured approach to emotional self-regulation. Instructions for the technique are as follows:

Try to focus your attention on the area around your heart. Maintain your heart focus and, while breathing, imagine that your breath is flowing in and out through the heart area. Breathe casually, just a little deeper than normal.

Now try to recall a positive emotion or feeling that makes you relaxed and comfortable. Find a positive feeling like appreciation, care, joy, kindness, or compassion. You can recall a time you felt appreciation or care. This could be the appreciation or care you feel towards a special person, a pet, a place you enjoy, or an activity that was fun for you.

If you cannot feel anything, that is okay. Just try to find a sincere attitude of appreciation or care. Continue to think of this positive feeling or emotion.

Other evidence-based approaches to emotional self-regulation include Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and compassion meditation. These techniques share the goal of changing how clients relate to their emotional experiences, promoting flexibility and reducing reactivity.

Home HRV Practice

Portable HRV biofeedback devices bring the training experience home. The Institute of HeartMath's Inner Balance and similar devices allow personal training whenever clients choose, removing the constraint of clinic-only practice. This accessibility dramatically increases potential practice time and supports skill maintenance after formal treatment ends.

Advanced HRV Assessment

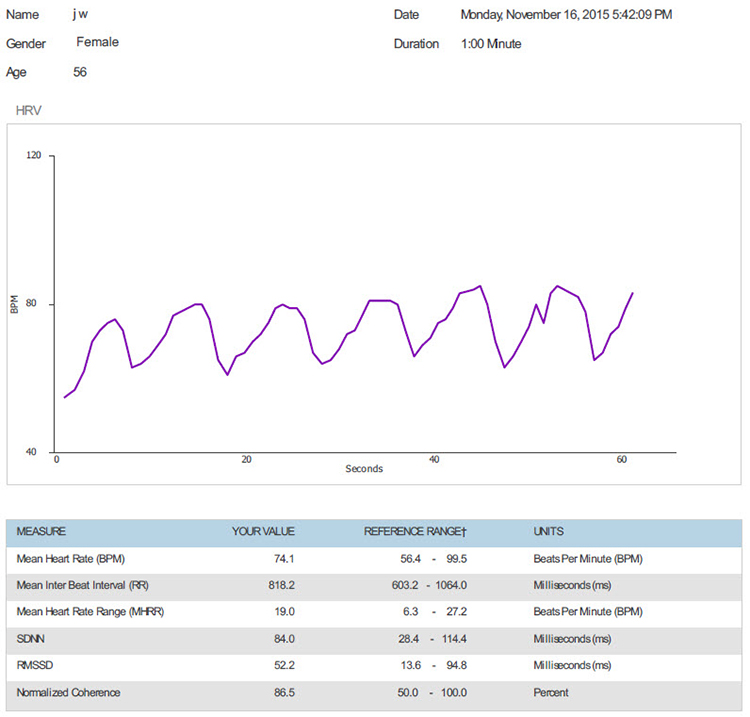

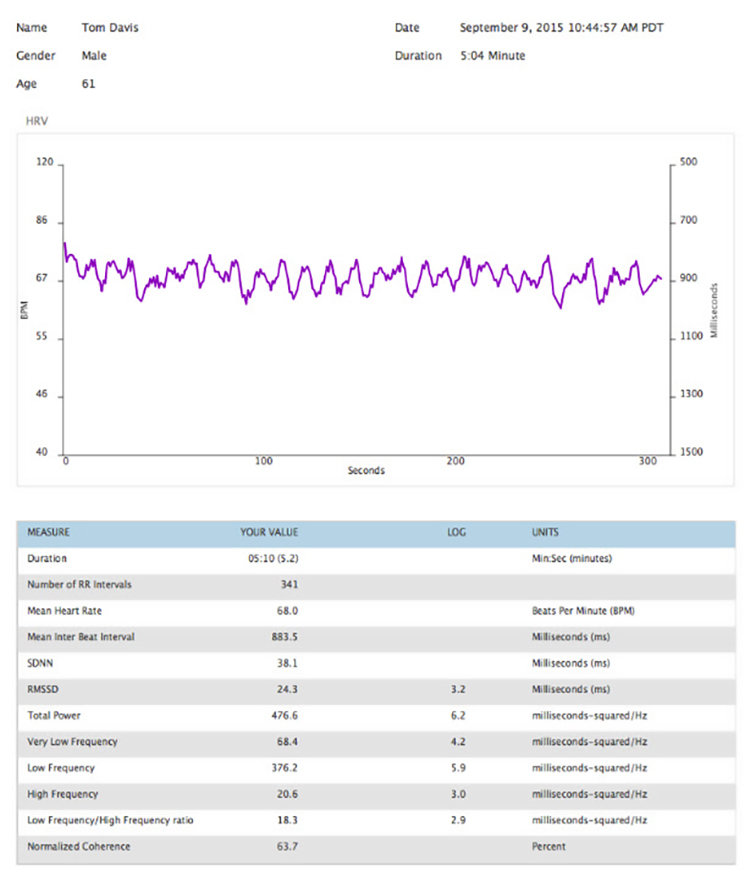

For clients who want detailed progress tracking, the Institute of HeartMath's emWave Pro Plus provides comprehensive HRV assessment using an automated deep breathing protocol. The software reports commonly used HRV metrics referenced to age-related norms, allowing clients to see how they compare to healthy populations and track their improvement over time.

The emWave Pro Plus also provides resting metrics for training sessions ranging from 1 to 99 minutes, offering flexibility for different clinical protocols and client preferences.

Monitor Finger Temperature

Encourage your clients to monitor their hand temperature using inexpensive alcohol thermometers to see whether their practice produced warming or cooling. Hand temperature provides a simple, low-tech indicator of autonomic state. Warming typically indicates reduced sympathetic activation and increased blood flow, suggesting successful practice.

HRV Myths

Dr. Inna Khazan addresses common misconceptions about HRV and HRV biofeedback in this video. Understanding these myths helps clinicians provide accurate information to clients and avoid common pitfalls in training.

Comprehension Questions: Practice and Myths

- What is the recommended frequency and duration for home HRV biofeedback practice?

- Why should clinicians encourage practice in diverse settings rather than just at home?

- What role does hand temperature monitoring play in home practice?

- How does aerobic exercise complement HRV biofeedback training?

- What is the HeartMath Lock-In Technique and how does it integrate with HRV training?

Assignment

Which of the two screens below shows better HRV performance? What is the basis for your judgment? Take a moment to examine each display carefully before reading the analysis.

Begin by checking the mean respiration rates to confirm that this client breathed around 6 breaths per minute in each session. She did. Now examine the values for HR Max minus HR Min and LF amplitude. Both were substantially higher in the second session. The greater HR Max minus HR Min is visually evident in the peak-to-trough differences, which show larger swings in the second session.

Next, look at the distribution of signal power at 0.1 Hz. In the second session, signal energy is more tightly concentrated at and around this dominant frequency, indicating better resonance. Inspect the synchrony of the HR and respirometer tracings. The peaks and valleys align more closely in the second session. Finally, compare hand temperatures. Her hands were almost 1 degree Fahrenheit warmer in the second session, indicating reduced sympathetic activation.

These recordings were from a chronic pain patient who received treatment in an interdisciplinary chronic pain program. The improvement from Session 1 to Session 2 demonstrates the kind of progress clinicians can expect with consistent training and practice.

Cutting Edge Topics

Wearable Technology and Continuous HRV Monitoring

The proliferation of wearable devices capable of continuous HRV monitoring is transforming both research and clinical practice. Devices like the Oura Ring, WHOOP strap, and Garmin watches now provide overnight and continuous HRV metrics that were previously available only in clinical settings. While these consumer devices have accuracy limitations compared to clinical-grade equipment, they offer unprecedented opportunities for longitudinal tracking and ecological momentary assessment.

Clinicians increasingly use wearable data to supplement clinic-based training. These devices reveal how clients' HRV responds to real-world stressors, sleep quality, and recovery. Continuous data streams can uncover patterns invisible in periodic clinic assessments, such as the cumulative effects of work stress or the impact of lifestyle changes on autonomic function.

Artificial Intelligence in HRV Analysis

Machine learning algorithms are being developed to detect subtle patterns in HRV data that may predict health outcomes or identify optimal training parameters. These AI systems analyze the complex, nonlinear dynamics of heart rate variability to provide personalized recommendations for breathing rates, practice timing, and intervention strategies. While still in early development, these tools promise to enhance HRV biofeedback precision by tailoring protocols to individual physiological signatures.

Virtual Reality Enhanced HRV Training

Virtual reality environments are being explored as immersive contexts for HRV biofeedback training. By placing clients in calming virtual environments such as beaches, forests, or meditation spaces while they practice resonance frequency breathing, VR may enhance the learning process and improve engagement. Early research suggests that VR-enhanced training may produce stronger initial effects, though questions remain about long-term transfer to real-world settings. For populations like veterans with PTSD, VR may also allow graduated exposure to challenging scenarios while practicing regulation skills.

Telehealth Delivery of HRV Biofeedback

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of telehealth for HRV biofeedback delivery. Clinicians discovered that many aspects of HRV training can be effectively delivered remotely using video conferencing combined with client-side PPG sensors or smartphone apps. While telehealth cannot replicate all aspects of in-person training, particularly initial sensor placement and equipment troubleshooting, it has proven valuable for follow-up sessions, practice coaching, and reaching clients in underserved areas. Research continues to establish best practices and compare outcomes between telehealth and traditional delivery, but early results are encouraging for hybrid models that combine initial in-person training with telehealth follow-up.

Glossary

accessory muscles: the sternocleidomastoid, pectoralis minor, scalene, and trapezius muscles, which are used during forceful breathing, as well as clavicular and thoracic breathing.

apnea: breath suspension.

atrial fibrillation: the most common cardiac arrhythmia involving rapid, irregular contraction of the two upper atrial chambers.

baroreceptor reflex (baroreflex): a mechanism that provides negative feedback control of BP. Elevated BP activates the baroreflex to lower BP, and low BP suppresses the baroreflex to raise blood pressure.

capnometer: an instrument that monitors the carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration in an air sample (end-tidal CO2) by measuring the absorption of infrared light.

clavicular breathing: a breathing pattern that primarily relies on the external intercostals and the accessory muscles to inflate the lungs, resulting in a more rapid respiration rate, excessive energy consumption, and incomplete ventilation of the lungs.

coherence: a narrow peak in the BVP and ECG power spectrum between 0.09 and 0.14 Hz.

diaphragm: the dome-shaped muscle whose contraction enlarges the vertical diameter of the chest cavity and accounts for about 75% of air movement into the lungs during relaxed breathing.

emotional self-regulation: the self-monitoring, initiation, maintenance, and modulation of rewarding and challenging emotions and the avoidance and reduction of high levels of negative affect.

end-tidal CO2: the percentage of CO2 in exhaled air at the end of exhalation.

frequency-domain measures of HRV: the calculation of the absolute or relative power of the HRV signal within four frequency bands.

heart rate variability (HRV): the variation in time intervals between consecutive heartbeats.

high-frequency (HF) band: the HRV frequency range from 0.15-0.40 Hz that represents the inhibition and activation of the vagus nerve by breathing (respiratory sinus arrhythmia).

interbeat interval (IBI): the time interval between the peaks of successive R-spikes (initial upward deflections in the QRS complex). This is also called the NN (normal-to-normal) interval after removing artifacts.

ischemia: insufficient blood supply to tissue, which depresses the ST segment of the ECG.

low-frequency (LF) band: the HRV frequency range of 0.04-0.15 Hz that may represent the influence of PNS and baroreflex activity when breathing at the RF.

metabolic acidosis: a pH imbalance in which the body has accumulated excessive acid and has insufficient bicarbonate to neutralize its effects. In diabetes and kidney disease, hyperventilation attempts to compensate for abnormal acid-base balance, and slower breathing could endanger health.

mindfulness: a nonjudgmental focus of attention on the present on a moment-to-moment basis.

passive volition: an attitude of allowing and effortlessness during biofeedback training, in which the body feels as if it is performing the target behavior (like breathing) by itself.

peak frequency: the HRV frequency with the greatest power.

prolonged QT interval: an extended QT interval associated with increased risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias, cardiac arrest, and sudden death.

pulse oximeter: a device that measures dissolved oxygen in the bloodstream using a photoplethysmograph sensor placed against a finger or earlobe.

QT interval: the period signaling depolarization and repolarization of the ventricles.

resilience: adapting effectively to stressors, threats, and trauma.

resonance frequency (RF): the frequency at which a system, like the cardiovascular system, can be activated or stimulated.

respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA): the rhythmic increase in heart rate during inhalation and decrease during exhalation.

reverse breathing: the abdomen expands during exhalation and contracts during inhalation, often resulting in incomplete ventilation of the lungs.

slow-paced breathing (SPB): diaphragmatic breathing between 4.5 to 6.5 bpm.

slow-paced contraction (SPC): the simultaneous contraction of the wrists, core, and ankles to increase RSA.

ST segment: the portion of the ECG between ventricular depolarization and repolarization, which becomes depressed during ischemia.

synchrony: the phase relationship between two signals in which their peaks and valleys are aligned (e.g., HR and respirometer expansion reach their maximum and minimum values simultaneously).

thoracic breathing: a breathing pattern that primarily relies on the external intercostals to inflate the lungs, resulting in a more rapid respiration rate, excessive energy consumption, and incomplete ventilation of the lungs.

time-domain measures of HRV: indices like SDNN that measure the degree to which the IBIs between successive heartbeats vary.

torr: the unit of atmospheric pressure, named after Torricelli, which equals 1 millimeter of mercury (mmHg) and is used to measure end-tidal CO2.

trapezius-scalene placement: active SEMG electrodes are located on the upper trapezius and scalene muscles to measure respiratory effort.

ultra-low-frequency (ULF) band: the HRV frequency range below 0.003 Hz. Very-slow biological processes may contribute to this band, including circadian rhythms, core body temperature, metabolism, and the renin-angiotensin system. PNS and SNS contributions are possible.

vagal withdrawal: reduced parasympathetic (vagal) activity, often occurring in response to stress or excessive effort during training.

vascular tone rhythm: the rhythmic oscillation in blood vessel diameter that contributes to blood pressure regulation and HRV.

very-low-frequency (VLF) band: the HRV frequency range of 0.003-0.04 Hz that may represent temperature regulation, plasma renin fluctuations, endothelial and physical activity influences, and possible intrinsic cardiac, PNS, and SNS contributions.

References

Bridges, L. J., Denham, S. A., & Ganiban, J. M. (2004). Definitional issues in emotion regulation research. Child Development, 75(2), 340-345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00675.x

Carter, R., Cheuvront, S. N., Wray, D. W., Kolka, M. A., Stephenson, L. A., & Sawka, M. N. (2005). The influence of hydration status on heart rate variability after exercise heat stress. Journal of Thermal Biology, 30(7), 495-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2005.05.006

Constant, I., Laude, D., Murat, I., & Elghozi, J.-L. (1999). Pulse rate variability is not a surrogate for heart rate variability. Clinical Science, 97(4), 391-397. https://doi.org/10.1042/cs0970391

de Oliveira, R. A. M., Araújo, L. F., de Figueiredo, R. C., Goulart, A. C., Schmidt, M. I., Barreto, S. M., & Ribeiro, A. L. P. (2017). Coffee consumption and heart rate variability: The Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) Cohort Study. Nutrients, 9(7), 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9070741

Drew, B. J., Califf, R. M., Funk, M., Kaufman, E. S., Krucoff, M. W., Laks, M. M., Macfarlane, P. W., Sommargren, C., Swiryn, S., & Van Hare, G. F. (2004). Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: An American Heart Association scientific statement. Circulation, 110(17), 2721-2746. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59

Gevirtz, R. N. (2021). Personal communication regarding HRVB training goals.

Gevirtz, R. N., Lehrer, P. M., & Schwartz, M. S. (2016). Cardiorespiratory biofeedback. In M.S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.). Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Gilbert, C. (2012). Pulse oximetry and breathing training. Biofeedback, 40(4), 137-141. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-40.4.04

Ginsberg, J. P., Berry, M. E., & Powell, D. A. (2010). Cardiac coherence and posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 16(4), 52-60.

Grant, J., Wally, C., & Truitt, A. (2010). The effects of Kargyraa throat-singing and singing a fundamental note on heart rate variability [Abstract]. Poster presented at the meeting of the Biofeedback Foundation of Europe, Rome, Italy.

Grossman, P., & Kollai, M. (1993). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia, cardiac vagal tone, and respiration: Within- and between-individual relations. Psychophysiology, 30(5), 486-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1993.tb02072.x

Hemon, M. C., & Phillips, J. P. (2016). Comparison of foot finding methods for deriving instantaneous pulse rates from photoplethysmographic signals. Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing, 30(2), 157-168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-015-9695-6

Jan, H.-Y., Chen, M.-F., Fu, T.-C., Lin, W.-C., Tsai, C.-L., & Lin, K.-P. (2019). Evaluation of coherence between ECG and PPG derived parameters on heart rate variability and respiration in healthy volunteers with/without controlled breathing. Journal of Medical and Biological Engineering, 39, 783-795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40846-019-00468-9

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion Books.

Khazan, I. Z. (2013). The clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. Wiley-Blackwell.

Khazan, I. Z. (2019). Biofeedback and mindfulness in everyday life: Practical solutions for improving your health and performance while managing stress. New Harbinger Publications.

Lagos, L., Vaschillo, E., Vaschillo, B., Lehrer, P., Bates, M., & Pandina, R. (2011). Virtual reality assisted heart rate variability biofeedback as a strategy to improve golf performance: A case study. Biofeedback, 39(1), 15-20. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-39.1.11

Lehrer, P. M. (2007). Biofeedback training to increase heart rate variability. In P. M. Lehrer, R. M. Woolfolk, & W. E. Sime (Eds.). Principles and practice of stress management (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Lehrer, P. M. (2013). How does heart rate variability biofeedback work? Resonance, the baroreflex, and other mechanisms. Biofeedback, 41, 26-31. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.1.02

Lehrer, P. M., & Gevirtz, R. (2014). Heart rate variability: How and why does it work? Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756

Lehrer, P., Vaschillo, B., Zucker, T., Graves, J., Katsamanis, M., Aviles, M., & Wamboldt, F. (2013). Protocol for heart rate variability biofeedback training. Biofeedback, 41(3), 98-109.

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E., & Vaschillo, B. (2000). Resonant frequency biofeedback training to increase cardiac variability: Rationale and manual for training. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 25(3), 177-191. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009554825745

McCraty, R. (2013). Personal communication regarding the benefits of heartfelt emotion.

McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., Tiller, W. A., Rein, G., & Watkins, A. D. (1995). The effects of emotions on short-term power spectrum analysis of heart rate variability. American Journal of Cardiology, 76(14), 1089-1093. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80309-9

McCraty, R., Atkinson, M., Tomasino, D., & Bradley, R. T. (2006). The coherent heart. Institute of HeartMath.

McCraty, R., Atkinson M., Tomasino, D., & Bradley, R. T. (2009). The coherent heart: Heart-brain interactions, psychophysiological coherence, and the emergence of system-wide order. Integral Review, 5(2), 10-115.

Medeiros, R. F., Silva, B. M., Neves, F. J., Rocha, N. G., Sales, A. R. K., & Nobrega, A. C. (2011). Impaired hemodynamic response to mental stress in subjects with prehypertension is improved after a single bout of maximal dynamic exercise. Clinics, 66(9), 1523-1529. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1807-59322011000900003

Shaffer, F., & Moss, D. (2006). Biofeedback. In Y. Chun-Su, E. J. Bieber, & B. Bauer (Eds.). Textbook of complementary and alternative medicine (2nd ed.). Informa Healthcare.

Shaffer, F., Bergman, S., & Dougherty, J. (1998). End-tidal CO2 is the best indicator of breathing effort [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 23(2).

Shaffer, F., Bergman, S., & White, K. (1997). Indicators of diaphragmatic breathing effort [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 22(2), 145.

Shaffer, F., Greve, E., & Reinagel, K. (1996). Predictors of inhalation volume [Abstract]. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 21(4), 352.

Shaffer, F., Mayhew, J., Bergman, S., Dougherty, J., & Irwin, D. (1999). Designer jeans increase breathing effort [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 24(2), 124-125.

Shaffer, F., McCraty, R., & Zerr, C. L. (2014). A healthy heart is not a metronome: An integrative review of the heart's anatomy and heart rate variability. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01040

Taub, E., & School, P. J. (1978). Some methodological considerations in thermal biofeedback training. Behavior Research Methods & Instrumentation, 10(5), 617-622. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03205359

Vansickle, J., Putnam, R., Harris, M., Garcia, M., Bell, B., Nelson, M., & Lowery, L. (2020). Caffeine intake does not negatively affect heart rate variability in physically active university students: Preliminary findings. Current Development in Nutrition, 4(Supplement 2), 1770. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzaa066_025

Vaschillo, E., Lehrer, P., Rishe, N., & Konstantinov, M. (2002). Heart rate variability biofeedback as a method for assessing baroreflex function: A preliminary study of resonance in the cardiovascular system. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 27, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014587304314

Vaschillo, E. G., Vaschillo, B., Pandina, R. J., & Bates, M. E. (2011). Resonances in the cardiovascular system caused by rhythmical muscle tension. Psychophysiology, 48, 927-936. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01156.x

Wally, C., Korenfeld, I., Brooks, K., Carrell, D., Lau, D., Peterson, J., Schafer, M., Truitt, A., Fuller, J., Westermann-Long, A., & Korenfeld, D. (2011). Chanting "Om" increases heart rate variability by slowing respiration [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 36, 223.

Watso, J. C., & Farquhar, W. B. (2019). Hydration status and cardiovascular function. Nutrients, 11(8), 1866. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081866

Zerr, C., Kane, A., Vodopest, T., Allen, J., Fluty, E., Gregory, J., DeBold, M., Schultz, D., Robinson, G., Golan, R., Hannan, J., Bowers, S., Cangelosi, A., Korenfeld, D., Jones, D., Shepherd, S., Burklund, Z., Spaulding, K., Hoffman, W., & Shaffer, F. (2014). HRV biofeedback training raises temperature and lowers skin conductance. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 39(3), 299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-014-92549

Zerr, C., Kane, A., Vodopest, T., Allen, J., Hannan, J., Fabbri, M., Williams, C., Cangelosi, A., Owen, D., Cary, B., & Shaffer, F. (2015). Does inhalation-to-exhalation ratio matter in heart rate variability biofeedback? Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 40(2), 135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-015-9282-0

Return to Top