Learning

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit covers Overview of principles of human learning as they apply to neurofeedback (I-C).

Professionals completing this unit will be able to discuss:

- Overview of principles of human learning as they apply to neurofeedback

A. Learning theory

B. Application of learning principles to neurofeedback training

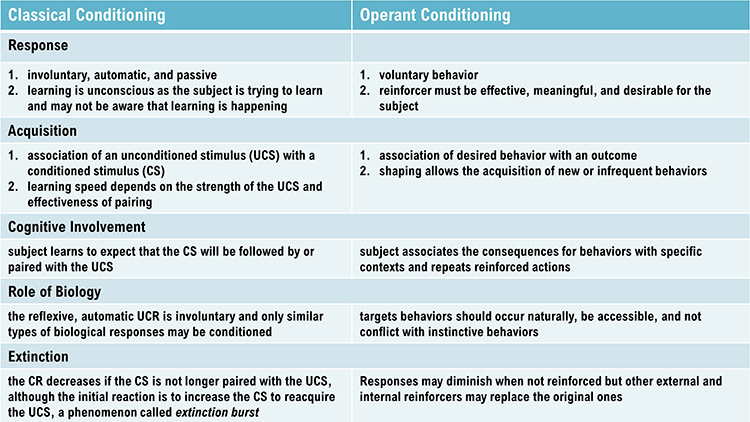

Three Main Types of Learning

We can divide learning into three main categories: associative, nonassociative, and observational. Associative learning and observational learning are most relevant to neurofeedback. In associative learning, we create connections between stimuli, behaviors, or stimuli and behaviors. Associative learning aids our survival since it allows us to predict future events based on past experience. Learning that B follows A provides us with time to prepare for B. Two forms of associative learning are classical conditioning and operant conditioning (Cacioppo & Freberg, 2016).

Classical Conditioning

Pavlov demonstrated classical conditioning in 1927 based on his famous research with dogs. Due to faulty English translations, we now use the adjectives conditioned and unconditioned instead of conditional and unconditional. We will use the current terminology to minimize confusion.

Classical conditioning is an unconscious associative learning process that builds connections between paired stimuli that follow each other in time. Through this learning process, a dog in Pavlov's laboratory learned that if A (a ringing bell) occurs, B (food) will follow. The ability to predict the future from past experience is crucial to our survival since it gives us time to prepare.

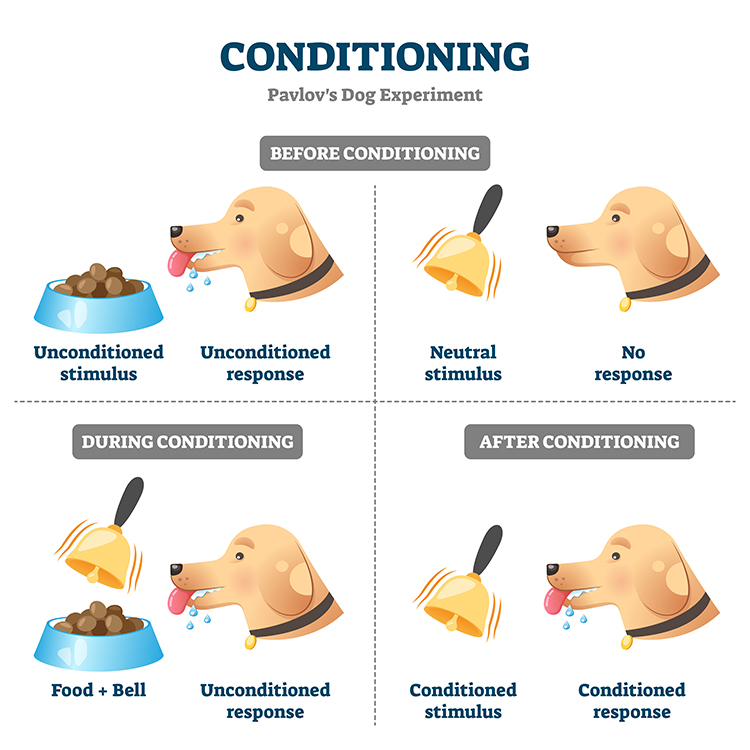

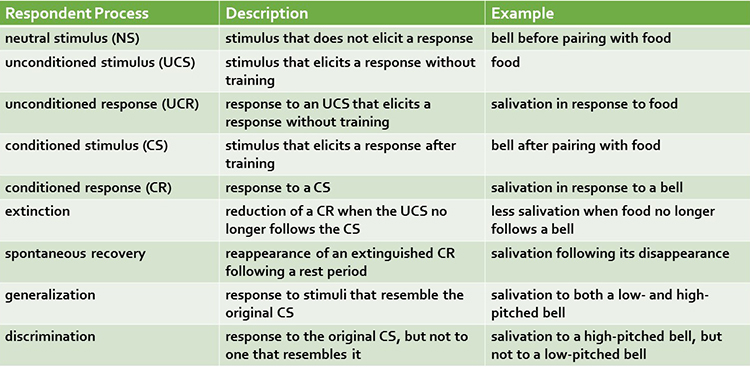

Before learning to anticipate food in Pavlov's laboratory, dogs salivated (unconditioned response) when they saw food (unconditioned stimulus). An unconditioned response (UCR) follows an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) before conditioning. However, until dogs learned to associate the sound of a bell with the delivery of food, the bell was a neutral stimulus (NS) which did not elicit salivation.

Through repeated pairing of the bell with the arrival of food, Pavlov's dogs learned that the bell reliably signaled the arrival of food. Now, the bell became a conditioned stimulus (CS) which elicited the conditioned response (CR) of salivation. Graphic © VectorMine/iStockphoto.com.

When the association between the CS and CR is disrupted because B no longer consistently follows A, the frequency of the CR may decline or the CR may disappear. This phenomenon is called extinction. In Pavlov's situation, repeated trials where food did not follow bell ringing reduced or eliminated salivation. Extinction of CRs allows us to adapt to changes in our experience. You learn to use passwords less predictable than password after you become a victim of identity theft. You are able to play with dogs, again, after you were bitten as a child.

Pavlov argued that extinction is not forgetting, but evidence of new learning that overrides previous learning. The phenomenon of spontaneous recovery, where the CR (salivation) reappears after a period of time without exposure to the CS (bell) supports his position. Dogs who stopped salivating by the end of an extinction trial in which no food followed the bell often resumed salivating during a break or the next session.

Generalization and discrimination are mirror images of each other. In generalization, the conditioned response is elicited by stimuli (low-pitched bell) that resemble the original conditioned stimulus (high-pitched bell). Generalization promotes our survival because it allows us to apply learning about one stimulus (lions) to similar predators (tigers) without experiencing them.

In contrast, in discrimination, the conditioned response (salivation) is elicited by one stimulus (high-pitched bell), but not another (low-pitched bell). When soldiers return to civilian life, they must distinguish between a CS that signals danger (gunfire) and one that is benign (fireworks). Discrimination is often impaired in soldiers diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Operant Conditioning

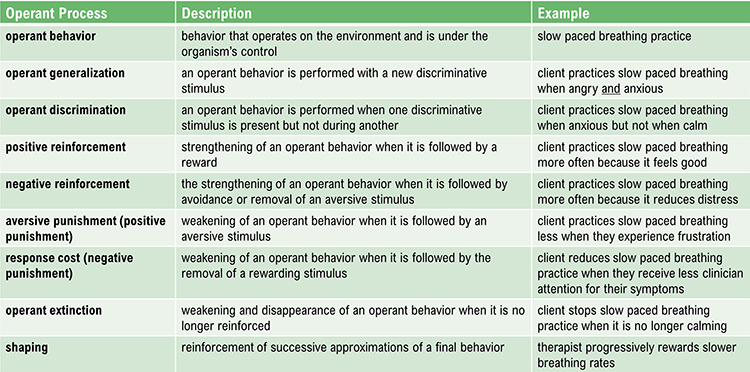

Edward Thorndike's (1913) law of effect proposed that the consequences of behavior determine its addition to your behavioral repertoire. From his perspective, cats learned to escape his "puzzle boxes" by repeating successful actions and eliminating unsuccessful ones.

Operant conditioning is an

unconscious associative learning process that modifies an operant behavior, voluntary behavior that operates on the environment to produce an outcome, by manipulating its

consequences (Miltenberger, 2016).

Operant conditioning differs from

classical conditioning in several respects. Where operant conditioning teaches the association of a voluntary behavior with its consequences, classical conditioning teaches the predictive relationship between two stimuli to modify involuntary behavior.

Neurofeedback teaches self-regulation of neural activity and related "state changes" using operant conditioning via the selective presentation of reinforcing stimuli, including visual, auditory, and tactile displays.

Neurofeedback as a Learning Environment

Kerson, Sherlin, and Davelaar (2025) reframe neurofeedback as the construction of an engineered learning environment rather than simply a physiological measurement technique. Their central argument is that outcomes improve when clinicians treat feedback as a training ecosystem that either facilitates or impedes learning, rather than merely as information about brain states. This perspective explains common clinical puzzles such as why a client performs well in session but cannot reproduce the trained state at home, or why improvements plateau despite motivation and compliance.

The training process operates on two parallel tracks. Explicit learning occurs when clients deliberately employ strategies like softening their gaze, relaxing the jaw, pacing their breathing, or directing attention in specific ways. Implicit learning occurs when the nervous system gradually discovers stable patterns that earn reward without the client being able to fully articulate what changed. Many clients improve through a combination of both processes, with the balance varying by age, cognitive style, symptom profile, and even fatigue level on a given day.

When a client says "I don't know how I did it," this often reflects normal implicit learning and should not alarm the clinician. The genuine warning sign is when success appears random both to the client and in the data—for example, when reward rates fluctuate wildly despite consistent effort. This pattern typically signals a problem with the learning environment itself, not with client motivation (Kerson et al., 2025).

Operant conditioning occurs with a situational context. The identifying characteristics of a situation are called its discriminative stimuli and can include the physical environment and physical, cognitive, and emotional cues. Discriminative stimuli teach us when to perform operant behaviors.

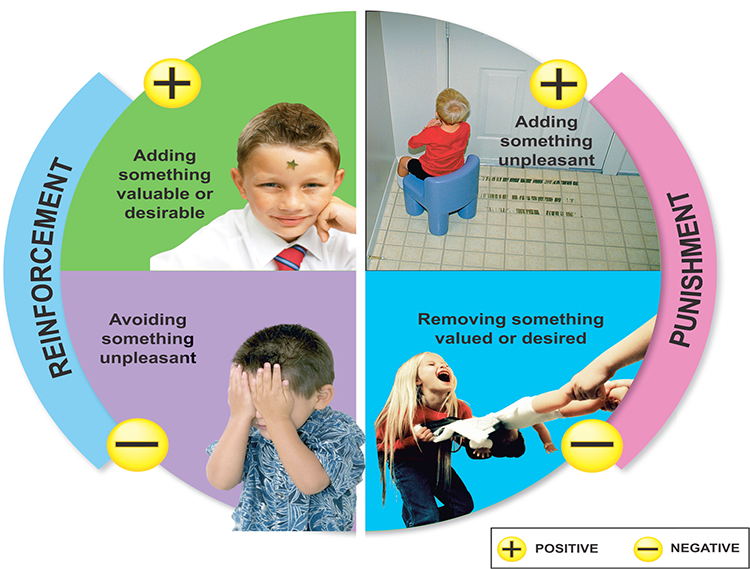

The consequences of operant behaviors can increase or decrease their frequency. Skinner proposed four types of consequences: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment. Where positive and negative reinforcement increase behavior, positive and negative punishment decrease it.

Due to individual differences, we cannot know in advance whether a consequence will be reinforcing or punishing, since these are not intrinsic properties of a consequence. We can only determine whether a consequence is reinforcing or punishing by measuring how it affects the behavior that preceded it. In neurofeedback, a movie that motivates the best performance might be the most reinforcing for the client, regardless of the therapist's personal preference.

Positive reinforcement increases the frequency of a desired behavior by making a desired outcome contingent on performing the action. For example, a movie plays when a client diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) increases low-beta and decreases theta activity.

Negative reinforcement increases the frequency of a desired behavior by making the avoidance, termination, or postponement of an unwanted outcome contingent on performing the action. For example, a athlete's anxiety decreases by shifting from high beta to low beta.

Positive punishment decreases or eliminates a undesirable behavior by associating it with unwanted consequences. For example, a child's increased fidgeting dims a favorite movie and decreases the sound.

Negative punishment decreases or eliminates a undesirable behavior by removing what is desired. For example, oppositional behavior could result in a clinician turning off a popular game.

Speed of Reinforcement

The timing of reinforcement is critical to associating the desired behavior with its consequences. Several early studies have shown that the optimal latency between a voluntary behavior and reinforcement is between under 250 to 350 ms (Felsinger & Gladstone, 1947; Grice, 1948). The faster the delivery of reinforcement following the desired behavior, the less time required for skill acquisition.

Latency as a Clinical Variable

Feedback latency—the time delay between a physiological event and the delivery of feedback—matters more than many clinicians realize. If the reward arrives too late, the nervous system may strengthen whatever response occurred closer in time to the reward, which might be a compensatory strategy, an artifact, or a brief change unrelated to the intended target. In essence, delayed feedback can train the wrong thing (Kerson et al., 2025).

Neurofeedback platforms accumulate latency through a sequence of processing steps: signal acquisition, filtering, artifact handling, feature computation, threshold comparison, and visual or auditory display. Even when each step is fast, total latency can creep upward. Clinicians should treat latency as a meaningful clinical variable rather than an invisible detail. Simple behavioral signs can help detect latency problems. If clients report that feedback feels "behind," they may be noticing a real mismatch. If they can only increase reward by performing abrupt, effortful actions—tensing, blinking, or holding their breath—the system may be rewarding short-lived transients or artifacts that happen to be temporally aligned with reward delivery.

When latency is corrected or processing simplified, clinicians often observe a qualitative change: clients can succeed with calmer, steadier strategies, and the reward becomes easier to sustain (Kerson et al., 2025).

Reinforcement Criteria

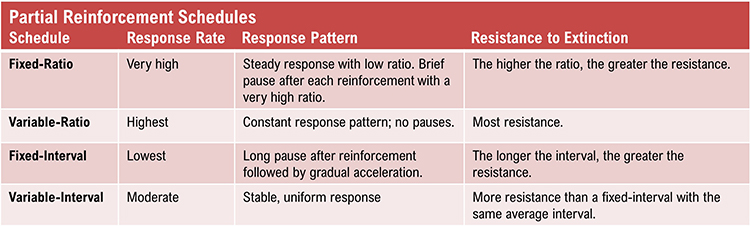

Current research is exploring the optimal reinforcement criteria for neurofeedback training. Client skill acquisition is markedly affected by changing parameters like reinforcement schedule, frequency of reward, reinforcement delay, conflicting reinforcements, conflicting expectations, and alteration of the environment.

While continuous reinforcement, reinforcement of every desired behavior, is helpful during the early stage of skill acquisition, it is impractical as clients attempt to transfer the skill to real-world settings. Since reinforcement outside of the clinic is intermittent, partial reinforcement schedules, where desired behavior is only reinforced some of the time, are important as training progresses. This reduces the risk of extinction, where failure to reinforce a desired behavior reduces the frequency of that behavior.

For neurofeedback, variable reinforcement schedules, where reinforcement occurs after a variable number of responses (variable ratio) or following a variable duration of time (variable interval) produce superior response rates than their fixed counterparts.

Reinforcement Schedules as Clinical Levers

The difference between continuous and interval schedules affects what clients experience more than many clinicians appreciate. When reinforcement is essentially continuous, clients tend to feel a smoother, more responsive system; they can experiment and notice what increases reward. When reinforcement is sampled at intervals, brief moments of achieving the target state may be missed, creating the subjective experience that the system is "stingy" or inconsistent—even when the client is intermittently producing the target state (Kerson et al., 2025).

Clinicians can treat reward feel—the client's subjective sense of how responsive and predictable the feedback is—as a diagnostic signal. If a competent, engaged client reports that rewards seem disconnected from their efforts, suspect a schedule, threshold, or artifact issue before assuming resistance or poor insight. Test this by temporarily simplifying the task, raising reward probability, or switching feedback modalities (for example, pairing a clear auditory tone with a simple visual indicator). If the client suddenly "finds it," the learning environment was probably too difficult or too noisy.

Signal Quality and Reinforcement Integrity

A session can unintentionally drift toward sham-like conditions whenever reinforcement loses contingency with the intended brain state. This can occur for reasons that appear mundane. EEG artifact can inflate or suppress the very metrics being rewarded. Muscle tension can masquerade as high-frequency activity. Eye movements can contaminate frontal sites. Poor electrode contact can introduce slow drift. Line noise can add rhythmic contamination that a client cannot control. In all these cases, the system may deliver rewards unrelated to the intended brain state.

From the client's perspective, such a task becomes a slot machine. Some clients continue to improve because they learn relaxation, attentional stability, or expectancy-driven control. Others stagnate because the nervous system cannot reliably discover what earns reward. A practical approach is to track reinforcement integrity as a routine clinical variable. Ask, in plain language: "Is the client being rewarded for the thing we think we are rewarding?" If uncertain, increase artifact monitoring, reduce complexity, tighten signal quality checks, or temporarily shift training to a simpler physiological channel—such as respiration pacing or peripheral temperature—to restore a clean contingency while troubleshooting the EEG (Kerson et al., 2025).

Shaping

Shaping, the method of successive approximations, teaches clients new behaviors and increases the frequency of behaviors that are rarely performed. A clinician starts by reinforcing spontaneous voluntary behaviors that resemble the desired behavior and then progressively raises the criteria for reinforcement to achieve the training goal. For example, the clinician can gradually require lower theta-to-beta ratios for a movie to play.

Threshold Management and Reward Probability

If a task is too difficult from the start, the client does not get enough successful trials to learn. Many clients benefit from an initial phase in which rewards are frequent enough to allow the nervous system to discover the pathway, followed by gradual tightening of criteria. This is shaping in action: reinforcing successive approximations toward the final target rather than demanding perfection immediately.

Threshold drift can make success unpredictable. If thresholds auto-adjust too aggressively, the client experiences a moving target that undermines learning. If thresholds never adjust, the client can reach a ceiling where improvement no longer changes the reward. A clinically sensible approach is to adjust thresholds deliberately, in small steps, and to explain the purpose: "We are making it slightly harder so your brain keeps learning," or "We are making it slightly easier so you can find the pattern again" (Kerson et al., 2025).

Preventing Accidental Training

Accidental training occurs when clients are inadvertently reinforced for artifacts, compensatory strategies, or non-target behaviors because feedback is not tightly contingent on the intended physiological state. If a client discovers that jaw tension increases reward, they may continue to do it. If they find that breath-holding increases reward, they may overuse it. If staring harder increases reward, they may train strain rather than self-regulation. Clinicians can prevent this by monitoring posture, facial tension, breathing, and effort level, and then explicitly reinforcing strategies that are sustainable and healthy (Kerson et al., 2025).

Discrimination and Generalization

Discrimination and generalization are the ultimate goals of neurofeedback training. Discrimination teaches when a desired behavior will be reinforced. The initial discriminative stimuli include the cues provided by the training environment, like animations and tones. Following successful skill acquisition, a clinician may introduce a stressor to "raise the bar." Now, the stressor serves as another discriminative stimulus for performing the desired behavior.

Generalization teaches the transfer of a desired behavior to multiple environments and in response to diverse stressors. While the ability to perform the learned response in many situations contributes to flexibility, it is not always advantageous. Discrimination, based on an understanding of set and setting, helps determine when a response is required and which response is appropriate.

Phenomenological Awareness and State Recognition

A key factor in successful generalization is phenomenological awareness—the client's ability to notice, describe, and recognize what the target state feels like, how it arises, and how to return to it. This awareness addresses a common clinical complaint: "I can do it in session but not in life." Cultivating this awareness does not require turning sessions into therapy talk. After a good training run, simply ask the client to describe the state in sensory language: What changed in breathing, muscle tone, gaze, posture, or emotional tone? What was the smallest action that helped? If the client cannot describe it, provide options rather than forcing introspection. Over time, the client builds a personal map of the trained state (Kerson et al., 2025).

This phenomenological work also helps detect when learning is happening through an unhelpful route. For example, a client might increase reward by becoming rigidly focused, which may appear as "success" in the signal but feel subjectively like strain. Capturing the client's phenomenology allows the clinician to redirect learning toward a calmer strategy that supports real-world transfer.

Building Transfer on Purpose

Transfer trials reduce feedback so the client must reproduce the target state without constant external cues. Clinicians can build transfer inside the session by turning feedback off for brief intervals, then turning it back on to check whether the client can regain the state. Between-session practice can also mirror the trained state, such as short blocks of attention training, paced breathing within a comfortable range, or relaxation routines tied to the same cues used in session. Bridging implicit operant learning with explicit state recognition is essential for lasting benefits (Kerson et al., 2025).

Check out the TED-Ed video, The Difference Between Classical and Operant Conditioning, when you are connected to the internet.

Expectancy and the Ethical Use of Hope

Clients do not arrive as blank slates. They arrive with hope, skepticism, fear, and stories about what their symptoms mean. Expectancy—a client's belief about what will happen in treatment—shapes attention, effort, and persistence, all of which are learning-relevant behaviors. The goal is not to eliminate expectancy but to harness it ethically and keep it aligned with skill acquisition. Clinicians can offer a credible rationale, make the task understandable, and explain that progress is often nonlinear. Setting realistic expectations about what learning typically looks like—early gains in state control that later need to consolidate into trait change—helps maintain engagement (Kerson et al., 2025).

A helpful clinician stance is to treat hope as fuel and data quality as steering. Encouragement can coexist with insistence on clean signals, good thresholds, and honest interpretation. This prevents a common failure mode in which optimism masks a weak learning environment, leading to long stretches of training that appear busy but do not yield stable skills.

History of EEG Conditioning

Durup, G., & Fessard, A. I. (1935). Blocking of the alpha rhythm, L'ann'ee Psychologique, 36(1), 1-32.

Loomis, A. L., Harvey, E. N., and Hobart, G. (1936). Electrical potentials of the human brain. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 19, 249.

Travis, L. E., & Egan, J. P. (1938), Conditioning of the electrical response of the cortex. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 22(6), 524-531.

Jasper, H., & Shagass, C. (1941). Conditioning the occipital alpha rhythm in man. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 28(5), 373-387.

Knott, J. R. (1941). Electroencephalography and physiological psychology: Evaluation and statement of problem. Psychological Bulletin, 38(10), 944-975.

Kamiya, J. (2011). The first communications about operant conditioning of the EEG, Journal of Neurotherapy, 15(1), 65-73.

Clemente, C. D., Sterman, M. B., & Wyrwicka, W. (1964). Post-reinforcement EEG synchronization during alimentary behavior. Electroencephalography Clinical Neurophysiology, 355-365.

Albino, R., & Burnand, G. (1964). Conditioning of the alpha rhythm in man. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 67(6), 539-544.

Wyrwicka, W., & Sterman, M. B. (1968). Instrumental conditioning of sensorimotor cortex EEG spindles in the waking cat. Physiology and Behavior, 3(5), 703-707.

Sterman, M. B., LoPresti, R. W., & Fairchild, M. D. (1969). Electroencephalographic and behavioral studies of monomethyl hydrazine toxicity in the cat. Technical Report AMRL-TR-69-3, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, Air Systems Command.

Observational Learning

Observational learning allows us to rapidly modify an existing skill or acquire a new one by observing others. This social learning process is extremely efficient because it bypasses trial-and-error. We don't personally experience negative outcomes since others have done it for us.

Observational learning is interactive. For example, we listen to a teacher play a violin passage, we attempt to play the same notes, and then compare the two performances. We play the passage, again and again, until we "get it right." Feedback allows us to refine our playing until we can match the original sample.

Glossary

accidental training: an unintended learning process in which the client is reinforced for artifacts, compensatory strategies, or non-target behaviors because the feedback is not tightly contingent on the intended physiological state.

classical conditioning: unconscious associative learning process that builds connections between paired stimuli that follow each other in time.

conditioned response (CR): in classical conditioning, a response to a conditioned stimulus (CS). For example, salivation in response to a bell.

conditioned stimulus (CS): in classical conditioning, a stimulus that elicits a response after training. For example, a bell after pairing with food.

discrimination (classical conditioning): response to the original CS, but not to one that resembles it. For example, salivation to a high-pitched bell, but not to a low-pitched bell.

discrimination (operant conditioning): performance of the desired behavior in one context, but not another. For example, increasing sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) activity at bedtime, but not during a morning commute.

discriminative stimuli: in operant conditioning, the identifying characteristics of a situation (the physical environment and physical, cognitive, and emotional cues) that teach us when to perform operant behaviors. For example, a traffic slowdown could signal a client to practice effortless breathing.

expectancy: a client's belief about what will happen in treatment, which can shape attention, motivation, perceived control, and symptom experience, thereby influencing learning and outcomes.

explicit learning: a conscious learning process involving deliberate strategy selection and awareness of what is being practiced. Examples include softening the gaze, relaxing the jaw, or pacing the breath.

extinction (classical conditioning): the reduction of a CR when the UCS no longer follows the CS. For example, less salivation when food no longer follows a bell.

extinction (operant conditioning): a reduction in response frequency when the desired behavior is no longer reinforced. For example, a client practices less when the clinician ceases to praise this behavior.

feedback latency: the time delay between a physiological event and the delivery of feedback, which can affect what is learned. Excessive latency may cause the nervous system to strengthen the wrong response.

generalization (classical conditioning): response to stimuli that resemble the original CS. For example, salivation to both a low- and high-pitched bell.

generalization (operant conditioning): performance of the desired behavior in multiple contexts. For example, increasing low-beta activity during both classroom lecture and golf practice.

implicit learning: an unconscious learning process in which neural patterns are strengthened through reinforcement without the learner being able to articulate how the change occurred.

learning: the process by which we acquire new information, patterns of behavior, or skills.

learning environment: the engineered training ecosystem in neurofeedback, encompassing reinforcement schedules, timing, signal integrity, and threshold settings, which collectively determine what the nervous system actually learns.

negative punishment: in operant conditioning, learning by observing others. For example, a child’s oppositional behavior could result in a clinician turning off a popular game.

negative reinforcement: in operant conditioning, a process that increases the frequency of a desired behavior by making the avoidance, termination, or postponement of an unwanted outcome contingent on performing the action. For example, an athlete’s anxiety decreases by shifting from high beta to low beta, rewarding this self-regulation.

neutral stimulus (NS): in classical conditioning, a stimulus that does not elicit a response. For example, a bell before pairing with food.

operant behavior: in operant conditioning, a process that decreases or eliminates a undesirable behavior by removing what is desired. For example,

observational learning: learning by observing others. For example, a fitness client learns to stretch by watching a personal trainer demonstrate the technique.

operant conditioning: an unconscious associative learning process that modifies an operant behavior, voluntary behavior that operates on the environment to produce an outcome, by manipulating its consequences.

phenomenological awareness: the client's ability to notice, describe, and make meaning of the subjective experience of the target state, including changes in breathing, muscle tone, gaze, posture, or emotional tone.

positive punishment: in operant conditioning, a process that decreases or eliminates an undesirable behavior by associating it with unwanted consequences. For example, a child's increased fidgeting dims a favorite movie and decreases the sound.

positive reinforcement: in operant conditioning, a process that decreases or eliminates a undesirable behavior by associating it with unwanted consequences. For example, a movie plays when a client increases low-beta and decreases theta activity.

reinforcement integrity: the degree to which feedback rewards are actually contingent on the intended physiological state rather than artifacts or unintended behaviors.

reward feel: a client's subjective sense of how responsive and predictable the feedback is—whether rewards seem clearly tied to their efforts and internal state changes.

shaping: in operant conditioning, the method of successive approximations, which teaches clients new behaviors and increases the frequency of behaviors that are rarely performed. For example, a clinician progressively requires lower theta-to-beta ratios for a movie to play.

spontaneous recovery: in classical conditioning, the reappearance of an extinguished CR following a rest period. For example, salivation following its disappearance.

stimulus discrimination: in classical conditioning, when a conditioned response (CR) is elicited by one conditioned stimulus (CS), but not by another. For example, your blood pressure increases during a painful dental procedure, but not during an uncomfortable blood draw.

stimulus generalization: in classical conditioning, when stimuli that resemble a conditioned stimulus (CS) elicit the same conditioned response (CR). For example, when your blood pressure increases during a painful dental procedures and an uncomfortable blood draw.

threshold drift: unpredictable changes in the criteria for reward delivery, often caused by overly aggressive auto-adjustment, which can undermine learning by creating a moving target for the client.

transfer trials: a practice method that reduces or removes feedback so the learner must achieve the target state under more naturalistic conditions, supporting generalization to daily life.

unconditioned response (UCR): in classical conditioning, a response to an UCS that elicits a response without training. For example, salivation in response to food

unconditioned stimulus (UCS): in classical conditioning, a stimulus that elicits a response without training. For example, food.

Test Yourself on CLASSMARKER

Click on the ClassMarker logo below to take a 10-question exam over this entire unit.

REVIEW FLASHCARDS ON QUIZLET

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, which sounds do you prefer when you have succeeded during neurofeedback training? Which visual displays are more motivating for you?

References

Cacioppo, J. T., & Freberg, L. A. (2016). Discovering psychology. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Felsinger, J. M., & Gladstone, A. I. (1947). Reaction latency (StR) as a function of the number of reinforcements (N). Journal of Experimental Psychology, 37(3), 214-228.

Grice, G. R. (1948). The acquisition of a visual discrimination habit following response to a single stimulus. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38(6), 633-642,

Kerson, C., Sherlin, L. H., & Davelaar, E. J. (2025). Neurofeedback, biofeedback, and basic learning theory: Revisiting the 2011 conceptual framework. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-025-09756-4

Miltenberger, R. G. (2016). Behavior modification: Principles and procedures. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Thorndike, E. L. (1913). Educational psychology: Briefer course. New York, NY: Teachers College.