Pain Anatomy

What You Will Learn

This chapter explores the neuroscience of pain from nociceptors to brain networks, with direct applications to biofeedback practice. You will learn how pain signals travel from free nerve endings through the spinal cord to the brain, how the Gate Control Theory revolutionized our understanding of pain modulation, and why chronic pain represents a fundamental transformation of the nervous system rather than just prolonged acute pain. You will discover how inflammation can be both friend and foe in pain conditions, how trigger points may involve sympathetically-activated muscle spindles, and how the biopsychosocial and fear-avoidance models guide modern treatment. You will understand how pain alters heart rate variability (HRV), electrodermal activity (EDA), respiration, and sleep, and why these changes matter for biofeedback clinicians. Finally, you will explore cutting-edge concepts including nociplastic pain, the dynamic pain connectome, and sodium channel therapeutics that are reshaping pain science.

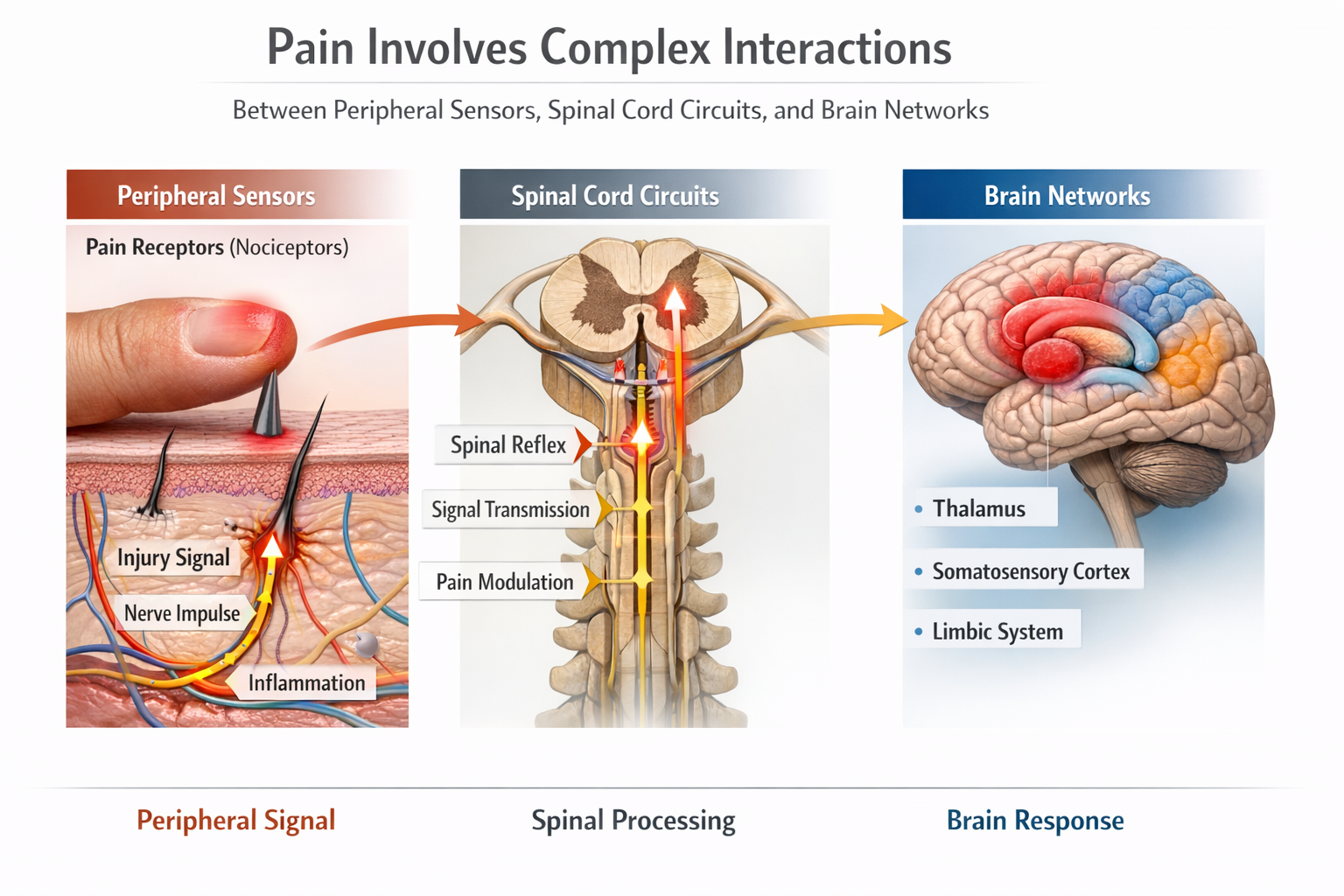

Pain Perception: The Body's Alarm System

Pain warns of actual or impending tissue damage. We use this information to safely navigate our environment and detect early signs of disease or injury. The experience of pain is both sensory and emotional, involving the detection of harmful stimuli and the motivational drive to escape or protect the threatened area. Understanding how pain works at every level, from molecular receptors to brain networks, is essential for effective biofeedback practice.

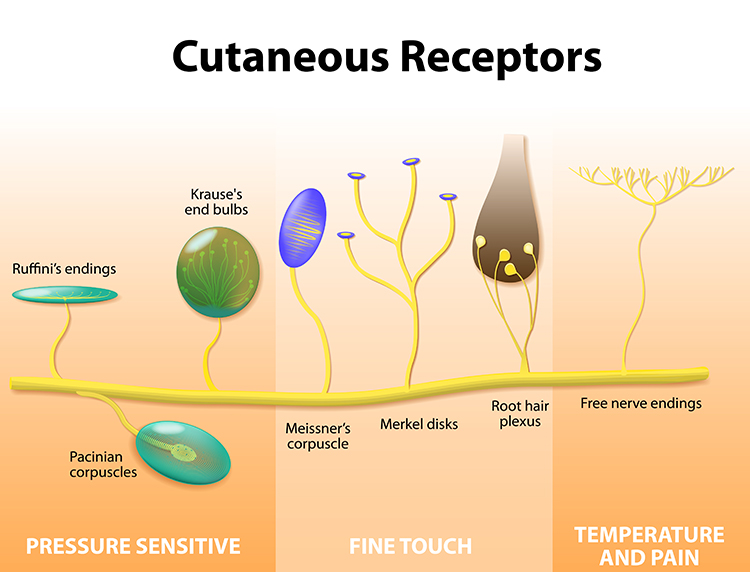

Nociceptors: The Damage Detectors

Free nerve endings are sensory receptors that detect painful stimuli. Unlike touch receptors that are wrapped in specialized capsules, these pain detectors are simply naked nerve terminals scattered throughout your skin, muscles, joints, and internal organs. They function as the body's early warning system, responding to three types of potentially damaging stimuli.

Mechanoreceptors respond to intense pressure that could crush or tear tissue. Chemoreceptors detect tissue damage by sensing the chemical soup released when cells are injured. Thermoreceptors fire when temperatures become extreme enough to cause burns or frostbite. Many nociceptors are polymodal, meaning they respond to multiple types of threats simultaneously.

Nav1.7 and 1.8 Sodium Channels

Two sodium channels, Nav1.7 and Nav1.8, are particularly important in pain signaling. Nav1.7 acts as a "fuse," amplifying small depolarizations in sensory neurons, while Nav1.8 serves as a "firecracker," generating the majority of the electrical current needed for neurons to fire an action potential. Dysfunction in these channels can lead to extreme pain or, conversely, an inability to feel pain.

The FDA approved suzetrigine, a selective Nav1.8 inhibitor, in 2025 as Journavx (jor-na-vix) for treating moderate to severe acute pain.

The Chemical Cascade of Pain

When tissue is damaged, injured cells release a potent chemical cocktail that activates and sensitizes nociceptors. Substance P is released by the nociceptors themselves and causes nearby blood vessels to leak fluid, producing the swelling you see around injuries.

Bradykinin is one of the most potent pain-producing substances known, directly exciting nociceptors and lowering their activation threshold so even gentle touch becomes painful.

Histamine produces that familiar itching and burning sensation while also causing blood vessels to dilate, producing redness and warmth.

Prostaglandins do not cause pain directly but dramatically amplify the sensitivity of nociceptors to other chemicals. This is why aspirin and ibuprofen work: they block prostaglandin synthesis, reducing nociceptor sensitization.

Finally, nerve growth factor (NGF) maintains nociceptor health but also increases their sensitivity during inflammation, contributing to the prolonged tenderness after injuries (Breedlove & Watson, 2023).

Afferent Fibers: The Pain Highways

Once nociceptors detect damage, they must communicate that information to the spinal cord and brain. Four types of afferent (incoming) nerve fibers carry sensory information, differing in diameter and whether they are wrapped in myelin insulation.

A-alpha fibers are the largest and fastest, conducting signals at up to 120 meters per second. They carry proprioceptive information about muscle length and joint position, not pain.

A-beta fibers are also large and fast, transmitting information about light touch, pressure, and vibration. These are the fibers that "close the gate" in Gate Control Theory when you rub an injury to reduce pain.

A-delta fibers are thin, lightly myelinated fibers that conduct the first, sharp, localized pain you feel immediately after an injury at about 5-30 meters per second. When you stub your toe, that initial sharp stab is carried by A-delta fibers.

C-fibers are the thinnest and slowest, lacking myelin entirely and conducting at only 0.5-2 meters per second. They carry the second wave of pain: the dull, burning, aching, poorly localized sensation that follows the initial sharp pain and lingers for minutes to hours (Duan et al., 2017; Treede, 2016).

Referred Pain: When the Map Gets Confused

Referred pain occurs when pain from internal organs is perceived as coming from a distant body surface. The classic example is heart attack pain felt in the left arm, jaw, or back. This happens because visceral afferents from internal organs converge onto the same spinal cord neurons that receive input from skin, and the brain typically interprets activity in these neurons as coming from skin rather than organs. Other examples include gallbladder pain referred to the right shoulder blade, kidney pain felt in the lower back and groin, and appendix pain that begins around the navel before localizing to the lower right abdomen (Bear et al., 2020).

Check Your Understanding

- Why does rubbing an injury help reduce pain? What type of nerve fibers are involved?

- Explain the difference between "first pain" and "second pain" in terms of the nerve fibers that carry them.

- How do prostaglandins contribute to pain, and why do NSAIDs like ibuprofen reduce pain?

The Dorsal Horn: Pain's First Processing Center

Pain signals do not travel straight from injury to brain like a simple wire. They first pass through the dorsal horn, the top portion of the spinal cord's gray matter, where they are processed, amplified, or dampened before ascending to higher centers. This is where Melzack and Wall placed their famous "gate" and where modern research has revealed astonishing complexity.

Microglia: The Brain's Immune Cells Gone Rogue

One of the most important discoveries in pain science is the role of glial cells in chronic pain. Microglia are the brain and spinal cord's resident immune cells.

After nerve injury, they become activated and release brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which causes a remarkable change in how dorsal horn neurons respond to the inhibitory neurotransmitters GABA and glycine.

Normally, GABA and glycine make neurons less likely to fire by allowing chloride ions to flow in. But BDNF reverses the chloride gradient, so these "inhibitory" transmitters now excite neurons instead of calming them. The result is allodynia, where normally non-painful stimuli like light touch become excruciating (Coull et al., 2005; Inoue & Tsuda, 2018).

Cluster Firing: The Spark of Spontaneous Pain

Chronic pain often seems to come from nowhere, with intense flares that have no obvious trigger. Recent research has identified a mechanism that may explain this: cluster firing. When sensory neurons in the dorsal root ganglia become hyperexcitable after injury, groups of them begin to fire together in synchronized bursts. This happens because glutamate and substance P released by one neuron spill over to excite its neighbors, creating waves of activity that the brain interprets as intense, spontaneous pain. The cluster firing pattern closely matches the timing and intensity of spontaneous pain reports in both animal models and human patients (Zeng et al., 2021).

Check Your Understanding

- How do microglia contribute to the development of allodynia after nerve injury?

- What is cluster firing and how might it explain spontaneous pain in chronic pain patients?

Trigger Points: Where Muscle Meets Pain

If you have ever pressed on a tight, tender knot in your neck or shoulder and felt pain shoot to a distant location, you have encountered a myofascial trigger point. These hyperirritable spots in taut muscle bands are among the most common sources of musculoskeletal pain, yet their exact nature remains surprisingly controversial.

What Are Trigger Points?

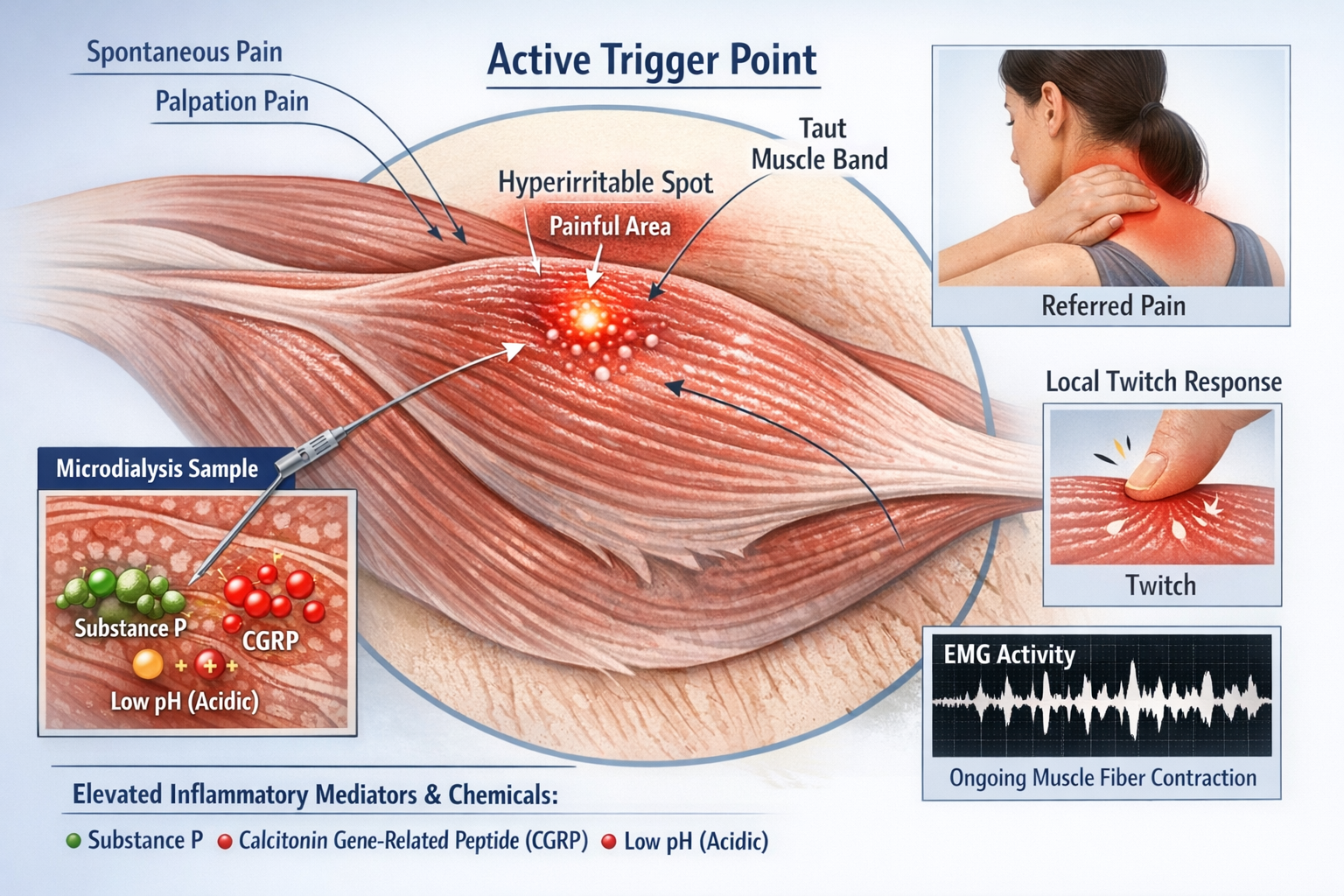

Most researchers agree on the clinical definition: a trigger point is a hyperirritable spot in a taut band of skeletal muscle that is painful on palpation and can produce referred pain and a local twitch response. Active trigger points cause spontaneous pain; latent ones hurt only when pressed.

Studies using microdialysis needles have found that trigger points contain elevated levels of inflammatory mediators and pain-related chemicals including substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), and hydrogen ions that create an acidic environment. Electromyography shows spontaneous electrical activity at trigger points, indicating ongoing muscle fiber contraction even at rest (Do et al., 2018; Shah et al., 2015).

The Muscle Spindle Connection

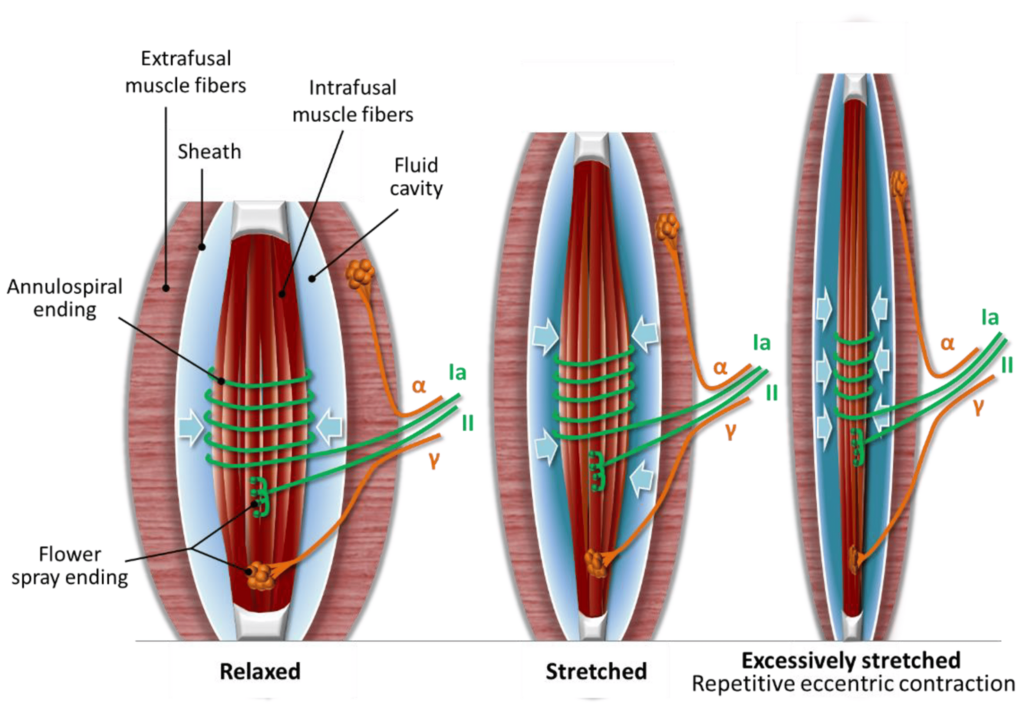

A fascinating development in trigger point research involves muscle spindles, the tiny stretch sensors embedded within muscles. Originally thought to be purely proprioceptive organs, muscle spindles are now implicated as potential pain generators. When researchers insert EMG needles into random muscle tissue, only about 4% of insertions cause pain. But when the needle hits an "active spot" showing the characteristic end-plate spikes of spindle activity, 86% of insertions are painful. This suggests that muscle spindles may contain high-threshold mechanosensitive nociceptors that contribute significantly to muscle pain (Partanen et al., 2023).

Sympathetic Activation of Muscle Spindles

Human muscle spindles receive direct sympathetic nervous system innervation. Immunohistochemical studies have identified neuropeptide Y, tyrosine hydroxylase-positive sympathetic terminals, and adrenergic receptors on intrafusal fibers, spindle blood vessels, and nearby free nerve endings. This provides an anatomical pathway for stress-related sympathetic activation to modulate spindle behavior. In animal studies, sympathetic stimulation alters spindle firing rates through alpha-2 adrenergic receptors. Although not confirmed in humans, the clinical implication is that psychological stress and autonomic arousal may directly influence muscle pain through effects on spindle sensitivity (Hellström et al., 2005; Ortiz et al., 2022; Radovanovic et al., 2015).

Gevirtz's (2003)

sympathetic nervous system mediational model of muscle pain

proposes that lack of assertiveness and resultant worry each trigger

sympathetic activation. Increased sympathetic efferent signals to muscle spindles and overexertion can produce a spasm in muscle spindle intrafusal fibers, increasing muscle spindle capsule pressure and causing myofascial pain.

Jack, a 42-year-old software developer, came to the biofeedback clinic with chronic neck and shoulder pain that flared whenever work deadlines approached. Surface EMG revealed elevated resting muscle tension in his upper trapezius, with marked asymmetry between left and right sides. Using EMG biofeedback combined with diaphragmatic breathing training, Marcus learned to recognize early signs of tension buildup and apply relaxation techniques before trigger points became fully activated. After 12 sessions, his resting trapezius EMG levels decreased by 40%, pain episodes became less frequent, and he reported using fewer analgesics. The key insight was that his pain was not simply "muscle tension" but involved sympathetic activation that he could learn to modulate.

The Spindle Hypothesis: A neurophysiological model proposes that painful trigger points develop when sustained fusimotor activation and local accumulation of inflammatory products within the closed spindle capsule sensitize intrafusal group III and IV afferents. These chemosensitive fibers are capable of signaling pain, and their activation creates the taut bands and referred pain patterns characteristic of myofascial pain syndrome (Partanen et al., 2010; Sas et al., 2023).

Check Your Understanding

- What distinguishes an active trigger point from a latent trigger point?

- How might the sympathetic nervous system contribute to trigger point pain?

- What evidence suggests that muscle spindles may be involved in muscle pain?

Pain Pathways: Roads to the Brain

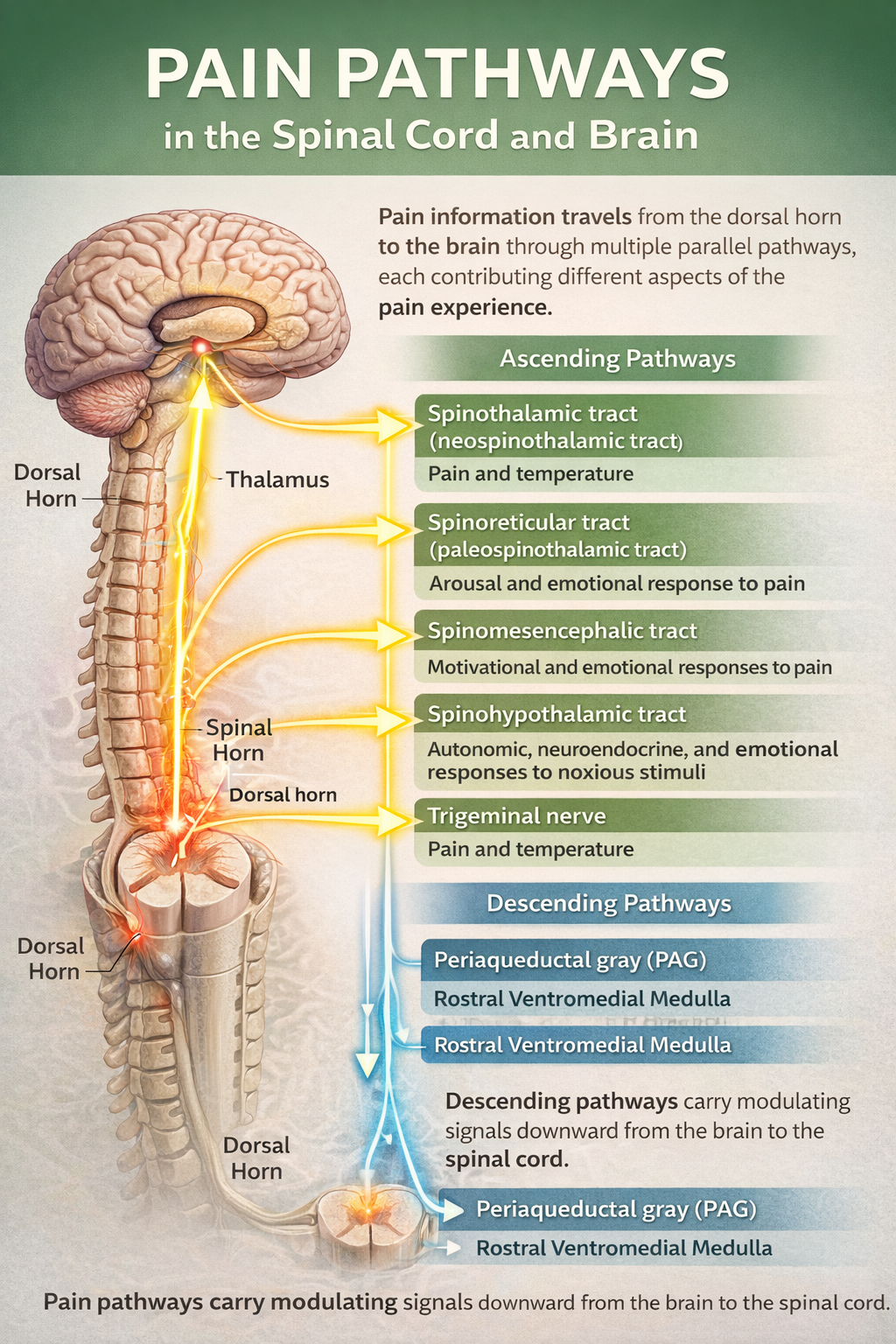

Pain information travels from the dorsal horn to the brain through multiple parallel pathways, each contributing different aspects of the pain experience. These ascending pathways carry information upward, while descending pathways carry modulating signals downward from the brain to the spinal cord.

The Ascending Pathways

The dorsal column-medial lemniscal pathway carries precise information about touch, vibration, and proprioception. Though not primarily a pain pathway, its large A-beta fibers play a crucial role in pain modulation through the Gate Control mechanism.

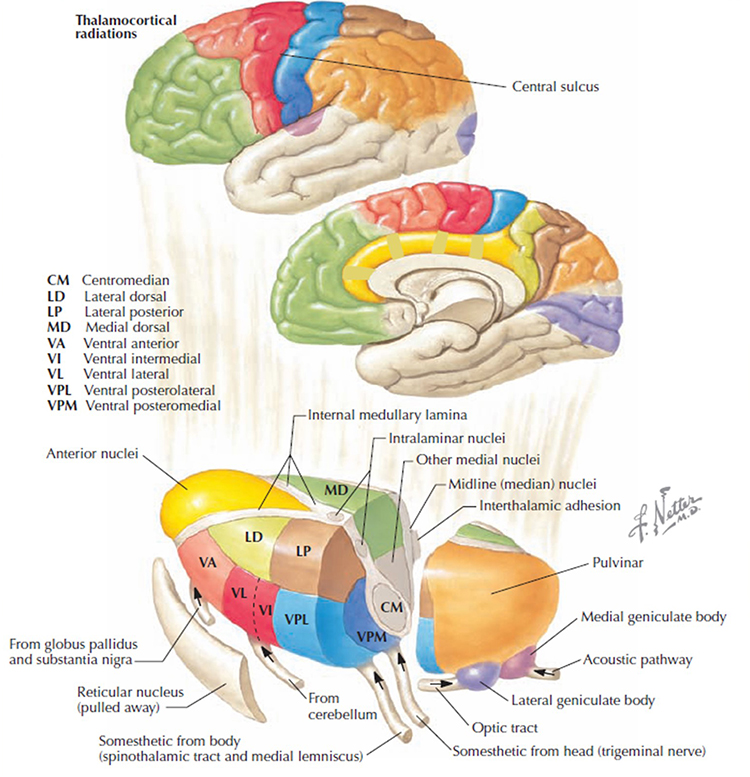

The anterolateral system is the main highway for pain transmission and includes four distinct tracts. The spinothalamic tract projects to the thalamus and then to the somatosensory cortex, providing information about pain location, intensity, and quality. The spinoreticular tract connects to the reticular formation in the brainstem, contributing to arousal and the autonomic responses that accompany pain. The spinomesencephalic tract reaches the periaqueductal gray (PAG), a crucial structure for descending pain modulation. The spinohypothalamic tract targets the hypothalamus, triggering stress hormone release and other homeostatic responses to pain (Bear et al., 2020; Breedlove & Watson, 2023).

The Descending Modulatory System

The brain does not passively receive pain signals; it actively controls how much pain information reaches consciousness. The descending modulatory system originates in higher brain centers and projects down to the spinal cord, where it can either amplify or suppress pain transmission.

The periaqueductal gray (PAG) in the midbrain is the command center for descending pain control. It receives input from the frontal cortex, amygdala, and hypothalamus, integrating cognitive and emotional information with pain processing. The PAG projects to the nucleus raphe magnus (NRM) in the medulla, which releases serotonin onto dorsal horn neurons. The nucleus reticularis paragigantocellularis (NRPG) and locus coeruleus contribute norepinephrine to this modulatory system. Together, these structures can dramatically reduce pain transmission, explaining phenomena like stress-induced analgesia and placebo effects (Melzack, 1999; Woolf, 2022).

Pain signals travel through multiple ascending pathways that convey different aspects of the pain experience. The descending modulatory system, centered on the PAG, can powerfully suppress or facilitate pain transmission. This bidirectional communication between brain and spinal cord explains why psychological factors like attention, expectation, and emotion can dramatically alter pain perception. For biofeedback practitioners, this means that training clients to modulate autonomic arousal and cognitive-emotional responses can genuinely change how their nervous systems process pain signals.

Gate Control Theory: A Revolution in Pain Science

In 1965, Ronald Melzack and Patrick Wall proposed an idea that transformed pain science: pain is not a simple wire from injury to brain, but passes through a "gate" in the spinal cord that can open or close depending on what other inputs are doing. This Gate Control Theory was radical because it insisted that the brain sends messages down to the spinal cord, so attention, emotion, and past experience can all modulate pain. It was a decisive break from the old mechanical "one wire for pain" concept (Melzack, 1996; Melzack & Wall, 1965).

How the Gate Works

The gate mechanism operates in the substantia gelatinosa, a region of the spinal cord's dorsal horn where primary afferent fibers synapse.

Large-diameter A-beta fibers carrying touch and pressure information activate inhibitory interneurons that "close" the gate, reducing pain transmission. Small-diameter C-fibers carrying pain signals inhibit these interneurons, "opening" the gate and allowing more pain information through. This explains why rubbing an injury helps: the tactile input from rubbing activates A-beta fibers that close the gate on the slower-arriving C-fiber pain signals (Braz et al., 2014; Mendell, 2014).

Critically, the gate is also influenced by descending signals from the brain. Cognitive factors like attention, expectation, and distraction, as well as emotional states like anxiety or calmness, send signals down from higher centers that modulate how easily the gate opens. This explained for the first time why soldiers wounded in battle sometimes feel no pain until after the fighting stops, and why people in chronic pain often report that stress and negative emotions make their pain worse.

Current Status: Wrong in Detail, Indispensable in Spirit

Pain scientists often say that Gate Control Theory is "wrong in detail and indispensable in spirit." Modern research has revealed that the dorsal horn is far more complex than Melzack and Wall imagined, with many different types of excitatory and inhibitory interneurons, labeled "lines" for different sensory modalities, and powerful descending systems that can both amplify and dampen pain. Clinical phenomena like tactile allodynia, where gentle touch becomes painful, do not fit the original prediction that A-beta fiber input always closes the gate (Mendell, 2014; Woolf, 2022).

Yet the core ideas have become foundational: pain is actively constructed rather than passively transmitted, spinal circuits modulate incoming signals, and top-down brain control profoundly shapes the pain experience. Researchers now build sophisticated computational models that incorporate synaptic plasticity and feedback loops to explain conditions like phantom limb pain and neuropathic pain (Ropero Peláez & Taniguchi, 2016). Clinicians still use "gate" language to explain to patients why sensory and psychological interventions can change pain.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is a direct clinical application of Gate Control Theory. By applying mild electrical stimulation through surface electrodes, TENS activates large-diameter A-beta fibers that "close the gate" on pain transmission. Biofeedback practitioners often combine TENS with relaxation training, teaching clients that they have multiple tools for modulating pain signals. The theory also explains why gentle massage, heat, and vibration can provide temporary pain relief through similar gate-closing mechanisms (Kirkpatrick et al., 2015; Treede, 2016).

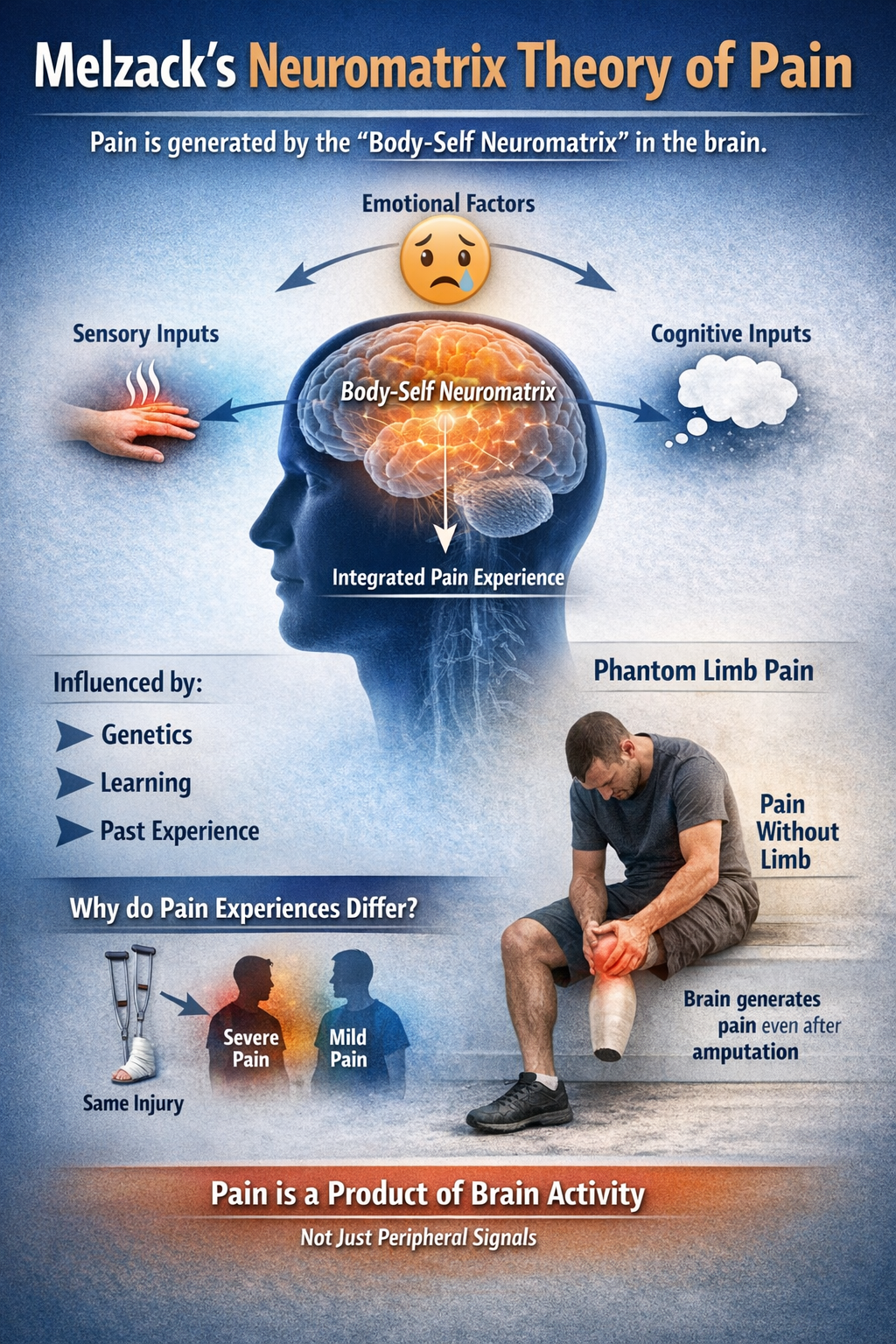

From the Gate to the Neuromatrix

Melzack himself extended Gate Control Theory into the broader neuromatrix model. This theory proposes that pain is generated by a widely distributed brain network, the "body-self neuromatrix," that integrates sensory, emotional, and cognitive inputs to create the final pain experience.

The neuromatrix is shaped by genetics, learning, and experience, explaining why two people with identical injuries can have vastly different pain experiences. This model elegantly explains phantom limb pain: the neuromatrix continues generating pain experiences in the absence of input from an amputated limb because pain is a product of brain activity, not just peripheral signals (Melzack, 1992; Melzack, 1999).

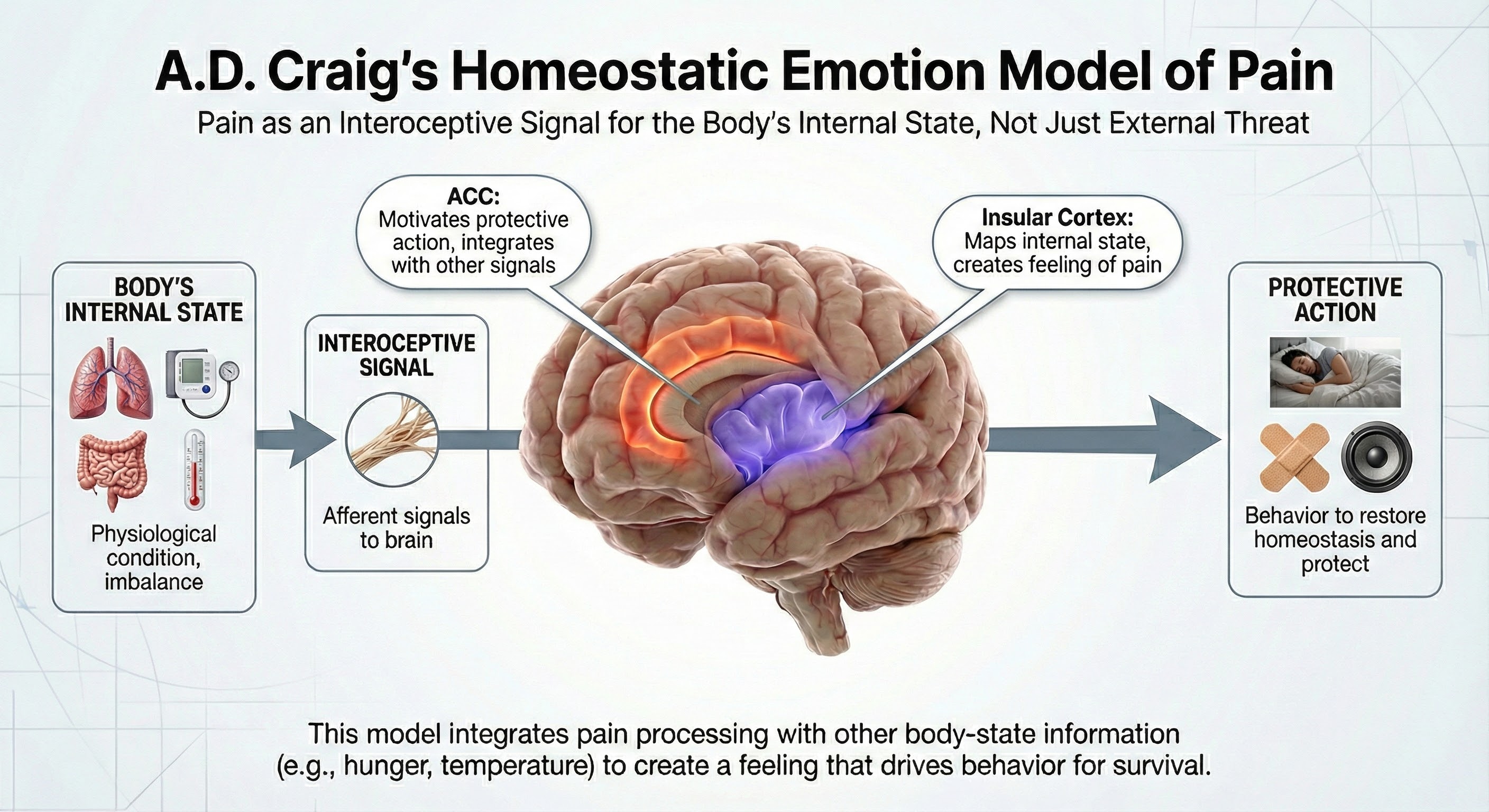

More recently, A.D. Craig proposed a homeostatic emotion model that views pain as fundamentally about the body's internal state rather than just external threats. In this view, pain is processed as an interoceptive signal through the insular cortex and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), integrating with other body-state information to create a feeling that motivates protective action (Craig, 2003).

Check Your Understanding

- According to Gate Control Theory, how do large-diameter A-beta fibers reduce pain?

- Why do pain scientists say Gate Control Theory is "wrong in detail and indispensable in spirit"?

- How does the neuromatrix model explain phantom limb pain?

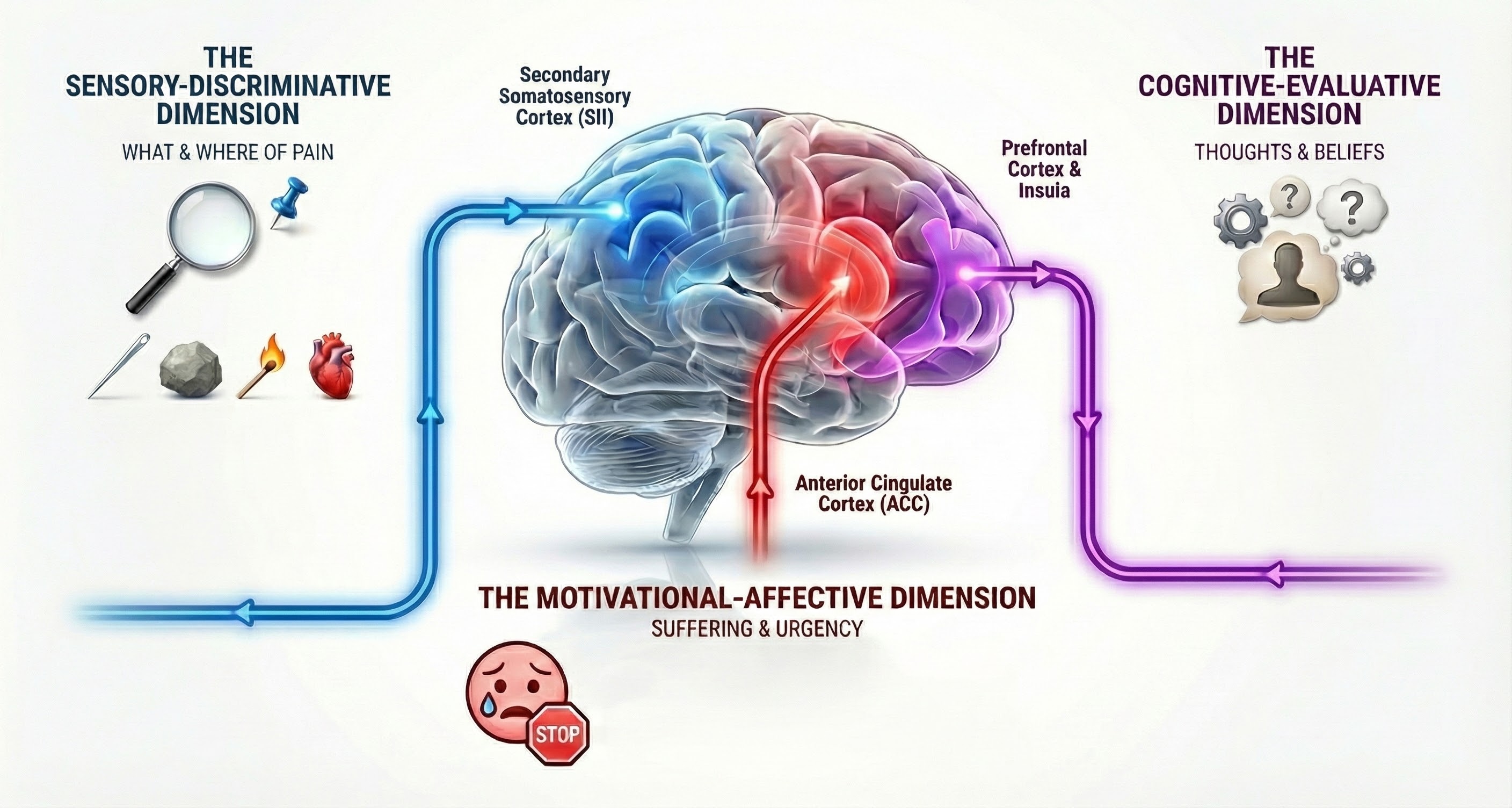

Pain Perception: Three Dimensions of Suffering

Pain is not a single experience but has at least three distinct dimensions, each processed by different brain regions. These include the sensory-discriminative, motivational-affective, and cognitive-evaluative dimensions. Understanding these dimensions helps explain why the same injury can feel so different depending on context and emotional state.

The Sensory-Discriminative Dimension

The sensory-discriminative dimension tells you where pain is located, how intense it is, and what quality it has. Is it sharp or dull? Burning or aching? Constant or throbbing? This dimension is processed primarily in the secondary somatosensory cortex (SII), which creates a detailed map of pain location and characteristics. This is the "what and where" of pain (Breedlove & Watson, 2023).

The Motivational-Affective Dimension

The motivational-affective dimension represents how unpleasant the pain is and how urgently you want it to stop. This is processed in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which evaluates the emotional significance of sensory information and generates the suffering aspect of pain. Studies of patients who have undergone cingulotomy, a surgical procedure that damages the ACC, reveal a remarkable dissociation: they can still locate and describe their pain accurately but report that it no longer bothers them (Bear et al., 2020).

The Cognitive-Evaluative Dimension

The cognitive-evaluative dimension involves how you think about pain: what you believe caused it, whether you think it will get better or worse, and how it fits into your life narrative. This dimension is processed in the prefrontal cortex and insula and is heavily influenced by prior experience, cultural factors, and expectations. It explains why pain has such different impacts depending on whether someone believes it signals a harmless muscle strain or a life-threatening illness (Craig, 2003; Lu et al., 2021).

Emotional Pain Uses Physical Pain Circuits

A remarkable series of fMRI studies by Naomi Eisenberger and colleagues demonstrated that social rejection activates the same brain regions involved in physical pain, particularly the ACC and anterior insula. When participants were excluded from a computer game by other "players" (actually a program), their brains responded as if they had been physically hurt. This research suggests that evolution co-opted physical pain circuits to process social pain, explaining why rejection and loss can feel like genuine injury and why social support can reduce physical pain (Eisenberger et al., 2003).

Check Your Understanding

- What are the three dimensions of pain perception and which brain regions process each?

- What does cingulotomy reveal about the role of the ACC in pain?

- How does Eisenberger's research on social rejection relate to physical pain?

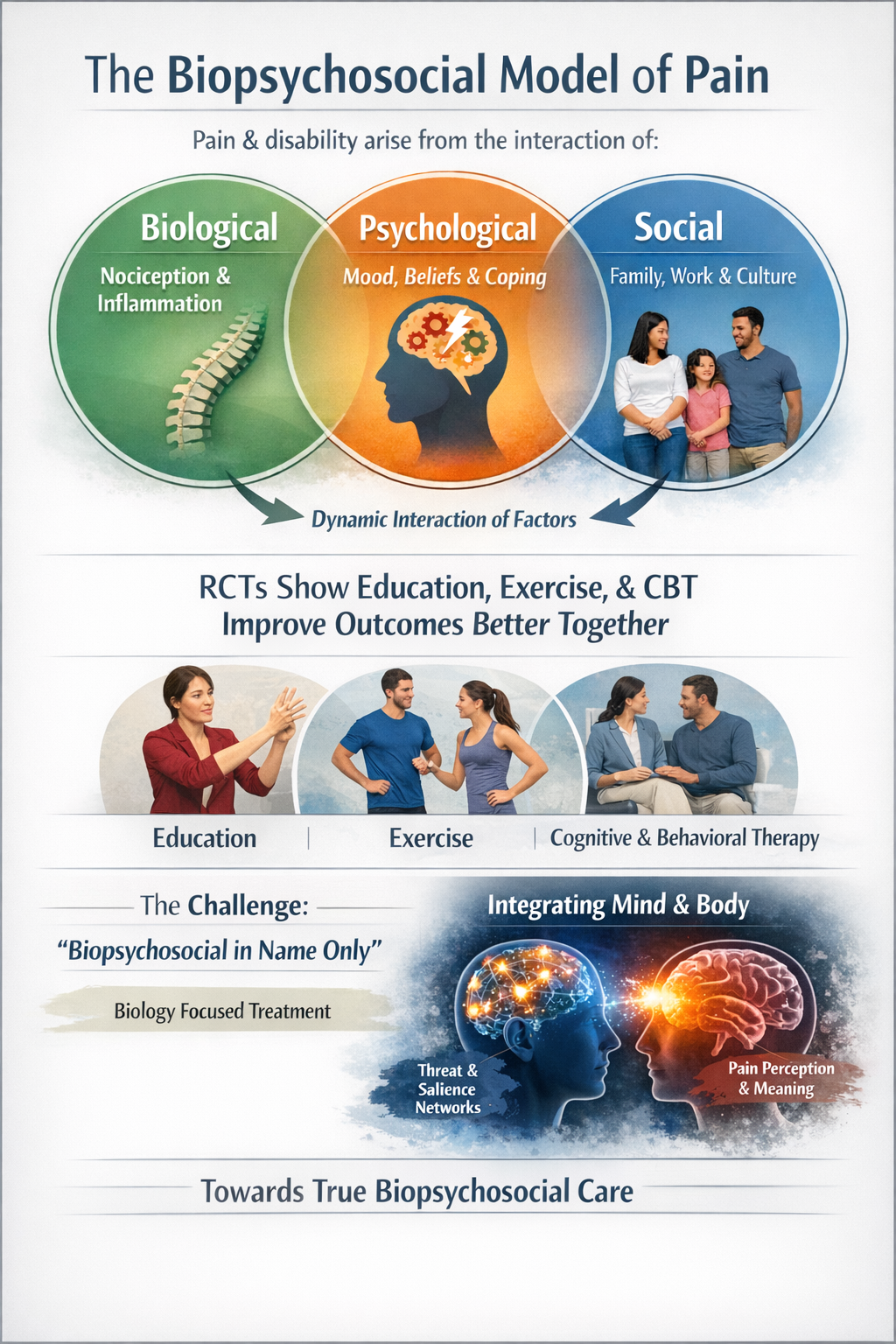

Pain Models: From Biology to Behavior

Modern pain science has moved far beyond "find the damage, fix the damage." Two influential frameworks guide contemporary understanding and treatment: the biopsychosocial model and the fear-avoidance model.

The Biopsychosocial Model

The biopsychosocial model proposes that pain and disability emerge from the dynamic interaction of biological factors like nociception and inflammation, psychological factors like mood, beliefs, and coping strategies, and social factors like family, work, and culture. This model arose as a reaction against purely biomedical approaches that treated pain as simply a signal from damaged tissue. Multiple randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that treatments combining education, exercise, and psychological strategies improve outcomes better than any single-modality approach (Delgado-Sanchez et al., 2023; Dunn et al., 2024; Meints & Edwards, 2018).

The biopsychosocial model is now widely endorsed but often under-applied. Critics note that many clinicians pay lip service to "biopsychosocial" while still focusing primarily on biology, treating psychological and social factors as secondary considerations. The current trend is toward genuine integration, using brain networks that process threat and salience as a bridge between nociception and meaning (Dong & Bäckryd, 2023; Sullivan et al., 2022).

The Fear-Avoidance Model

The fear-avoidance model describes a specific psychological pathway from acute injury to chronic disability. When someone experiences an episode of pain, they face a fork in the road. The adaptive path involves interpreting pain as manageable, staying active, and gradually recovering. The maladaptive path involves catastrophizing ("this pain means my back is ruined"), fear of movement, hypervigilance, and avoidance of activity. This avoidance leads to deconditioning, depression, disability, and paradoxically, even more pain. The vicious cycle becomes self-perpetuating (Crombez et al., 2012; Vlaeyen & Linton, 2000).

Multiple meta-analyses have validated core predictions of this model. Across tens of thousands of patients, higher pain catastrophizing, fear of pain, and pain vigilance show medium to large associations with depression, anxiety, and pain-related disability. Fear-avoidance beliefs also prospectively predict who is more likely to develop chronic pain and ongoing disability. Treatments that specifically target fear and avoidance, like graded exposure therapy and cognitive-behavioral approaches, effectively reduce disability in highly fear-avoidant patients (Markfelder & Pauli, 2020; Rogers & Farris, 2022; Zale et al., 2013).

Patricia, a 55-year-old office manager, developed low back pain after lifting boxes during an office move. Despite imaging showing only mild degenerative changes, she became convinced that any movement would worsen her spine. She stopped exercising, asked her husband to carry anything heavier than a coffee cup, and began missing work. Within six months, her pain had spread to her hips and shoulders, her sleep was disrupted, and she met criteria for depression. Using biofeedback-assisted relaxation combined with graded activity exposure, her treatment focused not on "fixing" her spine but on breaking the fear-avoidance cycle. Surface EMG revealed that her back muscles tensed dramatically whenever she thought about bending, even before any movement occurred. By learning to recognize and reduce this anticipatory muscle bracing while gradually resuming activities she had feared, Patricia reclaimed her life over the course of four months.

Predictive Processing and Fear-Avoidance: Contemporary updates to the fear-avoidance model integrate predictive brain theories. The brain does not passively wait for pain signals but actively predicts them based on prior experience. When someone with chronic pain approaches an activity they have learned to associate with pain, their brain generates a prediction of pain that can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. The amygdala, insula, and prefrontal cortex show hyperactivation in fear-avoidant patients when they merely anticipate movement. Treatments that provide safe, positive movement experiences gradually update these predictions (Meulders, 2019; Varangot-Reille et al., 2024).

The Dynamic Pain Connectome

Recent neuroimaging research has revealed that chronic pain involves not just changes in individual brain regions but alterations in the dynamic interactions between large-scale brain networks. The dynamic pain connectome model proposes that pain emerges from fluctuating communication between the salience network, which detects and prioritizes important signals, and the default mode network, which is active during self-referential thought and mind-wandering.

In chronic pain, these networks become abnormally coupled, so the brain becomes stuck in a pain-focused state even during rest. This helps explain the intrusive, attention-capturing nature of chronic pain and points toward treatments that might "unstick" these pathological network dynamics (Kucyi & Davis, 2015; Kucyi et al., 2018).

.jpg)

The biopsychosocial model provides the framework for understanding chronic pain as emerging from the interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors. The fear-avoidance model offers a testable psychological pathway explaining how acute pain becomes chronic disability. Both models are well-supported and continue to evolve. For biofeedback practitioners, they emphasize that effective treatment must address not just muscle tension or autonomic arousal but the cognitive and emotional factors that maintain pain and disability.

Inflammation: Friend and Foe in Pain

Pain and inflammation are so tightly linked that "it hurts" is practically the body's way of saying "something is inflamed." But contemporary pain science reveals a more nuanced picture: inflammation is not only a driver of pain but also essential for pain resolution. Blocking it too aggressively or at the wrong time may actually help pain persist.

Acute Inflammation: The Protective Response

Acute inflammation is the body's protective reaction to injury or infection, marked by the classic signs of redness, heat, swelling, pain, and loss of function. Immune cells rush in, clear debris and pathogens, and release chemical mediators such as prostaglandins, cytokines, and chemokines. These mediators sensitize nociceptors, lowering their activation thresholds so that you rest the injured area and avoid further harm. This is adaptive inflammatory pain (Cook et al., 2018; Matsuda et al., 2018; Pinho-Ribeiro et al., 2016).

Neuroinflammation: When the Nervous System Catches Fire

Beyond swollen joints and hot skin, neuroinflammation within the peripheral and central nervous systems is now recognized as a core mechanism in neuropathic and chronic pain. After nerve injury, immune cells like macrophages and T cells gather around injured nerves and in dorsal root ganglia, while microglia and astrocytes in the spinal cord and brain become activated. These cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that change how neurons fire, promoting peripheral and central sensitization so that normal input now produces exaggerated or prolonged pain (Ellis & Bennett, 2013; Ji et al., 2018; Sommer et al., 2017).

Key inflammatory mediators include tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6). These cytokines can lower nociceptor thresholds indirectly by triggering other mediators or directly by binding to receptors on sensory neurons, altering ion channel function so cells fire more easily (Cook et al., 2018; Fang et al., 2023; Vanderwall & Milligan, 2019).

The Surprising Role of Inflammation in Pain Resolution

Perhaps the most eye-catching recent finding is that a strong, well-timed acute inflammatory response may actually protect against chronic pain. In a large study of people with acute low back pain followed for three months, individuals whose pain resolved showed a robust, transient neutrophil-driven inflammatory response in blood, with thousands of gene expression changes over time. Those who went on to develop chronic pain showed almost no such dynamic immune response (Parisien et al., 2022).

Even more striking, in animal experiments, early use of NSAIDs or steroids provided short-term relief but prolonged pain duration. Depleting neutrophils delayed resolution, while giving back neutrophils or their signaling proteins prevented long-lasting pain. Analysis of UK Biobank data found that people taking NSAIDs for acute back pain had a higher risk of persistent pain. These results hint that "putting out the fire" immediately with potent anti-inflammatories may interfere with the normal resolution program (Parisien et al., 2022).

Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators

Inflammation does not simply fade away; it is actively turned off by specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs). These endogenous lipid molecules, including resolvins, protectins, maresins, and lipoxins, actively shut down inflammatory processes and promote tissue repair. In animal models, SPMs reduce neuroinflammation and show powerful anti-hyperalgesic effects. This has sparked interest in therapies that enhance the body's natural resolution mechanisms rather than simply suppressing inflammation (Fang et al., 2023; Fiore et al., 2023; Leuti et al., 2021).

Check Your Understanding

- How does neuroinflammation differ from tissue inflammation, and why does it matter for chronic pain?

- What surprising finding emerged from research on early NSAID use for acute back pain?

- What are specialized pro-resolving mediators and what role do they play in pain?

Acute Versus Chronic Pain: Two Different Animals

Acute and chronic pain are now understood less as points on a timeline and more as different modes of nervous system operation. Acute pain is like a fire alarm; chronic pain is more like a smoke detector stuck on high sensitivity, sometimes long after the fire is out.

Acute Pain: The Alarm System

Acute pain usually follows obvious tissue injury or noxious stimulation. Nociceptors respond to mechanical, thermal, or chemical threats and send signals through the spinal cord to the brain, where they are perceived as pain and drive protective reflexes. In most people, as tissue heals and inflammation resolves, this alarm system quiets down and sensory processing returns to baseline. Acute pain is adaptive: it makes you pull your hand from a hot stove, rest a broken bone, or favor an injured leg (Bell, 2018; Zhang et al., 2025).

Chronic Pain: The System Transformed

Chronic pain is usually defined as pain lasting beyond three months, or beyond normal tissue healing time. Instead of being just "more acute pain," chronic pain involves durable changes in peripheral nerves, spinal cord, and brain. Peripheral and central sensitization, neuroinflammation, altered synaptic strength, and reorganization of brain networks encoding sensation, emotion, and motivation all contribute (Chapman & Vierck, 2017; Kuner & Kuner, 2020; Yang & Chang, 2019).

Glial cells become activated and release cytokines that keep neurons hyperexcitable. Genes related to ion channels and neurotransmitters are epigenetically tuned toward easier firing. Descending modulatory circuits from the brainstem and limbic system lose some of their inhibitory "brakes" and can even become facilitatory. The result is hyperalgesia (stronger pain to the same stimulus), allodynia (pain to normally non-painful touch), and spontaneous pain without clear triggers (Kuner & Kuner, 2020; Nasir et al., 2025).

Nociplastic Pain: A New Category

The older term "functional pain syndromes" referred to conditions like fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic headaches where scans and tests looked normal but patients clearly hurt. That label often carried a hidden judgment: if no tissue damage could be found, maybe the pain was "all in the head."

Contemporary pain science has reframed this with the concept of nociplastic pain: pain arising from altered nociceptive processing without clear ongoing tissue injury or nerve damage. The nervous system itself becomes hypersensitive and amplifies signals. Patients show widespread tenderness, allodynia, fluctuating symptoms, strong links with sleep and mood problems, and frequent overlap across diagnoses. Rather than implying "no cause," this term emphasizes a biopsychosocial condition involving brain and spinal cord amplification interacting with genetics, stress, trauma, expectations, and behavior (Arendt-Nielsen et al., 2018; Popkirov et al., 2020; Yoo & Kim, 2024).

Brain Changes in Chronic Pain

Chronic pain literally reshapes the brain. Imaging studies by Apkarian and colleagues found that people with chronic back pain show decreased gray matter density in the prefrontal cortex and thalamus, with losses equivalent to 10-20 years of normal aging. They also showed deficits on the Iowa Gambling Test, suggesting impaired decision-making. Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), one of the most severe chronic pain conditions, is associated with dramatic cortical reorganization and changes in body representation (Apkarian et al., 2004; Melton, 2004).

Acute pain is a protective alarm that normally resolves with tissue healing. Chronic pain represents a transformation of nervous system function, involving peripheral and central sensitization, neuroinflammation, and brain reorganization. Nociplastic pain describes conditions where the nervous system itself generates and amplifies pain without ongoing tissue pathology. For biofeedback practitioners, this means that chronic pain requires approaches that address nervous system dysregulation rather than simply treating a nonexistent injury.

Check Your Understanding

- What is the difference between acute pain and chronic pain in terms of nervous system function?

- What is nociplastic pain and how does this concept differ from the older idea of "functional pain"?

- What brain changes have been documented in people with chronic pain?

Pain and the Autonomic Nervous System

Pain does not stay contained in the body part that hurts. It ripples through the autonomic nervous system, shifting heart rate, heart rate variability, breathing, hormones, and sleep. Understanding these connections is essential for biofeedback practitioners because autonomic dysregulation is both a consequence and a potential maintaining factor of chronic pain.

.jpg)

Pain and Heart Rate Variability

When something hurts, the body shifts toward a fight-or-flight state. Experimental pain reliably increases markers of sympathetic activation: heart rate rises, blood vessels constrict, and heart rate variability (HRV) patterns show reduced vagal (parasympathetic) influence. In large reviews of experimental pain studies, painful heat, cold, pressure, and electrical shocks all produced a shift toward sympathetic dominance and vagal withdrawal, regardless of how the pain was induced. The intervals between heartbeats become more rigid and less flexible, a sign the body is in defensive mode (Forte et al., 2022; Koenig et al., 2014; Tracy et al., 2016).

In chronic pain, this autonomic shift becomes a long-term trait rather than a short-term reaction. Across many conditions including fibromyalgia, musculoskeletal pain, and temporomandibular disorders, meta-analytic evidence shows reduced high-frequency HRV, indicating impaired vagal control. This blunted HRV is seen in adults and, more tentatively, in children and adolescents with chronic primary pain (Gibler & Jastrowski Mano, 2021; Koenig et al., 2016; Tracy et al., 2016).

HRV biofeedback is a direct clinical application of the pain-autonomic connection. By training clients to increase respiratory sinus arrhythmia through paced breathing at approximately six breaths per minute, practitioners can enhance vagal tone and shift autonomic balance away from sympathetic dominance. Multiple studies show that pain interventions that successfully reduce symptoms often produce increases in vagally-mediated HRV and a lower LF/HF ratio, essentially a shift back toward calmer autonomic regulation. Exercise training in chronic musculoskeletal pain also tends to improve HRV over weeks (Daibes et al., 2025; Meus et al., 2025; Adler-Neal et al., 2020).

Pain and Respiration

Breathing changes with pain. Systematic reviews conclude that acute pain generally increases respiratory rate, flow, and tidal volume. You breathe faster and more forcefully in parallel with sympathetic activation. This makes physiological sense as preparation for fighting or fleeing from whatever caused the injury (Jafari et al., 2017; Kyle & McNeil, 2014).

Slow, deliberate breathing can shift this pattern. Paced slow breathing at around six breaths per minute reliably raises vagally-mediated HRV, even if its direct effect on pain intensity is small or inconsistent in the short term. This suggests that controlled breathing is a behavioral lever for influencing autonomic state, which may matter more for coping and long-term regulation than for instant analgesia (Gholamrezaei et al., 2021).

Pain and Electrodermal Activity

Electrodermal activity (EDA), also known as galvanic skin response or skin conductance, reflects sympathetic nervous system activation of sweat glands. Because sweat glands are innervated solely by sympathetic fibers without parasympathetic input, EDA provides a pure measure of sympathetic arousal. Pain reliably increases EDA, with the amplitude of skin conductance responses correlating with stimulus intensity. This relationship has made EDA a popular research tool for objective pain assessment (Bari et al., 2018; Posada-Quintero et al., 2021).

For biofeedback applications, EDA provides real-time feedback about sympathetic arousal that clients can learn to modulate. As clients practice relaxation techniques, they can observe their skin conductance levels decrease, providing immediate reinforcement for successful self-regulation. EDA biofeedback has been used effectively for anxiety, panic disorders, and stress-related conditions, all of which frequently co-occur with chronic pain (Critchley, 2002).

EDA in Pain Research: Recent advances in wearable EDA sensors have enabled real-time pain monitoring outside the laboratory. Research using differential characteristics of EDA signals, including spectral analysis and phasic response patterns, shows promise for distinguishing between different pain intensities. The sensitivity of EDA to sympathetic activation makes it particularly useful for detecting the emotional and stress components of pain, which may not correlate perfectly with sensory intensity (Posada-Quintero et al., 2021).

Pain and Sleep

Sleep is where pain and autonomic systems intersect most dramatically. Chronic pain and poor sleep form a vicious cycle: more pain predicts worse sleep, and fragmented or short sleep predicts higher next-day pain. Autonomic imbalance appears to be one of the links. In systemic sclerosis, higher pain scores were associated with worse sleep quality and higher sympathetic predominance at rest. Chronic temporomandibular disorder patients showed strong correlations between nighttime pain intensity and the amplitude of nocturnal autonomic cycling (Carandina et al., 2021; Nickel et al., 2025).

Healthy sleepers normally show a parasympathetic "rise" at night, with higher HRV and lower heart rate. Chronic pain appears to blunt or distort this pattern, with overall lower HRV and relative sympathetic bias during sleep, especially in more symptomatic patients. This may explain why some people with chronic pain wake feeling unrefreshed even if they spent enough hours in bed: their autonomic system never fully downshifts (Carandina et al., 2021; Tracy et al., 2016).

Pain and Metabolic Function

Chronic pain is increasingly linked to metabolic dysregulation. Imaging studies show that chronic pain conditions such as migraine and neuropathic pain are associated with altered glucose metabolism in brain regions that process both pain and emotion. The sympathetic activation and stress hormones that accompany pain episodes raise blood glucose, and epidemiologic research links chronic pain with higher rates of metabolic dysfunction, though this relationship is likely bidirectional and influenced by inactivity, sleep disruption, and mood (Ma et al., 2025; Yeater et al., 2022).

Pain produces widespread autonomic changes including increased heart rate, decreased HRV, faster breathing, elevated skin conductance, and disrupted sleep. In chronic pain, these changes become persistent traits rather than temporary reactions. Biofeedback training targeting HRV, respiration, and EDA can help restore autonomic flexibility, potentially interrupting the vicious cycles that maintain chronic pain. The autonomic nervous system is not just a downstream consequence of pain but a potential therapeutic target.

Check Your Understanding

- How does acute pain affect heart rate variability, and what does this indicate about autonomic balance?

- Why is electrodermal activity considered a "pure" measure of sympathetic arousal?

- What is the relationship between chronic pain and sleep, and what role does the autonomic nervous system play?

Cutting-Edge Topics in Pain Research

Glial Signaling Spreads Pain Widely

Even more remarkably, activated glial cells release signaling molecules like D-serine and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) that diffuse through spinal cord tissue, sensitizing neurons far beyond the original injury site. This "gliogenic long-term potentiation" helps explain why chronic pain often spreads beyond its initial location and affects body regions that were never injured (Kronschläger et al., 2016).

Sodium Channel Therapeutics

Pain signals depend on voltage-gated sodium channels, particularly Nav1.7 and Nav1.8, which act like molecular switches that fire pain neurons. Think of Nav1.7 as the "fuse" that initiates the pain signal and Nav1.8 as the "firecracker" that amplifies it. In 2024, the FDA approved suzetrigine, the first selective Nav1.8 blocker for moderate-to-severe acute pain. Unlike opioids, suzetrigine targets only peripheral pain neurons without affecting the brain's reward circuits, offering effective pain relief without addiction risk. People born with mutations that disable Nav1.7 cannot feel pain at all, making this channel a prime therapeutic target (Duan et al., 2017; Treede, 2016).

The Insula as Integration Hub

The insular cortex has emerged as a central hub for integrating sensory, emotional, and cognitive aspects of pain. The posterior insula receives direct sensory input about body states, while the anterior insula integrates this information with emotional and cognitive context to generate the subjective feeling of pain. This helps explain why pain is so tightly linked to emotions: they share common neural real estate (Lu et al., 2021; Menon & Uddin, 2010).

The MC1R Gene and Pain Sensitivity

People with red hair carry variants of the melanocortin-1 receptor (MC1R) gene that affect pain processing. They require approximately 20% more anesthesia for surgical procedures and show altered sensitivity to various pain stimuli. This genetic variation illustrates how individual differences in pain perception have biological underpinnings (Mogil et al., 2005).

Low-Grade Systemic Inflammation and Chronic Pain

A chronic, smoldering, non-infectious inflammatory state tied to obesity, aging, stress, and metabolic disease is increasingly proposed as a predisposing factor for chronic pain. This low-grade systemic inflammation may prime neuroimmune circuits so that later insults are more likely to lead to persistent pain. It also connects lifestyle factors to pain biology and suggests that exercise, weight management, and sleep, which reduce systemic inflammation, may work partly through neuroimmune pathways (Wood et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2021).

Summary

Pain is far more than a simple alarm system. It involves complex interactions from nociceptor activation through spinal cord processing to distributed brain networks, all modulated by the autonomic nervous system. The Gate Control Theory revolutionized our understanding by showing that pain is actively constructed and modulated rather than passively transmitted. Chronic pain represents a fundamental transformation of nervous system function, not just prolonged acute pain, involving central sensitization, neuroinflammation, and altered brain connectivity. Modern pain models, including the biopsychosocial and fear-avoidance frameworks, emphasize that effective treatment must address biological, psychological, and social factors together. Inflammation plays a dual role as both driver and resolver of pain. The autonomic changes accompanying pain, including altered HRV, respiration, EDA, and sleep, are both consequences of and contributors to chronic pain states. For biofeedback practitioners, this comprehensive understanding provides multiple targets for intervention: teaching clients to modulate muscle tension, autonomic arousal, breathing patterns, and the cognitive-emotional responses that maintain pain and disability.

Test Yourself

Click on the ClassMarker logo to take 10-question tests over this unit without an exam password.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, explain why treating chronic pain as if it were acute can be counterproductive. What is the clinical relevance of the fear-avoidance model and how might a biofeedback practitioner address catastrophic thinking about pain? How do autonomic measures like HRV and EDA provide both assessment and treatment targets in pain management?

Glossary

A-beta fibers: Large, fast, myelinated sensory fibers that carry touch and pressure information and help "close the gate" on pain transmission by activating inhibitory circuits in the spinal cord.

A-delta fibers: Thin, lightly myelinated sensory fibers that conduct sharp, well-localized "first pain" at moderate speeds (5-30 m/s).

acute pain: Recent-onset, short-lived pain tied to tissue injury or noxious stimulation, serving as a protective alarm that normally resolves with healing.

allodynia: A condition in which normally non-painful stimuli like light touch become painful, often resulting from central sensitization and changes in spinal cord processing.

anterolateral system: The main ascending pathway for pain transmission, including the spinothalamic, spinoreticular, spinomesencephalic, and spinohypothalamic tracts.

autonomic nervous system (ANS): The involuntary control system regulating heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, and other visceral functions through its sympathetic and parasympathetic branches.

biopsychosocial model: A framework proposing that pain and disability emerge from the dynamic interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors.

bradykinin: One of the most potent pain-producing chemicals, released during tissue damage, that directly activates and sensitizes nociceptors.

C-fibers: The thinnest, slowest sensory fibers (0.5-2 m/s), lacking myelin, that carry dull, aching, poorly localized "second pain."

catastrophizing: A maladaptive cognitive pattern characterized by rumination, magnification, and helplessness regarding pain, strongly associated with poor outcomes.

central sensitization: A heightened responsiveness of spinal cord and brain neurons to normal or weak inputs, leading to amplified pain and symptoms like allodynia and hyperalgesia.

chemoreceptors: Nociceptors that respond to chemical changes in tissue, including inflammatory mediators released during injury.

chronic pain: Pain persisting for at least three months or beyond expected healing time, often maintained by central sensitization, neuroinflammation, and brain reorganization.

cluster firing: Synchronized bursts of activity in groups of sensory neurons that may underlie spontaneous pain in chronic pain conditions.

cognitive-evaluative dimension: The aspect of pain involving thoughts, beliefs, and interpretations about pain's meaning and implications, processed in prefrontal cortex.

complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS): A severe chronic pain condition characterized by autonomic dysfunction, motor changes, and cortical reorganization following injury.

cytokines: Immune signaling proteins such as TNF, IL-1β, and IL-6 that coordinate inflammation and can sensitize nociceptors and central neurons.

descending modulatory system: Brain pathways projecting down to the spinal cord that can either amplify or suppress pain transmission.

dorsal horn: The back portion of the spinal cord gray matter where sensory afferents first synapse and where the "gate" of Gate Control Theory is located.

dynamic pain connectome: A model proposing that chronic pain emerges from altered dynamic interactions between large-scale brain networks, particularly the salience and default mode networks.

electrodermal activity (EDA): Changes in the electrical properties of skin due to sweat gland activity, providing a pure measure of sympathetic nervous system arousal.

fear-avoidance model: A psychological model describing how catastrophizing and fear of movement lead to activity avoidance, deconditioning, disability, and paradoxically more pain.

free nerve endings: Naked sensory nerve terminals that detect potentially damaging stimuli, lacking the specialized capsules of touch receptors.

Gate Control Theory: Melzack and Wall's influential theory that a "gate" in the spinal cord modulates pain transmission based on the balance of large and small fiber input plus descending brain signals.

Gevirtz’s mediational model of muscle pain: the perspective that lack of assertiveness and resultant worry each trigger sympathetic activation. Increased sympathetic efferent signals to muscle spindles and overexertion can produce a spasm in the muscle spindle's intrafusal fibers, increasing muscle spindle capsule pressure and causing myofascial pain.

glial cells: Non-neuronal support cells in the nervous system, including microglia and astrocytes, that become activated in chronic pain and release inflammatory mediators.

heart rate variability (HRV): Beat-to-beat variation in the time between heartbeats, reflecting autonomic nervous system flexibility; reduced in chronic pain.

homeostatic emotion: Craig's theory that pain functions as an interoceptive signal about body state, processed through the insula and anterior cingulate cortex.

hyperalgesia: An exaggerated pain response to a normally painful stimulus, such as a pinprick hurting much more than expected.

interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β): A pro-inflammatory cytokine that sensitizes nociceptors and central neurons, contributing to pain amplification.

interleukin-6 (IL-6): A cytokine with both pro- and anti-inflammatory properties involved in pain modulation and the transition to chronic pain.

locus coeruleus: A brainstem nucleus that releases norepinephrine as part of the descending pain modulatory system.

local twitch response: A brief, involuntary contraction of a taut muscle band elicited by palpation or needling of a trigger point.

mechanoreceptors: Nociceptors that respond to intense mechanical pressure capable of causing tissue damage.

microglia: Resident immune cells of the central nervous system that become activated after injury and release inflammatory mediators contributing to central sensitization.

motivational-affective dimension: The unpleasantness and emotional suffering aspect of pain, processed primarily in the anterior cingulate cortex.

muscle spindle: A specialized sensory organ within muscle that detects stretch and length changes; now also implicated in muscle pain and modulated by sympathetic innervation.

myofascial trigger point: A hyperirritable spot in a taut band of skeletal muscle that is painful on palpation and can produce referred pain.

Nav1.7: a sodium channel that acts as a "fuse," amplifying small nerve signals but not triggering full action potentials.

Nav1.8:a sodium channel that functions as a "firecracker," generating most of the electrical current needed for neuronal firing.

nerve growth factor (NGF): A neurotrophic factor that maintains nociceptor health but also increases their sensitivity during inflammation.

neuroinflammation: Inflammation within the peripheral or central nervous system, involving activation of glial and immune cells and release of inflammatory mediators.

neuromatrix model: Melzack's theory that pain is generated by a widely distributed brain network integrating sensory, emotional, and cognitive inputs.

nociceptor: A specialized sensory receptor that responds to potentially damaging stimuli and initiates the pain experience.

nociplastic pain: Pain arising from altered nociceptive processing without clear ongoing tissue injury or nerve damage, replacing older "functional pain" terminology.

nucleus raphe magnus (NRM): A brainstem nucleus that releases serotonin as part of the descending pain modulatory system.

periaqueductal gray (PAG): A midbrain structure that serves as the command center for descending pain modulation.

peripheral sensitization: Increased responsiveness and lowered thresholds of nociceptors in injured or inflamed tissue.

phantom limb pain: Pain perceived in a body part that has been amputated, explained by the neuromatrix model as continued activity in pain-generating brain networks.

polymodal nociceptor: A nociceptor that responds to multiple types of potentially damaging stimuli (mechanical, thermal, and chemical).

prostaglandins: Lipid compounds released during inflammation that sensitize nociceptors to other pain-producing chemicals; blocked by NSAIDs.

referred pain: Pain perceived at a location distant from its actual source, due to convergence of visceral and somatic afferents onto shared spinal neurons.

salience network: A brain network that detects and prioritizes important stimuli; shows altered connectivity with the default mode network in chronic pain.

sensory-discriminative dimension: The aspect of pain concerning location, intensity, and quality, processed primarily in the somatosensory cortex.

specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs): Endogenous lipid molecules (resolvins, protectins, maresins, lipoxins) that actively turn off inflammation and promote pain resolution.

spinothalamic tract: The main ascending pathway carrying pain and temperature information to the thalamus and somatosensory cortex.

substance P: A neuropeptide released by nociceptors that causes vasodilation and contributes to neurogenic inflammation.

substantia gelatinosa: A region of the dorsal horn containing interneurons that modulate pain transmission; the location of the "gate" in Gate Control Theory.

Suzetrigine: The first FDA-approved selective Nav1.8 sodium channel blocker for acute pain, representing a new class of non-opioid analgesics.

sympathetic nervous system: The "fight-or-flight" branch of the autonomic nervous system that increases heart rate, blood pressure, and sweating during stress and pain.

thermoreceptors: Nociceptors that respond to extreme temperatures capable of causing tissue damage.

tumor necrosis factor (TNF): A pro-inflammatory cytokine that sensitizes nociceptors and contributes to neuroinflammation and central sensitization.

wide dynamic range (WDR) neuron: A spinal cord neuron that responds to both light touch and painful stimuli, firing more as stimulus intensity increases.

References

Adler-Neal, A. L., Waugh, C. E., Garland, E. L., Shaltout, H. A., Diz, D. I., & Zeidan, F. (2020). The role of heart rate variability in mindfulness-based pain relief. The Journal of Pain, 21(3-4), 306-323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.07.006

Apkarian, A. V., Sosa, Y., Sonty, S., Levy, R. M., Harden, R. N., Parrish, T. B., & Gitelman, D. R. (2004). Chronic back pain is associated with decreased prefrontal and thalamic gray matter density. Journal of Neuroscience, 24(46), 10410-10415. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2541-04.2004

Arendt-Nielsen, L., Morlion, B., Perrot, S., Dahan, A., Dickenson, A., Kress, H., Wells, C., Bouhassira, D., & Drewes, A. (2018). Assessment and manifestation of central sensitisation across different chronic pain conditions. European Journal of Pain, 22(2), 216-241. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1140

Bari, D. S., Aldosky, H. Y. Y., Tronstad, C., Kalvoy, H., & Martinsen, O. G. (2018). Electrodermal activity responses for quantitative assessment of felt pain. Journal of Electrical Bioimpedance, 9(1), 52-58. https://doi.org/10.2478/joeb-2018-0010

Bear, M. F., Connors, B. W., & Paradiso, M. A. (2020). Neuroscience: Exploring the brain (4th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Bell, A. M. (2018). The neurobiology of acute pain. The Veterinary Journal, 237, 55-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2018.05.005

Braz, J., Solorzano, C., Wang, X., & Basbaum, A. I. (2014). Transmitting pain and itch messages: A contemporary view of the spinal cord circuits that generate gate control. Neuron, 82(3), 522-536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.018

Breedlove, S. M., & Watson, N. V. (2020). Biological psychology: An introduction to behavioral, cognitive, and clinical neuroscience (9th ed.). Sinauer Associates.

Carandina, A., Bellocchi, C., Dias Rodrigues, G., Beretta, L., Montano, N., & Tobaldini, E. (2021). Cardiovascular autonomic control, sleep and health related quality of life in systemic sclerosis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052355

Chapman, C. R., & Vierck, C. J. (2017). The transition of acute postoperative pain to chronic pain: An integrative overview of research on mechanisms. The Journal of Pain, 18(4), 359.e1-359.e38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2016.11.004

Cook, A. D., Christensen, A. D., Tewari, D., McMahon, S. B., & Hamilton, J. A. (2018). Immune cytokines and their receptors in inflammatory pain. Trends in Immunology, 39(3), 240-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2017.12.003

Coull, J. A., Beggs, S., Boudreau, D., Boivin, D., Tsuda, M., Inoue, K., Gravel, C., Salter, M. W., & De Koninck, Y. (2005). BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature, 438, 1017-1021. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04223

Craig, A. D. (2003). A new view of pain as a homeostatic emotion. Trends in Neurosciences, 26(6), 303-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-2236(03)00123-1

Critchley, H. D. (2002). Electrodermal responses: What happens in the brain. The Neuroscientist, 8(2), 132-142. https://doi.org/10.1177/107385840200800209

Crombez, G., Eccleston, C., Van Damme, S., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Karoly, P. (2012). Fear-avoidance model of chronic pain: The next generation. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 28(6), 475-483. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182385392

Daibes, M., Almarie, B., Andrade, M. L., de Paula Vidigal, G., Aranis, N., Gianlorenco, A. C. L., Bandeira de Mello Monteiro, C., Grover, P., Sparrow, D., & Fregni, F. (2025). Do pain and autonomic regulation share a common central compensatory pathway? A meta-analysis of HRV metrics in pain trials. NeuroSci, 6(3), 375-397. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6030025

Delgado-Sanchez, A., Brown, C., Sivan, M., Talmi, D., Charalambous, C., & Jones, A. K. P. (2023). Are we any closer to understanding how chronic pain develops? A systematic search and critical narrative review of existing chronic pain vulnerability models. Journal of Pain Research, 16, 2669-2690. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S414119

Do, T. P., Heldarskard, G. F., Kolding, L. T., Hvedstrup, J., & Schytz, H. W. (2018). Myofascial trigger points in migraine and tension-type headache. The Journal of Headache and Pain, 19(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0913-8

Dong, H. J., & Backryd, E. (2023). Teaching the biopsychosocial model of chronic pain: Whom are we talking to? Patient Education and Counseling, 111, 107696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2023.107696

Duan, B., Cheng, L., & Ma, Q. (2017). Spinal circuits transmitting mechanical pain and itch. Neuroscience Bulletin, 33(2), 186-194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-017-0103-1

Dunn, M., Rushton, A. B., Mistry, J., Soundy, A. A., & Heneghan, N. R. (2024). The biopsychosocial factors associated with development of chronic musculoskeletal pain: An umbrella review and meta-analysis of observational systematic reviews. PLOS ONE, 19(4), e0301053. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0301053

Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302, 290-292. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1089134

Ellis, A., & Bennett, D. L. H. (2013). Neuroinflammation and the generation of neuropathic pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 111(1), 26-37. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aet128

Fang, X. X., Zhai, M. N., Zhu, M., He, C., Wang, H., Wang, J., & Zhang, Z. J. (2023). Inflammation in pathogenesis of chronic pain: Foe and friend. Molecular Pain, 19, 17448069231173689. https://doi.org/10.1177/17448069231173689

Fiore, N. T., Debs, S., Hayes, J. P., Duffy, S. S., & Moalem-Taylor, G. (2023). Pain-resolving immune mechanisms in neuropathic pain. Nature Reviews Neurology, 19(3), 157-176. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-022-00769-8

Forte, G., Troisi, G., Pazzaglia, M., Pascalis, V., & Casagrande, M. (2022). Heart rate variability and pain: A systematic review. Brain Sciences, 12(2), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020153

Gholamrezaei, A., Van Diest, I., Aziz, Q., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Van Oudenhove, L. (2021). Controlled breathing and pain: Respiratory rate and inspiratory loading modulate cardiovascular autonomic responses, but not pain. Psychophysiology, 58(8), e13895. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13895

Gibler, R. C., & Jastrowski Mano, K. E. (2021). Systematic review of autonomic nervous system functioning in pediatric chronic pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 37(4), 282-298. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000900

Hellstrom, F., Roatta, S., Thunberg, J., Passatore, M., & Djupsjobacka, M. (2005). Responses of muscle spindles in feline dorsal neck muscles to electrical stimulation of the cervical sympathetic nerve. Experimental Brain Research, 165(4), 453-462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-005-2313-3

Inoue, K., & Tsuda, M. (2018). Microglia in neuropathic pain: Cellular and molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 19(3), 138-152. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2018.2

Jafari, H., Courtois, I., Van den Bergh, O., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Van Diest, I. (2017). Pain and respiration: A systematic review. PAIN, 158(6), 995-1006. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000873

Ji, R. R., Nackley, A., Huh, Y., Terrando, N., & Maixner, W. (2018). Neuroinflammation and central sensitization in chronic and widespread pain. Anesthesiology, 129(2), 343-366. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000002130

Kirkpatrick, D. R., McEntire, D., Hambsch, Z. J., Kerfeld, M. J., Smith, T. A., Reisbig, M. D., Youngblood, C. F., & Agrawal, D. K. (2015). Therapeutic basis of clinical pain modulation. Clinical and Translational Science, 8(6), 848-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12354

Koenig, J., Jarczok, M. N., Ellis, R. J., Hillecke, T. K., & Thayer, J. F. (2014). Heart rate variability and experimentally induced pain in healthy adults: A systematic review. European Journal of Pain, 18(3), 301-314. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00379.x

Koenig, J., Loerbroks, A., Jarczok, M. N., Fischer, J. E., & Thayer, J. F. (2016). Chronic pain and heart rate variability in a cross-sectional occupational sample: Evidence for impaired vagal control. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 32(3), 218-225. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000245

Kronschlager, M. T., Drdia-Schutting, R., Gassner, M., Honsek, S. D., Teuchmann, H. L., & Sandkuhler, J. (2016). Gliogenic LTP spreads widely in nociceptive pathways. Science, 354(6316), 1144-1148. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah5715

Kucyi, A., & Davis, K. D. (2015). The dynamic pain connectome. Trends in Neurosciences, 38(2), 86-95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2014.11.006

Kucyi, A., Moayedi, M., Weissman-Fogel, I., & Davis, K. D. (2018). Dynamic functional connectivity of the default mode network tracks daydreaming. NeuroImage, 100, 471-480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.044

Kuner, R., & Kuner, T. (2020). Cellular circuits in the brain and their modulation in acute and chronic pain. Physiological Reviews, 100(1), 65-102. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00040.2018

Kyle, B. N., & McNeil, D. W. (2014). Autonomic arousal and experimentally induced pain: A critical review of the literature. Pain Research and Management, 19(3), 159-167. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/536859

Leuti, A., Fava, M., Pellegrini, N., & Maccarrone, M. (2021). Role of specialized pro-resolving mediators in neuropathic pain. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 716611. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.716611

Lu, C., Yang, T., Zhao, H., Zhang, M., Meng, F., Fu, H., Xie, Y., & Xu, H. (2021). Insular cortex is critical for the perception, modulation, and chronification of pain. Neuroscience Bulletin, 32(2), 191-201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12264-016-0016-y

Ma, L., Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Sun, M., Zhu, T., & Zhou, C. (2025). The relationship between abnormal glucose metabolism and chronic pain. Cell and Bioscience, 15, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-025-01234-5

Markfelder, T., & Pauli, P. (2020). Fear of pain and pain intensity: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(5), 411-450. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000228

Matsuda, M., Huh, Y., & Ji, R. R. (2018). Roles of inflammation, neurogenic inflammation, and neuroinflammation in pain. Journal of Anesthesia, 33(1), 131-139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00540-018-2579-4

Meints, S. M., & Edwards, R. R. (2018). Evaluating psychosocial contributions to chronic pain outcomes. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 87(Pt B), 168-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.05.013

Melton, L. (2004). Aching atrophy: More than unpleasant, chronic pain shrinks the brain. Scientific American, 290(1), 22-24. PMID: 14682034

Melzack, R. (1992). Phantom limbs. Scientific American, 266(4), 120-126. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0492-120

Melzack, R. (1996). Gate control theory: On the evolution of pain concepts. Pain Forum, 5(2), 128-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1082-3174(96)80050-X

Melzack, R. (1999). From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain, 82(Suppl 1), S121-S126. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00145-1

Melzack, R., & Wall, P. D. (1965). Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science, 150, 971-979. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.150.3699.971

Mendell, L. M. (2014). Constructing and deconstructing the gate theory of pain. Pain, 155(2), 210-216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.12.010

Menon, V., & Uddin, L. Q. (2010). Saliency, switching, attention and control: A network model of insula function. Brain Structure and Function, 214, 655-667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0

Meulders, A. (2019). From fear of movement-related pain and avoidance to chronic pain disability: A state-of-the-art review. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 26, 130-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.12.007

Meus, T., van Eetvelde, J. S., Meuwissen, I., Meeus, M., Boullosa, D. A., Timmermans, A. A. A., & Verbrugghe, J. (2025). Exercise and heart rate variability in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review. Sports Medicine - Open, 11(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-025-00789-1

Mogil, J. S., Ritchie, J., Smith, S. B., Strasburg, K., Kaplan, L., Wallace, M. R., & Melancon, S. M. (2005). Melanocortin-1 receptor gene variants affect pain and mu-opioid analgesia in mice and humans. Journal of Medical Genetics, 42(7), 583-587. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.2004.027698

Nasir, A., Afridi, M., Afridi, O. K., Khan, M. A., Khan, A., Zhang, J., & Qian, B. (2025). The persistent pain enigma: Molecular drivers behind acute-to-chronic transition. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 159, 105598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105598

Nickel, J. C., Gonzalez, Y. M., Wu, Y., Choi, D. S., Liu, H., & Iwasaki, L. R. (2025). Nocturnal autonomic nervous system dynamics and chronic painful temporomandibular disorders. JDR Clinical and Translational Research, 10(2), 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1177/23800844241234567

Ortiz, S., Gomez, T., Andrade, T., Harnisch, A., Salazar, A., Valdespino, S., Snyder, E., Vallinayagam, M., Sanchez, P., & Wilkinson, K. (2022). Effect of sympathetic neurotransmitters on muscle spindle afferent sensitivity to muscle stretch in adult mice. The FASEB Journal, 36(S1), e22290. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.2022.36.S1.R2229

Parisien, M., Lima, L. V., Dagostino, C., El-Hachem, N., Drury, G. L., Grant, A. V., Bhouri, J., Bhouri, J., Bhouri, J., & Diatchenko, L. (2022). Acute inflammatory response via neutrophil activation protects against the development of chronic pain. Science Translational Medicine, 14(643), eabj9954. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abj9954

Partanen, J., Ojala, T., & Arokoski, J. (2010). Myofascial syndrome and pain: A neurophysiological approach. Pathophysiology, 17(1), 19-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathophys.2009.05.002

Partanen, J. V., Lajunen, H. R., & Liljander, S. (2023). Muscle spindles as pain receptors. BMJ Neurology Open, 5(1), e000420. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjno-2023-000420

Pinho-Ribeiro, F. A., Verri, W. A., Jr., & Chiu, I. M. (2016). Nociceptor sensory neuron-immune interactions in pain and inflammation. Trends in Immunology, 38(1), 5-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2016.10.001

Popkirov, S., Enax-Krumova, E. K., Mainka, T., Hoheisel, M., & Hausteiner-Wiehle, C. (2020). Functional pain disorders: More than nociplastic pain. NeuroRehabilitation, 47(3), 279-292. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-203007

Posada-Quintero, H. F., Kong, Y., Nguyen, K., Tran, C., Beardslee, L., Chen, L., Guo, T., Cong, X., & Chon, K. H. (2021). Sensitive physiological indices of pain based on differential characteristics of electrodermal activity. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 68(9), 3024-3032. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2021.3127802

Radovanovic, D., Peikert, K., Lindstrom, M., & Pedrosa Domellof, F. (2015). Sympathetic innervation of human muscle spindles. Journal of Anatomy, 226(6), 542-548. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.12327

Rogers, A. H., & Farris, S. G. (2022). A meta-analysis of the associations of elements of the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain with negative affect, depression, anxiety, pain-related disability and pain intensity. European Journal of Pain, 26(8), 1611-1635. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1994

Ropero Pelaez, F. J., & Taniguchi, S. (2016). The gate theory of pain revisited: Modeling different pain conditions with a parsimonious neurocomputational model. Neural Plasticity, 2016, 4131395. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/4131395

Sas, D., Gaudel, F., Verdier, D., & Kolta, A. (2023). Hyperexcitability of muscle spindle afferents in jaw-closing muscles in experimental myalgia: Evidence for large primary afferents involvement in chronic pain. Experimental Physiology, 108(12), 1630-1641. https://doi.org/10.1113/EP091940

Shah, J. P., Thaker, N., Heimur, J., Aredo, J. V., Sikdar, S., & Gerber, L. (2015). Myofascial trigger points then and now: A historical and scientific perspective. PM&R, 7(7), 746-761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.01.024

Sommer, C., Leinders, M., & Uceyler, N. (2017). Inflammation in the pathophysiology of neuropathic pain. Pain, 158(Suppl 1), S37-S45. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000781

Sullivan, M. J. L., Sturgeon, J. A., Lumley, M. A., & Ballantyne, J. (2022). Reconsidering Fordyce's classic article, "Pain and suffering: What is the unit?" to help make our model of chronic pain truly biopsychosocial. Pain, 163(11), 2145-2151. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002678

Tracy, L. M., Ioannou, L., Baker, K. S., Gibson, S. J., Georgiou-Karistianis, N., & Giummarra, M. J. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for decreased heart rate variability in chronic pain implicating parasympathetic nervous system dysregulation. PAIN, 157(1), 7-29. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000360

Treede, R. D. (2016). Gain control mechanisms in the nociceptive system. Pain, 157(6), 1199-1204. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000488

Vanderwall, A. G., & Milligan, E. D. (2019). Cytokines in pain: Harnessing endogenous anti-inflammatory signaling for improved pain management. Frontiers in Immunology, 10, 3009. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.03009

Varangot-Reille, C., Pezzulo, G., & Thacker, M. (2024). The fear-avoidance model as an embodied prediction of threat. Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Neuroscience, 24(3), 728-742. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-024-01135-3

Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Linton, S. J. (2000). Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: A state of the art. Pain, 85(3), 317-332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0

Wood, M. J., Miller, R. E., & Malfait, A. M. (2022). The genesis of pain in osteoarthritis: Inflammation as a mediator of osteoarthritis pain. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 38(2), 311-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2021.11.008

Woolf, C. J. (2022). Pain modulation in the spinal cord. Frontiers in Pain Research, 3, 1006614. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpain.2022.1006614

Yang, S., & Chang, M. C. (2019). Chronic pain: Structural and functional changes in brain structures and associated negative affective states. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(13), 3130. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20133130

Yeater, T., Cruz, C., Cruz-Almeida, Y., & Allen, K. D. (2022). Autonomic nervous system dysregulation and osteoarthritis pain: Mechanisms, measurement, and future outlook. Current Rheumatology Reports, 24(5), 147-157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-022-01069-4

Yoo, Y., & Kim, K. H. (2024). Current understanding of nociplastic pain. The Korean Journal of Pain, 37(1), 3-12. https://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2024.37.1.3

Zale, E. L., Lange, K. L., Fields, S. A., & Ditre, J. W. (2013). The relation between pain-related fear and disability: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Pain, 14(10), 1019-1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2013.05.005