CNS Applications

What You Will Learn

This chapter takes you into neurofeedback, one of the most exciting frontiers in biofeedback practice. You will discover how clinicians use the quantitative EEG (qEEG) to peer into brain function and design training protocols tailored to each individual. You will learn the three major training strategies: performance-based protocols, Z-score training, and connectivity training. The chapter examines neurofeedback applications for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), traumatic brain injury, substance use disorders, epilepsy, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and tinnitus.

For each condition, you will explore the underlying neuroscience, review landmark research studies, and understand current efficacy ratings. You will see how heart rate variability biofeedback complements EEG training for anxiety and mood disorders, and why combining modalities often produces superior outcomes.

Imagine being able to watch your own brain activity on a screen and learn to change it. That is exactly what neurofeedback (NF) makes possible. Neurofeedback is a specialized form of biofeedback that trains people to modify their brainwave patterns, offering hope for conditions ranging from ADHD to addiction. Clinicians who use the quantitative EEG (qEEG), a computerized analysis of brain electrical activity recorded from multiple scalp locations, can assess and train disorders as diverse as addiction, ADHD, coma, and grand mal epilepsy. While neurofeedback training for disorders like ADHD and alcoholism requires significant time commitment and initial expense, it promises long-term cost savings and can reduce or even eliminate patient dependence on medication.

The neurofeedback community has increasingly embraced heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB), a technique that trains people to breathe at specific rates to optimize heart rhythm patterns, as a complementary intervention to treat anxiety and mood disorders. This integration reflects a growing recognition that brain and body systems work together in complex ways. Training multiple physiological systems often produces better clinical outcomes than focusing on one modality alone, much like how a fitness program that combines cardio, strength, and flexibility training outperforms any single approach.

For a child diagnosed with ADHD, neurofeedback could mean the difference between relying on daily stimulant medication throughout their school years versus learning to self-regulate their own attention. Parents often ask whether there are alternatives to medication, and neurofeedback represents one of the most evidence-based non-pharmacological options available.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

Although BCIA addresses the anatomy and physiology of the EEG in its Neurofeedback Blueprint, we include this important topic to provide a comprehensive introduction to the field.

This unit covers the Quantitative EEG, Neurofeedback Training Strategies, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Mild Closed Head Injuries and Traumatic Brain Injury, Substance Use Disorder, Epilepsy, Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Depression, and Tinnitus.

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter Lecture

Evidence-Based Practice (4th ed.)

We have updated the efficacy ratings for clinical applications covered in AAPB's Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). This authoritative resource provides the most current research synthesis for each clinical application covered in this chapter.

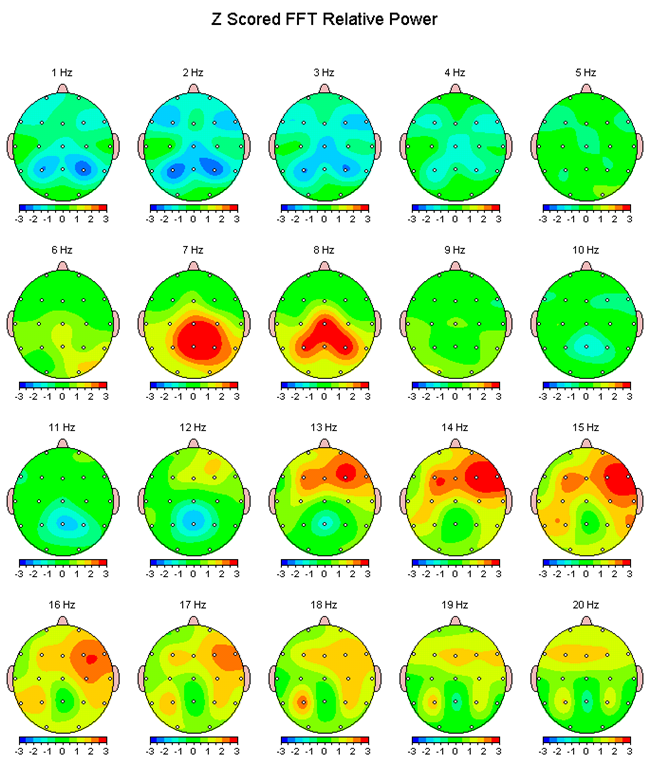

The Quantitative EEG (qEEG)

The quantitative EEG (qEEG) is like a real-time weather map for the brain. It measures and displays brain activity with considerably less delay than brain imaging techniques like fMRI, PET, or SPECT. While those technologies show where blood flows or glucose is consumed, the qEEG captures the brain's electrical conversation as it happens. QEEG measurements correlate strongly with neuropsychological tests, meaning the patterns clinicians see on the screen correspond to real differences in cognitive function. The qEEG provides valuable information about how power is distributed across different frequency bands (think of these as different "speeds" of brain activity) at all monitored sites, as well as information about connectivity between sites, which becomes particularly important when assessing traumatic brain injury (TBI).

While clinicians can provide effective neurofeedback training without qEEG assessment, using standardized protocols based on symptoms alone, Sterman and Egner (2006) argued that qEEG-guided protocols could double neurofeedback effectiveness when treating diverse symptoms. This makes intuitive sense: just as a mechanic can often fix a car by listening to it run, having detailed diagnostic information allows for more precise, targeted repairs.

Neurofeedback Training Strategies

Clinicians use three major neurofeedback strategies to help clients change their brain activity: performance-based, Z-score, and connectivity training. Each approach has its own logic and applications.

Performance-based protocols use specific tasks and neurofeedback training to correct symptoms and improve performance. The key feature of this approach is that it compares clients to themselves rather than to a normative database. If your attention improves, your reading speed increases, or your anxiety decreases, the training is working, regardless of whether your brain looks "normal" on a statistical comparison. This approach is particularly useful when the goal is functional improvement rather than achieving statistically typical brain patterns.

Z-score training takes a different approach by attempting to normalize brain function relative to a clinical database of healthy individuals. A Z-score tells you how many standard deviations a measurement falls from the average, so Z-score training identifies brain activity that is unusually high or low (typically 2 or more standard deviations from the mean) and trains it toward normal values. Think of it like a thermostat: if the brain is running too hot or too cold in certain regions, Z-score training nudges it back toward the comfortable middle range.

Connectivity training focuses on the communication between different brain regions. The brain is not just a collection of independent areas; it is a network where regions must coordinate their activity to function effectively. Connectivity training addresses situations where two brain sites are communicating too much (hypercoherence) or too little (hypocoherence), as measured by indices like coherence (how synchronized the activity is) and comodulation (how activity levels rise and fall together). This approach is particularly relevant for conditions like TBI, where injury often disrupts the connections between brain regions rather than damaging a single location.

Currently, there are insufficient data to compare the efficacy of these training strategies for specific disorders or optimal performance applications. Research is ongoing to determine which approach works best for which conditions.

The qEEG provides real-time brain activity measurement with valuable information about power distribution across frequency bands and connectivity between sites. Three major neurofeedback strategies include performance-based protocols (comparing clients to themselves), Z-score training (normalizing brain function to database means), and connectivity training (correcting communication between brain sites). QEEG-guided protocols may enhance neurofeedback effectiveness by allowing more targeted interventions.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is characterized by a consistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity that disrupts daily functioning or development (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). ADHD is not simply being easily distracted or having high energy; it represents a fundamental difference in how the brain regulates attention and behavior. Roughly 30% of children diagnosed with ADHD continue to meet diagnostic criteria as adults (Spencer, Biederman, & Mick, 2007), meaning this is not something most people simply "grow out of." Check out Dr. Russell Barkley's video ADHD is a Disorder of Impairment not Knowledge.

The Neurophysiological Basis of ADHD

Why do children with ADHD have trouble paying attention? The answer lies partly in their brainwave patterns. Children with ADHD often display an elevated theta/beta ratio (TBR), meaning they show too much slow-wave theta activity (4-8 Hz) and not enough fast-wave beta activity (13-21 Hz) over frontal and central brain regions (Wang, Wang, Wang, & Wong, 2024). To understand this, think of theta waves as the brain in a drowsy, daydreaming state, while beta waves represent the brain in an alert, focused mode. An elevated TBR suggests the brain is not revving up to full alertness when it should be.

This pattern may reflect cortical hypoarousal, a state where the cortex (the brain's outer layer responsible for higher functions) is not adequately activated. Imagine trying to concentrate while half-asleep: that is somewhat analogous to what children with ADHD experience. Their brains are not generating enough of the fast activity associated with sustained attention. The TBR may also reflect deficient cortical responses during mental effort or impaired top-down attention control, the ability to voluntarily direct attention where you want it, mediated by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Bluschke et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2024).

Why TBR Seemed Like a Big Deal

The EEG theta/beta ratio (TBR) took off in ADHD because early studies often found that, on average, people with ADHD showed relatively more slow "theta" activity and/or less faster "beta" activity at rest—making TBR look like a simple, objective biomarker. But when researchers pooled results across many studies, the picture got messy: effects varied a lot between samples and even appeared to drift over time, undermining the idea that a "high TBR" reliably signals ADHD in any one person (Arns et al., 2013).

The Core Problem: It's Not Specific Enough

TBR changes for plenty of reasons that aren't ADHD—like drowsiness, sleep loss, developmental stage, and medication effects—so a high value can't cleanly separate ADHD from non-ADHD. That overlap is why the American Academy of Neurology's practice advisory cautions that TBR should not be used to confirm ADHD (outside research) and warns about misdiagnosis risk if it's treated like a diagnostic test (Gloss et al., 2016).

ADHD Isn't One Brain Pattern

A key modern insight is that ADHD is heterogeneous: there may be a subgroup with elevated TBR, not the whole diagnosis. Large-sample work has reported evidence for a "high-TBR cluster" that represents only a minority of people with ADHD, which fits the broader view that multiple EEG profiles can exist under the ADHD umbrella (Bussalb et al., 2019; Bong & Kim, 2021).

So What's the Controversy, in One Line?

TBR can be an interesting research signal and sometimes an assessment aid, but overreliance turns a state-sensitive, non-specific ratio into a pseudo "brain test for ADHD"—a leap the evidence and guidelines don't support (Arns et al., 2013; Gloss et al., 2016).

Understanding the neurophysiology of ADHD helps explain why telling a child with ADHD to "just pay attention" is rarely effective. Their brain is not generating the neural activity patterns needed for sustained focus. Neurofeedback trains the brain to produce these patterns, addressing the root cause rather than just managing symptoms.

Neurofeedback Protocols for ADHD

The Lubar ADHD protocol emerged from Joel Lubar and his colleagues' pioneering research with ADHD children at the University of Tennessee. The basic protocol trains clients to inhibit (reduce) theta activity (4-8 Hz) while increasing beta activity (13-21 Hz) over approximately 40 sessions, with each session using 30-minute training periods. The logic is straightforward: if the problem is too much slow activity and not enough fast activity, train the brain to shift that balance.

For electrode placement, the active electrode is typically placed at CZ (the top-center of the head) for most patients, with reference to the left ear and a ground on the right ear. Clinicians may adjust placement based on individual needs: C3 (left-center) for those who need to increase frontal activation, and C4 (right-center) for those with right-hemisphere deficits.

Landmark Research Studies

Lubar and Shouse (1976) published the first controlled studies of neurofeedback for hyperkinesis (the earlier term for ADHD). Their elegant design trained children in two conditions: first to increase SMR (sensorimotor rhythm) while suppressing theta, and then the opposite, decreasing SMR while increasing theta. When children completed the SMR increase/theta decrease protocol, both hyperkinetic behavior and academic performance improved. Crucially, the reverse pattern appeared when they received the opposite training, demonstrating that the changes were genuinely due to the neurofeedback rather than placebo effects or simply spending time with clinicians.

Lubar and Lubar (1984) trained 6 ADHD children using the Lubar protocol for 6 months to 2 years. The remarkable finding was that 5 of the 6 patients maintained their treatment gains at 8-year follow-up, far longer than medication effects typically persist once stopped. WISC-R intelligence scores increased about 12 points, and the increase in TOVA (Test of Variables of Attention) scores correlated with decreased slow EEG activity, confirming that the behavioral improvements tracked brain changes.

Lubar (1995) followed 52 patients treated with neurofeedback for as long as 10 years. Their improvement on the Conners scale, a standard measure of attention and ADHD symptoms, remained stable at follow-up. This durability distinguishes neurofeedback from medication, which typically stops working as soon as it is discontinued.

Rossiter and La Vaque (1995) conducted a head-to-head comparison, matching and randomly assigning 46 subjects to either Ritalin (the most common ADHD medication) or neurofeedback. Both groups improved equally on TOVA measures of inattention, impulsivity, information processing, and response variability. This finding challenged the assumption that medication was the only effective treatment for ADHD.

Thompson and Thompson (1998) reported treating 98 children and 13 adults over 40 fifty-minute sessions using Lubar's ADHD protocol. The percentage of children using Ritalin declined from 30% at the start of the study to just 6% post-treatment, suggesting many children no longer needed medication after completing neurofeedback. Theta/beta ratios significantly declined for children but not for adults, and participants achieved impressive gains on intelligence tests, the TOVA, and the Wide Range Achievement Test.

Monastra, Monastra, and George (2002) compared 49 children in a 1-year multimodal program (Ritalin, parent counseling, and academic consultation) with 51 children who received the same program plus neurofeedback (weekly 30 to 40-minute sessions using the Lubar protocol with a cash reward for increased frontal cortical arousal).

Here is the critical finding: both groups significantly improved on the TOVA and the Attention Deficit Disorders Evaluation Scale when medicated with Ritalin, but only the group that received neurofeedback maintained performance gains when unmedicated. A qEEG scan confirmed that reduced cortical slowing occurred only in children who received neurofeedback. In other words, medication improved performance temporarily, but neurofeedback produced lasting brain changes. Parenting style moderated behavioral symptoms at home but not in the classroom, highlighting the importance of parent involvement.

Gevensleben and colleagues (2009) conducted a multisite randomized controlled study of 102 children diagnosed with ADHD. The neurofeedback group received training that combined blocks of theta/beta training and slow cortical potential neurofeedback, while the control group received computer-based attention skills training. The combined neurofeedback group outperformed the control group on parent and teacher ratings, and both neurofeedback protocols produced comparable changes. Importantly, these gains were maintained at a 6-month follow-up (Gevensleben et al., 2010), suggesting the training produced lasting improvements.

As of 2026, the American Academy of Pediatrics continues to rate neurofeedback for child and adolescent attention and hyperactivity behaviors as Level 1, Best Support, placing it among the most evidence-based treatments available.

Clinical Efficacy

Based on six randomized controlled trials, Stefanie Enriquez-Geppert and colleagues rated neurofeedback for ADHD level 5, efficacious and specific in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). This is the highest possible rating, indicating strong evidence of effectiveness with well-controlled studies demonstrating superiority over credible placebo treatments.

Research comparing different protocol variations found that beta upregulation, whether alone or combined with theta training, produced the most consistent improvements in response inhibition and conflict control (Enriquez-Geppert, Smit, Pimenta, & Arns, 2019). This suggests that enhancing fast brain activity may be particularly important for improving the cognitive control deficits central to ADHD.

Neurofeedback for ADHD is rated level 5 (efficacious and specific), the highest evidence rating. The Lubar protocol trains clients to inhibit theta and increase beta over approximately 40 sessions. Children with ADHD often show elevated theta/beta ratios, reflecting cortical hypoarousal (an underactivated brain state) and impaired attention. Through operant conditioning, theta/beta training aims to normalize this imbalance. Research consistently shows improvements comparable to stimulant medication, with the crucial advantage that neurofeedback gains persist even when medication is discontinued.

Comprehension Questions: ADHD

- What are the three main symptoms that characterize ADHD, and how does neurofeedback address each?

- Describe the Lubar ADHD protocol, including electrode placement, frequency targets, and typical session parameters.

- How did the Monastra, Monastra, and George (2002) study demonstrate the lasting effects of neurofeedback compared to medication alone?

- What efficacy rating did neurofeedback for ADHD receive in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.)?

Mild Closed Head Injuries and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) results when an external force produces intracranial injury through acceleration (the brain sloshing inside the skull) or direct impact. Unlike a stroke, which damages a specific blood vessel territory, TBI can disrupt brain function through both structural damage and altered neural connectivity across widespread regions. Check out Siddharthan Chandran's TED Talk Can the Damaged Brain Repair Itself?

Neurophysiological Changes Following TBI

TBI produces characteristic EEG abnormalities, including increased theta activity (slow waves) and decreased beta activity (fast waves), reflecting disrupted neural communication between brain areas (Chen et al., 2023). Axonal injury, damage to the long fibers connecting neurons, interferes with connectivity between brain regions. This leads to deficits in learning, memory, attention, and information processing speed, not because any single area is destroyed, but because the regions can no longer coordinate their activity effectively.

These dysregulated EEG patterns, abnormal brainwave signatures that deviate from healthy functioning, correlate strongly with neurocognitive impairments and provide targets for neurofeedback intervention.

Demographics

TBI is far more common than most people realize. The 2023 National Health Interview Survey found that approximately 3% of Americans, representing nearly 10 million people, reported a TBI in the past year (Waltzman, Black, Daugherty, Peterson, & Zablotsky, 2025). In 2021, there were approximately 69,473 TBI-related deaths and 214,110 TBI-related hospitalizations in the United States, averaging about 190 deaths and 586 hospitalizations per day (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2023).

Neurofeedback Studies

Ayers (1995) reported treating 32 level-two coma patients, individuals who had been comatose for more than 2 months, noninvasively with neurofeedback. The results were remarkable: 25 of 32 patients emerged from their comas after just 1-6 treatments. The protocol involved inhibiting 4-7 Hz activity (slow waves) while reinforcing the replacement of that slow activity with 15-18 Hz activity (faster waves).

Walker, Norman, and Weber (2002) reported that 88% of mild TBI patients achieved over 50% improvement in EEG coherence, a measure of how well different brain regions communicate. All patients who had been previously employed returned to work after completing their training, a particularly meaningful outcome given that TBI often ends careers.

Clinical Efficacy

Anne Ward Stevens and Kori Trotter rated neurofeedback for concussion as level 3, probably efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

Neurofeedback for TBI works through neuroplasticity, the brain's remarkable capacity to reorganize neural pathways and form new connections. Just as physical therapy helps the body compensate for injury by strengthening alternative pathways, neurofeedback helps the brain develop new patterns of activity. Training typically involves inhibiting slow-wave activity (4-7 Hz) and rewarding faster frequencies (15-18 Hz) at sites showing abnormality on qEEG assessment.

Neurofeedback for concussion is rated level 3 (probably efficacious). TBI affects nearly 10 million Americans annually, with symptoms including memory deficits, attention problems, and impaired decision-making. Neurofeedback protocols typically involve inhibiting theta (4-7 Hz) and rewarding beta (15-18 Hz) activity. Research shows improvements in attention, memory, cognitive function, and return-to-work rates, working through the brain's neuroplastic capacity to form new connections.

Comprehension Questions: Traumatic Brain Injury

- What are the primary causes of traumatic brain injury in the United States?

- What neurofeedback protocol did Ayers use to treat level-two coma patients, and what were the outcomes?

- How does Z-score training and LORETA improve the customization of neurofeedback treatment for TBI?

Substance Use Disorder

Imagine trying to help someone who has lost jobs, relationships, and housing to addiction, who may feel that external forces control their life, and who has failed at recovery multiple times. Substance use disorder (SUD) presents some of the most challenging cases in clinical practice. Biofeedback can serve as a self-regulation strategy to help manage alcohol cravings and negative thinking patterns.

Neurophysiological Basis

Individuals with substance use disorders display altered EEG patterns, particularly within the alpha, theta, and beta bands. The characteristic pattern is low alpha (the relaxed, wakeful rhythm) combined with high beta (fast activity associated with anxiety and rumination). This pattern has been interpreted as central nervous system hyperarousal, a chronically overactivated brain state associated with anxiety, higher relapse risk, and poor treatment outcomes (Sokhadze, Trudeau, & Cannon, 2008). Think of it as a brain that cannot calm down, constantly on edge and seeking relief, which substances temporarily provide.

Alpha-theta neurofeedback induces a hypnagogic state, the twilight zone between waking and sleeping where consciousness becomes fluid and dreamlike. This state may facilitate access to unconscious material and support psychological transformation. Recent research confirms that alpha-theta protocols reduce craving, anxiety, and relapse rates among individuals with alcohol and substance dependence (Yazdani & Khosravani, 2025).

The Menninger and Peniston Protocols

The Menninger ON-OFF-ON EEG protocol teaches patients to increase the amplitude (power) within a frequency band, reduce it, and then increase it again during 100- or 200-second segments. This approach may produce superior control compared to procedures that only train amplitude increases, because it demonstrates that the patient can move brain activity in both directions rather than just hoping it happens to change in the desired direction.

Importantly, temperature biofeedback and frontal SEMG (surface electromyography) biofeedback precede alpha-theta training. These preliminary sessions serve a crucial purpose: they teach patients the strategy of passive volition, sometimes called "allowing" rather than "trying." Active effort and straining actually interfere with alpha-theta training; patients must learn to let changes happen rather than force them. This counterintuitive skill must be established before the deeper alpha-theta work can succeed.

The Peniston addiction protocol (1989) is a comprehensive multimodal approach that incorporates both biofeedback and non-biofeedback components. Patients start with visualization training, receive 6 temperature biofeedback sessions, learn rhythmic breathing techniques, participate in autogenic training exercises, and experience guided imagery. This extensive preparation readies patients for 30 alpha-theta sessions.

The Kaiser-Scott protocol starts with neurofeedback ADHD training (theta/beta training) and then progresses to the Peniston protocol. The rationale is that many substance abusers have underlying ADHD or attention problems that interfere with their ability to benefit from alpha-theta training.

Scott, Kaiser, Othmer, and Sideroff (2005) randomly assigned patients with mixed substance abuse to EEG biofeedback or a control group. Seventy-seven percent of patients who completed EEG training remained abstinent at 12 months compared with 44% of controls, nearly doubling the success rate.

Clinical Efficacy

Estate M. Sokhadze and David Trudeau rated NFB for SUD as probably efficacious based on an RCT (N = 121) using the Scott–Kaiser NFB protocol.

The five other RCTs incorporated alpha and high beta regulation, alpha/theta with TEMP and guided imagery, SMR and beta upregulation with 1–13 Hz and high beta (18–22 Hz) suppression, SMR/theta followed by alpha-theta, and the Scott–Kaiser NFB protocol.

The Scott–Kaiser protocol, which starts with NF ADHD training and then progresses to the Peniston protocol, has improved retention and abstinence in these hard-to-treat populations. Participants increased abstinence, quality of life, self-efficacy, time in the program, and TOVA (continuous attention), and reduced addiction severity and craving.

The Scott–Kaiser modification of the Peniston Protocol can be classified as probably efficacious with residential or office-based rehabilitation and opioid replacement for alcohol, opioid, mixed-substance, and stimulant abusers.

Alpha-theta NF received a level-2 rating of possibly efficacious.

The Scott-Kaiser modification of the Peniston Protocol is rated probably efficacious for substance use disorders. This comprehensive multimodal approach combines ADHD neurofeedback training with the Peniston protocol, which includes visualization, temperature biofeedback, autogenic training, and 30 alpha-theta sessions that induce a hypnagogic state facilitating psychological processing. The protocol improves treatment retention, abstinence rates, and quality of life while reducing craving.

Comprehension Questions: Substance Use Disorder

- What is the purpose of temperature and SEMG biofeedback in the Menninger/Peniston protocols?

- Describe the concept of "passive volition" and explain why it is critical to alpha-theta training success.

- How does the Scott-Kaiser protocol modify the original Peniston protocol?

- What outcomes did the Scott, Kaiser, Othmer, and Sideroff (2005) study report for 12-month abstinence rates?

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a neurological condition marked by recurrent, unprovoked seizures resulting from abnormal electrical activity in the brain. The two main types are petit mal seizures (absence seizures) and tonic-clonic seizures (grand mal seizures). Petit mal seizures feature brief loss of consciousness without abnormal movement; the patient appears to be daydreaming. Tonic-clonic seizures are primary generalized seizures with convulsions, featuring a cry, loss of consciousness, falling, and rhythmic jerking of all extremities.

Demographics

Active epilepsy affects approximately 1.1% of the U.S. population, or about 3.9 million adults and children (Kobau, Luncheon, & Greenlund, 2023). The World Health Organization (2024) reports that 50 million people worldwide have epilepsy, making it one of the most common neurological diseases globally. About 1.5 million community-dwelling Americans with active epilepsy report uncontrolled seizures despite treatment (Kobau, Luncheon, & Greenlund, 2024), highlighting the need for additional therapeutic approaches.

Neurophysiological Basis

The sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) is an EEG rhythm from 12-14 Hz located over the sensorimotor cortex. SMR is associated with inhibition of movement and reduced muscle tone. When Barry Sterman was researching sleep in cats in the 1960s, he discovered that cats trained to increase SMR were remarkably resistant to seizure-inducing compounds. This serendipitous finding led to the development of SMR up-training for epilepsy in humans.

Sterman's protocol trains epileptic patients to increase SMR (12-14 Hz) amplitude and duration while suppressing theta (slow-wave activity), high beta (fast activity associated with tension), epileptiform spikes, and EMG artifact during 36 sessions. The training essentially strengthens the brain's natural inhibitory mechanisms.

Sterman (2000) summarized 18 peer-reviewed studies in which 174 patients were trained using his SMR protocol. The outcome data were impressive: 82% of patients clinically improved, reducing seizures by more than 30%. The average seizure reduction exceeded 50%.

Clinical Efficacy

Lauren Frey rated SMR-based and SCP-based neurofeedback as efficacious for seizures. SMR neurofeedback improves seizure control by enhancing functional connectivity across the brain (Frey, 2023).

For the 1.5 million Americans whose seizures are not controlled by medication, neurofeedback offers a genuine alternative. The training teaches the brain to produce its own internal stabilization, potentially reducing both seizure frequency and the side effects that often accompany anti-seizure medications.

SMR-based and SCP-based neurofeedback are rated efficacious for seizures. SMR (12-14 Hz) reflects thalamocortical inhibitory circuits, essentially the brain's braking system. When patients learn to increase SMR through operant conditioning, they raise excitation thresholds and reduce seizure susceptibility. Research shows 82% of patients achieving clinical improvement and 79% experiencing significant seizure reduction.

Comprehension Questions: Epilepsy

- What distinguishes petit mal seizures from tonic-clonic seizures?

- Describe Sterman's SMR protocol for epilepsy, including what is trained and what is inhibited.

- What percentage of patients showed clinical improvement in Sterman's summary of 18 peer-reviewed SMR studies?

Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is defined by excessive anxiety and worry occurring more days than not for at least 6 months. Unlike normal worry that comes and goes with life circumstances, GAD involves persistent, hard-to-control worry about multiple areas of life.

DSM-5 classifies Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as one of the Trauma and Stress-Related Disorders. PTSD develops in some people following exposure to a traumatic event like assault, military combat, rape, or witnessing death or serious injury.

Neurophysiological Basis

Anxiety disorders are associated with autonomic nervous system dysregulation, characterized by reduced heart rate variability (HRV) and parasympathetic withdrawal. In plain terms, the nervous system is stuck in "fight-or-flight" mode, with the calming branch (parasympathetic) unable to adequately counterbalance the arousal branch (sympathetic).

Heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB) targets this dysregulation by training patients to breathe at their resonance frequency, typically around 6 breaths per minute, which maximizes the amplitude of respiratory sinus arrhythmia and strengthens baroreflex function (Lehrer et al., 2020). Meta-analyses confirm that HRVB produces large effect sizes for reducing self-reported stress and anxiety (Goessl, Curtiss, & Hofmann, 2017).

Demographics

Anxiety disorders are the most common mental disorders in the United States. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, approximately 19.1% of U.S. adults, nearly one in five, experience an anxiety disorder in any given year (NIMH, 2023). Post-traumatic stress disorder affects approximately 6% of Americans at some point in their lives (Goldstein, Smith, & Chou, 2016).

Clinical Efficacy

Fred Shaffer, Christopher Zerr, and Zachary Meehan rated biofeedback for anxiety as level 4, efficacious. The biofeedback modalities demonstrating effectiveness include HRV increase, thermal/temperature increase, SEMG relaxation, EDA decrease, alpha-theta neurofeedback, and alpha up-training neurofeedback.

Biofeedback for anxiety is rated level 4 (efficacious). HRV biofeedback trains patients to breathe at their resonance frequency (typically around 6 breaths per minute), maximizing respiratory sinus arrhythmia and strengthening vagal tone. Multiple modalities show benefit: HRV biofeedback addresses autonomic dysregulation, temperature biofeedback promotes peripheral relaxation, SEMG biofeedback releases muscle tension, and alpha-theta neurofeedback reduces central nervous system hyperarousal.

Depression

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is more than just feeling sad. It is defined by persistent sadness, loss of interest or pleasure in activities that used to be enjoyable, and feelings of guilt or low self-worth, along with disturbed appetite and sleep, difficulty concentrating, and in severe cases, suicidal ideation.

Neurophysiological Basis

Richard Davidson proposed the theory of frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA) as a neurophysiological marker for depression (Davidson, 1992). The behavioral activation system (BAS), mediated primarily by the left frontal cortex, drives approach behavior and positive emotions. The behavioral inhibition system (BIS), mediated by the right frontal cortex, drives withdrawal motivation and negative affect.

Depression is associated with reduced left frontal activity relative to right frontal activity, reflecting diminished approach motivation and positive affect. The depressed brain shows the signature of withdrawal. Here is a crucial point that initially seems counterintuitive: because alpha power is inversely related to cortical activity (more alpha means less activity), higher right alpha (indicating lower right activity) actually represents a healthier pattern.

Demographics

According to the most recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2021-2023), depression prevalence in the past two weeks was 13.1% among adolescents and adults aged 12 and older (Brody & Hughes, 2025). Depression prevalence is highest among adolescents aged 12-19, with 26.5% of adolescent females reporting symptoms. Nearly 21% of Americans will experience major depressive disorder at some point in their lifetime.

Clinical Efficacy

Based on 10 RCTs, Zachary Meehan, Fred Shaffer, and Christopher Zerr rated biofeedback and neurofeedback for MDD as efficacious and specific in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

Both alpha asymmetry neurofeedback and HRV biofeedback have demonstrated efficacy for depression. Meta-analysis found a medium effect size (g = 0.38) for HRV biofeedback in reducing depressive symptoms, comparable to other established treatments like cognitive-behavioral therapy (Pizzoli et al., 2021).

Biofeedback and neurofeedback for major depressive disorder are rated efficacious and specific. Alpha asymmetry neurofeedback targets the imbalance between left frontal activity (approach/positive affect) and right frontal activity (withdrawal/negative affect). Training increases right frontal alpha (reduces right activity) to normalize the asymmetry. HRV biofeedback complements neurofeedback by addressing autonomic dysregulation.

Tinnitus

Tinnitus involves the perception of sound, often described as ringing, buzzing, or hissing, when no external acoustic stimulus is present. Tinnitus is commonly associated with hearing loss and affects approximately 10-15% of U.S. adults (Batts & Stankovic, 2024). Tinnitus is the top compensated disability among U.S. veterans.

Clinical Efficacy

Shaffer and Mannion (2016) rated biofeedback for tinnitus as probably efficacious and neurofeedback for tinnitus as possibly efficacious.

Cutting-Edge Topics in CNS Applications

Neurofeedback and Brain-Computer Interfaces

Advances in brain-computer interface (BCI) technology are transforming what is possible with neurofeedback. Modern BCI systems can detect and respond to brain signals with unprecedented precision, opening new avenues for treating conditions from ADHD to severe depression.

Real-Time fMRI Neurofeedback for Psychiatric Disorders

Real-time functional MRI (rtfMRI) neurofeedback allows patients to observe and regulate activity in specific brain regions with high spatial precision. While EEG-based neurofeedback can localize activity only roughly, fMRI can target structures deep in the brain with millimeter accuracy.

Personalized Neurofeedback Protocols

The field is moving toward individualized treatment approaches based on each patient's unique brain patterns. Machine learning algorithms can now analyze qEEG data to identify subtypes within diagnostic categories like ADHD, allowing clinicians to select protocols most likely to benefit specific patients.

Test Yourself

Click on the ClassMarker logo to take 10-question tests over this unit without an exam password.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Visit the BioSource Software Website

BioSource Software offers Human Physiology, which satisfies BCIA's Human Anatomy and Physiology requirement, and Biofeedback100, which provides extensive multiple-choice testing over BCIA's Biofeedback Blueprint.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this module, consider the elements that neurofeedback training shares with modalities like EMG and temperature biofeedback. How is neurofeedback training different? What unique challenges does training brain activity present compared to training peripheral physiological signals?

Glossary

A1 score: frontal alpha asymmetry score calculated by subtracting log left-alpha power from log right-alpha power to assess hemispheric activation balance.

active epilepsy: self-reported doctor-diagnosed epilepsy with current treatment using antiseizure medicines or at least one seizure in the past 12 months.

alpha asymmetry neurofeedback for mood disorders: a protocol that trains depressed clients to increase right frontal alpha relative to left frontal alpha, thereby reducing right frontal activity or increasing left frontal activity.

behavioral activation system (BAS): brain system associated with approach motivation and positive emotions, mediated primarily by left frontal cortex.

behavioral inhibition system (BIS): brain system associated with withdrawal motivation and negative affect, mediated primarily by right frontal cortex.

central nervous system hyperarousal: a chronically overactivated brain state characterized by low alpha and high beta activity, associated with anxiety and poor treatment outcomes in substance use disorders.

connectivity training: neurofeedback designed to correct deficient or excessive communication between two brain sites as measured by indices like coherence and comodulation.

cortical hypoarousal: an underactivated cortical state associated with reduced alertness and impaired attention, often seen in ADHD.

dysregulated EEG patterns: abnormal brainwave signatures that deviate from healthy functioning and correlate with neurocognitive impairments.

frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA): the difference in alpha power between left and right frontal regions, proposed as a neurophysiological marker for depression.

generalized anxiety disorder (GAD): excessive anxiety and worry occurring more days than not for at least 6 months.

heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB): a technique that trains people to breathe at specific rates to optimize heart rhythm patterns and improve autonomic function.

hypnagogic state: the twilight zone between waking and sleeping where consciousness becomes fluid and dreamlike, induced by alpha-theta neurofeedback.

Kaiser-Scott protocol: a modification of the Peniston protocol that starts with ADHD neurofeedback training before progressing to alpha-theta training; developed for stimulant and cannabis dependence.

Lubar ADHD protocol: trains clients to inhibit theta (4-8 Hz) and increase beta (13-21 Hz) over approximately 40 sessions using 30-minute training periods.

major depressive disorder (MDD): a mood disorder defined by persistent sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, feelings of guilt or low self-worth, disturbed appetite and sleep, difficulty concentrating, and suicidal ideation.

Menninger ON-OFF-ON EEG protocol: teaches patients to increase, decrease, and then increase amplitude within a frequency band during 100- or 200-second segments.

neurofeedback (NF): a specialized form of biofeedback that trains people to modify their brainwave patterns through operant conditioning.

neuroplasticity: the brain's capacity to reorganize neural pathways and form new connections in response to experience or injury.

passive volition: a strategy of allowing changes to happen rather than actively forcing them, critical to alpha-theta training success.

Peniston addiction protocol: a multimodal treatment including visualization training, temperature biofeedback, rhythmic breathing, autogenic training, and 30 alpha-theta sessions.

performance-based protocols: neurofeedback that uses tasks and training to correct symptoms and improve performance, comparing clients to themselves rather than normative databases.

petit mal seizures: absence seizures featuring loss of consciousness without abnormal movement; patient appears to be daydreaming.

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a trauma and stress-related disorder following exposure to traumatic events like assault, combat, or rape.

quantitative EEG (qEEG): computerized analysis of brain electrical activity recorded from multiple scalp locations, providing real-time information about power distribution and connectivity.

resonance frequency: the breathing rate, typically around 6 breaths per minute, that maximizes respiratory sinus arrhythmia and strengthens baroreflex function.

sensorimotor rhythm (SMR): an EEG rhythm from 12-14 Hz located over the sensorimotor cortex, associated with inhibition of movement and reduced muscle tone.

SMR up-training: neurofeedback protocol that trains patients to increase sensorimotor rhythm (12-14 Hz) amplitude while inhibiting slow-wave activity; used primarily for epilepsy treatment.

Sterman's protocol: trains epileptic patients to increase SMR (12-14 Hz) amplitude and duration while suppressing theta, high beta, epileptiform spikes, and EMG artifact during 36 sessions.

substance use disorder: a pattern of symptoms from substance use despite experiencing significant problems in multiple life areas.

theta/beta ratio (TBR): the ratio of theta to beta power in the brain's electrical activity, proposed as a biomarker for ADHD reflecting cortical hypoarousal.

theta/beta training: a neurofeedback procedure that down-trains theta and up-trains beta to address the elevated theta/beta ratio seen in ADHD.

tinnitus: the perception of sound, often described as ringing or buzzing, when no external acoustic stimulus is present.

tonic-clonic seizures: primary generalized seizures with convulsions, featuring a cry, loss of consciousness, falling, and rhythmic jerking of all extremities.

traumatic brain injury (TBI): intracranial injury due to acceleration or direct impact that disrupts normal brain function through both structural damage and altered neural connectivity.

Z-score training: a neurofeedback strategy that attempts to normalize brain function with respect to database mean values, targeting activity that is 2 or more standard deviations from the norm.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2012). Evidence-based child and adolescent psychosocial interventions.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author.

Arns, M., Conners, C. K., & Kraemer, H. C. (2013). A decade of EEG theta/beta ratio research in ADHD: A meta-analysis. Journal of Attention Disorders, 17(5), 374–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054712460087

Ayers, M. E. (1995). EEG neurofeedback to bring individuals out of level 2 coma. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 20(3), 304-305.

Baehr, E., Rosenfeld, J. P., & Baehr, R. (1997). The clinical use of an alpha asymmetry protocol in the neurofeedback treatment of depression. Journal of Neurotherapy, 2(3), 10-23.

Batts, S., & Stankovic, K. M. (2024). Tinnitus prevalence, associated characteristics, and related healthcare use in the United States. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas, 29, 100659.

Bluschke, A., Broschwitz, F., Kohl, S., Roessner, V., & Beste, C. (2016). The neuronal mechanisms underlying improvement of impulsivity in ADHD by theta/beta neurofeedback. Scientific Reports, 6, 31178.

Brody, D. J., & Hughes, J. P. (2025). Depression prevalence in adolescents and adults: United States, August 2021-August 2023. NCHS Data Brief, 527, 1-11.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). TBI data. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/traumatic-brain-injury/data-research/index.html

Chen, P.-Y., Su, I.-C., Shih, C.-Y., Liu, Y.-C., Su, Y.-K., Wei, L., Luh, H.-T., Huang, H.-C., Tsai, P.-S., Fan, Y.-C., & Chiu, H.-Y. (2023). Effects of neurofeedback on cognitive function, productive activity, and quality of life in patients with traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 37(5), 277-287.

Davidson, R. J. (1992). Anterior cerebral asymmetry and the nature of emotion. Brain and Cognition, 20(1), 125-151.

Enriquez-Geppert, S., Smit, D., Pimenta, M. G., & Arns, M. (2019). Neurofeedback as a treatment intervention in ADHD: Current evidence and practice. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(6), 46.

Frey, L. (2023). Epilepsy. In I. Khazan et al. (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). AAPB.

Gevensleben, H., et al. (2009). Is neurofeedback an efficacious treatment for ADHD? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(7), 780-789.

Gloss, D., Varma, J. K., Pringsheim, T., & Nuwer, M. R. (2016). Practice advisory: The utility of EEG theta/beta power ratio in ADHD diagnosis: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 87(22), 2375–2379. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003265

Goessl, V. C., Curtiss, J. E., & Hofmann, S. G. (2017). The effect of heart rate variability biofeedback training on stress and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 47(15), 2578-2586.

Goldstein, R. B., Smith, S. M., & Chou, S. P. (2016). The epidemiology of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(8), 1137-1148.

Kobau, R., Luncheon, C., & Greenlund, K. (2023). Active epilepsy prevalence among U.S. adults. Epilepsy & Behavior, 142, 109180.

Kobau, R., Luncheon, C., & Greenlund, K. J. (2024). About 1.5 million community-dwelling US adults with active epilepsy reported uncontrolled seizures. Epilepsy & Behavior, 157, 109852.

Lehrer, P., et al. (2020). Heart rate variability biofeedback improves emotional and physical health and performance: A systematic review and meta analysis. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 45(3), 109-129.

Lubar, J. F. (1995). Neurofeedback for the management of ADHD. In M. S. Schwartz (Ed.), Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Lubar, J. F., & Shouse, M. N. (1976). EEG and behavioral changes in a hyperkinetic child. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 1(3), 293-306.

Monastra, V. J., Monastra, D. M., & George, S. (2002). The effects of stimulant therapy, EEG biofeedback, and parenting style on ADHD symptoms. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 27(4), 231-249.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2023). Any anxiety disorder. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/any-anxiety-disorder

Peniston, E. G., & Kulkosky, P. J. (1989). Alpha-theta brainwave training and beta-endorphin levels in alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 13(2), 271-279.

Pizzoli, S. F. M., Marzorati, C., Gatti, D., Monzani, D., Mazzocco, K., & Pravettoni, G. (2021). A meta-analysis on heart rate variability biofeedback and depressive symptoms. Scientific Reports, 11, 6650.

SAMHSA. (2023). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Scott, W. C., Kaiser, D., Othmer, S., & Sideroff, S. I. (2005). Effects of an EEG biofeedback protocol on a mixed substance abusing population. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 31(3), 455-469.

Sokhadze, T. M., Cannon, R. L., & Trudeau, D. L. (2008). EEG biofeedback as a treatment for substance use disorders. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 33(1), 1-28.

Spencer, T. J., Biederman, J., & Mick, E. (2007). ADHD: Diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 7, 73-81.

Sterman, M. B. (2000). Basic concepts and clinical findings in the treatment of seizure disorders with EEG operant conditioning. Clinical Electroencephalography, 31(1), 45-55.

Sterman, M. B., & Egner, T. (2006). Foundation and practice of neurofeedback for the treatment of epilepsy. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 31(1), 21-35.

Thompson, L., & Thompson, M. (1998). Neurofeedback combined with training in metacognitive strategies. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 23(4), 243-263.

Walker, J. E., Norman, C. A., & Weber, R. K. (2002). Impact of qEEG-guided coherence training for patients with a mild closed head injury. Journal of Neurotherapy, 6(2), 37-45.

Waltzman, D., Black, L. I., Daugherty, J., Peterson, A. B., & Zablotsky, B. (2025). Prevalence of traumatic brain injury among adults and children. Annals of Epidemiology, 103, 40-47.

Wang, T.-S., Wang, S.-S., Wang, C.-L., & Wong, S.-B. (2024). Theta/beta ratio in EEG correlated with attentional capacity assessed by Conners Continuous Performance Test in children with ADHD. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1305397.

World Health Organization. (2024). Epilepsy fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy

Yazdani, S., & Khosravani, H. (2025). Neurofeedback in substance and non-substance-related addictions: A mini review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1716390.

Return to Top