Respiratory System Anatomy

What You Will Learn in This Unit

Breathing is one of those things we do about 20,000 times a day without giving it a second thought. Yet how your clients breathe can reveal volumes about their emotional state, stress levels, and overall health. In this unit, you will discover how the respiratory system maintains the delicate acid-base balance that keeps every cell in the body functioning optimally. You will learn why carbon dioxide, often dismissed as mere "waste gas," is actually the master regulator of oxygen delivery to tissues. You will explore the neural control centers that orchestrate each breath and understand why you cannot hold your breath indefinitely, no matter how hard you try. Perhaps most importantly for your clinical practice, you will learn to recognize six dysfunctional breathing patterns, including thoracic breathing, clavicular breathing, reverse breathing, overbreathing, hyperventilation, and apnea, and understand how these patterns can contribute to a surprising array of symptoms. By the end of this unit, you will see breathing assessment as an essential diagnostic tool and understand how breathing biofeedback can help restore healthy respiratory mechanics.

Healthcare providers who do not routinely observe their patients' breathing may miss helpful diagnostic information. Breathing assessment can provide useful information regarding a client's emotional state and respiratory mechanics. Frequent sighs could signal depression. Low exhaled CO2 could indicate overbreathing, which can cause diverse symptoms.

We encourage you to review breathing misconceptions in our A Comprehensive Breathing Myths Guide.

While medical disorders fall outside most practitioners' scope of practice, they can share breathing assessment findings relevant to medical disorders with their client's physician. For example, a physician managing a client's hypertension might appreciate information about their apnea since it can contribute to this problem.

Overbreathing may be the most common dysfunctional breathing pattern that can subtly reduce CO2 and produce diverse medical and psychological symptoms due to its disruption of homeostasis (Khazan, 2021).

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses Descriptions of most commonly employed biofeedback modalities: Respiration (III-A 2) and Structure and function of the autonomic nervous system (V-A 3).

This unit covers Respiratory Physiology and Disordered Breathing.

Please click on the link below to hear a full-length chapter lecture.

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter Lecture

Respiratory Physiology

Listen to a mini-lecture on Respiratory PhysiologyUnderstanding pH: The Foundation of Blood Chemistry

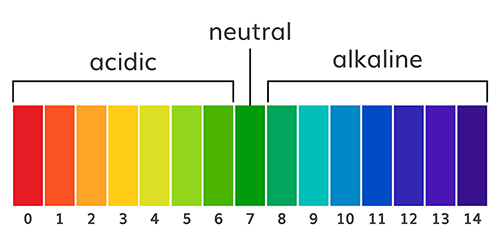

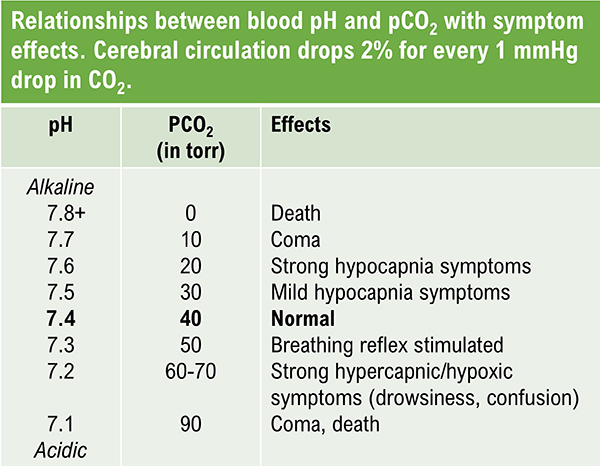

The abbreviation pH refers to the power of hydrogen, which is the concentration of hydrogen ions. Acidic solutions have a low pH (less than 7) due to a high concentration of hydrogen ions. A neutral solution of distilled water has a pH of 7. Alkaline or basic solutions have a high pH (greater than 7) due to a low concentration of hydrogen ions. The pH level regulates oxygen and nitric oxide release.

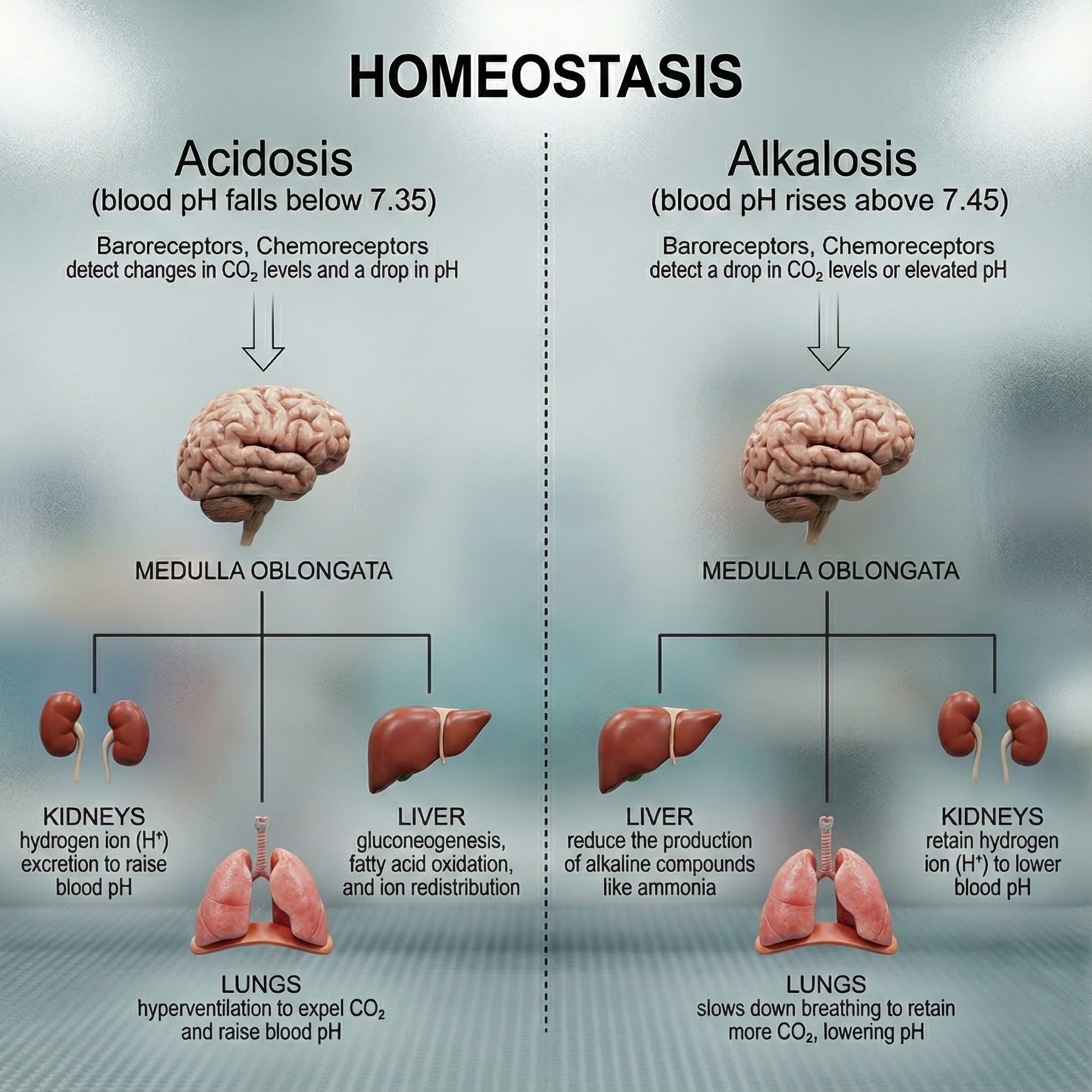

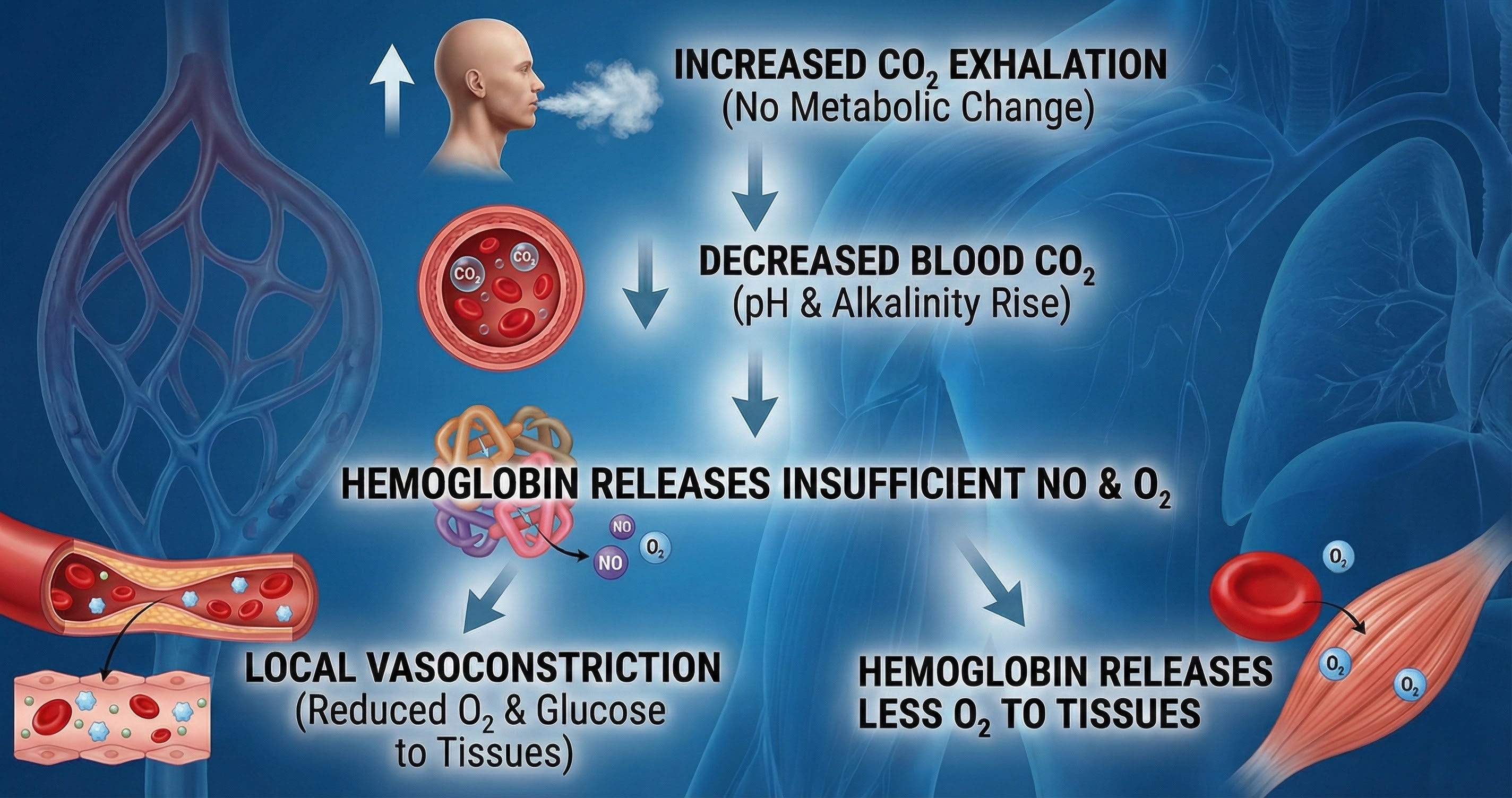

Here is a surprising fact that challenges our intuition about breathing: the "waste gas" we exhale with every breath is actually a master regulator that keeps us alive. As CO2 travels through our bloodstream, it transforms into carbonic acid, a weak acid that serves as the primary buffer for maintaining blood pH at precisely 7.35 to 7.45 (Gilbert, 2005). This delicate balance is so critical that even small deviations can trigger cascading symptoms throughout the body. When we breathe normally, our bodies maintain about 5% CO2 in arterial blood, creating perfect harmony between production and elimination.

The consequences of pH imbalance extend far beyond discomfort. Blood pH below 7.0 leads to severe acidosis, causing disorientation, coma, and potentially death, while pH above 7.7 creates dangerous alkalosis with similar life-threatening outcomes (Gilbert, 2005). Medical professionals sometimes use controlled hyperventilation therapeutically, such as reducing brain swelling after head injuries, demonstrating both the power and the danger of manipulating this fundamental physiological process (Tanaka, Sato, & Kasai, 2020).

How Breathing Maintains Healthy CO2 Levels

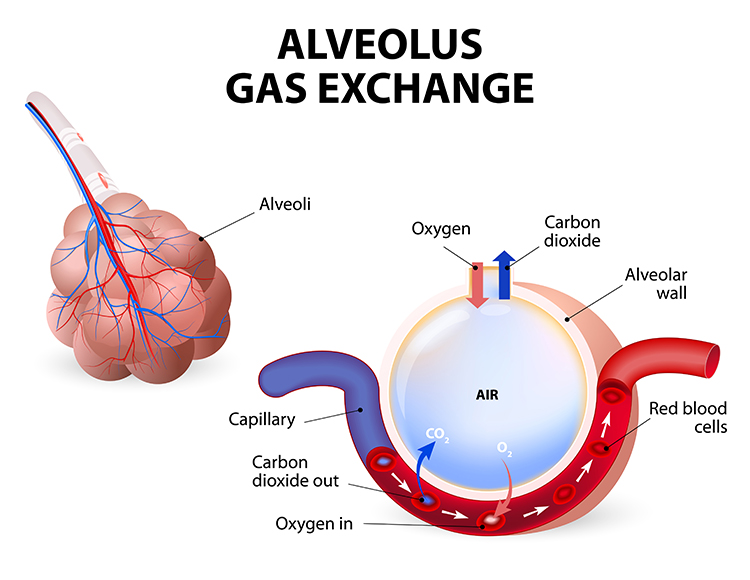

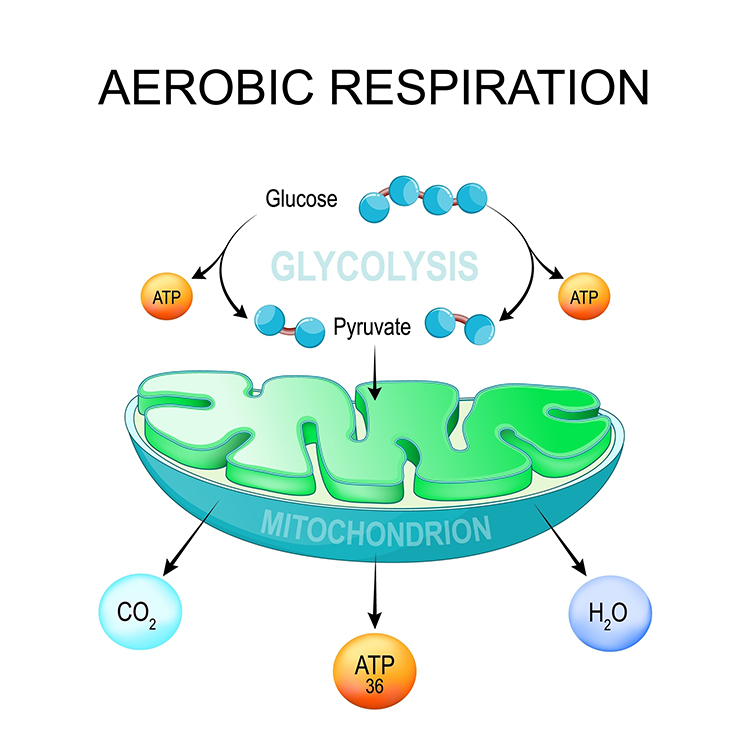

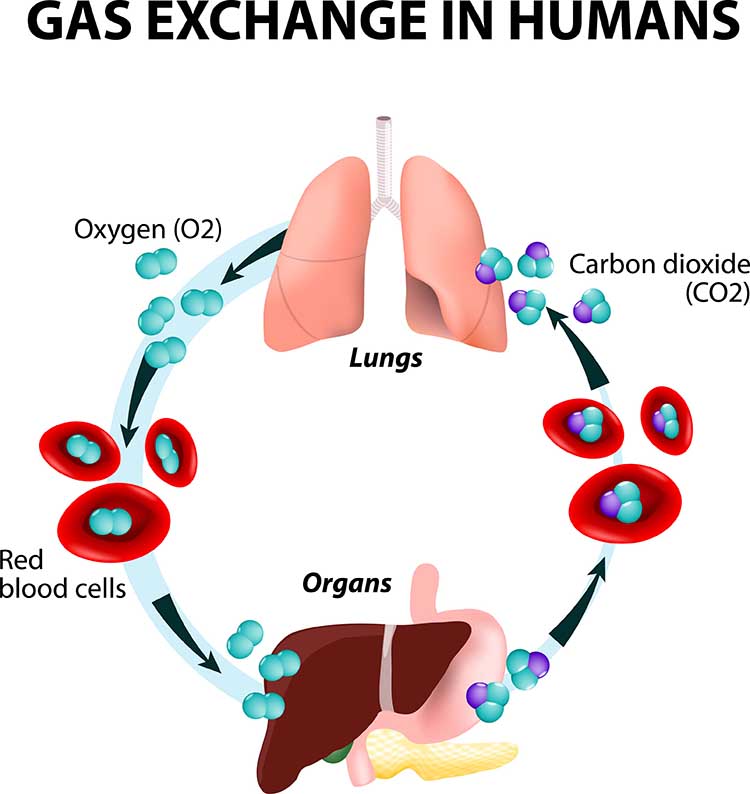

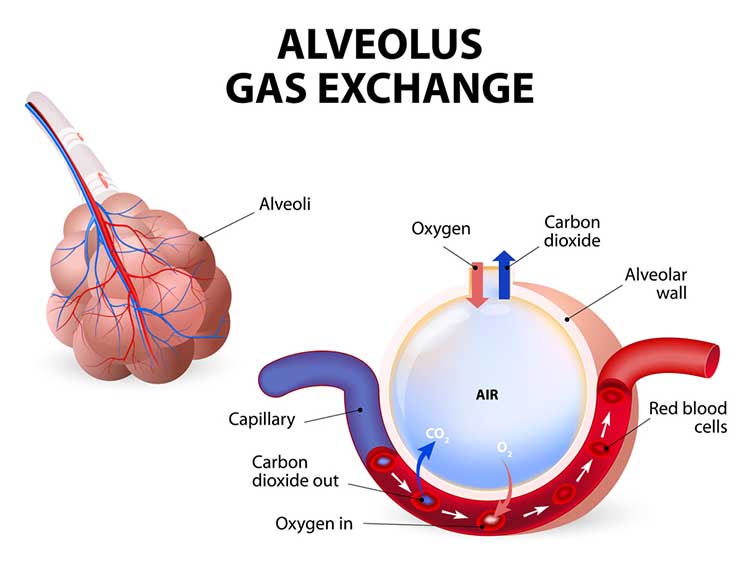

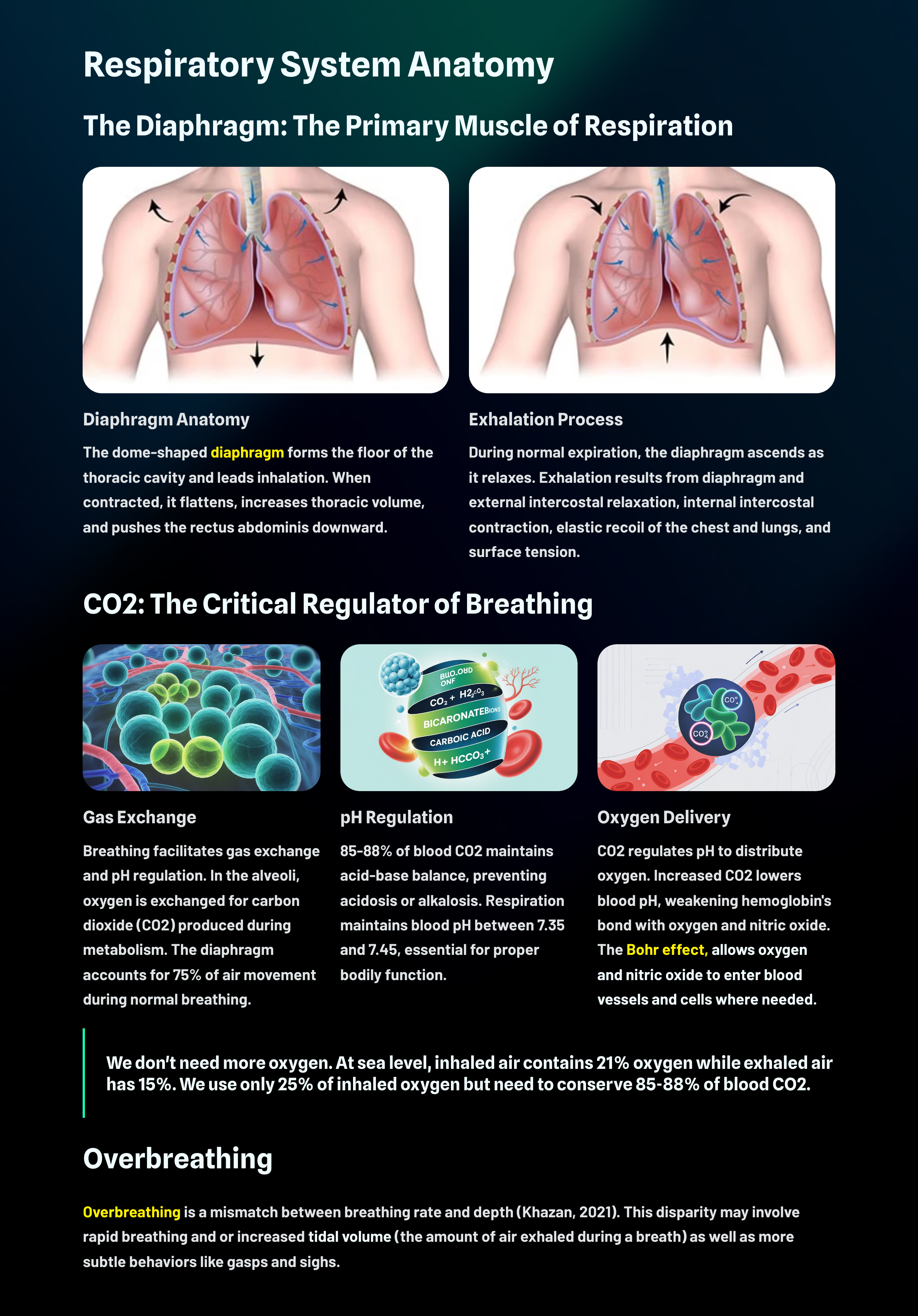

The main functions of breathing are gas exchange and acid-base (pH) regulation. Respiratory system alveoli exchange oxygen for carbon dioxide (CO2) released by cells during metabolism. Alveoli are tiny, thin-walled gas exchange sacs in the lung (Fox & Rompolski, 2022).

CO2: The Unsung Hero of Blood Chemistry

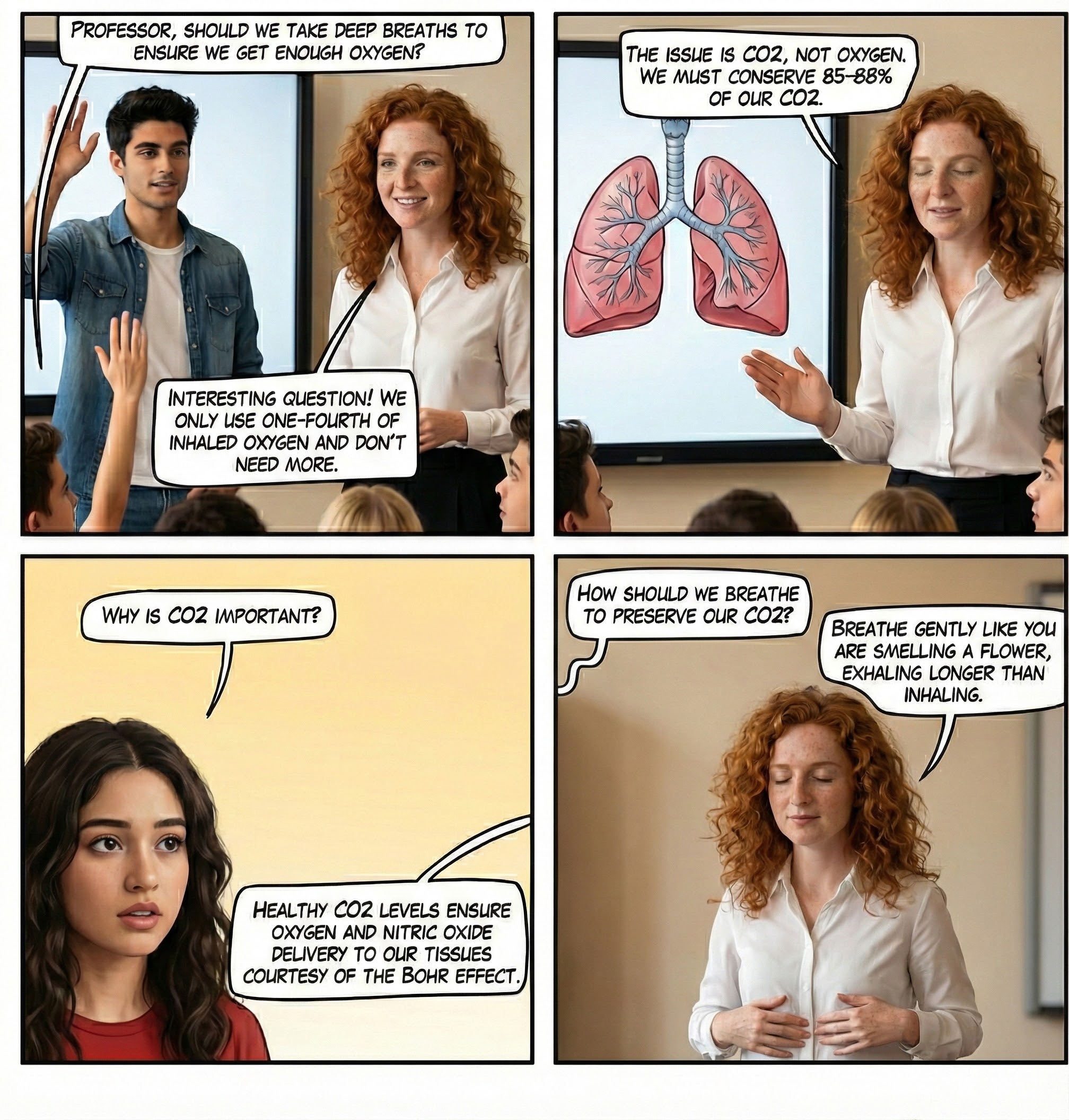

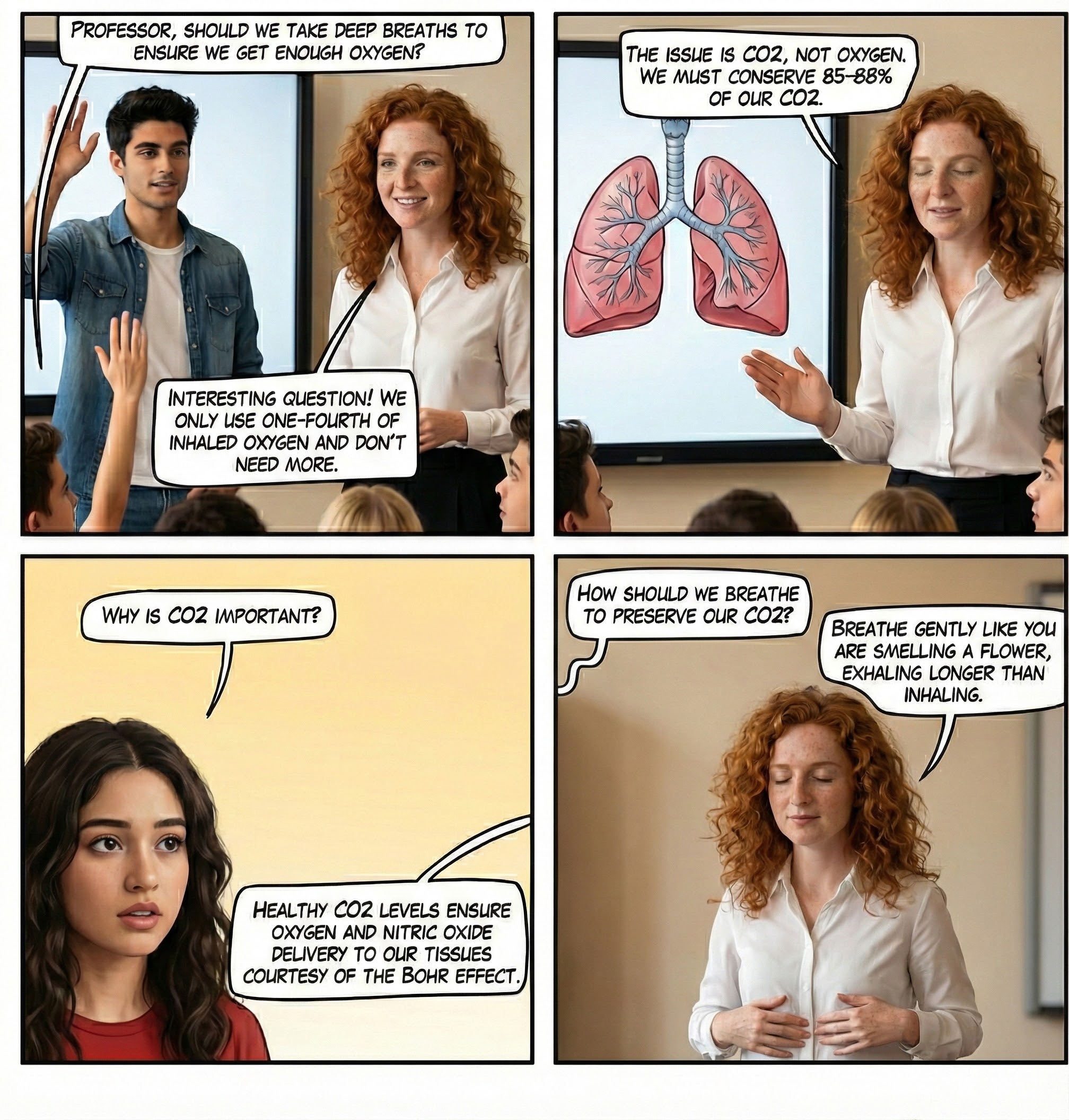

Here is a fact that surprises many people: our body uses 85-88% of blood CO2 to ensure a healthy acid-base balance to prevent our blood from becoming too acidic (acidosis) or basic (alkalosis).

Breathing allows the respiratory system to maintain a blood pH level between 7.35 and 7.45 (Hopkins, Sanvictores, & Sharma, 2022).

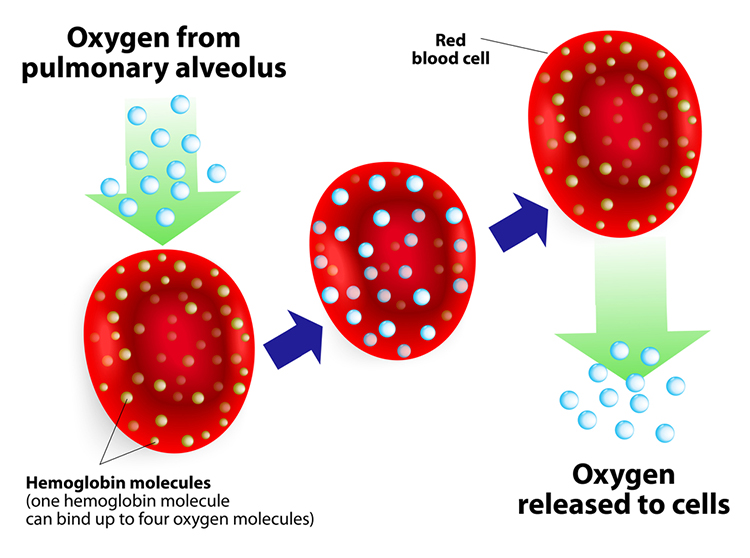

Hemoglobin: The Oxygen Delivery System

Hemoglobin molecules on red blood cells transport oxygen and nitric oxide through the bloodstream. Each human red blood cell contains about 270 million hemoglobin molecules. One hemoglobin molecule can carry four oxygen or nitric oxide molecules. This allows a single red blood cell to carry over 1 billion oxygen molecules under full saturation. Oxygen and nitric oxide compete for attachment to hemoglobin's binding sites.

.jpg)

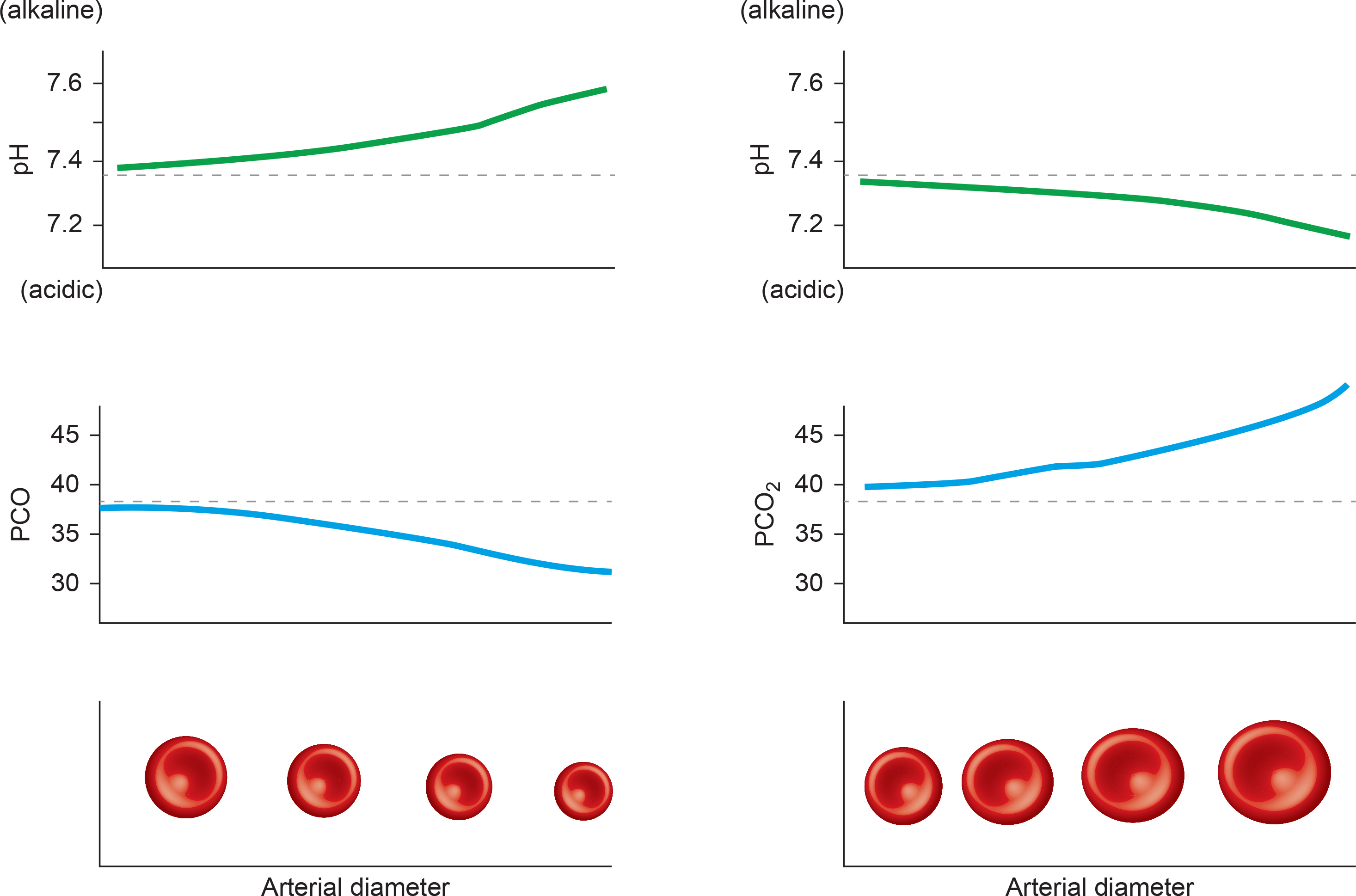

How CO2 Controls pH Levels

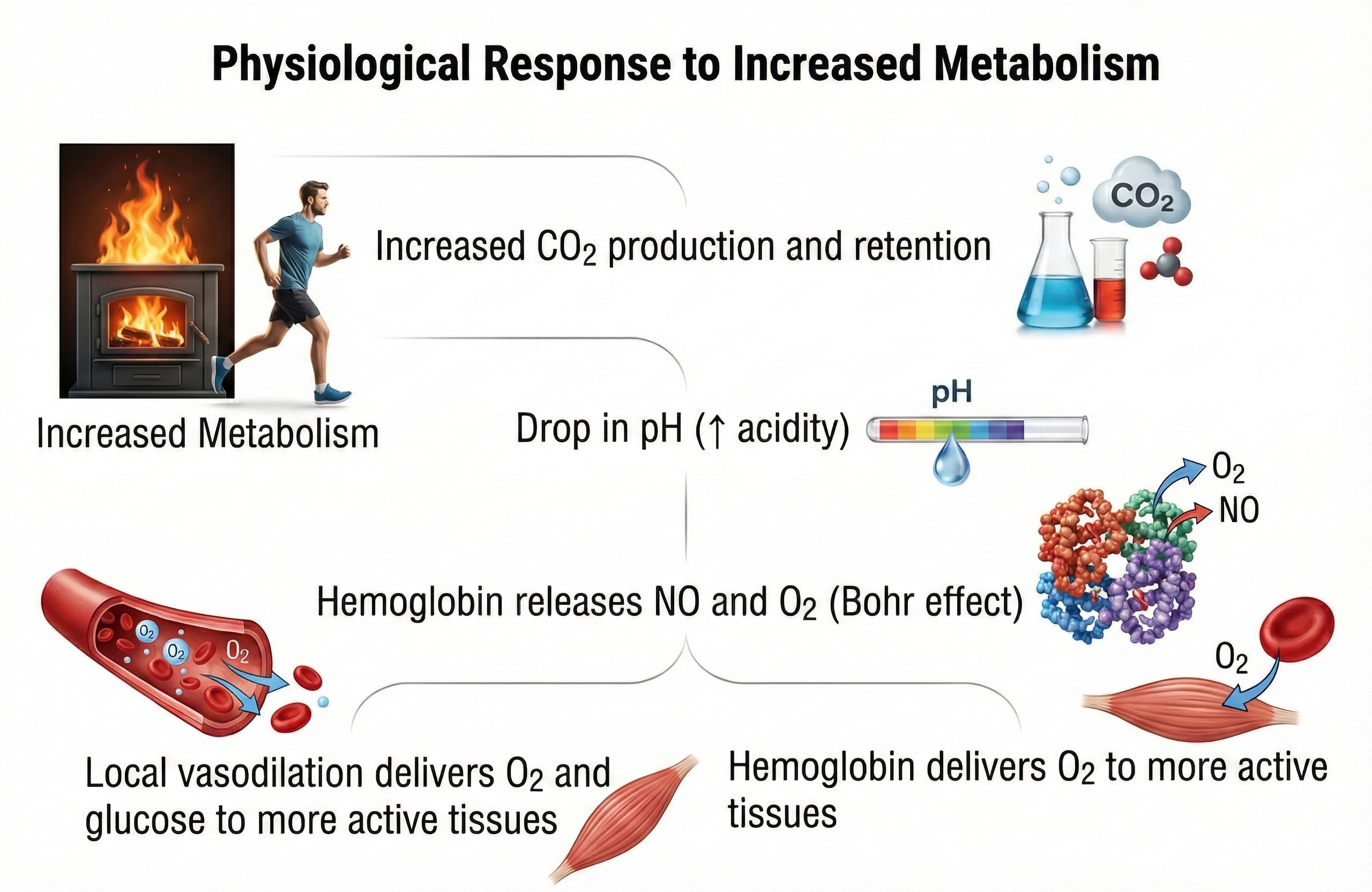

CO2 regulates pH levels to distribute oxygen and nitric oxide. When cells are active, they produce CO2.

Inspiratory muscle activity (such as diaphragm and the external intercostals) increases metabolism. Muscles break down glucose and fatty acids to power contraction, which produces CO2 (Milic-Emili & Tyler, 1963; Swensen, 2017).

Slow-paced breathing with low tidal volumes retains more CO2 in arterial blood than when overbreathing. Tidal volume (TV) is the amount of air inhaled or exhaled during a normal breath (Fox & Rompolski, 2022).

In both cases, rising CO2 lowers blood pH (more acidic), weakening the bond between hemoglobin and oxygen. Oxygen loss changes hemoglobin's shape, destabilizing its bond with NO. Oxygen and NO release support physical activity.

Breathing plays a pivotal role in regulating the pH level of the blood. By adjusting the rate and depth of breathing, the body can control the amount of CO2 expelled, directly influencing the blood's acidity. This regulation is vital for the proper functioning of enzymes and metabolic processes (Guyenet & Bayliss, 2015).

The table below shows how CO2 regulates blood pH and is redrawn from Gilbert (2005).

Breathing supports the efficient exchange of gases in the lungs, where oxygen is absorbed into the bloodstream, and CO2 is released for exhalation. This exchange is crucial for metabolic activities and energy production within cells (Hsia, 2023).

The Bohr Effect: Why CO2 Matters for Oxygen Delivery

The Bohr effect enables oxygen and nitric oxide to leave their hemoglobin carrier to enter blood vessels and cells (Riggs, 1988). Think of it this way: CO2 acts like a key that unlocks oxygen from hemoglobin. Without adequate CO2, oxygen stays bound to hemoglobin and cannot reach the tissues that need it.

Recent research has demonstrated that slow-paced breathing at approximately 6 breaths per minute, often called resonance breathing, optimizes the balance between oxygen delivery and CO2 retention (Laborde et al., 2022). A comprehensive meta-analysis of 223 studies found that voluntary slow breathing consistently increases vagally-mediated heart rate variability both during breathing practice and immediately afterward, with effects persisting after multi-session interventions (Laborde et al., 2022). This finding has profound clinical implications: slow-paced breathing appears to enhance parasympathetic nervous system activity, which in turn supports better oxygen utilization through the Bohr effect.

Jung and colleagues (2024) demonstrated that slow breathing at 6 breaths per minute not only increases heart rate variability but also enhances connectivity between the amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex, improving emotional regulation. Interestingly, larger effects were found in older adults and women. These findings suggest that breathing rate influences far more than gas exchange; it appears to modulate the brain circuits involved in stress responses and emotional processing.

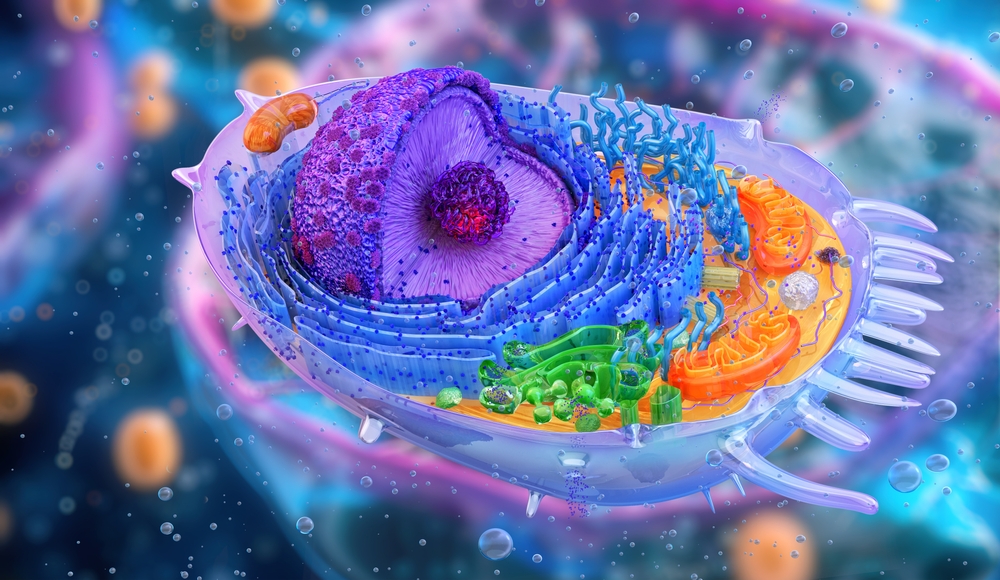

Oxygen's Role in Cellular Energy Production

In cells, oxygen supports mitochondrial ATP production and metabolism to support activity.

Nitric Oxide: The Vasodilator

Slow-paced breathing releases more nitric oxide as blood CO2 rises and pH falls, resulting in vasodilation.

Nitric oxide dilates capillaries and arterioles, increasing oxygen, nitric oxide, and nutrient delivery via blood flow.

Comprehension Questions: Respiratory Physiology

- Why is CO2 considered the "master regulator" of oxygen delivery rather than just a waste gas?

- A client asks you why slow breathing is better than fast breathing. Using the Bohr effect, how would you explain this?

- What percentage of blood CO2 does the body retain for acid-base balance, and why is this important?

- How does nitric oxide contribute to healthy circulation, and what breathing pattern promotes its release?

Healthy Breathing Roadmap

Listen to a mini-lecture on Healthy Breathing RoadmapDr. Khazan explains internal respiration.

Why We Need to Conserve CO2, Not Get More Oxygen

Here is a counterintuitive truth that surprises many clients: we do not need more oxygen! (Khazan, 2021). Near sea level, the air healthy clients inhale contains 21% oxygen, while the air they exhale has 15%. We only use 25% of inhaled oxygen and do not need more. We need to conserve blood CO2 by retaining 85-88% of it.

Breathing Serves More Than Gas Exchange

The respiratory system also delivers odorants to the olfactory epithelium, produces the airway pressure required for speech, anticipates cognitive and skeletal muscle metabolic demands, and helps to modulate systems regulated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), especially the cardiovascular system. Respiration is an important regulator of heart rate variability, consisting of beat-to-beat changes in the heart rhythm (Lorig, 2007). Check out the YouTube video The Respiratory System.

The Respiratory Cycle

We breathe about 20,000 times a day. Typical adult resting breathing rates are 12-20 breaths per minute (bpm; Saatchi et al., 2025). Disorders that affect respiration may raise rates to 18-28 bpm (Fried, 1987; Fried & Grimaldi, 1993).

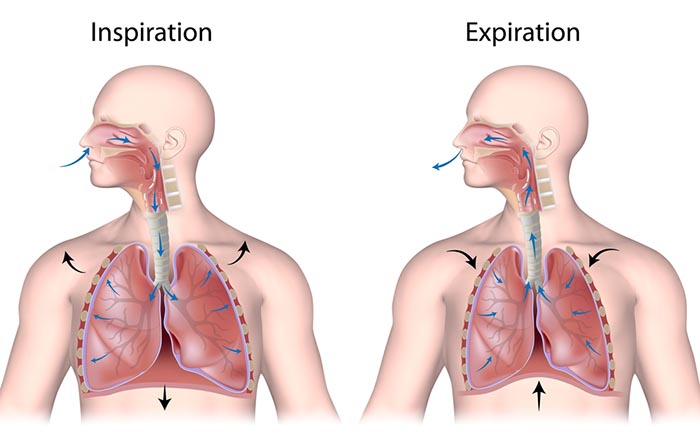

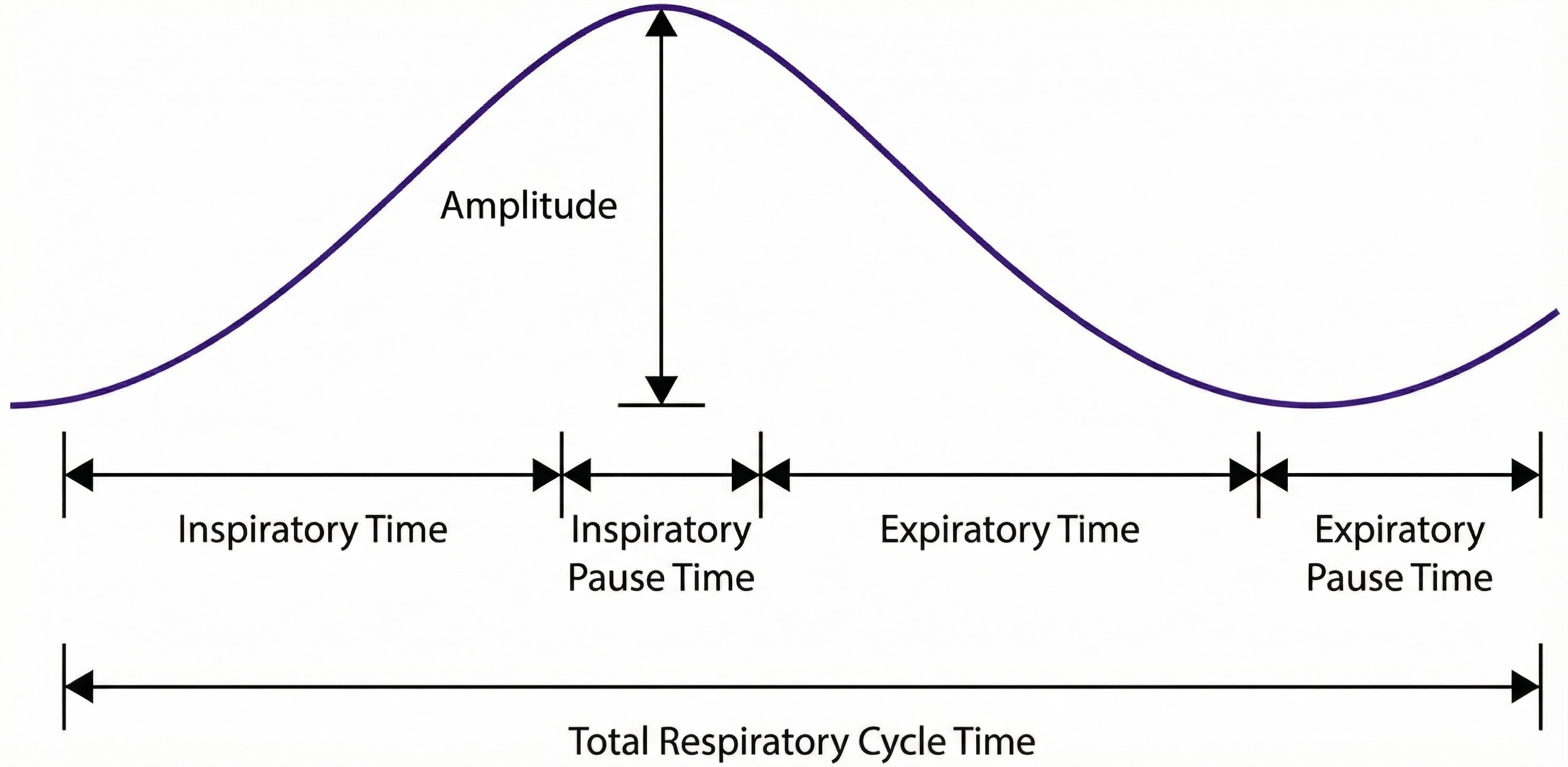

The respiratory cycle consists of inhalation (breathing in) and exhalation (breathing out), controlled by separate mechanisms.

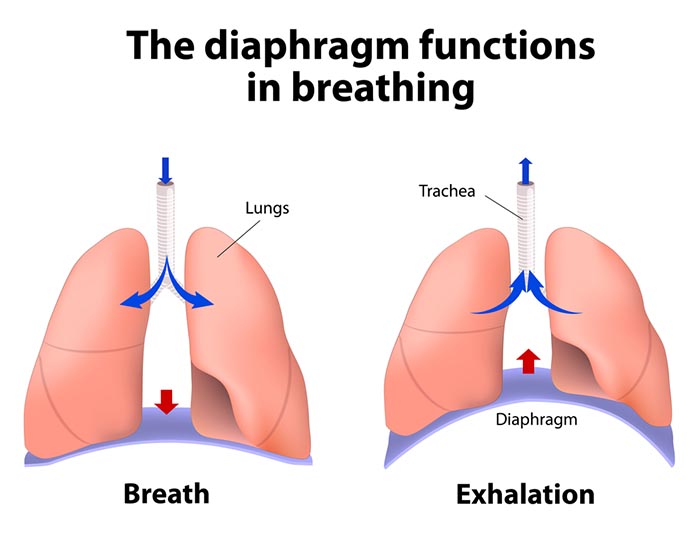

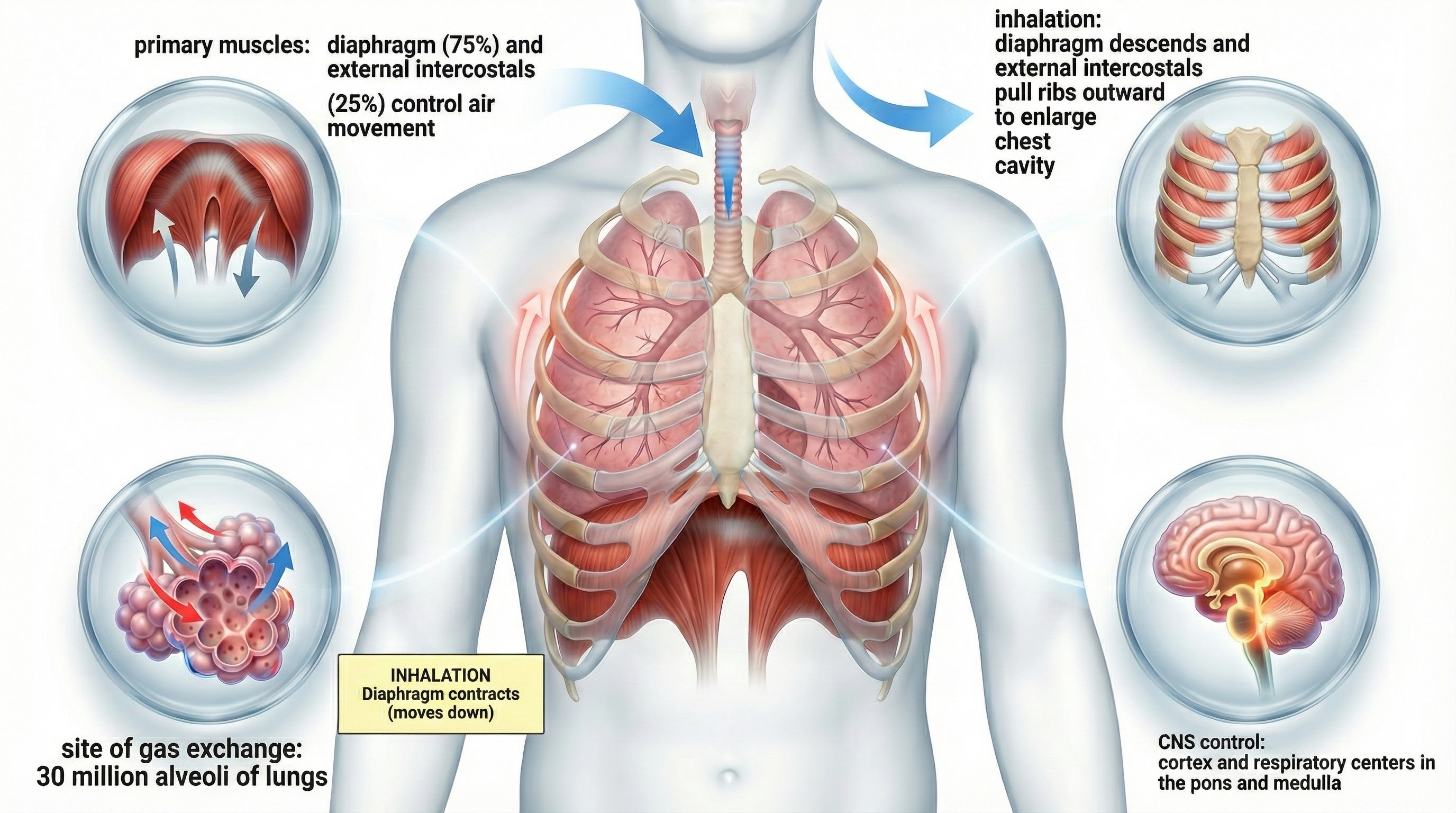

The lungs cannot inflate themselves since they lack skeletal muscles. Instead, they passively inflate by creating a partial vacuum by the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles (Gevirtz, Schwartz, & Lehrer, 2016).

During inhalation, contraction by the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles ventilate the lungs.

The dome-shaped diaphragm muscle plays the lead role during inhalation. The diaphragm comprises the floor of the thoracic cavity. When the diaphragm contracts, it flattens, and its dome drops, increasing thoracic cavity volume. Contraction of the diaphragm pushes the rectus abdominis muscle of the stomach down and out.

In the animation below, watch the lungs inflate as the diaphragm descends.

In relaxed breathing, a 1-cm descent creates a 1-3 mmHg pressure difference and moves 500 milliliters of air. In labored breathing, a 10-cm descent produces a 100-mmHg pressure difference and transports 2-3 liters of air. The diaphragm accounts for about 75% of air movement into the lungs during relaxed breathing.

A systematic review and meta-analysis by Abdullahi, Wong, and Ng (2024) found that diaphragmatic breathing exercise significantly improves respiratory function in stroke patients, with marked improvements in forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume, and peak expiratory flow. These findings extend beyond stroke rehabilitation to suggest that diaphragmatic breathing training can benefit anyone seeking to optimize respiratory mechanics and CO2 retention.

Research by Vranich and colleagues (2025) introduced the Breathing IQ, an anthropometric index that measures the efficiency of diaphragmatic breathing by assessing abdominothoracic expansion during inhalation and exhalation. In a study of 384 participants, a single 90-minute intervention improved breathing mechanics dramatically, with the percentage of participants demonstrating efficient diaphragmatic breathing increasing from just 3.7% to 26.6%. This finding suggests that dysfunctional breathing patterns are common but highly correctable with proper instruction.

The external intercostals play a supporting role during inhalation. External intercostal muscle contraction pulls the ribs upward and enlarges the thoracic cavity. The external intercostals account for about 25% of air movement into the lungs during relaxed breathing.

The contraction of the diaphragm and the external intercostals expands the thoracic cavity, increases lung volume, and decreases the pressure within the lungs below atmospheric pressure. This pressure difference causes air to inflate the lungs until the alveolar pressure returns to atmospheric pressure.

During forceful inhalation, accessory muscles of inhalation (sternocleidomastoid, scalene, pectoralis major and minor, serratus anterior, and latissimus dorsi) also contract (Khazan, 2021).

How the Dome-Shaped Diaphragm Produces Exhalation

The relaxation of the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles, contraction of the internal intercostals, the elastic recoil of the chest wall and lungs, and surface tension produce exhalation during relaxed breathing. When the diaphragm relaxes, its dome moves upward. When the external intercostals relax, the ribs move downward. These changes reduce the thoracic cavity volume and the lungs and increase the pressure within the lungs above atmospheric pressure. This pressure difference causes air to deflate the lungs until the alveolar pressure returns to atmospheric pressure.

Forceful exhalation during exercise recruits the rectus abdominis, external and internal obliques, and transversus abdominis abdominal muscles (Khazan, 2021; Lorig, 2007; Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

The BioGraph® Infiniti display below shows healthy inhalation and exhalation in which the abdomen gradually expands and then contracts.

Types of Respiration

The term respiration refers to external, internal, and cellular processes. External respiration transports gases in and out of our lungs. Internal respiration transports oxygen from the air we inhale, delivers it to our cells, and returns metabolic CO2 to the lungs for 12-15% to be exhaled and 85-88% retained to regulate pH (Khazan, 2021).

Respiratory gases are exchanged (between the lungs and blood) across the respiratory membrane, comprised of the alveolar and capillary walls.

The lungs contain about 300 million pulmonary alveoli (air sacs) that create an incredible 760 ft2 surface for gas exchange (Fox & Rompolski, 2022).

The alveoli collapse like "wet balloons" during normal breathing. Since deflated alveoli cannot absorb normal oxygen levels, the brain triggers sighs to reopen these air sacs. Humans initiate sighs every 5 minutes to increase oxygen delivery and activate the brain through double inhalation (Long, 2016).

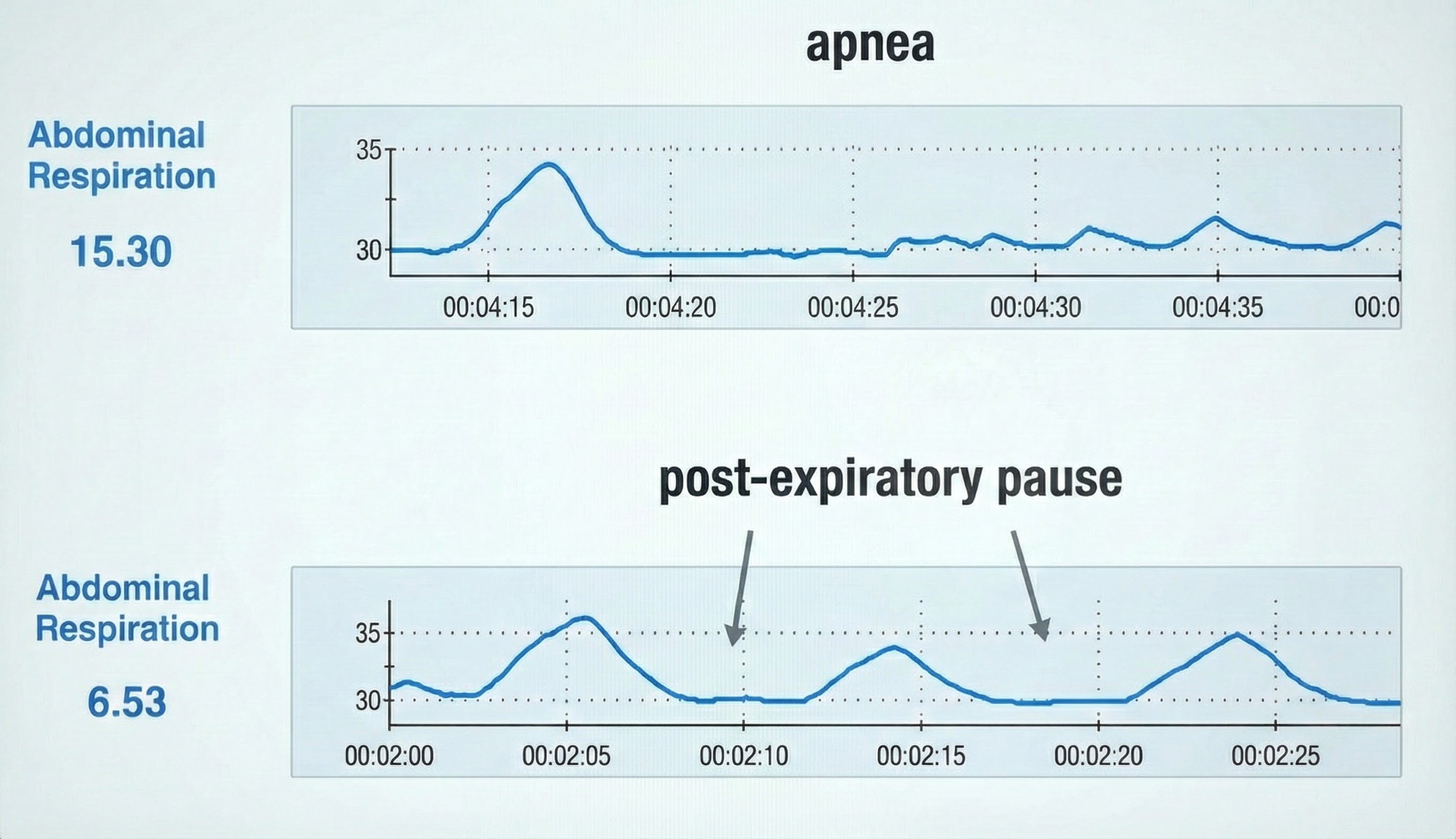

The respiratory cycle consists of an inspiratory phase, inspiratory pause, expiratory phase, and expiratory pause. Abdominal respirometer excursion, which indexes respiratory amplitude (the peak-to-trough difference), is often greatest during the inspiratory pause. The diagram below was adapted from Stern, Ray, and Quigley (1991).

Clinicians should examine all components of the respiratory cycle, not just respiration rate, to understand their clients' respiratory mechanics. Everyday activities like speaking and writing checks may affect individual components differently. Apnea, breath suspension, lowers respiration rate. Clinicians teaching effortless breathing training may instruct their clients to lengthen the expiratory pause with respect to the inspiratory pause. Simple inspection of their respiration rates will not show whether they have successfully changed the relative durations of these two pauses. Finally, in heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback, clinicians encourage slow (5-7 bpm) and rhythmic breathing.

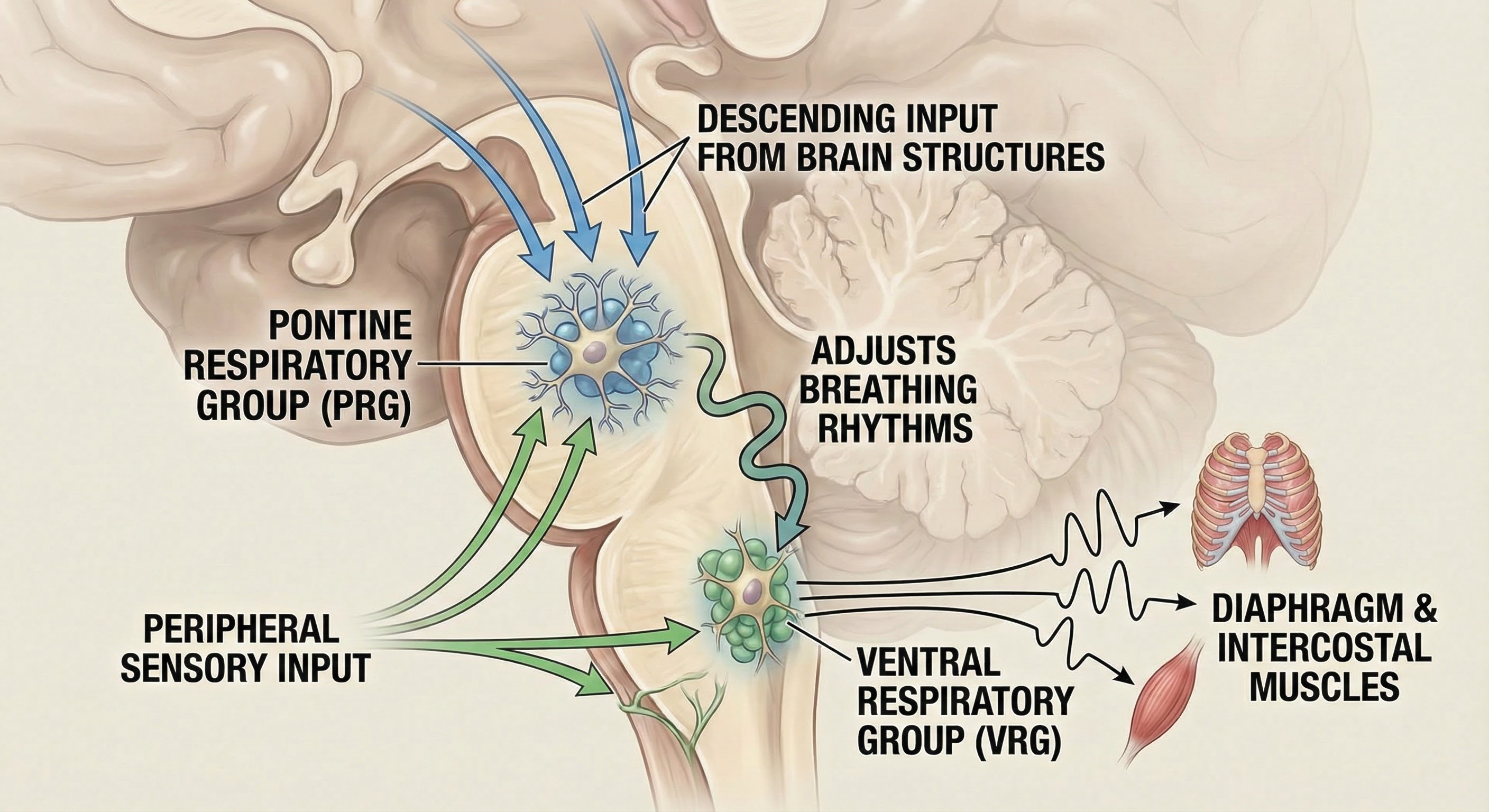

Neural Control of Respiration

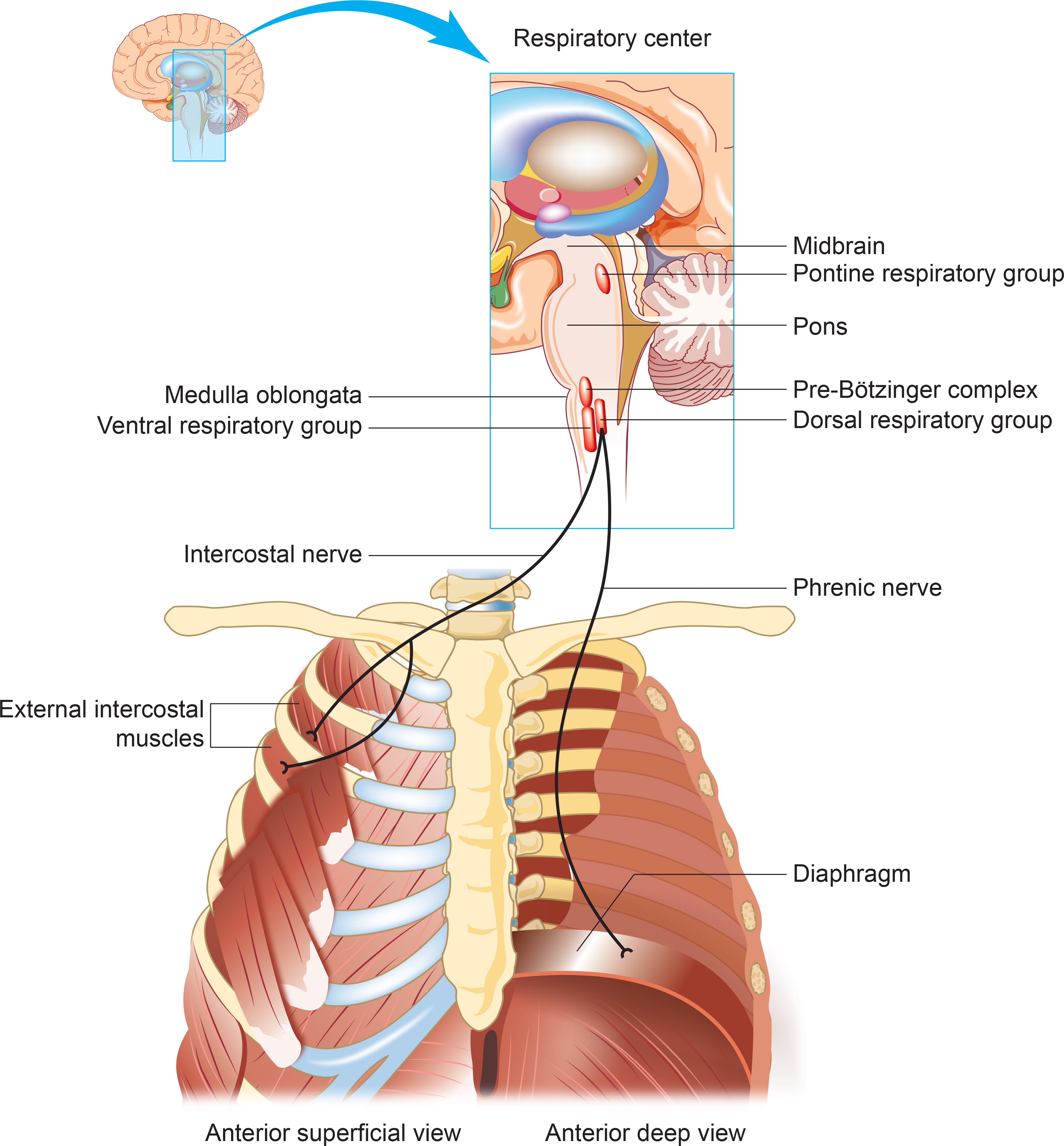

Respiration is controlled by a respiratory center in the medulla and pontine respiratory group. The dorsal respiratory group (DRG) and ventral respiratory group (VRG) are neuron clusters in two medulla regions. Pacemaker cells located in the VRG (analogous to the heart's sinoatrial node) organize the basic breathing rhythm. Check out the Khan Academy YouTube video The Respiratory Center.

The Medulla: DRG and VRG

The DRG's Role in Breathing

The DRG collects information from peripheral stretch and chemoreceptors and distributes it to the VRG to modify its breathing rhythms. The DRG is responsible for normal quiet breathing.

The majority of VRG neurons are inactive at this time. DRG impulses to the diaphragm and external intercostals begin in weak bursts that strengthen for about 2 seconds and then stop. This stimulation causes muscle contraction and inhalation. After 2 seconds of DRG inactivity, the diaphragm and external intercostals relax for 3 seconds so that the lungs and chest wall can passively recoil to allow the next breathing cycle.

During forceful breathing, DRG neurons activate the VRG, which stimulates the diaphragm, sternocleidomastoid, pectoralis minor, scalene, and trapezius muscles to contract (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

The VRG's Role in Breathing

The phrenic and intercostal nerves transmit VRG inspiratory neuron action potentials to the diaphragm and external intercostal muscles. The contraction of these muscles expands the thoracic cavity and inflates the lungs.

VRG pacemaker cells influence the rate of DRG action potentials. VRG expiratory neurons inhibit DRG inspiratory neuron firing. Exhalation passively results from diaphragm and external intercostal muscle relaxation and recoil by the chest wall and lungs. The DRG and VRG neurons' continuous reciprocal activity results in a 12-15 bpm respiratory rate, with 2-second inspiratory and 3-second expiratory phases.

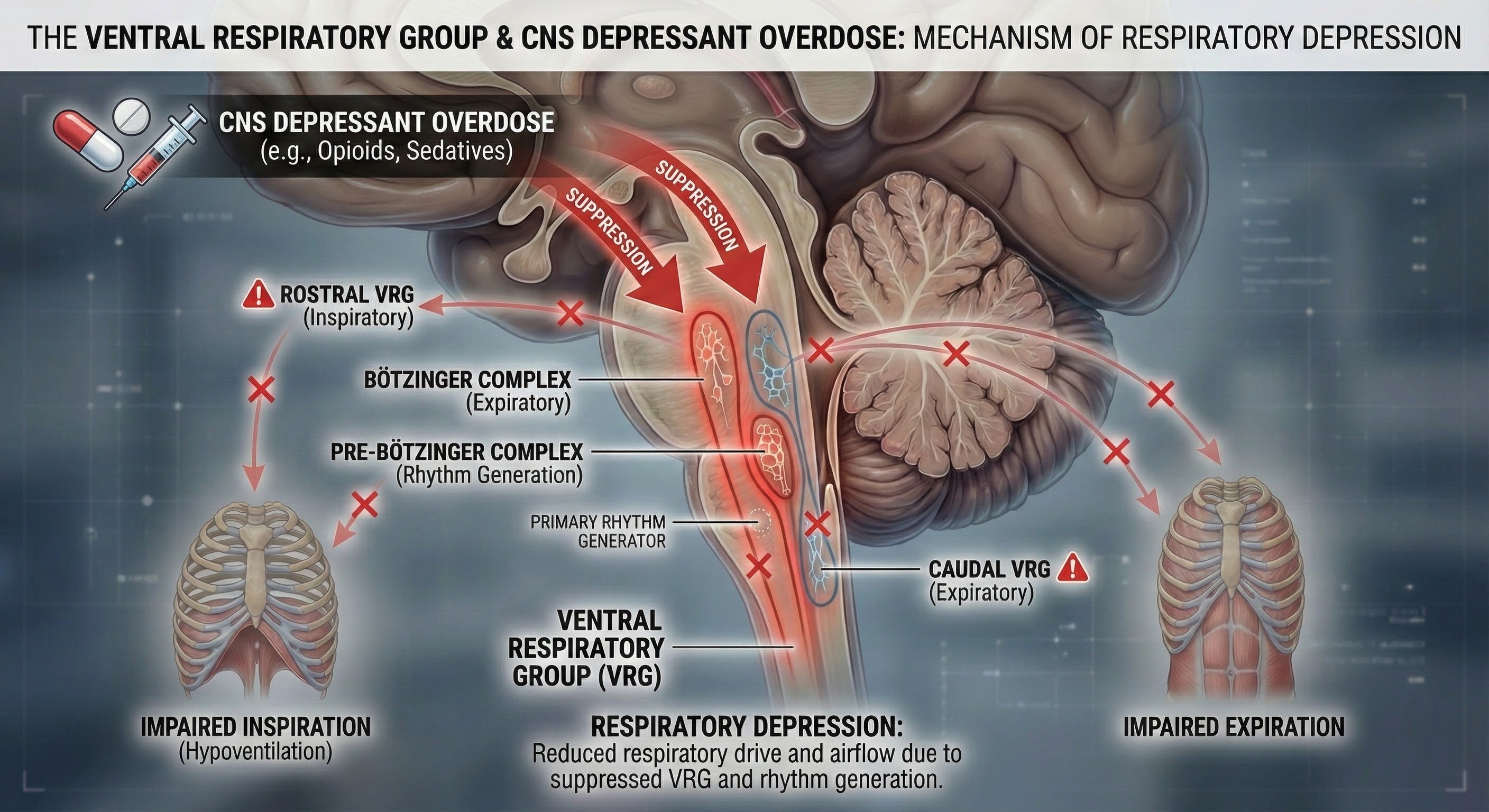

Why Drug Overdoses Can Be Lethal

An overdose of a CNS depressant like alcohol or morphine can completely inhibit VRG neurons in the medulla and stop breathing.

The Pons: The Respiratory Group's Role

The pontine respiratory group adjusts VRG breathing rhythms based on descending input from brain structures and peripheral sensory input.

Research has revealed that breathing biofeedback can modify these neural control mechanisms with lasting therapeutic effects. Tolin and colleagues (2017) conducted a multisite trial demonstrating that capnometry-guided respiratory intervention, which provides real-time feedback on end-tidal CO2 and respiration rate, achieved an 83% response rate and 54% remission rate for panic disorder, with benefits maintained at 12-month follow-up. This intervention works by helping patients recognize when their breathing exceeds metabolic needs and training them to restore healthy CO2 levels.

The pontine respiratory group modifies breathing during activities like exercise, sleep, and speech (Marieb & Hoehn, 2019). The body's cells require about 200 ml of oxygen at rest. This demand increases 15-20 times during strenuous exercise; 30 times for elite athletes.

The Cerebral Cortex's Role in Breathing

Cortical control of respiratory centers in the medulla and pons allows us to voluntarily stop or change our breathing pattern. This voluntary control protects against lung damage from water or toxic gases.

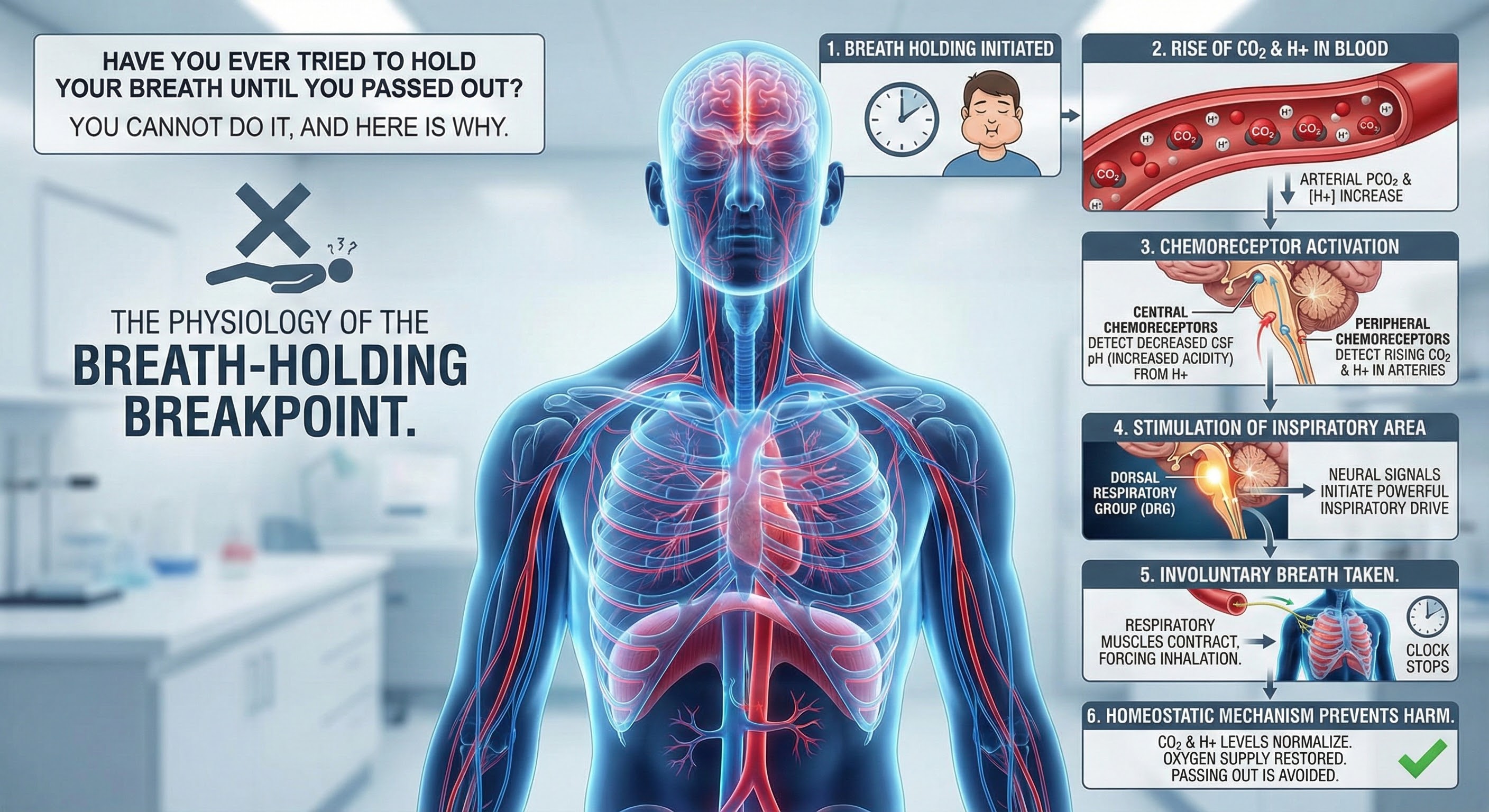

Why You Cannot Hold Your Breath Indefinitely

Have you ever tried to hold your breath until you passed out? You cannot do it, and here is why. The rise of CO2 and H+ in the blood limits our ability to suspend breathing by stimulating the inspiratory area when a critical level is reached. When chemoreceptors monitoring cerebrospinal fluid pH detect decreased pH (greater acidity), the dorsal respiratory group of the medulla initiates the next breath. This homeostatic mechanism prevents us from harming ourselves by holding our breath (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Comprehension Questions: Neural Control of Respiration

- What is the relationship between the DRG and VRG in controlling normal quiet breathing versus forceful breathing?

- Why is it impossible to voluntarily hold your breath until you lose consciousness?

- How does the pontine respiratory group modify breathing during different activities?

- Explain why a CNS depressant overdose can be fatal in terms of respiratory control.

Mouth Versus Nose Breathing: What the Research Shows

Inhaling through the mouth results in greater dead space and airway resistance compared to nose breathing (Tanaka, Morikawa, & Honda, 1988).

Mouth breathing is fine when there is a need for large amounts of air, such as exercising, or when the nose is stuffed.

The nose acts as a natural filter, trapping dust, allergens, and other particulate matter before they can enter the lungs (Bjermer, 1999). Nasal passages also humidify and warm the air, protecting the respiratory tract from irritation and infection (Naclerio et al., 2007). Mouth breathing bypasses these natural defenses (Martel et al., 2020).

Inhaling through the nose releases nitric oxide, a gas that enhances the body's ability to transport oxygen by dilating blood vessels, to the lungs. This process improves oxygen uptake in the blood, contributing to better overall cardiovascular health. Mouth breathing does not offer this benefit (Kimberly et al., 1996; Watso et al., 2023).

Emerging research continues to highlight the cardiovascular benefits of nasal breathing. Watso and colleagues (2023) demonstrated that acute nasal breathing lowers blood pressure and increases parasympathetic contributions to heart rate variability in young adults. This effect appears mediated by nitric oxide released from the paranasal sinuses during nasal inhalation. Unlike mouth breathing, nasal breathing delivers this vasodilatory gas directly to the lungs, where it enhances oxygen uptake and improves overall cardiovascular function.

For individuals recovering from long COVID, slow breathing interventions show promise for restoring autonomic function. Marcella and colleagues (2024) found that healthcare workers with long COVID exhibited reduced heart rate variability compared to healthy controls, but slow-paced breathing significantly attenuated these abnormalities, suggesting that breathing exercises may help restore vascular function and reduce long-term cardiovascular risk in this population.

Chronic mouth breathing can lead to dry mouth, increasing the risk of dental decay and gum disease because saliva, which protects against bacteria and aids digestion, is reduced (Tamkin, 2020). Furthermore, the altered posture of the tongue and jaw can contribute to malformations in children, such as dental malocclusions and facial deformities (Lin et al., 2022).

Inhaling through the nose helps regulate the volume of inhaled air and maintains adequate levels of CO2 in the blood, which is necessary to efficiently release oxygen from hemoglobin to the body's tissues (Prisca et al., 2024). Mouth breathing can lead to overbreathing and a reduction in CO2 levels, impairing oxygen delivery (LaComb et al., 2017; Tanaka, Morikawa, & Honda, 1988).

Exhaling through the nose cannot be regulated in the way that pursed-lips breathing can. Exhaling through pursed lips reduces inappropriate breathing volume when the cause is emotion rather than exercise demand.

Many people favor practicing breathing by inhaling through the nose and exhaling through the mouth, so that is a compromise between the two that makes sense.

Inhalation through the nose, but not the mouth, activates the amygdala, hippocampus, and olfactory cortex neurons.

Nasal inhalation may accelerate our response to physical threats and impact fear and memory. During panic attacks, breathing is faster, and we spend more time inhaling (Zelano et al., 2016). Check out the YouTube video How you breathe affects memory and fear.

Disordered Breathing

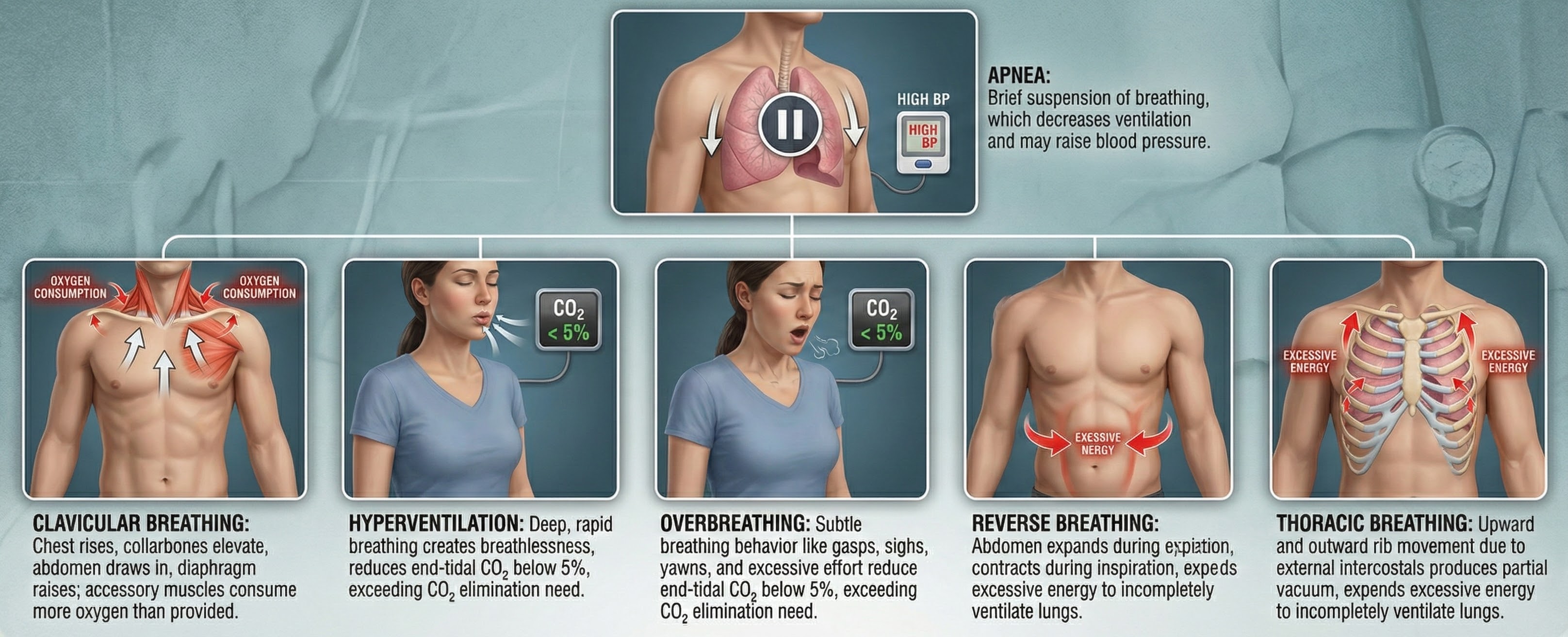

Listen to a mini-lecture on Disordered BreathingClinicians encounter six abnormal breathing patterns which reduce oxygen delivery to the lungs: thoracic breathing, clavicular breathing, reverse breathing, overbreathing, hyperventilation, and apnea.

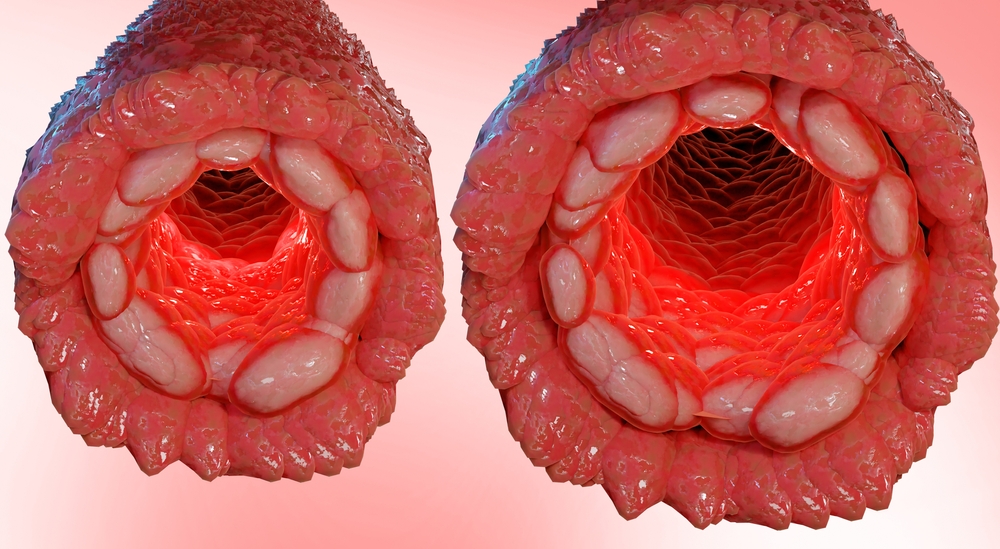

Thoracic Breathing: When the Chest Does All the Work

In thoracic breathing, the chest muscles are mainly responsible for breathing. The external intercostals lift the rib cage up and out. The diaphragm is pushed upward as the abdomen is drawn in. Upward and outward movement of the ribs enlarges the thoracic cavity producing a partial vacuum. Negative pressure expands the lungs but is too weak to ventilate their lower lobes. Thoracic breathing reduces ventilation since the lower lobes receive a disproportionate share of the blood supply due to gravity.

Thoracic breathing expends excessive energy, incompletely ventilates the lungs, and strains our accessory muscles.

In the BioGraph® Infiniti screen below, the abdominal (blue trace) strain gauge exhibits minimal excursion, and the respiration rate exceeds the desired 5-7 breaths-per-minute range.

Are you a thoracic breather? Place your left hand on your chest and your right hand on your navel. If both hands shallowly rise and fall at about the same time, you are breathing thoracically.

Clavicular Breathing: The Oxygen Thief

In clavicular breathing, the chest rises, and the collarbones are elevated to draw the abdomen in and raise the diaphragm (Khazan, 2021). Clavicular breathing may accompany thoracic breathing. Patients may breathe through their mouths to increase air intake. This pattern provides minimal pulmonary ventilation. Over time, the accessory muscles (sternocleidomastoid, pectoralis minor, scalene, and trapezius) use more oxygen than clavicular breathing provides.

Clavicular breathing may be accompanied by thoracic and mouth breathing, produce an oxygen deficit, reduce CO2, and cause overbreathing.

In the BioGraph® Infiniti screen below, the purple trace represents the chest strain gauge, and the red trace represents accessory SEMG activity. Note the rapid shallow chest movement and fluctuating accessory SEMG values increase with the shoulder elevation accompanying each inhalation.

Are you a clavicular breather? Have an observer lightly place one hand on your shoulder (the observer's shoulder must be relaxed). If this hand rises as you inhale, you are showing clavicular breathing.

Reverse Breathing: The Backwards Pattern

Reverse breathing, where the abdomen expands during exhalation and contracts during inhalation, often accompanies thoracic breathing and results in incomplete ventilation of the lungs.

In the BioGraph® Infiniti screen below, the client starts at the left with inhalation, followed by exhalation. Note how the stomach contracts during inhalation (falling blue trace) and expands during exhalation (rising blue trace). This pattern is the opposite of healthy breathing.

Are you a reverse breather? If the hand on your stomach falls and the hand on your chest rises when you inhale, you are reverse breathing. Reverse breathing expends excessive energy and incompletely ventilates the lungs.

Overbreathing: The Silent Saboteur

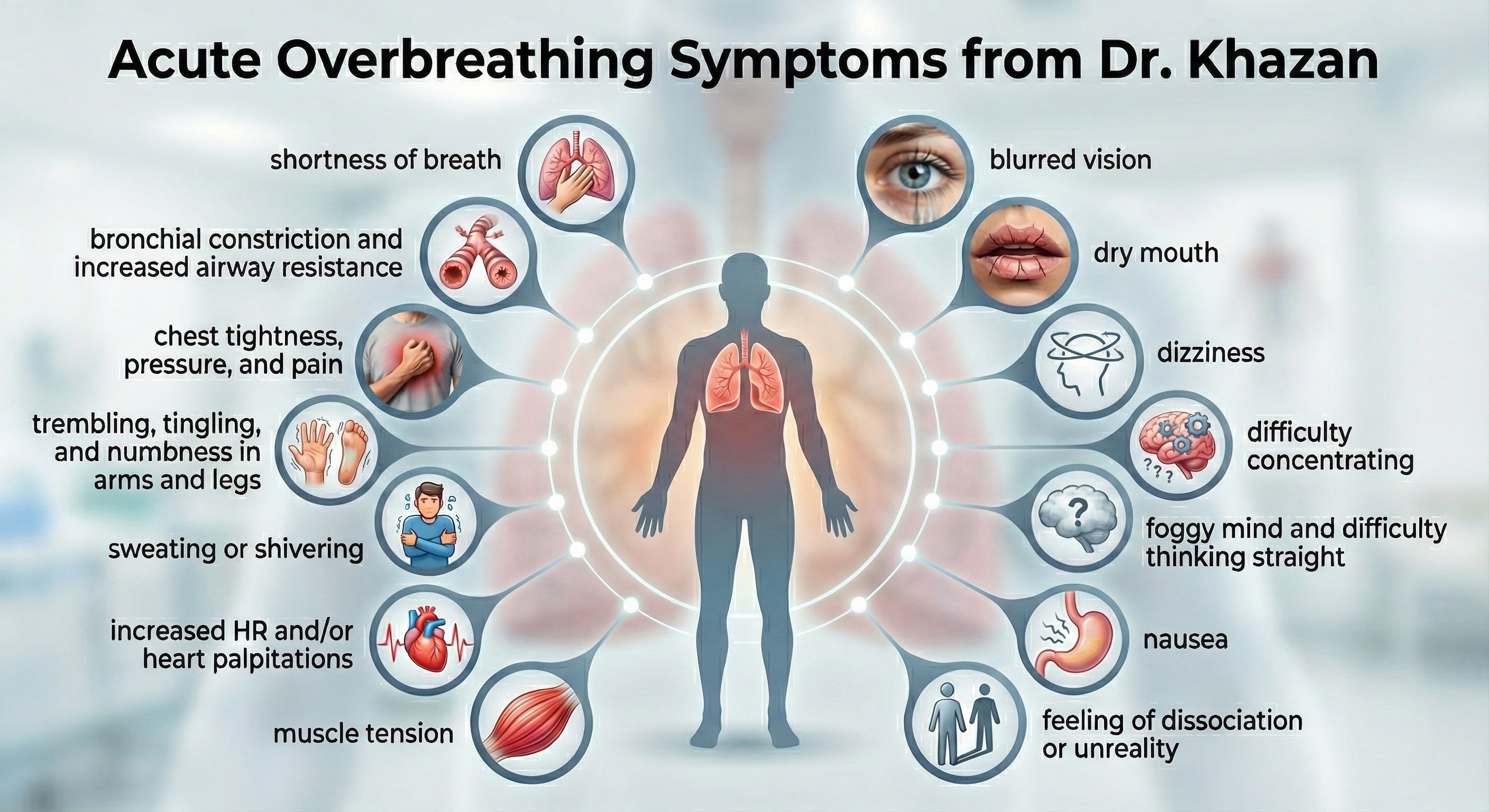

Overbreathing is a mismatch between breathing rate and depth (Khazan, 2021). This disparity may involve rapid breathing and/or increased tidal volume (the amount of air exhaled during a breath) as well as more subtle behaviors like gasps and sighs.

Here is a fact that surprises many people: clinical hyperventilation does not look like what most imagine. Forget the dramatic gasping and paper bag scenes from movies. Clinical hyperventilation is simply breathing that exceeds current metabolic needs, and it can be so subtle that even trained observers might miss it (Gilbert, 2005). The real problem is not that people breathe too fast, but that they exhale more carbon dioxide than their body is producing. This creates a state called hypocapnia, where CO2 levels drop below normal. The fascinating paradox here is that while people who hyperventilate often feel they cannot get enough air, they actually have plenty of oxygen. The sensation of air hunger comes not from oxygen deficiency but from the disruption of the CO2 balance that the body depends on for proper function.

Gasps and sighs involve the quick intake of a large air volume, accompanied by breath-holding. They may comprise part of a defensive reaction. When clients expel excessive CO2, this lowers end-tidal CO2 (the percentage of CO2 at the end of exhalation) and causes hypocapnia, low CO2.

Acute overbreathing produces various symptoms.

How Hypocapnia Disrupts Homeostasis

Hypocapnia disrupts homeostasis by disturbing the body's acid-base (pH) and electrolyte balance, blood flow, and oxygen delivery. Hypocapnia may force the kidneys to expel bicarbonates to restore pH balance (Khazan, 2021).

Electrolytes are substances like acids or salts that can dissociate into free ions when dissolved (for example, NaCl becomes Na+ + Cl-). Hypocapnia deprives cells (such as neurons, cardiac muscle, and skeletal muscle) of the ions (Ca+2 and Na+) required for typical membrane potentials and communication with other cells.

The Effects of Ca+2 Movement

Hypocapnia can move Ca+2 from the interstitial fluid into muscle cells with disastrous results. In skeletal muscle, calcium entry can cause spasms, fatigue, and weakness. In blood vessel smooth muscle, it can produce vasoconstriction. In the bronchioles of the lungs, it can trigger bronchoconstriction. Finally, in the GI tract smooth muscle, it can result in nausea and change motility.

The Effects of Na+ Movement

Na+ ion movement into neurons from extracellular fluid increases excitability, metabolism, and demand for oxygen while reducing oxygen availability for other organs. The brain can experience ischemia and excitotoxicity. Vasoconstriction due to Na+ ion entry and less nitric oxide release greatly diminishes glucose delivery to the tissues, especially to the outermost layers of the cortex (Gevirtz et al., 2016).

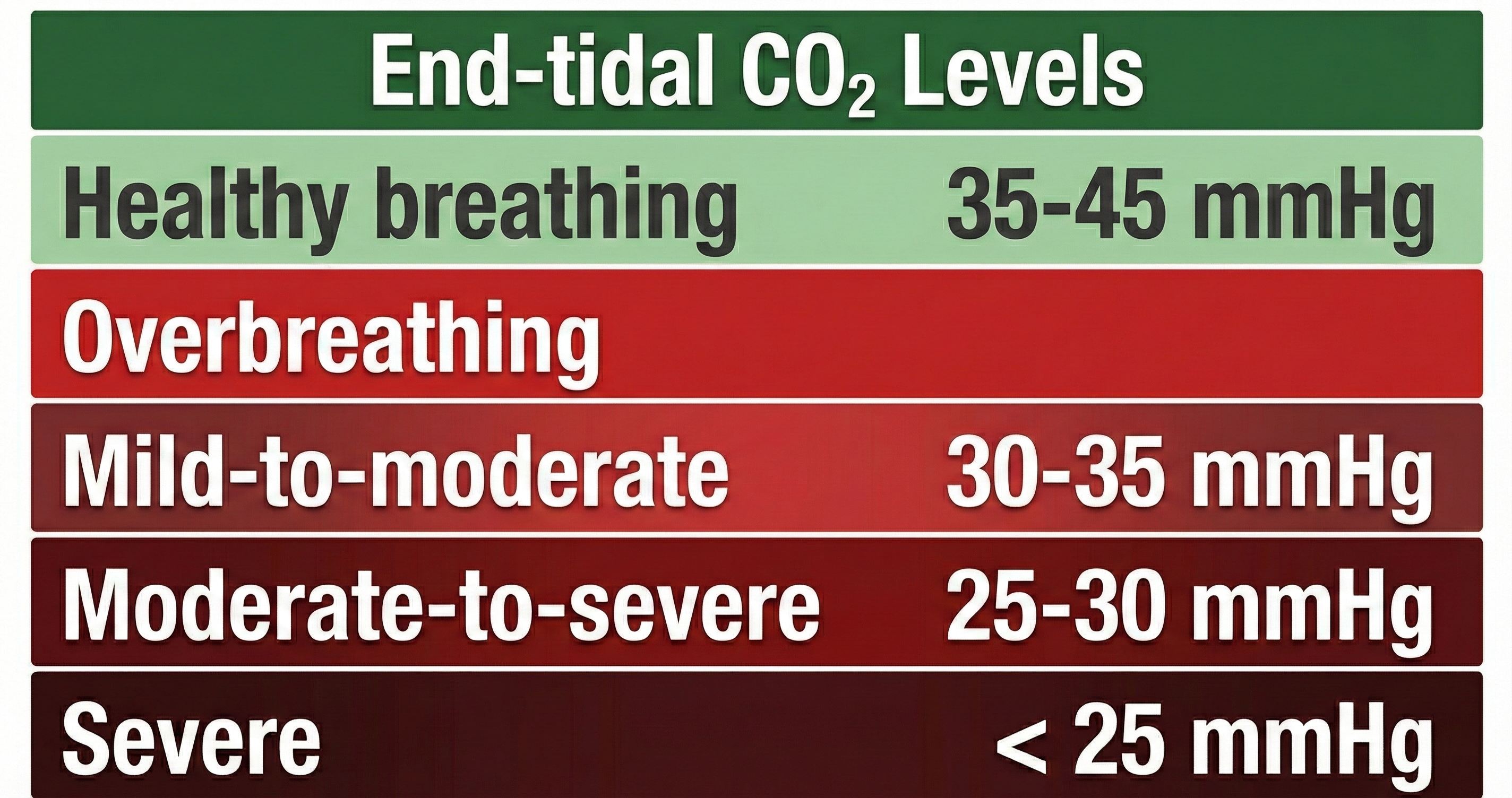

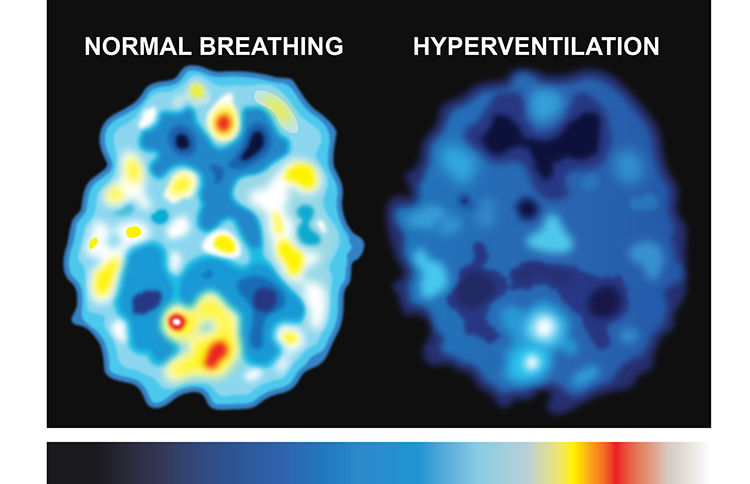

Healthy end-tidal CO2 values range from 35-45 mmHg. Moderate overbreathing can reduce oxygen delivery to the brain by 30%-40%, and severe overbreathing can reduce it by 60%.

Overbreathing can produce acute and chronic vasoconstriction effects and reduced delivery of oxygen and glucose to body tissues, especially the brain (Khazan, 2013).

The SPECT scan created by Dr. Scott Woods below shows the effect of overbreathing on brain metabolism. Darker colors represent reduced metabolism and compromised cortical functioning.

Clinicians use the Nijmegen Questionnaire to screen for hyperventilation syndrome (HVS). For the general population, scores of 20 or higher have been suggested as optimal for predicting HVS, with a sensitivity of 0.91 and specificity of 0.92 (Looha et al., 2020). In asthma patients, a cutoff score of greater than 17 has been used to discriminate the presence of HVS, showing a sensitivity of 92.73% and specificity of 91.59% (Grammatopoulou et al., 2014). In a study involving dizzy patients, a cutoff score of 26.5 was found to be the most sensitive for diagnosing HVS (Taalot, Moaty, & Elsayed, 2019).

Detecting chronic hyperventilation presents unique challenges for healthcare providers. Unlike many medical conditions with clear visual markers, chronic overbreathing often goes unnoticed. The respiratory rate might appear normal, and the breathing pattern may seem unremarkable to casual observation. Clinicians must look for subtle clues: frequent sighing, upper chest breathing, breath-holding patterns, and a constellation of seemingly unrelated symptoms (Gilbert, 2005). The diversity of symptoms often leads people on long diagnostic journeys before anyone considers their breathing as the root cause.

For precise measurement, clinicians use capnometry to measure end-tidal CO2, the carbon dioxide concentration at the very end of exhalation. This provides real-time feedback about CO2 levels and can reveal patterns invisible to the naked eye. Studies have shown that individuals vary significantly in their response to the same CO2 drop, with some experiencing severe symptoms at levels that barely affect others (Gilbert, 2005). Davies and colleagues (2019) found that changes in perceived control and improvements in respiratory dysregulation for hypocapnic individuals specifically underlie symptom improvement from capnometry-guided respiratory interventions for panic disorder.

The Effects of Chronic Overbreathing

Clients who overbreathe may experience chronic hypocapnia. Since the body cannot function with sustained high pH, the kidneys excrete bicarbonates to return pH to near-normal levels. Bicarbonates are salts of carbonic acid that contain HCO3. Acid buffering can only restore homeostasis in the short run because increased metabolism raises acidity until needed bicarbonates are depleted. Clients experience fatigue, muscle pain, reduced physical endurance, and a sodium deficit when this happens. Acidosis may increase overbreathing in a failed attempt to reduce acidity (Khazan, 2021).

When someone maintains a pattern of slight overbreathing for weeks or months, their body attempts to compensate. The kidneys begin excreting bicarbonate to restore pH balance, creating what Gilbert (2005) calls a compensated state. This compensation comes at a significant cost: the body establishes a new, fragile equilibrium that depends on continued hyperventilation to maintain. These individuals live in a precarious state where any additional stress or change in breathing pattern can trigger severe symptoms. They often report persistent fatigue, muscle pain, difficulty concentrating, and ironically, a constant feeling that they cannot get enough air. Their breath-holding time typically drops to less than 20 seconds, compared to the normal 30 to 60 seconds most people can manage comfortably (Gilbert, 2005).

Why Do Clients Overbreathe?

Clients overbreathe as part of the fight-or-flight response in response to stressors, when they experience difficult emotions, and when they suffer chronic pain. They can learn this dysfunctional breathing pattern through classical and operant conditioning and social learning.

Gilbert (2005) reveals fascinating connections between emotional states and breathing patterns. He introduces the concept of action projection, where the body prepares for anticipated physical actions that never materialize. Imagine preparing to confront someone who upset you: your breathing accelerates as your body readies for action, but modern social constraints mean you likely will not engage in the physical confrontation your primitive systems anticipated. You are left in a state of respiratory alkalosis with nowhere for that preparation to go. This mismatch between physiological readiness and social behavior may explain why anxiety disorders are so common in modern society.

Research has demonstrated that hyperventilation and trauma are bidirectionally connected. Nixon and Bryant (2005) found that when individuals with Acute Stress Disorder deliberately hyperventilated for just three minutes, they experienced increased trauma-related memories and flashbacks. The physiological state created by overbreathing appears to directly trigger the re-experiencing of traumatic events, creating a vicious cycle where anxiety drives hyperventilation, which then intensifies psychological symptoms (Gilbert, 2005).

If clients practice overbreathing long enough, it can become a habit when this lowers the body's setpoint for CO2. Now, when breathing slows, the respiratory centers attempt to restore low CO2 levels by removing it through behaviors like breath-holding, sighing, and yawning (Gevirtz, Schwartz, & Lehrer, 2016). Reduced blood CO2 levels may contribute to asthma, panic, phobia, and pain disorders like chronic low back pain.

How Overbreathing and Hyperventilation Differ Clinically

Whereas overbreathing and hyperventilation produce the same physiological changes, hyperventilation involves distinctive behaviors and subjective sensations.

Hyperventilation syndrome (HVS) involves abnormal CO2 loss from the blood due to excessive breathing rate and depth. Here is a sobering statistic: HVS accounts for about 60% of major city ambulance calls due to frightening symptoms like chest pain, breathlessness, dizziness, and panic.

Clients who present with HVS breathe thoracically, deeply, and rapidly (over 20 bpm) using accessory muscles (the sternum moves forward and upward) and restricting diaphragm movement. Their rapid breathing can lower end-tidal CO2 from 5% to 2.5%, although many patients have normal values during attacks (Kern, 2021).

Like overbreathing, this pattern exceeds the body's need to eliminate CO2, reduces oxygen delivery to body tissues and NO release, and curtails their supply of glucose (Khazan, 2013). Check out the YouTube video Breathing Pattern Disorders Such as Hyperventilation.

The conventional advice to "take a deep breath" when stressed may actually worsen hyperventilation. Gilbert (2005) points out that people often interpret "deep" as meaning large volume, leading them to take massive inhalations that further deplete CO2. This well-intentioned but misguided instruction has probably triggered more hyperventilation episodes than it has prevented. Better breathing instructions should focus on pace and location rather than volume. Low and slow breathing, where the emphasis is on diaphragmatic movement and extended exhalation, allows CO2 to rebuild properly. The key is breathing at a rate that matches metabolic needs, typically around 6 to 10 breaths per minute at rest, with exhalation lasting longer than inhalation.

A comprehensive systematic review of 58 breathing intervention studies found that effective breath practices avoided fast-only breath paces and sessions shorter than 5 minutes, while including human-guided training, multiple sessions, and long-term practice (Bentley et al., 2023). These findings provide clinicians with evidence-based guidelines for designing breathing interventions: sessions should last at least 5 minutes, involve slow breathing rates, and include proper instruction rather than simply telling clients to "breathe deeply."

The BioGraph® Infiniti display below shows the shallow, rapid breathing that characterizes hyperventilation.

In contrast to HVS, overbreathing is usually so subtle that the patients are unaware that their sighs and yawns produce hypocapnia.

An important distinction concerns exercise and breathing. Heavy breathing during physical activity is not hyperventilation because increased muscle activity produces more CO2, which matches the increased respiratory rate (Gilbert, 2005). The body maintains its crucial balance even as production and elimination accelerate. This explains why the same breathing rate that would cause symptoms at rest feels perfectly normal during a workout. Understanding this distinction helps clinicians explain to anxious clients why their symptoms appear at rest but not during exercise.

Apnea: When Breathing Stops

Apnea involves the suspension of breathing. While commonly associated with sleep, breath-holding while awake may occur during stressful situations as part of a defensive response. A client may also hold breaths during ordinary activities like opening a jar, speaking, or writing a check. Episodes of apnea decrease ventilation and may increase blood pressure.

Do not confuse apnea with post-expiratory pauses.

In the BioGraph® Infiniti display below, the blue abdominal strain gauge trace briefly flattens when the patient suspends breathing after the second breath.

Comprehension Questions: Disordered Breathing

- What are the key differences between thoracic breathing and healthy diaphragmatic breathing?

- Explain how chronic overbreathing can reset the body's CO2 setpoint and why this makes treatment challenging.

- Why does hyperventilation syndrome account for such a high percentage of ambulance calls in major cities?

- How would you help a client differentiate between healthy post-expiratory pauses and problematic apnea?

- Using what you know about the Bohr effect, explain why overbreathing paradoxically reduces oxygen delivery despite increased breathing.

Cutting Edge Topics in Respiration

Breathing and Pupil Dynamics: A Window into Brain-Body Communication

Research led by Martin Schaefer at the Karolinska Institute has revealed a fascinating connection between breathing and pupil size. In a study of 100 participants, Schaefer and colleagues (2023) found that pupils are smallest at the start of inhalation, expand to their largest during mid-exhalation, and then rapidly contract as exhalation ends. This discovery suggests neural pathways connecting brainstem respiratory centers with pupil control mechanisms. The practical implications are intriguing: smaller pupils sharpen central vision while larger pupils enhance peripheral awareness. Researchers are now exploring whether intentional breathing control could help athletes and others who depend on visual precision. While the evolutionary purpose remains unclear, this finding adds to our understanding of how breathing influences far more than just gas exchange.

Nasal Nitric Oxide and Cardiovascular Health

Emerging research continues to highlight the cardiovascular benefits of nasal breathing. Watso and colleagues (2023) demonstrated that acute nasal breathing lowers blood pressure and increases parasympathetic contributions to heart rate variability in young adults. This effect appears mediated by nitric oxide released from the paranasal sinuses during nasal inhalation. Unlike mouth breathing, nasal breathing delivers this vasodilatory gas directly to the lungs, where it enhances oxygen uptake and improves overall cardiovascular function. These findings have clinical implications for hypertension management and suggest that simply teaching clients to breathe through their nose could provide measurable cardiovascular benefits.

Nasal Breathing, Fear, and Memory

Research by Zelano and colleagues (2016) revealed that nasal inhalation, but not mouth breathing or nasal exhalation, activates the amygdala, hippocampus, and olfactory cortex. This neural activation appears to accelerate threat detection and influence memory consolidation. During panic attacks, when breathing becomes faster and more time is spent inhaling, this mechanism may amplify fear responses. Understanding this connection opens new possibilities for breathing-based interventions in anxiety disorders and PTSD. Clinicians can use this knowledge to explain to anxious clients why slowing their breath and emphasizing exhalation may help reduce fear responses.

The Airway-Dental Connection

Chronic mouth breathing has consequences that extend far beyond respiratory health. Lin and colleagues (2022) documented how mouth breathing alters tongue and jaw posture in ways that can lead to dental malocclusions and facial deformities in children. Tamkin (2020) showed that mouth breathing reduces saliva flow, increasing risks for dental decay and gum disease. These findings underscore the importance of early identification and correction of mouth breathing habits, particularly in pediatric populations. Biofeedback practitioners working with children should consider incorporating breathing pattern assessment as a standard part of their evaluations.

Glossary

accessory muscles: the sternocleidomastoid, pectoralis minor, scalene, and trapezius muscles, which are used during forceful breathing, as well as during clavicular and thoracic breathing.

acidosis: a decrease in the normal alkalinity of the blood or tissues, leading to a lower pH level. It can be caused by an increase in acid production, a decrease in acid excretion, or a loss of bicarbonate, which is a base that helps neutralize acids in the body.

action projection: the body's preparation for anticipated physical action that does not materialize, leaving physiological arousal without release, which can contribute to chronic respiratory alkalosis.

apnea: breath suspension.

bicarbonates: salts of carbonic acid that contain HCO3.

Bohr effect: the influence of carbon dioxide on hemoglobin release of nitric oxide and oxygen.

breath-holding time: the duration a person can comfortably hold their breath after a normal exhalation, typically 30 to 60 seconds in healthy individuals but often reduced to less than 20 seconds in those with chronic hyperventilation.

Breathing IQ: an anthropometric index that measures the efficiency of diaphragmatic breathing by assessing abdominothoracic expansion and retraction during inhalation and exhalation.

capnometry: the measurement of carbon dioxide concentration in exhaled breath, particularly end-tidal CO2, providing real-time feedback about respiratory function.

capnometry-guided respiratory intervention: a biofeedback treatment approach that provides real-time feedback on end-tidal CO2 and respiration rate to help individuals correct dysfunctional breathing patterns.

carbon dioxide: a gas produced by cellular metabolism, crucial for regulating breathing, maintaining blood pH balance, and facilitating oxygen delivery to tissues.

carbonic acid: a weak acid formed when CO2 dissolves in blood, crucial for maintaining pH balance.

cerebral cortex: the 2-4 millimeter-thick outer layers covering the cerebral hemispheres containing circuitry essential to complex brain functions like cognition and consciousness.

clavicular breathing: a breathing pattern that primarily relies on the external intercostals and the accessory muscles to inflate the lungs, resulting in a more rapid respiration rate, excessive energy consumption, and incomplete ventilation of the lungs.

compensated state: a fragile physiological equilibrium that develops in chronic hyperventilators when the kidneys excrete bicarbonate to restore pH balance, making the body dependent on continued hyperventilation to maintain normal pH.

diaphragm: the dome-shaped muscle whose contraction enlarges the vertical diameter of the chest cavity and accounts for about 75% of air movement into the lungs during relaxed breathing.

dorsal respiratory group (DRG): neuron clusters in the brainstem's medulla that collect information from peripheral stretch and chemoreceptors and distribute this information to the VRG to modify its breathing rhythms.

end-tidal CO2: the percentage of CO2 in exhaled air at the end of exhalation.

external intercostals: the muscles of inhalation that pull the ribs upward and enlarge the thoracic cavity. The external intercostals account for about 25% of air movement into the lungs during relaxed breathing.

heart rate variability (HRV): beat-to-beat changes in heart rate, including changes in the R-R intervals between consecutive heartbeats.

hemoglobin: a red blood cell protein that carries oxygen throughout the circulatory system.

hypercapnia: a condition characterized by an abnormally high level of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the blood.

hyperventilation (HV): a syndrome in which deep and rapid breathing cause breathlessness and reduce end-tidal CO2 below 5%, exceeding the body's need to eliminate CO2.

hypocapnia: decreased CO2 in arterial blood.

inspiratory muscles: the diaphragm and external intercostals.

low and slow breathing: a breathing technique emphasizing diaphragmatic movement and extended exhalation at a rate of 6 to 10 breaths per minute, which allows CO2 to rebuild properly and avoids the hyperventilation often caused by instructions to "take a deep breath."

metabolic acidosis: a disturbance characterized by a decrease in the body's bicarbonate levels or an increase in the production of acids, leading to a reduction in the arterial blood pH below 7.35. This condition can result from increased acid production (such as ketoacidosis or lactic acidosis), reduced kidney acid secretion, or significant bicarbonate losses.

nitric oxide (NO): a gaseous neurotransmitter that promotes vasodilation and long-term potentiation.

overbreathing: a mismatch between breathing rate and depth due to excessive breathing effort and subtle breathing behaviors like sighs and yawns can reduce arterial CO2.

oxygen saturation: a measure of the percentage of hemoglobin binding sites in the bloodstream occupied by oxygen.

pH: the power of hydrogen; the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution determined by the concentration of hydrogen ions.

pons: a brainstem structure above the medulla containing breathing centers that adjust VRG breathing rhythms based on descending input from brain structures and peripheral sensory input.

pontine respiratory group (PRG): neurons located in the pons that communicate with the dorsal respiratory group (DRG) in the medulla to modify the basic breathing rhythm.

psychosomatic loop: a bidirectional relationship between breathing and emotion where anxiety drives hyperventilation, while hyperventilation intensifies psychological symptoms, creating a self-perpetuating cycle.

rectus abdominis: a muscle of forceful expiration that depresses the inferior ribs and compresses the abdominal viscera to push the diaphragm upward.

resonance breathing: slow-paced breathing at approximately 6 breaths per minute, which optimizes parasympathetic nervous system activity and heart rate variability by synchronizing breathing with cardiovascular oscillations.

respiratory acidosis: a state in which decreased ventilation (hypoventilation) leads to an increase in carbon dioxide concentration and a decrease in blood pH. This condition is often due to impaired lung function, chest injuries, or diseases that affect the respiratory muscles or control of breathing.

respiratory alkalosis: a condition characterized by elevated blood pH due to excessive carbon dioxide exhalation, typically caused by hyperventilation.

respiratory amplitude: the excursion of an abdominal strain gauge.

respiratory cycle: an inspiratory phase, inspiratory pause, expiratory phase, and expiratory pause.

respiratory membrane: the site of respiratory gas exchange that is comprised by alveolar and capillary walls.

reverse breathing: a dysfunctional breathing pattern in which the abdomen expands during exhalation and contracts during inhalation, often resulting in incomplete ventilation of the lungs.

thoracic breathing: a dysfunctional breathing pattern that relies primarily on the external intercostals to inflate the lungs, resulting in a more rapid respiration rate, excessive energy consumption, and insufficient lung ventilation.

tidal volume: the amount of air inhaled or exhaled during a normal breath.

ventral respiratory group (VRG): neurons located in the medulla that initiate inhalation and exhalation.

Test Yourself

Click on the ClassMarker logo to take 10-question tests over this unit without an exam password.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Visit the BioSource Software Website

BioSource Software offers Human Physiology, which satisfies BCIA's Human Anatomy and Physiology requirement, and Biofeedback100, which provides extensive multiple-choice testing over BCIA's Biofeedback Blueprint.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, think about your own breathing pattern and the patterns you most often see in your clients.

References

Andreassi, J. L. (2007). Psychophysiology: Human behavior and physiological response (5th ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, Inc.

Abdullahi, A., Wong, T. W. L., & Ng, S. S. M. (2024). Efficacy of diaphragmatic breathing exercise on respiratory, cognitive, and motor function outcomes in patients with stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neurology, 14, 1233408. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1233408

Bentley, T. G. K., D'Andrea-Penna, G., Rakic, M., Arce, N., LaFaille, M., Berman, R., Cooley, K., & Sprimont, P. (2023). Breathing practices for stress and anxiety reduction: Conceptual framework of implementation guidelines based on a systematic review of the published literature. Brain Sciences, 13(12), 1612. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13121612

Bjermer, L. (1999). The nose as an air conditioner for the lower airways. Allergy, 54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.1999.tb04403.x

Davies, C. D., McGrath, P. B., Hale, L. R., Weiner, D. N., & Gueorguieva, R. (2019). Mediators of change in capnometry guided respiratory intervention for panic disorder. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 44, 97-102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-018-9424-2

Fox, S. I., & Rompolski, K. (2022). Human physiology (16th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Fried, R. (1987). The hyperventilation syndrome: Research and clinical treatment. John Hopkins University Press.

Fried, R., & Grimaldi, J. (1993). The psychology and physiology of breathing. Springer.

Gevirtz, R. N., Schwartz, M. S., & Lehrer, P. M. (2016). Cardiorespiratory measurement and assessment in applied psychophysiology. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.), Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Gilbert, C. (2005). Better chemistry through breathing: The story of carbon dioxide and how it can go wrong. Biofeedback, 33(3), 100-104.

Grammatopoulou, E., Skordilis, E., Georgoudis, G., Haniotou, A., Evangelodimou, A., Fildissis, G., Katsoulas, T., & Kalagiakos, P. (2014). Hyperventilation in asthma: A validation study of the Nijmegen Questionnaire-NQ. Journal of Asthma, 51, 839-846. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2014.922190

Guyenet, P., & Bayliss, D. (2015). Neural control of breathing and CO2 homeostasis. Neuron, 87, 946-961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.001

Holloway, E. A. (1994). The role of the physiotherapist in the treatment of hyperventilation. In B. H. Timmons & R. Ley (Eds.), Behavioral and psychological approaches to breathing disorders. Plenum Press.

Hopkins, E., Sanvictores, T., & Sharma, S. (2022). Physiology, acid base balance. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID: 29939584

Hsia, C. (2023). Tissue perfusion and diffusion and cellular respiration: Transport and utilization of oxygen. Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 44, 594-611. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1770061

Jung, W., Jang, K. I., & Lee, S. H. (2024). Heart rate variability biofeedback and its effect on emotional and cognitive systems: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 156, 105477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105477

Kern, B. (2021). Hyperventilation syndrome treatment & management. eMedicine. Retrieved from Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/807277-treatment

Khazan, I. (2019a). A guide to normal values for biofeedback. In D. Moss & F. Shaffer (Eds.), Physiological recording technology and applications in biofeedback and neurofeedback (pp. 2-6). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Khazan, I. (2019b). Biofeedback and mindfulness in everyday life: Practical solutions for improving your health and performance. W. W. Norton & Company.

Khazan, I. (2021). Respiratory anatomy and physiology. BCIA HRV Biofeedback Certificate of Completion Didactic workshop.

Khazan, I. Z. (2013). The clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Kimberly, B., Nejadnik, B., Giraud, G., Holden, W., & Holden, W. (1996). Nasal contribution to exhaled nitric oxide at rest and during breathholding in humans. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 153(2), 829-836. https://doi.org/10.1164/AJRCCM.153.2.8564139

LaComb, C., Tandy, R., Lee, S., Young, J., & Navalta, J. (2017). Oral versus nasal breathing during moderate to high intensity submaximal aerobic exercise. International Journal of Kinesiology and Sports Sciences, 5, 8-16. https://doi.org/10.7575//AIAC.IJKSS.V.5N.1P.8

Laborde, S., Allen, M. S., Borges, U., Dosseville, F., Hosang, T. J., Iskra, M., Mosley, E., Salvotti, C., Spolverato, L., Zammit, N., & Javelle, F. (2022). Effects of voluntary slow breathing on heart rate and heart rate variability: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 138, 104711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104711

Lin, L., Zhao, T., Qin, D., Hua, F., & He, H. (2022). The impact of mouth breathing on dentofacial development: A concise review. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 929165. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.929165

Long, K. (2016, February 9). The science behind the sigh. The Wall Street Journal, D3.

Looha, M., Masaebi, F., Abedi, M., Mohseni, N., & Fakharian, A. (2020). The optimal cut-off score of the Nijmegen Questionnaire for diagnosing hyperventilation syndrome using a Bayesian model in the absence of a gold standard. Galen Medical Journal, 9, e1738-e1738. https://doi.org/10.31661/gmj.v9i0.1738

Lorig, T. S. (2007). The respiratory system. In J. T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, & G. G. Berntson (Eds.), Handbook of psychophysiology (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Marcella, M., Negro, C., Ronchese, F., Rui, F., Bovenzi, M., & Filon, F. L. (2024). Heart rate variability modulation through slow-paced breathing in health care workers with long COVID: A case-control study. The American Journal of Medicine, 137(9), 876-882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.05.019

Marieb, E. N., & Hoehn, K. (2019). Human anatomy and physiology (11th ed.). Pearson Benjamin Cummings.

Martel, J., Ko, Y., Young, J., & Ojcius, D. (2020). Could nasal nitric oxide help to mitigate the severity of COVID-19? Microbes and Infection, 22, 168-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2020.05.002

Milic-Emili, J., & Tyler, J. (1963). Relation between work output of respiratory muscles and end-tidal CO2 tension. Journal of Applied Physiology, 18(3), 497-504. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPL.1963.18.3.497

Naclerio, R., Pinto, J., Assanasen, P., & Baroody, F. (2007). Observations on the ability of the nose to warm and humidify inspired air. Rhinology, 45(2), 102-111. PMID: 17708456

Nixon, R. D. V., & Bryant, R. A. (2005). Induced arousal and reexperiencing in acute stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 19(6), 587-594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.05.001

Peper, E., Harvey, R., Lin, I., Tylova, H., & Moss, D. (2007). Is there more to blood volume pulse than heart rate variability, respiratory sinus arrhythmia, and cardio-respiratory synchrony? Biofeedback, 35(2), 54-61.

Peper, E., & Tibbetts, V. (1992). Fifteen-month follow-up with asthmatics utilizing EMG/incentive inspirometer feedback. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 17(2), 143-151.

Prisca, E., Pietro, C., Anja, K., Laura, S., Sarina, H., Dominic, K., Sabina, G., & Matthias, W. (2024). Improved exercise ventilatory efficiency with nasal compared to oral breathing in cardiac patients. Frontiers in Physiology, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1380562

Riggs, A. (1988). The Bohr effect. Annual Review of Physiology, 50, 181-204. https://doi.org/10.1146/ANNUREV.PH.50.030188.001145

Saatchi, R., Holloway, A., Travis, J., Elphick, H., Daw, W., Kingshott, R. N., Hughes, B., Burke, D., Jones, A., & Evans, R. L. (2025). Design, development, and evaluation of a contactless respiration rate measurement device utilizing a self-heating thermistor. Technologies, 13(6), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13060237

Schaefer, M., Edwards, S., Norden, F., Lundstrom, J. N., & Arshamian, A. (2023). Inconclusive evidence that breathing shapes pupil dynamics in humans: A systematic review. Pflugers Archiv: European Journal of Physiology, 475(1), 119-137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-022-02729-0

Stern, R. M., Ray, W. J., & Quigley, K. S. (2001). Psychophysiological recording (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Swenson, E. (2017). Carbon dioxide elimination by cardiomyocytes: A tale of high carbonic anhydrase activity and membrane permeability. Acta Physiologica, 221. https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.12922

Talaat, H., Moaty, A., & Elsayed, M. (2019). Arabization of Nijmegen questionnaire and study of the prevalence of hyperventilation in dizzy patients. Hearing, Balance and Communication, 17, 182-188. https://doi.org/10.1080/21695717.2019.1590989

Tamkin, J. (2020). Impact of airway dysfunction on dental health. Bioinformation, 16(1), 26-29. https://doi.org/10.6026/97320630016026

Tanaka, Y., Morikawa, T., & Honda, Y. (1988). An assessment of nasal functions in control of breathing. Journal of Applied Physiology, 65(4), 1520-1524. https://doi.org/10.1152/JAPPL.1988.65.4.1520

Tanaka, T., Sato, H., & Kasai, K. (2020). Lethal physiological effects of carbon dioxide exposure at high concentration in rats. Legal Medicine, 47, 101746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2020.101746

Tobin, M. J., Mador, M. J., Guenther, S. M., Lodato, R. F., & Sackner, M. A. (1985). Variability of resting respiratory drive and timing in healthy subjects. Journal of Applied Physiology, 65(1), 308-317. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1988.65.1.309

Tolin, D. F., McGrath, P. B., Hale, L. R., Weiner, D. N., & Gueorguieva, R. (2017). A multisite benchmarking trial of capnometry guided respiratory intervention for panic disorder in naturalistic treatment settings. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 42(1), 51-58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-017-9354-4

Tortora, G. J., & Derrickson, B. H. (2021). Principles of anatomy and physiology (16th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Vranich, B., Lee, C., Zapanta, P., Shoen, J., Houghton, A., Ruelas, S., Wahlfeldt, R., Kerr, J., Pripotnev, S., Goorahoo, V., Baptiste, L., & Elliot, J. (2025). The Breathing IQ: An anthropometric index of diaphragmatic breathing efficiency. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 6, 1507001. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2024.1507001

Watso, J., Cuba, J., Boutwell, S., Moss, J., Bowerfind, A., Fernandez, I., Cassette, J., May, A., & Kirk, K. (2023). Abstract P342: Acute nasal breathing lowers blood pressure and increases parasympathetic contributions to heart rate variability in young adults. Hypertension. https://doi.org/10.1161/hyp.80.suppl_1.p342

Zelano, C., Jiang, H., Zhou, G., Arora, N., Schuele, S., Rosenow, J., & Gottfried, J. A. (2016). Nasal respiration entrains human limbic oscillations and modulates cognitive function. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(49), 12448-12467. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2586-16.2016