Autonomic Applications

What You Will Learn

Have you ever felt your stomach churn before an exam, or noticed your hands go cold when you're nervous? These everyday experiences reveal something profound: your mind and body are deeply connected through the autonomic nervous system—the "automatic pilot" that controls functions you don't normally think about, like digestion, blood flow, and sweating. This chapter explores how biofeedback can harness that mind-body connection to treat conditions that might seem impossible to control consciously.

You'll discover how clinicians combine different biofeedback modalities—EMG (muscle tension), heart rate variability, skin electrical activity, and temperature—with relaxation training in an approach called biofeedback-assisted relaxation training (BART). More importantly, you'll learn which conditions respond best to these interventions, what the research actually shows, and how to apply this knowledge in clinical practice.

The autonomic applications of biofeedback are remarkably diverse—and that's actually the point. Because the autonomic nervous system influences so many body functions, learning to regulate it can help with surprisingly different conditions: joint disorders, preeclampsia (a dangerous pregnancy complication), functional gastrointestinal disorders like irritable bowel syndrome, diabetes complications, excessive sweating, immune function, and even motion sickness. The common thread? All involve autonomic dysregulation that biofeedback can help normalize.

Clinicians have successfully treated these conditions by combining EMG, heart rate variability, skin electrical activity, and temperature biofeedback with relaxation training. This approach is termed biofeedback-assisted relaxation training (BART).

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses the Pathophysiology, biofeedback modalities, and treatment protocols for specific ANS biofeedback applications (IV-D).

This unit covers Joint Disorders, Preeclampsia, Functional Abdominal Pain, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Glycemic Control, Intermittent Claudication, Foot Ulcers, Hyperhidrosis, Immune Function, and Motion Sickness.

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter Lecture

Evidence-Based Practice

The efficacy ratings presented throughout this chapter are based on Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.), published by the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

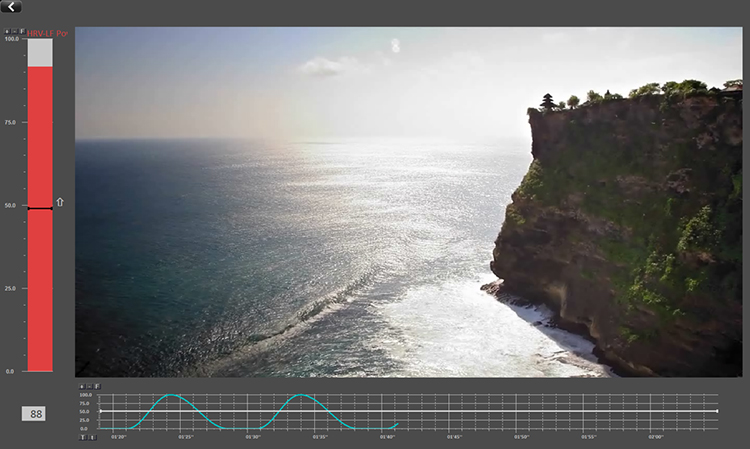

Below is a BioTrace+/NeXus-10 screen that displays several modalities that could be used to treat autonomic disorders like arthritis.

Joint Disorders: When Inflammation Attacks

If you've ever watched a grandparent struggle to open a jar or seen someone wince when climbing stairs, you've witnessed the impact of joint disorders. These conditions affect hundreds of millions of people worldwide, and while medication helps many, biofeedback offers a complementary approach that puts some control back in the patient's hands.

The American College of Rheumatology divides joint disorders into two main categories: noninflammatory (where the joint wears down over time) and inflammatory (where the immune system attacks the joint). Understanding this distinction matters for biofeedback practitioners because the treatment rationale differs for each type.

Let's start with osteoarthritis (OA)—the "wear and tear" arthritis that most people associate with aging. You might think of OA as simply cartilage breaking down, like a car's brake pads wearing thin. But researchers now recognize it's more complex: OA is a whole-joint disease that affects not just the cartilage, but also the bone underneath (subchondral bone), the joint lining (synovium), and surrounding tissues (Tang et al., 2025).

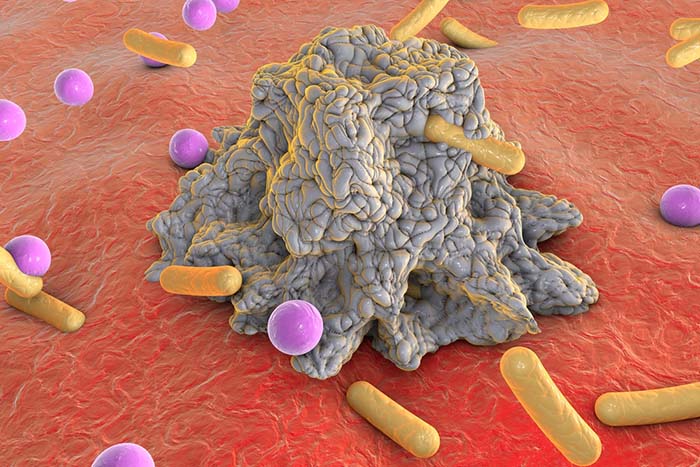

What drives this damage? The body releases inflammatory molecules called cytokines—specifically interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)—which trigger enzymes called matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) to break down the joint's structural framework (Lou & Bu, 2025). This inflammatory cascade is important to understand because, as we'll see, biofeedback may help interrupt it.

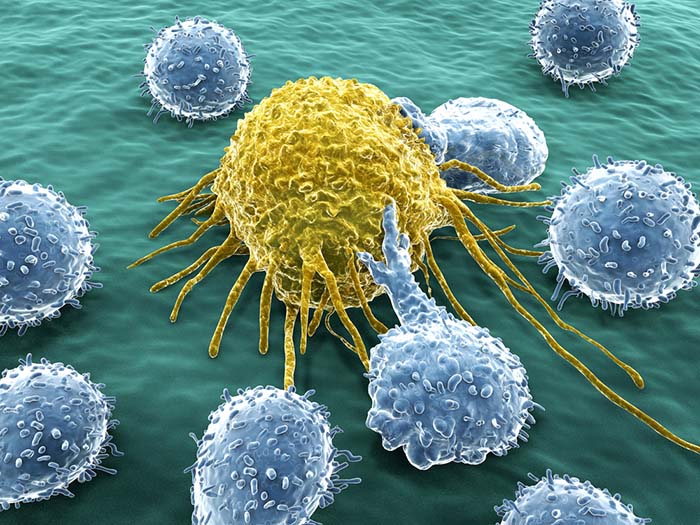

Inflammatory joint disease, called arthritis, takes a more aggressive approach: the immune system actively attacks the joint lining and cartilage. The result? Painful joint swelling and stiffness, thickening of the synovial membrane (the tissue that lines the joint), and signs of inflammation throughout the body.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most well-known inflammatory arthritis—and it's an autoimmune disorder, meaning the body's defense system mistakenly attacks its own tissues. Recent research has identified the specific immune cells responsible: pro-inflammatory macrophages (immune cells that normally eat bacteria) and fibroblast-like synoviocytes (cells in the joint lining) that together drive a destructive inflammatory cascade (D'Orazio et al., 2024). Both genetic factors—particularly a gene variant called HLA-DRB1—and metabolic problems contribute to RA (Gao et al., 2024).

The key insight for biofeedback practitioners? RA involves chronic inflammation that the autonomic nervous system can influence.

Who Gets Joint Disorders?

The numbers are staggering. The Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 reported approximately 607 million people worldwide have osteoarthritis—making it one of the most common chronic conditions on the planet (Li et al., 2024). In the United States alone, OA affects 32.5 million adults (CDC, 2023).

Here's an interesting pattern: before age 50, men and women develop OA at similar rates. After 50? Women account for about 60% of all cases—a disparity researchers are still working to fully explain. Obesity remains a major risk factor; excess body weight contributes to 20% of OA-related disability, likely through both mechanical stress on joints and metabolic effects (Long et al., 2022).

Rheumatoid arthritis is less common but still affects approximately 17.6 million people worldwide, with prevalence increasing 14% since 1990 (GBD 2021 Rheumatoid Arthritis Collaborators, 2023). Women are about 2.5 times more likely than men to develop RA—a pattern seen in many autoimmune diseases. While RA can strike at any age, it typically appears between ages 25 and 50. Researchers project that 31.7 million people will have RA by 2050 (GBD 2021 Rheumatoid Arthritis Collaborators, 2023), making effective treatments increasingly urgent.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)—the preferred term for chronic childhood arthritis appearing before age 16 that persists longer than 6 weeks—reminds us that joint disease isn't just an "old person's problem." JIA is the most common chronic rheumatologic condition in children, affecting an estimated 294,000 children in the United States (Huang et al., 2024). The term "idiopathic" means we don't know the cause—a humbling reminder of how much we still have to learn about immune system dysfunction.

Temperature and EMG Biofeedback Show Promise for Arthritis

Here's where things get interesting for biofeedback practitioners. Clinicians have used temperature and SEMG (surface electromyography) biofeedback to successfully treat arthritis—but how could measuring skin temperature or muscle tension possibly help a joint disorder?

The rationale is elegantly simple: temperature biofeedback teaches patients to increase blood flow to their extremities. More blood flow means faster clearance of those inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α), prostaglandins, and enzymes we discussed earlier. Think of it like flushing out a clogged drain—the inflammatory chemicals causing pain get washed away more efficiently.

But there's an even more exciting mechanism. Heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback shows particular promise because it activates something called the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Here's how it works: when you increase vagal tone (parasympathetic activity), the vagus nerve sends signals that directly inhibit immune cells from releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (Gitler et al., 2025).

In other words, relaxation isn't just "in your head"—it physically turns down inflammation at the cellular level. This discovery helps explain why stress tends to worsen autoimmune conditions and why relaxation-based interventions can help.

What does the research show? Flor, Haag, Turk, and Koehler (1983) compared SEMG biofeedback, a credible placebo treatment, and conventional medical treatment in 24 patients with chronic rheumatic back pain. After 4 weeks of inpatient treatment and a 4-month follow-up, only the SEMG biofeedback group showed significant muscle tension reduction and improved pain duration, intensity, and quality. The placebo and medical treatment groups didn't show these improvements.

For children, Lavigne and colleagues (1992) tested a six-session protocol combining relaxation training, SEMG biofeedback, and thermal biofeedback for four children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. The results were modest but meaningful: children and parents reported reduced pain intensity and fewer pain behaviors at treatment end and 6-month follow-up. Interestingly, physical therapists didn't rate pain as improved during evaluations—a reminder that different measures capture different aspects of the pain experience.

Consider Maria, a 45-year-old office manager who developed rheumatoid arthritis three years ago. Despite medication, she experiences chronic joint pain that interferes with her typing and mouse use. After learning temperature biofeedback combined with relaxation training, Maria discovered she could increase blood flow to her hands and reduce her perception of pain intensity. While biofeedback did not replace her medication, it gave her an active coping tool that improved her sense of control over her condition.

Biofeedback for joint disorders combines temperature and SEMG modalities with relaxation training. Temperature biofeedback may work by increasing blood flow to affected joints, which helps clear inflammatory substances. Research shows modest but meaningful improvements in pain ratings, though more controlled studies are needed.

Comprehension Questions

- What is the key difference between osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis?

- How might temperature biofeedback reduce arthritis pain?

- Which demographic groups are at highest risk for osteoarthritis?

Preeclampsia: A Serious Pregnancy Complication

Imagine being pregnant and suddenly developing dangerously high blood pressure—a condition that threatens both your life and your baby's. That's preeclampsia, also called pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH). It's defined by elevated blood pressure and protein in the urine (indicating kidney stress) appearing after the 20th week of pregnancy. While it might sound like "just high blood pressure," preeclampsia can rapidly become life-threatening.

Scientists now understand preeclampsia through a two-stage model. In Stage 1, during the first trimester, the placenta doesn't attach properly. Specifically, the spiral arteries that should remodel to deliver blood to the placenta don't develop correctly, leading to reduced blood flow.

In Stage 2, the poorly functioning placenta releases an imbalance of proteins into the mother's bloodstream: too many anti-angiogenic factors (like sFlt-1 and soluble endoglin, which block blood vessel formation) and too few pro-angiogenic factors (like VEGF and PlGF, which promote blood vessel growth). This imbalance damages blood vessel linings throughout the body, causing widespread constriction and immune system dysfunction (Liu et al., 2024; Osman et al., 2024). The result? Hypertension, organ damage, and in severe cases, seizures or death.

The Scope of the Problem

Preeclampsia affects 2-8% of pregnancies worldwide—which translates to millions of women each year—and remains a leading cause of maternal and fetal death (Johnson et al., 2022). The global toll is sobering: over 70,000 maternal deaths and 500,000 fetal deaths annually. These aren't just statistics; they represent families devastated by a condition we still can't fully prevent.

The burden of preeclampsia falls unequally across racial groups, and this disparity demands attention. In the United States, Black women experience significantly higher rates of preeclampsia than White women—one study found 12.4% prevalence in Black women compared to 7.1% in White women (Sharma et al., 2021).

But here's the crucial finding: these disparities aren't simply biological. Research shows that Black women born in the U.S. face higher preeclampsia risk than Black immigrant women, strongly suggesting that environmental and social factors—chronic stress, healthcare access, systemic racism—play significant roles (Johnson et al., 2022). American Indian and Alaskan Native women also experience disproportionately elevated rates (Johnson et al., 2022).

Understanding these disparities matters for biofeedback practitioners because stress-reduction interventions may be particularly valuable for populations facing chronic stressors.

Biofeedback Research Shows Strong Results

This is where biofeedback shines. Three randomized controlled trials (El Kosery et al., 2005; Little et al., 1984; Somers et al., 1989) and a multi-group study with a historical control (Cullins et al., 2013) tested whether biofeedback-assisted relaxation could help manage preeclampsia. The modalities used included electrodermal biofeedback (measuring galvanic skin response and skin conductance), heart rate variability biofeedback, and temperature biofeedback.

Why these modalities? Each provides a window into autonomic nervous system activity and can be used to train patients toward parasympathetic dominance—a calmer, less reactive physiological state.

Clinical Efficacy

The results are impressive. Based on three RCTs, Fred Shaffer rated electrodermal and temperature BART as efficacious and specific for preeclampsia—the highest rating in the evidence-based practice hierarchy. What does "efficacious and specific" mean? It indicates that biofeedback showed benefits superior to a credible placebo treatment or alternative therapy, ruling out the possibility that improvement was simply due to attention or expectation.

Participants showed improvements across multiple measures: less frequent hospitalizations, shorter hospital stays, lower diastolic blood pressure (DBP), lower mean arterial pressure (MAP), lower systolic blood pressure (SBP), reduced need for antihypertensive medication (methyldopa), and less protein in the urine (proteinuria). These aren't just numbers—they represent safer pregnancies and better outcomes for mothers and babies.

Sarah, a 32-year-old pregnant woman, developed elevated blood pressure at 24 weeks. Her obstetrician referred her for biofeedback-assisted relaxation training as an adjunct to medical monitoring. Over six sessions, Sarah learned to use temperature biofeedback and diaphragmatic breathing to activate her parasympathetic nervous system. Her blood pressure stabilized, and she was able to reduce her antihypertensive medication dosage while maintaining close medical supervision throughout the remainder of her pregnancy.

Biofeedback-assisted relaxation training for preeclampsia has achieved the highest efficacy rating based on multiple RCTs. Effective modalities include electrodermal and temperature biofeedback. Participants show improvements across multiple measures including blood pressure, hospitalization rates, medication needs, and proteinuria levels.

Comprehension Questions

- At what point in pregnancy does preeclampsia typically develop?

- What efficacy rating did biofeedback for preeclampsia receive, and why?

- Which populations face disproportionately higher risks from preeclampsia?

Functional Abdominal Pain: When the Gut-Brain Connection Goes Awry

You've probably heard the phrase "gut feeling"—and there's real neuroscience behind it. Your gut contains over 100 million neurons (more than your spinal cord!), and it communicates constantly with your brain through what scientists call the gut-brain axis. When this communication system malfunctions, the result can be chronic pain with no obvious physical cause.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders are diagnosed by their symptoms rather than visible abnormalities. Doctors examine these patients, run tests, perform scans—and find nothing structurally wrong. Yet the pain is very real. These conditions include cyclic vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and functional abdominal pain.

Functional abdominal pain (FAP), also called recurrent abdominal pain (RAP), features episodes of abdominal pain without detectable pathology—no tumors, no obstruction, no inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). "Functional" doesn't mean the pain is imaginary; it means the problem lies in how the nervous system is functioning rather than in visible tissue damage. An estimated 15-20% of school-age children and adolescents experience at least one episode of RAP each year, with girls affected 1.5 times more often than boys (Greenberger, 2013).

For these children, stomach aches mean missed school, social isolation, and frustrated parents wondering why their child keeps complaining about pain that tests can't explain.

Cyclic vomiting syndrome is another distressing functional disorder: severe episodes of nausea and vomiting lasting hours to days, with complete recovery between episodes. Imagine being perfectly fine one day, then suddenly vomiting uncontrollably for 24 hours, then recovering completely—only to have it happen again weeks or months later. This condition primarily affects children between ages 3-7, though adults can develop it too (Greenberger, 2013).

HRV Biofeedback Addresses Autonomic Imbalance

Here's where the gut-brain connection becomes therapeutically useful. Richard Gevirtz, a pioneering researcher in this area, proposed that FAP is associated with vagal deficiency—essentially, the parasympathetic "rest and digest" branch of the autonomic nervous system isn't active enough. When vagal tone is low, the gut becomes hypersensitive and overreactive. A series of three uncontrolled studies (Humphreys & Gevirtz, 2000; Sowder et al., 2010; Stern et al., 2014) tested whether heart rate variability biofeedback could restore balance.

How might HRV biofeedback help? Researchers propose multiple pathways (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014). First, it stimulates the baroreflex—a feedback loop that helps stabilize blood pressure and, more broadly, autonomic function. Second, vagal afferent signals travel up to brain regions (the limbic system and prefrontal cortex) where pain perception is processed and can be modulated. Third, remember that cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway we discussed with arthritis? It applies here too—enhanced vagal tone can reduce gut inflammation. The overall effect is like resetting a dysfunctional communication system: the gut and brain start "talking" normally again.

Clinical Efficacy

Based on three uncontrolled studies, Richard Gevirtz (2023) rated HRV biofeedback as level 3 - probably efficacious for functional abdominal pain in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). Why "probably" rather than definitely? The studies lacked control groups, so we can't rule out placebo effects or spontaneous improvement. Still, participants showed meaningful improvements: higher vagal tone (measured through HRV metrics), fewer GI symptoms like nausea, diarrhea, and constipation, reduced functional disability, and better quality of life.

These converging improvements across physiological and symptomatic measures strengthen the case that HRV biofeedback is doing something real.

Ten-year-old Jason missed so much school due to stomach pain that his grades suffered and he felt isolated from friends. Medical workups found no physical cause. His pediatrician referred him for HRV biofeedback training. Over eight sessions, Jason learned resonance frequency breathing and practiced with a portable device at home. His stomach pain episodes decreased from daily to once weekly, and he regained confidence in his ability to manage symptoms when they occurred.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome: The Most Common Functional GI Disorder

If you've ever had butterflies in your stomach before a presentation, you've experienced a mild version of what IBS patients live with constantly. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common functional GI disorder, accounting for 12% of primary care visits and 28% of gastroenterological visits (Chiarioni & Whitehead, 2008). That's an enormous healthcare burden for a condition with no visible abnormality.

IBS features abdominal pain or discomfort combined with altered bowel habits—constipation, diarrhea, or maddening alternation between both. Current research views IBS as a disorder of the gut-brain axis, involving bidirectional miscommunication between the central nervous system and the digestive tract (Mayer et al., 2023).

What goes wrong? Several things: the gut microbiome becomes unbalanced (dysbiosis), the intestinal lining becomes hypersensitive to normal stimuli (visceral hypersensitivity), low-grade inflammation develops in the gut wall, and the stress-response system (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal or HPA axis) becomes dysregulated (Palaniswamy, 2025). Notice how these mechanisms involve both physical changes in the gut and nervous system dysfunction—which explains why IBS is so frustrating for patients whose doctors keep saying "nothing is wrong."

Who Develops IBS?

IBS is remarkably common. A 2024 meta-analysis across 52 countries estimated the global prevalence at approximately 14%—higher than previous estimates (Alqahtani et al., 2024). However, the numbers vary dramatically depending on which diagnostic criteria are used. The Rome Foundation Global Study reported 3.8% prevalence using the stricter Rome IV criteria, compared to 10.1% using the older Rome III criteria (Huang et al., 2023). This difference matters clinically: Rome IV requires more frequent symptoms, so it identifies more severely affected patients.

Women are about 1.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with IBS than men (Alqahtani et al., 2024)—though whether this reflects true prevalence differences or differential help-seeking behavior remains debated. Psychological factors significantly influence IBS development, with research showing increased risk associated with stress, anxiety, and depression.

These aren't just correlations; the relationship is likely bidirectional, with gut dysfunction worsening mood and psychological distress worsening gut symptoms. Most IBS patients develop symptoms before age 35. When IBS-like symptoms first appear in older adults, clinicians should investigate carefully to rule out more serious conditions like inflammatory bowel disease or colon cancer.

Biofeedback Helps Restore Normal Function

Given that IBS involves gut-brain miscommunication and stress system dysregulation, it makes sense that biofeedback might help—and research supports this. A series of uncontrolled studies (Leahy et al., 1998; Schwartz et al., 1990) and randomized controlled trials (Blanchard et al., 1992; Dobbin et al., 2013) examined whether BART, often combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and hypnotherapy, could reduce IBS symptoms. These multicomponent approaches target different aspects of the disorder: biofeedback addresses autonomic dysregulation, CBT addresses maladaptive thoughts and behaviors, and hypnotherapy can modulate gut sensitivity.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on IBS

Clinical Efficacy

Based on five RCTs, Donald Moss and Mark Watkins rated rectosigmoid and temperature biofeedback with Progressive Relaxation for IBS as level 4 - efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). What's "rectosigmoid biofeedback"? It trains patients to normalize activity in the lower colon—the rectosigmoid region—where many IBS symptoms originate. Combined with temperature biofeedback (addressing overall autonomic balance) and Progressive Relaxation (reducing muscle tension and overall stress), this multimodal approach produced significant reductions in GI and IBS symptoms.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders share a common thread: disrupted gut-brain communication that biofeedback can help restore. HRV biofeedback is rated probably efficacious (level 3) for functional abdominal pain, working through baroreflex stimulation, vagal afferent pathways, and anti-inflammatory effects. For IBS, rectosigmoid and temperature biofeedback with Progressive Relaxation achieves efficacious status (level 4). The gut-brain axis provides a compelling rationale for these interventions—by normalizing autonomic function, biofeedback helps the gut and brain "talk" properly again.

Comprehension Questions

- What distinguishes functional abdominal pain from other GI conditions?

- How might HRV biofeedback help with functional abdominal pain?

- What efficacy rating did biofeedback for IBS receive?

- Why might symptoms in older adults warrant additional medical investigation?

Diabetes Mellitus: A Metabolic Challenge

Diabetes might seem like an unlikely candidate for biofeedback treatment—after all, it's fundamentally a problem with insulin, a hormone. But here's the connection: stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline directly raise blood sugar, and chronic stress keeps blood sugar chronically elevated.

Additionally, diabetes causes vascular complications that restrict blood flow—and temperature biofeedback can help restore circulation to tissues starved of oxygen and nutrients.

Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) either don't produce enough insulin (Type 1) or can't use insulin properly (Type 2). Without adequate insulin function, glucose accumulates in the blood—a state called hyperglycemia. Over time, this damages small blood vessels (microvascular complications) in the eyes, kidneys, and peripheral nerves, and contributes to cardiovascular disease (Rhoades & Bell, 2013).

The Growing Epidemic

Diabetes is one of the great public health challenges of our time—and the numbers keep growing. The 2024 National Diabetes Statistics Report indicates that approximately 40.1 million Americans (12% of the population) have diabetes, with a troubling 11 million adults unaware of their condition (CDC, 2024). Even more striking: during 2021-2023, diabetes prevalence among U.S. adults reached 15.8%, up dramatically from 9.7% in 1999-2000 (Gwira et al., 2024). That's more than a 60% increase in just two decades. Prevalence increases with age, reaching 27.3% among adults 60 and older—meaning over a quarter of older Americans are managing this chronic condition.

Diabetes complications create enormous suffering and healthcare costs. Diabetic foot lesions remain a leading cause of hospitalization. About 15% of diabetes patients develop foot ulcers during their lifetime, and alarmingly, 12-24% of these individuals ultimately require amputation. Men are more likely to have diabetes than women (18% vs. 13.7%), and prevalence decreases with higher educational attainment—another reminder of how social factors influence health (Gwira et al., 2024).

Lifestyle Changes Make a Powerful Difference

Before discussing biofeedback, it's worth emphasizing that lifestyle changes can be remarkably powerful—sometimes more effective than medication. The landmark Diabetes Prevention Program trial demonstrated that modest changes—losing 5-7% of body weight and increasing activity by about 30 minutes daily—reduced diabetes risk by 58%.

For comparison, the oral medication metformin reduced risk by only 31% over the same 3-year period. Even more impressive: a 15-year follow-up study showed these lifestyle changes reduced progression to diabetes by 28%, compared to 18% for metformin (Living Well with Diabetes, 2018). This isn't just about weight loss—physical activity independently improves insulin sensitivity, and the psychological benefits of self-efficacy shouldn't be underestimated.

Biofeedback for Glycemic Control

How might biofeedback improve blood sugar control? The connection runs through the stress response. When you're stressed, your body releases cortisol and adrenaline, which signal the liver to dump glucose into the bloodstream—a survival mechanism that makes sense if you're fleeing a predator but causes problems when the "threat" is work deadlines or family conflict.

Biofeedback-assisted relaxation training (BART) can help patients learn to down-regulate this stress response, reducing the hormonal triggers that spike blood sugar.

The research base is substantial. Four case studies (Bailey, McGrady, & Good, 1990; Fowler, Budzynski, & VandenBergh, 1976; McGrady & Gerstenmaier, 1990; Seeburg & DeBoer, 1980), one uncontrolled study (Rosenbaum, 1983), and six RCTs (Jablon et al., 1997; Lane et al., 1993; McGinnis et al., 2005; McGrady et al., 1991; Miley, 1989; Surwit & Feinglos, 1983) have evaluated whether biofeedback or BART can improve glycemic control. The modalities tested include EMG biofeedback, temperature biofeedback, or combinations of both.

Clinical Efficacy

Based on six RCTs, Fred Shaffer rated biofeedback for glycemic control as efficacious and specific—the highest evidence rating. This means biofeedback demonstrated superior benefits compared to credible alternative treatments, not just usual care or placebo.

Intermittent Claudication: When Walking Becomes Painful

Imagine having to stop every block because your legs cramp so badly you can't continue walking. That's intermittent claudication—cramping leg pain triggered by exercise, caused by inadequate blood flow to leg muscles. The term comes from Latin "claudicare" (to limp), and it perfectly describes the characteristic stop-start gait of affected individuals.

The connection to biofeedback is straightforward: if the problem is insufficient blood flow, and temperature biofeedback can teach people to increase blood flow to their extremities, then it might help. Two case studies (Aikens, 1991; Saunders et al., 1994) and one within-subjects study (Rice & Schindler, 1992) tested this hypothesis using BART with temperature biofeedback.

Clinical Efficacy

Fred Shaffer and Zachary Meehan (2016) rated biofeedback for intermittent claudication as level 2 - possibly efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (3rd ed.). The "possibly" rating reflects limited evidence from small studies without control groups—promising but not yet definitive.

Diabetic Ulcers: A Preventable Complication

Here's a sobering scenario that plays out thousands of times yearly: a person with diabetes steps on a small object, perhaps a pebble or piece of glass. They don't feel it because nerve damage has numbed their feet. Days or weeks pass before they notice the wound—by which time infection has set in. Without aggressive treatment, the infection spreads, tissue dies, and amputation becomes necessary. This cascade of events explains why foot ulcers are among the most feared diabetes complications.

Why are diabetic patients so vulnerable? Two factors combine. First, progressive damage to sensory nerves—peripheral neuropathy—reduces or eliminates sensation from the feet and legs. Patients literally can't feel injuries that would be immediately obvious to someone with intact nerves. Second, diabetes damages small blood vessels, reducing blood flow (perfusion) to the extremities. Without adequate blood supply, wounds heal slowly and tissues become vulnerable to infection.

In severe cases, patients develop Charcot foot deformity. Without normal pressure sensations, they place excessive stress on their feet while walking. This causes reduced tissue blood flow (ischemia), localized tissue death (necrosis), and eventually microfractures in the foot bones (Fishman, 2004). The foot literally breaks down from repeated unperceived trauma.

Can biofeedback help? The rationale is compelling: if reduced blood flow contributes to ulcer formation and poor healing, then increasing blood flow to the extremities should help. Temperature biofeedback trains patients to dilate blood vessels in their hands—and this learned vasodilation can transfer to the feet. A series of case studies (Shulimson et al., 1986), an uncontrolled study (Fiero et al., 2003), and an RCT (Rice et al., 2001) demonstrated that temperature BART could increase lower extremity perfusion and actually heal diabetic ulcers that had resisted other treatments.

Clinical Efficacy

Fred Shaffer and Zachary Meehan (2016) rated biofeedback for diabetic ulcers as level 3 - probably efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (3rd ed.). The evidence suggests biofeedback can meaningfully improve outcomes, though more RCTs would strengthen the case.

Robert, a 58-year-old with Type 2 diabetes, developed a small ulcer on his foot that was not healing despite standard wound care. His podiatrist added temperature biofeedback training to his treatment plan. Robert learned to increase blood flow to his feet through handwarming exercises, practicing twice daily. Over three months, his foot temperature increased by 4 degrees Fahrenheit, and the ulcer finally closed. Robert continues to use the technique preventively.

Biofeedback offers multiple evidence-based applications for diabetes management. BART for glycemic control achieves the highest rating—efficacious and specific—based on six RCTs, working by reducing stress hormones that elevate blood sugar. Temperature biofeedback is probably efficacious for diabetic ulcers (increasing blood flow to promote healing) and possibly efficacious for intermittent claudication. The common mechanism across these applications? Biofeedback helps restore adequate blood flow to tissues compromised by diabetic vascular damage while reducing the stress responses that worsen metabolic control.

Comprehension Questions

- What lifestyle changes can significantly reduce diabetes risk?

- Why are diabetic patients at increased risk for foot ulcers?

- What efficacy rating did biofeedback for glycemic control receive?

- How might temperature biofeedback help heal diabetic ulcers?

Hyperhidrosis: When Sweating Becomes Excessive

Sweating is normal—it's how your body cools itself. But for people with hyperhidrosis, sweating becomes excessive, embarrassing, and life-limiting. Imagine being afraid to shake hands at a job interview because your palms are dripping wet, or avoiding social situations because you're constantly soaked through your clothes despite sitting in an air-conditioned room.

Hyperhidrosis patients perspire constantly, often without any obvious trigger like exercise or heat. The most common sites are the palms and soles, though armpits, chest, and back can also be affected. There are two main types:

Generalized hyperhidrosis involves excessive sweating throughout the body. It may reflect autonomic nervous system dysregulation—essentially, the "thermostat" controlling sweating is set too sensitive. It can also be secondary to metabolic diseases, fever-inducing illnesses, or cancer.

Localized hyperhidrosis affects specific body areas, most commonly the hands, feet, or armpits. The causes may include abnormal regrowth of damaged sympathetic nerve fibers, unusual numbers or arrangements of sweat glands, or vascular abnormalities. Localized hyperhidrosis often first appears in childhood or adolescence, while generalized hyperhidrosis more commonly starts in adulthood.

Both forms can be devastating socially and occupationally (Altman, 2004)—patients describe avoiding physical contact, constantly carrying backup clothes, and feeling intense shame about a problem others dismiss as trivial.

Conventional treatments include prescription antiperspirants, Botox injections (which temporarily paralyze sweat glands), lotions, oral medications, and in severe cases, endoscopic transthoracic sympathectomy (ETS)—a surgery that cuts the sympathetic nerves controlling sweating. This last option illustrates how desperately some patients want relief, given that surgery carries risks including permanent compensatory sweating in other body areas.

Demographics

Hyperhidrosis is more common than most people realize. Research now estimates that 4.8% of the U.S. population—approximately 15.3 million people—are affected, nearly twice as many as previously believed (Doolittle et al., 2016). To put this in perspective, hyperhidrosis is more common than melanoma, psoriasis, and peanut allergies. Globally, approximately 385 million people deal with this condition (International Hyperhidrosis Society, 2024).

The age distribution is interesting: prevalence peaks at 8.8% among 18-39 year olds—prime working and dating years when excessive sweating causes maximum social disruption—and drops to 2.1% among children and adolescents (Doolittle et al., 2016).

Palmoplantar hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating from hands and feet) varies across ethnic populations. Among affected individuals, axillary (armpit) hyperhidrosis is most common at 68%, followed by palmar (hand) at 65% and plantar (foot) at 64%—many patients have multiple affected areas (Doolittle et al., 2016).

Perhaps most striking: despite high prevalence, only 51% of affected individuals ever mention their symptoms to a healthcare provider, often assuming nothing can be done.

The Rationale for Electrodermal Biofeedback

The logic connecting electrodermal biofeedback to hyperhidrosis treatment is beautifully direct. Sweat glands are controlled by the sympathetic nervous system—the same system that activates during the "fight-or-flight" response. When sympathetic activity increases, sweat production increases. More sweat on the skin means higher skin conductance (because sweat is salty and conducts electricity). Electrodermal biofeedback lets patients see their skin conductance in real-time.

By learning to reduce skin conductance, they're learning to reduce sympathetic activation—which should reduce sweating.

There's also a stress connection. For patients whose hyperhidrosis worsens during stressful situations (job interviews, first dates, public speaking), biofeedback-assisted stress management could break the vicious cycle: stress triggers sweating, awareness of sweating increases stress, which triggers more sweating, and so on.

What does the research show? Duller and Gentry (1980) reported successful treatment using visual water vapor biofeedback—patients could literally watch the moisture evaporating from their skin and learn to reduce it. Of 14 adults treated, 11 showed significant improvement 6 weeks after treatment ended. The authors speculated that the relaxation training component might have driven the improvements.

Singh and Singh (1993) found that electrodermal biofeedback-assisted relaxation helped 6 of 10 male patients significantly reduce their sweating. Importantly, they found a strong correlation between reductions in skin conductivity during training and clinical improvement—suggesting patients who learned the skill best got the best results.

Clinical Efficacy

Based on two uncontrolled studies and two case studies using electrodermal (GSR and SC) and water vapor biofeedback for hyperhidrosis, Fred Shaffer and Branden Schaff (2023) rated biofeedback as level 2 - possibly efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). Why only "possibly"? The existing studies used weak designs (no control groups) with small samples. The results are promising—most patients improved—but without controlled trials, we can't rule out placebo effects or spontaneous improvement. This is an area ripe for more rigorous research.

Hyperhidrosis treatment with electrodermal biofeedback receives a "possibly efficacious" rating—promising but limited by small, uncontrolled studies. The mechanism is straightforward: biofeedback helps patients reduce sympathetic activation, which directly controls sweat gland activity. For stress-triggered hyperhidrosis, breaking the anxiety-sweating-more anxiety cycle may be particularly valuable. The field needs RCTs with adequate sample sizes to establish stronger efficacy.

Immune Function: The Mind-Body Connection

Can learning to relax actually boost your immune system? It sounds like the kind of claim you'd find in a self-help book, but there's legitimate science behind it. Your immune system and nervous system are intimately connected—they share chemical messengers, their cells have receptors for each other's signals, and chronic stress demonstrably suppresses immune function. This section explores whether biofeedback can harness this connection therapeutically.

First, let's understand how your body defends itself. The immune system operates through two complementary approaches:

The innate (nonspecific) immune system responds rapidly to any threat. Think of it as your body's first responders—always ready, not picky about targets. These mechanisms include physical barriers (skin and mucous membranes), phagocytosis (where macrophages and neutrophils literally eat microorganisms), destruction of infected cells by natural killer cells, release of antimicrobial chemicals (hydrochloric acid in the stomach, interferons, lysozyme in tears), and local inflammatory responses that contain invaders while summoning reinforcements.

The adaptive (specific) immune system is slower but smarter. It learns to recognize specific threats and remembers them for faster responses next time—the principle behind vaccination. Key players include B cells (which produce antibodies that tag invaders for destruction), T cells (which directly attack infected or cancerous cells), and memory cells (which provide lasting immunity). This system explains why you typically only get chickenpox once—your adaptive immune system remembers (Shaffer & Bartochowski, 2016).

Can Biofeedback Enhance Immunity?

Six randomized controlled trials (McGrady et al., 1991; Taylor, 1995; Coen et al., 1996; Birk et al., 2000; Kern-Buell et al., 2000; Nolan et al., 2012) tested whether interventions including biofeedback components (SEMG and temperature) could measurably improve immune markers.

Lehrer and colleagues (2010) used a particularly clever design: they tested whether HRV biofeedback training could protect subjects from the effects of a bacterial toxin injection (lipopolysaccharide or LPS). This toxin normally triggers a strong inflammatory response—if biofeedback blunted that response, it would demonstrate real immune system effects, not just changes in how people feel.

Schummer, Noh, and Mendoza (2013) investigated whether neurofeedback could increase CD4+ cells—the "helper T cells" that orchestrate immune responses. Low CD4+ counts characterize HIV/AIDS and other immunocompromised conditions. Collectively, these studies suggest that biofeedback and neurofeedback show promise for boosting immune function, with particular relevance for patients whose immunity is already compromised (Shaffer & Bartochowski, 2016).

Clinical Efficacy

Based on the available RCTs, Fred Shaffer (2023) rated biofeedback for immune function as level 3 - probably efficacious. The measured improvements include increased natural killer (NK) cell activity (important for fighting cancer and viruses), higher CD4+ cell counts and percentages, elevated salivary sIgA (an antibody that protects mucous membranes), and increased vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) concentration (which has anti-inflammatory effects). These aren't just abstract numbers—they represent real improvements in the body's defensive capabilities.

Biofeedback for immune enhancement receives a "probably efficacious" rating based on multiple RCTs showing improvements in NK cell activity, CD4+ counts, salivary antibodies, and anti-inflammatory markers. The mechanism connects autonomic regulation to immune function—the same stress reduction that helps with other autonomic conditions appears to free up resources for immune defense. This application is particularly promising for immunocompromised populations, though more research is needed across diverse patient groups.

Comprehension Questions

- What is the difference between innate and adaptive immunity?

- Which biofeedback modalities have been studied for immune enhancement?

- What immune markers have shown improvement with biofeedback training?

Motion Sickness: Training the Autonomic Nervous System

Nearly everyone has experienced motion sickness at some point—that queasy, cold-sweating, green-around-the-gills feeling during a car ride, boat trip, or turbulent flight. For most people, it's an occasional annoyance. But for some—including military pilots, astronauts, and virtual reality users—motion sickness can be career-threatening or mission-critical. Fortunately, biofeedback offers one of the most robust solutions available.

Motion sickness occurs when your brain receives conflicting information from different sensory systems. Your eyes might say you're stationary (reading in a car), while your inner ear's vestibular system screams that you're moving. Your body's proprioceptors (which sense position and movement) add another layer of input.

The sensory conflict theory remains the most widely accepted explanation: symptoms arise when actual sensory signals deviate from what the brain expects based on internal models of body movement (Allred & Clark, 2025).

A recent refinement, subjective vertical conflict theory, proposes that motion sickness specifically occurs when your perceived direction of gravity conflicts with expected orientation—explaining why unusual motions (like a boat's roll) are particularly provocative (Wada et al., 2025). Here's a fascinating detail: people without functioning vestibular systems don't get motion sick—the inner ear's balance organs are required for the conflict to occur.

The symptoms of motion sickness go beyond just feeling queasy. They include stomach awareness, nausea and vomiting, and drowsiness, accompanied by measurable physiological changes: increased sweating, facial pallor, elevated heart rate, higher skin conductance, body temperature fluctuations, and sometimes cardiac arrhythmias (Cowings et al., 1986; Graybiel & Lackner, 1980). These autonomic responses explain why biofeedback—which trains control over exactly these systems—can be so effective.

NASA's Autogenic-Feedback Training

Patricia Cowings and colleagues at NASA developed autogenic-feedback training (AFT) specifically to help astronauts and pilots overcome motion sickness. The approach combines autogenic training (a relaxation method using self-suggestion) with biofeedback to give participants control over their autonomic responses to motion stress. Their research program has demonstrated that AFT can normalize autonomic responses and that these improvements are stable over time and transfer to real-world situations.

The longevity of results is particularly impressive. Cowings and Toscano (1982) demonstrated that training benefits remained stable one year after AFT ended—patients didn't just feel better temporarily; they learned lasting self-regulation skills. Stout, Toscano, and Cowings (1995) showed that physiological responses to motion sickness challenges were consistent across three separate provocative tests.

In military applications, Cowings and colleagues (1994) achieved dramatic results with high-performance pilots who were severely motion sick before training. After AFT, these pilots maintained normal flight performance while using the self-regulation techniques they had learned—meaning the skills transferred from the lab to the cockpit under real-world conditions.

Other Approaches

Simpler techniques also show promise. Russell and colleagues (2014) found that controlled diaphragmatic breathing—slow, deep belly breathing—could significantly reduce motion sickness in a virtual reality environment compared to normal breathing. This finding suggests that even basic autonomic regulation techniques can help, though AFT's comprehensive approach appears most effective for severe cases.

Clinical Efficacy

Based on four RCTs, Fred Shaffer and Zachary Meehan (2023) rated biofeedback for motion sickness as level 4 - efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). This high rating reflects consistent evidence that AFT normalizes autonomic responses, reduces symptom severity, and improves tolerance of provocative stimuli—with benefits that persist over time and transfer to real-world situations.

Lieutenant Commander Walsh, a naval aviator, developed severe airsickness that threatened his career. Despite excellent piloting skills, he vomited during every flight. After completing AFT with NASA, he learned to recognize early autonomic signs of motion stress and apply self-regulation techniques. He returned to full flight status and reported that he could now control his symptoms even during aggressive maneuvers.

Autogenic-feedback training for motion sickness achieves the "efficacious" rating (level 4) based on extensive NASA research and four RCTs—among the strongest evidence for any application in this chapter. AFT normalizes autonomic responses to motion stress, produces lasting benefits, and transfers effectively to real-world situations like flight. For those seeking simpler approaches, controlled diaphragmatic breathing also shows promise. The success of biofeedback for motion sickness demonstrates that even seemingly automatic responses to sensory conflict can be brought under voluntary control with proper training.

Comprehension Questions

- What causes motion sickness at a physiological level?

- Who developed autogenic-feedback training for motion sickness?

- What efficacy rating did biofeedback for motion sickness receive?

- How long do the benefits of AFT typically last?

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, consider how the evidence varies across these diverse autonomic applications. Create a simple table ranking each condition by its efficacy rating, then answer these questions:

Which two conditions have the strongest evidence supporting biofeedback treatment? What characteristics do these conditions share that might explain why biofeedback works particularly well for them?

Which conditions have weaker evidence ratings? What would it take to move these conditions to higher efficacy levels—more studies, different study designs, or different biofeedback modalities?

If a client came to you with one of these conditions, how would you explain the evidence base to them honestly while still conveying appropriate optimism about treatment?

Cutting Edge Topics

The Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway: How Relaxation Reduces Inflammation

One of the most exciting discoveries in mind-body medicine is that the vagus nerve directly regulates inflammation throughout the body through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Here's how it works: vagal efferent signals stimulate the release of acetylcholine (the neurotransmitter associated with "rest and digest" functions), which binds to α7 nicotinic receptors on immune cells. When these receptors are activated, they inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β (Gitler et al., 2025). This provides a direct biological mechanism explaining why relaxation isn't just psychologically helpful—it physically turns down inflammation at the cellular level. HRV biofeedback, which enhances vagal tone through resonance frequency breathing, appears to activate this pathway, potentially explaining its benefits for conditions involving chronic inflammation like rheumatoid arthritis, IBS, and cardiovascular disease. This discovery transforms our understanding of "stress management" from a soft psychological concept to a concrete physiological intervention.

The Gut-Brain Axis: A Two-Way Street

Your gut isn't just a digestive organ—it's a "second brain" containing over 100 million neurons that constantly communicates with your central nervous system through neural, hormonal, and immune pathways. This bidirectional gut-brain axis explains why you get butterflies when nervous and why GI conditions respond to psychological interventions. Recent research has uncovered how gut microbiome dysbiosis contributes to IBS through multiple mechanisms: altered bile acid metabolism, disrupted intestinal permeability ("leaky gut"), low-grade mucosal inflammation, and changes in neurotransmitter production—including serotonin, of which 95% is actually produced in the gut (Palaniswamy, 2025). HRV biofeedback that restores parasympathetic balance shows promise for normalizing this gut-brain communication. Understanding the gut-brain axis helps explain why "it's all in your head" is both wrong (the gut is a real site of pathology) and right (the brain profoundly influences gut function).

Wearable Technology: Biofeedback Goes Home

Consumer-grade wearable devices now offer real-time HRV monitoring and biofeedback capabilities that would have required expensive laboratory equipment just a decade ago. Smartwatches, chest straps, and finger sensors can track heart rate variability and guide resonance frequency breathing exercises. These technologies allow patients to practice autonomic self-regulation throughout their daily lives—not just during weekly clinic visits. Research is examining whether home-based HRV training using wearables can achieve benefits comparable to traditional laboratory-based biofeedback for conditions like IBS, anxiety, and chronic pain (Gitler et al., 2025). The democratization of biofeedback technology could dramatically expand access to effective treatment, though questions remain about optimal training protocols and whether self-guided practice can match clinician-supervised sessions. For biofeedback practitioners, wearables offer new opportunities for extending treatment between sessions and monitoring patient progress in real-world environments.

GLP-1 Agonists: Pharmacological Parallels to Biofeedback

GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs)—medications like semaglutide, liraglutide, and tirzepatide—have emerged as transformative treatments for diabetes and obesity. What makes them relevant to biofeedback practitioners is their mechanism: like HRV biofeedback, they reduce inflammation through pathways that inhibit NF-κB, the master switch for pro-inflammatory cytokine production. This creates pharmacological effects that parallel and potentially complement biofeedback's neural anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

For joint disorders, the evidence is compelling. The STEP 9 trial (Bliddal et al., 2024) found that semaglutide reduced knee osteoarthritis pain by 41.7 points on the WOMAC scale (versus 27.5 for placebo) over 68 weeks—benefits exceeding what weight loss alone would predict. Laboratory studies show GLP-1 RAs directly reduce joint inflammation by downregulating TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in synovial tissue (the same cytokines targeted by the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway). Research presented at the 2025 ACR conference found that rheumatoid arthritis patients taking GLP-1 agonists alongside DMARDs experienced fewer disease flares.

For functional GI disorders, the picture is nuanced. GLP-1 RAs slow gastric emptying—helpful for IBS-D (diarrhea-predominant) patients but potentially problematic for IBS-C. A 2025 meta-analysis found that ROSE-010, a GLP-1 analog, provided significant pain relief in IBS, particularly for constipation-predominant and mixed subtypes (Mostafa & Alrasheed, 2025). However, the common side effects of nausea and GI disturbance mean practitioners should inquire about GLP-1 use when treating IBS patients with biofeedback.

For diabetic neuropathy, GLP-1 RAs show neuroprotective effects independent of glucose control. Studies demonstrate improvements in nerve conduction, clinical neuropathy scores, and even reversal of nerve morphological abnormalities within one month of treatment (Dhanapalaratnam et al., 2024). The mechanism involves restoration of Na+/K+-ATPase pump function—essential for proper nerve signaling. This has implications for diabetic ulcer prevention: if GLP-1 agonists protect sensory nerve function while temperature biofeedback improves circulation, the combination could offer complementary benefits.

Clinical implications: Patients on GLP-1 agonists may show altered baselines—significant weight loss changes thermal regulation, and the medications' anti-inflammatory effects may enhance response to biofeedback. GI side effects during dose escalation could temporarily interfere with relaxation training. However, the shared anti-inflammatory mechanisms (GLP-1 RAs via NF-κB inhibition; biofeedback via the cholinergic pathway) suggest potential synergy. Note that GLP-1 cardiovascular effects are covered in the Cardiovascular Applications chapter.

Glossary

arthritis: Inflammatory joint disease featuring infectious or noninfectious inflammatory attacks on joint lining and cartilage.

autogenic-feedback training (AFT): A biofeedback training protocol developed by Patricia Cowings at NASA to counteract motion sickness through autonomic self-regulation.

biofeedback-assisted relaxation training (BART): A treatment approach combining biofeedback with relaxation procedures to address autonomic dysregulation.

cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: A neural mechanism whereby vagal efferent signals stimulate acetylcholine release, which binds to α7 nicotinic receptors on immune cells to inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine production.

cyclic vomiting syndrome: A condition featuring periodic, severe episodes of nausea and vomiting lasting from a few hours to days with complete recovery between episodes.

diabetes mellitus (DM): A metabolic disorder in which patients fail to produce or utilize insulin, leading to hyperglycemia and related complications.

foot ulcers: Open wounds on the feet that develop in diabetic patients due to neurologic and microvascular causes.

functional abdominal pain (FAP): Recurrent abdominal pain without identifiable pathology such as tumors, obstruction, or inflammatory bowel disease.

functional gastrointestinal disorders: GI conditions diagnosed by their symptoms rather than structural abnormalities, including cyclic vomiting, irritable bowel syndrome, and functional abdominal pain.

GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs): A class of medications that mimic the hormone glucagon-like peptide-1, originally developed for diabetes and obesity but increasingly recognized for anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects relevant to conditions including arthritis, IBS, and diabetic neuropathy.

generalized hyperhidrosis: Excessive sweating throughout the body, possibly caused by autonomic dysregulation, metabolic disease, fever-inducing illness, or cancer.

gut-brain axis: The bidirectional communication system between the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract, involving neural, hormonal, and immune pathways.

hyperhidrosis: Excessive sweating beyond what is needed for temperature regulation.

inflammatory joint disease: Joint disorders characterized by infectious or noninfectious inflammatory attacks on joint lining and cartilage.

intermittent claudication: Cramping leg pain triggered by exercises like walking, caused by inadequate blood flow to leg muscles.

irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): The most common functional GI disorder, featuring abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered bowel habits.

juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA): The most common chronic rheumatologic condition in children, characterized by arthritis appearing before age 16 that persists longer than 6 weeks. JIA has replaced the older term juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) and encompasses seven distinct subtypes.

localized hyperhidrosis: Excessive sweating confined to specific body areas, often the palms, soles, or armpits.

motion sickness: Symptoms including nausea, vomiting, and drowsiness caused by mismatched sensory information from the eyes, vestibular system, and proprioceptors.

osteoarthritis (OA): Age-related joint disorder involving articular cartilage damage and loss.

palmoplantar hyperhidrosis: Excessive sweating specifically from the hands and feet.

pathophysiology, biofeedback modalities, and treatment protocols for specific ANS biofeedback applications (IV-D): A component of the BCIA Biofeedback Blueprint addressing autonomic nervous system applications.

preeclampsia: A pregnancy complication involving elevated blood pressure and abnormal protein concentration in the urine after the 20th week of gestation.

pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH): Another term for preeclampsia.

recurrent abdominal pain (RAP): Another term for functional abdominal pain.

rheumatoid arthritis (RA): A chronic noninfectious autoimmune disorder characterized by synovial joint swelling and pain due to progressive damage and destruction.

sensory conflict theory: The predominant explanation for motion sickness, proposing that symptoms arise when actual sensory signals from the vestibular, visual, and proprioceptive systems deviate from what the brain expects based on internal models of body movement.

sFlt-1 (soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1): An anti-angiogenic protein released by the placenta that is elevated in preeclampsia and contributes to endothelial dysfunction by binding pro-angiogenic factors.

soluble endoglin: An anti-angiogenic factor elevated in preeclampsia that antagonizes the TGF-β pathway and contributes to vascular dysfunction.

subjective vertical conflict: A refinement of sensory conflict theory proposing that motion sickness specifically arises when the perceived direction of gravity conflicts with expected gravitational orientation.

two-stage model: The current framework for understanding preeclampsia pathogenesis, with Stage 1 involving abnormal placentation and reduced perfusion, and Stage 2 involving systemic maternal pathophysiology driven by anti-angiogenic factors.

References

AlButaysh, O. F., AlQuraini, A. A., Almukhaitah, A. A., Alahmdi, Y. M., & Alharbi, F. S. (2020). Epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome and its associated factors in Saudi undergraduate students. Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology: Official Journal of the Saudi Gastroenterology Association, 26(2), 89-93. https://doi.org/10.4103/sjg.SJG_459_19

Allred, A. R., & Clark, T. K. (2025). Validating sensory conflict theory and mitigating motion sickness in humans with galvanic vestibular stimulation. Communications Engineering, 4, Article 417. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44172-025-00417-2

Alqahtani, M. M., Alanazi, A. M., Alshammari, T. S., Alqarni, S. A., Alrasheedi, F. A., Almazyad, N. S., Bin Hamad, A. F., Alamri, H. S., Alatawi, H. M., & Almohammadi, A. A. (2024). Global prevalence and risk factors of irritable bowel syndrome from 2006 to 2024 using the Rome III and IV criteria: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000002889

Blanchard, E. B., Schwartz, S. P., Suls, J. M., Gerardi, M. A., Scharff, L., Greene, B., . . . Malamood, H. S. (1992). Two controlled evaluations of multicomponent psychological treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Behavioral Research and Therapy, 30(2), 175-189.

Bliddal, H., Bays, H., Czernichow, S., Uddén Hemmingsson, J., Hjelmesæth, J., Hoffmann Morville, T., Koroleva, A., Skov Neergaard, J., Vélez Sánchez, P., Wharton, S., Wizert, A., & Kristensen, L. E. (2024). Once-weekly semaglutide in persons with obesity and knee osteoarthritis. New England Journal of Medicine, 391(17), 1573-1583. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2403664

Brainard, A. (2014). Motion sickness. eMedicine.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Prevalence of diagnosed arthritis—United States, 2019-2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(41), 1101-1107. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7241a1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). National diabetes statistics report. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/index.html

Chiarioni, G., & Whitehead, W. E. (2008). The role of biofeedback in the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 5(7), 371-382.

Cowings, P. S., Naifeh, K. H., & Toscano, W. B. (1990). The stability of individual patterns of autonomic responses to motion sickness stimulation. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 61(5), 399-405.

Cowings, P. S., Suter, S., Toscano, W. B., Kamiya, J., & Naifeh, K. (1986). General autonomic components of motion sickness. Psychophysiology, 23(5), 542-551.

Cowings, P. S., & Toscano, W. B. (1982). The relationship of motion sickness susceptibility to learned autonomic control for symptom suppression. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 53(6), 570-575.

Cowings, P. S., Toscano, W. B., Miller, N. E., & Reynoso, S. (1994). Autogenic-feedback training as a treatment for airsickness in high-performance military aircraft: Two cases. (NASA Technical Memorandum No. 108810). Moffett Field, CA: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Ames Research Center.

Cullins, S. W., Gevirtz, R. N., Poeltler, D. M., Cousins, L. M., Edward Harpin, R., & Muench, F. (2013). An exploratory analysis of the utility of adding cardiorespiratory biofeedback in the standard care of pregnancy-induced hypertension. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 38(3), 161-170.

Dobbin, A., Dobbin, J., Ross, S. C., Graham, C., & Ford, M. J. (2013). Randomized controlled trial of brief intervention with biofeedback and hypnotherapy in patients with refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 43(1), 15-23.

Dhanapalaratnam, R., Issar, T., Lee, A. T. K., Poynten, A. M., Milner, K. L., Kwai, N. C. G., & Krishnan, A. V. (2024). Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists reverse nerve morphological abnormalities in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetologia, 67(3), 561-566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-023-06072-6

Doolittle, J., Walker, P., Mills, T., & Thurston, J. (2016). Hyperhidrosis: An update on prevalence and severity in the United States. Archives of Dermatological Research, 308(10), 743-749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-016-1697-9

D'Orazio, A., Cirillo, A. L., Greco, G., Di Ruscio, E., Latorre, M., Pisani, F., Alunno, A., & Puxeddu, I. (2024). Pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: One year in review 2024. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 42(9), 1707-1713. https://doi.org/10.55563/clinexprheumatol/0307ed

Dobie, T. G., May, J. G., Elder, S. T., & Kubitz, K. A. (1987). A comparison of two methods of training resistance to visually-induced motion sickness. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 59(9), A34-A41.

Duller, P., & Gentry, W. D. (1980). Use of biofeedback in treating chronic hyperhidrosis: A preliminary report. The British Journal of Dermatology, 103(2), 143.

El-Kosery, S. M. A., Abd-El Raoof, N. A., & Farouk, A. (2005). Effects of biofeedback-assisted relaxation on preeclampsia. Bulletin of Faculty of Physical Therapy Cairo University, 10(2), 291-300.

El-Kosery, S. M. A., Saleh, A., & Farouk, A. (2005). Biofeedback-assisted relaxation and incidence of hypertension during pregnancy. Bulletin of Faculty of Physical Therapy Cairo University, 10(1), 221-230.

Fiero, P. L., Galper, D. I., Cox, D. J., Phillips, L. H., & Fryburg, D. A. (2003). Thermal biofeedback and lower extremity blood flow in adults with diabetes: Is neuropathy a limiting factor? Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 28(3), 193-203.

Fishman, T. D. (2004). Wound care information network.

Flor, H., Haag, G., Turk, D. C., & Koehler, H. (1983). Efficacy of EMG biofeedback, pseudotherapy, and conventional medical treatment for chronic rheumatic back pain. Pain, 17(1), 21-31.

Gao, L., Chen, J., Zhang, L., Wang, L., & Zhou, J. (2024). Rheumatoid arthritis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic advances. MedComm, 5(3), e509. https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.509

GBD 2021 Rheumatoid Arthritis Collaborators. (2023). Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatoid arthritis, 1990-2020, and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet Rheumatology, 5(10), e594-e610. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2665-9913(23)00211-4

Gevirtz, R. (2013). The promise of heart rate variability biofeedback: Evidence-based applications. Biofeedback, 41(3), 110-120.

Gevirtz, R. (2023). Functional/recurrent abdominal pain. In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Gitler, A., Vanmarcke, S., & Porges, S. W. (2025). Harnessing non-invasive vagal neuromodulation: HRV biofeedback and SSP for cardiovascular and autonomic regulation. Medical International, 5, Article 236. https://doi.org/10.3892/mi.2025.236

Graybiel, A., & Lackner, J. R. (1980). Evaluation of the relationship between motion sickness symptomatology and blood pressure, heart rate, and body temperature. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 51(3), 211-214.

Greenberger, N. J. (2013). Chronic and recurrent abdominal pain. The Merck Manual.

Greenberger, N. J. (2013). Nausea and vomiting. The Merck Manual.

Gwira, J. A., Fryar, C. D., & Gu, Q. (2024). Prevalence of total, diagnosed, and undiagnosed diabetes in adults: United States, August 2021-August 2023. NCHS Data Brief(516), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc/165794

Hall, J. E. (2016). Textbook of medical physiology (13th ed.). W. B. Saunders Company.

Huether, S. E., McCance, K. L., & Brashers, V. L. (2020). Understanding pathophysiology (7th ed.). Mosby.

Huang, H. Y. R., Wireko, A. A., Miteu, G. D., Khan, A., Roy, S., Ferreira, T., Garg, T., Aji, N., Haroon, F., Zakariya, F., Alshareefy, Y., Pujari, A. G., Madani, D., & Papadakis, M. (2024). Advancements and progress in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A review of pathophysiology and treatment. Medicine, 103(13), e37567. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000037567

Huang, K. Y., Wang, F. Y., Lv, M., Ma, X. X., Tang, X. D., & Lv, L. (2023). Irritable bowel syndrome: Epidemiology, overlap disorders, pathophysiology and treatment. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 29(26), 4120-4135. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i26.4120

Humphreys, P. A., & Gevirtz, R. N. (2000). Treatment of recurrent abdominal pain: Components analysis of four treatment protocols. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology & Nutrition, 31, 47-51.

Jozsvai, E. E., & Pigeau, R. A. (1996). The effect of autogenic training and biofeedback on motion sickness tolerance. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 67(10), 963-968.

Johnson, J. D., Louis, J. M., & Engstrom, J. L. (2022). Does race or ethnicity play a role in the origin, pathophysiology, and outcomes of preeclampsia? An expert review of the literature. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 226(2S), S876-S885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.07.038

Lamb, W. H. (2015). Pediatric Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. eMedicine.

Lavigne, J. V., Ross, C. K., Berry, S. L., Hayford, J. R., & Pachman, L. M. (1992). Evaluation of a psychological treatment package for treating pain in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care and Research, 5(2), 101-110.

Leahy, A., Clayman, C., Mason, I., Lloyd, G., & Epstein, O. (1998). Computerised biofeedback games: A new method for teaching stress management and its use in irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of London, 32(6), 552-556.

Lehrer, P., & Gevirtz, R. (2014). Heart rate variability biofeedback: How and why does it work? Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756

Lehrer, J. K. (2014). Irritable bowel syndrome. eMedicine.

Li, H. Z., Liang, X. Z., Sun, Y. Q., Jia, H. F., Li, J. C., & Li, G. (2024). Global, regional, and national burdens of osteoarthritis from 1990 to 2021: Findings from the 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study. Frontiers in Medicine, 11, 1476853. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1476853

Levy, R. A., Jones, D. R., & Carlson, E. H. (1981). Biofeedback rehabilitation of airsick aircrew. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 52(2), 118-121.

Lim, K.-H. (2014). Preeclampsia. eMedicine.

Little, B. C., Hayworth, J., Benson, P., Hall, F., Beard, R. W., Dewhurst, J., & Priest, R. G. (1984). Treatment of hypertension in pregnancy by relaxation and biofeedback. The Lancet, 323(8382), 865-867.

Liu, Y., Xu, F., Wang, Y., Wu, Q., Wang, B., Yao, Y., Zhang, Y., Han-Zhang, H., Wu, J., & Liang, L. (2024). A narrative review on the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(14), Article 7569. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25147569

Living well with diabetes. (2018). Harvard Health Publishing.

Long, H., Liu, Q., Yin, H., Wang, K., Diao, N., Zhang, Y., Lin, J., & Guo, A. (2022). Prevalence trends of site-specific osteoarthritis from 1990 to 2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 74(7), 1172-1183. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.42089

Lou, Z., & Bu, F. (2025). Recent advances in osteoarthritis research: A review of treatment strategies, mechanistic insights, and acupuncture. Medicine, 104(4), Article e41335. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000041335

Lozada, C. J. (2014). Osteoarthritis. eMedicine.

Masters, K. S. (2006). Recurrent abdominal pain, medical intervention, and biofeedback: What happened to the biopsychosocial model? Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 31(2), 155-165.

Mayer, E. A., Ryu, H. J., & Bhatt, R. R. (2023). The neurobiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Molecular Psychiatry, 28, 1451-1465. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-01972-w

McGrady, A., Kern-Buell, C., Bush, E., Devonshire, R., Claggett, A. L., & Grubb, B. P. (2003). Biofeedback-assisted relaxation therapy in neurocardiogenic syncope: A pilot study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 28(3), 183-192.

Moss, D., & Watkins, M. (2023). Irritable bowel syndrome. In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Mostafa, M. E. A., & Alrasheed, T. (2025). Improvement of irritable bowel syndrome with glucagon like peptide-1 receptor agonists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 16, Article 1548346. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2025.1548346

Osman, I. O., Gaafar, T. M., & Shaker, O. G. (2024). The pathophysiological, genetic, and hormonal changes in preeclampsia: A systematic review of the molecular mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(8), Article 4532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25084532

Palaniswamy, K. R. (2025). The microbiota-gut-brain axis in irritable bowel syndrome. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 13(2), 958-966. https://doi.org/10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20250216

Palumbo, P. J., & Melton, L. J. (1985). Diabetes in America: Diabetes data compiled in 1984. (NIH publication No. 851468). U.S. Government Printing Office.

Quan, D. (2014). Diabetic neuropathy. eMedicine.

Rhoades, R., & Bell, D. R. (Eds.). (2013). Medical physiology: Principles for clinical medicine (4th ed.). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

Rice, B., Kalker, A. J., Schindler, J. V., & Dixon, R. M. (2001). Effect of biofeedback-assisted relaxation training on foot ulcer healing. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association, 91(3), 132-141.

Rice, B. I., & Schindler, J. V. (1992). Effect of thermal biofeedback-assisted relaxation training on blood circulation in the lower extremities of a population with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 15(7), 853-858.

Rowe, V. L. (2014). Diabetic ulcers. eMedicine.

Russell, M. E., Hoffman, B., Stromberg, S., & Carlson, C. R. (2014). Use of controlled diaphragmatic breathing for the management of motion sickness in a virtual reality environment. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 39(3-4), 269-277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-014-9265-6

Schwartz, M. S., & Andrasik, F. (Eds.). (2003). Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Schwartz, R. A. (2014). Hyperhidrosis. eMedicine.

Schwartz, S. P., Taylor, A. C., Scharff, L., & Blanchard, E. B. (1990). Behaviorally treated irritable bowel syndrome patients: A four-year follow-up. Behavioral Research and Therapy, 28(4), 331-335.

Shaffer, F. (2023). Immune function. In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Shaffer, F. (2023). Preeclampsia. In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Shaffer, F., & Meehan, Z. M. (2016). Diabetic ulcers. In G. Tan, F. Shaffer, R. R. Lyle, & I. Teo (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (3rd ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Shaffer, F., & Meehan, Z. M. (2016). Intermittent claudication. In G. Tan, F. Shaffer, R. R. Lyle, & I. Teo (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (3rd ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Shaffer, F., & Meehan, Z. M. (2023). Motion sickness. In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Shaffer, F., & Schaff, B. (2023). Hyperhidrosis. In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Sharma, R., Steigerwald, S., Engstrom, J. L., Scott, K. A., Riis, V., Adams Waldorf, K. M., & Blue, N. R. (2021). Racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors and preeclampsia among women in the Boston Birth Cohort. JAMA Network Open, 4(12), e2139007. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.39007

Sherry, D. D. (2014). Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. eMedicine.