Respiratory Applications

What You Will Learn

Here's something that might surprise you: the advice to "take a deep breath" when you're stressed? It's often exactly wrong. This chapter will show you why—and teach you how biofeedback practitioners actually help people breathe better.

You'll explore respiratory biofeedback from assessment through intervention, discovering why checking a client's breathing matters even when they come in for something completely unrelated, like headaches or anxiety. You'll learn to spot dysfunctional breathing patterns (like overbreathing, where people exhale too much carbon dioxide) and understand why these patterns trigger such a wide range of symptoms. The chapter covers three major conditions: hyperventilation syndrome (which researchers now understand very differently than they did 20 years ago), asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Along the way, you'll encounter evidence-based protocols—including resonance frequency biofeedback—that can improve asthma outcomes while reducing medication dependence.

Why check breathing in every client, even those without respiratory complaints? Because how someone breathes affects everything else. Dysfunctional breathing patterns like overbreathing can stem from underlying medical disorders and contribute to symptoms ranging from dizziness and tingling to anxiety and chest pain. This interconnection between breathing and overall health makes physician collaboration essential—practitioners need to rule out medical causes before starting biofeedback training.

Think of healthy breathing as the foundation beneath all other biofeedback and neurofeedback work. If you don't address dysfunctional breathing first, interventions like heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback for asthma or neurofeedback for ADHD may hit a ceiling. The breathing problem becomes the limiting factor.

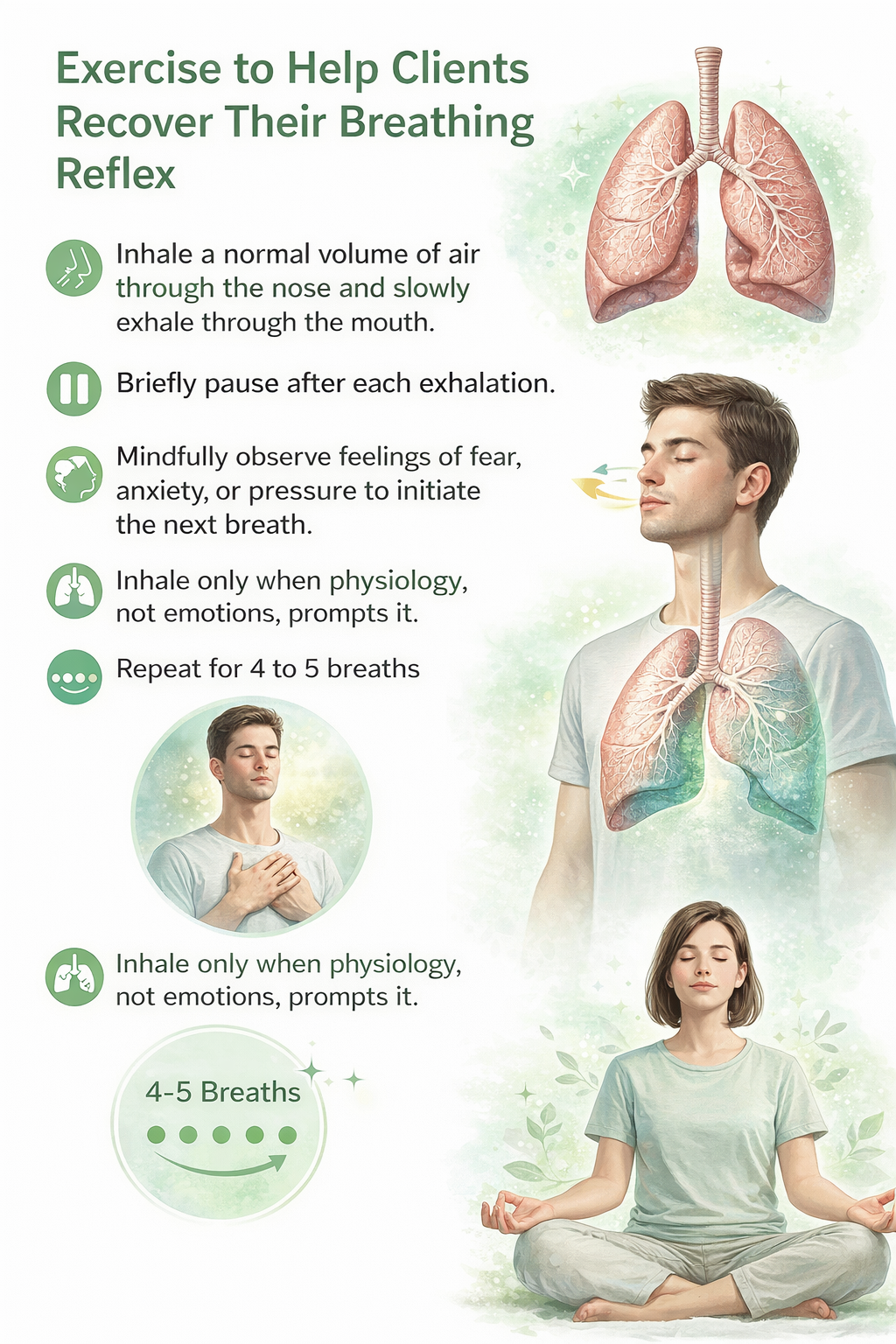

Clients often find the shift to healthy breathing surprisingly difficult. Why? Because dysfunctional breathing is typically overlearned—it's become automatic, wired into their chronic stress responses over months or years. For clients who overbreathe, there's an additional psychological hurdle: they may genuinely fear they aren't getting enough oxygen. Part of your job as a practitioner is providing reassurance while helping them recover their natural breathing reflex—the automatic signal that triggers the next breath when CO2 levels rise to the appropriate level.

The good news? Shifting to healthy breathing delivers immediate, tangible benefits. Clients experience increased ventilation (actually moving more air with less effort), improved acid-base balance (which means more glucose and oxygen reaching the brain and other organs), and vasodilation—widening of blood vessels in the hands and feet due to increased nitric oxide release. Over time, the practice of slow-paced breathing improves vagal tone (the activity level of the vagus nerve, which promotes rest-and-digest functions), restores a healthy respiratory sinus arrhythmia (the natural speeding and slowing of heart rate with breathing), and helps the body return to homeostasis.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses the Pathophysiology, biofeedback modalities, and treatment protocols for specific ANS biofeedback applications (IV-D).

This unit covers Breathing Assessment, Healthy Breathing, Hyperventilation Syndrome, Asthma, and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).

🎧 Listen to the Chapter Lecture (Part 1)

Breathing Assessment: The Foundation of Respiratory Biofeedback

Before you try to change someone's breathing, you need to understand why they're breathing that way in the first place. This is crucial for safety: overbreathing (when end-tidal CO2—the concentration of carbon dioxide in exhaled breath—falls below 33 mmHg) can be the body's way of compensating for serious medical problems like kidney disease. In these cases, attempting to "normalize" CO2 levels could actually be dangerous because it would reduce the body's ability to buffer excess acid. Medical investigation must come first.

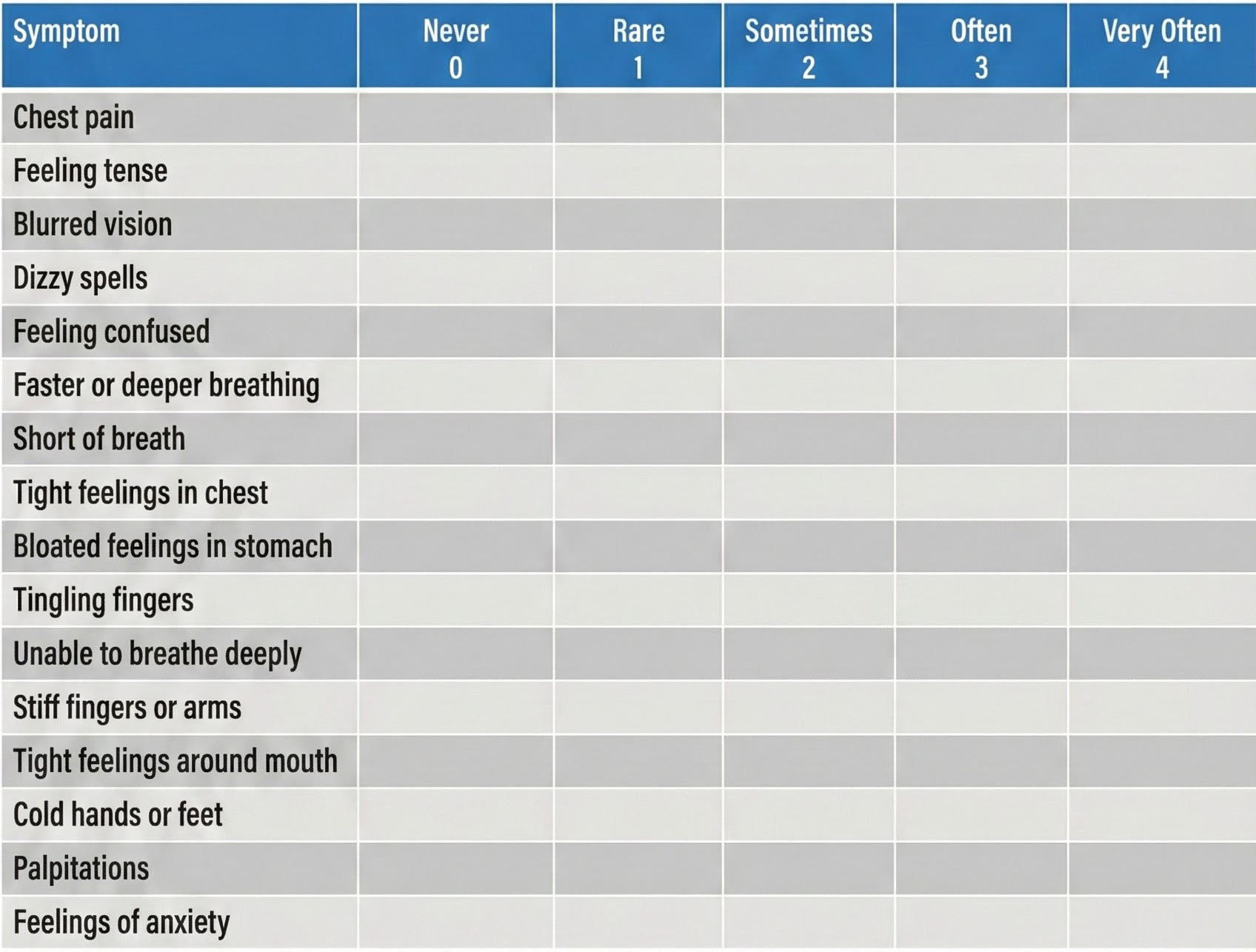

When overbreathing is suspected, practitioners often start with the Nijmegen Questionnaire (van Dixhoorn & Folgering, 2015). This validated screening tool asks about symptoms commonly produced by dysfunctional breathing—things like blurred vision, confusion, dizziness, and tingling sensations. A high score signals that breathing patterns deserve closer investigation.

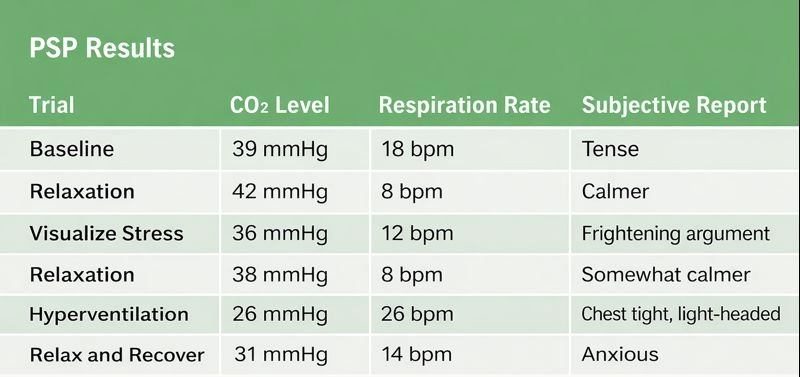

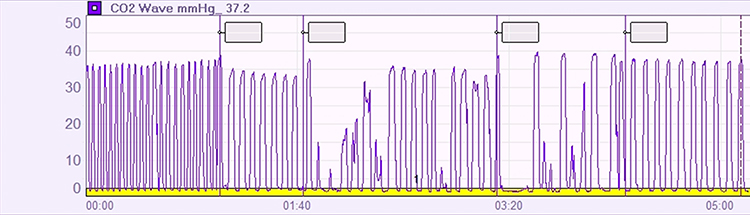

For comprehensive breathing assessment, clinicians can adapt the Psychophysiological Stress Profile (PSP) described in the Psychophysiology unit. The key addition is a capnometer—an instrument that measures the CO2 concentration in exhaled air by detecting how much infrared light the gas absorbs. With a capnometer, you're not just watching someone breathe; you're measuring the chemical consequences of their breathing pattern.

Conway (1994) proposed specific criteria for identifying clients who need breath training. According to these guidelines, a client should receive breathing intervention if they meet any of these three conditions: baseline end-tidal CO2 is at or below 30 mmHg (indicating chronic overbreathing), their end-tidal CO2 drops 20% or more during a stress or hyperventilation trial (showing stress-reactive breathing), or they fail to recover to within 80% of their baseline values during a recovery period (suggesting poor breathing regulation).

Important Cautions for Hyperventilation Screening

The hyperventilation trial—asking clients to breathe rapidly and shallowly on purpose—is a powerful assessment tool. It often produces visible physiological stress responses and frequently triggers symptoms the client recognizes, especially in those with anxiety disorders. There's clinical value in this: when clients feel their familiar symptoms emerge during the trial, they gain insight into the breathing-symptom connection.

However, deliberate hyperventilation is challenging both subjectively and medically. Screen patients carefully and skip the hyperventilation trial entirely for anyone with a history of pulmonary or heart disorders. Always instruct clients to stop the rapid breathing immediately if they experience discomfort (Moss & Shaffer, 2022). This is about safety first, assessment second.

Maria, a 53-year-old married woman, came in for treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. She hadn't left her home in seven weeks—not since losing her job. She described herself as inactive, depressed, and terrified at any suggestion of going outside. Her panic attacks brought rapid heart rate, chest tightness, dizziness, and overwhelming fears of dying. Even in the first interview, the clinician noticed something important: Maria was breath-holding and breathing shallowly. She also mentioned recurring migraines and gastroesophageal reflux disease.

During her physiological baseline, Maria breathed at a moderately rapid rate, but her CO2 levels appeared normal. She described herself as tense and anxious just being outside her home for the appointment. The assessment protocol moved through several phases: relaxation through slow breathing, visualization of a stressful situation, relaxation again, and then a hyperventilation stress trial followed by a 3-minute recovery period.

The visualization task—imagining a marital argument—produced only moderate changes in breathing rate and CO2. But the hyperventilation trial was different. Maria's CO2 dropped dramatically, and she suddenly exclaimed: "This is it; this is my attack, this is just what happens." She had just discovered that rapid, shallow breathing could reproduce her panic symptoms. During the recovery period, she couldn't calm herself down on her own—but when the therapist guided her moment-to-moment through paced diaphragmatic breathing, she recovered.

The assessment accomplished two crucial goals. First, it demonstrated the breathing-symptom connection in a way Maria could feel and understand. Second, it convinced her to commit to biofeedback-assisted breath training combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety. After 8 weeks of combined treatment, her panic attacks had nearly stopped completely.

Breathing assessment belongs in every stress profile—not just for clients with respiratory complaints. Why? Because dysfunctional breathing affects multiple body systems and can limit other interventions. Medical clearance is essential before attempting to normalize breathing in clients who may be hyperventilating to compensate for metabolic acidosis (an acid buildup that the body is trying to correct). The Nijmegen Questionnaire screens for dysfunctional breathing symptoms, while a psychophysiological stress profile with capnometry provides objective data. Conway's criteria—baseline CO2 ≤ 30 mmHg, 20%+ drop during stress, or failure to recover to 80% of baseline—identify clients who need breath training. Use hyperventilation trials cautiously, with appropriate cardiac and pulmonary screening.

Healthy Breathing: Challenging Common Misconceptions

The Myth of Needing More Oxygen

Here's a fact that surprises most people: at rest, you don't need more oxygen. At sea level, the air you inhale contains about 21% oxygen. The air you exhale? Still 15% oxygen. That means you only use about one-quarter of the oxygen you breathe in—there's plenty available. The real challenge isn't getting more oxygen into your body; it's conserving carbon dioxide. Healthy breathing retains 85-88% of CO2 volume (Khazan, 2021). This might seem backward—after all, isn't CO2 a waste product? Actually, your body needs CO2 to release oxygen from hemoglobin to your tissues (a phenomenon called the Bohr effect). Too little CO2 means your blood holds onto oxygen too tightly, starving your cells even while your oxygen saturation looks fine.

What Does Healthy Breathing Look Like?

Healthy breathing achieves a balance: your metabolic needs, CO2 production, breath depth, and breathing rate all match up appropriately. The goal is optimal breathing chemistry for each activity level. While rapid breathing doesn't always mean overbreathing and slow breathing doesn't always indicate health, the correlations are real (Khazan, 2021).

What does this look like in practice? Healthy breathing is mindful (attention resting on the abdomen), effortless (no strain or forcing), and slow—typically 5-7 breaths per minute at rest. External factors matter too: loose clothing that doesn't restrict the diaphragm, good posture that allows the ribcage to expand, and ergonomic setups that don't collapse the chest all support healthy breathing patterns.

🎧 Listen to the Chapter Lecture (Part 2)

Breathe Effortlessly, Not Deeply

The metaphor to share with clients: breathe like you're smelling a flower. Gentle. Effortless. Encourage breathing at a comfortable depth with an inhalation-to-exhalation ratio that features longer exhalations than inhalations (Peper & Tibbets, 1994). This pattern—easy breathing that satisfies but doesn't exceed the resting body's metabolic needs—is what produces calm (Khazan, 2021).

Here's where you need to help clients unlearn something: the typical "deep breath" people take when stressed is counterproductive. You know the pattern—someone inhales a massive breath and then inevitably exhales too quickly to get another big inhale. This common approach actually promotes overbreathing and expels too much CO2 (Khazan, 2021). For clients who've heard "just take a deep breath" their whole lives, this can be a surprising and important revelation.

Teaching Diaphragmatic Breathing

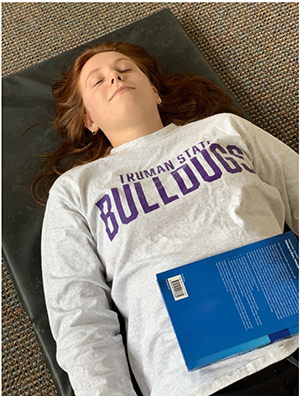

One of the simplest biofeedback tools costs nothing: a lightweight book. Have clients lie on the floor with knees bent and place a book on their abdomen. If the book rises during inhalation and falls during exhalation, they're breathing diaphragmatically. If their chest rises while the book stays still (or moves inward), they're breathing thoracically—using chest muscles instead of the diaphragm. The book provides immediate, visible feedback without any equipment.

Alternatively, clients can simply place their hands on their abdomens, feeling the rise and fall directly. This portable technique works anywhere and requires nothing except attention.

A word of caution: stick to lightweight books or simple awareness. Never encourage clients to use heavy weights on their abdomens—the safety risk and liability aren't worth it when lighter methods work just as well.

Helping Clients Recover Their Breathing Reflex

Normally, rising CO2 levels in the blood trigger the urge to take the next breath—this is the breathing reflex. But clients who overbreathe have essentially "hijacked" this system. They inhale before CO2 rises to its natural trigger point, driven by fear that they won't get enough oxygen or by an attempt to manage anxiety. The result: chronically low blood CO2 levels and all the symptoms that follow (Khazan, 2021).

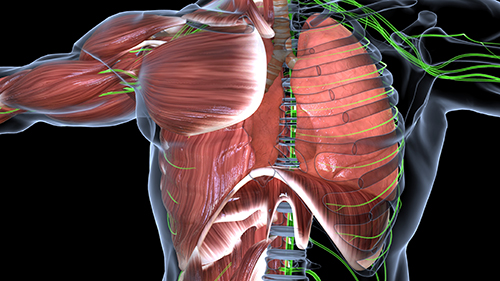

Most clients who overbreathe don't realize they're doing it—the pattern operates below conscious awareness. Your first task is helping them "tune into" their breathing. Many are thoracic breathers: they rely heavily on their external intercostal muscles (the muscles between the ribs) during inhalation, lifting the chest instead of letting the diaphragm—the dome-shaped muscle that should do about 75% of the work—descend and draw air into the lungs.

For clients who overbreathe, the shift to abdominal breathing is essential. When the diaphragm contracts and descends fully, it creates negative pressure that draws air deep into the lungs. Thoracic breathing—lifting the ribcage with intercostal muscles—is less efficient and often accompanies the shallow, rapid pattern that characterizes overbreathing.

Breathing Apps and Breath Pacers Support Practice

Between sessions, clients need to practice—and technology can help. Computer, tablet, and smartphone apps provide auditory or visual pacing that guides breathing rate. Try several apps yourself before recommending them; you're looking for adjustability (different rates for different clients) and ease of use (if it's confusing, clients won't use it). Computer options include Coherence Coach and EZ-Air Plus, and both Android and Apple platforms offer popular breathing apps.

The goal is eventual independence from the pacer. Assign practice with breathing pacers, then gradually fade their use as the healthy pattern becomes automatic. Free pacing tracks are available at Dr. Richard Gevirtz's Alliant University link.

Paced Breathing Demonstration

Dr. Inna Khazan demonstrates how paced and normal breathing can change low- and high-frequency power © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. You can enlarge the video by clicking on the bracket icon at the bottom right of the screen.

Monitoring and Discouraging Excessive Breathing Effort

Ironically, trying too hard to breathe "correctly" often makes things worse. Watch for these three red flags that signal effortful breathing:

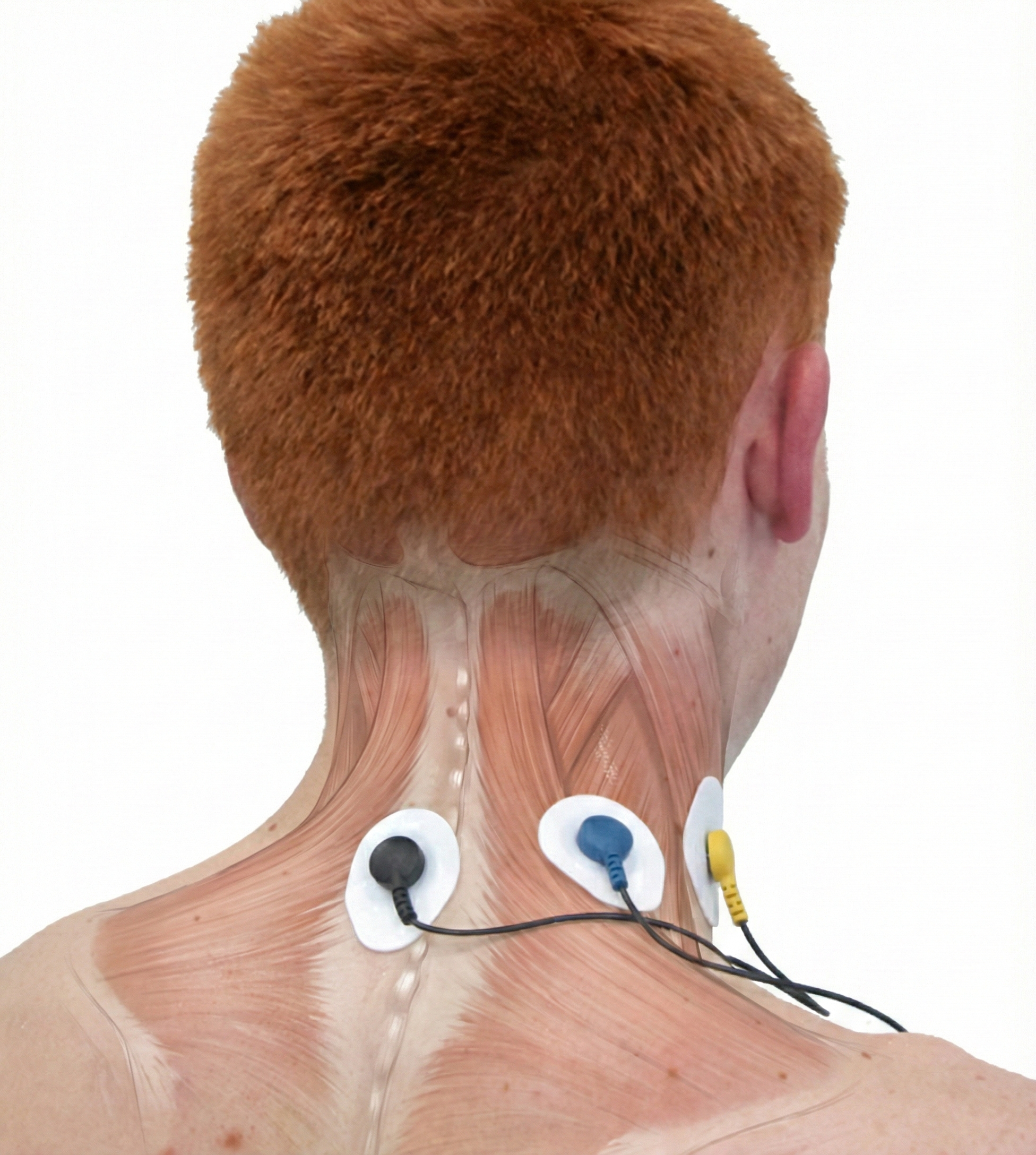

First, accessory muscle activity increases. The accessory muscles—sternocleidomastoid, pectoralis minor, scalene, and trapezius—are meant for forceful breathing, not relaxed respiration. When SEMG (surface electromyography) shows elevated activity in these muscles, your client is working too hard. A trapezius-scalene electrode placement is particularly sensitive to breathing effort.

A BioGraph ® Infiniti accessory muscle training screen can be used to correct clavicular breathing—a pattern where clients lift their collarbones during inhalation, recruiting neck muscles that shouldn't be involved in relaxed breathing.

Second, end-tidal CO2 often drops when clients try too hard. A capnometer will show values falling below the healthy threshold of 36 mmHg. Paradoxically, the harder they try to breathe "better," the more CO2 they blow off.

Third, the respirometer waveform loses its smoothness. Healthy, relaxed breathing produces gentle, rounded waves. When clients strain, the waveform becomes jagged and irregular.

The System-Wide Benefits of Healthy Breathing

Why does breathing matter so much in biofeedback? Because it's a master lever that influences multiple physiological systems simultaneously. When breathing normalizes, a cascade of beneficial changes follows.

The increased release of nitric oxide dilates arterioles (small arteries) in the hands and feet, which is why proper breathing supports hand-warming protocols. This vasodilation also means the body can deliver more oxygen and glucose to organs—especially the brain, which needs optimal fuel to support the self-regulation skills you're trying to teach.

The normalization of end-tidal CO2, combined with increased vagal tone and endogenous opioid release (your body's natural painkillers), helps buffer stress and calm clients. There's a specific threshold that matters: when respiration rate drops below 6 breaths per minute and end-tidal CO2 reaches 5% (36 mmHg), peripheral vasodilation occurs (Fried, 1990). This vasodilation is critical to treating conditions like hypertension, Raynaud's disease (where blood vessels in the fingers and toes overreact to cold), and vascular headaches.

Counter-intuitive as it sounds, healthy breathing is about conserving CO2, not maximizing oxygen intake. The goal: effortless breathing at 5-7 breaths per minute with longer exhalations than inhalations. Traditional "deep breathing" advice often backfires by expelling too much CO2. Three red flags signal excessive breathing effort: elevated accessory muscle activity (visible on SEMG), declining end-tidal CO2 (visible on capnometer), and jagged respirometer waveforms. Breathing apps and pacers support home practice, but should be faded as healthy patterns become automatic. The system-wide benefits—vasodilation, improved brain oxygenation, increased vagal tone—make breathing training foundational to all biofeedback work.

Check Your Understanding: Assessment and Healthy Breathing

- Why is medical clearance essential before attempting to normalize end-tidal CO2 levels in clients who overbreathe?

- What three indicators suggest that a client from Conway's (1994) protocol should receive breath training?

- Why does the common advice to "take a deep breath" often backfire for anxious clients?

- How can a simple book on the abdomen serve as a biofeedback device?

- What three "red flags" suggest a client is breathing with too much effort?

Hyperventilation Syndrome: A New Understanding

For decades, the standard explanation of hyperventilation syndrome (HVS) went like this: people breathe too fast and shallow, which blows off too much CO2, causing respiratory alkalosis (blood becomes too basic), which then produces symptoms like dizziness, tingling, and chest tightness. Treat the hyperventilation, and you treat the symptoms.

Recent research has challenged this model. Here's the problem: when researchers actually measured arterial CO2 levels in HVS patients during their attacks, many had normal CO2 levels (Kern, 2021). If low CO2 isn't always present during symptoms, it can't be the whole explanation.

The emerging view reconceptualizes HVS as a behavioral breathlessness syndrome in which hyperventilation is often the consequence rather than the cause of the disorder. Current evidence suggests symptoms may be triggered by factors beyond low CO2, including heightened interoceptive sensitivity—an excessive awareness of and reactivity to normal respiratory sensations—and anxiety-driven misinterpretation of ordinary breathing cues (Ruane et al., 2024). In other words, some patients don't have abnormal breathing; they have abnormal perception of normal breathing. Check out the YouTube video Breathing Pattern Disorders such as Hyperventilation for more on this topic.

Recognizing the Signs

Patients with acute HVS are typically agitated and anxious—visibly distressed. Both acute and chronic HVS patients describe a sudden onset of breathing difficulties: wheezing, chest pain, and palpitations that can persist for hours. Neurological symptoms are common too—dizziness, near-syncope or full syncope (fainting), paresthesias (tingling or "pins and needles" sensations), tetanic cramps (involuntary muscle contractions), and weakness. These symptoms often follow stressful situations (Kern, 2021).

The breathing pattern itself is distinctive: rapid, shallow, chest-based breathing punctuated with effortless sighs and gasps. Hyperventilators often display apnea (brief breath-holding) during activities you wouldn't expect to affect breathing—when surprised, writing checks, talking, or even just moving (Fried, 1990; Peper, 1989). These breath-holds are followed by compensatory deep breaths that perpetuate the cycle.

Who Is Affected?

Dysfunctional breathing (DB) is an umbrella term that encompasses HVS and other breathing pattern disorders. Current classification recognizes five subtypes: hyperventilation syndrome, periodic deep sighing, thoracic dominant breathing, forced abdominal expiration, and thoracoabdominal asynchrony (when chest and abdomen move in opposite directions during breathing) (Boulding et al., 2016).

The numbers are significant: dysfunctional breathing affects an estimated 6-10% of the general population. But among people with asthma, rates climb to 30%—and may reach a striking 47-64% in those with difficult-to-treat asthma (Ruane et al., 2024). Peak ages for HVS are between 15 and 55 years, with women affected far more often than men—the female-to-male ratio may reach 7:1.

It's important to distinguish HVS from panic disorder, even though symptoms overlap considerably. About 50% of patients diagnosed with panic disorder and 60% diagnosed with agoraphobia present with hyperventilation. However, only 25% of HVS patients are diagnosed with panic disorder (Kern, 2021)—the overlap is real but incomplete. Recent research has also identified HVS as a contributor to long-COVID symptoms; studies find elevated prevalence of dysfunctional breathing patterns among COVID-19 survivors, with patients showing delayed end-tidal CO2 recovery consistent with chronic hyperventilation even when their cardiopulmonary function appears normal (Ritter et al., 2024).

Do Not Rebreathe in a Paper Bag

You've seen it in movies: someone hyperventilating breathes into a paper bag to calm down. Don't recommend this—it's dangerous. Paper bag rebreathing can cause hypoxia (dangerously low oxygen levels) and has resulted in deaths when the patient was actually experiencing a heart attack, pneumothorax (collapsed lung), or pulmonary embolism (blood clot in the lung) rather than simple hyperventilation (Calaham, 1989). This is an important safety message that contradicts what clients may have learned from popular media.

Treatment Approach

Treatment starts with ruling out the dangerous stuff. Medical evaluation must exclude conditions like kidney disease or pulmonary embolism that can produce HVS symptoms. Once medical causes are cleared, treatment typically becomes multimodal.

Because HVS often involves psychological components, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) should be part of the intervention when assessment reveals psychological contributors. Lowering anxiety can reduce how often HVS symptoms occur (Gibson et al., 2007). This makes sense when you consider the vicious cycle at play: anxiety triggers hyperventilation, hyperventilation produces physical symptoms, symptoms increase anxiety, and the spiral continues.

Respiratory biofeedback using a capnometer and respirometer (a device that measures breathing rate and pattern) can help teach healthy breathing techniques (Fried, 1987; Khazan, 2021). The biofeedback display makes the invisible visible—clients can see exactly how their breathing affects their CO2 levels in real time.

Our understanding of hyperventilation syndrome has evolved substantially. The new "behavioral breathlessness syndrome" model recognizes that hyperventilation is often the consequence—not the cause—of symptoms. Supporting evidence: many HVS patients show normal CO2 levels during attacks. Mechanisms beyond low CO2 likely include heightened interoceptive sensitivity (overreacting to normal body sensations) and anxiety-driven misinterpretation of breathing cues. Dysfunctional breathing encompasses five subtypes, affecting 6-10% of the general population but reaching 47-64% in difficult-to-treat asthma. Critical safety point: never recommend paper bag rebreathing—it can cause hypoxia and death in patients with cardiac or pulmonary conditions. Effective treatment combines medical evaluation (to rule out dangerous causes), CBT (for the anxiety component), and respiratory biofeedback with capnometry (for objective feedback on breathing chemistry).

Check Your Understanding: Hyperventilation Syndrome

- How does the "behavioral breathlessness syndrome" reconceptualization change our understanding of HVS?

- What percentage of panic disorder patients also present with hyperventilation?

- Why is paper bag rebreathing dangerous, and what should be recommended instead?

Asthma: Beyond Medication with HRV Biofeedback

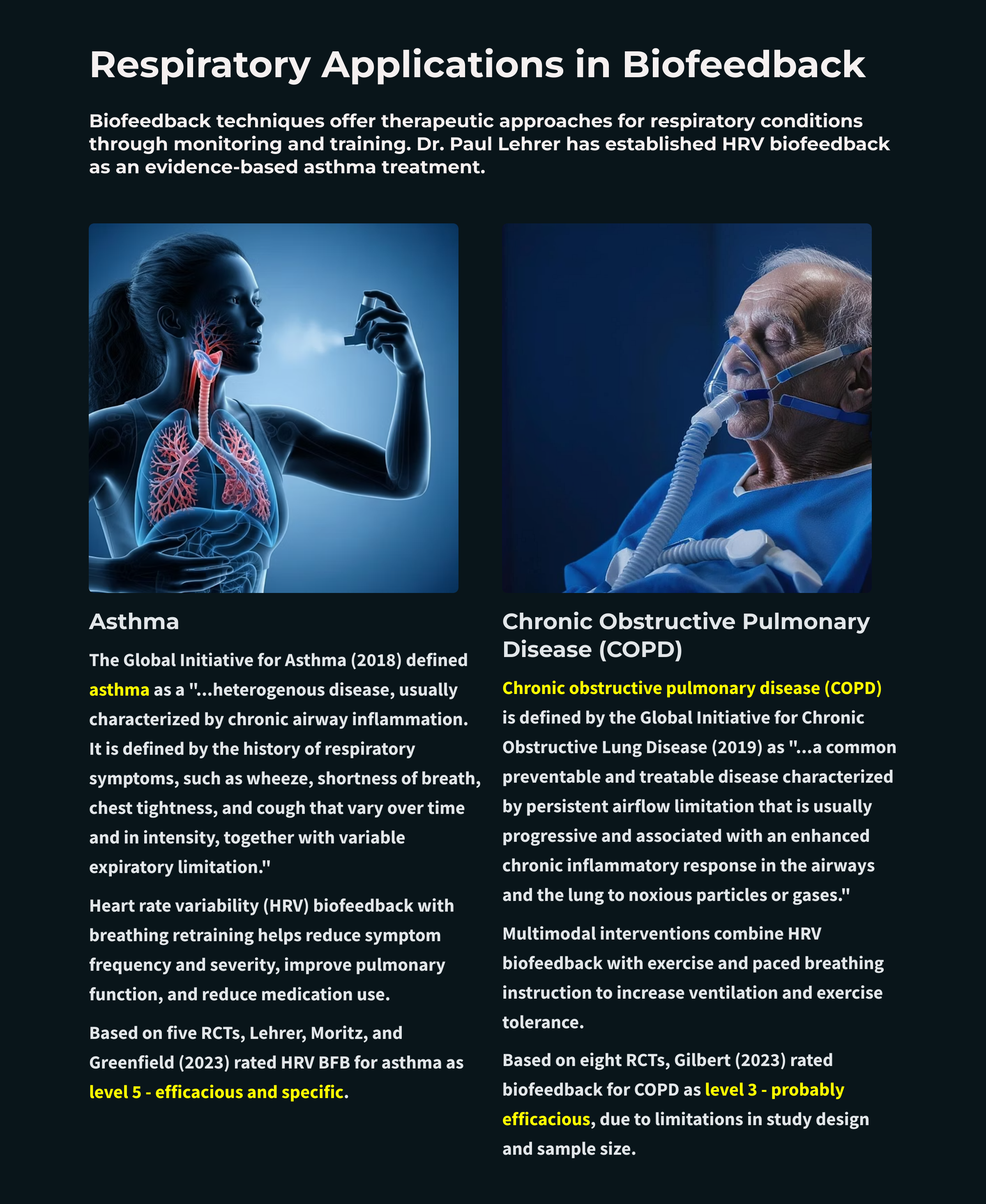

The Global Initiative for Asthma (2018) defined asthma as a "heterogenous disease, usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation." In practical terms, this means respiratory symptoms—wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough—that vary in intensity over time, along with reversible limitations in how much air can flow out of the lungs.

🎧 Listen to the Chapter Lecture (Part 3)

Here's what happens at the cellular level: the airway epithelium (the lining of the airways) releases signaling molecules called alarmins—including TSLP, IL-33, and IL-25—that kick off an inflammatory cascade affecting both structural and immune cells (Varricchi et al., 2024). This process involves T helper 2 (Th2) cells producing cytokines that drive eosinophilic inflammation (inflammation dominated by a type of white blood cell called eosinophils), mucus hypersecretion, and airway remodeling. Airway remodeling refers to structural changes—epithelial damage, smooth muscle thickening, subepithelial fibrosis (scarring beneath the airway lining)—that may become irreversible over time (Yamasaki, 2023). This is why early, effective asthma management matters: chronic inflammation can permanently alter airway structure. For visual explanations, check out the Nucleus Medical Media video Asthma at Health Journey Support and the Blausen Asthma animation.

How Common Is Asthma?

Multiple factors can trigger asthma attacks: allergens, pollution, infections, exercise, and medications like aspirin. But here's something important for biofeedback practitioners to understand—both acute and chronic stress can also precipitate attacks in children with asthma (Sandberg et al., 2000). This stress-asthma connection creates a clear opening for biofeedback intervention.

Recent surveillance data reveal the scope: approximately 25 million Americans currently have asthma—4.7 million children and 20.3 million adults (Pate & Zahran, 2024). That's roughly 1 in 13 people.

Interestingly, the pattern has shifted over the past decade. Among children, asthma prevalence has actually decreased significantly since 2010. Among adults, it has increased since 2013 (Pate & Zahran, 2024). Current estimates show 8.6% of adults and 6.5% of children have asthma (National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2025). Women are more affected than men (9.7% versus 6.2%), and significant racial disparities persist—non-Hispanic Black individuals show the highest prevalence at 11.1% (Pate & Zahran, 2024). Understanding these disparities matters for clinicians serving diverse populations.

Resonance Frequency Biofeedback Protocol

Heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback combined with breathing retraining has produced impressive results in asthma treatment: reduced symptom frequency and severity, improved pulmonary function, and decreased medication use. The key protocol was developed by Lehrer and colleagues (2000), combining resonance frequency HRV biofeedback with abdominal pursed-lips breathing.

What exactly is resonance frequency? Every oscillating system—including your cardiovascular system—has a frequency at which it responds most powerfully when stimulated. In HRV biofeedback, the resonance frequency is the breathing rate at which an individual's cardiovascular system produces the greatest respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA)—the natural acceleration of heart rate during inhalation and deceleration during exhalation. By breathing at this personalized rate (typically around 6 breaths per minute, though it varies between individuals), clients can maximize the training effect.

A systematic review of HRV biofeedback in chronic disease management confirmed significant positive effects on asthma without adverse effects. Improvements in symptoms co-occurred with enhanced autonomic function (Laborde et al., 2022)—suggesting the training doesn't just mask symptoms but actually improves underlying regulatory capacity.

What Does the Research Show?

The evidence base for HRV biofeedback in asthma has grown substantially. Lehrer and colleagues (1997) conducted a controlled study comparing three biofeedback approaches in adults with asthma: RSA biofeedback, neck/trapezius SEMG biofeedback, and incentive inspirometry biofeedback. Only the RSA biofeedback group showed large-scale within-session decreases in respiratory impedance. This finding is clinically important because pulmonary impedance—the resistance of the bronchioles to airflow—is exactly what you want to reduce in asthma.

Subsequent research expanded these findings. Kern-Buell and colleagues (2000) found that SEMG biofeedback might reduce inflammation and asthma symptoms. Lehrer, Smetankin, and Potapova (2000) reported that the Smetankin method of RSA biofeedback reduced both asthma symptoms and airway resistance in 20 unmedicated children—demonstrating effects without the confound of medication changes.

Song and Lehrer (2003) provided insight into optimal breathing rates. They instructed five female volunteers to breathe at rates of 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 breaths per minute while measuring HRV amplitude (peak-to-trough heart rate differences across the breathing cycle). The pattern was clear: slower breathing produced higher HRV amplitudes, with the peak occurring at 4 breaths per minute and declining slightly at 3 breaths per minute. This suggests there's a "sweet spot" for maximizing cardiovascular oscillation.

The largest clinical trial came from Lehrer and colleagues (2004), who examined HRV biofeedback in 94 adult asthma patients. After stabilizing all participants on controller medication, they randomly assigned patients to one of four conditions: HRV biofeedback with abdominal breathing training, HRV biofeedback alone, placebo EEG biofeedback, or a waiting list control.

The results? Both HRV groups required less steroid medication and showed better pulmonary function than controls. Notably, the two HRV groups didn't differ significantly from each other—suggesting that the HRV component, not the breathing training per se, drove the benefits. All groups showed reduced asthma symptoms and didn't differ in severe asthma flares. The authors concluded that HRV biofeedback shows promise as an adjunctive treatment that could reduce reliance on steroid medication.

What about systematic reviews? Yorke, Fleming, and Shuldham's (2007) Cochrane Systematic Review examined 15 studies involving 687 participants. While limited data prevented definitive conclusions about psychological interventions overall, one finding stood out: biofeedback significantly increased forced expiratory volume (FEV1)—the amount of air a person can forcefully exhale in one second, a key measure of lung function.

Meuret and colleagues (2007) took a different approach, using capnometric biofeedback to raise end-tidal pCO2 (partial pressure of CO2) while reducing respiration rate. This intervention decreased both the frequency and severity of asthma symptoms—consistent with the idea that normalizing breathing chemistry, not just rate, matters for outcomes.

Clinical Efficacy Rating

Based on five randomized controlled trials (RCTs), Paul Lehrer, Gali Moritz, and Naomi Greenfield rated HRV biofeedback for asthma as level 5: efficacious and specific in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). This is the highest rating on the efficacy scale, indicating that HRV biofeedback for asthma has been shown superior to credible sham therapy and equivalent or superior to established treatments in studies with adequate power. Participants improved in asthma severity and symptoms, pulmonary function, and medication use. One uncertainty remains: the impact of HRV biofeedback on airway inflammation is still unclear.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory condition affecting 25 million Americans—about 1 in 13 people. Stress can trigger attacks, creating a clear role for biofeedback intervention. Significant racial disparities persist, with non-Hispanic Black individuals showing the highest prevalence (11.1%). The standout finding: resonance frequency HRV biofeedback combined with abdominal pursed-lips breathing has earned a level 5 rating (efficacious and specific)—the highest possible—based on five RCTs. This means it's been shown superior to credible sham therapy. Clinical benefits include reduced medication dependence and improved pulmonary function.

Optimal breathing rates for maximizing HRV amplitude are typically 4-6 breaths per minute, though individual resonance frequencies vary. The key mechanism appears to be HRV training itself, not just breathing modification—the two HRV biofeedback groups in Lehrer's large trial didn't differ regardless of whether they also received breathing training.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is actually a family of lung diseases united by one feature: they all interfere with airflow. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (2019) defined it as "a common preventable and treatable disease characterized by persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response in the airways and the lung to noxious particles or gases."

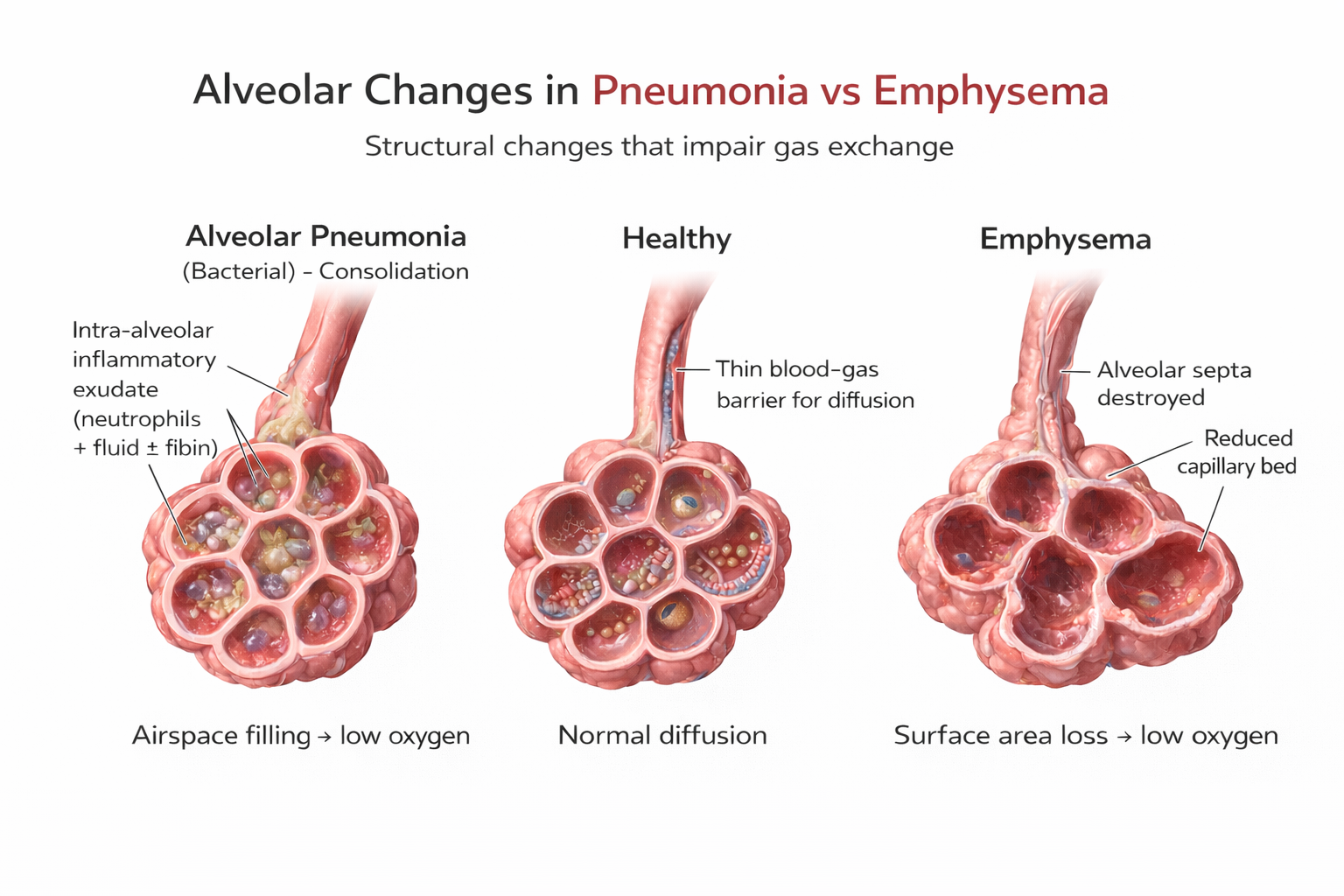

That last phrase—"noxious particles or gases"—points to the primary culprit: tobacco smoke. COPD is a progressive disorder with serious consequences. Almost 50% of severe cases die within 10 years of initial diagnosis. Two conditions comprise COPD: chronic obstructive bronchitis and emphysema. For visual explanations, check out the Nucleus Medical Media video Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease at Health Journey Support and the Blausen COPD animation.

Chronic bronchitis involves mucus hypersecretion and chronic productive cough—not just a week of coughing, but at least 3 months for a minimum of 2 consecutive years (Huether & McCance, 2020). The mucus literally clogs the airways.

Emphysema works differently. Here, the problem is structural damage to the alveoli—the tiny air sacs where gas exchange occurs. Abnormal, irreversible expansion of these gas-exchange airways accompanies destruction of alveolar walls (Huether & McCance, 2020). Unlike chronic bronchitis where mucus buildup causes obstruction, in emphysema it's inflammation and lung damage that produce the obstruction. The surviving air sacs are larger but less numerous and less effective—imagine trying to absorb oxygen through a few large balloons instead of millions of tiny ones.

Scope of the Problem

COPD represents a major public health burden—one of those conditions where the numbers alone tell a compelling story. According to recent National Health Interview Survey data, the age-adjusted prevalence of diagnosed COPD among U.S. adults is 3.8%, affecting approximately 16 million people (Manneh & Lucas, 2025).

The demographic patterns are notable: Women are more likely than men to have COPD (4.1% versus 3.4%)—possibly related to changing smoking patterns over recent decades. Prevalence increases dramatically with age, rising from just 0.4% among adults aged 18-24 to 10.5% among those 75 and older. This age gradient makes sense given COPD's progressive nature and the years of exposure typically required before symptoms emerge.

In 2023, COPD was the fifth leading cause of death in the United States, claiming 141,733 lives. The economic burden is staggering: annual medical costs reach an estimated $24 billion among adults 45 years and older (Manneh & Lucas, 2025). Racial disparities exist here too, though the pattern differs from asthma: White non-Hispanic adults show higher prevalence (4.4%) than Hispanic (2.0%) or Asian (1.0%) adults. COPD prevalence also tracks with socioeconomic factors—decreasing with higher family income and notably higher in rural communities where smoking rates tend to be elevated.

Multimodal Treatment Approach

COPD treatment requires combining multiple approaches—no single intervention is sufficient. Clinicians integrate HRV biofeedback with exercise and paced breathing instruction to increase ventilation and exercise tolerance. A network meta-analysis of breathing exercises for COPD found that various approaches improve exercise capacity, pulmonary function, and inspiratory muscle pressure, with diaphragmatic breathing and pursed-lip breathing showing particular benefits (Chen et al., 2023).

Esteve and colleagues (1996) demonstrated the potential of breathing pattern training: they randomly assigned COPD patients to either breathing training or a control group. The trained group showed remarkable improvements—FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in one second) increased by 22% and FVC (forced vital capacity)—the total amount of air a person can forcefully exhale—increased by 19%. The control group showed no improvement. These are clinically meaningful gains.

Giardino and colleagues (2004) took a comprehensive approach, combining HRV biofeedback with exercise in 10 COPD patients. Participants received five HRV biofeedback sessions to increase HRV, combined with paced breathing instruction. They also walked four times a week, using their paced respiration skills to control breathing, and monitored their oxygen levels with a pulse oximeter—a device that measures dissolved oxygen in the bloodstream using a light sensor placed on the finger. Results were encouraging: patients improved on the six-minute walking distance test (6MWD), which measures functional capacity, and the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), which assesses overall quality of life. Eight of the ten participants achieved clinically significant gains on these measures.

Emerging protocols now address a critical challenge: COPD patients often experience both dyspnea (shortness of breath) and anxiety simultaneously, each feeding the other. The Capnography-Assisted Learned Monitored (CALM) Breathing therapy uses end-tidal CO2 biofeedback combined with slow nasal breathing exercises to target dysfunctional breathing patterns in COPD patients. Pilot studies show participants report reduced dyspnea intensity, less avoidance of physical activity, and improved well-being (Norweg et al., 2024). By targeting both the physical and psychological components together, these protocols may reach patients who haven't responded to either approach alone.

Clinical Efficacy Rating

Based on eight RCTs, Christopher Gilbert (2023) rated biofeedback for COPD as level 3: probably efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). Why the lower rating compared to asthma (which earned level 5)? The COPD studies had limitations in design and sample size that prevented a higher classification. This doesn't mean the treatment doesn't work—it means we need more rigorous research to establish efficacy with greater certainty. For practitioners, level 3 suggests a reasonable evidence base for trying biofeedback with COPD patients, with appropriate informed consent about the current state of the evidence.

COPD—encompassing chronic bronchitis (mucus obstruction) and emphysema (alveolar destruction)—affects approximately 16 million Americans and ranks as the fifth leading cause of death. The condition hits hardest among older adults (10.5% prevalence in those 75+), women, and rural communities. Treatment requires a multimodal approach: HRV biofeedback combined with exercise and paced breathing instruction. The evidence is encouraging—breathing pattern training can increase FEV1 by 22% and FVC by 19%—but study limitations leave biofeedback for COPD rated at level 3 (probably efficacious), lower than asthma's level 5. Emerging protocols like CALM Breathing target both dyspnea and anxiety simultaneously, recognizing that these often feed each other in a vicious cycle. For practitioners, the takeaway: COPD patients can benefit from biofeedback, but expectations should be calibrated to the current evidence base.

Check Your Understanding: Asthma and COPD

- What is the resonance frequency and how is it used in asthma treatment?

- What level of evidence supports HRV biofeedback for asthma, and what outcomes does it improve?

- How do chronic bronchitis and emphysema differ in their mechanisms of airflow obstruction?

- Why is biofeedback for COPD rated lower (level 3) than for asthma (level 5)?

- What multimodal approach is recommended for COPD patients?

Cutting-Edge Topics in Respiratory Biofeedback

Remote HRV Biofeedback Delivery

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated development of remote HRV biofeedback interventions. A systematic review and meta-analysis of remote HRV biofeedback found medium effect sizes for improving both depression and HRV compared to control conditions (Wang et al., 2025). These findings support the feasibility of delivering respiratory biofeedback training through telehealth platforms and mobile applications, expanding access for patients who cannot attend in-person sessions.

Interoceptive Training for Dysfunctional Breathing

Emerging research recognizes interoceptive dysfunction—impaired processing of internal bodily signals—as a potential mechanism underlying dysfunctional breathing in conditions like COPD and anxiety disorders. New protocols combine capnography biofeedback with interoceptive awareness training to help patients recognize early physiological signs of breathing dysfunction before symptoms escalate. By targeting both the biomechanical and perceptual components of breathing, these approaches may improve outcomes for patients who have not responded to traditional breathing retraining alone (Norweg et al., 2024).

Slow-Paced Contraction Training: An Alternative to Breathing-Based HRV Biofeedback

Recent research has explored slow-paced contraction (SPC) training as an alternative pathway to increasing HRV for clients who struggle with breathing-based protocols. SPC involves rhythmic muscle contractions at approximately 6 cycles per minute, similar to resonance frequency breathing rates. Preliminary studies suggest this approach may produce comparable increases in HRV without requiring clients to modify their natural breathing patterns, making it potentially valuable for asthma and COPD patients for whom breathing modifications may be challenging or anxiety-provoking.

Wearable Technology and Real-Time Breathing Feedback

Advances in wearable respiratory monitors now allow continuous assessment of breathing patterns outside the clinic. Smart belts, chest straps, and smartphone-based algorithms can detect dysfunctional breathing patterns in real-time and provide immediate corrective feedback. Research is exploring whether these devices can improve treatment outcomes by extending biofeedback practice into daily life, though questions remain about accuracy compared to laboratory-grade equipment and optimal feedback delivery methods.

Test Yourself

Click on the ClassMarker logo to take 10-question tests over this unit without an exam password.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Visit the BioSource Software Website

BioSource Software offers Human Physiology, which satisfies BCIA's Human Anatomy and Physiology requirement, and Biofeedback100, which provides extensive multiple-choice testing over BCIA's Biofeedback Blueprint.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this module, put your knowledge into practice. Describe how you would assess breathing in a new client—what instruments would you use, what would you look for, and what criteria would indicate the need for breathing intervention? Explain how you would integrate breathing training with biofeedback for a client whose primary complaint is anxiety. Finally, share your favorite training techniques for helping clients shift from dysfunctional to healthy breathing patterns, and explain why you find them effective.

Glossary

accessory muscles: sternocleidomastoid, pectoralis minor, scalene, and trapezius muscles used during forceful breathing and in clavicular and thoracic breathing patterns.

airway remodeling: structural changes in the airways associated with chronic asthma, including epithelial damage, smooth muscle thickening, subepithelial fibrosis, and increased extracellular matrix deposition. These changes may become irreversible and contribute to persistent airflow limitation.

alarmins: epithelial cytokines (including TSLP, IL-33, and IL-25) released by airway epithelial cells in response to environmental insults that initiate inflammatory cascades in conditions like asthma.

asthma: episodic reversible airway obstruction, chronic airway inflammation, and hypersensitivity to stimuli like allergens, cold air, exercise, and viral infection. Chronic inflammation may scar the airway resulting in obstruction that does not reverse with medication.

behavioral breathlessness syndrome: the perspective that hyperventilation is the consequence and not the cause of the disorder. Emergency room data contradict the model that hyperventilation results in reduced arterial CO2 levels, since many HVS patients have normal arterial CO2 levels during attacks.

Bohr effect: elevated blood pH causes hemoglobin to tightly bind oxygen, slowing oxygen release to body tissues and reducing the partial pressure of oxygen (PO2).

breathing pattern disorders: subtypes of dysfunctional breathing classified as hyperventilation syndrome, periodic deep sighing, thoracic dominant breathing, forced abdominal expiration, and thoracoabdominal asynchrony. Different patterns may co-occur in the same patient and require targeted treatment approaches.

Capnography-Assisted Learned Monitored (CALM) Breathing: an emerging intervention for COPD that uses end-tidal CO2 biofeedback combined with slow nasal breathing exercises to target dysfunctional breathing patterns and interoceptive dysfunction, addressing both dyspnea and anxiety simultaneously.

capnometer: an instrument that monitors the carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration in an air sample (end-tidal CO2) by measuring the absorption of infrared light.

cardiovascular resonance frequency biofeedback: Lehrer and colleagues' Smetankin protocol combines HRV biofeedback with abdominal pursed-lips breathing. They train patients to breathe at their resonance frequency to increase HRV and treat disorders like asthma.

chronic bronchitis: a form of COPD involving mucus hypersecretion and chronic productive cough for at least 3 months for a minimum of 2 consecutive years.

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a progressive respiratory disorder mainly caused by smoking tobacco. Additional causes include cystic fibrosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, bronchiectasis (chronic abnormal bronchiole dilation), and rare bullous lung diseases featuring thin-walled sacs that contain air.

diaphragm: dome-shaped muscle whose contraction enlarges the chest cavity's vertical diameter and accounts for about 75% of air movement into the lungs during relaxed breathing.

dysfunctional breathing: an alteration in normal biomechanical patterns of breathing that results in intermittent or chronic respiratory and non-respiratory symptoms. Current classification identifies five subtypes: hyperventilation syndrome, periodic deep sighing, thoracic dominant breathing, forced abdominal expiration, and thoracoabdominal asynchrony. Prevalence ranges from 6-10% in the general population to 47-64% in difficult-to-treat asthma.

effortless breathing: Peper's relaxed breathing method in which the client uses about 70% of maximum effort, attention settles below the waist, and the volume of air moving through the lungs increases. The subjective experience is that "my body breathes itself."

emphysema: a form of COPD in which abnormal irreversible expansion of the gas-exchange airways is associated with alveolar wall damage. Unlike chronic bronchitis, inflammation and lung damage produce obstruction instead of mucus buildup.

end-tidal CO2: the percentage of CO2 in exhaled air at the end of exhalation.

high-frequency (HF) or respiratory band: the ECG frequency range from 0.15-0.40 Hz representing the inhibition and activation of the vagus nerves by breathing at average rates.

histamine: biogenic amine often released during allergic reactions to food, reducing blood oxygen saturation by constricting vessels and directly affecting red blood cell transport of oxygen. Histamine may cause hyperventilation.

hyperventilation syndrome (HVS): respiratory disorder increasingly reconceptualized as a behavioral breathlessness syndrome in which hyperventilation is the consequence and not the cause of the disorder.

interoceptive dysfunction: impaired processing of internal bodily signals that may contribute to dysfunctional breathing patterns. Patients may misinterpret normal respiratory sensations or fail to recognize early physiological signs of breathing dysfunction.

low-frequency (LF) band: the ECG frequency range of 0.05-0.15 Hz representing the influence of the parasympathetic branch and blood pressure regulation by baroreceptors.

metabolic acidosis: pH imbalance in which the body has accumulated excessive acid and has insufficient bicarbonate to neutralize its effects. In diabetes and kidney disease, hyperventilation is an attempt to compensate for abnormal acid-base balance, and slower breathing could endanger health.

modeling effect: phenomenon where a therapist's breathing behaviors influence patient breathing patterns.

Nijmegen Questionnaire: a validated questionnaire that assesses symptoms produced by dysfunctional breathing including blurred vision, confusion, and dizziness.

pulmonary impedance: resistance of the bronchioles of the lungs to airflow, which is increased in asthma.

pulse oximeter: a device that measures dissolved oxygen in the bloodstream using a photoplethysmograph sensor placed against a finger or earlobe.

rectus abdominis: muscle of forceful expiration that depresses the inferior ribs and compresses the abdominal viscera to push the diaphragm upward.

resonance frequency: the frequency at which a system like the cardiovascular system can be activated or stimulated to produce maximum oscillation. In breathing, this is the rate that maximizes time-domain measurements of heart rate variability.

respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA): heart rate acceleration during inspiration and deceleration during expiration.

reverse breathing: dysfunctional pattern where the abdomen expands during exhalation and contracts during inhalation, often resulting in incomplete ventilation of the lungs.

tidal volume: the volume of air moved in and out of lungs with each breath during ordinary effort.

torr: unit of atmospheric pressure named after Torricelli that equals a millimeter of mercury (mmHg) and is used to measure end-tidal CO2.

trapezius-scalene placement: SEMG electrode configuration with active electrodes located on the upper trapezius and scalene muscles to measure respiratory effort.

References

Allado, E., Poussel, M., Hamroun, A., Moussu, A., Kneizeh, G., Hily, O., Temperelli, M., Corradi, C., Koch, A., Albuisson, E., & Chenuel, B. (2022). Is there a relationship between hyperventilation syndrome and history of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection? A cross-sectional study. Healthcare, 10(11), 2154. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112154

Boulding, R., Stacey, R., Niven, R., & Fowler, S. J. (2016). Dysfunctional breathing: A review of the literature and proposal for classification. European Respiratory Review, 25(141), 287-294. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0088-2015

Callaham, M. (1989). Hypoxic hazards of traditional paper bag rebreathing in hyperventilating patients. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 18(6), 622-628. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(89)80515-3

Chen, Y., Ma, M., Chen, W., Jiang, X., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Effects of breathing exercises in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A network meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 104(12), 2114-2127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2023.04.024

Conway, A. (1994). Breathing and feeling: Capnometry and the individually meaningful psychological stressor. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 19(2), 135-139. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01776486

Cowan, M. J., Pike, K. C., & Budzynski, H. K. (2001). Psychosocial nursing therapy following sudden cardiac arrest: Impact on two-year survival. Nursing Research, 50, 68-76. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200103000-00002

Del Pozo, J., Gevirtz, R., Scher, B., & Guarneri, E. (2004). Biofeedback treatment increases heart rate variability in patients with known coronary artery disease. American Heart Journal, 147, E11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2003.08.013

Elliot, W. J., Izzo, J. L., Jr., White, W. B., Rosing, D. R., Snyder, C. S., Alter, A., Gavish, B., & Black, H. R. (2004). Graded blood pressure reduction in hypertensive outpatients associated with use of a device to assist with slow breathing. Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 6, 553-561. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.03553.x

Esteve, F., Blanc-Gras, N., Gallego, J., & Benechetrit, G. (1996). The effects of breathing pattern training on ventilatory function in patients with COPD. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 21(4), 311-321. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02214431

Fox, I., & Rompolski, K. (2022). Human physiology (16th ed.). McGraw Hill.

Fried, R. (1987). The hyperventilation syndrome: Research and clinical treatment. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fried, R. (1990). The breath connection: How to reduce psychosomatic and stress-related disorders with easy-to-do breathing exercises. Plenum Press.

Giardino, N. D., Chan, L., & Borson, S. (2004). Combined heart rate variability and pulse oximetry biofeedback for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Preliminary findings. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 29(2), 121-133. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:apbi.0000026638.64386.89

Gibson, D., Bruton, A., Lewith, G. T., & Mullee, M. (2007). Effects of acupuncture as a treatment for hyperventilation syndrome: A pilot, randomized crossover trial. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2006.5283

Gilbert, C. (2012). Pulse oximetry and breathing training. Biofeedback, 40(4), 137-141. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-40.4.04

Gilbert, C. (2023). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Global Initiative for Asthma. (2018). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. https://ginasthma.org/

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. (2019). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD 2019 report. https://goldcopd.org/

Grant, J., Wally, C., & Truitt, A. (2010). The effects of Kargyraa throat-singing and singing a fundamental note on heart rate variability [Abstract]. Poster presented at the meeting of the Biofeedback Foundation of Europe, Rome, Italy.

Hassett, A. L., Radvanski, D. C., Vaschillo, E. G., Vaschillo, B., Sigal, L. H., Karavidas, M. K., Buyske, S., & Lehrer, P. M. (2007). A pilot study of the efficacy of heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback in patients with fibromyalgia. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 32(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-006-9028-0

Huether, S. E., McCance, K. L., & Brashers, V. L. (2020). Understanding pathophysiology (7th ed.). Mosby.

Huikuri, H. V., & Makikallio, T. H. (2001). Heart rate variability in ischemic heart disease. Autonomic Neuroscience: Basic and Clinical, 90, 95-101.

Humphreys, P., & Gevirtz, R. (2000). Treatment of recurrent abdominal pain: Components analysis of four treatment protocols. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 31, 47-51. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005176-200007000-00011

Huntley, A., White, A. R., & Ernst, E. (2002). Relaxation therapies for asthma: A systematic review. Thorax, 57(2), 127-131. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.57.2.127

Jones, D., Fuller, J., Wally, C., Carrell, D., Peterson, J., Ward, A., Westermann-Long, A., Korenfeld, D., Burklund, Z., Shepherd, S., Francisco, A., Kane, A., & Zerr, C. (2012). Can Ujjayi breathing increase the effectiveness of 6-bpm heart rate variability training? [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 37(4), 297-298.

Kabins, A., Goedde, J., Layne, B., & Grant, J. (2008). Brief coaching increases inhalation volume [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 33(3), 174.

Karavidas, M. K., Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E. G., Vaschillo, B., Marin, H., Buyske, S., Malinovsky, I., Radvanski, D., & Hassett, A. (2007). Preliminary results of an open label study of heart rate variability biofeedback for the treatment of major depression. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 32, 19-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-006-9029-z

Kern, B. (2021). Hyperventilation syndrome treatment & management. eMedicine. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/807277-treatment

Kern-Buell, C. L., McGrady, A. V., Conran, P. B., & Nelson, L. A. (2000). Asthma severity, psychophysiological indicators of arousal, and immune function in asthma patients undergoing biofeedback-assisted relaxation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 25(2), 79-91. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009562708112

Khazan, I. (2021). Biofeedback and mindfulness in everyday life: Practical solutions for improving your health and performance. W. W. Norton & Company.

Kleiger, R. E., Miller, J. P., Bigger, J. T., Jr., & Moss, A. J. (1987). Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. American Journal of Cardiology, 59, 256-262. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9149(87)90795-8

Laborde, S., Allen, M. S., Borges, U., Hosang, T. J., Iskra, M., Mosley, E., Salvotti, C., Spolverato, L., Zammit, N., & Javelle, F. (2022). Heart rate variability biofeedback in chronic disease management: A systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 60, 102750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2021.102750

Lagos, L., Vaschillo, E., Vaschillo, B., Lehrer, P., Bates, M., & Pandina, R. (2011). Virtual reality-assisted heart rate variability biofeedback as a strategy to improve golf performance: A case study. Biofeedback, 39(1), 15-20. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-39.1.11

LaVaque, T. J., Hammond, D. C., Trudeau, D., Monastra, V., Perry, J., Lehrer, P., Matheson, D., & Sherman, R. (2002). Template for developing guidelines for the evaluation of the clinical efficacy of psychophysiological interventions. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 27(4), 273-281. https://dx.doi.org/10.1023%2FA%3A1021061318355

Lehrer, P. M. (2007). Biofeedback training to increase heart rate variability. In P. M. Lehrer, R. M. Woolfolk, & W. E. Sime (Eds.), Principles and practice of stress management (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Lehrer, P., Carr, R. E., Smetankine, A., Vaschillo, E., Peper, E., Porges, S., Edelberg, R., Hamer, R., & Hochron, S. (1997). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia versus neck/trapezius EMG and incentive inspirometry biofeedback for asthma: A pilot study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 22(2), 95-109. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1026224211993

Lehrer, P., Moritz, G., & Greenfield, N. (2023). Asthma. In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Lehrer, P., Smetankin, A., & Potapova, T. (2000). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback therapy for asthma: A report of 20 unmedicated pediatric cases using the Smetankin method. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 25(3), 193-200. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009506909815

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E., & Vaschillo, B. (2000). Resonant frequency biofeedback training to increase cardiac variability: Rationale and manual for training. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 25(3), 177-191.

Lehrer, P. M., Vaschillo, E., Vaschillo, B., Lu, S., Scardella, A., Siddique, M., & Habib, R. H. (2004). Biofeedback treatment for asthma. Chest, 126, 352-361. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.126.2.352

Lucini, D., Milani, R. V., Constantino, G., Lavie, C. J., Porta, A., & Pagani, M. (2002). Effects of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training on autonomic regulation in patients with coronary artery disease. American Heart Journal, 143, 977-983. https://doi.org/10.1067/mhj.2002.123117

Mancia, G., Ludbrook, J., Ferrari, A., Gregorini, L., & Zanchetti, A. (1978). Baroreceptor reflexes in human hypertension. Circulation Research, 43, 170-177. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.43.2.170

Manneh, C., & Lucas, J. W. (2025). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults in the United States, 2023 (NCHS Data Brief No. 529). National Center for Health Statistics. https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc/172232

McGrady, A., & Moss, D. (2013). Pathways to illness, pathways to health. Springer.

Meuret, A. E., Ritz, T., Wilhelm, F. H., & Roth, W. T. (2007). Targeting pCO2 in asthma: Pilot evaluation of capnometry-assisted breathing training. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 32(2), 99-109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-007-9037-6

Moss, D. (2004). Heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback. Psychophysiology Today, 1, 4-11.

Moss, D., & Shaffer, F. (2022). Foundations of heart rate variability biofeedback: A book of readings. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2025). FastStats: Asthma. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/asthma.htm

Norweg, A., Hofferber, B., Maguire, S., Oh, C., Raveis, V. H., & Simon, N. M. (2024). Breathing on the mind: Treating dyspnea and anxiety symptoms with biofeedback in chronic lung disease—A qualitative analysis. Respiratory Medicine, 221, 107505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2023.107505

Pate, C. A., & Zahran, H. S. (2024). The status of asthma in the United States. Preventing Chronic Disease, 21, E53. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd21.240005

Peper, E. (1989). Breathing for health with biofeedback. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual Meeting of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 117-122.

Peper, E., Gibney, K. H., Tylova, H., Harvey, R., & Combatalade, D. (2008). Biofeedback mastery: An experiential teaching and self-training manual. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Peper, E., & Tibbetts, V. (1992). Fifteen-month follow-up with asthmatics utilizing EMG/incentive inspirometer feedback. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 17(2), 143-151. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01000104

Peper, E., & Tibbetts, V. (1994). Effortless diaphragmatic breathing. Physical Therapy Products, 6(2), 67-71.

Ritter, O., Noureddine, S., Laurent, L., Roux, P., Westeel, V., & Barnig, C. (2024). Unraveling persistent dyspnea after mild COVID: Insights from a case series on hyperventilation provocation tests. Frontiers in Physiology, 15, 1394642. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2024.1394642

Ruane, L. E., Denton, E., Bardin, P. G., & Leong, P. (2024). Dysfunctional breathing or breathing pattern disorder: New perspectives on a common but clandestine cause of breathlessness. Respirology, 29(10), 863-866. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.14807

Sandberg, S., Paton, J. Y., Ahola, S., McCann, D. C., McGuinness, D., Hillary, C. R., & Oja, H. (2000). The role of acute and chronic stress in asthma attacks in children. Lancet, 356, 982-987. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02715-x

Schwartz, M. S., & Andrasik, F. (Eds.). (2003). Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Shaffer, F., & Moss, D. (2006). Biofeedback. In Y. Chun-Su, E. J. Bieber, & B. Bauer (Eds.), Textbook of complementary and alternative medicine (2nd ed.). Informa Healthcare.

Song, H., & Lehrer, P. M. (2003). The effects of specific respiratory rates on heart rate and heart rate variability. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 28(1), 13-23. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022312815649

Stein, P. K., Ehsani, A. A., Domitrovich, P. P., Kleiger, R. E., & Rottman, J. N. (1999). Effect of exercise training on heart rate variability in healthy older adults. American Heart Journal, 138(3 Pt 1), 567-576. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70162-6

Swanson, K. S., Gevirtz, R. N., Brown, M., Spira, J., Guarneri, E., & Stoletniy, L. (2009). The effect of biofeedback on function in patients with heart failure. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 34(2), 71-91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-009-9077-2

Tan, G., Dao, T. K., Farmer, L., Sutherland, R. J., & Gevirtz, R. (2010). Heart rate variability (HRV) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A pilot study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-010-9141-y

Tortora, G. J., & Derrickson, B. H. (2021). Principles of anatomy and physiology (16th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

van Dixhoorn, J., & Folgering, H. (2015). The Nijmegen Questionnaire and dysfunctional breathing. ERJ Open Research, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00001-2015

Varricchi, G., Brightling, C. E., Grainge, C., Lambrecht, B. N., & Chanez, P. (2024). Airway remodelling in asthma and the epithelium: On the edge of a new era. European Respiratory Journal, 63(4), 2301619. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01619-2023

Wang, D., Deng, X., Jing, N., & Li, S. (2025). Efficacy and methodology of remote heart rate variability biofeedback interventions for mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-025-09750-w

Weil, C. M., Wade, S. L., Bauman, L. J., Lynn, H., Mitchell, H., & LaVigne, J. (1999). The relationship between psychosocial factors and asthma morbidity in inner-city children with asthma. Pediatrics, 104, 1274-1280. https://doi.org/10.1542/PEDS.104.6.1274

Wheat, A. L., & Larkin, K. T. (2010). Biofeedback of heart rate variability and related physiology: A critical review. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 35(3), 229-242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-010-9133-y

Wise, R. A. (2014). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The Merck manual. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pulmonary-disorders/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-and-related-disorders/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd

Yamasaki, A. (2023). Editorial: Airway remodeling in asthma—What is new? Frontiers in Allergy, 4, 1129840. https://doi.org/10.3389/falgy.2023.1129840

Yorke, J., Fleming, S. L., & Shuldham, C. M. (2006). Psychological interventions for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1), CD002982. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd002982.pub3

Zucker, Y. L., Samuelson, K. W., Muench, F., Greenberg, M. A., & Gevirtz, R. N. (2009). The effects of respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback on heart rate variability and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: A pilot study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 34(3), 135-143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-009-9085-2