Concepts in Biofeedback

What You Will Learn in This Chapter

Have you ever wondered how some people seem to stay calm under pressure while others fall apart? Or why your hands get cold when you are nervous? This chapter pulls back the curtain on biofeedback, a fascinating approach that gives you a window into your body's hidden workings and teaches you to take control of processes you never knew you could influence.

We will explore how biofeedback works as a learning process (spoiler: it is more like learning to play guitar than taking a pill), discover the major tools clinicians use, and uncover why your relationship with your therapist might matter more than the fancy equipment. Along the way, we will examine six different ways experts have tried to explain what biofeedback actually does, dig into the memory systems that make skill learning possible, and identify what separates effective training from wasted time. By the end, you will understand why thinking of biofeedback as "body coaching" makes a lot more sense than thinking of it as treatment.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage: This unit addresses Definitions of Biofeedback (I-A), Concepts of Feedback and Control in Biological Systems (I-C), and Overview of Principles of Human Learning as They Apply to Biofeedback (I-D).

Understanding Biofeedback as a Learning Process

Think about the last time you learned something new, maybe a musical instrument, a video game, or a sport. You tried something, watched what happened, adjusted your approach, and tried again. That cycle of action, observation, and refinement is exactly what biofeedback is all about. The difference? Instead of watching a ball land in or out of bounds, you are watching your own heart rhythm, muscle tension, or brain waves on a screen.

Picture a client named Marcus sitting in a comfortable chair, breathing slowly while watching a display of his heart rate variability. He notices that when he breathes out for a count of six, the rhythmic patterns on the screen become smoother and more pronounced. He experiments with different breathing depths and tempos, watching the display respond in real time. Over the next few weeks, Marcus learns to reproduce this calm, rhythmic breathing pattern automatically, whether he is stuck in traffic or walking into a tense meeting with his boss.

Peper, Shumay, and Moss (2012) call biofeedback a "psychophysiological mirror." Just like you use a bathroom mirror to check if your hair looks okay or your tie is straight, biofeedback lets you see what is happening inside your body so you can make adjustments. Without that mirror, you would never know your shoulders were creeping up toward your ears or that you were holding your breath during stressful emails.

The Real Goal: Flying Solo

Here is something that surprises many people: the ultimate goal of biofeedback is to make the equipment unnecessary. We call this self-regulation, meaning you can control your body without any external feedback or reminders. Think of training wheels on a bicycle. They are incredibly helpful when you are learning, but success means riding without them. Similarly, a client might use a posture sensor that buzzes when they slouch. When they can sit up straight all day without any buzzing reminders, they have achieved self-regulation. The biofeedback served its purpose as a bridge to get them there.

More Than Just Clinical Treatment

While biofeedback started as a way to help people with health problems, it has grown far beyond the clinic. Professional athletes use heart rate variability training to optimize their recovery and stay cool under championship pressure. Concert pianists practice finger temperature warming to combat the cold hands that come with stage fright. CEOs learn to recognize and interrupt their stress responses before walking into high-stakes board meetings. A Navy SEAL preparing for a dangerous mission and a college student preparing for the GRE might both benefit from the same basic skills.

Check Your Understanding

- Why do Peper, Shumay, and Moss describe biofeedback as a "psychophysiological mirror"? What does this metaphor help you understand about how biofeedback works?

- What is self-regulation, and why is it considered the ultimate goal of biofeedback training rather than just an intermediate step?

- How does the training wheels analogy help explain the relationship between biofeedback equipment and the skills clients learn?

- Give two examples of how biofeedback is used outside of clinical treatment for health problems.

Why Mindfulness Makes Biofeedback Work Better

Imagine trying to adjust the temperature in your shower while wearing thick winter gloves. You could not feel the subtle changes, so you would keep overshooting, going from scalding to freezing and back again. That is what biofeedback training is like without mindfulness. You need to actually notice what is happening in your body to make useful adjustments.

Jon Kabat-Zinn (1994) defined mindfulness as "paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally." That last part is crucial. If you are beating yourself up every time your heart rate spikes on the display ("I'm so bad at this! Why can't I relax?"), you are creating exactly the stress response you are trying to reduce. Mindfulness means noticing what is happening with curiosity rather than criticism.

Here is a sobering statistic: research suggests that mind-wandering hijacks somewhere between 30% and 50% of our daily thoughts (Turkelson & Mano, 2021). That is a lot of time spent on mental autopilot, missing what is actually happening right now. Mindfulness training helps clients stay present during biofeedback sessions so they can actually learn from the feedback they are receiving.

Jane came to biofeedback training after her doctor diagnosed elevated blood pressure. Determined to get it under control, she bought a home blood pressure monitor and started checking several times a day. But here is what happened: every time she wrapped that cuff around her arm, she got anxious about what the numbers would show. Her anxious anticipation actually raised her blood pressure, which made her more anxious, which raised it further. She was stuck in a vicious cycle, and she could not focus on her breathing exercises because she was too busy worrying about her readings.

Everything changed when Jane learned to approach her blood pressure with acceptance rather than fear. She cut back to measuring once a day and stopped treating each reading like a pass/fail test. Instead of fighting against her hypertension, she focused on the one thing she could actually control: her breathing pattern. Within a few months, her blood pressure dropped significantly. The irony? She succeeded by stopping the struggle and accepting where she was.

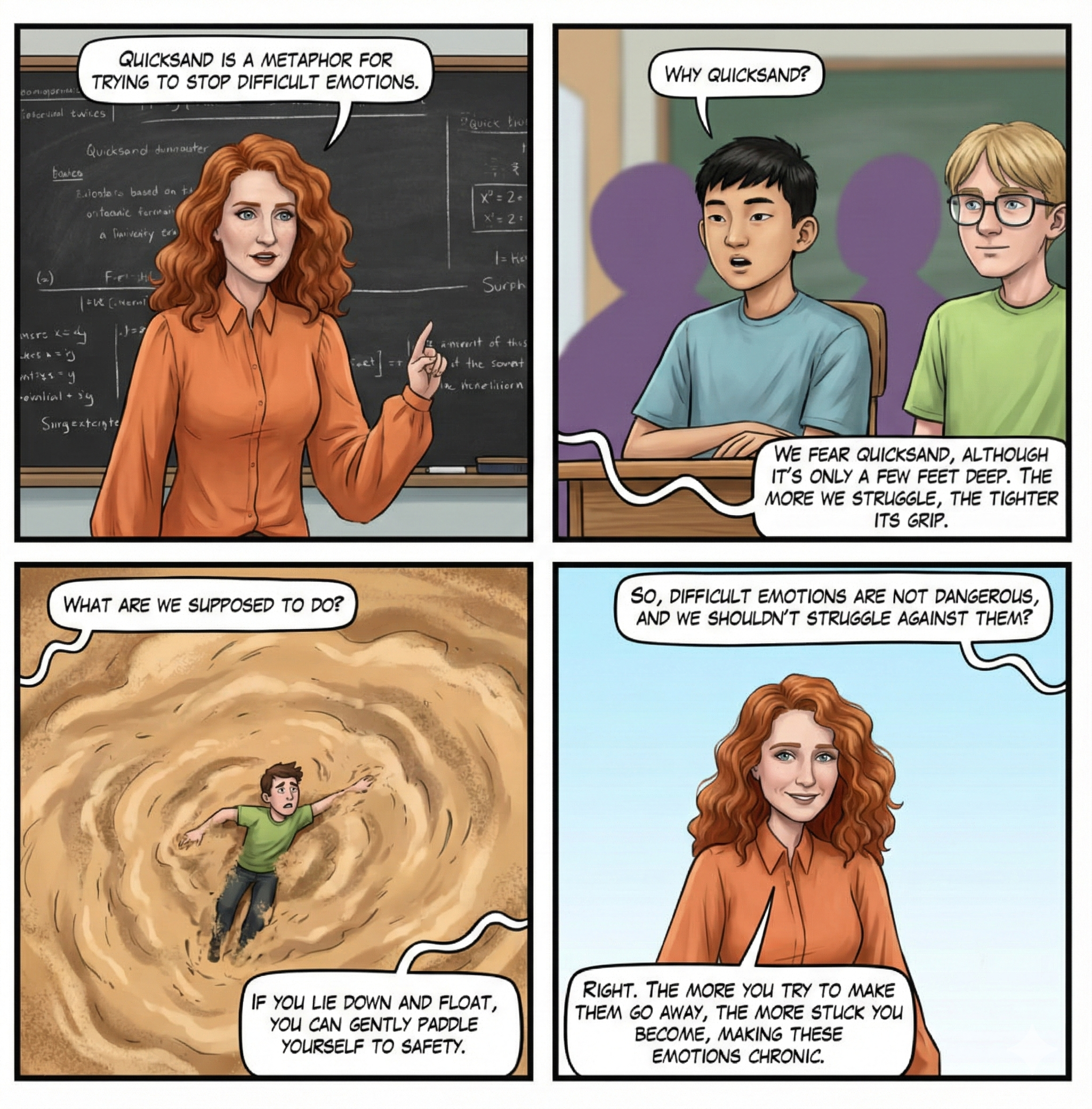

Dr. Inna Khazan (2019) uses a vivid metaphor to explain this principle: quicksand. If you have ever seen a movie where someone steps into quicksand, you know that thrashing around makes you sink faster. The counterintuitive solution is to relax, spread your weight, and move slowly. Emotions work similarly. When you desperately fight against anxiety or pain, you often intensify those very experiences. Accepting uncomfortable sensations while taking constructive action (like practicing slow breathing) tends to work better than direct combat.

Connecting Body, Mind, and Something More

If you have ever had a conversation with someone who was technically saying helpful things but clearly did not care about you as a person, you know that health is about more than just physical measurements. The best biofeedback practitioners recognize that their clients are whole people with beliefs, values, and a need for meaning, not just collections of physiological variables to be optimized.

Check Your Understanding

- Kabat-Zinn's definition of mindfulness includes the word "nonjudgmentally." Why is this aspect particularly important during biofeedback training?

- Explain the quicksand metaphor. How does it apply to a client who is anxious about their anxiety?

- In Jane's case, what changed that allowed her blood pressure to improve? What was she doing wrong initially?

- Why might a biofeedback therapist need to consider a client's beliefs and sense of meaning, not just their physiological measurements?

When Biofeedback Does Not Work

Let us be honest: biofeedback is not magic, and it does not work for everyone or every condition. Experienced clinicians will tell you they learn as much from their failures as from their successes. Dr. Saul Rosenthal even organized a professional symposium with the refreshingly honest title "Crappy Cases: Should I Zig, Zag, or Drive Off the Cliff?" to help practitioners learn from treatments that did not go as planned.

A Remarkable Story of Self-Healing

Scott Adams, the creator of the Dilbert comic strip, faced a terrifying challenge. He developed spasmodic dysphonia, a condition where abnormal muscle contractions in the larynx made it impossible for him to speak normally in person. Imagine being unable to have a simple conversation with a friend or colleague. The cause of spasmodic dysphonia remains unknown, spontaneous recovery is rare, and conventional treatments like Botox injections and speech therapy can reduce symptoms but do not cure the condition (Bliznikas & Baredes, 2005).

Adams refused to accept this as permanent. He threw everything he could think of at the problem: visualization, hypnosis, affirmations, speech therapy exercises, singing his words, speaking in foreign accents, changing his pitch. He paid close attention to what worked and what did not, constantly looking for patterns. Then he stumbled onto something unexpected: he could speak normally when he spoke in rhyme. He practiced this obsessively for several days, and gradually, his normal speech returned.

What makes Adams' story relevant to biofeedback? Look at what he did: he tried self-regulation exercises, he used feedback (his own voice) to know if strategies were working, he monitored himself carefully, and he practiced relentlessly. These are exactly the elements of Shellenberger and Green's (1986) mastery model of biofeedback. Adams essentially did biofeedback training on himself, without any fancy equipment, and retrained his neuromuscular system through sheer persistence and careful observation.

This is perhaps the most important insight of this chapter: biofeedback is defined by the learning process, not by specific equipment. Training can involve sophisticated computerized systems, simple handheld devices, or no technology at all. What matters is the cycle of action, feedback, and adjustment that leads to self-regulation.

Check Your Understanding

- Why is it valuable for professionals to openly discuss cases that did not go well, as Dr. Rosenthal's symposium encouraged?

- What is spasmodic dysphonia, and why was Scott Adams' recovery considered remarkable?

- Identify at least three elements of Adams' self-treatment that parallel formal biofeedback training.

- Based on Adams' story, explain why biofeedback is defined by the learning process rather than by specific equipment.

What Exactly Is Biofeedback? The Official Definitions

🎧 Listen to Mini-Lecture on Biofeedback Therapy

The Biofeedback Alliance Definition (2008)

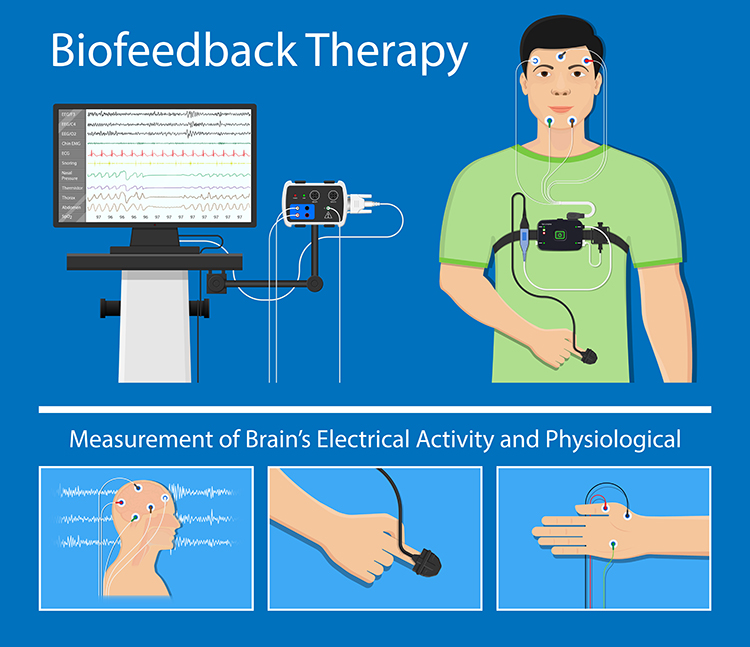

Biofeedback is a process that enables an individual to learn how to change physiological activity for the purposes of improving health and performance. Precise instruments measure physiological activity such as brainwaves, heart function, breathing, muscle activity, and skin temperature. These instruments rapidly and accurately "feed back" information to the user. The presentation of this information—often in conjunction with changes in thinking, emotions, and behavior—supports desired physiological changes. Over time, these changes can endure without continued use of an instrument.

Let us unpack this definition piece by piece. First, biofeedback is a learning process that teaches you to control physiological activity. It is not something done to you; it is something you learn to do. Second, the goal is practical: better health and performance. Third, the instruments need to be fast enough that you can connect your actions to their effects. If there is a 30-second delay between changing your breathing and seeing the result, learning becomes nearly impossible. Fourth, you use this feedback to figure out how to produce the changes you want. Fifth, the physical changes usually come along with mental and emotional shifts, and these reinforce each other. Finally, and this is crucial, you eventually become able to produce these changes without any equipment at all.

The ISNR Definition of Neurofeedback (2010)

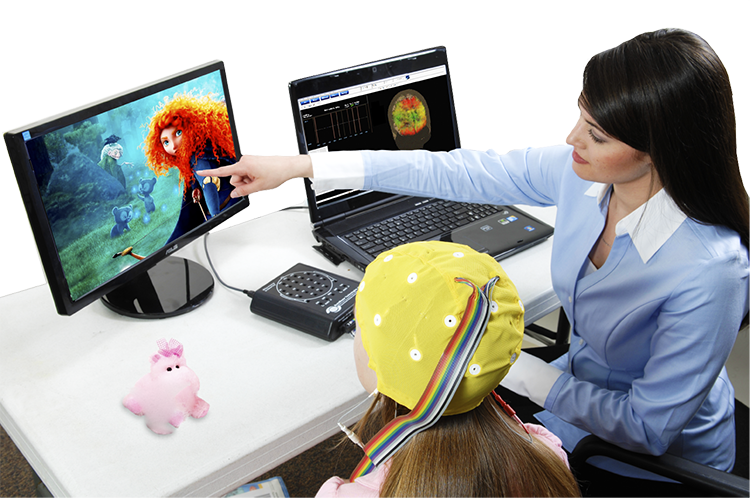

Neurofeedback is biofeedback focused specifically on the brain. Instead of monitoring heart rate or muscle tension, you are monitoring electrical activity in the brain itself.

Like other forms of biofeedback, NFT uses monitoring devices to provide moment-to-moment information to an individual on the state of their physiological functioning. The characteristic that distinguishes NFT from other biofeedback is a focus on the central nervous system and the brain.

The International Society for Neurofeedback and Research emphasizes that neurofeedback is a "self-regulation method." This distinction matters because it separates neurofeedback from approaches that simply zap your brain with stimulation and hope for the best. Techniques like audio-visual entrainment, where flashing lights and pulsing sounds try to push your brain into different states, might have value, but they are not neurofeedback because they do not involve learning. You are not developing a skill; you are just being stimulated.

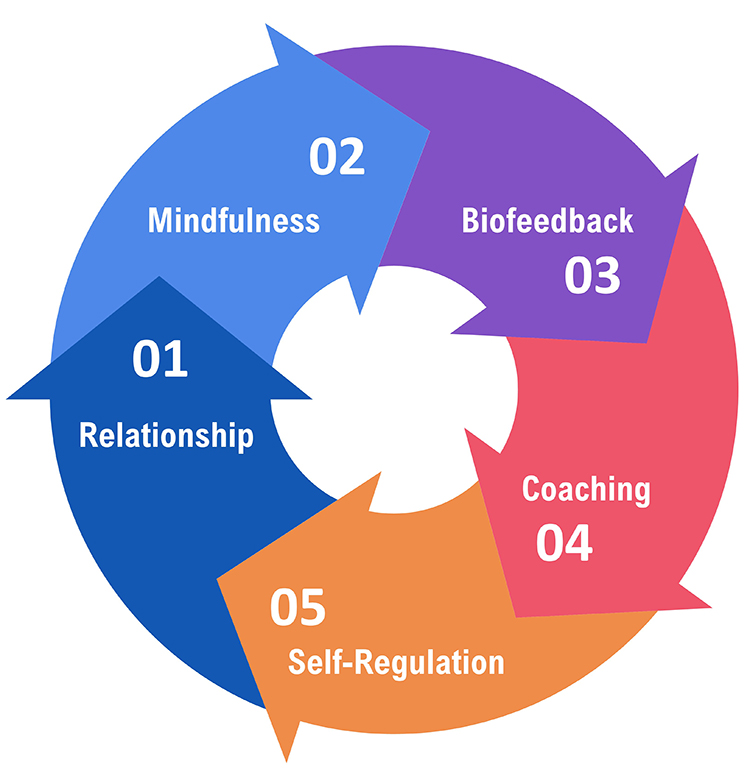

The Three Pillars of Effective Biofeedback

The client-practitioner relationship forms the foundation of everything else. All the sophisticated equipment in the world will not help much if the client does not trust their therapist or feel motivated to practice. Biofeedback works best when both the client and practitioner approach the work mindfully, with genuine curiosity and attention. And the practitioner needs to be a skilled coach, not just someone who hooks up sensors and watches the screen (Khazan, 2019).

Check Your Understanding

- The official definition states that biofeedback instruments must provide feedback "rapidly." Why is speed important for learning?

- What is the key difference between neurofeedback and neuromodulation techniques like audio-visual entrainment?

- Why does the definition emphasize that changes should "endure without continued use of an instrument"?

- According to the text, what three elements form the foundation of effective biofeedback practice?

Monitoring Versus Modulation: Understanding the Difference

🎧 Listen to Mini-Lecture on Physiological Monitoring and ModulationJust Measuring Is Not Enough

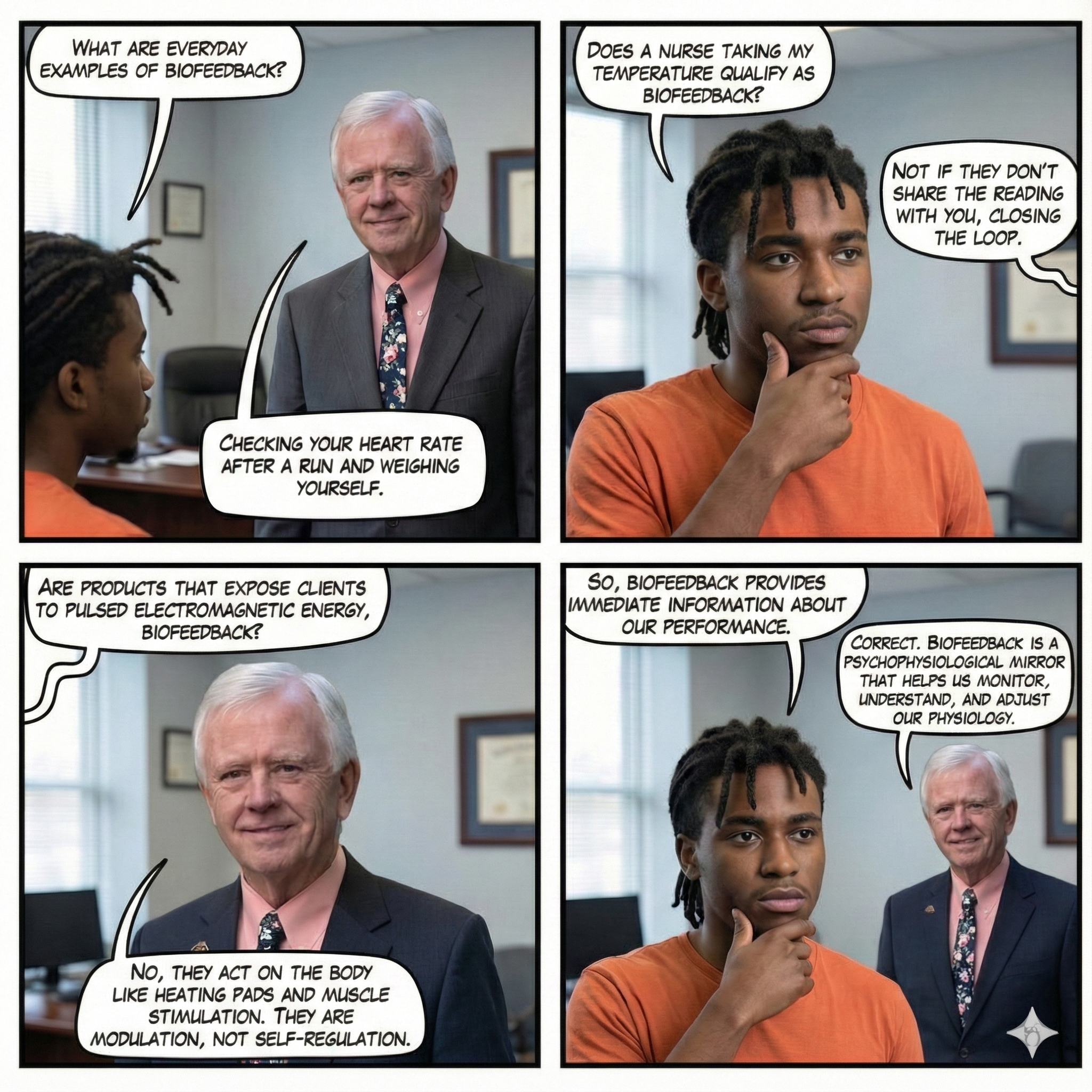

Physiological monitoring simply means detecting and recording biological activity. When a nurse wraps a blood pressure cuff around your arm and reads the numbers, that is monitoring. It becomes biofeedback only when someone tells you the results. Why? Because now you have information about your body's performance that you can potentially use to make changes.

Here is a simple example. Your nurse measures your blood pressure and writes it in your chart without telling you. That is just monitoring. But if she says, "Your blood pressure is 120 over 70," now you have feedback. You might think, "Oh good, that's lower than last time. Whatever I've been doing is working." Or you might think, "That's higher than I expected. I need to pay more attention to my stress levels." Either way, the information creates an opportunity for learning and adjustment.

Doing Something to Your Body Is Not Biofeedback Either

Modulation means stimulating the nervous system to produce change. It is something done to you rather than something you learn to do yourself. Consider electrical muscle stimulation, a treatment where electrodes deliver current to muscles to fatigue them and prevent painful spasms. This can be genuinely helpful for back pain, but it is not biofeedback. You are not learning a skill; a machine is acting on your body.

The distinction matters practically. After muscle stimulation brings spasms under control, a physical therapist might switch to surface electromyographic (SEMG) biofeedback. Now the patient learns to recognize and control their own muscle tension. The modulation got things under control; the biofeedback teaches lasting skills.

True biofeedback combines three elements: physiological monitoring (detecting what is happening), feedback to the client (sharing that information), and self-regulation training guided by that feedback (Khazan, 2019). Take away any element and you have something else, potentially valuable, but not biofeedback.

🎧 Listen to Mini-Lecture on MindfulnessCheck Your Understanding

- A physical therapist measures a patient's muscle activity and records it in her notes but does not show it to the patient. Is this biofeedback? Why or why not?

- Explain the difference between modulation and biofeedback using the muscle stimulation example.

- What are the three essential components that must be present for something to qualify as biofeedback?

- A company sells a device that sends electrical pulses to "rebalance your nervous system" while you relax passively. Would this be considered biofeedback? Explain your reasoning.

The Tools of the Trade: Major Biofeedback Modalities

🎧 Listen to Mini-Lecture on Biofeedback Modalities

Walk into any biofeedback clinic and you will likely encounter several types of equipment. Each measures a different aspect of physiology, and clinicians choose their tools based on the client's specific needs. Think of these as different windows into the body, each offering a unique view.

| Modality | What It Measures | Common Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Electrocardiograph (ECG/EKG) | Heart electrical activity, including heart rate and beat-to-beat variations | Stress management, anxiety, athletic performance, hypertension |

| Electrodermograph (EDA) | Skin electrical activity from sweat gland activity | Anxiety monitoring, stress responses, lie detection research |

| Electroencephalograph (EEG) | Brain electrical activity from cortical neurons (also called neurofeedback) | ADHD, anxiety, depression, epilepsy, peak performance |

| Surface electromyograph (SEMG) | Muscle electrical activity that triggers contraction | Tension headaches, chronic pain, rehabilitation, TMJ disorders |

| Feedback thermometer (TEMP) | Finger or toe temperature reflecting blood flow | Raynaud's disease, migraines, general stress management |

| Photoplethysmograph (PPG) | Blood flow, heart rate, and heart rate variability using light sensors | HRV training, stress management (clients do not have to undress) |

| Respirometer (RESP) | Chest and abdomen movement during breathing | Anxiety, panic, asthma, hyperventilation, HRV training |

Beyond clinical settings, biofeedback has gone mainstream. Fitness trackers on millions of wrists monitor heart rate, sleep patterns, and activity levels. Smartphone apps connect to chest straps or finger sensors for heart rate variability training. Gaming systems incorporate physiological sensors to create experiences where players must stay calm to succeed. The line between clinical tool and consumer product is blurring rapidly.

Buyer Beware: Not Everything Called Biofeedback Is Legitimate

Unfortunately, some companies slap the word "biofeedback" on products that have nothing to do with actual biofeedback. Devices marketed as "Quantum Biofeedback" claim to diagnose and correct cellular abnormalities at a quantum level, but they do not provide any real-time performance feedback, and their manufacturers offer no peer-reviewed evidence. Similarly, pulsed electromagnetic therapy devices have been marketed as "body-biofeedback" even though they are pure modulation with no learning component. If a product claims to fix you without requiring you to develop any skills, it is not biofeedback regardless of what the marketing says.

Check Your Understanding

- A client complains of chronic tension headaches. Which biofeedback modality would likely be most directly relevant, and why?

- Why might a clinician choose a photoplethysmograph (PPG) over an electrocardiograph (ECG) for heart rate variability training, even though both can measure HRV?

- What should make you suspicious that a product marketed as "biofeedback" might not actually be biofeedback?

- How has consumer technology changed the accessibility of biofeedback training?

How Learning and Memory Support Skill Acquisition

To understand why some biofeedback training sticks and some does not, we need to take a brief tour through how your brain learns and remembers. This is not just academic; it has direct practical implications for how clinicians design effective training.

Learning is how we acquire new information, behaviors, or skills. Memory is our capacity to store and retrieve what we have learned (Breedlove & Watson, 2023). Different types of memory involve different brain systems, and biofeedback training engages several of them.

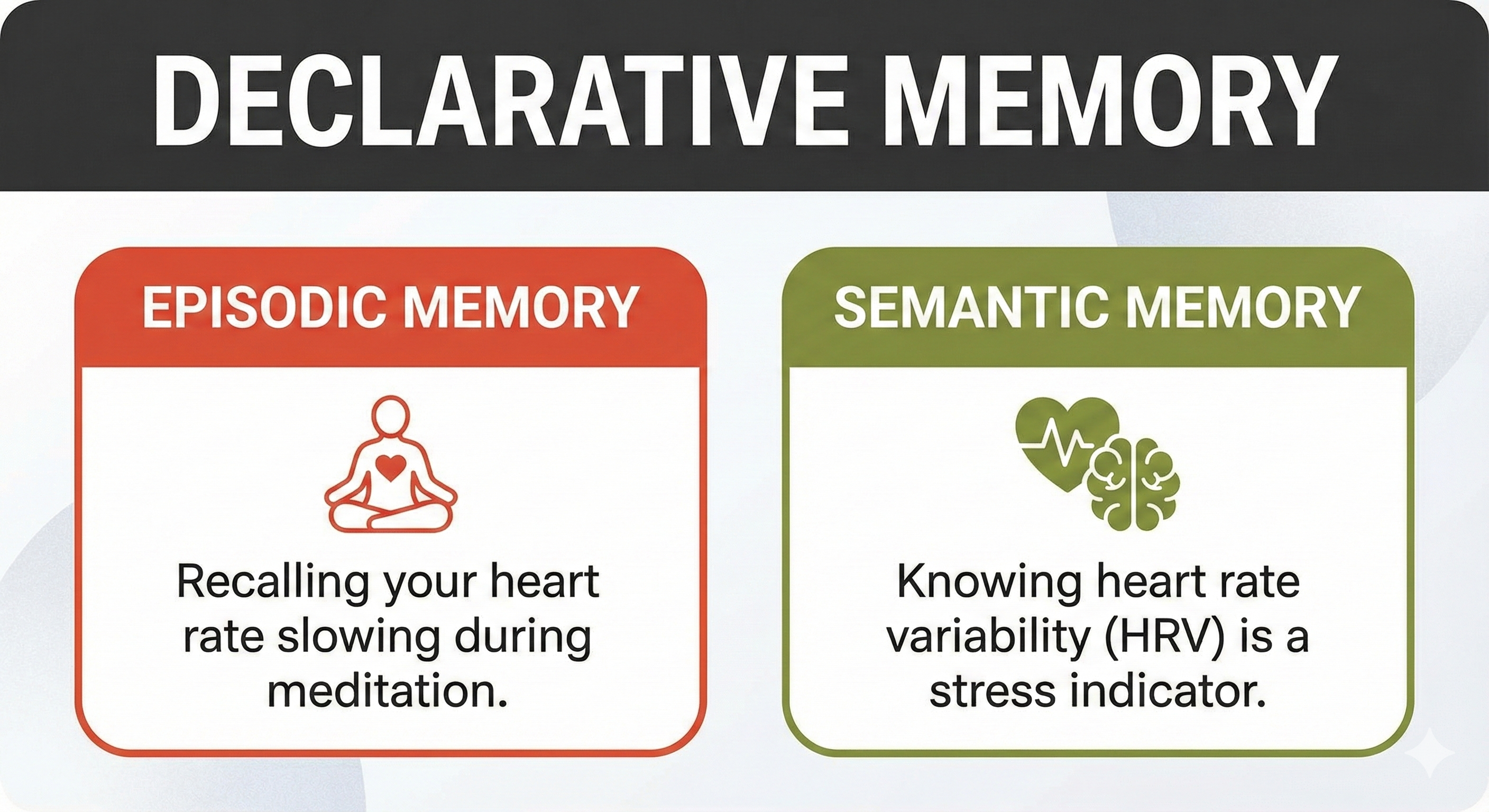

Declarative Memory: The Facts You Can Talk About

Declarative memory handles the "what" of learning: facts, information, and events you can consciously recall and describe to someone else. When you remember that slow breathing typically runs 5-7 breaths per minute, or that your biofeedback therapist's name is Dr. Martinez, you are using declarative memory.

Declarative memory divides into two subtypes. Episodic memories are like mental videos of specific events: you remember what happened, where, when, and in what order. Semantic memories are more like encyclopedia entries: general facts without the personal context of when you learned them.

Marcus is in a tense meeting when he feels his shoulders tightening and his heart racing. He deliberately recalls an episodic memory from his biofeedback session last week: the feeling of calm as his heart rate variability display showed smooth, rolling waves while he breathed slowly. By vividly remembering that experience, he can partially recreate the physiological state. This is declarative memory serving self-regulation in real time.

Clinicians can build declarative memory through discrimination training. For example, you might ask a client to guess their heart rate before showing them the actual value. With practice, their estimates get more accurate. This is especially valuable for chronic pain patients who often have no idea how tense their muscles are at rest.

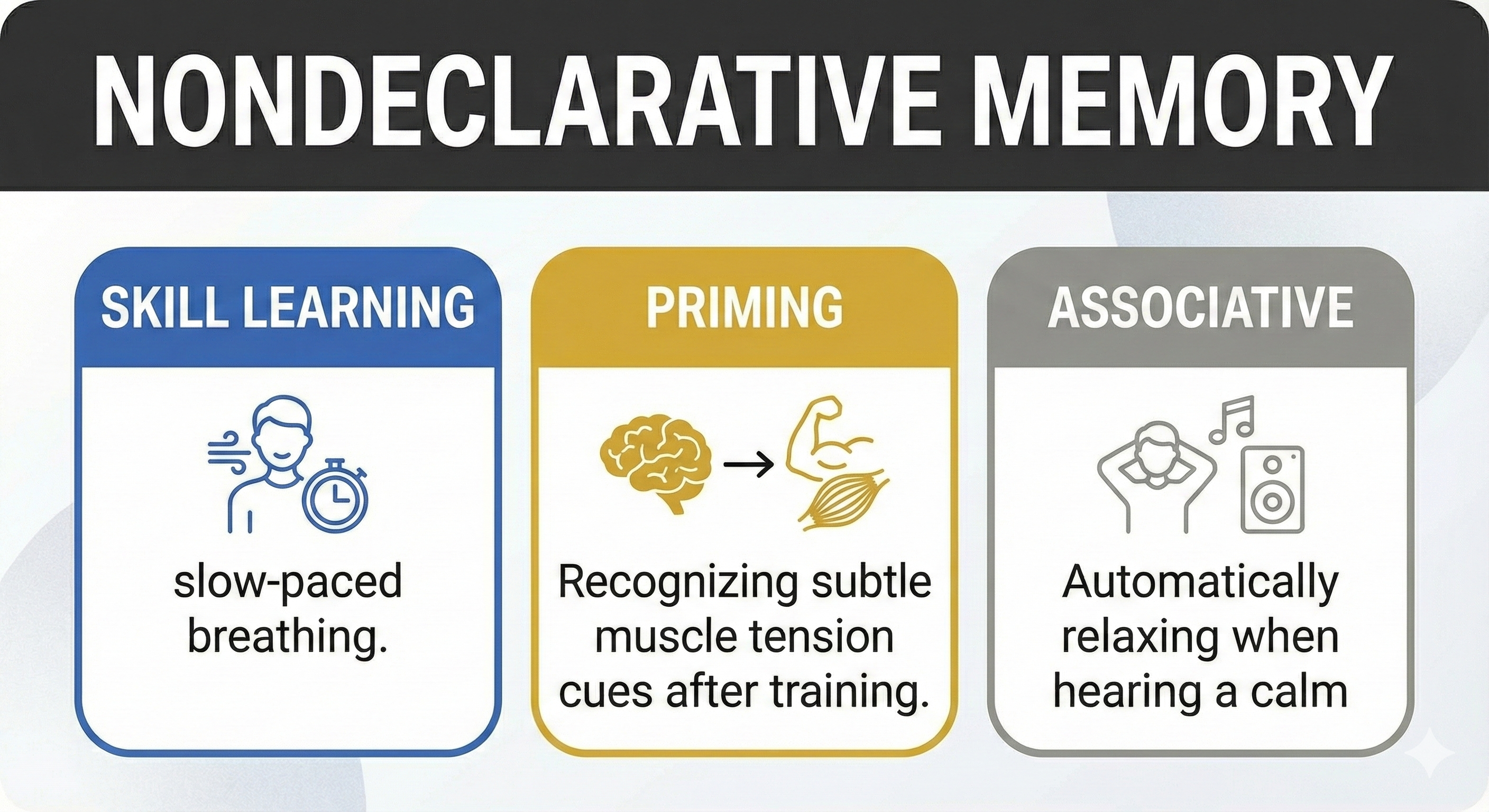

Nondeclarative Memory: The Skills You Show by Doing

Nondeclarative memory (also called procedural memory) handles the "how" of learning. You cannot really explain how you ride a bicycle or tie your shoes; you just do it. The knowledge lives in your body and emerges through action rather than verbal description.

This matters enormously for biofeedback because the skills we are teaching, like smooth, slow breathing or deep muscle relaxation, are fundamentally procedural. Clients need to know about these skills (declarative memory), but more importantly, they need to be able to do them automatically (nondeclarative memory).

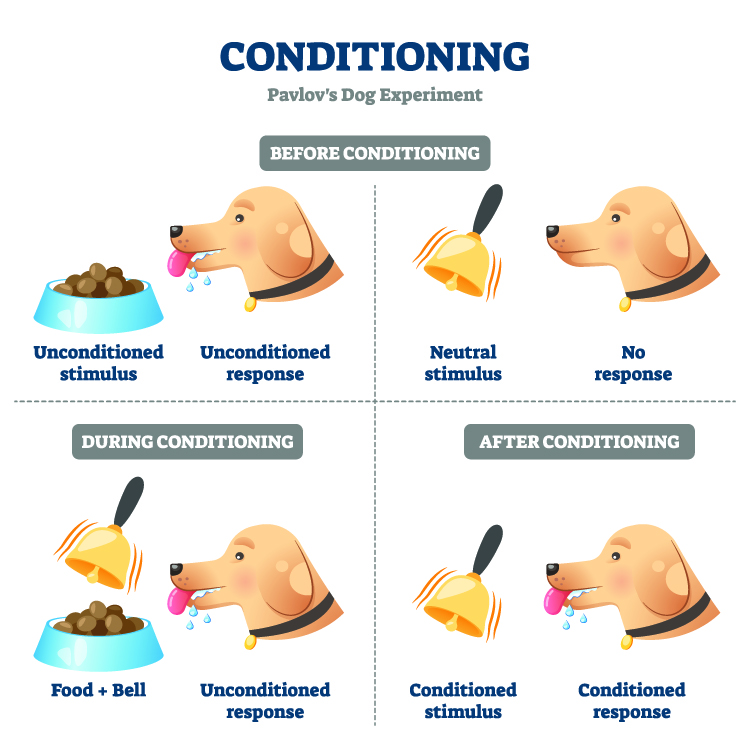

Classical and Operant Conditioning

Classical conditioning connects stimuli that occur together. Pavlov's dogs learned that a bell predicted food, so they started salivating at the bell alone. In biofeedback, we often want to create helpful associations. Maybe a client learns to associate sitting down at their desk with taking three slow breaths. The environmental cue (sitting down) triggers the relaxation response without conscious effort.

Operant conditioning shapes behavior through consequences. When behavior leads to good outcomes, we do more of it. When it leads to bad outcomes, we do less. In biofeedback, the pleasant display changes (a game advancing, a tone sounding, a number improving) reinforce the physiological changes that produced them.

Understanding reinforcement helps clinicians design effective training. Positive reinforcement means behavior increases because something good follows it. Your client practices slow breathing, feels calmer, and is more likely to practice again tomorrow. Negative reinforcement means behavior increases because something unpleasant goes away. Your client practices slow breathing, their anxiety decreases, and they are more likely to use this strategy next time they feel anxious.

Shaping: Building Skills Step by Step

Shaping is an operant technique that teaches complex behaviors by reinforcing successive approximations. You do not expect a client to achieve perfect deep relaxation on day one. Instead, you praise and reinforce whatever progress they make. "Great! Your trapezius tension dropped from 8 microvolts to 6. Let's see if we can get it to 5."

Check Your Understanding

- Explain the difference between declarative and nondeclarative memory using an example from biofeedback training.

- Why is discrimination training valuable for chronic pain patients?

- How might a clinician use classical conditioning to help a client manage workplace stress?

- What is shaping, and why is it more realistic than expecting perfect performance from the beginning?

- Explain the difference between positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement using biofeedback examples. (Hint: both increase behavior; they differ in how.)

Six Ways Experts Have Explained Biofeedback

🎧 Listen to Mini-Lecture on Six Influential Biofeedback ModelsOver the decades, clinicians and researchers have proposed different ways of understanding what biofeedback is and how it works. These models are not just academic exercises; the model you hold in your head shapes how you design treatment. Let us look at six influential perspectives.

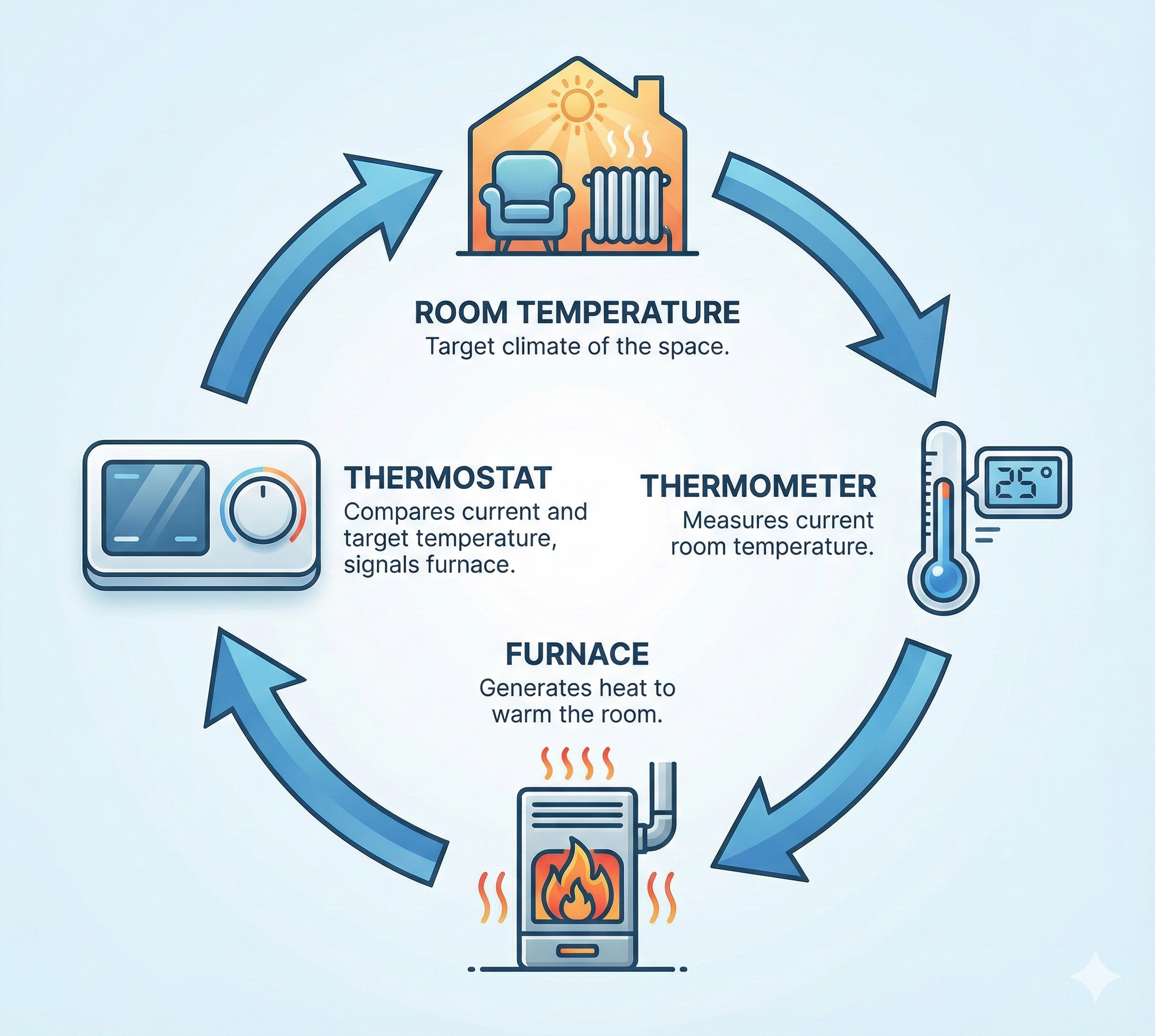

The Thermostat Model (Cybernetics)

The cybernetic model views biofeedback as similar to a home heating system. You set a thermostat to 70°F. If the temperature drops below that setpoint, the furnace kicks on. When it reaches the target, the furnace shuts off. Your body works similarly, constantly making adjustments to maintain homeostasis around various setpoints.

From this perspective, biofeedback supplements your natural proprioception (your sense of your body's state) when that sense is not working well enough. If you cannot feel that your blood pressure is elevated or your muscles are tense, adding external feedback helps you bring these variables back under control.

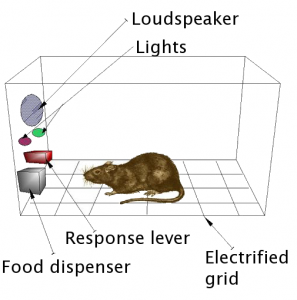

The Rat-in-a-Box Model (Operant Conditioning)

The operant conditioning model treats biofeedback as straightforward reinforcement learning. The feedback display reinforces desired physiological changes, just as food pellets reinforce a rat pressing a lever. No awareness or insight required; just stimulus-response-reinforcement.

This model has problems. First, operant conditioning is only one of several learning processes involved. Second, and more practically, reinforcement without instruction is incredibly inefficient. Imagine a running coach who only told you your times but never showed you good technique. You might eventually improve through random experimentation, but it would take forever.

However, recent work by Kerson, Sherlin, and Davelaar (2025) argues that while the operant conditioning model is incomplete, understanding reinforcement design remains clinically essential. Their central insight is that neurofeedback outcomes improve when clinicians stop treating feedback as mere "information" and start treating it as an engineered learning environment. Your protocol is not just a physiological target; it is a training ecosystem that either facilitates learning and stability or confuses and destabilizes it.

This reframe explains familiar clinical puzzles. Why does a client "do great" in session but cannot reproduce the state at home? Why do improvements plateau even when the client is motivated and compliant? Why do some clients improve even when the protocol is not perfectly matched, while others need a very precise setup? These patterns often reflect basic learning variables such as reinforcement consistency, timing, and the client's ability to recognize and re-enter the trained state on demand (Kerson et al., 2025).

The Prescription Pad Model (Drug Metaphor)

The drug model treats biofeedback like medication: give the patient a certain number of "doses" (sessions) and expect improvement. "Take 10 sessions of temperature biofeedback and call me in a month."

This approach misses the point entirely. If biofeedback is skill learning, then the number of sessions matters far less than whether the client actually masters the skill. You would not tell a piano student, "Practice for exactly 10 hours and you'll be ready for Carnegie Hall." You train to criterion: the client is done when they can do the thing, not when they have logged a certain number of hours.

The Sugar Pill Model (Placebo Effect)

The placebo model suggests that biofeedback works through belief and expectation rather than any specific skill learning. If clients expect to get better, they do, regardless of what the equipment actually shows.

Placebo effects are real and can amplify any treatment, but biofeedback produces measurable, specific changes (like documented blood pressure reductions) that go beyond what placebo typically achieves. The skills are real, even if belief helps.

The Spa Day Model (Relaxation)

The relaxation model assumes biofeedback is inherently calming, like a massage or a warm bath. Hook someone up to sensors and they will relax.

This is dangerously wrong. First, feedback about your physiology is not always relaxing. Telling someone their blood pressure is dangerously high tends to make them more stressed, not less. Second, whether training produces relaxation depends entirely on instructions and strategy. A competitive person trying to "beat" the biofeedback display may increase their stress. Third, relaxation training itself sometimes backfires. Up to 40% of people experience relaxation-induced anxiety, where attempting to relax triggers distress.

The Coach Model (Skill Development)

The skill development models proposed by Blanchard and Epstein (1978) and Shellenberger and Green (1986) view biofeedback as coaching toward mastery. The therapist is like an athletic coach: assessing the client, explaining goals, demonstrating techniques, providing feedback on performance, and gradually increasing challenge as skills develop.

Blanchard and Epstein identified five components of self-regulation: self-monitoring (noticing what is happening in your body), discrimination (recognizing when to use your skills), self-control (actually using the skills), self-reinforcement (patting yourself on the back for success), and self-maintenance (keeping up the practice over time).

Check Your Understanding

- What is the main limitation of the operant conditioning model of biofeedback?

- Why is the drug model problematic? What does "training to criterion" mean, and why does it make more sense?

- Give two reasons why the relaxation model oversimplifies what happens in biofeedback training.

- According to Blanchard and Epstein, what are the five components of self-regulation?

- Which of the six models do you think best captures what biofeedback actually is? Defend your choice.

Reinforcement Design: Engineering the Learning Environment

Understanding that biofeedback involves operant learning is only the first step. The critical question is: how well is your feedback system actually teaching? Kerson, Sherlin, and Davelaar (2025) argue that clinicians should treat each session as a learning experiment with controllable variables. When training stalls or produces inconsistent results, the problem often lies in the learning environment rather than in the client's motivation or ability.

Reinforcement Schedules Are Clinical Levers

A reinforcement schedule is the rule that determines when feedback is delivered. Many biofeedback systems operate under continuous reinforcement, meaning the client receives an immediate reward whenever the signal meets the criteria. Other systems use interval schedules, meaning they evaluate performance at fixed intervals and reward only if the criteria are met at that instant. This technical distinction dramatically affects what clients experience during training.

If reinforcement is essentially continuous, clients tend to feel a smoother, more responsive system. They can experiment and notice what increases reward. If reinforcement is sampled at intervals, brief moments of doing it right may be missed, creating the subjective experience that the system is stingy or inconsistent, even when the client is intermittently producing the target state. Clinicians can treat reward feel, meaning the client's subjective sense of how responsive and predictable the feedback seems, as a diagnostic signal. If a competent, engaged client reports that the reward seems disconnected from their efforts, suspect a schedule, threshold, or artifact issue before assuming resistance or poor insight (Kerson et al., 2025).

When Feedback Becomes Random

Random reinforcement, sometimes used as a sham condition in research, means feedback is not tightly linked to the client's actual physiological state. Kerson and colleagues (2025) point out that sessions can unintentionally drift toward "sham-like" conditions whenever reinforcement loses contingency with the target signal. This can happen for mundane reasons: EEG artifact can inflate or suppress the very metrics you are rewarding, muscle tension can masquerade as high-frequency activity, eye movements can contaminate frontal sites, and poor electrode contact can introduce slow drift that the client cannot control.

From the client's perspective, the task becomes a slot machine. Some clients continue to improve because they learn relaxation, attentional stability, or expectancy-driven control. Other clients stagnate because the nervous system cannot reliably discover what earns reward. The practical solution is to track reinforcement integrity as a routine clinical variable. Ask yourself: "Is the client being rewarded for what I think I am rewarding?" If you are unsure, increase artifact monitoring, reduce task complexity, tighten signal quality checks, or temporarily shift training to a simpler physiological channel while you troubleshoot (Kerson et al., 2025).

Timing and Latency: Late Rewards Teach the Wrong Thing

Feedback is not only about whether the reward occurs, but also about when it occurs. Feedback latency refers to the time delay between a physiological event and the delivery of feedback. Reinforcement learning depends on a tight coupling between a successful response and its consequence. If the consequence arrives late, the nervous system may strengthen the response that occurred closer in time to the reward, which might be a compensatory strategy, an artifact, or a brief change unrelated to the intended target (Kerson et al., 2025).

Your biofeedback platform has a sequence of delays: signal acquisition, filtering, artifact handling, feature computation, threshold comparison, and display rendering. Even when each step is fast, total latency can accumulate. Clients who report that the feedback feels "behind" may be noticing a real mismatch. Clients who can increase reward only through abrupt, effortful actions like tensing, blinking, or breath-holding may be training artifacts that are temporally aligned with the delayed reward. When you correct latency issues or simplify processing, clients often find they can succeed with calmer, steadier strategies, and the reward becomes easier to sustain.

A practitioner notices that during SMR training, a client's reward rate improves dramatically whenever she shifts in her chair. Upon investigation, the clinician discovers that movement artifact is briefly boosting the 12-15 Hz band, and the system's processing delay means the reward coincides with settling back into stillness rather than with the initial movement. The client has learned to fidget, not to produce calm focus. By improving electrode contact and reducing filter delay, the clinician restores the intended contingency. The client must now find a different, calmer route to reward.

Shaping and Threshold Management

Many clients benefit from an initial phase where rewards are frequent enough to allow the nervous system to discover the pathway, followed by gradual tightening of criteria. This process, called shaping, means reinforcing successive approximations toward the final target rather than demanding it immediately. If the task is too hard at the beginning, the client does not get enough successful trials to learn what works.

Threshold management matters as well. If thresholds auto-adjust too aggressively, the client experiences a moving target. If thresholds never adjust, the client can reach a ceiling where improvement no longer changes the reward. A clinically sensible approach is to adjust thresholds deliberately, in small steps, and to explain the purpose: "We are making it slightly harder, so your brain keeps learning," or "We are making it slightly easier so you can find the pattern again" (Kerson et al., 2025).

Check Your Understanding

- What is a reinforcement schedule, and why does the difference between continuous and interval schedules matter clinically?

- What does "reward feel" mean, and why should clinicians treat it as diagnostic information?

- How can a biofeedback session unintentionally drift toward "sham-like" conditions?

- Explain how feedback latency can cause a client to learn the wrong response.

- What is shaping, and why is it often more effective than starting with the final performance criterion?

What Makes Training Actually Work

Knowing the theory is one thing; making biofeedback work in practice is another. This section covers the practical elements that separate effective training from wasted time.

🎧 Listen to Lecture on Training ProcessContext Changes Everything

Here is a crucial insight: just looking at physiological information does nothing by itself. Glancing at a stopwatch does not make you run faster. The effect of feedback depends entirely on the context in which it is provided.

When biofeedback is combined with physical therapy, it becomes "biofeedback-assisted rehabilitation." Combined with relaxation training, it becomes "biofeedback-assisted relaxation." The equipment amplifies and focuses whatever intervention you are actually doing. Without skilled coaching, the information is just numbers on a screen.

The Therapist Matters More Than You Might Think

In an era of sophisticated technology, it is tempting to think the equipment does the work. Research tells a different story. Taub and School (1978) demonstrated a striking person effect when teaching hand-warming. An "informal and friendly" trainer helped 19 of 21 participants (90.5%) learn to raise their finger temperature. A more formal, "impersonal" trainer achieved success with only 2 of 22 participants (9.1%). Same technique, same equipment, radically different results based on the human relationship.

Your Brain Actually Syncs with Your Therapist's Brain

Recent neuroscience has discovered something remarkable: during effective therapy, the brain activity of therapist and client actually synchronizes. This inter-brain synchrony occurs when two people engage in shared emotional and cognitive processes, maintaining eye contact, mirroring expressions, and synchronizing speech rhythms (Meehan, 2025; Sened et al., 2022).

This neural coupling appears to strengthen emotional bonds and improve cognitive flexibility. Clients who experience high levels of synchrony with their therapists often report deeper insights and greater capacity for change. For therapists, this suggests that being fully present and attuned, not just technically competent, may directly enhance treatment effectiveness.

Three related concepts capture what makes therapeutic relationships work. Relational presence means being fully engaged with the client so they feel genuinely seen and valued. Attunement means accurately perceiving and responding to the client's emotional signals. Co-regulation means helping clients manage their emotional states through the interaction itself, which over time teaches them to regulate themselves.

Practice Your Own Skills

Would you trust a personal trainer who was obviously out of shape? Peper (1994) argued strongly that biofeedback therapists must be "self-experienced," having developed the skills they teach. If you want to help clients learn to warm their hands and slow their breathing, you should be able to do these things yourself.

Personal practice has multiple benefits. You develop the skills firsthand. You gain confidence that your methods actually work. You understand the frustrations clients will inevitably encounter. And you avoid unconsciously modeling the opposite of what you are teaching, like demonstrating relaxation while your own shoulders are up around your ears.

Practice Outside the Clinic Is Essential

🎧 Listen to Mini-Lecture on Biofeedback PracticeIf a client trains for one hour per week in your clinic, that leaves 167 hours when they are somewhere else. Skills learned in the clinic do not automatically transfer to the car, the office, or the dinner table with difficult relatives. Clients must practice in the environments where they actually need their skills.

Homework typically includes lifestyle modification (changing diet, exercise, or sleep habits), continued biofeedback practice with portable equipment or apps, abbreviated relaxation exercises like Stroebel's 6-second Quieting Response that can be done anywhere, deep relaxation practices like meditation or Progressive Relaxation that require dedicated time, and self-monitoring to track symptoms and practice.

Why is regular practice so critical? First, more time on task means faster skill development. Second, skills need to be practiced where they will be used, or they will not transfer. Third, practice makes skills automatic. Think about learning to drive a manual transmission: initially you focus intensely on every shift, but eventually you shift gears without conscious thought. Stroebel's Quieting Response may take six months of regular practice before it becomes automatic.

The Clinician as Learning Coach

Kerson, Sherlin, and Davelaar (2025) emphasize that lasting benefits depend on bridging implicit operant learning with the client's ability to recognize and re-enter the trained state. Phenomenological awareness means the client learns to notice and describe what the target state feels like, how it arises, and how to return to it voluntarily. This is how you reduce "I can do it in session but not in life."

You can cultivate this awareness without turning sessions into therapy talk. After a good run, ask the client to describe the state in sensory language. What changed in breathing, muscle tone, gaze, posture, or emotional tone? What was the smallest action that helped? If the client cannot describe it, provide options rather than forcing introspection. Over time, the client builds a personal map of the state that they can navigate independently.

This approach also helps you detect when learning is happening through an unhelpful route. A client might increase reward by becoming rigidly focused, which appears as "success" in the signal but feels subjectively like strain. If you capture phenomenology, you can redirect learning toward a calmer strategy that supports generalization, the transfer of learned skills from the training context into daily life (Kerson et al., 2025).

Building Transfer on Purpose

Transfer trials reduce or remove feedback so the client must reproduce the state without constant external cues. You can build transfer inside the session by turning feedback off for brief intervals, then turning it back on to check whether the client can regain the state. Between sessions, prescribe practice that mirrors the trained state: short blocks of attention training, paced breathing within a comfortable range, or relaxation routines tied to the same cues used in session.

Finally, watch for accidental training, where the client discovers that jaw tension, breath holding, or staring harder increases reward. These compensatory strategies may work in the short term but are not sustainable. Monitor posture, facial tension, breathing, and effort level, and explicitly reinforce strategies that are healthy and generalizable. The goal is a skill the client can use anywhere, not a trick that only works when hooked up to equipment (Kerson et al., 2025).

Check Your Understanding

- What did Taub and School's research reveal about the importance of the therapist's interpersonal style?

- Explain inter-brain synchrony. Why might it matter for biofeedback training effectiveness?

- Why does Peper argue that biofeedback therapists should develop the skills they teach?

- If a client only practices during clinic sessions, what problems are likely to occur?

- What is the Quieting Response, and why does it take months to become automatic?

- What is phenomenological awareness, and how does cultivating it help with generalization?

- What are transfer trials, and why are they important for bridging in-session success to real life?

The Art of Voluntary Control

The goal of biofeedback is voluntary control: producing requested physiological changes on command without any external feedback. "Warm your hands to 95°F right now." If you can do it, you have achieved voluntary control.

Getting there requires understanding two very different modes of willing. Passive volition means inviting or allowing change to happen. Words like "allow," "let," "permit," and "imagine" trigger this mode. It engages the parasympathetic nervous system, which supports rest and recovery.

Active volition means commanding or forcing change. Words like "make," "try," and "force" trigger this mode. It engages the sympathetic nervous system, which supports action and arousal.

Here is the paradox: you cannot "try to relax." The moment you apply effort and determination, you activate the sympathetic system, which is the opposite of relaxation. Khazan (2013) calls "try to relax" an oxymoron. This explains many common experiences. You cannot force yourself to fall asleep. You cannot try hard to urinate. Elite archers in Zen traditions learn that forcing the shot ruins it; the arrow must be released, not pushed.

Wegner and colleagues demonstrated this paradox experimentally. In one study, people told to suppress thoughts about a white bear thought about white bears more often than people instructed to think about them deliberately (Wegner et al., 1987). In another study, people instructed to relax during difficult tasks showed higher skin conductance (a stress indicator) than people given no relaxation instructions (Wegner et al., 1997). Trying to relax made them more stressed.

Effective self-regulation involves flexibly shifting between active and passive modes. Jacobson's Progressive Relaxation cleverly combines both: you actively tense a muscle group (active volition), then release and allow it to relax (passive volition). The contrast helps you detect residual tension you might otherwise miss.

Let Clients Find What Works for Them

Schultz, who developed Autogenic Training, believed imagery is the language the body understands best. An image serves as a blueprint for physiological change. But research on successful self-regulators shows they use all sorts of strategies: pictures, sounds, bodily sensations, feelings, abstract concepts. There is no one right way.

Encourage clients to experiment. Some will visualize warm sunshine on their hands to raise finger temperature. Others will recall the feeling of holding a warm coffee mug. Still others will use a purely abstract intention. When clients discover strategies that work for them, they feel empowered as collaborators rather than passive recipients of treatment. This increases their self-efficacy, their belief that they can achieve desired outcomes.

Check Your Understanding

- What is voluntary control, and how would you test whether a client has achieved it?

- Explain the difference between passive volition and active volition. Why is this distinction important for relaxation training?

- Why is "try to relax" considered an oxymoron?

- How does Progressive Relaxation cleverly combine active and passive volition?

- Why should clinicians encourage clients to experiment with different strategies rather than prescribing one "correct" approach?

Designing Effective Treatment

Follow the Evidence

Clinical intuition has its place, but evidence should guide treatment design. Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.), published by the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, summarizes research on which approaches work for which conditions. Consulting this resource before designing treatment can save you from repeating others' mistakes.

For years, clinicians assumed that Raynaud's disease (painful cold fingers triggered by cold exposure) was caused by excessive sympathetic nervous system activity. Treatment focused on general stress reduction and relaxation training. But research by Freedman and colleagues showed this model was incomplete. What's Really Going On in Raynaud's?

For years, scientists assumed Raynaud's was all about an overactive sympathetic nervous system—your body's "fight-or-flight" wiring going haywire. But when researchers looked for direct proof? It wasn't really there, at least not for primary Raynaud's. So where's the actual problem?

It turns out the real culprit is likely in the tiny blood vessels of your fingers and toes themselves. The blood vessels become hypersensitive to signals telling them to constrict, the endothelium (the inner lining of blood vessels) doesn't work properly, and the body doesn't release enough vasodilatory neuropeptides—chemical messengers that normally tell vessels to relax and open up. That said, the sympathetic nervous system isn't completely off the hook. It still plays a supporting role, especially when cold temperatures or stress trigger an episode. And in secondary Raynaud's—where the condition stems from another disease—sympathetic involvement may be more significant.

Here's the bottom line: Raynaud's isn't a single-cause problem. It's multifactorial, meaning several mechanisms contribute. This actually explains something puzzling clinicians have noticed—different patients respond to different treatments. If everyone had the exact same underlying problem, one therapy would work for everyone. But that's not what happens, which tells us multiple pathways are involved.

Bidirectional temperature biofeedback with cold challenge, where clients learn to both warm and cool their hands while exposed to cold, produces better results than stress management alone. Clinicians who stuck with the old model provided less effective treatment.

Personalize to the Individual

Ten clients with "hypertension" may have ten different psychophysiological profiles. One might show excessive muscle tension. Another might show dysfunctional breathing patterns. A third might have poor heart rate variability. Effective treatment addresses each individual's specific abnormalities rather than applying a one-size-fits-all protocol.

Personalization also means training to criterion rather than for a fixed number of sessions. A client is done when they can demonstrate the skill, not when they have completed session number 12. Different people have different learning curves.

Practical Design Considerations

Khazan (2019) recommends limiting biofeedback practice sessions to about 20 minutes maximum. Longer sessions may produce diminishing returns or fatigue.

Bidirectional training, where clients learn to both increase and decrease a physiological response, often produces better outcomes than training in one direction only. Learning to both warm and cool your hands, or to both increase and decrease a brain rhythm, may develop more complete control.

Spaced practice, spreading sessions over time, generally works better than massed practice, cramming sessions together. A 15-session protocol might involve two sessions per week for five weeks, then one session per week for five more weeks. This gives skills time to consolidate between sessions.

The 70-30 rule (Olton & Noonberg, 1980) helps calibrate difficulty: raise the challenge when clients succeed more than 70% of the time, lower it when they succeed less than 30%. This keeps training in the productive zone, neither too easy (boring) nor too hard (frustrating).

Choose Your Metaphors Carefully

How you explain biofeedback shapes how clients approach it. Two useful metaphors:

"Biofeedback is like coaching a runner using a stopwatch." This emphasizes that the feedback is information to guide skill development, and that coaching makes the difference.

"Biofeedback is like teaching carpentry, not hammering." This communicates that the goal is general self-regulation ability, not just mastery of one specific technique.

Check Your Understanding

- Why did the old stress-reduction approach to Raynaud's disease prove less effective than bidirectional temperature training with cold challenge?

- What does "training to criterion" mean, and why is it preferable to providing a fixed number of sessions?

- Explain the 70-30 rule. What problems does it help prevent?

- Why might spaced practice produce better results than massed practice?

- Create your own metaphor for explaining biofeedback to a new client. What does your metaphor emphasize?

Glossary

70-30 rule: a guideline that training thresholds should be raised when a client succeeds more than 70% of the time and lowered when they succeed less than 30% of the time.

abbreviated relaxation exercises: brief procedures like Stroebel's Quieting Response that can be practiced many times daily in any setting.

accidental training: an unintended learning process in which the client is reinforced for artifacts, compensatory strategies, or non-target behaviors because feedback is not tightly contingent on the intended physiological state.

active volition: a mode of willing where you command or force yourself to act, triggered by words like "make" or "try."

approach-avoidance conflict: a situation where symptoms are both distressing and rewarding, making change difficult.

attunement: the therapist's ability to accurately perceive and respond to a client's emotional state.

Autogenic Training: a deep relaxation procedure developed by Schultz and Luthe involving standardized exercises, modifications, and meditation.

aversive punishment: the weakening of behavior when followed by an unpleasant consequence.

avoidance-avoidance conflict: a situation where both the symptoms and the proposed treatment seem unpleasant.

bidirectional temperature biofeedback with cold challenge: training to both increase and decrease peripheral temperature while exposed to cold conditions.

bidirectional training: teaching clients to both increase and decrease a physiological response.

biofeedback: a learning process that uses instruments to provide real-time information about physiological activity, enabling individuals to develop voluntary control for improved health and performance.

classical conditioning: a learning process where a neutral stimulus becomes capable of triggering a response through association with a stimulus that naturally produces that response.

co-regulation: a process where the therapist helps the client manage emotional states through their interaction, supporting the development of self-regulation skills.

conditioned response: in classical conditioning, a response triggered by a conditioned stimulus.

conditioned stimulus: a previously neutral stimulus that, through conditioning, becomes capable of triggering a response.

continuous reinforcement: a reinforcement pattern in which a reward is delivered whenever the target criterion is met, providing immediate and consistent feedback to the learner.

cybernetic model: the view that biofeedback functions like a thermostat system, with setpoints, feedback, and corrective adjustments.

declarative memory: memory for facts and information that can be consciously recalled and verbally described.

discrimination: the ability to perceive differences in physiological states; also, in conditioning, responding differently to similar stimuli.

discrimination training: exercises that improve a client's ability to perceive their physiological state accurately.

discriminative stimuli: environmental or internal cues that signal when a particular behavior is appropriate.

drug model: the problematic view that biofeedback can be administered in fixed doses like medication.

electrocardiograph (ECG/EKG): an instrument measuring heart electrical activity.

electrodermal activity (EDA): skin electrical activity reflecting sweat gland activity.

electroencephalograph (EEG): an instrument measuring brain electrical activity.

electromyograph (EMG/SEMG): an instrument measuring muscle electrical activity.

episodic memory: memory for specific events including their context (when, where, in what order).

extinction: the weakening of a learned response when reinforcement stops or the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus.

feedback latency: the time delay between a physiological event and the delivery of feedback; excessive latency can cause the nervous system to strengthen the wrong response.

feedback thermometer: an instrument measuring finger or toe temperature as an indicator of peripheral blood flow.

generalization: the transfer of a learned skill from the training context into daily-life situations and demands.

homeostasis: the body's maintenance of stable internal conditions through continuous adjustment.

inter-brain synchrony: the alignment of neural activity between two people during social or therapeutic interaction.

interval schedule: a reinforcement schedule in which the system evaluates performance at set time intervals and delivers a reward only when criteria are met at those instants.

learning: the process of acquiring new information, behaviors, or skills.

lifestyle modification: changes in daily habits (diet, exercise, sleep, caffeine intake) that support treatment goals.

massed practice: concentrating training sessions into a short time period.

mastery model: Shellenberger and Green's view of biofeedback as athletic-style coaching toward skill mastery.

memory: the capacity to store and retrieve learned information.

mindfulness: nonjudgmental, present-moment awareness.

modulation: stimulating the nervous system to produce change, as opposed to providing feedback for learning.

negative reinforcement: the strengthening of behavior because it removes or prevents something unpleasant.

neurofeedback: biofeedback focused on brain electrical activity.

nondeclarative memory: memory for skills and procedures demonstrated through action rather than verbal description.

operant conditioning: learning where behavior is shaped by its consequences.

operant conditioning model: the view that biofeedback is simply reinforcement learning.

parasympathetic division: the branch of the autonomic nervous system that supports rest, recovery, and energy conservation.

passive volition: a mode of willing where you invite or allow change to happen, triggered by words like "allow" or "imagine."

person effect: the finding that therapist interpersonal style dramatically affects training outcomes.

phenomenological awareness: a clinician-supported ability to notice, describe, and make meaning of the subjective experience of the target physiological state, enabling the client to recognize and re-enter the state voluntarily.

photoplethysmograph (PPG): an instrument using light to measure blood flow, heart rate, and heart rate variability.

physiological monitoring: detecting and recording biological activity.

placebo model: the view that biofeedback works through belief and expectation rather than specific skill learning.

positive reinforcement: the strengthening of behavior because it produces something pleasant.

Progressive Relaxation: Jacobson's technique of systematically tensing and releasing muscle groups.

proprioception: the sense of body position, movement, and muscle state.

Quieting Response: Stroebel's 6-second relaxation exercise involving a stress cue, inward smile, easy breath, and muscle release.

relational presence: the therapist's full engagement with the client in a way that fosters genuine connection.

relaxation-induced anxiety: increased anxiety triggered by relaxation training, occurring in up to 40% of clients.

relaxation model: the oversimplified view that biofeedback is inherently relaxing.

reinforcement consistency: the degree to which feedback rewards are reliably linked to the client's actual production of the target physiological state.

reinforcement schedule: the rule that determines when and how feedback rewards are delivered in response to performance.

respirometer: an instrument measuring chest and abdomen movement during breathing.

reward feel: a client's subjective sense of how responsive and predictable the feedback is, meaning whether rewards seem clearly tied to their efforts and internal state changes.

secondary gains: rewards that maintain symptoms, such as attention or reduced responsibilities.

self-efficacy: belief in one's ability to achieve desired outcomes.

self-monitoring: observing and tracking one's own physiological states and symptoms.

self-quantification: using technology to track personal data about inputs, states, and performance.

self-regulation: controlling physiological states without external feedback.

semantic memory: memory for general facts without specific contextual information.

shaping: teaching complex behaviors by reinforcing successive approximations.

somatosensation: the perception of touch, temperature, and pain.

spaced practice: distributing training sessions over an extended time period.

spasmodic dysphonia: a voice disorder involving abnormal laryngeal muscle contractions.

spontaneous recovery: the return of an extinguished response after a rest period.

stimulus discrimination: responding to one stimulus but not to similar stimuli.

stimulus generalization: responding to stimuli similar to the original conditioned stimulus.

sympathetic division: the branch of the autonomic nervous system that supports action, arousal, and energy expenditure.

transfer trials: a practice method that reduces or removes feedback so the learner must achieve the target state under more naturalistic conditions, bridging in-session success to real-world application.

voluntary control: the ability to produce physiological changes on command without external feedback.

Test Your Knowledge

Click on the ClassMarker logo to take a 10-question test over this unit. Enter your Biofeedback Tutor username and password.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review chapter flashcards.

Visit BioSource Software

BioSource Software offers Human Physiology, which satisfies BCIA's Human Anatomy and Physiology requirement, and Biofeedback100, which provides extensive testing over BCIA's Biofeedback Blueprint.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this chapter, take some time to reflect. How would you explain biofeedback to a new client in plain language? Evaluate yourself as a potential model for the behaviors you might teach: Can you warm your hands on command? Can you slow your breathing to 6 breaths per minute and maintain it comfortably? Where are your strengths? Where do you need development? What steps will you take to build your own self-regulation skills?

References

Adams, S. (2006, October 24). Good news day. http://dilbertblog.typepad.com/the_dilbert_blog/

Annett, J. (1969). Feedback and human behavior. Penguin Books.

Blanchard, E. B., & Epstein, L. H. (1978). A biofeedback primer. Addison-Wesley.

Bliznikas, D., & Baredes, S. (2005, August 4). Spasmodic dysphonia. http://www.emedicine.com/ENT/topic349.htm

Brannon, L., Feist, J., & Updegraff, J. A. (2022). Health psychology: An introduction to behavior and health (10th ed.). Wadsworth.

Breedlove, S. M., & Watson, N. V. (2023). Behavioral neuroscience (10th ed.). Sinauer Associates.

Carlson, N. R., & Birkett, M. A. (2021). Physiology of behavior (13th ed.). Pearson.

Cowings, P. S., Suter, S., Toscano, W. B., Kamiya, J., & Naifeh, K. (1986). General autonomic components of motion sickness. Psychophysiology, 23, 542-551. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00671.x

Cowings, P. S., & Toscano, W. B. (1982). The relationship of motion sickness susceptibility to learned autonomic control for symptom suppression. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 53, 570-575.

Fox, S. I., & Rompolski, K. (2022). Human physiology (16th ed.). McGraw Hill.

Khazan, I. (2013). The clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. John Wiley & Sons.

Khazan, I. (2019). Biofeedback and mindfulness in everyday life: Practical solutions for improving your health and performance. W. W. Norton.

Khazan, I., Shaffer, F., Moss, D., Lyle, R., & Rosenthal, S. (Eds.). Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Kerson, C., Sherlin, L. H., & Davelaar, E. J. (2025). Neurofeedback, biofeedback, and basic learning theory: Revisiting the 2011 conceptual framework. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-025-09756-4

Luria, A. R. (1968). The mind of a mnemonist: A little book about a vast memory. Basic Books.

Meehan, Z. M. (2025). 5-min science: Inter-brain plasticity can enhance psychotherapy. https://www.biosourcesoftware.com/post/5-min-science-inter-brain-plasticity-can-enhance-psychotherapy

Olton, D. S., & Noonberg, A. R. (1980). Biofeedback: Clinical applications in behavioral medicine. Prentice-Hall.

Peper, E., & Shambaugh, S. (1979). Economical biofeedback devices. In E. Peper, S. Ancoli, & M. Quinn (Eds.), Mind/body integration: Essential readings in biofeedback (pp. 557-562). Plenum Press.

Peper, E., Shumay, D. M., & Moss, D. (2012). Change illness beliefs with biofeedback and somatic feedback. Biofeedback, 40(4), 154-159. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-40.4.02

Sened, H., Zilcha-Mano, S., & Shamay-Tsoory, S. (2022). Inter-brain plasticity as a biological mechanism of change in psychotherapy: A review and integrative model. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 16, 955238. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.955238

Shellenberger, R., & Green, J. A. (1986). From the ghost in the box to successful biofeedback training. Health Psychology Publications.

Taub, E., & School, P. J. (1978). Some methodological considerations in thermal biofeedback training. Behavior Research Methods & Instrumentation, 10(5), 617-622. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03205359

Turkelson, L., & Mano, Q. (2021). The current state of mind: A systematic review of the relationship between mindfulness and mind-wandering. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-021-00231-6

Wegner, D., Broome, A., & Blumberg, S. (1997). Ironic effects of trying to relax under stress. Behavior Research and Therapy, 35(1), 11-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00078-2

Wegner, D. M., Schneider, D. J., Carter, S. R., 3rd, & White, T. L. (1987). Paradoxical effects of thought suppression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(1), 5-13.