Pain Applications

What You Will Learn

This chapter explores how biofeedback and neurofeedback can transform the treatment of chronic pain disorders. You will discover why the biopsychosocial model provides the most compelling framework for understanding and treating pain, integrating medical, psychological, and psychophysiological perspectives. You will learn how tension-type headaches arise from an interaction of peripheral muscle tension and central nervous system sensitization, and how the hypothalamus may act as a generator for migraines and cluster headaches.

The unit reveals surprising findings about Raynaud's disease, including why temperature biofeedback works through local vascular mechanisms rather than sympathetic nervous system reduction. You will explore evidence-based protocols for low back pain, myofascial pain, temporomandibular disorders, and complex regional pain syndrome, understanding both the underlying physiology and the specific biofeedback interventions that produce lasting relief.

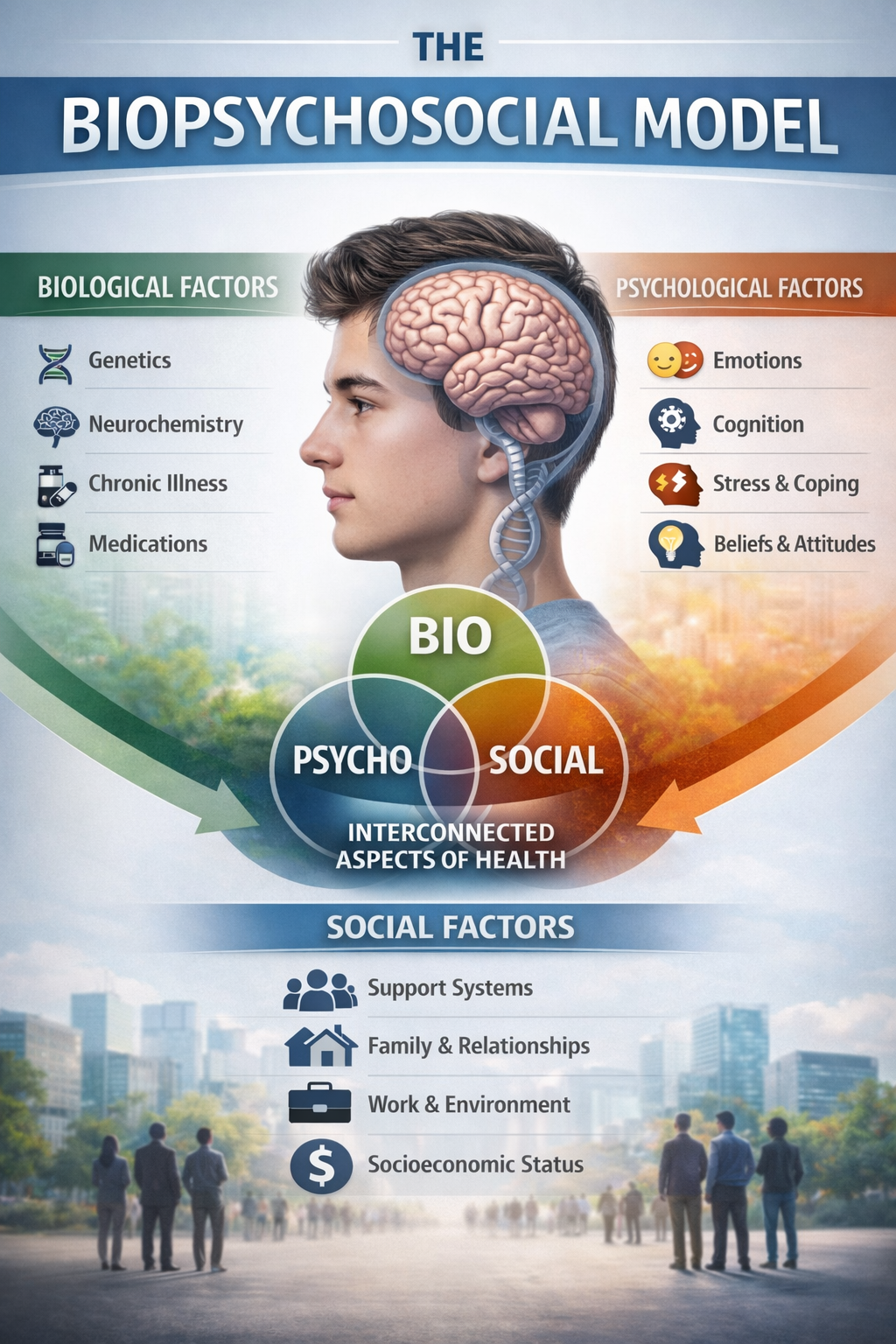

The biopsychosocial model offers a compelling approach to conceptualizing and treating chronic pain disorders. Practitioners who embrace this model understand the importance of comprehensive assessment that integrates medical findings, psychological factors, and psychophysiological measurements. Biofeedback is often efficacious and cost-effective for treating common pain disorders like low back pain and tension-type and migraine headache, frequently allowing clients to reduce medication consumption and emergency room visits.

Here is a sobering statistic: medication-overuse headache (MOH) complicates treatment in many migraine patients who rely heavily on rescue medications. Chronic daily headache is 19.4 times more likely when patients overuse medication, creating a vicious cycle that biofeedback can help break.

Tension-type headaches are produced by an interaction of peripheral and central processes. Peripheral mechanisms may be most important in episodic headaches, while central processes dominate in chronic cases. Trigeminal nerve involvement is found in chronic tension-type headache, linking it to the broader neurovascular system.

Vascular headaches may be triggered by a hypothesized hypothalamic headache generator. Classic migraines, which involve prodromal symptoms, are preceded by spreading cortical depression. Breakthrough headaches precede and are worsened by the dilation of cranial blood vessels. The trigeminal nerve serves as a final common path for headache pain, though the mechanisms responsible for cluster and migraine headaches appear to differ.

The mechanism by which temperature biofeedback impacts migraine has been questioned, especially by research showing that the direction of temperature training does not affect treatment outcome. Research in Raynaud's disease has yielded unexpected benefits for the field of biofeedback. We have learned that hand-warming and hand-cooling involve separate mechanisms and that temperature biofeedback may not reduce sympathetic activation. Raynaud's research has also supported the local fault model and challenged the traditional model that effective treatment reduces sympathetic arousal.

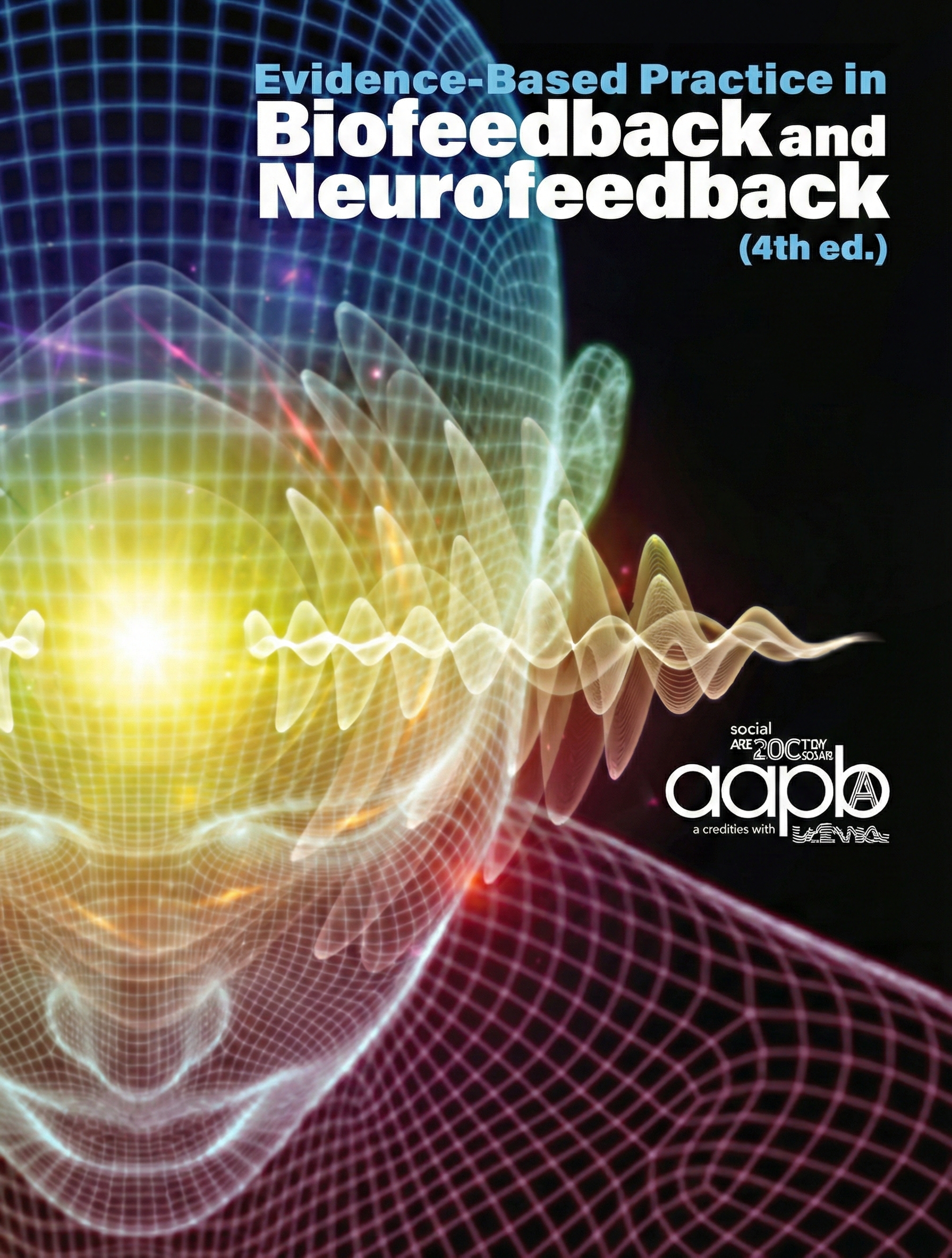

Since the release of Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (3rd ed.), there has been stronger evidence of biofeedback efficacy for low back pain, pediatric headache, and repetitive strain injury.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses Chronic neuromuscular pain (IV-C), General treatment considerations (IV-D), Target muscles, typical electrode placements, and SEMG treatment protocols (IV-E), and Pathophysiology, biofeedback modalities, and treatment protocols for specific ANS biofeedback applications (V-D).

This unit covers Tension-Type Headache, Vascular Headache, Raynaud's Disease and Phenomenon, Low Back Pain, Myofascial Pain, Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD), Cervical Injury, Workplace Ergonomic Applications, and Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS).

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter Lecture

Evidence-Based Practice (4th ed.)

We have updated the efficacy ratings for clinical applications covered in AAPB's Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

Tension-Type Headache: The Most Common Primary Headache

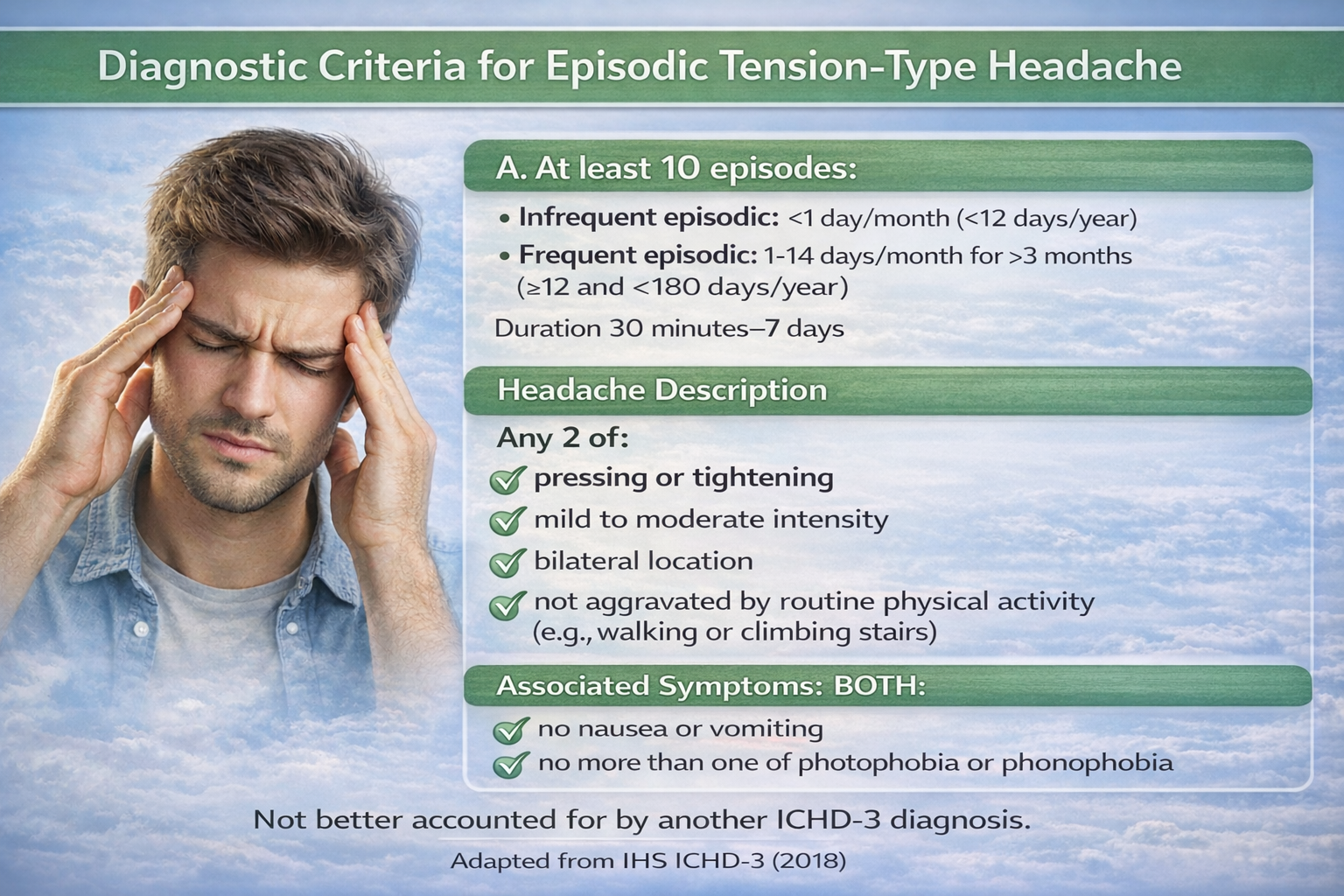

Tension-type headache (TTH) is characterized by a steady, nonthrobbing pain that may involve the frontotemporal vertex or occipito-cervical areas with a lateral or bilateral distribution. This headache has a duration of 30 minutes to 7 days.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Tension-Type Headache Overview

Demographics

TTH is the most common primary headache. A 2022 global analysis estimated the prevalence of TTH at approximately 26% of the worldwide population (Stovner, Hagen, Linde, & Steiner, 2022). The Global Burden of Disease 2023 study confirmed TTH as a leading cause of years lived with disability, with prevalence remaining stable over the past three decades (GBD 2023 Headache Collaborators, 2025).

TTH onset frequently occurs during adolescence and early adulthood, with prevalence peaking between ages 30 and 39 in both sexes. There is a female predominance, with women consistently experiencing higher rates than men across all age groups, and the disability burden from TTH is more than twice as high in females compared to males (Steiner & Stovner, 2025).

Episodic Versus Chronic Tension-Type Headaches

TTH is divided into episodic and chronic headache. Episodic TTH is diagnosed when the patient has at least 10 previous headaches, fewer than 15 days per month, and no evidence of a secondary headache disorder.

Chronic TTH is diagnosed when there is an average headache frequency of more than 15 days per month for more than 6 months (Martin & Elkind, 2005).

Physiology of Tension-Type Headache

The consensus view is that tension-type headaches are produced by an interaction of peripheral and central processes (Ashina, Bendtsen, & Ashina, 2005; Chen, 2009). Central sensitization appears to play a crucial role, particularly in chronic TTH cases. A 2025 comprehensive review confirmed that patients with episodic TTH demonstrate higher levels of peripheral excitability, while those with chronic TTH show clear manifestations of central sensitization (Pan et al., 2025).

Central sensitization involves increased excitability of the central nervous system, triggered by repetitive and sustained pericranial myofascial input. These changes may produce sympathetic nervous system activation that increases muscle contraction by shortening muscle spindles and constricting their blood supply (Ashina et al., 2002; Khazan, 2013). Functional MRI studies have identified involvement of cortical regions including the cingulate cortex, prefrontal cortex, insular cortex, thalamus, and cerebellum (Shah, Asuncion, & Hameed, 2024).

Peripheral mechanisms are thought to be more prominent in episodic TTH, including myofascial pain, tenderness, and increased muscle hardness in pericranial areas. Myofascial trigger points have been implicated in TTH pathogenesis and are considered important treatment targets (Shah et al., 2024). In chronic TTH, these muscular changes may become more permanent (Bhoi, Jha, & Chowdhury, 2021). However, the exact relationship between muscle tension and TTH remains controversial, as EMG studies often fail to detect increased resting muscle tension in TTH patients (Millea & Brody, 2002).

Neurotransmitters such as nitric oxide, CGRP, substance P, neuropeptide Y, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide are involved in pain processing and may contribute to TTH pathophysiology (Ashina, 2004). Unlike migraine, where CGRP-targeted medications have revolutionized treatment, evidence for CGRP involvement in TTH remains limited (Lee et al., 2024). Almost two-thirds of TTH patients exhibit elevated SEMG activity in the cervical paraspinal, upper trapezius, frontalis, and temporalis muscles at baseline and during stressful tasks (Hatch et al., 1992).

Forehead and Pericranial Muscle SEMG Assessment

Recent studies have shown that tension-type headache patients have higher SEMG levels than healthy controls. Researchers have monitored frontalis, occipitalis, temporalis, and trapezius muscles to study the role of muscle activity in tension-type headache.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: SEMG Findings for Tension-Type Headache

A frontalis or bifrontal placement is illustrated below.

A cervical paraspinal placement is indicated below.

An FpN placement involves an active electrode over a frontalis muscle and another over a cervical paraspinal muscle on the same side below the hairline (Schwartz & Andrasik, 2003). A clinician could simultaneously monitor two FpN channels: left frontalis-left cervical paraspinal and right frontalis-right cervical paraspinal.

Hudzinski and Lawrence (1988) reported that both right- and left-sided FpN (frontalis and posterior neck) placements significantly discriminated between chronic tension-type headache patients when they had a headache and when they were headache-free. Schoenen and colleagues (1991) reported higher left frontalis, temporalis, and trapezius muscles during reclining, standing, and math stressor conditions (62.5% of patients exceeded 2 standard deviations).

Studies of tension-type headache patients have not consistently shown elevated SEMG activity during headache episodes, compared with when they are headache-free. One study found that frontal SEMG levels were significantly lower during a tension-type headache (Hatch et al., 1992). The inconsistency among studies may be due to differences in recording sites, positions, tasks, and patient characteristics.

Biofeedback Treatment of Tension-Type Headache

The design of a treatment protocol should be based on the clinical outcome literature for the population you are treating, whether children, adults, or elderly, and the findings of a psychophysiological profile that examines multiple response systems during resting, stress, and recovery conditions. Tailor treatment to your patient's unique response stereotypy.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Tension-Type Headache Treatment Components

Several treatment components should be considered: frontal SEMG biofeedback, masseter SEMG biofeedback, temporalis SEMG biofeedback, trapezius SEMG biofeedback, temperature biofeedback, relaxation training, and cognitive behavior therapy. Complementary treatment components include heat packs and diathermy, ice packs, massage, prescription muscle relaxants like Zanaflex (Tizanidine), and physical therapy exercises to increase range of motion.

Consider Margaret, a 35-year-old marketing executive who experiences tension-type headaches three to four times per week. Her psychophysiological profile reveals elevated trapezius SEMG during a mental arithmetic stressor with slow recovery. Her treatment plan includes trapezius SEMG biofeedback combined with relaxation training. After 10 sessions, her headache frequency decreased by 60%, and she reports using these skills during stressful work meetings.

Pediatric Headache

A meta-analysis by Stubberud, Varkey, McCrory, Pedersen, and Linde (2016) examined five RCTs with 137 participants and found that biofeedback significantly reduced migraine frequency (mean difference -1.97 attacks), attack duration, and headache intensity compared to wait-list controls. Treadwell and colleagues' (2025) comprehensive systematic review confirmed that for children and adolescents, the combination of cognitive behavioral therapy, biofeedback, and relaxation training reduces both migraine attack frequency and disability more effectively than education alone. These findings support biofeedback as a first-line nonpharmacological intervention for pediatric headache.

Clinical Efficacy for Pediatric Headache

Based on at least two independent RCTs and several quasi-experimental studies, Ethan Benore (2023) rated biofeedback for pediatric headache as efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

Adult Headache Treatment Findings

A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis by Paudel and Sah analyzed nine RCTs with 558 participants and confirmed that biofeedback significantly reduces headache frequency and severity compared to waiting-list controls, though it showed no significant difference compared to pharmacotherapy or cognitive behavioral therapy. Importantly, biofeedback improved migraine-related disability, depression, anxiety, and quality of life.

The authors noted potential synergistic benefits when biofeedback is combined with pharmacotherapy and called for research on cost-effectiveness and accessibility of home-based and app-based biofeedback.

Hudzinski (1993) recommended that clinicians use both frontal and neck placements. Down-training neck muscles may be necessary in treating tension-type and migraine headaches for two reasons. First, contraction of these muscles may help trigger a headache episode. Second, neck muscles often contract following a breakthrough headache to reduce head movement and the pain that it might cause.

A combination of frontal and neck placements may provide clients with more information. Clinicians should be aware that neither the frontal nor neck placements represent other muscle sites and that reductions at either of these sites may not generalize to other muscle groups.

Nestoriuc, Martin, Rief, and Andrasik (2008) reported a sizeable average effect size (69% success rate) for EMG biofeedback compared to 31% improvement in untreated control groups in their meta-analysis. This landmark meta-analysis remains influential and established biofeedback's efficacy rating of level 4 (efficacious) for migraine and level 5 (efficacious and specific) for tension-type headache.

Tension-type headache arises from peripheral and central mechanisms, with central sensitization playing a key role in chronic cases. SEMG biofeedback targeting frontalis, trapezius, and cervical paraspinal muscles can produce lasting relief. Treatment should be tailored to individual psychophysiological profiles, and combining biofeedback with cognitive-behavioral strategies enhances outcomes.

Comprehension Questions: Tension-Type Headache

- What distinguishes episodic from chronic tension-type headache, and why does this distinction matter for treatment planning?

- How does central sensitization contribute to the persistence of chronic tension-type headache?

- Why might SEMG biofeedback at the frontalis site not generalize to other muscle groups involved in TTH?

- What advantages does combining biofeedback with cognitive-behavioral therapy offer for headache treatment?

Vascular Headache: Migraine and Cluster Headache

Migraine is classified into migraine without aura (common migraine) and migraine with aura (classic migraine).

About 80% of migraines are migraine without aura.

Migraine with aura includes recurrent headaches lasting 4-72 hours with unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate-to-severe intensity, and aggravation by physical activity, along with nausea, photophobia, and phonophobia. The aura includes reversible visual, sensory, and speech disturbances. Common migraine involves identical symptoms but without the aura, which are neurological symptoms preceding the breakthrough headache (Launer et al., 1999; Elkind, 2005).

Migraine equivalents are prodromes without headaches. Migrainous infarction (complicated migraine) involves less than 1-2% of migraineurs. It includes hemiplegic, ophthalmoplegic, and basilar migraine. Complicated migraine is a vascular headache with neurologic symptoms that often follow a definite sequence. In severe cases, permanent neurologic deficits may follow the attack (Diamond & Dalessio, 1986).

Baskin (2014) observed that a migraine patient's brain is more vulnerable to psychiatric disorders. They are 5.8 times more likely to develop depression. Depression complicates treatment because depressed migraine patients are 3 times less likely to adhere to treatment and show a reduced response to both medication and behavioral interventions. Anxiety generally precedes the onset of episodic migraine and may complicate migraine treatment more than depression. Episodic migraine can transform into a chronic headache with sleep disorder and anxiety.

Overuse of rescue medication can result in medication-overuse headache (MOH), the most common secondary headache disorder. MOH develops when patients with migraine or tension-type headache use acute pain medications on 10 or more days per month (for triptans, opioids, and combination analgesics) or 15 or more days per month (for simple analgesics) for at least three months (Citraro & Bhatt, 2024).

A 2025 network meta-analysis of 16 RCTs involving 3,000 participants found that withdrawal of the overused medication, combined with CGRP-targeting preventive therapies, produced the greatest reductions in monthly headache days (Koonalintip et al., 2025). Withdrawal typically worsens headaches for 2-10 days, with associated symptoms including nausea, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and restlessness.

Complete withdrawal has proven more effective than restricted intake, with 50-70% of patients reverting to an episodic headache pattern after successful detoxification (Koonalintip et al., 2024).

Sleep Disorders and Migraine Comorbidity

Sleep disorders and migraine share a bidirectional relationship—poor sleep exacerbates migraine while migraine disrupts sleep. Approximately 87% of migraine patients report at least one sleep problem, with insomnia being the most prevalent (Rains, 2018; Nesbitt, 2024). The hypothalamus, which functions as a migraine generator, also regulates sleep-wake cycles, providing a neurobiological basis for this comorbidity.

A 2025 systematic review confirmed that patients with chronic migraine presenting for treatment have insomnia in the majority of cases, and the presence of insomnia is associated with increased headache frequency, intensity, and risk of chronification (Vgontzas, 2025).

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) has emerged as a promising adjunctive treatment for migraine patients with comorbid insomnia. A sequential Bayesian analysis showed that CBT-I decreased headache frequency by 6.2 days per month more than control conditions in patients with chronic migraine (Cevoli et al., 2020). Clinicians should screen migraine patients for insomnia and consider behavioral sleep interventions as part of comprehensive headache management.

Dietary triggers are commonly reported by migraine patients, though the evidence supporting specific foods as triggers is more limited than often assumed. Self-report studies suggest that 12-60% of migraine patients identify certain foods as triggers, with alcohol (particularly red wine), chocolate, caffeine, aged cheese, MSG, nitrate-containing processed meats, and tyramine-rich foods most frequently implicated (Nguyen & Schytz, 2024).

However, a 2024 systematic review found that prospective studies show low positive predictive values for patient-reported food triggers, indicating that suspected dietary triggers often fail to precipitate attacks when tested under controlled conditions. The relationship between diet and migraine remains complex and individualized, and clinicians should be cautious about recommending overly restrictive elimination diets, which may inadvertently increase patient stress.

The prevalence of migraine in the United States has remained remarkably stable over the past three decades, affecting approximately 12% of adults overall, with rates of 17-19% in women and 6-7% in men (Cohen et al., 2024). This means roughly 39 million Americans experience migraine. Globally, migraine affects approximately 14-15% of the population.

The World Health Organization classifies headache disorders among the top three most common neurological conditions starting at age 5 and remaining in the top three until age 80 (WHO, 2025). Prevalence is highest among women of childbearing age (18-44 years), where the 3-month prevalence reaches 23.5%. While prevalence has remained stable, migraine-related disability appears to be increasing. Depression is 5.8 times more likely in migraine patients, and depressed patients are 3 times less likely to adhere to treatment (Baskin, 2014).

Cluster Headache

Cluster headache (CH) episodes start abruptly without prodromes, 2 to 3 hours after falling asleep. They feature intense, throbbing, unilateral pain involving the eye, temple, neck, and face for 15 to 90 minutes. A typical pattern is one headache every 24 hours for 6-12 weeks followed by 12 months of remission (Diamond & Dalessio, 1986; Martin & Elkind, 2005).

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Cluster Headache Overview

The prevalence of CH in the United States is estimated at 2-9% of migraine prevalence. The male-to-female ratio has shifted considerably from the 6:1 ratio reported in the 1960s to approximately 2:1 today, reflecting improved recognition of the disorder in women. Women are more likely to experience cluster headache onset earlier than men and may experience a second increase in frequency after age 50 (Blanda, 2015).

Hypothalamic Headache Generator

Emerging evidence implicates the hypothalamus as a central generator in primary headache disorders, notably migraines and cluster headaches. Functional neuroimaging studies have consistently demonstrated activation of the hypothalamus during headache episodes, suggesting its pivotal role in both the initiation and modulation of these conditions (Burstein et al., 2019; Schulte & May, 2016). Recent neuroimaging demonstrates premonitory hypothalamic activation hours before pain onset (Mathew et al., 2025).

In migraines, the hypothalamus is believed to contribute to the prodromal phase, characterized by symptoms such as altered mood, fatigue, and food cravings. These premonitory symptoms are thought to result from hypothalamic dysfunction affecting homeostatic processes (Giffin et al., 2003).

The subsequent activation of the trigeminovascular system leads to the headache phase, with the hypothalamus modulating pain sensitivity and autonomic responses (Schulte & May, 2016). The trigeminal ganglion releases neuropeptides including CGRP, substance P, and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP), which have become key therapeutic targets (Gao, Zhao, Tu, & Liu, 2024).

Cluster headaches exhibit a striking circadian rhythmicity, with attacks often occurring at the same time each day, pointing to involvement of the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus. Positron emission tomography scans have revealed activation of the posterior hypothalamus during cluster headache attacks (May et al., 1998). The hypothetical mechanism involves dysregulation that leads to abnormal activation of the trigeminovascular system, release of vasoactive neuropeptides, neurogenic inflammation, and sensitization of central pain pathways (Burstein et al., 2019).

Key Differences Between Migraine and Cluster Headache Pathomechanics

Migraine and cluster headache differ in several key ways. Cluster headaches exhibit a unique circadian and circannual rhythm, often occurring at the same time each day or during specific seasons, suggesting stronger hypothalamic involvement. While both may present with autonomic features, they are far more prominent in cluster headaches, manifesting as ipsilateral conjunctival injection, lacrimation, nasal congestion, or ptosis.

The quality and duration of pain also differ markedly. Migraine pain is characteristically throbbing or pulsating, often worsening with physical activity, and typically persists for 4 to 72 hours if untreated. Cluster headache pain is non-throbbing, extremely severe, often described as burning or piercing, and usually lasts between 15 minutes to 3 hours.

Finally, the behavioral response to attacks varies significantly. During a migraine, sufferers typically seek a quiet, dark environment and prefer to lie still. In stark contrast, individuals experiencing a cluster headache often become restless and agitated, frequently pacing or rocking back and forth in an attempt to alleviate the pain.

Physiology of a Vascular Headache

The trigeminal nerve may be activated in all primary headaches, including cluster, migraine, and tension-type. A neurovascular theory of migraine based on imaging studies has replaced the poorly supported vascular theory of the 1940s that proposed that migraines are due to blood vessel dilation.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Neurovascular Theory of Headache

The neurovascular theory hypothesizes that migraine sufferers are vulnerable to cortical hyperexcitability, especially in the occipital cortex. A wave of cortical spreading depression (CSD), which involves a slowly propagating reduction in cortical neural activity, produces the aura.

The release of trigeminal peptides like calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P dilates cerebral blood vessels and produces neurogenic inflammation. CGRP is now recognized as a pivotal player in migraine pathophysiology; intravenous CGRP infusion reliably triggers migraine attacks in susceptible individuals (Ashina et al., 2025; Frimpong-Manson et al., 2024).

Between 2018 and 2025, four CGRP monoclonal antibodies (erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab) and three small-molecule CGRP receptor antagonists called gepants (ubrogepant, rimegepant, atogepant) received approval. Approximately half of treated patients achieve a 50% or greater reduction in monthly migraine days (Ashina et al., 2025).

Consider David, a 28-year-old software developer who experiences classic migraines with visual aura about twice monthly. His migraines typically begin with zigzag lines in his visual field, followed 30 minutes later by severe unilateral throbbing headache with nausea and light sensitivity. Temperature biofeedback combined with stress management training helped him identify prodromal symptoms earlier and intervene before headaches became severe. After 12 sessions, his migraine frequency decreased by 50%, and he reported feeling more in control of his condition.

Biofeedback Treatment of Migraine

Both hand-warming and hand-cooling biofeedback have effectively reduced migraine headaches. Blanchard and colleagues (1997) found no difference in headache reduction between subjects trained to raise versus lower skin temperature. These results and direct cardiovascular measures have led researchers to question why temperature biofeedback works for migraines.

Temperature biofeedback may reduce headaches by teaching patients to relax and to alter blood volume pulse in cranial blood vessels. The temperature training mechanism is not settled. Neurofeedback is increasingly a treatment component for migraine. Walker (2011) reported that QEEG-guided neurofeedback reduced the frequency of recurrent migraine headaches.

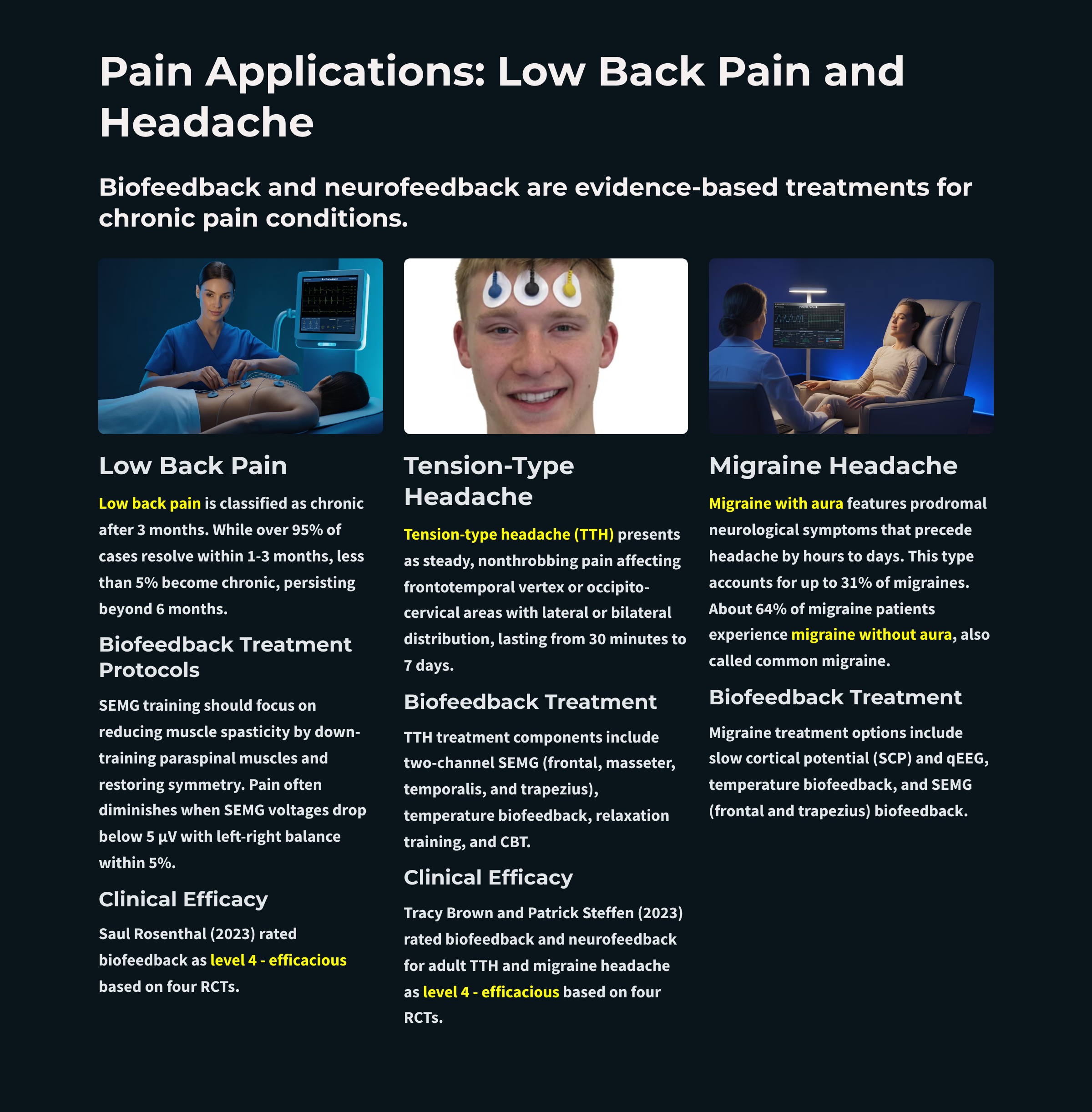

Clinical Efficacy for Migraine and TTH

Based on eight RCTs, Tracy Brown and Patrick Steffen (2023) rated biofeedback for adult headache as level 4 efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). The biofeedback modalities included EMG, HRV, neck pressure, TEMP, and vasoconstriction/vasodilation biofeedback. Biofeedback outcomes included reduced headache frequency and severity, medication, and performance loss.

Vascular headaches involve complex neurovascular mechanisms with the hypothalamus serving as a potential generator. The trigeminal nerve is a final common pathway for headache pain. Biofeedback, particularly temperature training and neurofeedback, provides effective treatment options, with research supporting efficacy ratings at the highest levels. The mechanism of temperature biofeedback's effectiveness remains an active area of investigation.

Comprehension Questions: Vascular Headache

- How do the periodicity and autonomic symptoms of cluster headache differ from migraine?

- What role does the hypothalamus play as a headache generator, and how does neuroimaging support this hypothesis?

- Why has the neurovascular theory replaced the older vascular theory of migraine?

- What is puzzling about the finding that both hand-warming and hand-cooling biofeedback reduce migraines?

Raynaud's Disease and Phenomenon: Understanding Vasospastic Disorders

Raynaud's phenomenon (RP) is characterized by episodic narrowing (vasospasm) of blood vessels, typically in the fingers and toes, triggered by cold temperatures or emotional stress. This vasospasm creates the classic triphasic color changes: pallor (white) when vasoconstriction creates a bloodless state, cyanosis (blue) when blood pools and loses oxygen, and rubor (red) during the reactive hyperemia phase when oxygenated blood rushes back into tissues.

RP is classified as primary RP (Raynaud's disease) when it occurs without an identifiable underlying disorder, accounting for more than 80% of cases, or secondary RP when linked to underlying diseases such as autoimmune disorders like scleroderma, vascular diseases, or certain medications (Musa & Qurie, 2023).

Mechanism: The Local Fault Hypothesis

The pathogenesis of primary Raynaud's has been a subject of considerable research. While earlier theories emphasized sympathetic nervous system overactivity, current evidence strongly supports the local fault hypothesis, which proposes that Raynaud's symptoms are largely driven by abnormalities at the level of the digital arteries themselves rather than excessive sympathetic outflow (Freedman, 1995; Wigley & Flavahan, 2016).

The local fault involves hypersensitivity of alpha-2C-adrenergic receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells. These receptors are uniquely temperature-sensitive and normally reside intracellularly. Upon cooling, a complex mechanism involving mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and the Rho/ROCK signaling pathway triggers translocation of these receptors to the cell surface, where they become available to respond to norepinephrine (Eid, 2016).

In patients with primary RP, this cold-induced receptor mobilization and sensitivity is exaggerated, producing vasospasm even at temperatures that would not trigger attacks in healthy individuals.

The dual defect model proposes that cold both increases sympathetic outflow and primes local alpha-2-adrenergic receptors, creating a permissive environment for vasospasm. A 2024 genome-wide association study identified significant associations with the ADRA2A gene (encoding the alpha-2A-adrenergic receptor), providing genetic support for the adrenergic hypothesis (Lane et al., 2024). The higher prevalence of RP in premenopausal women (approximately 3-4 times more common than in men) may relate to the influence of 17β-estradiol on receptor sensitivity.

Biofeedback Treatment of Raynaud's

Temperature biofeedback has been a cornerstone of behavioral treatment for Raynaud's phenomenon. The most effective protocol is temperature biofeedback under cold challenge, where clients learn to maintain peripheral temperature while the affected limb is exposed to cooling (Freedman, Ianni, & Wenig, 1983). This approach produces better outcomes than temperature biofeedback alone because it trains the specific skill needed to counteract real-world triggers.

Interestingly, research on Raynaud's has yielded important insights for the broader field of biofeedback. Studies demonstrating that hand-warming and hand-cooling involve separate mechanisms, and that temperature biofeedback may not necessarily reduce sympathetic activation as originally theorized, have challenged traditional assumptions about how thermal biofeedback works (Freedman & Ianni, 1983).

The success of temperature biofeedback in Raynaud's appears to operate through local vascular mechanisms rather than central sympathetic inhibition.

Clinical Efficacy

Based on eight RCTs, Fred Shaffer and Zachary Meehan (2023) rated biofeedback for RP as level 4 efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). TBF will not reduce the frequency of Raynaud's attacks unless patients learn to increase hand temperature (Yucha, 2016).

Raynaud's phenomenon involves exaggerated cold-induced vasoconstriction, now understood to result primarily from local vascular abnormalities rather than sympathetic overactivity. The local fault hypothesis, supported by genetic evidence implicating alpha-adrenergic receptor genes, explains the hypersensitivity of digital arteries to cold. Temperature biofeedback under cold challenge is the most effective behavioral treatment, training patients to maintain peripheral circulation during the very conditions that trigger attacks.

Comprehension Questions: Raynaud's Disease and Phenomenon

- How does the local fault hypothesis challenge the traditional sympathetic overactivity model of Raynaud's?

- Why is temperature biofeedback under cold stress more effective than temperature biofeedback alone?

- What criteria should be used to determine when a patient has acquired the vasodilation response?

- How do the pathomechanisms of primary and secondary RP differ?

Low Back Pain: A Major Cause of Disability

Clinicians classify low back pain as chronic after 3 months since connective tissue usually heals within 6-12 weeks (Wheeler, 2014). While more than 95% of low back pain cases are acute and improve within 1 to 3 months of therapy, under 5% of cases are chronic and do not resolve within 6 months (Sella, 2003).

Chronic low back pain may involve paravertebral muscle misuse causing ligament strain, muscle tear, spinal facet injury, disk prolapse (protrusion), and psychological processes.

The Biopsychosocial Model of Chronic Pain

The biopsychosocial model provides the most comprehensive framework for understanding chronic pain, including low back pain. Pioneered by researchers including Dennis Turk, this model recognizes that chronic pain emerges from a dynamic interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors rather than from tissue damage alone (Gatchel, Peng, Peters, Fuchs, & Turk, 2007; Nicholas, 2022).

Biological factors include genetics, tissue injury, central sensitization, and endogenous pain modulation. Psychological factors encompass mood, cognitions, coping styles, and pain catastrophizing. Social factors involve family relationships, workplace demands, cultural influences, and healthcare access (Turk & Monarch, 2018).

A critical insight from the biopsychosocial perspective is that treatment goals should focus on improving function and quality of life rather than achieving zero pain. Complete eradication of chronic pain is often an unrealistic expectation, and pursuing it as a primary goal can lead to patient frustration, depression, and overreliance on medications (Indian Health Service, 2023).

As Nicholas (2022) emphasized in his 40-year reappraisal of the model, effective pain management helps patients develop skills to manage their condition day-to-day, even when pain persists.

Key Clinical Principle: Pain cannot be objectively measured—it remains a subjective experience that must be assessed through patient self-report (Eldabe et al., 2022). Unlike blood pressure or blood glucose, no laboratory test, imaging study, or biomarker can quantify a patient's pain intensity. The measurement of pain relies on subjective self-reported scales, which means clinicians must believe and respect patient reports even when objective findings are absent.

The Imaging-Pain Disconnect

One of the most challenging aspects of chronic low back pain is that structural imaging often fails to identify the source of pain. MRI and CT findings correlate poorly with symptoms—disc abnormalities such as bulging discs or degenerative disc disease appear in up to 97% of asymptomatic individuals (Hall, Aubrey-Bassler, Thorne, & Maher, 2021). A 2023 systematic review confirmed that MRI findings demonstrate only weak associations with future low back pain (Han et al., 2023).

This disconnect explains why guidelines recommend against routine imaging for uncomplicated low back pain—patients who receive unnecessary imaging often have delayed recovery, greater healthcare utilization, and are more likely to undergo surgery without improved outcomes (Hall et al., 2021).

When structural imaging cannot confirm a patient's pain complaint, healthcare providers may express skepticism or disbelief. Research documents that chronic pain patients frequently experience pain dismissal—having their pain disbelieved, ignored, or diminished by healthcare providers (Brown et al., 2024). A 2025 U.S. Pain Foundation survey found that 62% of chronic pain patients waited more than a year to receive a diagnosis, and many reported feeling stigmatized (U.S. Pain Foundation, 2025).

Such experiences damage the therapeutic relationship and can cause patients to avoid seeking care. Clinicians should understand that many chronic pain conditions involve functional rather than structural pathology—specifically, alterations in central nervous system pain processing that do not produce visible tissue damage.

Clinicians often observe a cycle of injury, protective bracing, and chronic contraction that produces muscle asymmetry and a restricted range of motion.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Low Back Pain Overview

Apkarian and colleagues (2004) reported that chronic low back pain could produce atrophy of the prefrontal cortex and impair judgment on the Iowa Gambling Test.

Demographics

Low back pain is the leading cause of disability worldwide, affecting approximately 619 million people globally in 2020, with projections suggesting this number will rise to 843 million by 2050 (Lancet Rheumatology, 2023). In the United States, back pain is the most prevalent pain site, affecting 39% of adults during any 3-month period (Lucas, Connor, & Bose, 2021).

A 2022 survey found that approximately 28% of U.S. adults reported chronic low back or sciatic pain. While more than 95% of low back pain cases are acute and resolve within 1 to 3 months, fewer than 5% become chronic and persist beyond 6 months (Sella, 2003). Men and women report comparable rates of low back pain, though women report this disorder more frequently than men after age 60 (Wheeler, 2014). The economic burden is substantial, with low back and neck pain costing $134 billion annually in the United States.

Spinal Nerves

The spinal cord is divided into 31 pairs of spinal nerves that arise at regular intervals: cervical nerves (C1-C8) in the neck region, thoracic nerves (T1-T12) in the chest region, lumbar nerves (L1-L5) in the lower back region, sacral nerves (S1-S5) at the sacrum, and coccygeal nerves (1 pair) near the coccyx.

The Anatomy of Thoracic, Lumbar, and Sacral Spine-Associated Muscles

The muscles that move the vertebral column (backbone) have diverse origins and insertions, extend in different directions, and are layered on top of each other. The muscles of primary interest include the trapezius in the upper back and the lower back's erector spinae.

The trapezius, the most superficial back muscle, is a triangular muscle sheet covering the posterior neck and superior trunk. The two trapezius muscles form a trapezoid. The upper trapezius elevates the scapula (shoulder blade) and helps extend the head.

The erector spinae, the largest back muscle, is located on both sides of the spine and consists of three muscle groups: iliocostalis group (iliocostalis cervicis, iliocostalis thoracic, and iliocostalis lumborum), longissimus group (longissimus capitis, longissimus cervicis, and longissimus thoracis), and spinalis group (spinalis capitis, spinalis cervicis, and spinalis thoracis).

The erector spinae is the primary muscle that extends the vertebral column and plays an essential role in its flexion, lateral flexion, and rotation. Place SEMG electrodes vertically just above the iliac crest (top of the pelvic girdle) 3 centimeters from both sides of the spine for an erector spinae (L3 paraspinal) placement.

SEMG Assessment

Geisser and colleagues (2005) conducted a meta-analysis of 44 articles that compared patients diagnosed with low back pain (LBP) and healthy controls. For static assessment, standing produced the largest effect size. LBP subjects had higher paraspinal SEMG amplitudes. For dynamic assessment, flexion-relaxation discriminated best between subjects with LBP and normals.

Flexion-relaxation produced a very large effect size, and LBP subjects demonstrated deficient paraspinal SEMG relaxation during terminal flexion. Re-extension after full flexion produced a large effect size.

Consider Robert, a 45-year-old construction worker with chronic low back pain following a lifting injury two years ago. His SEMG assessment reveals elevated bilateral paraspinal activity during standing and absent flexion-relaxation response. His treatment combines SEMG biofeedback to restore the flexion-relaxation response with gradual exercise progression. After 16 sessions, he demonstrates normal flexion-relaxation and reports a 70% reduction in pain intensity.

Active SEMG Training for Low Back Pain

Neblett and colleagues (2003, 2010) developed the Surface EMG-Assisted Stretching and Awareness (SEMG-Assisted-SAT) model for treating chronic low back pain. This approach combines neuromuscular rehabilitation with general relaxation.

Neblett's active SEMG training involves a collaborative process in which the clinician and client share SEMG biofeedback and the client's self-reports to identify patterns of muscle bracing associated with pain and restricted range of motion and evaluate strategies to correct these problems.

The flexion-relaxation phenomenon illustrates this approach. When individuals without low back pain bend forward, their erector spinae muscles stop firing at about 45 degrees. Instead, the posterior ligament, thoracolumbar fascia, and posterior zygapophyseal joint capsules support the spine. When they bend backward (re-extend), their erector spinae restart at about 45 degrees.

In contrast, individuals with chronic low back pain fail to "switch off" their paraspinal muscles during flexion because their muscles are braced to protect the injured spine. This pattern is dysfunctional because constant bracing creates new problems like reduced blood supply and metabolic insufficiency, which can produce ischemic pain and fibrous changes in muscle.

Clinical Efficacy

Sielski, Rief, and Glombiewski's (2017) meta-analysis of 21 studies with 1,062 patients found that biofeedback produced significant small-to-medium effect sizes for pain intensity reduction that remained stable at 8-month follow-up. Biofeedback also reduced depression, disability, and muscle tension, while improving cognitive coping. Longer treatments were more effective for disability reduction, supporting the use of extended biofeedback protocols in comprehensive rehabilitation.

Based on four RCTs, Saul Rosenthal (2023) rated biofeedback for low back pain as level 4 efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). Clinicians trained clients to reduce SEMG and stabilize the trunk and relax (BART). Participants improved on depression, distress, pain intensity, disability, pain cognitions, and muscle activation.

Sleep Disturbance and Chronic Low Back Pain

Sleep disturbance and chronic musculoskeletal pain share a bidirectional relationship. A 2024 systematic review with meta-analysis of 16 prospective longitudinal studies found that sleep problems at baseline increase the risk of developing chronic musculoskeletal pain in both the short term and long term, while chronic pain also elevates the risk of subsequent sleep problems (Runge et al., 2024).

Approximately 50% of individuals with chronic pain experience clinically significant insomnia, and 50% of those with insomnia experience chronic pain (Todd et al., 2022). Sleep deprivation enhances pain sensitivity through mechanisms that include impaired descending pain inhibition, increased inflammatory markers, and alterations in pain-related brain regions. Addressing sleep disturbance is increasingly recognized as an essential component of comprehensive chronic low back pain treatment.

Chronic low back pain often involves a cycle of injury, protective bracing, and chronic muscle contraction. The biopsychosocial model provides the most effective framework for treatment, with goals focused on improving function and quality of life rather than eliminating pain entirely. SEMG assessment during standing and flexion-relaxation movements can identify dysfunction. Imaging findings correlate poorly with symptoms, which may contribute to patient experiences of disbelief from healthcare providers. Active SEMG training helps patients restore normal muscle patterns, particularly the flexion-relaxation response. Combining biofeedback with graduated exercise and cognitive strategies produces optimal outcomes.

Myofascial Pain: Understanding Trigger Points

Myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) is a regional musculoskeletal condition characterized by the presence of trigger points, which are hyperirritable regions of taut bands of skeletal muscle in the muscle belly or associated fascia. Pressure on these areas is painful, and they can produce referred pain and tenderness, motor dysfunction, and autonomic changes.

Travell and Simons (1992) created the definitive trigger point reference. Trigger points are associated with palpable nodules in taut bands of muscle fibers and produce local and referred pain.

Gevirtz (2013) hypothesizes that SNS innervation of muscles spindles may result in trigger points.

Clinical Efficacy

Sherman, Tan, and Wei (2016) rated biofeedback for myofascial pain syndrome as level 2 possibly efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (3rd ed.).

Fibromyalgia: A Pain Amplification Disorder

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic benign pain disorder that involves pain, tenderness, and stiffness in the connective tissue of muscles, tendons, ligaments, and adjacent soft tissue.

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) adult criteria include widespread pain for at least 3 months on both sides of the body and pain during gentle palpation on 11 of 18 tender points on the neck, shoulder, chest, back, arm, hip, and knee sites.

Patients also present with attentional deficits, depression, severe fatigue, headaches, impaired multitasking, irritable bowel syndrome, memory deficits, sleep disturbance, and temporomandibular muscle and joint pain (Donaldson & Sella, 2003; Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

McGrady and Moss (2013) conceptualize FM as a "pain amplification disorder" produced by the twin mechanisms of allodynia and hyperalgesia (p. 187). Allodynia means that patients experience previously benign stimuli as painful. Hyperalgesia means patients experience mildly painful stimuli as severely painful.

The International Association for the Study of Pain has introduced the term nociplastic pain to describe this third category of pain, distinct from nociceptive and neuropathic pain, where altered nociception occurs despite no clear evidence of tissue damage or nervous system lesion (Nijs, Malfliet, & Nishigami, 2023).

Evidence suggests that FM involves defective descending pain modulation, where normal inhibitory pathways that would suppress pain signals are impaired, contributing to widespread pain hypersensitivity (Almeida Silva & Pinto, 2025).

Patients present with multiple tender points, which are distinct from trigger points. Tender points are located at a muscle's insertion (the tendonous attachment to a movable bone) instead of the muscle belly or associated fascia. When compressed, they produce local pain but not the referred pain associated with trigger points. Pressure on tender points may increase overall pain sensitivity.

Demographics

Fibromyalgia affects approximately 2-4% of the global population, with estimates ranging from 4 million to 10 million people in the United States alone (American Academy of Family Physicians, 2023). The global prevalence is approximately 2.7%, with the U.S. prevalence at approximately 3.1% and Europe at 2.5% (Soroosh & Farbod, 2024).

The condition predominantly affects women, who comprise 75-90% of diagnosed cases, with a female-to-male ratio of approximately 3:1. The diagnosis is usually made between ages 20 and 50, though the incidence increases with age such that by age 80, approximately 8% of adults meet diagnostic criteria. Peak prevalence in women occurs between ages 60 and 70. Changes in diagnostic criteria over the past decade have resulted in more patients with chronic pain meeting fibromyalgia criteria (AAFP, 2023).

Anatomy and Physiology

The etiology of fibromyalgia appears to involve a central hypersensitivity to heat, cold, and electrical stimulation (Desmeules et al., 2003). Fibromyalgia patients may have low levels of serotonin, amino acids like tryptophan, and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), and high levels of substance P and ACTH.

Post-COVID Syndrome and Fibromyalgia

Emerging evidence suggests that post-COVID syndrome (PCS), also known as long COVID, frequently includes chronic musculoskeletal pain resembling fibromyalgia. A 2024 study found that 72.2% of PCS patients with musculoskeletal pain met American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia (Khoja et al., 2024). The proposed mechanisms include neuroinflammation, small fiber neuropathy, and central sensitization—pathways that overlap with established fibromyalgia pathophysiology.

Patients with pre-existing chronic pain conditions appear more likely to develop long COVID symptoms. These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive pain assessment in post-COVID patients and suggest that biofeedback interventions targeting autonomic dysregulation may be particularly relevant for this population.

Biofeedback Treatment of Fibromyalgia

At this point, there is no evidence that biofeedback is superior to other mind-body therapies. No randomized controlled trials have shown that biofeedback significantly reduces fibromyalgia symptoms when administered by itself or potentiates the effectiveness of treatments like massage therapy, physical exercise, and physical therapy.

Glombiewski, Bernardy, and Häuser's (2013) meta-analysis of seven RCTs with 321 patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia found that EMG biofeedback was superior to control groups in reducing pain severity, with a large effect size. A 2024 RCT by Sancassiani and colleagues found that heart rate variability biofeedback (HRV-BF) improved perceived energy and functional ability in 64 fibromyalgia patients when added to standard pharmacotherapy (Sancassiani et al., 2024).

Research increasingly includes HRV biofeedback as a treatment component, combined with exercise, cognitive therapies (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy), and interventions to improve sleep habits. The putative mechanism involves improved autonomic balance through enhanced vagal tone (Gevirtz, 2013).

Sleep Disturbance in Fibromyalgia

Sleep disturbance is a hallmark of fibromyalgia, with 60-80% of patients reporting poor sleep quality. Non-restorative sleep associated with frequent awakenings is characteristic of the disorder and is linked to symptom severity. The relationship between disordered sleep and fibromyalgia is bidirectional—sleep problems increase the risk of developing chronic widespread pain, while pain disrupts sleep architecture (Lawson, 2020).

A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis found that cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) significantly improved sleep quality, while also reducing pain, anxiety, and depression (Ho et al., 2025). In contrast, pharmacological approaches showed mixed results. The authors concluded that CBT-I should be considered a first-line treatment for addressing insomnia in individuals with fibromyalgia.

A double-blind crossover study found that suvorexant, an orexin receptor antagonist approved for insomnia, improved sleep time and reduced next-day pain sensitivity in fibromyalgia patients with comorbid insomnia (Roehrs et al., 2020). These findings support the hypothesis that improving sleep quality may directly reduce pain sensitivity in this population.

Clinical Efficacy

Based on one RCT using SEMG biofeedback and two RCTs using theta/SMR neurofeedback, Christopher Gilbert (2023) rated biofeedback for fibromyalgia at level 3 probably efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

Fibromyalgia is a pain amplification disorder involving allodynia and hyperalgesia. Tender points, distinct from trigger points, are located at muscle insertions. SEMG biofeedback has shown large effect sizes for reducing pain severity in meta-analyses. A comprehensive treatment approach combining biofeedback with exercise, cognitive therapy, and sleep interventions produces the best outcomes.

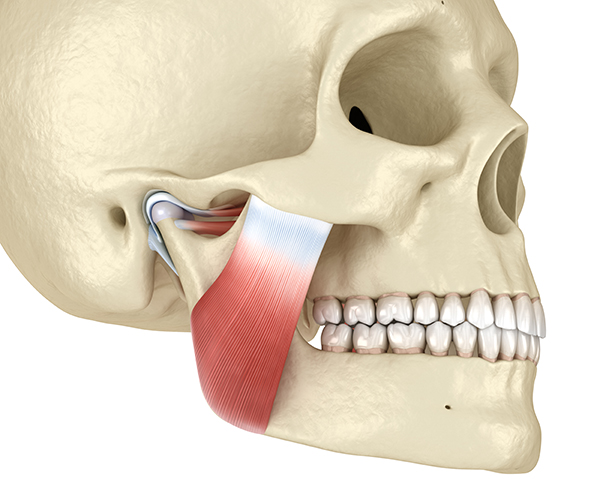

Temporomandibular Disorders: When the Jaw Becomes a Problem

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are the second most common cause of orofacial pain after toothache. Whereas TMD is a heterogeneous group of disorders, orofacial pain and/or masticatory problems may be classified as TMD secondary to myofascial pain and dysfunction (MPD), TMD secondary to articular disease, or both.

Research has demonstrated that the pathophysiology of common painful TMD is biopsychosocial and multifactorial, where no single factor is responsible for its development (Wu et al., 2025). A 2025 network analysis identified two TMD subgroups based on pain mechanisms: a nociceptive subgroup showing restricted jaw opening and response to manual therapy, and a nociplastic subgroup exhibiting higher levels of central sensitization, anxiety, depression, and pain catastrophizing (Asquini et al., 2025).

TMD is characterized by dull pain around the ear, tenderness of jaw muscles, a clicking or popping noise when opening or closing the mouth, limited or abnormal opening of the mouth, headache, tooth sensitivity, and abnormal wearing of the teeth.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: TMD Overview and Treatment

TMD pain is located in the preauricular area, muscles used for chewing (masseter, temporalis, and pterygoids), or the temporomandibular joint.

TMD pain is triggered by parafunctional jaw clenching, which may be unilateral or bilateral in MPD. It is reported along with headache, other facial pain, neck pain, and pain in the shoulder and back.

Glaros and Burton (2004) demonstrated that subjects without TMD, who were trained during 20-minute SEMG biofeedback sessions over 5 consecutive days to increase left and right masseter and temporalis SEMG levels, experienced increased pain at post-treatment. Pain severity was highly correlated with masseter activity.

After completing training, an examiner who was blind to their clinical status diagnosed two SEMG-increase subjects and no SEMG-decrease subjects with TMD pain. Remember, they were pain-free when they started the experiment.

Demographics

A 2024 meta-analysis of 74 studies involving over 172,000 subjects found that approximately 34% of the world population experiences temporomandibular disorders, making TMD more prevalent than previously recognized (Zieliński et al., 2024). Prevalence ranges from 19-47% depending on geographic region, with South America showing the highest rates (47%) and North America the lowest (19.4%).

The age group 18-60 years is most affected by TMD. While TMD has traditionally been reported as predominantly affecting women, recent data show female-to-male ratios ranging from 1.09:1 in Europe to 1.56:1 in South America, suggesting the gender gap may be narrower than historically believed. According to the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, prevalence is between 5-12% when stricter diagnostic criteria are applied (NIDCR, 2024).

Joint and Muscle Anatomy of TMD

The temporomandibular joint uses a "ball and socket" mechanism as it first opens. The condyle rotates within the articular fossa. As it opens wider, the condyle translates over the articular eminence (or dislocates over a protrusion in the upper jaw).

Major muscles and their actions include: the masseter muscles (elevate and retract the mandible), the temporalis muscles (elevate and retract the mandible), the lateral (external) pterygoid muscle (protracts and depresses the mandible and moves it laterally), and the medial (internal) pterygoid muscle (elevates and protracts the mandible and moves it laterally).

A patient should ideally be diagnosed by a dental professional who specializes in TMD. Suppose a dental examination reveals that excessive activity in facial and/or masticatory muscles contributes to TMD. In that case, a bilateral SEMG profile should be completed to determine which muscles should be trained. Training should be conducted bilaterally, with gradual reduction of SEMG activity in the more active and then the less active of left and right muscle sites (left and right masseter).

Clinical Efficacy

A 2025 systematic review and network meta-analysis by González-González and colleagues examined RCTs using biofeedback as treatment for patients diagnosed with TMD according to RDC/TMD or DC/TMD criteria. Although biofeedback did not outperform other interventions in pain intensity reduction, it showed comparable efficacy and may offer additional benefits by promoting self-regulation and psychological resilience (González-González et al., 2025). The authors concluded that biofeedback can be explored as a complementary tool within the biopsychosocial approach to TMD rehabilitation.

Based on three RCTs, Alan Glaros and Richard Ohrbach (2023) rated SEMG biofeedback for TMD pain as level 4 efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

TMD involves jaw pain and dysfunction often caused by parafunctional clenching. Experimental studies confirm that increasing masseter activity can induce TMD in healthy individuals. Bilateral SEMG training targeting the masseter and temporalis muscles can produce lasting relief. Treatment should be conducted in collaboration with a dental professional who specializes in TMD.

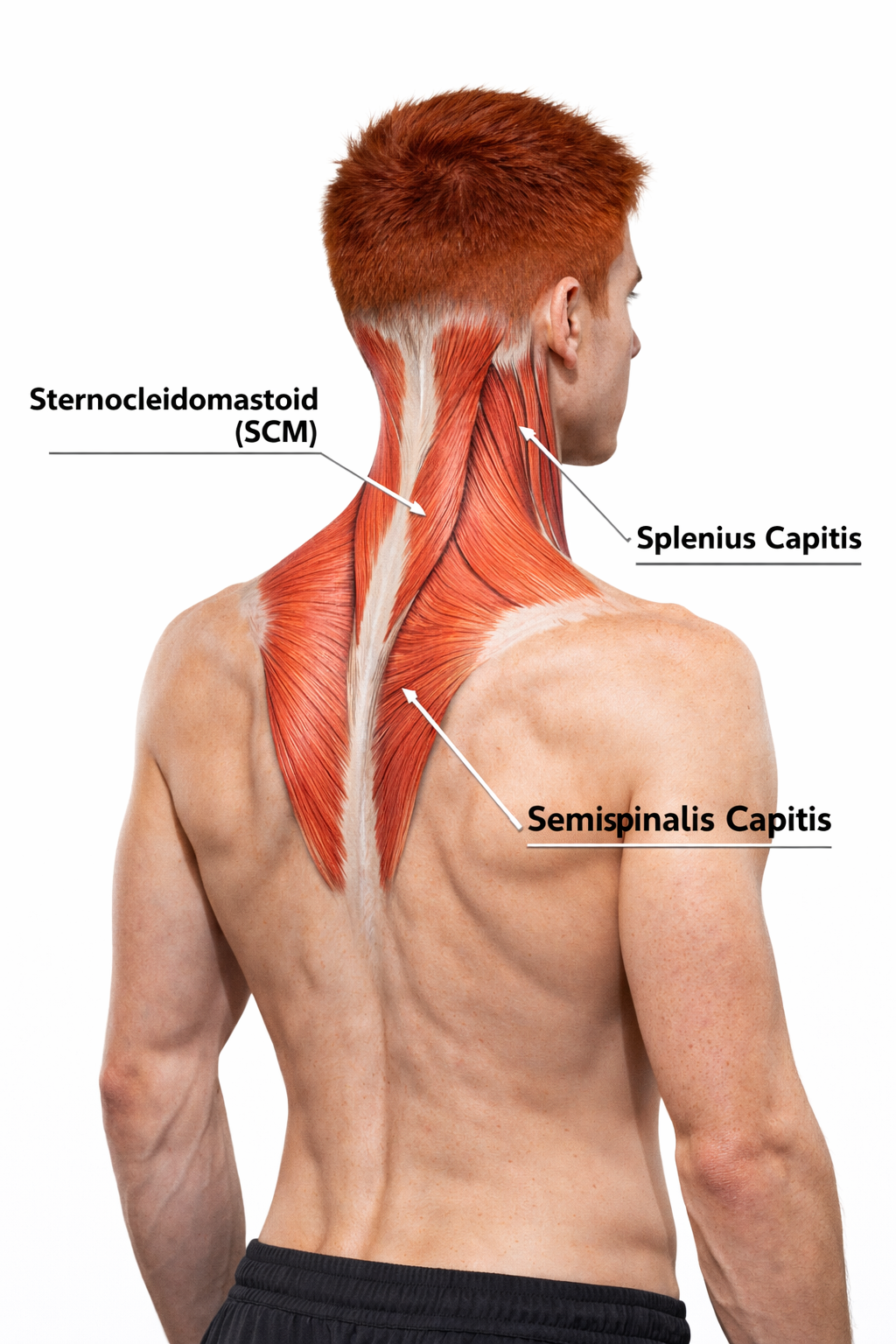

Cervical Injury and Whiplash

The neck, with its complex anatomy of muscles, nerves, and blood vessels, is vulnerable to injuries including those produced by whiplash. Cervical injury often involves the sternocleidomastoid, splenius capitis, semispinalis capitis, levator scapulae, and upper trapezius muscles.

The sternocleidomastoid (SCM) is a muscle that flexes the vertebral column and rotates the head to the opposite side (contract left SCM and head twists to the right). The splenius capitis helps extend the head and rotate the head to the same side as the contracting muscle. The semispinalis capitis helps extend the head and rotates the head to the side opposite the contracting muscle.

Following a cervical injury, the affected structures may recover over 6-12 weeks, which is a normal timetable for soft tissue healing. When symptoms persist, psychological and psychophysiological mechanisms may need to be addressed (Turk & Rudy, 1991).

Clinical Efficacy

Based on four RCTs, Saul Rosenthal (2023) rated biofeedback for cervical pain as level 4 efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

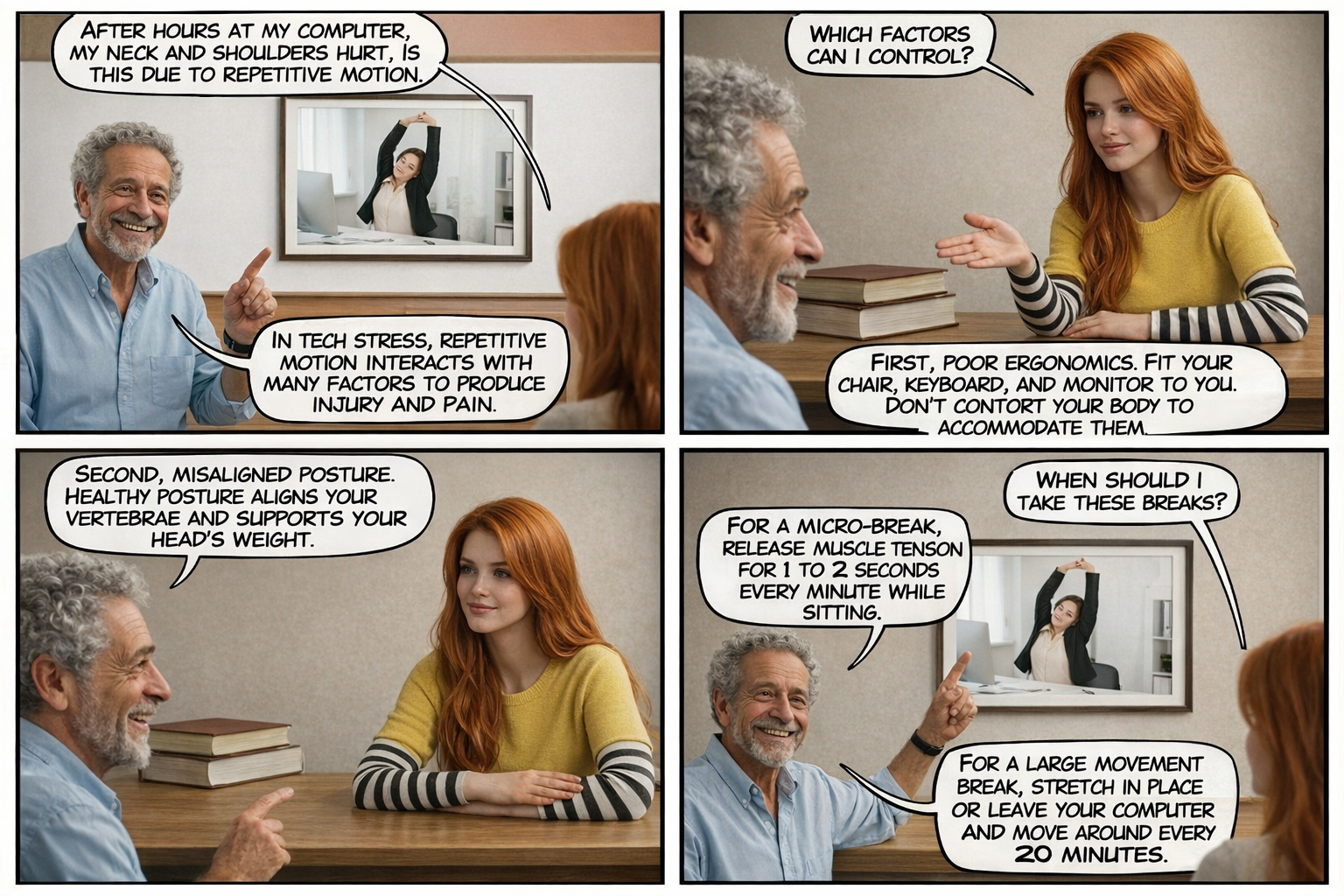

Workplace Ergonomic Applications: Preventing Repetitive Strain Injury

Repetitive strain injury (RSI) is a syndrome that includes diffuse pain in the arm that worsens with activity and features weakness and lack of endurance. These symptoms do not follow nerve and tendon distributions. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) is a painful and disabling example of RSI due to peripheral nerve injury involving inflammation of the tendons that travel through the wrist's carpal tunnel.

Consistent with findings in other chronic pain populations, untrained individuals lack awareness of their muscle tension and breathing pattern. They overuse their muscles and breathe thoracically.

Shumay and Peper (1995) monitored trapezius, deltoid, and forearm muscle SEMG while participants worked at varying distances from the keyboard. They obtained shoulder tension ratings at each keyboard position and found that shoulder tension ratings were not correlated with trapezius and deltoid SEMG. They concluded that since their subjects lacked awareness of small increases and decreases in muscle tension, they could not voluntarily reduce muscle tension, even with an optimal ergonomic setup.

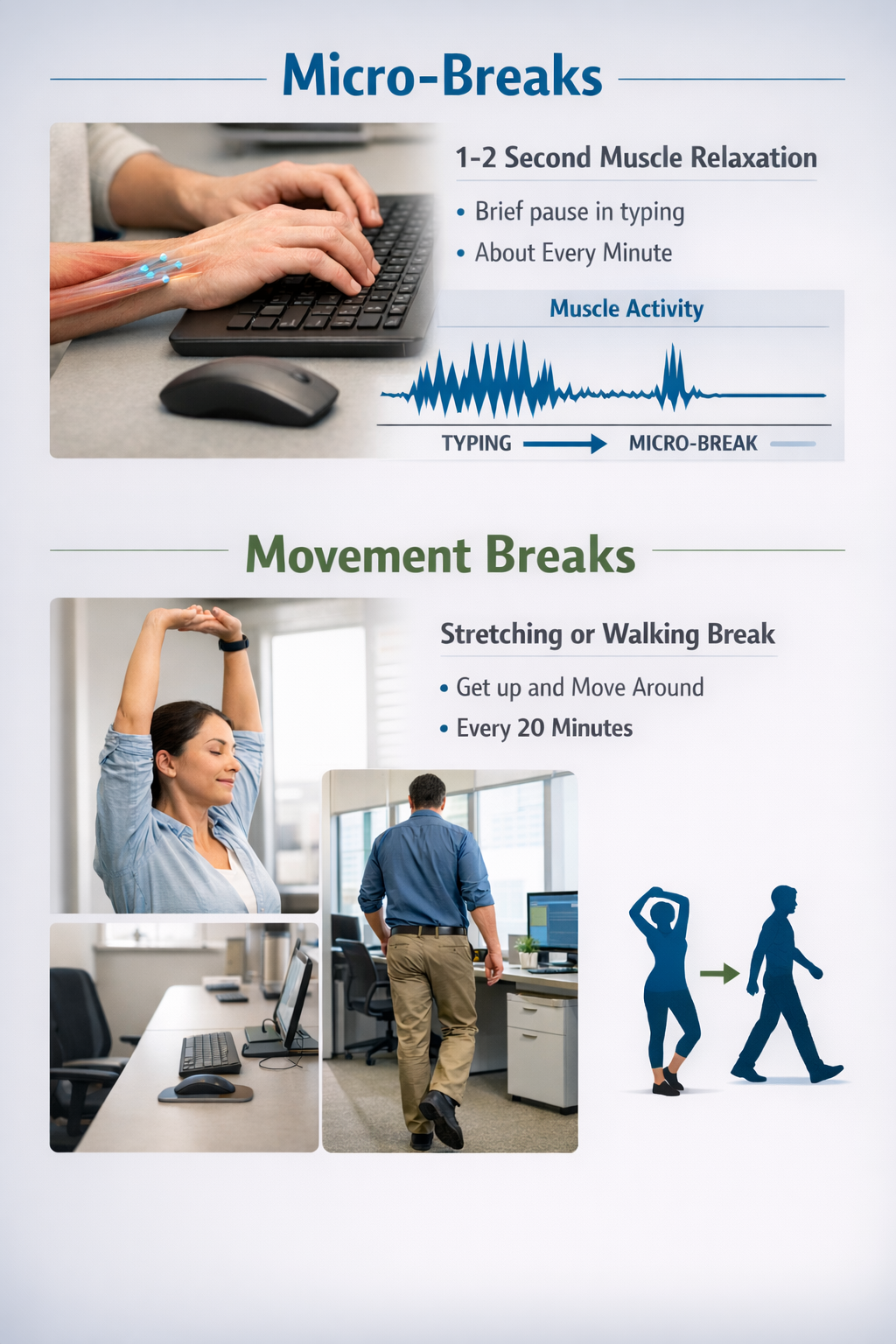

Healthy Computing

Healthy computing represents a systems approach to treating computer-related disorders. The eight components include: work style (adopting healthy work habits including micro-breaks, large movement breaks, and pacing workflow), ergonomics (adjusting the workspace and hardware to facilitate healthy posture and movement), somatic awareness (developing awareness of muscle tension and learning how to let go physically and emotionally), and stress management (learning skills to effectively cope with stressors).

Additional components include: regeneration (learning skills like meditation to recover from stress), vision care (preventing eye strain through appropriate prescription glasses, ergonomic monitor position, and glare reduction), fitness (regular stretching, muscle strengthening, and movement practice), and positive workstyle (social support that reduces arousal and increases performance).

A micro-break is a 1 to 2-second interruption of muscle activation (like the release of forearm muscle activity when a typist reaches the end of a paragraph) about every minute. A large movement break may involve stretching in place or leaving the computer and moving around. This exercise should be performed every 20 minutes.

When individuals frequently alternate between muscle contraction and relaxation, this increases blood and lymph circulation and helps prevent repetitive motion injury (RMI) (Peper & Gibney, 2005).

Demographics

Repetitive strain injuries remain a significant occupational health concern. Carpal tunnel syndrome, the most common work-related nerve compression disorder, has an estimated prevalence of 2.7-5.8% in the adult population (Rotaru-Zavaleanu et al., 2024). Risk factors include repetitive wrist movements, forceful grip, and use of handheld vibratory tools.

The 12-month prevalence of low back pain lasting seven or more days among manual material handling workers reaches 25%, with 14% seeking medical care and 10% losing work time (Kapellusch et al., 2019).

Peper and Gibney (1999) reported that 97.8% of surveyed individuals experienced some discomfort during an average of 2.7 hours daily computer use, and more than 50% of employees who use a computer more than 15 hours per week report musculoskeletal pain during their first year of employment (Gerr et al., 2002).

Biofeedback Protocols

SEMG biofeedback plays a critical role in healthy computing by improving client awareness of muscle tension and physiological reactivity, adjusting the workspace, posture, and movement to minimize muscle tension, and teaching them to release unnecessary muscle tension and dampen excessive reactivity rapidly.

Stress management is crucial since the repetition of the fight-or-flight response many times a day can unconsciously increase muscle bracing, particularly in shoulder and neck muscles. Linton and Kamwendo (1989) observed that an "approximately 3-fold increased risk for neck and shoulder pain was found for those experiencing a 'poor' as compared with those experiencing a 'good' psychological work environment."

Temperature biofeedback is indicated if the patient complains of cold hands. Surface EMG biofeedback can be combined with ergonomic training to reduce repetitive strain injury. Treatment should also incorporate the eight components of healthy computing (Peper & Gibney, 2002).

Clinical Efficacy

Based on multiple RCTs with no-treatment control, Zachary Meehan and Fred Shaffer (2023) rated biofeedback for worksite-related pain as level 3 probably efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

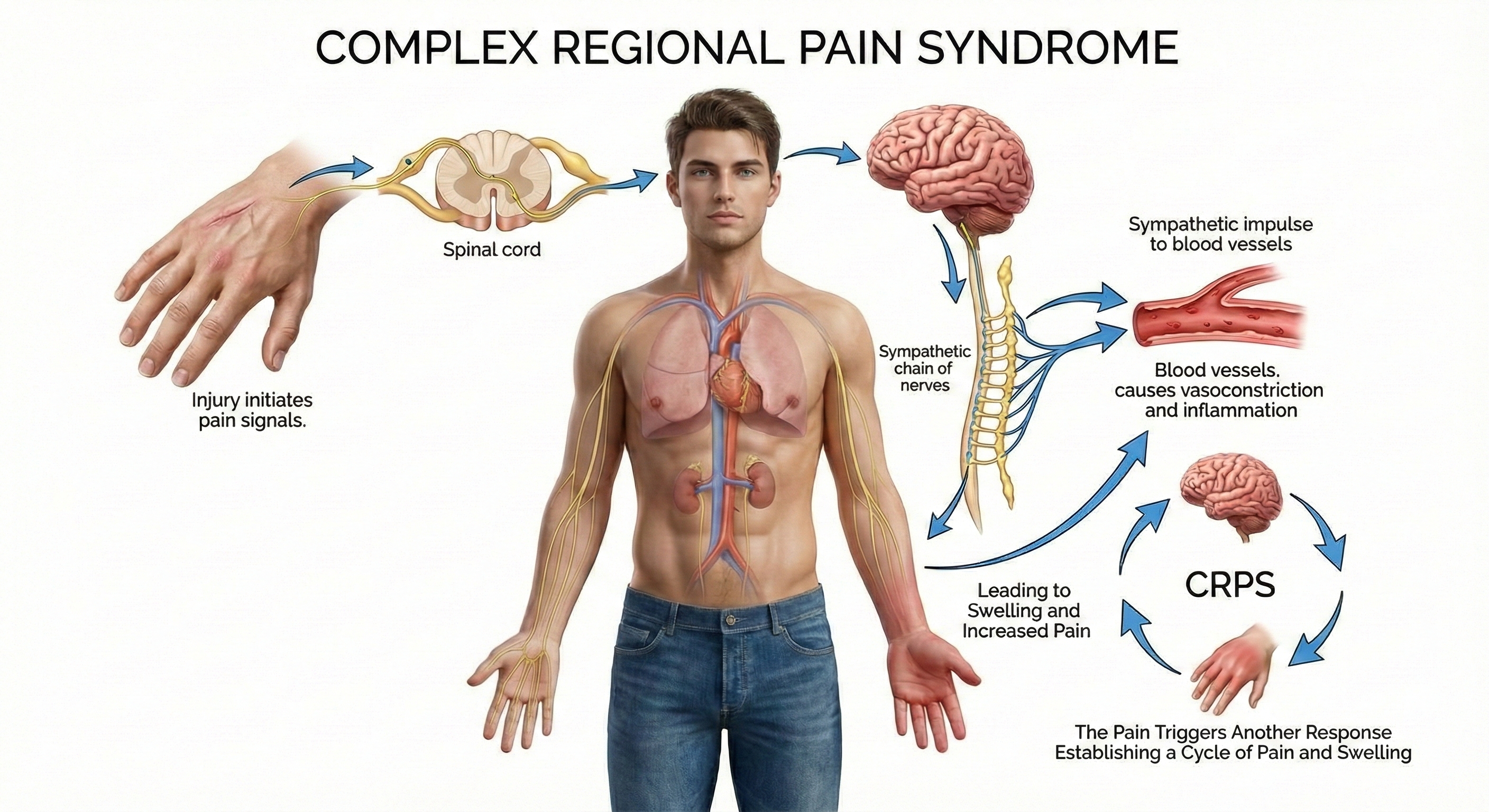

Complex Regional Pain Syndromes: A Challenging Condition

Complex Regional Pain Syndromes (CRPS) is the current term for Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome (RSDS). The main symptom of CRPS is severe, often burning pain.

CRPS is divided into Types I and II based on the initiating event. CRPS Type I, which is more common, is caused by a crushing injury, soft tissue injury, or immobilization. CRPS Type II is precipitated by nerve injury (Wheeler, 2014).

The disorder may progress to dystrophy (weakness or wasting) of the area. CRPS can be divided into three progressive stages, which every patient may not experience. These three stages include: (1) burning pain, most often in the hand and foot, (2) spreading of pain to the center of the body, often producing muscle spasms, and (3) wasting and contraction of muscles and other tissues causing impaired joint movement.

There is no agreement on the cause of CRPS. CRPS is now recognized as a systemic disease that stems from a complex interplay of inflammatory, immunologic, neurogenic, genetic, and psychological factors (Devarajan, Mena, & Cheng, 2024). Current hypotheses include injury to central or peripheral neural tissues, tonic activity in myelinated mechanoreceptor afferents, and peripheral nervous system pathology.

Neuroinflammation, characterized by activation of microglia and astrocytes in the CNS and macrophages in the PNS, plays a crucial role in the initiation and maintenance of CRPS pain (Wen, Pan, Cheng, Xu, & Xu, 2023). Patients with CRPS manifest elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, along with neurogenic inflammation involving the release of CGRP and substance P from nociceptive C-fibers (Devarajan et al., 2024). These neuropeptides can account for the vasodilation, edema, and sweating observed in CRPS.

Demographics

CRPS is classified as a rare disease by both the European Medicines Agency and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, with no more than 5 in 10,000 people in Europe and fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. affected (Ferraro et al., 2024). Population-based studies report incidence rates ranging from 5.5 to 26.2 per 100,000 person-years.

A 2025 meta-analysis found that among at-risk populations (those with trauma or surgery), the 12-month prevalence reaches 3.04% (D'Souza et al., 2025). The female-to-male ratio is approximately 3-4:1, with peak incidence in women aged 61-70 years. The upper limbs are affected more commonly than the lower limbs, and fracture is the most common precipitating event, accounting for approximately 44-46% of cases. Hand and wrist involvement accounts for about 67% of cases, followed by foot and ankle at 23% (Neuremberger et al., 2023).

Biofeedback Treatment Protocols

Biofeedback can reduce the musculoskeletal and ischemic (decreased supply of oxygenated blood) causes of CRPS. A combination of SEMG and temperature biofeedback can reduce subjective pain ratings for years.

Blanchard (1979) reported successful treatment of a patient with chronic pain resulting from CRPS in his hand and arm following months of conservative medical care failure. Eighteen sessions of temperature biofeedback taught the patient to increase hand temperature 1-1.5°C. Hand and arm pain significantly decreased during training and was absent at 1-year follow-up.

Barowsky, Zweig, and Moskowitz (1987) treated a 12-year-old male with CRPS pain in the knee area with temperature biofeedback. Biofeedback training started with hand-warming and then transferred vasodilation to the affected knee. The temperature increased in the affected knee, local vasospasms and cold intolerance ended in 10 sessions, and the patient resumed regular activity.

Grunert and colleagues (1990) trained 20 patients with CRPS, who failed to respond to traditional medical treatment, with thermal biofeedback, relaxation training, and supportive psychotherapy. Patients significantly increased initial and post-relaxation hand temperatures. They reduced subjective pain ratings, maintained at 1-year follow-up. Fourteen of 20 patients returned to work within 1 year.

Clinical Efficacy

Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.) did not evaluate biofeedback for CRPS.

Comprehension Questions: Pain Disorders

- How does the flexion-relaxation phenomenon differ between individuals with and without chronic low back pain?

- What distinguishes tender points from trigger points, and why is this distinction clinically important?

- Why is bilateral training important when treating TMD with SEMG biofeedback?

- What role does lack of awareness play in the development of repetitive strain injury?

- How can temperature biofeedback help patients with CRPS even when the affected area is not the hand?

- According to the biopsychosocial model, why should treatment goals focus on improving function rather than achieving zero pain, and how does this perspective help explain why structural imaging often fails to identify the source of chronic low back pain?

Cutting-Edge Topics in Pain Research

CGRP-Targeted Therapies Transform Migraine Prevention

The development of CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide) inhibitors represents a major advance in mechanism-specific migraine treatment. Between 2018 and 2025, four monoclonal antibodies (erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab, eptinezumab) and three gepants (ubrogepant, rimegepant, atogepant) received approval, with approximately half of patients achieving 50% or greater reduction in monthly migraine days (Ashina et al., 2025). Next-generation targets include dual CGRP-PACAP antibodies and orexin-modulating agents. Understanding how these pharmacological advances complement biofeedback training opens new possibilities for integrated treatment approaches.

Nociplastic Pain: A Third Pain Mechanism

The International Association for the Study of Pain has formally recognized nociplastic pain as a third category distinct from nociceptive and neuropathic pain. This term describes altered nociception despite no clear evidence of tissue damage or nervous system lesion, applicable to conditions including fibromyalgia, chronic TTH, and some TMD cases (Nijs et al., 2023). The mechanisms involve both "top-down" dysregulation of descending inhibitory pathways and "bottom-up" facilitation of ascending pain signals. Recognizing nociplastic components helps explain why traditional analgesics are often ineffective and supports biofeedback interventions that address central nervous system regulation.

Neuroimaging Reveals Migraine Generator Activity

Advanced neuroimaging studies have confirmed the hypothalamus as a critical generator of migraine attacks. Schulte and May (2016) used continuous scanning over 30 days to track the migraine cycle through three spontaneous attacks. They found increased hypothalamic activity during the prodromal phase, well before headache onset. This research supports the development of preventive interventions targeting the hypothalamic "window" before headaches become established.

Genetic Insights into Raynaud's Phenomenon

A 2024 genome-wide association study across multiple biobanks identified eight genetic loci associated with Raynaud's syndrome, including significant associations with ADRA2A (alpha-2A-adrenergic receptor), NOS3 (endothelial nitric oxide synthase), and HLA genes (Lane et al., 2024). The ADRA2A finding provides strong genetic support for the local fault hypothesis and adrenergic signaling as a major risk factor. These discoveries may guide development of targeted therapies and help identify patients likely to respond to specific interventions.

Central Sensitization as a Unifying Mechanism

Research increasingly recognizes central sensitization as a common mechanism across multiple chronic pain conditions, including TTH, fibromyalgia, TMD, and chronic low back pain. Bhoi, Jha, and Chowdhury (2021) describe how repeated nociceptive input can produce lasting changes in CNS pain processing that persist even after the original tissue damage has healed. This understanding supports the use of biofeedback interventions that address both peripheral muscle tension and central nervous system regulation.

HRV Biofeedback for Co-occurring Conditions

A 2025 systematic review by Al-Balushi, Mulay, and Manzar confirmed that HRV biofeedback is a feasible and safe intervention for chronic disease management, with positive effects on pain, depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances across various patient profiles (Al-Balushi et al., 2021). A 2026 RCT by Chadwick and colleagues demonstrated that six weeks of HRV biofeedback produced a 24% reduction in PTSD symptoms and 25% improvement in pain interference for patients with co-occurring chronic pain and PTSD, with large effect sizes. These findings underscore biofeedback's potential for treating complex, co-occurring pain conditions.

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia and Medication Dependence

Long-term opioid use for chronic pain can paradoxically increase pain sensitivity through opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH). A 2024 meta-analysis of 39 studies involving 1,385 patients found that individuals receiving opioid agonist treatment demonstrated 22% lower pain threshold and 52% lower pain tolerance compared to controls (van der Schrier et al., 2024).

OIH involves NMDA receptor activation and alterations in descending pain modulation pathways. Withdrawal from chronic opioid therapy often produces temporary increases in pain, insomnia, anxiety, and depression, though many patients ultimately report improved function, sleep, and mood after successful tapering (HHS, 2019). Biofeedback may serve as a valuable adjunct during opioid tapering by providing patients with alternative pain management strategies and improving autonomic regulation.

CBT-I for Comorbid Insomnia and Chronic Pain

A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 RCTs (762 participants) found that cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) produces large improvements in sleep quality and small but significant improvements in pain and depressive symptoms in patients with chronic non-cancer pain (Selvanathan et al., 2021). Effects on sleep remained significant at 12-month follow-up.

A 2022 network meta-analysis comparing CBT-I, CBT for pain, and hybrid interventions found that CBT-I was the most effective treatment for individuals with comorbid insomnia and chronic pain, outperforming CBT for pain alone on sleep, pain, disability, and depression outcomes (Enomoto et al., 2022). These findings support routine screening for insomnia in chronic pain patients and the integration of sleep-focused behavioral interventions into comprehensive pain management.

Test Yourself

Click on the ClassMarker logo to take 10-question tests over this unit without an exam password.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Visit the BioSource Software Website

BioSource Software offers Human Physiology, which satisfies BCIA's Human Anatomy and Physiology requirement, and Biofeedback100, which provides extensive multiple-choice testing over BCIA's Biofeedback Blueprint.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, how would you design a comprehensive treatment protocol for a patient presenting with both tension-type headache and chronic low back pain? Consider the assessment procedures, biofeedback modalities, and complementary interventions you would include.

Glossary

active SEMG training: Neblett's approach that combines neuromuscular rehabilitation with general relaxation, involving a collaborative process in which the clinician and client share SEMG biofeedback to identify patterns of muscle bracing associated with pain.

allodynia: the perception of benign stimuli as painful.

alpha-2C-adrenergic receptors: a subtype of alpha-2 adrenergic receptors that contribute to cold-induced vasoconstriction and are particularly important in Raynaud's phenomenon.

asymmetry: an imbalance between the SEMG measurements of homologous left and right muscle groups. A 20% difference threshold has been used clinically to distinguish pain patients from healthy controls during dynamic movement assessment, though the relationship between asymmetry and pain is correlational rather than definitively causal (Donaldson, 1990).

aura (prodrome): neurological symptoms that precede a breakthrough headache, hours to days before headache onset, observed in migraine with aura (classic migraine); caused by cortical spreading depression.

basilar artery migraine: headache with prodromal symptoms lasting from 2-45 minutes with symptoms of total blindness, altered consciousness, vertigo, and ataxia involving the brainstem.

bidirectional relationship: a mutual influence between two conditions where each can cause or exacerbate the other; in pain and sleep, poor sleep increases pain sensitivity while pain disrupts sleep, creating a self-perpetuating cycle.

biopsychosocial model: a comprehensive framework for understanding and treating chronic pain that integrates biological factors (genetics, tissue injury, central sensitization, endogenous pain modulation), psychological factors (mood, cognitions, coping styles, catastrophizing), and social factors (family, workplace, culture, healthcare access). Pioneered by researchers including Dennis Turk, this model recognizes that pain emerges from a dynamic interplay of these factors rather than tissue damage alone, and that treatment goals should focus on improving function and quality of life rather than eliminating pain entirely (Gatchel et al., 2007; Nicholas, 2022).

Budapest criteria: the current diagnostic criteria for CRPS requiring disproportionate pain, patient-reported symptoms in at least three of four categories (sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor/edema, motor/trophic), and at least one clinical sign in two of the four categories.

calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP): a neuropeptide that, along with substance P, stimulates pain receptors and increases blood vessel dilation in migraine headaches.

CGRP monoclonal antibodies: a class of migraine-preventive medications (erenumab, fremanezumab, galcanezumab, eptinezumab) that target CGRP or its receptor; approximately half of treated patients achieve a 50% or greater reduction in monthly migraine days.