Psychophysiology

What You Will Learn in This Chapter

Have you ever noticed your heart pounding during a suspenseful movie scene, even though you are perfectly safe in your seat? This unit explores the fascinating two-way street between your mind and body. You will discover how Green and Green's revolutionary psychophysiological principle explains why thoughts can make your palms sweat and why relaxing your muscles can calm your racing mind.

Along the way, you will explore the three branches of the autonomic nervous system, unpack Porges' intriguing polyvagal theory (which reveals that we have more options than just "fight or flight"), and learn why conducting a thorough psychophysiological stress profile is essential before designing a treatment plan. By the end of this unit, you will understand concepts like homeostasis, habituation, the law of initial values, and how placebo effects work at the neurological level.

You will also discover cutting-edge research frontiers that are reshaping how scientists and clinicians think about the mind-body connection. These include how your nervous system can actually help "brake" inflammation, why some people with Long COVID experience symptoms that feel like their body's automatic settings are off, how slow aging of the immune system connects to autonomic flexibility, and what happens when your brain misreads signals from inside your body.

This unit covers the Psychophysiological Principle, the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS), Sympathetic Division, Parasympathetic Division, Porges' Polyvagal Theory, Enteric Division, The Relationship Between the Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Branches, Homeostasis, Autonomic Balance, Psychophysiological Measurements, Orienting and Defensive Responses, Activation and Habituation, Situational Specificity, Law of Initial Values (LIV), Generalization of Biofeedback Training, and the Placebo Effect. This unit also explores cutting-edge research frontiers including the Inflammatory Reflex and Neuroimmune Regulation, Long COVID and Autonomic Dysfunction, Inflammaging and Healthy Aging, and Interoception and Body Signal Awareness.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage: This unit addresses Structure and function of the autonomic nervous system (V-A1-2) and Psychophysiological Concepts (V-B).

This powerful idea forms the foundation of Green and Green's psychophysiological principle.

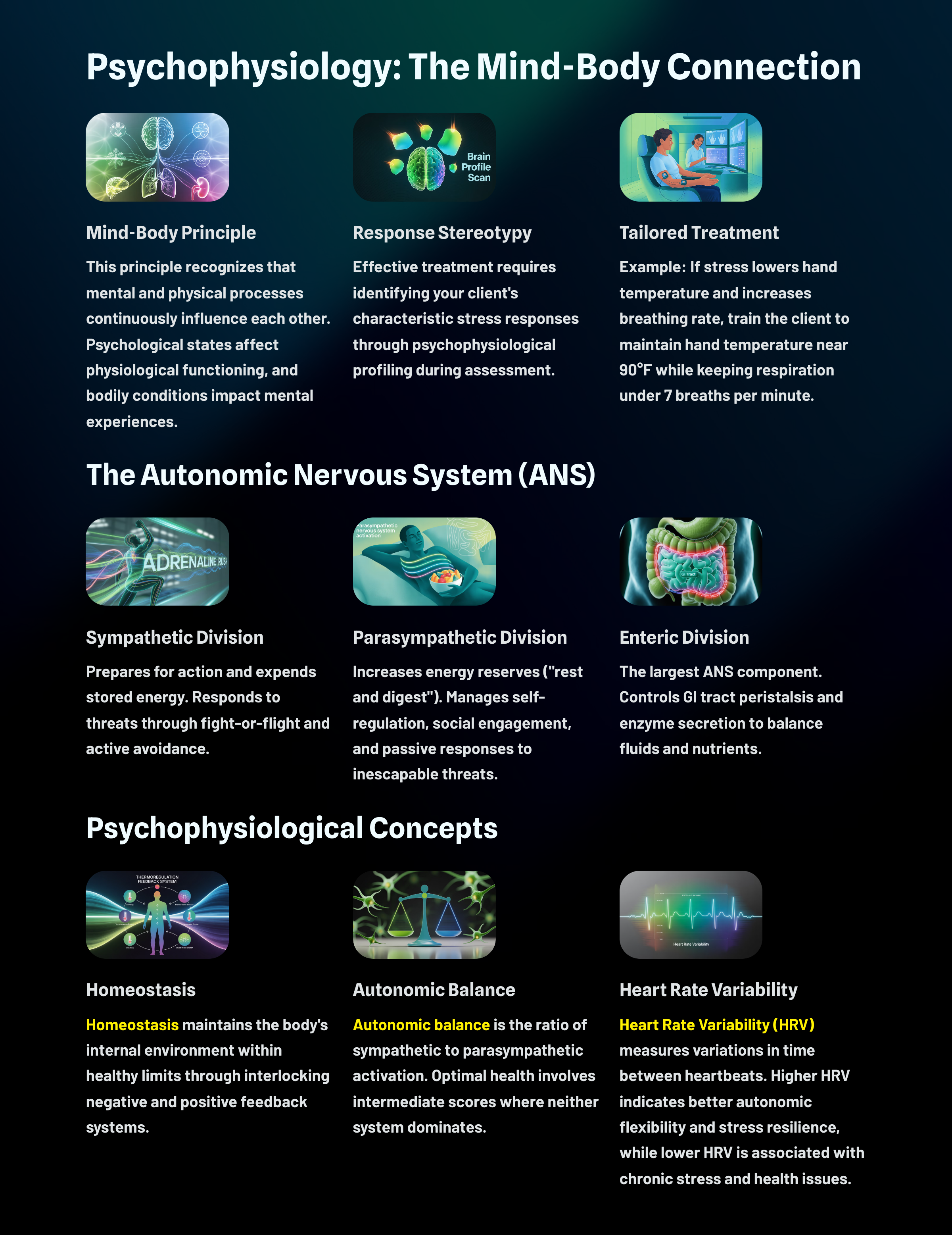

Listen to a mini-lecture on PsychophysiologyPsychophysiology studies the interrelationship between psychological and physiological processes. As Andreassi (2007) explained, "Psychophysiology is the study of relations between psychological manipulations and resulting physiological responses, measured in the living organisms, to promote understanding of the relation between mental and bodily processes" (p. 2). The interrelationship between psychological and physiological processes is dynamic and bidirectional.

As a biofeedback practitioner, you study the basic principles of psychophysiology to understand disease processes and health and how clinical interventions achieve their results.

The idiographic approach, which emphasizes individual differences, is critical to biofeedback practice. Think of it this way: just as no two fingerprints are identical, each client's response to stressors is unique, specific, and often complex.

Clinical Application: Discovering Your Client's Unique Pattern

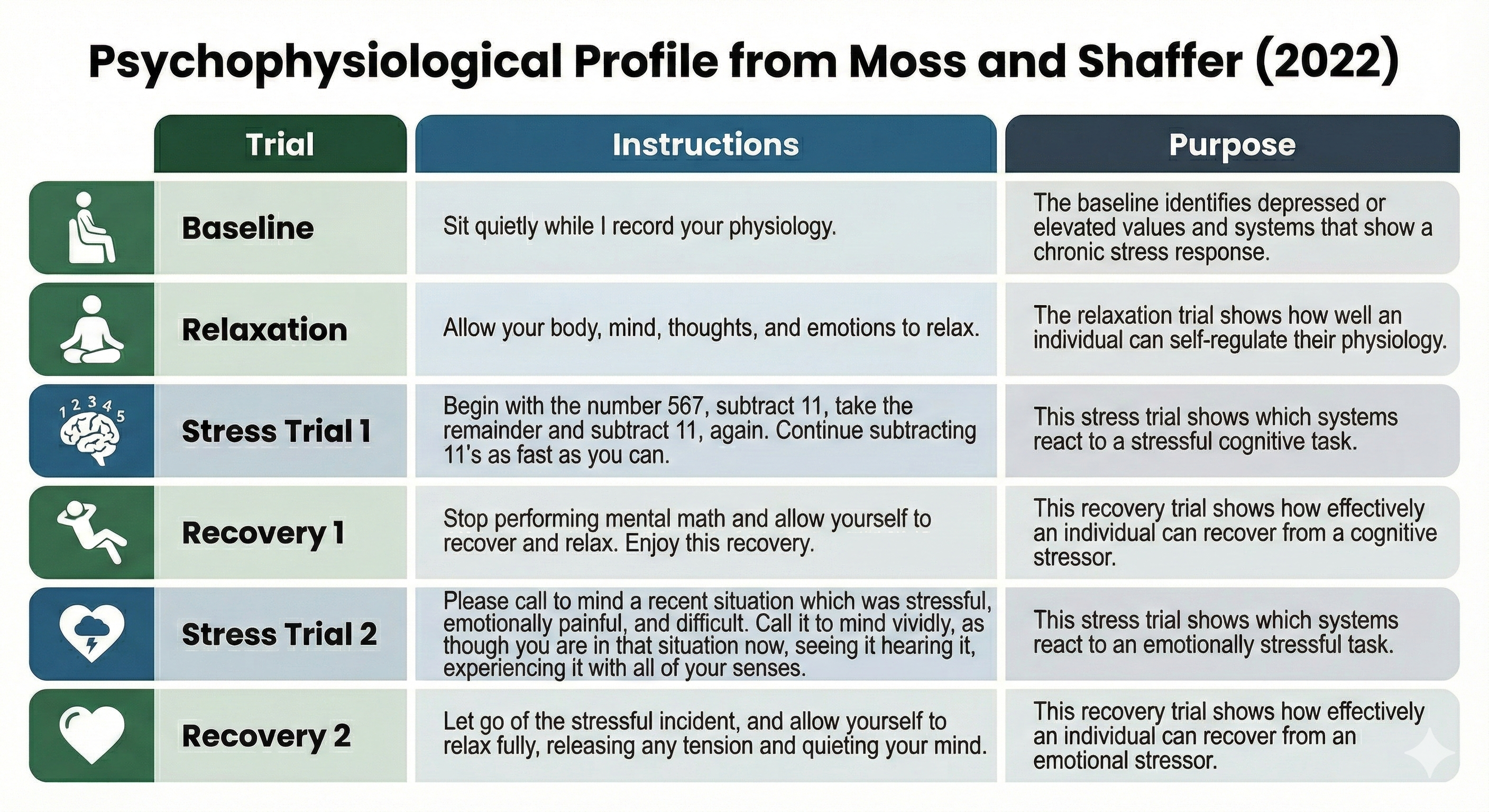

To effectively treat your client, you need to discover their characteristic responses to stressors during a psychophysiological profile administered during the assessment stage of treatment. Consider a client named Jack who comes to you for stress management. During his assessment, you notice that his hand temperature falls and his respiration rate increases during math and visual imagery stressors. Based on this unique pattern, you might consider training Jack to maintain hand temperature around 90°F (32.2°C) while breathing under 7 breaths per minute. This tailored approach may prove far more effective than using a standard treatment protocol that disregards his response stereotypy, his characteristic pattern of physiological responses to stress.

This unit will challenge the simplistic belief that the sympathetic division fight-or-flight response is our only means of responding to stressors. The parasympathetic branch expands our response options through immobilization, feigning death, passive avoidance, and shutdown, or through social engagement supported by the release of the hormone oxytocin.

The Revolutionary Psychophysiological Principle

Green, Green, and Walters' (1970) psychophysiological principle was revolutionary because it proposed a bidirectional relationship between physiological and psychological functioning:

Every change in the physiological state is accompanied by an appropriate change in the mental emotional state, conscious or unconscious, and conversely, every change in the mental emotional state, conscious or unconscious, is accompanied by an appropriate change in the physiological state.

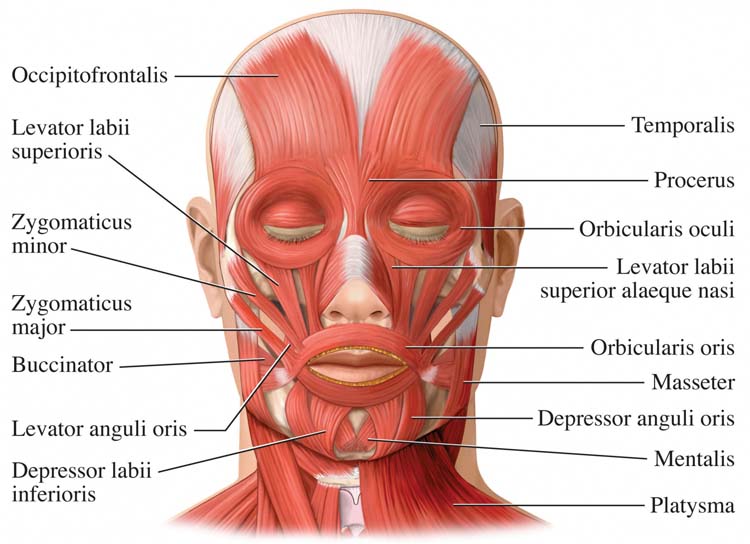

Here is a compelling example of the psychophysiological principle in action: facial muscle contraction can influence emotion, and emotion can influence facial muscle contraction. Researchers have discovered that Botox injections, which paralyze facial muscles to treat wrinkles, actually reduce the intensity of a person's emotional experiences. When you cannot physically frown, the brain receives fewer signals associated with negative emotions.

Key Takeaways: The Psychophysiological Principle

The psychophysiological principle tells us that mind and body form a continuous loop. When your client learns to change their physiology through biofeedback, they are simultaneously changing their psychological state. Conversely, cognitive and emotional interventions produce measurable physiological changes. This bidirectional relationship is the foundation of biofeedback practice.

The Autonomic Nervous System: Your Body's Control Center

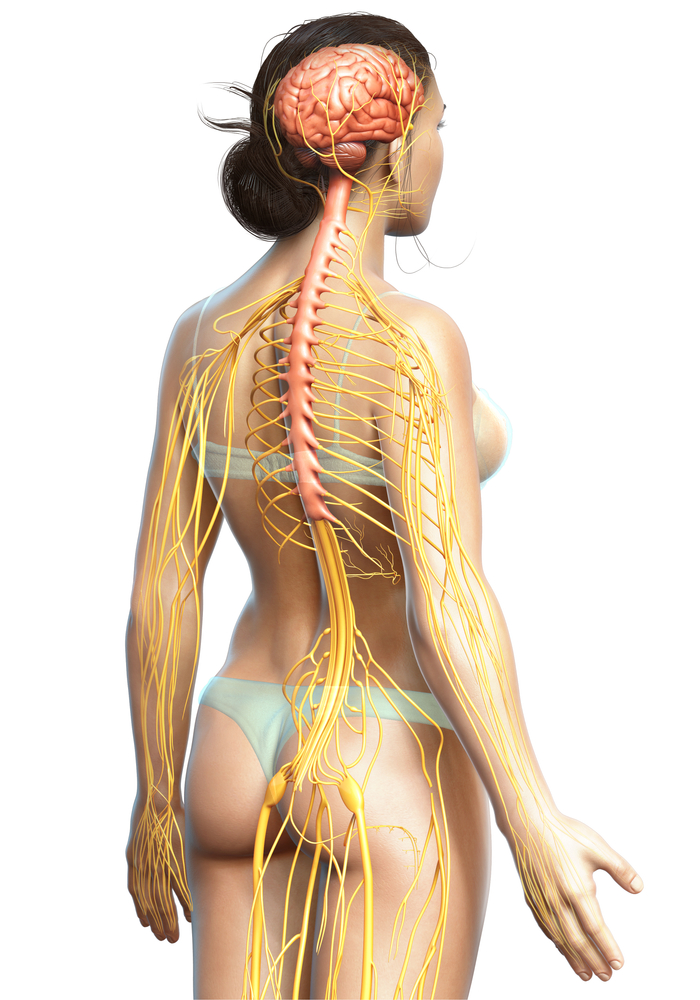

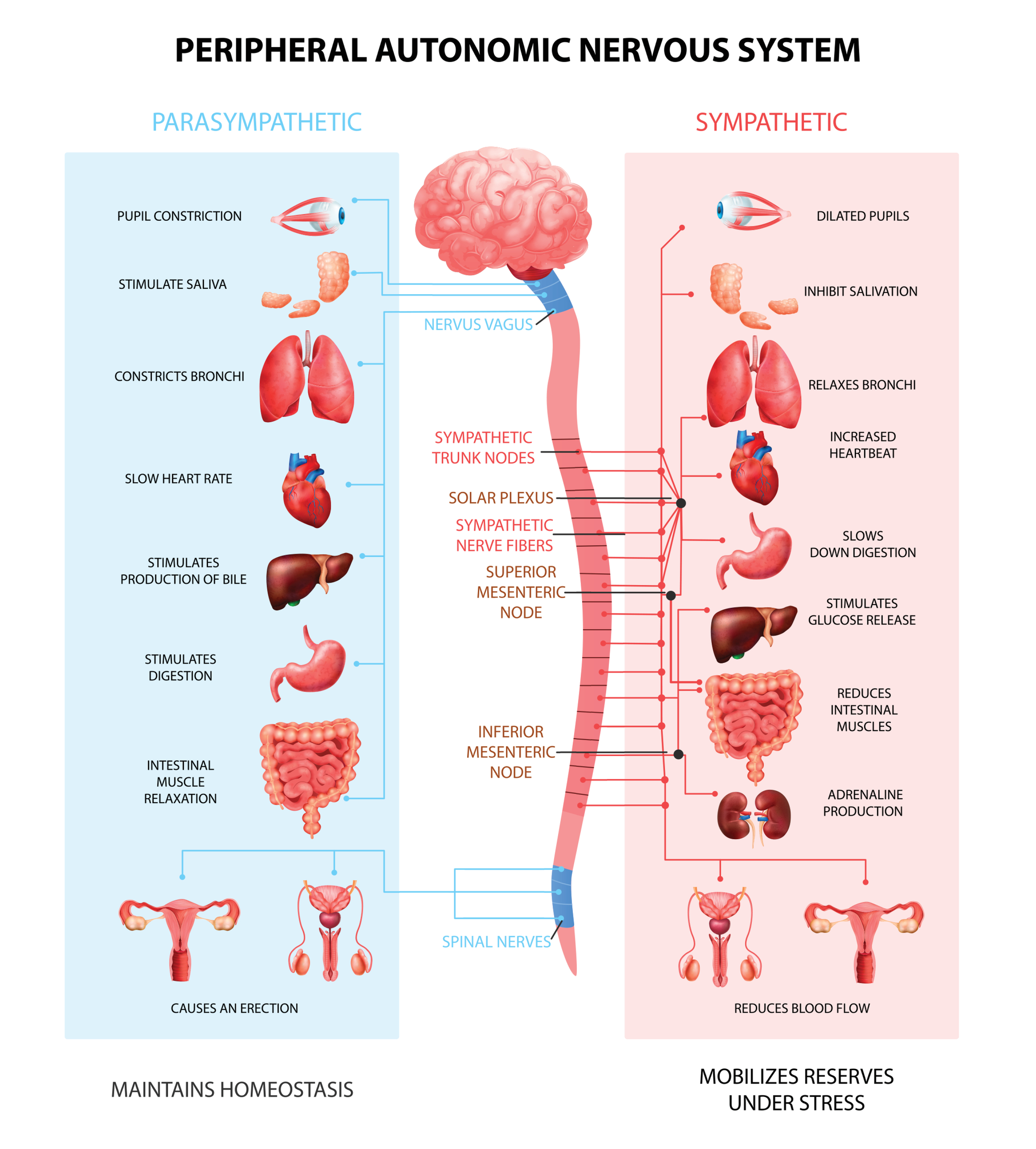

The central nervous system (CNS) includes the brain, spinal cord, and retina. The peripheral nervous system consists of the somatic nervous system and the three branches of the autonomic nervous system (Breedlove & Watson, 2023).

Listen to a mini-lecture on the Central and Peripheral Nervous Systems

The somatic nervous system controls the contraction of skeletal muscles and transmits somatosensory information to the CNS. The autonomic nervous system (ANS) regulates cardiac and smooth muscle and glands, transmits sensory information to the CNS, and innervates muscle spindles.

The ANS is divided into three main systems: sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric. Check out the YouTube video The Autonomic Nervous System.

The Sympathetic Division: Your Emergency Response System

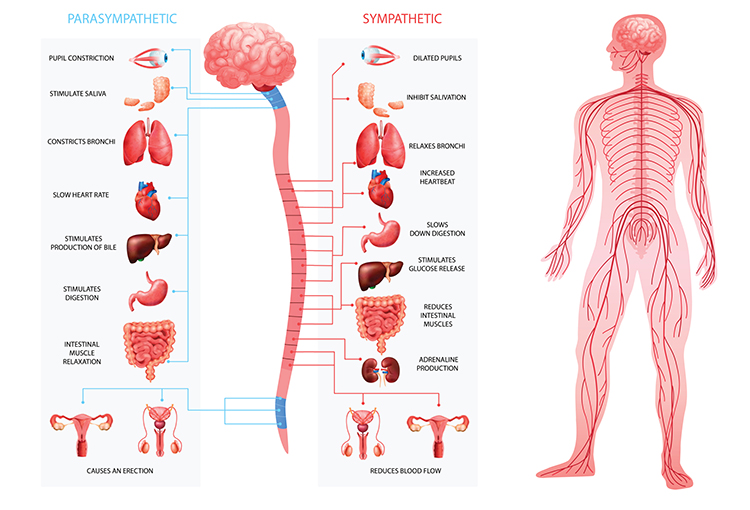

Think of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) as your body's alarm system. It readies you for action and regulates activities that expend stored energy. A simple way to remember this system is that sympathetic activity prepares the body for "fight or flight" (Gentile et al., 2024; Karemaker, 2017).

Listen to a mini-lecture on the Sympathetic Nervous System Function

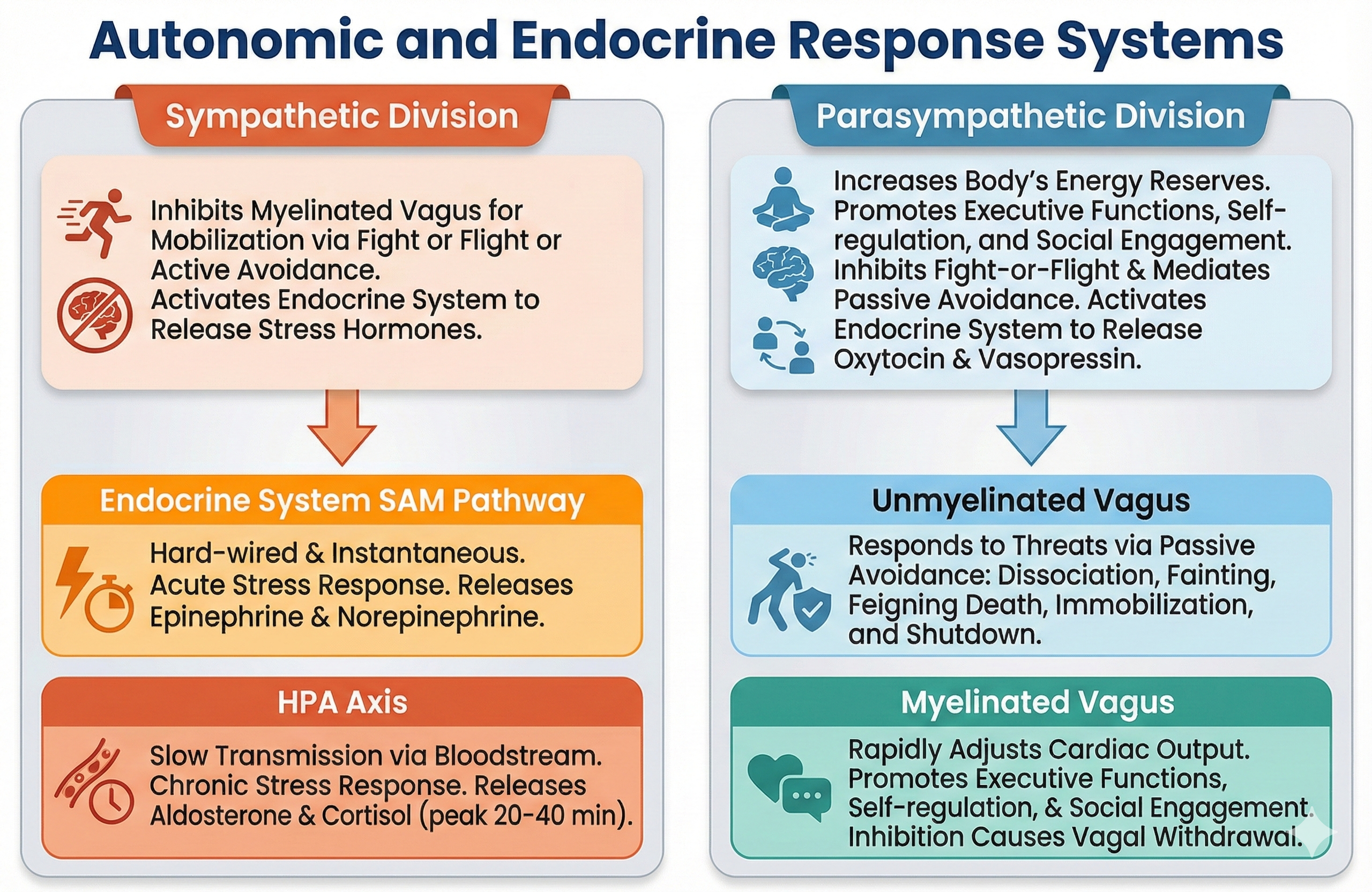

The SNS, in concert with the endocrine system, responds to threats to our safety through mobilization, fight-or-flight, and active avoidance. The SNS responds more slowly (greater than 5 seconds) and for a more extended period than the more rapid (less than 1 second) parasympathetic vagus system (Nunan et al., 2010). Porges (2011) theorized that the SNS inhibits the unmyelinated vagus (dorsal vagal complex) to mobilize us for action.

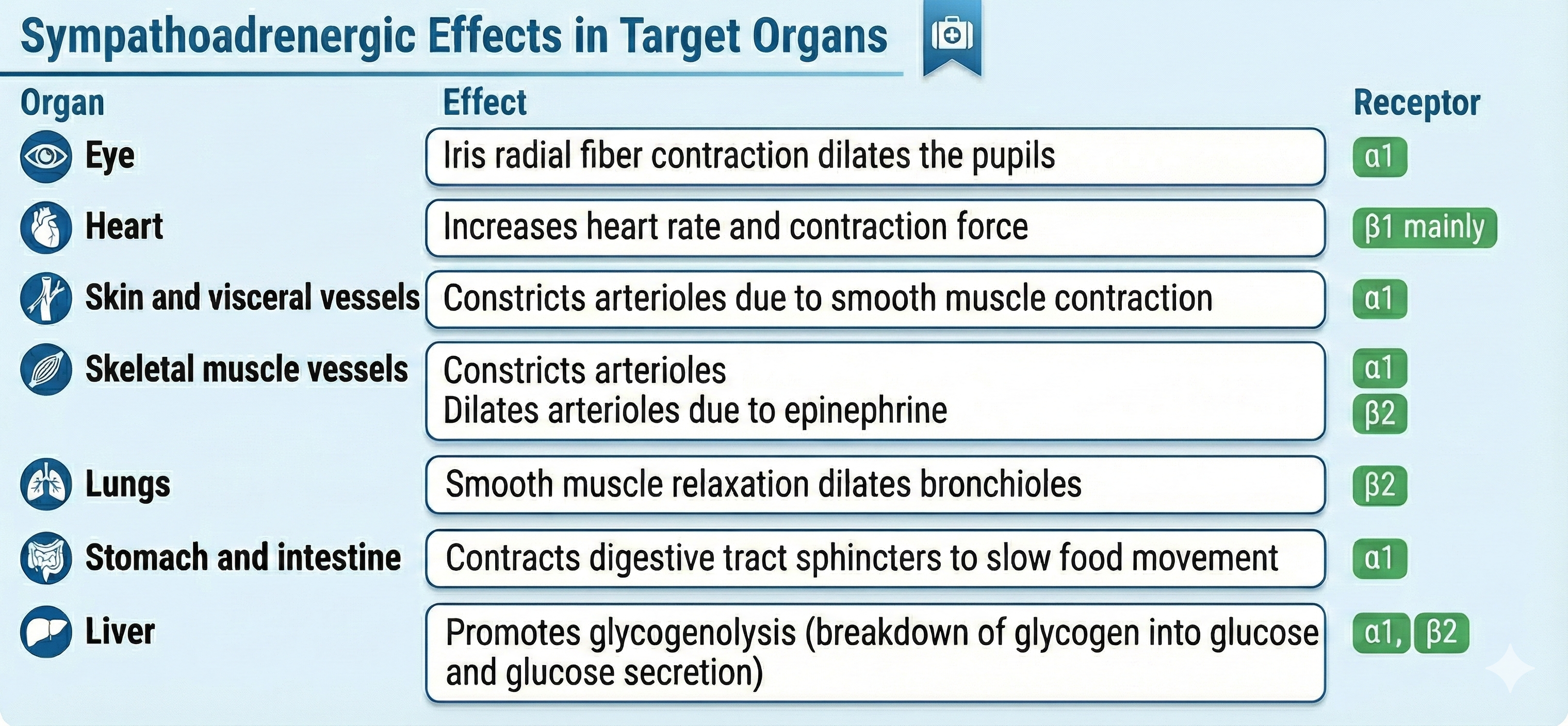

When activated, the SNS produces mass activation, meaning multiple organs respond simultaneously. This coordinated response includes increased heart rate and respiration, dilated pupils, reduced digestive activity, and increased blood flow to skeletal muscles. The SNS achieves this through the release of norepinephrine and epinephrine from the adrenal medulla, arrector pili muscles of the skin, cutaneous sweat glands, and most blood vessels.

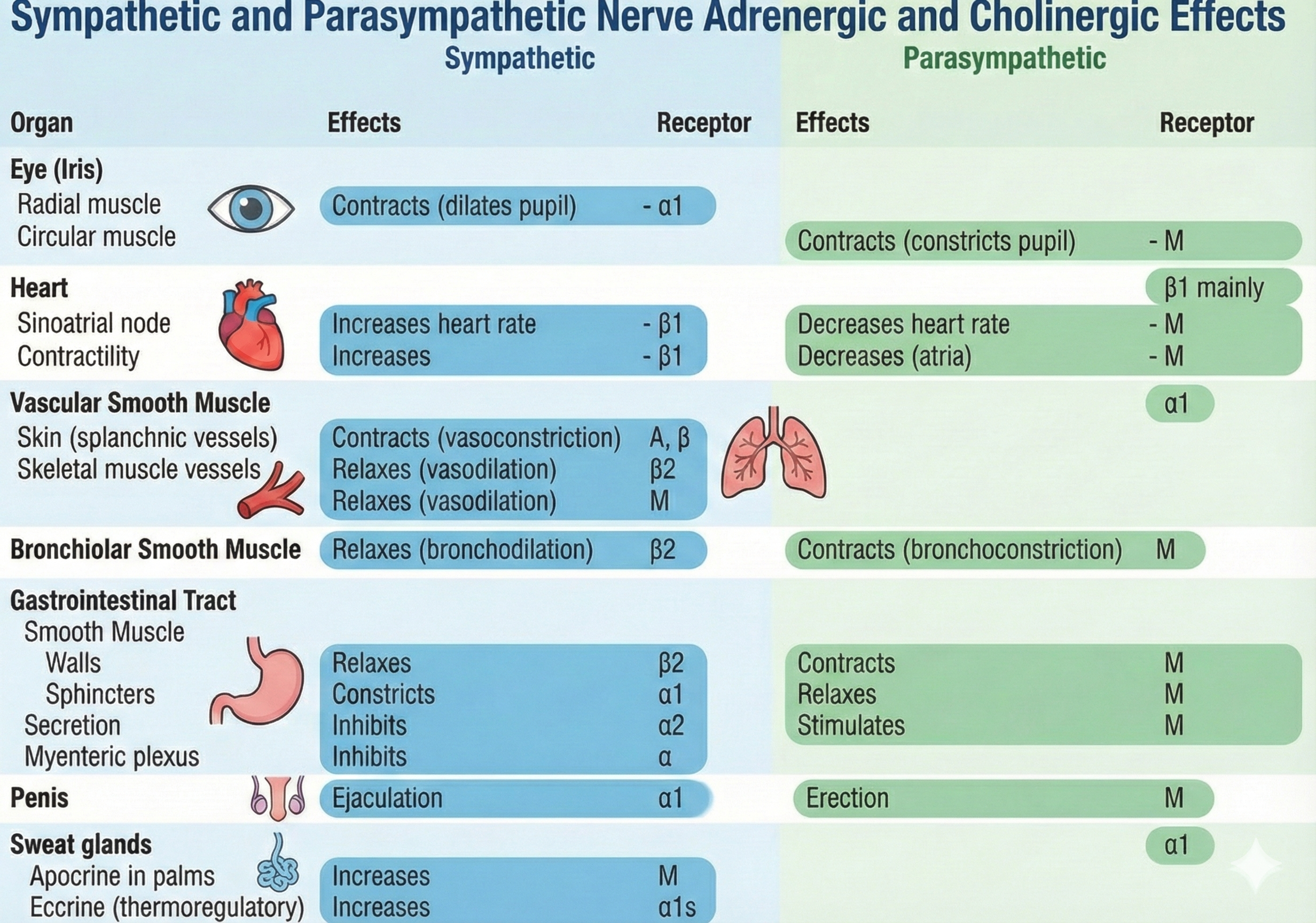

Adrenergic receptors produce changes through G-proteins. The following table is adapted from Fox and Rompolski (2022).

Organs With Sympathetic Innervation Only

The adrenal medulla, arrector pili muscles of the skin, cutaneous sweat glands, and most blood vessels receive sympathetic innervation exclusively (Fox & Rompolski, 2025).

Preganglionic and Postganglionic Neurotransmitters Are Different

SNS preganglionic and postganglionic axons release different neurotransmitters. SNS preganglionic axons secrete acetylcholine, while the postganglionic axons secrete norepinephrine. Sweat glands and skeletal muscle blood vessels are the exceptions to this rule. The postganglionic axons that innervate them release acetylcholine (Fox & Rompolski, 2025).

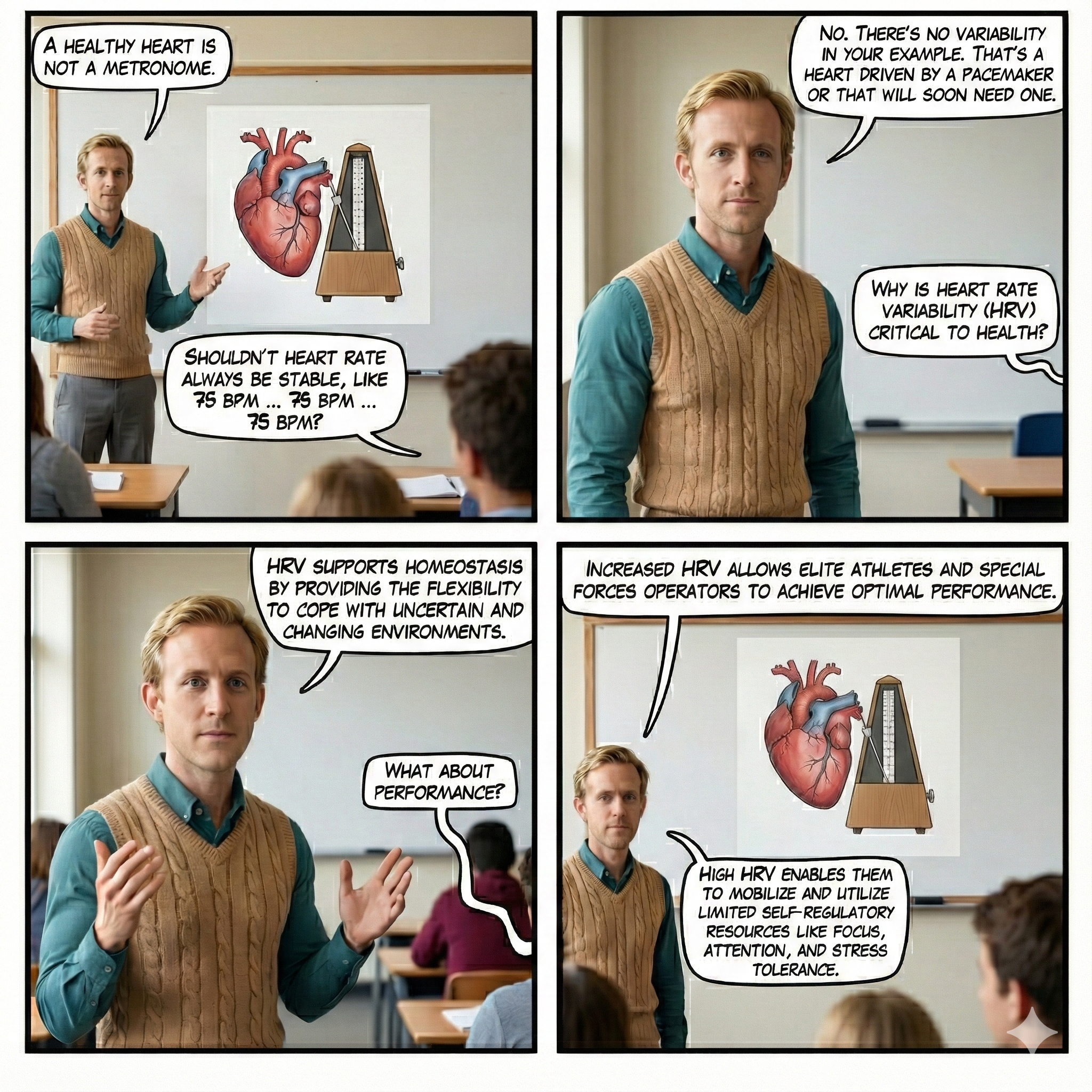

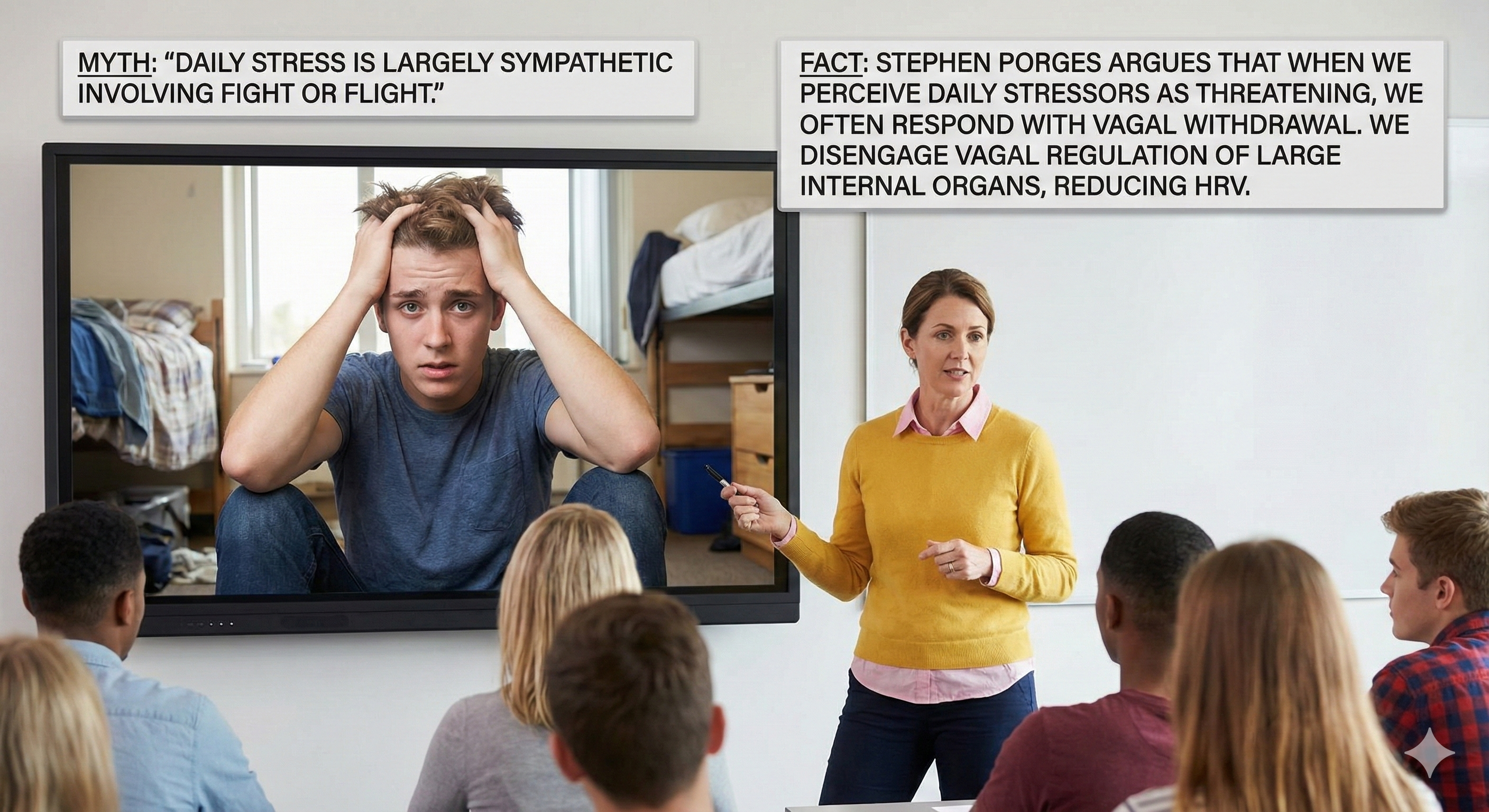

The Sympathetic Branch and Heart Rate Variability

Heart rate variability (HRV) is the natural beat-to-beat variation in the time between heartbeats, reflecting how flexibly the ANS is influencing the heart. A later section explores HRV in depth as a window into brain-heart communication. Here, we focus on a critical clinical point: the SNS does not appear to contribute significantly to the low-frequency (LF) component (0.04-0.15 Hz) of HRV under resting conditions, as was previously believed (Draghici & Taylor, 2016; Tiwari et al., 2020).

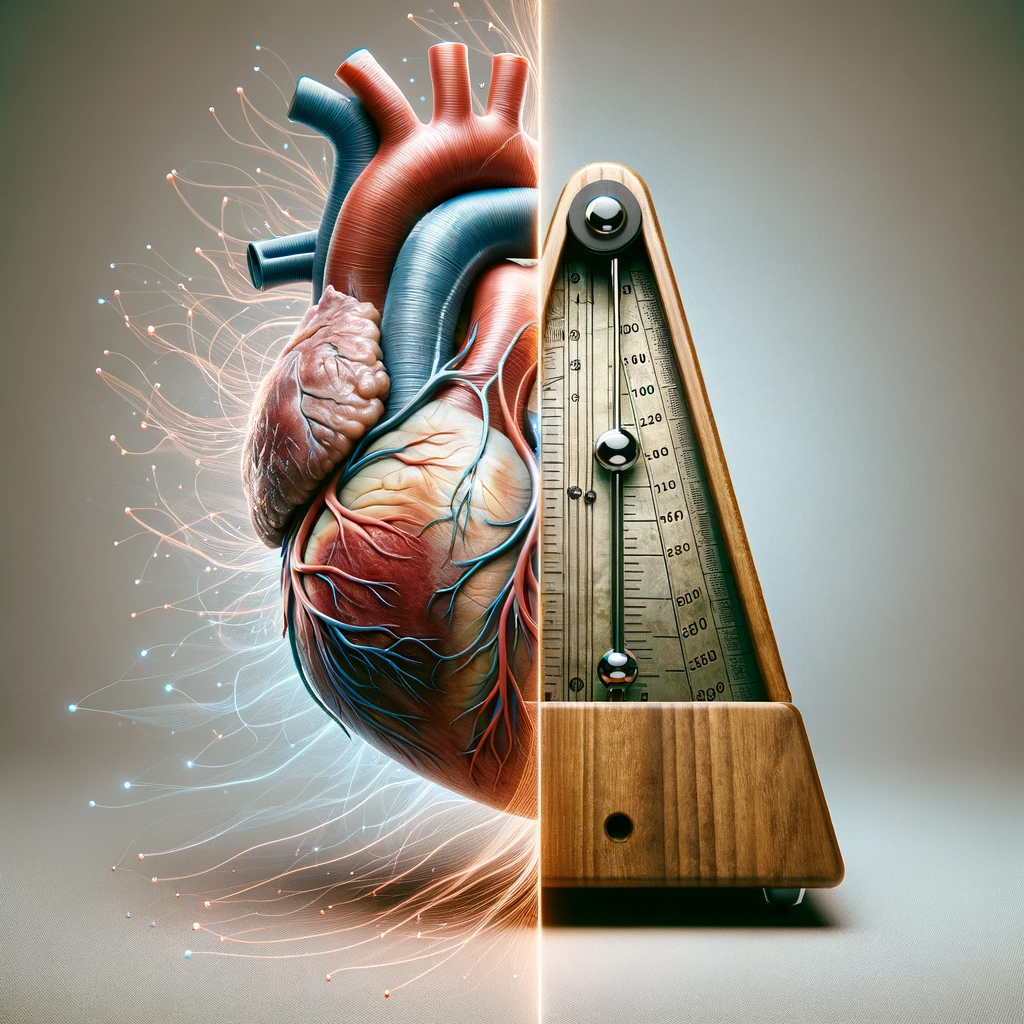

A healthy heart is not a metronome.

Most commonly used HRV measures, such as the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) and high-frequency (HF) power (0.15-0.40 Hz), are strongly driven by rapid vagus nerve effects on the heart and are therefore considered markers of cardiac vagal tone, or parasympathetic influence (Ernst, 2017; Thomas et al., 2019). Reviews and experimental work show that markers once thought to indicate sympathetic activity, such as LF power, actually reflect a mixture of influences and should not be treated as pure sympathetic measures (Ernst, 2017; Thomas et al., 2019). The broad consensus is that the main HRV indices used in research and clinical practice mostly reflect parasympathetic rather than sympathetic activity (Draghici & Taylor, 2016; Tiwari et al., 2020).

Stephen Porges has emphasized that most stressors do not require the sympathetic branch's intensive energy expenditure during fight-or-flight.

When we perceive daily stressors as challenging, this causes vagal withdrawal instead of sympathetic activation. In vagal withdrawal, we disengage parasympathetic control of our viscera (large internal organs) and reduce HRV.

We shift from a more calm, socially engaged state. We are now ready for mobilization, either fight or flight (mediated by the SNS) or immobilization.

Vagal withdrawal increases power in the very-low-frequency (VLF) band (0.04 Hz and below) and lowers it in the HF band.

Dr. Gevirtz provides an overview of the sympathetic branch © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. You can enlarge this video by clicking on the bracket icon at the bottom right of the screen. When finished, click on the ESC key.

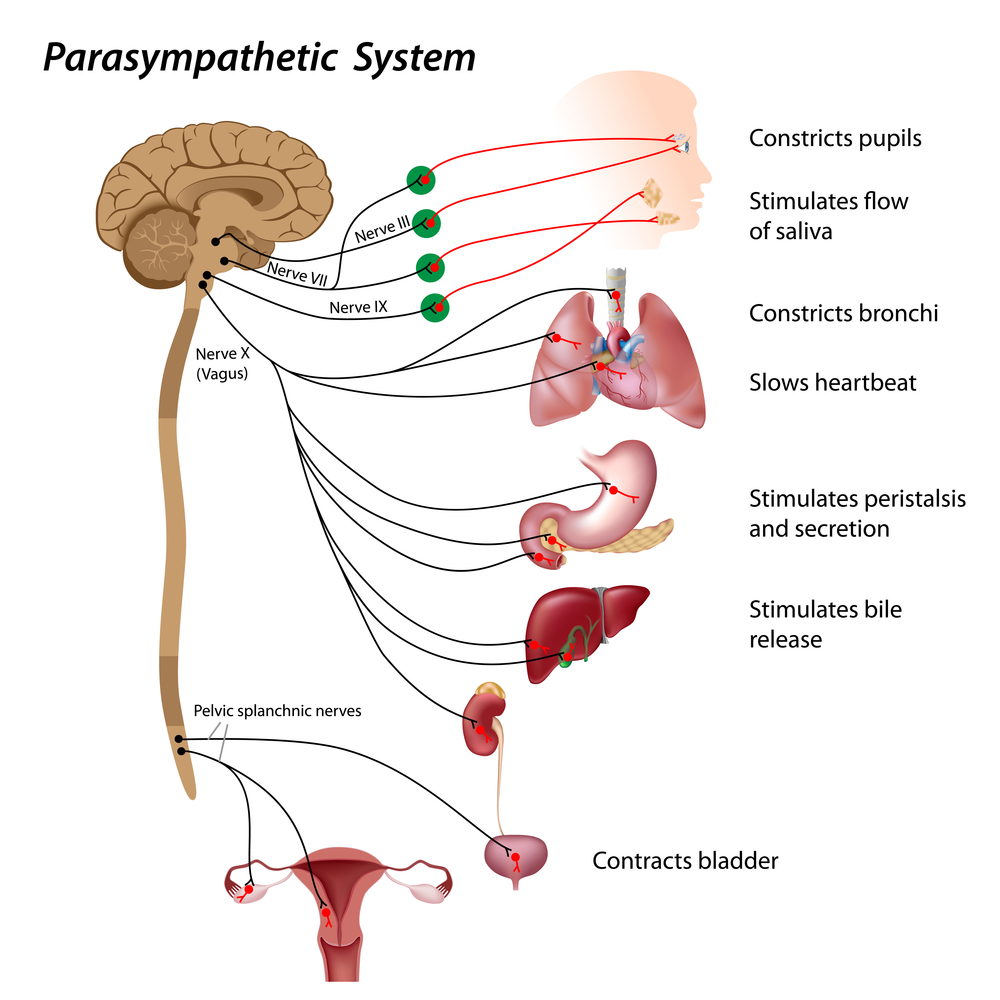

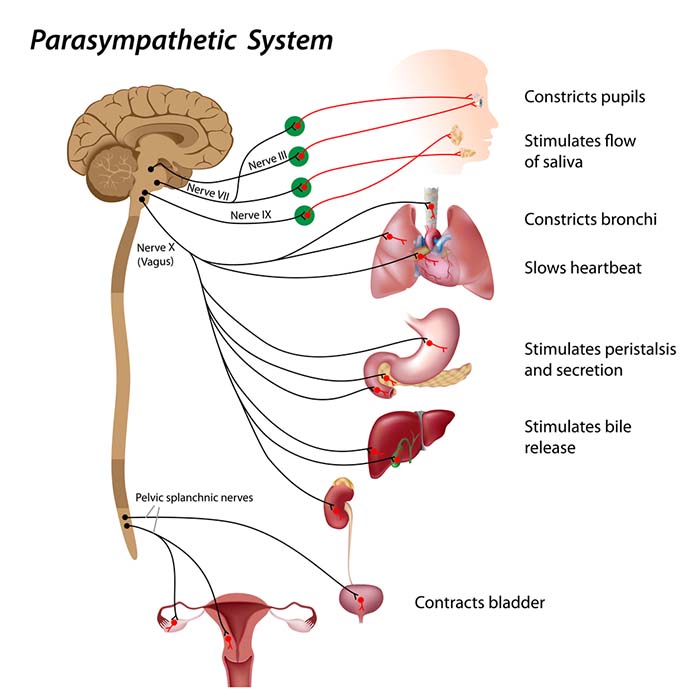

The Parasympathetic Division: Rest, Digest, and Connect

The parasympathetic division, or parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), regulates activities that increase the body's energy reserves, including salivation, gastric (stomach) and intestinal motility, gastric juice secretion, and increased blood flow to the gastrointestinal system. Think of it as your body's "rest and digest" system (Gentile et al., 2024; Karemaker, 2017). When we discuss Porges' polyvagal theory, we will learn that this system is also involved in self-regulation, social engagement, and passive responses to inescapable threats.

Listen to a mini-lecture on the Parasympathetic Nervous System FunctionHRV biofeedback uses slow-paced breathing and rhythmic skeletal muscle contraction to restore healthy parasympathetic activity.

PNS cell bodies are found in the nuclei of four cranial nerves (especially the vagus) and the spinal cord's sacral region (S2-S4). The parasympathetic division is craniosacral.

Listen to a mini-lecture on the Parasympathetic Nervous System OrganizationUnlike the sympathetic division, parasympathetic ganglia are located near their target organs. This arrangement means that preganglionic axons are relatively long, postganglionic axons are relatively short, and PNS changes can be selective.

Preganglionic neurons travel with the oculomotor, facial, glossopharyngeal, and vagus cranial nerves. Preganglionic neurons that exit the vagus (X) nerve at the medulla synapse with terminal ganglia within the heart, lungs, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, liver, and intestines. Both PNS preganglionic and postganglionic axons release acetylcholine (Fox & Rompolski, 2025).

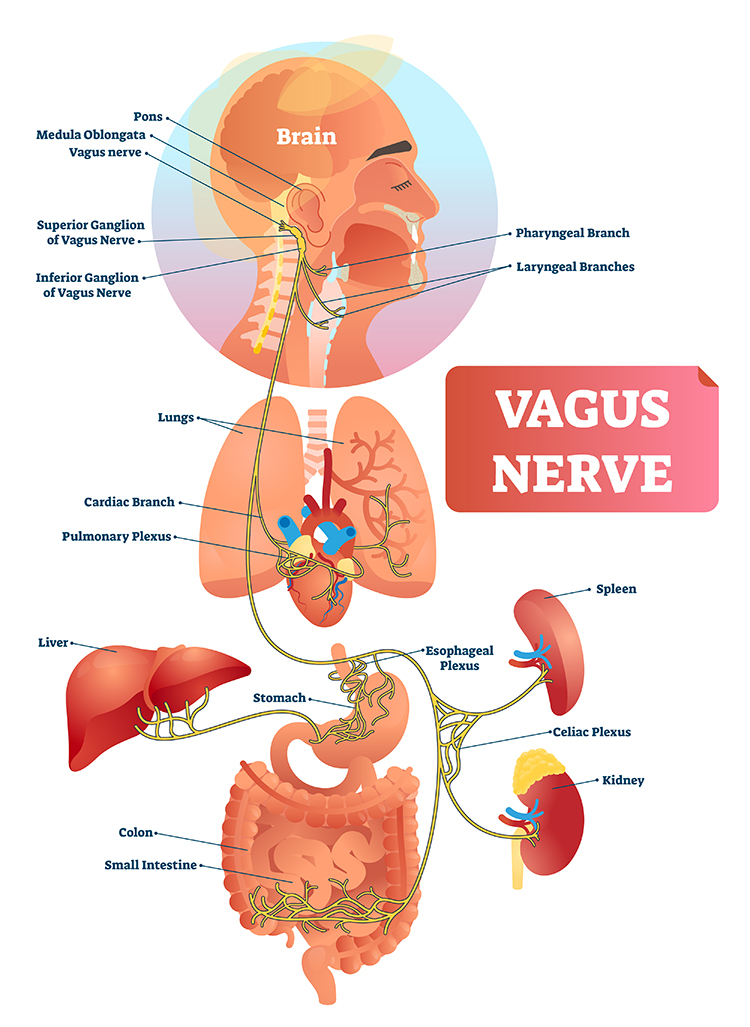

The Vagus Nerve: A Major Parasympathetic Pathway

The vagus nerve is the main parasympathetic nerve going from the brainstem to the heart, lungs, and digestive organs (Olshansky et al., 2008; Rajendran et al., 2023). Its efferent fibers (outgoing signals) release the chemical messenger acetylcholine at the heart, slowing the natural pacemaker and reducing heart rate, especially on a beat-to-beat time scale (Draghici & Taylor, 2016; Rajendran et al., 2018). Most vagus nerve fibers are actually afferent, meaning they carry sensory information from the heart and other organs back to the brain, where this information helps adjust both parasympathetic and sympathetic output (van Weperen & Vaseghi, 2023).

Because vagal signals can rapidly slow the heart and inhibit sympathetic drive, many therapies for heart disease and stress aim to enhance vagal activity, either with drugs, breathing and relaxation techniques, or electrical vagus nerve stimulation (Gentile et al., 2024; Pérez-Alcalde et al., 2024).

Sympathetic Fibers Inside the Vagus Nerve

Although the vagus nerve is usually taught as a parasympathetic nerve, human anatomical studies show it also contains a small but real sympathetic component. In carefully analyzed human cervical vagus nerves, about 13 to 14 percent of fibers had sympathetic characteristics, identified by a marker enzyme called tyrosine hydroxylase (Kronsteiner et al., 2024). Another study of more than 100 human vagus nerves found that sympathetic fibers made up around four to six percent of the total cross-sectional area, and that these fibers were scattered or clustered in different patterns from person to person (Seki et al., 2014).

This mixing means that stimulating the vagus in the neck, for example in implanted vagus nerve stimulation for epilepsy or heart failure, may activate not only parasympathetic fibers but also some sympathetic fibers, which could partially explain why heart rate responses and side effects vary between patients (Gentile et al., 2024; Seki et al., 2014).

Dr. Gevirtz provides an overview of the parasympathetic branch © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

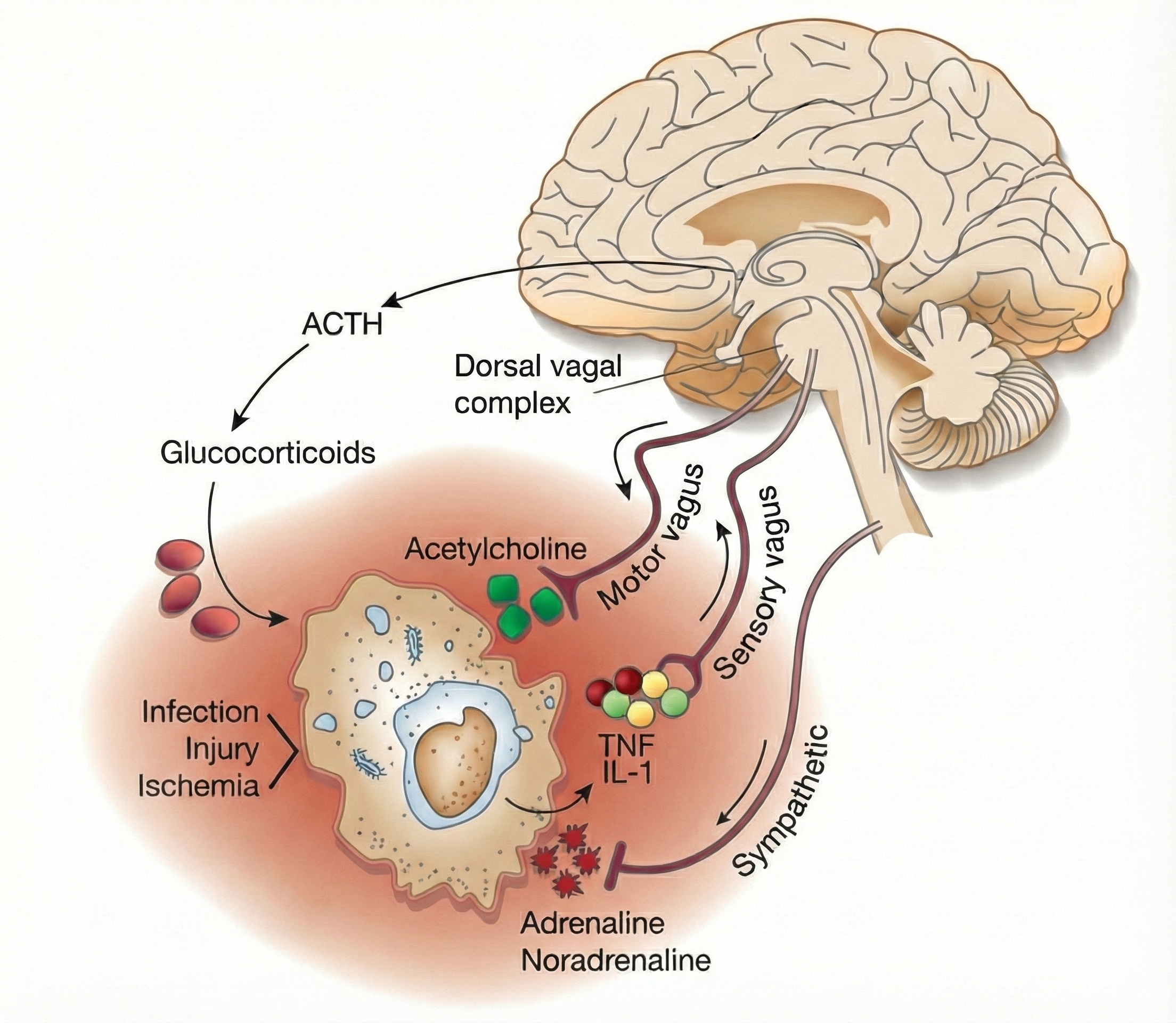

Dampening Inflammation

The vagus nerve's sensory branch detects inflammation and infection via tissue necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 (IL-1). The motor branch of the vagus signals descending neurons to release norepinephrine, which prompts spleen immune cells to release acetylcholine to macrophages to dampen inflammation (Schwartz, 2015).

The vagal cholinergic cytokine control system may be influenced by resonance-frequency (RF) breathing (Gevirtz, 2013; Tracey, 2007).

Read the Science News article Viva vagus: Wandering nerve could lead to range of therapies.

Chronic inflammation is implicated in a wide range of disorders, including Alzheimer's, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, depression, and diabetes (Dhar, Lambert, & Barton, 2016; Poole, Dickens, & Steptoe, 2011). See the Cutting Edge section later in this unit for more on the inflammatory reflex and how HRV biofeedback may influence neuroimmune regulation.

A Modern View of Sympathetic-Parasympathetic Interaction

Instead of one branch turning fully on while the other turns fully off, both branches are usually active at the same time, with their levels constantly adjusted to keep blood pressure, heart rate, and other functions in a healthy range (Karemaker, 2017; Khan et al., 2019). The heart receives input from both systems simultaneously, and their combined signals set the actual heart rate from moment to moment (Draghici & Taylor, 2016; Rajendran et al., 2018). In many situations both branches change together, rather than in a simple seesaw pattern, so researchers now talk less about a single "sympatho-vagal balance" and more about a flexible, context-dependent interaction (Ernst, 2017; Karemaker, 2017).

Putting this together, current perspectives see the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches as partners in a coordinated control system rather than simple rivals. The sympathetic branch provides energy and support for challenge, while the parasympathetic branch, especially through the vagus nerve, provides rapid braking and fine-tuning, with HRV serving mainly as a window into this vagal control (Ernst, 2017; Gentile et al., 2024). The discovery that the human vagus nerve contains a noticeable minority of sympathetic fibers adds nuance: even "parasympathetic" pathways carry mixed information, and therapies that target the vagus may influence both branches at once (Kronsteiner et al., 2024; Seki et al., 2014). For students and clinicians, this means thinking less in terms of a simple on-off switch and more in terms of a flexible, bidirectional conversation between sympathetic and parasympathetic influences that continuously shapes heart function and overall health (Karemaker, 2017; Khan et al., 2019).

Key Takeaways: Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Divisions

The SNS mobilizes your body for action, expending stored energy during emergencies. The PNS restores and conserves energy, promoting "rest and digest" functions. Rather than working like a simple seesaw, both branches are usually active simultaneously, with their levels constantly adjusted to maintain homeostasis. The vagus nerve plays a particularly important role in rapid heart rate control and dampening inflammation, which has implications for treating chronic conditions. Most HRV indices primarily reflect parasympathetic rather than sympathetic activity.

Comprehension Questions: The Autonomic Nervous System

- How does the psychophysiological principle explain the relationship between Botox injections and emotional experience?

- Your client Sarah shows decreased hand temperature and increased respiration rate during stress. How would you use this response stereotypy information in treatment planning?

- Why does the SNS produce "mass activation" while the PNS can produce more selective responses?

- Explain how vagal withdrawal differs from sympathetic activation in response to everyday stressors.

- How might HRV biofeedback influence the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway?

- Why is the vagus nerve not a purely parasympathetic pathway?

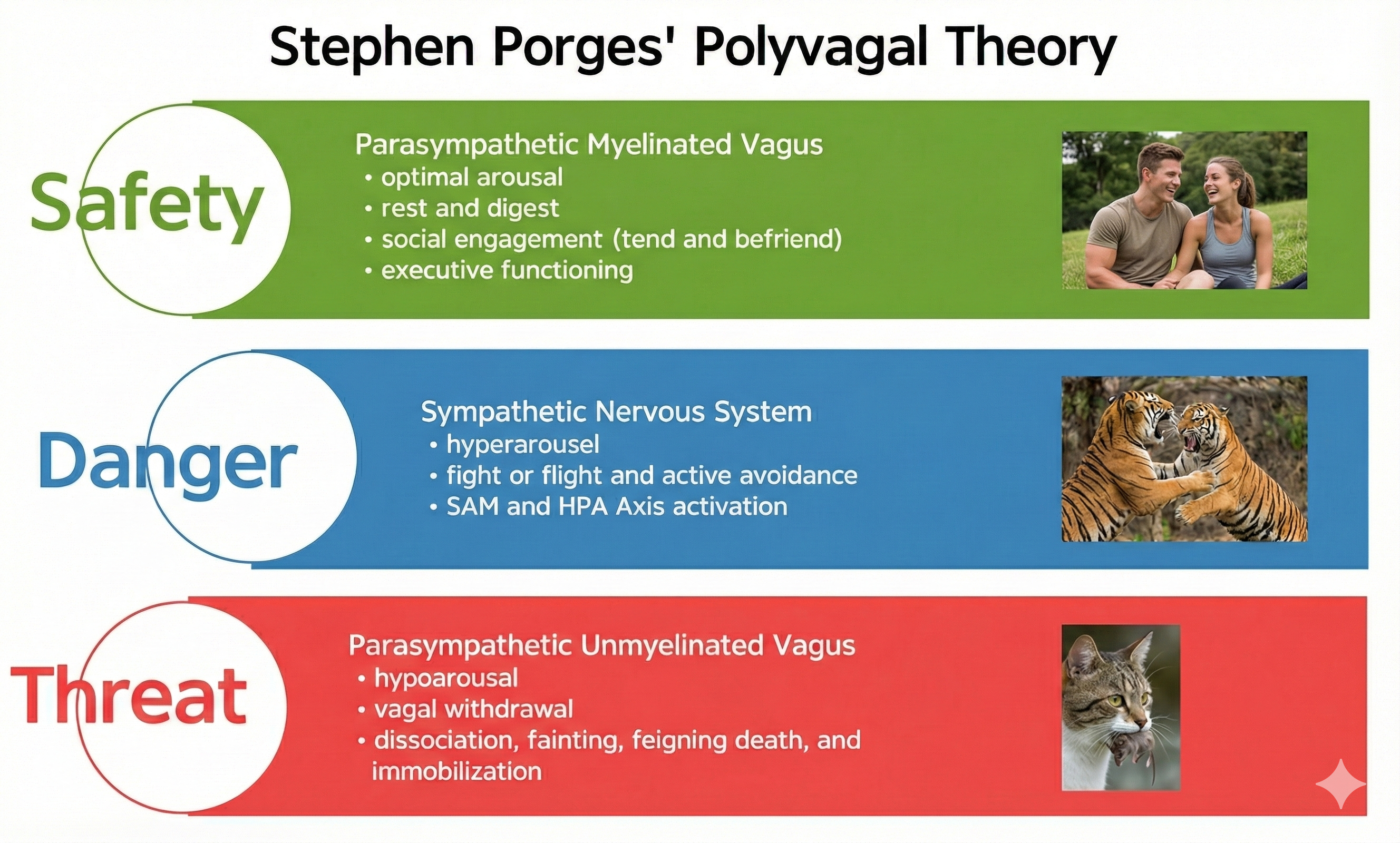

Porges' Polyvagal Theory: Beyond Fight or Flight

Polyvagal theory tells a story about how our bodies react to safety and danger. Instead of seeing the ANS as a simple "on/off" switch between rest-and-digest and fight-or-flight, Stephen Porges argues that mammals have three main response systems, arranged in a rough hierarchy (Porges, 1995, 2007, 2021). The oldest system, linked to an unmyelinated vagus nerve, supports shutdown and "freeze." The sympathetic system supports fight-or-flight. The newest system, the ventral vagal complex, is said to connect the heart with the face and voice muscles, supporting social engagement, calm states, and feelings of safety (Porges, 2003, 2007, 2021).

The vagus, the 10th cranial nerve, inhibits the heart and increases bronchial tone in the lungs. The vagus contains specialized subsystems that control competing adaptive responses, such as tend-and-befriend versus freezing.

According to Porges' (2011) fascinating and controversial theory, the ANS must be considered a "system," with the vagal nerve containing specialized subsystems that regulate competing adaptive responses. His theory proposes competing roles for the unmyelinated fibers in the vagus, which originate in the dorsal motor complex, and newer myelinated nerves which originate in the nucleus ambiguus.

The Ventral Vagal Complex: Our Social Engagement System

Porges theorizes that the evolution of the ANS was central to developing emotional experience and affective processes involved in social behavior. As human beings, we are not limited to fight, flight, or freezing behavioral responses. When we encounter stressors, we can self-regulate and initiate pro-social behaviors, including the tend-and-befriend response.

Porges calls this the social engagement system, and the theory suggests that this system depends upon the healthy functioning of the myelinated vagus, a vagal brake. From Porges' perspective, we only activate the myelinated vagus when our nervous system perceives that we are safe. Social engagement is a mutual process and may be integral to playing with others.

Social engagement often involves eye contact.

Social engagement also includes voluntary close physical proximity.

The myelinated vagus enables us to self-regulate, calm ourselves, and inhibit sympathetic outflow to the heart. It allows us to engage prefrontal cortex executive functions such as attention and mindfulness.

Professionals increasingly provide HRV biofeedback training before starting neurofeedback to activate the prefrontal cortex.

Daily stressors inhibit the myelinated vagus, producing vagal withdrawal, interfering with attention and social engagement.

In contrast, positive events may produce happiness that facilitates the myelinated vagus while increasing sympathetic activation.

The SNS in Polyvagal Context

The SNS, in concert with the endocrine system, responds to threats to our safety through mobilization, which includes fight-or-flight and active avoidance. The SNS responds more slowly and for a more extended period (more than a few seconds) than the parasympathetic vagus system.

The SNS inhibits the unmyelinated vagus to mobilize us for action instead of fainting or freezing. In contrast, the parasympathetic myelinated vagus rapidly adjusts cardiac output, promotes social engagement (the tend-and-befriend response), and enables self-regulation. These three changes promote biofeedback training.

According to this theory, quality communication and pro-social behaviors are possible only when defensive circuits are inhibited (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).

The Unmyelinated Vagus: When Fight and Flight Are Not Options

Porges hypothesizes that the unmyelinated fibers regulate the freeze response and respond to threats through immobilization, feigning death, passive avoidance, and shutdown. Check out the YouTube video The Polyvagal Theory and PTSD with Stephen Porges, PhD.

Summary of Polyvagal Theory's Three Systems

When our nervous system perceives safety, we activate the ventral vagal complex (myelinated vagus) to conserve and rebuild energy stores (rest and digest), socially bond with others (tend and befriend), and engage in executive functions like self-regulation and planning.

When our nervous system perceives danger, we activate the SNS and the endocrine system's SAM pathway and HPA axis and inhibit the unmyelinated vagus, for fight or flight or active avoidance.

When our nervous system perceives that our life is threatened and that fight, flight, or active avoidance will not succeed (like a mouse in the jaws of a cat), we activate the unmyelinated vagus (dorsal vagal complex). This results in passive avoidance through dissociation, fainting, feigning death, immobilization, and shutdown.

Neuroception: The Body's Safety Scanner

A key idea in polyvagal theory is neuroception: the nervous system is constantly and automatically "scanning" for cues of safety or threat (tone of voice, facial expression, posture), and then shifting bodily state in ways that shape emotion, attention, digestion, and how open or defensive we feel in relationships (Porges, 2007; Porges, 2022). Because of this, the theory has become popular in trauma therapy, developmental psychology, and creative arts therapies as a way to explain why warm relationships, prosodic voice, music, and movement can help people feel safer and more regulated (Beauchaine et al., 2007; Fox, 2025; Haeyen, 2024; Porges, 2017).

Scientific Status of Polyvagal Theory

The status of polyvagal theory in science is more complicated than its clinical popularity might suggest. On the supportive side, many studies link measures thought to reflect vagal regulation, especially respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), a pattern in heart rate tied to breathing, to social behavior, emotion regulation, and mental health problems. Some reviews argue that new work in neuroscience and clinical research fits reasonably well with core polyvagal ideas (Beauchaine et al., 2007; Manzotti et al., 2023; Porges, 2022, 2025). Clinicians also report that polyvagal language about "states," "safety," and "co-regulation" helps them design and explain body-based, relational interventions (Fox, 2025; Haeyen, 2024; Koenig, 2025; Schroeter, 2016).

On the critical side, recent papers argue that several basic biological claims are wrong or overstated. For example, critics contend that certain vagal pathways do not cleanly map onto specific behaviors, that RSA is not uniquely mammalian, and that reptiles are not essentially "asocial" compared to mammals as the theory suggests. Critics also argue that relying on RSA as a one-to-one measure of "vagal tone" is a conceptual mistake (Doody et al., 2023; Grossman, 2023). Even authors generally sympathetic to the framework describe it as a useful, integrative model that still needs revision to match what is known from comparative anatomy and neurobiology (Manzotti et al., 2023).

Right now, polyvagal theory is highly influential in clinical practice and as a metaphor for safety and connection, while its detailed evolutionary and anatomical story remains debated and only partly supported.

Clinical Application: Understanding Your Client's Nervous System State

Consider a client named Elena who comes to you after experiencing trauma. She describes feeling "checked out" during stressful situations and has difficulty connecting with others. Through the lens of polyvagal theory, you recognize that Elena's nervous system may be defaulting to unmyelinated vagal responses (shutdown, dissociation) rather than engaging the social engagement system. Your treatment approach might focus on helping Elena's nervous system recognize safety cues, perhaps starting with HRV biofeedback to strengthen myelinated vagal function before addressing more complex therapeutic goals.

Key Takeaways: Polyvagal Theory

Polyvagal theory proposes three hierarchically arranged response systems rather than a simple on/off switch. The ventral vagal complex (myelinated vagus) supports social engagement and self-regulation when we feel safe. The sympathetic system mobilizes us for active responses to danger. The dorsal vagal complex (unmyelinated vagus) produces shutdown responses when escape seems impossible. The concept of neuroception explains how our nervous system automatically scans for safety and threat cues. Understanding which system your client's nervous system defaults to can guide treatment planning. While polyvagal theory is highly influential clinically, its detailed biological claims remain debated in the scientific literature.

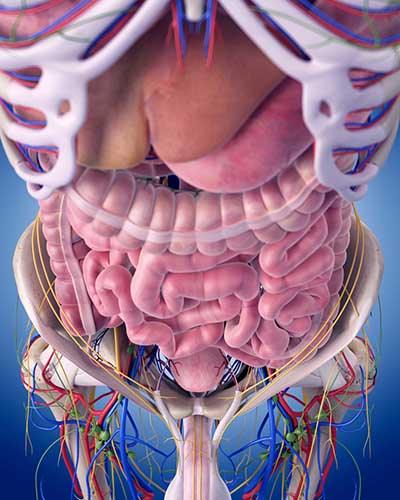

The Enteric Division: Your Second Brain

The story of the gut-brain axis starts with the enteric nervous system (ENS), sometimes called the "second brain." Wrapped in layers along the gastrointestinal tract, the ENS contains hundreds of millions of neurons, comparable to the spinal cord (Boron & Boulpaep, 2005), organized into two main networks: the myenteric plexus and submucosal plexus. These networks can sense what is in the gut and coordinate motility, secretion, blood flow, and local immune responses, often without direct orders from the brain (Carabotti et al., 2015; Kulkarni et al., 2018). The ENS is now widely accepted as a major division of the peripheral nervous system with broad influence on digestion, metabolism, and inflammation (Hajjeh et al., 2025; O'Riordan et al., 2025).

Here is a surprising fact: the gut contains more than 90% of the body's serotonin (Khazan, 2013) and about 50% of its dopamine. The ENS releases a comparable range of neurotransmitters as the central nervous system (Gershon, 1999) and contains interneurons, sensory neurons, autonomic motor neurons, and neuroglial cells. A subset of intestinal sensory neurons travels in the vagus nerve to influence ANS activity (Fox & Rompolski, 2025). Check out the Khan Academy YouTube video Control of the GI Tract.

Modern imaging and genetic tools show that enteric neurons and glial cells constantly communicate with epithelial cells, immune cells, and gut microbes, forming a local control center rather than a passive relay (Dowling et al., 2022; Kulkarni et al., 2018). While the ENS locally regulates intestinal functions, sympathetic and parasympathetic efferents can override its activity during intense emotions like anger and fear (Fox & Rompolski, 2025). During physical activity and stress, sympathetic firing inhibits intestinal motility. During rest, parasympathetic firing promotes motility by exciting enteric preganglionic neurons (Khazan, 2013).

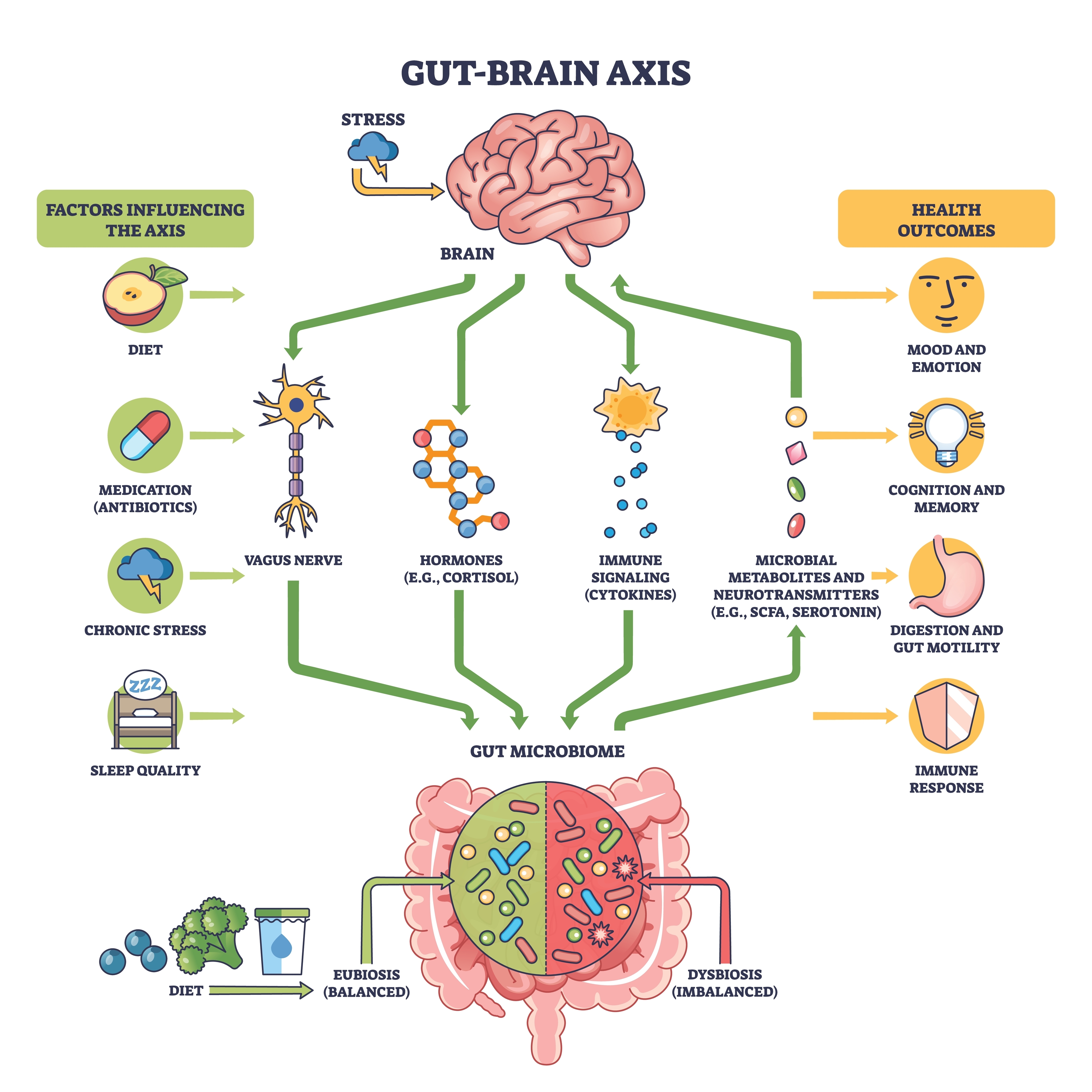

The Gut-Brain Axis

The gut-brain axis describes the two-way communication between this "second brain," the central nervous system, and the gut environment, including the microbiota. Signals travel along several routes at once: fast neural pathways (vagus nerve, spinal afferents, ENS circuits), hormonal systems such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) stress axis, and immune and metabolic signaling through cytokines and microbial metabolites (Carabotti et al., 2015; Hattori & Yamashiro, 2021; Rusch et al., 2023).

Trillions of microbes in the gut add another layer, producing short-chain fatty acids, neurotransmitter-like chemicals, and other metabolites that can act on enteric neurons, endocrine cells, and immune cells, indirectly shaping brain function and behavior (Chen et al., 2021; Cryan et al., 2019; Schneider et al., 2024). The current consensus is not that the microbiota "controls your mind," but that there is a real, biologically grounded microbiota-gut-brain axis influencing stress reactivity, mood, and cognition, especially under conditions of imbalance or disease (Cryan et al., 2019; Mohajeri et al., 2018; Petrut et al., 2025).

Research Evidence

Evidence for this axis comes from multiple directions. In animals, raising mice without microbes or disrupting their gut flora with antibiotics changes gut metabolites, alters expression of brain signaling molecules, and impairs certain types of memory, supporting a causal link from gut to brain (Fröhlich et al., 2016; Rusch et al., 2023). Germ-free or dysbiotic animals also show abnormal stress responses and altered neurogenesis, which can sometimes be normalized by restoring microbes (Cryan et al., 2019; Schneider et al., 2024).

In humans, gut dysbiosis is associated with irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety and depression, autism spectrum conditions, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease. Specific microbial profiles correlate with cognitive markers and Alzheimer's biomarkers in people with mild cognitive impairment (Carabotti et al., 2015; Fan et al., 2025; Hajjeh et al., 2025). These associations do not prove direct causation in all cases, but together with mechanistic animal work, they strongly support the idea that gut microbes and the ENS help tune brain circuits involved in mood, stress, and cognition (Chen et al., 2021; Mohajeri et al., 2018).

Stress, Diet, and the Microbiome

This gut-brain conversation has practical consequences for health and performance. Stress signals from the brain can alter gut motility, barrier function, and microbiota composition via the HPA axis and ANS, sometimes promoting overgrowth of harmful bacteria and inflammation (Carabotti et al., 2015; Hattori & Yamashiro, 2021; Ramadan et al., 2025). In the other direction, microbial metabolites and ENS activity influence appetite, energy use, and glucose handling, affecting body weight and metabolic risk (Nikolla et al., 2025; Schneider et al., 2024).

Diet emerges as a key lever: what people eat reshapes the microbiota and its metabolites, which can in turn modulate stress resilience, learning, and emotional regulation through immune, endocrine, and neural pathways (Cryan et al., 2019; Schneider et al., 2024; Wójcik et al., 2025). Early work on psychobiotics (probiotics or prebiotics aimed at mental health) and dietary interventions suggests modest but promising benefits for mood and cognitive performance in some groups, though effects are strain- and context-dependent and far from a universal "fix" (Mohajeri et al., 2018; Petrut et al., 2025; Schneider et al., 2024).

Clinical Implications

Current thinking views the ENS and gut-brain axis as central regulators of whole-body homeostasis rather than curiosities on the side. ENS dysfunction is now proposed as a driver, not just a marker, of neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders, helping to explain why gastrointestinal problems are so common in conditions like Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and autism spectrum disorder (Cryan et al., 2019; Dowling et al., 2022; Hajjeh et al., 2025). At the same time, clinical translation is still in early stages: many striking findings come from animal models, human data are often correlational, and individual responses vary widely (Chen et al., 2021; O'Riordan et al., 2025; Schneider et al., 2024).

Even with these caveats, the gut-brain axis offers a powerful framework for understanding how stress, diet, infection, and microbiota shape mental and physical performance, and hints that future therapies may target not just the brain, but also the "second brain" and the microbes that live alongside it.

The Relationship Between the Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Branches

Berntson, Cacioppo, and Quigley (1993) challenge the concept of a continuum ranging from SNS to PNS dominance. They argue that the two autonomic branches do not only act antagonistically (reciprocally). They also exert complementary, cooperative, and independent actions.

Antagonistic Actions

The SNS and PNS branches compete to control target organs such as the heart. For example, the PNS can slow the heart by 20 to 30 beats per minute or briefly stop it (Tortora & Derrickson, 2023). Since these divisions generally produce contradictory actions, like speeding and slowing the heart, their effect on an organ depends on their current balance of activity. This competitive relationship is called accentuated antagonism (Olshansky et al., 2011).

This adrenergic and cholinergic effects table was adapted from Fox and Rompolski (2022). Adrenergic receptors are alpha (α) or beta (β), and cholinergic receptors are muscarinic (M).

Complementary Actions

SNS and PNS actions are complementary when they produce similar changes in the target organ. Saliva production serves as an example. PNS activation produces watery saliva, and SNS activation constricts salivary gland blood vessels producing thick saliva.

Cooperative Actions

SNS and PNS actions are cooperative when their different effects result in a single action. Sexual function provides an example. PNS activation produces erection and vaginal secretions, while SNS activation produces ejaculation and orgasm.

Exclusive Sympathetic Control

The SNS exclusively innervates several organs. They are controlled by increasing or decreasing the firing of SNS postganglionic fibers: adrenal medulla, arrector pili muscle, sweat glands, and most blood vessels.

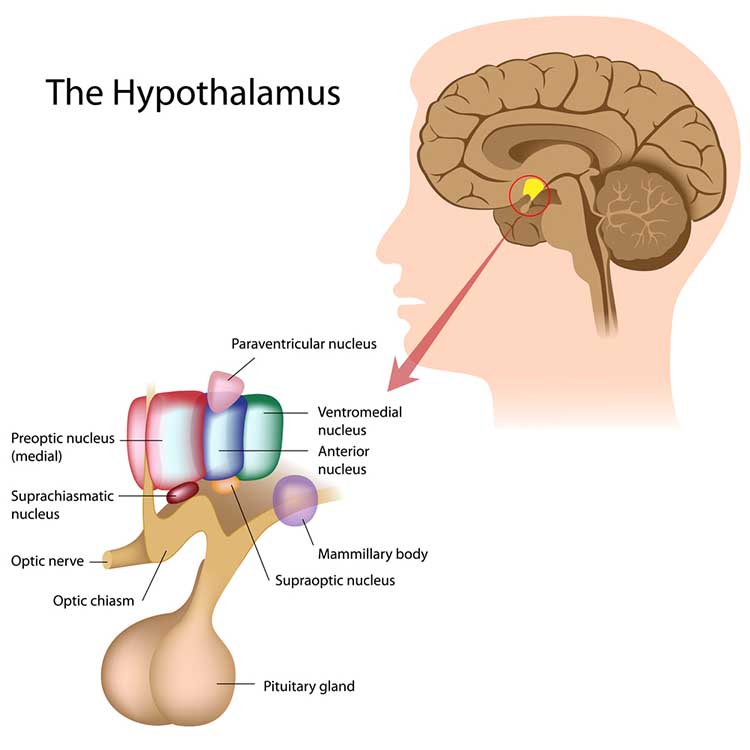

Higher Brain Center Control

The brainstem's medulla regulates blood pressure, defecation, heart rate, respiration, and vomiting, distributes signals between the brain and spinal cord, and directly controls the ANS. The medulla is influenced by sensory input and the hypothalamus (Breedlove & Watson, 2023).

The hypothalamus is a forebrain structure located below the thalamus. The hypothalamus is the body's homeostat (a device that maintains homeostasis) and dynamically maintains balance through its control of the ANS, endocrine system, survival behaviors, and interconnections with the immune system. The hypothalamus consists of specialized nuclei.

The hypothalamus is influenced by the cerebellum, cerebral cortex, and limbic system.

Comprehension Questions: ANS Branches and Their Relationships

- Explain why the enteric nervous system is sometimes called the "second brain."

- Give an example of how the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions work cooperatively rather than antagonistically.

- According to polyvagal theory, what must happen for a client to engage in effective social communication during therapy?

- How does the hypothalamus function as a "homeostat"?

Homeostasis: Maintaining Your Internal Balance

Homeostasis maintains the body's internal environment within healthy physiological limits. Think of it like a thermostat in your home. Claude Bernard introduced the basic concept of homeostasis and stated, "The stability of the internal environment is the condition of a healthy life." Cannon (1939) introduced the term homeostasis in 1932 and elaborated on this concept in The Wisdom of the Body.

The body achieves homeostasis for specific variables, like blood pressure, through interlocking negative and positive feedback systems. Check out the Bozeman Science YouTube video Positive and Negative Feedback Loops.

Two important modifications to the principle of homeostasis are the boundary model and allostasis.

The boundary model challenges the maintenance of set points as rigid and proposes that physiological processes are maintained within acceptable ranges.

Allostasis means the maintenance of stability through change and is a process that complements homeostasis. Allostasis is achieved by anticipating challenges and adapting through behavior (including learning) and physiological change. Therapists utilize allostasis when they teach patients to use an abbreviated relaxation exercise (low-and-slow breathing) when they anticipate stressors like traffic jams.

The Allostatic Load Model: When Stress Takes Its Toll

The allostatic load model begins with a familiar experience: life keeps throwing demands at the body, and the body must constantly adjust to stay in balance. These adjustments, like speeding up the heart, raising blood pressure, or releasing stress hormones so we can cope, are called allostasis. Allostatic load is the "wear and tear" that builds up when these stress responses are activated too often, for too long, or do not shut off properly (Guidi et al., 2020; Juster et al., 2010; Logan & Barksdale, 2008). Instead of focusing on a single organ, researchers measure allostatic load with a bundle of markers from several systems, such as blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, inflammatory markers, and sometimes stress hormones, to capture how strained the body has become (Juster et al., 2010; Rodriguez et al., 2019).

Research Support for the Allostatic Load Model

Over the last 30 years, research has largely supported the core idea that higher allostatic load reflects harmful "biological wear and tear" from chronic stress. People with higher scores are more likely to have heart disease, cognitive problems, pain conditions, mental health issues, disability, and higher risk of death, even after controlling for standard medical risk factors (Guidi et al., 2020; Juster et al., 2010; Rabey & Moloney, 2022). Large analyses show that a relatively small set of markers, such as inflammation (C-reactive protein), resting heart rate, good cholesterol, waist-to-height ratio, and long-term blood sugar, can already predict slower walking, weaker grip strength, poorer self-rated health, and higher mortality (McCrory et al., 2023).

Studies also find that allostatic load tends to be higher in people facing long-term adversity, such as low income, discrimination, or demanding jobs, and in some student groups with more stress and sleep problems, helping explain why some social groups have worse health than others (Christensen et al., 2022; Igboanugo & Mielke, 2023; Liu et al., 2025; Rodriguez et al., 2019).

Refining the Allostatic Load Model

Current thinking is not that the model is perfect, but that it is useful and needs refining. One major debate is how best to measure allostatic load: different studies use different biomarkers, cutoffs, and scoring rules, which makes it hard to compare results or set clear clinical thresholds (Carbone et al., 2022; Guidi et al., 2020). Newer work is pushing toward a shared definition and simpler, standardized scores that clinicians could actually use with patients (Fava et al., 2022; McCrory et al., 2023).

Researchers are also expanding the model. For example, some frame allostatic load as an energetic cost problem, where chronic stress forces the body to spend so much energy on survival that it has less left for repair and healthy aging (Bobba-Alves et al., 2022). Others apply the idea to relationships and groups, talking about social allostatic load when stressed groups get stuck in unhealthy interaction patterns (Saxbe et al., 2019).

Overall, the allostatic load model is widely accepted as a powerful way to connect chronic stress with multi-system bodily change, even as scientists work to clarify exactly how to define, measure, and apply it.

Autonomic Balance: Finding the Middle Ground

Wenger's idea of autonomic balance centers on the relationship between the sympathetic ("fight or flight") and parasympathetic ("rest and digest") branches of the autonomic nervous system. In his classic view, healthy functioning depends on a dynamic balance between these two systems; too much sympathetic activity or too little parasympathetic tone leads to autonomic imbalance and vulnerability to disease.

Wenger (1972) proposed that resting individuals are located along a continuum ranging from SNS to PNS dominance. Normally distributed A-bar scores, which measure location on this continuum, are calculated from a battery of autonomic measurements. Low A-bar scores indicate SNS dominance, while high A-bar scores suggest PNS dominance. Most subjects show intermediate scores. Wenger and colleagues reported that individuals with low A-bar scores, whom he called sympathicotonics, suffered an elevated incidence of neurotic, psychotic, psychosomatic, and medical disorders.

Generally, low and high A-bar scores seem to predispose individuals to develop psychological and medical disorders. Where SNS dominance (low A-bar scores) may result in cardiac arrhythmia and essential hypertension, PNS dominance (high A-bar scores) may be associated with asthma, colitis, and hypotension.

Modern Support for Autonomic Balance

Modern research broadly supports the intuition that chronic sympathetic dominance with reduced parasympathetic activity is harmful. This pattern is linked to cardiovascular disease, increased mortality, and multiple risk factors such as hypertension, obesity, and chronic stress, often indexed by reduced HRV as a marker of low parasympathetic tone and autonomic imbalance (Thayer et al., 2010; Zoccali et al., 2025). Similar imbalances have been implicated in chronic kidney disease, where sympathetic overactivity and diminished vagal (parasympathetic) influence promote inflammation and cardiovascular complications (Zoccali et al., 2025).

Beyond the Simple Seesaw Model

However, the simple "seesaw" version of autonomic balance, where sympathetic and parasympathetic activity are treated as exact opposites on a single line, is now seen as too crude. Work on autonomic "modes of control" shows that the two branches can change reciprocally, independently, or even rise and fall together, creating a richer autonomic space than a one-dimensional balance score can capture (Berntson, 2018; Quigley & Moore, 2018).

This has led to more nuanced composite measures such as cardiac autonomic balance (CAB) and cardiac autonomic regulation (CAR), which distinguish relative dominance of one branch from overall co-activation or co-inhibition and better predict outcomes like myocardial infarction, neuroinflammation, and emotional functioning (Berntson, 2018; Stone et al., 2020).

Limitations of the LF/HF Ratio

HRV remains a central noninvasive tool for assessing autonomic function, but influential reviews argue that LF HRV and the LF/HF ratio do not reliably reflect sympathetic tone or true "sympathovagal balance," and that much of the HRV spectrum is actually shaped by the parasympathetic system (Billman, 2013; Hayano & Yuda, 2021; Reyes del Paso et al., 2013; von Rosenberg et al., 2017).

Contemporary Understanding of Autonomic Balance

Today, Wenger's core insight, that coordinated sympathetic and parasympathetic activity, rather than either system alone, is crucial for health, still guides research, but the measurement and theory have grown more sophisticated. Instead of treating "autonomic balance" as a single ratio like LF/HF, current models emphasize multi-dimensional patterns across organs and time, grounded in brain-body networks that integrate emotion, cognition, and physiology (Ernst, 2017; Quigley & Moore, 2018; Thayer & Brosschot, 2005).

Autonomic imbalance is now framed as a common pathway linking chronic negative affect, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk, with HRV and related indices used as biomarkers of this broader regulatory system (Olivieri et al., 2024; Thayer et al., 2010; Zoccali et al., 2025). In this sense, Wenger's concept survives as a powerful metaphor and starting point, but contemporary science treats "balance" as a flexible, brain-embedded control strategy rather than a simple numerical score.

Heart Rate Variability: A Window into Brain-Heart Communication

HRV is the natural variation in the time between consecutive heartbeats, usually measured from the R waves on an electrocardiogram and expressed as changing interbeat intervals over time (Acharya et al., 2006; Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). A healthy heart is not a perfect metronome but speeds up and slows down slightly from beat to beat, allowing rapid adjustment to physical and emotional demands (Kara et al., 2003; Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). Higher HRV at rest is generally associated with better cardiovascular health and resilience, while very low HRV often appears in serious heart disease and is linked to higher risk of death after events such as heart attacks (Acharya et al., 2006; Tiwari et al., 2020). Modern reviews emphasize that HRV should be viewed as a dynamic signal that reflects how flexibly the heart and the nervous system can respond to changing situations across seconds, hours, and even years (Ernst, 2017; Kemp et al., 2017).

Autonomic and Physiological Sources of HRV

HRV mainly arises from the ANS, which includes the sympathetic branch that prepares the body for action and the parasympathetic branch that supports rest and recovery (Acharya et al., 2006; Tiwari et al., 2020). Fast beat-to-beat changes are driven largely by the vagus nerve, the main parasympathetic nerve to the heart, which can quickly slow the heart in response to breathing and other reflexes (Ernst, 2017; Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). This vagal influence shows up strongly in time-domain measures such as RMSSD and in HF power in frequency-domain analysis (Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017; Tiwari et al., 2020).

Slower oscillations in HRV reflect a mix of baroreflex activity, sympathetic influences, thermoregulation, and other processes, which makes their interpretation more complex (Ernst, 2017; Stauss, 2003). Recent work also notes that especially in older adults, some increased variability can come from disorganized or fragmented sinus rhythm that is not purely autonomic in origin, reminding researchers to interpret HRV with care (Arakaki et al., 2023).

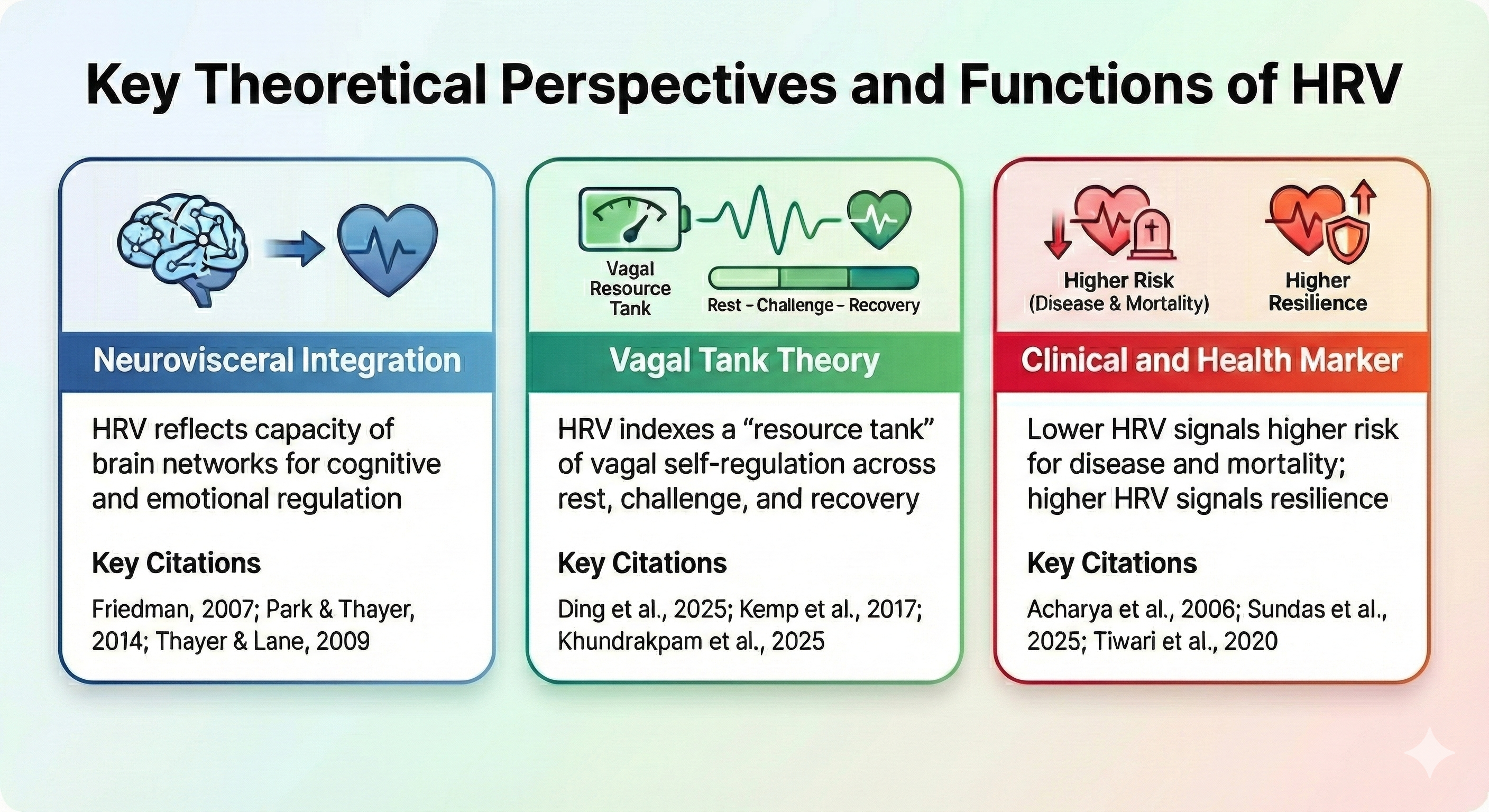

The Neurovisceral Integration Model

Modern theories see HRV not only as a cardiac signal but also as an indirect reflection of brain-heart communication. The neurovisceral integration model proposes that vagally mediated HRV, especially HF HRV, indexes the functional capacity of a network of brain regions called the central autonomic network (CAN), which links areas involved in attention, emotion, and autonomic control (Thayer & Lane, 2000, 2009). Higher resting HRV tends to be associated with better executive functions, such as working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibition, as well as more effective emotion regulation (Park & Thayer, 2014; Thayer & Lane, 2009).

In this view, the same prefrontal brain circuits that help a person shift attention or control impulses also send inhibitory signals down to autonomic centers, using the vagus nerve to "brake" the heart and dampen excessive stress responses (Friedman, 2007; Thayer & Lane, 2009). HRV therefore acts as a convenient peripheral marker of how well these brain networks can support self-regulation, adaptation, and health.

Vagal Tank Theory

Vagal tank theory offers a more metaphorical but intuitive way to think about HRV. It suggests that cardiac vagal activity functions like a "tank" of regulatory resources that can be filled, used, and refilled over time, much like an energy reserve for self-control and coping (Ernst, 2017; Kemp et al., 2017). In this framework, resting HRV reflects the current "level" in the tank, phasic changes in HRV during a challenge reflect how much of that resource is recruited, and recovery HRV shows how well the tank is refilled after the task ends (Ding et al., 2025; Khundrakpam et al., 2025).

Experimental work using anxiety induction and HRV biofeedback training in college students has shown that higher resting HRV is associated with stronger vagal responses during stress and better recovery afterward, supporting the idea that a fuller vagal tank allows more flexible engagement and disengagement of regulation when needed (Ding et al., 2025). This theory has inspired interventions such as slow-paced breathing and HRV biofeedback that aim to "top up" vagal resources to improve stress management and emotional resilience (Khundrakpam et al., 2025; Moss, 2025).

HRV, Health, and Cognition

Across many studies, lower HRV has been linked to a wide range of problems including cardiovascular disease, anxiety, depression, and cognitive decline, whereas higher HRV is generally associated with better emotional well-being and cognitive performance (Friedman, 2007; Kemp et al., 2017; Tiwari et al., 2020). From a neurovisceral integration and vagal tank perspective, HRV helps indicate how flexibly a person can shift between states, such as from rest to focused effort and back to recovery, without getting "stuck" in chronic stress responses (Friedman, 2007; Park & Thayer, 2014).

For example, higher resting HRV has been associated with more adaptive attention to emotional stimuli and better affective flexibility, while lower HRV is linked to hypervigilance and less flexible responses to negative information (Grol & De Raedt, 2020; Park & Thayer, 2014). In psychotherapy and stress management, HRV training is being explored as a way to strengthen this flexibility, potentially improving affect regulation and social engagement by enhancing vagal function (Moss, 2025; Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017).

HRV as a Dynamic Biomarker

Current thinking treats HRV as a dynamic biomarker, meaning a measurable signal that tracks ongoing changes in autonomic and brain function over time rather than a fixed trait (Ernst, 2017; Sundas et al., 2025). Reviews describe how HRV can connect "psychological moments" such as daily stress or brief emotional experiences with long-term outcomes like healthy aging and mortality, by capturing how the vagus nerve and CAN manage repeated challenges across the lifespan (Kemp et al., 2017; Sundas et al., 2025).

At the same time, researchers warn that HRV is influenced by age, posture, breathing, measurement length, and even fragmented sinus rhythm, so careful protocols and interpretation are essential (Arakaki et al., 2023; Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017; Stauss, 2003). Overall, the latest models agree that HRV is more than just a simple index of "sympathetic versus parasympathetic balance." It is a rich signal reflecting how heart, brain, and body work together to support flexibility, self-regulation, and health across time (Ernst, 2017; Thayer & Lane, 2009).

Key Takeaways: Heart Rate Variability

HRV reflects the flexible, moment-to-moment adjustments of heart rate driven primarily by the vagus nerve. The neurovisceral integration model proposes that HRV indexes the brain's capacity for cognitive and emotional regulation through the CAN. Vagal tank theory offers an intuitive metaphor: HRV reflects a "resource tank" that can be depleted during stress and replenished during recovery. Higher resting HRV is generally associated with better cardiovascular health, cognitive flexibility, and emotional resilience, while low HRV signals higher risk for disease and mortality.

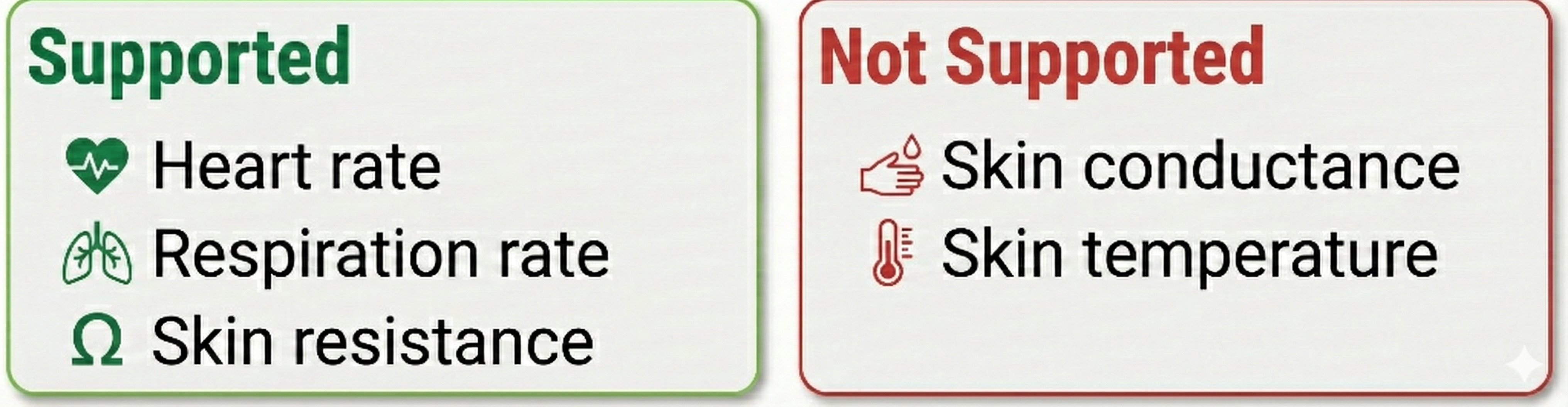

Psychophysiological Measurements: What We Monitor and Why

Psychophysiologists monitor tonic, phasic, and spontaneous psychophysiological activity.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Tonic and Phasic ActivityTonic activity measures background activity and is the magnitude of physiological activity over a specified period before stimulating the subject. A resting baseline, where a participant sits quietly without breathing or relaxation instructions or feedback for 3 or 5 minutes, measures tonic activity. Clinicians obtain pre- and post-baselines to measure the psychophysiological change in variables like HRV or hand temperature within and across training sessions.

Phasic activity is a discrete response evoked by a specific stimulus, like being surprised. Since subjects continuously react to environmental and internal stimuli that we cannot directly observe, interpreting phasic activity can be challenging.

Spontaneous responses are physiological changes in the absence of detectable stimuli. These changes are important to researchers because they can confound the measurement of phasic activity. For example, suppose a spontaneous increase in skin conductance occurs as a subject is shown an emotionally-charged slide. In that case, a researcher could mistakenly conclude that the slide increased conductance more than it did (Stern, Ray, & Quigley, 2001).

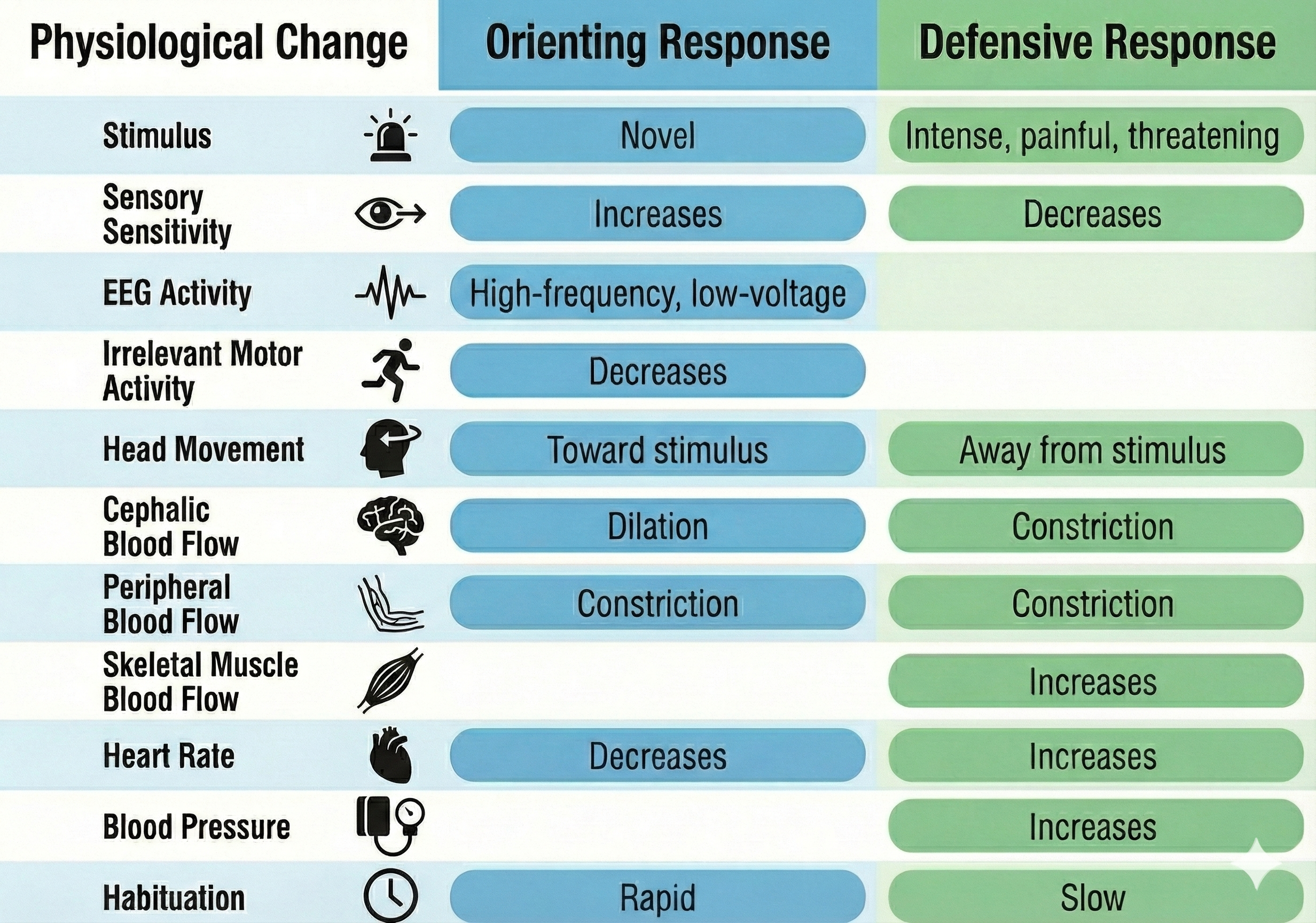

Orienting and Defensive Responses: How We React to Our Environment

When exposed to a novel stimulus, an orienting response prepares us to deal with this challenge. Pavlov's (1927) orienting response is a "What is it?" reaction to stimuli like the sound of a vase crashing.

The orienting response includes increased sensory sensitivity, head (and ear) turning toward the stimulus, increased muscle tone (reduced movement), EEG desynchrony, peripheral constriction and cephalic vasodilation, a rise in skin conductance, heart rate slowing, and slower, deeper breathing. An orienting response rapidly habituates since it is no longer needed once we respond to a novel stimulus.

In contrast, a defensive response is a slowly habituating response pattern that limits harm from intense stimulation. This pattern includes reduced sensory sensitivity, a tendency to move away from the stimulus, heart rate increase, and both peripheral and cephalic vasoconstriction. For example, a loud noise in a workplace environment might elicit a defensive response.

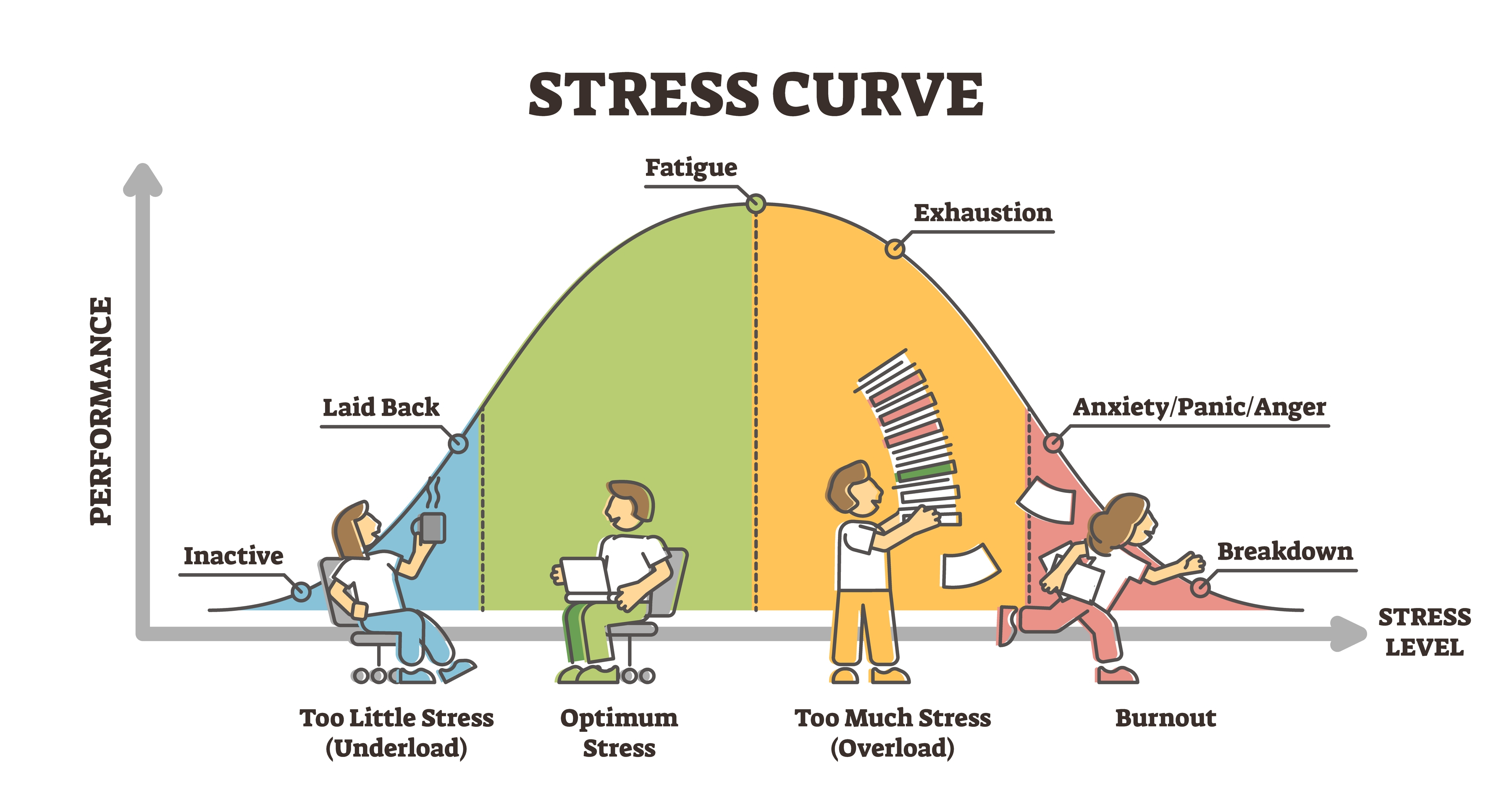

Activation Theory: Understanding What Makes Behavior Intense

Duffy's activation theory starts from a simple question: what makes behavior intense? Instead of focusing on how strong an outward response looks (for example, how loudly someone yells), Elizabeth Duffy argued that psychologists should look at internal arousal processes, what she called activation (Duffy, 1957; Ehrlich, 1963; Pitz, 1964). She proposed that behavior varies along two basic dimensions: direction (what you do) and intensity (how strongly you do it), and that intensity is best understood as the degree to which the organism's stored energy is being released through metabolic and neural activity (Duffy, 1957; Ehrlich, 1963; Pitz, 1964). On this view, activation reflects the level of neural activity in central systems like the reticular activating system, influenced by external stimulation (noise, tasks), internal bodily states (heart rate), and thoughts, and is usually inferred from physiological measures such as brain waves or skin conductance rather than from behavior alone (Gardner, 1986).

Activation and Performance: The Inverted-U

Research since Duffy's time has both extended and complicated this picture. Some work kept close to her single "activation" dimension, using it to explain how task design affects people's arousal, satisfaction, and performance at work. For example, Gardner (1986) tested activation theory in a lab setting and found that very boring, low-stimulation tasks could actually raise arousal and lower satisfaction more than moderately stimulating tasks, and that performance tended to follow an inverted-U curve, with both too little and too much activation hurting performance. From a biofeedback perspective, we want our clients to achieve optimal (not maximal) activation for any task. Think about a student taking an exam: too little activation means drowsiness and poor focus, while too much activation means anxiety that interferes with memory retrieval.

Multiple Dimensions of Activation

Other theorists split activation into multiple dimensions. Thayer (1978) proposed at least two types: energetic arousal (awake versus tired) and tense arousal (tense versus calm), and later work confirmed that these are not just mixtures of pleasantness and a single activation scale but genuinely distinct forms of activation (Schimmack & Reisenzein, 2002). Studies on attention similarly distinguish arousal (momentary reactions to input) from activation (ongoing readiness to respond), each tied to different brain circuits and functions (Pribram & McGuinness, 1975; VaezMousavi et al., 2007).

Current Status of Activation Theory

Because of these developments, Duffy's exact version of activation theory is no longer a major stand-alone theory, but its core ideas remain embedded in modern research. The general insight that internal activation underlies the intensity of behavior influenced later multidimensional models of arousal and activation and current work on the "energetics" of attention and performance (Pribram & McGuinness, 1975; Thayer, 1978; VaezMousavi et al., 2007). At the same time, the field has moved away from a single activation continuum toward more fine-grained systems: separate neural circuits for arousal, activation, and effort; different subjective forms of activation; and clear distinctions between baseline arousal and task-related activation (Pribram & McGuinness, 1975; Schimmack & Reisenzein, 2002; VaezMousavi et al., 2007). Empirically, this means Duffy's broad concept has been partly confirmed (internal arousal really does matter for intensity) but also revised and split into multiple components. Today, activation theory is best seen as a historically important starting point whose core themes survive inside more detailed neuropsychological and motivational models rather than as a current, unified theory being directly tested.

Problems with Activation Theory

Lacey (1967) and other researchers raised serious objections to activation theory, and their critiques reshaped how scientists think about physiological arousal. The core problem is that arousal is not a single dimension. Lacey argued that autonomic, behavioral, and cortical arousal are distinct phenomena that do not always move together, so measuring only one index can be misleading.

For instance, when heterosexual men view slides of nude women, heart rate may increase while finger blood flow remains unchanged (Stern, Ray, & Davis, 1980). If researchers relied solely on finger blood flow, they might wrongly conclude the men were not aroused at all. Adding to this complexity, individuals show unique response patterns called response stereotypy, meaning the same person tends to react in consistent ways to stimuli of similar intensity and emotional tone.

One patient might always respond to pressure with elevated heart rate and blood pressure, whether she is delivering a report at work or racing to meet a deadline. Because clients bring different vulnerabilities and learning histories into treatment, clinicians conduct a psychophysiological profile to map out each person's characteristic response pattern.

Beyond individual differences, activation theory stumbles on the finding that specific stimuli and emotions produce their own distinctive physiological signatures rather than simply turning a generic arousal dial up or down. This principle of stimulus-response specificity shows up when, for example, people reliably increase muscle tension during competitive challenges.

Similarly, emotional response specificity means that primary emotions like anger, fear, and happiness each come with unique physiological fingerprints. Research by Ekman and colleagues found that anger raises both heart rate and skin temperature, fear raises heart rate while lowering skin temperature, and happiness raises heart rate without affecting skin temperature. Schwartz, Weinberger, and Singer (1981) extended these findings, showing that cardiovascular patterns can distinguish anger from fear and separate both from happiness and sadness.

Finally, Lacey observed that responses are often complex, with some physiological indices increasing while others decrease at the same moment. He called this intricate pattern directional fractionation. When a police officer hears a sudden noise, for instance, EEG and skin conductance may spike while digestive activity simultaneously drops. Together, these critiques show that the body's stress responses are far more nuanced than a simple arousal thermometer would suggest.

Habituation

Habituation is the opposite of arousal. A person gradually ceases to respond or reduces their response to a constant stimulus. For example, after 15 trials of listening to a moderate intensity tone, heart rate might no longer increase. Predictable, low-intensity stimuli that convey no new information and require no response readily produce habituation. Habituation is inhibited when a stimulus is intense, complex, and unique, and the subject must respond to it (rate its unpleasantness).

The orienting response and defensive response differ in their speed of habituation. Orienting responses rapidly habituate, while defensive responses habituate very slowly.

Situational Specificity: Context Matters

Situational specificity means that a physiological response (blood pressure elevation) does not occur randomly and is most likely in situations with special characteristics.

A situation's properties may include the location (office), time of day (morning), activity (conference), individuals present (employer), and personal emotional state (anxiety). A client's hypertensive response may be classically or operantly conditioned, which means they may be unaware of learning this response since its symptoms are largely "silent," and both processes involve implicit learning. Due to associative learning, the presence of one or more situational cues may elicit a complete physiological response.

Clinicians investigate the situational specificity of presenting complaints when they conduct a history, perform a psychophysiological profile (PSP), ask the client to maintain a symptom journal, and monitor the client in multiple real-world settings (blood pressure measurement in the office and while stalled in traffic). Situational information is crucial in creating stimulus hierarchies when using systematic desensitization to treat a phobia.

Law of Initial Values: Why Starting Points Matter

Imagine giving the same cup of coffee to two people: one who just woke up groggy and one who is already buzzing with energy. Would you expect the same reaction? Joseph Wilder suspected not, and his law of initial values (LIV) attempts to capture this intuition in a formal principle. According to Wilder, when you administer the same stimulus to different people and measure their responses over the same time window, those who start at higher baseline levels tend to show smaller changes in the direction the stimulus would normally push them, and larger changes in the opposite direction, compared to those who start lower (Wilder, 1962, 1967/2014).

Consider a practical example. For function-raising stimuli (such as a drug designed to elevate blood pressure), the LIV predicts that individuals whose blood pressure is already high will show smaller increases, and paradoxically, more frequent drops. For function-depressing stimuli, the pattern flips to its mirror image. Wilder argued that this behavior reflects the basic self-regulatory machinery of the autonomic nervous system and claimed that it appears across many physiological systems. He pointed especially to cardiovascular measures like blood pressure and heart rate, as well as endocrine and pharmacologic responses to standard drug doses (Wilder, 1962, 1967/2014).

Early Evidence for the Law of Initial Values

Early psychophysiology research lent credibility to Wilder's claims. Investigators found LIV-like patterns for heart rate and respiration, including a striking phenomenon known as the crossover point, where responses flip from increases to paradoxical decreases once baselines climb high enough (Block & Bridger, 1962; Hord et al., 1964). These findings suggested that the body actively resists being pushed too far in any one direction.

Statistical Traps That Can Mimic Biology

Today, researchers view the LIV as conditional rather than a universal biological law. More recent analyses have revealed an uncomfortable truth: the familiar negative correlation between baseline and change can be partly a statistical illusion. Two culprits are mathematical coupling (when baseline values are embedded in the calculation of change scores) and regression to the mean (the tendency for extreme scores to drift toward average on retest). When investigators strip away these artifacts, some datasets actually show an anti-LIV pattern, where higher initial values are followed by larger, not smaller, responses (Geenen & van de Vijver, 1993; Jin, 1992; Myrtek & Foerster, 1986).

Where the LIV Holds and Where It Fails

Empirically, LIV-type effects receive their most consistent support for certain autonomic nervous system variables, especially heart rate and respiration rate measured under acute, standardized laboratory stressors. In these contexts, crossover points and paradoxical responses at high baselines do appear reliably (Block & Bridger, 1962; Hord et al., 1964). Other autonomic outputs tell a different story. Skin temperature, for instance, may show little evidence of the LIV. Skin conductance (a sweat-gland measure) can even display anti-LIV behavior, with higher baselines predicting larger responses (Hord et al., 1964). Stern, Ray, and Quigley (2001) similarly reported that studies support the LIV for heart rate and skin resistance but not for skin conductance.

Berntson and colleagues (1994) questioned the LIV's value and encouraged researchers to develop an "autonomic constraints" model tied to underpinning physiology.

Relevance of the LIV for Biofeedback Practice

The current status of the LIV is mixed. It captures a real, sometimes powerful baseline dependency in specific systems under specific conditions, but its reach is limited. Researchers studying phasic (rapidly changing) measures may consider employing statistical methods to control the influence of prestimulus values on the size of physiological responses. Careful statistical methods are essential before treating it as a general law of biological reactivity (Geenen & van de Vijver, 1993; Jin, 1992; Myrtek & Foerster, 1986; Wilder, 1962, 1967/2014).

Remember that the LIV is a principle, not a law, and does not apply to all subjects and response systems. Researchers can determine whether the LIV is relevant by computing the correlation between prestimulus and poststimulus values. Geenen and van de Vijver (1993) suggested that the LIV may be less common than perceived and correction methods may harm the data more than the phenomenon itself.

Generalization of Biofeedback Training: Will Skills Transfer?

The key muscle hypothesis and hand-warming specificity have important implications for biofeedback training.

The Key Muscle Hypothesis: A Tempting but Flawed Idea

The key muscle hypothesis in biofeedback grew from the idea that certain skeletal muscles, especially the frontalis in the forehead, serve as a "master dial" for bodily tension. The logic was appealing: if forehead EMG drops, overall musculature is presumed to relax, and the person should feel globally calmer. Early EMG biofeedback studies on tension headache trained patients to reduce frontalis EMG via auditory or visual feedback and reported large reductions in headache activity, bolstering the intuition that relaxing one "key" muscle could unlock whole-body relaxation and symptom relief (Budzynski et al., 1973).

What EMG Biofeedback Actually Does Well

Biofeedback reliably reduces EMG in the specifically trained muscle and can increase people's ability to detect and modulate their own tension, suggesting genuine learning at the local muscular level (Sime & DeGood, 1977). More recent clinical and rehabilitation trials similarly show that EMG-based biofeedback can be effective when targeted to particular muscles. For example, researchers have successfully applied EMG biofeedback to masticatory muscles in temporomandibular disorders, pelvic floor muscles postpartum, and postural muscles in chronic low back pain and other musculoskeletal conditions (de la Barra Ortiz et al., 2022; Florjanski et al., 2019; Giggins et al., 2013; Handzlik-Waszkiewicz et al., 2025; Lazaridou et al., 2023). These findings support the value of site-specific muscle relaxation rather than a single global key.

The Evidence Against Generalization

When the core predictions of the key muscle hypothesis have been tested directly, however, the evidence has been largely negative. In a classic study, training frontalis EMG relaxation did not generalize to untrained forearm or lower-leg muscles, and reduced forehead EMG did not produce greater subjective relaxation than instructions without feedback (Alexander, 1975). A follow-up experiment similarly found that both feedback and non-feedback groups could lower EMG and that prior training on one muscle failed to facilitate training on another, undermining the idea of a privileged key muscle or a generalized relaxation skill emerging from it (Alexander et al., 1977).

Other work comparing EMG biofeedback, relaxation instructions, and adaptation effects showed that decreases in muscle activity were largely attributable to instructions to relax, not to the feedback signal itself. Again, no special generalization or superiority of key-muscle feedback was observed (Davis, 1980). The musculoskeletal system functions very specifically: we simultaneously contract and relax adjacent agonist-antagonist muscle pairs at a joint, which explains why training one site does not automatically transfer to others.

Current Status of the Key Muscle Hypothesis

Contemporary systematic reviews characterize EMG biofeedback as an effective adjunct for reducing activity and pain in specific muscles and improving function, but they do not support the notion that training a single "key" muscle reliably produces whole-body relaxation (de la Barra Ortiz et al., 2022; Florjanski et al., 2019; Giggins et al., 2013). In current science and practice, the key muscle hypothesis is therefore viewed as largely unsupported in its strong, generalized form, while localized EMG-guided relaxation remains a valuable, evidence-based tool.

Hand-Warming Specificity: Does Thermal Training Transfer?

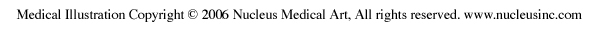

Situational specificity in thermal biofeedback is about how far a learned warming response "spreads." If someone learns to warm one finger using biofeedback, does that skill automatically generalize to the whole hand, other fingers, or even the feet? Early clinical enthusiasm often assumed "yes," treating hand-warming as a kind of global circulatory relaxation skill that would show up all over the body. More recent work paints a more cautious and nuanced picture: some spread across nearby sites is possible, but easy one-to-one transfer, especially from hand to feet, cannot be taken for granted.

The cardiovascular system can function very precisely, just like the musculoskeletal system. Temperature training can produce extremely site-specific changes. The picture below shows the placement of a thermistor (temperature sensor) on the index finger's dorsal surface.

Within-Hand Transfer: Local Control with Some Spillover

Within the hand, biofeedback studies show both local control and some local spillover. People can learn to raise or lower temperature in a targeted finger by a small but reliable amount, and training effects typically emerge within a few sessions (Keefe & Gardner, 1979; King & Montgomery, 1980). In diabetic patients, training on one hand increased temperature not only in the trained hand but also in the untrained hand, suggesting that part of the effect reflects more global autonomic changes or generalized relaxation rather than a perfectly isolated local response (Dean, 1984). More broadly, hand-temperature increase training tends to generalize to other physiological "relaxation" markers (like reduced muscle tension and lower arousal), indicating cross-system transfer of a general relaxation pattern rather than purely local vascular skill (Clemow, 1985).

The temperature map below shows mean undergraduate finger and web dorsum temperatures (Lammy et al., 2004).

Hand-to-Foot Transfer: A Different Story

When researchers explicitly tested generalization from hand to foot, however, the story changes. In a Raynaud's syndrome case study, a patient learned a large and rapid hand-warming response, but foot temperature increases were modest and much slower to acquire; hand and foot temperature fluctuations were not significantly related across or within sessions, leading the authors to conclude that "an easy generalization of the hand-warming response cannot be assumed" (Crockett & Bilsker, 1984, p. 328).

Physiological studies of cold responses support this dissociation. Cold-induced vasodilation is highly variable across fingers and does not generalize reliably from fingers to toes or from hand to foot within the same person (Cheung & Mekjavic, 2007; Norrbrand et al., 2017). In other words, thermal control in one extremity tells you surprisingly little about another.

At the same time, targeted thermal biofeedback and relaxation focused directly on the feet can increase toe temperature and blood flow in people with diabetes, but that improvement comes from training the feet themselves, not from transfer of hand training (Rice & Schindler, 1992).

Clinical Implications for Temperature Training

Overall, current thinking is that hand-warming biofeedback can shape nearby or related systems but cannot be assumed to generalize automatically from one finger to the whole hand or from the hands to the feet; those regions likely need their own specific training. Clinicians should never expect hand-warming to generalize beyond the actual site trained. Depending on training procedure and individual differences, hand-warming might generalize to other digits on the same hand or to the other hand for some clients but not for others.

Key Takeaways: Psychophysiological Concepts

Homeostasis maintains your internal balance through feedback systems, while allostasis allows adaptation through anticipation. The law of initial values reminds us that starting points affect how much change is possible. The key muscle hypothesis, while intuitively appealing, has not been supported in its strong form: training one muscle does not reliably generalize to whole-body relaxation. However, site-specific EMG biofeedback remains a valuable clinical tool. Similarly, hand-warming at one site may not transfer to other sites. These specificity findings mean that your biofeedback training must target the actual physiological systems and specific muscle groups relevant to your client's presenting complaints.

Comprehension Questions: Measurements and Principles

- Why is it important to understand the difference between tonic and phasic activity when interpreting biofeedback data?

- How would the Law of Initial Values affect your expectations for a client whose resting heart rate is already very low?

- Your client asks, "If I can relax my forehead muscles, won't that relax my whole body?" How would you respond based on the key muscle hypothesis research?

- Explain how situational specificity might help you design a more effective treatment plan for a client with white-coat hypertension.

The Placebo Effect: The Power of Expectation

The placebo effect is no longer seen as "just in your head," but as a genuine set of mind-body responses to the whole treatment context: the rituals of medicine, the white coat, what the clinician says, and what the patient expects will happen (Finniss et al., 2010; Petrie & Rief, 2019; Price et al., 2008). When people receive an inert pill or sham procedure, their brains and bodies can change in measurable ways: pain decreases, Parkinson's symptoms improve, or mood lifts, especially when symptoms are subjective, like pain or nausea (Ashar et al., 2017; Ozpolat et al., 2025; Wager & Atlas, 2015).

Neuroscience links these effects to systems that use dopamine and endogenous opioids, which are the same chemicals involved in reward and natural pain control (Dodd et al., 2017; Knezevic et al., 2025; Wager & Atlas, 2015). Two core psychological mechanisms keep appearing across studies: expectation ("this will help me") and learning/conditioning (the body learns to respond to the look and feel of treatment the way it has responded to real drugs in the past) (Petrie & Rief, 2019; Price et al., 2008).

Ordinary (Deceptive) Placebos