Stress

What You Will Learn in This Unit

Here is a sobering statistic: researchers have calculated that high-stress mothers' cells aged 9 to 17 years faster than those of low-stress mothers. Stress is not just an unpleasant feeling; it physically reshapes your body down to the cellular level. But here is the encouraging news: understanding how stress works gives you and your clients powerful tools to fight back.

In this unit, you will discover why the word "stress" causes so much confusion (it can mean a stimulus, a response, or a transaction) and why each person's stress fingerprint is unique. You will learn why Selye's idea of stress as a "nonspecific response" misses crucial details about how your body actually responds, and how modern models like the allostatic load framework have replaced older thinking.

Along the way, you will explore how stressors range from cataclysmic events like pandemics to daily hassles like traffic jams, and why what happens in your gut can affect what happens in your brain. You will understand the brain structures that orchestrate your stress response and discover why some people bounce back from adversity while others struggle. Most importantly, you will learn about the resources that buffer stress, from social support to aerobic exercise.

This unit covers Stressors and Stress, The Stress Response is Multidimensional, the Biopsychosocial Model, the Allostatic Load Model, the Stress-Diathesis Model, System-Wide Effects of Stress, Stressful Life Events, Psychological Factors in Stress, Acute and Chronic Stress Responses, Psychoneuroimmunology, Cognitive Appraisal of Stressors and Coping, Personality Dimensions, and Resources to Buffer Stress.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage: This unit addresses Models of stress and illness (II-A), Psychophysiological reactions to stressful events (I-B), and Psychosocial mediators of stress (I-C).

Let us be honest: the word stress can be confusing because it refers to a stimulus, a response, or a transaction between a person and their environment. The stress response is multidimensional, meaning multiple systems respond in complex ways. Additionally, individuals often show characteristic response patterns. The old idea that the stress response is "nonspecific" is misleading because clients may have unique stress triggers (like time pressure) and specific psychophysiological changes (like blood pressure spikes).

While early theories of stress emphasized the role of stimuli, more recent theories focus on our cognitive appraisal of events and our coping resources. The biopsychosocial model has replaced the aging biomedical model due to its greater comprehensiveness and support for interdisciplinary treatment of disorders. Likewise, the allostatic load model has replaced Selye's General Adaptation Syndrome framework for understanding the role of stress in disease.

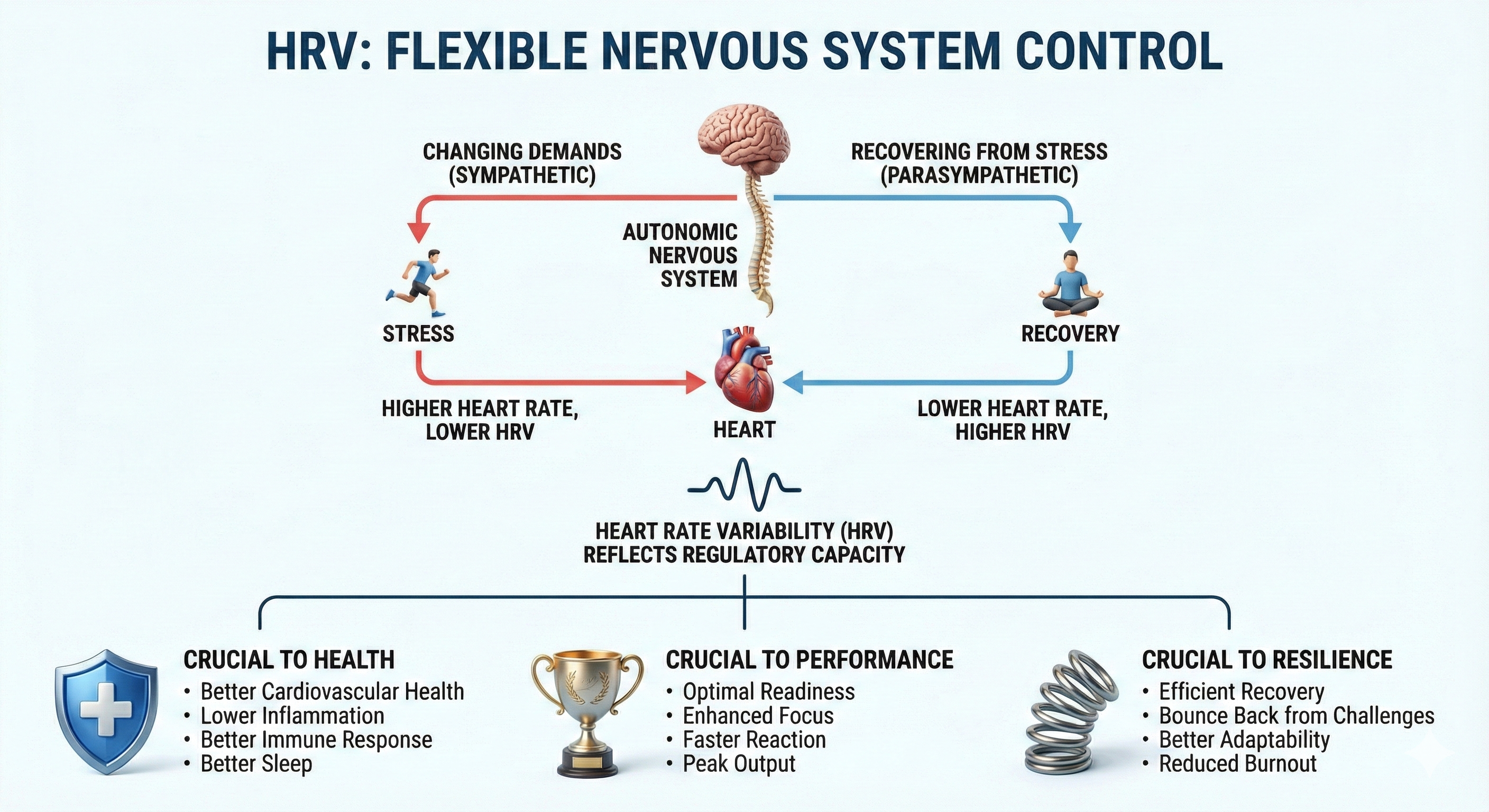

Chronic stress reduces heart rate variability (HRV), which is the organized fluctuation of time intervals (measured in milliseconds) between successive heartbeats. HRV is crucial to health, performance, and resilience because it reflects the nervous system’s ability to flexibly control the heart in real time—adapting to changing demands and recovering from stress efficiently.

Low HRV is a marker for cardiovascular disorders, including hypertension (especially with left ventricular hypertrophy), ventricular arrhythmia, chronic heart failure, and ischemic heart disease (Bigger et al., 1995; Casolo et al., 1989; Maver et al., 2004; Nolan et al., 1992; Roach et al., 2004). Low HRV predicts sudden cardiac death, particularly due to arrhythmia following myocardial infarction and post-heart attack survival (Bigger et al., 1993; Bigger et al., 1992; Kleiger et al., 1987).

Reduced HRV may predict disease and mortality because it indexes reduced regulatory capacity, which is the ability to surmount challenges like exercise and stressors. Patient age may be an essential link between reduced HRV and regulatory capacity since HRV and nervous system function decline with age (Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014).

A 2023 scoping review confirmed that HRV serves as a valid biomarker for psychological stress, with the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) emerging as the most frequently reported metric significantly associated with stress across both experimental and real-life conditions (Immanuel, Teferra, Baumert, & Bidargaddi, 2023). The reviewers found consistent evidence that stress decreases parasympathetic activity.

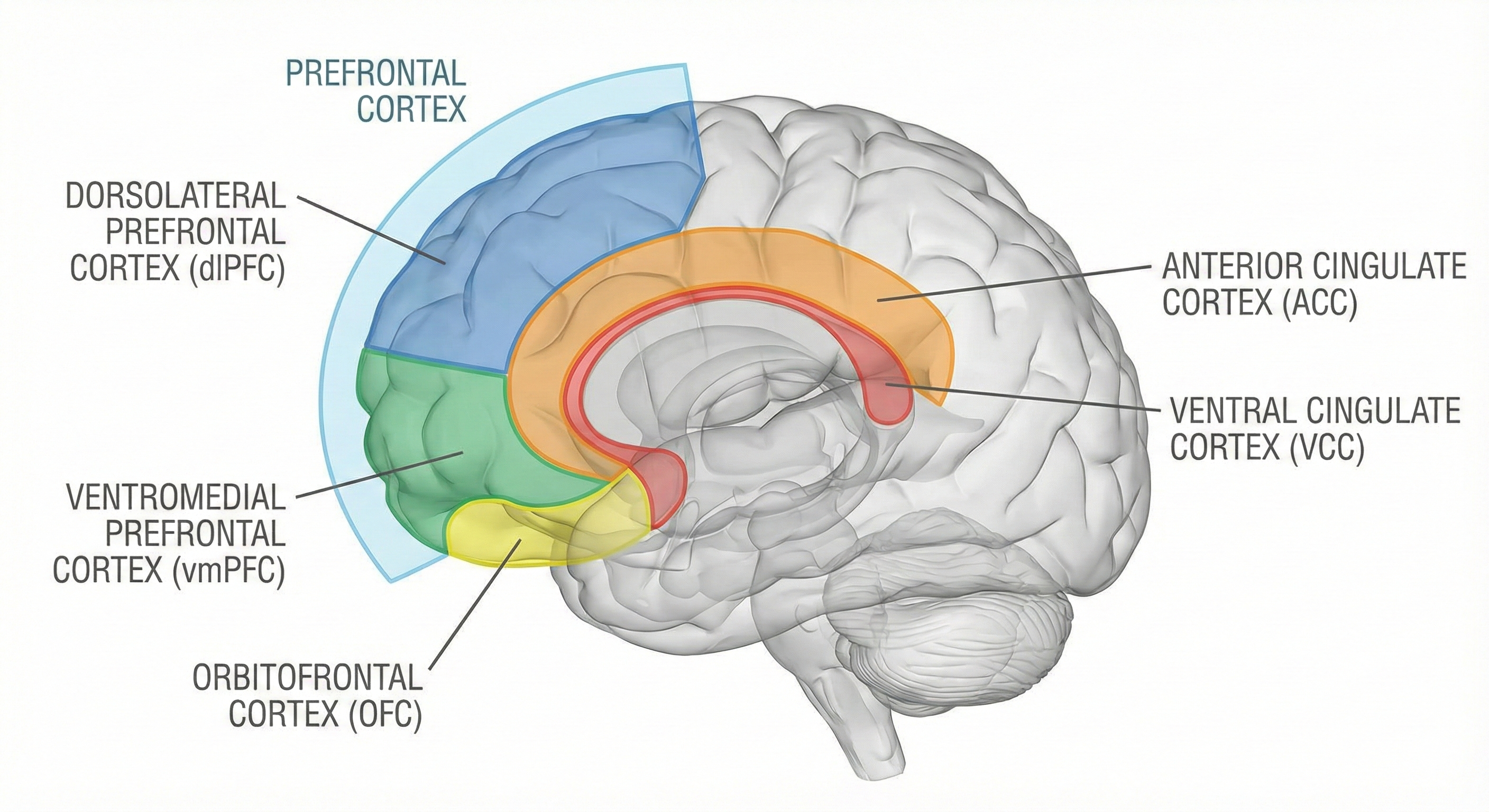

Neuroimaging research has further strengthened the connection between HRV and stress by demonstrating that HRV correlates with activity in brain regions involved in emotional regulation, particularly the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Kim, Cheon, Bai, Lee, & Koo, 2018).

Even more encouraging, a 2024 meta-analysis found that stress-reducing interventions such as relaxation training and mindfulness increased HRV in cardiovascular disease patients (El-Malahi et al., 2024). These findings suggest that HRV can serve both as an objective marker for assessing stress and as a target for therapeutic intervention.

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter LectureHow We Define and Measure Stressors

Cannon (1939) studied how environmental stressors like cold temperatures and loss of oxygen trigger a fight-or-flight response. He conceptualized stress as the disruption of homeostasis when the body mobilizes the sympathetic and endocrine systems to deal with external threats.

Selye (1956) also studied environmental challenges to homeostasis. He referred to stress (and strain) as emotional and physiological responses to stimuli called stressors.

🎧 Listen to a mini-lecture on Stressors and StressSelye's Nonspecific Response Theory and Its Limitations

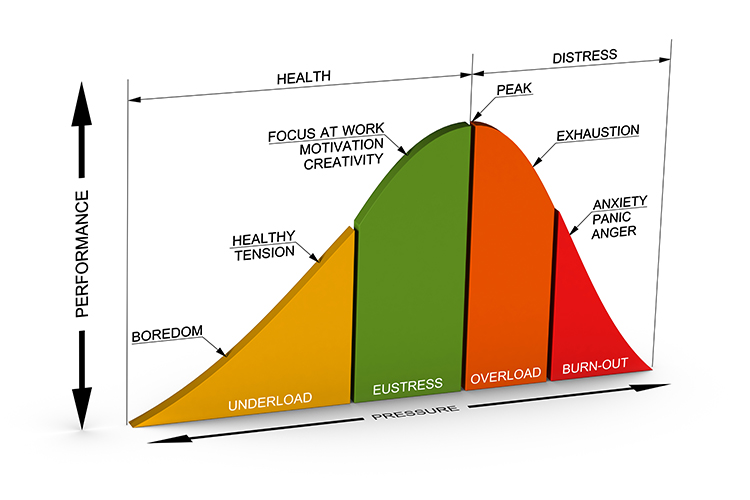

Selye conceptualized stress responses as nonspecific since many stimuli can produce the same physiological changes. He theorized that both negative and positive stimuli could provoke stress responses requiring coping resources. He termed stress due to aversive stimuli distress and stress due to positive events eustress (Moksnes & Espnes, 2016).

The Yerkes-Dodson curve graphs the relationship between stressors and performance. Think of it like a hill: the left side of the inverted U-curve depicts an underload where an individual is insufficiently challenged and bored. This phenomenon of low motivation and performance has been termed rust out and reminds us that we require stressors for motivation and creativity (O'Dowd, 1987). The middle region that ends with peak performance corresponds to eustress; an optimal level of challenge promotes focus, motivation, and creativity. The right side of the curve represents the worsening effects of excessive pressure, overload, and burnout with anxiety, panic, and anger.

Why Selye's Model Needed Updating

Selye's model excluded psychological factors like appraisal. His assumption that stress involves nonspecific physiological changes is incorrect. All stressors do not produce a uniform endocrine stress response. Instead, stressors can change multiple body systems in response to stressor intensity, biological predisposition, cognitive appraisal, perceived support, and emotional response (Mason, 1971, 1975; McEwen, 2005; Taylor, 2021). Finally, whereas Selye proposed that our stress responses attempt to maintain physiological processes within a narrow optimal range, current research focuses on adaptation (such as the allostatic load model) instead of set points (Brannon et al., 2022).

The term "stress" can refer to stimuli, responses, or transactions. Selye's concept of nonspecific stress responses has been replaced by models recognizing individual differences in how people respond to stressors. Modern approaches emphasize cognitive appraisal, biological predisposition, and adaptation rather than fixed set points.

Check Your Understanding

- Why is Selye's characterization of stress as "nonspecific" now considered misleading?

- What is the difference between distress and eustress?

- How does the Yerkes-Dodson curve explain the relationship between stress and performance?

The Stress Response Is Multidimensional

The human stress response is multidimensional and involves diverse systems, from the central nervous system to the immune system. Each person uniquely responds to stressors. This individualized pattern is called response stereotypy. Individuals differ in the systems impacted, their activation or suppression, and how these changes affect health. While stressors can produce system-wide macroscopic changes like increased blood pressure, they can also cause epigenetic changes that alter DNA expression.

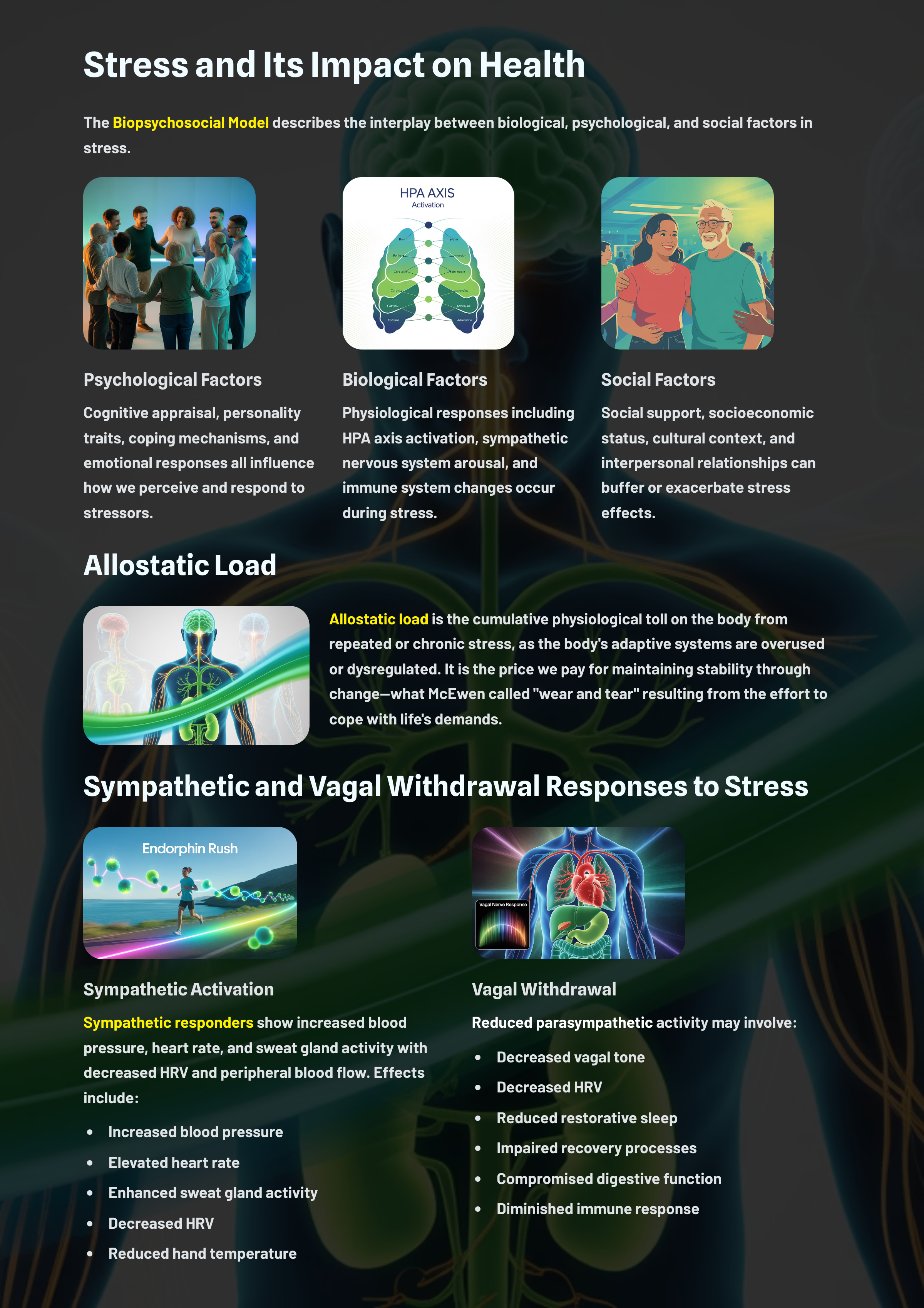

Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Responders Show Different Patterns

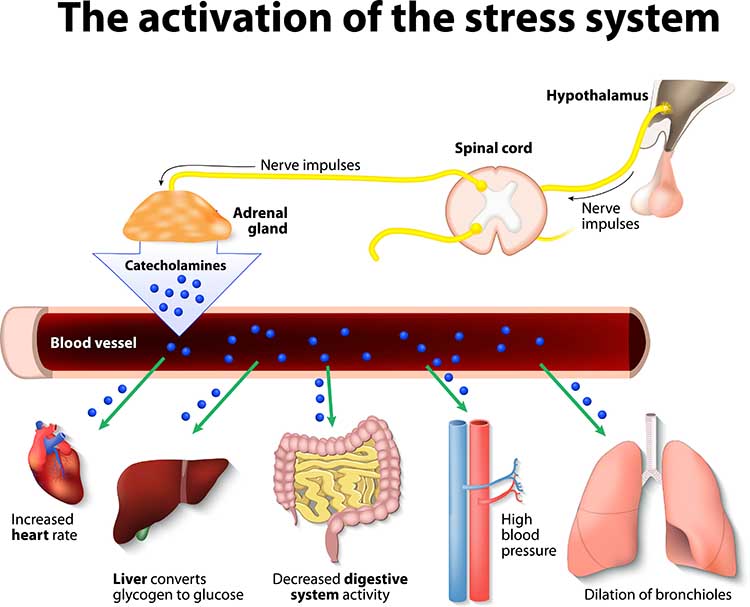

Two modal patterns of autonomic response to stressors have been observed. A sympathetic responder may increase blood pressure, heart rate, and sweat gland activity and decrease heart rate variability and peripheral blood flow. These changes may result from increased sympathetic activation, decreased parasympathetic activation called parasympathetic withdrawal, or a combination of both.

🎧 Listen to a mini-lecture on Sympathetic and Parasympathetic RespondersIn contrast, a parasympathetic responder may increase digestive activity, constrict the lungs' alveoli, and faint from low blood pressure.

Individuals can react to stressors with elements of both autonomic patterns. For example, consider a client named Marcus who comes to you for stress management. During his assessment, you notice that he increases his heart rate and blood pressure (sympathetic) while simultaneously experiencing gastrointestinal symptoms of diarrhea and gas (parasympathetic). Understanding his unique pattern is essential for effective treatment.

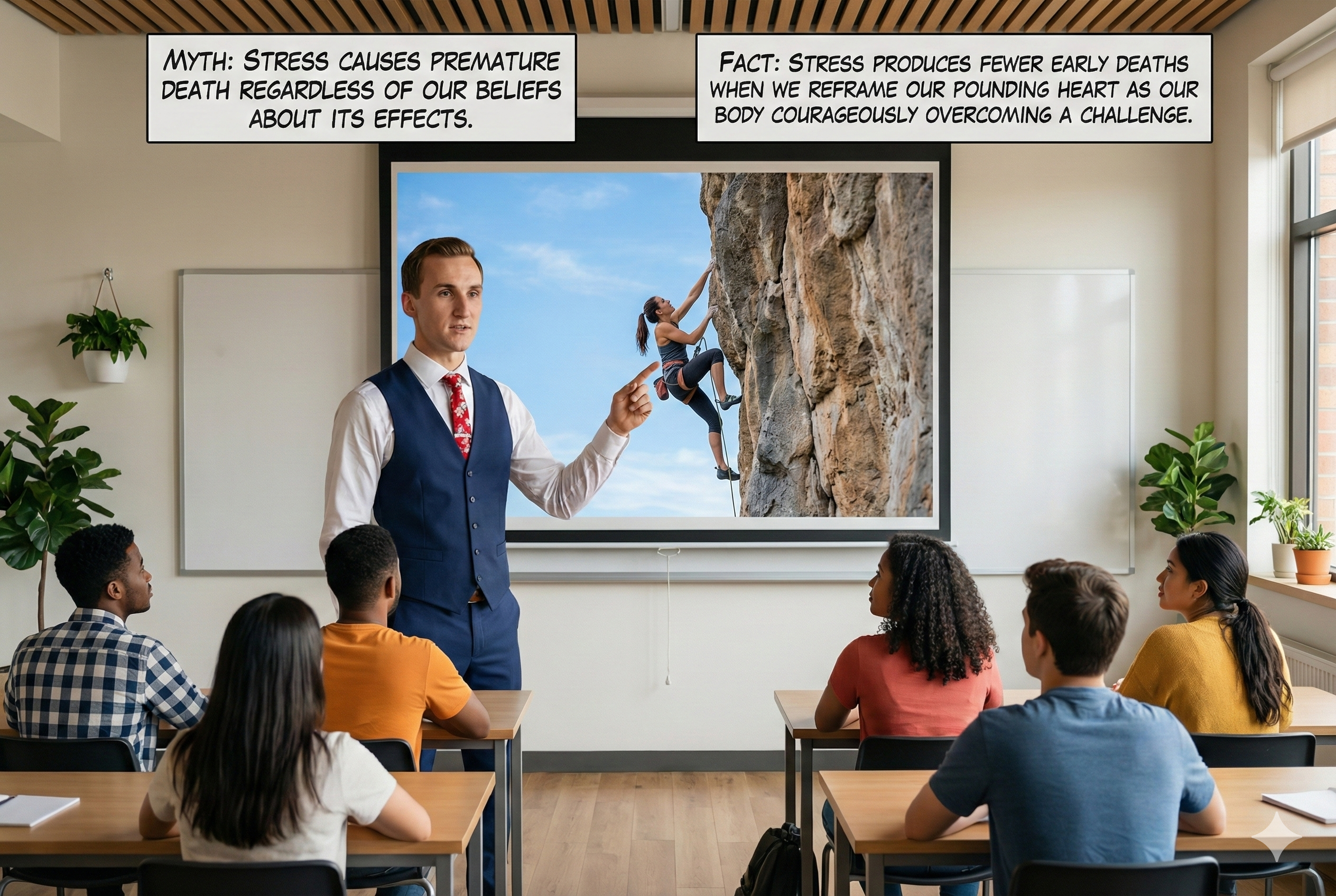

The Biopsychosocial Model Has Replaced the Biomedical Model

Engel (1977) proposed the biopsychosocial model to replace the biomedical model. While the biomedical model holds that abnormal biological processes cause illness, the biopsychosocial model argues that biological, psychological, and social factors all contribute to the development of disease and maintenance of health.

Think of it this way: the biomedical model treats the body like a car that breaks down due to mechanical problems. The biopsychosocial model recognizes that humans are far more complex; how you think, how you feel, and the social world you live in all shape your health.

The Allostatic Load Model Explains Wear and Tear

McEwen and Stellar (1993) introduced the allostatic load model to capture the price our bodies pay for adapting to stressors. Allostasis refers to maintaining stability through change by mechanisms that anticipate challenges and adapt through behavior and physiological change.

Allostatic load is the wear and tear on the body from chronic overactivity or underactivity of allostatic systems. Imagine your stress response as a fire alarm: helpful when there is a real fire, but damaging if it keeps going off for no reason. Over time, this constant activation exhausts your body's resources and damages organs.

A 2021 systematic review by Guidi and colleagues confirmed the clinical utility of the allostatic load concept, demonstrating consistent associations between elevated allostatic load scores and adverse health outcomes across diverse populations.

A 2025 systematic review examining the relationship between allostatic load and cardiovascular disease analyzed 22 studies and found that allostatic load was significantly associated with incident cardiovascular disease at baseline, though fewer significant relationships emerged for longitudinal changes (Colvin & Glover, 2025). The researchers noted that allostatic load may serve as a useful indicator of cardiovascular disease risk but may not as accurately predict cardiovascular outcomes such as mortality. This distinction has important implications for clinicians using allostatic load as a clinical marker.

Newer research has extended the allostatic load framework to cancer outcomes. Stabellini and colleagues (2025) examined allostatic load in patients diagnosed with breast, lung, or colorectal cancer and found that higher allostatic load scores were associated with increased risk of major cardiac events following cancer diagnosis.

A one-point increase in allostatic load was linked to up to a 21% increased risk of major adverse cardiac events, with heart failure showing the highest associated risk at 23%. The association was particularly strong during the 6 to 12 months following cancer diagnosis, a period marked by intense psychological and physiological stress from both the diagnosis and treatment.

These findings highlight the importance of addressing chronic stress during cancer care to reduce cardiovascular complications.

The Stress-Diathesis Model Explains Individual Vulnerability

The stress-diathesis model proposes that stressors interact with our inherited or acquired biological vulnerabilities, called diatheses, producing medical and psychological symptoms. For example, obesity is a diathesis for diabetes; when combined with chronic stress, the risk of developing diabetes increases significantly.

The stress response involves multiple body systems and varies uniquely from person to person (response stereotypy). Some individuals are sympathetic responders while others are parasympathetic responders. The biopsychosocial model recognizes that biological, psychological, and social factors all contribute to health and disease. The allostatic load model explains how chronic stress causes cumulative wear and tear on the body.

Check Your Understanding

- What is response stereotypy, and why is it important for biofeedback practitioners to understand?

- How do sympathetic and parasympathetic responders differ in their stress reactions?

- What is allostatic load, and how does it contribute to disease?

- How does the biopsychosocial model differ from the biomedical model?

System-Wide Effects of Stress

The Microbiome and Stress

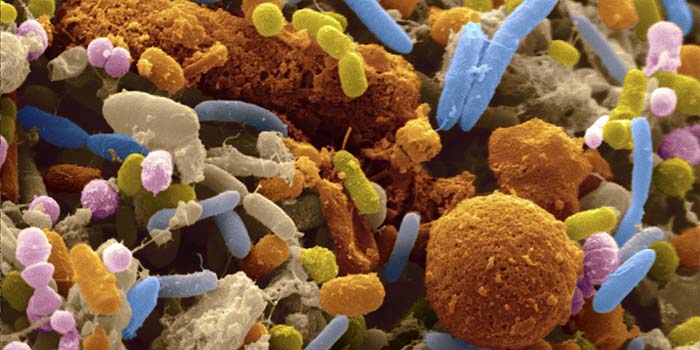

Your gut contains trillions of microorganisms collectively called the microbiome. These beneficial bacteria play a role in digestion, synthesize neurotransmitters and vitamins, modulate immunity, and influence nervous system function. The microbiome's role in health and disease is the subject of extensive current research.

The Microbiome Modulates Neurotransmitters

The gut microbiota communicates with the brain through the microbiota-gut-brain axis, influencing neurotransmitter production, transportation, and function, which in turn affects cognitive functions and brain activity (Chen, Xu, & Chen, 2021; Lynch & Hsiao, 2023).

Key neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are modulated by gut bacteria, which can produce or alter these neuroactive compounds, impacting host physiology and potentially contributing to conditions like Parkinson's disease, anxiety, and depression (Foster & Neufeld, 2013; Hamamah et al., 2022; Strandwitz, 2022).

The microbiome's ability to produce neurotransmitters and interact with host receptors underscores its potential as a therapeutic target, with emerging research focusing on psychobiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics that influence mental health (LaGreca, Skehan, & Hutchinson, 2022). Additionally, microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids and bile acids play a role in signaling pathways that affect brain function and behavior (Caspani & Swann, 2019; Foster, 2022).

The Gut-Brain Axis and Disease

The gut-brain axis refers to the bidirectional communication network linking the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system, encompassing neural, hormonal, and immunological pathways. The gut microbiota significantly influences this axis by producing neurotransmitters (such as serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid) and metabolites like short-chain fatty acids, which can affect brain function and behavior.

Alterations in gut microbiota composition, known as dysbiosis, have been associated with various neurological and psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, and autism spectrum disorders. For instance, studies have demonstrated that germ-free mice exhibit altered stress responses and anxiety-like behaviors, which can be mitigated by introducing specific microbial species, highlighting the microbiota's role in modulating the gut-brain axis (Schächtle & Rosshart, 2021).

Furthermore, systemic inflammation resulting from gut dysbiosis may compromise the integrity of the blood-brain barrier, facilitating the entry of neurotoxic substances and contributing to neuroinflammation. This mechanism has been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease.

How Stress Affects the Microbiome

Stress, whether psychological, environmental, or physical, can significantly alter the composition and function of gut microbiota, which in turn affects the host's stress response and overall health (Karl et al., 2018). The gut-brain axis, a complex communication network involving the gut microbiota, plays a crucial role in regulating stress-related responses, with diet being a significant modifying factor (Foster, Rinaman, & Cryan, 2017). Stress-induced changes in the gut microbiota can lead to immune system activation and inflammation, which are linked to various stress-related conditions such as anxiety, depression, and irritable bowel syndrome (Buerel, 2024).

Moreover, early life stress has been shown to impact the gut microbiome, although consistent microbiome signatures associated with stress are yet to be identified (Agusti et al., 2023). Chronic stress can exacerbate conditions like inflammatory bowel disease by disturbing the gut microbiota and triggering immune responses (Gao et al., 2018).

Groundbreaking research in 2024 revealed that the microbiome may help explain why some people bounce back from stress while others struggle.

An and colleagues (2024) studied 116 healthy adults and discovered distinct biological signatures in the gut microbiomes of highly resilient individuals. Using brain imaging and stool samples, the researchers found that people with high psychological resilience showed microbiome activity associated with lower inflammation, better gut barrier integrity, and increased production of beneficial metabolites like N-acetylglutamate and dimethylglycine. Their brains also displayed enhanced functional connectivity between reward circuits and sensorimotor networks, suggesting better emotion regulation.

This study represents the first evidence linking resilience, brain activity, and the gut microbiome in a comprehensive model. The findings raise exciting possibilities for future interventions, with researchers suggesting that engineered probiotic blends might someday help people cope with stress and prevent stress-related diseases (An et al., 2024).

A 2025 systematic review synthesized findings from studies on gut microbiota and mental health disorders, reporting that depression was consistently associated with reduced microbial diversity and elevated levels of Firmicutes bacteria, while anxiety was linked to lower levels of short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria and higher levels of inflammatory Proteobacteria (Shaikh et al., 2025). The review noted that probiotics and dietary interventions showed promise in alleviating symptoms for many patients, sometimes matching the effectiveness of pharmaceutical treatments.

These findings underscore the growing recognition that the gut microbiome represents a viable therapeutic target for stress-related mental health conditions.

Protein Kinase C and Stress-Induced Cognitive Impairment

Birnbaum and colleagues (2004) reported that uncontrollable stressful situations activate the enzyme protein kinase C (PKC), interfering with prefrontal cortical functions like working memory. Elevated PKC levels may result in symptoms of distractibility, impulsiveness, and poor judgment seen in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Initial psychotic episodes often follow stressors like leaving home for college or the military. Very low levels of lead exposure can elevate PKC levels in children, possibly impairing their regulation of behavior and producing distractibility and impulsivity.

More recent research has expanded our understanding of how stress damages prefrontal networks. Joyce, Uchendu, and Arnsten (2025) explained that stress and neuroinflammation, the activation of immune responses within the brain, work together to weaken the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), a brain region essential for working memory and the top-down regulation of attention, action, and emotion.

When we encounter uncontrollable stress, catecholamines like norepinephrine flood the prefrontal cortex and activate feedforward PKC and cAMP-protein kinase A signaling pathways. These molecular events open potassium channels on dendritic spines, weakening synaptic connections and reducing the persistent neuronal firing that supports higher cognition.

Essentially, stress flips a neurochemical switch that shifts control of behavior from the thoughtful prefrontal cortex to more primitive brain regions like the amygdala and striatum. Chronic stress makes matters worse by causing architectural changes, including the loss of dendritic spines from prefrontal neurons, leading to lasting cognitive impairments (Joyce et al., 2025).

The connection between stress and brain inflammation has emerged as a critical research frontier. When chronic stress activates microglia, the brain's resident immune cells, these cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines that can damage neural tissue and disrupt neurotransmitter function.

Joyce and colleagues (2025) noted that neuroinflammation and stress hormones create a destructive cycle: inflammation sensitizes prefrontal circuits to the harmful effects of catecholamines, while stress-induced catecholamine release promotes further inflammation. This bidirectional relationship helps explain why people under chronic stress often experience cognitive symptoms like difficulty concentrating, poor decision-making, and memory problems.

The findings have significant implications for treatment, suggesting that anti-inflammatory strategies combined with stress reduction techniques may help protect and restore prefrontal cortex function in people experiencing chronic stress.

Stress Accelerates Aging at the Cellular Level

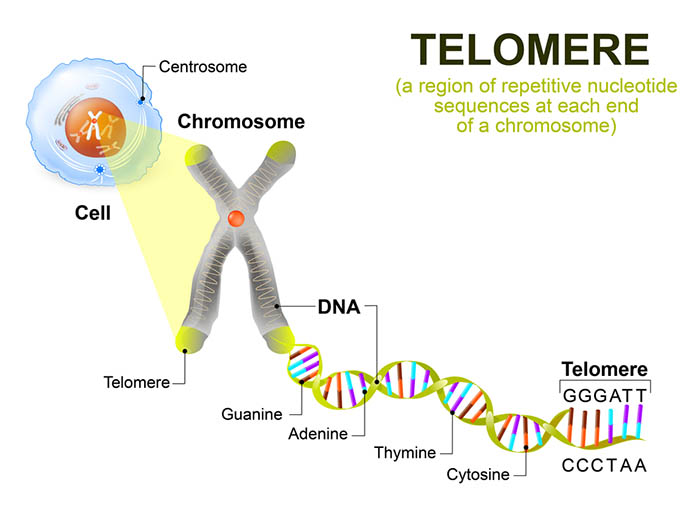

Epel and colleagues (2004) studied 58 healthy women who cared for either healthy or chronically ill children. The researchers administered a brief questionnaire that assessed chronic stress during the previous month and obtained a blood sample to measure telomere (DNA and protein that cover the ends of chromosomes) length and levels of telomerase (an enzyme that adds DNA to telomeres).

With repeated cell division, telomere DNA is lost, the telomere shortens, and eventually, cell division stops. When cells age, telomerase activity declines, and the telomere shortens.

The researchers found that the mothers of chronically ill children reported higher chronic stress levels than mothers of healthy children. More years of caring for chronically ill children were correlated with shorter telomeres and lower telomerase levels. Perceived levels of chronic stress, and not a child's actual health status, predicted telomere length. The researchers calculated that the cells of high-stress mothers had aged 9 to 17 more years than those of the low-stress mothers.

Building on these findings, Guillen-Parra and colleagues (2024) examined how chronic stress affects the cellular machinery that maintains telomeres. Their longitudinal study followed mothers caring for children with autism spectrum disorder and compared them to mothers of neurotypical children.

They measured Mitochondrial Health Index (MHI), a composite measure that reflects how well mitochondria produce cellular energy. The researchers discovered that both chronic stress exposure and lower MHI independently predicted decreases in telomerase activity over a nine-month period. Since telomerase is the enzyme that maintains telomere length, reduced telomerase activity leads to accelerated telomere shortening.

The study revealed that changes in telomere length were directly related to changes in telomerase activity and indirectly linked to both MHI and chronic stress, suggesting that stress may accelerate cellular aging partly through its effects on mitochondrial function (Guillen-Parra et al., 2024).

A comprehensive 2021 review by Chae and colleagues detailed the biological pathways through which psychological stress damages telomeres. The researchers identified three interconnected mediators: glucocorticoids like cortisol, reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial dysfunction, and chronic inflammation.

These mediators operate in positive feedback loops, meaning each one amplifies the effects of the others. For example, chronic cortisol exposure increases oxidative stress, which damages both mitochondria and telomeres, while also promoting inflammation that further accelerates telomere shortening.

The review emphasized that the duration of stress exposure matters critically: acute stress may temporarily increase telomerase activity as a protective response, but chronic stress suppresses telomerase and accelerates cellular aging. The authors also highlighted intergenerational effects, noting that parental stress can influence telomere length in offspring through both prenatal stress exposure and direct inheritance of shortened telomeres (Chae, Lin, & Blackburn, 2021).

Stress May Contribute to Mild Cognitive Impairment

Older adults enrolled in the Einstein Aging Study who reported high stress levels were twice as likely to exhibit the memory deficits associated with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which may precede Alzheimer's disease (Katz et al., 2015).

A landmark 2023 Swedish cohort study provided compelling evidence that chronic stress may increase dementia risk. Wallensten and colleagues (2023) analyzed healthcare records from over 1.3 million adults aged 18 to 65 in the Stockholm region. They tracked participants diagnosed with chronic stress or depression between 2012 and 2013.

Over an 8-year follow-up period, individuals with a history of chronic stress were nearly twice as likely to develop MCI compared to those without such diagnoses. The risk of Alzheimer's disease was similarly elevated.

Perhaps most striking, participants diagnosed with both chronic stress and depression faced up to four times the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease compared to those without either condition.

Although the researchers cautioned that causality remains uncertain, these findings underscore the importance of stress management as a potential strategy for reducing dementia risk (Wallensten et al., 2023).

Stress affects the entire body, from the gut microbiome to telomere length. The microbiome communicates with the brain through the gut-brain axis, and stress can alter microbiome composition in ways that affect mood and cognition. At the cellular level, chronic stress shortens telomeres and accelerates aging. Stress also activates protein kinase C, which can impair prefrontal cortex function and working memory.

Stressful Life Events

Cataclysmic Events Can Overwhelm Coping Resources

Lazarus and Cohen (1977) described cataclysmic events as "sudden, unique, and powerful single life-events requiring major adaptive responses from population groups sharing the experience" (p. 91).

Intentional and unintentional, these events can impact local communities (such as mass shootings), geographic regions (such as earthquakes, fires, hurricanes, and tsunamis), and the entire planet (such as the COVID-19 pandemic). These catastrophes can produce death, dislocation, fear, grief, trauma, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Many factors influence survivor response to these powerful stressful events, including perceived discrimination, resources, support, vulnerability to future harm, distance from the devastation, and media coverage. The stressfulness of an event is influenced by geographic proximity, its recency, and whether it was intended. Intentional events are more traumatic than natural disasters because the perpetrators targeted the victims and could do so again (Brannon et al., 2022).

Life Events Require Adjustment

Cataclysmic events like a pandemic are so disruptive because they change our lives in various ways: education, employment, exercise, personal and family member illness, routines, sleep, social interaction, and working conditions.

Life events differ from cataclysmic events in three ways. They affect fewer individuals. They require adjustment, whether positive (such as the birth of a child) or negative (such as the death of a loved one). Last, they can develop more slowly (such as divorce) or suddenly (such as injury in a car crash).

Holmes and Rahe (1967) measured major positive and negative life changes using their Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS). The scale lists 43 events, each assigned a different Life Change Unit (LCU) value. They arranged these events in descending order from the death of a spouse (100 LCUs) to minor law violations (11 LCUs). Individuals select the events they have experienced within the last 6 to 24 months. Researchers calculate a stress score by summing the LCU value of the checked events.

Studies that combine prospective (participants report current events) and retrospective methods (researchers examine subsequent health records) have reported increased illness and accidents following increased stressful events (Johnson, 1986; Rahe & Arthur, 1978). However, the correlation between SRRS scores and disease is around +0.30 (Dohrenwend & Dohrenwend, 1984), which means that the SRRS accounts for only 9% of the variance in disease.

🎧 Listen to a mini-lecture on the Effects of Major Life Changes and HasslesThe SRRS has received severe criticism, and its popularity has declined. Critics have argued that its positive events can reduce the risk of illness (Ray, Jefferies, & Weir, 1995). Many individuals who exceed 300 points in a year remain healthy. Scales like the SRRS underestimate African-American life stress (Turner & Avison, 2003). The SRRS assumes that an event impacts all people equally. The wording of some items is vague (such as "change in responsibilities at work"). Pessimism can distort recollections of life events (Brett et al., 1990). Finally, the scale does not consider whether an event has been resolved (Turner & Avison, 1992) or an event's controllability or probability (Gump & Matthews, 2000).

The Undergraduate Stress Questionnaire (USQ) developed by Crandall and colleagues (1992) instructs students to select events, mostly hassles, they have experienced during the past two weeks. Higher USQ scores are associated with increased use of health services.

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) developed by Cohen and colleagues (1983) measures perceived hassles, major life changes, and shifts in coping resources during the previous month using a 14-item scale. PSS items assess the degree to which respondents rate their lives as unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded (p. 387). The PSS achieves good reliability and validity (Brannon, Feist, & Updegraff, 2022). PSS scores predict cortisol levels (Harrell et al., 1996), fatigue, headache, sore throat (Lacey et al., 2000), and immune changes (Maes et al., 1997).

Hassles and Uplifts: The Small Stuff Matters

A hassle is a minor stressful event like waiting in a checkout line or experiencing a traffic jam. Hassles can produce illness via several pathways. First, hassles can cause accumulating allostatic load. Second, hassles can amplify the effects of adverse life events and chronic stress (Marin et al., 2007; Serido et al., 2004; Taylor, 2021).

Graig's (1993) concept of urban press illustrates how ever-present environmental stressors (such as alienation, crowding, fear of crime, noise, and pollution) acting in concert as daily hassles can increase death from heart attacks (Christenfeld et al., 1999). As with stressors in general, an individual's perception of daily hassles like noise and population density determines their effects on behavior, health, and performance (Brannon et al., 2022; Evans & Stecker, 2004; Schell & Denham, 2003). For example, crowding is our perception of density, influenced by our perceived degree of control.

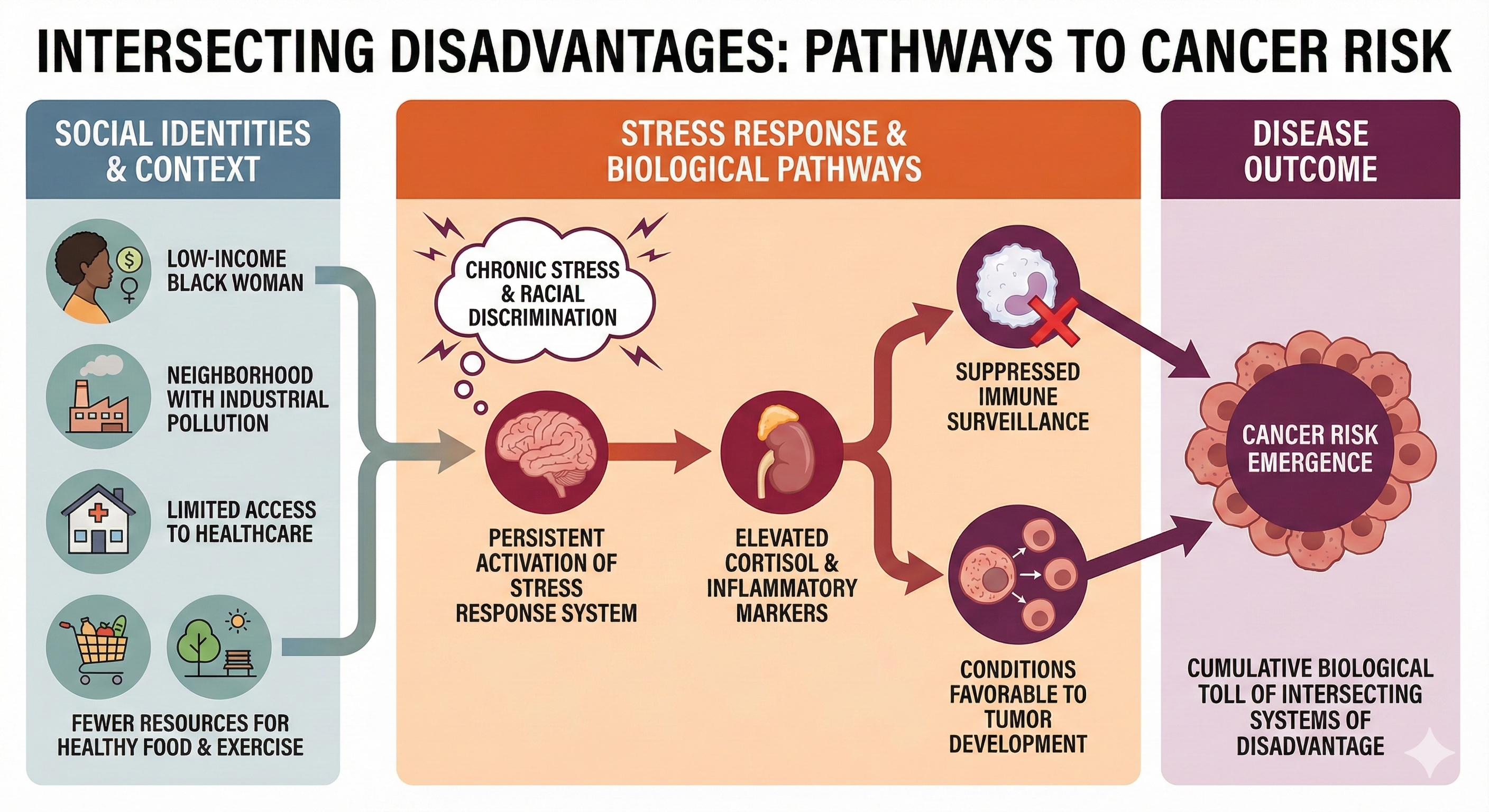

Discrimination experienced in the classroom, community, family, media, and workplace is another source of daily hassles. Discrimination based on age, biological sex, ethnicity, gender identity, and religion can disadvantage and physically endanger individuals and threaten their mental and physical health (Brannon et al., 2022; Pascoe & Richman, 2009; Troxel et al., 2003). Discrimination has elevated the risk of suicide in the bisexual, gay, lesbian, and transgender communities (Haas et al., 2011). Further, Anti-Asian hate has resulted in a wave of attacks against Asian Americans.

Social identities (such as biological sex, class, gender identity, and race) can interact with stressors and the environment to produce diseases like cancer. For example, a low-income Black woman living in a neighborhood with industrial pollution might face a perfect storm of risk factors—chronic stress from financial strain and racial discrimination, limited access to preventive healthcare, greater environmental toxin exposure, and fewer resources for healthy food or safe spaces to exercise. The persistent activation of her stress response system elevates cortisol and inflammatory markers, which over time can suppress immune surveillance and create conditions favorable to tumor development.

Her cancer risk emerges not from any single factor but from the cumulative biological toll of navigating intersecting systems of disadvantage that simultaneously assault her body through multiple pathways.

An uplift is a minor positive event like receiving an unexpected call from a friend or playing with new puppies.

Kanner and colleagues (1981) developed a 117-item Hassles Scale and 138-item Uplifts Scale to measure negative and positive daily experiences. Respondents selected the hassles and uplifts they experienced during the previous month. Next, they rated the degree to which they experienced each selected item on a 3-point scale to assess their perception of each stressor. They found a moderate correlation between hassles and major life changes. Lazarus (1984) reported that the Hassles Scale better predicted health outcomes than the SRRS.

Stressful life events range from cataclysmic events that affect entire populations to daily hassles like traffic jams. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale measures major life changes but has significant limitations. The Perceived Stress Scale better captures individual perception of stress. Daily hassles can accumulate and amplify the effects of major stressors. Discrimination represents a chronic source of hassles that affects marginalized groups, and intersectionality explains how multiple social identities interact to create unique patterns of disadvantage.

Check Your Understanding

- What are cataclysmic events, and why are intentional events more traumatic than natural disasters?

- What are the main criticisms of the Social Readjustment Rating Scale?

- How do daily hassles contribute to illness?

- What is intersectionality, and how does it relate to stress?

Psychological Factors in Stress

Affective States and the Circumplex Model

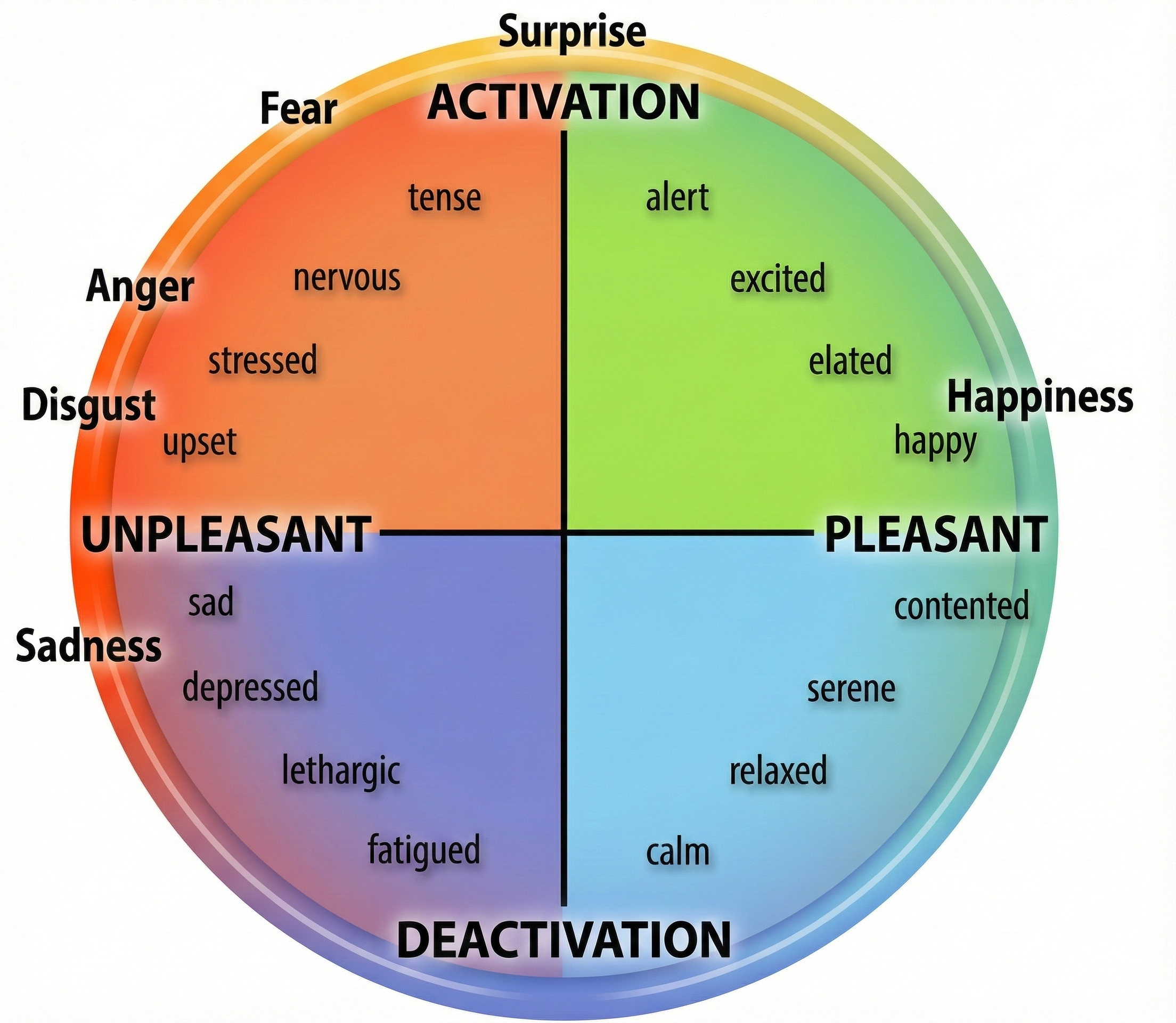

Barrett and Russell (1999) proposed a structural model that organizes affective states within a circumplex (circular structure) based on its degrees of affective valence (unpleasant to pleasant) and affective intensity (activation to deactivation). Specific affective states fall inside or along the surface of this circular structure.

Negative states (sad) are located in the left hemisphere and positive states (contented) are located in the right hemisphere. Activated states (tense) are placed in the top hemisphere, and deactivated states (fatigued) are placed in the bottom hemisphere. While adjacent affective states (stressed and nervous) most resemble each other, those 180° apart (stressed and relaxed) are opposites. After clinicians identify their clients' position within the circumplex, they may intervene to shift them to a more appropriate affective state, like relaxed instead of nervous.

Researchers have reported psychophysiological correlates of the affective valence and activation dimensions. Surface EMG (SEMG) and EEG can help assess affective valence. SEMG measurements of the zygomatic (smiling) and corrugator (frowning) muscles are correlated with positive and negative affect (Lang et al., 1993). Higher left/right prefrontal cortex activation ratios are correlated with positive affect, while reverse ratios are correlated with negative affect (Sutton & Davidson, 1997). Sympathetic nervous system modalities like electrodermal activity are associated with affective intensity (Crider, 2004; Lang et al., 1993).

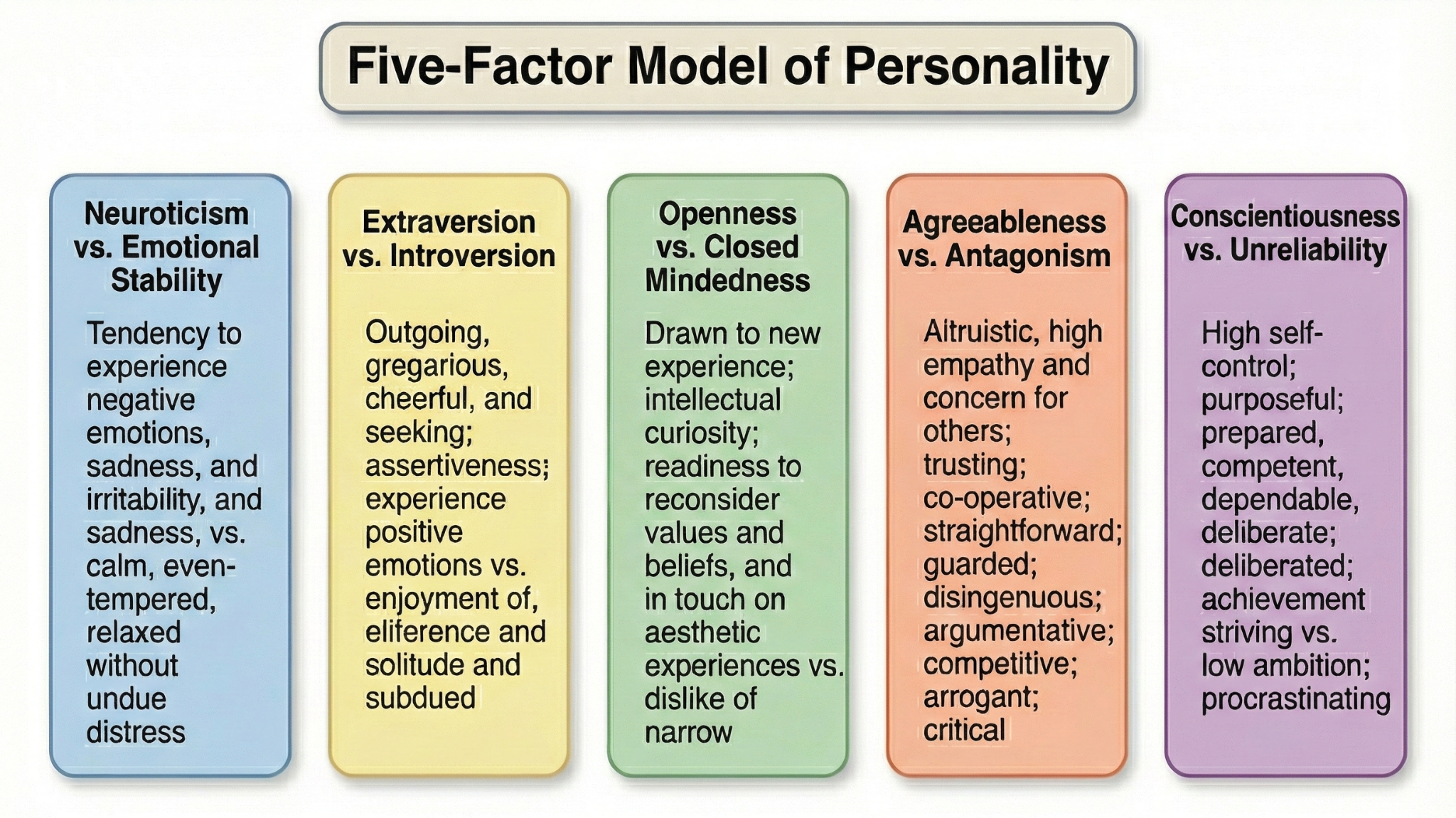

Negative affectivity (neuroticism) is a predisposition toward distress and dissatisfaction. Individuals rated high on this trait negatively perceive themselves, others, and the environment and have a pessimistic perspective. They rank more events as stressful, report more intense stress, complain more frequently about health problems, and report more severe symptoms when physically ill than those with lower negative affectivity (Cohen et al., 1995; Gunthert et al., 1999). Negative affectivity may increase vulnerability to stressors and health conditions like anxiety and depressive disorders they exacerbate (Brannon et al., 2022).

The Type D (distressed) personality combines high negative affectivity and social inhibition levels. Individuals rated high on this dimension cannot communicate their distress with others. Researchers have studied the relationship between negative emotionality and social inhibition and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Negative emotionality is positively correlated with Neuroticism, whereas social inhibition is negatively correlated with Conscientiousness and Agreeableness (De Fruyt & Denollet, 2002).

The Type D personality better predicted the buildup of arterial plaque than the Type A behavior pattern (Lin et al., 2018). However, although initial studies suggested that Type-D coronary artery disease patients have poorer prognoses, later studies (Bishop, 2016; Meyer et al., 2014) have not consistently supported this association.

Anxiety and Heart Disease

A Framingham study report by Markovitz et al. (1993) showed that men with elevated anxiety had twice the risk of middle-age hypertension as men with lower anxiety. This increased risk was not found for women. A prospective study by Kawachi et al. (1994) revealed that men diagnosed with phobic anxiety had a three times greater risk of sudden cardiac death. Albert et al. (2005) found that women diagnosed with phobic anxiety had a 59% greater risk of sudden cardiac death and a 31% greater risk of fatal coronary heart disease than women who scored low. These increased risks were associated with risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol.

Depression and Cardiovascular Risk

Pratt et al. (1996) reported that depressed individuals had a four times greater risk of a heart attack in the next 14 years than non-depressed individuals. Frasure-Smith et al. (1995) found that depressed heart attack patients had a four times greater risk of another heart attack in the next 18 months than non-depressed heart attack patients. Carney et al. (2005) discovered that depressed heart attack patients were almost three times more likely to die over 30 months than non-depressed heart patients. Decreased heart rate variability accounted for a significant share of the increased risk of death.

Jonas and Mussolino (2000) found in a 16-year longitudinal study that participants diagnosed with depression had a 70% greater risk of stroke mediated by ethnicity. Stroke risk was higher for depressed European American men than women and depressed African Americans than European Americans. Everson et al. (1998) reported that depressed individuals had a greater risk of death from stroke than nondepressed participants.

A landmark 2025 meta-analysis and Mendelian randomization study by Liu and colleagues provided the most comprehensive examination to date of the depression-cardiovascular disease relationship. Analyzing 39 studies involving 63,444 cardiovascular patients, the researchers found an estimated overall prevalence of depression of 20.8% among those with cardiovascular disease, with heart failure patients showing the highest rates at 24.7%.

Depressive symptoms were associated with more than double the unadjusted all-cause mortality rate compared to non-depressed patients. The Mendelian randomization analysis, which uses genetic variants to test for causal relationships, provided the first genetically-informed evidence that depression plays a critical role in both the development and progression of certain cardiovascular conditions. Specifically, the analysis revealed significant causal associations between major depressive disorder and coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and hypertension (Liu et al., 2025).

A 2024 review in Frontiers in Psychiatry summarized the bidirectional relationship between depression and coronary heart disease. The authors reported that even after accounting for traditional risk factors such as hypertension and obesity, the incidence of coronary heart disease was three times higher in individuals with depression (Xu, Zhai, Shi, & Zhang, 2024).

Depression constituted a significant independent risk factor for mortality in coronary heart disease patients, with one study showing a hazard ratio of 3.19 and demonstrating that depression severity correlated with worse prognosis and higher incidence of adverse cardiovascular outcomes.

Type A-B Continuum and Heart Disease

Friedman and Rosenman (1974) proposed the Type A-B continuum of risk for coronary artery disease. They described extreme Type A's as competitive, concerned with numbers and acquisition, hostile, and time-pressured. In contrast, Type B's are less motivated and do not usually exhibit Type A behaviors. Their study of 3,000 men over 8.5 years showed that Type A behavior doubled the risk of a heart attack. The National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (1981) concluded that Type A behavior is an independent risk for heart disease.

Despite early hopes that the global Type A behavior pattern could independently predict heart disease, current research has not consistently supported this association (Brannon et al., 2022; Espnes & Byrne, 2016).

Hostility: The Toxic Component of Type A

Hostility is a negative attitude about others, not an emotion. Hostility is the toxic component of the Type A behavior pattern. In contrast, anger is a difficult emotion associated with physiological arousal. Longitudinal studies suggest a modest predictive relationship between hostility, hypertension (Yan et al., 2003), and cardiovascular disease (Chida & Steptoe, 2009).

Anger and Cardiovascular Reactivity

Taylor (2012) proposed that cardiovascular reactivity (changes in cardiovascular function due to physical or psychological challenge) and hostility in conflict situations might promote heart disease. The disease pathways may involve changes in blood vessels and catecholamine levels, sympathetic nervous system release of lipids into circulating blood, and blood platelet activation.

Anger is a difficult emotion that involves physiological arousal and persists for a brief period. Siegman and colleagues (1987) proposed that the expression of anger, and not our experience of it, could result in heart disease. Examples of expressed anger include raising your voice during arguments and temper tantrums (Brannon et al., 2022).

Jain and colleagues (1995) monitored patients using an electronic stethoscope. When patients were angry, the researchers observed declines in the heart's ejection fraction (the ratio of blood pumped by the left ventricle during a contraction compared to its total filling volume). Bhat and Bhat (1999) demonstrated that an intervention to manage anger using biofeedback significantly increased their patients' ejection fraction.

Expressed anger may contribute to heart disease by increasing cardiovascular reactivity (CVR), often revealed as increased blood pressure and heart rate in response to social stressors like a provocation.

Dujovne and Houston (1991) linked expressed hostility with increased total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) in men and women. Goldman (1996) reported that individuals classified with high anger had a 2.5 times greater chance of re-clogging arteries after angioplasty. Siegman and colleagues (1992) found that training to slow speech rate and lower speech volume reduced CVR.

Researchers have shown that provocation can increase cardiovascular reactivity. Smith and Brown (1991) found that when provoked, women showed less CVR than men. While husbands increased their heart rate and systolic blood pressure while trying to control their wives, they did not experience these changes when trying to control their husbands. The wives' systolic blood pressure only increased when their husbands expressed cynical hostility.

After provoking male undergraduates, Siegman, Anderson, Herbst, Boyle, and Wilkinson (1992) observed increased heart rate and blood pressure (diastolic and systolic). The subjects reported experiencing considerable anger following their provocation.

Fredrickson et al. (2000) asked adult men and women to re-experience earlier anger experiences. More hostile participants produced larger and longer-duration blood pressure increases than less hostile individuals. Also, African Americans showed greater CVR than European Americans.

Bishop and Robinson (2000) studied Chinese and Indian men in Singapore who performed a difficult task either with or without harassment. The harassed participants showed greater CVR than those who were not provoked.

Smith et al. (2004) reported that high-hostile husbands experienced greater cardiovascular reactivity during stressful interactions with their wives than low-hostile husbands.

Suppressed Anger Can Also Be Harmful

Diamond (1982) hypothesized an anger-in dimension, which is the tendency to withhold the expression of anger, even when anger is warranted. Dembroski and colleagues (1985) reported that anger suppression could contribute to heart disease. Siegman (1994) recommended that patients develop an awareness of their anger but express it using a quiet, slow voice.

Psychological factors including affective states, anxiety, depression, and anger patterns all influence stress responses and health outcomes. The circumplex model organizes affective states by valence and intensity. Negative affectivity and the Type D personality increase vulnerability to stress. While the global Type A pattern no longer shows consistent associations with heart disease, hostility remains the toxic component linked to cardiovascular risk. Both expressed anger and suppressed anger can harm cardiovascular health.

Check Your Understanding

- How does the circumplex model organize affective states?

- What is negative affectivity, and how does it affect stress perception?

- Why is hostility considered the toxic component of the Type A behavior pattern?

- How does cardiovascular reactivity relate to anger and heart disease risk?

Acute and Chronic Stress Responses

Acute Stress Activates the Fight-or-Flight Response

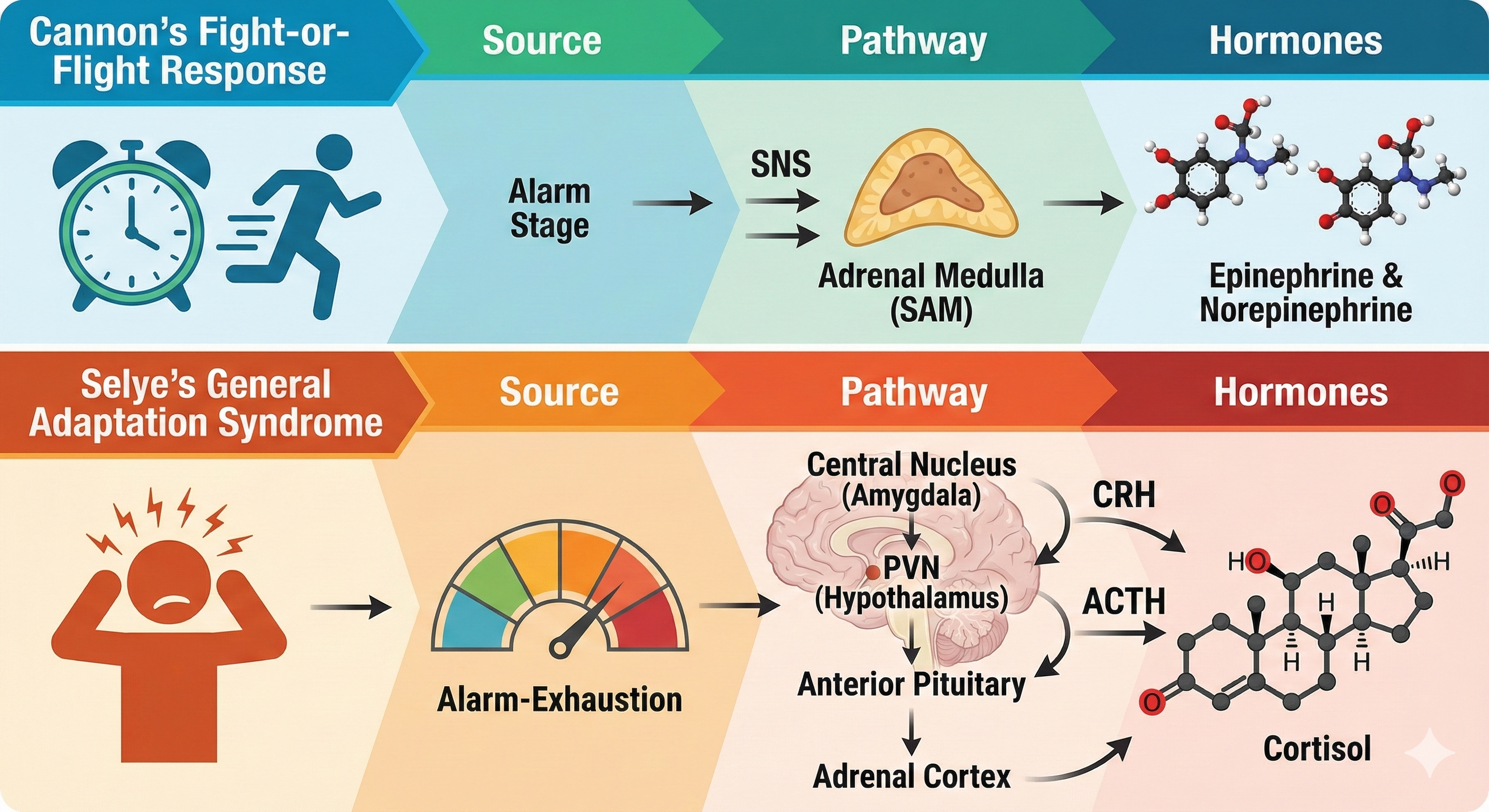

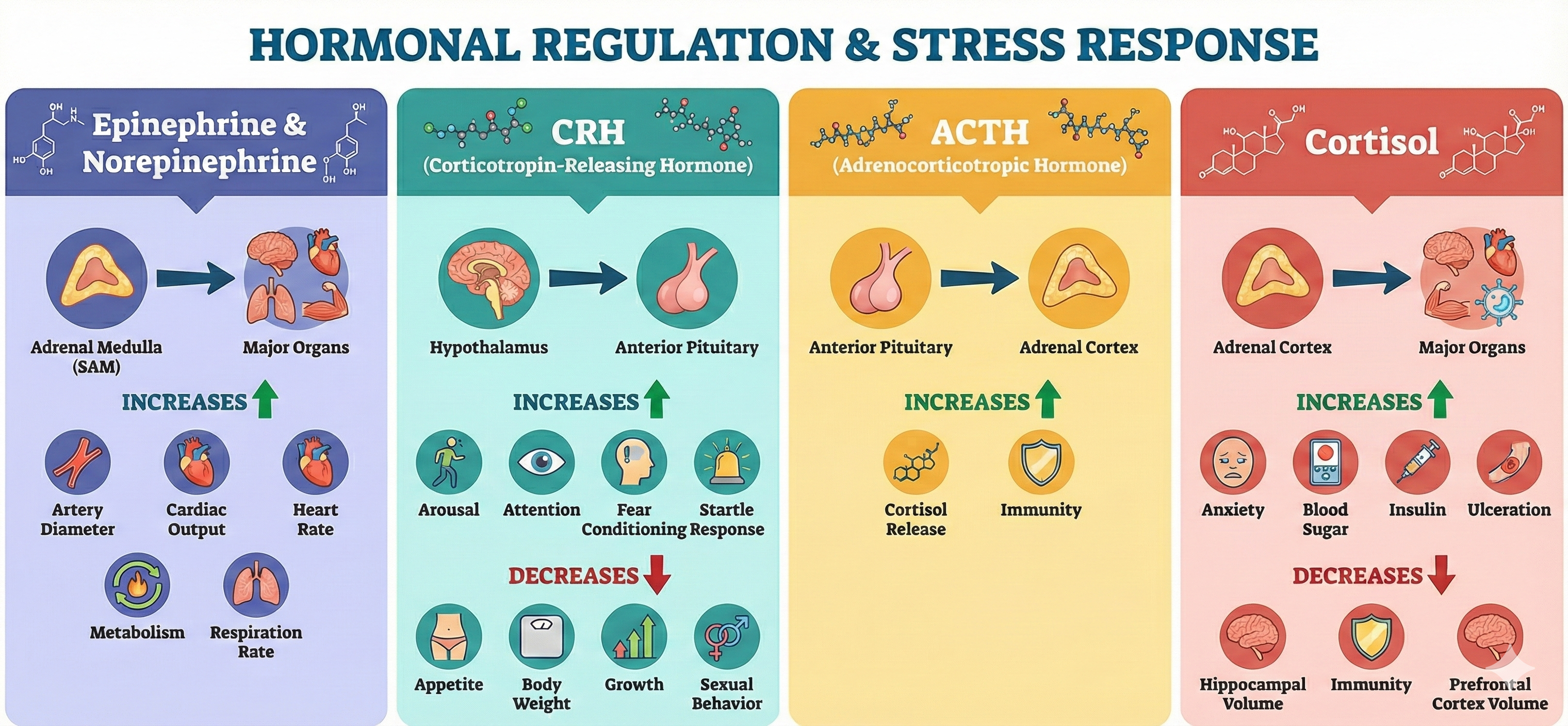

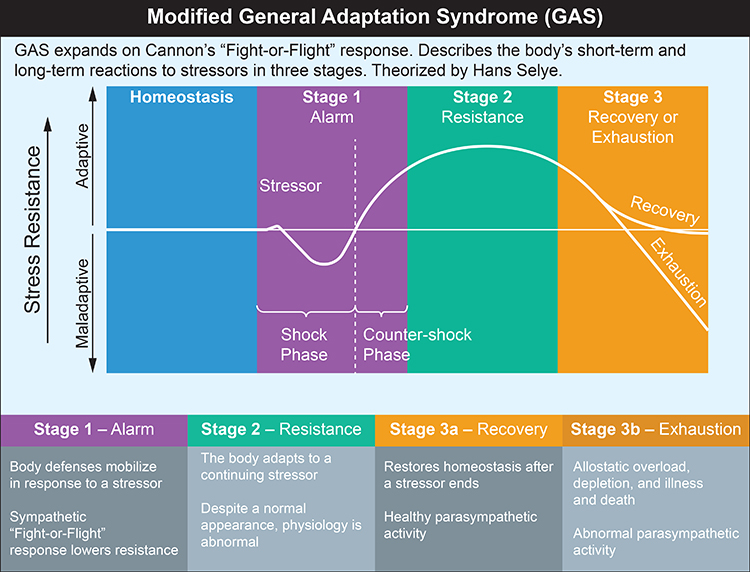

Cannon's fight-or-flight response focuses on sympathetic nervous system responses to an acute stressor and describes the sympathetic-adrenomedullary (SAM) pathway that releases the hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine. Selye's General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) describes our prolonged response to a chronic stressor across three stages. The GAS summarizes changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which releases the hormones CRH, ACTH, and cortisol, and explains how chronic stress can produce disease and death.

The Fight-or-Flight Response in Detail

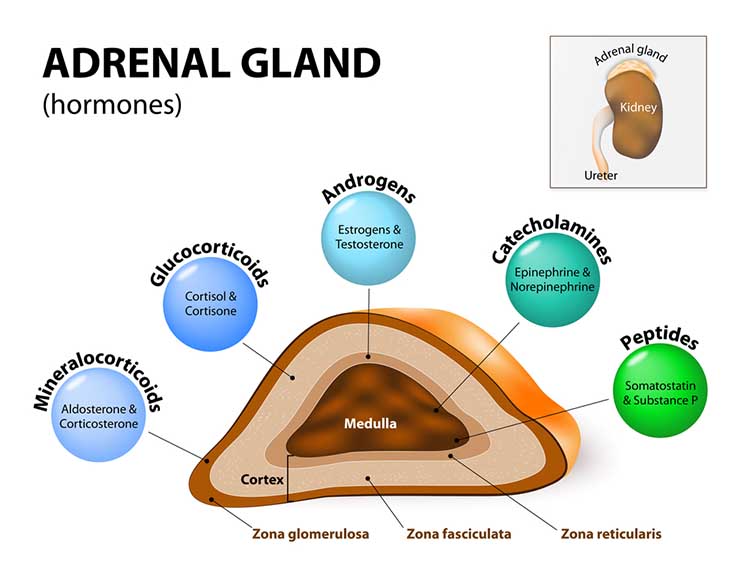

Cannon (1932) described the fight-or-flight response, in which an individual confronts or flees a stressor. During an acute stress response, which corresponds to the end of Selye's alarm stage, we activate the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), increasing respiration, cardiac output, blood flow to skeletal muscles, and metabolism while decreasing digestion and reproductive system activity. The SNS, in turn, activates the hard-wired sympathetic-adrenomedullary (SAM) pathway, resulting in the release of the hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine by the adrenal medulla (inner adrenal gland).

🎧 Listen to a mini-lecture on the SAM Pathway

The adrenal medulla releases epinephrine and norepinephrine in a 4:1 ratio (Fox, 2019). The adrenal medulla is the inner region of the adrenal glands located at the top of each kidney.

The Challenge Response: A Healthier Alternative

While the fight-or-flight response evolved to help us escape predators, not all stressors require such an extreme reaction. The Biopsychosocial Model (BPS) of Challenge and Threat proposes that how we appraise a stressor determines whether we mount a healthy challenge response or a potentially harmful threat response (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1996; Seery, 2013). When we evaluate our coping resources as sufficient to meet situational demands, we experience a challenge response. When demands seem to exceed our resources, we experience a threat response that resembles the classic fight-or-flight pattern.

These two stress responses differ in their hormonal signatures. Both activate the sympathetic-adrenomedullary (SAM) axis, releasing catecholamines that increase heart rate and mobilize energy. However, the threat response additionally activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, producing elevated cortisol levels (Hase et al., 2025). Research has identified the cortisol-to-DHEA ratio as a key biomarker distinguishing these responses. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is an adrenal hormone with anti-glucocorticoid properties that can buffer the harmful effects of cortisol (van Honk et al., 2024). A challenge state is marked by increased DHEA relative to cortisol, while a threat state shows elevated cortisol relative to DHEA (Crum et al., 2017; Yeager et al., 2016).

The cardiovascular consequences of these responses differ dramatically. During a challenge response, blood vessels dilate, cardiac output increases, and total peripheral resistance decreases, efficiently delivering oxygenated blood to the brain and muscles (Seery, 2013). During a threat response, blood vessels constrict while the heart pumps harder, creating an inefficient pattern where the cardiovascular system works against itself (Blascovich, 2008). In healthy coronary arteries, mental stress typically produces dilation or no change. However, in atherosclerotic arteries, mental stress causes paradoxical constriction, particularly at stenotic sites (Yeung et al., 1991). This explains why psychological stress can trigger angina and cardiac events in people with coronary artery disease.

A 2025 meta-analysis of 62 studies confirmed that individuals in a challenge state achieve better performance outcomes than those in a threat state across multiple domains including sports, education, and healthcare (Hase et al., 2025). While the long-term health implications continue to be studied, repeated threat responses are associated with accelerated cognitive decline and increased cardiovascular disease risk (McLoughlin et al., 2024). These findings suggest that learning to appraise stressors as challenges rather than threats may protect both performance and health.

The HPA Axis Responds to Chronic Stress

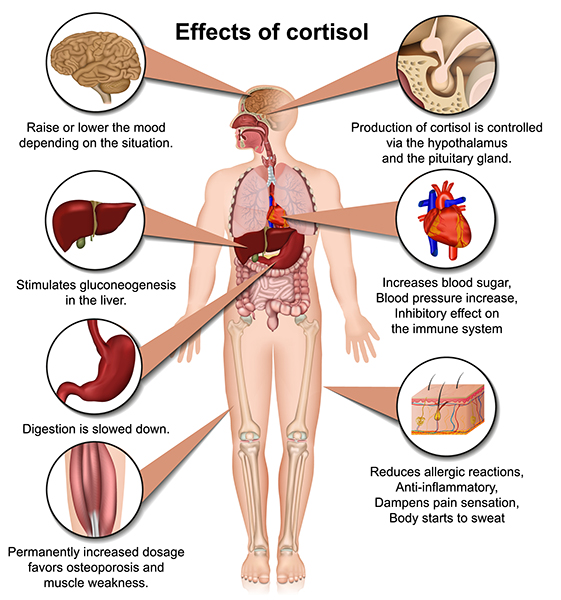

Sustained elevated cortisol levels can affect mood and produce system-wide damage.

CRH: The First Signal in the HPA Axis

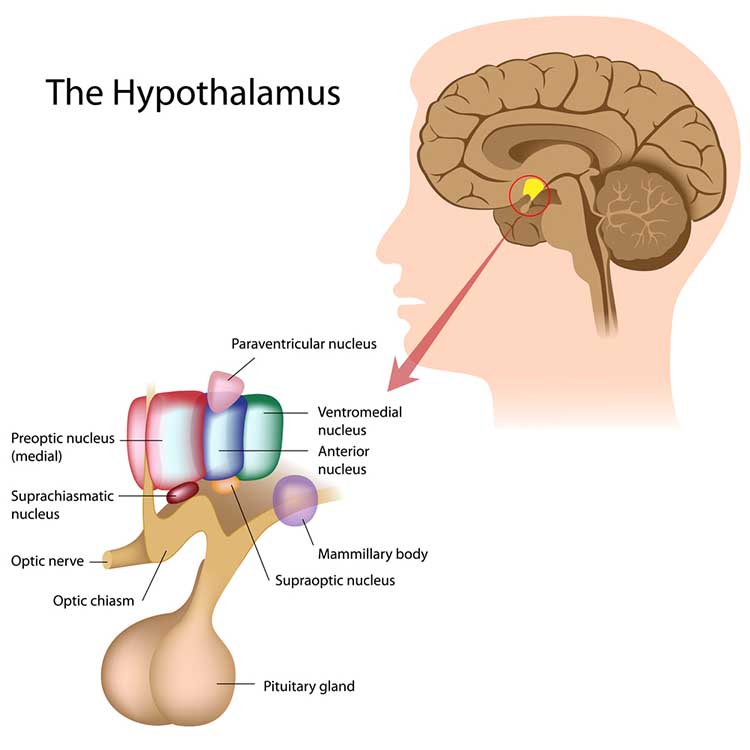

In response to stressful stimuli, the amygdala's central nucleus activates the hypothalamus' paraventricular nucleus (PVN), resulting in increased CRH release to the pituitary gland.

Chronic, elevated CRH levels in the bloodstream may enhance learning classically conditioned fear responses, heighten arousal and attention to increase readiness to respond to a stressor, intensify the startle response, and reduce appetite and body weight, sexual behavior, and growth.

ACTH Triggers Cortisol Release

When CRH binds to the pituitary gland, it releases corticotropin (ACTH). ACTH triggers cortisol release by the adrenal cortex (outer part) and helps resist infection.

Cortisol Has Widespread Effects

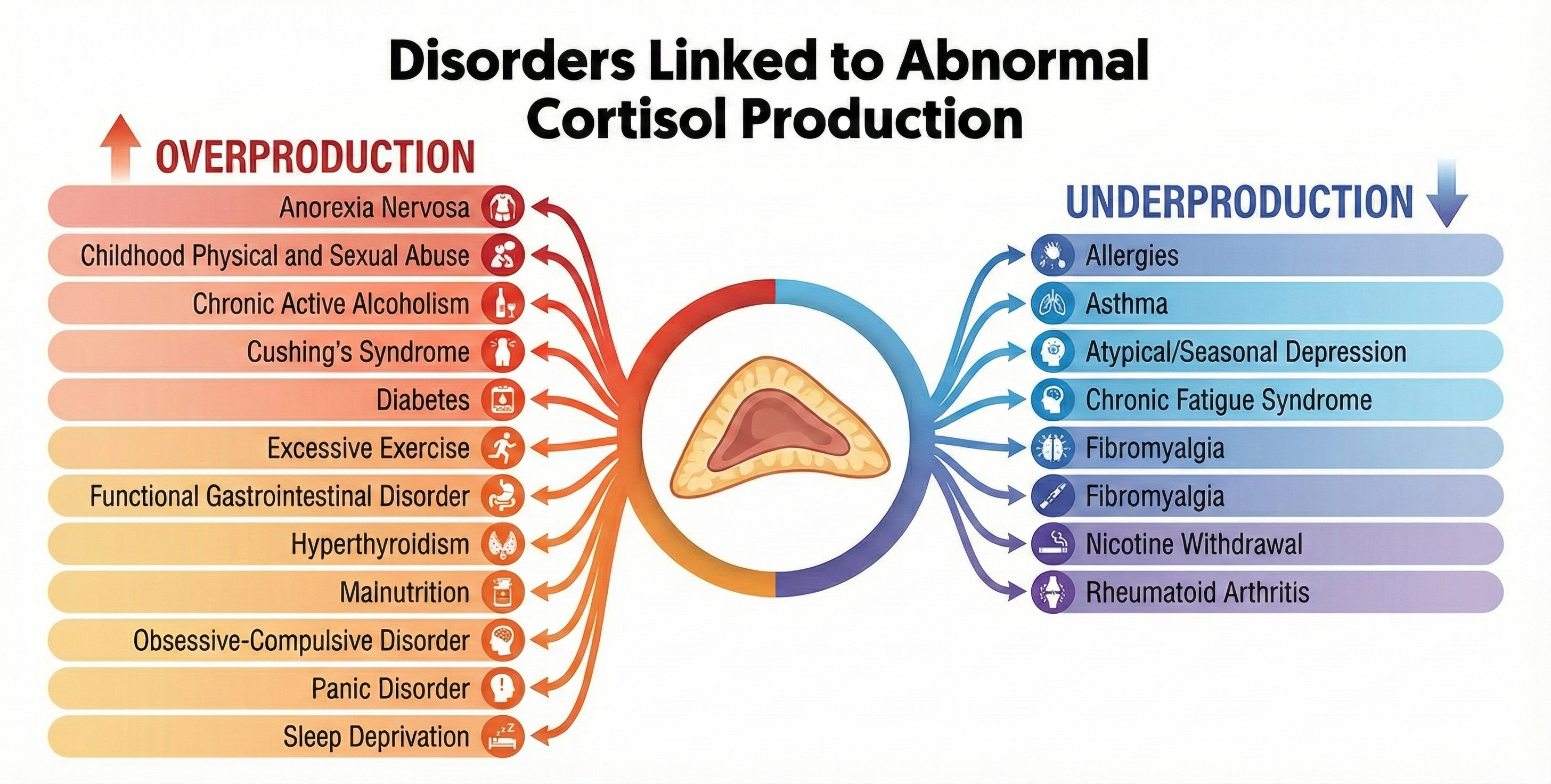

Cortisol exerts widespread effects on critical body organs (Kemeny, 2003) and cortisol levels in the blood index stress, peaking 20 to 40 minutes following a stressor (Brannon et al., 2022).

🎧 Listen to a mini-lecture on CortisolCortisol increases our activity and appetite. It helps convert fat and protein to glucose. Cortisol has short-term and long-term effects on immunity. At first, cortisol directs white blood cells to sites of infection or wounds, increases their stickiness and adherence to blood vessels and damaged tissue, and communicates when immune activity is sufficient. Cortisol's long-term effect, however, is impaired immune function (McEwen, 2002).

In healthy individuals, cortisol levels are highest in the early morning, when they help wake us up, and are lowest at night. In severely depressed individuals, the cortisol rhythm is suppressed, and its levels remain moderately high over 24 hours. Chronically elevated cortisol levels in the bloodstream adversely affect many organs, including the brain.

Allostatic load can result in hyperglycemia (elevated blood sugar), insulin insensitivity (prevents insulin from transporting glucose into skeletal muscles), increased gastric acid secretion, and ulcers. Muscle protein is converted to fat. Fat storage in the abdomen increases, which endangers health more than storage in the hips and thighs. Bone mass is reduced due to the loss of minerals (McEwen, 2002).

Cortisol release can affect gene transcription, thus producing long-term and immediate effects on the body and setting the stage for several physical and psychological disorders (panic, PTSD, and somatization).

While we've seen how allostatic load can result in chronically elevated HPA axis release of cortisol, the opposite pattern, underproduction of cortisol, also occurs. Cortisol suppresses the immune system, which reduces inflammation and swelling, and moderates chronic pain. Low cortisol levels can result in allergies, asthma, autoimmune disorders like rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, and chronic pain syndromes like fibromyalgia (McEwen, 2002).

Cortisol binding to the amygdala increases CRH and ACTH. Cortisol release amplifies the fear response, increases our ability to store implicit memories about stressful stimuli, and increases the amygdala's ability to escape the prefrontal cortex's regulation of emotional behavior.

Cortisol binding to the hippocampal formation disrupts the medial temporal lobe memory system's creation of explicit (conscious) memories. Cortisol interferes with hippocampal regulation of the PVN of the hypothalamus. Chronically elevated cortisol levels harm and kill hippocampal neurons. Cortisol suppresses neuronal repair by BDNF and interferes with creating new neurons. The elderly are more vulnerable to cortisol's harmful effects because they more slowly shut down their stress response. Their cortisol negative feedback loop functions less efficiently than in younger individuals (McEwen, 2002).

Two pathways from the raphe system terminate in the hippocampus: an anxiogenic (anxiety-producing) pathway, and an anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing) pathway. Elevated cortisol levels suppress the anxiolytic pathway and facilitate the anxiogenic pathway. These changes heighten anxiety in a chronically stressed individual.

Cortisol binding to the dorsolateral and ventromedial prefrontal cortex injures and kills neurons as in the hippocampus. Cortisol disrupts executive functions like attention and decision-making, increasing anxiety and fear.

Men and Women Respond Differently to Stressors

Taylor and colleagues argue that men's and women's behavioral and neuroendocrine responses to stressors differ, largely because of oxytocin. The posterior pituitary releases oxytocin when we encounter stressors. While traditionally known for its role in childbirth and breastfeeding, oxytocin is now recognized as a stress hormone that promotes social engagement and may protect cardiovascular health (Quintana et al., 2013).

Although they share the same nervous system reactions to stressors, men tend to react with fight-or-flight while women respond with tend-and-befriend. Taylor and colleagues (2000) theorize that a tend-and-befriend response is an alternative reaction to stressors. They believe tending (nurturing behavior) and befriending (seeking and providing social support) may characterize women better. The tend-and-befriend response may protect their safety and the lives of their offspring.

Their higher oxytocin levels cause women to seek and provide greater support when distressed than men (Bodenmann et al., 2015; Tamres et al., 2002; Taylor et al., 2000). Supporting this view, women reporting relationship stress have higher blood oxytocin levels (Taylor et al., 2006; Taylor, Saphire-Bernstein, & Seeman, 2010). An interaction may mediate this response between oxytocin and estrogen and endogenous opioids.

Oxytocin as a Cardiovascular Protector

Research has revealed that oxytocin does far more than promote social bonding; it actively modulates cardiovascular responses to stress. In a placebo-controlled experiment, Norman and colleagues (2012) found that participants given intranasal oxytocin responded to social stress with a challenge-oriented cardiovascular pattern, characterized by increased cardiac output and reduced total peripheral resistance. This efficient pattern contrasts sharply with the threat response, where the heart and blood vessels work against each other. Oxytocin administration also increased vagal tone, suggesting enhanced parasympathetic activity that could protect heart health over time.

Animal research has demonstrated that oxytocin in the hypothalamus mediates social buffering, the phenomenon whereby social contact reduces stress responses (Smith & Wang, 2014). When prairie voles were exposed to immobilization stress, those who recovered with their partner showed lower corticosterone levels and reduced anxiety-like behaviors compared to those recovering alone. Blocking oxytocin receptors eliminated these social buffering effects. Oxytocin also increases heart rate variability and may contribute to resilience by helping individuals return to homeostasis more quickly after stressful events (Quintana et al., 2013; Onaka & Takayanagi, 2021).

Chronic Stress and the General Adaptation Syndrome

Selye's Three-Stage Model

The General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) was Selye's (1956) three-stage model of chronic autonomic and endocrine system responses to stressors.

🎧 Listen to a mini-lecture on the General Adaptation SyndromeSelye argued that diverse stressors produce a three-stage response (alarm, resistance, and exhaustion) in all subjects. In this model, a cold stressor is interchangeable with a shock stressor because they produce the same autonomic and endocrine responses. Whereas Cannon showed that acute stress could change the functions of our internal organs, Selye mainly demonstrated using animal models that chronic stress can change their structure (Crider, 2004).

Alarm is the first stage of Selye's GAS and consists of shock and countershock phases. The shock phase includes reduced body stress resistance and increased autonomic arousal and hormone release (ACTH, cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine) that comprise the fight-or-flight response. In the countershock phase, resistance increases due to local defenses.

Resistance is the second stage of Selye's General Adaptation Syndrome. Local defenses have made the generalized stress response unnecessary. Both cortisol output and stress symptoms, like adrenal gland enlargement, decline. While the person appears normal, adaptation to the stressor places mounting demands on the body, leading to diseases of adaptation like hypertension as adaptation energy is depleted. Local defenses will break down if stressors persist. McEwen calls these adjustments allostatic load.

Recovery or Exhaustion is the third stage of Selye's General Adaptation Syndrome. We recover when a stressor has ended, and we can restore homeostasis. In exhaustion, increased endocrine activity depletes body resources and raises cortisol levels, resulting in suppressed immunity and stress syndrome symptoms. Selye believed these changes could cripple immunity and cause bronchial asthma, cardiovascular disease, depression, hypertension, hyperthyroidism, peptic ulcer, ulcerative colitis, and possibly death (Brannon et al., 2022).

While Selye conceptualized stress as the outcome of the three-stage GAS, stress may occur at any time. Individuals may experience stress-related changes in anticipation of an event or after it has ended. Chronic resistance may produce more significant harm than exhaustion (Taylor, 2021).

While Selye made a landmark contribution to our understanding of the role of chronic stress and glucocorticoid-mediated damage in disease, critics have challenged his characterization of the stress response as nonspecific and his conceptualization of stressors. Critics have questioned the GAS on four issues.

First, since most of Selye's research subjects were nonhuman animals, this may have caused him to overlook the role of human emotion and cognitive appraisal in the chronic stress response.

Second, since Selye focused on stressors instead of human characteristics like biological predispositions and personality, he mistakenly assumed a uniform response to stressors. Stressors can produce different hormonal responses (Kemeny, 2003).

Third, while Selye emphasized the role of exhaustion in disease, there is more evidence that chronic resistance may produce more significant harm (Taylor, 2012).

Fourth, while Selye conceptualized stress as the outcome of the GAS, both the anticipation of an event and coping with it during the resistance stage can disrupt performance and produce suffering (Taylor, 2012).

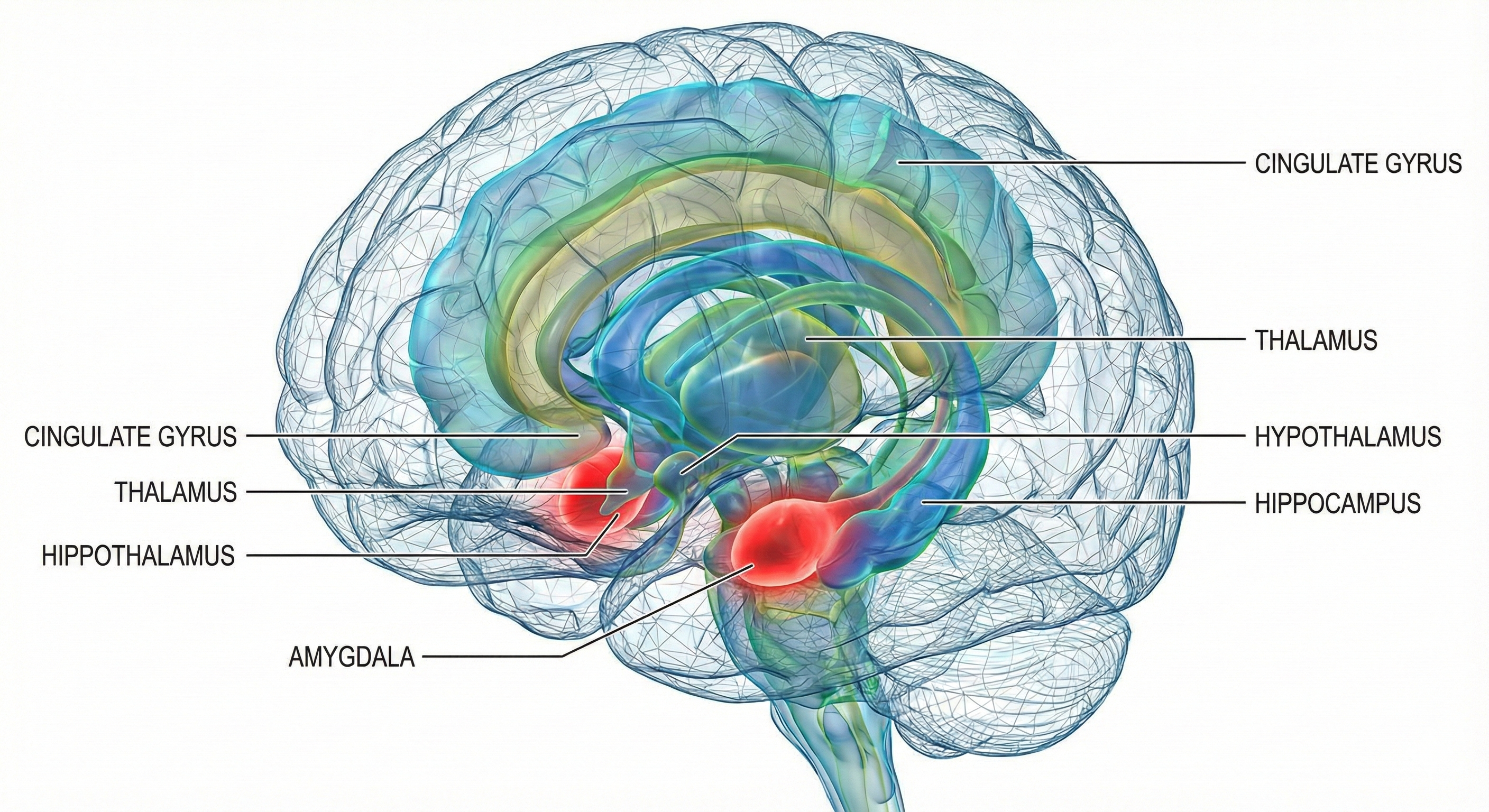

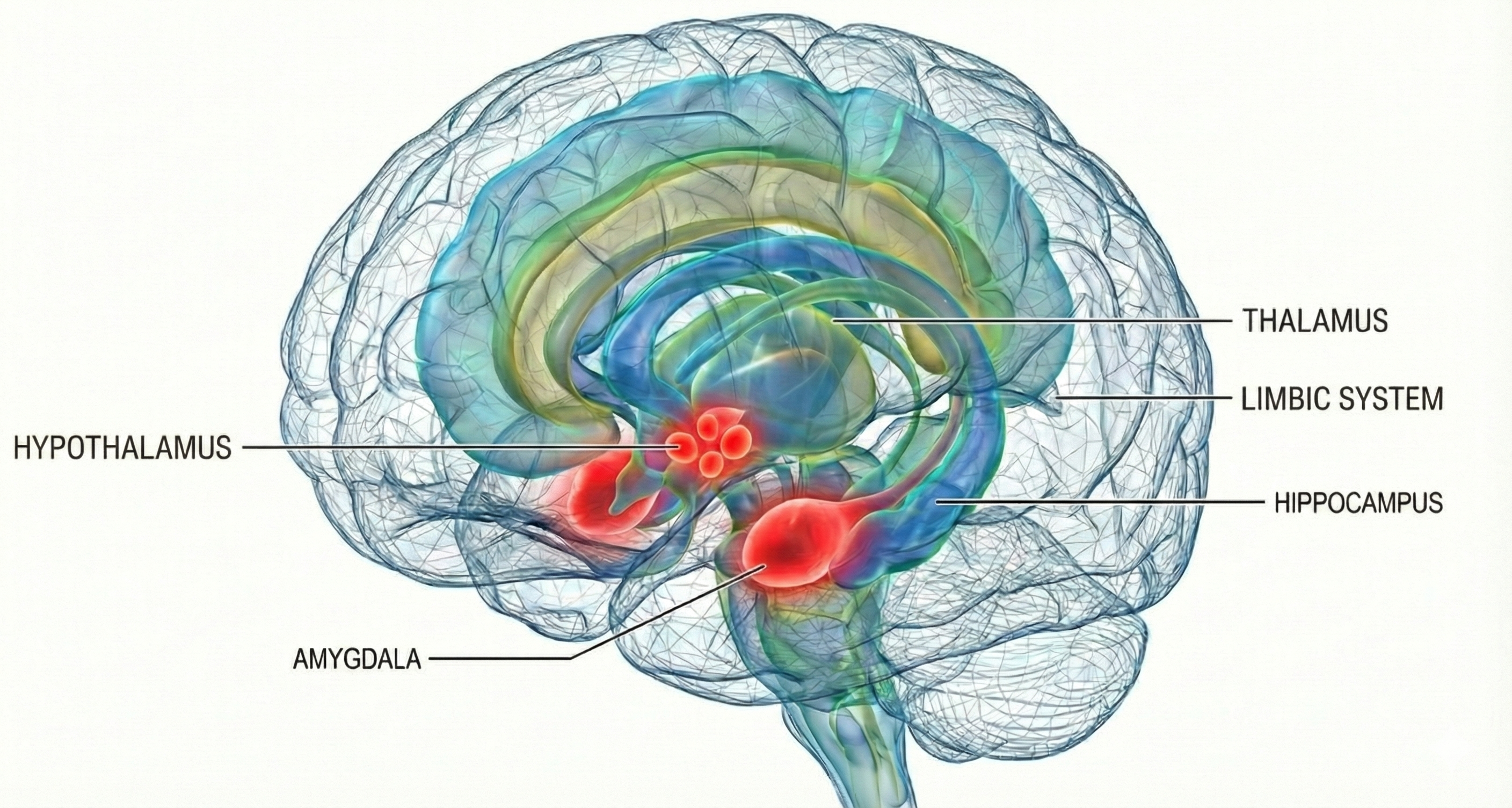

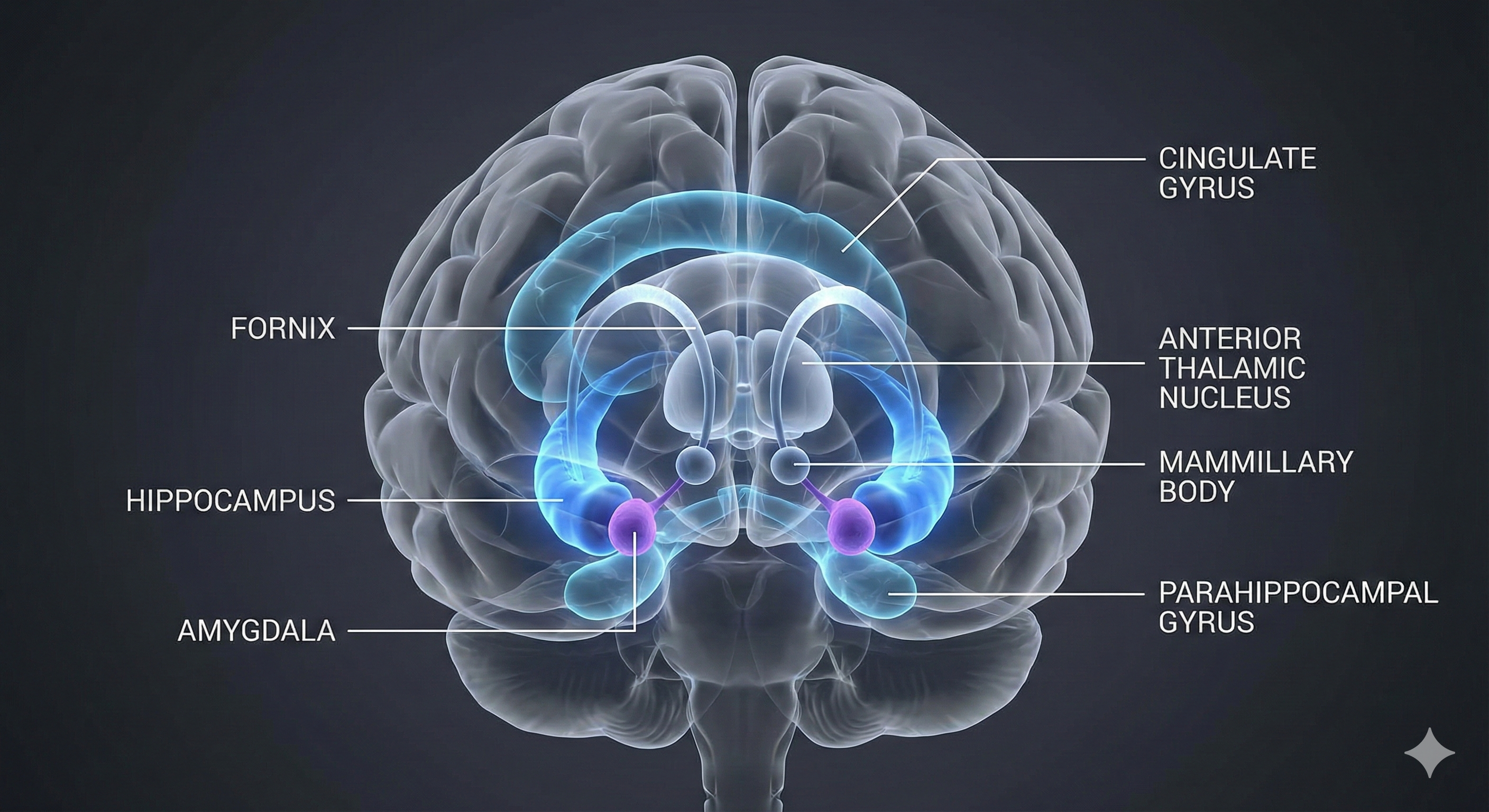

Brain Structures Involved in Stress

The four brain structures most important to the stress response are the amygdala, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex.

The amygdala is part of the limbic system and evaluates whether stimuli are threatening, establishing unconscious emotional memories, learning conditioned emotional responses, and producing anxiety and fear responses.

The hypothalamus lies beneath the thalamus in the forebrain. It helps the body maintain a dynamic homeostatic balance by controlling the autonomic nervous system, endocrine system, survival behaviors (four F's), and interconnections with the immune system.

The Hypothalamus Receives Information About Stressors

Much of the information about stressors is relayed to the PVN. This hypothalamic nucleus organizes behavior to respond to changes in internal body states. The PVN receives input from the limbic system, cerebral cortex, hypothalamus, and brainstem structures (nucleus of the solitary tract, tegmentum and reticular formation, periaqueductal gray, locus coeruleus, and raphe system).

When the PVN is excited, it releases several chemical substances, including CRH, oxytocin, arginine-vasopressin, thyrotropin-releasing hormone, growth hormone-releasing hormone, somatostatin, dopamine, enkephalin, cholecystokinin, and angiotensin.

This large variety of hormones enables the individual to respond to a wide range of stressors. Since stressful events may simultaneously present many stressors, these chemical substances allow the individual to respond completely and appropriately.

The hippocampus is part of the medial temporal lobe memory system and helps form declarative memories, allows us to navigate our environment, and prevents excessive hypothalamic CRH release.

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is the most anterior region of the frontal lobes. The PFC contains the orbitofrontal and ventromedial, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and anterior and ventral cingulate cortex. The PFC is responsible for the brain's executive functions, including planning, guiding decisions using emotional intelligence, working memory, allocation of attention, and emotional experience. The PFC inhibits emotional behavior triggered by the amygdala.

Acute stress activates the fight-or-flight response via the SAM pathway, releasing epinephrine and norepinephrine. Chronic stress activates the HPA axis, releasing CRH, ACTH, and cortisol. Cortisol has widespread effects on the body and brain, including impaired immune function, hippocampal damage, and disrupted executive function. The General Adaptation Syndrome describes three stages of stress response: alarm, resistance, and exhaustion. Men and women show different stress responses, with women more likely to show tend-and-befriend patterns mediated by oxytocin.

Check Your Understanding

- What are the key differences between the SAM pathway and the HPA axis?

- How does chronic cortisol elevation affect the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex?

- What are the three stages of Selye's General Adaptation Syndrome?

- How does the tend-and-befriend response differ from the fight-or-flight response?

- What are the main criticisms of Selye's General Adaptation Syndrome?

Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI)

Nonspecific and Specific Immune Mechanisms

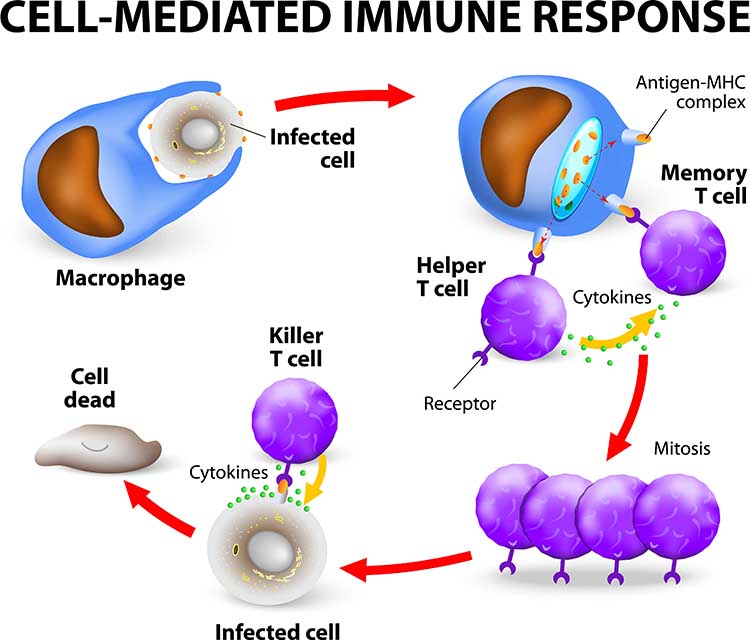

The human body utilizes nonspecific and specific immune mechanisms to protect itself against invading organisms, damaged cells, and cancer.

The main nonspecific, or innate, mechanisms are relatively rapid in response and include anatomical barriers (skin and mucous membranes) and phagocytosis (ingestion of microorganisms) by macrophages and neutrophils. Natural killer cells and neutrophils destroy infectious agents. Nonspecific mechanisms release antimicrobial agents (hydrochloric acid, interferons, and lysozymes) and signal to other immune responders. Local inflammatory responses confine microbes, allowing white blood cells and other immune cells to attack them.

Check out Professor Gillian Griffiths' video Killer T Cell: The Cancer Assassin.

The Immune System Is Interconnected with the Nervous System

The classical model of the immune system is that it operates independently of the nervous system and psychological processes. However, researchers have demonstrated complex interactions among the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems, consistent with Green and Green's psychophysiological principle. Psychological processes like expectancies (placebo effect) and learning (classical conditioning) can affect all three systems, and the immune system can affect psychological functioning (drowsiness from a fever).

Psychoneuroimmunology is a multidisciplinary field that studies the interactions between behavior and these three systems.

After Solomon and Moos (1964) introduced the term psychoneuroimmunology in a journal article, Ader and Cohen's (1975) demonstration of classical conditioning in a rat's immune system helped establish this field's scientific legitimacy.

Ader and Cohen trained rats to associate a conditioned stimulus (a saccharine and water solution) with an unconditioned stimulus (the immunosuppressive drug cyclophosphamide). This resulted in a conditioned response (CR) of immune suppression, which resulted in rat fatalities. Following conditioning, rats who drank only sweetened water (CS) died due to conditioned immunosuppression. Successful replication of these findings helped overcome resistance to the controversial view that the nervous and immune systems interact.

The mechanisms underlying these complex interactions include HPA axis hormones (ACTH, cortisol, CRH, epinephrine, and norepinephrine), immune cell chemical messengers called cytokines (interleukins), additional hormones (androgens, estrogens, progesterone, and growth hormone), and neuropeptides. Neuropeptides are chains of amino acids, like beta-endorphins, that neurons use for communication.

Stress and Immunity

There is persuasive evidence that stressful life events can reduce immunity and that behavioral interventions can enhance or maintain it. Bereavement can reduce lymphocyte (lymphatic white blood cell) proliferation (Schleifer et al., 1983). Academic exams, marital conflict, negative affect associated with stress, clinical and subclinical depression, and negative daily mood can suppress immunity (Herbert & Cohen, 1993; Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2002; Stone et al., 1994).

The stress of living near the Three Mile Island nuclear plant when it experienced a significant accident reduced residents' B cell, T cell, and natural killer cell counts compared with control subjects (McKinnon et al., 1989).

A study of Alzheimer's caregivers showed lowered immunity and longer wound healing times, and worse psychological and physical health than controls who were not caregivers (Kiecolt-Glaser, 1999). The Alzheimer's patients' deaths did not improve caregiver immunity or psychological functioning (Robinson-Whelen et al., 2001).

Finally, laboratory stressors produced more significant discomfort and immunosuppression in chronically-stressed young males than in those not chronically stressed (Pike et al., 1994). Exposure to chronic stress may have intensified their subjects' response to acute laboratory stressors.

Behavioral Interventions Can Strengthen Immunity

Behavioral interventions can increase immunocompetence. Miller and Cohen's (2001) meta-analytical study of behavioral interventions showed modest increases in immunity. Hypnosis increased immune function more than relaxation and stress management.

A stress management program incorporating relaxation training reduced symptoms and increased salivary antibodies and psychological functioning in children diagnosed with frequent upper respiratory infections (Hewson-Bower & Drummond, 2001).

College students who wrote journal entries about highly stressful experiences increased lymphocyte proliferation and made fewer health center visits (Pennebaker et al., 1988). Smyth et al. (1999) asked asthma and rheumatoid arthritis patients to write journal entries about highly stressful experiences or planned daily activities. At a 4-month follow-up, 50% of the Pennebaker journal group who wrote about stressful experiences and 25% of the control group achieved clinically significant improvement in their immune-related disorders (Crider, 2004).

Dental and medical students who received hypnosis training maintained immune function, while a control group showed declines in immunity (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2001). This finding suggests that behavioral interventions may be more effective in maintaining normal immunity than boosting immunity (Brannon et al., 2022).

Psychoneuroimmunology studies the interactions between behavior and the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems. Research demonstrates that stress can suppress immune function, while behavioral interventions like relaxation training, expressive writing, and hypnosis can help maintain or enhance immunity. The immune system is not independent but closely connected to psychological and neural processes.

Cognitive Appraisal of Stressors and Coping

Lazarus and Folkman's (1984) Transactional Model of Stress has more strongly influenced psychologists than Selye's General Adaptation Syndrome.

Whereas Selye's stimulus model theorized that events determine stress, Lazarus' cognitive model proposed that stress is determined by our perception of the situation and emphasizes person-environment fit (Taylor, 2012).

Coping is central to the Transactional Model of Stress. Lazarus and Folkman defined it as "constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person" (1984, p. 141). Coping is an effortful learned process whose goal is to manage a situation (Brannon et al., 2022).

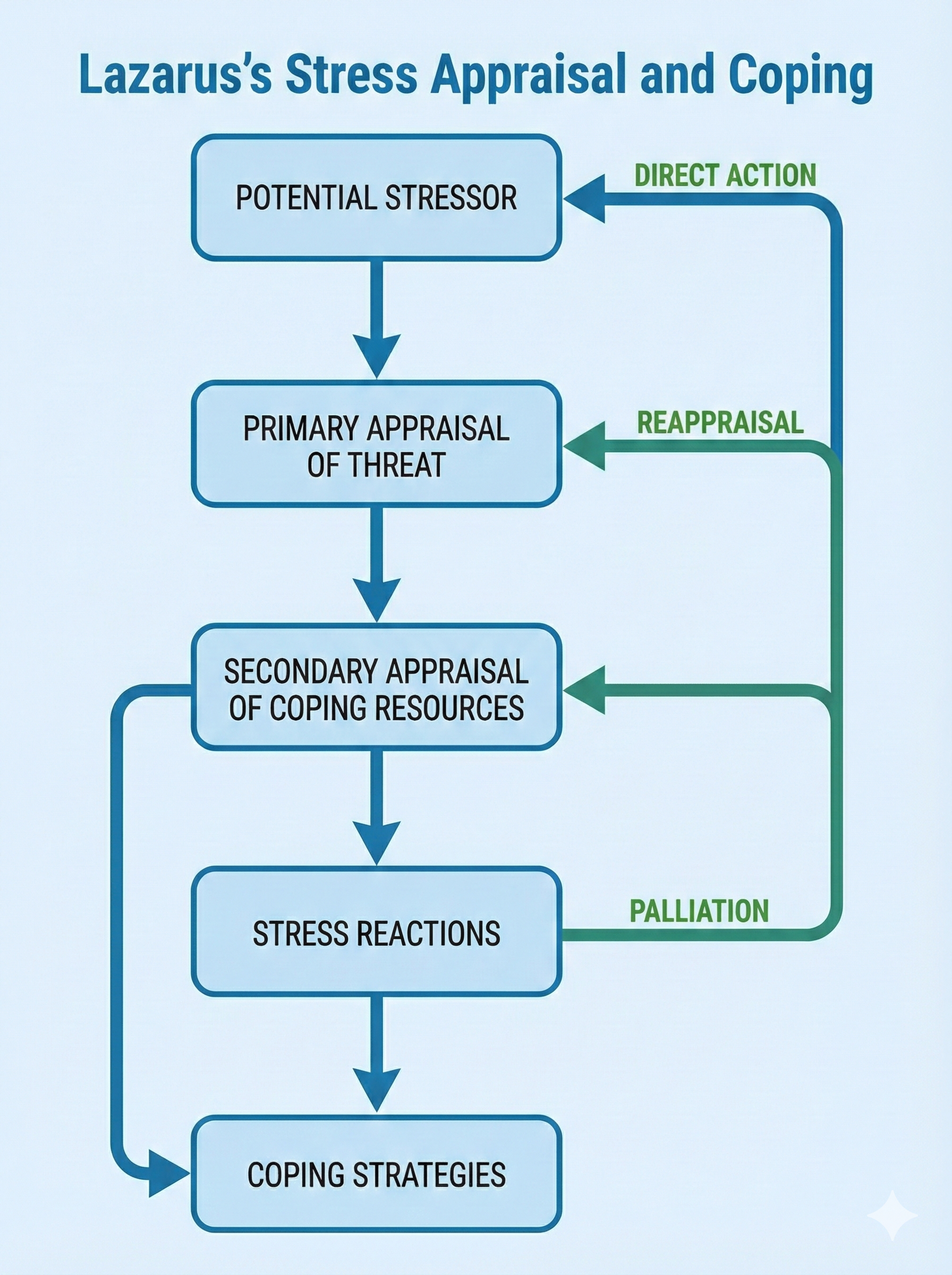

🎧 Listen to a mini-lecture on the Transactional Model of StressIn primary appraisal, we categorize the consequences of events as positive, neutral, or negative and determine whether an event is relevant, negative, or potentially negative. We evaluate these events for their possible harm, threat, or challenge.

Harm is damage that has already occurred. For example, a person who experiences a heart attack may perceive harm as damage to the heart muscle. Threat means damage that could arise in the future. The heart attack survivor may anticipate restricted physical activity and reduced income. The perception of an event as a threat has physiological consequences and can result in elevated blood pressure. Challenge is the potential to cope with the event and gain from this opportunity. The heart attack survivor may reframe this health crisis as an opportunity to make a career change. The perception of an event as a challenge can increase perceived self-efficacy and positive emotion while lowering blood pressure (Maier et al., 2003).

The Chinese pictogram wei ji (pronounced way jee), representing danger and opportunity, illustrates the negative and positive possibilities considered during primary appraisal.

During secondary appraisal, we evaluate whether our coping abilities and resources can surmount an event's harm, threat, or challenge. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) listed health and energy, positive belief, problem-solving skills, social skills, social support, and material resources as necessary coping resources. Again, perception of our coping abilities and resources is more important than their actual existence.

The balance between primary and secondary appraisal determines how we subjectively experience the event. We experience the most stress when perceived harm or threat is high and perceived coping skills and resources are low. Stress is reduced when we perceive that our coping abilities and resources are high (Taylor, 2012).

Secondary appraisal can lead to our use of direct action, reappraisal, and palliation.

Direct action can take different forms depending on the nature of the threat. We may use aggression and escape behaviors from Cannon's fight-or-flight response for violent threats to our survival. We may use problem-solving for medical or psychological threats, define the problem, identify options, and test these options until we succeed. A cardiac patient may enroll in a cardiac rehabilitation program to increase exercise tolerance and reduce the risk of artery narrowing.

Reappraisal may reduce stress when direct action is impractical or unsuccessful. Reappraisal modifies our perception of a threat. When overwhelmed by traumatic stress, individuals may initially use ineffective strategies like denial and rationalization. As they cope with the crisis, they may progress with more successful strategies like reframing in which they place the stressful situation in perspective and focus on available opportunities. For example, a cardiac patient may decide that his heart attack allowed him to spend more time with his grandchildren.

Palliation consists of efforts to reduce our stress response rather than attack the stressor. Clinicians may use biofeedback and adjunctive techniques like effortless breathing to teach cardiac patients to control their anxiety. While this does not correct the cause of the stress response, it is often superior to medications like anxiolytics that risk side effects, tolerance, physical dependence, and withdrawal effects. Successful clinical interventions for chronic problems like anxiety, depression, and pain incorporate effective palliation since complete remission may be unlikely.

Evaluating the Transactional Model

The Transactional Model of Stress encompasses cognitive appraisal, missing from the General Adaptation Syndrome. Research supports this model. For example, performance is better when we perceive an event as challenging instead of threatening (Moore et al., 2012).

Lazarus and Folkman's model recognizes that we constantly change as we cope with stressors and that our coping successes and failures influence our appraisals of future events (Brannon et al., 2022).

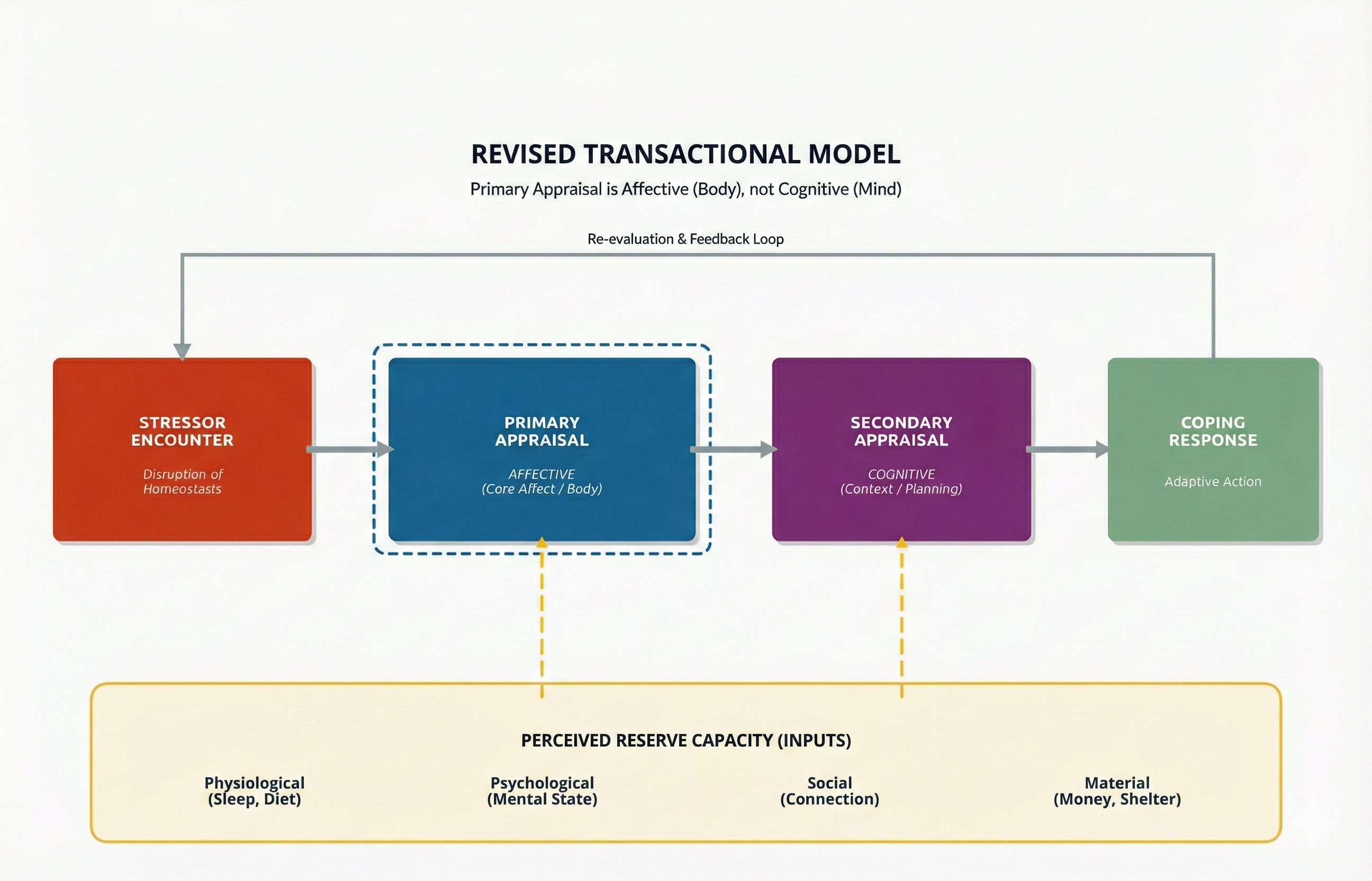

Primary Appraisal Is Affective, Not Cognitive

Steffen and Anderson (2025) proposed a significant revision to the Transactional Model based on current neuroscience research. Their central argument challenges a long-held assumption: primary appraisal is not primarily a cognitive process but an affective one. When you encounter a potential stressor, your body does not wait for your thinking brain to analyze the situation before responding. Instead, your affective primary appraisal, which is the initial emotional and bodily response that occurs before conscious thought, kicks in first. This gut-level reaction, which researchers call core affect, represents how your body continuously evaluates its relationship to the environment over time. Think of core affect as your internal compass that constantly registers whether things feel good, bad, or neutral, long before you consciously think about them. This body-based knowing forms the foundation for all emotional experience and conscious awareness.

The idea that cognition and emotion operate as separate systems, which traces back to philosophers like Plato and Descartes, turns out to be neurobiologically incorrect. Brain imaging studies confirm that there are no purely emotional or purely cognitive circuits in the brain; instead, these processes are anatomically and functionally intertwined (Steffen & Anderson, 2025).

This revised model has important implications for how clinicians help people manage stress. If the body's affective response comes first and cognition follows, then therapeutic approaches that start by trying to change thoughts may be working backward.