History of Biofeedback

What You Will Learn in This Chapter

Have you ever wondered how biofeedback transformed from an obscure laboratory curiosity into a recognized clinical intervention? The story is more fascinating than you might expect. It involves ancient yogis demonstrating impossible feats, paralyzed rats learning to control their heart rates, and a group of researchers at a California beach hotel coining a term that would reshape our understanding of mind-body medicine.

In this chapter, you will discover the early antecedents of biofeedback, from 5,000-year-old yoga practices to 19th-century physiologists who laid the groundwork for modern self-regulation. You will learn about cybernetic theory and how it provided the conceptual framework that defines biofeedback today. You will explore the operant conditioning research that gave biofeedback scientific credibility, and you will meet the pioneers who developed applications across diverse domains: incontinence, brain waves, electrodermal activity, muscle function, cardiovascular regulation, and pain management.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage: This unit addresses the History of biofeedback (I-B).

🎧 Listen to the Chapter Lecture

History depends on who writes it and who survives it. It is shaped by those who promote it and those who contribute to it. The official history of American biofeedback started in 1969 at the Surf Rider Inn in Santa Monica, California. Barbara Brown, a Veterans Administration (VA) electroencephalography (EEG) researcher, organized this meeting and placed her feisty stamp on the field. Here, the separate threads of scientific research into the possibility of autoregulation and the autoregulation practices of millennia-old meditative techniques coalesced. (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 142)

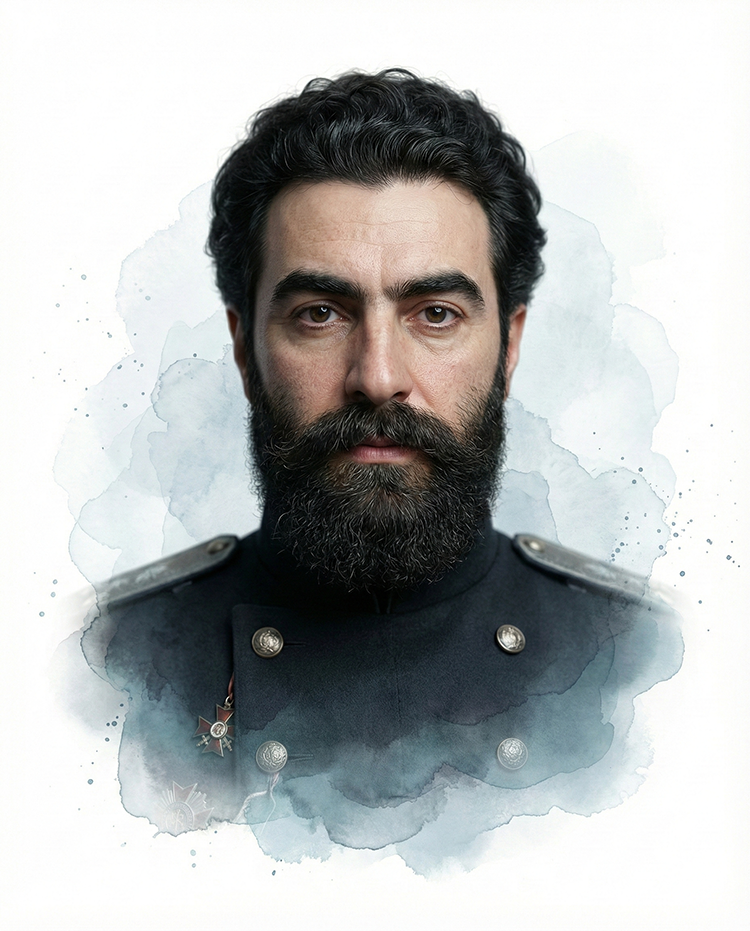

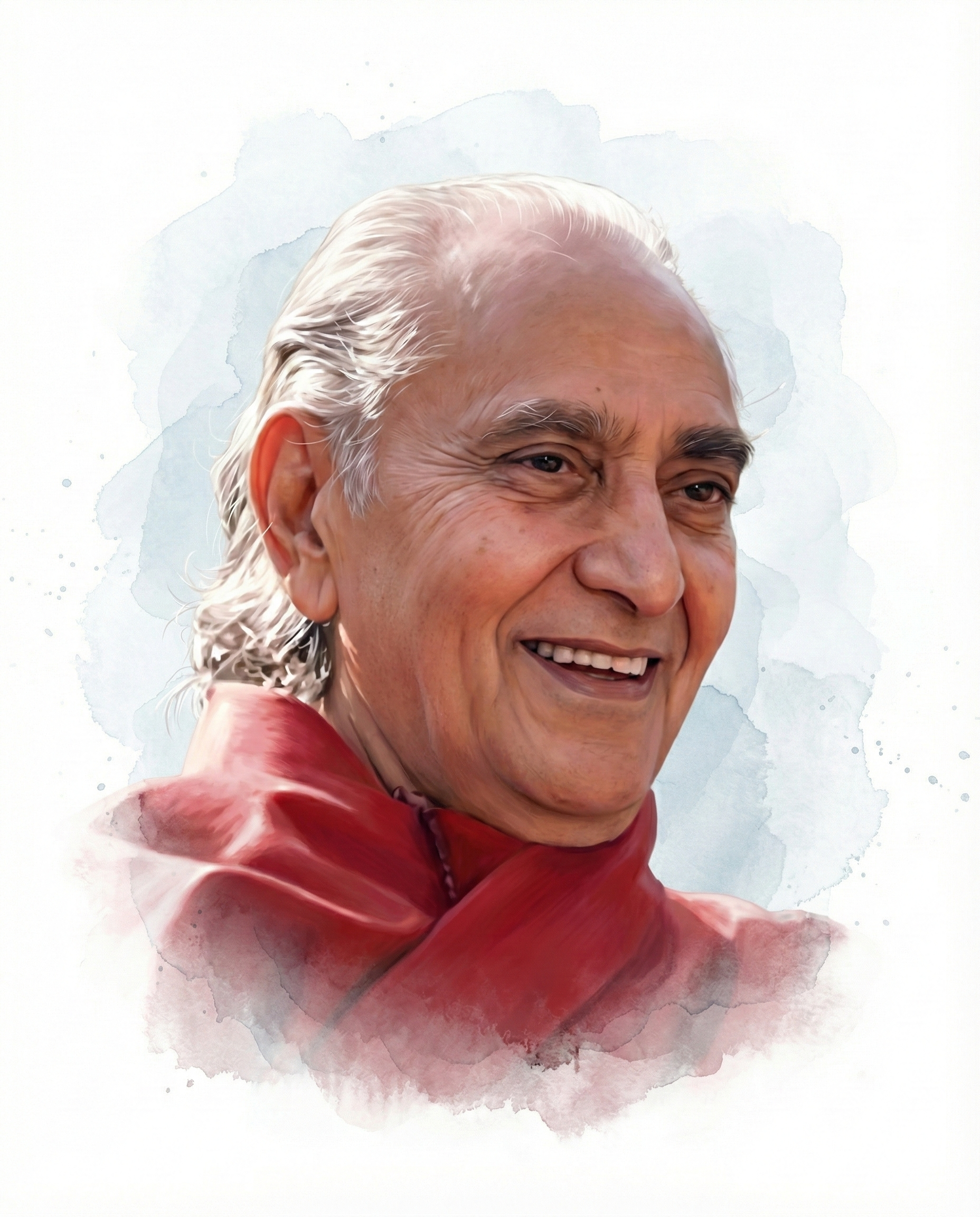

When we examine biofeedback history, Erik Peper has played an indispensable role in connecting, teaching, and collaborating with countless leaders in our field. Erik has generously mentored colleagues who have become our leading educators and researchers. An indefatigable traveler, he has promoted biofeedback internationally in countries like Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, and Taiwan through his popular lectures and the Biofeedback Federation of Europe.

Early Antecedents: Ancient Wisdom Meets Scientific Curiosity

The concept of self-regulation (voluntary control of biological processes) is ancient, despite our recent rediscovery of it. Consider this: Hindus practiced systems of yoga almost 5,000 years ago in India. While Western scientists were still debating whether humans could influence their own physiology, Eastern practitioners were already exploring the mind-body connection through systematic techniques. Watch A Brief History of Yoga to explore these roots.

Before the term biofeedback was popularized in 1969, contributors repeatedly demonstrated this learning process without understanding its implications and broader application.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Early Antecedents

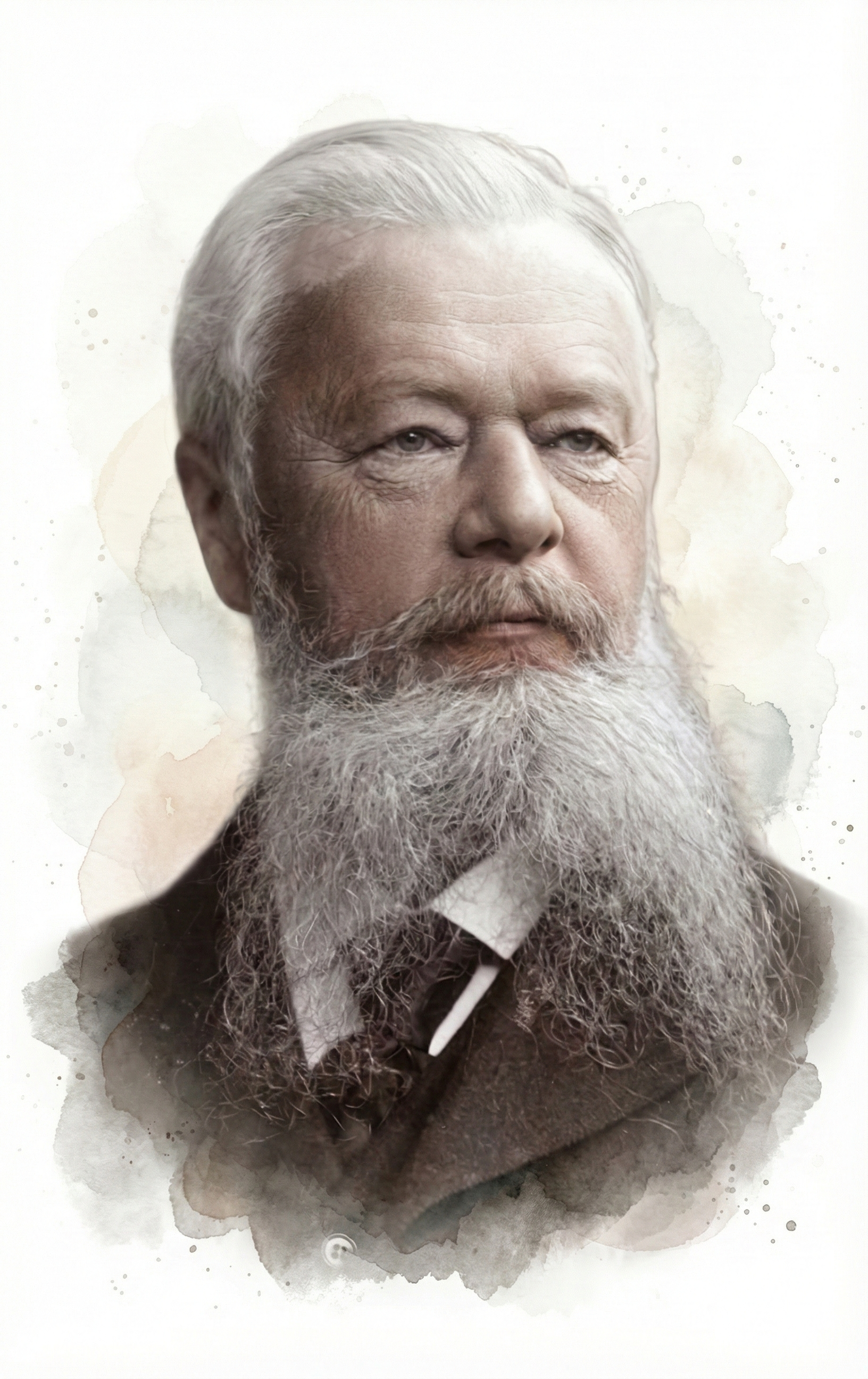

Claude Bernard (1813–1878) , the French physiologist, introduced the concept of the "milieu intérieur," proposing that organisms actively maintain stable internal conditions despite external changes. This concept anticipated homeostasis and provided a theoretical foundation for understanding why physiological self-regulation is both possible and adaptive. Bernard's work established that physiological systems possess inherent regulatory mechanisms that can be enhanced through feedback.

Walter Bradford Cannon (1871–1945) the American physiologist, coined the term homeostasis to describe the body's tendency to maintain stable internal states. His research on the sympathetic nervous system and the "fight-or-flight" response demonstrated how the autonomic nervous system regulates physiological responses to stress. Cannon's demonstration that emotional states produce measurable physiological changes validated the psychophysiological approach central to biofeedback practice. Cannon gave us the vocabulary we still use today when we talk about how our bodies respond to challenge.

Janos Hugo Bruno "Hans" Selye (1907–1982) , an Austro-Hungarian-Canadian endocrinologist, developed the General Adaptation Syndrome theory of stress, describing how prolonged stress leads to exhaustion and disease. His research demonstrated the physiological consequences of chronic stress and the importance of adaptive responses. Selye's work provided the medical rationale for stress management interventions, including biofeedback-assisted relaxation training. His work demonstrated that stress is not just a psychological experience; it produces measurable physiological changes throughout the body.

Bell, Tarchanoff, and Bair pioneered the contemporary study of self-regulation. Their work demonstrated that humans could learn to control physiological processes that most scientists believed were completely automatic.

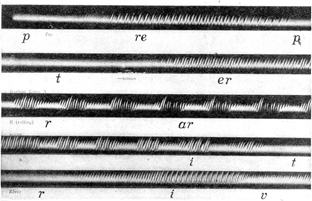

Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922) studied teaching the deaf to speak using biofeedback. Yes, the inventor of the telephone was also an early biofeedback pioneer! He investigated Leon Scott's phonautograph, which translated sound vibrations into tracings on smoked glass to show their acoustic waveforms. Bell made early contributions to technology for amplifying and transmitting physiological signals. His work on auditory devices and electrical transmission influenced instrument development for detecting and displaying biological signals.

Bell also examined Koenig's manometric flame, which displayed sounds as patterns of light. The photographs below are from R. Victor Jones (Bruce, 1973).

Ivan Tarchanoff (1846–1908) a Russian physiologist, independently discovered the endosomatic measurement of electrodermal activity, observing that the skin generates electrical potentials varying with emotional states. His parallel discovery to Féré's work established electrodermal measurement as a reliable psychophysiological method. The techniques developed by Féré and Tarkhanov evolved into modern skin conductance measurement used in biofeedback. Tarchanoff also showed that voluntary control of heart rate could be fairly direct (cortical-autonomic) and did not depend on "cheating" by altering breathing rate. This was a crucial finding because it suggested the brain could directly influence heart function.

J. H. Bair (1901) studied voluntary control of the retrahens muscle that wiggles the ear. He found that participants learned this skill by inhibiting interfering muscles. This was a solid demonstration of skeletal muscle self-regulation. If you have ever tried to wiggle your ears, you have attempted what Bair's participants learned to do systematically.

Key Takeaways: Early Antecedents

Self-regulation has ancient roots in Eastern practices like yoga. Bernard introduced the concept of internal stability, Cannon coined "homeostasis," and Selye established our modern understanding of stress. Early pioneers like Bell used visual feedback for speech training, while Tarchanoff and Bair demonstrated that both autonomic and skeletal muscle responses could be voluntarily controlled.

Clinical Application: Ancient Wisdom

Imagine you are explaining biofeedback to a skeptical client named Marcus who thinks the whole concept sounds too "new age." You can tell him that the principles underlying biofeedback are older than Western medicine itself. Yogis demonstrated voluntary control of heart rate and body temperature thousands of years ago. Alexander Graham Bell used visual feedback to teach deaf individuals to speak. The technology is new; the underlying human capacity for self-regulation is ancient.

Cybernetic Theory: The Conceptual Foundation

Norbert Wiener (1894–1964), an American mathematician at MIT, founded the field of cybernetics and developed the concept of feedback that gave biofeedback its name. His 1948 book Cybernetics: Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine established the theoretical framework for understanding self-regulating systems. Wiener's insight that feedback loops enable system self-regulation provided the conceptual foundation for biofeedback interventions.

Cybernetic theory contributed several key concepts. The system variable is what is controlled; in thermal biofeedback, this is finger temperature. The setpoint is the goal; for hand-warming training, you might aim for 95°F. Feedback refers to corrective instructions based on current performance; the visual or auditory display tells your client whether they are getting closer to or further from their goal. Feedforward involves instructions based on anticipated conditions; when your client learns to recognize early stress signals, they can initiate relaxation before tension builds.

The participants at the landmark 1969 conference at the Surfrider Inn in Santa Monica coined the term biofeedback from Wiener's feedback concept (Moss, 1998).

This group needed a name, and the two candidates were biofeedback and autoregulation. Just before the final vote, someone in the audience yelled out that autoregulation sounded like government control of cars. This spontaneous comment created a tipping point, the consensus shifted to biofeedback, and the Biofeedback Research Society (BRS) was born. (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 142)

Key Takeaways: Cybernetic Theory

Cybernetic theory provides the conceptual foundation for biofeedback. Systems are controlled by monitoring their results and making adjustments. Key concepts include system variable (what is measured), setpoint (the goal), feedback (information about current performance), and feedforward (anticipatory adjustments). The term "biofeedback" was coined at the 1969 founding conference of the Biofeedback Research Society.

Operant Conditioning: How Learning Shapes Physiology

Edward Lee Thorndike (1874–1949), an American psychologist, formulated the Law of Effect in 1898, stating that responses followed by satisfying consequences are strengthened. This principle became the theoretical foundation for operant conditioning and biofeedback. Thorndike's research on trial-and-error learning in animals established that behavior could be shaped by its consequences.

Burrhus Frederic Skinner's (1904–1990), an American psychologist at Harvard, developed the theory and methodology of operant conditioning that underlies biofeedback. His research demonstrated that behavior could be shaped through systematic reinforcement, establishing principles that would later be applied to physiological responses. Skinner's work provided the learning theory framework that biofeedback pioneers used to demonstrate voluntary control of autonomic functions.

Skinner introduced several concepts that have influenced biofeedback theory. Reinforcement is a process where the consequence of a voluntary response increases the likelihood it will be repeated. Results that strengthen responses are called reinforcers. Consider how the pleasant tone in thermal biofeedback reinforces hand-warming: your client hears the tone indicating success, and this reinforces whatever physiological strategy they were using.

Punishment is a process that actively suppresses responses. The consequence of a voluntary response decreases the likelihood that it will be repeated. Outcomes that weaken responses are called punishers. In biofeedback, we generally emphasize reinforcement rather than punishment, but understanding both concepts helps you design effective training protocols.

Based on Skinner's work, researchers used operant theory to divide physiological responses into those that could be voluntarily controlled and those that could not. Here is where biofeedback challenged the scientific establishment.

From its inception, biofeedback had to overcome the entrenched paradigm that individuals could not voluntarily control autonomic functions. Researchers who applied B. F. Skinner's work to biofeedback used operant theory to determine which responses could be voluntarily controlled and which could not. For example, Kimble (1961) argued that although participants could learn to consciously control skeletal muscle responses, autonomic processes (such as heart rate) were involuntary, could be only classically conditioned, and were forever outside of conscious control. This perspective ignored the almost 3,000-year-old yogic practice of autonomic control and research by Lisina (1958); Lapides, Sweet, and Lewis (1957); and Kimmel (1967) that demonstrated voluntary control of autonomic responses. (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 143)

Key Takeaways: Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning provides the learning theory that explains how biofeedback works. Thorndike's Law of Effect and Skinner's research demonstrated that behaviors followed by positive consequences are more likely to be repeated. In biofeedback, visual or auditory feedback serves as a reinforcer that strengthens the physiological responses associated with it. Initially, many researchers believed autonomic functions could not be voluntarily controlled, but subsequent research proved them wrong.

Studies Demonstrating Voluntary Autonomic Control: Challenging the Dogma

The belief that only skeletal muscles could be voluntarily controlled ignored Indian yogis' practice of autonomic control for over 5,000 years. It also ignored research by Lapides, Sweet, and Lewis; Lisina; Kimmel; and Miller and DiCara that demonstrated voluntary control of autonomic responses. Here is a sobering thought: an entire scientific establishment dismissed thousands of years of yogic practice because it did not fit their theoretical framework. Ironically, Skinner observed in 1938 that performers could learn to cry (an autonomic response) on cue.

J. Lapides, R. B. Sweet, and L. W. Lewis (1957) temporarily paralyzed male participants and trained them to stop urination twice as fast as normal using only (autonomically-controlled) smooth muscle.

Jack Lapides, a urologist at the University of Michigan, along with colleagues Robert B. Sweet and Louis W. Lewis, published foundational research in 1957 demonstrating the role of striated (voluntary) muscle in urination control, establishing the physiological basis for what would later become biofeedback treatment of urinary incontinence.

Their Journal of Urology paper showed that the external urethral sphincter, composed of striated muscle under voluntary control, plays a critical role in maintaining continence and initiating voiding, a finding that implied patients could learn to consciously regulate these functions. This work provided the scientific rationale for subsequent biofeedback applications in which patients learn to strengthen and coordinate pelvic floor muscles using EMG feedback to treat stress and urge incontinence.

Lapides continued his pioneering work in neurourology, later revolutionizing the management of neurogenic bladder by introducing clean intermittent self-catheterization in 1972, which challenged prevailing sterile technique dogma and became the gold standard treatment worldwide (Lapides, Sweet, & Lewis, 1957; Lapides et al., 1972).

M. I. Lisina (1965), a Russian researcher, conducted early studies demonstrating that humans could learn to control vasomotor responses through feedback. Her work, conducted independently of Western researchers, contributed to establishing that peripheral vascular responses could be voluntarily modified, anticipating thermal biofeedback applications. Lisina combined classical and operant conditioning to train participants to change blood vessel diameter. She elicited reflexive blood flow changes and then displayed the changes in their blood flow to teach them voluntary temperature control.

H. D. Kimmel (1974) operantly trained participants to sweat (measured by the galvanic skin response).

Scientific paradigms function like filters that determine which hypotheses should be investigated. When Neal Miller tried to encourage graduate students to train rats to achieve autonomic control through instrumental learning, all but one balked. Why investigate a phenomenon that could not possibly exist? (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 143)

Neal Elgar Miller (1909–2002), an American psychologist at Yale and Rockefeller University, and Leo V. DiCara (1937-1974), his key collaborator at Rockefeller University, operantly conditioned heart rate, blood pressure, kidney blood flow, skin blood flow, and intestinal contraction in paralyzed and unparalyzed rats. Curare was used to paralyze rats to prevent cheating by changing their breathing pattern. The reinforcer was electrical stimulation to the medial forebrain bundle. DiCara's contributions were essential to establishing the experimental basis for visceral learning.

Their demonstration that both paralyzed and unparalyzed rats could learn to produce these autonomic changes gave biofeedback scientific credibility and led to National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) funding for biofeedback research.

Miller's landmark 1969 Science article announced that visceral learning was possible. Though some findings proved difficult to replicate, Miller's work legitimized scientific investigation of voluntary control over physiological processes and inspired the biofeedback movement (Miller, 1969).

Miller and graduate student Leo DiCara conducted the landmark study that demonstrated that curarized rats could operantly learn to control their autonomic functions. Their 1968 publication, "Instrumental Learning of Vasomotor Responses by Rats: Learning to Respond Differentially in the Two Ears," in the influential journal Science challenged the dogma that autonomic processes cannot be voluntarily controlled (DiCara & Miller, 1968). Their evidence was compelling. Paralyzed rats couldn't "cheat" by altering their breathing pattern or muscle tone. Their research was a crucial thread in our tapestry because it challenged researchers to investigate which other physiological processes could be voluntarily controlled and secured prestigious National Institute of Mental Health funding, which helped to establish the scientific legitimacy of biofeedback (Miller, 1969, 1978; Miller & DiCara, 1967; Miller & Dworkin, 1974). (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 143)

Controversy clouded the paralyzed rat studies. While the unparalyzed rat findings have held up, attempts to replicate (reproduce) the curare findings have yielded smaller but dependable heart rate changes (Hothersall & Brener, 1969; Slaughter et al., 1970; Trowill, 1967). Taub (2010) provides an authoritative history of Miller and DiCara's research.

Miller and Bernard Brucker (1946-2008) developed EMG biofeedback protocols for spinal cord injury rehabilitation at the University of Miami. Brucker investigated whether quadriplegic patients, who have limited voluntary skeletal muscle activity, could achieve autonomic change without somatic mediation. His research demonstrated that patients with incomplete spinal cord injuries could achieve significant motor recovery through intensive EMG biofeedback training. Brucker's work established biofeedback as a valuable component of neurological rehabilitation programs.

These paralyzed patients, who experience low blood pressure when lying in bed, learned to produce large-scale blood pressure increases without using their skeletal muscles.

Key Takeaways: Autonomic Control

Research by Miller, DiCara, and others challenged the prevailing belief that autonomic functions could not be voluntarily controlled. The curarized rat studies were particularly important because they eliminated the possibility that subjects were "cheating" by manipulating breathing or muscle tension. Although replication of the curare studies yielded smaller effects, the core finding that autonomic processes can be operantly conditioned has been supported. Research with quadriplegic patients provided additional evidence that autonomic control can occur independently of skeletal muscle activity.

Clinical Application: Autonomic Training

Consider Jane, a new client who doubts that she can learn to control her heart rate variability. She tells you that heart function is "automatic" and cannot be changed by willpower. You can share the story of Miller and DiCara's research, explaining that even paralyzed rats learned to control their heart rates when given feedback. You can also mention the quadriplegic patients who learned to raise their blood pressure without using any skeletal muscles. These examples often help skeptical clients understand that the autonomic nervous system is more trainable than they believed.

Check Your Understanding: Foundations of Biofeedback

- How did yogic practices foreshadow modern biofeedback by thousands of years?

- Explain how a home thermostat illustrates the key concepts of cybernetic theory (system variable, setpoint, feedback, and feedforward).

- Why was Skinner's concept of reinforcement important for understanding how biofeedback works?

- What did Miller and DiCara's curarized rat studies demonstrate, and why was the use of curare important?

- How did the research with quadriplegic patients strengthen the case for voluntary autonomic control?

Divergent Movements in Biofeedback: Specialized Applications Emerge

Biofeedback researchers have studied autonomic responses, incontinence, the brain, electrodermal system, skeletal muscle system, cardiovascular system, and pain. We will successively review significant contributions in each of these areas. Remember that contributors from different disciplines (like rehabilitative medicine and animal learning) worked in relative isolation in biofeedback's infancy. The founding of the Bio-Feedback Research Society in 1969 provided a forum for interdisciplinary exchange. Let us be honest: the field of biofeedback could not have developed without this coming together of minds from many different backgrounds.

Incontinence: An Early Biofeedback Success Story

Orval Hobart Mowrer (1907–1982), an American psychologist, developed a two-factor theory of learning combining classical and operant conditioning. His work on avoidance learning and anxiety influenced understanding of how physiological responses could be modified through behavioral techniques. Mowrer also invented a conditioning-based treatment for bedwetting that anticipated biofeedback applications for incontinence.

This simple biofeedback device can quickly teach children to wake up when their bladders are full, contract the urinary sphincter, and relax the detrusor muscle, preventing further urine release. Through classical conditioning, sensory feedback from a full bladder replaces the alarm and allows children to sleep without urinating. Consider how elegant this solution is: a simple device that has helped countless children overcome a distressing problem.

Arnold Henry Kegel (1894–1981), an American gynecologist, developed the perineometer in 1948, creating the first biofeedback device for pelvic floor muscle training. The perineometer, inserted into the vagina to monitor pelvic floor muscle contraction, satisfies all the requirements of a biofeedback device and enhances the effectiveness of popular Kegel exercises (Perry & Talcott, 1989). His research demonstrated that women with urinary incontinence could strengthen pelvic floor muscles through exercise with biofeedback guidance. The Kegel exercises he developed remain a standard treatment for stress incontinence.

In 1992, the United States Agency for Health Care Policy and Research recommended biofeedback as a first-line treatment for adult urinary incontinence (Whitehead, 1995).

William E. Whitehead (1996) contributed significantly to biofeedback treatment for fecal incontinence and other gastrointestinal disorders. His research demonstrated that biofeedback could improve rectal sensation and sphincter coordination. Whitehead's work established biofeedback as an effective treatment for anorectal disorders.

Brain Research: From Galvani to Modern Neurofeedback

Many researchers laid the foundation for landmark contributions of Hans Berger and modern contributors like Joe Kamiya, M. Barry Sterman, and Joel Lubar.

Luigi Galvani (1737–1798), an Italian physician and physicist at the University of Bologna, discovered what he termed "animal electricity" in the 1780s. He observed that dissected frog legs twitched when touched by metal instruments during electrical storms. His 1791 treatise De Viribus Electricitatis in Motu Musculari Commentarius documented over a decade of research demonstrating that biological tissues generate intrinsic electrical currents. Although Alessandro Volta disputed his interpretation, Galvani's insight proved correct and was confirmed by Aldini in 1794 and von Humboldt in 1797. His discovery laid the conceptual groundwork for all subsequent electrophysiological research, earning him recognition as the father of electrophysiology (Britannica, 2025; Catacuzzeno et al., 2024).

Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow (1846–1891), an Austrian physiologist, contributed to early electrophysiology and was among those who observed electrical phenomena related to brain activity in the late nineteenth century. He recorded visual cortical potentials in 1833 but did not describe rhythmic oscillations.

Emil Heinrich du Bois-Reymond (1818–1896), a German physiologist, advanced Galvani's findings by developing precise instruments to measure nerve impulses. Around 1850, he demonstrated that electrical signals travel along nerves to effector organs, including muscles. His work provided the theoretical foundation suggesting that electrical activity might also characterize brain function. This hypothesis inspired subsequent researchers to explore electrical potentials in the central nervous system (van Esveld, 2024).

Gustav Theodor Fritsch (1838–1927) and Eduard Hitzig (1838–1907) were German physicians who in 1870 first demonstrated that electrical stimulation of specific cortical areas produces contralateral motor responses. Their experiments on dogs established the principle of cortical localization of motor function. This discovery was essential for understanding that brain activity relates to specific behavioral functions, a concept fundamental to EMG biofeedback and neurofeedback (Swartz & Goldensohn, 1998).

Richard Caton (1842–1926) a British physician in Liverpool, first recorded electrical activity from exposed animal brains in 1875. Using a sensitive galvanometer, he detected feeble currents from the gray matter of rabbits and monkeys. Caton observed that these currents changed during sensory stimulation and sleep, anticipating fundamental EEG findings by decades. His work, presented to the British Medical Association, received little attention during his lifetime. Caton's priority in discovering brain electrical activity is now well established (Coenen & Zayachkivska, 2013).

Vasily Iakovlevich Danilewsky (1852–1939), a Russian physiologist, independently confirmed and extended observations of electrical brain activity in the 1870s. Working at Kharkov University, he documented electrical potentials from the brains of various animals. His research contributed to establishing the generality of brain electrical phenomena across species. He published Investigations in the Physiology of the Brain, which explored the relationship between the EEG and states of consciousness in 1877 (Brazier, 1959).

Adolf Beck (1863–1942), a Polish physiologist at Jagiellonian University, made significant EEG contributions in 1890. He discovered continuous spontaneous electrical potentials detected from the brains of dogs and rabbits and observed that these ceased during sensory stimulation, providing the first description of EEG desynchronization (alpha blocking) (Coenen & Zayachkivska, 2013).

Sir Charles Scott Sherrington (1857–1952), a British neurophysiologist, received the Nobel Prize for his work on reflexes and the integrative action of the nervous system. His concept of the synapse and studies of motor control provided the neurophysiological framework for understanding how the nervous system coordinates muscle activity. Sherrington introduced the terms neuron and synapse and published the Integrative Action of the Nervous System in 1906. His work on proprioception directly informed later developments in EMG biofeedback and motor rehabilitation.

Vladimir Pravdich-Neminsky (1879–1952), a Russian physiologist, produced the first photographic recordings of brain electrical activity in dogs in 1912. His technique of photographing galvanometer deflections created permanent records of brain waves. He photographed the EEG and event-related potentials from dogs, demonstrated a 12-14 Hz rhythm that slowed during asphyxiation, and introduced the term electrocerebrogram in 1912. He anticipated the recording techniques that would later be essential for clinical EEG and neurofeedback.

Alexander Forbes (1882–1965) and D. W. Mann (1924) reported replacing the string galvanometer with a vacuum tube to amplify the EEG in 1920. The vacuum tube became the de facto standard by 1936. Forbes was an American neurophysiologist who contributed to the development of vacuum tube amplification technology essential for recording the brain's minute electrical signals. His technical innovations enabled more sensitive EEG recordings, facilitating the spread of electroencephalography in American research and clinical settings.

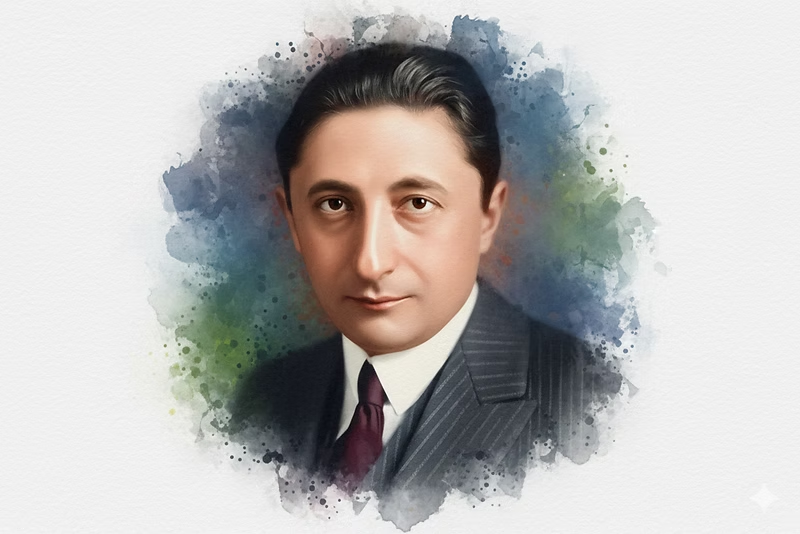

Hans Berger (1873–1941), a German psychiatrist at the University of Jena, achieved the first recording of electrical activity from the intact human brain. Motivated by a mystical experience in which his sister apparently sensed his distress during a military accident, he dedicated his career to discovering the physiological basis of mental phenomena. On July 6, 1924, he successfully recorded human brain activity, publishing his landmark paper Über das Elektrenkephalogramm des Menschen in 1929 and introducing the terms "electroencephalogram," "alpha waves," and "beta waves." Initially met with skepticism, his findings were confirmed in 1934 by Edgar Adrian at Cambridge.

Berger showed that EEG potentials were not due to scalp muscle contractions. He first identified the alpha rhythm, which he called the Berger rhythm, and later identified the beta rhythm and sleep spindles. He demonstrated that alterations in consciousness are associated with changes in the EEG and associated the beta rhythm with alertness. He described interictal activity (EEG potentials between seizures) and recorded a partial complex seizure in 1933. Finally, he performed the first qEEG, which measures the signal strength of component EEG frequencies (Hassett, 1978; Robbins, 2000; Swartz & Goldensohn, 1998).

His tragic suicide in 1941 ended the life of a scientist who revolutionized our understanding of brain function (İnce et al., 2021; Tudor et al., 2005; Vergani et al., 2024).

Researchers who followed Berger validated and extended his findings. Their work identified additional EEG waveforms and inaugurated clinical electroencephalography and sleep medicine.

Edgar Adrian (1889–1977) and B. H. C. Matthews (1934) confirmed Berger's findings by recording their EEGs using a cathode-ray oscilloscope. Their demonstration of EEG recording at the 1935 Physiological Society meetings in England caused its widespread acceptance. Adrian used himself as a subject and demonstrated the phenomenon of alpha blocking, where opening his eyes suppressed alpha rhythms.

Adrian, later Lord Adrian, was a British electrophysiologist at Cambridge University. Though initially skeptical, Adrian replicated Berger's experiments and began publicizing both the method and its discoverer. His earlier Nobel Prize-winning work on nerve impulses made his validation particularly influential (Stone & Hughes, 2013).

Bryan Harold Cabot Matthews collaborated with Edgar Adrian at Cambridge to confirm Berger's EEG recordings. Their joint 1934 publication documented the "Berger rhythm" and its relationship to visual stimulation. Matthews' technical expertise in amplification contributed to establishing EEG as a reliable research and clinical tool (Stone & Hughes, 2013). He developed the oscillograph and differential amplifier, which is used in modern biofeedback and neurofeedback amplifiers.

Frederic Andrews Gibbs (1903–1992), Erna Gibbs (1904-1987), Hallowell Davis (1896–1992), and William Lennox (1884–1960) inaugurated clinical electroencephalography in 1935 by identifying abnormal EEG rhythms associated with epilepsy, including interictal spike waves and 3-Hz activity in absence seizures (Brazier, 1959).

Frederic and Erna Gibbs formed a pioneering husband-and-wife team at Harvard who made crucial contributions to clinical electroencephalography. In 1935, working with William Lennox, they described the characteristic spike-and-wave patterns of absence seizures, establishing EEG as essential for epilepsy diagnosis. Their systematic documentation of seizure-related brain wave patterns created the foundation for modern epilepsy classification (Stone & Hughes, 2013; van Esveld, 2024).

William G. Lennox collaborated with Frederic and Erna Gibbs at Harvard to establish the clinical utility of EEG in epilepsy. His research focused on correlating EEG patterns with different seizure types. Lennox's advocacy for viewing epilepsy as a neurological rather than psychiatric condition helped reduce stigma and improve treatment approaches (Stone & Hughes, 2013).

Hallowell Davis at Harvard Medical School was among the first American researchers to confirm and extend Berger's findings. Working with his wife Pauline Davis in the mid-1930s, he established one of the earliest EEG laboratories in the United States. His work helped transform electroencephalography into a mainstream American research and clinical methodology (Stone & Hughes, 2013).

Frédéric Bremer (1892–1982), a Belgian neurophysiologist, contributed to understanding neural mechanisms of sleep and wakefulness. His preparation studies helped establish the role of sensory input in maintaining arousal, influencing later research on consciousness states relevant to neurofeedback. Bremer used the EEG to show how sensory signals affect vigilance in 1935.

William Grey Walter (1910–1977), was a British neurophysiologist and cyberneticist who made multiple contributions to electroencephalography and neuroscience. He demonstrated that the EEG could localize brain tumors, establishing its diagnostic utility in neurology. Walter also discovered the contingent negative variation, a slow cortical potential associated with expectation and motor preparation important in neurofeedback and brain-computer interface research (Walter, 1937). He named the delta and theta waves. He located an occipital lobe source for alpha waves. Finally, Walter improved Berger's electroencephalograph and pioneered EEG topography (Bladin, 2006).

Nathaniel Kleitman (1895–1999) has been recognized as the "Father of American sleep research" for his seminal work in sleep-wake cycle regulation, circadian rhythms, the sleep patterns of different age groups, and the effects of sleep deprivation. He discovered rapid eye movement (REM) sleep with his graduate student Aserinsky in 1953.

William Charles Dement (1928–2020), another of Kleitman's students, founded the Stanford Sleep Research Center and became the leading advocate for sleep medicine. His research on sleep stages, sleep deprivation, and sleep disorders established sleep medicine as a clinical specialty. Dement's work on the EEG characteristics of different sleep stages informed neurofeedback protocols targeting sleep architecture.

Per Andersen and S. A. Andersson (1968) contributed to understanding physiological mechanisms underlying thalamocortical rhythms and EEG oscillations. Their research on rhythmic brain activity generation has informed the neurophysiological understanding of brain waves targeted in neurofeedback.

Joe Kamiya (1925–2024), a psychologist at the University of Chicago and later Langley Porter Institute, is recognized as the "Father of Neurofeedback." In the late 1950s, he discovered that humans could learn to recognize and voluntarily control their brain wave states when provided with feedback. Participants learned to generate alpha waves on demand, describing strategies such as "letting go" to maintain the alpha state. His 1968 Psychology Today article ignited public fascination with what the media termed "electronic Zen." Kamiya co-founded the Biofeedback Research Society (Kamiya, 1968; Stoyva & Kamiya, 1968).

Both the public and academic worlds recognize Joe Kamiya as the father of biofeedback. In 1966, while monitoring participants' EEGs in his sleep lab at the University of Chicago, he performed a novel experiment by ringing a bell whenever an alpha burst occurred. He discovered that some participants could discriminate when they produced alpha activity. (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 143)

Barbara B. Brown (1921–1999) demonstrated the clinical use of alpha-theta biofeedback. In research designed to identify the subjective states associated with EEG rhythms, she trained participants to increase the abundance of alpha, beta, and theta activity using visual feedback. She recorded their subjective experiences when the amplitude of these frequency bands increased. Brown also helped popularize biofeedback by publishing a series of books, including New Mind, New Body (1974), Stress and the Art of Biofeedback (1977), and Supermind (1980). Brown participated in founding the Biofeedback Research Society and articulated a vision of biofeedback extending to personal growth and spiritual development.

Thomas Mulholland (1927-2020) and Erik Peper (1971) showed that occipital alpha increases with eyes open and not focused and is disrupted by visual focusing, a rediscovery of alpha blocking.

Mulholland contributed to early EEG biofeedback research, particularly studying the relationship between visual attention and alpha waves. His work on alpha blocking helped establish the scientific basis for attention-related neurofeedback applications. Mulholland participated in founding the Biofeedback Research Society.

Elmer (1917–2017) and Alyce Green (1907–1994) investigated voluntary control of internal states and contributed to the development of biofeedback, conducting groundbreaking research at the Menninger Foundation beginning in 1964. With his wife Alyce, he demonstrated that ordinary people could learn voluntary control over brain waves, muscle tension, heart rate, and skin temperature. Their research with Swami Rama documented extraordinary physiological self-regulation abilities. The Greens' 1977 book Beyond Biofeedback explored the transpersonal dimensions of self-regulation. Green co-founded the Biofeedback Research Society (Green & Green, 1977; Green Foundation, 2017).

They developed alpha-theta training at the Menninger Foundation from the 1960s to the 1990s. They hypothesized that theta states allow access to unconscious memories and increase the impact of prepared images or suggestions. Their alpha-theta research fostered Peniston's development of an alpha-theta addiction protocol.

They pioneered temperature biofeedback training for Raynaud's, migraine, and hypertension, and wrote the classic Beyond Biofeedback (1977).

Alyce Green co-directed the Voluntary Controls Program at the Menninger Foundation, personally training the majority of early research subjects and becoming the first clinical director of the Biofeedback Center. She was instrumental in evolving biofeedback from research to clinical tool. Alyce became the first president of the Association for Transpersonal Psychology in 1972. Her hypothesis that theta brain waves associate with hypnagogic imagery stimulated innovative theta neurofeedback research (Green Foundation, 2017).

Lester Fehmi (1969), a psychologist and founder of the Princeton Biofeedback Centre, developed the Open Focus training method based on alpha wave research. Fehmi observed that alpha waves are associated with a diffuse, receptive attentional style contrasting with narrow, object-focused attention. His training programs combine alpha neurofeedback with attention exercises, bridging neurofeedback and contemplative practice.

Thomas Hice Budzynski (1933–2011) developed a twilight learning device that monitors left hemisphere EEG while a patient sleeps and plays recorded affirmations (positive statements) when theta is present. The premise of twilight learning is that affirmations have a greater impact when presented in a transitional state in which theta waves replace the alpha rhythm.

He studied the lateralization of brain function across the two cerebral hemispheres. Budzynski explored using neurofeedback and audio-visual stimulation to correct age-related cognitive decline.

M. Barry Sterman (1935–2023), a neuroscientist at UCLA, made the serendipitous discovery that established neurofeedback as a clinical treatment modality. While training cats to produce sensorimotor rhythm bursts, he observed that these cats later showed remarkable resistance to chemically-induced seizures. In 1972, he published his first human study demonstrating that a patient with medication-resistant epilepsy achieved 65% seizure reduction through SMR neurofeedback. His rigorous methodology established that clinical effects were genuine. Sterman's meta-analytic reviews confirmed neurofeedback efficacy for epilepsy (Arns et al., 2024; Sterman, 2010; Sterman & Friar, 1972). Sterman also co-developed the Sterman-Kaiser (SKIL) QEEG database.

Niels Birbaumer (1945-), a German psychologist at the University of Tübingen, pioneered slow cortical potential neurofeedback and brain-computer interfaces. His research demonstrated that epileptic patients could learn to regulate SCPs, reducing seizures. Birbaumer's most significant contribution was developing the Thought Translation Device, allowing completely paralyzed ALS patients to communicate by shifting cortical potentials. His "goal-directed thought extinction hypothesis" influenced understanding of consciousness in severe paralysis (Birbaumer et al., 1990, 1999, 2009). Birbaumer and colleagues have investigated the efficacy of slow cortical potential biofeedback in treating ADHD, epilepsy, and schizophrenia.

Joel Lubar (1938-2024) studied SMR biofeedback to treat attention disorders and epilepsy in collaboration with Sterman. He demonstrated that alpha-theta neurofeedback training could improve attention and academic performance in children diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity (ADHD). He documented the importance of theta-to-beta ratios in ADHD and developed theta suppression-beta enhancement protocols to decrease these ratios and improve student performance.

Key Takeaways: Brain Research

The development of neurofeedback built upon decades of EEG research. Hans Berger recorded the first human EEG and identified alpha and beta rhythms. Joe Kamiya demonstrated that alpha activity could be operantly conditioned, launching the field of neurofeedback. The Greens developed alpha-theta training at the Menninger Foundation, while Sterman showed that SMR training could reduce seizures. Lubar applied neurofeedback to ADHD, demonstrating improvements in attention and academic performance. These developments transformed the EEG from a purely diagnostic tool into a therapeutic one.

Electrodermal Research

Early electrodermal researchers developed exosomatic and endosomatic methods for recording skin electrical activity. Marjorie Toomim utilized GSR biofeedback in psychotherapy.

Romain Vigouroux (1831–1911), a French neurologist, made early observations of electrical changes in the skin related to neurological and psychological conditions. His work contributed to establishing electrodermal measurement as a clinical tool for assessing autonomic function. He measured skin resistance in patients diagnosed with hysterical anesthesia in 1879.

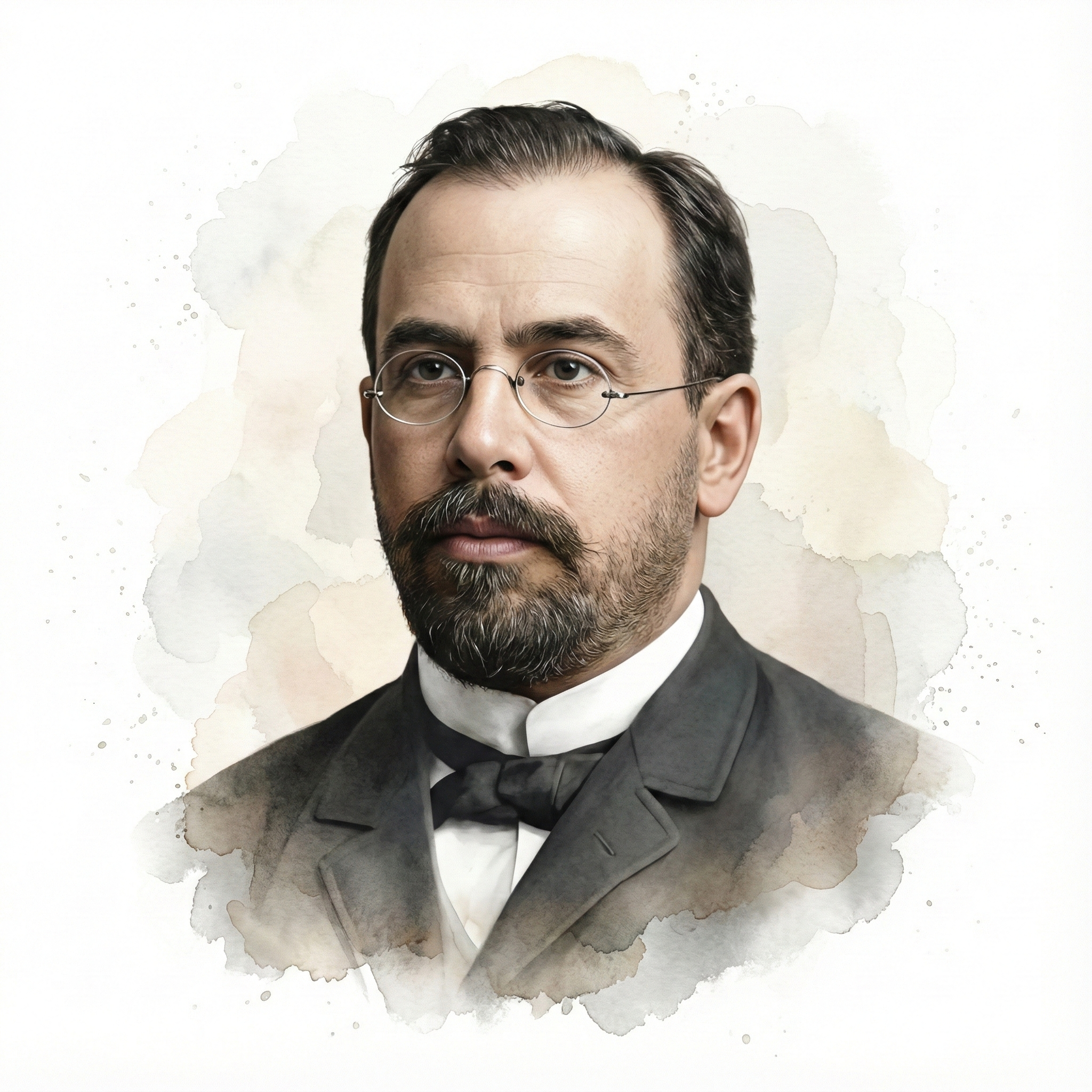

Charles Féré (1852–1907), a French physician, discovered in 1888 that applying a weak current to the skin produces changes in electrical resistance associated with psychological states. His work established the exosomatic method of measuring electrodermal activity. Féré's discovery of what became known as the galvanic skin response provided one of the earliest objective measures of psychological states.

Ivan Tarchanoff (1846–1908), a Russian physiologist, independently discovered the endosomatic measurement of electrodermal activity, observing that the skin generates electrical potentials varying with emotional states. His parallel discovery to Féré's work established electrodermal measurement as a reliable psychophysiological method. The techniques developed by Féré and Tarkhanov evolved into modern skin conductance measurement used in biofeedback.

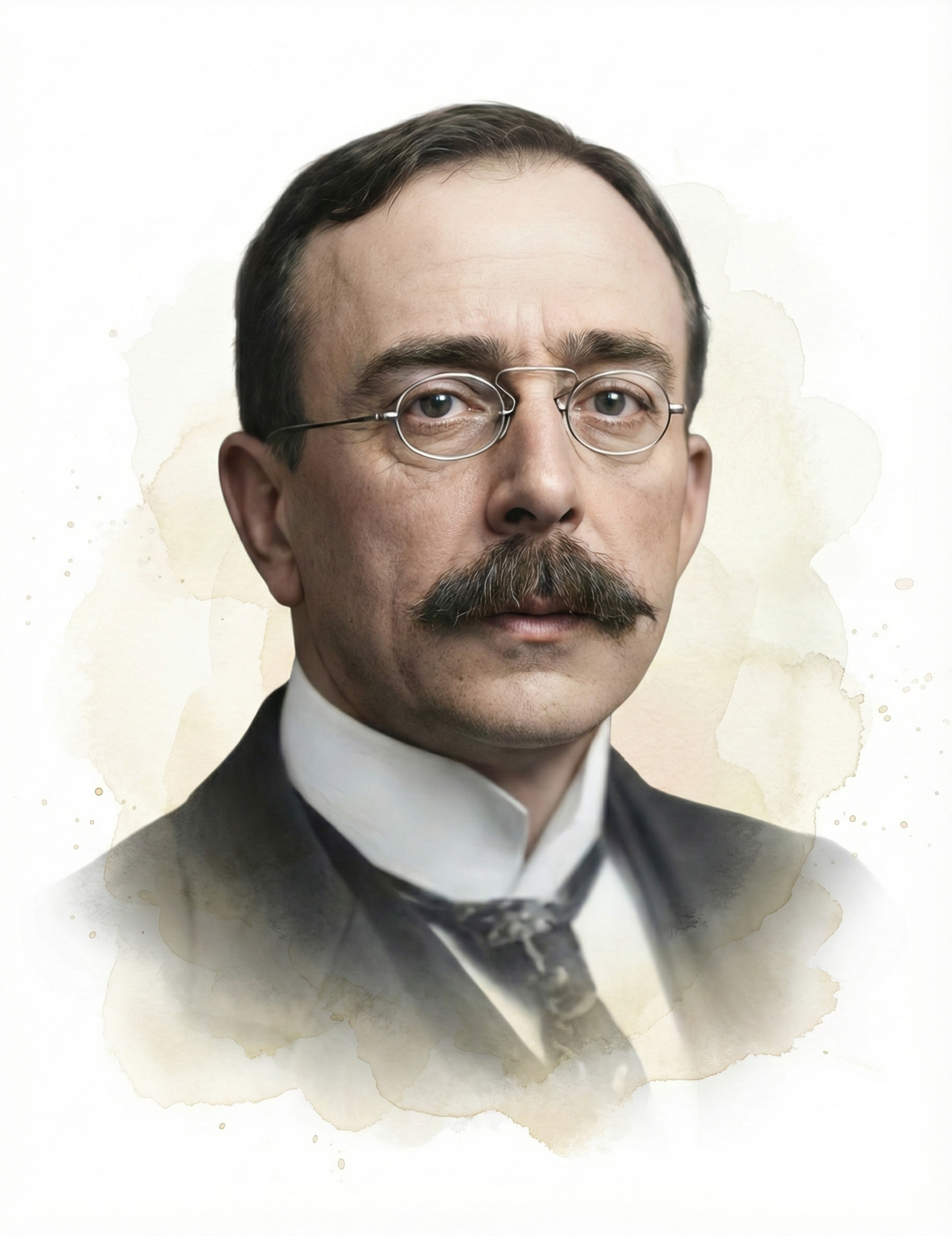

Frederick Peterson (1859-1938) and Carl Jung (1875-1961) employed the galvanometer, which used the exosomatic method to study unconscious emotions. Peterson, an American neurologist, collaborated with Carl Jung in the early 1900s to apply galvanic skin response measurement to the study of emotional complexes. Their research demonstrated that emotionally significant words produce characteristic changes in skin conductance. This work bridged physiological measurement and depth psychology, contributing to biofeedback for emotional awareness.

Marjorie (1923-2005) and Hershel Toomim (1916-2011) published a landmark article about the use of GSR biofeedback in psychotherapy. They pioneered hemoencephalography, a form of neurofeedback based on cerebral blood flow rather than electrical activity. Their development of near-infrared spectroscopy-based neurofeedback created an alternative to traditional EEG methods. Their work on blood oxygenation feedback has influenced applications for attention disorders and migraines.

Electromyographic Research

Edmund Jacobson (1888–1983), an American physician and physiologist, developed Progressive Muscle Relaxation and pioneered electromyographic measurement in relaxation research. He developed the electromyograph to measure EMG voltages over time. Beginning his investigations at Harvard in 1908, Jacobson demonstrated that muscular tension accompanies mental states and that systematically relaxing muscles produces mental calm. His 1929 book Progressive Relaxation established the clinical method. Jacobson's use of EMG to document relaxation effects anticipated modern EMG biofeedback.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Electromyographic Research and Relaxation

Several researchers showed that human participants could learn precise control of individual motor units (motor neurons and the muscle fibers they control).

Donald B. Lindsley (1907-2003), was an American psychophysiologist who contributed extensively to understanding the relationship between brain electrical activity and behavior. He found that relaxed participants could suppress motor unit firing without biofeedback training. His research on arousal, attention, and the reticular activating system helped establish the neurophysiological basis of consciousness states central to biofeedback. Lindsley's work bridged experimental psychology and neurophysiology.

V. F. Harrison and O. A. Mortensen (1962) trained participants using visual and auditory EMG biofeedback to control individual motor units in the leg's tibialis anterior muscle.

John V. Basmajian (1921–2008), a Turkish-Canadian physician at Emory University, is widely recognized as the "Father of EMG Biofeedback." In his landmark 1963 Science paper, he demonstrated that subjects could learn voluntary control over single motor units when provided with auditory and visual feedback of their EMG activity. This revolutionary finding contradicted prevailing assumptions that individual motor neurons could not be consciously controlled. His definitive text Muscles Alive influenced generations of researchers and clinicians (Basmajian, 1963). Basmajian demonstrated practical applications for neuromuscular rehabilitation, pain management, and headache treatment.

Alberto Marinacci (1913–1995), an Italian-American neurologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, pioneered the clinical application of EMG biofeedback for neuromuscular rehabilitation. He was among the first physicians to use EMG feedback systematically for stroke rehabilitation and other motor disorders. Marinacci's clinical innovations demonstrated that patients with neurological damage could regain motor function through EMG-guided training.

Physicians Alberto Marinacci and George Whatmore practiced clinical biofeedback before the term existed. In the 1950s and 1960s, Marinacci used EMG biofeedback to treat diverse neuromuscular disorders ranging from stroke to spasticity. In his 1955 book Clinical Electromyography, he reported numerous successful EMG applications. Unfortunately, other clinicians did not adopt his work because the culture could not conceive that patients could learn to voluntarily control their motor system and because his training protocol often required a year. (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 145)

George Bernard Whatmore (1917-2009) and Daniel Kohli (1916-2009) introduced the concept of dysponesis (misplaced effort) to explain how functional disorders (where body activity is disturbed) develop. Bracing your shoulders when you hear a loud sound illustrates dysponesis since this action does not protect you from injury.

George Whatmore, a Seattle physician present at the founding meeting of the Biofeedback Research Society, devoted his career to understanding functional disorders through neurophysiology. His early electromyographic studies with Richard Ellis revealed that psychiatric patients exhibited elevated motor activity across multiple muscle groups, leading him to propose that functional disorders arise from normal neurons firing in patterns detrimental to the organism. In 1968, Whatmore and collaborator Daniel Kohli introduced dysponesis, from the Greek for "faulty effort," to describe a reversible state of covert errors in energy expenditure that interfere with nervous system function. Their 1974 book represented twenty-three years of clinical work explaining how the combined efforts of "try hard harder" and "grin and bear it" produce functional disturbances throughout the body. Whatmore's treatment used multichannel electromyography to identify hidden muscular bracing and employed biofeedback to retrain the nervous system through effort management (Whatmore & Ellis, 1958, 1959; Whatmore & Kohli, 1968, 1974).

Daniel Kohli served as co-architect of the dysponesis model alongside George Whatmore at their Seattle practice, translating neurophysiological principles into practical clinical protocols. Together they recognized that most energy expenditure underlying functional illness is covert, going unnoticed by patients and observers, yet exerting detrimental influence through aberrant signal patterns throughout the nervous system. Their work established that functional disorders arise when individuals respond to stress with maladaptive muscular bracing, breathing patterns, and autonomic arousal that produce only illness and fatigue. Kohli and Whatmore developed diagnostic protocols using multichannel EMG to detect subtle bracing patterns escaping ordinary clinical observation, emphasizing that dysponesis is fundamentally reversible through systematic neuromuscular retraining. Their model continues to influence biofeedback practitioners, with the insight that maladaptive effort patterns underlie headache, backache, fatigue, and anxiety remaining central to understanding stress-related disorders (Whatmore & Kohli, 1968, 1974).

Jeff Cram, Steven Wolf, Erik Peper, and Edward Taub contributed to EMG assessment, ergonomic and workplace applications of SEMG, and spinal cord injury and stroke rehabilitation.

Jeff Cram (1949-2005) contributed extensively to surface EMG assessment and biofeedback for musculoskeletal disorders. His work on scanning EMG evaluation and treatment protocols has influenced clinical practice in rehabilitation and pain management. Cram's textbook contributions have helped standardize EMG biofeedback methodology. He developed static and dynamic EMG assessment protocols, including muscle scanning using a movable EMG sensor. He identified anatomical sites for low back pain and headache assessment, published normative EMG values, and emphasized the importance of asymmetrical muscle activation in these disorders.

Steven Wolf (1983), Professor of Rehabilitation Medicine at Emory University School of Medicine, pioneered the application of EMG biofeedback to stroke rehabilitation and developed assessment tools that transformed how clinicians measure motor recovery. His systematic research in the 1970s and 1980s established rigorous protocols for using electromyographic feedback with hemiplegic patients, demonstrating that chronic stroke survivors could achieve substantial improvements in upper extremity neuromuscular function and identifying patient characteristics predictive of beneficial outcomes.

Wolf developed the Wolf Motor Function Test, a standardized 15-task assessment measuring time to complete upper extremity movements that has become one of the most widely used outcome measures in stroke rehabilitation research worldwide.

He led the landmark EXCITE (Extremity Constraint-Induced Therapy Evaluation) randomized clinical trial, published in JAMA in 2006, which demonstrated that constraint-induced movement therapy could produce significant rehabilitation of affected limbs in patients 3 to 9 months after stroke, challenging the prevailing neurological nihilism about therapeutic interventions in this population.

His research has explored mechanisms of cortical reorganization using transcranial magnetic stimulation to map motor cortical changes following rehabilitation, bridging the gap between clinical outcomes and neuroplasticity. A Fellow of the American Physical Therapy Association, Wolf has spent decades training future rehabilitation research scientists and continues to investigate optimal therapy dosing and the relationship between rehabilitation intensity and functional outcomes (Wolf & Binder-Macleod, 1983; Wolf et al., 1979, 1980, 2006).

Edward Taub (1999, 2006) developed Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) for stroke rehabilitation, based on his research on learned nonuse. While not strictly biofeedback, his work on neuroplasticity and motor recovery has influenced rehabilitation approaches that incorporate biofeedback. Taub's research demonstrated that intensive training could produce cortical reorganization and functional recovery after stroke. He demonstrated the clinical efficacy of CIMT for spinal cord-injured and stroke patients.

Cardiovascular Research

Early research by Shearn, Engel and Chism, Schwartz and colleagues, and Fahrion and colleagues explored cardiovascular changes during emotions and demonstrated the potential for voluntary control of blood pressure, heart rate, and premature ventricular contractions.

Donald W. Shearn published a landmark 1962 paper in Science demonstrating that human heart rate could be modified through operant conditioning, providing early experimental evidence that autonomic functions previously considered involuntary could be brought under voluntary control.

In his elegant study, Shearn made delay of electric shock contingent upon acceleration of heart rate, finding that subjects who received contingent shock avoidance increased their heart rate accelerations across sessions while yoked-control subjects receiving non-contingent shock showed declining accelerations. This study was among the first to use feedback as a conditioning tool for cardiovascular responses in humans, establishing a paradigm that would become foundational to heart rate biofeedback. Although Shearn noted that interpretation was complicated by related respiratory changes, his work helped establish the experimental basis for what would become clinical biofeedback applications for cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension, and anxiety disorders (Shearn, 1962).

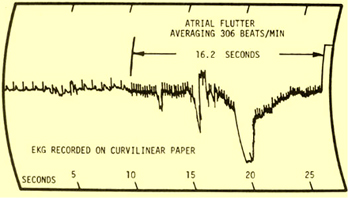

Bernard Engel (1928-2017) and R. A. Chism (1967) operantly trained subjects to decrease, increase, and decrease their heart rates (analogous to ON-OFF-ON EEG training). They used this approach to teach patients to control their rate of premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), where the ventricles contract too soon. Engel conceptualized this training protocol as illness onset training since patients were taught to produce and then suppress a symptom. Peper has similarly instructed asthma patients to wheeze to normalize their breathing (Peper et al., 1979).

Gary E. Schwartz (1944-), Daniel A. Weinberger, and Jefferson Alan Singer (1958-) studied cardiovascular patterning in six emotions using imagery, nonverbal expression, and exercise tasks. Their dependent variables were diastolic and systolic blood pressure and heart rate. Participants' cardiovascular responses discriminated anger from fear (blood pressure) and anger and fear from happiness and sadness. Schwartz explored how patterns of physiological responses relate to specific emotions and health outcomes. Schwartz's systems approaches to biofeedback contributed to understanding how different modalities interact therapeutically.

Johannes Heinrich Schultz (1884–1970) and Wolfgang Luthe (1922–1985) developed and researched Autogenic Training, a deep relaxation exercise derived from hypnosis. Schultz, a German psychiatrist, developed Autogenic Training in the 1920s as a self-relaxation method based on passive concentration and autosuggestion. His technique used formulas focusing on heaviness and warmth in the limbs, cardiac regulation, and other physiological states. Autogenic Training became widely used in Europe and contributed to biofeedback by demonstrating that verbal self-instruction could produce measurable physiological changes. Schultz's Nazi history remains controversial.

Wolfgang Luthe, a German-Canadian physician, collaborated with Johannes Schultz to develop and systematize Autogenic Training. His multivolume work documented the method's applications and physiological effects. Luthe's research on autogenic training's psychophysiological mechanisms influenced the development of self-regulation approaches in biofeedback.

Clinicians at the Menninger Foundation coupled an abbreviated list of standard exercises with thermal biofeedback to create autogenic biofeedback.

Despite their success, Elmer and Alyce faced the same academic myopia that Miller and DiCara encountered. As late as the 1970s, some BSA researchers continued to argue that voluntary hand warming was impossible. Likewise, when Elmer discussed the anatomical evidence supporting psychoneuroimmunology with immunologists, many participants rejected the idea that psychological processes could affect immunocompetence or vice-versa. Green's psychophysiological principle had to be wrong because "everyone knew" that the brain and immune system were completely isolated. (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 144)

Steve L. Fahrion (1986) and colleagues conducted biofeedback research at Menninger, contributing to treatment protocols combining thermal biofeedback with autogenic training for hypertension. His report described a comprehensive program producing significant blood pressure reductions. Fahrion helped establish multimodal biofeedback protocols.

Robert Freedman (1988, 1991) demonstrated that hand-warming and hand-cooling are produced by different mechanisms. He conducted research on thermal biofeedback for Raynaud's disease, demonstrating that patients could learn to increase finger blood flow and reduce symptom frequency. His controlled studies helped establish the efficacy of temperature biofeedback for peripheral vascular disorders.

Evgeny Vaschillo (1945-2020), a Russian psychophysiologist, developed the concept of resonance frequency heart rate variability biofeedback. His research demonstrated that each individual has a characteristic frequency at which respiratory-induced heart rate oscillations reach maximum amplitude. Training at this frequency maximizes baroreflex gain and produces therapeutic benefits. Vaschillo and colleagues (1983) published the first studies of HRV biofeedback with cosmonauts and treated patients diagnosed with psychiatric and psychophysiological disorders (Chernigovskaya et al., 1990).

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Vaschillo and Colleagues

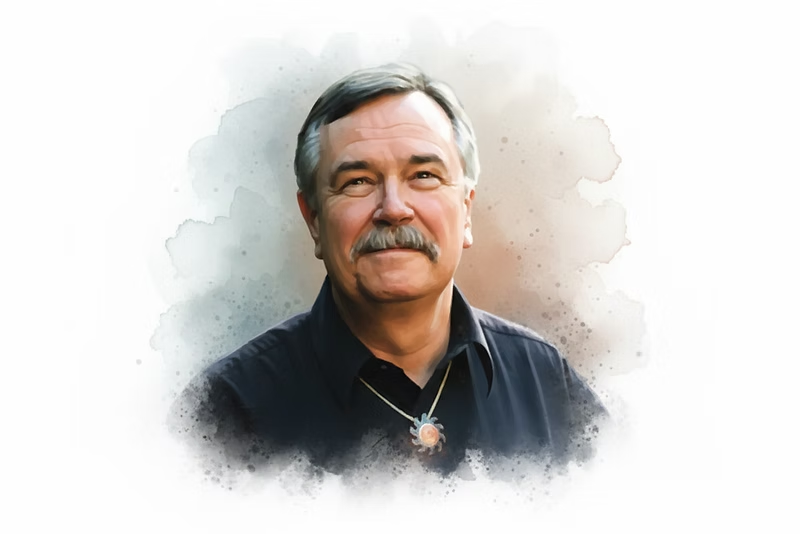

Paul M. Lehrer, a Harvard-trained clinical psychologist and Professor Emeritus at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, stands as one of the architects of modern heart rate variability biofeedback and perhaps the last living student of Edmund Jacobson. His career shifted dramatically in 1992 during a visit to St. Petersburg, Russia, where he discovered a clinic using HRV biofeedback to treat children with asthma and met Evgeny Vaschillo, whose doctoral research had demonstrated how slow breathing stimulates resonance in the baroreflex system.

Lehrer helped Vaschillo emigrate to the United States, and their collaboration produced the resonant frequency biofeedback protocol that has become the worldwide standard, exploiting cardiovascular resonance at approximately 0.1 Hz to amplify heart rate variability four to ten times above baseline. Their controlled studies demonstrated that HRV biofeedback improved pulmonary function in asthma patients, decreased symptoms, allowed reductions in steroid medications, and produced lasting increases in baroreflex gain suggesting neuroplasticity rather than merely acute effects.

Beyond HRV biofeedback, Lehrer shaped the broader field as co-editor of Principles and Practice of Stress Management, the definitive textbook now in its fourth edition. He served as president of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, received their Distinguished Scientist Award, and served as Editor-in-Chief of Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback (Lehrer, 2013; Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Lehrer et al., 2000, 2004, 2020; Vaschillo et al., 2002, 2006).

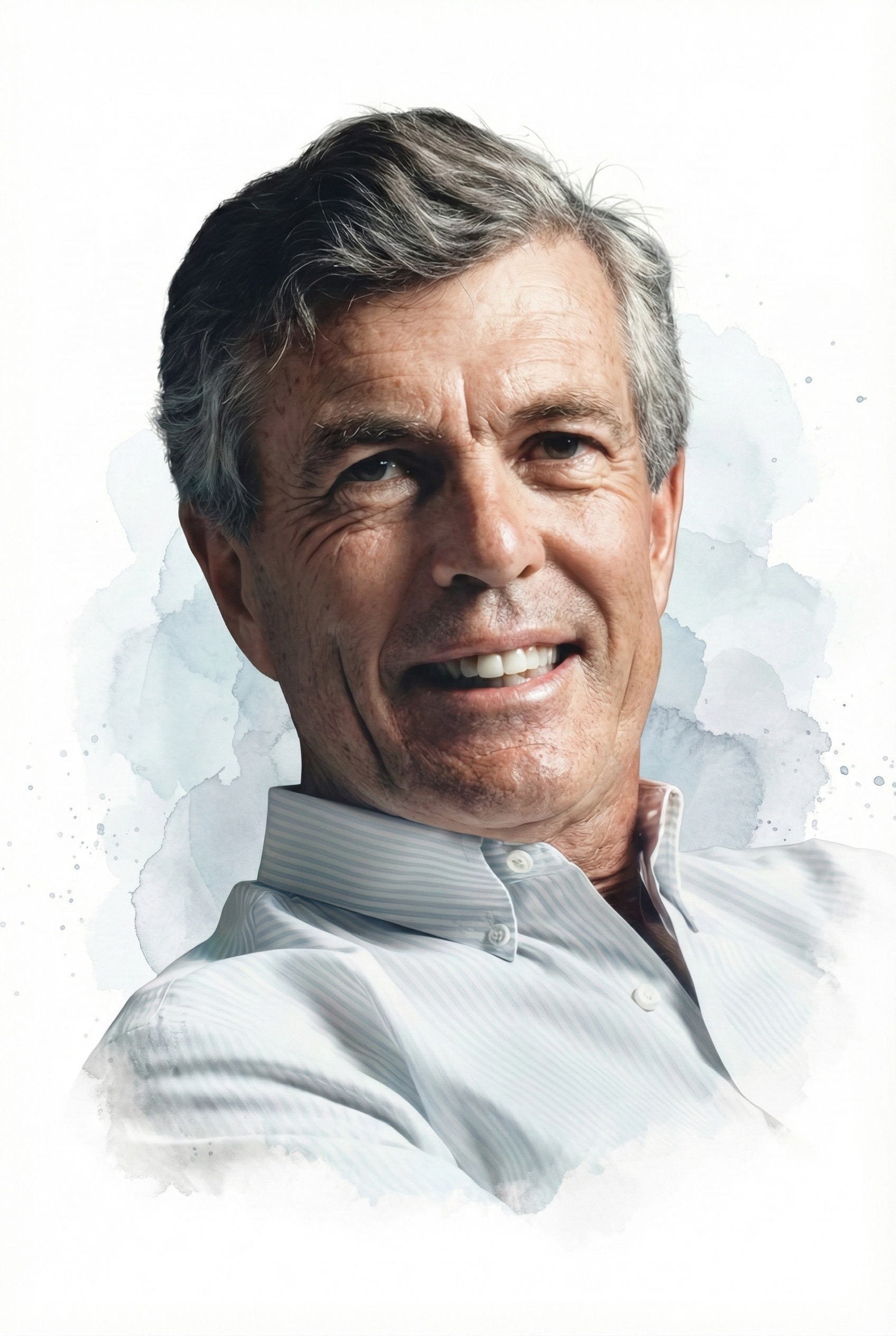

Richard Gevirtz, Distinguished Professor at Alliant International University, became one of the chief architects of heart rate variability biofeedback through his remarkable capacity for mentoring doctoral students and generating clinical evidence across diverse populations. His early collaboration with neurologist David Hubbard produced landmark findings that myofascial trigger points exhibit spontaneous electrical activity responding selectively to psychological stress, leading to his muscle spindle trigger point model of chronic pain.

Gevirtz's laboratory trained generations of students who demonstrated HRV biofeedback's efficacy: Pat Humphreys showed 97% pain reduction in children with recurrent abdominal pain, Jessica Del Pozo found that coronary artery disease patients increased HRV by 50% and hypertensive patients became normotensive, and collaborative research with Gabriel Tan demonstrated reduced PTSD symptoms in combat veterans.

His partnership with Paul Lehrer produced the landmark 2014 Frontiers in Psychology paper synthesizing evidence for multiple mechanisms, and as Lehrer wrote, Gevirtz is "the consummate teacher, whose acumen, energy, and engaging manner brought bright doctoral students to his laboratory" (Del Pozo et al., 2004; Gevirtz, 2013; Hubbard & Berkoff, 1993; Humphreys & Gevirtz, 2000; Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Tan et al., 2011).

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Richard Gevirtz

Pain Research

Thomas Hice Budzynski (1933–2011) and Johann Stoyva (1931-2025) were pioneers in EMG biofeedback fo headache pain. Budzynski, an American psychologist, invented the first practical EMG biofeedback system in the mid-1960s at the University of Colorado. With Johann Stoyva, he demonstrated that frontalis EMG feedback training could reduce tension headaches. His controlled studies established EMG biofeedback as an effective clinical treatment. Budzynski later developed theta neurofeedback protocols for treating anxiety and enhancing learning (Budzynski et al., 1973).

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Pain Research

Johann Stoyva collaborated with Thomas Budzynski at the University of Colorado to develop EMG biofeedback treatment for tension headaches. Their research demonstrated that reducing frontalis muscle tension through biofeedback produced significant reductions in headache frequency and severity. Stoyva contributed to understanding the relationship between muscle tension, stress, and headache disorders (Budzynski et al., 1973; Stoyva & Kamiya, 1968).

Budzynski, Stoyva, and Adler (1971) reported that auditory frontalis EMG biofeedback combined with home relaxation practice lowered tension headache frequency and frontalis EMG levels. A control group that received noncontingent (false) auditory feedback did not improve. This study helped make the frontalis muscle the placement-of-choice in EMG assessment and headache treatment and other psychophysiological disorders.

The clinical applications of EMG biofeedback, especially those for tension headaches and psychotherapy, owe their origins to the creative work of Thomas Budzynski and Johann Stoyva, who published the first study using EMG feedback for the treatment of tension headaches (Budzynski, Stoyva, & Adler, 1970). Their successful clinical study incorporated relaxation practice as homework. They clearly foresaw that successful biofeedback training involves more than just teaching a skill in the office. In most cases, success depends on transferring and integrating the learned skill into the patients' daily lives. (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 145)

J. D. Sargent, E. E. Green, and E. D. Walters (1972) at the Menninger Foundation developed autogenic feedback training by combining biofeedback techniques with autogenic training, a therapeutic method involving simultaneous management of mental and somatic functions through self-suggestion of warmth and heaviness. Their discovery came serendipitously when a research participant found that her sudden recovery from a migraine attack coincided with an increase in hand temperature of 10°F in just 2 minutes, suggesting that voluntary control of peripheral blood flow might abort migraine attacks.

This observation led to their 1972 pilot study published in Headache, followed by a 1973 Psychosomatic Medicine paper reporting that 28 migraine and tension headache sufferers who practiced hand-warming exercises showed significant reductions in headache activity. Although methodologically limited by the absence of pretreatment baselines, control groups, or random assignment to conditions, their work established the rationale that increasing blood flow to the hands through learned vasodilation might counteract the cranial vasoconstriction thought to trigger migraines.

The Menninger migraine studies profoundly influenced clinical practice, spawning decades of research on thermal biofeedback that eventually established it as an efficacious treatment for migraine, and their integration of autogenic phrases with temperature feedback became a standard protocol in headache clinics worldwide (Sargent, Green, & Walters, 1972, 1973).

Herta Flor (2002) a clinical psychologist at the University of Heidelberg, has collaborated with Niels Birbaumer on research integrating neurofeedback with pain neuroscience. Her work on phantom limb pain and cortical reorganization has informed neurofeedback approaches to chronic pain. Flor's research bridges psychophysiology, neuroimaging, and clinical treatment.

Check Your Understanding: Divergent Movements

- How does the bedwetting alarm illustrate classical conditioning principles?

- What was Joe Kamiya's key contribution to neurofeedback, and how did his work fit into the cultural context of the 1960s?

- Explain the concept of dysponesis and provide an example from everyday life.

- What did Robert Freedman's research reveal about the mechanisms underlying hand-warming and hand-cooling?

- Why was the work of Marinacci and Whatmore not widely adopted despite their clinical successes?

Conclusion: The Continuing Tapestry

The beauty of the tapestry of biofeedback history has come from the unique perspectives of its contributors; the courage of researchers such as Joe Kamiya, Neil Miller, and Leo DiCara to challenge prevailing dogma; the generosity of mentors such as Thomas Mulholland; and the imagination of visionaries such as Elmer and Alyce Green. Continued progress in biofeedback depends on vigorous collaboration between clinicians and academic researchers. Clinicians can teach investigators how to successfully train their participants, whereas researchers can help clinicians evaluate the efficacy of their interventions. (Peper & Shaffer, 2010, p. 146)

Key Takeaways: History

Biofeedback emerged from the convergence of ancient wisdom and modern science. Eastern practices of self-regulation, dating back thousands of years, met cybernetic theory and operant conditioning research in the mid-20th century. Pioneers like Miller, DiCara, Kamiya, and the Greens challenged the dogma that autonomic processes could not be voluntarily controlled. The field developed diverse applications in incontinence, brain training, electrodermal response, muscle reeducation, cardiovascular regulation, and pain management. Today, biofeedback continues to evolve as technology advances and research expands our understanding of human self-regulation.

Biofeedback Timeline

Francine Butler was indispensable in the founding and guidance of the Biofeedback Society of America (now the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback; AAPB) and the Biofeedback Certification Institute of America (now the Biofeedback Certification International Alliance; BCIA). She has generously and wisely mentored generations of leaders in our field. Fran continues to advocate for biofeedback and promote AAPB and BCIA's missions.