Professional Ethics

What You Will Learn

This unit will equip you with the ethical foundation every biofeedback provider needs. You will explore how professional ethics protect both you and your clients, and learn to recognize common ethical dilemmas before they escalate. We will examine the investigative clinician's mindset, showing you how to look beyond initial presentations and DSM-5 labels to identify underlying causes that could transform treatment outcomes. You will discover how to practice across diverse communities while respecting cultural norms, and understand the weight of professional responsibility that comes with influencing your clients' lives.

Building competence is a career-long journey, and you will learn what entry-level proficiency really means and how to expand your expertise through continuing education. We will clarify the critical differences between mentoring and supervision, and help you understand when each relationship is appropriate for your professional development. You will master the ethical standards that govern public statements, advertising, and professional claims, ensuring your communications remain accurate and trustworthy.

Confidentiality and informed consent form the bedrock of the therapeutic relationship, and you will learn to navigate these obligations even in challenging situations. We will examine client welfare from multiple angles, including equipment selection, infection control protocols that could prevent a lawsuit, medication interactions that require physician coordination, and the boundaries of professional relationships. You will also understand your responsibilities when conducting research with human and animal subjects.

The unit clarifies BCIA's role in maintaining professional standards, walks you through the ethics complaint process, and explains the crucial differences between certification and licensure. Finally, you will confront the emerging ethical challenges of practicing in a digital world, from protecting your clients' data on apps and wearables to navigating telehealth, artificial intelligence, and the evolving patchwork of privacy laws. By the end of this unit, you will have the practical knowledge to navigate ethical challenges with confidence throughout your career.

This unit complements the Biofeedback blueprint and supports BCIA's requirement that applicants complete 3 hours of ethics education.

Professional ethical standards help educators, researchers, and practitioners anticipate and identify ethical dilemmas and make choices that maintain one's professional integrity and protect our clients and profession (Striefel, 2003). Graphic © Andrzej Rostek/iStockphoto.com.

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter Lecture

Donald Moss, PhD, contributed extensively to chapter content from his AAPB webinar, Professional Ethics and Practice Standards in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback.

Read Shaffer and Schwartz's "Entering the Field and Assuring Competence" in Biofeedback: A Practitioner's Guide (4th ed.) for an in-depth discussion of the challenges of entering the field and maintaining competence.

The Purpose of Ethics

Ethical standards are intended to protect the public, biofeedback, the professions that deliver biofeedback services, and the providers themselves.

Ethical Standards and the Reputation of the Profession of Biofeedback

Biofeedback providers recognize that their effectiveness and success as professionals, and the credibility of the biofeedback field, depend on their professional conduct.

Each time a biofeedback or behavioral health professional is charged with serious violations of ethical behavior, the field is also tarnished, and potential patients and their family members lose their readiness to trust in professional care (Moss, 2020).

Ethical codes express our stakeholders' core values.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Core Values

Professional Ethics Reflect Personal Integrity

Ethical practices are in the first place aspirational; they reflect the kind of professional one aspires to become. Responsible behavior in professional life should express personal, social, and religious values. Compassion and empathy for one's fellow humans, who come for help with suffering, draws individuals to professional practice. Professionals with diminished empathy due to "burnout" and "compassion fatigue" are at greater risk for ethical transgressions.

Burnout is a widespread problem in the helping professions. Compassion fatigue is one product of using up or depleting our capacities for caring. Maintaining healthy self-care practices is critical in avoiding compassion fatigue. Difficulties in establishing rapport and mutual empathy in treatment relationships are also a challenge for professionals. When patients do not feel strong rapport and trust in their provider, they are more likely to file complaints (Moss, 2020).

Beneficence in Biofeedback Practice

"Providers strive to protect their clients' welfare by appreciating their impact on the clients' lives, and by recognizing and avoiding the potential for conflicts of interest" (Moss, 2020).

The ethical responsibilities of biofeedback providers and their staff are collectively defined by the licensing act under which they (or their supervisors) operate, their profession, and the BCIA's Professional Standards and Ethical Principles of Biofeedback (9th rev.). The BCIA's PSEP represents the minimum ethical standards expected of its applicants and certificants. Physicians who provide biofeedback must also follow medical ethical guidelines. Psychologists must adhere to the Ethical Standards of the APA (Moss, 2013).

Providers deliver biofeedback services within a context of legal statutes, cultural norms, professional standards, and ethical codes that may vary across nations, cultures, and communities. These expectancies may conflict with each other. For example, the American Psychological Association (APA) proscription against dual relationships with clients would prevent a Psychologist from following a community expectation that "healers" visit the client's family and share their religious rituals (Moss & Shaffer, 2016).

Since ethical guidelines can never anticipate all of the contingencies that providers may encounter, they should always consult with their licensing body, professional association, and colleagues as they reach a choice point and are uncertain about future conduct. Unfortunately, the most severe ethical infractions, like sexual relationships with clients, often involve intentional violations of black-and-white rules.

When a licensing body or a court substantiates a charge of ethical misconduct, BCIA may take disciplinary action against a certificant. BCIA does not have the legal authority to compel testimony or the submission of documents. For this reason, it must often wait for a licensing body or court to investigate and reach a decision. When a licensing body or a court substantiates a charge of ethical misconduct, BCIA may take disciplinary action against a certificant. Applicants who have lost or surrendered their license may not be certified until their license is restored. BCIA has no enforcement role when an individual charged with an ethical violation is neither a certificant nor an applicant.

The Investigative Clinician: Beyond Initial Presentations

This section was inspired by Dr. Ron Swatzyna, Director and Chief Scientist of the Houston Neuroscience Brain Center.

When patients present with significant sudden-onset symptoms or prove resistant to conventional treatments, clinicians must transition from diagnostician to detective. Such symptoms may be behavioral, emotional, cognitive, or somatic, with their significance judged within the context of each particular case. The emergence of abrupt changes, particularly in children and adolescents, should trigger immediate consideration of underlying medical, environmental, or infectious causes rather than immediate psychiatric diagnosis and medication trials.

Several clinical scenarios warrant a deeper investigation: the sudden appearance of new symptoms, particularly in previously stable or healthy individuals; failure to respond to two adequate medication trials; or unexpected resistance to properly administered biofeedback or neurofeedback interventions. In these cases, the standard approach of treating based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria may obscure crucial underlying pathology and its etiology.

The EEG serves as a particularly valuable tool in this investigative process. Findings of diffuse slowing, intermittent epileptiform discharges, or spindling excessive beta, can provide objective evidence of neuroinflammation or toxic exposure. These EEG patterns often indicate the presence of triggers such as mold exposure, chemical toxicity, or infectious processes that may be driving the presenting symptoms. EEG patterns may also index changes in sleep quality, medication, or drug use. Changes in socially-mediated supports or stressors are sometimes associated with EEG variations.

Case evidence supports this investigative approach. For instance, apparent treatment-resistant depression may actually stem from chronic inflammatory response syndrome (CIRS) due to mold exposure, while sudden-onset obsessive-compulsive symptoms might indicate PANDAS (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections) or autoimmune encephalitis. Similarly, new-onset attention deficits resistant to standard treatments might result from environmental toxin exposure or nutrient deficiencies rather than primary ADHD.

The clinical implications are clear: when standard treatments fail or symptoms appear abruptly, clinicians should look beyond the presenting symptoms to investigate potential environmental, infectious, or systemic causes. This may involve evaluation for mold exposure, testing for inflammatory markers, assessment of nutrient status, or screening for environmental toxins. The goal is to identify and address the underlying cause rather than simply managing symptoms through psychiatric medication.

This approach requires a paradigm shift from treating DSM-5 diagnoses to treating underlying pathophysiology. While DSM-5 criteria remain valuable for classification and communication, they should not constrain the search for root causes when clinical presentation or treatment response suggests deeper issues.

The presence of objective findings such as EEG abnormalities should particularly prompt investigation of environmental or systemic causes, even when presenting symptoms appear purely psychiatric. By adopting this investigative mindset, clinicians can identify and address root causes that might otherwise go undetected, potentially leading to more effective and lasting therapeutic outcomes. This approach may require additional time and resources initially, but it can prevent years of ineffective symptom management and improve long-term patient outcomes.

Diversity and Cultural Awareness

Since professionals provide biofeedback services across diverse communities, cultures, nations, and geographic regions, they must respect the norms of the cultures they serve and recognize the diversity in legal codes, professional standards, and ethical principles.

American Psychological Association (2017) multicultural guidelines require that practitioners recognize that culture influences an individual's worldview; develop sensitivity to their own cultural identities; use culturally appropriate assessments, interventions, and consultations; understand the socio-cultural contexts that impact individuals' lives; and consider historical and societal barriers that marginalized groups have faced.

This guideline applies to neurofeedback and biofeedback. Assessment and treatment protocols should be consistent with the best available research. The first-line EEG standard chosen for comparison (such as the BrainDX database) should be appropriate for this individual's background (including nation and regional influences, race, socioeconomic status, and immigration history) (Moss, 2020).

Likewise, the biofeedback protocols themselves should be research-based and appropriate. Normative data for biofeedback parameters such as EMG, skin conductance, heart rate and heart rate variability, skin temperature, and respiration rate may not adequately represent minorities, and biofeedback practitioners should be aware that skin color influences optical sensors for PPG and pulse oximetry (Moss, 2020).

Responsibility

Providers are responsible for their clients' welfare and strive to protect them.

Responsibility: Client Assessment

BCIA certificants should apply evidence-based assessment tools for every patient that are appropriate for their conditions (Moss et al., 2019).

A physician with a headache should be evaluated like every other patient with this complaint. We begin with a thorough intake interview, a review of available records, and appropriate assessment and response to the available evidence. We must avoid any pressure to skip over the basics and move immediately to biofeedback or neurofeedback (Moss, 2020).

For more on best practices, click on the podcast link.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Client Assessment

Responsibility: Documentation

Providers maintain appropriate records. Basic documentation requirements are covered by federal statutes (HIPAA), by state statute, and by professional licensing boards. Do not rely on memory for professional purposes (Moss, 2020).

Competence

Competent practitioners only provide services they are qualified to deliver by virtue of their education, training, and experience. Certificants must also practice within their scope of practice since this defines the services they may legally provide.

Practitioners' scope of practice defines the services they may legally provide under their license or supervisor's license under state law. Graphic retrieved from the AOA State Government Relations Center.

Listen to Dr. Moss explain scope of practice © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Compliance with Relevant Laws

Providers comply with applicable laws and the ethical standards of their profession and certifying organization. They require a government license or credential to treat a medical or psychological disorder independently. Those without a license or credential must obtain appropriate supervision to treat these disorders. BCIA certifies licensed practitioners to treat diagnosed disorders, technicians to treat diagnosed disorders under supervision, and non-licensed practitioners to apply biofeedback for relaxation, stress management, or optimal performance (Moss, 2020).

Listen to Dr. Moss explain compliance © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

For example, psychologists may not make nutritional recommendations in most states, and health coaches may not diagnose or treat medical or psychological disorders (Moss, 2013). Although BCIA certifies technicians to practice under supervision, their scope of practice is defined by their supervisor's scope of practice (Moss, 2020). Artist: Dani S @ unclebelang on Fiverr.

Scope of practice is the largest elephant in the room. Until they face complaints, licensed practitioners rarely read the statutes that regulate their scope of practice and professional responsibilities (Hopkins, 2013). Unlicensed certificants may not understand how the scope of practice applies to their activities or their supervisor's license limitations. Without an appropriate license, they may not even legally purchase FDA-regulated devices like electrocephalographs. Graphic © Aleksandr_Kuzmin/Shutterstock.com.

Scope vs. Competence

Licensure defines whether a procedure is allowed for a professional with a given license for the professional's scope of practice. The principle of competence requires that a practitioner also know and train to use a procedure and deal with a specific patient population. Responsible practitioners will practice within the limits of their competence/expertise. When undertaking new applications of biofeedback, it is essential to obtain training on the application and relevant techniques and seek supervision by a professional with experience in biofeedback treatment of this disorder or the use of this technique (Moss, 2020).

Mentoring vs. Supervision

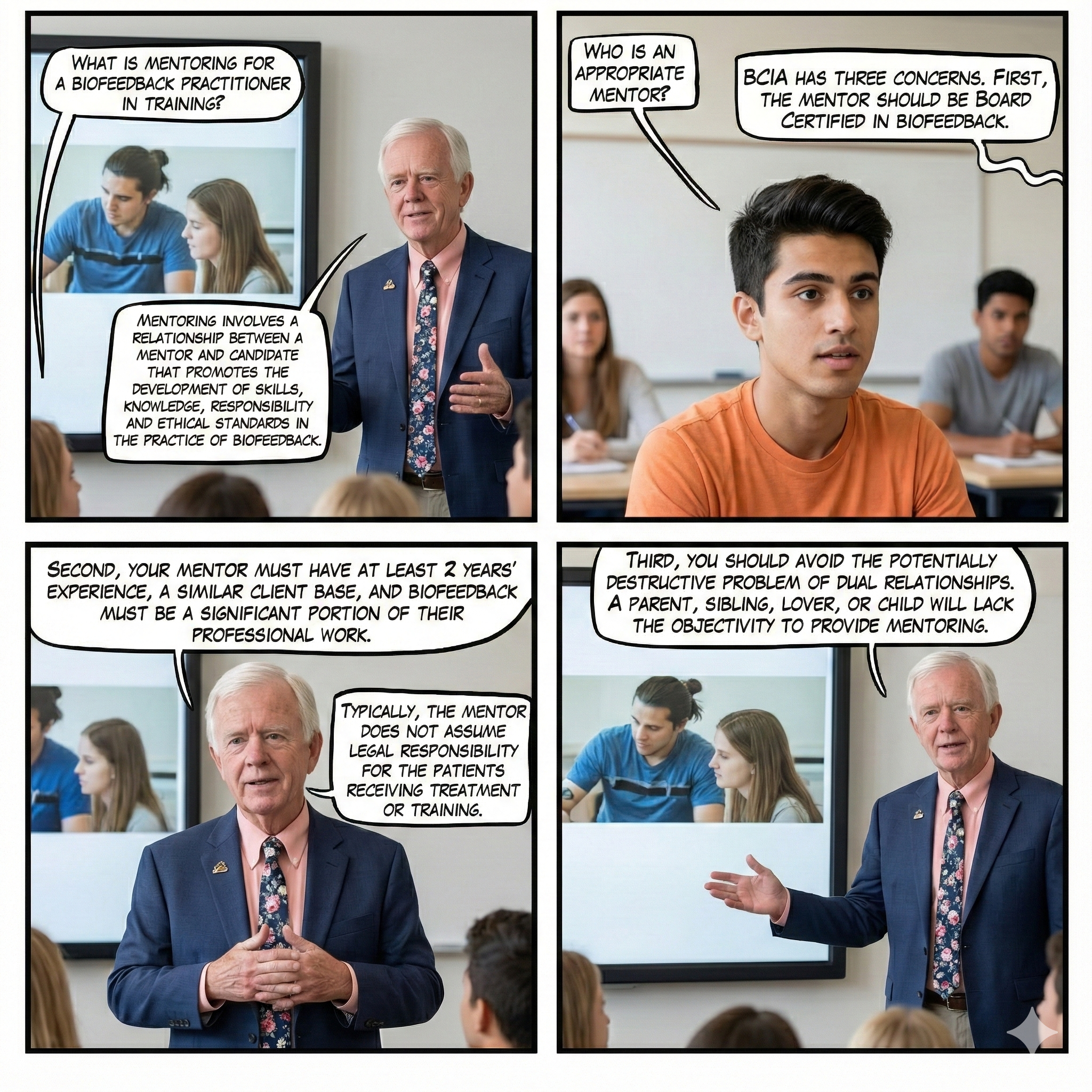

BCIA requires mentoring as an educational process for individuals seeking BCIA certification. Graphic © fizkes/Shutterstock.com.

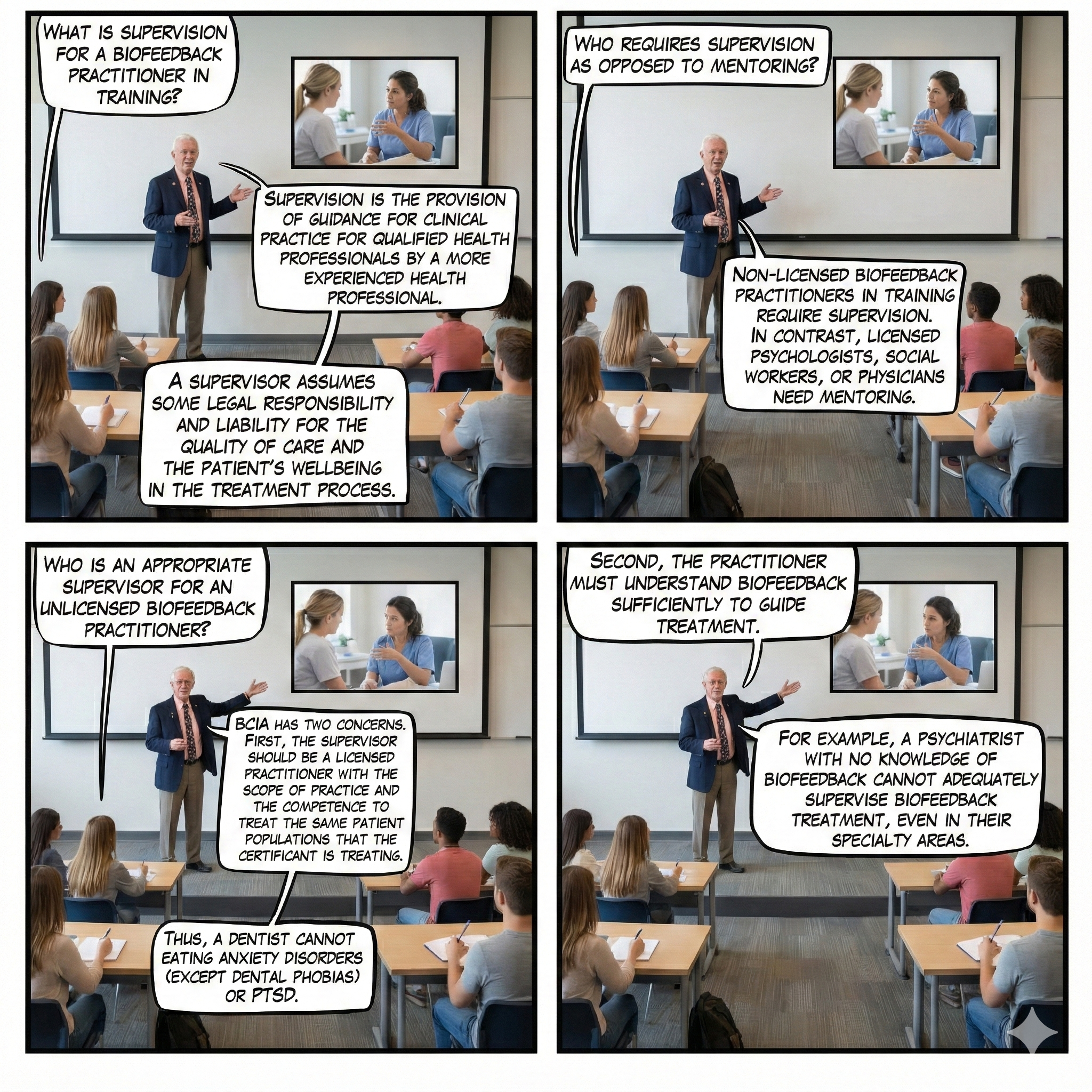

BCIA requires legal clinical supervision for individuals certified as technicians. Peer consultation with colleagues and consultation with area experts are recommended as lifelong strategies to assure the quality of care and to protect against potential patient complaints (Moss, 2020).

Listen to Dr. Moss explain the difference between mentoring and supervision © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Real Genius WEBTOONs by Dani S@unclebelang developed in collaboration with Dr. Don Moss.

Mentoring Defined

Mentoring is the "process of transmitting knowledge and skills from the trained to the untrained or the experienced to the inexperienced practitioner. Mentoring involves a relationship between a mentor and candidate that promotes the development of skill, knowledge, responsibility, and ethical standards in the practice of biofeedback" (bcia.org).

Typically, the mentor does not assume legal responsibility for the mentee's patients receiving treatment or training. The mentor's focus is on the planning and delivery of biofeedback services, not on the entirety of the client's care (Moss, 2020).

Supervision Defined

Supervision is providing guidance for clinical practice for qualified health professionals by a more experienced health professional. In supervision, the supervisor assumes some legal responsibility (and liability) for the quality of care and the patient's wellbeing in the treatment process. A supervisor is responsible to remain cognizant of the entirety of the technician's caseload, client assessment, treatment planning, and treatment delivery (Moss, 2020).

Unacceptable Supervision

Since supervisors assume legal responsibility for client care, they must be physically present at the site where an applicant or unlicensed certificant works. BCIA rejects applications from technicians whose supervisors are not licensed, not legally allowed to supervise biofeedback services, or who can only oversee the delivery of services at a distance. Worst case, from another state!

Ethical Standards

Biofeedback providers recognize their effectiveness and the field's credibility depends on their professional conduct. They only bill for the services they or supervised staff provide. When billing third-party payers, they conscientiously follow the payers' rules and regulations. This includes conservatively using billing codes, obtaining written agreement in advance to use specific codes, differentiating the services they provide from those provided by their supervisees, and accurately describing staff credentials.

Providers have fiduciary responsibility.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Fiduciary Responsibility

They understand that the appearance of a conflict of interest can be as damaging to their reputation as an actual conflict. Whenever possible, they proactively identify potential conflicts and avoid them. For example, workshop presenters should refrain from promoting their products. When a conflict of interest cannot be avoided, they quickly resolve it. For example, providers who serve on boards often recuse themselves from decisions that involve their financial interests.

Client education should include detailed information about assessment and treatment procedures, billing and fee collection, protection of confidentiality, and the limits of confidentiality. Providers should provide clients with a copy of these policies to read as they are carefully explained and only accept written consent when clients indicate they understand them. Informed consent is essential for experimental treatment procedures, which may have a higher risk of failure and client dissatisfaction.

Public Statements

Providers understand that all public statements, ranging from educational talks to the description of services on their website, should be accurate, comprehensive, and conservative to facilitate informed consumer choices. They confine statements about biofeedback to scientifically supported information and communicate the limitations, uncertainties, and strength of these findings. "Discussion of treatment options in marketing materials and professional publications should be evidence-based and current" (Moss, 2020). Graphic © Redaktion93/Shutterstock.com.

Listen to Dr. Moss discuss public statements © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Professional Credentials and Transparency in Marketing and Promotion

Biofeedback providers must accurately disclose their degrees, training, specialty areas, experience, and the status of license or credential and certification. Advertisements for clinical practice should include only treatment or practice-relevant and regionally accredited academic degrees. Example: A PhD in French literature or mathematics should not be included on a business card or in an advertisement. It would mislead the potential client to assume the provider has doctoral-level clinical education.

Example: Current controversy over nurses with PhD or DPN advertising their practices under the title, "Dr. Frances Schmidt." Unless the practitioner uses a further heading to clarify, this seems to mislead the patient to believe Dr. Schmidt is an MD. The appropriate title would be Dr. Frances Schmidt, Clinical Nurse Specialist.

Participation in a membership organization such as AAPB or ISNR does not imply competence. Advertisement of one's professional association membership misleads the health consumer to assume that membership assures training and competence. Advertising BCIA and other forms of certification are legitimate ways to show competence (Moss, 2020).

Listen to Dr. Moss discuss marketing © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Since professional standards are the foundation of clinical practice, BCIA Board voted to apply the American Psychological Association's standard on listing professional credentials to its Board Certified Practitioner and Mentor Directory. Certificants may only list the degrees earned in a BCIA-approved healthcare field from regionally-accredited academic institutions (Crawford & Shaffer, 2014).

They carefully explain the efficacy of biofeedback procedures and the costs, benefits, and limitations of commercial services and products. They cautiously endorse the services and products of others, disclose potential conflicts of interest, and avoid deceiving or exploiting the public.

Confidentiality

Providers protect the confidentiality of the client information they gather, use, and store in any format (including biofeedback recordings), and only share it with individuals in accordance with the law, consent by the client, and the best interests of the client. Providers should be aware that they need informed consent or an exception (e.g., court order, medical emergency) to release information.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Confidentiality

Limitations to Confidentiality

Limitations to confidentiality are based on the Tarasoff ruling (Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California, 1976), duty to warn statute in most states (regarding potential harm to self or others), and mandated reporting of child abuse and elder abuse.

Security of Client Information

Health care providers are required by federal law (HIPAA, HITECH act) to maintain the confidentiality of patient information. Most state health care licensing boards include additional requirements for maintenance of confidentiality. Practitioners should take precautions to protect any data in any form, whether paper or electronic, when transmitting data, storing data, or disposing of data (Moss, 2020).

Providers should take precautions to protect any data in any form, whether paper or electronic. They should secure records with appropriate locks and passwords. When transmitting client information, they should use end-to-end encryption. When they dispose of records, they should carefully shred or destroy the files to prevent compromise (Moss, 2020).

Protection of Client Rights and Welfare

Providers protect their clients' rights and welfare. They acknowledge and respect the dignity and rights of each person without regard to their background or characteristics.

Sexual Conduct

Practitioners never engage in sexual conduct (including sexual intercourse, sexual touching, sexualized behavior or comments, and sexually-charged communications) with patients. Provider-client sexual contact is prohibited by law, by licensing statutes, and by professional standards. Providers should also consult with their licensing authority and professional associations regarding when sexual intimacy is permissible (Moss, 2020).

Touch, Privacy, and Respect

Biofeedback practitioners should recognize that there is almost no physical contact with clients in routine psychological and mental health practice. Providers must take special precautions when attaching biofeedback sensors to a client since it invades personal space, often involves physical contact, and risks misinterpretation. "Biofeedback practice calls for careful development of procedures and routines to provide the rationale for regular touch" (Moss, 2020).

They explain the function of the sensors and how they are attached and ask for permission to place them on the client's body. Whenever feasible, they encourage the client to attach sensors to their own body. This is imperative in invasive protocols, such as pelvic floor biofeedback that uses vaginally- or anally-inserted sensors.

Providers should learn the specialized procedures that have been developed to preserve client modesty. This strategy minimizes physical contact, treats the client as a respected partner, and can strengthen the therapeutic alliance.

When a biofeedback protocol requires sensor placement on a sensitive region (like ECG placement on the torso), the presence of a same-sex nurse or technician and use of garments (like gowns) that preserve client modesty are recommended (Moss, 2013). Wherever possible, use alternative placements (e.g., ECG wrist placement) to afford greater client comfort.

Practitioners do not touch-sensitive body parts like breasts or genitals during biofeedback practice, except as part of a medical examination or medical treatment performed by a licensed medical practitioner.

Why is Touch a Sensitive Area?

Providers should remember that a high percentage of individuals in the general population, especially women, have been molested, raped, or otherwise violated, often by a person of trust. One multi-state and territory study showed that 18.5% of women report a history of attempted or completed nonconsensual sex (Smith & Breiding, 2011). The percentage of women violated sexually may be higher in populations with chronic illness (Santaularia et al., 2014; Smith & Breiding, 2011).

Listen to Dr. Moss explain touch © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Obtaining Assent from Children

They respect children's rights and seek their assent before receiving biofeedback training or participating in research.

Consent means that the consenting person understands what they are getting into and its implications, and that they are making a choice that they control and have authority for. Assent more simply means that the person is willing to participate in something, without necessarily understanding the essential details of what they are getting into or all its consequences. If a child or person with cognitive impairments is not able to provide consent, then someone who has authority for the child or person provides consent. The child or mentally impaired person, however, is still asked for their assent. This is not mere politeness but is also practically useful because it helps to engage the child's active participation in the experiment.

Respect for Dignity and Rights

They respect the dignity and rights of all individuals and never discriminate against or refuse services to clients because of their sex, sexual orientation, sexual identity, race, religion, disability, or national origin.

Biofeedback Equipment Selection

Wherever possible, purchase equipment that is FDA approved. The major equipment manufacturers expend thousands of hours and go to considerable expense to obtain FDA approvals and to meet ISO 13485 medical device certification requirements. 'Quality first: all our products are designed and developed according to ISO 13485 and FDA requirements of quality systems' [Mind Media]. However, many small companies producing inexpensive devices do not follow these procedures. Manufacturers may have FDA waivers for some battery-operated devices.

Clinical biofeedback devices are regulated by the US Government's Food and Drug Administration (FDA). You should not use any biofeedback device for clinical applications which is not labeled as safe and effective by the FDA unless you are using it for approved research. If you are outside the US, your own government may have its own system of regulation. Each device approved by the FDA has a 'label' stating those uses which the FDA feels have been sufficiently well demonstrated to be efficacious. You must inform your clients in writing if you use the device off-label, meaning something other than uses listed with the FDA. For a complete discussion of FDA issues, including who can prescribe the use of biofeedback devices, please see the discussion at 'Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Biofeedback Equipment Labeling and Approval Issues' (Moss, 2020).

Strongest Position

Hypothetically, if you treat a patient with a diagnosed disorder using non-FDA equipment, the insurance company could demand re-payment. FDA-registered equipment should only be sold to licensed professionals. No practitioner who is not licensed for independent practice should advertise biofeedback treatment for diagnosed disorders (or provide a diagnosis on statements for submission to insurance companies) unless supervised by a licensed provider (Moss, 2020).

FDA Labeling

The FDA only labels devices for specific uses that have been strongly documented. Most biofeedback and neurofeedback devices, for example, are designated for relaxation or stress management only. Licensed practitioners can utilize equipment off-label but should be careful not to advertise off-label applications (Moss, 2020).

Infection Risk Mitigation

A neurofeedback provider applied reusable EEG sensors to the scalp of a high school wrestler with skin lesions. When questioned, the wrestler explained that the lesions were due to mat abrasion and that all the wrestlers on his team had them. Since the clinician did not disinfect the sensors in between sessions, several of her clients developed MRSA infections and sued him for malpractice. This vignette was adapted from Moss (2013).

Professionals follow the most rigorous standards of infection mitigation to protect clients and staff. Practitioners should learn and implement reasonable disinfection standards for biofeedback instruments, sensors, and office environments (Moss et al., 2019).

Listen to a mini-lecture on Infection Risk Mitigation

During a pandemic, distance training may be necessary due to the risk of community spread. Where the positivity rate is acceptably low, practitioners should adopt current Centers for Disease Control (CDC) standards for screening, distancing, masking, and cleaning surfaces. Graphic © Kinga/Shutterstock.com.

Biofeedback providers may underestimate their risk of transmitting infection to their clients and may lack basic knowledge about risk mitigation strategies. Whereas clinicians may assume that infection risk is low since biofeedback is noninvasive, handshakes, reclining chairs, cables, and sensors can easily transfer infectious organisms to clients. Moreover, over-abrasion in SEMG biofeedback and neurofeedback can expose sensors to client blood (Spaulding semi-critical classification), and inserted pelvic and rectal sensors expose sensors to tissue (Spaulding critical classification). This ubiquitous problem is called common vehicle transmission. Risk mitigation involves three strategies: handwashing and drying, disinfection of surfaces clients will contact, and disinfection or sterilization of sensors and cables. (Hagedorn, 2014).

A comprehensive prevention strategy includes handwashing by both the clinician and client. When the skin is not visibly soiled, alcohol-based products may be superior to antiseptic soap and water in terms of effectiveness, minimizing skin dehydration, and ease of use. However, soap and water are superior to alcohol-based products in removing spores from Clostridium difficile (C. diff; Sullivan & Altman, 2008).

Clinicians should disinfect chair or recliner surfaces using wipes impregnated with biocidal agents that control bacteria and spores like Freshnit or Virusolve instead of ineffective 20% isopropyl alcohol (Hagedorn, 2014).

When equipment like precious metal electrodes and cables can be damaged by heat, liquid chemical sterilization should be used before and after each training session. Low-level disinfectants like Protex Disinfectant Spray can destroy a broad spectrum of bacteria, viruses, and fungi, including herpes, MRSA, and VRE.

The risk of infection transmission can be reduced by using disposable sensors, and in the case of rectal or vaginal sensors, using dedicated sensors that belong to the client (Sullivan & Altman, 2008).

Best Telehealth Practices

The Covid-19 pandemic has increased the delivery of biofeedback and neurofeedback services via telehealth both within and across state lines. Dr. Moss provides an overview of best telehealth practices © Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Professional Relationships

Providers build partnerships with colleagues in diverse professions based on respect for their competencies. These networks allow allied providers to combine their expertise and resources when treating clients, conducting research, and educating the public, legislators, and third-party payers.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Partnerships

They should only treat medical disorders with biofeedback if their clients have been medically evaluated or are under the care of a physician. They should collaborate with the physicians who treat their clients by explaining their treatment strategy and goals, providing regular progress reports supported by physiological data, and advising physicians on how biofeedback and adjunctive procedures can interact with medication. For example, relaxation training may reduce a diabetic patient's insulin requirement, resulting in a functional overdose that could cause hypoglycemia and coma. This collaborative approach can promote sharing vital information, physician encouragement of their clients to continue biofeedback, and future referrals.

Providers respect the importance of client-physician relationships and avoid the appearance of interfering with medical treatment. If clients express the desire to adjust or eliminate medication as their symptoms improve, providers should withhold their opinion and encourage clients to discuss this issue with their physician.

They maintain good relationships with their colleagues by striving to be objective and compassionate in their judgments of others and showing respect for different perspectives. They collaborate with allied professionals to increase understanding and pursue goals they could not achieve alone.

They recognize that multiple relationships can threaten their bond with those they serve and risk the exploitation of both parties. They avoid dual relationships with clients and never exploit clients, students, supervisees, employees, research participants, or third-party payers.

For example, practitioners should never treat their spouses, and supervisors should never treat their employees. When providers question their objectivity, they should seek guidance from colleagues.

Research with Humans and Animals

Professionals conduct research to increase our understanding of human behavior, improve the human condition, and advance science. They believe that human and animal welfare must be their paramount concern when conducting research and strive to protect them. They adhere to their professions' applicable legal statutes and standards, consider alternative research methods that minimize participant discomfort and deception and reduce the number of animal subjects. They cooperate completely with institutional review boards and institutional animal care and use committees that regulate human and animal research.

Their research reports completely describe their methodology and statistical analysis, accurately summarize experimental findings, and satisfy conventional scientific criteria. Descriptions of clinical procedures are factual and avoid self-promotion. They explicitly describe the limitations of their studies and exercise caution in drawing conclusions from their data. They may supplement probability testing with estimates of effect size and confidence intervals to better communicate the research significance of their results.

Each researcher is responsible for ensuring that research adheres to legal and professional ethical standards and that collaborators, assistants, students, and employees treat participants ethically. All members of a research team are personally responsible for their ethical conduct.

Researchers protect information obtained from participants through procedures that ensure anonymity and confidentiality. They protect anonymity by identifying participant records using codes. They guard confidentiality by securely storing data, only using data as promised to the participants, and only reporting aggregate results. They explain these precautions when they obtain informed consent.

They inform prospective subjects about all aspects of a study that might influence their decision to participate, including potential risks and benefits, and encourage questions when they obtain informed consent. Their responsibility to protect participants increases with the risk of harm. If participants are injured by research, they are responsible for providing effective care to make these individuals "whole." They never employ research procedures that are likely to cause severe and lasting harm to participants.

They respect an individual's right to refuse to participate in research or to end their participation at any time and never coercively use compensation. They are especially vigilant in protecting this freedom when the researcher can directly influence participants' lives.

They accurately describe the results of their research and disclose the limitations of their methodology in their publications. They give appropriate credit to all who contribute to publications.

In animal research, the animals' treatment should adhere to Federal Regulations (Humane care and use of animals A 343401) and the American Psychological Association Guidelines for Ethical Conduct in the Care and Use of Nonhuman Animals in Research (2022).

Adherence to Professional Standards

Providers adhere to all applicable national, state, and municipal laws, the rules and regulations of licensing and certification bodies, and the ethics policies of professional organizations. The International Society for Neurotherapy and Research and the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback have each developed extensive ethical codes. They consult these standards in their daily practice.

Ethics Complaint Procedures

Providers who have knowledge of an ethical violation by another provider first determine whether there is sufficient evidence to make a complaint, consider whether they can productively resolve the violation by bringing it to the offending colleague's attention, evaluate any conflicts of interest that might affect their judgment, and then decide whether to file a formal complaint. If they decide to file an ethics complaint, they contact the professional associations to which the offending colleague belongs, the certification bodies that recognize that professional, and the colleague's licensing authority. If the offense is illegal, they contact law enforcement.

Biofeedback Certification International Alliance (BCIA)

BCIA is the leader in setting certification standards for the delivery of biofeedback services and operates a worldwide certification program.

1. BCIA is recognized by major medical organizations and government agencies, including the Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, U.S. Veterans Affairs, and the National Institute of Mental Health. These organizations want their patients to be cared for by professional practitioners who have met rigorous standards.

2. BCIA biofeedback certificants have met demanding educational, training, and ethical requirements. To initially certify, applicants must complete coursework that covers the complete didactic blueprint, mentored clinical training, and pass a national standardized exam.

3. BCIA certification is one of only four credentials (BCB, BCB-HRV, BCN, and PMDB) accredited by the National Commission for Certifying Agencies (NCCA). The NCCA was established by the Institute of Credentialing Excellence. It is the accreditation body of the Institute, which sets the national benchmarks for credentialing. Its reputation is so strong that NCCA has accredited Boards in such disciplines as nursing, counseling, dietetics, personal training, and financial planning.

4. BCIA's biofeedback certification exam adheres to the highest psychometric standards. We painstakingly evaluate and revise its exam on a regular basis. Several independent experts, who include clinicians and the most experienced educators in our field, regularly review exam items to ensure that they represent key blueprint concepts, are sourced to its suggested reading list, and are psychometrically sound. BCIA regularly replaces outdated exam questions with new ones that are contributed by biofeedback authorities and then validated by our certificants.

5. BCIA requires that its certificants adhere to one of the strongest ethical codes in our field. In addition, we require that its certificants complete 3 hours of ethics continuing education when they renew their certification. BCIA's rigorous ethical standards are one of the many reasons that its international colleagues have chosen BCIA biofeedback certification.

6. BCIA's Board of Directors consists of clinicians, educators, and researchers who have guided the development of biofeedback. BCIA's Board includes leaders of the three major international membership organizations who have contributed decades of service to our field (Why Choose BCIA Biofeedback Certification?).

Certification Programs

BCIA has four certification programs: Biofeedback Certification, HRV Biofeedback, Neurofeedback Certification, and Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction Biofeedback Certification.

Individuals certified in Biofeedback have demonstrated entry-level competence in biofeedback modalities, including EMG, HRV, respiration, skin conductance, and temperature.

Individuals certified in HRV Biofeedback have demonstrated entry-level competence in ECG, EMG, PPG, and respiration modalities.

Individuals exclusively certified in Neurofeedback, commonly called EEG Biofeedback, are certified to utilize only that specialty modality.

The Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction Biofeedback Certification is only for licensed providers wishing to use biofeedback and behavioral interventions to treat elimination disorders and pelvic pain within their scope of practice.

All certification programs require strict adherence to the Professional Standards and Ethical Principles of Biofeedback.

All certification programs are based on: prerequisite educational degrees (except for the Technician certification), proof of human anatomy/physiology and human biology coursework, didactic course work that is based on the Blueprint of Knowledge statements that cover the fundamental science, history, and theory of biofeedback specific to that certification program, clinical training or mentoring to learn the application of skills, and a certification exam.

Certification is no substitute for a state-sanctioned license. BCIA's certificants must carry an appropriate license/credential valid in the state of practice in a BCIA-approved health care field when treating a medical or psychological disorder. If unlicensed, the certificant must work under appropriate supervision (Shaffer et al., 2012). Your biofeedback or neurofeedback provider's licensing body or supervisor has legal jurisdiction over their clinical practice (Crawford, 2013).

Certifications are valid for a set period: 4 years for Biofeedback, HRV Biofeedback, Neurofeedback, and Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction Biofeedback. Recertification is granted upon application, payment of fees, documentation of accredited continuing education specific to the Blueprint, and adherence to the Professional Standards and Ethical Principles of Biofeedback.

In 2012, BCIA created a Certificate of Completion in Heart Rate Variability (HRV) Biofeedback requiring 15 hours of didactic HRV biofeedback instruction, 3 hours over professional conduct, and a passing score on a nationally standardized exam (Crawford, 2013). A certificate of completion is not a certification. This credential attests to completing an approved didactic workshop based on BCIA's Blueprint and passing an exam over its content.

How does certification differ from licensure?

Certification means that a non-governmental organization like BCIA has recognized that an individual has satisfied its requirements and demonstrated at least entry-level competence in a field like biofeedback. Certification is not a license to practice and does not authorize professionals to provide services they could not legally offer before certification (Shaffer, Crawford, & Moss, 2012). Licensure means that a state agency has authorized an individual to use a professional designation, like Psychologist, and provide services specified by the state's practice act for a fee.

Individuals who engage in diagnosing or treating disorders outside their legal scope of practice may face state prosecution.

Emerging Ethical Issues in the Digital Age

The biofeedback field is changing faster than at any point in its history. Smartphones, wearables, telehealth platforms, and artificial intelligence are transforming how we deliver services and how clients interact with their own physiological data. These technologies bring tremendous opportunities, but they also create ethical challenges that previous generations of practitioners never had to consider. This section explores the emerging issues you will face as you build your career in this rapidly evolving landscape.

Your Client's Digital Health Footprint: Privacy Beyond the Clinic

Here is something that might surprise you: the health information your clients generate outside your office may be far less protected than what you record during sessions. When a client uses a heart rate variability app on their phone, tracks their breathing with a smartwatch, or logs stress levels in a wellness application, they are creating what researchers call a digital health footprint. This collection of digital traces can reveal remarkably detailed health information when pieced together, yet much of it falls completely outside traditional privacy protections (Grande et al., 2020).

You are probably familiar with HIPAA, the federal framework that governs how healthcare providers handle protected health information. What you may not realize is that HIPAA only applies to "covered entities" like hospitals, insurance companies, and healthcare providers, along with their business associates. Many of the consumer apps and wearable devices your clients use operate entirely outside this framework, even when the data they collect is clearly health-relevant (Grande et al., 2020). That calming app your anxious client uses every night? The HRV tracker they wear to monitor stress? The biofeedback game they play at home between sessions? None of that data necessarily has HIPAA protection.

The Data Broker Problem

The situation gets more complicated when you consider data brokers, businesses that collect, aggregate, and sell personal information. Your client's wellness app data might be sold to advertisers, insurance companies, or employers without your client ever realizing it. The "consent" they gave was probably buried in a lengthy terms-of-service agreement that nobody actually reads. When a client clicks "I agree" to use an app you recommended, they may be agreeing to data sharing arrangements that could affect their insurance premiums, employment prospects, or targeted advertising for years to come (Grande et al., 2020).

What does this mean for your practice? When you recommend apps, devices, or platforms to clients, you have an ethical obligation to explain, in plain language, what data will be collected, who might receive that data, how long it will be stored, and what options exist for opting out. Never imply that "health app data" receives the same protection as your clinical records. Your clients deserve to make truly informed decisions about their digital health footprint.

When Breaches Happen: Your Responsibility to Clients

Imagine this scenario: You have been recommending a popular HRV training app to your clients for stress management. One morning, you learn the company experienced a data breach, and hackers accessed user accounts including names, email addresses, and detailed physiological data. What are your obligations?

Because consumer health tools often fall outside traditional medical privacy rules, regulators increasingly rely on specialized frameworks to address breaches. The Federal Trade Commission's Health Breach Notification Rule applies to certain vendors and personal health record contexts, and it has become a central compliance issue for biofeedback educators and practitioners who integrate third-party apps into their work (Federal Trade Commission, 2024).

The ethical lesson here extends beyond legal compliance. Breach readiness is not just an IT concern; it is a client protection obligation. If a tool you recommended experiences a breach, your clients will look to you for guidance. Being prepared means knowing what information was involved, being able to explain what happened in terms clients can understand, and helping them take appropriate protective steps. This transparency supports the fidelity and trust that form the foundation of professional ethics codes in biofeedback practice (AAPB, n.d.).

Cybersecurity: No Longer Someone Else's Problem

Let us be honest: many biofeedback practitioners entered this field because they wanted to help people regulate their physiology, not because they dreamed of becoming IT security experts. But modern biofeedback practice increasingly involves electronic protected health information (ePHI) and networked systems. If you create, store, or transmit sensitive physiological data, you assume responsibility for reasonable safeguards (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.).

Think about all the ways client data flows through your practice. Session recordings stored on your computer. Assessment results emailed to referring physicians. Training data synced to cloud platforms. Remote sessions conducted over video conferencing. Each of these creates potential vulnerabilities that did not exist when biofeedback meant a client sitting in your office connected to a standalone device with no internet connection.

A risk analysis is a structured process for identifying threats, vulnerabilities, and the safeguards needed to protect client information. It is not a one-time exercise but an ongoing responsibility that should be revisited whenever you add new technology to your practice (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.).

The key concept is that "reasonable security" is dynamic. Remote sessions, cloud storage, and device syncing all expand what security professionals call your "attack surface," meaning the number of potential entry points for unauthorized access. This makes data minimization, access controls, and incident planning more ethically important than ever (Tully et al., 2020).

Telehealth Biofeedback: New Setting, Amplified Duties

The expansion of telehealth, accelerated dramatically by the COVID-19 pandemic, has fundamentally changed how many practitioners deliver biofeedback services. Remote training expands access for clients who cannot travel to your office, but it also raises questions about professional boundaries and jurisdiction.

Think of telepsychology competence as traditional clinical competence plus a new layer of technology-specific skills. You still need everything you learned about biofeedback assessment, protocol selection, and client rapport. But now you also need competence in platform selection, privacy settings, emergency planning for remote sessions, and maintaining communication clarity when technology mediates your interactions (American Psychological Association, 2013).

Recent guidance from professional organizations emphasizes practical resources for documentation, risk management, and service delivery decisions in telehealth contexts (Perle et al., 2025). Rather than thinking of telehealth as creating entirely new ethical rules, consider it a setting that amplifies your classic duties. Confidentiality still matters, but now you must consider whether your client's family members can overhear sessions, whether the platform encrypts transmissions, and whether session recordings are stored securely. Competence still matters, but now it includes knowing how to troubleshoot connection problems, adapt protocols for home equipment, and recognize when remote delivery is not appropriate for a particular client.

Wearables and the Question of Measurement Honesty

Consumer wearables have made biofeedback more accessible than ever. Your clients can track heart rate variability on their smartwatches, monitor breathing patterns with chest straps, and practice stress management using smartphone apps. But this accessibility comes with an ethical responsibility that we might call "measurement honesty."

Here is the problem: because the numbers are digital, clients often assume they are precise. A heart rate of 72 beats per minute displayed on a screen feels authoritative in a way that a rough estimate never would. But consumer-grade optical sensing, often using photoplethysmography (PPG), can perform quite differently across contexts. Movement affects accuracy. Rapid physiological changes can confuse algorithms. Different devices use different processing methods that may not be comparable (Icenhower et al., 2025).

This becomes an ethics issue when you overstate what a metric means, treat noisy data as if it were diagnostic-quality information, or fail to explain the limitations of consumer devices. The validity of a measurement, meaning whether it actually reflects what it claims to measure, and its reliability, meaning whether it produces consistent results across time and conditions, matter enormously for the conclusions your clients draw from their data.

A Simple Principle for Wearable Data

Feedback is only therapeutic when clients can trust that the signal is fit for its intended purpose. This means being honest about what consumer devices can and cannot tell us. A smartwatch HRV reading can be useful for noticing general trends and patterns over time. It should not be treated as equivalent to a clinical-grade ECG assessment. When uncertainty exists, explain it clearly so clients do not confuse "tracking" with "diagnosis."

Equity and Bias in Sensing Technologies

A related issue that is gaining attention involves potential bias in how sensing technologies perform across different populations. Some research has raised concerns that optical sensors may not work equally well for all skin tones, which could produce inequitable outcomes if biofeedback recommendations rely heavily on consumer sensors.

Even when individual studies find limited effects for a given device and protocol, the broader principle remains important: performance can vary by hardware, firmware, activity context, and population characteristics. Ethical practice requires cautious interpretation and ongoing attention to whether your tools work well for all your clients, rather than assuming that a "neutral" device produces equally valid results for everyone (Icenhower et al., 2025).

This connects to broader concerns about health equity, the principle that everyone should have fair opportunities for optimal health outcomes. An apparently neutral device can still create unequal burdens if some clients must purchase expensive upgrades to get stable readings, or if certain clients systematically receive noisier feedback that undermines their learning and self-efficacy.

Artificial Intelligence: The Black Box Problem

Biofeedback platforms increasingly incorporate artificial intelligence (AI) for tasks like artifact detection, trend prediction, coaching prompts, and personalized protocol recommendations. AI can make sophisticated analysis available to practitioners who lack specialized training, potentially improving care. But it also introduces a significant ethical challenge: opacity.

When an AI system operates as a black box, neither you nor your client can easily explain why it produced a particular recommendation. The algorithm learned patterns from training data, but the specific reasoning behind any individual output may be impossible to articulate. This creates problems for accountability and informed consent. How can clients make informed decisions about their care if neither they nor their provider can explain why the system is recommending a particular approach? (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023).

Before adopting any AI-powered biofeedback tool, work through these questions: What exactly does the algorithm do? What data does it use to make recommendations? What outcomes is it optimizing for? What human oversight exists to catch errors? Based on your answers, decide what information clients need to make an informed choice about using the tool (World Health Organization, 2021; National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2023).

Software as a Medical Product: Recognizing Scope Creep

Some biofeedback-related software exists in an ambiguous zone between wellness tool and regulated medical device. This ambiguity creates opportunities for scope creep, where a tool's marketing and functionality gradually imply medical authority even when the evidence base or regulatory oversight is limited.

Consider how this might unfold. A developer creates an app for "stress awareness" using basic HRV metrics. Over time, the app adds features: it starts labeling readings as "normal" or "concerning," suggests that certain patterns indicate specific conditions, and offers clinical decision support recommendations that edge into diagnostic territory. At what point does a wellness tool become something that should be regulated by the FDA? (Food and Drug Administration, 2022).

This matters ethically because clients often interpret authoritative language as medical validation. When an app tells them their "stress level is dangerously high" or their "nervous system is dysregulated," they may not realize they are receiving outputs from an unvalidated algorithm rather than a clinical assessment. Your responsibility includes recognizing when tools exceed their appropriate scope, maintaining discipline about claims, making appropriate referrals, and documenting accurately what any tool can and cannot do.

Conflicts of Interest in the App Economy

As biofeedback moves into apps, subscriptions, and device ecosystems, conflicts of interest become easier to create and harder for clients to detect. A conflict exists whenever your financial incentives could reasonably be perceived as influencing your clinical recommendations (Refolo et al., 2022).

Think about the ways this might arise. Perhaps a wearable company offers you affiliate commissions for recommending their device. Maybe you receive free access to premium software features in exchange for steering clients toward a particular platform. You might have invested in a biofeedback startup or developed your own app that competes with alternatives you could recommend.

Disclosure is essential but not sufficient. Even when you tell clients about financial relationships, they may not fully appreciate how incentives could shape recommendations. Ethical practice requires separating your clinical judgment from product marketing and being able to document why a recommendation is clinically appropriate independent of any financial relationship.

Navigating a Patchwork of Privacy Laws

Privacy regulation in the United States is becoming increasingly complex, with different rules applying depending on the state, the type of data, and the nature of the entity collecting it. Some states have enacted specific protections for consumer health data that go well beyond federal requirements and may define health-related information very broadly.

Washington State's My Health My Data Act, for example, creates obligations around collection, sharing, and consent for health data that apply even to entities that are not traditional healthcare providers (Washington State Legislature, 2023). If you practice in Washington, or if you have clients in Washington using apps and platforms you recommended, these rules may apply to you in ways that HIPAA does not.

The practical takeaway is that "privacy compliance" is becoming jurisdiction-dependent and platform-dependent. Rather than relying on a single federal framework to cover all your biofeedback-related tools, adopt conservative best practices: minimize the data you collect, use clear consent processes, conduct due diligence on vendors before recommending them, and stay informed about evolving regulations in the jurisdictions where you practice.

Glossary

anonymity: protection of a client's identity.

artificial intelligence (AI): a set of computational methods that learn patterns from data to generate predictions, classifications, or automated decisions.

BCIA: the Biofeedback Certification International Alliance.

black box (opacity): a situation where a computational model's internal reasoning is not readily interpretable to users, limiting transparency and accountability.

certificant: an individual who has been certified by BCIA.

certificate of completion: recognition by BCIA that an applicant has completed an approved didactic workshop based on BCIA's Blueprint and passed an exam over its content.

certification: BCIA recognition that an applicant has met its requirements for entry-level competence in providing biofeedback services.

chronic inflammatory response syndrome (CIRS): a condition caused by exposure to biotoxins, leading to chronic inflammation and multi-system symptoms.

client: a recipient of biofeedback services.

clinical decision support: software functions that provide patient-specific assessments or recommendations intended to support clinical decision-making.

common vehicle transmission: the transfer of infectious organisms by equipment, including cables and sensors.

competence: level of proficiency.

confidentiality: a client's right to keep personal information private.

conflict of interest: a circumstance in which secondary interests, often financial, could reasonably be perceived to influence professional judgment.

consumer health data: health-related information collected in consumer contexts, often defined broadly in emerging state laws and not limited to clinical records.

continuing education: organized learning experiences undertaken after a credential has been earned to ensure up-to-date knowledge.

cybersecurity: the protection of systems and data from unauthorized access, disruption, or misuse.

data broker: a business that collects, aggregates, and sells personal data, sometimes enabling health-relevant inferences.

diffuse encephalopathy: a condition characterized by widespread brain dysfunction, often resulting from various causes such as infections, toxins, metabolic imbalances, or systemic diseases. It typically manifests as altered mental status, confusion, lethargy, and other cognitive impairments. Diagnosis usually involves clinical assessment and imaging studies like EEG or MRI, and treatment focuses on addressing the underlying cause to alleviate the symptoms.

digital health footprint: the collection of digital traces that can reveal health-relevant information when aggregated across sources.

dual relationship (also called multiple relationship): a situation where a healthcare provider and patient share multiple roles. For example, when a client is also an employee.

efficacy: effectiveness.

electronic protected health information (ePHI): health information stored or transmitted electronically within HIPAA-regulated contexts.

ethics: the branch of philosophy that deals with moral issues.

functional overdose: a drug overdose that can occur when biofeedback training reduces a patient's requirement for a drug. For example, biofeedback training may lower a patient's blood pressure to the extent that the prescribed dose may produce hypotension and fainting.

Health Breach Notification Rule: a U.S. FTC rule requiring notifications for certain breaches involving identifiable health information in covered consumer contexts.

health equity: fairness in health opportunities and outcomes, including avoiding systematic disadvantages created by technology design or access barriers.

HIPAA: the U.S. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act framework governing privacy and security for covered entities and business associates.

informed consent: a process ensuring a client understands material risks, benefits, alternatives, and limitations before agreeing to services or data use.

licensure: legal permission granted to a professional to practice a profession.

mentorship: a relationship between a mentor and candidate that promotes the development of skill, knowledge, responsibility, and ethical standards in the practice of biofeedback.

PANS/PANDAS: pediatric conditions involving sudden onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms following an infection, which are subtypes of autoimmune encephalitis.

photoplethysmography (PPG): an optical sensing method that estimates cardiovascular signals from light absorption changes in tissue.

provider: the professional who supervises biofeedback training.

reliability: the consistency of a measurement across time or conditions.

risk analysis: a structured process for identifying threats and vulnerabilities and documenting safeguards to reduce risk.

scope creep: gradual expansion of a tool's implied purpose, such as shifting from wellness tracking toward diagnostic or treatment claims.

scope of practice: the services a provider may legally offer under their license or supervisor's license.

supervision: the provision of guidance for clinical practice for qualified health professionals by a more experienced health professional who assumes legal responsibility and liability for the quality of the services provided.

telepsychology: psychological services delivered using telecommunication technologies, requiring adapted competence, privacy, and risk management practices.

validity: the degree to which a measure reflects what it claims to measure.

Test Yourself

Click on the ClassMarker logo to take 10-question tests over this unit without an exam password.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Visit the BioSource Software Website

BioSource Software offers Human Physiology, which satisfies BCIA's Human Anatomy and Physiology requirement, and Biofeedback100, which provides extensive multiple-choice testing over BCIA's Biofeedback Blueprint.

Assignment

Based on your own clinical experience, what are the hardest ethical decisions you've made in biofeedback practice?

References

American Psychological Association. (2013). Guidelines for the practice of telepsychology. American Psychologist, 68(9), 791-800. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035001

Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. (n.d.). Code of ethics.

Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. (1994). Clinical efficacy and cost effectiveness of biofeedback therapy: Guidelines for third party reimbursement (2nd ed.). Author.

Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. (1995). Clinical applications of biofeedback and applied psychophysiology: A series of white papers prepared in the public interest by AAPB. Author.

Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. (2003). Ethical principles of applied psychophysiology and biofeedback (4th revision). Author.

Biofeedback Certification International Alliance. (n.d.). Professional standards and ethical principles.

Biofeedback Certification International Alliance. (2011). What is certification?

Biofeedback Certification International Alliance. (2015). Why choose BCIA biofeedback certification?

Biofeedback Certification International Alliance. (2016). Professional standards and ethical principles (9th rev.).

Crawford, J. (2013). What's new with BCIA? Biofeedback, 41(3), 85-87. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-41.3.07

Crawford, J., & Shaffer, F. (2014). What BCIA learned from Bob Dylan. Biofeedback, 42(1), 9-11. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-42.1.05

Federal Trade Commission. (2024). Statement of policy regarding the Health Breach Notification Rule.

Food and Drug Administration. (2022). Clinical decision support software: Guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff.

Food and Drug Administration. (2022). Mobile medical applications: Guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff.

Grande, D., Luna Marti, X., Feuerstein-Simon, R., Merchant, R. M., Asch, D. A., Lewson, A., & Cannuscio, C. C. (2020). Health policy and privacy challenges associated with digital technology. JAMA Network Open, 3(7), e208285. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8285

Hagedorn, D. (2014). Infection risk mitigation for biofeedback providers. Biofeedback, 42(3), 93-95. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-42.3.06

Hammond, D. C., Bodenhamer-Davis, G., Gluck, G., Stokes, D., Harper, S. H., Trudeau, D., MacDonald, M., Lunt, J., & Kirk, L. (2011). Standards of practice for neurofeedback and neurotherapy: A position paper of the International Society for Neurofeedback & Research. Journal of Neurotherapy, 15(1), 54-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874208.2010.545760

Hopkins, B. (2013). Legal aspects of counseling: What you don't know might hurt you. Workshop presented at the Biofeedback Society of Texas conference, Austin, Texas.

Humane care and use of animals (A 343401) (Federal Regulations).

Icenhower, A. L., Murphy, C. M., Brooks, A. K., & Fanning, J. (2025). Investigating the accuracy of Garmin PPG sensors on differing skin types based on the Fitzpatrick scale: Cross-sectional comparison study. Frontiers in Digital Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2025.1553565

Moss, D. (2013). Professional conduct in biofeedback and neurofeedback. Workshop presented at the International Society for Neurofeedback and Research conference, Dallas, Texas.

Moss, D. (2020). Professional conduct in biofeedback and neurofeedback. BCIA Webinar.

Moss, D., Hagedorn, D., Combatalade, D., & Neblett, R. (2019). A guide to normal values for biofeedback. In D. Moss & F. Shaffer (Eds.), Physiological recording technology and applications in biofeedback and neurofeedback. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2023). AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) (NIST AI 100-1).

Perle, J. G., Smith, K. L., & Pennington, M. L. (2025). A compendium for the 2024 APA Guidelines for the Practice of Telepsychology: Guideline applications and resources. American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001579

Refolo, P., Sacchini, D., De Nardo, F., & Sanches, M. (2022). Ethics of digital therapeutics (DTx). European Journal of Public Health, 32(Supplement_3), ckac130.217. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckac130.217

Regulations for the protection of human research subjects (45 CFR46 and 56 FR 28003) (Federal Regulations).

Shaffer, F., Crawford, J., & Moss, D. (2012). What is BCIA really? Biofeedback, 40(4), 133-136.

Shaffer, F., & Schwartz, M. S. (2016). Entering the field and assuring competence. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.), Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Striefel, S. (1999). Practice guidelines and standards in psychophysiological self-regulation. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Striefel, S. (2003). Professional ethics and practice standards in mind-body medicine. In D. Moss, A. McGrady, T. Davies, & I. Wickramasekera (Eds.), Handbook of mind-body medicine for primary care. Sage Publications, Inc.

Striefel, S. (2004). Practice guidelines and standards for providers of biofeedback and applied psychophysiological services. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Sullivan, L. R., & Altman, C. L. (2008). Infection control: 2008 review and update for electroneurodiagnostic technologists. American Journal of Electroneurodiagnostic Technology, 48, 140-165. PMID: 18998475

Tully, L., Boverman, J., & others. (2020). Cybersecurity considerations for telehealth and connected care. Journal of Medical Internet Research. https://doi.org/10.2196/18230

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). HIPAA Security Rule guidance material.

Washington State Legislature. (2023). My Health My Data Act (Chapter 19.373 RCW).

World Health Organization. (2021). Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health.