Skeletal Muscle Anatomy

What You Will Learn in This Unit

Have you ever wondered how Olympic sprinters generate explosive power while marathon runners sustain effort for hours? The answer lies in the remarkable diversity and organization of your skeletal muscles. This unit takes you on a journey from the microscopic world of muscle fibers to the clinical applications that will shape your biofeedback practice.

You will discover why the surface electromyograph (SEMG) measures electrical activity rather than actual muscle contraction, and why this distinction matters for clinical work. Along the way, you will explore how motor units are organized (from the tiny units controlling your eye movements to the massive ones powering your calf muscles), unpack the sliding filament theory that explains how muscles actually shorten, and learn why different types of muscle fibers determine whether you are better suited for sprinting or distance running.

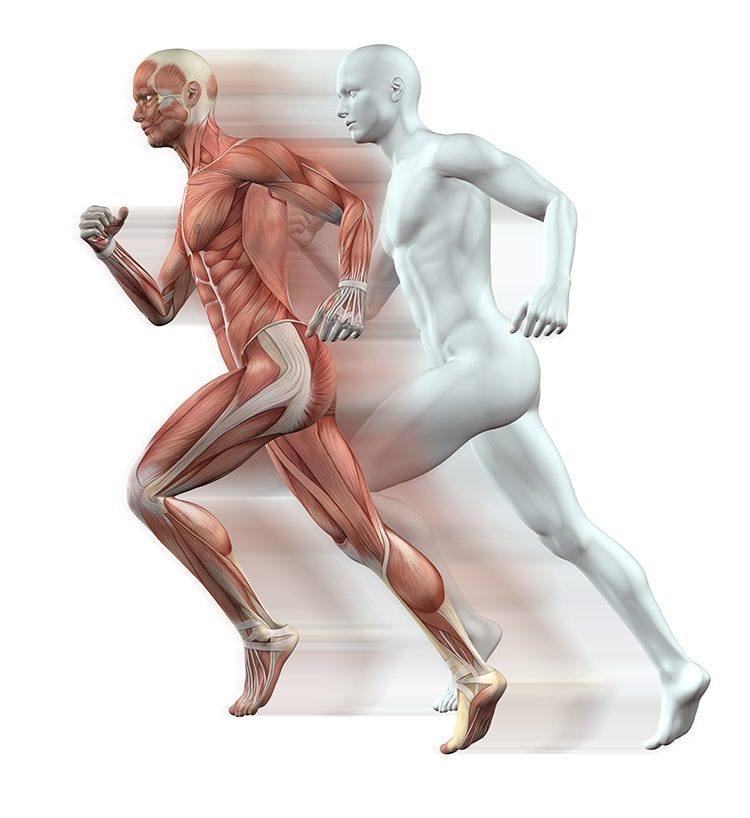

By the end of this unit, you will understand the three types of muscles in your body, how the stretch and tendon reflexes protect your musculoskeletal system, and the specific sensor placements used to monitor muscles of clinical interest. You will also discover an exciting frontier: skeletal muscles function as endocrine glands, secreting signaling molecules called exerkines that influence everything from metabolism to brain health.

This unit covers Three Types of Muscles, the Skeletal Muscle System, Motor Units, Muscle Action Potentials, Types of Skeletal Muscle Fibers, the EMG Signal, Skeletal Muscle Contraction, the Stretch Reflex, the Tendon Reflex, Muscle Action, Skeletal Muscles of Clinical Interest (Face), Skeletal Muscles of Clinical Interest (Body), and Cutting Edge topics including exerkines and genetic factors in muscle strength.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage: This unit addresses Descriptions of most commonly employed biofeedback modalities: SEMG (III-A 1-2) and Muscle anatomy and physiology; antagonistic and synergistic muscle groups (IV-A).

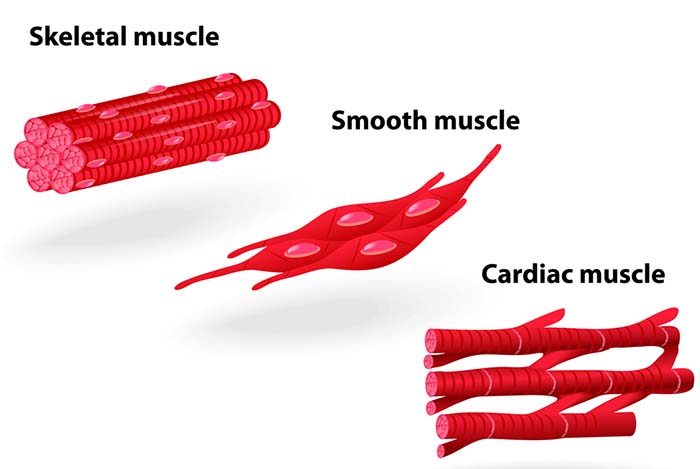

Your Body's Three Types of Muscles

The human body contains three types of muscles: skeletal, smooth, and cardiac. Each type has a distinctive structure that reflects its specialized function, and understanding these differences will help you appreciate why biofeedback techniques vary across modalities.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Three Types of Muscles

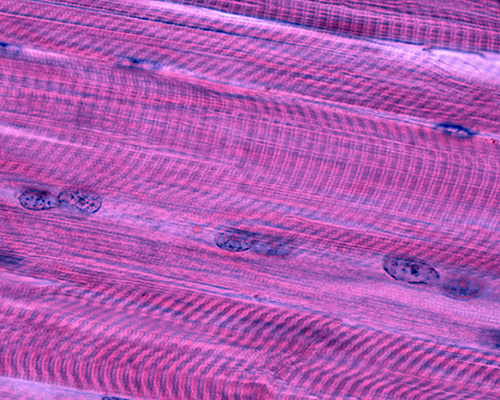

Skeletal muscles consist of cylindrical fibers that vary from a few centimeters to 30-40 cm (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). Their major functions are motion, posture, producing heat, and protection. They are multinucleated with nuclei located at the periphery. They are striated (striped) due to alternating light and dark bands visible using a light microscope. Tendons usually attach skeletal muscles to bones, which is why they are called skeletal muscles: most of them move the skeleton's bones. We control skeletal muscles voluntarily and involuntarily.

We can voluntarily control skeletal muscles through the somatic division of the peripheral nervous system because their contraction produces proprioceptive feedback. Contract a skeletal muscle like the biceps brachii and the elbow flexes. This limb movement provides the sensory information we need to adjust our arm's position consciously.

Most muscles are also controlled involuntarily. We are often unaware of the rhythmic movement of the diaphragm and the intercostal muscles that allow us to breathe. The monosynaptic stretch reflex, which maintains postural muscle tone and stabilizes limb position, also operates unconsciously.

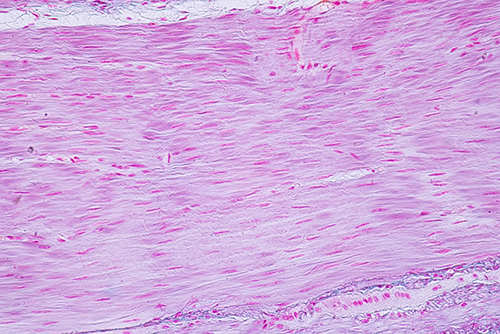

Smooth muscles comprise nonstriated fibers. They are called smooth because they do not show banding under a light microscope. They are small spindle-shaped cells with a central nucleus. In structures like the intestinal wall, gap junctions connect separate fibers to produce strong, usually involuntary, contractions. In structures without gap junctions like the iris, smooth muscle fibers contract separately like skeletal muscles. Smooth muscle functions include airway and blood vessel constriction, nutrient movement through the digestive tract, and gallbladder and urinary bladder contraction (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

There are two kinds of smooth muscle: single-unit and multiunit smooth muscle (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). Single-unit smooth muscle comprises part of the walls of small arteries and veins and the stomach, intestines, uterus, and urinary bladder. Multiunit smooth muscle is found in the walls of large arteries, airways to the lungs, the arrector pili muscles that move hair follicles, the muscle rings of the iris, and the ciliary body that focuses the lens.

Compared with skeletal muscles, smooth muscle contraction starts more gradually and persists longer. Smooth muscles can shorten and stretch more than other kinds of muscles. Smooth muscles usually operate involuntarily, and some tissues have an intrinsic rhythm (autorhythmicity). They are jointly controlled by the autonomic branch of the peripheral nervous system and the endocrine system.

Temperature Training Makes the Involuntary Voluntary

Before biofeedback training, most clients could not voluntarily control smooth muscles since their contraction does not provide sufficient feedback. For example, blood vessel dilation or constriction in the fingers produces such faint feedback that we are ordinarily unaware of these changes. Consider a client named Maria who experiences chronic cold hands due to Raynaud's phenomenon. Through temperature biofeedback, she learns to convert smooth muscle activity into a digital display or tone that allows her to voluntarily warm her fingers. This illustrates a crucial concept: we can teach clients to control involuntary processes by supplementing inadequate natural feedback.

Below is a BioGraph Infiniti display of peripheral blood flow that simultaneously shows blood volume pulse and temperature detected from the hand.

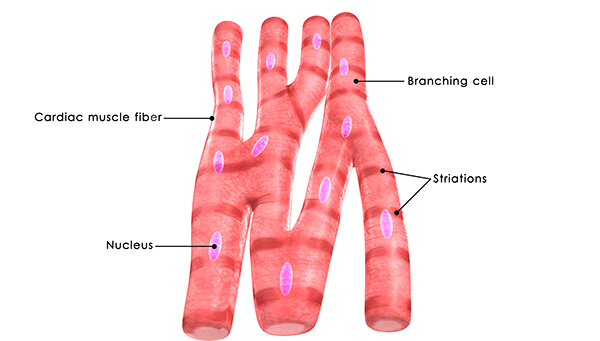

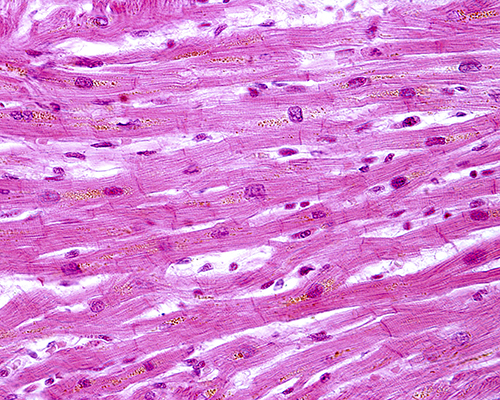

Cardiac muscle comprises most of the heart wall. Cardiac muscle fibers are branched and striated with one central nucleus (sometimes two). The ends of cardiac muscle fibers attach to intercalated discs comprising desmosomes and gap junctions. Desmosomes contribute structural integrity during forceful contractions. Gap junctions rapidly conduct muscle action potentials to ensure coordinated vigorous contractions. Cardiac muscle has crossed striations that allow the heart to eject blood from the four chambers of the heart (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Cardiac muscle fibers contain the same actin and myosin filaments, bands, zones, and Z discs as skeletal muscles. Cardiac muscle contraction lasts 10-15 times longer than skeletal muscle contraction due to the gradual movement of calcium ions into the sarcoplasm (muscle fiber cytoplasm).

Skeletal muscle contraction only occurs when a motor neuron releases acetylcholine. In contrast, the sinoatrial and atrioventricular node pacemaker cells generate the heart rhythm. The autonomic branch of the peripheral nervous system and the endocrine system jointly adjust heart rate by acting on these pacemakers.

As with smooth muscle, most patients cannot voluntarily control the heart rhythm before biofeedback training. Biofeedback supplements cardiac muscle feedback to teach patients to slow their heart rate or reduce the frequency of abnormal rhythms like premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) when they are distressed (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

The Three Muscle Types

Your body contains three distinct muscle types, each with unique characteristics. Skeletal muscles are striated, multinucleated, and under both voluntary and involuntary control. Smooth muscles are nonstriated, have single nuclei, operate involuntarily, and control internal organs and blood vessels. Cardiac muscle is striated, has one or two nuclei per cell, and contracts rhythmically under autonomic control. Biofeedback can extend voluntary control to involuntary smooth and cardiac muscles by providing external feedback that supplements inadequate natural sensory information.

Comprehension Questions: Muscle Types

- What are the three types of muscles in the human body, and what is the primary distinguishing feature of each?

- Why can we voluntarily control skeletal muscles but typically cannot voluntarily control smooth muscles without biofeedback training?

- How does biofeedback allow clients to gain voluntary control over involuntary processes like finger temperature?

- A client with Raynaud's phenomenon has chronically cold hands. Based on what you learned about smooth muscle and biofeedback, how might you explain the rationale for temperature training to this client?

The Skeletal Muscle System: From Fibers to Fascicles

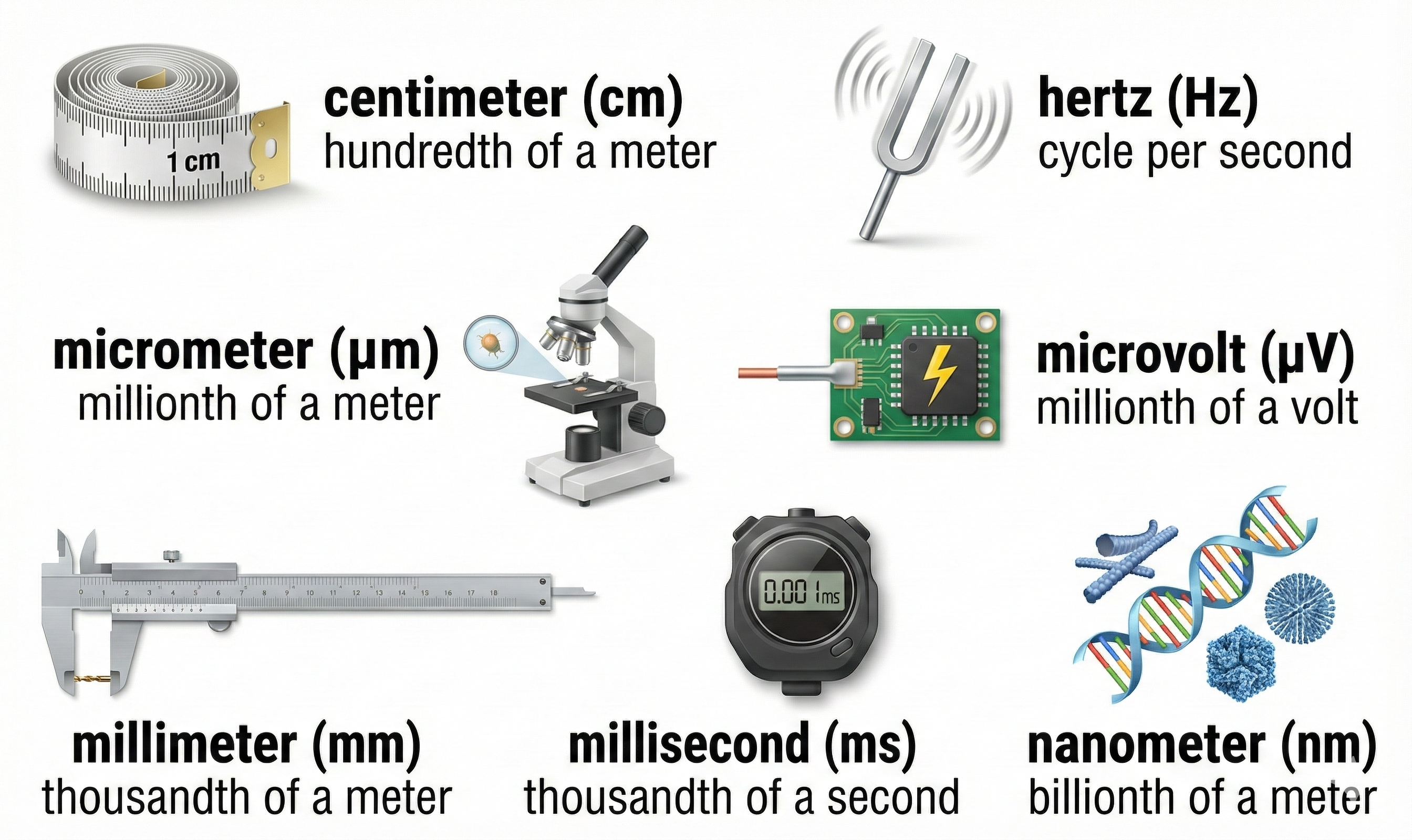

The skeletal muscle system consists of extrafusal muscle fibers and connective tissue. Important units of distance, signal frequency and strength, and time are summarized below.

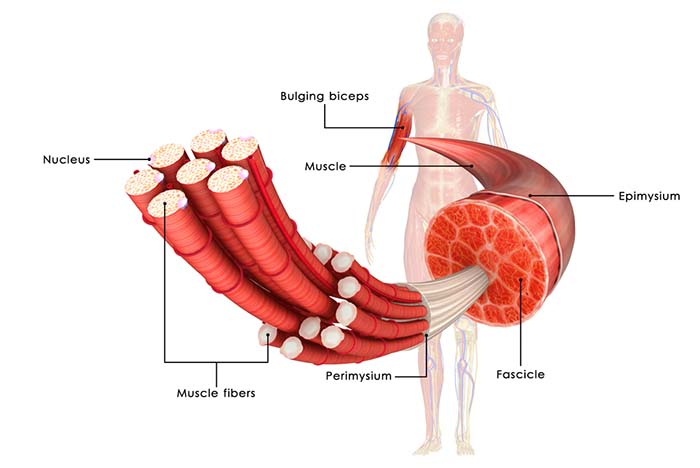

Skeletal muscle fibers are striated (striped) due to alternating light and dark bands. These fibers run from 10-100 micrometers in diameter and 10 to 30 centimeters in length. The number of skeletal muscle fibers is determined before birth, and most survive across our lifespan (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

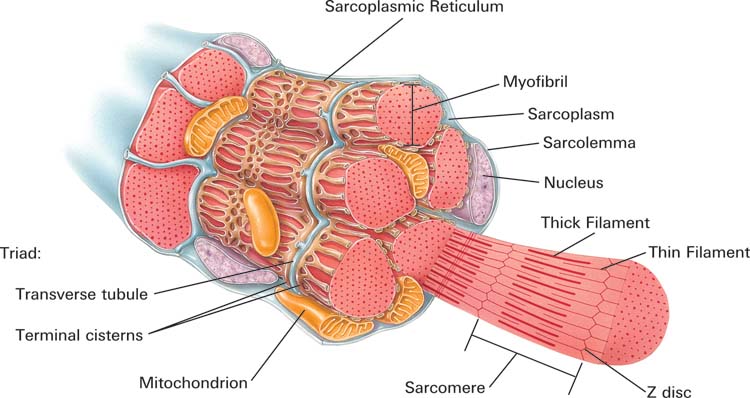

The sarcolemma, a plasma membrane, encloses individual fibers. Muscular tissue shares four properties: electrical excitability (producing muscle action potentials), contractility (contracting forcefully), extensibility (stretching), and elasticity (returning to its initial length and shape; Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Listen to a mini-lecture on Thin and Thick MyofilamentsThe Building Blocks: Filaments and Sarcomeres

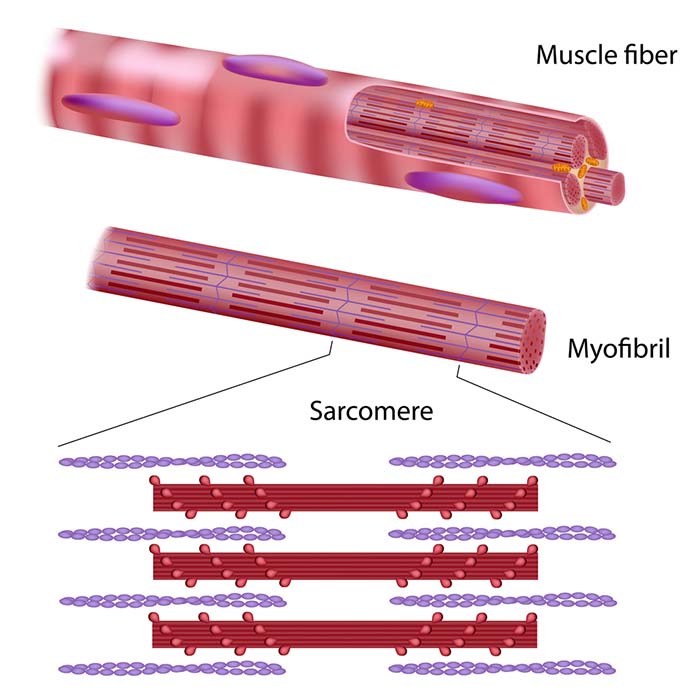

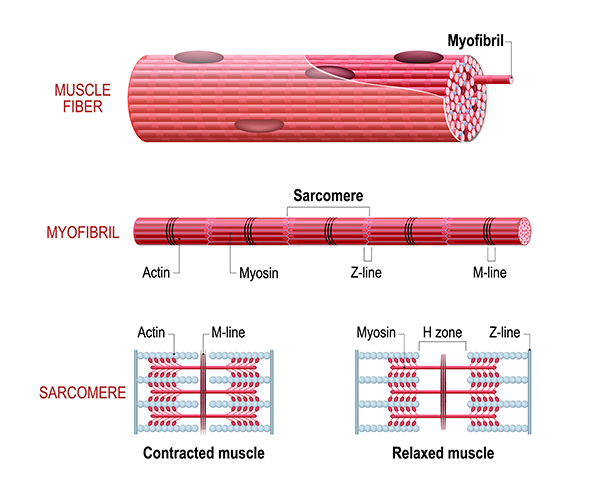

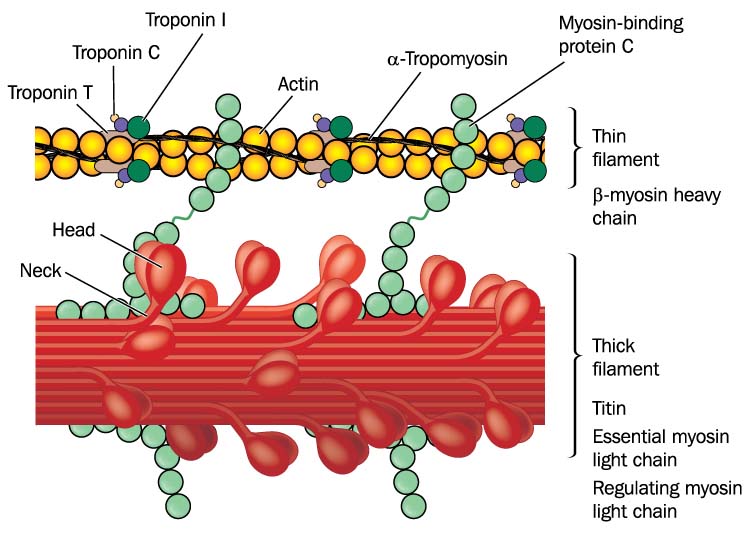

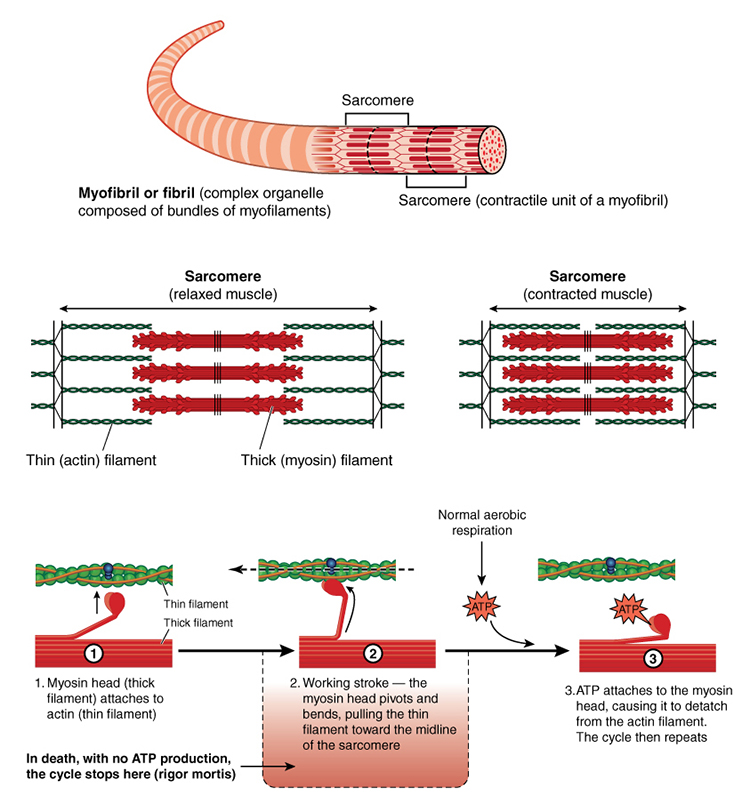

Each skeletal muscle fiber consists of cylindrical myofibrils (hundreds to thousands) that are approximately 2 micrometers in diameter and run the muscle fiber's length. Myofibrils enable muscle fibers to contract due to their overlapping thin and thick filaments, whose striations give muscle fibers a striped appearance (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

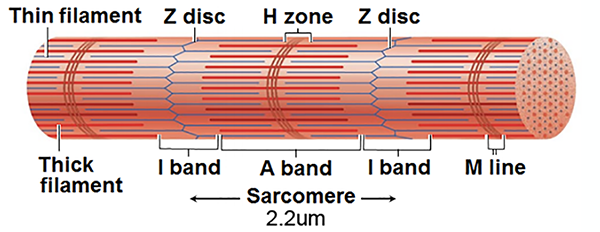

Lateral thin filaments are 8 nm in diameter, 1-2 micrometers in length, and comprise the protein actin. They span the I band and transit part of the A band. Central thick filaments are 16 nm in diameter, 1-2 micrometers in length, and comprise the protein myosin. They connect at a sarcomere's M-line (M for middle). There are two thin for every thick filament where thin and thick filaments overlap.

The filaments that comprise a myofibril do not extend a muscle fiber's length. Instead, they are stacked in compartments called sarcomeres separated by plate-shaped zones of dense protein called Z discs. Z-discs anchor thin filaments. Sarcomeres extend from Z disc to Z disc and are a muscle fiber's smallest contractile unit. Sarcomeres comprising a myofibril are aligned like boxcars (Marieb & Hoehn, 2019; Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Understanding Sarcomere Organization

A sarcomere consists of A, I, and H bands, and the M line. An A band runs the length of thick filaments and appears as a sarcomere's darker middle region. Thin and thick filaments are almost perfectly aligned and overlap at the ends of each A band. The lighter, less dense I band contains the remaining thin and no thick filaments. Z disks intersect its center. The interleaving of dark A and light I bands produces the banding visible in myofibrils and skeletal muscle fibers (Marieb & Hoehn, 2019; Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

At the center of each A band is a thin H band comprising only thick filaments. The proteins that connect these filaments at the middle of the H band create the M line.

Myofibril and Sarcomere Elasticity

Titin, a structural protein also called connectin, links a Z disc (also called Z line) to the M line in the center of a sarcomere to stabilize the thick filament's position. The segment of the titin molecule attached to the Z disc can stretch more than four times its resting length.

This ability to stretch may explain a myofibril's elasticity and a sarcomere's ability to return to its resting length after shortening or lengthening. It also clarifies how an A band can maintain its central position within a sarcomere (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Protein Connections: alpha-Actinin and Myomesin

The structural protein alpha-actinin is a component of Z discs that connects actin molecules of thin filaments to titin. Myomesin molecules form the M line at the center of a sarcomere. The M lines' proteins also attach to titin and link adjacent thick filaments.

How Skeletal Muscles Generate Force

Muscle fibers generate force by pulling Z discs together, shortening the sarcomeres. This force, called active tension, moves bones at joints and resists active stretching due to external forces like gravity. Check out the YouTube video Muscle Contraction Process: Molecular Mechanism [3D Animation].

The Role of Connective Tissue

Connective tissue packages muscle fibers together and connects muscle fibers to bone (as well as skin, muscle, and deep fascia). Fascia, fibrous connective tissue, divides muscles into functional groups, aids muscle movement, transmits force to bones, encloses and supports blood vessels and nerve fibers, and secures organs in their place (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

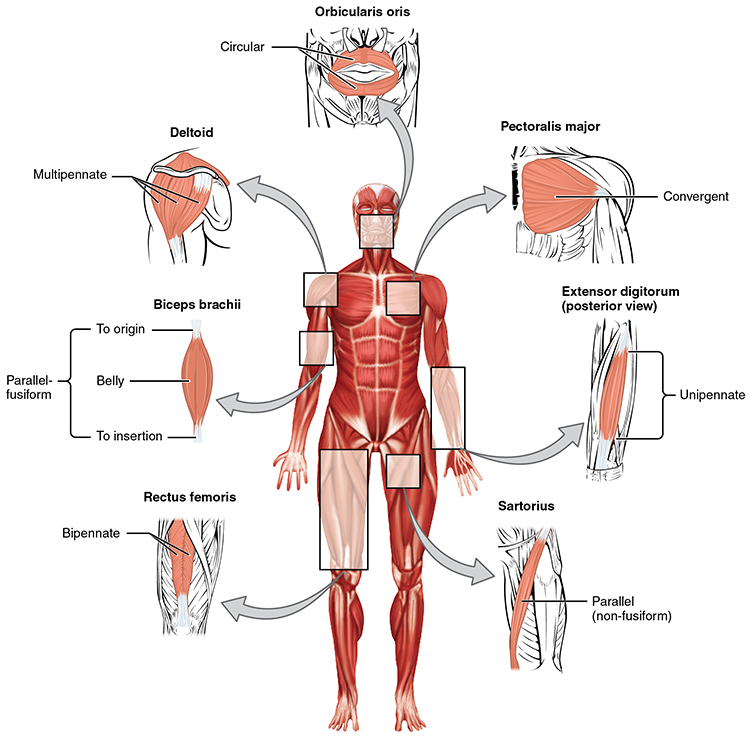

Muscle fiber bundles are called fascicles. The muscle fibers within a fascicle are parallel to each other.

Fascicle-tendon connections can assume five shapes: circular, fusiform (narrow at the ends and wide in the center), parallel, pennate (feather-shaped, including unipennate, bipennate, and multipennate), or triangular (convergent; Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Tendons are dense fasciae that connect muscles to other structures. Connective tissue provides the skeletal muscle system's elasticity. Connective tissue elasticity produces passive tension, allowing muscle fibers to generate, sum, and transmit force (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Comprehension Questions: Muscle Structure

- What is the smallest contractile unit of a muscle fiber, and what structures define its boundaries?

- Explain the difference between thin and thick filaments in terms of their protein composition and location within the sarcomere.

- How does titin contribute to muscle elasticity and the maintenance of sarcomere structure?

- What role does connective tissue play in force transmission from muscle fibers to bones?

Motor Units: The Functional Units of Movement

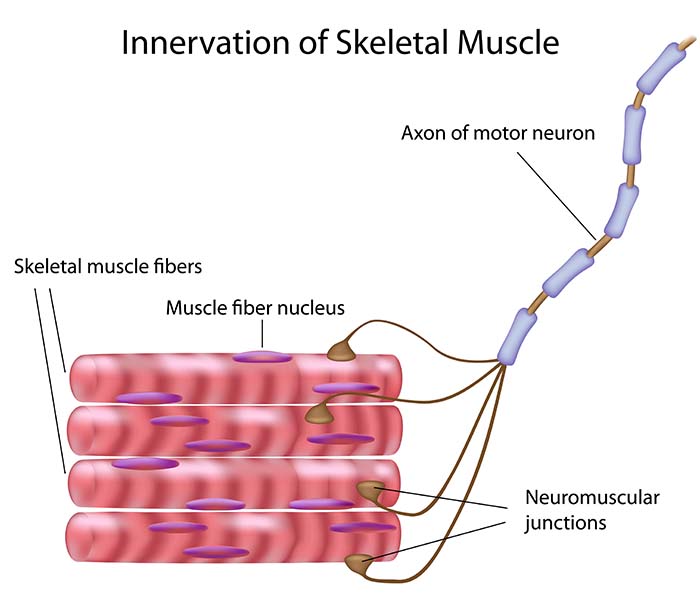

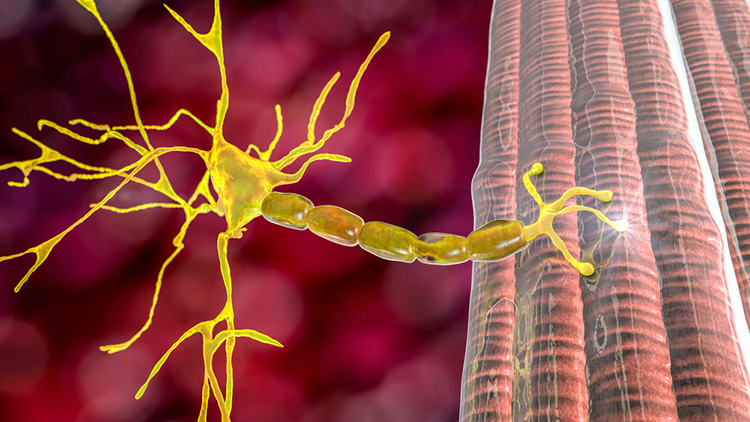

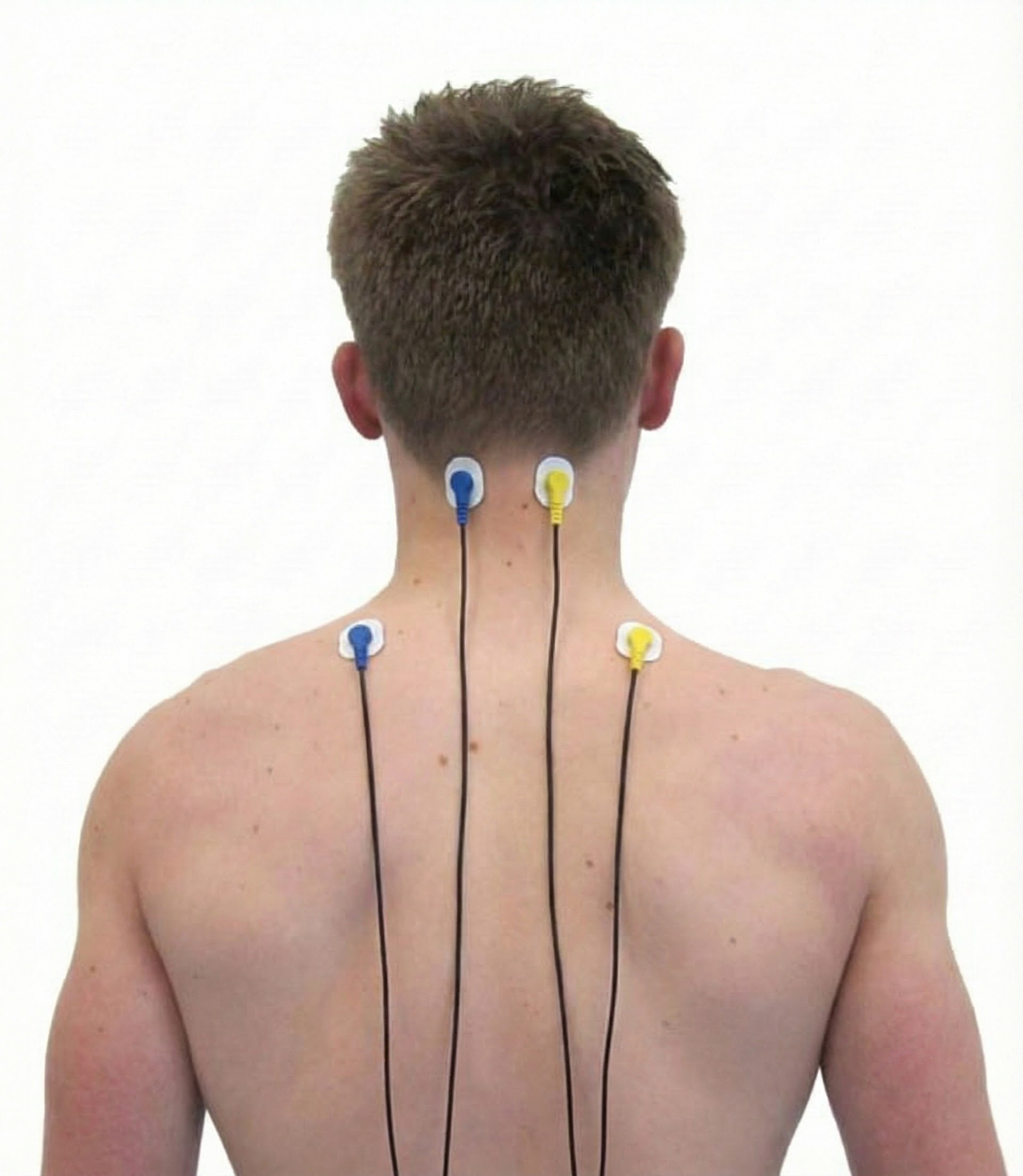

Skeletal muscle fibers are organized into motor units consisting of an alpha motor neuron and the extrafusal muscle fibers it controls. In the diagram below, a motor neuron's axon branches to simultaneously innervate four extrafusal muscle fibers. This motor unit is designed for precise control instead of generating force.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Motor Units

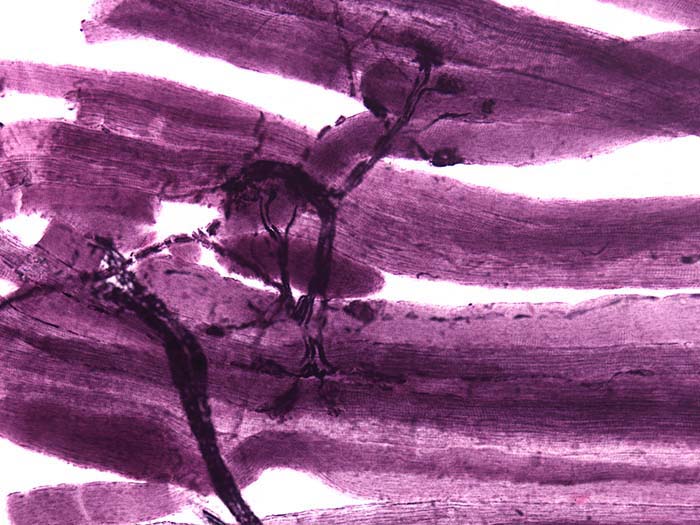

An alpha motor neuron's cell body lies in the ventral horns of the spinal cord. The axon, depicted in the photomicrograph below as a dark filament, may extend three feet until it synapses with muscle fibers. Separate motor neurons may innervate muscles that perform several actions.

Alpha motor neurons, which conduct messages from the central nervous system to skeletal muscles, are called efferent nerves because they leave the central nervous system.

A motor unit contains from 3 to 3000 muscle fibers that contract completely or not at all. The average motor unit contains 150 fibers (Buchthal & Schmalbruch, 1980; Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). All motor unit muscle fibers share the same composition.

Motor Unit Size Determines Precision vs. Power

Smaller motor units perform precise movements. For example, the larynx, which controls speech, contains motor units with 1-2 muscle fibers. The extraocular muscles that move the eyes contain motor units with 10-20 muscle fibers. Think about how precisely you can direct your gaze or modulate the pitch of your voice. Larger motor units are designed to deliver power instead of precise control. The gastrocnemius muscle located in the calf contains motor units with 2000-3000 muscle fibers (Marieb & Hoehn, 2019). When your client has difficulty with fine motor control, understanding this principle helps explain why some movements are inherently more challenging to train than others.

SEMG biofeedback uses an electromyograph to monitor the total electrical output in microvolts (millionths of a volt) from all the motor units firing near surface electrodes. Contraction strength and SEMG signal voltage are proportional to the number of recruited motor units.

The muscles comprising each motor unit are protected against exhaustion by a refractory period of about 1 millisecond, during which they lose their excitability. Cardiac muscle has a 250-millisecond refractory period (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). Motor units control adjoining bundles of fibers to produce coordinated muscle contraction.

A skeletal muscle contains motor units that differ in the number and size of fibers. Motor unit firing is rotated to prevent fatigue and produce smooth movement. Motor units are recruited in order of size. Smaller units, which are highly excitable, are recruited first since they gradually build up tension. These units provide the precise motor control required in tasks like writing. Larger motor units are normally recruited last as additional force is needed to perform a bench press. In life-threatening emergencies, many motor units may be recruited at once as part of the fight-or-flight response (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

While the muscle fibers comprising an individual motor unit show an all-or-none response, a skeletal muscle can produce graded responses by activating different sets of motor units (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

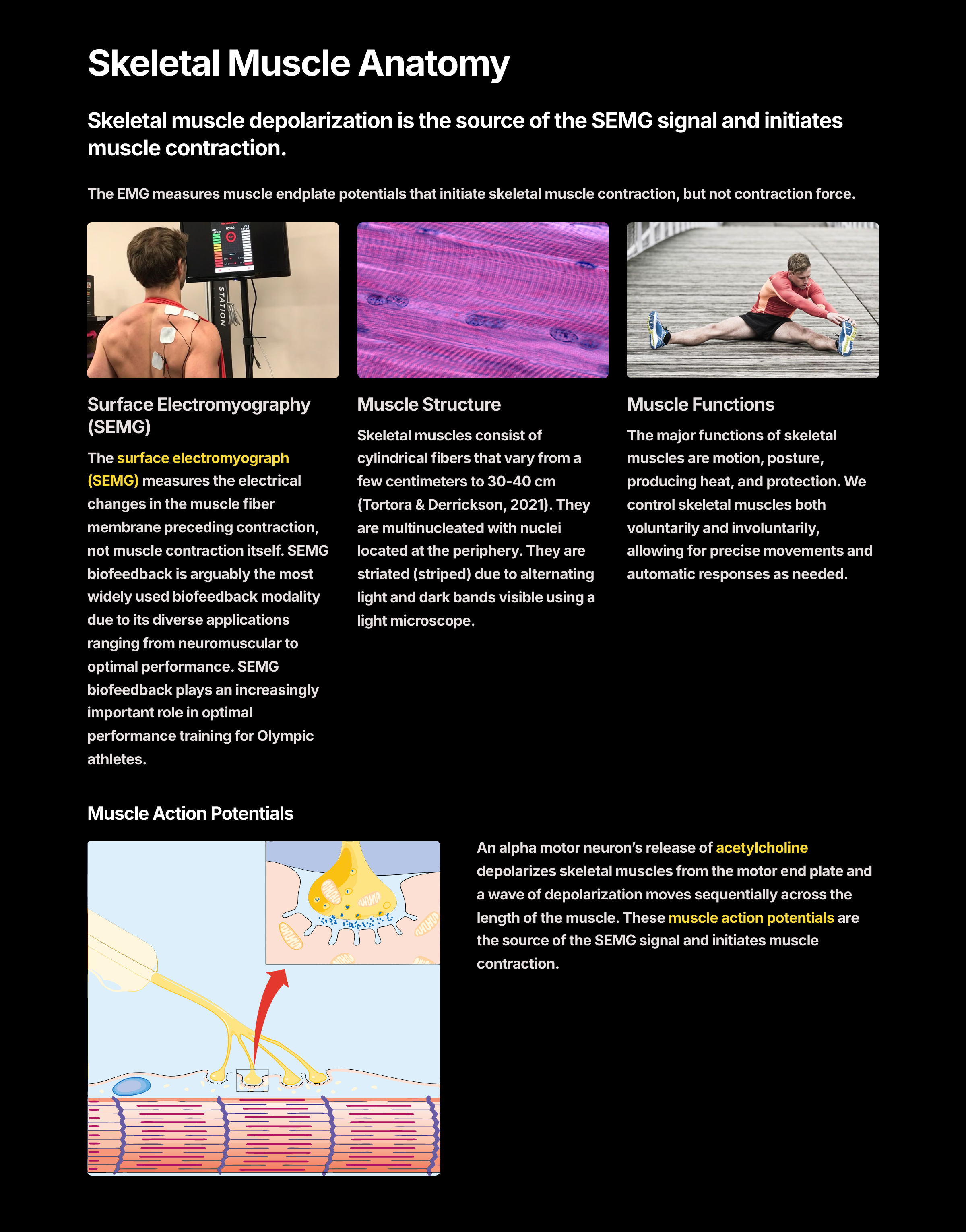

Muscle Action Potentials: The Electrical Trigger

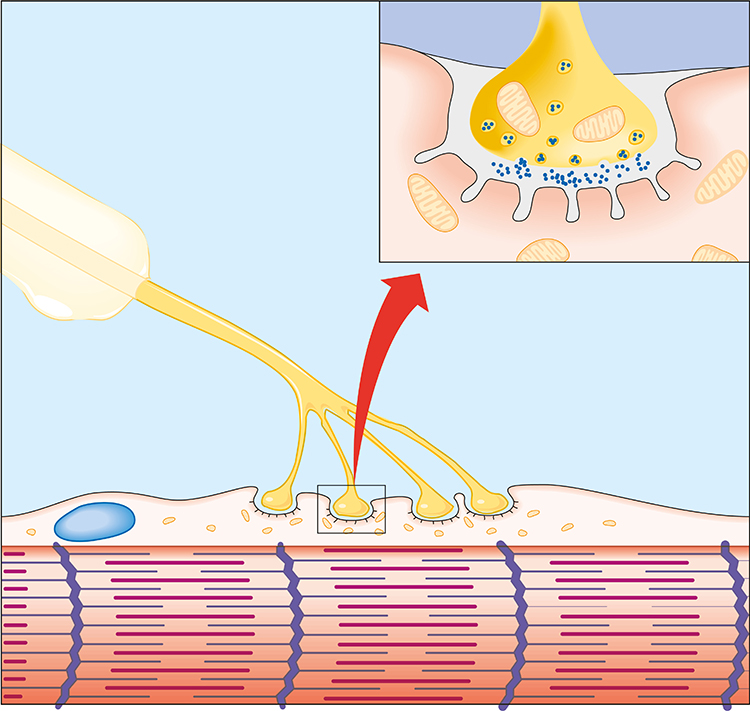

An alpha motor neuron divides into terminal branches that penetrate the muscle fiber membrane. The muscle fiber beneath a terminal branch is called a motor endplate. The terminal branch and motor end plate comprise the neuromuscular junction (NMJ).

When an action potential reaches the terminal branches, calcium ions move inside them. Vesicles containing ACh expel their contents into the NMJ. Each motor endplate contains 30-40 million acetylcholine (ACh) receptors. ACh release depolarizes the motor end plate, producing an end plate potential (EPP).

Listen to a mini-lecture on the Neuromuscular Junction

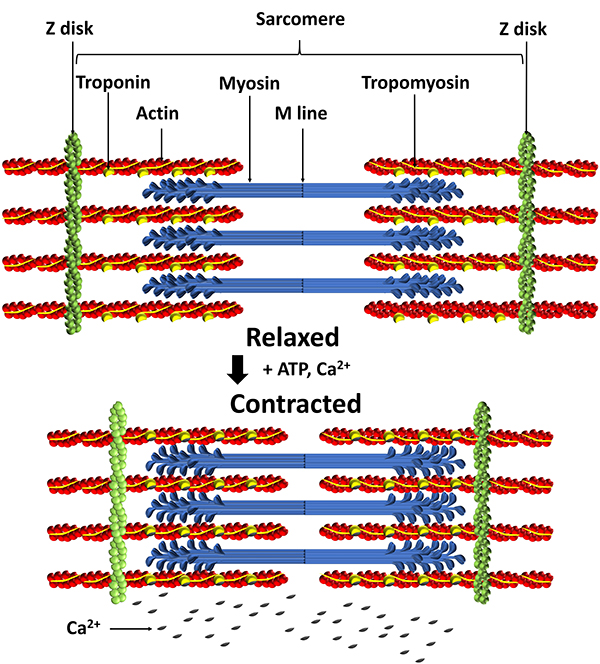

The EPP triggers a depolarizing impulse called a muscle action potential (MAP) that travels sequentially along the sarcolemma into the network of T tubules, causing the terminal cisterns of the sarcoplasmic reticulum to release calcium ions into the sarcoplasm to initiate muscle contraction (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

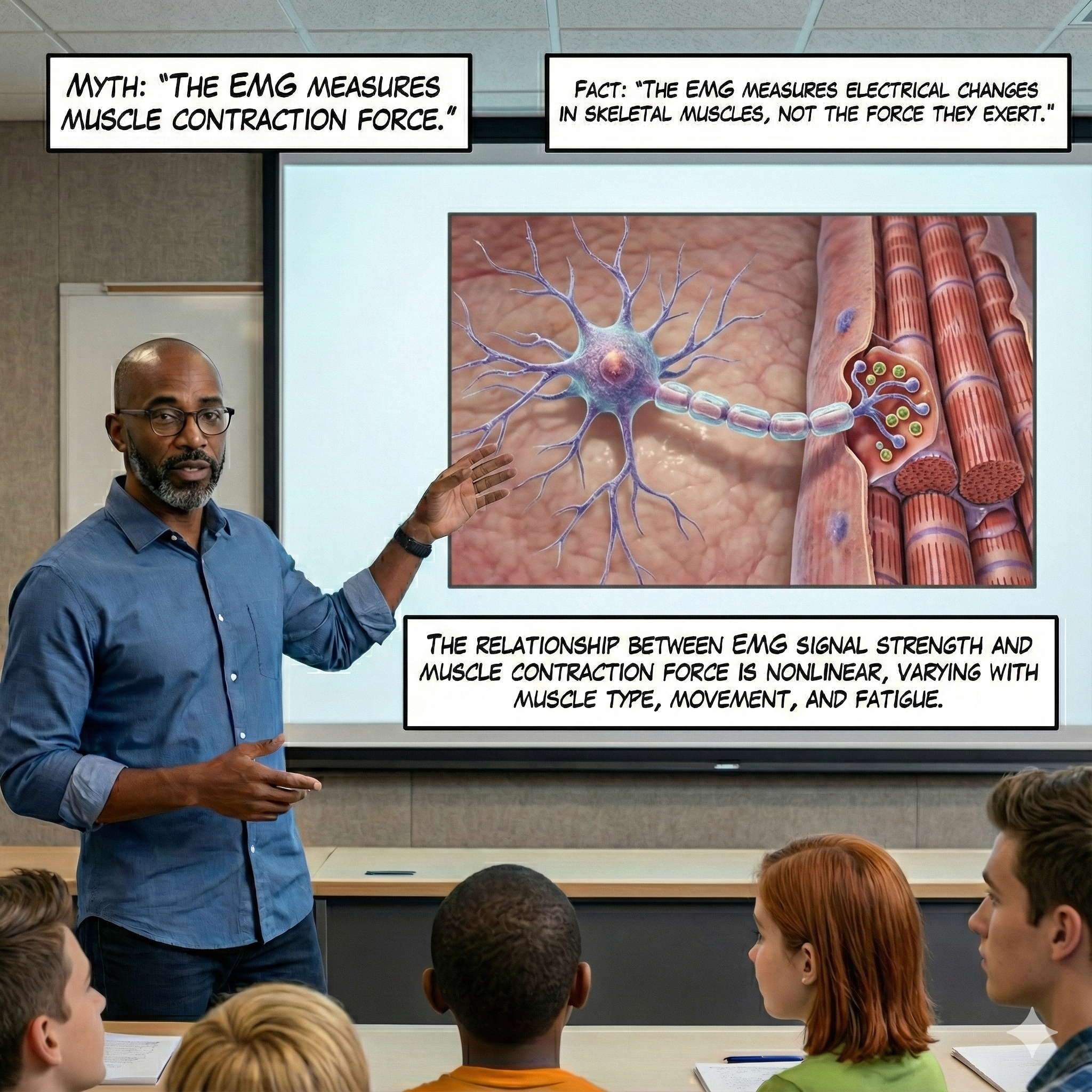

The SEMG Measures Depolarization, Not Contraction

Skeletal muscle depolarization is the source of the SEMG signal and initiates muscle contraction. The EMG measures muscle endplate potentials that initiate skeletal muscle contraction, but not contraction force. This is a crucial distinction for biofeedback practitioners to understand.

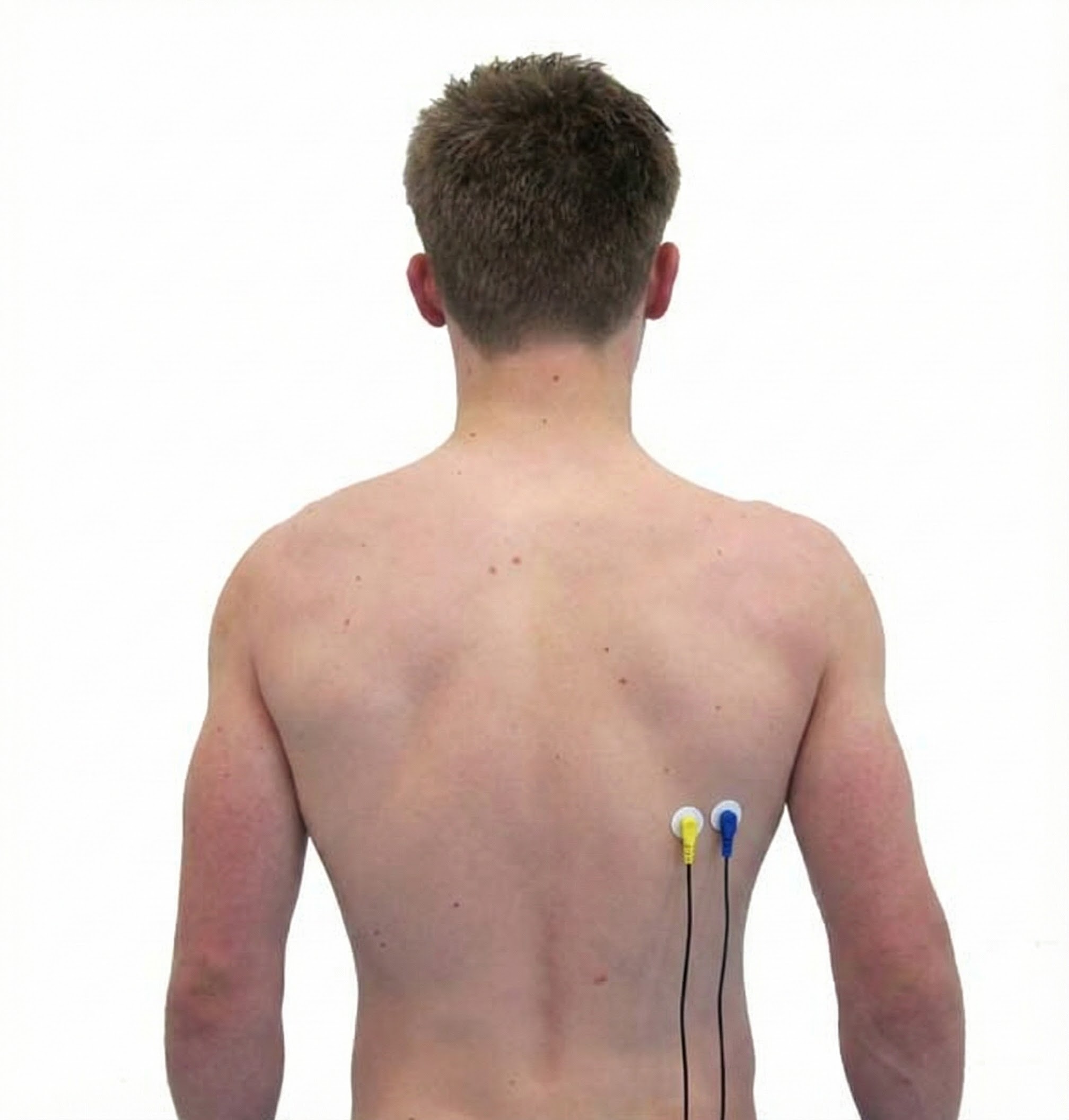

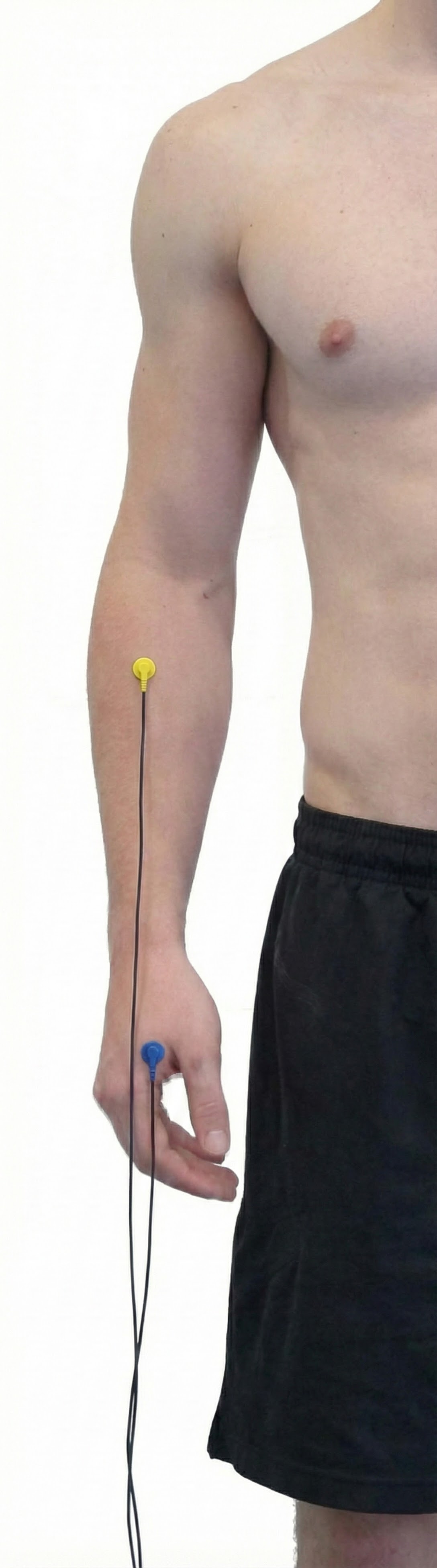

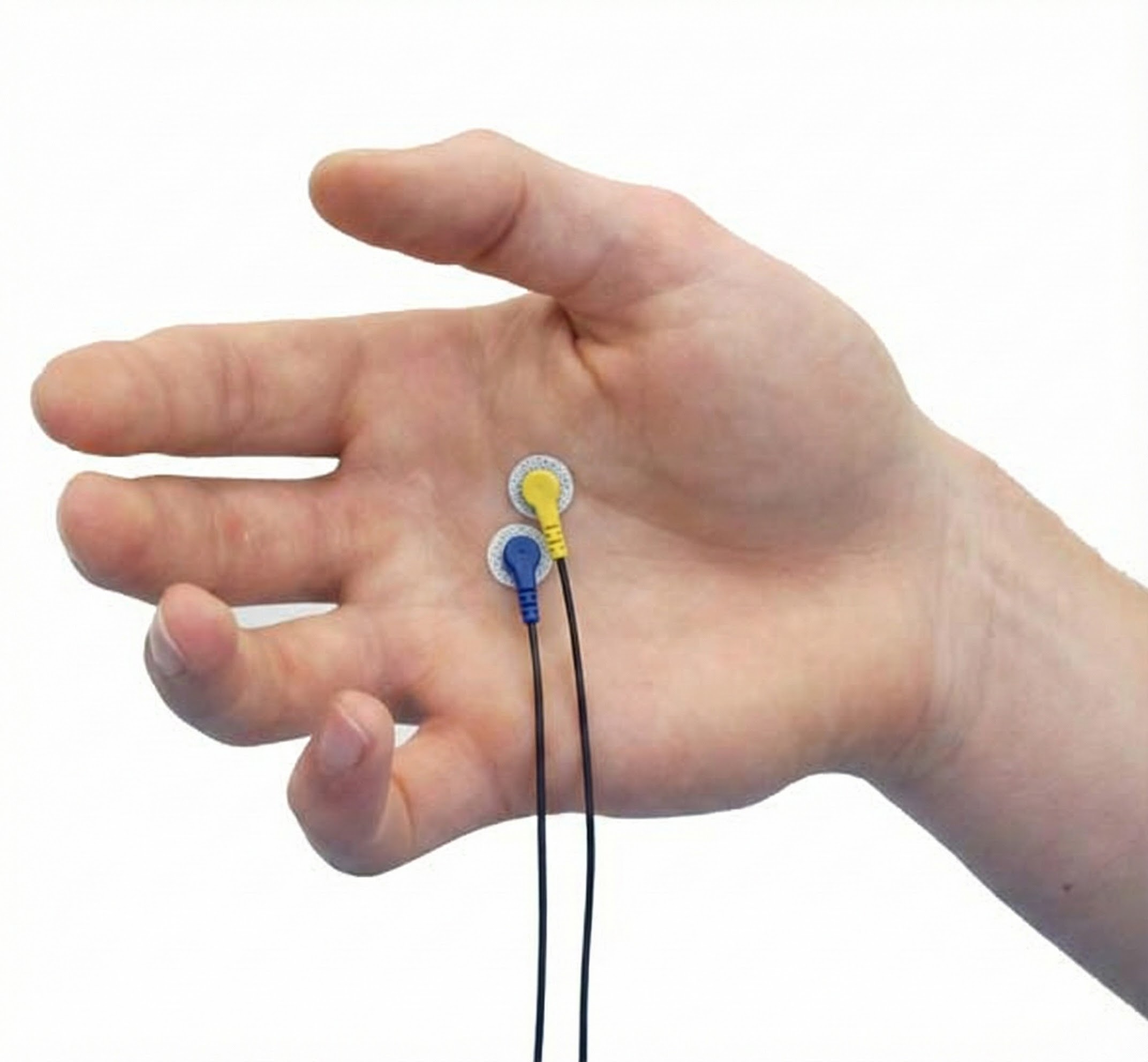

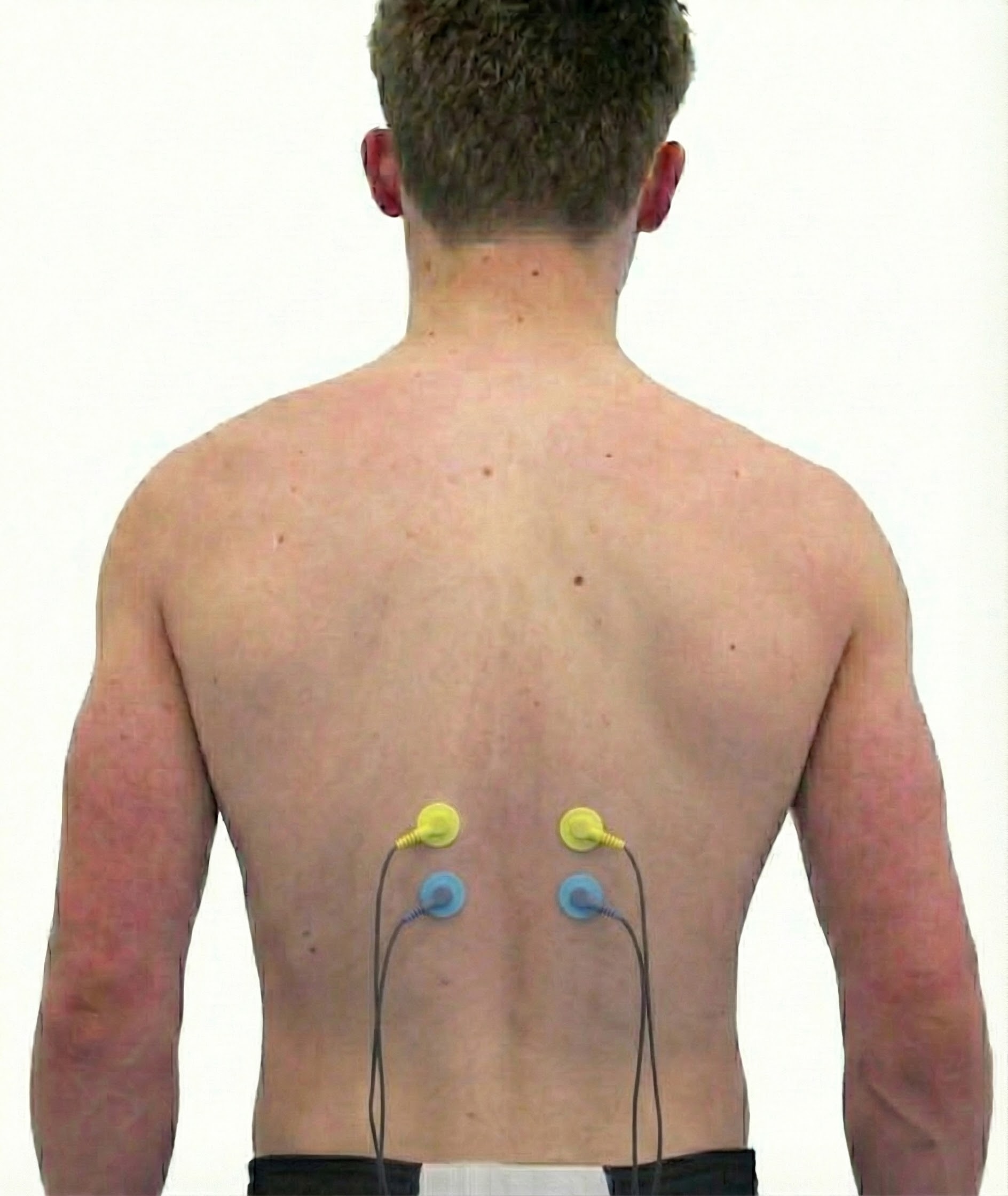

The only way to accurately record a muscle's unique activity is to place electrodes along its striations. Recording across a muscle's striations produces invalid measurements since it averages the activity of several muscles (Sherman, 2010).

When two ACh molecules bind to a nicotinic ACh receptor on the motor end plate, a sodium channel opens, allowing sodium ions to enter the muscle fiber and then potassium ions to leave the fiber's interior. The inflow of positive sodium ions shifts the end plate's internal voltage from -80 to -90 millivolts to +50 to +75 millivolts producing a muscle action potential (MAP). This skeletal muscle fiber depolarization (positive shift in membrane potential) triggers muscle contraction (Hall & Hall, 2020).

Below is a NeXus-10 BioTrace+ display of the raw and integrated 100-500 Hz SEMG signal generously provided by John S. Anderson.

Below is a BioGraph Infiniti SEMG display.

The enzyme acetylcholine esterase (AChE) deactivates ACh to allow muscle fiber relaxation. The sodium-potassium pump restores the muscle fiber to a resting negative voltage so it can be depolarized again, resulting in a new contraction (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Types of Skeletal Muscle Fibers: Matching Function to Form

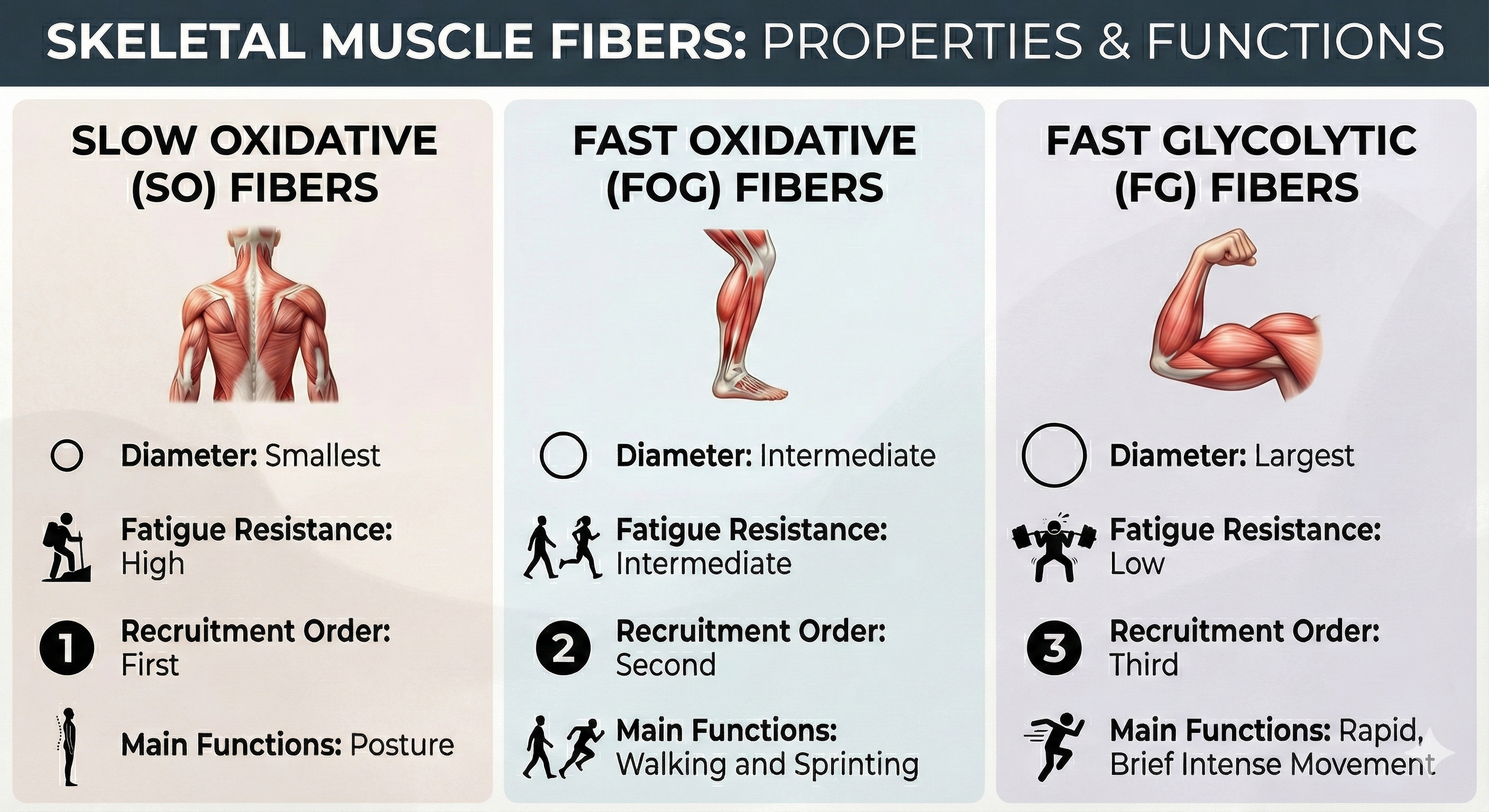

Skeletal muscle fibers vary in structure and function. Three fiber categories have been identified: slow oxidative, fast oxidative, and fast glycolytic. Skeletal muscles are composed of different proportions of these fibers depending on muscle action. However, the motor units that make up a muscle contain the same kind of fiber.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Types of Muscle Fibers

Slow oxidative (SO) fibers are small red fibers rich in myoglobin, mitochondria, and capillaries. Their capacity to produce ATP through oxidative metabolism is high. Since SO fibers split ATP at a slow rate, they contract slowly, work for extended periods, and strongly resist fatigue. Postural muscles contain a high proportion of SO fibers that enables continuous isometric contraction to resist gravity. SO fibers contribute frequencies from 20-90 Hz (Bolek et al., 2016).

Fast oxidative-glycolytic (FOG) fibers are medium-size red fibers rich in myoglobin, mitochondria, and capillaries. They generate energy aerobically and anaerobically. Since FOG fibers rapidly split ATP, they contract quickly. These fibers show less resistance to fatigue than SO fibers and work no longer than 30 minutes. These fibers comprise a large percentage of a sprinter's leg muscles. FOG fibers contribute frequencies from 90-500 Hz (Bolek et al., 2016).

Fast glycolytic (FG) fibers are large white fibers that are poor in myoglobin, mitochondria, and capillaries but contain extensive glycogen stores. FG fibers produce ATP using anaerobic metabolism. FG fibers rapidly split ATP and can contract more quickly than FOG fibers. Since they generate energy anaerobically, these fibers quickly fatigue and only work for a few minutes. Arm muscles contain a high proportion of these fibers (Fox & Rompolski, 2022). FG fibers contribute frequencies from 90-500 Hz (Bolek et al., 2016).

SO fibers contain fewer skeletal muscles in their motor units than FOG and FG fibers, are used more frequently in daily activities, and are recruited earlier (Fox & Rompolski, 2022).

Exercise can change the properties but not the number of muscle fibers. Endurance exercises like running can slowly transform FG fibers into FOG fibers, increasing diameter, mitochondria, capillaries, and strength. In contrast, activities like weight lifting that require explosive force for brief periods increase FG fiber size and strength. Muscle enlargement (hypertrophy) produces a weight lifter's bulging muscles (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Why Chronic Pain Patients May Fatigue More Quickly

Muscle biopsies of chronic pain patients raise the possibility that their postural muscles contain a disproportionate number of FG fibers that fatigue more rapidly than SO fibers. Increased vulnerability to fatigue could result in a buildup of metabolic byproducts (like lactate and hydrogen ions) that can stimulate pain receptors (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). Consider a client named Robert who complains that his upper back pain worsens throughout the workday. Understanding fiber type distribution helps explain why his postural muscles might fatigue by afternoon, contributing to his pain cycle.

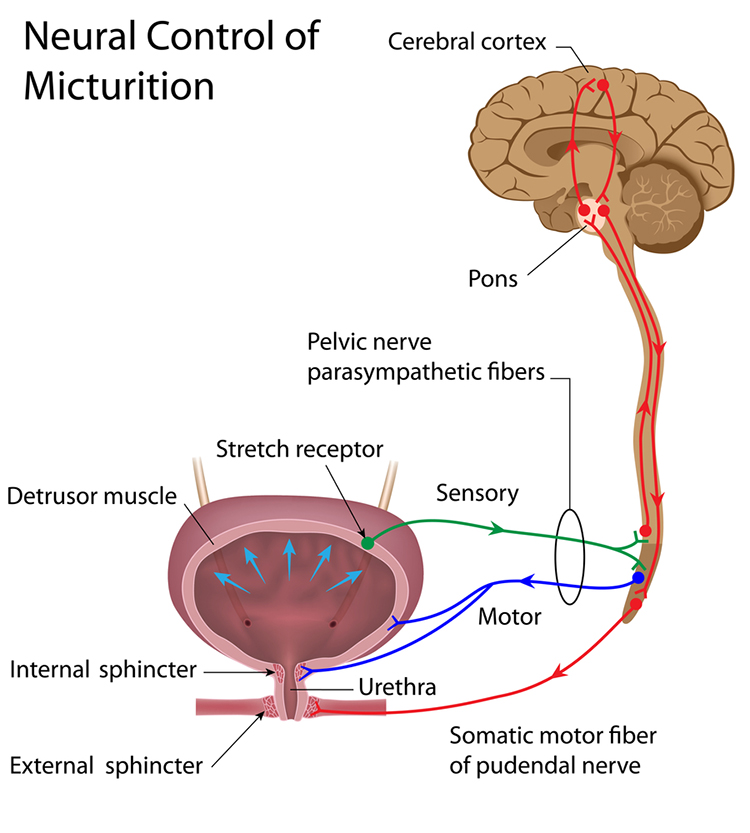

Pelvic Floor Training: Quick Flicks and Endurance

When treating urinary incontinence with EMG biofeedback for the pelvic floor, clinicians must train pelvic floor muscle endurance (Laycock & Haslam, 2008) and quick flicks. These tonic and phasic contractions prevent leakage during events that increase intra-abdominal pressure, such as coughing, lifting, and sneezing (Lee & Kaufman 2017). A comprehensive treatment protocol addresses both fiber types.

The EMG Signal: What Are We Actually Measuring?

The SEMG records muscle action potentials from skeletal motor units.

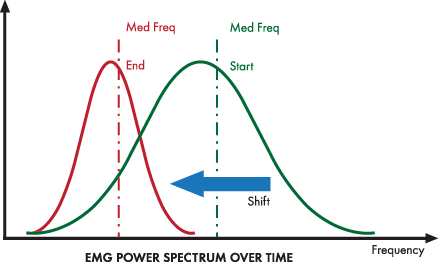

Listen to a mini-lecture on the SEMGThe frequency range for surface recording is 2-1,000 Hz.

Tissues (skin, subcutaneous fat, muscle, and connective tissue) absorb the higher frequencies that can be detected within the muscle fibers by inserted electrodes (Stern, Ray, & Quigley, 2001).

Below is a BioGraph Infiniti SEMG FFT display of a frontales placement. Lower frequency amplitude increases with stronger muscle contraction and the energy distribution shifts toward the higher frequencies.

The amplitude or strength of an electromyogram reflects the number of active motor units, their firing rate, and distance from the electrodes.

A bandpass of 20-200 Hz covers the most critical SEMG frequencies (Andreassi, 2007). Slow-twitch fibers generate frequencies from 10-90 Hz, and fast-twitch fibers generate frequencies from 90-500 Hz.

The greatest concentration of power in a resting muscle lies between 10 and 150 Hz (Stern et al., 2001).

Strong muscle contraction shifts the distribution of SEMG power upwards and to the right toward higher frequencies.

Fatigue decreases motor unit firing rate and shifts the distribution of SEMG power to lower frequencies, lowering the median frequency.

A wide bandpass is desirable because it better monitors a muscle's dynamic range. Failure to use the correct bandpass may make a muscle appear more relaxed than it is or miss fatigue entirely (Sherman, 2010).

Muscle Action Potentials Are Briefer Than The Muscle Contraction Period

Skeletal muscle fiber depolarization (which produces the SEMG signal) lasts 1 to 2 ms and ends before a muscle fiber starts to contract. The SEMG reflects muscle depolarization, not muscle contraction. The period of mechanical contraction is considerably longer and lasts from 10-100 ms.

Calcium binds to troponin, myosin-actin cross-bridges form, and peak muscle fiber tension develops. The relaxation phase also lasts 10-100 ms. Calcium is actively transported back to the sarcoplasmic reticulum, myosin heads detach from actin, and tension declines (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

A muscle action potential depolarizes the interior of the muscle fiber. This membrane potential change releases stored calcium ions from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The presence of calcium ions allows actin (thin) and myosin (thick) filaments to bind to each other forming cross-bridges. Simple contact will not shorten a muscle. Myosin must bind to actin, move it inward, break contact, and bind again. These power strokes use stored energy released by splitting ATP.

A single thick filament forms 600 cross-bridges that attach and detach from actin about five times per second. While some myosin heads perform power strokes, others are detached and preparing to form cross-bridges with actin.

Remember that actin is attached to the Z discs that define each sarcomere (muscle compartment). When myosin ratchets actin inward toward a sarcomere's center, the entire sarcomere shortens to up to 50 percent of its resting length. Sarcomere shortening produces the force of muscle contraction that can move or stabilize limbs. A sarcomere's average length is 2.5 micrometers. It can shorten to about 1.5 micrometers and stretch to about 3 micrometers.

Comprehension Questions: Motor Units and the EMG Signal

- Why does the SEMG measure electrical activity rather than actual muscle contraction force?

- How does motor unit size relate to the precision versus power of muscle movements?

- What happens to the frequency distribution of the SEMG signal when a muscle fatigues?

- Why is electrode placement along (rather than across) muscle striations important for valid SEMG recording?

- Explain the relationship between the three types of muscle fibers and their clinical relevance for understanding fatigue in chronic pain patients.

Skeletal Muscle Contraction: Isometric and Isotonic

Muscle contraction may be isometric or isotonic. Muscles produce tension with minimal fiber shortening during isometric contraction. For example, muscles do not appreciably shorten when you perform a plank due to the resistance of gravity. Posture results from continuous isometric contraction. SO fibers are specialized for this contraction due to their fatigue resistance.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Isotonic and Isometric Contractions

Isotonic contraction produces movement by exerting tension on an attached structure (bone). These contractions may be either concentric or eccentric. Performing curls involves concentric contraction, where fibers shorten as you pull the bar towards your torso.

In contrast, a squat involves eccentric contraction where fibers lengthen as you lower yourself (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Muscles groups work together to perform actions like the series of flips shown below.

You contract at least nine muscle groups in a specific sequence to open your mouth. You activate a different sequence to close your mouth. SEMG biofeedback records the electrical activity of surface muscles. The SEMG usually monitors the activity of muscle groups instead of individual muscles.

The Stretch Reflex: Protecting Muscle Length

Muscle spindles are stretch receptors that lie in parallel with skeletal muscle fibers. Muscle spindles allow us to restore muscle length when muscle fibers lengthen. The image below from Dr. J. H. H. Scott of Leicester University is from the first dorsal interosseus muscle of the hand.

When their annulospiral receptors stretch as a muscle lengthens, they activate alpha motor neurons to strengthen muscle contraction to increase muscle tone. Physicians assess the monosynaptic stretch reflex when stretching the patellar tendon with a rubber mallet to elicit a knee jerk (Breedlove & Watson, 2023).

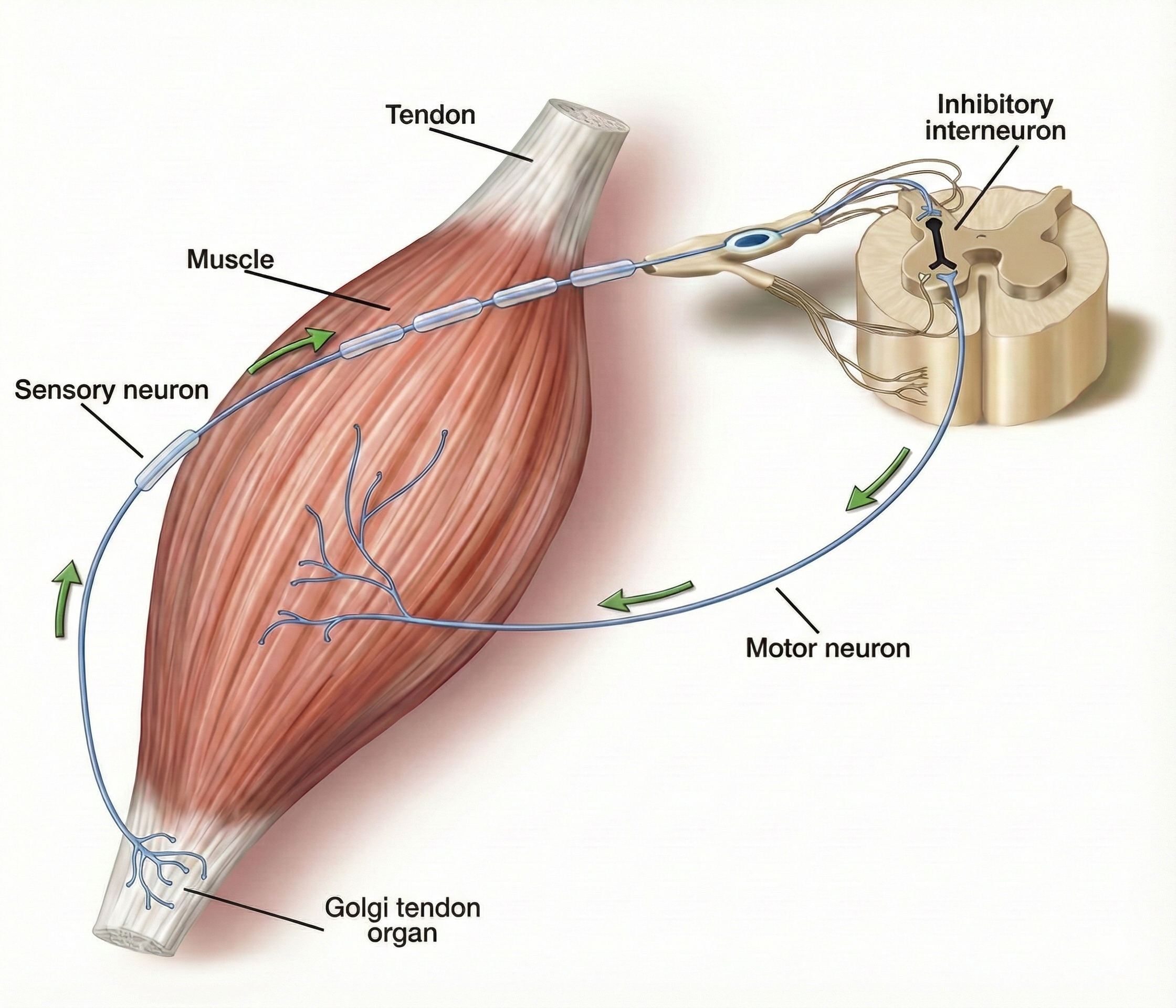

The Tendon Reflex: Protecting Against Excessive Force

Golgi tendon organs are force detectors that lie in series with skeletal muscle fibers. They protect muscles and tendons from injury due to forceful contractions.

When excessive contraction threatens to damage muscle and tendon, they inhibit the responsible alpha motor neurons to prevent injury. This protective mechanism is called the tendon reflex (Breedlove & Watson, 2020).

Muscle Action: How Muscles Move the Skeleton

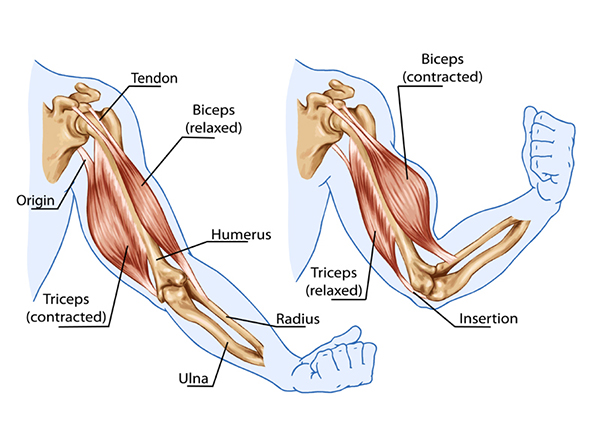

Skeletal muscles attach to the articulating bones of a joint and transmit force through the tendons to bones and tissues like the skin. Muscle contraction moves the two bones that comprise a joint unequally and pulls one of the articulating bones at a joint toward the more stationary bone. A muscle tendon's attachment to the more stationary bone is called its origin, and its other tendon's attachment to the movable bone is called its insertion.

The prime mover (agonist) is directly responsible for producing a specific movement. For example, when the biceps brachii (prime mover) contracts to flex the forearm at the elbow joint, the triceps brachii (antagonist) must relax, or else flexion will be prevented. An antagonist opposes a prime mover's action and yields to its movement. Muscles acting as antagonists also help regulate the action of a prime mover by contracting slightly to apply a braking force. Antagonist contraction helps produce smooth movement and reduce risk of injury from rapid, uncontrolled movement.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Muscle ActionsSynergists aid prime movers by stabilizing intermediate joints to prevent co-contraction (for example, flexing your fingers without flexing the wrist) and unwanted movement. They are usually near the prime mover. For example, the deltoid and pectoralis major anchor both the arm and shoulder when the biceps brachii (agonist) contracts to flex the forearm (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Muscles that act as fixators stabilize a prime mover's origin for more efficient action. By steadying a limb's proximal end, fixators support movements at the distal end. For example, the mobile scapula is the origin of several arm muscles and must be steadied for actions like abduction. Depending on their movement, the same muscles may act as prime movers, antagonists, synergists, or fixators (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Flexors decrease the angle between two bones. Biceps brachii flexes and supinates (turns up) the forearm. Extensors increase the angle between two bones. Triceps brachii extends the forearm.

Abductors move a limb away from the center of the trunk or a body part. The deltoid abducts the arm. Adductors move a limb toward the center of the trunk or a body part. Pectoralis major adducts the arm.

Levators produce upward movement. Levator scapulae elevates the shoulder blades. Depressors produce downward movement. Latissimus dorsi is the primary shoulder girdle and scapular (shoulder blade) depressor.

Supinators turn the palm upward (anteriorly). Supinator exposes the anterior side of the forearm. Pronators turn the palm downward (posteriorly). Pronator teres exposes the posterior side of the forearm.

Dorsiflexors point the toes toward the shin (superiorly) through flexion at the ankle joint. Tibialis anterior dorsiflexes and inverts the foot during the swing phase of walking. Dorsiflexion is disrupted during a neuromuscular disorder called foot drop in which the toes drag on the ground.

Plantar flexors point the toes downward (inferiorly) through extension at the ankle joint. The gastrocnemius/soleus complex, which acts on the Achilles tendon, is the body's primary plantar flexor. The gastrocnemius is considered the most important walking muscle (Jadali, 2021).

Invertors turn the sole of a foot inward. The tibialis posterior and tibialis anterior are the primary invertors. Evertors turn the sole of a foot outward. The fibularis longus and tertius muscles perform eversion.

Tensors make a body part more rigid. Tensor fasciae latae flexes and abducts the thigh. Rotators move a bone around a longitudinal axis. Obturator externus laterally rotates the thigh (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021).

Comprehension Questions: Muscle Contraction and Action

- What is the difference between isometric and isotonic muscle contraction, and give an example of each?

- Explain the relationship between a prime mover (agonist) and its antagonist using the biceps and triceps as examples.

- What is the role of synergists and fixators in coordinated movement?

- How do the stretch reflex and tendon reflex protect the musculoskeletal system from injury?

- A client with foot drop has difficulty with dorsiflexion. Which muscle would you target with SEMG biofeedback, and why?

Muscle Actions, Sensor Placements, and Clinical Applications

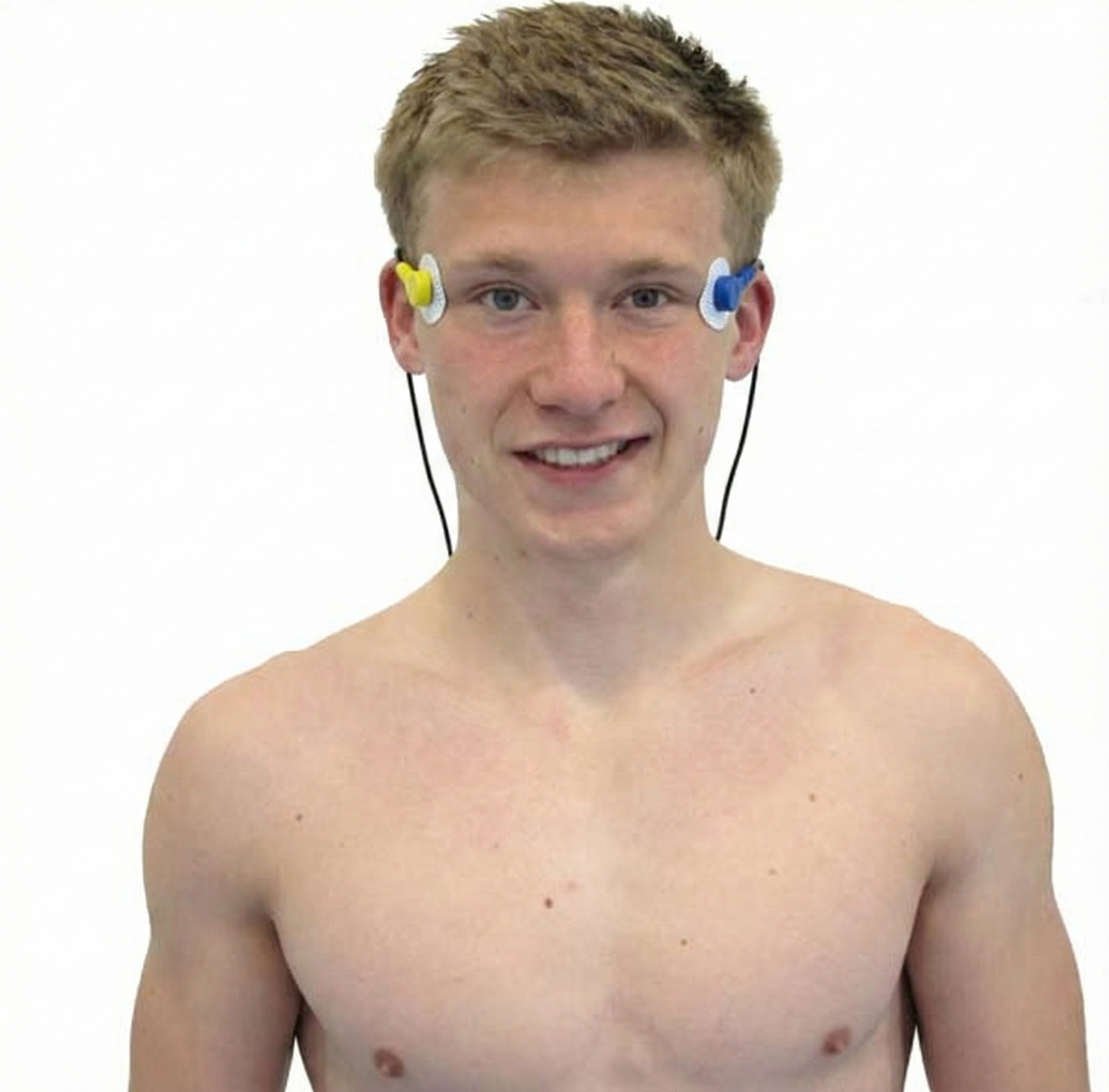

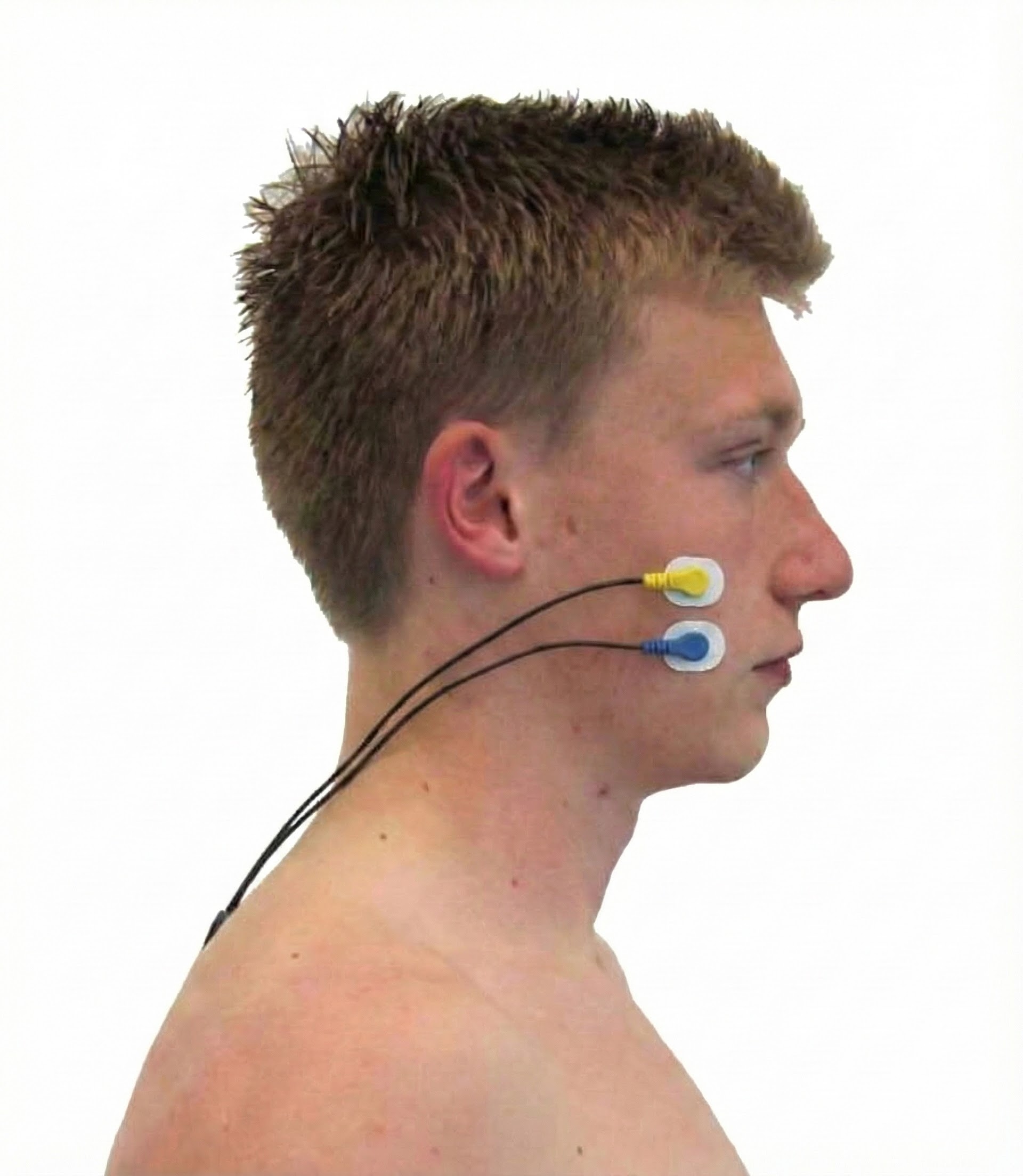

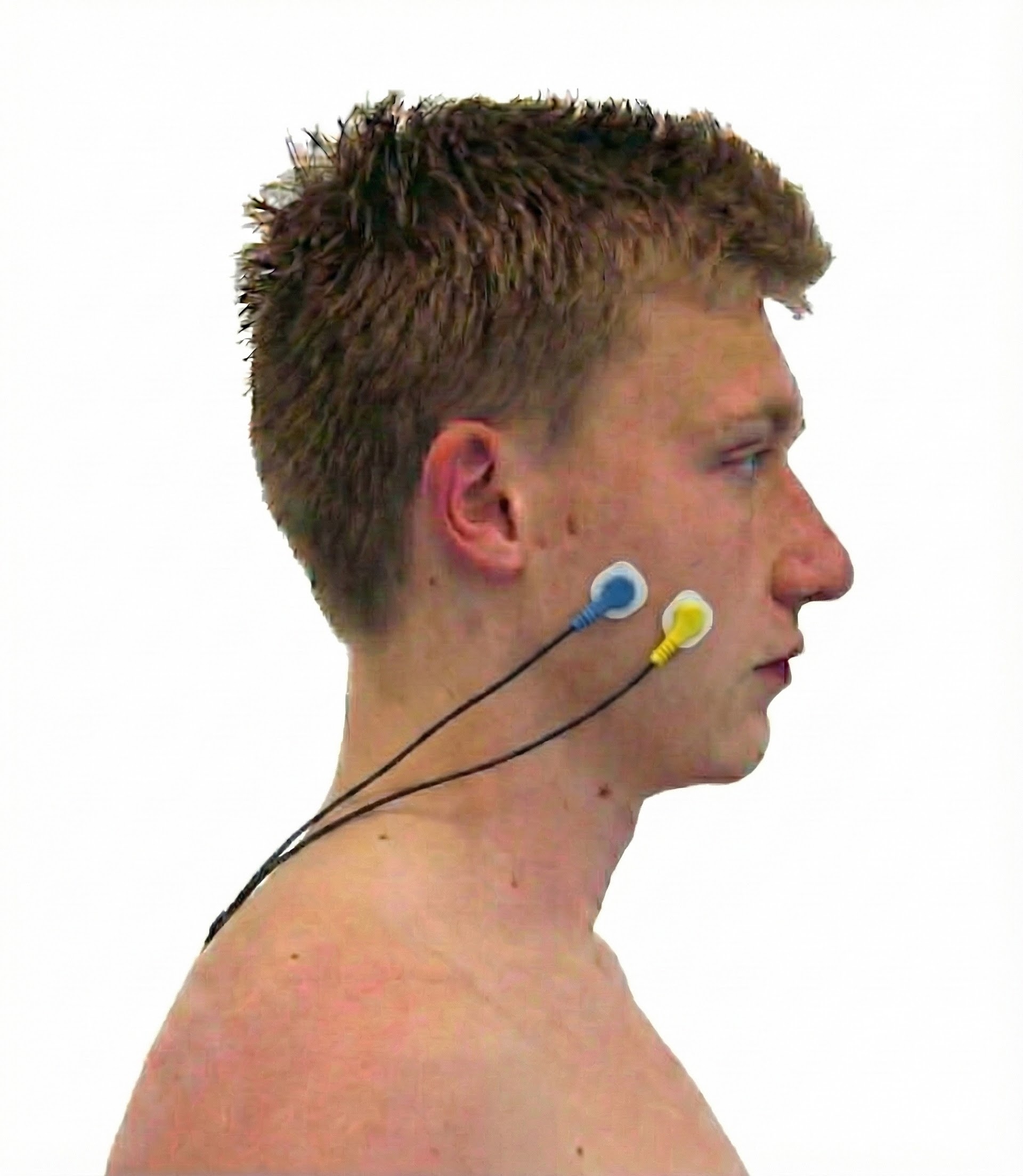

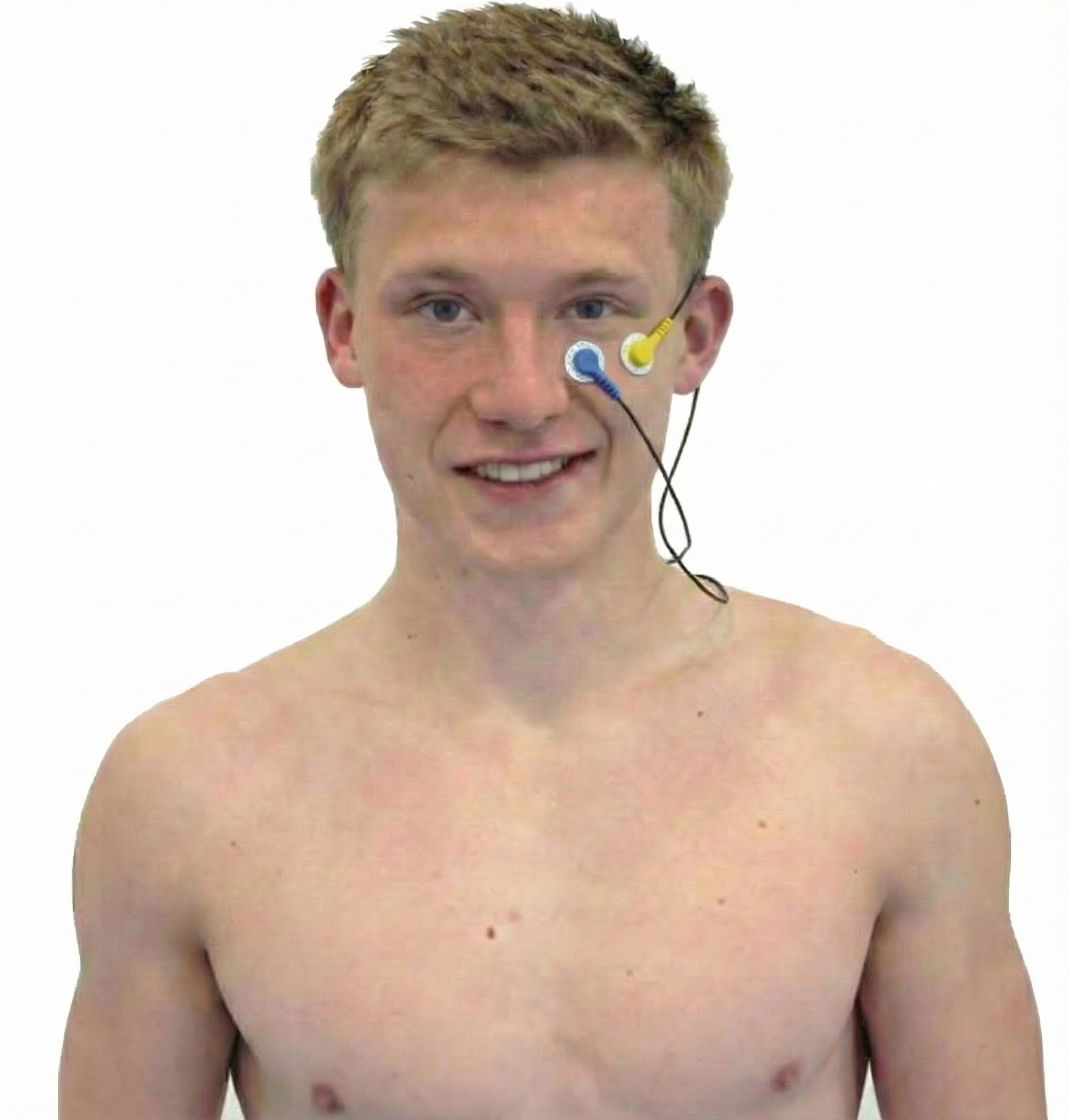

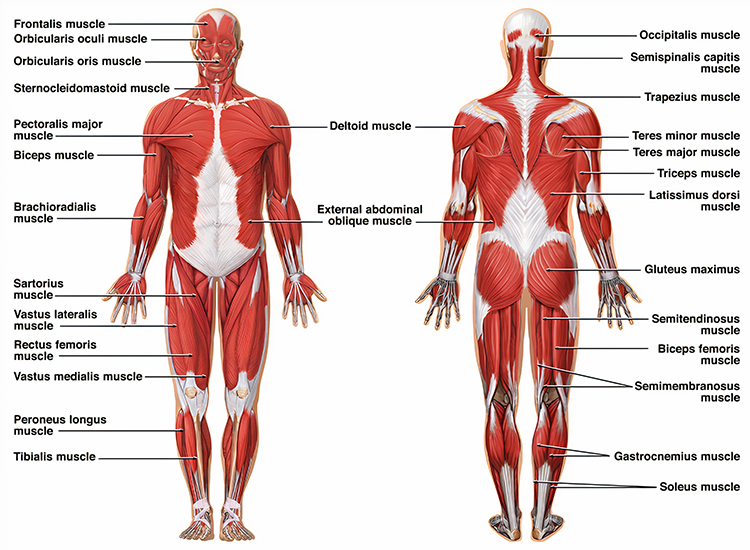

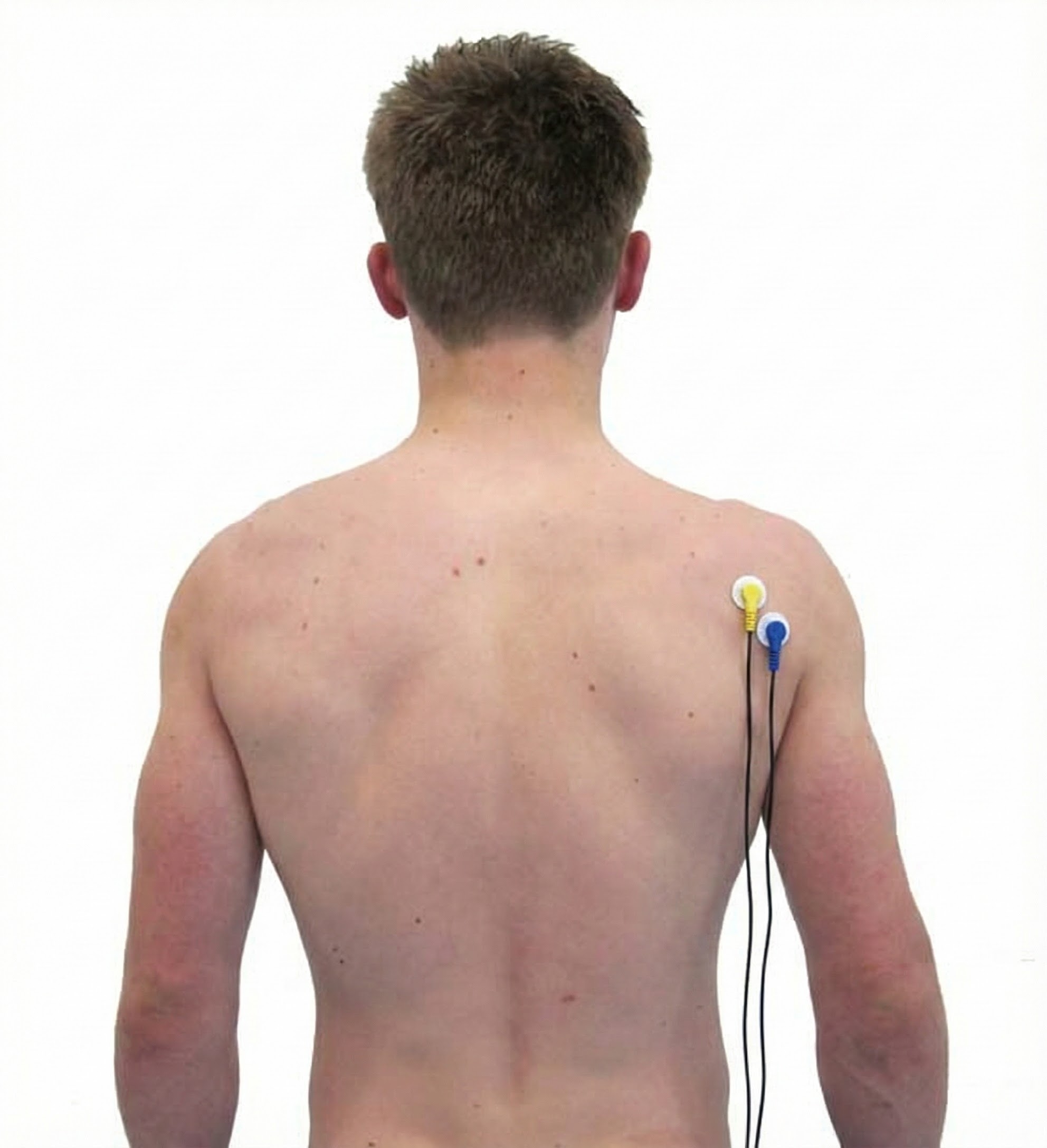

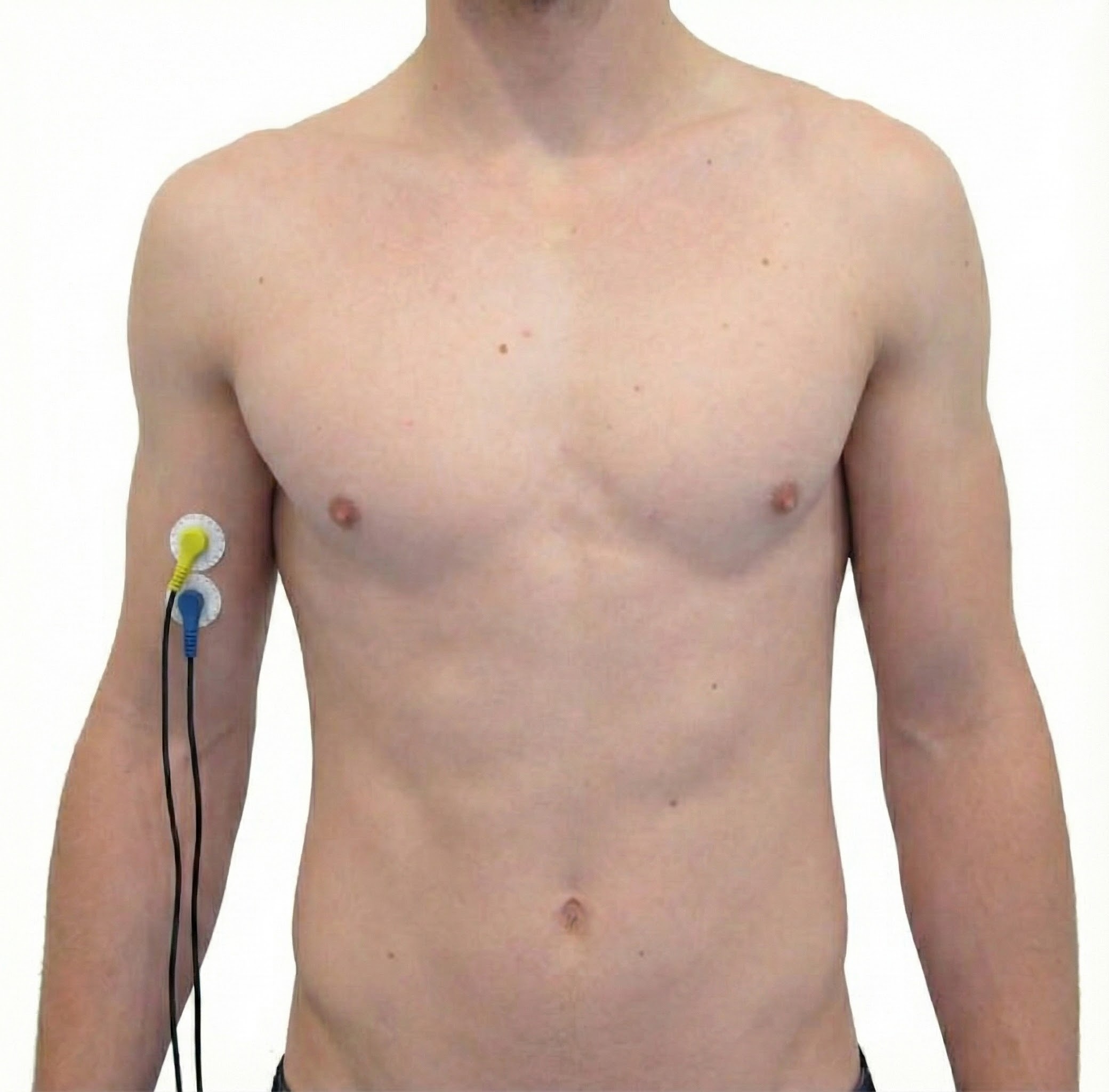

The next two sections provide a detailed description of muscle actions, sensor placements, and clinical applications. Although the BCIA Biofeedback Blueprint does not cover this content at this level of detail, it can be invaluable for applicants during their mentorship and for understanding research reports.

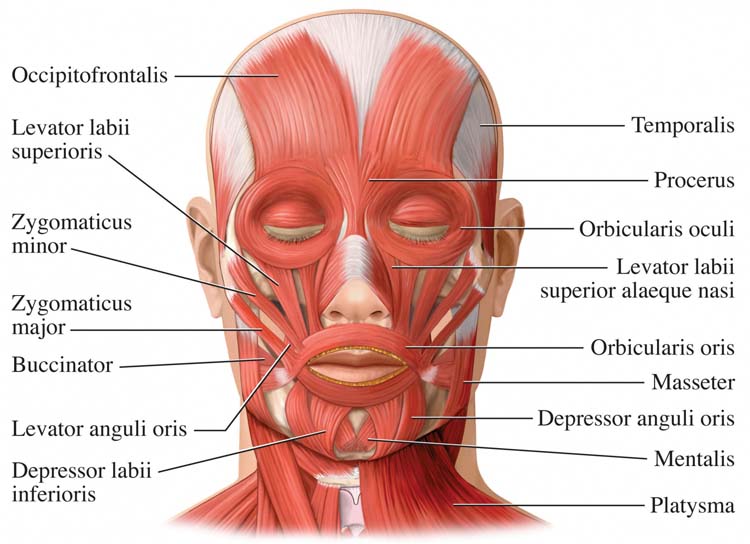

Skeletal Muscles of Clinical Interest: Face and Neck

Basmajian and Blumenstein (1980) and Neblett (2006) were the references for sensor placement. Tortora and Derrickson (2021) was the resource for muscle action.

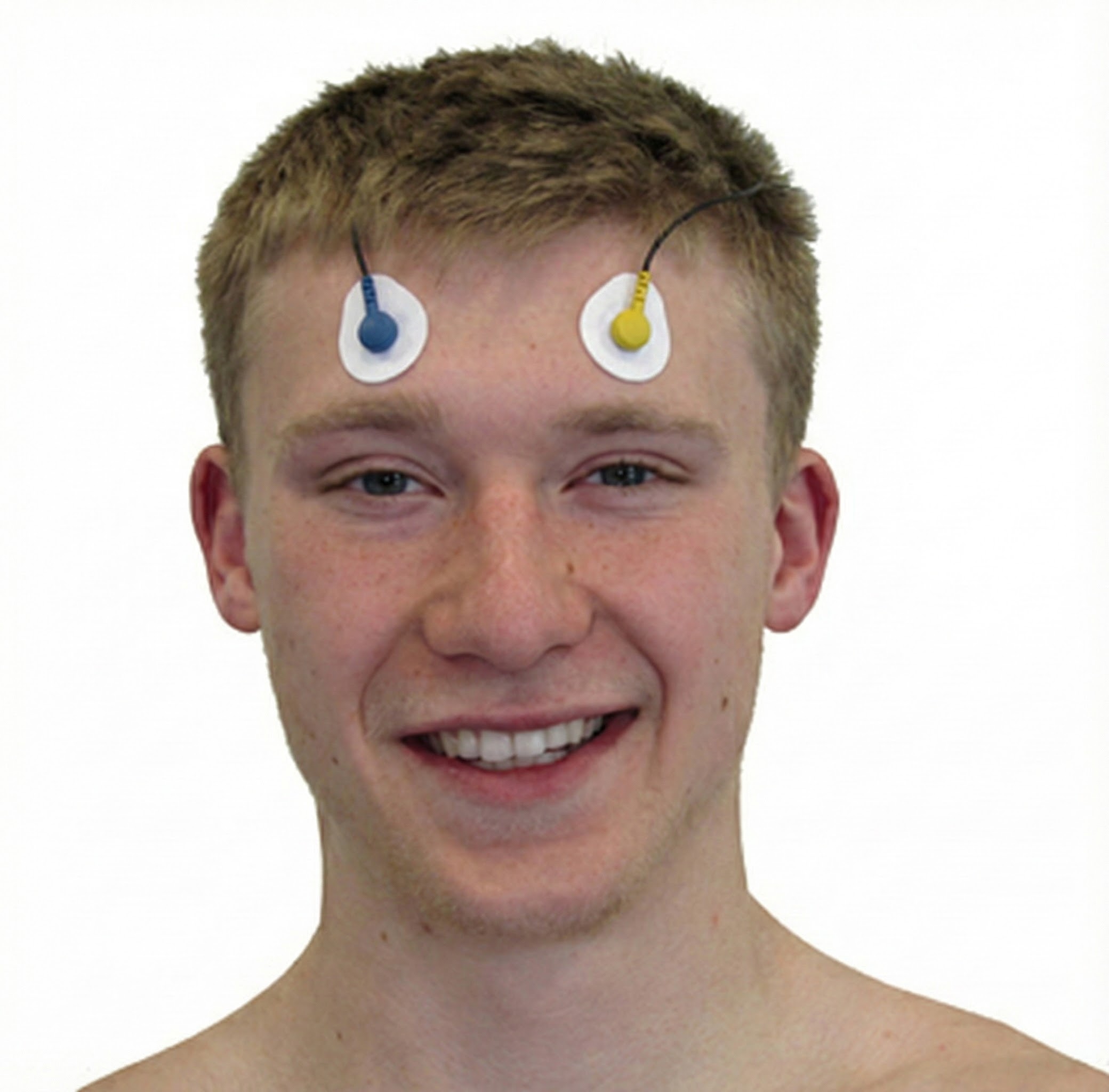

Frontales

Temporalis

Masseter

Zygomaticus

Orbicularis Oculus

Sternocleidomastoid (SCM)

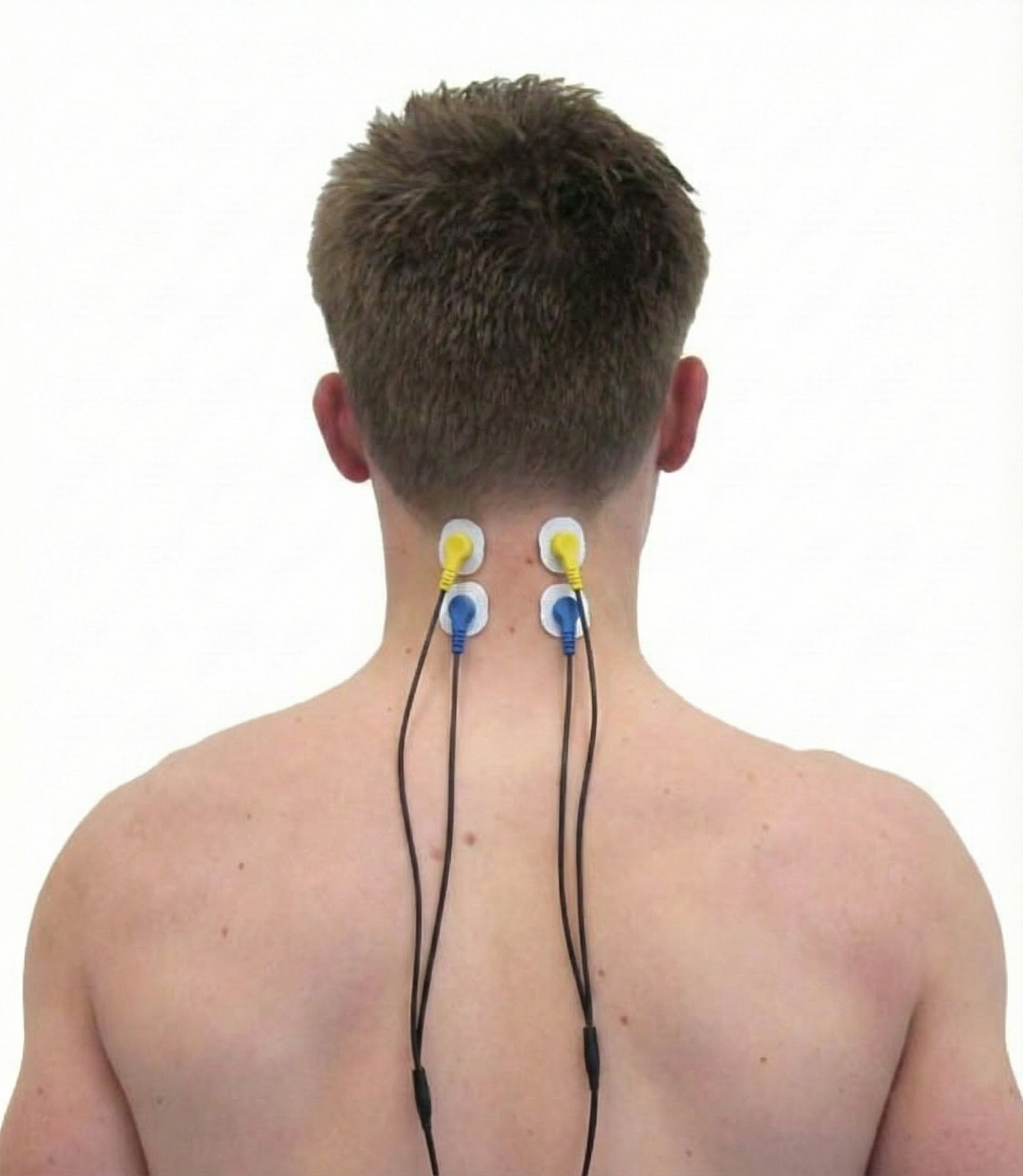

Cervical Paraspinal (Semispinalis Capitis and Splenius Capitis)

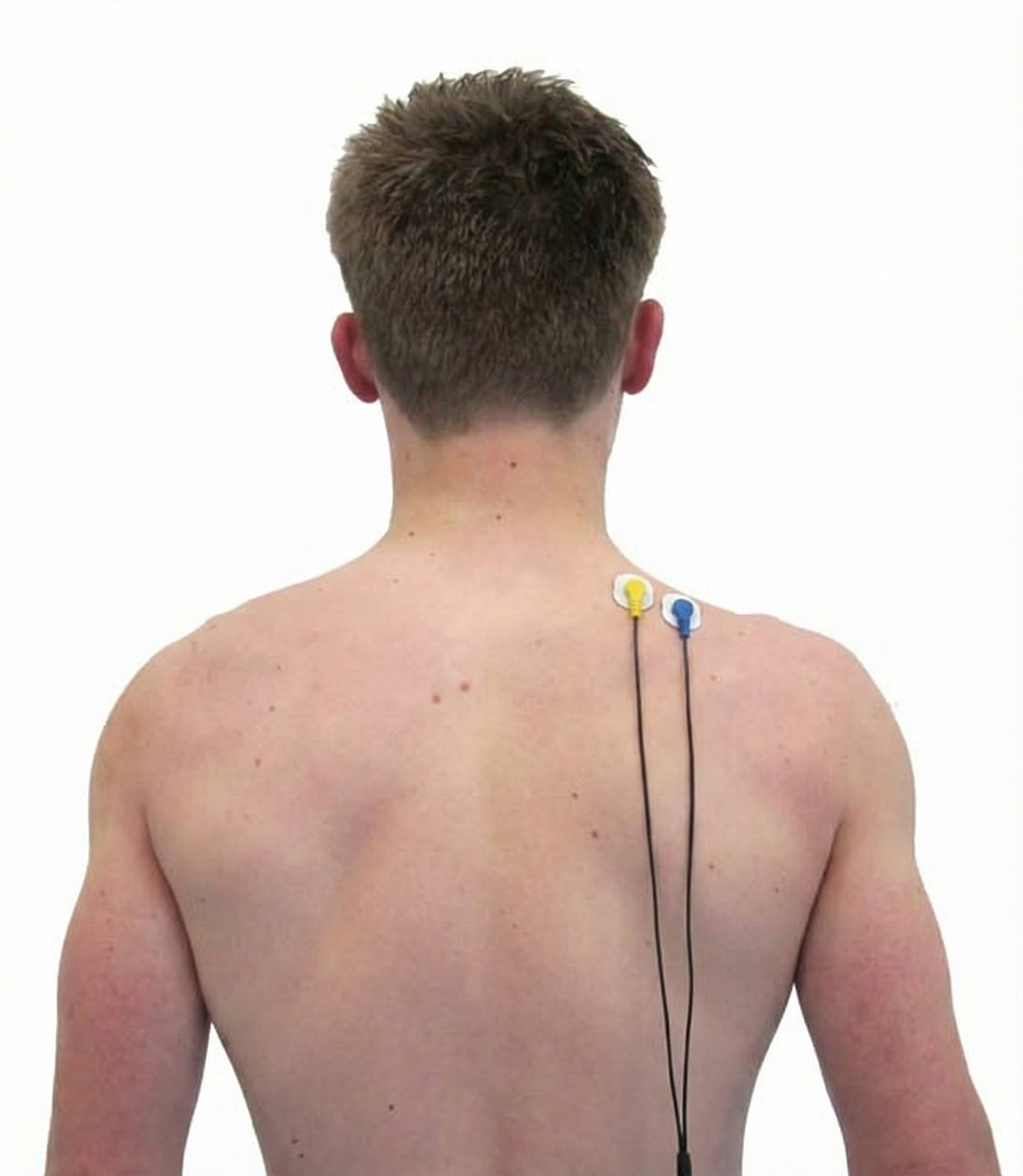

Upper Trapezius

Skeletal Muscles of Clinical Interest: Body

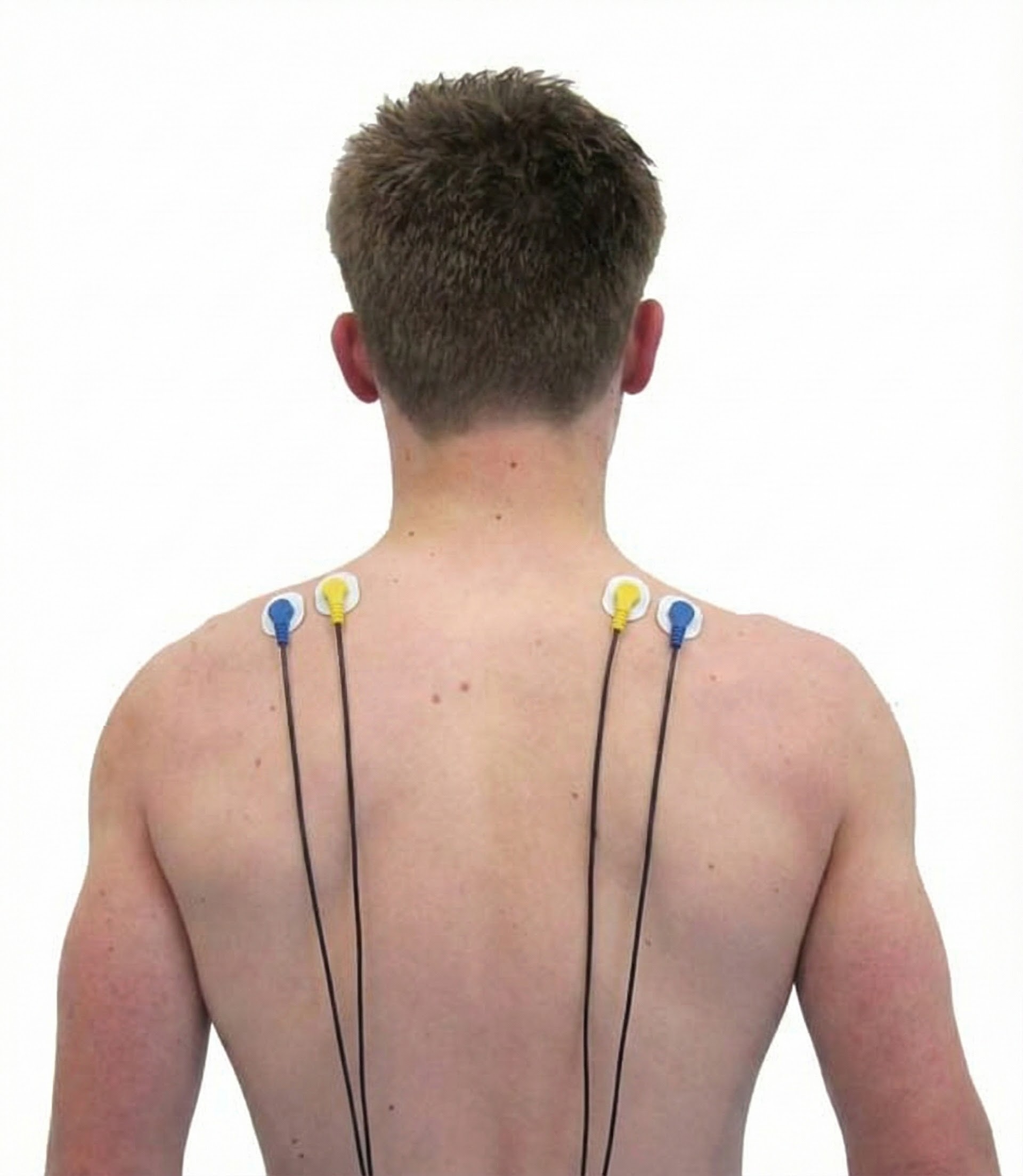

Posterior Deltoid

Lateral Head of Triceps Brachii

Biceps Brachii

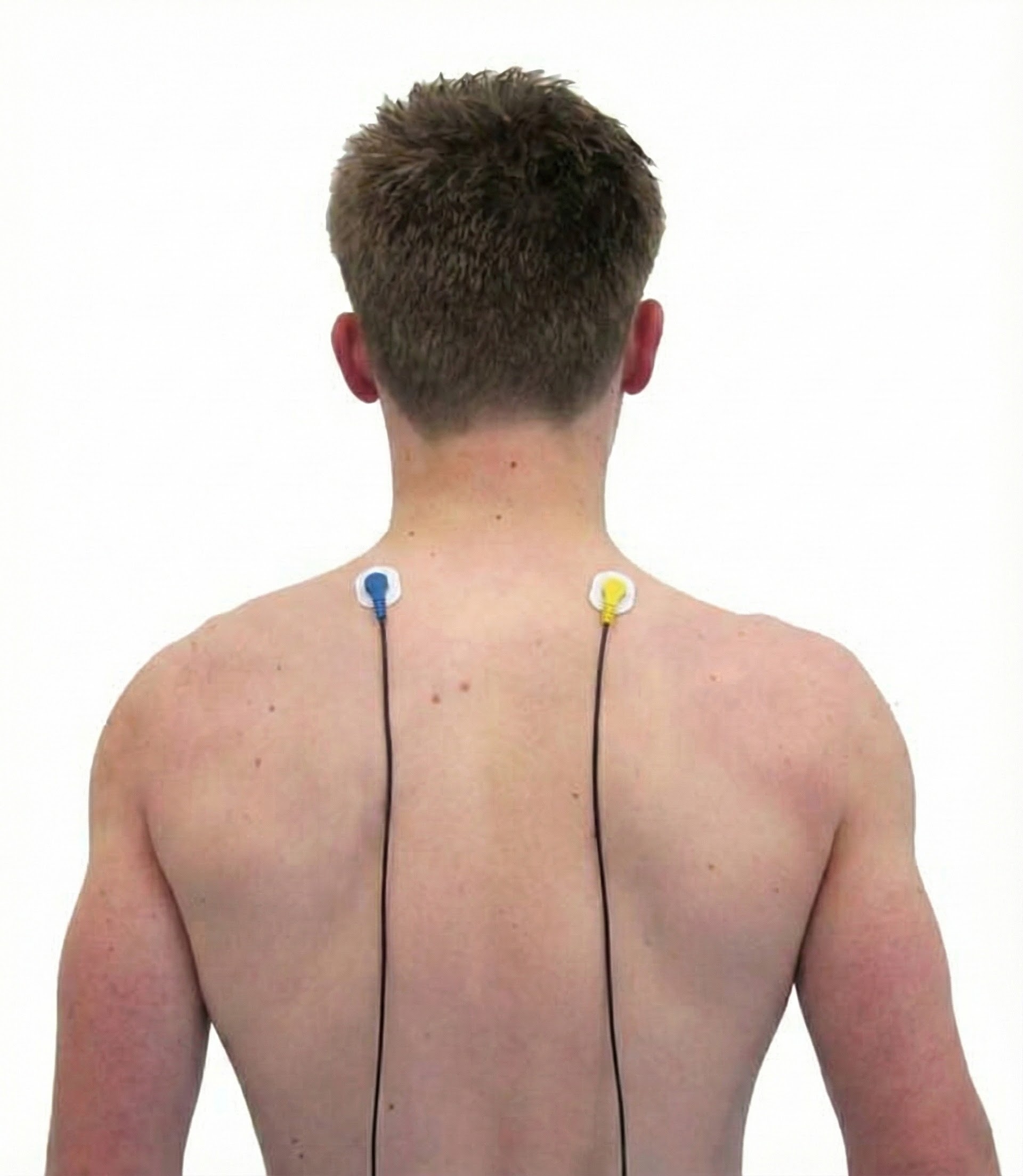

Latissimus Dorsi

Extensor Carpi Ulnaris

Abductor Pollicis Brevis

Adductor Pollicis

Vastus Lateralis (VL) and Vastus Medialis (VMO)

Tibialis Anterior

Gastrocnemius

Erector Spinae (Sacrospinalis)

Cutting Edge: Research Frontiers in Skeletal Muscle Science

The topics in this section represent some of the most exciting research frontiers in skeletal muscle science and biofeedback. These areas are still developing, with new studies appearing regularly, but they illustrate how the field is expanding beyond traditional applications.

Skeletal Muscles as Endocrine Glands: The Exerkine Revolution

Here is a finding that might surprise you: your skeletal muscles are not just engines for movement. They are also endocrine organs that secrete a variety of bioactive molecules known as exerkines during physical activity. These exerkines play significant roles in inter-organ communication and systemic physiological regulation.

For instance, Growth and Differentiation Factor 15 (GDF15) is identified as a novel exerkine secreted by skeletal muscle during exercise, which promotes lipolysis in human adipose tissue, highlighting its role in energy metabolism (Laurens et al., 2020). Additionally, skeletal muscles secrete other exerkines such as thymosin beta-4 (TMSB4X), which is upregulated during muscle contraction and has been implicated in cellular crosstalk, although its effects on metabolic disorders remain inconclusive (Gonzalez-Franquesa et al., 2021).

Furthermore, skeletal muscle-derived exerkines like apelin, kynurenic acid, and lactate have been shown to influence the progression of neurodegenerative diseases by mediating the muscle-brain axis, thus underscoring their therapeutic potential (Bian et al., 2024). This evidence collectively supports the concept of skeletal muscles functioning as glands that secrete exerkines, contributing to the regulation of various physiological processes and disease states.

A Gene That Promotes Muscle Strength Without Increasing Size

Physical activity activates a newly discovered C18ORF25 gene that increases muscle strength without always changing muscle size (Blazev et al., 2022). This finding suggests that the relationship between muscle size and strength is more complex than previously understood, opening new avenues for understanding how exercise produces its beneficial effects at the molecular level.

Muscle Synergies: How Your Brain Coordinates Complex Movements

Have you ever wondered how your nervous system coordinates dozens of muscles to perform something as simple as reaching for a coffee cup? Researchers are increasingly finding that your brain does not control each muscle individually. Instead, it uses muscle synergies, which are preset patterns of muscle activation that get combined and scaled to produce complex movements (Jarque-Bou et al., 2021; Scano et al., 2024).

Think of muscle synergies like chords on a piano. Rather than pressing one key at a time, a pianist plays chords, which are combinations of notes that sound good together. Similarly, your nervous system activates groups of muscles together in reliable patterns. Studies using high-density EMG on the forearm and hand have shown that these synergies remain remarkably stable across many everyday tasks, whether you are gripping a doorknob or typing on a keyboard (Geng et al., 2022; Jarque-Bou et al., 2021).

Here is where it gets exciting for biofeedback: EMG-guided training can actually help you develop new synergies. In one study, adults who practiced controlling their elbow flexor EMG while watching visual feedback developed brand-new coordination patterns while keeping their original ones intact (Seo et al., 2023). They essentially expanded their "library" of available movement patterns. Research in sports and rehabilitation shows that synergy structure can change with skill development, fatigue, or neurological disease, but importantly, it can also be improved with targeted practice and therapy (Lanzani et al., 2025; Scano et al., 2024). For EMG biofeedback clinicians, this means that training even a single muscle channel can, over weeks of practice, reshape how multiple muscles coordinate together to support recovery or enhance performance.

From Muscle Activation to Force: What EMG Can and Cannot Tell You

A question students often ask is: "If I see higher EMG readings, does that mean the muscle is producing more force?" The answer is more complicated than you might expect, and understanding this relationship is crucial for interpreting biofeedback data correctly.

Recent consensus work from leading EMG researchers concludes that EMG is excellent for detecting when force production starts and stops and for tracking relative changes in muscle activation. However, EMG is rarely accurate for estimating the absolute amount of force a muscle produces without sophisticated biomechanical models that account for muscle length, how fast the muscle is contracting, and the elastic properties of tendons (Dick et al., 2024; Sartori et al., 2012). Mathematical models that simulate motor unit recruitment and EMG generation confirm that the relationship between EMG amplitude and force is highly nonlinear and depends on the mix of motor unit sizes and their firing rates within a muscle (Petersen & Rostalski, 2019).

Anatomical factors also play a significant role. Greater distance between the muscle and the electrode (often due to thicker layers of fat and skin) reduces the strength and clarity of the EMG signal. This affects both the raw interference pattern you see on the screen and more advanced techniques that try to identify individual motor unit activity (de Oliveira et al., 2022; Sampieri et al., 2025). The practical lesson for students and clinicians using EMG biofeedback is this: treat EMG primarily as a window into neural activation patterns rather than a direct measure of force. Combine your EMG readings with knowledge of muscle anatomy and biomechanics when drawing conclusions about what the muscle is actually doing (Avila et al., 2023; Dick et al., 2024).

Comprehension Questions: Cutting Edge Topics

- What are exerkines, and why is their discovery significant for understanding the role of skeletal muscles in overall health?

- How does the discovery of exerkines change our understanding of skeletal muscle function beyond movement?

- What does the C18ORF25 gene research suggest about the relationship between muscle size and strength?

- How might exerkines that influence the muscle-brain axis have therapeutic potential for neurodegenerative diseases?

- What are muscle synergies, and how do they help explain how the nervous system coordinates complex movements?

- How might EMG biofeedback training help someone develop new muscle synergies?

- Why is EMG not a direct measure of muscle force, and what factors influence the EMG-force relationship?

- How do anatomical factors like subcutaneous fat affect the quality of EMG recordings?

Glossary

amplitude: the strength of an EMG signal that is measured in microvolts.

angle of the acromion: the site posterior to the bony triangle at the top of the shoulder.

annulospiral receptors: muscle spindle length receptors that stretch as a muscle lengthens and activate alpha motor neurons to strengthen muscle contraction to increase muscle tone.

antagonist: a muscle that opposes a prime mover's action and yields to its movement. For example, the triceps brachii (antagonist) opposes flexion by the biceps brachii (prime mover or agonist).

biceps brachii: a muscle that flexes and supinates the forearm. Active electrodes are centered over the bulge in this muscle.

cardiac muscle: muscle fibers that comprise most of the heart wall. These fibers have crossed striations that allow the heart to pump and contain the same actin and myosin filaments, bands, zones, and Z discs as skeletal muscles.

concentric contraction: fibers shorten as your body moves upward, for example, a pull-up.

connectin: another name for titin, a structural protein that links a Z disc to the M line in the center of a sarcomere.

deltoid: synergist that along with the pectoralis major muscle anchors both the arm and shoulder when the biceps brachii (agonist) contracts to flex the forearm.

depressors: muscles that produce downward movement. For example, the latissimus dorsi lowers the shoulder blades and shoulder girdle.

dorsiflexors: muscles that point the toes toward the shin (superiorly) through flexion at the ankle joint. For example, the tibialis anterior dorsiflexes and inverts the foot during the swing phase of walking.

eccentric contraction: fibers lengthen as you lower yourself, for example, when performing a squat.

efferent nerves: nerves like alpha motor neurons that leave the central nervous system.

electromyography (EMG): a method for recording the electrical signals produced when skeletal muscle fibers are activated by motor neurons, using either surface electrodes placed on the skin or fine-wire electrodes inserted into the muscle.

end plate potential (EPP): the depolarization of the motor end plate caused by ACh release, which triggers a muscle action potential.

erector spinae (sacrospinalis): a muscle that maintains the erect position of the spine and extends the vertebral column.

evertors: muscles that turn the sole of a foot outward. For example, fibularis longus/tertius are the primary eversion muscles.

exerkines: a group of signaling molecules released during exercise that plays a crucial role in mediating its systemic benefits, including improved metabolism, cardiovascular health, and cognition.

extensors: muscles that increase the angle between two bones. For example, the triceps brachii extends the forearm.

extrafusal fibers: skeletal muscle fibers that are striated (striped) due to alternating light and dark bands.

fascia: fibrous connective tissue that divides muscles into functional groups, aids muscle movement, transmits force to bones, encloses and supports blood vessels and nerve fibers, and secures organs in their place.

fascicles: muscle fiber bundles.

fast glycolytic (FG) fibers: white fibers that are poor in myoglobin, mitochondria, and capillaries but contain extensive stores of glycogen. FG fibers produce ATP using anaerobic metabolism that cannot continuously supply needed ATP, causing these fibers to fatigue easily.

fast oxidative-glycolytic (FOG) fibers: red fibers that are rich in myoglobin, mitochondria, and capillaries. Their capacity to produce ATP through oxidative metabolism is high, and FOG fibers split ATP rapidly producing high contraction velocities.

filaments: the thin (actin) and thick (myosin) protein structures that comprise myofibrils and enable muscle contraction.

fixators: muscles that stabilize a prime mover's origin for more efficient action.

flexors: muscles that decrease the angle between two bones. For example, the biceps brachii flexes and supinates (turns up) the forearm.

frontales: a muscle that draws the scalp forward, raises eyebrows, and wrinkles the forehead. The actives are located between the eyebrows and hairline.

gastrocnemius: a muscle that plantar flexes the foot and flexes the knee joint. Active electrodes are centered vertically over the bulges of either head of this muscle.

Golgi tendon organs: force detectors that lie in series with skeletal muscle fibers. When excessive contraction threatens to damage muscle and tendon, they inhibit the responsible alpha motor neurons to prevent injury.

H bands: narrow central region in each A band containing only thick filaments.

I bands: lighter, less dense region of a sarcomere that contains the remaining thin but no thick filaments and is bisected by a Z disc.

insertion: the more movable bone at a joint where a muscle tendon attaches.

invertors: muscles that turn the sole of a foot inward. For example, the tibialis posterior and tibialis anterior are the primary invertors.

isometric contraction: a contraction in which muscles produce tension with minimal fiber shortening.

isotonic contraction: a contraction in which muscles produce movement by exerting tension on an attached structure (bone).

levators: muscles that produce upward movement. For example, the levator scapulae elevates the shoulder blades.

M line: central region of an H zone, located at the center of a sarcomere, that contains the proteins that connect thick filaments.

masseter: a muscle that elevates and protracts the mandible. The actives are located using the angle of the jaw as a landmark.

monosynaptic stretch reflex: a reflex that maintains postural muscle tone and stabilizes limb position by correcting increases in muscle length.

motor endplate: the muscle fiber beneath a terminal branch of an alpha motor neuron.

motor unit: an alpha motor neuron and the muscle fibers it controls.

muscle action potential (MAP): a depolarizing impulse that travels along the sarcolemma and T tubules, producing the EMG signal and initiating skeletal muscle contraction.

muscle-electrode distance: the thickness of tissue, mainly fat and skin, between the active muscle fibers and the recording electrode, which affects how strongly and clearly EMG signals are detected.

muscle mechanics: the way muscles and tendons generate and transmit force, including the effects of muscle length, contraction speed, and elastic tendons on how activation translates into movement.

muscle spindles: stretch receptors that lie in parallel with skeletal muscle fibers and trigger the monosynaptic stretch reflex.

muscle synergies: reusable patterns of coordinated activation across several muscles that the nervous system scales and combines to produce complex movements more efficiently.

myofibrils: each skeletal muscle fiber comprises hundreds to thousands of these units built from thin and thick filaments.

myomesin: structural protein that comprises a sarcomere's M line, binds to titin, and connects adjacent thick filaments.

myosin: contractile protein that comprises thick filaments; a single molecule contains two heads that bind to sites on actin during muscle contraction.

neuromuscular junction (NMJ): the synapse between an alpha motor neuron and a skeletal muscle.

nicotinic ACh receptor: an ionotropic receptor on the skeletal muscle endplate that binds two ACh molecules to allow sodium ions to enter the muscle fiber.

origin: the more stationary bone at a joint where a muscle tendon attaches.

passive tension: the force generated by connective tissue elasticity, allowing muscle fibers to produce, sum, and transmit force.

plantar flexors: muscles that point the toes downward (inferiorly) through extension at the ankle joint.

power strokes: after actin and myosin filaments form cross bridges, myosin moves actin inward, breaks contact, binds to actin, and then repeats this process.

prime mover (agonist): a muscle directly responsible for producing a specific movement and is opposed by an antagonist.

pronators: muscles that turn the palm downward (posteriorly).

proprioceptive feedback: information about body position and movement.

refractory period: 1-millisecond interval during which skeletal muscles lose their excitability to prevent exhaustion.

rotators: muscles that move a bone around a longitudinal axis.

sarcolemma: the skeletal muscle fiber membrane.

sarcomeres: skeletal muscle compartments separated by dense zones called Z discs; the smallest contractile unit of a muscle fiber.

SEMG: surface electromyogram; measures muscle action potentials from skeletal motor units.

single-unit smooth muscle: smooth muscle that comprises part of the walls of small arteries and veins, the stomach, intestines, uterus, and urinary bladder.

skeletal muscles: extrafusal muscles that move the bones of the skeleton and are striated (striped) muscles due to alternating light (I) and dark (A) bands.

slow oxidative (SO) fibers: red fibers rich in myoglobin, mitochondria, and capillaries with a high capacity to produce ATP through oxidative metabolism. Highly resistant to fatigue.

smooth muscle: single-unit and multi-unit muscle fibers whose contraction starts more gradually and persists longer than skeletal muscle contraction.

sodium-potassium pump: the mechanism that exchanges sodium ions for potassium ions to restore the muscle fiber to a resting negative voltage.

striated: striped. For example, skeletal muscle fibers are striped due to thin (light) and thick (dark) filaments.

supinators: muscles that turn the palm upward (anteriorly).

surface high-density EMG (HD-EMG): a technique that uses a grid of many closely spaced surface electrodes to map spatial patterns of muscle activity and, in some cases, to separate individual motor unit discharges.

synergists: muscles that stabilize a joint to reduce the origin's interference with movement.

temporalis: a muscle that elevates and retracts the mandible (jaw).

tendon: connective tissue that connects muscle to bone and transmits the force of muscle contraction.

tendon reflex: protective mechanism in which Golgi tendon organs inhibit alpha motor neurons when excessive contraction threatens to damage muscle and tendon.

tensors: muscles that make a body part more rigid.

thick filaments: dark-colored filaments that are mainly composed of myosin.

thin filaments: light-colored filaments that are mainly composed of actin.

tibialis anterior: a muscle that dorsiflexes and inverts the foot.

titin: a structural protein that links a Z disc to the M line in the center of a sarcomere to stabilize the thick filament position and contribute to myofibril elasticity and extensibility.

triceps brachii (lateral head): a muscle that extends the elbow joint.

tropomyosin: a regulatory protein component of thin filaments that prevents myosin heads from binding to actin when a muscle fiber is relaxed.

troponin: a regulatory protein component of thin filaments that changes shape when calcium ions bind, removing tropomyosin from covering myosin-binding sites to allow the formation of cross-bridges and muscle contraction.

upper trapezius: a muscle that rotates and elevates the scapula (shoulder blade), extends, flexes, and turns the head and neck.

vastus lateralis (VL) and vastus medialis (VMO): muscles that extend the leg at the knee joint.

Z discs: thin, plate-shaped dense zones that separate sarcomeres.

zygomaticus: a muscle that draws the corner of the mouth upward and outward when you smile.

Test Yourself

Click on the ClassMarker logo to take 10-question tests over this unit without an exam password.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Visit the BioSource Software Website

BioSource Software offers Human Physiology, which satisfies BCIA's Human Anatomy and Physiology requirement, and Biofeedback100, which provides extensive multiple-choice testing over BCIA's Biofeedback Blueprint.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this module, identify the muscles you monitor and train in your clinical practice using the muscle diagrams shown above.

References

Andreassi, J. L. (2007). Psychophysiology: Human behavior and physiological response (5th ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, Inc.

Avila, E. R., Williams, S., & Disselhorst-Klug, C. (2023). Advances in EMG measurement techniques, analysis procedures, and the impact of muscle mechanics on future requirements for the methodology. Journal of Biomechanics, 153, 111501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2023.111501

Basmajian, J. V., & Blumenstein, R. (1980). Electrode placement in EMG biofeedback. Williams & Wilkins.

Bian, X., Wang, Q., Wang, Y., & Lou, S. (2024). The function of previously unappreciated exerkines secreted by muscle in regulation of neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2023.1305208

Blazev, R., Carl, C. S., Ng, Y.-K., Molendijk, J., Voldstedlund, C. T., Zhao, Y., Xiao, D., Kueh, A. J., Miotto, P. M., Haynes, V. R., Hardee, J. P., Chung, J. D., McNamara, J. W., Qian, H., Gregorevic, P., Oakhill, J. S., Herold, M. J., Jensen, T. E., Lisowski, L., Lynch, G. S., Dodd, G. T., Watt, M. J., Yang, P., Kiens, B., Richter, E. A., & Parker, B. L. (2022). Phosphoproteomics of three exercise modalities identifies canonical signaling and C18ORF25 as an AMPK substrate regulating skeletal muscle function. Cell Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2022.07.003

Bolek, J. E., Rosenthal, R. L., & Sherman, R. A. (2016). Advanced topics in surface electromyography. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.). Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Breedlove, S. M., & Watson, N. V. (2023). Behavioral neuroscience (10th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc.

Bromberg, M. B. (2020). The motor unit and quantitative electromyography. Muscle & Nerve, 61(2), 127-141. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26735

Buchthal, F., & Schmalbruch, H. (1980). Motor unit of mammalian muscle. Physiological Reviews, 60(1), 90-142. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1980.60.1.90

Carr, J. J., & Brown, J. M. (1981). Introduction to biomedical equipment technology. John Wiley & Sons.

Cram, J. R. (2011). E. Criswell (Ed.). Cram's introduction to surface electromyography (2nd ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

de Oliveira, D. S., Casolo, A., Balshaw, T. G., Maeo, S., Lanza, M. B., Martin, N. R. W., Maffulli, N., Kinfe, T. M., Eskofier, B. M., Folland, J., Farina, D., & Del Vecchio, A. (2022). Neural decoding from surface high-density EMG signals: Influence of anatomy and synchronization on the number of identified motor units. Journal of Neural Engineering, 19(3), 036020. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ac6e8b

Dick, T. J. M., Tucker, K., Hug, F., Besomi, M., van Dieën, J. H., Enoka, R. M., Besier, T. F., Carson, R. G., Clancy, E. A., Disselhorst-Klug, C., Falla, D., Farina, D., Gandevia, S. C., Holobar, A., Kiernan, M. C., Lowery, M. M., McGill, K. C., Merletti, R., Perreault, E. J., Rothwell, J. C., Søgaard, K., Wrigley, T. V., & Hodges, P. W. (2024). Consensus for experimental design in electromyography (CEDE) project: Application of EMG to estimate muscle force. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 79, 102985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2024.102985

Florimond, V. (2009). Basics of surface electromyography applied to physical rehabilitation and biomechanics. Thought Technology Ltd.

Fox, I., & Rompolski, K. (2022). Human physiology (16th ed.). McGraw Hill.

Geng, Y., Chen, Z., Zhao, Y., Cheung, V., & Li, G. (2022). Applying muscle synergy analysis to forearm high-density electromyography of healthy people. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16, 1084370. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.1084370

Gonzalez-Franquesa, A., Stocks, B., Borg, M., Kuefner, M., Dalbram, E., Nielsen, T., Agrawal, A., Pankratova, S., Chibalin, A., Karlsson, H., Gheibi, S., Bjornholm, M., Jorgensen, N., Clemmensen, C., Treebak, J., Hostrup, M., Krook, A., Zierath, J., & Deshmukh, A. (2021). Discovery of thymosin beta-4 as a human exerkine and growth factor. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00263.2021

Hall, J. E., & Hall, M. E. (2010). Guyton and Hall's textbook of medical physiology (14th ed.). Elsevier.

Jadali, C. (2021). Personal communication regarding skeletal muscle anatomy and function, and clinical syndromes.

Jarque-Bou, N. J., Sancho-Bru, J. L., & Vergara, M. (2021). A systematic review of EMG applications for the characterization of forearm and hand muscle activity during activities of daily living: Results, challenges, and open issues. Sensors, 21(9), 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/s21093067

Lanzani, V., Brambilla, C., & Scano, A. (2025). A methodological scoping review on EMG processing and synergy-based results in muscle synergy studies in Parkinson's disease. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 13, 1437730. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2024.1437730

Laurens, C., Parmar, A., Murphy, E., Carper, D., Lair, B., Maes, P., Vion, J., Boulet, N., Fontaine, C., Marques, M., Larrouy, D., Harant, I., Thalamas, C., Montastier, E., Caspar-Bauguil, S., Bourlier, V., Tavernier, G., Grolleau, J., Bouloumie, A., Langin, D., Viguerie, N., Bertile, F., Blanc, S., De Glisezinski, I., O'Gorman, D., & Moro, C. (2020). Growth and Differentiation Factor 15 is secreted by skeletal muscle during exercise and promotes lipolysis in humans. JCI Insight. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.131870

Laycock, J., & Haslam, J. (Eds.). (2008). Therapeutic management of incontinence and pelvic pain: Pelvic organ disorders (2nd ed.). Springer.

Lee, T., & Kaufman, J. (2017). Personal communication regarding biofeedback training for urinary incontinence.

Marieb, E. N., & Hoehn, K. N. (2019). Human anatomy & physiology (11th ed.). Pearson.

Neblett, R. (2012). BCIA Clinical Update Series: Active SEMG Biofeedback for Chronic Pain, Part I.

Petersen, E., & Rostalski, P. (2019). A comprehensive mathematical model of motor unit pool organization, surface electromyography, and force generation. Frontiers in Physiology, 10, 374. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00374

Sampieri, A., Spinello, G., Franchi, M. V., Campa, F., Paoli, A., Moro, T., & Casolo, A. (2025). Greater muscle electrode distance and fat mass affect motor units identification from high-density surface EMG in the vastus lateralis muscle. Scientific Reports, 15, 12345. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-XXXXX

Sartori, M., Reggiani, M., Farina, D., & Lloyd, D. G. (2012). EMG-driven forward-dynamic estimation of muscle force and joint moment about multiple degrees of freedom in the human lower extremity. PLoS ONE, 7(12), e52618. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052618

Scano, A., Lanzani, V., & Brambilla, C. (2024). How recent findings in electromyographic analysis and synergistic control can impact on new directions for muscle synergy assessment in sports. Applied Sciences, 14(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14010123

Seo, G., Park, J.-H., Park, H.-S., & Roh, J. (2023). Developing new intermuscular coordination patterns through an electromyographic signal-guided training in the upper extremity. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 20(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-023-01176-0

Shaffer, F., & Neblett, R. (2010, Summer). Practical anatomy and physiology: The skeletal muscle system. Biofeedback, 38(2), 47-51.

Sherman, R. (2003). Instrumentation methodology for recording and feeding-back surface electromyography (SEMG) signals. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 28(2), 107-119.

Sherman, R. (2010). Personal communication.

Soderberg, G. L. (1992). Selected topics in surface electromyography for use in the occupational setting: Expert perspectives. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Stern, R. M., Ray, W. J., & Quigley, K. S. (2001). Psychophysiological recording (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Tassinary, L. G., Cacioppo, J. T., & Vanman, E. J. (2007). The skeletomotor system: Surface electromyography. In J. T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, & G. G. Berntson (Eds.). Handbook of psychophysiology (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Tortora, G. J., & Derrickson, B. H. (2021). Principles of anatomy and physiology (16th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.