Neuromuscular Applications

What You Will Learn

Close your eyes and touch your nose. Easy, right? Now imagine losing that ability entirely. That invisible sense guiding your finger is called proprioception, and when neurological injury strips it away, patients lose their body's internal GPS. This chapter explores how biofeedback helps people recover movement when the brain-muscle communication system breaks down.

You will learn about three revolutionary approaches reshaping rehabilitation: Wolf's Socratic method that challenges patients to rediscover movement through problem-solving rather than mindless repetition, Bolek's quantitative surface electromyography (QSEMG) that trains whole muscle ensembles to accomplish real-world tasks like getting dressed, and Taub's counterintuitive Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) that forces patients to use their weakened limbs by literally tying down their healthy ones.

From stroke survivors relearning to walk to children with cerebral palsy gaining control of their bodies for the first time, you will discover why biofeedback has become an essential tool in the rehabilitation toolkit and why success depends on seamless collaboration with physical therapy teams.

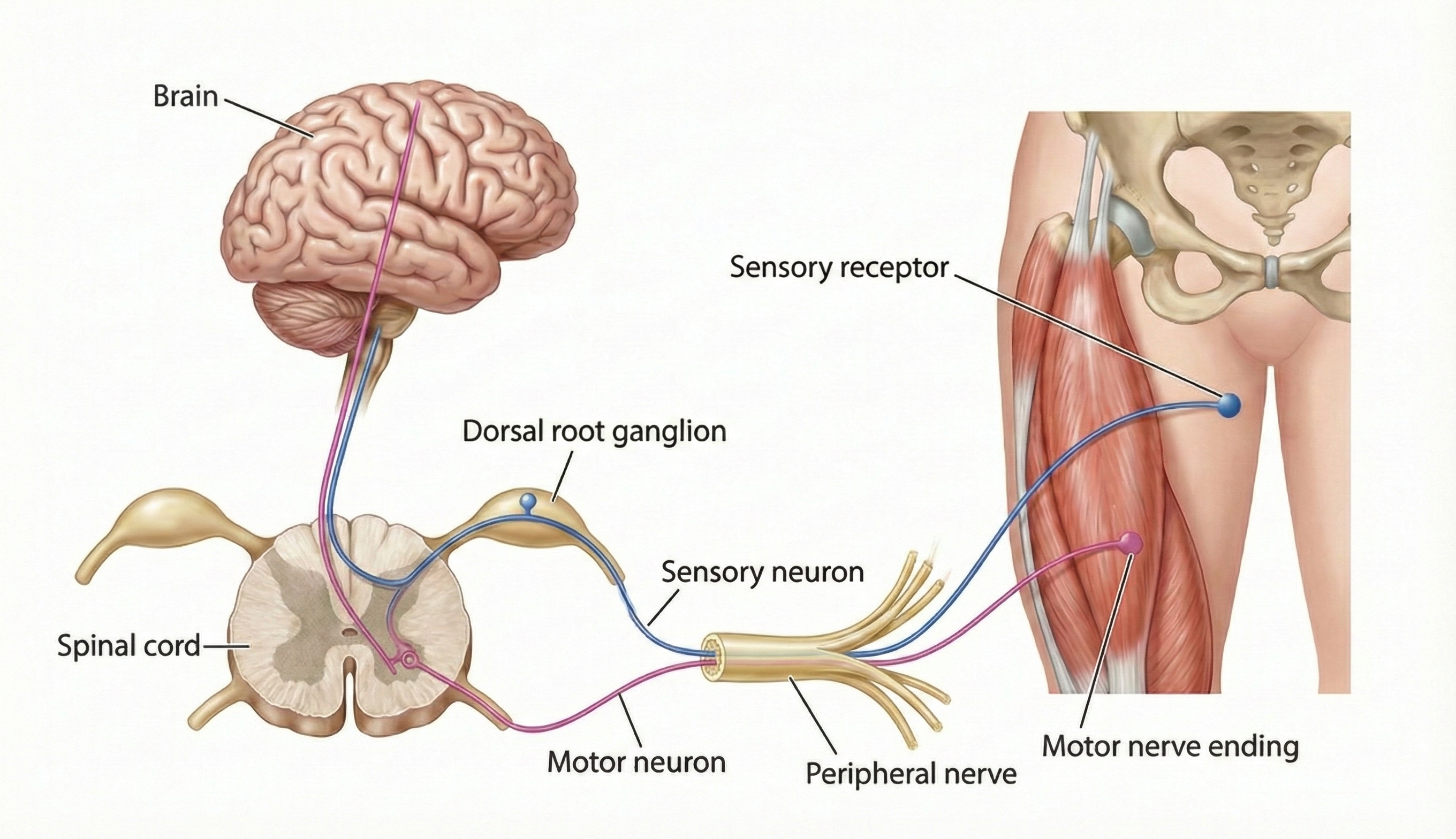

Every neuromuscular disorder covered in this chapter shares a surprising common thread: impaired proprioception. This often-overlooked sensory system lets you perceive balance, joint angles, movement speed, muscle tension, and body position without using your eyes. When you reach for a light switch in the dark, proprioception guides your hand. When you climb stairs while texting, proprioception keeps you from falling. This "sixth sense" relies on specialized receptors in your muscles, tendons, and joints that constantly stream position data to your brain. When neurological damage disrupts this feedback loop, patients do not just lose strength; they lose their sense of where their body exists in space.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Neuromuscular Disorders

Here is a troubling reality: surface electromyography (SEMG) biofeedback has proven effective for conditions ranging from stroke to cerebral palsy, yet most physical therapy and occupational therapy clinics do not offer it. Why? The reasons are frustratingly mundane: limited practitioner training and failure to meet the basic conditions for successful treatment (Bolek, 2020). This represents a massive missed opportunity. The research is clear: a majority of randomized controlled trials evaluating SEMG biofeedback for cerebral palsy and stroke have demonstrated meaningful functional improvements. Patients who could be walking are confined to wheelchairs, and patients who could be feeding themselves remain dependent on caregivers, simply because the treatment that might help them is not available at their local clinic.

Three innovative approaches are converging to transform rehabilitation outcomes. First, Steven Wolf champions a Socratic method that treats patients as problem-solvers rather than passive recipients of therapy. Instead of drilling patients on repetitive exercises, his approach asks them to figure out how to accomplish functional tasks, engaging their creativity and building genuine motor learning.

Second, Jeffrey Bolek's quantitative surface electromyography (QSEMG) recognizes that real-world movement requires orchestrated muscle teamwork, not isolated contractions. His method provides feedback from multiple muscle sites simultaneously, training patients to perform actual daily activities like reaching into a cabinet or walking across a room. Bolek (2016) makes a crucial point: restoring motor control does not automatically translate into functional movement, so clinicians must train patients on the specific tasks they need to perform in their lives.

Third, Edward Taub's Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) tackles the insidious problem of "learned non-use." When a stroke patient's affected arm fails repeatedly, they naturally stop trying to use it, creating a vicious cycle that rewires the brain to ignore the limb entirely. Taub's counterintuitive solution: restrain the healthy limb for most of waking hours, forcing intensive practice with the affected one. This combination of physical therapy, behavioral psychology, and biofeedback has produced remarkable recoveries in patients written off as hopeless.

The biofeedback toolkit for neuromuscular disorders extends well beyond EMG. Depending on the patient's specific deficits, rehabilitation professionals may employ force feedback to train weight-bearing, electrogoniometers to monitor joint angles, accelerometers to track tremor, real-time ultrasound imaging to visualize deep muscles, or camera-based motion capture systems for comprehensive movement analysis. The principle guiding modality selection is simple but important: use whichever feedback method most directly measures what you are trying to change.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit discusses the Central nervous system (IV-B), General treatment considerations (IV-D), and Target muscles, typical electrode placements, and SEMG treatment protocols for specific neuromuscular conditions (IV-E).

This unit covers Motor Control Systems, Stroke, Spinal Cord Injury, Cerebral Palsy, Multiple Sclerosis, Peripheral Nerve Injury, and Torticollis.

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter Lecture

Evidence-Based Practice (4th ed.)

The efficacy ratings for clinical applications covered in this chapter have been updated based on AAPB's Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

Motor Control Systems: How the Brain Commands Movement

Your motor system works like a corporate hierarchy: executives plan strategy while workers execute it. Higher brain regions handle movement planning; lower regions carry out the actual commands.

The prefrontal cortex sits at the top, handling attention and high-level planning. Before you reach for a coffee cup, your prefrontal cortex has already evaluated whether it is within reach and whether grabbing it might knock over your papers. Below this, the premotor cortex adjusts motor programs based on sensory input from the environment, while the primary motor cortex serves as the final command center that executes movements.

Research by Graziano and Aflalo (2007) revealed something with profound implications for rehabilitation: motor regions do not map individual muscles. Instead, they map meaningful behaviors. Stimulate one spot in a monkey's brain, and it reaches toward its mouth; stimulate another, and it assumes a defensive posture. The takeaway for biofeedback practice is clear: we should train patients to perform meaningful activities, not isolated muscle twitches.

The primary motor cortex sends commands down two pathways. The corticospinal tract provides fine motor control for your fingers, hands, and limbs. Upper motor neurons in the motor cortex send axons down through the brainstem; about 85% cross to the opposite side at the medulla. This crossing explains why left brain damage causes right-sided paralysis. These upper motor neurons connect with lower motor neurons in the spinal cord, which activate the muscles directly. About 15% of fibers remain uncrossed, providing bilateral connections that become clinically important in rehabilitation techniques like Wolf's motor copy procedure.

Both descending pathways also communicate with central pattern generators, spinal cord circuits that coordinate rhythmic movements like walking or chewing. These pattern generators let walking become semi-automatic once initiated, freeing your conscious brain for other tasks like conversation.

The motor control system operates hierarchically: the prefrontal cortex plans, the premotor cortex adjusts, and the primary motor cortex executes commands through descending tracts. The corticospinal tract provides fine motor control; central pattern generators coordinate repetitive movements. For rehabilitation, the key insight is that motor areas map behaviors rather than isolated muscle contractions, supporting functional training approaches.

Comprehension Questions: Motor Control Systems

- Why is the finding that motor cortex maps behaviors rather than specific movements significant for rehabilitation?

- What role do central pattern generators play in movement, and how might this be relevant to gait training?

Stroke: When Blood Supply Fails the Brain

Every 40 seconds, someone in the United States has a stroke. Let that sink in. By the time you finish reading this section, dozens of Americans will have experienced a brain attack that may leave them unable to walk, talk, or care for themselves. Each year, more than 795,000 people in this country alone suffer strokes, making it the condition biofeedback practitioners will encounter most frequently (Martin et al., 2024).

In the United States, roughly 87% of strokes are ischemic (caused by blocked blood vessels starving brain tissue of oxygen) while 13% are hemorrhagic (caused by bleeding that damages surrounding neurons). What makes recent trends especially alarming is that stroke is no longer just a disease of the elderly.

CDC data reveal that stroke prevalence increased 7.8% between 2011-2013 and 2020-2022, with the sharpest increases occurring among younger adults: a 14.6% rise among those aged 18-44 and a 15.7% increase among those aged 45-64 (Imoisili et al., 2024). Researchers attribute these disturbing trends to the rising tide of cardiovascular risk factors, including obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, among working-age Americans.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Cerebrovascular Accident

The medical term for stroke is cerebrovascular accident (CVA), which refers to the destruction of brain tissue (specifically upper motor neurons) when blood vessels supplying the brain fail. To understand what stroke does to movement, remember that higher motor centers normally keep lower centers in check, like a manager supervising an energetic employee. When stroke destroys these upper motor neurons, the lower motor neurons are released from inhibition, often resulting in flexor hypertonicity (excessive muscle tension) and spasticity (Bolek et al., 2016). The patient's muscles are not weak; they are fighting each other.

CVAs show abrupt onset and involve temporary or permanent neurological symptoms like aphasia, paralysis, or loss of sensation.

Types of Stroke

Cerebral ischemia occurs when blood supply to the brain drops below the level needed to keep neurons alive. Brain cells are metabolic gluttons, consuming about 20% of your body's oxygen despite comprising only 2% of your body weight. Starve them of blood for even a few minutes, and they begin to die. Ischemia can cause loss of consciousness and permanent brain damage.

Three main culprits cause ischemic strokes: arteriosclerosis (when artery walls harden and narrow over years of high blood pressure and cholesterol buildup), thrombosis (when a blood clot forms directly in a brain artery), and embolism (when a clot forms elsewhere in the body, breaks loose, and lodges in a brain artery).

Cerebral hemorrhage represents the other major category: a blood vessel ruptures and blood floods into brain tissue, mechanically crushing and chemically poisoning adjacent neurons. Hemorrhagic strokes often result from chronic high blood pressure that gradually weakens artery walls until they burst. Subarachnoid hemorrhages, which occur in the space between the brain and its protective covering, typically result from the rupture of a congenital aneurysm (a balloon-like weak spot in an artery wall that has been present since birth).

To clarify the terminology, a thrombosis is a clot that blocks circulation at the spot where it forms. Think of it as a roadblock built right on the highway. An embolism is a piece of debris (air bubbles, blood clots, fat, or tumor cells) that travels downstream from a larger blood vessel until it gets stuck in a smaller one. Think of it as a log floating down a river until it jams in a narrow passage. Emboli cause nearly three-quarters of all ischemic strokes.

Here is a sobering fact that every biofeedback practitioner should understand: most of the brain damage from ischemic stroke does not happen immediately. The initial blood flow interruption kills some neurons instantly, but the majority of cell death unfolds over one to two days through a process called secondary injury.

Different brain regions show different vulnerabilities, with the hippocampus (critical for memory) being especially susceptible. The primary killer in this delayed destruction is excitotoxicity, a process where the brain essentially poisons itself with its own neurotransmitters.

Here is what happens: when blood flow drops, neurons lose the energy needed to maintain their membrane pumps. These pumps normally keep ions in their proper places. Without them, membranes depolarize wildly, causing neurons to dump massive amounts of glutamate (the brain's main excitatory neurotransmitter) into the synaptic cleft.

Neighboring neurons, flooded with this glutamate, activate their NMDA and AMPA receptors, which opens calcium channels. Calcium floods into the cells and activates enzymes that literally digest the neuron from the inside out, triggering programmed cell death (Neves et al., 2023). Glutamate may also destroy oligodendrocytes, the cells that produce myelin insulation for axons, through the same NMDA receptor mechanism (Salter & Fern, 2005).

Recent research has identified another cell death mechanism called ferroptosis. When hemoglobin from damaged blood vessels breaks down, it releases iron that catalyzes toxic oxidation reactions. Without adequate antioxidant defenses, lipid peroxides accumulate and destroy neuronal membranes (Fan et al., 2023; Tuo & Lei, 2024).

Why does this matter for biofeedback practitioners? Because understanding that brain damage continues for days after stroke emphasizes why early intervention is so critical. The cells in the penumbra (the region surrounding the stroke core) are still alive but threatened. Early rehabilitation may help preserve them.

Time is Brain: The Critical First Hour

Diagnosis and treatment within the first hour are crucial for saving at-risk brain tissue. Every minute counts because neurons in the penumbra (the area surrounding the stroke core) can still be saved with rapid intervention.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Time is Brain

Recognizing Stroke Symptoms

The presence of weakness, speech difficulty, visual changes, facial droop, numbness or tingling, or dizziness can signal a stroke. The acronym FAST helps people remember warning signs: Face drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulty, Time to call emergency services.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Stroke Symptoms

What Stroke Does to Motor Systems

Stroke devastates the motor systems, producing the paralysis and weakness that make recovery so challenging. Wolf's research suggests that disruption of proprioception, not just motor output, may be the core problem. Patients cannot move properly partly because they cannot feel where their limbs are.

The pyramidal motor system provides precision movement, projecting from the motor cortex to spinal cord neurons. Damage anywhere along this pathway impairs fine motor control needed for writing, buttoning shirts, or using utensils. Immediately after injury, patients experience transient flaccid paralysis with complete muscle tone loss. This flaccid phase usually lasts only days to weeks before hyperreflexia develops, with reflexes becoming exaggerated and hair-trigger. This often progresses to spastic paralysis, where muscles remain partially contracted and resist movement.

Stroke can also produce apraxia when it damages brain regions that organize movement sequences. Patients with apraxia have functioning muscles but cannot coordinate movements productively. They may be physically capable of waving goodbye but cannot perform the action on command (Wilson, 2003).

The extrapyramidal motor system controls posture, balance, and gross movements. When damaged, hyperreflexia leads to spasticity, causing constant resistance to stretching. As patients try to move, stretch receptors trigger reflexes that jerk the limb back, producing ratcheting motion called clonus (Wilson, 2003).

Consider Connor, a 38-year-old architect who suffered a left hemisphere stroke three weeks ago. When he tries to extend his arm, his biceps contracts powerfully, pulling his arm back even though he is trying to straighten it. His biceps and triceps are in a tug-of-war, and his biceps is winning. This pattern, called agonist spasticity combined with antagonist paresis, represents the signature problem of stroke rehabilitation. His treatment plan includes immediate physical therapy to prevent "learned non-use" and EMG biofeedback to reduce excessive biceps tension while strengthening his weakened triceps.

In paresis, maximum effort fails to generate normal strength. In paralysis, there is no muscle activity. Both are frequently associated with spasticity in agonist muscles.

Physical therapy should begin as soon as the patient is stable, as early as two days post-stroke. While some patients recover fastest in the first few days, many improve for 6 months or longer. EMG biofeedback is incorporated to reduce spasticity, strengthen paretic muscles, and restore functional movement.

CVA Prognosis and Outcomes

The statistics are grim: roughly one in four stroke patients dies within a year of their first stroke. Among the survivors, about 90% will carry some degree of long-term disability in movement, sensation, memory, or cognition, ranging from mild inconveniences to catastrophic dependence. Understanding the natural trajectory of recovery is crucial for biofeedback practitioners because it helps set realistic expectations and identifies the windows when intervention has the greatest impact.

The brain's spontaneous neurological recovery follows a predictable pattern. Initial assessments of impairment can reasonably predict how much biological recovery will occur by 3 to 6 months for most survivors (Tong & Bhatt, 2023). The most dramatic gains typically occur during the first 3 months, when the brain's neuroplasticity is at its peak and the cellular machinery for reorganization is most active. However, here is the hopeful part: clinical experience consistently shows that patients continue improving beyond this spontaneous recovery period, even if the mechanisms driving later improvement are not fully understood.

The implications for biofeedback practice are clear: while the first months represent a critical window that should not be wasted, meaningful improvements remain possible even in chronic stroke, months or years after the event.

A 2025 systematic review examining nonmotor outcomes in stroke patients found that fatigue, cognitive impairment, and depression are extremely common, affecting substantial proportions of survivors at 6 months and persisting or even increasing at 12 months and beyond (Liu et al., 2025). The review emphasized that these nonmotor symptoms significantly impact rehabilitation participation and outcomes, highlighting why biofeedback practitioners should assess and address psychological factors alongside motor rehabilitation. Importantly, early rehabilitation timing correlates strongly with better outcomes.

A 2024 meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials involving 1,908 patients demonstrated that early rehabilitation significantly improved functional outcomes compared to delayed intervention (Chen et al., 2024). This evidence supports initiating biofeedback-assisted rehabilitation as soon as the patient is medically stable.

Wolf's Problem-Solving Approach to Recovery

Research by Wolf has shown that impaired proprioception may be central to loss of motor control following a CVA. If a CVA impairs a patient's ability to understand, follow, and remember instructions, this will prevent successful biofeedback training. For this reason, neurologists must evaluate a patient's cognitive performance before starting biofeedback-assisted physical therapy.

Wolf (2011) champions a problem-solving approach, instead of repetition, to teach patients to reacquire movement. He emphasizes learning to use an impaired extremity in functional activity instead of simple down-training and up-training of individual muscles. When patients cannot perform an activity, Wolf challenges them to explore new muscle recruitment patterns to overcome this challenge. Like Bolek's quantitative surface electromyography (QSEMG) approach, Wolf simultaneously trains multiple muscles. Like Taub, he incorporates Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT), in which he restricts clients to only use the unaffected limb 5 hours a day for 10 weeks.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Wolf's Socratic Approach

Physical Therapy Approaches

Physical rehabilitation procedures include diathermy, heat packs, or hot tubs to reduce spasticity; muscle relaxants like Flexeril to reduce spasticity; evaluation of range of motion and exercises to increase range of motion; immobilizing the unaffected limbs; and strength training.

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy: A Revolutionary Approach

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT) represents one of the most counterintuitive breakthroughs in rehabilitation medicine.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Taub's Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy

CIMT addresses "learned non-use." After stroke, patients try to use their affected limb, fail, and stop trying because failure is punishing. They shift to relying on their good limb, and their brain reorganizes around this pattern. The affected limb becomes neurologically orphaned as cortical territory gets reassigned.

Taub's solution: take away the compensation strategy. CIMT places the unaffected limb in a sling or padded mitt for 90% of waking hours over 2-3 weeks. Therapists apply intensive operant conditioning using shaping, reinforcing successive approximations of target behaviors and gradually demanding more precise, functional actions.

For lower limbs, limb load monitors and goniometers provide immediate feedback about gait. Taub (2005) noted: "The limb load monitor provides continuous feedback of the force and timing of each footfall."

Neuroimaging studies show that CIMT increases the cortical area controlling the affected limb through use-dependent reorganization. The EXCITE trial found that stroke patients with motor deficits persisting 3-9 months demonstrated significant improvements that persisted for at least one year (Wolf et al., 2006). Treatment effects are maintained at 2-year follow-up (Taub et al., 2002).

Modified Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (mCIMT) offers a more practical alternative with reduced constraint time (5-6 hours daily) and shorter sessions. A 2024 meta-analysis of 23 RCTs confirmed that mCIMT improves upper limb function, particularly in patients more than two months post-stroke (Liu et al., 2025).

Bolek's Quantitative Surface Electromyography

Jeffrey Bolek's quantitative surface electromyography (QSEMG) approach addresses a fundamental limitation of traditional biofeedback: real movement requires coordinated teamwork among multiple muscles, not isolated contractions. Bolek (2012, 2020) provides simultaneous feedback from multiple muscle sites, training the whole ensemble to perform functional tasks.

His core principles: focus on restoring functional movement rather than normalizing EMG readings; provide feedback about multiple muscle patterns during actual target activities; use engaging feedback like videos to maintain motivation; and gradually increase the delay between correct performance and reward to build endurance.

QSEMG calculates a functional time-domain score (FTDS) that assesses all monitored muscles simultaneously. The therapist assigns a goal for each target muscle (above or below threshold), and patients only receive reward when all muscles simultaneously meet their goals. This trains coordination rather than isolated control.

Managing Medications During Training

Doses of drugs like Flexeril that reduce spasms can produce fatigue, sleep, lethargy, and hypotension. Therapists should ask patients to hold a finger up in the air to prevent falling asleep. EMG training is still possible even though these drugs will lower EMG amplitude.

Biofeedback Treatment Strategy for Stroke

The core problem in stroke rehabilitation is that hyperactive agonist muscles and weak antagonist muscles prevent normal movement. Stroke produces hemiplegia, the paralysis of the upper extremity, trunk, and lower extremity muscles on one side.

Muscle testing reveals agonist spasticity (excessive muscle tone and tendon reflexes) and antagonist paresis (muscle weakness). EMG evaluation using percutaneous electrodes can establish whether antagonist muscles are innervated and can benefit from therapy. The treatment strategy is to reduce spasticity, increase recruitment in paretic muscles, and restore functional movement.

Wolf's Concurrent Assessment of Muscle Activity

In Wolf's (1985) Concurrent Assessment of Muscle Activity (CAMA), the clinician uses biofeedback information to suggest changes in ongoing patient posture, position, or movement. As the patient attempts the recommended change, the clinician can evaluate its effectiveness and provide new instructions.

Alternatively, the clinician can directly display information to the patient to modify performance. A feedback display provides more specific and immediate information to the patient than a therapist's instructions to "relax" or "try harder," which may follow observation and palpation by seconds.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Stroke Rehabilitation Principles

Electrode Placement for Stroke Rehabilitation

Narrow spacing (1 centimeter apart) is advised for weak antagonists (tibialis anterior) if spastic muscle (gastrocnemius) interference is a problem. If spastic muscles do not contaminate EMG readings, clinicians start with wider spacing (2-3 centimeters) over weak antagonists and progress from wide to narrow as the patient recovers. Wolf (1985) recommends the use of two EMG channels to monitor agonist and antagonist muscle groups simultaneously.

The gastrocnemius muscle is located at the back of the calf and is a common source of spastic interference when monitoring weaker antagonists.

SEMG Monitoring Guidelines

Clinicians should use a wide bandpass whenever possible, small sensors (12-15 mm), and place active sensors parallel to muscle striations.

Training Sequence

Rehabilitation follows a logical progression from proximal (trunk and shoulder) to distal (hand and fingers). Why this order? Because stable proximal control provides the platform needed for effective distal movement. You cannot perform delicate finger movements while your shoulder is flailing. Training might start with the anterior deltoid (front shoulder), then progress to the middle deltoid, wrist extensors, fingers, and finally the thumb. Each level provides the stable base needed for the next.

The position progression follows similar logic: start supine (lying on the back), progress to sitting, then standing, and finally walking. At each position, the therapist repeats the proximal-to-distal sequence. Early training focuses on reducing spastic muscle activity at rest and maintaining low EMG levels when muscles are passively stretched or stimulated by vibration.

The patient must first learn to relax spastic agonists before any attempt to strengthen weak antagonists. Once spastic muscles are under control at each position, the same sequence is repeated to build strength in paretic antagonists. Only in the final stage does training advance to purposeful movements like grasping a cup or walking across the room.

This systematic progression prevents the common mistake of attempting functional tasks before the patient has developed the underlying motor control to perform them safely.

Motor Copy Technique

Hemiplegia involves paralysis of only half of the body. Wolf (1985) uses a patient's bilateral control (rubrospinal and ventromedial tracts) over skeletal muscles in the motor copy technique.

The clinician asks the patient to contract an extensor on the unaffected side and then displays an EMG tracing of this effort. Next, the clinician asks the patient to match this tracing during the contraction of a mirror image extensor on the affected side. When patients successfully copy the healthy movement, they may have substituted bilateral for contralateral (lateral corticospinal tract) control.

Treatment Candidates and Predictors of Success

The main requirements for biofeedback-assisted rehabilitation are intact motor units that can be recruited and the ability to understand and remember instructions, localize a limb or joint in space, and interact with the therapist or instrument.

Loss of proprioception, receptive aphasia, and active shoulder range of motion may limit treatment outcome in upper extremity hemiplegic patients. Treatment outcome seems unrelated to age, sex, time since stroke, length of previous treatment, degree of expressive aphasia, or lesion site. For hemiplegics, reduced muscle hyperactivity during passive stretching and the ability to isolate wrist and finger movements may best predict improvement.

Biofeedback Modalities for Neuromuscular Disorders

Clinicians routinely monitor EMG activity, force, joint angle, and velocity when treating neuromuscular disorders.

EMG biofeedback measures muscle action potentials that precede the mechanical contraction of a muscle.

Force Feedback

Force feedback measures the physical pressure conducted through the body during movement, work, or exercise. This modality is especially valuable when the treatment goal is proper weight-bearing during standing or walking, something EMG cannot directly measure.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Force Feedback

Three ingenious force feedback devices supplement EMG biofeedback in rehabilitation. A feedback cane uses a strain gauge to detect pressure applied during walking. When the patient relies too heavily on the cane (exceeding a preset force threshold), a warning tone sounds, reminding them to bear more weight on their legs. The therapist can gradually lower the threshold over sessions, shaping the patient toward independent walking. Interestingly, the same device can work in reverse after hip replacement surgery, warning patients when they are not using the cane enough and risking injury to the healing joint.

A limb load monitor (LLM) uses force transducers placed in a shoe or floor platform to train hemiplegic patients in weight distribution. Many stroke patients unconsciously favor their unaffected leg when rising from chairs, sitting down, or standing. The LLM provides immediate feedback about this imbalance and helps patients learn to shift weight properly during the stance phase of walking.

A Cochrane Systematic Review by Barclay-Goddard and colleagues (2004) examined seven trials with 246 participants. While visual and visual plus auditory force platform feedback improved stance symmetry, they did not improve sway, clinical outcomes, or function.

A force transducer detects the force conducted through the body or hand during work or exercise.

Joint Angle Feedback

Joint angle feedback is used when we are concerned with the degree of knee extension or wrist pronation.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Joint Angle Feedback

This modality is measured by electrogoniometers, which reflect the change in joint angle by changing resistance to current. An electrogoniometer provides feedback for changes in joint angle, and a threshold can be selected to adjust joint position feedback. For example, excessive forearm extension can trigger a tone that is silenced when the joint angle falls below a threshold.

Velocity Feedback

Velocity feedback monitors variation in the movement of a body part. Symptoms like hand tremor can be measured by an accelerometer. A gyroscope measures rotational motion and is used to measure variation in wrist movement and hand tremor.

EMG biofeedback is not always the modality of choice. Muscles that control patient performance cannot always be monitored by surface or percutaneous electrodes. Further, the most direct performance index may be force, joint angle, or velocity instead of EMG level. Clinicians should use the biofeedback modality that most directly and immediately measures the treated symptom.

Real-Time Ultrasound Imaging and Camera-Based Systems

Real-time ultrasound (RTUS) imaging allows clinicians to visualize muscle contractions in real time, providing visual feedback about deep muscles that cannot be monitored with surface electrodes.

A network of cameras coupled with markers placed on a patient's body can provide quantitative 3-D analysis of dysfunctional movement. In sport psychology, this technology is used to help evaluate and improve an elite athlete's performance.

Stroke Treatment Outcomes

Here is a frustrating reality that biofeedback practitioners must understand: treatment outcomes are dramatically better for the lower extremities than the upper extremities. Wolf's (1982) data tell the story: only 20% of stroke patients regained independent use of their upper extremity, 30-40% improved without full recovery, and 30-40% showed no improvement at all. Compare this with lower extremity results: 60% achieved independent walking, 30% needed fewer assistive devices, and only 10% failed to improve.

Why such a dramatic difference? The answer lies in anatomical complexity and cortical real estate. The human hand is controlled by 34 different muscles that must coordinate with millisecond precision. The motor cortex devotes an enormous area to hand control, with the thumb alone commanding a region larger than the entire leg. This concentration of function makes the hand especially vulnerable to stroke damage.

If a stroke happens to hit the thumb region, recovery is severely limited because there is no backup system. Making matters worse, surface EMG recording from hand muscles is technically difficult due to the small surface area of the thenar eminence (the fleshy part of your palm below the thumb). The lower extremities, in contrast, rely on larger muscles with broader cortical representation and significant contributions from spinal pattern generators that may survive stroke intact.

Recovery Variables

Reduced spasticity and relationship with the patient may be important variables in patient recovery. Wolf (1982) believes that reduced agonist spasticity accounts for most improvement in neuromuscular rehabilitation. This makes sense since the antagonist opposes the agonist at a joint. Regular movements like extension (by the triceps) are prevented if the agonist (biceps) is spastic.

Wolf (1985) suggests that the therapist's relationship with the patient may also influence recovery. Patients may be more strongly motivated to participate in rehabilitation exercises when they perceive that the therapist is competent and cares about them.

Gait Training for Foot Drop

Foot drop is one of the most common and visible gait problems following stroke. Watch a patient with foot drop walk and you will notice their foot slapping the ground with each step and their toes dragging during swing phase. They often compensate by exaggeratedly lifting their knee or swinging their leg outward in a circular motion, creating an energy-wasting and unstable gait pattern.

The underlying problem involves a mismatch between two muscle groups. The dorsiflexors (tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus) are supposed to lift the foot and toes during the swing phase of walking. In foot drop, these muscles are weak or paralyzed. Meanwhile, the opposing plantar flexors (gastrocnemius and soleus) may be spastic, actively pulling the foot downward even when the patient is trying to lift it. The result is a foot that hangs limply or is pulled into a pointed position.

EMG-assisted rehabilitation attempts to strengthen dorsiflexors and evertors while reducing spasticity in opposing plantar flexors.

Research Evidence for Stroke Rehabilitation

Meta-analytical studies have found varying results for EMG biofeedback in the treatment of stroke patients. Earlier research by Schleenbaker and Mainous (1993) analyzed eight studies involving 192 patients and found that EMG biofeedback was helpful in treating hemiplegic stroke patients, with an impressive effect size of 0.81. Moreland, Thomson, and Fuoco (1998) concluded that EMG biofeedback produced greater ankle dorsiflexor strength than physical therapy but failed to improve ankle range of motion or angle during gait, gait quality or speed, or stride length.

EMG biofeedback has shown inconsistent effects on upper extremity function. Inglis and colleagues (1984) reported that EMG biofeedback contributed to upper limb performance when added to physiotherapy. However, Moreland and Thomson (1994) found that EMG biofeedback and physical therapy produced equivalent changes in upper extremity function. A Cochrane Systematic Review (Woodford & Price, 2007) of 13 studies examining 269 patients concluded that biofeedback did not significantly improve the outcome of standard physiotherapy.

More recent evidence has been more encouraging. A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis by Wang and colleagues examined 10 randomized controlled trials enrolling 303 participants and found that EMG biofeedback therapy significantly improved limb function after stroke (Wang et al., 2024). The analysis revealed a standardized mean difference of 0.44, indicating a small to moderate effect favoring biofeedback.

Subgroup analyses showed that short-term improvements (less than one month) were statistically significant, though evidence for long-term benefits remained limited. The review also found that EMG biofeedback significantly improved range of motion at the shoulder and wrist joints.

The authors emphasized that EMG biofeedback helps patients become aware of residual muscle activation even when visible movement is absent, which can facilitate earlier training initiation and guide the establishment of new movement patterns.

Neurofeedback for Stroke

Cannon, Sherlin, and Lyle (2010) reported treating a 43-year-old female patient diagnosed with a right hemisphere stroke. Fifty-two sessions of neurofeedback over six months successfully reduced theta power in the left parietal and central sites and increased beta power in the occipital lobe. QEEG changes were associated with improved self-reported cognitive performance, manual dexterity, and mood.

Clinical Efficacy Rating for Stroke

Based on 18 randomized controlled trials, Moss (2023) rated EMG biofeedback for stroke as level 4, efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). Several RCTs demonstrated functional improvements in joint angle and gait. These studies compared SEMG biofeedback-assisted physical therapy with physical therapy and sham feedback training. In most studies, SEMG biofeedback training contributed to functional improvement when added to standard care.

Stroke disrupts motor control by damaging upper motor neurons, resulting in characteristic patterns of spasticity and weakness. Rehabilitation proceeds from proximal to distal, training in progressively more demanding positions from supine to walking. The treatment strategy reduces agonist spasticity while strengthening antagonist muscles. Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy overcomes learned non-use by forcing patients to use affected limbs. EMG biofeedback for stroke is rated as efficacious, with stronger evidence for lower extremity than upper extremity function. Force, joint angle, and velocity feedback can supplement EMG biofeedback when they more directly measure the target symptom.

Comprehension Questions: Stroke

- Why do stroke patients often develop "learned non-use," and how does Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy address this problem?

- Explain why rehabilitation training proceeds from proximal to distal and from supine to standing positions.

- A patient's biceps is spastic when they try to extend their arm. What is happening physiologically, and what would the treatment strategy be?

- Why are outcomes generally better for lower extremity than upper extremity rehabilitation after stroke?

- What factors should a clinician consider when choosing between EMG biofeedback, force feedback, and joint angle feedback for a particular patient?

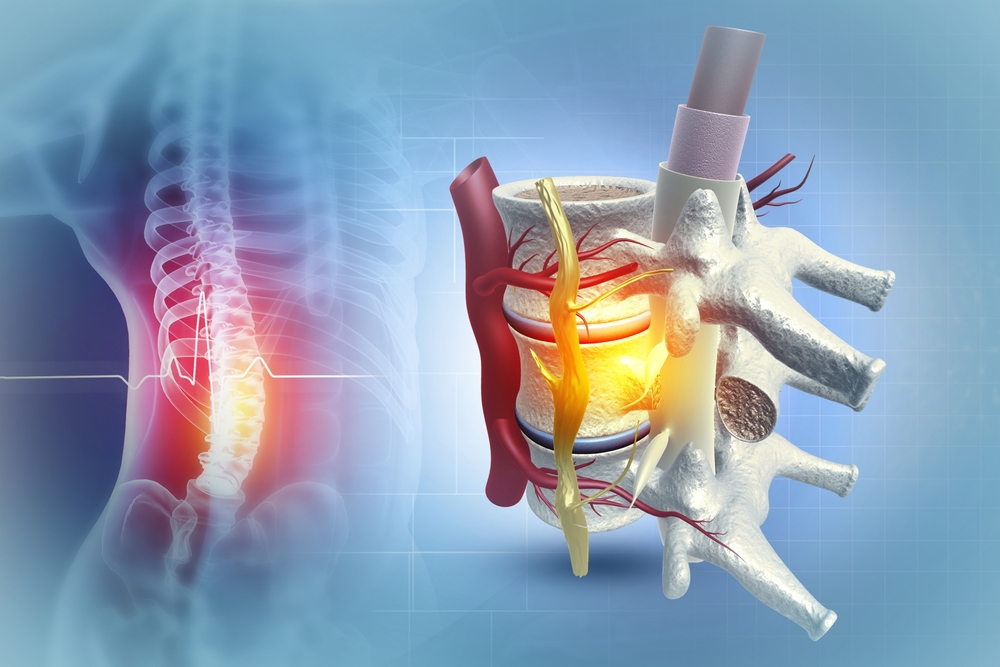

Spinal Cord Injury: When Communication is Interrupted

Spinal cord injury severs the connection between brain and muscles below the damage site. The injury unfolds in two phases. The primary injury involves immediate mechanical destruction. Over the following hours to weeks, secondary injury worsens cell death through inflammation, oxidative stress, and glutamate excitotoxicity (Sterner & Sterner, 2023). Early intervention can prevent further deterioration. Biofeedback-assisted rehabilitation is only attempted when the lesion is incomplete, meaning some motor neuron pools remain connected.

Approximately 305,000 Americans live with spinal cord injury, with roughly 18,000 new traumatic cases annually (National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center, 2024). The average age at injury has climbed from 29 years in the 1970s to 43 years since 2015, reflecting increased fall-related injuries among older adults. Motor vehicle accidents cause 38% of cases, falls 30%, and violence 13% (Chen et al., 2024).

The most critical prognostic factor is whether injury is complete or incomplete. Recovery following incomplete SCI is highly variable, with 20-75% recovering some walking capacity by one year. A 2024 study found 41% of cervical SCI patients improved over 3.7 years, with 51% regaining ambulation (Stenimahitis et al., 2024).

Fortunately, almost all spinal cord injuries are incomplete. Marked flexor spasticity appears 3-6 months post-injury; extensor spasticity starts around 6 months. EMG biofeedback helps both quadriparetic (four-limb weakness) and paraparetic (lower-limb weakness) patients. The treatment protocol follows the stroke approach: reduce agonist spasticity, train from proximal to distal, and progress through positions from supine to standing.

Petrofsky (2001) found that patients receiving continuous EMG biofeedback from a portable device during walking achieved near-normal gait after 2 months, outperforming those receiving only 30-minute daily sessions. Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.) did not rate EMG biofeedback for incomplete spinal cord lesion due to insufficient controlled research.

Comprehension Questions: Spinal Cord Injury

- Why is EMG biofeedback rehabilitation only attempted when a spinal cord lesion is incomplete?

- How might continuous biofeedback during walking produce better outcomes than brief training sessions?

Cerebral Palsy: Motor Disorders from Early Brain Damage

Cerebral palsy (CP) is not a single disease but a family of motor disorders resulting from irreversible brain damage that occurs before, during, or shortly after birth. Unlike stroke, which typically strikes adults with previously normal brains, CP affects developing brains that have never functioned normally, creating unique challenges and opportunities for rehabilitation.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Cerebral Palsy

Patients with CP can show any combination of three distinct motor problems. Flaccid paralysis features loss of muscle tone, diminished or absent reflexes, and muscle wasting. Spastic paralysis produces the opposite pattern: increased muscle tone, hyperactive reflexes, and pathological reflexes like the Babinski sign. Athetoid movements manifest as slow, continuous, writhing movements that the patient cannot control. Most patients experience spasticity, but many have a mixed presentation combining elements of all three.

Although the neurological deficits in CP resemble those in stroke, a crucial difference shapes treatment strategy. In stroke, the antagonist muscle is typically weak and needs strengthening. In CP, the antagonist often has normal or near-normal strength but is simply overpowered by a hypertrophied (abnormally enlarged) agonist that has developed from years of uncontrolled spastic activity. This distinction matters enormously for biofeedback practitioners: in CP, the primary goal is often reducing agonist hyperactivity rather than building up antagonist strength. Additionally, lower limb spasticity tends to be more pronounced in CP than in stroke, making gait training particularly challenging.

Demographics

Cerebral palsy is the most common motor disability in childhood. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, approximately 1 in 345 children (about 3 per 1,000 eight-year-old children) in the United States have been identified with cerebral palsy (Durkin et al., 2016). This translates to an estimated 764,000 children and adults currently living with cerebral palsy in the United States, with approximately 10,000 babies born each year who will develop the condition.

The prevalence of cerebral palsy is notably higher among children born preterm or at low birthweight. Racial disparities persist, with Black children approximately 29% more likely to have cerebral palsy compared to white children, and boys are diagnosed more frequently than girls. While the initial injury occurs between birth and age 2, diagnosis is usually made after age 1 following failure to meet developmental milestones (McIntyre et al., 2022; Thorogood & Alexander, 2005).

Causes and Types of Cerebral Palsy

The pathophysiology of cerebral palsy unfolds across three interconnected phases. Primary brain injury results from direct damage to brain tissue caused by mechanical, ischemic, or inflammatory factors during pregnancy, childbirth, or the early postnatal period. Secondary brain injury follows, involving gradual damage from oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, apoptosis, and inflammation triggered by the initial insult. Finally, tertiary brain injury involves long-term modifications to brain structure and function due to compromised neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and myelination (Salomon et al., 2024).

More than half of the cases are due to prenatal insults that include infection from the mother to the fetus, maternal stroke, environmental toxins, and problems in brain development. The remaining cases are due to adverse events, including traumatic birth delivery, complications of premature birth, meningitis, and head injury during child abuse.

Neuroimaging studies consistently show that white matter damage of immaturity, particularly periventricular leukomalacia affecting the white matter surrounding the ventricles, is the most common finding in children with cerebral palsy, appearing in over one-third of cases (Bodur et al., 2024). This white matter damage helps explain the motor impairments characteristic of CP, as these regions contain the corticospinal tracts that carry movement commands from brain to muscles.

The three main types of cerebral palsy are spastic, dyskinetic, and ataxic. The mixed type combines these symptoms. About 70-80% of CP patients experience spasticity or limited movement due to permanently contracted muscles. The spastic type of CP is subdivided into hemiplegia (20-30%), diplegia (30-40%), and quadriplegia (10-15%). Mental retardation is present in 30-50% of cases (Abdel-Hamid, 2013).

Biofeedback Treatment for Cerebral Palsy

During assessment, the clinician determines which muscle groups are overactive (spastic) or weak. Positional feedback may be invaluable in correcting abnormal head position. A feedback helmet with position sensors may sound a warning tone when a patient's head deviates from normal posture.

Bolek, Moeller-Mansour, and Sabet (2001) described a "minimax" procedure that utilizes SEMG biofeedback to teach disabled children how to correctly recruit and relax the gluteus medius and gluteus maximus muscles during sitting. Bolek (2006) treated 16 children using customized training of multiple SEMG sites and reported improved motor control.

Clinical Efficacy Rating for Cerebral Palsy

Based on five randomized controlled trials and a crossover design, Moss and Watkins (2023) rated SEMG biofeedback for cerebral palsy as level 4, efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

A comprehensive 2018 systematic review by MacIntosh and colleagues evaluated 57 studies examining biofeedback interventions for people with cerebral palsy using the GRADE framework (MacIntosh et al., 2018). The review found that 79% of studies and 63% of outcome measures showed improvement following biofeedback intervention.

While the overall strength of evidence was rated as "positive, very-low" due to heterogeneous study designs and outcome measures, the authors concluded that biofeedback can improve motor outcomes for people with CP. Importantly, the review noted that most studies provided feedback consistently and concurrently throughout intervention, which contradicts motor learning theory recommendations suggesting that fading feedback over time promotes autonomous learning.

This finding has important implications for clinical practice: practitioners should consider gradually reducing feedback frequency as patients develop new movement patterns to promote long-term skill retention.

Long-Term Outcomes and Prognosis

Although the brain injury causing cerebral palsy is non-progressive by definition, the effects of CP manifest differently across the lifespan, and biofeedback practitioners should understand these long-term trajectories. The majority of individuals with CP have a similar life expectancy to the general population when they can walk independently and feed independently (Blair et al., 2019). However, function changes across the lifespan, with many adults experiencing secondary deterioration in motor abilities.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found that adults with CP have significantly higher prevalence of chronic conditions compared to adults without CP, including pain, fatigue, arthritis, and cardiovascular disease (Ryan et al., 2023).

A Swedish longitudinal study reported that 35% of ambulatory adults with CP experienced decreased walking ability over time, citing knee and balance problems, increased spasticity, and lack of physical training as contributing factors, while notably, 19% reported improved walking ability (Haak et al., 2009).

These findings emphasize the importance of ongoing rehabilitation across the lifespan, not just in childhood, and suggest that biofeedback interventions may be valuable for maintaining function in adults with CP.

Comprehension Questions: Cerebral Palsy

- How does cerebral palsy differ from stroke in terms of the relationship between agonist and antagonist muscles?

- Why might a feedback helmet be more effective than SEMG biofeedback for correcting abnormal head position in a child with CP?

- How does Bolek's "minimax" procedure differ from traditional agonist/antagonist EMG biofeedback?

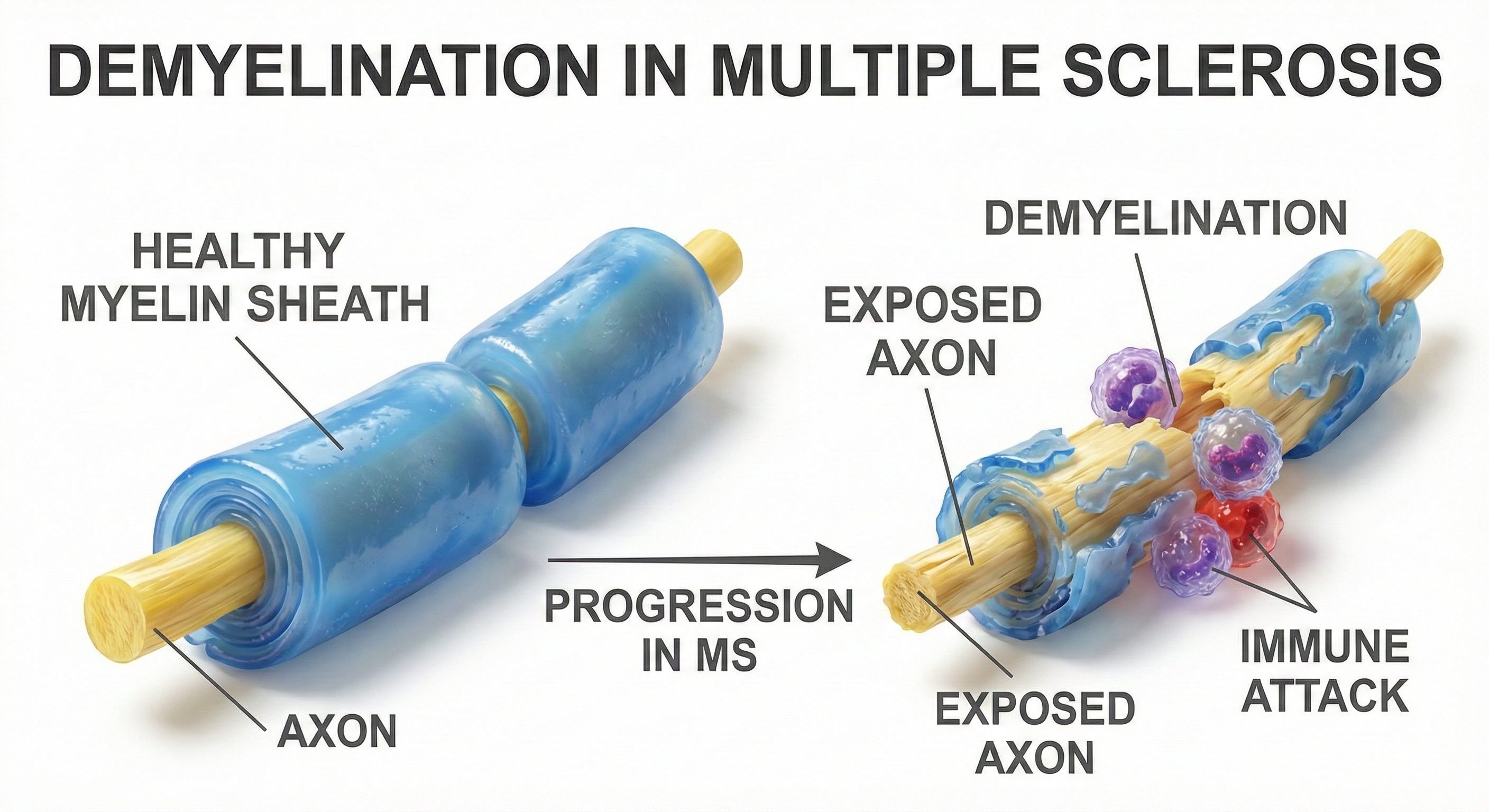

Multiple Sclerosis: When Myelin Fails

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system attacks the myelin sheaths insulating nerve fibers, short-circuiting the brain's wiring. Without intact myelin, neural signals become desynchronized, slowed, or blocked entirely (Breedlove & Watson, 2023). The disease begins when autoreactive T lymphocytes cross the blood-brain barrier and attack myelin proteins. Microglia (resident immune cells) become activated and perpetuate the cycle (Fang et al., 2025). Recent research has identified progression independent of relapse activity (PIRA), neurodegeneration that continues even without acute relapses, which has important implications for rehabilitation approaches.

MS is the most common progressive neurologic disease of young adults. Nearly one million Americans live with MS (Wallin et al., 2019). Women are affected approximately three times more often than men, with diagnosis typically occurring between ages 20 and 50 (Hittle et al., 2023). In relapsing-remitting MS, median time to requiring a cane for walking is approximately 12 years from onset, though this varies enormously (Degenhardt et al., 2009).

Both SEMG-assisted rehabilitation and velocity feedback may correct intention tremors (quivering during coordinated movement). A 2024 study found EMG biofeedback combined with quadriceps strengthening produced significantly greater improvements than exercise alone (Miri et al., 2024). Exergaming (exercise with video gaming) has shown promise for balance, with a 2025 meta-analysis finding technology-based rehabilitation significantly improved balance outcomes (Bargeri et al., 2025). Neurofeedback has shown preliminary evidence for managing MS symptoms including depression, fatigue, and pain (Ayache & Chalah, 2021).

Peripheral Nerve Injury: Damage to the Final Pathway

Peripheral nerves include the lower motor neurons that innervate skeletal muscles. These may be damaged by trauma, edema (swelling), and infection. Clinical signs include flaccid paralysis and muscle atrophy.

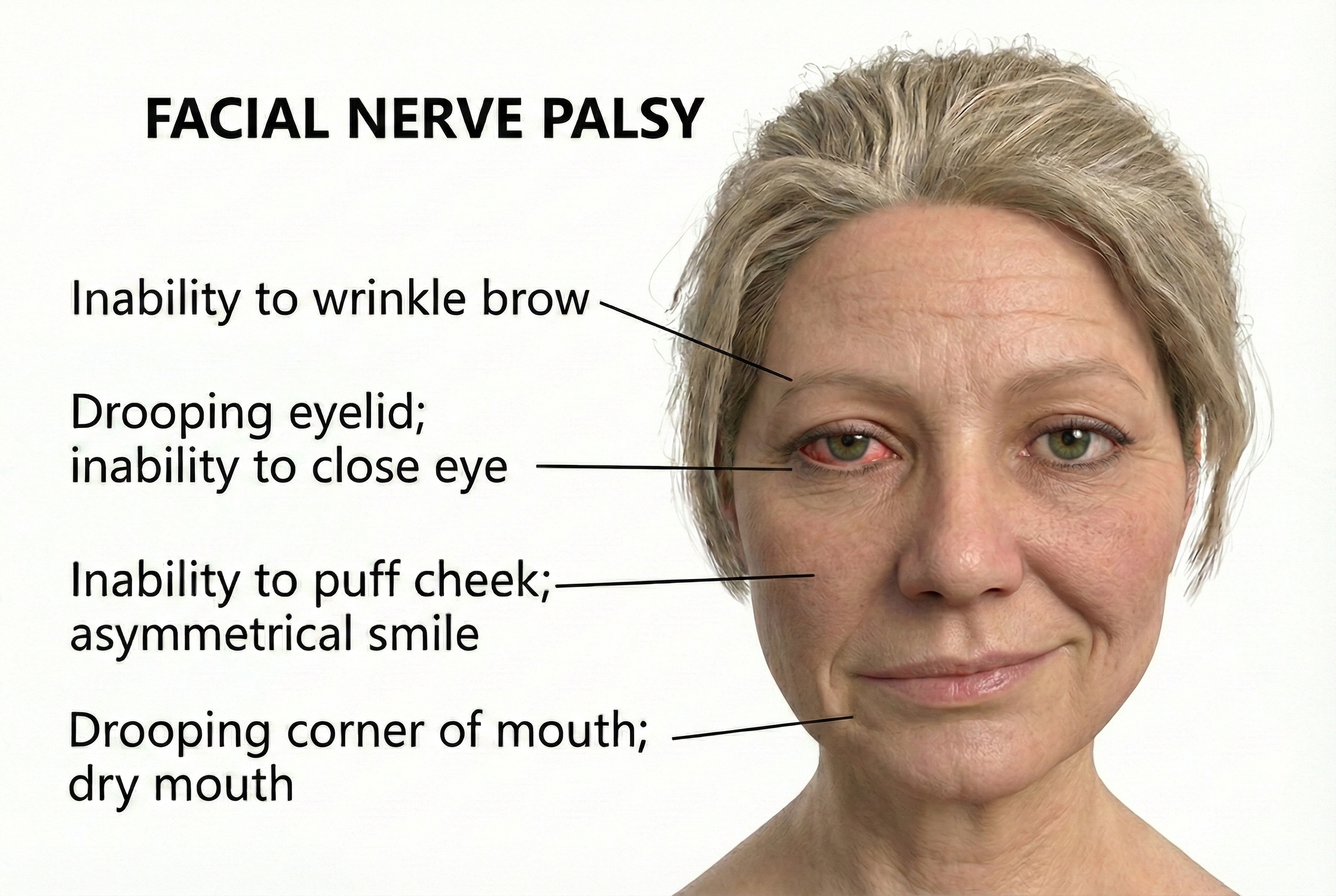

Bell's Palsy

Bell's palsy accounts for 60-75% of all cases of acute one-sided facial paralysis, affecting roughly 40,000 Americans annually (Wei et al., 2025).

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Bell's Palsy

Bell's palsy typically results from reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) lying dormant in the geniculate ganglion (Kim et al., 2025). When stress or illness weakens defenses, the virus triggers inflammation in the narrow bony channel housing the facial nerve, compressing and damaging nerve fibers. Varicella-zoster virus can cause similar but more severe facial paralysis called Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

The good news: 80-90% of patients recover fully within 6 weeks to 3 months. However, approximately 15% will experience permanent moderate to severe weakness. Complications include synkinesis (involuntary facial movement when trying to move a different muscle) and crocodile tears syndrome (tear production when eating). Key indicators of poor prognosis include age over 60, complete paralysis at onset, diabetes, and hypertension (Alqahtani et al., 2024).

Bell's palsy is ideally suited for Wolf's (1985) motor copy procedure. The clinician shows the patient a SEMG tracing from the healthy side and asks them to duplicate it using the affected side. A 2023 meta-analysis found physical therapy, including biofeedback, was associated with a 49% relative reduction in non-recovery rates (Hato et al., 2023). EMG biofeedback has shown particular value in preventing post-paralytic synkinesis (Pourmomeny et al., 2014).

Comprehension Questions: Peripheral Nerve Injury

- Why is Wolf's motor copy procedure particularly well-suited for treating Bell's palsy?

- What complications might develop if Bell's palsy does not fully resolve?

Torticollis: When Neck Muscles Rebel

Torticollis, sometimes called "wry neck," is a form of cervical dystonia that twists the neck into abnormal postures through involuntary muscle contractions. Patients cannot straighten their heads no matter how hard they try.

Idiopathic spasmodic torticollis (IST) is a neurodegenerative disorder that destroys dopaminergic neurons in basal ganglia circuits, disrupting the brain's ability to regulate muscle tone and posture. The result is postural dystonia that patients experience as their head pulling relentlessly to one side.

🎧 Listen to a Mini-Lecture on Torticollis

Understanding the anatomy helps explain the treatment approach. The sternocleidomastoid muscles run from behind your ear to your collarbone and sternum. When one contracts alone, it rotates your head toward the opposite shoulder, so the right sternocleidomastoid turns your head left. The splenius capitis muscles do the opposite: they rotate the head toward the same side. For a patient whose head is stuck rotated to the left, the therapist needs to down-train two muscles: the right sternocleidomastoid (which is pulling the head left) and the left splenius capitis (which is also pulling the head left). This bilateral assessment and treatment distinguishes torticollis rehabilitation from simpler applications of EMG biofeedback.

Comprehension Questions: Torticollis

- If a patient's head is rotated to the right, which muscles might be overactive and need to be down-trained?

- Why is bilateral SEMG assessment important before beginning torticollis treatment?

- How does the progression of training for torticollis parallel the training sequence for stroke rehabilitation?

Cutting-Edge Topics in Neuromuscular Rehabilitation

The field of neuromuscular rehabilitation is evolving rapidly. Technologies that seemed like science fiction a decade ago are entering clinical practice, while established techniques are being combined in novel ways. Here are the frontiers that will shape your future practice.

Brain-Computer Interfaces for Movement Restoration

What if you could bypass damaged motor pathways entirely? Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are making this possible by recording neural signals directly from the motor cortex and translating thought into action. In research laboratories, paralyzed individuals have learned to control robotic arms with their thoughts, manipulating objects, feeding themselves, and even shaking hands with visitors. More dramatically, some systems combine BCIs with implanted electrical stimulators that activate paralyzed muscles directly, essentially creating an artificial nervous system that routes around the injury. The technology is still experimental and expensive, but it demonstrates that the barrier between thought and movement can be rebuilt through engineering.

Virtual Reality and Gamified Rehabilitation

Repetitive exercise is boring. Boring exercise leads to poor compliance. Poor compliance leads to poor outcomes. Virtual reality (VR) breaks this chain by transforming rehabilitation into something patients actually want to do. Imagine a stroke patient who, instead of doing 500 arm lifts, reaches for virtual fruit in a video game orchard, battles aliens that require specific movement patterns to defeat, or practices cooking in a simulated kitchen. The movements are the same; the experience is completely different.

A 2025 Cochrane Systematic Review analyzed 190 randomized controlled trials involving 7,188 participants and found that adding VR therapy to usual care produced significant improvements in motor function (Laver et al., 2025).

A meta-analysis of 24 RCTs examining VR for lower limb recovery found significant improvements in balance, mobility, and gait compared to conventional rehabilitation, with higher treatment frequency (20 or more sessions) producing superior outcomes (JMIR, 2025). For upper limbs, immersive VR showed statistically significant gains on the Fugl-Meyer Assessment (Bracke et al., 2025).

The evidence supports integrating VR-based therapies into standard stroke rehabilitation protocols, and the costs are dropping as consumer VR hardware improves.

Robotic Exoskeletons for Gait Training

Powered exoskeletons look like something from a superhero movie, and they are revolutionizing gait training for spinal cord injury and stroke patients. These wearable robotic frames support the patient's weight while motorized joints move their legs through proper walking patterns. For patients who cannot support themselves or coordinate leg movements, exoskeletons provide an opportunity to practice walking with correct biomechanics from very early in rehabilitation. Built-in sensors track movement quality and provide real-time feedback. Several systems are now FDA-approved and entering clinical use, allowing patients who were told they would never walk again to take steps within weeks of their injuries.

Transcranial Stimulation Combined with Biofeedback

Non-invasive brain stimulation techniques like transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) can temporarily increase or decrease the excitability of specific brain regions. Researchers are now investigating whether "priming" the motor cortex with stimulation before or during biofeedback training might enhance neuroplasticity and accelerate recovery. The idea is to put the brain into a more plastic, learning-ready state before asking it to relearn motor patterns. Early results are promising, though the optimal stimulation parameters and timing remain subjects of active research.

Artificial Intelligence for Personalized Rehabilitation

Machine learning algorithms are bringing personalization to rehabilitation in ways that were previously impossible. AI systems can analyze patterns across thousands of patients to predict which individuals will respond best to which treatments, allowing clinicians to match patients with optimal interventions from the start. During treatment, these systems can automatically adjust biofeedback thresholds, progression schedules, and exercise difficulty in real time based on moment-to-moment patient performance. The algorithm never gets tired, never loses attention, and can detect subtle patterns in EMG signals or movement trajectories that human observers would miss. As these systems accumulate more data, their predictions and recommendations will only improve.

Test Yourself

Click on the ClassMarker logo to take 10-question tests over this unit without an exam password.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Visit the BioSource Software Website

BioSource Software offers Human Physiology, which satisfies BCIA's Human Anatomy and Physiology requirement, and Biofeedback100, which provides extensive multiple-choice testing over BCIA's Biofeedback Blueprint.

Assignment

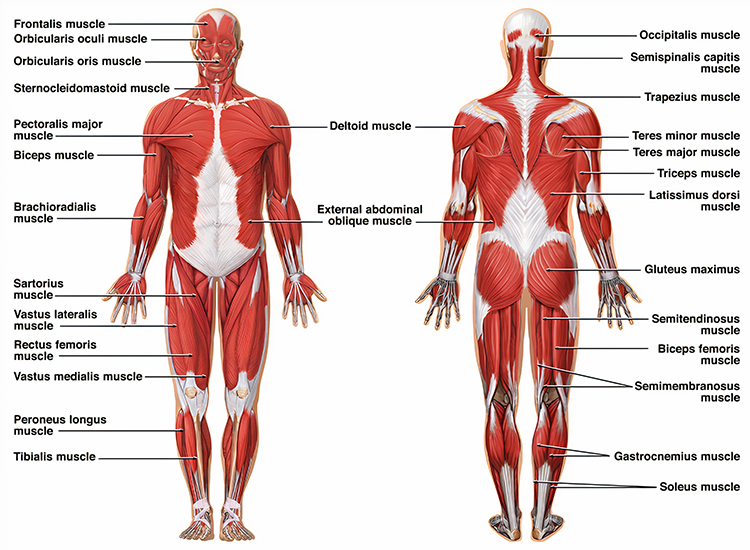

Now that you have completed this module, locate the muscles discussed above in a muscle atlas.

Glossary

accelerometer: a device that measures acceleration, including vibration or gravity, used to measure symptoms like hand tremor.

acute: referring to a recent injury or condition, as opposed to chronic.

agonist: the muscle that performs the main action at a joint.

agonist spasticity: excessive muscle tone and tendon reflexes in the primary muscle at a joint following cerebral ischemia.

antagonist: the muscle that opposes the agonist at a joint.

antagonist paresis: weakness in the muscle that opposes the agonist at a joint following cerebral ischemia.

apraxia: the inability to organize movements into a productive sequence, initiate, and perform voluntary skilled movements in the absence of paralysis.

arteriosclerosis: the thickening of artery walls and reduction of elasticity.

ataxia: the impairment of the direction, amplitude, and speed of muscular movement, often due to cerebellar damage.

athetoid movements: slow, continuous twisting movements observed in a subtype of cerebral palsy patients.

Bell's palsy: unilateral facial paralysis caused by disease or trauma to the facial (VII) nerve.

central pattern generators: spinal circuits that direct the recruitment of motor units to perform repetitive movements.

cerebral hemorrhage: a subtype of intracranial hemorrhage caused by a cerebral blood vessel's rupture.

cerebral ischemia: the localized reduction of blood flow to all or part of the brain below the level required to meet metabolic demands.

cerebral palsy (CP): a family of nonprogressive motor disorders involving irreversible motor disability due to damage before or soon after birth.

cerebrovascular accident (CVA): stroke; destruction of brain tissue due to cerebral hemorrhage or cerebral ischemia.

Concurrent Assessment of Muscle Activity (CAMA): Wolf's rehabilitation protocol using biofeedback to suggest changes in patient posture, position, or movement.

Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT): Taub's stroke protocol that restricts the movement of the unaffected limb to force the patient to rely on the affected one.

corticospinal tract: the pyramidal motor pathway responsible for discrete control of fingers, hands, arms, trunk, and upper legs.

crocodile tears syndrome: profuse tear production when tasting strongly-flavored food, a complication of Bell palsy.

diplegia: paralysis of symmetrical parts of the body; in cerebral palsy, paralysis affects both legs more often than both arms.

distal: the point most distant from the attached end of a limb.

dorsiflexor: the muscle that points the toes toward the shin through flexion at the ankle joint.

electrogoniometer: a device that translates a change in joint angle into a change in electrical resistance.

embolism: the blockage of a blood vessel by an embolus that travels through the blood.

excitotoxicity: neuronal damage caused by excessive release of glutamate and subsequent overactivation of excitatory receptors, leading to calcium overload and cell death.

EMG biofeedback: the display of a client's muscle action potentials back to the individual.

extensor spasticity: excessive extensor muscle activity that starts about six months following spinal cord injury.

extrapyramidal motor system: the motor pathway that controls bilateral, gross movements and postural changes.

exergaming: exercise combined with video gaming technology that uses motion sensors and interactive displays to make physical rehabilitation engaging and motivating.

feedback cane: a rehabilitation device that uses a strain gauge to measure pressure applied to the cane during walking.

feedback helmet: a positional biofeedback device that sounds a warning tone when a patient's head deviates from normal posture.

ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death characterized by accumulation of lipid peroxides and disruption of cell membranes, implicated in stroke and neurodegenerative diseases.

flaccid paralysis: the weakness or loss of muscle tone due to injury or disease affecting lower motor neurons.

Flexeril (cyclobenzaprine): a centrally-acting muscle relaxant.

flexor spasticity: excessive flexor muscle activity that starts 3-6 months after spinal cord injury.

foot drop: the failure to dorsiflex and evert the foot due to weakness or paralysis of dorsiflexor and evertor muscles combined with spasticity in plantar flexors.

force feedback: the display of force conducted through the body or hand during work or exercise.

force transducer: a sensor that converts the force conducted through the body or hand into electrical signals.

functional time-domain score (FTDS): a QSEMG metric that assesses the combined performance of monitored muscles.

gastrocnemius muscle: the muscle that plantar flexes the foot and flexes the knee joint.

geniculate ganglion: a cluster of nerve cell bodies within the temporal bone that contains sensory neurons of the facial nerve and can harbor latent herpes viruses that reactivate to cause Bell's palsy.

gyroscope: a device that measures rotational motion, used to measure variation in wrist movement and hand tremor.

hemiplegia: the paralysis of the upper extremity, trunk, and lower extremity muscles on one side.

hyperreflexia: extreme reactivity and exaggeration of reflexes that can lead to spastic paralysis.

hypertrophy: excessive muscle enlargement.

hypotonic: decreased muscle tone causing muscle weakness and joint instability.

idiopathic spasmodic torticollis (IST): a neurodegenerative disease that destroys dopaminergic neurons in basal ganglia circuits, producing postural dystonia.

intention tremor: quivering that appears or worsens when a patient attempts coordinated movement.

joint angle: the angle between the longitudinal axes of two adjoining body parts.

levator scapulae muscle: a muscle in the posterior neck that elevates the scapula and produces downward rotation.

limb load monitor (LLM): a force feedback device used to train hemiplegic patients to balance their weight distribution.

lower motor neurons: alpha and gamma motoneurons that connect the brainstem and spinal cord to skeletal muscle fibers.

microglia: the resident immune cells of the central nervous system that become activated during injury or disease and can contribute to neuroinflammation.

modified constraint-induced movement therapy (mCIMT): an adapted version of CIMT with reduced constraint time and practice intensity, making it more feasible for clinical settings while maintaining therapeutic benefits.

monoplegia: rare paralysis that involves an arm or leg.

motor copy procedure: Wolf's rehabilitation protocol in which a patient matches an EMG tracing from an unaffected muscle using the corresponding affected muscle.

multiple sclerosis (MS): the progressive destruction of myelin sheaths that insulate axons, short-circuiting conduction.

NMDA receptor: an ionotropic glutamate receptor whose overactivity may mediate ischemic damage to oligodendrocytes.

oligodendrocytes: glial cells that myelinate axons in the CNS.

orbicularis oculi: the facial muscle that closes the eyelids and wrinkles the forehead.

paraparetic: having weakness in the lower limbs.

paralysis: the loss or impairment of muscle function due to a muscular or nervous system lesion.

paresis: muscle weakness or partial paralysis.

percutaneous electrode: an electrode inserted through the skin to evaluate the viability of motor units.

peripheral nerve: the nerves of the autonomic, enteric, or somatic nervous system, including the lower motor neurons that innervate skeletal muscles.

periventricular leukomalacia: damage to the white matter surrounding the ventricles, most commonly seen in premature infants and frequently associated with cerebral palsy.

plantar flexors: the muscles that point the toes downward through extension at the ankle joint.

positional feedback: the display of information about the position of the body or a body part in three-dimensional space.

post-paralytic synkinesis: involuntary facial movements that occur during attempted voluntary movements, resulting from aberrant nerve regeneration following facial nerve injury.

prefrontal cortex: the most anterior division of the frontal lobe, concerned with attention, planning, and executive functions.

premotor cortex: the motor cortex region that adjusts existing motor programs under the guidance of external sensory information.

primary brain injury: direct damage to brain tissue caused by mechanical, ischemic, or inflammatory factors during the initial insult, as seen in cerebral palsy pathophysiology.

primary injury: in spinal cord injury, the immediate mechanical damage from trauma that directly kills neurons and glia.

primary motor cortex: the cortical region that executes motor programs through descending tracts.

progression independent of relapse activity (PIRA): disease progression in multiple sclerosis that occurs without clinical relapses, driven by neurodegeneration rather than acute inflammation.

proprioception: the perception of balance, joint angle, movement, muscle length, and position.

proximal: the point closest to the attached end of a limb.

pyramidal motor system: the motor pathway starting in the primary motor cortex and projecting to spinal cord motor neurons.

quadriparetic: having weakness in all four limbs.

quadriplegia: paralysis of all four limbs and the trunk.

quantitative surface electromyography (QSEMG): Bolek's strategy for teaching functional movement patterns by providing feedback from multiple muscle sites.

real-time ultrasound (RTUS) imaging: a diagnostic technique that uses high-frequency sound waves to produce continuous, live video images of internal body structures as they move. In biofeedback applications, RTUS allows clinicians and patients to visualize muscle contractions and movements instantaneously, providing immediate visual feedback during rehabilitation exercises—particularly useful for training deep stabilizing muscles like the transversus abdominis or pelvic floor muscles that are difficult to observe or palpate externally.

shaping: an operant procedure where therapists reinforce successive approximations of the target behavior.

secondary brain injury: gradual and progressive damage to brain tissue following primary injury, caused by oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, apoptosis, and inflammation.

secondary deterioration: progressive decline in motor function that occurs in adults with cerebral palsy over time, despite the non-progressive nature of the original brain injury, often due to musculoskeletal changes, pain, and reduced physical activity.

secondary injury: in spinal cord injury, the cascade of destructive processes including inflammation, oxidative stress, and excitotoxicity that develops over hours to weeks following the initial trauma.

spastic paralysis: paralysis with increased muscle tone and hyperreflexia.

spasticity: elevated muscle tone with resistance to stretching that interferes with normal smooth movement.

spontaneous neurological recovery: the natural improvement in motor and sensory function that occurs in the weeks to months following stroke or other brain injury, driven by resolution of inflammation, neural reorganization, and unmasking of latent pathways.

splenius capitis muscles: cervical muscles that extend the head when acting together and rotate the head to the same side when acting individually.

sternocleidomastoid muscles: neck muscles that flex the cervical vertebral column when acting together and rotate the head to the opposite side when acting individually.

stroke: destruction of brain tissue due to cerebral hemorrhage or cerebral ischemia.

stroke prevalence: the proportion of a population that has experienced a stroke at a given point in time, typically expressed as cases per 100,000 persons.

synkinesis: involuntary contraction when another muscle is contracted, a complication of Bell palsy.

thrombosis: the blockage of a blood vessel by material (blood clots, fat, etc.) that forms at that location.

torticollis: a form of cervical dystonia characterized by a twisted neck and involuntary neck muscle contraction.

transient flaccid paralysis: a complete loss of muscle tone that occurs immediately after pyramidal tract injury.

trapezius: a triangular muscle sheet covering the posterior neck and superior trunk that elevates the scapula and helps extend the head.

tertiary brain injury: long-term modifications to brain structure and function resulting from compromised neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and myelination following primary and secondary injury.

upper motor neurons: the motor neurons that project from the motor region of the cerebral cortex or brainstem to synapse with spinal interneurons or lower motor neurons.

varicella-zoster virus: the herpes virus that causes chickenpox and shingles; when it reactivates in the facial nerve, it causes Ramsay Hunt syndrome, a severe form of facial paralysis.

velocity feedback: the display of the variation in movement of a body part.

white matter damage of immaturity: injury to the developing white matter in premature infants, the most common brain abnormality found in children with cerebral palsy.

References

Abdel-Hamid, H. Z. (2013). Cerebral palsy. eMedicine. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1179555-overview

Alqahtani, S. Y., Almalki, Z. A., Alnafie, J. A., Alnemari, F. S., AlGhamdi, T. M., AlGhamdi, D. A., Albogami, L. O., & Ibrahim, M. (2024). Recurrent Bell's palsy: A comprehensive analysis of associated factors and outcomes. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/01455613241301230

Ayache, S. S., & Chalah, M. A. (2021). Neurofeedback therapy for the management of multiple sclerosis symptoms: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 15, 702322. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2021.702322

Barclay-Goddard, R. E., Stevenson, T. J., Poluha, W., Moffatt, M., & Taback, S. P. (2004). Force platform feedback for standing balance training after stroke (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004129.pub2

Bargeri, S., Scalea, S., Agosta, F., & the MS Rehabilitation Research Group. (2025). Technology-based physical rehabilitation for balance in patients with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 106(7), 1064-1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2025.01.003

Bloom, R., Przekop, A., & Sanger, T. D. (2010). Prolonged electromyogram biofeedback improves upper extremity function in children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Child Neurology, 25(12), 1480-1484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073810369704

Blair, E., Langdon, K., McIntyre, S., Lawrence, D., & Watson, L. (2019). Survival and mortality in cerebral palsy: Observations to the sixth decade from a data linkage study of a total population register and National Death Index. BMC Neurology, 19, 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1343-1

Burns, A. S., & Ditunno, J. F. (2001). Establishing prognosis and maximizing functional outcomes after spinal cord injury: A review of current and future directions in rehabilitation management. Spine, 26(24S), S137-S145. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200112151-00023

Bolek, J. E. (2006). Use of multiple-site performance-contingent SEMG reward programming in pediatric rehabilitation: A retrospective review. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 31(3), 263-272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10484-006-9017-3

Bolek, J. E. (2012). Quantitative surface electromyography: Applications in neuromotor rehabilitation. Biofeedback, 40(2), 47-56. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-40.2.6

Bolek, J. E. (2020). QSEMG: Quantitative surface electromyography: Origins and applications in physical rehabilitation. Biofeedback, 48(2), 26-31. https://doi.org/10.5298/1081-5937-48.2.01