Musculoskeletal Applications

What You Will Learn

This chapter explores how biofeedback helps people regain control over muscles and bodily functions that still have intact nerve connections but need retraining. You will discover why musculoskeletal disorders differ fundamentally from neuromuscular conditions: your client's brain can still sense where their body is in space, but the muscles need help learning new patterns. From the delicate muscles around the eyes in blepharospasm to the powerful quadriceps following knee surgery, you will learn specific electrode placements, training protocols, and the evidence supporting each intervention.

You will understand how pelvic floor biofeedback has achieved the highest efficacy ratings for conditions like urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, and why combining EMG feedback with electrical stimulation often produces superior outcomes.

Close your eyes and touch your nose. How did you know where to find it? That ability—knowing exactly where your body parts are without looking—is called proprioception, and it's the key difference between musculoskeletal and neuromuscular disorders. Your musculoskeletal clients retain this remarkable sense of body position and movement. Their nervous system can still tell them where their limbs are in space, how their muscles are contracting, and whether their joints are bent or straight.

This intact feedback loop makes biofeedback training particularly powerful: clients can integrate the external feedback you provide with their internal sensory information. Think of it as giving someone directions when they already have a working GPS—the additional guidance helps them navigate more precisely.

Musculoskeletal biofeedback applications span an impressive range: blepharospasm (uncontrolled eyelid spasms), erectile dysfunction, fecal elimination disorders, functional constipation, urinary incontinence, meniscectomy rehabilitation, and muscle-tendon transfers.

At first glance, these conditions seem wildly different—what could eyelid twitches possibly have in common with knee surgery recovery? The unifying thread is that they all involve muscles that need to learn new patterns of activation or relaxation. The muscles still work, the nerves still connect them to the brain, but somewhere along the way, the coordination got scrambled. Biofeedback essentially becomes a translator, helping clients understand what their muscles are doing so they can teach them to behave differently.

Here's encouraging news for your future practice: the evidence base for these treatments has grown substantially stronger in recent years. Since the publication of Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (3rd ed.), several randomized controlled trials have strengthened the evidence considerably.

Erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence for both men and women now warrant a level-5 rating of efficacious and specific—the highest designation available, meaning biofeedback works better than credible placebo treatments. Pediatric urinary incontinence is a candidate for a level-4 rating of efficacious. These aren't just modest improvements; they represent biofeedback performing at the gold standard of medical evidence.

Consider a meniscectomy—the surgical removal of damaged knee cartilage—as a straightforward example of musculoskeletal intervention. Following surgery, patients often show generalized muscular weakness, but here's the surprising part: the weakness isn't because the muscle tissue is damaged. Instead, it's because the brain has turned down the volume on muscle activation to protect the injured joint.

A physical therapist might use electromyographic biofeedback to increase motor unit recruitment—essentially teaching the muscle to activate more of its available motor units and fire them faster. Think of motor units as employees at a company: after knee surgery, the brain puts many workers on involuntary leave. Biofeedback helps call them back to work, restoring the muscle's full workforce capacity.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses General treatment considerations (IV-D) and Target muscles, typical electrode placements, and SEMG treatment protocols for specific neuromuscular conditions (IV-E).

This unit covers Blepharospasm, Erectile Dysfunction, Fecal Elimination Disorders, Functional Constipation, Urinary Incontinence, Meniscectomy, and Muscle-Tendon Transfer.

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter Lecture

Evidence-Based Practice (4th ed.)

We have updated the efficacy ratings for clinical applications covered in AAPB's Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). This comprehensive resource provides the most current evidence for biofeedback interventions across all clinical domains.

When Eyelids Refuse to Cooperate: Understanding Blepharospasm

Imagine waking up one morning and finding that your eyelids have developed a mind of their own. They blink uncontrollably, squeeze shut without warning, and sometimes refuse to open at all—trapping you behind your own closed eyes. This is the reality for people living with blepharospasm, a focal dystonia (a movement disorder affecting one specific body region) involving involuntary spasms of both eyelids.

The condition typically strikes elderly patients and is characterized by bilateral blinking that ranges from merely annoying to completely disabling. These spasms may be isolated or may affect associated facial muscles (Gibbons & Engstrom, 2018). For someone with severe blepharospasm, basic activities we take for granted—reading, watching TV, walking safely, driving—become impossible.

🎧 Listen to the Mini-Lecture on Blepharospasm

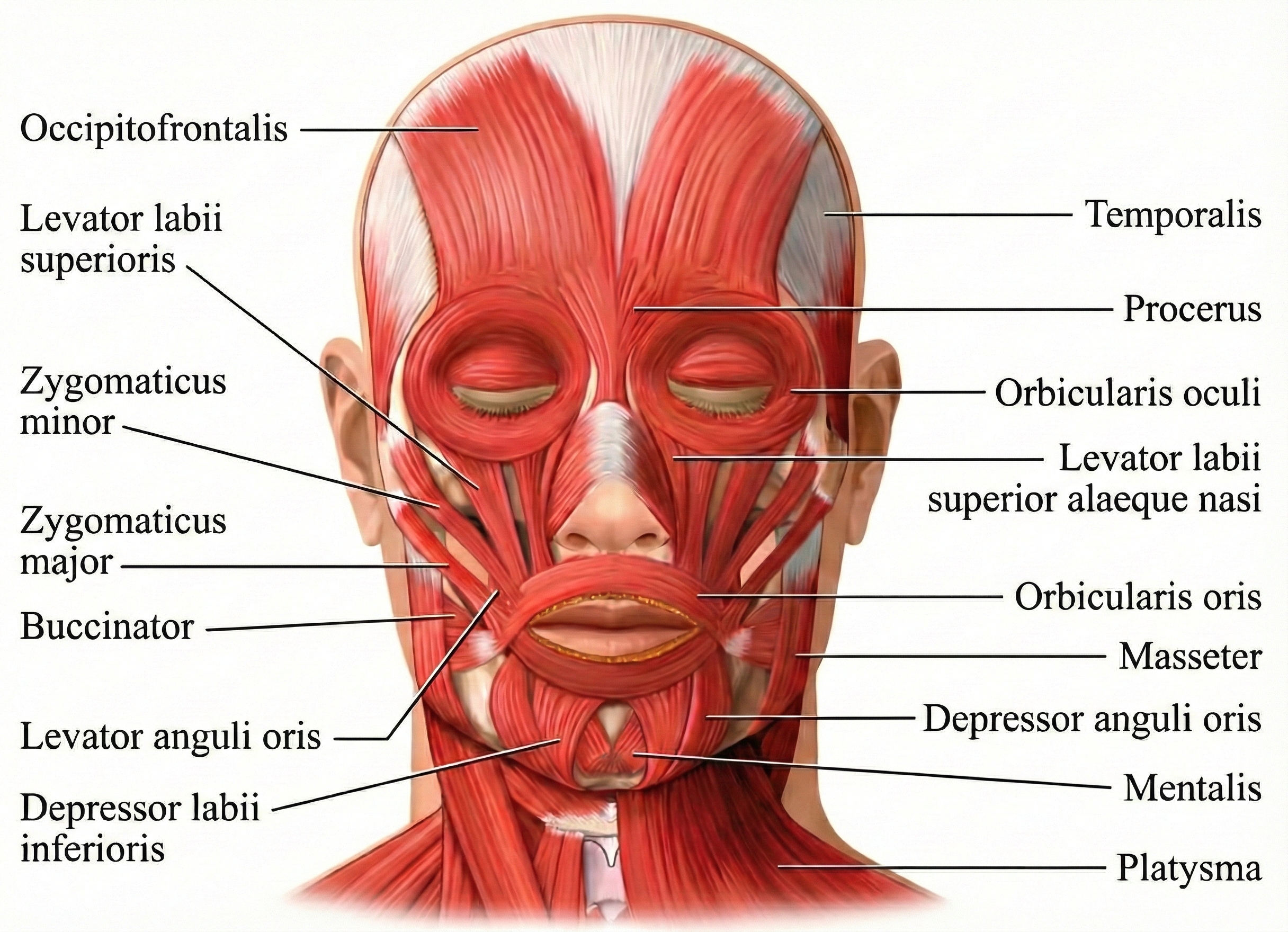

The muscles responsible for this distressing condition are the orbicularis oculi—the circular muscles that wrap around each eye like rings and allow you to squeeze your eyes shut. But the problem doesn't originate in the muscles themselves. Research now recognizes blepharospasm as a network disorder rather than a defect at a single brain location.

The basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuit—a neural network that normally acts like a gatekeeper for movement, deciding which actions to allow and which to suppress—appears dysfunctional in these patients. Neuroimaging studies show abnormalities across multiple brain regions including the basal ganglia, cortex, and cerebellum (Defazio et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2024).

Neurotransmitter imbalances—particularly reduced dopamine signaling—may impair the brain's ability to inhibit unnecessary blink reflexes. It's as if the brain's spam filter is broken, allowing excessive "blink now!" signals to get through.

Symptoms range in severity from mildly increased blinking and periodic eyelid spasm to ocular pain, facial spasms, and disabling interference with vision. In severe cases, patients experience what amounts to functional blindness: they cannot drive, read, watch television, or walk safely—not because their eyes don't work, but because their eyelids won't stay open.

Who Develops Blepharospasm?

There are an estimated 50,000 cases of blepharospasm in the United States, with 2,000 new cases diagnosed annually, representing a prevalence of 5 in 100,000. This disorder affects women more often than men at a ratio of 1.8 to 1. The average age at first diagnosis is 56, and two-thirds of patients are 60 or older when they first develop symptoms (Graham, 2014).

Training the Orbicularis Oculi to Relax

SEMG biofeedback offers a way to help clients learn to reduce spasticity in the orbicularis oculi muscles. Because these muscles are small and the recording area is limited, clinicians use miniature (0.5 cm) surface electrodes placed directly over these muscles—standard-sized electrodes would be far too large and would pick up signals from neighboring muscles. The training goal is elegantly simple: teach clients to recognize and reduce the elevated SEMG levels associated with muscle hyperactivity.

By watching the feedback display, clients learn to notice the subtle feeling of tension building before a spasm erupts. Many clients continue home practice using a mirror for feedback, learning to detect the early physical signs of a building spasm—a slight tightening, a flicker of movement—and consciously relaxing before the full contraction develops. This early warning system gives them a chance to interrupt the spasm cycle before it starts.

The orbicularis oculi muscles, shown in the anatomical illustration below, are located around the eyes.

Below is a BioGraph Infiniti display that provides SEMG biofeedback to help clients learn to relax.

What Does the Evidence Show?

Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.) did not evaluate this application, meaning that while clinical reports suggest benefit, insufficient controlled research exists to assign an efficacy rating.

Consider Margaret, a 62-year-old retired teacher who developed blepharospasm three years ago. Her symptoms began with occasional excessive blinking but progressed to the point where she could no longer read to her grandchildren or drive to the grocery store. Botulinum toxin injections provided temporary relief but caused drooping eyelids as a side effect. After 12 sessions of SEMG biofeedback targeting her orbicularis oculi, Margaret learned to detect the subtle tension buildup that preceded her spasms. She now practices brief relaxation exercises several times daily and reports that her symptoms have decreased by approximately 60%, allowing her to resume most of her normal activities.

Blepharospasm involves involuntary spasms of the orbicularis oculi muscles surrounding the eyes, caused by dysfunction in brain circuits that normally regulate blinking. This condition predominantly affects women over 60 and can cause functional blindness in severe cases—not because the eyes don't work, but because the eyelids won't stay open.

SEMG biofeedback using miniature electrodes teaches clients to recognize elevated muscle tension and relax before full spasms develop. The treatment essentially creates an early warning system, allowing clients to interrupt the spasm cycle. While clinical reports suggest benefit, formal efficacy ratings await controlled research.

Check Your Understanding

- Why are miniature electrodes necessary when treating blepharospasm with SEMG biofeedback?

- What makes blepharospasm particularly devastating for daily functioning, and how does biofeedback address the underlying problem?

- How might home practice with a mirror complement clinical biofeedback sessions for blepharospasm?

Restoring Sexual Function: Biofeedback for Erectile Dysfunction

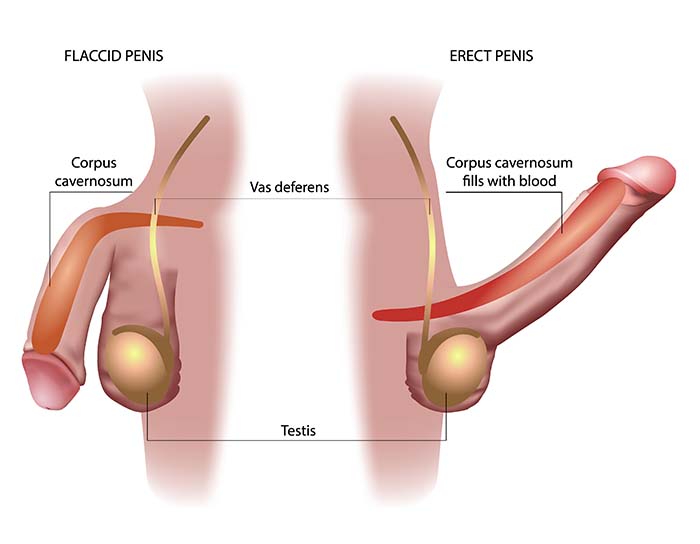

Erectile dysfunction (ED) refers to the inability to sufficiently achieve or sustain a penile erection for sexual intercourse (Shamloul & Ghanem, 2013). While often joked about in popular culture, ED represents a significant medical condition that can devastate quality of life and relationships. The causes span multiple domains: neurogenic (nerve damage), psychogenic (psychological factors), endocrinologic (hormone imbalances), or iatrogenic (resulting from medical treatment such as surgery or medications).

The 2021 National Survey of Sexual Wellbeing confirmed that ED prevalence ranges from approximately 5% in men under 40 to over 70% in men 70 and older, with the overall prevalence in adult men remaining substantial at approximately 18-20% (Mark et al., 2024; Selvin et al., 2007). A recent global epidemiological update found prevalence between 13% in southern Europe and 21% in English-speaking countries across all age groups (Nguyen et al., 2017).

The prevalence rises substantially among those with diabetes, hypertension, and major depression (Seftel et al., 2004), and here's a trend worth noting: ED now increasingly affects younger men, with patients aged 20-40 accounting for 30% of all ED cases (Goldstein et al., 2020).

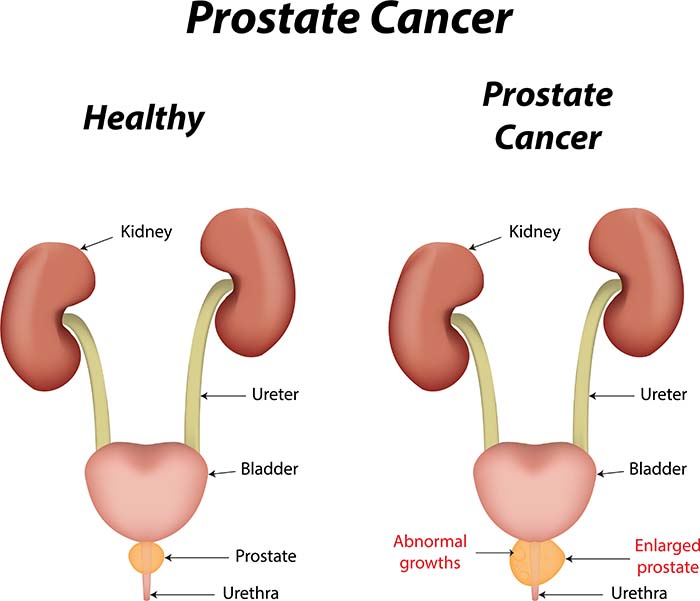

ED can also result from surgery, even when surgeons use advanced techniques designed to preserve the nerves regulating erections (Burnett et al., 2007). Radical prostatectomy, a common surgical procedure for localized prostate cancer, causes ED in 26-100% of patients (Burnett et al., 2007; Walsh et al., 1987) due to neurovascular bundle injury and other mechanisms (Dubbelman et al., 2006).

Understanding the Scope of the Problem

The National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS) reported that 10.4% of men aged 18-59 experienced ED during the previous year (Benet & Melman, 1995). For men undergoing prostate cancer treatment, the statistics are far more sobering: radical prostatectomy causes ED in more than one-quarter of patients, and rates as high as 100% have been reported in some studies.

The etiology of non-iatrogenic ED (not due to medical treatment) involves complex neurovascular mechanisms. Penile erection depends critically on nitric oxide (NO), a tiny gaseous molecule released from nerve terminals and the endothelium (the inner lining of blood vessels) in the corpora cavernosa (the spongy erectile tissue).

Here's how the cascade works: NO activates an enzyme that increases cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which in turn relaxes smooth muscle and allows blood to engorge the erectile tissue (Burnett, 2022; Lue, 2000). This is essentially hydraulics—the tissue fills with blood because the blood vessels relax and open up. Risk factors including diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and aging impair this process through endothelial dysfunction—the blood vessel lining gradually loses its ability to produce adequate NO, like a factory that can no longer keep up with demand (Maiorino et al., 2024).

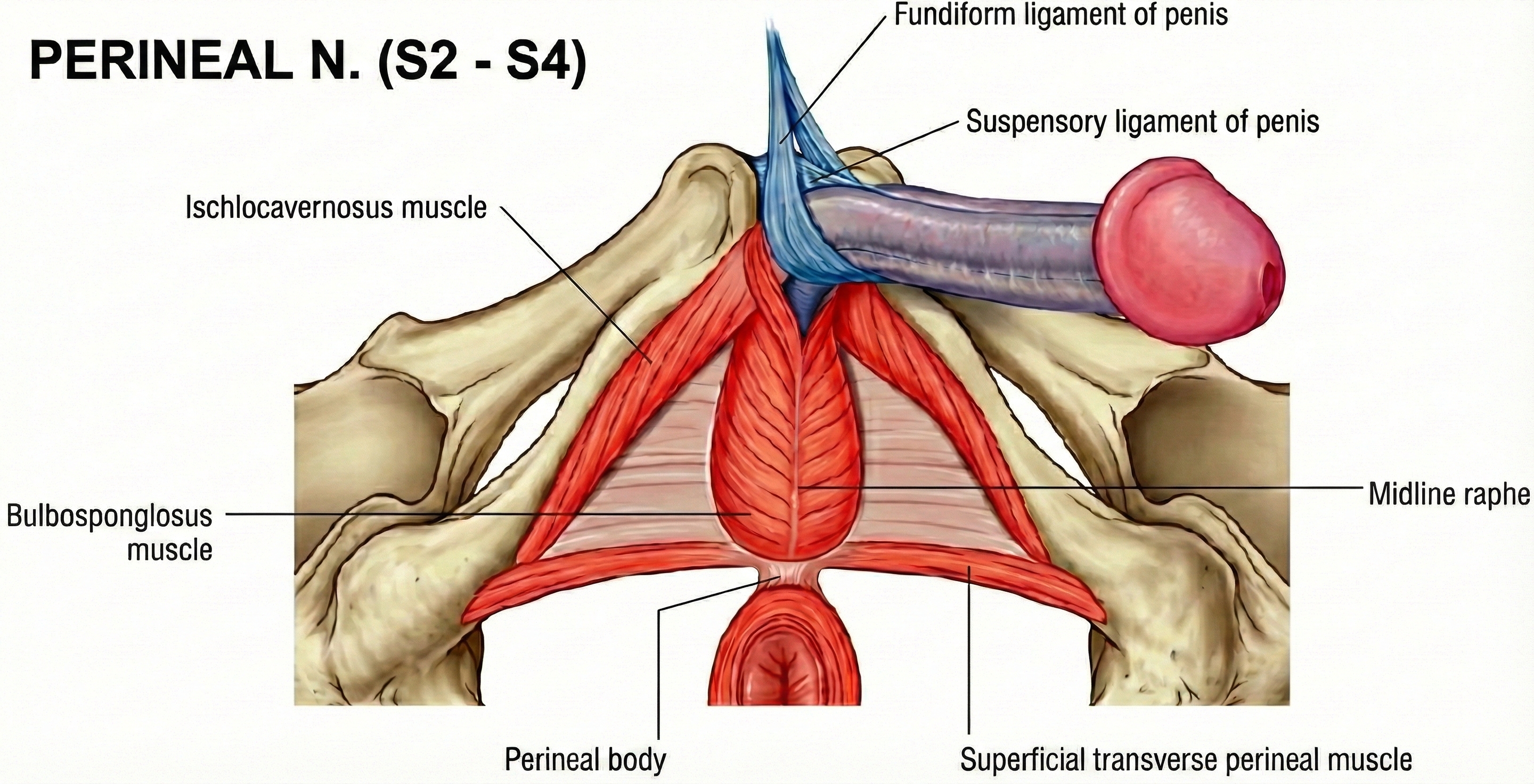

Recent research confirms that oxidative stress—an imbalance between harmful reactive molecules and the body's ability to neutralize them—disrupts this NO signaling pathway by generating reactive oxygen species that directly inactivate NO before it can do its job (Hamed et al., 2024). It's like trying to fill a bathtub while someone keeps pulling the drain plug. In men, the ischiocavernosus muscle (ICM) and bulbospongiosus pelvic-floor muscles contribute to the final phase of erection—contraction of the ICM produces rigidity by compressing the base of the engorged penis, essentially trapping the blood inside and creating sufficient pressure for penetration.

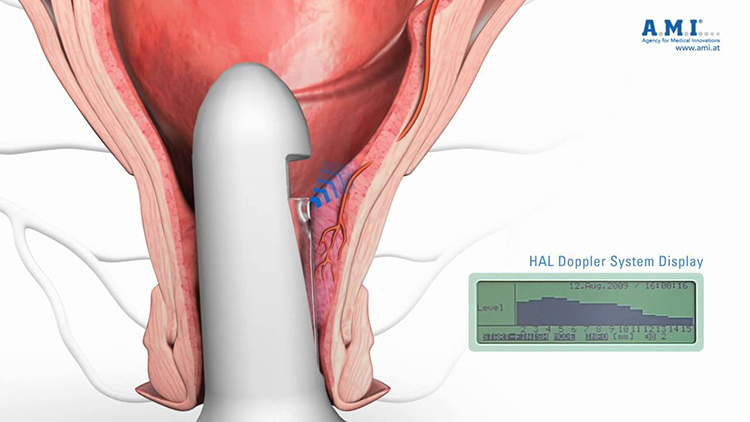

How Pelvic Floor Biofeedback Helps

An impressive and growing body of research, including several randomized controlled trials (RCTs), has shown encouraging results for pelvic-floor biofeedback training (PFBT)—a multimodal approach that combines pelvic floor muscle exercises, EMG biofeedback, and often electrical stimulation.

Why does strengthening the pelvic floor help with erection? Remember those ischiocavernosus muscles that trap blood and create rigidity? They're pelvic floor muscles. Strengthening them enhances the mechanical component of erection, while the biofeedback component ensures patients are actually contracting the right muscles rather than just tensing their abdominals or buttocks.

Van Kampen and colleagues (2003) evaluated the effectiveness of pelvic-floor exercises, electromyographic (EMG) biofeedback of pelvic floor muscle activity, and electrical stimulation of perineal muscles for ED. Fifty-two patients received 4 months of weekly PFBT training sessions. After training, 47% achieved a normal erection, 24% improved, and 12% did not change.

Dorey and colleagues (2004, 2005) reported a randomized controlled trial for 55 men diagnosed with ED. The researchers randomly assigned 28 patients to a PFBT intervention group and 27 patients to a control group. After 3 months, the intervention group achieved better erectile function than the control group.

Prota and colleagues (2012) reported an RCT of PFBT for ED following radical prostatectomy. Twelve months following radical prostatectomy, more experimental subjects (47%) than control subjects (12.5%) recovered potency.

The Highest Efficacy Rating

Meehan and Shaffer (2023) rated EMG biofeedback as efficacious and specific for treating ED. Two independent RCTs demonstrated that interventions combining pelvic-floor muscle exercises, EMG biofeedback, and electrical stimulation could restore or improve erectile function.

Consider James, a 58-year-old accountant who underwent radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer. Despite nerve-sparing surgical techniques, he experienced complete ED postoperatively. After 12 weeks of pelvic floor biofeedback training combining EMG feedback, electrical stimulation, and home exercises, James reported gradual return of morning erections. By six months post-training, he had recovered sufficient erectile function for satisfactory sexual intercourse without medication.

Erectile dysfunction affects millions of men and frequently follows prostate surgery. Pelvic-floor biofeedback training combining EMG feedback, electrical stimulation, and muscle exercises has achieved the highest efficacy rating for this condition. Two independent RCTs demonstrated superiority over control treatments, with recovery rates nearly four times higher in treatment groups following radical prostatectomy.

Check Your Understanding

- What three components are typically combined in successful pelvic-floor biofeedback training for erectile dysfunction?

- Why does radical prostatectomy frequently cause erectile dysfunction?

- What evidence supports the "efficacious and specific" rating for ED treatment?

- How do the ischiocavernosus and bulbospongiosus muscles contribute to erectile function?

Restoring Bowel Control: Fecal Elimination Disorders

Fecal incontinence is the involuntary release of feces or gas due to loss of anal sphincter control. Few conditions cause more embarrassment and social isolation. People with fecal incontinence often withdraw from social activities, avoid travel, and experience profound shame that prevents them from seeking help—sometimes for years. Understanding this emotional context is essential for clinicians: by the time clients reach your office, they've likely already suffered in silence and may need reassurance that this is a treatable medical condition, not a character flaw.

🎧 Listen to the Mini-Lecture on Fecal Elimination Disorders

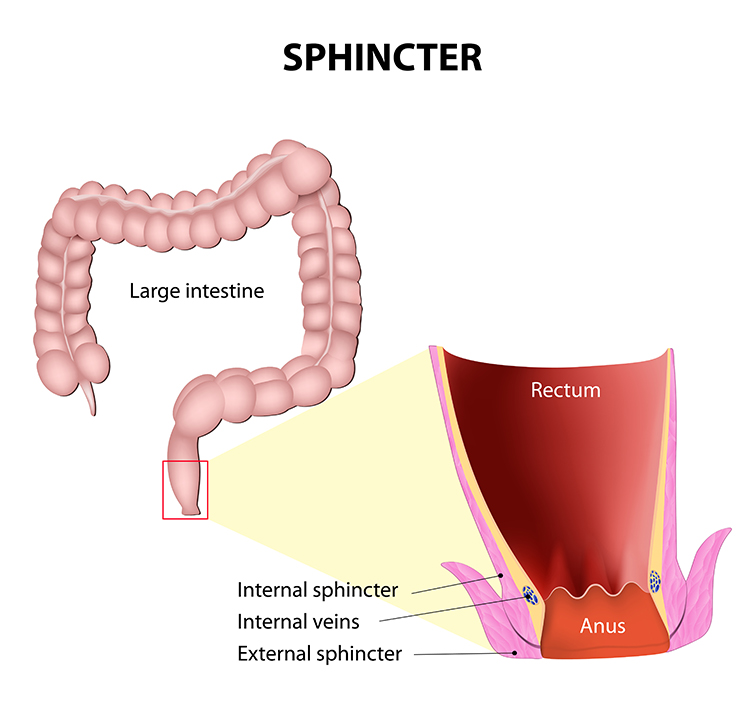

Fecal incontinence rarely results from a single defect—instead, it typically involves the interplay of multiple pathogenic mechanisms, making it a puzzle that requires careful assessment (Rao, 2004). The internal anal sphincter (IAS) provides about 70-85% of resting anal pressure—it's the muscle that keeps things closed while you sleep or go about your day without thinking about it. The IAS is reinforced during voluntary squeeze by the external anal sphincter (EAS), which you consciously contract when you "hold it." Disruption of either sphincter, or damage to their neural control, can produce incontinence.

The pudendal nerve plays a critical role, innervating the EAS and coordinating the reflex pathways essential for continence. Pudendal neuropathy—nerve damage from childbirth trauma, chronic straining, or pelvic organ prolapse—can diminish both muscle strength and the ability to sense rectal fullness (Knowles et al., 2022; Rao, 2004). When rectal sensation is impaired, stool may accumulate excessively before triggering the urge to defecate, sometimes leading to overflow incontinence—the rectum simply becomes too full to hold everything.

Obstetric trauma remains the most common cause of sphincter disruption in women, potentially affecting the EAS, IAS, and pudendal nerves either singly or in combination (Ranganath, 2012). This explains why many women first notice symptoms years after childbirth: the initial damage creates vulnerability that worsens with aging.

How Common Is This Problem?

The prevalence of fecal incontinence has been substantially updated in recent years. A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis across 80 population-based studies found that approximately one in 12 adults worldwide (8.4%) experiences fecal incontinence, with prevalence increasing significantly with age to over 15% in adults older than 65 (Mack et al., 2024). In the United States, the estimated prevalence is 8.3% in non-institutionalized adults, with rates as high as 16% in those 70 years and older (Ditah et al., 2014; Whitehead et al., 2009).

Childbirth remains the most common predisposing factor in women because it may disrupt the internal or external anal sphincter or damage the pudendal nerve. However, recent research increasingly recognizes that fecal incontinence affects men and women at similar rates in community populations (Mack et al., 2024).

The Defecation Reflex: How Normal Bowel Control Works

When peristalsis—the rhythmic wave-like contractions of your digestive tract—transports fecal material from the sigmoid colon to the rectum, pressure on the rectal wall triggers a defecation reflex. The firing of sacral spine parasympathetic motor neurons shortens the rectum, increasing pressure on the fecal material. This is your body's way of saying "time to go."

Increased pressure within the rectum opens the involuntary internal sphincter—you don't have conscious control over this part. Intentional relaxation of the voluntary external sphincter then expels feces, while constriction postpones defecation (Seymour, 2002). The coordination between these two sphincters is elegant: one responds automatically to pressure, the other gives you conscious control over timing. When this coordination breaks down—whether from muscle weakness, nerve damage, or both—incontinence results.

How Biofeedback Restores Continence

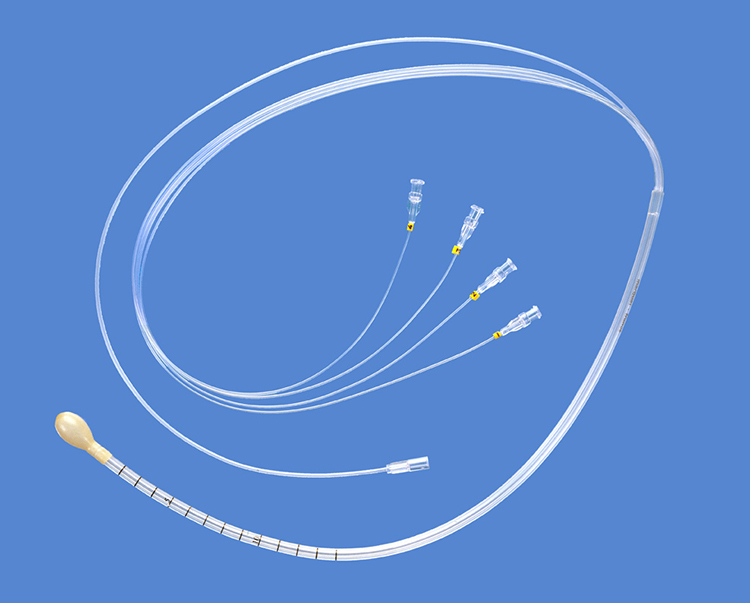

Biofeedback should only be initiated following medical evaluation and conducted under medical supervision—you need to rule out conditions like tumors, inflammatory bowel disease, or rectal prolapse that require different treatment. The primary biofeedback modalities used to treat fecal incontinence are balloon manometers, electromyographs, and ultrasound. Clinicians design treatment protocols to achieve three goals: increase rectal sensitivity (so patients feel fullness earlier and have more warning), strengthen perianal muscles (so patients can "hold it" longer), and improve coordination between the internal and external anal sphincters (Norton & Cody, 2012).

The MindMedia anal EMG probe shown below detects muscle activity associated with the external anal sphincter.

A manometry system places balloons in the anal canal to simulate the movement of fecal material—essentially creating a practice situation without the embarrassment of actual stool. Training teaches the patient to contract the external rectal sphincter when the anal canal balloon expands. This is like a fire drill for your bowel: patients practice their response to the sensation of rectal fullness so that when it happens in real life, the correct muscle response has become automatic.

Evidence for Different Populations

Teo (2016) rated biofeedback for fecal incontinence in adults as level 4, efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (3rd ed.). Biofeedback for chronic fecal incontinence has helped 60-92% of clients.

Vonthein et al. (2013) conducted a meta-analysis showing that continence rates doubled when biofeedback was combined with electrical stimulation. However, Heymen and colleagues (2019) conducted an RCT that found supervised pelvic floor muscle training combined with biofeedback was superior to attention-control treatment for fecal incontinence, supporting the value of structured biofeedback protocols.

Gao and colleagues (2022) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis examining biofeedback therapy for bowel dysfunction following rectal cancer surgery and found improvements in Wexner scores and anorectal manometry parameters, though the authors noted that multicomponent interventions combining biofeedback with PFMT and electrical stimulation make it difficult to isolate biofeedback's specific contribution.

Consider Patricia, a 45-year-old woman who developed fecal incontinence following a difficult vaginal delivery. After 8 sessions of manometric biofeedback combined with pelvic floor exercises and dietary modifications, Patricia learned to detect rectal distension earlier and contract her external sphincter more quickly. Her incontinence episodes decreased from daily to less than once monthly.

Fecal incontinence results from loss of anal sphincter control and affects approximately 8% of adults worldwide, with rates increasing to over 15% in those over 65 years. Biofeedback using EMG, manometry, or ultrasound teaches patients to strengthen the external sphincter and respond appropriately to rectal distension. The treatment is rated efficacious for adults, with 60-92% of clients improving. Research shows combining biofeedback with pelvic floor muscle training and electrical stimulation produces the best outcomes.

Check Your Understanding

- What is the role of the internal versus external anal sphincter in maintaining continence?

- How does manometric biofeedback simulate normal physiological conditions?

- Why is childbirth the most common predisposing factor for fecal incontinence?

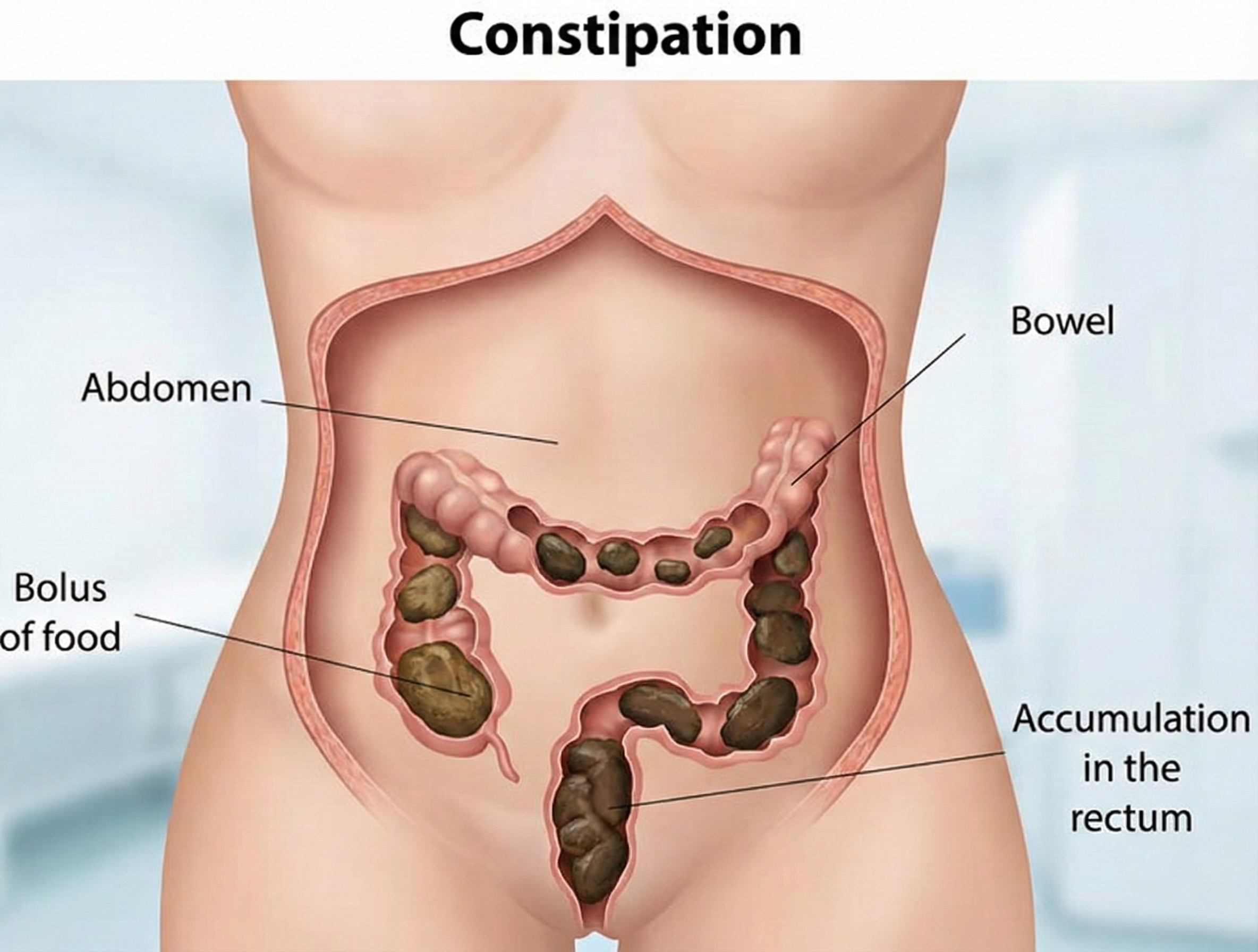

When Elimination Becomes Difficult: Functional Constipation

Functional constipation involves the abnormally slow movement of fecal material through the colon and difficulty in stool evacuation (Gilliland, 1997). The word "functional" is important here—it means the constipation isn't caused by a structural problem like a tumor or stricture. Instead, something has gone wrong with the normal function of the muscles or nerves involved in elimination.

🎧 Listen to the Mini-Lecture on Functional Constipation

Two Distinct Problems

The slow movement of feces, called slow transit constipation, can be caused by chronic laxative abuse (which can make the colon "lazy"), inadequate dietary fiber and fluid consumption, and excessive alcohol or caffeine (Basson, 2015). Problems evacuating stools, termed dyssynergic defecation, account for approximately one-quarter of chronic constipation cases and involve the inability to coordinate the abdominal, rectoanal, and pelvic floor muscles during defecation (Rao & Patcharatrakul, 2016).

This is a critical distinction for treatment: slow transit is a plumbing problem (things move too slowly through the pipes), while dyssynergic defecation is a coordination problem (the exit mechanism doesn't work properly).

This rectoanal incoordination typically manifests in one of three ways: paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter when it should relax (like trying to exit through a door while simultaneously pushing it closed), inadequate propulsive force from the abdominal muscles (not pushing hard enough), or a combination of both (Rao & Patcharatrakul, 2016). Additionally, 50-60% of patients with dyssynergia demonstrate impaired rectal sensation, meaning they may not adequately perceive when stool is present—they've lost their body's natural "time to go" signal.

While the exact etiology remains unclear, contributing factors include faulty toilet habits learned in childhood, painful defecation that trained the muscles to guard reflexively, and obstetric or back injury (Bleijenberg & Kuijpers, 1994; Gilliland, 1997). This last point highlights an important theme: sometimes the body learns protective patterns that become counterproductive long after the original threat has passed.

A Common Complaint

Chronic constipation affects between 9% and 20% of American adults, with a pooled global prevalence of approximately 14% according to systematic reviews using Rome criteria (Bharucha et al., 2020; Suares & Ford, 2011). A recent large-scale population study found that 24% of Americans who reported constipation met the Rome IV criteria for chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), yet fewer than 40% had ever discussed their symptoms with a healthcare provider (Bharucha et al., 2020). Constipation is more common in women, older adults, and those of lower socioeconomic status, and the associated healthcare costs exceed several billion dollars annually in the United States (Nyrop et al., 2007).

What Works Best?

Teo (2016) rated biofeedback for chronic constipation as level 4, efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (3rd ed.).

Biofeedback is superior to treatment as usual, including laxatives and patient education—this is important because laxatives are the typical first-line treatment. Biofeedback appears more effective for correcting difficulty in evacuating stools than the slow movement of feces (Woodward et al., 2014). This makes intuitive sense: biofeedback excels at retraining coordination problems, which is exactly what dyssynergic defecation involves.

Moore and colleagues (2020) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 RCTs involving 725 participants with dyssynergic defecation and found that biofeedback produced significant improvements in global clinical outcomes, with pooled odds of improvement more than three times greater than comparator treatments.

The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility have both assigned biofeedback a Grade A recommendation—their highest endorsement—for treating dyssynergic defecation (Rao & Patcharatrakul, 2016). Even better news: long-term studies demonstrate that benefits persist for at least two years following treatment, suggesting that patients are genuinely relearning the skill rather than just temporarily improving.

Consider Robert, a 52-year-old software engineer who had struggled with chronic constipation for over a decade. Assessment revealed dyssynergic defecation: his external anal sphincter was paradoxically contracting when he attempted to defecate. After 6 sessions of EMG biofeedback teaching him to relax during bearing down, Robert's symptoms improved dramatically.

Functional constipation includes two distinct problems: slow transit constipation (feces move too slowly through the colon) and dyssynergic defecation (the muscles can't coordinate properly to evacuate). Biofeedback is rated efficacious and appears particularly helpful for dyssynergic defecation, where the external sphincter paradoxically contracts during attempted evacuation—essentially closing the door while trying to push through it. Treatment teaches patients to relax during bearing down, correcting this counterproductive pattern.

Because biofeedback excels at retraining coordination problems, it outperforms laxatives for dyssynergic defecation, with benefits lasting at least two years.

Check Your Understanding

- What distinguishes slow transit constipation from dyssynergic defecation?

- Why might biofeedback be more effective for dyssynergic defecation than for slow transit constipation?

- What paradoxical muscle behavior often underlies dyssynergic defecation?

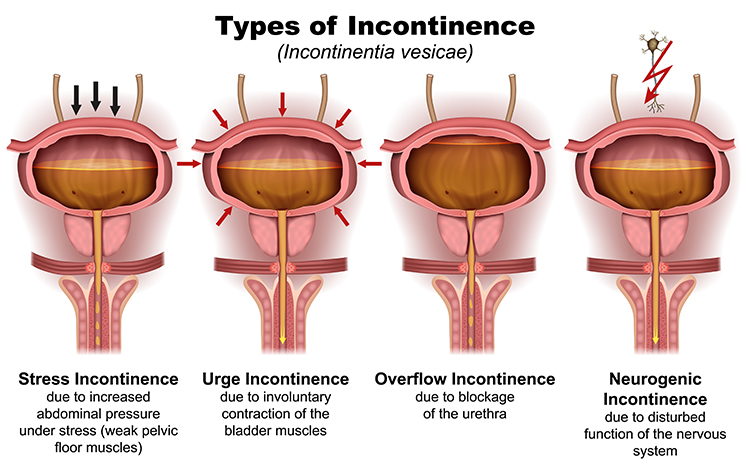

Regaining Bladder Control: Urinary Incontinence

Urinary incontinence (UI) is the involuntary loss of urine. Updated national surveys reveal the scope of this problem is substantially larger than previously estimated—and the numbers are striking. More than 60% of adult women in the United States—approximately 78 million people—experience some form of urinary incontinence, with over 20% experiencing moderate to severe symptoms (Patel et al., 2022). This represents a significant increase from prior estimates of 38-53% using data from 1999-2016.

The prevalence among men, while lower, has also increased, rising from 11.5% in 2001-2002 to approximately 15% in recent surveys (Coyne et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2014). Four common types of incontinence are urge incontinence, stress incontinence, mixed incontinence, and overflow incontinence—each with distinct mechanisms and treatment implications.

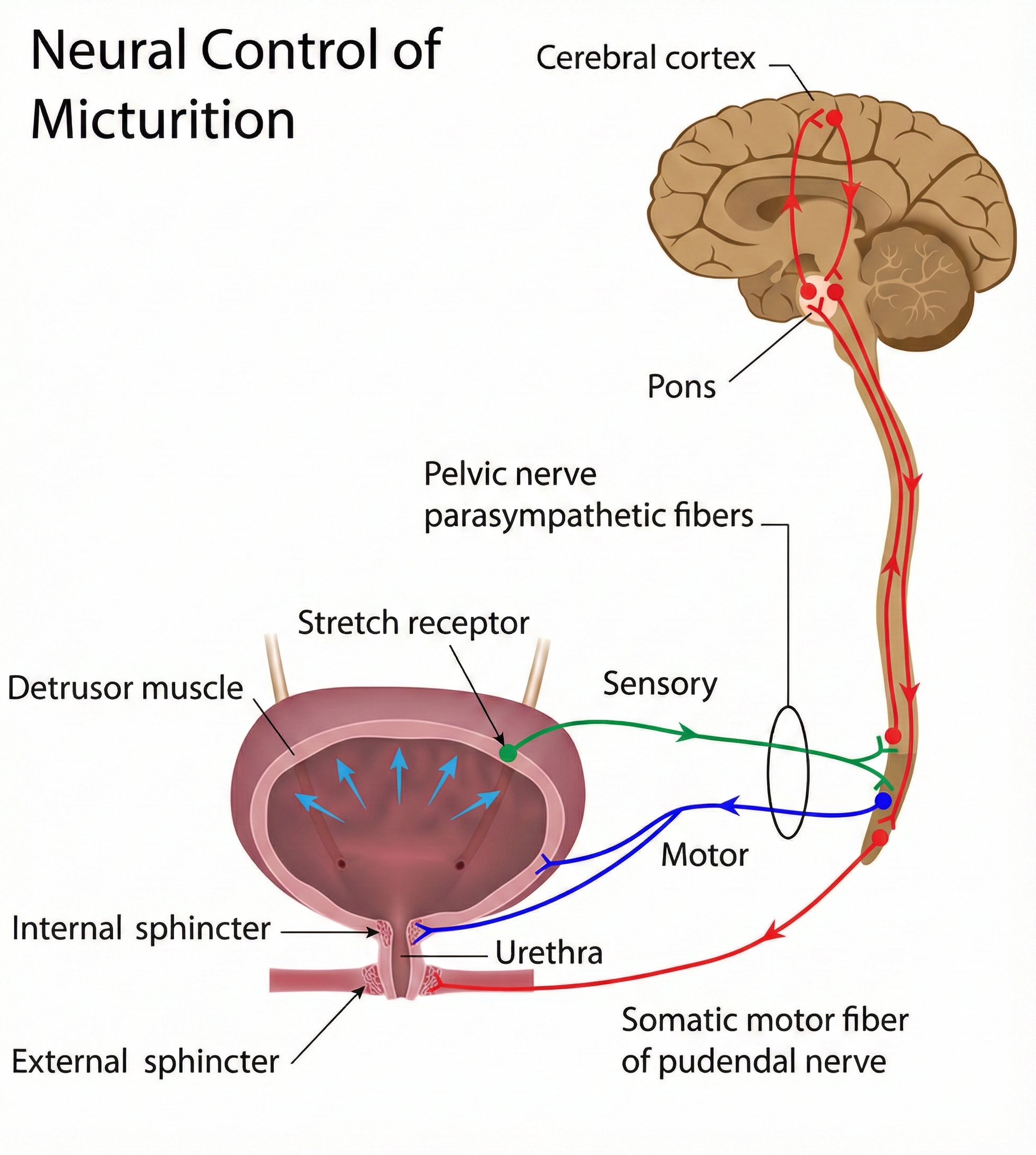

Urge incontinence involves involuntarily emptying the entire bladder due to detrusor overactivity—involuntary contractions of the bladder muscle during the filling phase when it should remain relaxed. Think of it this way: normally your bladder quietly fills like a balloon, waiting patiently until you decide it's time to use the bathroom. With urge incontinence, the bladder muscle starts squeezing on its own, creating an overwhelming sense of urgency and sometimes emptying before you can reach a toilet.

The pathophysiology involves disruption of the normal inhibitory signals from higher brain centers to the pontine micturition center—a brainstem region that coordinates bladder emptying—which normally keeps the bladder relaxed during storage.

Current research suggests that reduced blood flow to the bladder, local inflammation, and increased sensitivity of bladder afferent nerves all contribute to the premature firing signals that produce urgency and frequency (Sellers & Chess-Williams, 2023).

Stress incontinence results from weakness in the pelvic floor muscles and urethral sphincters that cannot maintain closure when intra-abdominal pressure suddenly increases—such as during coughing, sneezing, laughing, or lifting heavy objects. The name refers to physical stress on the bladder, not emotional stress.

Every time you cough, the pressure in your abdomen spikes; normally, strong pelvic floor muscles automatically tighten to keep the urethra closed. When these muscles are weakened—often from childbirth, surgery, or aging—the urethra can't resist the pressure spike, and urine leaks out.

Mixed incontinence combines both stress and urge incontinence (Vasavada, 2014). Many patients experience elements of both, which can complicate treatment planning—you're essentially dealing with two different problems simultaneously.

Overflow incontinence is caused by urethral blockage.

The Scope of the Problem

Recent NHANES data indicate that urinary incontinence is far more prevalent than historically recognized. The age-standardized prevalence in women increased from 49.5% in 2001-2002 to 53.4% in 2007-2008, a trend partially explained by population aging and rising obesity rates (Wu et al., 2014).

Risk factors include vaginal childbirth, obesity (BMI >40), and advancing age. This disorder remains twice as common in women as in men. Urinary incontinence is a primary cause of nursing home admission when it overwhelms families, and it significantly impairs quality of life for millions of Americans (Vasavada, 2014).

How Normal Bladder Control Works

The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular organ located in the pelvic cavity that serves as a reservoir for urine. The intermediate coat is the detrusor muscle—three layers of smooth muscle that contract during urination to squeeze urine out. The movement of urine is controlled by two sphincters working in tandem: the involuntary internal urethral sphincter (which you don't consciously control) and the voluntary external urethral sphincter (which you do control, allowing you to "hold it" when necessary).

Micturition—the medical term for urination—is coordinated by the micturition center in spinal cord segments S2 and S3. When bladder volume exceeds 200-400 ml (roughly a cup to a cup and a half), the micturition reflex is triggered, creating the urge to urinate. This reflex can be overridden by voluntary control of the external sphincter—which is why you can wait to find a bathroom even when your bladder signals it's full.

Biofeedback Treatment Strategies

Clinicians use three strategies to treat UI, each targeting different aspects of the problem. First, reducing detrusor overactivity addresses urge incontinence by helping patients learn to calm their overactive bladder muscle. Second, increasing the strength of pelvic floor muscles addresses stress incontinence by improving the muscular support that keeps the urethra closed. Third, the multimeasurement method combines both approaches—and this turns out to be particularly powerful.

Tries and Brubaker (1996) recommended the multimeasurement method because it achieved superior reductions in incontinence episodes—ranging from 75.9-82%—in about 5 sessions. Why does combining approaches work better? Because many patients have elements of both urge and stress incontinence, and treating just one component leaves the other untreated. The multimeasurement method covers all bases.

Evidence by Population

Women

Based on 20 RCTs, Meehan and Shaffer (2023) rated biofeedback for urinary incontinence in women as level 5, efficacious and specific in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

However, here's an important nuance that reflects how science evolves: Fernandes and colleagues (2025) conducted a comprehensive Cochrane review including 41 RCTs with 3,483 women and found that adding biofeedback to pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) produces little to no difference in incontinence-specific quality of life (high-certainty evidence), and likely results in only a small, clinically unimportant reduction in leakage episodes.

What does this mean for practice? These findings suggest that while biofeedback remains a valid treatment option, well-supervised pelvic floor muscle training alone may achieve comparable outcomes for many women. The biofeedback component may be most valuable when patients struggle to identify and isolate their pelvic floor muscles correctly.

Men

Based on 21 RCTs, Meehan and Shaffer (2023) rated biofeedback for urinary incontinence in men as level 5, efficacious and specific. Most studies involved men who underwent prostatectomy. Wang and colleagues (2016) conducted a meta-analysis of 13 RCTs involving 1,108 post-prostatectomy patients and confirmed that biofeedback-assisted pelvic floor muscle training produces significant improvements in objectively and subjectively measured incontinence at immediate, intermediate, and long-term follow-up compared to PFMT alone.

Costa and colleagues (2025) conducted a more recent meta-analysis that further supported these findings, demonstrating that EMG biofeedback enhances continence recovery after radical prostatectomy, with particular benefits for improving pad use and muscular strength outcomes.

Children

Based on 5 RCTs, Meehan and Shaffer (2023) rated biofeedback for urinary incontinence in children as level 4, efficacious.

Consider Susan, a 48-year-old nurse who developed stress incontinence after her second pregnancy. After 6 sessions using the multimeasurement method, Susan learned to isolate her pelvic floor muscles and contract them quickly when intra-abdominal pressure increased. Her incontinence episodes decreased by 85%.

Urinary incontinence affects 13 million Americans. Biofeedback achieves the highest efficacy rating for both women and men, with the multimeasurement method producing superior results in fewer sessions. However, recent Cochrane evidence suggests that for women, adding biofeedback to well-supervised pelvic floor muscle training may provide only modest additional benefits. For men recovering from prostatectomy, multiple meta-analyses continue to support the added value of biofeedback-assisted training.

Check Your Understanding

- What distinguishes urge incontinence from stress incontinence?

- Why does the multimeasurement method produce better results?

- What roles do the internal and external urethral sphincters play?

Rebuilding Strength After Knee Surgery: Meniscectomy Rehabilitation

After removing meniscus cartilage in the knee, a post meniscectomy patient experiences weakness in the muscles that act on the leg—but here's the counterintuitive part: this weakness is not simply from disuse or muscle damage. A fascinating neurological phenomenon called arthrogenic muscle inhibition (AMI) causes the brain to reflexively "turn down" activation of the quadriceps following knee injury or surgery (Rice & McNair, 2010). Your brain is essentially protecting your knee by not letting you use your full muscle strength.

AMI is triggered by changes in sensory signals from joint mechanoreceptors responding to swelling, inflammation, and joint damage. These altered signals activate inhibitory interneurons in the spinal cord that reduce the firing of motor neurons to the quadriceps—essentially a protective mechanism that limits muscle force to prevent further joint damage. It's like a circuit breaker that trips when the system detects a problem. Unfortunately, this reflexive inhibition can persist long after healing, leading to chronic weakness and increased risk of re-injury (Sonnery-Cottet et al., 2022). The protective mechanism becomes counterproductive, keeping the muscle weak even when the joint is ready to handle normal loads.

🎧 Listen to the Mini-Lecture on Meniscectomy

How Common Are Meniscal Injuries?

Meniscal tears constitute one of the most prevalent intra-articular knee pathologies. The overall prevalence of meniscal tears in adult populations is estimated at 12-14%, with an incidence of approximately 60-61 cases per 100,000 persons (Adams et al., 2021; Bhan, 2020). Males experience meniscal tears at approximately 2.5 times the rate of females. Acute trauma-related tears predominate in active young populations, while degenerative tears affect older adults, with peak onset in men at 41-50 years and in women at 61-70 years.

Risk factors include male sex, age over 40 years, work-related kneeling and squatting, and participation in high-impact sports such as soccer, rugby, and basketball (Snoeker et al., 2013). The incidence of meniscal surgeries in the United States is approximately 17 procedures per 100,000 people, making meniscus surgery one of the most common orthopedic procedures.

Training the Quadriceps

EMG biofeedback is particularly valuable for overcoming arthrogenic muscle inhibition because it provides visual confirmation that muscles are activating—information the brain may not be receiving through normal proprioceptive channels.

This is where biofeedback shines: when the normal feedback loop is disrupted, external feedback fills the gap. SEMG electrodes may be placed over the quadriceps femoris, particularly the vastus medialis oblique (VMO)—the teardrop-shaped muscle on the inner thigh just above the knee that's often preferentially inhibited after knee injury—to assist in practicing contractions to increase muscle strength.

Biofeedback helps patients bypass the inhibited neural pathway by providing an alternative feedback route through vision and hearing (Sonnery-Cottet et al., 2022). Patients can see their muscle working on the screen even when they can't feel it working normally—and this visual evidence helps convince the brain that it's safe to activate the muscle more strongly.

The vastus lateralis and vastus medialis are trained following meniscectomy.

Total Knee Arthroplasty

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA)—commonly known as knee replacement surgery—treats severe knee pain by replacing the damaged joint surfaces with metal and plastic prosthetic components. It's one of the most common orthopedic surgeries performed in the United States. Patients must usually achieve 90-degree knee flexion before hospital discharge (Palmer & Cross, 2004).

This isn't an arbitrary number—90 degrees allows you to sit comfortably in a chair, climb stairs, and perform basic daily activities. Reaching this milestone requires overcoming both post-surgical stiffness and the arthrogenic muscle inhibition that prevents full quadriceps activation.

Research on Biofeedback for Knee Rehabilitation

Kuiken, Amir, and Scheidt (2004) studied patients following total knee arthroplasty. A computerized biofeedback knee joint goniometer (CBG) provides audiovisual feedback about knee joint angle.

Recent research has clarified both the neurophysiology and treatment of AMI. EMG biofeedback is thought to work by providing an alternative neural pathway through visual and auditory feedback, helping patients bypass inhibited proprioceptive channels (Gabler et al., 2013).

Ananías and colleagues (2024) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of EMG biofeedback following ACL reconstruction and found that biofeedback improved knee extension range of motion compared to standard rehabilitation.

Additionally, Chen and colleagues (2021) conducted a meta-analysis of six RCTs and found that EMG biofeedback significantly improved knee ROM in post-surgical patients, though effects on pain and overall function were comparable to other rehabilitation methods. These findings support EMG biofeedback as a valuable adjunct for overcoming quadriceps inhibition in the early postoperative period.

Evidence Status

Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.) did not evaluate this application.

Consider Tom, a 67-year-old retired firefighter who underwent total knee arthroplasty. Using SEMG biofeedback over his vastus medialis and vastus lateralis, Tom learned to activate more motor units. Within two weeks, his quadriceps strength had improved enough to meet discharge criteria.

Meniscectomy and total knee arthroplasty leave patients with weakened quadriceps muscles—not because the muscle tissue is damaged, but because the brain reflexively "turns down" activation through arthrogenic muscle inhibition (AMI). This protective mechanism persists even after the joint has healed. SEMG biofeedback helps increase motor unit recruitment during rehabilitation by providing visual confirmation that muscles are activating—bypassing the inhibited proprioceptive pathway. This is a perfect example of how biofeedback fills gaps in the normal feedback loop, helping patients recruit motor units that the brain has put on involuntary leave.

Check Your Understanding

- Why should electrode spacing initially be wide when training weak quadriceps?

- What is the significance of achieving 90-degree knee flexion following TKA?

Teaching Muscles New Tricks: Muscle-Tendon Transfer

Muscle-tendon transfer is a clever surgical procedure that repositions a tendon so that an attached muscle can produce a new movement (Baumeister, 2013). Imagine losing the ability to extend your wrist—you can't lift your hand, making countless daily activities nearly impossible. A surgeon might detach a functioning wrist flexor muscle from its original attachment point and reattach it to the other side of the wrist, converting it from a flexor into an extensor. The muscle now pulls in a different direction, producing the opposite movement from before.

🎧 Listen to the Mini-Lecture on Muscle-Tendon Transfer

The Challenge of Relearning Movement

Here's where it gets interesting from a biofeedback perspective: SEMG biofeedback increases motor unit recruitment in re-educated muscles, but the real challenge is cognitive. The brain still "thinks" the muscle is a flexor. When the patient tries to extend their wrist, their brain automatically sends signals to the original extensors (which may be paralyzed) rather than to the transferred muscle. The patient must learn to "think flexion" to produce extension—a profoundly unnatural cognitive task.

A Thought Technology Ltd. electrogoniometer places a potentiometer over two bones that form a joint and displays 180 degrees of joint angle changes. This provides feedback about the movement outcome rather than the muscle activity, which can be more intuitive for patients struggling to rewire their movement patterns.

Evidence Status

Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.) did not evaluate this application.

Consider Daniel, a 32-year-old carpenter who lost function in his wrist extensors. Surgeons performed a tendon transfer, repositioning a wrist flexor tendon to restore extension. Using electrogoniometer biofeedback, Daniel gradually learned to "think flexion" while producing extension. After 16 sessions, the new movement pattern became automatic.

Muscle-tendon transfer repositions tendons to restore lost motor function—for example, converting a wrist flexor into an extensor. The surgical part is straightforward; the hard part is cognitive retraining. Because the brain still "thinks" the muscle does its original job, patients must learn to "think flexion" to produce extension. Biofeedback helps patients navigate this profoundly counterintuitive process by providing feedback about either muscle activity (EMG) or movement outcome (electrogoniometer). Over time, the new movement pattern becomes automatic—a remarkable example of neural plasticity and motor learning.

Check Your Understanding

- Why might a patient need to "think flexion" to produce extension following a tendon transfer?

- When is electrogoniometer feedback preferable to SEMG feedback?

Cutting-Edge Topics in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation

Wearable EMG Sensors Transform Home-Based Rehabilitation

Recent advances in wearable sensor technology are making it possible for patients to receive high-quality EMG biofeedback during home exercises—solving one of biofeedback's traditional limitations: the need to come to a clinic for every training session. New flexible, textile-integrated electrodes can be worn comfortably throughout the day, providing continuous feedback on muscle activation patterns.

Studies suggest that patients who use wearable biofeedback devices during home exercise programs show significantly better adherence and outcomes than those using traditional exercise instructions alone. This technology could dramatically expand access to biofeedback training, particularly for patients in rural areas or those with mobility limitations.

Virtual Reality Enhances Pelvic Floor Training

Researchers are exploring how virtual reality (VR) environments can make pelvic floor biofeedback training more engaging and effective—addressing the motivation challenge that plagues any exercise program. In these systems, patients wear VR headsets while their pelvic floor muscle activity controls elements of an immersive game or environment. Contract your pelvic floor, and your avatar jumps higher or your character moves faster. Early trials suggest that patients find VR-enhanced training more motivating than traditional screen-based feedback, and higher motivation translates to more practice and better outcomes.

Artificial Intelligence Personalizes Treatment Protocols

Machine learning algorithms are beginning to analyze EMG patterns to predict which patients will respond best to specific biofeedback protocols—moving toward truly personalized medicine. By examining factors such as baseline muscle activation patterns, learning curves during initial sessions, and patient characteristics, these AI systems can suggest personalized treatment modifications. Instead of one-size-fits-all protocols, clinicians may soon have AI assistants that recommend "based on this patient's learning pattern, try increasing the difficulty faster" or "this patient shows signs of muscle substitution—add exercises to isolate the target muscle."

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Create New Diagnostic Challenges for Pelvic Floor Assessment

As GLP-1 receptor agonists like Ozempic®, Wegovy®, and Mounjaro® become increasingly common for diabetes and weight management, a new clinical challenge is emerging: patients are reporting gastrointestinal symptoms that are difficult to differentiate from underlying pelvic floor disorders. These medications work by slowing gastric emptying, suppressing appetite, and improving glycemic control—but their effects on motility extend beyond the upper GI tract.

Large-scale real-world studies using the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System have documented that GLP-1 receptor agonists are significantly associated with gastrointestinal adverse events including constipation, with semaglutide showing the highest risk (Liu et al., 2022). A multidisciplinary expert consensus confirmed that constipation occurs in up to 25% of patients on higher doses used for obesity treatment, with symptoms typically developing during dose escalation (Gorgojo-Martínez et al., 2023).

For clinicians treating pelvic floor dysfunction, this creates a diagnostic puzzle: when a patient on semaglutide reports new-onset constipation or incomplete evacuation, does the symptom reflect medication-induced motility changes, or has the medication unmasked a previously subclinical case of dyssynergic defecation?

Anorectal manometry (ARM) provides a solution by offering objective measurements of rectal sensation, sphincter function, and pelvic floor coordination. The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society has established ARM as a first-line diagnostic tool for defecatory disorders, essential for distinguishing between medication side effects and true pelvic floor dysfunction (Rao & Patcharatrakul, 2016).

When used in patients experiencing lower GI symptoms while taking GLP-1 medications, ARM can differentiate drug-related motility effects from dyssynergic defecation, quantify the severity of anorectal dysfunction to guide treatment planning, establish a baseline prior to initiating biofeedback therapy, and monitor progress during conservative management.

For patients with persistent constipation, ARM can determine whether paradoxical anal contraction is contributing to delayed evacuation—guiding appropriate therapy beyond simply adjusting medication. Conducting ARM before initiating GLP-1 therapy in patients with a history of functional GI issues provides a valuable baseline; if symptoms worsen, clinicians can compare data to determine causality.

As the landscape of metabolic treatment evolves, integrating ARM into the evaluation of GLP-1 users ensures clinicians have the functional data necessary to provide targeted, effective therapy.

Test Yourself

Click on the ClassMarker logo to take 10-question tests over this unit without an exam password.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Visit the BioSource Software Website

BioSource Software offers Human Physiology, which satisfies BCIA's Human Anatomy and Physiology requirement, and Biofeedback100, which provides extensive multiple-choice testing over BCIA's Biofeedback Blueprint.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this module, consider the conditions where muscle activity should be decreased (blepharospasm, dyssynergic defecation) versus increased (post-meniscectomy weakness, erectile dysfunction). Notice how intact proprioception is the common thread—these clients can feel their bodies normally, but their muscles have learned unhelpful patterns or lost strength. How would you explain to a new client why their intact proprioception makes biofeedback training particularly effective for musculoskeletal conditions? Think about it this way: you're not replacing their internal feedback system, you're augmenting it with additional information that helps them learn faster and more precisely.

Glossary

2021 National Survey of Sexual Wellbeing: a nationally representative cross-sectional survey conducted in the United States to assess the prevalence and characteristics of sexual health concerns, including erectile dysfunction, across diverse demographic groups.

anal EMG probe: an internal EMG electrode consisting of two active electrodes inserted in the rectum and an external reference electrode to measure and train pelvic floor muscles.

anorectal manometry (ARM): a diagnostic test that measures anal sphincter pressures, rectal sensation, rectoanal reflexes, and rectal compliance to evaluate defecatory disorders and guide biofeedback therapy.

arthrogenic muscle inhibition (AMI): a reflexive neural mechanism in which sensory signals from an injured or swollen joint activate inhibitory interneurons in the spinal cord, reducing motor neuron output to surrounding muscles as a protective response.

basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuit: a network of brain structures including the basal ganglia, thalamus, and motor cortex that regulates voluntary movement; dysfunction in this circuit contributes to movement disorders including dystonia.

blepharospasm: spasms of the eyelids characterized by bilateral blinking that results in symptoms ranging from increased blinking to disabling interference with vision.

computerized biofeedback knee joint goniometer (CBG): a biofeedback instrument that provides audiovisual feedback about knee joint angle.

chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC): a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by unsatisfactory defecation due to difficult, infrequent, or incomplete evacuation in the absence of identifiable structural or biochemical abnormality, as defined by Rome diagnostic criteria.

defecation reflex: a response triggered by pressure on the rectal wall that activates sacral spine parasympathetic motor neurons.

detrusor overactivity: involuntary contractions of the bladder's detrusor muscle during the filling phase, often causing urinary urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence.

detrusor muscle: the intermediate coat of the urinary bladder composed of three smooth muscle layers.

dyssynergic defecation: difficulty evacuating stools due to dysfunctional anal contraction/relaxation or insufficient effort.

electrogoniometer: an electronic device that measures the range of motion by placing a potentiometer over two bones that form a joint.

endothelial dysfunction: impaired ability of the blood vessel lining (endothelium) to regulate vascular tone, typically involving reduced production of nitric oxide; a key mechanism in erectile dysfunction.

erectile dysfunction (ED): the inability to achieve or maintain an erection for acceptable sexual performance.

external anal sphincter: an elliptically-shaped voluntary muscle that closes the anal canal and orifice.

external urethral sphincter: the voluntary ring of skeletal muscle that controls urine flow through the urethra.

fecal incontinence: the involuntary release of feces or gas due to loss of anal sphincter control.

focal dystonia: a movement disorder characterized by sustained or intermittent muscle contractions causing abnormal, often repetitive, movements or postures affecting a specific body region.

functional constipation: abnormally slow movement of fecal material through the colon and difficulty in stool evacuation.

gastric emptying: the process by which stomach contents are transferred to the duodenum; slowed gastric emptying is a primary mechanism of GLP-1 receptor agonists and contributes to gastrointestinal side effects.

Grade A recommendation: the highest level of clinical recommendation, indicating strong evidence from multiple high-quality randomized controlled trials supporting the use of an intervention.

GLP-1 receptor agonists: a class of medications (including semaglutide, liraglutide, and tirzepatide) that mimic the glucagon-like peptide-1 hormone to improve glycemic control and promote weight loss; common gastrointestinal side effects include nausea, constipation, and diarrhea.

internal anal sphincter: the muscular ring of involuntary muscle that helps control defecation.

internal urethral sphincter: an involuntary ring of smooth muscle around the urethra's opening.

ischiocavernosus muscle (ICM): a pelvic floor muscle that produces rigidity during the muscular phase of erection.

manometry system: an anorectal probe that places balloons in the anal canal to simulate fecal material movement.

meniscectomy: the surgical removal of torn knee fibrocartilage.

micturition: urine discharge produced by the contraction of involuntary and voluntary muscles.

micturition center: located in segments S2 and S3 of the sacral spinal cord, it triggers the micturition reflex.

micturition reflex: when bladder volume exceeds 200-400 ml, the micturition center signals the detrusor muscle to contract.

mixed incontinence: the involuntary loss of urine resulting from both stress and urge incontinence.

muscle-tendon transfer: a surgical procedure that repositions a tendon so that an attached muscle can produce a new movement.

nitric oxide (NO): a gaseous signaling molecule released by nerve terminals and endothelium that causes smooth muscle relaxation; the primary mediator of penile erection.

orbicularis oculi: the facial muscle that closes the eyelids and wrinkles the forehead.

overflow incontinence: urinary incontinence due to urethral blockage.

pelvic-floor biofeedback training (PFBT): a multimodal approach combining pelvic floor muscle exercises, EMG biofeedback, and often electrical stimulation.

pontine micturition center: a brainstem region that coordinates bladder emptying by signaling the detrusor to contract while relaxing the urethral sphincters; normally inhibited during the storage phase.

post meniscectomy patient: an individual who has had torn knee fibrocartilage removed.

proprioception: our sense of our body's position and movement.

prostatectomy: the surgical removal of the prostate.

pudendal nerve: a mixed sensory-motor nerve (S2-S4) that innervates the external anal sphincter, pelvic floor muscles, and perianal skin; damage contributes to fecal incontinence.

quadriceps femoris: the great leg extensor composite muscle consisting of the rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius.

rectoanal incoordination: the failure to coordinate abdominal push effort with relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles during defecation; the core mechanism of dyssynergic defecation.

slow transit constipation: the slow movement of feces through the colon.

stress incontinence: the involuntary loss of urine when intra-abdominal pressure increases.

total knee arthroplasty (TKA): the replacement of the knee with a prosthesis.

urge incontinence: involuntarily emptying the entire bladder produced by detrusor muscle overactivity.

urinary bladder: a hollow, muscular organ located in the pelvic cavity that collects and stores urine.

urinary incontinence: the involuntary loss of urine.

vastus lateralis: a component of the quadriceps femoris located on the lateral thigh.

vastus medialis: a component of the quadriceps femoris located on the medial thigh.

vastus medialis oblique (VMO): the distal, obliquely-oriented fibers of the vastus medialis that play a critical role in patellar tracking and knee stability; often preferentially inhibited following knee injury.

References

Adams, B. G., Houston, M. N., & Cameron, K. L. (2021). The epidemiology of meniscus injury. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review, 29(3), e24-e33. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSA.0000000000000329

Ananías, J., Vidal, C., Ortiz-Muñoz, L., Irarrázaval, S., & Besa, P. (2024). Use of electromyographic biofeedback in rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy, 123, 19-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2023.12.005

Baker, B. S. (2014). Meniscus injuries. eMedicine.

Basmajian, J. V. (Ed.). (1989). Biofeedback: Principles and practice for clinicians. Williams & Wilkins.

Basson, M. D. (2015). Constipation. eMedicine.

Bassotti, G., Chistolini, F., Sietchiping-Nzepa, F., de Roberto, G., Morelli, A., & Chiarioni, G. (2004). Biofeedback for pelvic floor dysfunction in constipation. BMJ, 328(7436), 393-396.

Baumeister, S. (2013). Hand tendon transfers. eMedicine.

Benet, A. E., & Melman, A. (1995). The epidemiology of erectile dysfunction. Urologic Clinics of North America, 22(4), 699-709.

Bhan, K. (2020). Meniscus tear: Pathology, incidence, and management. Cureus, 12(5), e8291. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8291

Bharucha, A. E., Lacy, B. E., & Rao, S. S. C. (2020). Chronic constipation in the United States: Results from a population-based survey assessing healthcare seeking and use of pharmacotherapy. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 115(6), 895-905. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000000606

Bleijenberg, G., & Kuijpers, H. C. (1994). Biofeedback treatment of constipation: A comparison of two methods. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 89(7), 1021-1026.

Burnett, A. L., et al. (2007). Erectile function outcome reporting after clinically localized prostate cancer treatment. Journal of Urology, 178(2), 597-601.

Burnett, A. L. (2022). Medical and surgical therapy of erectile dysfunction. In K. R. Feingold, B. Anawalt, M. R. Blackman, A. Boyce, G. Chrousos, E. Corpas, W. W. de Herder, K. Dhatariya, K. Dungan, J. Hofland, S. Kalra, G. Kaltsas, N. Kapoor, C. Koch, P. Kopp, M. Korbonits, C. S. Kovacs, W. Kuohung, B. Laferrère, M. Levy, E. A. McGee, R. McLachlan, M. New, J. Purnell, R. Sahay, A. S. Shah, F. Singer, M. A. Sperling, C. A. Stratakis, D. L. Trence, & D. P. Wilson (Eds.), Endotext. MDText.com, Inc. PMID: 25905332

Chen, H., Wang, L., Xing, F., Li, D., Xie, Y., Zhou, M., & Deng, Y. (2021). Effects of electromyography biofeedback for patients after knee surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Biomechanics, 119, 110308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110308

Coyne, K. S., Sexton, C. C., Thompson, C. L., Milsom, I., Irwin, D., Kopp, Z. S., Chapple, C. R., Kaplan, S., Tubaro, A., Aiyer, L. P., & Wein, A. J. (2012). The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, the UK and Sweden: Results from the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU International, 104(3), 352-360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08427.x

Costa, A. R. S., Santana, A. R. O. R., da Paz, A. R. M., Carnaúba, A. T. L., de Andrade, K. C. L., & de Lemos Menezes, P. (2025). The impact of using electromyographic biofeedback on pelvic floor rehabilitation in men with post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence: A meta-analysis. Clinics, 80, 100578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinsp.2024.100578

Ditah, I., Devaki, P., Luma, H. N., Ditah, C., Njei, B., Jaiyeoba, C., Salami, A., Ditah, C., Ewelukwa, O., & Szarka, L. (2014). Prevalence, trends, and risk factors for fecal incontinence in United States adults, 2005-2010. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 12(4), 636-643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.020

Defazio, G., Hallett, M., Jinnah, H. A., & Berardelli, A. (2017). Blepharospasm 40 years later. Movement Disorders, 32(4), 498-509. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26934

Dorey, G., et al. (2004). Pelvic floor exercises for treating post-micturition dribble in men with erectile dysfunction: A randomized controlled trial. Urologic Nursing, 24(6), 490-497.

Dorey, G., et al. (2005). Pelvic floor exercises for erectile dysfunction. BJU International, 96(4), 595-597.

Dubbelman, Y. D., Dohle, G. R., & Schroder, F. H. (2006). Sexual function before and after radical retropubic prostatectomy. European Urology, 50(4), 711-718.

Enck, P., Van der Voort, I. R., & Klosterhalfen, S. (2009). Biofeedback therapy in fecal incontinence and constipation. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 21(11), 1133-1141.

Fernandes, A. C. N., Jorge, C. H., Weatherall, M., Ribeiro, I. V., Wallace, S. A., & Hay-Smith, E. J. C. (2025). Pelvic floor muscle training with feedback or biofeedback for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3(3), CD009252. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009252.pub2

Gabler, C., Kitzman, P. H., & Mattacola, C. G. (2013). Targeting quadriceps inhibition with electromyographic biofeedback: A neuroplastic approach. Critical Reviews in Biomedical Engineering, 41(2), 125-135. https://doi.org/10.1615/CritRevBiomedEng.2013008373

Gao, J. L., Tang, K., Liu, J., Qu, Q., Huang, X., Mo, N., Su, L., Gao, H., Zhong, H., Ruan, X., Ruan, J., & Yang, J. (2022). Effectiveness of biofeedback therapy in patients with bowel dysfunction following rectal cancer surgery: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 103(7), 1428-1440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2021.10.024

Gibbons, C. H., & Engstrom, J. W. (2018). Disorders of the autonomic nervous system. In Harrison's principles of internal medicine (20th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Gilliland, R., et al. (1997). Outcome and predictors of success of biofeedback for constipation. British Journal of Surgery, 84(8), 1123-1126.

Goldstein, I., Goren, A., Li, V. W., Tang, W. Y., & Hassan, T. A. (2020). Epidemiology update of erectile dysfunction in eight countries with high burden. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 8(1), 48-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.06.008

Gorgojo-Martínez, J. J., Mezquita-Raya, P., Carretero-Gómez, J., Castro, A., Cebrián-Cuenca, A., de Torres-Sánchez, A., García-de-Lucas, M. D., Gimeno-Orna, J. A., Górriz, J. L., López-Simarro, F., Morales, C., & Artola-Menéndez, S. (2023). Clinical recommendations to manage gastrointestinal adverse events in patients treated with GLP-1 receptor agonists: A multidisciplinary expert consensus. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12010145

Graham, R. H. (2014). Benign essential blepharospasm. eMedicine.

Herderschee, R., et al. (2011). Feedback or biofeedback to augment pelvic floor muscle training for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7), CD009252.

Heymen, S., Scarlett, Y., Jones, K., Ringel, Y., Drossman, D., & Whitehead, W. E. (2019). Controlling faecal incontinence in women by performing anal exercises with biofeedback or loperamide: A randomised clinical trial. Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 4(9), 698-710. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30193-X

Hamed, S. M., Fawzy, M. K., Mohamed, S. M., Ashour, A. H., Aboushanab, M. H. E., & Hagag, S. S. (2024). Oxidative stress and erectile dysfunction: Pathophysiology, impacts, and potential treatments. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 46(8), 8807-8834. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb46080521

Imamura, M., et al. (2010). Systematic review and economic modeling of the effectiveness of non-surgical treatments for women with stress urinary incontinence. Health Technology Assessment, 14(40), 1-88.

Kuiken, T. A., Amir, H., & Scheidt, R. A. (2004). Computerized biofeedback knee goniometer: Acceptance and effect on exercise behavior in post-total knee arthroplasty rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85(6), 1026-1030.

Knowles, C. H., Dinning, P., Scott, S. M., Swash, M., & de Wachter, S. (2022). New concepts in the pathophysiology of fecal incontinence. Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery, 7, 17. https://doi.org/10.21037/ales-2022-02

Lue, T. F. (2000). Erectile dysfunction. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(24), 1802-1813. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200006153422407

Liu, L., Chen, J., Wang, L., Chen, C., & Chen, L. (2022). Association between different GLP-1 receptor agonists and gastrointestinal adverse reactions: A real-world disproportionality study based on FDA adverse event reporting system database. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13, 1043789. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1043789

Mack, I., Hahn, H., Gödel, C., Enck, P., & Bharucha, A. E. (2024). Global prevalence of fecal incontinence in community-dwelling adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 22(4), 712-731.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2023.09.004

Maiorino, M. I., Bellastella, G., Della Volpe, E., Casciano, O., Scappaticcio, L., Longo, M., Giugliano, D., & Esposito, K. (2024). Erectile dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: A narrative review. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 207, 111072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2023.111072

Mark, K. P., Arenella, K., Girard, A., Herbenick, D., Fu, J., & Coleman, E. (2024). Erectile dysfunction prevalence in the United States: Report from the 2021 National Survey of Sexual Wellbeing. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 21(4), 296-303. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsxmed/qdae008

Meehan, Z. M., Shaffer, F., & Zerr, C. L. (2023). Erectile dysfunction. In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). AAPB.

Meehan, Z. M., Shaffer, F., & Zerr, C. L. (2023). Urinary incontinence in adult men. In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). AAPB.

Meehan, Z. M., Shaffer, F., & Zerr, C. L. (2023). Urinary incontinence in adult women. In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). AAPB.

Meehan, Z. M., Shaffer, F., & Zerr, C. L. (2023). Urinary incontinence in children. In I. Khazan, F. Shaffer, D. Moss, R. Lyle, & S. Rosenthal (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (4th ed.). AAPB.

Moore, D., Young, C. J., & Shim, R. (2020). A systematic review and meta-analysis of biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defaecation in adults. Techniques in Coloproctology, 24(9), 909-918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-020-02230-9

Norton, C., & Cody, J. D. (2012). Biofeedback and/or sphincter exercises for the treatment of faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7), CD002111.

Nguyen, H. M. T., Gabrielson, A. T., & Bhatt, A. (2017). Erectile dysfunction in young men—A review of the prevalence and risk factors. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 5(4), 508-520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.05.004

Nyrop, K. A., Palsson, O. S., Levy, R. L., Korff, M. V., Feld, A. D., Turner, M. J., & Whitehead, W. E. (2007). Costs of health care for irritable bowel syndrome, chronic constipation, functional diarrhoea and functional abdominal pain. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 26(2), 237-248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03370.x

Palmer, S. H., & Cross, M. J. (2004). Total knee arthroplasty. eMedicine.

Patel, U. J., Godecker, A. L., Giles, D. L., & Brown, H. W. (2022). Updated prevalence of urinary incontinence in women: 2015-2018 national population-based survey data. Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery, 28(4), 181-187. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000001127

Prota, C., et al. (2012). Early postoperative pelvic-floor biofeedback improves erectile function in men undergoing radical prostatectomy. International Journal of Impotence Research, 24(5), 174-178.

Ranganath, S. (2012). Fecal incontinence. eMedicine.

Rao, S. S. C. (2004). Pathophysiology of adult fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology, 126(1 Suppl 1), S14-S22. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.013

Rao, S. S. C., & Patcharatrakul, T. (2016). Diagnosis and treatment of dyssynergic defecation. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 22(3), 423-435. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm16060

Rice, D. A., & McNair, P. J. (2010). Quadriceps arthrogenic muscle inhibition: Neural mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 40(3), 250-266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.10.001

Seftel, A. D., Sun, P., & Swindle, R. (2004). The prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus and depression in men with erectile dysfunction. Journal of Urology, 171(6), 2341-2345.

Selvin, E., Burnett, A. L., & Platz, E. A. (2007). Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. American Journal of Medicine, 120(2), 151-157.

Sellers, D. J., & Chess-Williams, R. (2023). Pathophysiological mechanisms involved in overactive bladder/detrusor overactivity. Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports, 18, 123-131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11884-023-00690-x

Seymour, R. J. (2002). Defecation. In Campbell-Walsh urology. Saunders.

Shamloul, R., & Ghanem, H. (2013). Erectile dysfunction. The Lancet, 381(9861), 153-165.

Snoeker, B. A., Bakker, E. W., Kegel, C. A., & Lucas, C. (2013). Risk factors for meniscal tears: A systematic review including meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 43(6), 352-367. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2013.4295

Sonnery-Cottet, B., Hopper, G. P., Gousopoulos, L., Vieira, T. D., Thaunat, M., Fayard, J. M., Freychet, B., Ouanezar, H., Cavaignac, E., & Saithna, A. (2022). Arthrogenic muscle inhibition following knee injury or surgery: Pathophysiology, classification, and treatment. JISAKOS, 7(3), 145-150. https://doi.org/10.1177/26350254221086295

Solomon, M. J., et al. (2003). Randomized, controlled trial of biofeedback with anal manometry, transanal ultrasound, or pelvic floor retraining with digital guidance alone. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum, 46(6), 703-710.

Suares, N. C., & Ford, A. C. (2011). Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: Systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 106(9), 1582-1591. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2011.164

Teo, I. (2016). Fecal incontinence. In G. Tan, F. Shaffer, R. R. Lyle, & I. Teo (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (3rd ed.). AAPB.

Teo, I. (2016). Functional constipation. In G. Tan, F. Shaffer, R. R. Lyle, & I. Teo (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in biofeedback and neurofeedback (3rd ed.). AAPB.

Tries, J., & Brubaker, L. (1996). Application of biofeedback in the treatment of urinary incontinence. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 27(6), 554-560.

Van Kampen, M., et al. (2000). Effect of pelvic floor re-education on duration and degree of incontinence after radical prostatectomy. Lancet, 355(9198), 98-102.

Van Kampen, M., et al. (2003). Biofeedback in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Physiotherapy, 89(4), 222-226.

Vasavada, S. P. (2014). Urinary incontinence. eMedicine.

Vonthein, R., et al. (2013). Electrical stimulation and biofeedback for the treatment of fecal incontinence: A systematic review. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 28(11), 1567-1577.

Walsh, P. C., Epstein, J. I., & Lowe, F. C. (1987). Potency following radical prostatectomy with wide unilateral excision of the neurovascular bundle. Journal of Urology, 138(4), 823-827.

Wang, W., Huang, Q. M., Liu, F. P., & Mao, Q. Q. (2016). Beneficial effects of biofeedback-assisted pelvic floor muscle training in patients with urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 60, 94-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.04.001

Whitehead, W. E., Borrud, L., Goode, P. S., Meikle, S., Mueller, E. R., Tuteja, A., Weidner, A., Weinstein, M., & Ye, W. (2009). Fecal incontinence in US adults: Epidemiology and risk factors. Gastroenterology, 137(2), 512-517. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.054