Cardiovascular Applications

What You Will Learn

Your heart beats roughly 100,000 times every day without you having to think about it. But when that rhythm goes haywire, the consequences can range from mildly annoying "skipped beats" to life-threatening emergencies. The good news? Your cardiovascular system is not entirely on autopilot. With the right training, you can learn to influence your heart rate, blood pressure, and autonomic balance in ways that genuinely improve health outcomes.

This unit explores how biofeedback taps into that potential. You will discover why the definition of "normal" blood pressure dropped in 2017, instantly reclassifying millions of Americans as hypertensive, and what that shift means for treatment. You will learn the basic plumbing of blood pressure regulation, including why a tiny change in the diameter of your smallest arteries can send your blood pressure soaring. You will examine the six factors that separate successful hypertension treatments from failures, and the multiple biological pathways through which clients can lower their numbers.

Beyond high blood pressure, you will explore how HRV biofeedback is showing promise for conditions like vasovagal syncope (the common fainting spell), heart failure, and coronary artery disease. You will also encounter the surprising research showing that people can learn to voluntarily control irregular heartbeats. By the end of this chapter, you should understand both why cardiovascular biofeedback works and how to apply it effectively in clinical practice.

Here is a sobering reality check for anyone who thinks heart health is someone else's problem: O'Hearn and colleagues (2022) reported that cardiometabolic health among American adults actually declined between 1999 and 2018. By the end of that period, fewer than 7% of US adults qualified as being in optimal cardiometabolic shape. The researchers tracked multiple markers, including body fat, blood lipids and sugar, blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease incidence.

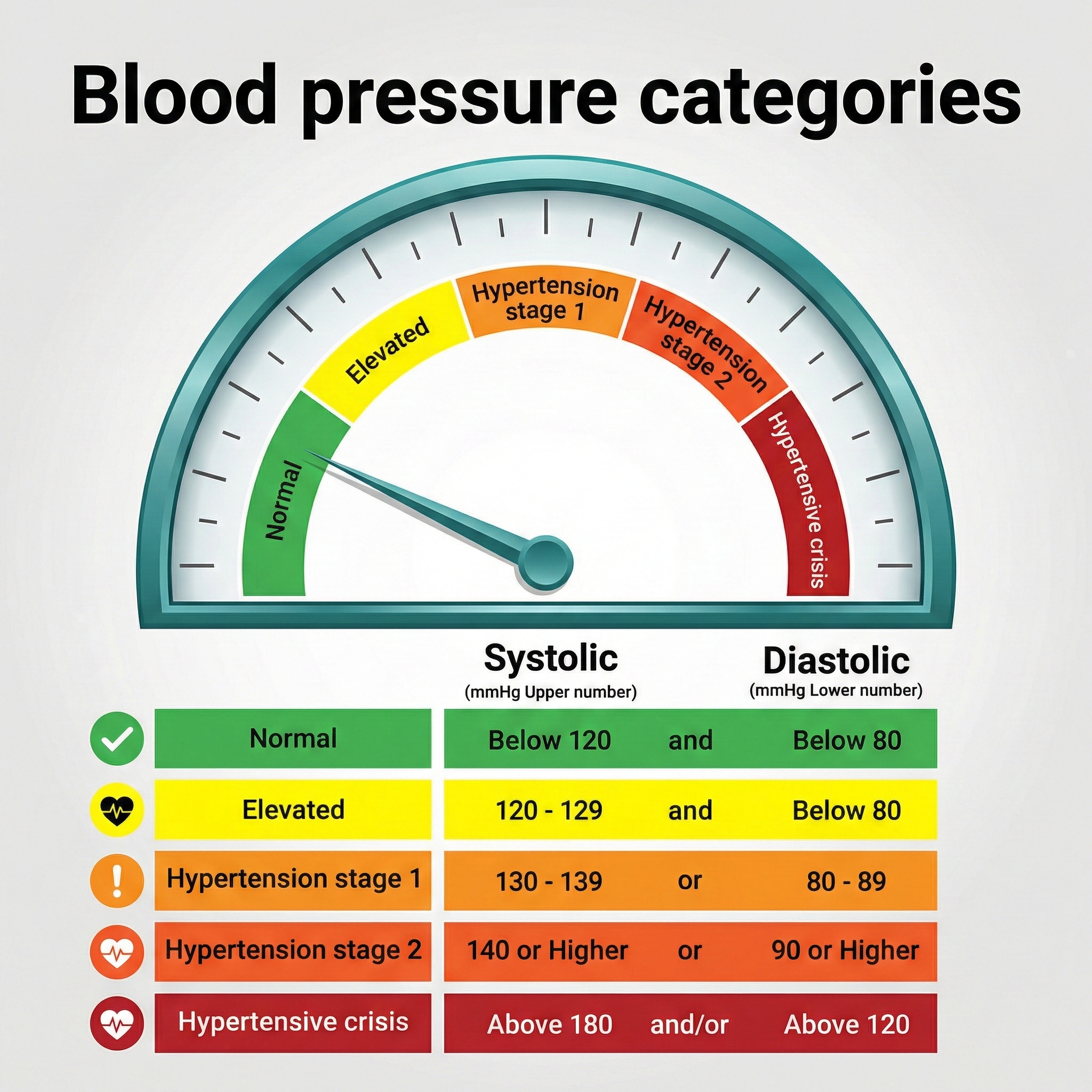

Part of what drove those dismal numbers was a major 2017 guideline change: normal blood pressure is now defined as below 120/80 mmHg, down from the previous threshold of 140/90 mmHg. That single diagnostic shift instantly expanded the population eligible for behavioral and medical intervention by tens of millions of people.

Biofeedback has proven both effective and cost-efficient for cardiovascular disorders, especially essential hypertension. Decades of research have revealed which intervention components actually work and have even produced models that can predict who will respond best to treatment and how much their blood pressure will drop.

A landmark 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis by Lehrer and colleagues examined 58 randomized controlled trials of HRV biofeedback across a wide range of conditions. The verdict? Small-to-moderate effect sizes favoring HRV biofeedback for both cardiovascular and psychological outcomes, with particularly robust effects for anxiety, depression, and anger regulation (Lehrer et al., 2020).

For many clients, the most evidence-supported cardiovascular interventions include weight loss, stress management training, and surface electromyographic (SEMG) and temperature biofeedback, often used in combination.

The way clinicians think about treating cardiovascular disorders is undergoing a fundamental shift. The old model focused almost exclusively on calming down an overactive sympathetic nervous system, as if the only problem were a car with a stuck accelerator. The newer model recognizes that many cardiovascular patients also have "bad brakes," meaning their parasympathetic system is not providing enough counterbalance.

Instead of just reducing sympathetic overdrive, clinicians now increasingly explore interventions that boost vagal tone (the strength of the parasympathetic influence on the heart) and increase heart rate variability. This dual approach, addressing both the accelerator and the brakes, represents a more complete strategy for restoring cardiovascular balance.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Cardiovascular Interventions Overview

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses the Pathophysiology, biofeedback modalities, and treatment protocols for specific ANS biofeedback applications (V-D). You will learn about essential hypertension, vasovagal syncope, heart failure and coronary artery disease, and cardiac arrhythmias.

🎧 Listen to the Full Chapter Lecture

Evidence-Based Practice (4th ed.)

We have updated the efficacy ratings for clinical applications covered in AAPB's Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.).

Essential Hypertension: When Blood Pressure Stays Too High

Understanding How Blood Pressure Works

Before diving into what goes wrong in hypertension, you need to understand the basic physics of blood pressure. Think of your cardiovascular system as a sophisticated plumbing network with a pump (your heart) pushing fluid (blood) through a complex system of pipes (blood vessels). Blood pressure (BP) is determined by two main factors: how hard the pump is working and how much the pipes resist the flow.

In physiological terms, BP equals the product of cardiac output (the amount of blood the heart pumps each minute) multiplied by systemic vascular resistance (how much the blood vessels resist blood flow). Systemic vascular resistance depends on three things: blood viscosity (how thick or "syrupy" the blood is), total blood vessel length, and most critically, the radius of the blood vessels.

Cardiac output is itself determined by two factors: stroke volume (how much blood the heart ejects with each beat) and stroke rate (how many times per minute the heart beats). Here is an everyday analogy: imagine a garden hose connected to an outdoor faucet. You can increase the water pressure coming out of the hose in two ways. You can turn up the faucet to push more water through (analogous to increasing cardiac output), or you can partially pinch the hose opening to create more resistance (analogous to increasing vascular resistance). Your cardiovascular system works the same way, but the "pinching" happens at thousands of tiny vessels throughout your body.

The real workhorses of blood pressure control are your arterioles, tiny arteries (8 to 50 microns in diameter, roughly the width of a human hair) scattered throughout your body. These small vessels are remarkably powerful regulators because of a principle from physics: resistance to flow increases exponentially as a tube's diameter decreases.

A seemingly minor adjustment in arteriole diameter can dramatically change systemic vascular resistance, which in turn shifts blood pressure and tissue perfusion (Tortora & Derrickson, 2021). This is why chronic tension in the smooth muscle lining these tiny vessels can lead to sustained high blood pressure, and why relaxation techniques that reduce that tension can be so effective.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Blood Pressure and Peripheral Resistance

What Counts as Hypertension?

The goalposts for what counts as "high blood pressure" moved significantly in 2017, and understanding those new thresholds matters for clinical practice. Stage 1 hypertension is now defined as a systolic BP (SBP, the top number when blood pressure is measured) of 130 mmHg or higher and/or a diastolic BP (DBP, the bottom number) of 80 mmHg or higher.

This redefinition by the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines (Whelton et al., 2017) was not just an academic exercise. Under the old 2003 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) guidelines, about 72 million Americans were classified as hypertensive. Under the 2017 guidelines, that number jumped to 103 million. In practical terms, 50% of American men and 38% of women now meet criteria for hypertension. If you are doing cardiovascular biofeedback, your potential client base just expanded dramatically.

Why did the guidelines change? The NIH Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) provided compelling evidence that lower is better, at least for high-risk patients. This landmark study found that treating hypertensive patients 50 years or older to a SBP target of 120 mmHg reduced cardiovascular events by 30% and all-cause mortality by nearly 25%, compared to the traditional target of 140 mmHg (Medscape, 2015). Those are substantial benefits that justify the more aggressive treatment thresholds.

However, the story is not as simple as "lower is always better." McEvoy and colleagues (2016) sounded an important warning: when aggressively lowering SBP below 140 mmHg, clinicians should not to let DBP fall below 70 mmHg, and especially not below 60 mmHg.

The danger is that very low diastolic pressure can threaten blood delivery to the heart itself, since the coronary arteries primarily fill during diastole (when the heart is relaxing). In their study, low DBP values were independently associated with progressive heart damage, coronary heart disease, and death.

The clinical takeaway? Aim for the sweet spot: low enough to protect against stroke and heart attack, but not so low that you starve the heart of blood.

Who Gets Hypertension?

Hypertension is so common that calling it an "epidemic" barely captures the scope. Nearly half of all American adults (47.7%) have hypertension, and the rates climb steeply with age: 23.4% of those aged 18-39, 52.5% of those 40-59, and a striking 71.6% of adults 60 and older (Fryar et al., 2024).

Men (50.8%) have slightly higher prevalence than women (44.6%), though this gap narrows after menopause. Racial disparities are substantial: Black Americans have the highest prevalence of any racial or ethnic group at approximately 46%, compared to 39% for White Americans (Fan et al., 2023; Siddiqui et al., 2024). People with diabetes face elevated rates as well.

Perhaps the most alarming statistic is the treatment gap: only about 21% of hypertensive adults have their blood pressure controlled below 130/80 mmHg (Fryar et al., 2024). Without lifestyle changes or drug intervention, patients with elevated BP frequently progress to full-blown hypertension (Huether et al., 2020). While elevated BP is often called a "silent killer" because it produces no obvious symptoms, some patients do experience signs like blurred vision and swelling ankles (edema).

Primary Versus Secondary Hypertension

When clinicians talk about hypertension, they distinguish between two fundamentally different categories. The vast majority, about 92 to 95% of all cases, are classified as primary hypertension (also called essential hypertension). Primary hypertension means chronically elevated BP that cannot be traced to any single identifiable cause (Huether et al., 2020). Instead, it emerges from a complex interplay of genetic predispositions, lifestyle factors, and physiological processes that we will explore shortly.

The remaining 5% of cases are classified as secondary hypertension, which means the elevated BP has a specific, identifiable cause like kidney disease, adrenal gland tumors, or obstructive sleep apnea (Huether et al., 2020). Secondary hypertension is important to identify because treating the underlying cause may resolve the high blood pressure entirely. For biofeedback practitioners, the key point is that primary hypertension, with its multiple contributing factors and no single "cure," is where behavioral interventions can make the biggest difference.

What Goes Wrong in Essential Hypertension?

Essential hypertension is not a single disease but rather a heterogeneous disorder, meaning different patients develop it through different pathways involving various combinations of genetic and environmental factors. What these pathways share is that they ultimately increase either circulating blood volume, peripheral vascular resistance, or both.

Current research increasingly points to autonomic dysregulation as a central driver in many patients. This dysregulation involves the sympathetic nervous system (your "fight or flight" branch) being chronically overactive while the parasympathetic system (your "rest and digest" branch) is underactive (Harrison et al., 2021). The sympathetic branch increases heart rate and cardiac contractility while constricting blood vessels, all of which raise blood pressure. Normally, parasympathetic activity counterbalances these effects, but in essential hypertension, that balance is disrupted. This insight has direct clinical implications: it explains why biofeedback interventions that restore parasympathetic tone can effectively lower blood pressure.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Primary Hypertension Mechanisms

Hypertension Symptoms

While elevated BP can be "silent," diverse symptoms like blurred vision and swelling ankles (edema) may accompany this chronic health condition.

Hypertension Complications

Researchers have reported that slight blood pressure elevations in middle age are associated with a 30% greater risk of dementia or cognitive impairment in two decades. Medication that lowers BP can reduce this risk (Hughes et al., 2020).

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Hypertension Symptoms

Three major mechanisms contribute to essential hypertension at the physiological level.

First, increased salt absorption leads to volume expansion, meaning more fluid in the blood vessels and higher pressure against vessel walls.

Second, an impaired response of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) disrupts normal blood pressure regulation.

The RAAS is a hormone system that acts like a thermostat for blood pressure and fluid balance. When activated, it triggers blood vessel constriction and signals the kidneys to retain sodium and water, both of which raise blood pressure. In essential hypertension, this system often remains chronically overactive even when blood pressure is already elevated.

Third, increased sympathetic nervous system activation directly raises heart rate and vascular resistance (Iqbal & Jamal, 2023).

Exciting new research also implicates the gut microbiome, the trillions of microorganisms living in your intestines, as a potential player. High-salt diets appear to alter the composition of gut bacteria in ways that promote inflammation and hypertension, opening a fascinating new avenue for future interventions (Wei et al., 2022).

Beyond physiology, demographic factors like age, gender, and ethnicity, along with psychological factors including depression, anger, and anxiety, all influence blood pressure (McGrady & Moss, 2013). Twin studies and the landmark Framingham Heart Study suggest that the heritable component of BP ranges from 33 to 57% (Madhur, 2014).

In other words, genes load the gun, but lifestyle pulls the trigger. This understanding of autonomic imbalance provides the scientific rationale for why biofeedback interventions that restore parasympathetic tone can effectively lower blood pressure in many patients.

Lifestyle Changes That Make a Difference

Before reaching for biofeedback equipment, it is worth noting that some of the most powerful blood pressure interventions involve no technology at all.

Potential SBP reductions from lifestyle changes vary by individual, but weight loss consistently emerges as the most effective lifestyle modification. This makes sense when you consider that obesity raises blood pressure through multiple pathways: it increases blood volume, promotes sympathetic activation, contributes to insulin resistance, and strains the heart.

Addressing obesity attacks the problem from several angles simultaneously.

Salt sensitivity is another important individual factor. About 60% of hypertensive patients and 25% of normotensive individuals are salt-sensitive, meaning their blood pressure rises significantly when they consume salt. Interestingly, biology is not uniform: 4 to 5% of individuals actually experience lower BP when they ingest salt (Harvard Heart Letter, August 2019).

Stress management deserves special mention because it represents a natural bridge to biofeedback. Chronic stress contributes to hypertension through sustained sympathetic activation and elevated cortisol, making relaxation training a logical complement to other lifestyle changes.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Steps to Reduce Hypertension

Drug Treatments for Hypertension

As a biofeedback practitioner, you will often work with clients already taking antihypertensive medications. Understanding how these drugs work helps you anticipate their effects on biofeedback measurements and coordinate care with prescribing physicians. The main drug classes target different parts of the blood pressure equation.

Diuretics (sometimes called "water pills") reduce blood volume by causing the kidneys to excrete more water and salt in urine, essentially reducing the amount of fluid the heart has to pump.

ACE inhibitors block the formation of angiotensin II, a powerful vasoconstrictor in the RAAS system. By blocking this hormone, ACE inhibitors cause blood vessels to relax (vasodilation, which reduces systemic vascular resistance) and reduce aldosterone secretion (which decreases sodium and water retention).

Beta-blockers work on the heart side of the equation: they inhibit renin secretion and decrease both heart rate and the force of cardiac contraction, reducing cardiac output.

Finally, calcium channel blockers slow the entry of calcium ions (Ca2+) into heart muscle cells and smooth muscle in blood vessel walls. Less calcium means weaker contractions, reducing both the heart's workload and vascular resistance.

A newer class of medications deserves attention from biofeedback practitioners: GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs). These drugs, originally developed for diabetes management, have demonstrated significant blood pressure-lowering effects.

GLP-1, or glucagon-like peptide-1, is a naturally occurring hormone released by intestinal cells after eating that regulates appetite, blood sugar, and cardiovascular function. GLP-1 receptor agonists mimic this hormone's effects. A 2024 individual patient data meta-analysis found that semaglutide, a commonly prescribed GLP-1 RA, reduces systolic blood pressure by approximately 4.8 mmHg, with much of this effect mediated through weight loss (Kennedy et al., 2024).

Tirzepatide, a newer dual-action medication that activates both GLP-1 and GIP receptors, produces even larger blood pressure reductions of 7 to 11 mmHg in patients with obesity (de Lemos et al., 2024). For biofeedback practitioners, these medications represent both an opportunity and a consideration: clients on GLP-1 RAs may show improved baseline blood pressure readings, and the combined effects of medication, weight loss, and biofeedback training could produce synergistic benefits.

A crucial clinical point: biofeedback interventions can interact synergistically with anti-hypertensive medication, sometimes producing larger BP reductions than either approach alone. This is generally good news, but it means patients must monitor their BP daily and discuss medication adjustments with their physician before making changes independently. The last thing you want is a client becoming hypotensive (blood pressure that is too low) because their combined interventions are working too well.

Richard's Journey: A Pathways Model Intervention

Richard, a 45-year-old mildly overweight Caucasian male, had been living with stage 1 hypertension for a decade. His blood pressure was well controlled using a combination of an ACE inhibitor and beta-blocker, but he wanted to reduce his dependence on medication. His treatment followed a tiered approach, starting with the least intensive interventions and adding components as needed.

His Level One interventions focused on self-monitoring and basic lifestyle adjustments: tracking his daily steps and gradually building up to 10,000 per day, logging his alcohol and food intake, weighing himself weekly, recording his morning BP readings, and taking a movement break every hour during work.

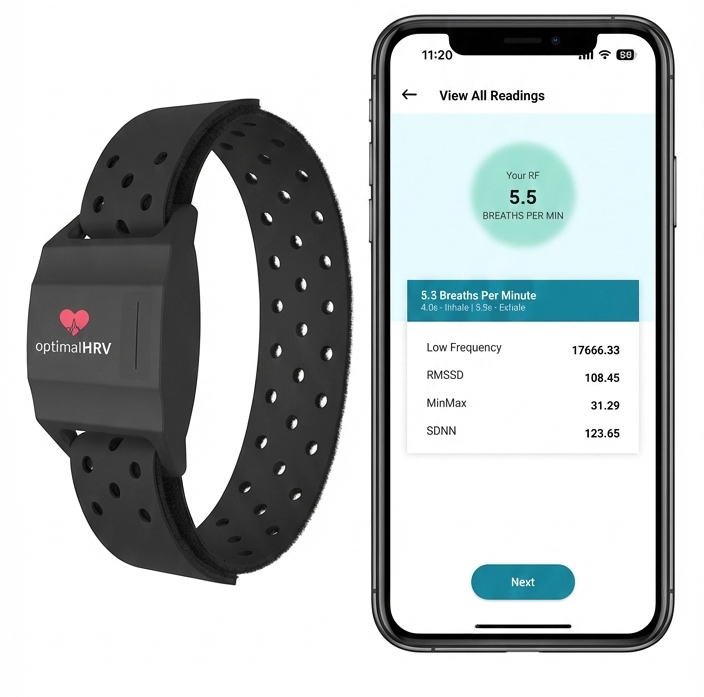

After one month without significant BP improvement, Richard moved to Level Two interventions that added skill-building components. He recruited an exercise partner to walk with him for at least 35 minutes five times per week (leveraging social support to boost motivation) and began practicing slow abdominal breathing using the Optimal HRV smartphone application. He also added a new Level One intervention: listening to classical music for at least 30 minutes daily at home.

Two months in, his blood pressure was gradually declining, but his weight remained stubbornly stable. Richard added another Level One intervention by using an activity tracker to monitor his sleep and adjusted his work schedule to ensure 8 hours nightly. His single Level Three intervention involved consulting twice with a licensed dietician to overhaul his eating patterns. The dietician guided him toward a DASH diet, reducing saturated fats and simple carbohydrates.

By the 6-month mark, the results were impressive: improved diet, better sleep, more energy, and blood pressure trending toward normal. His physician encouraged him to discontinue the beta-blocker and halve his ACE inhibitor dosage while continuing daily BP monitoring. At the end of 6 months, Richard's BP had fallen to the normotensive range, his blood lipids were normal, and he had lost 15 pounds. At one-year follow-up, his BP remained well controlled on reduced medication. He had regained about half the lost weight, but his sleep quality remained excellent and his DASH diet was now a habit.

Richard's case illustrates several key principles. First, biofeedback success often depends on the foundation provided by Level One and Level Two interventions; the HRV biofeedback training was not a magic bullet but one component of a comprehensive program. Second, self-monitoring of BP, diet, activity, sleep, and weight helped him develop the mindfulness needed to sustain behavior change. Third, social support matters: having an exercise partner made him more likely to actually exercise. Finally, he ensured safety by partnering with his physician to taper medication gradually rather than making changes on his own.

Six Factors That Predict Successful Blood Pressure Reduction

Not all hypertension treatment programs are created equal. In a landmark analysis, McGrady (1996) identified six specific factors that separated the efficacy studies reporting the largest and most consistent BP reductions from less successful attempts. These factors serve as a practical checklist when designing interventions.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Six Evidence-Based Factors for Blood Pressure Reduction

Who Responds Best to Biofeedback?

Biofeedback works better for some hypertensive patients than others, and research has identified predictors of treatment response. McGrady and Higgins (1989) and Weaver and McGrady (1995) studied unmedicated white adult males with mild to moderate hypertension who received a comprehensive treatment package: SEMG and temperature biofeedback, autogenic training, home practice, and BP monitoring.

The patients who showed the greatest response shared a physiological profile suggesting chronic sympathetic overactivation: elevated resting heart rate, cool hands (indicating peripheral vasoconstriction), high SEMG readings (reflecting muscle tension), and elevated plasma renin activity (a marker of RAAS activation).

The best predictors of how much BP actually decreased were high heart rate, cool hands, high trait anxiety, and high-normal cortisol. These findings make intuitive sense: patients whose hypertension is driven primarily by sympathetic overactivation are the ones most likely to benefit from interventions that reduce that activation.

A multi-modal strategy that combines biofeedback, relaxation training, and medical management appears most effective for patients whose BP shows marked reactivity to stressors (Frank et al., 2010). If a patient's blood pressure spikes when they are stressed but normalizes when they are calm, they are likely a good candidate for biofeedback intervention.

Multiple Pathways to Lower Blood Pressure

Because BP is determined by multiple factors (cardiac output, vascular resistance, blood volume), patients can lower their blood pressure through several different biological pathways. This is actually good news clinically: if one pathway is not available or responsive in a particular patient, others may still be trainable.

The main pathways include reducing cardiac output, lowering stress hormones like cortisol and norepinephrine, decreasing skeletal muscle tension (which affects vascular resistance), reducing systemic vascular resistance directly through vasodilation, and stimulating the baroreflex (a feedback loop that senses BP changes and adjusts heart rate accordingly).

Different biofeedback modalities appear to work through different mechanisms. Temperature biofeedback, which trains patients to warm their hands by dilating peripheral blood vessels, may reduce systemic vascular resistance and decrease plasma norepinephrine levels (McCoy et al., 1988).

Relaxation training appears to reduce cardiac output (Gervino & Veazey, 1984), while deep muscle relaxation may lower both cardiac output and plasma norepinephrine. The multi-modal therapy used by McGrady and colleagues, combining multiple biofeedback modalities with relaxation techniques, reduced plasma cortisol levels (McGrady et al., 1987), suggesting stress hormone reduction as another active mechanism.

Aerobic exercise represents another powerful, evidence-based pathway for blood pressure reduction that complements biofeedback training. A 2024 dose-response meta-analysis of 34 trials found that aerobic exercise reduces blood pressure in a dose-dependent manner, with the greatest reductions occurring at 150 minutes per week, producing SBP decreases of 7.2 mmHg and DBP decreases of 5.6 mmHg (Jabbarzadeh Ganjeh et al., 2024).

A comprehensive 2023 network meta-analysis of 270 randomized controlled trials found that isometric exercise training, surprisingly, produces the largest blood pressure reductions of all exercise modalities, with SBP decreases of 8.2 mmHg and DBP decreases of 4.0 mmHg (Edwards et al., 2023). These findings suggest that combining biofeedback with structured exercise programs may produce additive blood pressure benefits, particularly when exercise prescriptions are individualized based on patient preferences and capabilities.

One particularly interesting pathway involves the baroreflex. Gevirtz (2005) observed that when individuals breathe at their resonance frequency (typically around 6 breaths per minute), heart rate and blood pressure become synchronized but 180 degrees out of phase, meaning heart rate peaks when BP is lowest and vice versa. This breathing pattern appears to stimulate and strengthen the baroreflex. He proposed that resonance frequency biofeedback may lower BP precisely by enhancing this built-in pressure regulation system.

How to Measure Your HRV

As biofeedback practitioners increasingly use heart rate variability to assess autonomic function and guide treatment, teaching clients how to measure their HRV accurately at home has become a critical clinical skill. Unlike a single blood pressure reading that captures a snapshot in time, HRV tells a more nuanced story about how your autonomic nervous system is adapting to life's demands. But here is the catch: HRV is exquisitely sensitive to how, when, and under what conditions you measure it. Get the protocol wrong, and you will be chasing noise rather than signal.

Why Measurement Consistency Matters

HRV fluctuates throughout the day based on countless factors: circadian rhythms, core body temperature, metabolism, sleep cycles, and the renin-angiotensin system all contribute to these natural variations (Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). The gold standard for clinical HRV assessment remains the 24-hour recording, which captures this full range of physiological variation (Task Force, 1996). However, for practical home monitoring, shorter recordings work well when collected under standardized conditions.

The European Society of Cardiology and North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology established that short-term 5-minute recordings provide reliable data for most clinical applications (Task Force, 1996).

More recently, research has shown that even ultra-short recordings of 1 minute can yield valid RMSSD values when using appropriate protocols (Esco & Flatt, 2014).

The key principle is consistency. Whatever protocol you choose, stick with it. Comparing a measurement taken lying in bed right after waking to one taken standing after coffee is comparing apples to oranges, and the difference will tell you nothing useful about your actual autonomic state.

When to Measure: Optimal Timing

Morning measurements, taken immediately after waking while still in a rested state, have emerged as the gold standard for practical HRV monitoring. This timing captures your baseline autonomic function before the day's stressors have influenced your physiology. Research with athletes and healthy populations consistently shows that morning HRV measurements provide the most sensitive indicator of recovery status and response to training loads (Plews et al., 2013). The morning routine works because you can replicate it daily in essentially the same physiological state: rested, fasted, and before engaging with the demands of the day.

Nocturnal HRV monitoring offers an alternative approach that many wearable devices now support. By averaging HRV across a sleep period, nocturnal recordings capture autonomic function during the body's natural recovery phase. Both morning and nighttime measurements are valid approaches, but once you pick a protocol, maintain consistency over time (Plews et al., 2014).

The Standard Protocol: Four Essential Steps

Whether you are measuring a client in the clinic or teaching them to measure at home, follow this four-step protocol for reliable results:

Step 1: Use the bathroom first. A full bladder activates the sympathetic nervous system, which will artificially lower your HRV reading. This mirrors the blood pressure measurement principle that a full bladder can increase readings by 10 to 15 mmHg (Muntner et al., 2019).

Step 2: Sit up straight. Body position profoundly affects HRV measurements. In the supine (lying down) position, the cardiovascular system experiences minimal gravitational stress, generally resulting in higher parasympathetic activity. Moving to seated or standing positions requires orthostatic adaptation and typically increases sympathetic outflow to maintain blood pressure (Buchheit, 2014).

The seated position represents an excellent compromise: it provides enough physiological challenge to detect meaningful changes while remaining comfortable and practical for daily use. Research shows moderate to good reproducibility for time-domain HRV metrics like RMSSD in both supine and seated positions, with ICCs ranging from 0.65 to 0.89 (Dantas et al., 2019). Most importantly, whichever position you choose, use it consistently.

Step 3: Measure for at least 1 minute. While the traditional standard recommends 5-minute recordings (Task Force, 1996), research has validated that RMSSD can be accurately measured in as little as 60 seconds when following proper protocols (Esco & Flatt, 2014; Nussinovitch et al., 2011). For other HRV metrics like SDNN or frequency-domain measures, longer recordings of 2 to 5 minutes may be needed (Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017). If your app or device specifies a particular duration, follow its recommendations.

Step 4: Breathe normally. Do not try to slow your breathing or control it in any special way during measurement unless your device specifically instructs otherwise. Natural, uncontrolled breathing allows the recording to capture your genuine resting autonomic state. Controlled breathing during measurement will shift your HRV values and make day-to-day comparisons meaningless.

Choosing Your Sensor: ECG vs. PPG

Two main technologies dominate consumer HRV measurement: electrocardiography (ECG) and photoplethysmography (PPG). Understanding the difference helps you choose the right tool and interpret results appropriately.

ECG-based devices, including chest straps like the Polar H10, detect the heart's electrical activity directly. They measure the precise timing between R-waves in the ECG signal, providing gold-standard accuracy for HRV analysis. Validation studies consistently show excellent agreement between chest strap ECG devices and clinical multi-lead ECG systems, with correlations often exceeding 0.99 (Gilgen-Ammann et al., 2019). For biofeedback practitioners requiring research-grade accuracy, ECG chest straps remain the preferred option.

PPG-based devices, found in smartwatches, fitness bands, and smart rings, use optical sensors to detect blood volume changes in peripheral circulation. While convenient, PPG does not directly measure the heart's electrical activity. PPG estimates HRV from pulse rate variability (PRV), the variation in pulse arrival times at the wrist or finger (Charlton et al., 2025).

Research shows that PPG-derived HRV correlates well with ECG-derived HRV during rest and stationary conditions, but accuracy declines progressively during movement and physical activity (Georgiou et al., 2018). Time-domain variables like RMSSD show acceptable agreement with ECG in resting conditions, while frequency-domain parameters exhibit lower reliability (Morelli et al., 2025).

Interpreting Your Results: The Normal Range

Perhaps the most important thing to understand about HRV is that it is profoundly individual. Population averages exist, but they are less useful than tracking your own personal baseline over time. RMSSD values in healthy adults typically range from 19 to 107 ms, though published ranges vary considerably across studies based on age, fitness level, and measurement conditions (Nunan et al., 2010).

Younger individuals and athletes generally show higher HRV values than older or sedentary populations. HRV also declines with age as autonomic function naturally attenuates (Task Force, 1996; Dantas et al., 2024).

Rather than comparing yourself to population norms, focus on establishing your personal baseline over 1 to 2 weeks of consistent daily measurements. Once you have a baseline, you can interpret deviations meaningfully. A reading within your normal range generally signals adequate recovery and readiness for physical or mental demands. A reading significantly below your normal range may indicate incomplete recovery, elevated stress, illness onset, or overtraining in athletes (Plews et al., 2013).

When NOT to Measure Your HRV

Just as certain conditions invalidate blood pressure readings, specific circumstances will produce misleading HRV values that should not be compared to your baseline:

After alcohol consumption. Acute alcohol intake produces dose-dependent reductions in parasympathetic HRV. A large Finnish study of over 4,000 individuals found that high alcohol intake decreased RMSSD by an average of 12.9 ms during the first hours of sleep, while also reducing recovery time by nearly 40 percentage points (Pietila et al., 2018).

Even moderate drinking reduces HRV, with one study finding that Oura ring users showed a mean decrease of 10.8 milliseconds (about 15.6%) on nights after drinking alcohol. The effects can persist for 4 to 5 days following heavy consumption, making post-drinking HRV measurements unreliable indicators of true autonomic function.

After caffeine consumption. While caffeine's effects on HRV are more complex than alcohol's, most research shows that caffeine stimulates the autonomic nervous system and can alter both time-domain and frequency-domain HRV metrics (Koenig et al., 2013). Morning measurements should occur before your first cup of coffee. If you must consume caffeine, wait at least 30 minutes and ideally several hours before measuring.

After late exercise. Intense exercise significantly affects HRV for hours afterward as your body recovers. Evening workouts will still influence your next morning's HRV reading. A quantitative analysis found that parasympathetic reactivation following exercise depends on intensity, duration, and fitness level, with full recovery sometimes requiring extended periods (Dantas et al., 2024).

For the most stable baseline readings, avoid strenuous exercise within 24 hours of measurement when possible, or at least maintain consistent exercise timing relative to your HRV measurements.

After large meals. Digestion activates the autonomic nervous system and diverts blood flow to the gastrointestinal tract. Measuring HRV immediately after eating will not reflect your true resting autonomic state. Wait at least 2 hours after a substantial meal.

During acute illness or stress. While HRV can detect illness and stress, measurements taken during these periods should be interpreted cautiously rather than compared to your healthy baseline. Your immune system's activation during illness naturally suppresses HRV as part of the inflammatory response.

Choosing a Home Monitor

For clients interested in daily HRV tracking, several categories of devices merit consideration. ECG chest straps like the Polar H10 or Garmin HRM-Pro offer research-grade accuracy at relatively low cost, but require putting on a strap each morning.

Smart rings like the Oura Ring provide overnight HRV tracking with minimal inconvenience but use PPG technology. Smartwatches from manufacturers like Apple, Garmin, and Fitbit can measure HRV through either PPG (continuous) or ECG (on-demand spot checks on some models).

Validation studies have found wide variation in consumer device accuracy. Research comparing popular devices to clinical ECG found that ECG-based apps like HRV4Training achieved the highest accuracy (mean absolute percentage error below 7%), while camera-based smartphone apps showed the poorest performance (Stone et al., 2021). Encourage clients to choose devices with published validation studies and to interpret trends rather than individual readings.

Key Takeaways for HRV Measurement

Accurate HRV measurement requires consistency above all else. Measure at the same time daily, ideally first thing in the morning before getting out of bed or consuming anything. Use the bathroom first, sit up straight, measure for at least 60 seconds, and breathe normally without trying to control your breath.

Choose one sensor type and stick with it. Avoid measuring after alcohol, caffeine, intense exercise, or large meals. Interpret your readings against your own personal baseline rather than population averages. A reading within your normal range signals good recovery; a reading significantly below baseline may indicate stress, incomplete recovery, or early illness. Track trends over weeks rather than reacting to single measurements.

Check Your Understanding

- Why is consistency in HRV measurement protocol more important than achieving any single "correct" method?

- What four steps comprise the standard protocol for morning HRV measurement?

- How do ECG-based and PPG-based HRV monitors differ in what they actually measure, and when might each be preferred?

- Explain why alcohol consumption affects HRV and how long these effects may persist after drinking.

Watch Out for Medication Effects

Prescription medications and social drugs can significantly affect biofeedback measurements, potentially masking problems or creating misleading baselines. A savvy clinician needs to know what their client is taking and how it might influence readings.

Inderal (propranolol), a beta-blocker, produces peripheral vasodilation that can artificially warm the hands. A patient on Inderal might show a seemingly healthy hand temperature of 92 degrees F (33.3 degrees C) when their true baseline without medication might be a cool 88 degrees F (31.1 degrees C).

The practical implication? When medication artificially raises hand temperature, set a higher training target; the client has more room to improve than their initial reading suggests.

Caffeine presents the opposite challenge. Medications containing caffeine (such as Cafergot and Fiorinal, used for headaches) or caffeine-containing beverages like coffee and energy drinks can increase heart rate and constrict peripheral blood vessels. These effects directly oppose what most cardiovascular biofeedback protocols are trying to achieve. If a client is loading up on caffeine before sessions, they are essentially fighting their own training. The clinician should consult with the patient's physician about gradually eliminating or restricting caffeine intake during the treatment period.

Nicotine may be the most problematic substance for cardiovascular biofeedback. Nicotine raises heart rate and is a potent vasoconstrictor, meaning it directly counteracts efforts to lower blood pressure. For patients who smoke or use nicotine products, smoking cessation treatment should be considered as part of, or prior to, biofeedback intervention. Without addressing nicotine use, other interventions may be swimming upstream.

Designing Your Client's Treatment Program

When designing a treatment program for essential hypertension, McGrady's (1996) six factors should serve as your foundation. But effective treatment also requires individualization based on thorough medical and behavioral assessment. Biofeedback for hypertension should never be attempted as a standalone intervention without a recent medical workup and ongoing communication with the patient's physician. This is not just good practice; it is essential for patient safety. Blood pressure changes during treatment can necessitate medication adjustments, and only the prescribing physician can make those calls. Medical oversight is particularly critical when a client's BP begins dropping significantly, as medication doses may need to be reduced to prevent hypotension.

After medical clearance, conduct a psychophysiological profile to identify which response systems are dysregulated and need training. Does the client show elevated frontalis EMG suggesting chronic muscle tension? Cool peripheral temperature indicating vasoconstriction? Poor HRV suggesting autonomic imbalance? The answers guide which modalities to include.

A multi-modal strategy that retrains the specific systems showing dysregulation, promotes relevant lifestyle changes (like exercise, diet modification, and sleep improvement), and teaches stress management when indicated shows the most clinical promise. One-size-fits-all approaches are rarely optimal.

What the Research Shows

The evidence base for biofeedback in hypertension has grown substantially, with recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses providing increasingly compelling support. Vital and colleagues (2021) analyzed nine randomized controlled trials involving 462 participants and found that biofeedback significantly improved diastolic blood pressure control compared to control conditions. Notably, interventions that combined biofeedback with complementary elements like relaxing music, breathing exercises, and muscle relaxation produced the greatest blood pressure reductions, supporting the multi-modal approach discussed earlier.

An even more comprehensive 2024 meta-analysis by Jenkins and colleagues examined 20 RCTs and found clinically meaningful reductions in both systolic (4.52 mmHg) and diastolic blood pressure (5.19 mmHg) following biofeedback interventions (Jenkins et al., 2024). Six different biofeedback modalities were represented across these studies, with HRV biofeedback being the most commonly used approach.

Earlier meta-analyses laid the groundwork for these findings. Yucha and colleagues (2001) compared biofeedback training against active comparison treatments like meditation and found that biofeedback achieved greater reductions in both SBP (6.7 mmHg) and DBP (3.8 mmHg) than inactive control treatments.

Another important finding: thermal and electrodermal biofeedback appear to outperform direct BP biofeedback (Linden & Moseley, 2006). This is a somewhat counterintuitive finding, but it makes sense when you consider that peripheral temperature and skin conductance provide more immediate, controllable feedback than BP readings, which fluctuate considerably and are harder to learn to control directly.

Wang and colleagues (2010) conducted an RCT specifically with prehypertensive post-menopausal women, a population at high risk for progression to full hypertension. They compared slow abdominal breathing combined with frontal SEMG biofeedback against breathing training alone.

The combined SEMG biofeedback group showed impressive results: SBP dropped 8.4 mmHg and DBP dropped 3.9 mmHg, compared to only 4.3 mmHg SBP reduction in the control group. Training participants to breathe at approximately six breaths per minute with daily home practice enhanced outcomes, consistent with Gevirtz's work on resonance frequency breathing.

Clinical Efficacy Rating

Based on three RCTs for essential hypertension and five for pre-hypertension treatments, Angele McGrady (2023) rated biofeedback for essential hypertension as level 4: efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). This is a meaningful rating; level 4 requires that the treatment be superior to a no-treatment control group, a wait-list, or a credible placebo in at least two independent research settings.

The biofeedback interventions studied trained participants to lower electrodermal and SEMG activity and SBP, and to increase HRV. The outcomes included reductions in both DBP and SBP, along with increased baroreflex sensitivity (BRS). Think of BRS as a measure of how "tuned up" your blood pressure regulation system is: if the baroreflex responds strongly to a small BP change, BRS is high, meaning the system is working efficiently. Low BRS means the system responds sluggishly, allowing BP to drift higher without appropriate correction. Biofeedback appears to improve this regulatory sensitivity.

Weight loss remains the single most effective lifestyle change for reducing blood pressure because obesity contributes to hypertension through multiple pathways simultaneously. McGrady's six factors provide a blueprint for successful interventions: biofeedback for hand warming and frontalis EMG reduction, autogenic training, consistent home practice, progressive muscle relaxation, and relaxation recordings.

The best candidates for biofeedback treatment show physiological signs of sympathetic overactivation: elevated resting heart rate, cool hands, high anxiety levels, and high-normal cortisol. A multi-modal strategy that combines biofeedback with relaxation training and medical management produces the best outcomes, particularly for patients whose blood pressure is stress-reactive.

Different biofeedback modalities work through different mechanisms: temperature biofeedback appears to reduce systemic vascular resistance by promoting peripheral vasodilation, while resonance frequency breathing at approximately 6 breaths per minute may lower blood pressure by stimulating and strengthening the baroreflex. Understanding these multiple pathways allows clinicians to tailor interventions to individual patient profiles.

Check Your Understanding

- What are the two primary factors that determine blood pressure, and how does each contribute to hypertension?

- Why might a client with cool hands and high heart rate be an especially good candidate for biofeedback treatment of hypertension?

- How do the mechanisms of temperature biofeedback and resonance frequency breathing differ in lowering blood pressure?

- What precautions should a biofeedback practitioner take when working with a client taking beta-blockers like Inderal?

- Why is a multi-modal treatment strategy recommended over single-modality approaches for essential hypertension?

How to Measure Your Blood Pressure

Accurate blood pressure measurement is essential for diagnosing and managing hypertension (Muntner et al., 2019). A single 5 mmHg error can misclassify millions of people (Stergiou et al., 2021), and when multiple errors stack up, readings can run 20 to 30 mmHg higher than true blood pressure. The good news: most errors are preventable.

Preparation and Positioning

Avoid caffeine, exercise, and smoking for at least 30 minutes before measurement (Jones et al., 2025). Empty the bladder, then sit quietly for 5 minutes in a chair with back support, feet flat on the floor, legs uncrossed. Support the arm on a flat surface with the cuff at heart level. Place the cuff on bare skin or over only a thin sleeve.

Cuff size is the most common source of error. The inflatable bladder should encircle at least 80% of arm circumference (Muntner et al., 2019). A too-small cuff produces falsely elevated readings; one study found nearly 20 mmHg overestimation when a regular cuff was used on someone needing an extra-large (Juraschek et al., 2023). Over 17 million American adults have arm circumferences outside the 22 to 42 cm range of standard home monitor cuffs (Matsushita et al., 2024).

Taking and Timing Measurements

Use a validated oscillometric device (check validatebp.org); avoid wrist and finger monitors (Muntner et al., 2019). Remain silent during measurement, as conversation can raise systolic BP by 10 to 19 mmHg (Long et al., 1982). Take at least two readings one to two minutes apart and average them; discard the first reading if substantially higher (Jones et al., 2025).

For home monitoring, measure twice daily: morning (after waking and emptying the bladder, before medications or breakfast) and evening (before bed). Take two readings at each session. Continue for 3 to 7 days when establishing a baseline (Shimbo et al., 2020). Avoid measuring during acute illness, unusual stress, or immediately after large meals.

Home Versus Office Measurement

Home measurements eliminate white-coat effects, which cause 25 to 30% of patients with elevated office readings to show normal BP at home (Mancia et al., 2006). Home BP better predicts cardiovascular outcomes than office readings (Shimbo et al., 2020). However, masked hypertension, where BP appears normal at home but runs elevated during daily activities, affects 10 to 15% of the population and carries similar cardiovascular risk to sustained hypertension. Some clients benefit from 24-hour ambulatory monitoring to capture both patterns.

Check Your Understanding

- A client's blood pressure reading is 148/92 mmHg. You notice they are using a standard cuff despite having a large arm circumference, their legs are crossed, and they were talking to you during the measurement. Approximately how much might these errors have inflated the systolic reading?

- Why is home blood pressure monitoring considered superior to office measurement for predicting cardiovascular outcomes?

- What is the difference between white-coat hypertension and masked hypertension, and why does each matter clinically?

Vasovagal Syncope: When the Vagus Nerve Goes Too Far

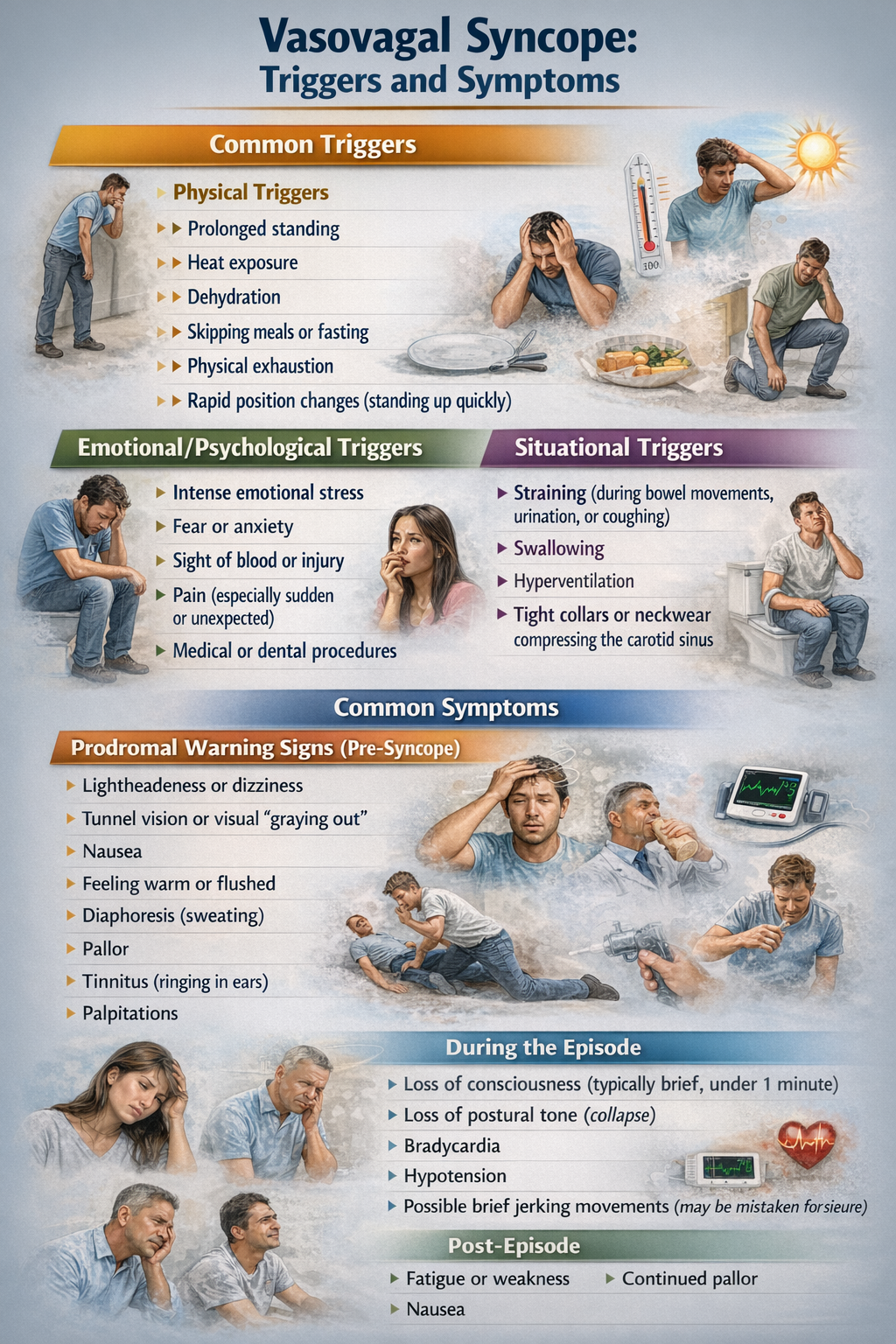

Hypertension involves too little vagal influence on the heart. Now we turn to a condition where the problem is too much vagal activity at the wrong time. Syncope is the medical term for a temporary loss of consciousness, what most people call fainting. Vasovagal syncope (VVS), also called neurocardiogenic syncope, is a specific type featuring a brief loss of consciousness that typically occurs while standing. It is the classic "fainting spell" that might happen when someone sees blood, stands too long in a hot room, or experiences sudden emotional stress.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Vasovagal Syncope Triggers and Symptoms

Here is what happens physiologically: during a stressful event, the vagus nerve (the main parasympathetic pathway to the heart) becomes dramatically overactive. This surge of vagal activity slows the heart rate and dilates blood vessels, causing cardiac output to drop and blood to pool in the legs and lower body. With less blood reaching the brain, the person becomes light-headed and may lose consciousness entirely.

It is essentially the opposite problem from hypertension: instead of the sympathetic system being chronically overactive, the parasympathetic system overreacts acutely. The episode typically resolves quickly once the person lies down or falls, which allows blood to flow more easily back to the brain.

Who Experiences Vasovagal Syncope?

If you have ever fainted or come close, you are far from alone. Vasovagal syncope is remarkably common. A recent global meta-analysis pooling data from 36,156 individuals estimated the worldwide prevalence at approximately 16.4% (Salari et al., 2024). That means roughly one in six people will experience at least one VVS episode in their lifetime.

Women are disproportionately affected, with some studies finding prevalence rates more than twice as high in females compared to males (Tajdini et al., 2023).

Classic vasovagal syncope typically first appears during adolescence, with the most common age of onset around 13 years, though episodes can begin at any age. By the time people reach middle age, about 35% of those between 35 and 60 years have experienced at least one episode of syncope.

From a healthcare system perspective, syncope accounts for 1 to 3% of emergency room visits and 6% of hospital admissions each year (Morag, 2015). While most episodes are benign and self-limiting, the potential for injury during a fall and the anxiety surrounding unpredictable episodes make this condition worth treating.

Biofeedback Research for Vasovagal Syncope

You might wonder: if VVS involves excessive parasympathetic activity, why would relaxation techniques that increase parasympathetic tone help? The answer lies in improving overall autonomic regulation rather than simply shifting the balance in one direction. Biofeedback-assisted relaxation therapy (BART) has been used to treat VVS, typically combining SEMG and thermal biofeedback with autogenic training and progressive relaxation.

The goal is not to further increase vagal tone but to help patients develop better overall autonomic flexibility and to reduce the stress and anxiety that often trigger VVS episodes in the first place.

McGrady, Bush, and Grubb (1997) reported a case series of 10 consecutive VVS patients who received comprehensive treatment: EMG and temperature biofeedback, diaphragmatic breathing instruction, and both autogenic training and progressive relaxation. Patients received an average of 8.5 fifty-minute training sessions. The results were encouraging: by the end of training, 6 of 7 patients diagnosed with syncope had reduced their episodes by at least 50%, and half of all patients reported improvement on each of their symptoms.

McGrady et al. (2003) followed up with a more rigorous test of BART for VVS. Subjects were evaluated during a 2-week pretest period, then randomly assigned to either treatment or a wait-list control condition. The treatment consisted of 10 fifty-minute sessions incorporating SEMG and thermal biofeedback, autogenic and progressive relaxation training, and guidance on applying techniques like progressive relaxation to their specific symptoms. Patients practiced at home using provided scripts and audiotapes for 10 to 15 minutes twice daily.

The results showed that the BART group achieved greater reductions in both headache index and loss of consciousness than the wait-list control group. Both groups improved on measures of state anxiety and depression, but the BART group showed superior outcomes on the primary VVS symptoms.

Clinical Efficacy Rating

Based on one RCT, Fred Shaffer (2023) rated biofeedback for vasovagal syncope as level 2: possibly efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (4th ed.). This relatively modest rating reflects the limited number of studies and small sample sizes rather than negative findings. The existing research is promising, but more and larger RCTs are needed to establish biofeedback as a definitive treatment for VVS.

Vasovagal syncope affects approximately one in six people worldwide, with women experiencing episodes at more than twice the rate of men. The mechanism involves a paradoxical overactivation of the vagus nerve during stress, causing blood vessels to dilate and blood to pool in the lower body. With less blood reaching the brain, the person feels light-headed and may faint. BART protocols using SEMG and thermal biofeedback combined with autogenic and progressive relaxation training show promise for reducing syncope episodes by at least 50% in most treated patients.

The intervention works not by further increasing vagal tone but by improving overall autonomic regulation and reducing stress-related triggers.

Check Your Understanding

- What is the physiological sequence of events that causes loss of consciousness in vasovagal syncope, and how does it differ from the autonomic pattern seen in hypertension?

- Given that VVS involves excessive parasympathetic activity, why might relaxation training still be effective rather than making the problem worse?

- What specific components did McGrady et al. (2003) include in their BART protocol for VVS, and what outcomes did they measure?

Heart Failure and Coronary Artery Disease: Restoring Balance

Heart failure and coronary artery disease represent some of the most serious cardiovascular conditions, affecting millions and often limiting both quality and length of life. Can HRV biofeedback help these patients? An emerging body of research suggests it can, though the evidence is still developing.

🎧 Mini-Lecture: Heart Failure and Coronary Artery Disease

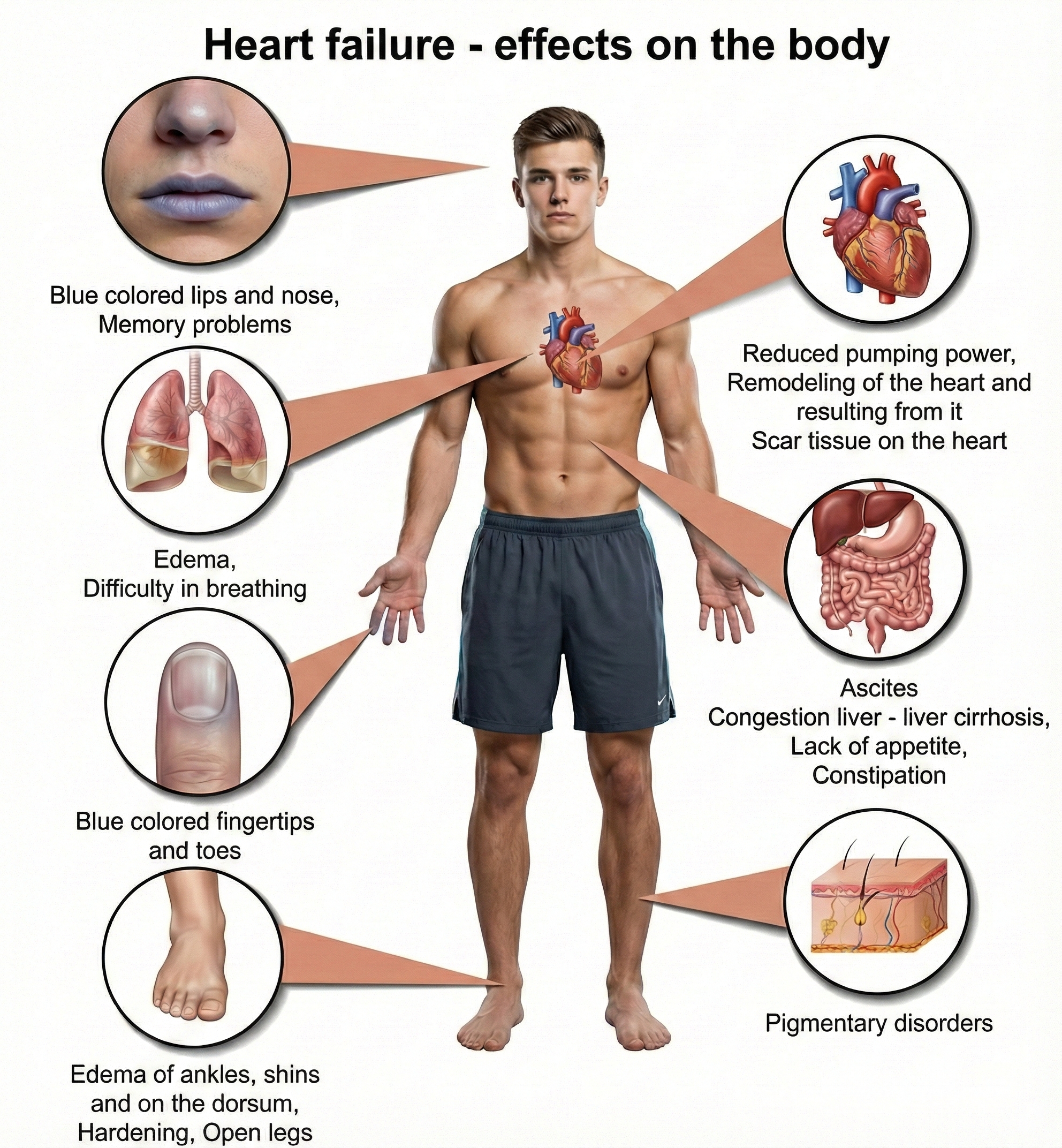

To understand why HRV biofeedback might help, you first need to understand these conditions. Heart failure occurs when one or both of the ventricles (the heart's lower chambers, which do the heavy lifting of pumping blood) cannot keep up with the body's demands. Either cardiac output becomes insufficient to properly perfuse (deliver blood to) the tissues, or the left ventricle cannot fill properly, causing pressure to back up into the lungs (Huether et al., 2020). When the left ventricle fails, blood backs up into the lungs, causing shortness of breath and fatigue. When the right ventricle fails, blood backs up into the body, causing fluid to accumulate in the legs (edema) and abdomen. Many patients eventually develop failure of both sides.

Here is where the story connects to biofeedback: a critical driver of heart failure progression is autonomic nervous system dysregulation (Beghini et al., 2024). In a healthy cardiovascular system, the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches work in dynamic balance, adjusting cardiac output moment-to-moment to match the body's needs. In heart failure, this balance breaks down. Patients develop sympathetic overdrive, meaning sustained overactivation of the fight-or-flight response even at rest, combined with parasympathetic withdrawal, a reduction in the calming vagal influence on the heart.

This autonomic imbalance is not just a symptom; it actively worsens the disease. Chronic sympathetic overdrive promotes adverse cardiac remodeling (structural changes to the heart muscle that reduce function) and metabolic dysfunction. Clinicians have long known that patients with the highest levels of neurohumoral activation, estimated by measuring plasma norepinephrine levels, have the worst prognosis. This understanding provides a strong rationale for HRV biofeedback: if you can restore autonomic balance, you may be able to slow or even partially reverse heart failure progression.

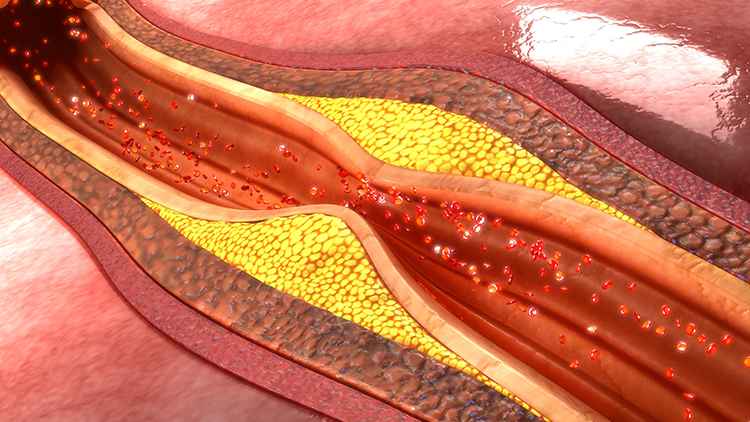

Coronary artery disease (CAD) involves a different but related problem: reduced blood flow through the coronary arteries that supply the heart muscle itself. The usual culprit is atheromas, deposits of lipid-containing plaques that build up on the inner walls of arteries, gradually narrowing the channel through which blood flows. As long as the narrowing is partial, the patient may have no symptoms at rest but experience chest pain (angina) during exertion when the heart needs more oxygen than the narrowed arteries can deliver.

The danger comes when an atheroma's fibrous outer layer ruptures. The body responds to this rupture as it would to any wound, initiating a clotting cascade that can form a thrombus (blood clot). If that clot completely blocks a coronary artery, the result is a myocardial infarction (MI), commonly called a heart attack, meaning death of heart muscle tissue downstream from the blockage. Like heart failure, CAD is associated with autonomic dysregulation, making HRV biofeedback a logical intervention target.

How Common Is Heart Failure?

Heart failure is alarmingly common and getting worse. Currently, about 6.7 million Americans over age 20 live with heart failure, and projections suggest this number will rise to 8.7 million by 2030 (Bozkurt et al., 2024). The lifetime risk, meaning the probability of developing the condition at some point during one's life, has increased to 24%. That means roughly 1 in 4 people will eventually develop heart failure.

Perhaps most concerning, the proportion of younger patients (ages 35-64) is increasing, and mortality rates have been rising since 2012 with a sharp acceleration during 2020-2021. Heart failure remains the leading cause of hospitalization for patients over 65. These statistics underscore the urgent need for effective interventions at all stages of the disease, from prevention to advanced heart failure management.

Biofeedback Research for Heart Failure and CAD

HRV biofeedback may improve cardiac function by restoring autonomic balance (Gevirtz, 2013). This represents a paradigm shift from the earlier model of simply reducing SNS activation to actively restoring balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic branches (Moravec & McKee, 2013). Decreased HRV is a significant independent risk factor for cardiac patient morbidity and mortality, making interventions that restore HRV clinically valuable.

Emerging evidence suggests that GLP-1 receptor agonists may complement biofeedback approaches in heart failure management. The landmark SELECT trial demonstrated that semaglutide reduced major adverse cardiovascular events by 20% in patients with obesity and established cardiovascular disease, with benefits extending to those with heart failure (Lincoff et al., 2023).

A prespecified analysis found that among patients with heart failure at enrollment, semaglutide reduced the composite heart failure endpoint by 21% compared to placebo, with benefits observed in both heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (Deanfield et al., 2024). The mechanisms underlying these benefits likely include weight reduction, blood pressure lowering, anti-inflammatory effects, and improved metabolic function, all of which address key pathways contributing to heart failure progression.

Exercise training also plays a crucial role in heart failure rehabilitation. A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis found that exercise training significantly improves peak oxygen consumption in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction by approximately 2.0 mL/kg/min, along with meaningful improvements in quality of life (Baral et al., 2024).

A 2025 multicenter randomized trial of 322 patients found that combined endurance and resistance training over 12 months produced clinically meaningful improvements, with 20.5% of exercising patients showing improvement on a composite outcome compared to only 8.1% of usual care controls (Edelmann et al., 2025). These findings support integrating structured exercise programs with HRV biofeedback training for heart failure patients.

Del Pozo, Gevirtz, Scher, and Guarneri (2004) randomly assigned 63 CAD patients to traditional cardiac rehabilitation or six biofeedback sessions including abdominal breathing training and cardiorespiratory biofeedback. The biofeedback group increased HRV from baseline (mean SDNN rose from 28 to 42 ms) while controls deteriorated, demonstrating that CAD patients can meaningfully increase HRV through training.

Lin and colleagues (2015) randomly assigned 154 CAD patients to HRV biofeedback plus standard care or standard care alone. The biofeedback group showed significantly increased low-frequency HRV and SDNN along with decreased hostility. A landmark 2018 follow-up tracked 210 patients for one year and found dramatically fewer hospital readmissions (12% versus 25%) and emergency visits (13% versus 36%) in the biofeedback group. These findings provide compelling evidence that HRV biofeedback may improve cardiovascular prognosis (Lin et al., 2018).

Swanson and colleagues (2009) found that HRV biofeedback increased exercise tolerance in heart failure patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 31% or higher, suggesting the intervention may be most beneficial for patients with moderately reduced cardiac function.

Clinical Efficacy Rating

Christine Moravec and Michael McKee (2016) initially rated biofeedback for heart failure and coronary artery disease as level 2: possibly efficacious in Evidence-Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback (3rd ed.). However, the field has advanced considerably since that rating. Subsequent RCTs by Lin and colleagues (2015, 2018) have substantially strengthened the evidence base, demonstrating not only short-term autonomic improvements but also meaningful one-year cardiovascular prognosis benefits including reduced hospitalizations and emergency visits. These newer findings suggest the evidence may now support a higher efficacy rating, though formal reassessment awaits future editions of the efficacy guidelines.

Heart failure affects 6.7 million Americans, with a lifetime risk of 24%, meaning roughly 1 in 4 people will develop this condition. The disease is driven in large part by autonomic dysregulation: chronic sympathetic overdrive combined with parasympathetic withdrawal. This creates a vicious cycle where autonomic imbalance promotes adverse cardiac remodeling, which further worsens autonomic function. HRV biofeedback represents a paradigm shift toward actively restoring autonomic balance rather than simply suppressing sympathetic activation.

The research is encouraging: Del Pozo et al. (2004) showed that CAD patients can increase their SDNN from 28 to 42 ms through cardiorespiratory biofeedback. Lin et al. (2018) demonstrated that HRV biofeedback cut hospital readmissions roughly in half at one-year follow-up. Swanson et al. (2009) found improved exercise tolerance in heart failure patients with LVEF of 31% or higher, suggesting the intervention works best for those with moderately impaired rather than severely impaired cardiac function.

Check Your Understanding

- Explain how autonomic dysregulation contributes to heart failure progression. Why is this relationship described as a "vicious cycle"?

- Why is decreased HRV considered a significant independent risk factor in cardiac patients, and what does this suggest about the potential value of HRV biofeedback?

- What specific HRV improvements did Del Pozo et al. (2004) observe in CAD patients who received cardiorespiratory biofeedback, and why was the comparison to the control group particularly striking?

- Based on Swanson et al. (2009), which heart failure patients appear most likely to benefit from HRV biofeedback, and what might explain this pattern?

Cardiac Arrhythmias: When the Heart Loses Its Rhythm

The conditions we have discussed so far involve problems with blood pressure regulation or the heart's pumping efficiency. Cardiac arrhythmias represent a different category of problem: disruptions in the electrical system that coordinates the heartbeat.

A cardiac arrhythmia is any heart rhythm disturbance along a spectrum from harmless extra or "skipped" beats that nearly everyone experiences occasionally to life-threatening conditions where the heart's electrical chaos prevents effective pumping.

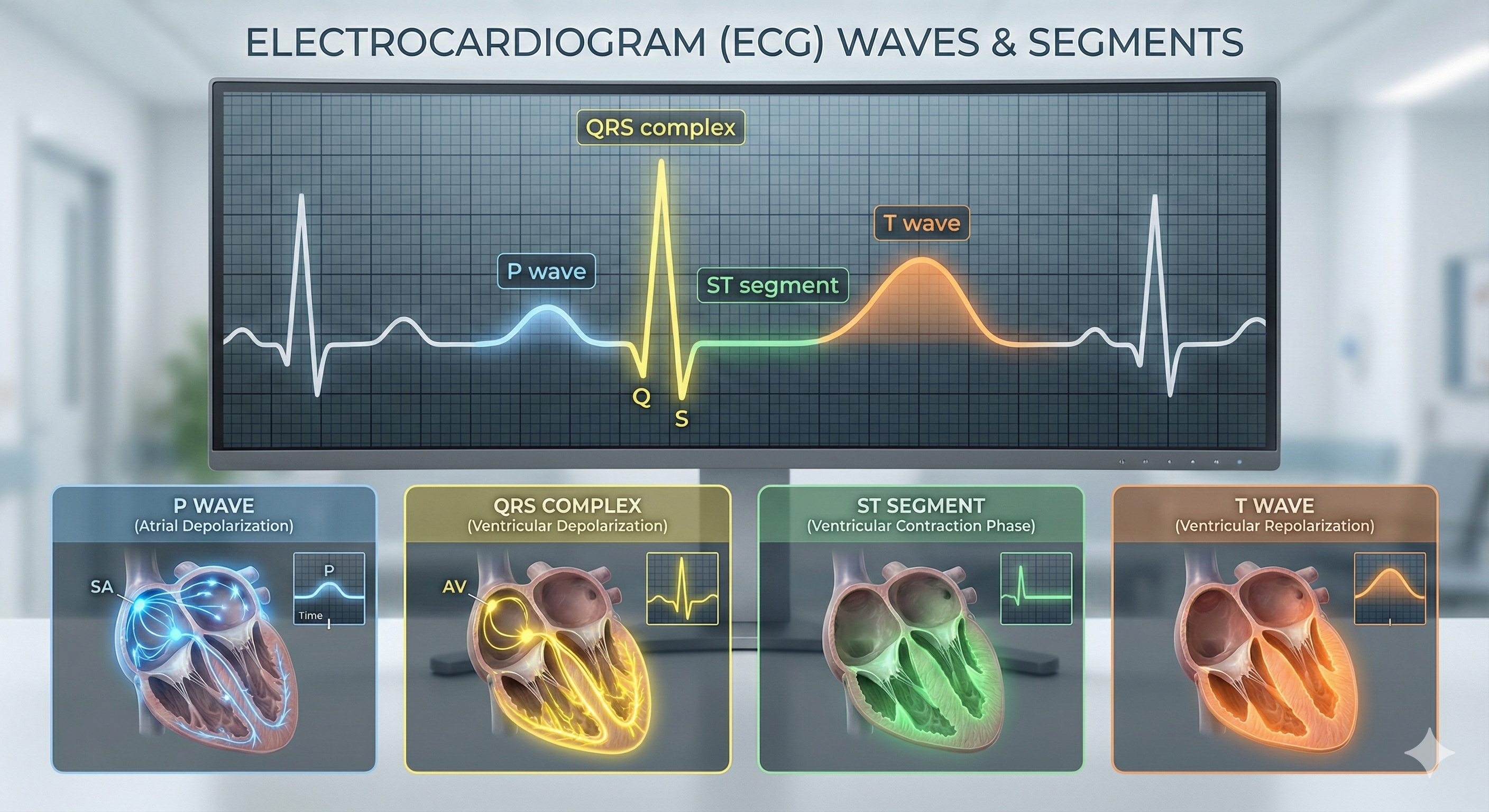

Normally, the sinoatrial (SA) node, the heart's natural pacemaker, generates regular electrical impulses that spread in an orderly pattern through the heart muscle, triggering coordinated contractions. Arrhythmias occur when this electrical coordination breaks down, whether due to problems at the SA node, abnormal electrical pathways, or irritable heart tissue that fires spontaneously.

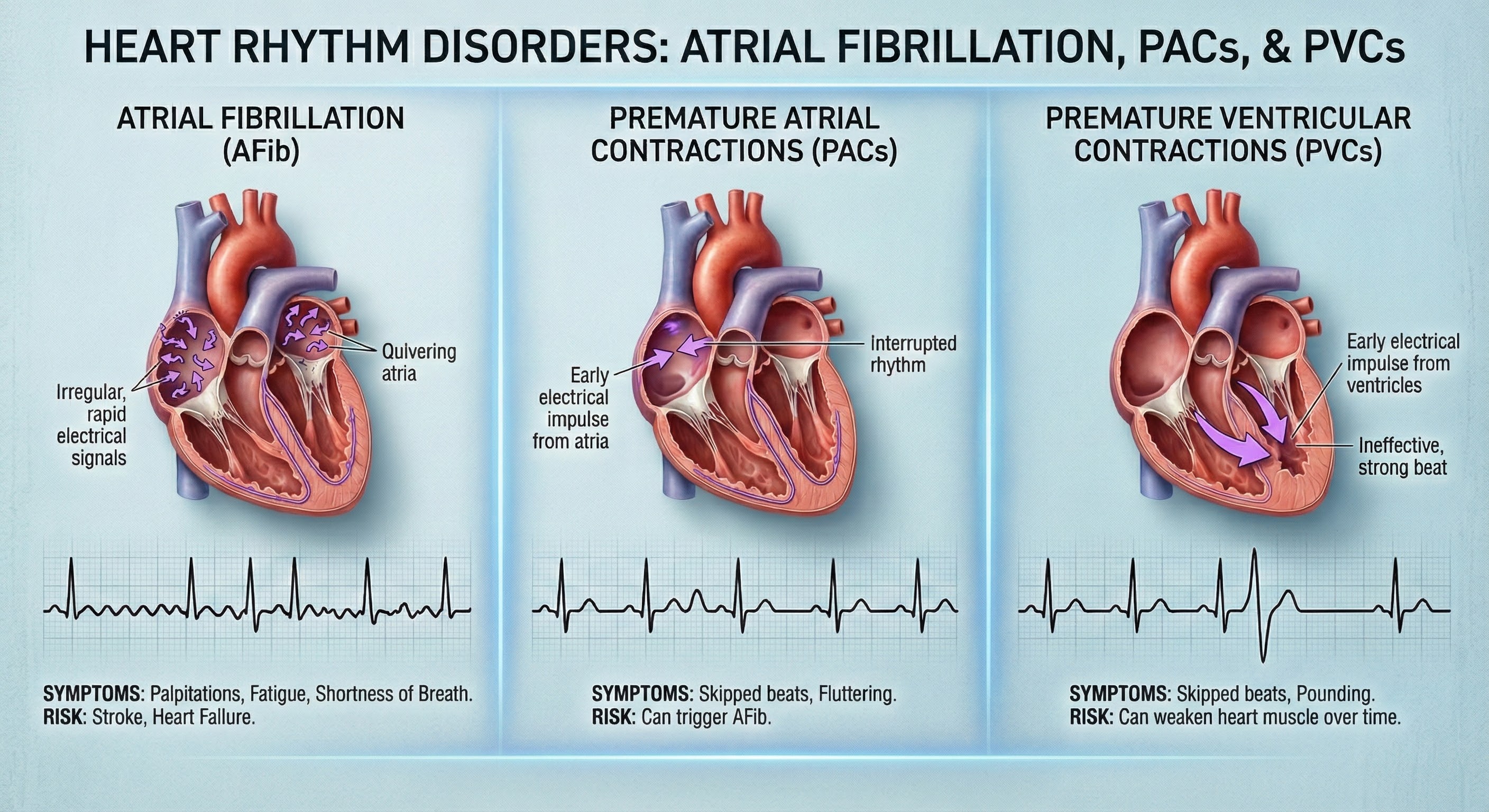

Types of Arrhythmias

Arrhythmias are classified by where in the heart they originate. Supraventricular arrhythmias begin above the ventricles, in the SA node, the atria (upper chambers), or the AV junction (the electrical connection between atria and ventricles).

Common examples include sinus tachycardia, where the SA node simply fires too fast, generating 100 to 150 beats per minute. While uncomfortable, sinus tachycardia at least maintains an organized rhythm.

More problematic is atrial fibrillation, characterized by chaotic, disorganized electrical activity in the atria firing at rates above 300 per minute. Because the atria are quivering rather than contracting in a coordinated fashion, they cannot efficiently move blood into the ventricles. Atrial fibrillation is particularly common in older patients and reduces cardiac output by decreasing the time available for the ventricles to fill between beats.

Ventricular arrhythmias originate in the ventricles themselves and tend to be more dangerous because the ventricles are responsible for pumping blood to the body (left ventricle) and lungs (right ventricle).

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) are extra heartbeats that begin in ventricular tissue rather than the SA node. You may have felt these as a "fluttering" or "skipped beat" sensation. PVCs are extremely common and typically benign in people without underlying heart disease. However, in patients with existing cardiac conditions, frequent PVCs can sometimes trigger more dangerous arrhythmias. Notably, acute emotional stress is a well-documented trigger for cardiac arrhythmias, particularly in people with vulnerable hearts (Ziegelstein, 2007).

This stress-arrhythmia connection provides a rationale for biofeedback intervention: if stress triggers arrhythmias, then stress reduction and improved autonomic control might reduce them.

Biofeedback Research for Arrhythmias

The idea that people might learn to voluntarily control their heart rhythms sounds almost fantastical, yet pioneering research demonstrated exactly that. In groundbreaking work, Weiss and Engel (1971) showed that patients with premature ventricular contractions could learn to influence their heart rates through operant conditioning, the same learning process where animals learn to press levers for food rewards. Continuous beat-by-beat heart rate biofeedback, which displays each heartbeat in real time, emerged as the treatment of choice for both supraventricular arrhythmias and ventricular ectopic beats.

The most effective approach involves bidirectional control training, where patients learn not only to slow their heart rates but also to speed them up, and not only to suppress abnormal beats but also to produce them on command. This bidirectional training, developed by Engel and colleagues, gives patients more complete voluntary control over their heart rhythm than simply training them in one direction. The logic is that true mastery of any skill requires the ability to move in both directions, and heart rhythm control is no different.

While showing genuine promise as an adjunctive treatment, Engel and Baile (1989) appropriately cautioned that these procedures had not yet achieved the status of established treatments, a caution that remains relevant today given the limited subsequent research.

Clinical Efficacy Rating

Due to limited controlled research in recent decades, biofeedback for cardiac arrhythmias is currently rated as level 2: possibly efficacious. The early case studies and small trials by Engel and colleagues established proof of concept, demonstrating that voluntary control of heart rhythm is genuinely possible.

However, larger randomized controlled trials are needed to establish standardized treatment protocols, determine optimal training parameters, and identify which patients are most likely to benefit. This represents a potentially fruitful area for future research, particularly as continuous heart rate monitoring technology has become far more accessible and sophisticated since Engel's pioneering work.

Cardiac arrhythmias span a wide spectrum from benign extra beats that most people experience occasionally to life-threatening rhythm disturbances requiring emergency treatment. The key anatomical distinction is between supraventricular arrhythmias, which originate above the ventricles (in the SA node, atria, or AV junction), and ventricular arrhythmias, which originate in the ventricles themselves.

Ventricular arrhythmias tend to be more dangerous because they directly affect the heart's main pumping chambers. Emotional stress is a well-documented trigger for arrhythmias, providing a rationale for biofeedback intervention.

Continuous beat-by-beat heart rate biofeedback using bidirectional control training, where patients learn to both increase and decrease heart rates and to both produce and suppress abnormal beats, allows patients to gain voluntary control over their heart rhythm. While the research is promising, biofeedback for arrhythmias requires further controlled studies to achieve established treatment status.

Check Your Understanding

- What is the key anatomical difference between supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias, and why does this distinction matter clinically?

- Why might bidirectional control training (learning to both speed up and slow down the heart, and to both produce and suppress abnormal beats) be more effective than simply training patients to slow their heart rates?

- Under what circumstances should clinicians be concerned about PVCs, and when are they considered benign?

- Engel and Baile (1989) cautioned against calling biofeedback for arrhythmias an "established treatment." What would need to happen for this rating to change?

Cutting-Edge Topics in Cardiovascular Biofeedback

Wearable HRV Biofeedback for Cardiac Rehabilitation

The biofeedback field is being transformed by advances in wearable biofeedback technology. Smartwatches, chest straps, and other consumer devices can now deliver real-time HRV feedback throughout the day, not just during weekly clinic visits. This represents a fundamental shift in how training can be delivered.

A 2023 systematic review by Laborde and colleagues examined 143 HRV biofeedback studies and identified three main protocol approaches being used: optimal resonance frequency training (where each patient's unique resonance frequency is identified and trained), individual biofeedback-guided breathing (where patients learn to breathe in ways that maximize their HRV), and preset-pace breathing at approximately 6 breaths per minute (Laborde et al., 2023).

Early studies suggest that patients receiving continuous feedback throughout their daily lives show greater improvements in autonomic balance than those limited to weekly clinic sessions, which makes intuitive sense given the importance of practice in skill acquisition.

Particularly exciting is the integration of machine learning algorithms that can personalize breathing protocols based on individual physiology, potentially optimizing outcomes for heart failure and coronary artery disease patients. Researchers are also exploring the possibility of early warning systems that could detect dangerous changes in HRV patterns before cardiac events occur, shifting the paradigm from treatment to prevention.

Vagal Nerve Stimulation and Biofeedback Synergies

An intriguing new research direction explores combining non-invasive vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) with HRV biofeedback training. Transcutaneous VNS devices, which stimulate the vagus nerve through electrodes placed on the ear (where a branch of the vagus is accessible through the skin), are being tested as a "priming" intervention before biofeedback sessions.

The theory is that directly stimulating the vagus nerve may activate the parasympathetic system in ways that make subsequent biofeedback training more effective, essentially "warming up" the system before training begins.

Preliminary findings suggest that this combination may accelerate skill acquisition and produce larger increases in vagal tone than either intervention alone. This approach may be particularly valuable for patients with severely reduced HRV who struggle to show improvement with biofeedback alone. Their autonomic systems may be so dysregulated that they need an external "boost" to become responsive to training.

Clinical trials are underway to determine optimal protocols and identify which patient populations benefit most from this integrated approach.

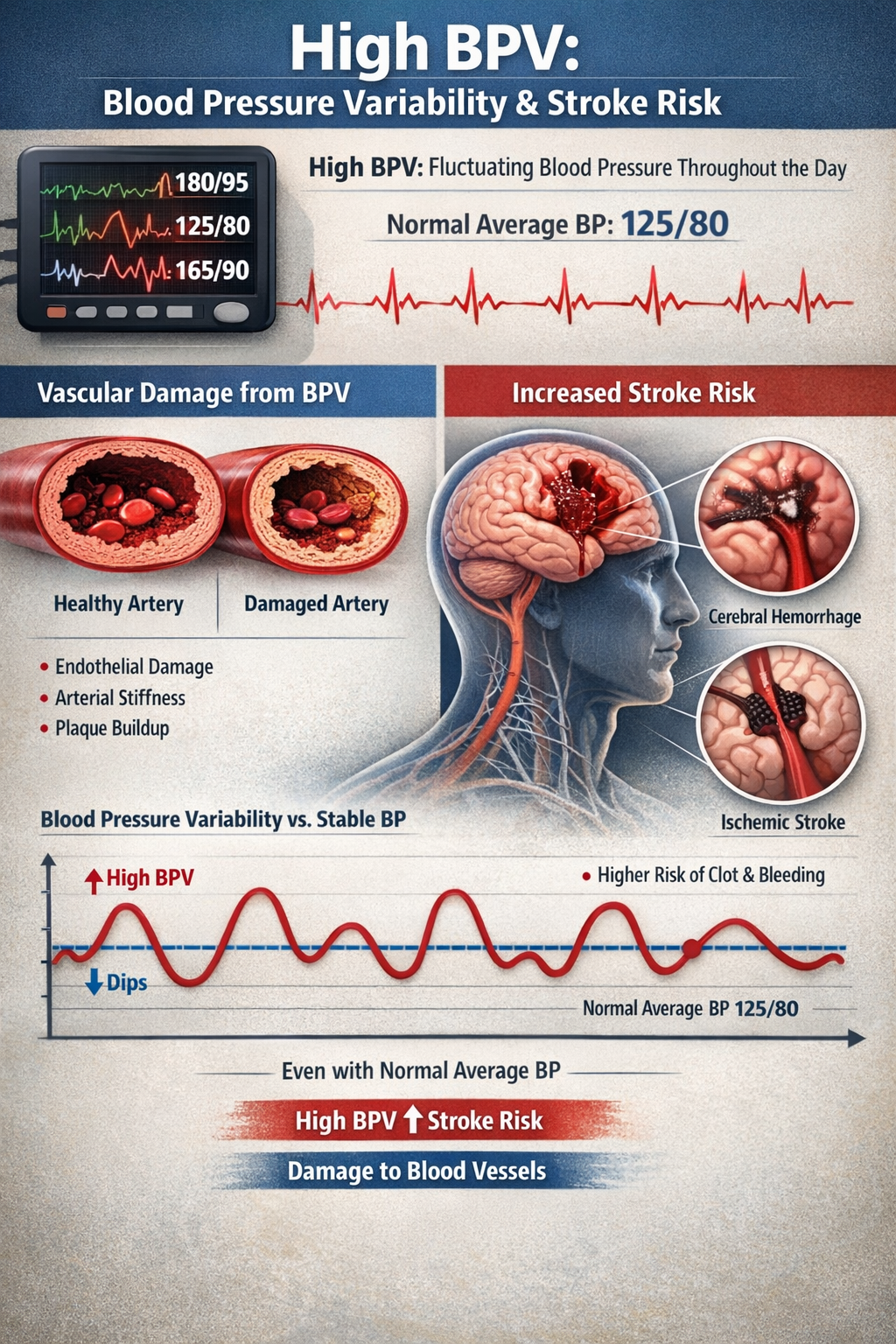

Blood Pressure Variability as a New Treatment Target

Clinicians have traditionally focused on reducing average blood pressure levels, but emerging research highlights blood pressure variability (BPV) as an independent risk factor that may be equally important. High BPV, meaning blood pressure that swings dramatically throughout the day rather than staying relatively stable, appears to damage blood vessels and increase stroke risk even when average readings fall within normal ranges. A patient might have a "normal" average BP of 125/78 but still face elevated risk if their readings fluctuate wildly from 100/60 to 150/95 over the course of a day.

Researchers are now developing biofeedback protocols specifically targeting BPV reduction through a combination of slow breathing techniques, stress management training, and lifestyle modifications. Early results suggest that patients can learn to stabilize their blood pressure patterns, potentially providing cardiovascular protection beyond what average blood pressure reduction alone achieves. This represents a new frontier in cardiovascular biofeedback with significant clinical implications.

Test Yourself

Click on the ClassMarker logo to take 10-question tests over this unit without an exam password.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Visit the BioSource Software Website